Balancing Vertical Acquisitions and Strategic Outsourcing

A study of how non-efficiency conceptions can influence vertical integration strategies and impact organizational boundaries.ALM, ARTHUR ANDERS BERGMAN, ALEXANDER ÅGE, ELLA

School of Business, Society & Engineering

Course: Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration Course Code: FOA230

15 cr

Supervisor: Silvia Bruzzone

Date: Seminar Version May 25, 2020 Final Version June 8, 2020.

ABSTRACT

Date: Seminar Version May 25, 2020 / Final Version June 8, 2020.

Level: Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration, 15 cr.

Institution: School of Business, Society and Engineering, Mälardalen University. Authors: Arthur Anders Alm Alexander Bergman Ella Åge

(98/01/25) (94/06/17) (96/04/11)

Supervisor: Silvia Bruzzone

Keywords: Acquisitions, Outsourcing, Vertical Integration, Strategy, Organizational

Boundaries.

Research Question:

How can organizational boundaries be impacted by the vertical acquisition and strategic outsourcing choices of executives?

Purpose: To gather detailed insights on how executives at the corporate level of management balance vertical acquisitions and strategic outsourcing. These insights will serve as the basis for a qualitative study to contribute with information useful in covering the knowledge gap concerning managerial challenges in balancing vertical acquisitions and strategic outsourcing and how it moves the organizational boundaries, through looking at the non-efficiency reasons that influence those decisions.

Method: The authors have conducted semi-structured video interviews with 4 purposively selected executives each having experience with one of either full-integration, taper-integration, quasi-integration, or non-integration. Their insights have been the basis for a thematic analysis through an open-coding process.

Conclusion: There is a wide range of factors that impact the balance between vertical

acquisitions and strategic outsourcing, which not only can be explained in terms of efficiency. These factors are multi-layered and can be found in the individuals who set the strategy, the organizations as a whole, and also the environment in which they operate, which has shown to be dynamic. Depending on the vertical integration strategy of firms, the concept of organizational boundaries are applied very differently. Numerous organizational boundaries expand and contract when a company vertically integrates with an acquisition or when non-integrating by strategically outsourcing tasks along the value-chain.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to the Participants of this study who, despite these unprecedented times and radically changed business climate, could somehow make time for us and our research in their busy schedules. This golden gesture has been key for us to complete this thesis and our thankfulness extends beyond the scope of imagination.

We would also like to send our gratitude to our supervisor and seminar group mates for their feedback and guidance throughout this academic undertaking. It shall also not go unnoticed that Mälardalen University’s staff could quickly switch to digital teaching methods which allowed us to finalize our International Business studies without any delays. This has been very highly appreciated.

June,2020.

Västerås, Sweden. Arthur Anders Alm Alexander Bergman Ella Åge

Table of Contents

1 - Introduction 1

1.1 - Background 1

1.2 - Problematization 2

1.3 - Delimitations 4

1.4 - Purpose of the Thesis 4

1.5 - Research Question and Operationalization 5

2 - Theoretical Framework 6

2.1 - Organizational Change and Design 6

2.1.1 - The Organizational Boundaries 7

2.2 - Strategic Management 8 2.2.1 - Vertical Integration 10 2.2.2 - Vertical Acquisitions 13 2.2.3 - Strategic Outsourcing 15 3.2 - Conceptual Framework 17 3 - Methodology 18 3.1 - Qualitative Research 18 3.2 - Sampling Technique 19 3.3 - Data Collection 22

3.3.1 - Primary and Secondary Sources 22

3.3.2 - Primary Data 23

3.4 - Analysis Method 24

4 - Empirical Findings 25

4.1 - Management and People 25

4.2 - Expertise and Core Competencies 27

4.3 - High Value vs Low Value-Adding Activities 29

4.4 - Barriers and Difficulties 30

4.5 - Interorganizational Relations 32

5 - Analysis 34

5.1 - Managers’ Roles in Vertical Integration 34

5.2 - Setting the Vertical Integration Strategy 35

5.3 - Implementing the Strategy and Managing Change 37

5.4 - Impacts on the Organizational Boundaries 38

6 - Conclusion 41

7 - Bibliography 42

1

1 - Introduction

In the introduction, a background on the phenomenon of vertical integration and organizational studies are presented. The problem is outlined by clarifying the academic knowledge gap which leads to the research question and purpose of this thesis, before finishing with the delimitations that were made.

1.1 - Background

In international business, most companies rely on independent specialized firms to either deliver their input resources or distribute their output and managers are faced with a dilemma often labelled as the “make or buy” decision (Buckley & Casson, 2009). Harrigan (1985) argues that vertical integration is essentially a decision whether an organization should produce input resources themselves or purchase those resources from other organizations. Strategic outsourcing is often an alternative to producing resources internally. Vertical integration is a manner to increase the margins of value-adding tasks along the value-chain from raw materials to final product in an attempt to maximize cost efficiency, by internalizing value-creating activities. Essentially, vertical integration is the process when an organization becomes its own supplier or distributor. Organizations can choose to vertically integrate backwards in the direction of its suppliers, or forward in the direction of its distributors and customers. Internalization theory assumes organizations will act economically rational and that they will attempt to internalize markets if the estimated benefits are greater than the expected costs (Buckley & Casson, 2009). When making such decisions at the corporate level of management, the organizational boundaries of the firm can shift.

Organizational studies in the field of business administration are aimed towards understanding how companies function, how they influence and are influenced by the business climate they operate in. Aldrich (2008) defines organizations as “goal-directed, boundary-maintaining, activity systems” (p.4). However, to make this definition more relevant in a business context, elements from the microeconomic Theory of the Firm provides for better understanding of what an organization does as they are value-creating entities where factors of production in form of labor and capital are coordinated to effectively produce output in form of goods or services (Coase, 1937). With strategic entrepreneurship, organizations can convert certain input into a desired output (Hitt et al, 2011). Value-creating phases can be influenced by the environment in which an organization operates in.

According to Hall (1977) the structure of an organization’s environment can be divided into two separate categories which are the specific and general environment. The specific environment consists of interorganizational relations composed of other organizations and

2

individuals which an organization directly interacts with. These consist of stakeholders in the form of customers, suppliers, distributors, governments, unions, and competitors. The general environment consists of technological, legal, political, economic, demographic, ecological and cultural dimensions. The condition of the general environment shapes the specific environment of firms and influences all organizations ability to access resources within a business ecosystem. With this in mind, an organization’s environment is the source of valuable input resources and is also the marketplace to which output is released (Hitt et al., 2011).

