http://www.diva-portal.org

This is the published version of a paper published in JMM - The International Journal on

Media Management.

Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Achtenhagen, L., Melesko, S., Ots, M. (2018)

Upholding the 4th estate—exploring the corporate governance of the media ownership form of business foundations

JMM - The International Journal on Media Management

https://doi.org/10.1080/14241277.2018.1482302

Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper.

Permanent link to this version:

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=hijm20

International Journal on Media Management

ISSN: 1424-1277 (Print) 1424-1250 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hijm20

Upholding the 4th estate—exploring the corporate

governance of the media ownership form of

business foundations

Leona Achtenhagen, Stefan Melesko & Mart Ots

To cite this article: Leona Achtenhagen, Stefan Melesko & Mart Ots (2018): Upholding the 4th estate—exploring the corporate governance of the media ownership form of business foundations, International Journal on Media Management, DOI: 10.1080/14241277.2018.1482302

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14241277.2018.1482302

© 2018 Institute for Media and Communications Management Published online: 24 Jul 2018.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 96

Upholding the 4th estate

—exploring the corporate

governance of the media ownership form of business

foundations

Leona Achtenhagen , Stefan Melesko, and Mart Ots

Jönköping International Business School (JIBS), Media, Management and Transformation Centre (MMTC), Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden

ABSTRACT

Whereas media ownership issues have interested scholars for decades, research has largely ignored the implications of specific ownership forms on the corporate governance of media compa-nies, that is, how these companies are directed and controlled. This article attempts to address this gap by exploring the corporate governance of the ownership form of business foundations—a type of ownership that is increasing in different countries around the world. We analyze the corporate governance of three business foundations in the Swedish newspaper sector that together hold 26% of the market and outperform their industry peers. The con-trol function, which is at the heart of corporate governance, is typically performed by companies’ owners. However, foundations do not have a physical person as owner; thus, this control function is replaced by the foundation’s charter, which stipulates the aim of the foundation’s business activities. When steered by professional top management, the charter’s long-term orientation facilitates the careful implementation of strategic directions without short-term performance pressures. We conclude the article by outlining sev-eral advantages and disadvantages of this ownership form for the media industry. ARTICLE HISTORY Received 6 July 2017 Revised 16 April 2018 Accepted 28 April 2018 KEYWORDS Sweden; Scandinavia; newspaper; qualitative research Introduction

In an era of“fake news” and ubiquitous information overload, the importance of quality journalism for safeguarding democracy as the 4th estate appears more important than ever. News media integrity and quality have been linked to media ownership, for example, by illustrating the damaging effects of short-term interests of investors (Picard,2005, p. 4) that change the managerial goals of publicly owned media companies (e.g., Cranberg, Bezanson, & Soloski,2001). Ownership by trusts and foundations, charitable organizations, or not-for-profit corporations has been advocated as an alternative by critics of the profit motivations of corporate and private owners (Picard & van Weezel, 2008, p. 27). However, research on such alternative types of ownership remains scarce (Levy & Picard,2011).

CONTACTLeona Achtenhagen acle@ju.se Jönköping International Business School (JIBS), Media, Management and Transformation Centre (MMTC), Jönköping University, PO Box 1026, Jönköping 55111, Sweden

https://doi.org/10.1080/14241277.2018.1482302

© 2018 Institute for Media and Communications Management

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way.

The aim of this article is to explore the corporate governance of news media owned by business foundations. In general terms, corporate govern-ance refers to how companies are directed and controlled (e.g., Picard,2005). Based on data generated through unique access to the key people in the corporate governance roles of three large Swedish newspaper groups, we shed light into the black box of foundation-based newspaper ownership by explor-ing its corporate governance specificities.

Next, we review relevant literature on media ownership in general and alternative forms of ownership in particular. After identifying the lack of research on the specificities of corporate governance in relation to different ownership forms, and especially business foundations, we then characterize the Swedish newspaper industry as an ideal context for our study, as almost one-third of the market is controlled by business foundations. Thereafter, we present the three case studies and a cross-case analysis. Finally, our conclusions sum up the advantages and disadvantages of foundation-based newspaper ownership.

Literature Media ownership

Media diversity plays an important role in upholding democracy as the 4th estate (e.g., Baker,2007; Schultz,1998). Thus, one main interest of studies on media ownership is to assess the relationship between ownership and media diversity (see Vizcarrondo, 2013). Throughout the world, scholars have critically discussed the increasing levels of media ownership concentration (e.g., Bagdikian,2000; Doyle,2002; Noam,2009) and also the difficulty of its measurement (e.g., Iosifidis, 2010).

Why does media ownership matter for media management? Ownership lies at the heart of corporate governance processes, imparting control over the steering of a media company’s activities (Ohlsson, 2012; Picard, 2005). Because of differences in institutional and external pressures from financial markets or local communities, Dunaway (2008) shows that privately owned media companies are managed differently from publicly owned media com-panies. Such pressures by the owners can also impact the information quality of the produced news (Dunaway, 2011) and the control of news content (Zhang,2010). Ghiglione (1996) claims that independent newspaper owners care more about their community than investors in publicly traded news-paper companies, who appear to be mainly interested in achieving profit margins and returns on investment (see also Fedler & Pennington, 2003). Nevertheless, research on the impact of different forms of ownership on news organizations remains scarce (Picard & van Weezel,2008).

Alternative forms of media ownership

Research on alternative forms of ownership has mainly focused on liberal media systems, such as those in the United Kingdom and the United States, with the aim of identifying sustainable bases for news media operations when purely commercial, for-profit enterprises have failed (e.g., Shaver, 2010). In an attempt to provide evidence of the potential for charitable and trust ownership, Levy and Picard (2011) present a book with cases from the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Russia, and France. In the same volume, Picard (2011) categorizes three types of ownership: (1) cha-rities owning news organizations, for example, to support types of coverage not readily available in other media; here, the news organizations are typi-cally operated as for-profit enterprises; (2) charities providing funding to news organizations for specific types of journalistic practices without owning or controlling them—with ProPublica in the United States as a prominent example, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting in 2010; and (3) trust ownership, which refers to when news organizations are placed in the hands of trustees who are obliged to operate them in certain ways. Trusts are created mainly to create managerial and editorial independence, and they typically control the fundamental values and strategic choices of the news organizations. In the United Kingdom, many such trusts were created between the 1940s and 1960s, including prominent examples such as the Guardian and The Economist.

Whereas most researchers agree that there is no specific form of ownership that will remedy the news crisis, current research efforts (beyond Levy & Picard, 2011) tend to be directed toward emerging business models rather than analyzing the forms of ownership or corporate governance issues. Matthews (2017) describes how a one-sided focus on revenues has caused local UK newspapers to neglect the needs of their local audiences. Other ownership forms, including employee-owned newspapers, have been suggested to provide better opportunities to cater to socio-local interests and needs. These observations are also echoed in the US market (e.g., Konieczna & Robinson, 2014), where charitable funding from the public, foundations and philanthropists is observed as an emerging phenomenon (Powers & Yaros,

2012). Globally, crowdfunding (Carvajal, García-Avilés, & González,2012) and other new business models have been explored for newspapers (for an over-view, see Breiner,2017). However, Picard (2014) highlights that the alternative forms of media ownership discussed so far—comprising charitable, commu-nity-owned, not-for profit operations—have failed to provide long-term finan-cial sustainability. Further, an analysis of the (dis)advantages of alternative forms of ownership also needs to include the contingencies of the respective media system, as any specific ownership model may be difficult to reproduce outside its legal and historical context (e.g., Levy & Picard, 2011). Therefore, we will next present the media system in Sweden.

