Comprehending Millennial Motivation

During a Crisis

The perceived influence of the employee-leader relationship

Jonas Becker

Fanney Thera Rutten

Leadership and Organization Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organization Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organization for Sustainability (OL646E), 15 credits Spring 2020 Chiara VitranoTitle: Comprehending Millennial Motivation During a Crisis – The perceived influence of the employee-leader relationship

Authors: Jonas Becker & Fanney Thera Rutten

Main field of study: Leadership and Organization

Type of degree: Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with Major in Leadership and Organization

Subject: Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organization for Sustainability (OL646E), 15 credits

Period: Spring 2020

Abstract

This study aims to understand how Millennial employees perceive the relationship with their leader to influence their motivation during a crisis. It will do so within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Apart from Millennials comprising the majority of the future workforce, studies have shown that crises, such as pandemics, are likely to increase, due to factors such as climate change and globalization. To withstand such future crises and enhance intra-organizational sustainability, grasping what motivates Millennial employees is necessary. This study takes on an employee-leader relationship approach to Millennial employee motivation, through the perception of ten non-managerial employees from The Netherlands and Germany. Data that was obtained through semi-structured interviews. To gain an understanding of the relationship between Millennial employees and their leaders, expectations and current perceptions of said relationship were discussed. In order to better understand Millennial employee motivation, general needs and the perceived influence of the employee-leader relationship were documented. General findings supported previous literature on the Millennial cohort in the workplace, mainly highlighting the perceived importance of a personal, reciprocal relationship between the employee and the leader during a crisis. In relation to the aim, the findings of this study show that respondents found the relationship with their leader during a crisis to be motivational if the leader was able to meet basic emotional needs, positioned themselves as a vulnerable human being within the relationship, showed the ability to find a silver lining and articulate that to the employee, and communicated in a way that respondents found adequate.

Keywords: COVID-19, Crisis, Crisis Leadership, Employee motivation, Millennials, Millennial employee, Organizational resilience, Social sustainability

Acknowledgements

This thesis was written amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, which brought about much uncertainty to all of society. We were forced to shift into another gear, but were inspired by the innovative ways in which everyone involved helped us to end our master’s program with a thesis that we take great pride in. First and foremost, we would like to thank our supervisor Chiara Vitrano for her availability and continuous provision of constructive and positive feedback. Furthermore, we are thankful to the respondents for being flexible and making time in their schedules during these demanding times. We would then like to thank Dave de la Fuente for his efforts. Last but not least, we would both like to express gratitude to our parents for providing us the opportunities that allowed us to close this chapter of our life feeling confident about what the future will bring

Stipulative definitions

SARS-CoV-2 - Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2.

COVID-19 - This study refers to COVID-19 as the disease, and pandemic, that was caused by SARS-CoV-2.

Corona - How the COVID-19 pandemic is often referred to by the public and the respondents of this study.

Millennial employees - In accordance with Valenti (2019), this study refers to Millennial employees as people born between 1982 and 2004.

Leader - Gandolfi and Stone (2016) state that multiple people can be perceived as a leader. Accordingly, in this study, a perceived leader can be one or more persons.