Inputs consist of different resources such as raw materials, components, and human capital, factors which are all crucial for converting input into output. Companies develop different strategies to obtain scarce resources and to manage their resource dependence (Miller & Shamsie, 1996). However, resource dependence theory suggests that organizations should, to a certain degree, secure scarce resources themselves instead of relying on other organizations to supply them (Pfeffer & Salancik, 2003). Reliance on a supplier or distributor is known to be a symbiotic interdependence. In addition, competitive interdependencies are present among organizations that rival against each other to secure inputs and outputs (Greve, 1996). Both of these interdependencies are a source of uncertainty in the specific environment of firms (Pfeffer & Salancik, 2003).

Organizations can control interdependencies by using different interorganizational uniting mechanisms (Pennings et al, 1984). However, these mechanisms impact the independence of organizations to act freely as value-creating tasks will need to be coordinated across organizational boundaries. Organizations should therefore find the most viable level of decreasing its resource dependence with regards to the trade-off of autonomy that will arise from a unity with an organization it depends on (Galaskiewicz, 1985). Regarding interorganizational relations, organizations should also select and develop a strategy that offers the greatest reduction in uncertainty for the smallest loss of control (Jones & Pustay, 1988). 1.2 - Problematization

The model of natural selection suggests that firms with the most fitting organizational characteristics relative to the environment they are active in, will survive (Hannan & Freeman 1984; Aldrich, 1971). Competitive forces place a substantial pressure on an organization’s ability to evolve and adapt to both current and future market conditions if they strive to preserve their competitiveness in the marketplace (Kanter, 1984). Because of this, companies are encouraged by the market to periodically revise their business models, their organizational design, and go through periods of organizational change. Organizational change is when an

3

organizational entity goes through the process of modifying its current structure and operations (Quattrone & Hopper, 2001). Often this is done to reach a greatly desired and improved form with the goal to be more efficient in its operations.

Unsurprisingly, in business, efficiency is very often measured in monetary or resource terms and these can be referred to as efficiency conceptions. This is most likely because transaction-cost economics and resource dependence direct many of the “make or buy” decisions executives must take. This is also reflected in academia, as it is mentioned in previous studies that costs have been a central issue regarding sourcing and “make or buy” decisions (Welch & Nayak, 1992; Mclvor, Humphreys & Mcaleer, 1997; Cánez, Platts & Probert, 2000). In a study by Walker (2000), it can further be concluded that costs are important to consider also for managers involved in acquisitions (Walker, 2000).

Harrigan (1983) has extensively researched and reviewed vertical integration literature and outlined a framework of the subject which suggests that executives typically have 4 alternatives to choose from. In short, the alternatives are Full-Integration, Taper-Integration, Quasi-Integration and Non-Integration. Executives need to find a suitable equilibrium on which value-adding tasks along the value-chain are worthwhile bringing in-house by making vertical acquisitions and which tasks should be strategically outsourced to other organizations. While in business practice it seems to be that the equilibrium point of when to vertically acquire or to strategically outsource exists, it has not yet been clearly identified in academia.

Because of the knowledge gap regarding previous studies that have been made within the field of vertical integration strategies, Hoffmann & Schaper-Rinkel (2001) in the time of their publication claimed that not enough theories about vertical integration were truly empirically backed, resulting in inconsistencies among the theories. Santos & Eisenhardt (2005) also believe that studies regarding different types of organizational boundary decisions fail to consider “non-efficiency conceptions” which are factors other than purely transactional-cost or the amount of resources that are used in an exchange, which is often a metric to determine how efficiently an organization operates. Instead they suggest that future research should investigate organizational characteristics not derived from transaction-based economies empirics and focus more on the relationships between organizational entities. Jacobides & Billinger (2006), discuss the concept of permeable vertical architecture which is when firms both “Make and Buy” along their value-chain and claim that an overlooked area of organizational design is where an organization’s “external boundaries and internal structure shapes its effectiveness and capabilities”. Consequently, Rothaermel et al. (2006) believe that a more in-depth and highly detailed data generation of how executives can find an equilibrium

4

between vertical integration and strategic outsourcing is needed. Finally, regarding outsourcing, McIvor (2009) states that although very influential, the resource-based and transaction-cost views are not able to explain all difficulties when outsourcing since management aspects when making an outsourcing decision are ignored.

In terms of methodology, Harrigan (2003) claims that previous studies in the vertical integration field are overgeneralized and fail to provide guidance for business practitioners because the findings are contrasting and diffused. Finally, there also seems to be little scientific articles that qualitatively discuss vertical acquisitions and strategic outsourcing in one research paper.

1.3 - Delimitations

This thesis will only address the corporate level of management. Neither will this thesis extend to the depth and the role of the organization in its general environment. Instead, the focus of this research will address the organizational domain of companies, which is the particular range of stakeholders a firm produces output for. There are several different types of acquisitions which can regard different assets and utilities. Acquisitions can also be of horizontal or vertical character, and even a combination of both. In this thesis, the authors will focus on vertical business acquisitions of entire or majority ownership positions in limited liability companies as they are in line with internalization theory. This thesis will not address mergers and when the idea of outsourcing is raised, the authors refer to the strategic business process outsourcing. Finally, the underlying essence of the area of investigation for this thesis is change to the organizational design, which is very often influenced by corporate strategy. For the authors to achieve the purpose and to best answer the research question, a strategic management perspective from the corporate level of management has been selected as strategy is central in the firm’s decision-making process in the “make or buy” dilemma (Park et al, 2000).

1.4 - Purpose of the Thesis

The authors of this thesis intend to gather detailed information about how executives at the corporate level of management contemplate finding the balance between the vertical acquisitions and strategic outsourcing dilemma described in the problematization. These insights will be sourced from a selected sample of business leaders with many years of experience, where they have been faced with this dilemma. Their insights serves as the basis for a qualitative study to contribute with information useful in covering the knowledge gap

5

concerning managerial challenges in balancing vertical acquisition and strategic outsourcing. The authors will do this through investigating how executives balance the two alternatives mentioned above and how it moves the organization's boundaries, through looking at the non-efficiency reasons that influence those decisions.

1.5 - Research Question and Operationalization

How can organizational boundaries be impacted by the vertical acquisition and strategic outsourcing choices of executives?