The importance of the media system for ownership

The role and function of different types of media ownership must be under-stood in the context of its specific media system. Hallin and Mancini (2004) depict Sweden as an exemplar case of what they label the “North/Central European model.” Historically, this model is characterized by high news-paper circulation, high degrees of press freedom (Sweden was the first country in the world with a press freedom act), professional journalists, and relatively high degrees of political parallelism in commercial media markets. Although past ties to political parties generally have been cut, and actual political bias in news reporting is considered low (Brüggemann, Engesser, Büchel, Humprecht, & Castro, 2014), most Swedish commercial newspapers maintain a self-declared political label. This history of news-papers and their owners being driven by political agendas has made struc-tural pluralism, manifested through a diversity of independent newspapers, a central objective in designing media policies (Ots, 2013). This has been operationalized through an extensive press subsidy system, not only in Sweden but also in the surrounding Nordic countries (Ots, Krumsvik, Ala-Fossi, & Rendahl, 2016).

Over time, the North/Central European model as proposed by Hallin and Mancini (2004) has been moderated (Brüggemann et al., 2014), as media companies have become increasingly commercialized and in that process depoliticized (Weibull & Anshelm, 1991)—thereby approaching the liberal

media systems of the United States and the United Kingdom (see Cuilenberg & McQuail,2003). While Hallin and Mancini (2004) never explicitly discuss different private ownership forms and structures in media systems, they highlight the historical coexistence of strong political and cultural subcom-munities in northern and central European societies as a central factor in the diverse political affiliations of the press. As legacies of this era, private newspaper foundations can still be regarded as important structural factors for how diversity is organized at the macro level in these markets (see, e.g., Klimkiewicz, 2009).

Characteristics of business foundations

Somewhat resembling the trust-ownership arrangements of newspapers such as the Guardian (Keegan,2011) and the St. Petersburg Times (Dunlap,2011), Swedish newspaper foundations represent an understudied phenomenon. This distinct ownership form has been increasing in different countries and industries around the world as many owner-managers reach retirement age (see Wigand, Haase-Theobald, Heuel, & Stolte, 2015). Drawing on Thomsen and Rose (2004: 344), we define a business foundation as an organization created to administer a large ownership stake in a company (group) that is often donated by the company’s founder. The foundation itself is a nonprofit entity, as it has no owners.

Within media industries, foundation ownership has been discussed in the Swedish and Danish newspaper markets (Ohlsson, 2013; Olsson, 1996), but also in Germany, six of the largest media companies are foundation-owned (Gerum & Stieglitz,2005). The newspaper foundation has been described as an ideal type of owner by journalists (Asp & Weibull, 1996), yet it is rarely explored in academic research (Picard & van Weezel, 2008).

Characteristic of foundation ownership is the absence of a physical person as owner, its objective-driven purpose (rather than profit maximization), and its inability to be dissolved (Thomsen & Rose, 2004). The charter of the foundation stipulates the principles guiding how the capital should be admi-nistered and for what purposes (see also Ohlsson, 2013), and it also defines the composition of the board of directors of the foundation to manage the enactment of the foundation’s principles in the operations of the newspaper firm(s) owned by the foundation. In Sweden, foundations represent a grow-ing form of ownership of commercial media firms. Typically, foundations are created to safeguard a political orientation (Ohlsson,2013) or family interests (Gerum & Stieglitz, 2005) with a long-term perspective. While being oper-ated as professional, commercial, for-profit entities, their returns are rein-vested into the operations, the journalism, and/or the community.

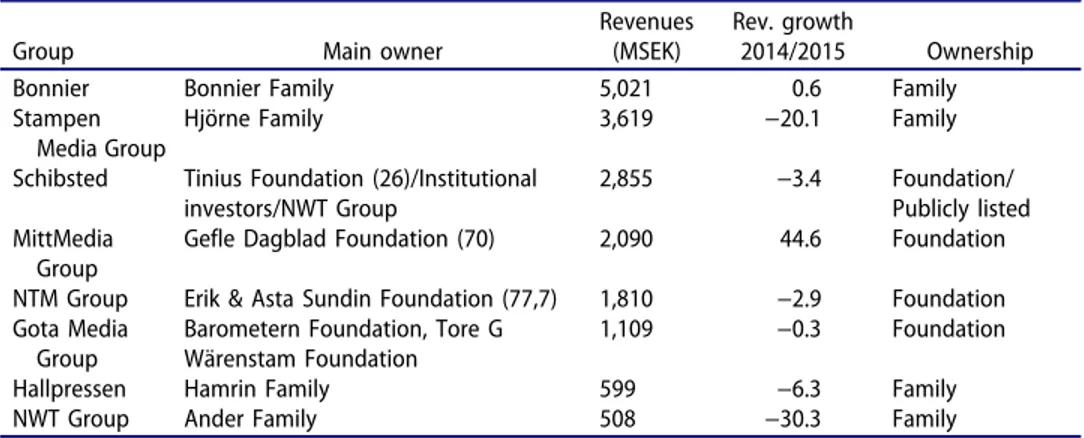

The Swedish newspaper industry

The Swedish newspaper industry is highly concentrated and dominated by eight owners who control close to 90% of the total revenues (see Table 1). These eight owners have largely divided the press among themselves in terms of geography and publication types. Family-owned Bonnier and publicly listed Schibsted control the entire market for national evening tabloids (Expressen, GT, Kvällsposten and Aftonbladet) and the metropolitan/national

Table 1.Largest owners in the Swedish newspaper market 2015.

Group Main owner

Revenues (MSEK)

Rev. growth

2014/2015 Ownership Bonnier Bonnier Family 5,021 0.6 Family Stampen

Media Group

Hjörne Family 3,619 −20.1 Family Schibsted Tinius Foundation (26)/Institutional

investors/NWT Group

2,855 −3.4 Foundation/ Publicly listed MittMedia

Group

Gefle Dagblad Foundation (70) 2,090 44.6 Foundation NTM Group Erik & Asta Sundin Foundation (77,7) 1,810 −2.9 Foundation Gota Media

Group

Barometern Foundation, Tore G Wärenstam Foundation

1,109 −0.3 Foundation Hallpressen Hamrin Family 599 −6.3 Family NWT Group Ander Family 508 −30.3 Family Source: Medieekonomi 2016, Myndigheten för Press, Radio och TV

market for quality press based in Stockholm (Dagens Nyheter and Svenska Dagbladet), and they have established strong positions online. The remaining six groups are all active in the regional press, where they have obtained dominance in their respective geographical niche markets. Three of these groups are family-owned (Stampen, Hallpressen and NWT), whereas three are owned by foundations (MittMedia, NTM Group and Gota Media).