At the top of Figure 1, the authors begin with the concept of vertical integration at the corporate level of management. Executives are later faced with a “make or buy” dilemma at the magnitude of entire organizations and can choose between vertically integrating with a vertical acquisition of another organization or to strategically outsource value-creating tasks to suppliers or distributors. The data gathered from these “make or buy” decisions will then be used to discuss and analyze how the organizational boundaries of firms can be impacted.

6

2 - Theoretical Framework

The following section presents the literature review concerning organizational change and design, organizational boundaries, strategic management, vertical integration, vertical acquisitions and strategic outsourcing.

2.1 - Organizational Change and Design

In this study, business practitioners can approach vertical integration and organizational boundaries from many angles. But modifications to the organizational boundaries by balancing vertical acquisitions and strategic outsourcing also cause organizational change. As organizational boundaries are dynamic and constantly fluctuate (Afuah, 2001), it is important to highlight what organizational change is and the challenges that may come with it. Quattrone & Hopper (2001) have reviewed organizational change literature and claim that researchers have investigated this area without truly knowing and defining what change is. Therefore, they describe that organizational change is the process when organizational units transform their operations or design from one state to another. For organizations, change occurs when an organizational unit has distinct characteristics at point “A” that have evolved at point “B”, where the unit has other distinctive characteristics. As seen in Figure 2, the change process takes place in a spatio-temporal domain where in the process of going from “A” to “B”, organizations gain and lose identifiable characteristics (Quattrone & Hopper, 2001).

Quattrone & Hopper’s (2001) definition of change, while at its very core is arguably true, it can be considered remarkably simplistic. Through their research, Moran & Brightman (2001) observed that change is non-linear, has a vague timeframe and can therefore be perceived by the people involved in the change itself, to never have a beginning nor an end. Since organizational change is often driven by the various forces present in an organization’s environment, as mentioned in the background, competition between organizations is a major driving force for organizations to change, as they battle against each other to gain and sustain competitive advantages (Kanter, 1984).

7

However, organizational change is often a difficult process faced by many resisting forces. Lewin (1951) proposed the Force-Field Theory of Change where forces for and against change balance against each other and that managers can drive change by either increasing the forces for change or by reducing the resistance to change. Ultimately, the stronger force will prevail. Blau (1970) claims that when organizations grow and become more complex, managers need to address the growing issue of how to coordinate and control value-creating tasks. Managers should evaluate how their organization is designed relative to the environment it operates in. Differentiation is the term often used to understand how resources are allocated throughout organizations and is composed of spatial, occupational, hierarchical, and functional components (Blau, 1970).

Lawrence & Lorsch (1967) researched how firms in various industries modified their organizational structure to fit the characteristics of their environment. They discovered that organizations which operate in environments with a high level of complexity and richness perform best when they are less formalized, decentralized, and agile. However, a high level of differentiation implies a much greater need to coordinate value-creating activities between organizational units. Whereas firms operating in industries with low variations and were perceived as “stable”, benefitted from centralization and standardized processes. These findings were further strengthened by the findings of Burns & Stalker (1961) who theorize that organizations can have two types of structures based on a mechanic or organic design. How organizations choose to construct their design depends on the environments they are in and the frequency which the environmental dimensions change.

Contingencies, potential problems which an organization anticipates, can also be reflected in the organizational design of firms. Executives can adopt a contingency approach to best customize the organizational design to handle uncertainties present in the environment (Child, 1972; Aldrich & Pfeffer, 1976). How organizations are designed also determine the organization’s boundaries.

2.1.1 - The Organizational Boundaries

Organizations are “goal-directed, boundary-maintaining, activity systems” (Aldrich, 2008, p.4). However, the boundaries come in many forms and the attempts to constitute the organizational boundary are mixed. A commonly accepted and straightforward organizational boundary, in practice, is the legal boundary as one approach has claimed that the resources possessed by the organization act as the frontier (Helfat, 1997). Another approach has been to understand how value-creating tasks performed under a certain logic of identity, which focuses

8

on a common ground between people on how tasks should be performed and in turn, also determines the rules of inclusions in the organization (Dutton et al., 1994; Kogut, 2000). For a long time, the organizational boundary has been determined by transaction-cost economics developed by Williamson (1981) and exchange efficiency perspectives as seen in Poppo & Zegner (1998) and Nickerson & Silverman, (2003). But in an attempt to trigger new research on other forms of organization boundaries, Santos & Eisenhardt, (2005) propose that there are boundaries concerning power and competence, in addition to the previously mentioned boundaries of identity and efficiency.

There have also been network approaches to constitute the organizational boundary and have resulted in the idea of boundaryless organizations, because as communication technologies improve, workers in the organizations never have to meet fact-to-face (Fulk & DeSanctis, 1995). Along with the increasing popularity of outsourcing, managers do not necessarily need to develop complex organizational structures, but can instead keep their own organizational design rather simple. This allows for many boundary-spanning activities and with the help of IT, knowledge can flow across the boundaries more easily which can be a source for promoting innovation (Hansen, 1999). The impact of software and IT development to the organizational boundary, lengthening value-chains and network relationships lead to new inter-organizational relationships, as seen in the service sector (Flecker & Meil, 2010). Nonetheless, it is arguable that organizational boundaries can be categorized into either structural or conceptual categories.

2.2 - Strategic Management

Ansoff et al. (2019) defined strategic management as an internal process in which managers take the internal and external environment into consideration when taking action. The process is divided into three activities described as “strategic planning, capability planning and management of change” (Ansoff et al., 2019, p.64). Hatten (1982) further elaborated on Ansoff’s description and included that strategic management can be a powerful tool for companies to develop and successfully complete long-term goals as managers would take into mind the capabilities the firm possesses and through them, develop a strategy on how to handle the changing business environment. Hatten further highlights the importance that companies view their internal flaws and capabilities when developing a long-term goal and frequently analyze their executions (Hatten, 1982).

9

A relatively new branch of strategy, namely Strategy as Practice (SAP), takes strategy one step further by emphasizing the importance of examining strategy more in-depth, and to further investigate the way strategy is exercised by the individuals within organizations. What has worried SAP researchers is the fact that the field of strategy research has been dominated by models based on large amounts of data, which causes the complex reality that characterizes strategy making to be simplified and thereby taking minimal consideration of the impact human factors have on a strategy. In this study, the authors are interested in gaining more in-depth knowledge about the non-economic factors involved in vertical acquisitions and outsourcing strategies and to do this, the authors focus on the practitioners involved in setting out those strategies. In line with this, practice researchers think it is important, to create a deeper understanding of the complicated reality that constitutes strategy making. In order to achieve this, SAP directs the focus towards the practitioners, the individuals involved in the pursuit of strategy within organizations. SAP looks closer at some of the difficulties occurring for these individuals in their work, for example when it comes to making the right priorities when many options are available. Also, other obstacles that can come from the lack of complete information regarding certain issues. Finally, also at the same time balancing the challenge of having to consider multiple stakeholders’ interests (Jarzabkowski, 2005).