For decades, the Swedish newspaper market was very strong, with 85% daily readership among the adult population (Nordicom, 2017). However, similar to many other nations, the printed press has declined steadily since its peak in the early 1990s: Decreasing circulation figures, decreasing advertising sales, and increasing competition from national broadcasting companies and global online giants caused a 25% drop in total newspaper industry revenues between 2008 and 2014 (MRTV, 2015).

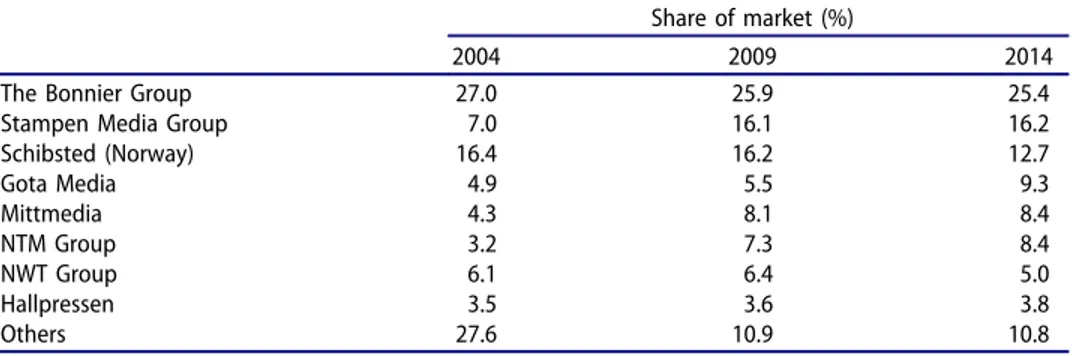

This decline has ignited far-reaching structural changes. As smaller own-ers, notably families and political parties, have divested some of their news-papers, control over the newspaper market has become even more concentrated in the eight largest owners, who increased their share of the market from 72.4% to 89.8% between 2004 and 2014 (see Table 2).

However, the expansion strategies of the largest owners differ. The national players Bonnier and Schibsted have directed their attention to digital initiatives, allowing their market shares of printed newspapers to decline. Meanwhile, the regional press, headed by the three large founda-tion-owned groups (MittMedia, NTM Group and Gota Media) along with family-owned Stampen Group, have expanded through a wave of acquisi-tions (Gustafsson, 2010; Melesko, 2010; Ots, 2012). As a result, the three foundation-owned newspaper groups doubled their market shares over a 10-year period, controlling over 26% of the newspaper market in 2014 (see Table 2). The trend toward foundation ownership continued in 2015, when MittMedia’s revenues surged by 44% after acquiring different news-paper titles from Stampen Media Group (see Table 1).

Table 2.Market share development 2004–2014, eight largest newspaper owners.

Share of market (%)

2004 2009 2014

The Bonnier Group 27.0 25.9 25.4

Stampen Media Group 7.0 16.1 16.2

Schibsted (Norway) 16.4 16.2 12.7 Gota Media 4.9 5.5 9.3 Mittmedia 4.3 8.1 8.4 NTM Group 3.2 7.3 8.4 NWT Group 6.1 6.4 5.0 Hallpressen 3.5 3.6 3.8 Others 27.6 10.9 10.8

Method

The previous section showed that three of the eight large newspaper owners in Sweden are foundations, jointly covering over 26% of the market. Business foundations pose an interesting ownership case, as the foundations are based on the endowment of the original shares in the company, and thus there is no actual owner of the foundation. To explore the implications of this form of ownership on corporate governance practices, we conducted case studies on each of the three Swedish foundation-owned newspaper groups. In each group, we interviewed the chairman of the board of the foundation, the chairman of the board of the operating company and the CEO of the operating company as the key actors involved in the main corporate govern-ance practices of controlling and steering. Thus, nine interviews were carried out, each lasting at least one hour. The interviews were guided by an inter-view pro forma that was designed to capture the characteristics of the foundation’s organization and corporate governance practices, including the relations between the foundation and the operating companies, the local anchoring and the execution of ownership control. All interviews were first individually analyzed by each author before comparing and inte-grating our individual analyses. This analysis involved several iterations between empirical data and the (media) ownership literature (see Eisenhardt, 1989). Our qualitative, comparative case-study approach allows us to not only understand corporate governance practices across several organizations but also identify the advantages and disadvantages of this form of ownership (e.g., Khan & van Wynsberghe, 2008).

Empirical findings Gota Media

Gota Media (GM) was officially created in 2003 when the two regional, foundation-owned newspaper companies Borås Tidning AB and Sydostpress merged after 5 years of increasing collaboration. Today, the group owns 13 newspapers and 7 freesheets, and it also holds a range of partial ownerships in other newspapers and media-related companies. The company group has continued to expand through acquisitions. Its news-papers are concentrated in western and southeastern Sweden. For 2015, the company group reported a balanced budget and achieved an ROE of 1.88%. Its financial solidity, represented by the asset-based solvency ratio (i.e., shareholder funds/total assets), was 63% (seeTable 3), indicating that overall the company group is in a financially strong, sustainable position, which explains its rather slow pace of digital transformation.

On its webpage, GM describes itself as follows: “The company group Gota Media is based on strong journalistic values, and on behalf of its owners, it aims to