SAP is interested in gaining more detailed information regarding how strategists think, how they communicate, the way they reason, behave, interact with others, portray emotion or beautify to make an activity become political in character, also the type of instruments they use are of interest. This branch distances itself from economic assumptions often used in strategy research (Jarzabkowski, 2005). In this study, the cornerstones just mentioned, will be used during the interviews in order to identify how the practitioners operate and reason when creating strategy within an organization.

10

To facilitate empirical research within this field, Jarzabokowski, Balogun & Seidl (2007) introduced a model that highlights the main three concepts of SAP as seen in Figure 3, entitled practices, praxis and practitioners. The latter one, practitioners, will be the focus of this study. When looking at practitioners from a strategic point of view, it becomes evident that those individuals are suitable for study purposes. As their actions have a significant impact on the activities that are determinant for the future survival of the firm. As demonstrated in the figure, practitioners can be seen as interconnected with the two other concepts as seen in Figure 3, and are described in the article to “shape strategic activity through who they are, how they act and what practices they draw upon in that action” (Jarzabokowski, Balogun & Seidl, 2007, p. 10).

2.2.1 - Vertical Integration

Harrigan (1983) claims that to formulate a successful vertical integration strategy, a critical element is to determine how vertically integrated an organization should be at a given moment in time. This may very well depend on the organization’s industry, needs, and internal qualities. Therefore, she suggests that there can be 4 alternatives of vertical integration. However, firms are not limited to use only one of these vertical integration alternatives but can use a mixture or combination of them (Sichel, 1973).

11

1. Full-Integration is when a firm produces or sells all of their input and output resources within the boundaries of the organization. Normally, fully integrated companies are markets share leaders and full integration is appropriate when:

- Companies need to protect business sensitive information from espionage. - An input resource must be precisely designed.

- The firm in question wants to monitor quality control along the entire value-chain. - Cost advantages can be gained by effectively coordinating interconnected

value-creating tasks.

2. Taper-Integration is when a firm depends, to a certain extent, on suppliers to deliver input resources or distributors to distribute output resources. Taper integrated firms produce or distribute a portion of their resources and complement the remaining via external, specialized organizations. This alternative works best when:

- An external firm can add significant value to the resource they produce or distribute. - There is an abundance of raw materials and contractors are accessible.

- Abundance in capacity does not generate a significant economic disadvantage. 3. Quasi-Integration is when a firm does not own, to its entirety, the bordering

organizations in question, but consume or distribute all, some or none of the inputs and outputs of the quasi-integrated organizations. This method is best used when risks are considered to be high. Large quasi-integrated companies can have the power to influence, for example, supplier’s suppliers with very detailed specifications of components or raw materials, in addition to also being able to influence customer’s customers in similar manners (Blois, 1972).

4. Non-Integration also referred to as Contracting, is when carefully written legally binding documents outline the responsibilities of separate organizations but there is no internal integration stabled from those documents. Contracting works best in highly volatile industries.

12

Figure 4 is a schematic representation of the 4 vertical integration alternatives made by the authors. The shaded area represents an entire industry while the individual white boxes represent organizational agents active in the industry. Consequently, the bold dark perimeter of the organizations represents their boundaries. In this scenario, the industry has 9 agents and shows examples of a fully integrated firm, a taper integrated firm, quasi-integrated firms and independent contractors. The double headed arrow to the left represents the business vertical, meaning the entire chain of the industry. The horizontal dotted lines divide the value-chain into three stages (supply, production, and distribution). The cycle icons between Supplier 3, Producer 3 and Distributor 3 represent partnerships between them. The organization to the left demonstrates a firm that is fully integrated and is therefore its own supplier, producer and distributor. A firm like this can operate as one organization along the business vertical or in legal terms be completely separate organizations at the different steps of the value-chain under the same ownership. The taper integrated firm second from the left is vertically integrated in terms of production and distribution but relies on Supplier 2 to deliver its input resources. Supplier 3, Producer 3, and Distributor, 3, are quasi-integrated firms along the whole business vertical. This means that they appear to behave as one organization, but are 3 completely separate organizational entities, in terms of legality. The final example seen on the right are firms who have established contractual agreements between them and have no internal integration between them, as they niched in one step along the value-chain and outsource the remaining value-creating activities.

13

Some of the advantages that can be gained from vertical integration are “decreased marketing expenses, stability of operations, certainty of supplies of materials and services, better control over product distribution, tighter quality control, better inventory control, additional profit margins or the ability to charge lower prices on final product” (Blois, 1972, p. 253-254). Whereas the disadvantages are “disparities between productive capacities, public opinion and governmental pressure, lack of specialization, inflexibility, extension of the management team, and lack of direct competitive pressures on the cost of intermediate products” (Blois, 1972, p. 254).

Although not obvious, vertical integration is the idea of shifting the organizational boundaries as seen in Figure 4. When breaking down vertical integration to a small but significant level, it is the organizational boundaries which acts as the fine line between what activities a firm has internally and what tasks along the value-chain are outsourced to other organizations.

2.2.2 - Vertical Acquisitions

Acquisitions can be a tool for managers in order to move the organizational boundaries according to Schildt & Laamanen (2006). The way these boundaries extend can differ, it might be a question of extending the range to cover new regions geographically, or the firm aims to expand their technological capacity. Another type of boundary expansion is extension of the firms network. Previous studies have been able to identify that many reasons for why acquisitions take place are connected to different types of efficiencies in terms of strategy, management and economics. However, Schildt & Laamanen’s article adds to those findings, by arguing that the information decision makers have at their disposal also plays a part when facing an acquisition. When an evaluation of the company, relevant for the acquisitions is carried out, this information is often based on the context in combination with the existing knowledge that the manager possesses (Schildt & Laamanen, 2006).

Borys & Jemison (1989) observed that changes in the business environment were taking place and that it was becoming increasingly common that the shape and form of organizations varied to a greater extent than previously. They describe that these arrangements might be the result of strategic alliances being formed among organizations, with acquisitions as the major type of arrangement. In order to provide a clear definition of the concept of acquisitions, this study will use the definition provided by Borys & Jemison (1989) as a starting point, which explains that, “Acquisitions involve the purchase of one organization by another, such that the buyer assumes control over the other” (Borys & Jemison, 1989, p. 235).

14

When corporations decide to combine their activities vertically, it means that the firms before the acquisition were linked through a buyer-seller relationship. Acquisitions in a vertical direction therefore implies that the acquirer after the purchase has been able to move position, either closer to the ultimate origin of supplies or in the direction towards the end consumer (Gaughan, 2015).

As mentioned above, the vertical acquirer can move in two directions, and are often referred to as either an upstream or downstream acquisition. Due to the buyer-seller relationship, the vertical acquisition is regarded to be a more advanced process, if compared with the horizontal, which can briefly be described as a situation where one company acquires a competitor that is operating in the same marketplace. It is also described that in connection with vertical acquisitions, difficulties regarding selection for purchase may arise as there are generally fewer suitable candidates, as there are several requirements that must be met (Rozen-Bakher, 2018).

Other reasons to acquire exist and they are often based on fully reasonable business decisions such as obtaining an increased profit, enjoying benefits from economies of scale and economies of scope, obtaining needed but lacking knowledge or resources, or gaining presence in new parts of the market. It was found that individuals who possess great knowledge regarding acquisitions, did not view human capital as one of the crucial aspects in order to obtain a successful outcome. Further, this is suggested to mirror the proposition that most acquisitions circuits around economic reasons. However, many managers’ positive attitude towards strategic acquisitions seems to be unjustified, as 50-80% of acquisitions fail to live up to the expected gain (Nalbantian, Guzzo, Kieffer, Doherty, 2005).

Zollo & Singh (2004) conclude that managers who in various ways document the acquisition processes they go through, and thus gather experience, create a positive correlation with the execution of acquisitions. These documenting procedures can be the collection of experience that is accurately documented through coding and saved in manuals for later use, or it can also concern different types of systems or other acquisition typical instruments. They highlight that their findings do not support a successful result coming solely from experience (Zollo & Singh, 2004). Nadolska & Barkema (2014) mentions that the conclusion from this, points towards that how successful an acquisition is, will be affected by how similar the documentation from previous acquisitions are, and thus how well the documentation can be used in following cases (Nadolska & Barkema, 2014).

As early as 1986, an interesting alternative objective for economic profit, was presented by Richard Roll, it is referred to as the Hubris Hypothesis. This alternative explanation

15

described the possibility for acquisitions to be driven by the individual needs and purposes of the manager in charge of the acquisition, and not necessarily with the shareholders’ main interest in mind. This hypothesis aims to explain why it appears that managers on average pay over-price for the purchase objectives, with the explanation being “hubris” of the manager (Roll, 1986).

Tanner (1991) addresses some of the critical aspects regarding acquisitions. He argues that there is no way to guarantee a success, however, an accurately planned acquisition procedure can downplay the risk of encountering any of these problems. There are two mistakes in which he refers to that are particularly relevant for this thesis. The first one is called “Management difficulties” which refers to when deficiencies lie within the management, and they fail to lead the way in the right direction. The second mistake of interest is called “The wrong target”. In order to avoid this type of mistake it is important to have a clear strategic objective right from the start, and also a well-defined mission. Also, to conduct a thorough analysis of the target company and make sure it is what it looks out to be.

2.2.3 - Strategic Outsourcing

Burnes & Anastasiadis (2003) defined outsourcing as a process within a firm where part of the internal and external operations, which have been conducted internally, has been given to a contractor to be executed on behalf of the firm. Vecchio & Stephen (2005) states that in the international business context, external parties can consist of offshore firms in less developed countries or even firms which do not follow union regulations. Vecchio & Stephen further describes the negative aspects of outsourcing to be the reduced need of employees within the firm as a result of moving value-creating activities outside of the firm’s boundaries. A positive aspect, raised by Vecchio & Stephen is that firms tend to outsource since it can lead to higher financial gains, risk avoidance and more flexibility within the firm.

However, Roberts (2001) states that executives and managers face the risk of becoming less flexible as a result of outsourcing. The reduced flexibility is due to control loss over activities. Mahmoodzadeh et al (2009) adds that there is a risk of losing the internal knowledge on how to perform the activities, which could potentially result in the firm becoming dependent on the contractor. Hence, showing that there is a debate regarding drawbacks and benefits of outsourcing.

Mahmoodzadeh et al (2009) describes business process outsourcing to be when a firm outsources activities of entire departments and McIvor (2016) states that firms often outsource the responsibility to operate whole value-chain functions to an offshore firm. Vecchio &

16

Stephen (2005) noted that these activities can include vital activities which are required by the firm to reach long-term targets. But Vecchio & Stephens (2005) view is challenged by Burnes & Anastasiadis (2003) who state that there is a debate on whether firms should outsource their key activities or not. This is a result of key activities usually being linked to a firm’s business intelligence and trade secrets.

Mahmoodzadeh et al (2009) states that outsourcing can be narrowed down further to why firms outsource. Mahmoodzadeh describes two reasons for firms to outsource, either a firm wishes to outsource out of tactical or strategic reasons. The background for firms outsourcing out of tactical reasons are for daily activities which are not tended to be consistent for longer periods and are mainly outsourced to increase output or reduce internal costs. The strategic reasoning for firms to outsource goes beyond the financial aspects. Firms that engage in outsourcing activities for strategic purposes tend to focus on the overall success of the business in the long-term, which can be achieved by increasing the advantages the firm has over competitors. Roberts (2001) noticed that firms are facing a fast-changing business environment which makes them more vulnerable to competitors in the market. The need of being flexible and quickly adaptable to changes in the business environment has become part of managers and executives’ concerns. That can be why firms tend to outsource to external parties as an alternative to in-house production.

Roberts (2001), further discusses and connects specialization with outsourcing as he claims that the contractor who specializes in one specific task, can outperform the contractee due to better equipment, economies of scale or greater experience within the specific field, thus performing better and cheaper than in-house service or production.

17 2.3 - Conceptual Framework

18

3 - Methodology

In this chapter, the authors present and support their research method decisions, describe how the participants of this study were selected and why they were selected. Reflections of the strengths and weaknesses of the chosen methods are found throughout the entire chapter. 3.1 - Qualitative Research

The design of the research question resulted in the authors contemplating that the most suitable approach to answer the research question would be by conducting a qualitative study. The points raised by the authors to support this decision were first and foremost the strive to gain an in-depth understanding of the area of investigation. Bryman and Bell (2013) state that qualitative methods are more suited to studies in which the researchers try to gain a deeper understanding of the subject in question.