Table 3. Gota Media AB. Key financials and employees Consolidated 31/12/2015 31/12/2014 31/12/2013 31/12/2012 31/12/2011 31/12/2010 31/12/2009 31/12/2008 31/12/2007 th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Exchange rate: SEK/EUR 0.10882 0.10646 0.11288 0.11652 0.11221 0.11148 0.09754 0.09200 0.10592 Operating revenue (Turnover) 1,21,169 1,19,023 1,29,216 1,43,612 1,17,859 99,082 80,835 79,738 90,635 P/L before tax 1,628 − 8,739 1,265 513 11,327 14,222 8,272 581 14,169 P/L for period [= Net Income] − 14 − 10,012 146 488 7,947 10,470 6,196 359 9,970 Cash flow 7,648 8,229 5,719 6,549 12,386 14,412 9,718 3,698 13,993 Total assets 1,36,718 1,44,738 1,62,760 1,71,436 1,66,939 1,43,032 1,20,336 1,14,061 1,31,451 Shareholders funds 86,481 85,419 1,04,123 1,07,979 1,04,194 98,627 82,612 74,781 86,303 Current ratio (x) 2.75 2.43 2.78 2.65 2.20 3.88 3.79 3.82 3.79 Profit margin (%) 1.34 − 7.34 0.98 0.36 9.61 14.35 10.23 0.73 15.63 ROE using P/L before tax (%) 1.88 − 10.23 1.22 0.48 10.87 14.42 10.01 0.78 16.42 ROCE using P/L before tax (%) 2.13 − 8.23 1.11 0.58 9.32 12.37 8.74 1.44 13.78 Solvency ratio (Asset based) (%) 63.26 59.02 63.97 62.99 62.41 68.96 68.65 65.56 65.65 Number of employees 777 814 860 979 777 642 589 623 633 Global standard format Balance sheet Consolidated 31/12/2015 31/12/2014 31/12/2013 31/12/2012 31/12/2011 31/12/2010 31/12/2009 31/12/2008 31/12/2007 th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Exchange rate: SEK/EUR 0.10882 0.10646 0.11288 0.11652 0.11221 0.11148 0.09754 0.09200 0.10592 Assets Fixed assets 43,663 49,530 63,906 68,927 73,640 38,647 35,438 37,452 44,024 -Intangible fixed assets 8,683 7,792 27,325 30,148 30,009 820 574 29 0 -Tangible fixed assets 23,330 26,997 27,540 31,552 35,715 31,758 31,276 31,912 39,160 -Other fixed assets 11,651 14,741 9,041 7,227 7,916 6,069 3,58 75,512 4,864 Current assets 93,055 95,208 98,854 1,02,509 93,299 1,04,386 84,898 76,608 87,427 -Stock 266 274 298 388 331 489 335 330 329 -Debtors 6,898 7,576 7,444 9,354 10,120 6,689 4,984 3,837 5,746 -Other current assets 85,891 87,357 91,112 92,767 82,849 97,207 79,580 72,442 81,352 * Cash & cash equivalent 3,339 3,385 4,128 9,199 6,960 11,819 8,408 9,741 9,360 TOTAL ASSETS 1,36,718 1,44,738 1,62,760 1,71,436 1,66,939 1,43,032 1,20,336 1,14,061 1,31,451 (Continued )

Table 3. (Continued). Key financials and employees Liabilities and equity Shareholders funds 86,481 85,419 1,04,123 1,07,979 1,04,194 98,627 82,612 74,781 86,303 -Capital 3,265 3,194 3,386 3,496 3,366 3,344 2,926 2,760 3,177 -Other shareholders funds 83,216 82,225 1,00,736 1,04,484 1,00,827 95,283 79,686 72,021 83,125 Non-current liabilities 16,357 20,051 23,127 24,711 20,279 17,510 15,341 19,220 22,064 -Long-term debt 3,886 4,881 6,257 7,537 8,258 9,129 8,804 13,638 16,518 -Other non-current liabilities 12,471 15,170 16,870 17,174 12,021 8,382 6,537 5,582 5,546 * Provisions 12,013 14,498 15,920 15,926 10,841 8,372 6,537 5,582 5,546 Current liabilities 33,880 39,267 35,510 38,746 42,466 26,895 22,382 20,061 23,084 -Loans 1,311 1,244 1,044 1,039 1,088 923 779 709 787 -Creditors 2,573 3,521 3,638 7,182 7,897 3,860 2,685 3,004 3,019 -Other current liabilities 29,997 34,502 30,828 30,525 33,482 22,112 18,918 16,347 19,278 TOTAL SHAREH. FUNDS & LIAB. 1,36,718 1,44,738 1,62,760 1,71,436 1,66,939 1,43,032 1,20,336 1,14,061 1,31,451 Memo lines Working capital 4,591 4,329 4,104 2,560 2,554 3,318 2,634 1,163 3,056 Net current assets 59,175 55,940 63,344 63,763 50,833 77,491 62,516 56,548 64,343 Enterprise value n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. Number of employees 777 814 860 979 777 642 589 623 633 Profit and loss account Consolidated 31/12/2015 31/12/2014 31/12/2013 31/12/2012 31/12/2011 31/12/2010 31/12/2009 31/12/2008 31/12/2007 th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Exchange rate: SEK/EUR 0.10882 0.10646 0.11288 0.11652 0.11221 0.11148 0.09754 0.09200 0.10592 Operating revenue (Turnover) 1,21,169 1,19,023 1,29,216 1,43,612 1,17,859 99,082 80,835 79,738 90,635 -Sales 1,16,911 1,16,714 1,27,969 1,41,991 1,15,772 97,060 79,006 78,106 89,929 Costs of goods sold n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. Gross profit n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. Other operating expenses n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. Operating P/L [=EBIT] − 1,322 − 12,744 − 3,880 − 2,445 8,792 10,762 3,280 5,187 10,320 -Financial revenue 4,254 4,380 5,286 3,208 2,802 3,606 5,285 1,915 4,616 -Financial expenses 1,304 375 142 250 267 145 292 6,522 767 Financial P/L 2,950 4,005 5,144 2,958 2,536 3,460 4,992 –4,606 3,849 P/L before tax 1,628 − 8,739 1,265 513 11,327 14,222 8,272 581 14,169 (Continued )

Table 3. (Continued). Key financials and employees Taxation 1,642 1,273 1,119 25 3,380 3,752 2,077 222 4,198 P/L after tax − 14 − 10,012 146 488 7,947 10,470 6,196 359 9,970 -Extr. and other revenue n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. 0 0 0 -Extr. and other expenses n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. 0 0 0 Extr. and other P/L n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. 0 0 0 P/L for period [=Net income] − 14 − 10,012 146 488 7,947 10,470 6,196 359 9,970 Memo lines Export revenue n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. Material costs 15,982 18,141 21,787 27,575 20,628 17,031 n.a. n.a. n.a. Costs of employees 53,225 50,860 58,955 60,586 44,541 37,240 33,101 31,007 33,755 Depreciation & Amortization 7,662 18,241 5,574 6,060 4,439 3,942 3,52 23,339 4,023 Research & Development expenses n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. Other operating items 45,621 44,526 46,780 51,836 n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. Interest paid 564 56 142 250 267 145 292 769 767 Cash flow 7,648 8,229 5,719 6,549 12,386 14,412 9,718 3,698 13,993 Added value 63,079 60,418 65,935 67,409 60,575 55,550 45,188 35,696 52,713 EBITDA 6,340 5,497 1,694 3,616 13,231 14,704 6,803 8,527 14,343 Global ratios Consolidated 31/12/2015 31/12/2014 31/12/2013 31/12/2012 31/12/2011 31/12/2010 31/12/2009 31/12/2008 31/12/2007 th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Exchange rate: SEK/EUR 0.10882 0.10646 0.11288 0.11652 0.11221 0.11148 0.09754 0.09200 0.10592 Profitability ratios ROE using P/L before tax (%) 1.88 − 10.23 1.22 0.48 10.87 14.42 10.01 0.78 16.42 ROCE using P/L before tax (%) 2.13 − 8.23 1.11 0.58 9.32 12.37 8.74 1.44 13.78 ROA using P/L before tax (%) 1.19 − 6.04 0.78 0.30 6.79 9.94 6.87 0.51 10.78 ROE using Net income (%) − 0.02 − 11.72 0.14 0.45 7.63 10.62 7.50 0.48 11.55 ROCE using Net income (%) 0.54 − 9.44 0.23 0.56 6.60 9.14 6.62 1.20 9.91 ROA using Net income (%) − 0.01 − 6.92 0.09 0.29 4.76 7.32 5.15 0.32 7.59 Profit margin (%) 1.34 − 7.34 0.98 0.36 9.61 14.35 10.23 0.73 15.63 Gross Margin (%) n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. (Continued )