In this study, the authors are taking a closer look of the complex phenomenon that is Vertical Integration. When it comes to investigating a phenomenon in-depth, Anosike, Erich & Ahmed (2012) means that this can be facilitated by identifying the true “meanings” and “essences” of the experiences that managers live through in organizations (Anosike, Ehrich, & Ahmed, 2012). In this thesis, the authors want to get to the core of what aspects other than cost efficiencies that executives consider when deciding to vertically acquire or outsource. Participants need to be carefully considered. Ziakas & Boukas (2014) emphasize the importance of selecting individuals “who have had experiences relating to the phenomenon under study”. Another important aspect expressed by Hycner (1985) many years ago was that besides the importance of possessing experience, it is of great significance that the participant can express their experience in a good way, which creates understanding of the phenomenon being investigated. Also, it is considered more beneficial to conduct long interviews with a lower number of participants (Phillips-Pula, Strunk & Pickler, 2011).

With this in mind, the authors have therefore chosen to contact 4 individuals which have been selected based on the extensive amount of experience they possess regarding the phenomenon, vertical integration. The selected individuals have in common that they for years have worked within organizations where they come in daily contact with this phenomenon. Due to this, the authors consider them as suitable participants for this research as they are able to give an in-depth description of their own experiences and describe how executives approach vertical integration. However, the nature of the qualitative method also comes with drawbacks that include the ability to replicate the research, generalize the findings, and transparency issues

19

as it is not always clear enough on how the researcher interpreted the data, which can result in a less trustworthy research paper (Bryman and Bell, 2013).

3.2 - Sampling Technique

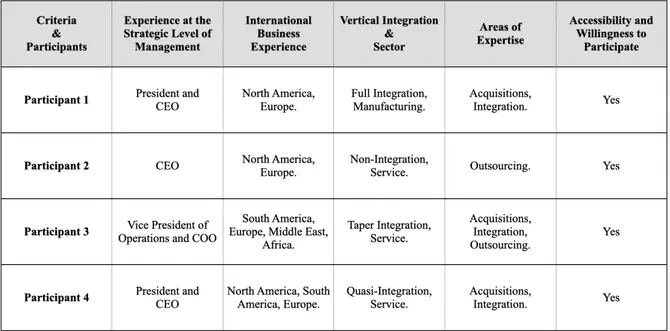

To participate in this study, the authors required that the sample had to fulfill the criteria listed below in Figure 6.

The sample size of this research consisted of 4 selected participants. The authors understood that in order to generate relevant, high quality data, and to secure enough responses for the research question, pragmatism had to prevail as the themes which were to be discussed could potentially include business sensitive topics. In a situation where the researchers and participants are unknown to each other and have had no previous contact, the authors deemed that the quality of the primary data generated in such a circumstance will not be sufficient enough or available for this thesis (Berger, 2013; Garton & Copland, 2010). Therefore, the sample consists of participants from one of the authors personal network and consequently, a blend of the sampling traits which often characterize purposive and convenience sampling techniques have been used. The authors are highly aware of how this choice can be scrutinized because of researcher bias (Maxwell, 2013).

Etikan et al. (2016) have compared purposive and convenience sampling techniques and observed that they are both non-probability sampling methods where randomization is not crucial for the area of investigation. In their comparative study they describe that purposive

20

sampling is when the researchers intentionally chose subjects to include in the study based on them meeting certain criteria set by the researchers themselves. When the researchers have identified what type of data needs to be generated, then they can proceed to select data sources based on their experience or expertise in a field. When using this method, the researchers rely on their own judgement regarding what data sources to include in the sample. Whereas convenience sampling focuses more on practical characteristics of the sample such as their availability and willingness to contribute to study.

The authors are aware that this sample can be considered as controversial precisely because of subjectivity (Etikan et al., 2016). Despite one of the authors having a previous acquaintance with the participants, the authors argue that objectivity was maintained through the research because the other two authors have had no previous contact whatsoever with the sample and could therefore counterbalance any subjectivity from their objective standpoints.

Table 1 shows an overview of the sample and how each participant fulfilled the criteria. Within the cells are keywords which the authors have used to determine how the participants fulfilled the criteria.

Participant 1 has many years of experience managing acquisition and integration processes in a leading commodity company, which in this research will be encrypted to Firm A. Participant 1 worked in Firm A, a nearly fully vertically integrated company, for 12 years as Head Integration Lead and worked very closely with the senior management team during a

21

decade long acquisition spree across Europe. More recently, Participant 1 worked in a building materials company, which in this research will be known as Firm B, also a company where Participant 1 worked with acquisitions and integrations. Currently, Participant 1 is the President and CEO of a building materials company in North America, which focuses more on Research and Development and outsources the entire production of their products. With this background, the authors deemed Participant 1 to be a suitable candidate to provide insights about how companies can vertically integrate by undergoing acquisitions.

Participant 2 is the CEO of an e-commerce organization based in North America, known as Firm L in this thesis, which facilitates buyers and independent contractors coming together. Apart from managing a business that is non-integrated and offers various contracting solutions, it leans more towards the distribution end of multiple value-chains. In addition, the authors also wanted to look more specifically at the organizational boundaries of Firm L and how Participant 2 manages them.

Participant 3 holds the position as COO for the high-end brands in the South American division of a recognized multinational hospitality firm. In this research, this company will be referred to as Firm S and has undergone substantial changes to augment their customer experience and boost its performance and capacities in the hospitality, entertainment, and co-working industries by undertaking vertical acquisitions in an attempt to shift from a taper integrated firm to become somewhat more fully integrated. The authors selected Participant 3 to be a part of the research as the participant could provide detailed insights to how a larger multinational firm can choose to vertically integrate or strategically outsource value-creating activities.

Participant 4 has been working as a CEO within multiple digital technology firms for over 20 years. In Company D, Participant 4 led a 5-year long acquisition spree of dozens of companies. Participant 4 has been selected to partake in this study to provide the authors with insights from companies that operate in an industry that has many quasi-integrated organizations. As of now, Participant 4 works with real estate development projects and sits on the board of directors for numerous technology companies. Participant 4 has also worked with Mergers & Acquisitions in a leading investment banking firm. With this background and experience, the authors selected Participant 4 to participate in the research to collect insights about vertical integration processes.