Table 3. (Continued). Key financials and employees EBITDA Margin (%) 5.23 4.62 1.31 2.52 11.23 14.84 8.42 10.69 15.83 EBIT Margin (%) − 1.09 − 10.71 − 3.00 − 1.70 7.46 10.86 4.06 6.51 11.39 Cash flow/Operating revenue (%) 6.31 6.91 4.43 4.56 10.51 14.55 12.02 4.64 15.44 Enterprise value/EBITDA (x) n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. Operational ratios Net assets turnover (x) 1.18 1.13 1.01 1.08 0.95 0.85 0.83 0.85 0.84 Interest cover (x) − 2.34 n.s. − 27.34 − 9.80 32.98 73.98 11.22 6.75 13.45 Stock turnover (x) 455.97 434.17 432.95 369.78 356.06 202.47 241.54 241.91 275.51 Collection period (days) 20 23 21 23 31 24 22 17 23 Credit period (days) 8 11 10 18 24 14 12 14 12 Export revenue/Operating revenue (%) n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. R&D expenses/Operating revenue (%) n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. Structure ratios Current ratio (x) 2.75 2.43 2.78 2.65 2.20 3.88 3.79 3.82 3.79 Liquidity ratio (x) 2.74 2.42 2.78 2.64 2.19 3.86 3.78 3.80 3.77 Shareholders liquidity ratio (x) 5.29 4.26 4.50 4.37 5.14 5.63 5.39 3.89 3.91 Solvency ratio (Asset based) (%) 63.26 59.02 63.97 62.99 62.41 68.96 68.65 65.56 65.65 Solvency ratio (Liability based) (%) n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s. n.a. n.a. n.a. Gearing (%) 20.43 24.93 23.21 23.85 20.51 18.69 19.51 26.65 26.48 Per employee ratios Profit per employee (th.) 2 − 11 1 1 15 22 14 1 22 Operating revenue per employee (th.) 156 146 150 147 152 154 137 128 143 Costs of employees/Operating revenue (%) 43.93 42.73 45.63 42.19 37.79 37.59 40.95 38.89 37.24 Average cost of employee (th.) 69 62 69 62 57 58 56 50 53 Shareholders funds per employee (th.) 111 105 121 110 134 154 140 120 136 Working capital per employee (th.) 6 5 53354 2 5 Total assets per employee (th.) 176 178 189 175 215 223 204 183 208

play an important role in keeping democracy alive and active” (www.gotamedia.se;

our translation). In 2013, these values were formalized in a strategy document that specified the factors that should be decisive in Gota Media’s work, focusing on traditional journalism: news, opinion building, information, investigation and education through building on a strong local presence and close relationships with readers, customers and other actors. The CEO further explained the role of this mission in steering GM’s work: “In our long-term, strategic considerations, we focus on journalistic values and commitments as they are presented in the mission statement”. GM’s tight links to the local community aim to capture topics of interest to readers and to support their opinion-building. Indeed, our interviewees argued that GM can leverage its dominant position as an opinion-builder to set the agenda in local debates.

Two foundations, Stiftelsen Barometern and Tore G. Wärenstams Stiftelse each own 50% of the company group.1Both foundations clearly express their commitment to upholding the 4th estate. They were originally created to secure access to a free and independent press as expressed in the foundations’ charters, which vowed to guarantee a long-term orientation. The Chairman of GM’s Board confirmed, “The foundation-based form of ownership creates a long-term perspective that avoids all the pitfalls that a focus on quarterly reports implies.”

As outlined earlier, newspapers in Sweden historically tended to have a clear political orientation. GM’s foundations were linked to the conservative party (Moderaterna), but even liberal and social-democrat newspapers are now part of the group. Our interview data show that no ambitions exist in the group to direct these different newspapers in the same political direction, which reflects the principle of giving voice to different opinions to uphold democracy.

Regarding corporate governance practices, the chairman of GM’s nonexe-cutive board of directors explained, “The foundations have a long-term perspective on their newspaper ownership. Those, in turn, are bound to their mission – which in modernized form and interpretation – is based on the founders’ intentions.” This mission has strong implications for the profit orientation of the company. A common phrase used both by top manage-ment and the board– and thus repeated in all three interviews – is “We don’t publish newspapers to make money. We make money to be able to publish newspapers.” This need was further explained by the CEO: “Good journalism requires resources. A healthy financial situation is a prerequisite to maintain strong newsrooms with competent employees. The journalistic task is inde-pendent of the channel but completely deinde-pendent on the channel generating enough revenues to finance its operations. For the foreseeable future, the printed newspaper will remain the dominant basis for both GM’s revenues as well as its journalistic operations.”

In addition to these steering practices, the control function is relevant for the corporate governance of this foundation-based ownership type. The

Chairman of GM’s board explained, “It is essential that the composition of the board and its collective competence controls that the mission of the foundation is followed and that it restricts the risks related to executive independence. This implies frequent contacts between the foundations and the top management.” The required level of competence of board members as a prerequisite for functioning corporate governance practices was also confirmed by the deputy chairman of the Barometer foundation: “A crucial factor is the composition and the selection of members of the board of the foundation in order to exert its influence within the GM company board.” Mitt Media

MittMedia (MM) originated with the newspaper Gefle Dagblad, which was started in 1895 “to protect sobriety and to fight nonchalance.” When MM was founded in 2003, five newspapers were included in the company group. During the same year, two further newspapers were acquired. In 2005, MM was one of the buyers when the Swedish Center Party sold its dailies—a deal that profoundly restructured the Swedish newspaper market. MittMedia took over four dailies and has since added another six newspapers. The chairman of the Foundation, Nya Stiftelsen Gefle Dagblad, elaborated on this strategy of expansion:“The decision to grow by acquisitions was taken 25 years ago”. Today, MM’s business activities comprise 28 newspapers, free sheets, digital media, commercial radio, internet TV, a digital media bureau, printing and apps. Its financial development is depicted inTable 4.

MittMedia aims to be “Sweden’s most credible supplier of journalism with a local perspective and to contribute to a well-informed society where knowledge and understanding foster dialogue, engagement and democracy” (www.mittmedia.se;our translation). In addition, it wants to be available to readers not only around the clock but also in readers’ channel of choice.

MittMedia is owned by Nya Stiftelsen Gefle Dagblad (70%) and by Stiftelsen Pressorganisation (30%). The chairman of the board of MM stated, “The foundation-based form of ownership is generally somewhat old-fashioned, but it is an excellent form of ownership for newspapers to avoid ownership complications.” Both foundations were initially based on the ideology promoted by the liberal party, Folkpartiet. After different acquisitions, the group now also includes newspapers and online sites that represent other political orientations. For example, a recent acquisi-tion was conducted to save a social-democratic newspaper from extinc-tion. This deal was justified based on its potential for gaining synergies in a shrinking newspaper market, thereby overriding the objective of the Gefle Dagblad foundation—stated in its charter—to safeguard a liberal political ideology among the newspapers of the group. Additionally, the minority-owner Pressorganisation’s charter stipulates that in order to

Table 4. MittMedia Förvaltnings AB. Key financials and employees No of recorded shareholders 1 Consolidated 31/12/2015 31/12/2014 31/12/2013 31/12/2012 31/12/2011 31/12/2010 31/12/2009 31/12/2008 31/12/2007 th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Exchange rate: SEK/EUR 0.10882 0.10646 0.11288 0.11652 0.11221 0.11148 0.09754 0.09200 0.10592 Operating revenue (Turnover) 2,27,427 1,53,886 1,63,660 1,79,147 1,83,375 1,81,748 1,55,924 1,53,622 1,45,676 P/L before tax 5,541 5,200 − 23,768 8,153 − 3,660 5,768 28 6,814 39,176 P/L for period [= Net Income] 3,736 3,655 − 22,640 5,524 − 5,952 3,683 − 1,090 5,339 36,335 Cash flow 20,609 8,918 − 12,553 16,176 10,911 13,132 7,751 14,164 43,528 Total assets 1,77,626 1,28,782 1,51,368 1,78,285 1,80,963 1,89,664 1,63,920 1,69,723 1,47,953 Shareholders funds 71,536 58,969 64,320 90,396 92,861 98,725 83,793 80,553 87,034 Current ratio (x) 0.46 0.41 0.44 0.46 0.40 0.43 0.46 0.60 0.63 Profit margin (%) 2.44 3.38 − 14.52 4.55 − 2.00 3.17 0.02 4.44 26.89 ROE using P/L before tax (%) 7.75 8.82 − 36.95 9.02 − 3.94 5.84 0.03 8.46 45.01 ROCE using P/L before tax (%) 6.76 8.22 − 26.85 7.58 − 2.08 5.10 0.71 7.35 39.33 Solvency ratio (Asset based) (%) 40.27 45.79 42.49 50.70 51.32 52.05 51.12 47.46 58.83 Number of employees 1,771 974 1,055 1,330 1,869 1,888 1,773 1,731 1,483 Source: Amadeus database, compiled December 26, 2017

safeguard the future publishing of newspapers, the foundation must acquire and own stock in newspaper companies that are affiliated with the political views expressed by the liberal party and to direct its other publishing activities in the same spirit. However, the chairman of the board explained that this stipulated political orientation is subject to business principles: “We are willing to accept affiliations with other parties in order to sustain the equity that will enable us to continue growing.”

Both foundations’ charters stipulate that profits should be reinvested into the business activities. MM’s strategy aims to achieve synergies and econo-mies of scale through centralized decision-making. To succeed with this aim, all the acquired newspapers companies have been merged, even though this approach weakens the ties between the individual newspapers and their local communities.

NTM

Norrköpings Tidningar Media (NTM) is a media group with roots in Sweden’s oldest remaining newspaper, Norrköpings Tidningar, founded in 1758. The current structure of the group was shaped in 2008, when the large regional daily Östgöta Correspondenten was acquired. The headquarters are located in the city of Norrköping, 160 km south of Stockholm. The company still specializes in regional media, although over the years, operations have expanded to include a large number of regional and local newspapers, free-sheets, digital media, weeklies, radio stations, distribution companies, print-ing operations and events, and travel services.

Like Mittmedia and Gota Media, NTM has been particularly active in M&A activities since the turn of the millennium, taking advantage of the declining newspaper market by acquiring various regional media companies and creating production synergies. With 1400 employees and a turnover of 1810 million SEK (EUR 200M) in 2015, NTM has managed to maintain its revenues and circulation better than most of its competitors. So far, the group is financially stable, and the decrease in newspaper circulation and advertising revenues has not hit its cash flow, thereby providing NTM the reputation as a skillful player under difficult market conditions (seeTable 5). However, unlike GM and MM, which largely expanded geographically into adjacent regions, NTM is operating in four disconnected regions: south and north of Stockholm, the far north of Sweden, and the island of Gotland in the Baltic sea.

Since 1947, the majority owner of Norrköpings Tidningar is Erik & Asta Sundin stiftelse, who today own 78% of NTM.2 The foundation was created according to the will of Asta Sundin to fund support and charity activities for elderly and sick people in the city of Norrköping. Thus, the main goal of the

Table 5. Norrköpings Tidningars Media AB. Key financials and employees Consolidated 31/12/2015 31/12/2014 31/12/2013 31/12/2012 31/12/2011 31/12/2010 31/12/2009 31/12/2008 th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR th EUR 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months 12 months Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAp Local GAAP Local GAAP Local GAAP Exchange rate: SEK/EUR 0.10882 0.10646 0.11288 0.11652 0.11221 0.11148 0.09754 0.09200 Operating revenue (Turnover) 1,96,951 1,98,552 2,05,507 2,13,963 2,03,308 1,95,870 1,17,720 77,064 P/L before tax − 8,551 − 6,603 6,228 6,550 9,515 9,348 2,897 − 1,800 P/L for period [= Net Income] − 8,523 − 7,150 4,317 6,743 5,707 5,937 1,205 − 2,895 Cash flow 9,374 11,784 19,074 21,441 18,931 18,469 10,758 2,891 Total assets 2,07,274 2,25,445 2,81,409 2,82,612 2,64,884 2,53,667 1,78,331 1,70,925 Shareholders funds 1,14,491 1,23,553 1,72,054 1,80,728 1,74,446 1,75,060 1,27,674 1,22,397 Current ratio (x) 2.19 1.92 1.67 2.14 1.65 1.92 1.78 1.60 Profit margin (%) − 4.34 − 3.33 3.03 3.06 4.68 4.77 2.46 − 2.34 ROE using P/L before tax (%) − 7.47 − 5.35 3.62 3.62 5.45 5.34 2.27 − 1.47 ROCE using P/L before tax (%) − 5.49 − 3.78 3.48 3.25 4.87 4.88 2.16 − 0.49 Solvency ratio (Asset based) (%) 55.24 54.80 61.14 63.95 65.86 69.01 71.59 71.61 Number of employees 1,390 1,464 1,458 1,463 1,514 1,494 1,077 890 Source: Amadeus database, compiled December 26, 2017

foundation is to leverage its business activities to be able to provide these benefits—meaning that the main objective is not to publish newspapers. As majority owner, the Erik & Asta Sundin foundation provides a substantial amount of freedom to NTM’s management to steer its media activities. The foundation’s statutes do not stipulate that investments must be made with any political purpose, with any specific publishing agenda, or in any specific media channel; thus, ownership’s control of media-business activities is less pronounced than in the other two cases. The charter also does not specify a required rate of return for the foundation’s investments. In fact, the founda-tion does not even restrict investments to any specific industry sector. This has enabled NTM, for instance, to invest in real estate. However, because the foundation’s capital comes from its majority share in the newspaper Norrköpings Tidningar, the CEO explained that due to this legacy, “we make the interpretation that it is within our objective to keep publishing.” Over the years, NTM has broadened its portfolio to hold a range of news-paper titles with different political affiliations.