22 3.3 - Data Collection

To answer the research question, the authors had to gather new insights on the subject and have generated primary data for the empirical chapter by conducting semi-structured video interviews. The authors have also used secondary sources from previous research findings available in Mälardalen University’s Library databases and other research search engines such as Google Scholar. More information about how the data was generated and additional clarifications about the sources used in this thesis will be described under every respective subheading.

3.3.1 - Primary and Secondary Sources

The participants in this study are considered by the authors to be primary sources as supported by Merriam (2009) who defines primary sources to be when the root of the information generated comes directly from one who has experienced what is being said. As the area of investigation could potentially touch upon business sensitive topics, it is therefore the ethical responsibility of the authors to ensure that the confidentiality of the participants and information which can directly or indirectly link to any companies that are mentioned during the data gathering process is strictly maintained confidential. This belief is backed by Bryman & Bell (2013) as they explain that researchers have to respect confidentiality as it is part of ASA Code of Ethics. The decision to maintain confidentiality of the participants throughout the thesis directly causes transparency and reliability issues. Despite this, the authors could, in consensus, find it worthwhile to trade-off transparency and reliability for insightful and very relevant data. This is also motivated by the decision of not wanting to make generalizations of the findings because strategy cannot be generalized, qualitative studies are not meant to be generalized, and the sample size is too small to make generalizations.

The secondary sources used by the authors were mainly used to build the theoretical framework, support methodological decisions, and motivate arguments throughout the thesis. The majority of secondary sources consisted of peer-reviewed scientific articles, along with methodology and research literature. The authors also used these scientific articles as a base for the interview questions, as this ensured that most of the questions asked were based on issues raised in previous studies. Secondary sources are defined by Merriam (2009) as information which comes from places that cannot be directly linked to the actual occasion.

23 3.3.2 Primary Data

The entirety of the data collected for the empirical chapter of this thesis consist of primary data. Primary data is information a researcher has gathered for their own purpose directly from the source (Wilson, 2010). This is aligned with Maxwell’s (2005) definition of primary data as information that has been generated by the researcher themselves and suggests that one technique to generate qualitative primary data is by conducting interviews. The authors determined this data generating technique to be the most suitable for the research as it allows for the generation of highly insightful information about the area of investigation.

Bryman & Bell (2013) and Maxwell (2005) state that interviews are one of the more commonly used tools within qualitative studies to gather data. The usage of interviews allows the researcher to gain data from specific candidates with knowledge within the field of study. More specifically, semi-structured interviews allow the interviewer to keep the interview open, but at the same time within prearranged themes relevant to the area of investigation. The interview design also allows for the interviewee to express what they believe holds value for the open-ended questions. The semi-structured form provides great flexibility, but at the same time the increased flexibility can lead to greater pressure towards the interviewer. The interviewer has to make sure that the questions asked are easily understood by the interviewee (Bryman & Bell, 2013). All of the interviews were recorded, with the consent of the participant, for transcription purposes. Particular words or any other information that can potentially risk leaking the identity of individuals or companies, either directly or indirectly, has been encrypted. This was done by the authors in order to keep the identity of the participating individuals and their companies confidential. During the interviews, the authors have used an interview guide which can be found in the appendices.

24 3.4 - Analysis Method

The authors have analyzed the data through an open-coding technique which is “the process of breaking down, examining, comparing, conceptualizing and categorizing data” (Titscher et al., 2015, p. 79). The open-coding process allows for filtering out the most valuable data points into specific categories. According to Braun & Clarke (2006), specific words and meanings can come up from the qualitative data during the analyzing process. Data with common similarities can be sorted into specific categories and is referred to as thematic analysis. As the authors processed the interviews, they noticed similarities in the data produced by the participants. The thematic categories classifying data points have been labelled as Management and People, Expertise and Capabilities, High Value vs Low Value-Adding Activities, Barriers and Difficulties, and Interorganizational Relation. The authors are aware that these categories can, to some degree, be seen as very emblematic. However, the authors believe that it was the most suitable technique for categorizing data, as it allowed the authors to analyze the data points at a theoretical level.

The most important data points of the five thematic categories that have been the basis for analysis will be presented in the empirical findings section in their respective subcategories. The authors have manually decoded the data points to find the deeper meaning and essences of what was said by the participants. Titscher et al. (2015) noted the importance of analyzing the data carefully and in detail to ensure that there is little to no risk of losing data due to observation failure. Bryman & Bell (2013) further add that data can be put out if its context and that individuals have a tendency to interpret information differently leading to interpretation bias. The authors understand that other researchers can interpret data differently and that there is a risk of observation failure from the researcher’s side which is why the encrypted transcriptions of the interviews are attached in the appendices.

25

4 - Empirical Findings

In this section, the authors will present a summary of the information collected from the interviews along with some key quotations from the Participants. The information presented is deemed by the authors to hold high value and can be used as a basis for analysis.

In search for the essence and deeper meaning of the participants’ responses from the interviews, the authors have developed five conceptual thematic categories. Unsurprisingly, the participants provided very different contexts and examples based on their organizations and personal experiences. By conceptualizing these different contexts, the authors were able to make these experiences more universal. These categories are judged by the authors to be non-efficiency conceptions, meaning the data points have minimal relations to transaction-cost empirics.

From the interviews, it was noticed that many different leaders, individuals, teams, and strategists were mentioned and data points regarding these topics have fallen under the conceptual category Management and People. In the data, it appears that the decision between vertical acquisition and strategic outsourcing is connected with the type of specialization and competitive advantages the organization possesses, data relating to this topic can be found under Expertise and Capabilities. Furthermore, when deciding to perform tasks internally or externally this can be determined by how much value the activity brings to the organization, which is compiled under High Value vs Low Value-Adding Activities. Examples of the several unique challenges that were mentioned by the participants regarding the organizational changes that arise when vertically acquiring have been conceptualized into the category Barriers and Difficulties. What has also been discovered as a pervasive theme that characterizes the relationships between organizational entities is how they collaborate across boundaries. Information regarding these observations will be presented under Interorganizational Relations.

4.1 - Management and People

Participant 1 describes that decisions regarding vertical acquisitions and strategic outsourcing often are made at a senior level of management, meaning the very top management of the organization, such as senior vice president of purchasing and the CEO. The executive further describes the headquarter to be where those types of decisions are made. It is clear from the interview that seniority and experience are decisive factors, when it comes to having a say

26

in the decision-making process. Participant 1 states “Usually that is in terms of seniority more than anything and experience” (Participant 1, 2020).

When incorporating Participant 4’s experience, this executive adds that in order to successfully complete an acquisition more than just “dealmakers” are required, also what Participant 4 refers to as “integration specialists”, the executive states “It is an obvious point but people do not understand it. Successfully executing an acquisition often has more dedicated acquisition personnel” and then continues with “Integration specialists who know what type of integration you are doing - is it a horizontal integration or is it a vertical integration, what was the purpose of doing the acquisition, culturally” (Participant 4, 2020). In line with culture, awareness of this, is something that Participant 1 believes can facilitate the speed of work and describes that it comes with experience and can facilitate situations where managers must communicate these decisions with colleagues from different parts of the world. Participant 1 recalls an event from their own international business experience where cultural understanding had to be demonstrated, and states “In Country F one of the reasons I was able to make all the changes I wanted to make within the acquisition was that I could speak directly to the works council in Language A. Even negotiate with them and explain and communicate very clearly why we were doing what we were doing and actually getting their input into the process” (Participant 1, 2020). It was also found that many of the participants felt that their past experiences from acquisitions came in handy and helped them in future acquisitions (Participant 1, Participant, 3, Participant 4). One of them explains two reasons why experience can help in acquisitions “If you are a company where part of your value proposition, part of skills you have in the company that you are building in the company have to do with acquisitions. You are going to be a better company making acquisitions” (Participant 4, 2020). It cannot be ignored that all participants emphasized the importance of the costs aspect when considering whether to “make or buy” (All Participants, 2020). However, other aspects emerged that executives described they had to take into account. Participant 3 points out that there has been somewhat of a shift of focus by the acquirer and states “Because if there is a story to tell and there is something to be bought, they buy it. Before, [they were only] looking at the balance sheet. If you have really good storytelling, clearly, they will look at the value, but before the financial decision, there is something else today”. Participant 3 explains that storytelling can add value, but at the same time highlights the importance of combining the story with the integration of the joining companies. As the participant elaborates on the answer it becomes clear that a lot of resources are needed to create a story, it was explained that the marketing department and the owner, both can be involved in a process like this. The story not

27

only guides you in what you intend to present to the investors, but also “This storytelling will help you, in fact, to structure the product, the destination and the final investment you have to make, and vice versa, the return expected from that storytelling” (Participant 3, 2020).

Participant 3 also recognizes the importance of the people within the organization, and states “Not synergies, it really is the willingness of the people. It is more a human factor. The human factor always comes back in business at one stage and if that human factor is not there , you can have the best model on one side, the best model on the other side, if the people don’t want to make it happen, it won’t happen" (Participant 3, 2020).

Participant 2 was very determined to claim that the cost played a central role in the decision regarding whether to “make or buy”, however he also adds another factor that can have an impact on the direction of the business, stating “I mean the direction of the business and the self-interest of the management and ownership of the company certainly have an influence even if it is at the decrement of the business” (Participant 2, 2020). In line with self- interest, Participant 4 expresses that ego can become a problem for managers and causes one to focus on aspects that are important to oneself rather than, as explained as “the commercial opportunity” (Participant 4, 2020).

4.2 - Expertise and Capabilities

Many of the participants touched upon ideas which revolve around expertise and capabilities when choosing to have value-creating tasks in-house or externally. Participant 1 mentioned that the very top management of Firm A made an internal training program to pass on the expertise and know-how of a particular production system throughout the organization which gave a competitive advantage to Firm A by mentioning that the company “Felt it had an expertise, that is why whenever they were buying a factory, we were always looking at ways to increase productivity. We thought we were better at productivity than outsourcing that. It really had to do with inhouse expertise” (Participant 1, 2020). Participant 3 also mentions a similar approach by claiming that “You always keep the head of the strategy but then the services below are negotiated and we seek the support from outside to use them in the company and that gives us much more flexibility. We have been buying a few Industry E companies but it really is not our, I would say, bread and butter. So we are trying to go away from that” (Participant 3, 2020). When asked about how organizational boundaries are set, Participant 4 suggests that “You want to decide early – Where are the boundaries to the road, what are we and what are we not. What are our customer desires or what value-proposition are we willing

28

to get into and where do we stop, where do we give the territory to someone else” (Participant 4, 2020).

It can also be the case that to access expertise, companies may look for it externally. Participant 1, although having worked in a nearly fully vertically integrated firm, admits that “We had a shipping company that we used and let’s face it their expertise is bigger and they are actually bigger - meaning for example a shipping company could have operations all over Europe. So they can do it more efficiently than Firm A by having its own delivery service” (Participant 1, 2020). When choosing to outsource it “Is just an assessment on what are your core strengths and you cannot be good at everything” (Participant 1, 2020).

There are similarities among all of the participants that tasks which are considered to be secondary are outsourced. But when asked if companies become too dependent on their outsourced partners, the participants were unfazed. Participant 2 says that it can be the case that “The people you expected to be competent, turn out not to be competent” (Participant 2, 2020) but that outsourcing gives a company the “Flexibility to be able to change on a moment’s notice. If something is not working, you can switch quite quickly to another” (Participant 2, 2020). Participant 2 also shares many thoughts with several participants as “It may sound a bit mercenary by saying that [with] outsourcing you can ‘hire and fire’ but it is a huge benefit to us” (Participant 2, 2020).

To obtain access to expertise and to bring them in-house, acquisitions can be made. Participant 1 says that “We would look at the technology that the target company had, whether or not they had a better or something to add on research and development” (Participant 1, 2020). Participant 1 also mentions that companies can look for synergies and combine strengths from an acquisition by giving a successful example of such a situation when Firm B acquired Firm C “There were two aspects to that acquisition, one was to increase the portfolio of products and the second thing was to reduce costs, so that is a good example where there is a combination of both” (Participant 1, 2020). However, Participant 1 mentions that when acquiring, it is not worthwhile if the acquiring firm cannot instantly take advantage of the firm which was acquired. It should also be noted that there are risks of fading away from the original capabilities of the firm in an acquisition process as Participant 4 warns that “Often when you are doing a vertical acquisition, you are exposing your organization to what really is a different business” (Participant 4, 2020).

When asked about the factors that are considered when setting the organizational boundaries Participant 4 claims that companies “Can set boundaries in terms of what the customers want to achieve” and that by doing this a company can maintain a clearly defined