Regarding its corporate governance practices, the chairman of the board of NTM explained that “the professionalism of the management of the group displays the characteristics you would expect from a well-performing com-pany,” and the chairman of the foundation noted that “the strategy is developed independently of the ownership form.” However, this is certainly aided by his assessment of the current situation:“We are a rich foundation.”

Discussion

In a period of industry crisis, and unlike most of their competitors, the foundation-owned newspaper groups in Sweden managed to expand their activities with sustainable financial results (see Tables 1 and 2). This is remarkable given that the foundations’ ownership, with strategic goals stipu-lated in their charters, pursues goals other than profit maximization. The three company groups’ expansion strategies were focused on the regional newspaper market that, while shrinking in overall size, included few direct competitors.

In all three cases, the companies’ growth was the result of a combination of organic growth and M&As. The acquisitions focused mainly on taking over newspapers previously owned by political parties or families. Different strategic logics of integrating the acquired targets into their operations were applied. MM and GM expanded geographically into adjacent regions and attempted to gain synergies in production, distribution and sales. NTM combined its geographic expansion into detached regions with a focus on cost reduction through tight administrative coordination—a challenging task, given that operations were phy-sically dispersed. The differences in acquisition strategies between the three groups are a result of their corporate governance practices, which are directly linked to their foundations’ charters. MM and GM have charters that demand a local or

regional orientation of media activities supporting the 4th estate by providing additional journalistic voices to nurture democracy. NTM’s charter more loosely relates to the location of the company’s headquarters and provides more strategic freedom, as the foundation’s core aim is not journalistically driven. Instead, it is the interpretation of the importance of the press-media legacy by the board and top management that fosters the continued long-term commitment to journalism.

The difference in the speed of “going digital” cannot be attributed to the foundations’ charters. Within MM’s portfolio of newspapers, some have a rather weak financial situation—they were acquired with the aim of uphold-ing the 4th estate and gainuphold-ing synergies across different newspapers. An internal analysis of the overall financial situation thus led to the decision to quickly introduce digital solutions. GM’s board and management team have a more risk-averse attitude, which has led to a slower pace of change. NMT, with its larger strategic scope, is not restricted to media business activities and can thus more easily invest in other profitable opportunities that can cross-subsidize its journalistic endeavors.

The main impact of foundation ownership on the newspaper companies is characterized by the long-term commitments stipulated by the foundations’ charters. The commitment to upholding the 4th estate through providing different journalistic voices is especially pronounced in GM and MM. The commitment to a local presence as important actors in local debates and agenda-setting is highly manifested within all three cases.

Conclusions

This article has explored the corporate governance of the ownership form of business foundations—a type of ownership that is increasing in different countries around the world. Based on an analysis of three business foundations in the Swedish newspaper sector that together represent 26% of the market, we have shown the relevance of the corporate governance practice of a long-term ownership orientation, which has played a crucial role in positively expanding the newspaper companies’ activities in comparison to their competitors (see

Tables 1and2). Foundations can represent different types of owner interests—

for example, political, business and journalistic interests with a strong local or regional anchoring but also the aim of conserving the majority owners’ personal interests. The foundation’s responsibility is to balance the demands posed by these interests with viable business activities that secure the survival of the companies as vehicles for fulfilling these interests.

Our results outline several advantages of foundation-based ownership. This type of ownership provides companies with stability and a long-term strategic intent, where strategic decisions are not restricted by the demand for quick pay-offs. This freedom has allowed firms to follow strategic visions that truly connect the companies with their local communities, resulting in strong local

connections and high journalistic ambitions. Here, upholding the 4th estate is an important basis for the foundations’ strategic decisions, and not profitability per se; profitability is instead seen as a means to produce journalistic content.

Thus, foundation-based newspaper ownership has a variety of advantages, the most important being ownership stability, local anchoring and securing high-quality journalistic voices to support democracy. This ownership stability makes it almost impossible for the newspaper companies to become take-over targets themselves—thereby facilitating the survival of diverse journalistic voices.

A potential weakness of this ownership form is related to the business compe-tence of the members of the foundations’ boards and top management. In an earlier study, Melesko (2000) found that the financial performance of foundation-owned companies was inferior to that of newspapers with other types of owner-ship. Through professionalizing the foundation boards and bringing in highly competent top managers—noted as highly relevant by all interviewees—the foun-dations are now instead outperforming their industry peers as indicated by balance sheets and market share growth rates (seeTables 1and2), as the control function performed by the foundations’ ownership allows them to leverage their long-term orientation.

A possible disadvantage of foundation ownership relates to limited oppor-tunities to finance growth, since the foundations’ original holdings cannot be sold, and their original capital cannot be easily diluted. The foundations in all three cases have struggled to increase their flexibility by setting up daughter companies in which external coownership is possible.

The success of foundation ownership of newspapers in Sweden sug-gests that it might be worthwhile to consider as an ownership form in other contexts, as the legal framework already exists in many countries.

Notes

1. Stiftelse is the Swedish word for foundation.

2. In 2009, a merger with the regional media group UNT resulted in UNT receiving a 22% minority share in NTM.

ORCID

Leona Achtenhagen http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7415-7519 Mart Ots http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0301-9765

References

Asp, K., & Weibull, L. (1996). Svenska journalister om mångfald och medier [Swedish journal-ists about diversity and media]. Stockholm, Sweden: Rådet för mångfald inom massmedierna.

Baker, C. E. (2007). Media concentration and democracy: Why ownership matters. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Breiner, J. (2017). Mapping the world’s digital media ecosystem: The quest for sustainability. In P. Berglez, U. Olausson, & M. Ots (Eds.), What is sustainable journalism?: Integrating the environ-mental, social, and economic challenges of journalism (pp. 257–276). Peter Lang Publishing Group.

Brüggemann, M., Engesser, S., Büchel, F., Humprecht, E., & Castro, L. (2014). Hallin and Mancini revisited: Four empirical types of western media systems. Journal of Communication, 64(6), 1037–1065. doi:10.1111/jcom.12127

Carvajal, M., García-Avilés, J. A., & González, J. L. (2012). Crowdfunding and non-profit media. Journalism Practice, 6(5–6), 638–647. doi:10.1080/17512786.2012.667267

Cranberg, G., Bezanson, R., & Soloski, J. (2001). Taking stock: Journalism and the publicly traded newspaper company. Ames, Berlin: Iowa State University Press, Iowa, USA. Cuilenberg, J., & McQuail, D. (2003). Media policy paradigm shifts towards a new

commu-nications policy paradigm. European Journal of Communication, 18(2), 181. doi:10.1177/ 0267323103018002002

Doyle, G. (2002). Media ownership: The economics and politics of convergence and concentra-tion. London/Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage.

Dunaway, J. (2008). Markets, ownership, and the quality of campaign news coverage. Journal of Politics, 70(4), 1193–1202. doi:10.1017/S0022381608081140

Dunaway, J. (2011). Institutional effects on the information quality of campaign news. Journalism Studies, 12, 27–44. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2010.511947

Dunlap, K. (2011). The poynter institute preserves the St Petersburg Times. (Levy & Picard, Eds.) (pp. 73–78).

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of

Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. doi:10.5465/amr.1989.4308385

Fedler, F., & Pennington, R. (2003). Employee-owned dailies: The triumph of economic self interest over journalistic ideals. International Journal on Media Management, 5(4), 262– 274. doi:10.1080/14241270309390042

Gerum, E., & Stieglitz, N. (2005). Corporate governance, ownership structures, and corporate strategy of media companies: The German experience. In R. G. Picard (ed.), Corporate governance of media companies, JIBS Research Report Series No. 2005-1 (pp. 127–146). Jönköping, Sweden: Jönköping International Business School.

Ghiglione, L. (1996, July/August). The price of independence. Presstime, 39.

Gustafsson, K. E. (2010). Bloc-building in the Swedish newspaper industry since its begin-nings. In O. Hultén, S. Tjernström, & S. Melesko (Eds.), Media mergers and the defence of pluralism (pp. 75–82). Gothenburg, Sweden: Nordicom.

Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Iosifidis, P. (2010). Pluralism and concentration of media ownership: Measurement issues. Javnost–The Public, 17(3), 5–22. doi:10.1080/13183222.2010.11009033

Keegan, V. (2011). Protecting the guardian through the Scott Trust (Levy & Picard, Eds.) (pp. 57–66). Khan, S., & van Wynsberghe, R. (2008). Cultivating the under-mined: Cross-case analysis as

knowledge mobilization. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(1), 1–21, Art. 34.

Klimkiewicz, B. (2009). Structural media pluralism and ownership revisited: The case of central and Eastern Europe. Journal of Media Business Studies, 6(3), 43–62. doi:10.1080/ 16522354.2009.11073488

Konieczna, M., & Robinson, S. (2014). Emerging news non-profits: A case study for rebuild-ing community trust? Journalism, 15(8), 968–986. doi:10.1177/1464884913505997

Levy, D., & Picard, R. G. (2011). Is there a better structure for news providers? The potential in charitable and trust ownership. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford, England.

Lucchi, N., Ots, M., & Ohlsson, J. (2017). Innovation policies in Sweden. In H. van Kranenburg (Ed.), Innovation policies in the European news media industry (pp. 191– 203). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.

Matthews, R. (2017). ‘The ideological challenge for the regional press; reappraising the community value of local newspapers’. The Journal of Applied Journalism and Media Studies, Volume 6, Issue 1, Pages 37–56.

Melesko, S. (2000). Investeringar och produktivitet i landsortspress [Investments and produc-tivity in local newspapers] (Research report Nr. 39). Gothenburg, Sweden: Gothenburg University

Melesko, S. (2010). Motives for mergers and aquisitions in the Swedish regional press. Case: The sale of Center party press. In E. O. Hultén, S. Tjernström, & S. Melesko (eds.), Media mergers and the defence of pluralism (pp. 41–74). Gothenburg, Sweden: Nordicom. MRTV. (2015). Medieutveckling 2015. Stockholm, Sweden: Myndigheten för Radio & TV. Noam, E. M. (2009). Media ownership and concentration in America. Oxford, England:

Oxford University Press.

Nordicom. (2017, June 15). Statistics retrieved. Retrieved fromhttp://www.nordicom.gu.se/sv/ statistik-fakta/mediestatistik

Ohlsson, J. (2012). The practice of newspaper ownership: Fifty years of control and influence in the Swedish local press (Doctoral dissertation). University of Gothenburg. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2077/29101

Ohlsson, J. (2013). De svenska tidningsstiftelserna: Partipressens sista bastion? [The Swedish newspaper foundations: The last fort of the party-owned press?]. Journalistica, 1, 10–32. Olsson, K. (1996). Näringsdrivande stiftelser: En rättslig studie över ändamål, förmögenhet och

förvaltning [Commercially active foundations: A legal study of their purposes, assets and governance]. Stockholm: Nerenius & Santérus Förlag AB.

Ots, M. (2012). Competition, collaboration and cooperation: Swedish provincial newspaper markets in transition. Journal of Media Business Studies, 9(2), 43–63. doi:10.1080/ 16522354.2012.11073543

Ots, M. (2013). Sweden: State support to newspapers in transition. In P. Murschetz (Ed.), State Aid for Newspapers (pp. 307–322). Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Germany.

Ots, M., Krumsvik, A. H., Ala-Fossi, M., & Rendahl, P. (2016). The shifting role of Value-Added Tax (VAT) as a media policy tool: A three-country comparison of political justifications. Javnost - The Public, 23(2), 170–187. doi:10.1080/13183222.2016.1162988 Picard, R. G. (2005). Corporate governance: Issues and challenges. In R. G. Picard (ed.),

Corporate governance of media companies, JIBS Research Report Series No. 2005-1 (pp. 1– 10). Jönköping, Sweden: Jönköping International Business School.

Picard, R. G. (2011). Charitable ownership and trusts in news organizations (D. A. L. Levy & R. G. Picard, Eds.) (pp. 17–29).

Picard, R. G. (2014). Twilight or new dawn of journalism? Journalism Studies, 15(5), 500–510. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2014.895530

Picard, R. G., & van Weezel, A. (2008). Capital and control: Consequences of different forms of newspaper ownership. International Journal on Media Management, 10(1), 22–31. doi:10.1080/14241270701820473

Powers, E., & Yaros, R. A. (2012). Supporting online nonprofit news organizations: Do financial contributions influence stakeholder expectations and engagement? Journal of Media Business Studies, 9(3), 41–62. doi:10.1080/16522354.2012.11073551

Schultz, J. (1998). Reviving the fourth estate: Democracy, accountability and the media. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Shaver, D. (2010). Online non-profits provide model for added local news. Newspaper Research Journal, 31(4), 16–28. doi:10.1177/073953291003100403

Thomsen, S., & Rose, C. (2004). Foundation ownership and financial performance. European Journal of Law and Economics, 18, 343–364. doi:10.1007/s10657-004-4277-y

Vizcarrondo, T. (2013). Measuring concentration of ownership 1976–2009. International Journal on Media Management, 15(3), 177–195. doi:10.1080/14241277.2013.782499 Weibull, L., & Anshelm, M. (1991). Signs of change: Swedish media in transition. Nordicom

Review, 2, 37–63.

Wigand, K., Haase-Theobald, C., Heuel, M., & Stolte, S. (Eds.). (2015). Stiftungen in der Praxis: Recht, Steuern, Beratung. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer Gabler [Foundations in practice: law, taxation, consulting].

Zhang, S. I. (2010). Chinese newspaper ownership, corporate strategies, and business models in a globalizing world. International Journal on Media Management, 12(3–4), 205–230. doi:10.1080/14241277.2010.527314