Table of contents

Abstract 2Acknowledgements 3

Stipulative definitions 4

1. Introduction 1

1.1. Background 1

1.2. Research problem 3

1.3. Aim and research questions 3

1.4. Previous research 4

1.4.1. Millennials in the workforce 4

1.4.2. Crisis 5

1.4.3. Organizations in Crisis 6

1.4.4. Leadership and employee motivation 6

1.4.5. Contribution to literature and knowledge 7

1.5. Layout 8

2. Theoretical framework 9

2.1. Leadership in Crisis 9

2.1.1. Crisis 9

2.1.2. Leadership and organizational resilience 9

2.1.3. Crisis leadership 10

2.1.4. Leadership as a reciprocal process 10

2.1.5. Millennials and leadership 11

2.2. Motivating Millennial employees 12

2.2.1. Motivation theory 12

2.2.2. Millennial motivation 13

3. Methodology and Methods 15

3.1. Methodology 15

3.1.1. Research strategy 15

3.1.2. Reliability and validity 15

3.1.3. Ethics 16

3.1.4. Limitations 16

3.2. Research methods 16

3.2.1. Operationalization 16

3.2.2. Data collection 16

3.2.3. Data analysis 17

4. Analysis 18

4.1. Object of study 18

4.2. Understanding the Millennial employee-leader relationship during a crisis 19

4.2.1. Employee expectations of leader in crisis 19

4.2.2. Perceived current relationship 23

4.3. Understanding Millennial employee motivation in crisis 27

4.3.1. Motivational needs 27

4.3.2. Perceived influence relationship on motivation 30

5. Discussion 34

5.1. Understanding the Millennial employee-leader relationship 34

5.2. Understanding Millennial motivation during a crisis 35

5.3. Main points of discussion 35

6. Conclusion 37

List of References 39

Appendix i

Appendix I. Theoretical operationalization i

Appendix II. Interview guide ii

Appendix III. Sampling text iii

Appendix IV. Interview schedule iv

Appendix V. Guarantee of anonymity v

Appendix VI. Primary coding sheet vi

1. Introduction

The aim of this paper is to establish an understanding on how Millennial employees of SMEs perceive the relationship with their leader to affect their motivation during a pandemic. Modern day organizations are increasingly considering the impact their operations have on society, often following the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) approach that suggests that attention should be paid to environmental, economic and social impacts (Elkington, 1998;

Flores, Gavronski, Nardi & Haag, 2017

). However, the social aspect of sustainability in the corporate world seems to frequently be overlooked (Ajmal, Khan, Hussain, & Helo, 2017). As Hubbard (2009) states: "In contrast to measuring environmental performance, the social aspect of the Triple Bottom Line is far less understood and many firms struggle to articulate their social impacts and responsibilities" (p.185). Furthermore, scholars have found that modern society will increasingly be subjected to crises (Ross, Crowe and Tyndall, 2015). This will impact organizations, both internally and externally. In order for organizations to build resilience and move towards a more socially sustainable way of operating, an understanding of intra-organizational social dynamics is necessary. The current COVID-19 pandemic provides an opportunity for investigation on how the future workforce, that will consist of Millennials mainly, perceives the employee-leader relationship to be motivational. Through this intra-organizational, relationship based approach, the study will provide unique insights, contributing to the slim amount of literature that addresses organizational dealings, social dynamics and through the perspective of Millennial employees. Grasping the motivation of the future workforce could be an enhancing factor for organization’s social sustainability.1.1. Background

Five months in, the year 2020 has already been defined by the global crisis that was caused by the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. The SARS-CoV-2 virus, that causes the COVID-19 disease, knows its genesis in China where it quickly spread as an epidemic (World Health Organization, 2020). SARS-CoV-2 is a novel form of virus that hitherto had not yet been detected in human bodies. Due to its high levels of contagiousness and the lack of a cure and/or vaccine, it did not take long for COVID-19 to spread across borders (World Health Organization, 2020). That is why, on the 11th of March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) classified the COVID-19 disease as a pandemic, which can be defined as an epidemic that has spread on a larger geographical scale (Hays, 2005). As the virus spreads globally, governments are required to take action and form new policy to contain further proliferation. Although these decisions are mostly made within country borders, repercussions are felt across the globe as they impact modern human life in one way or the other (Scott, 2020). As many countries currently (April 2020) find themselves in a form of lockdown or emergency situation, economic consequences seem inevitable on both personal and organizational levels. As Baldwin and di Mauro (2020) state in their book Economics in Time of COVID-19: “The virus may in fact be as contagious economically as medically” (p. 1).

Linnenluecke, Griffiths, and Winn (2012) state that disasters “will have an increasing impact on organizations, industries and entire economies” (p.17). Ross, Crowe and Tyndall (2015) support this statement by stating that global pandemics will increase in the future. Organizations are big contributors in the spreading of pandemics and climate change through global sales and pollution (Giddings, Hopwood, O’Brien, 2002; Savitz, 2013). In order to survive on the long run and reduce the risk of crises, organizations need to take economic, environmental, and social (also known as Elkington’s (1998) Triple Bottom Line ) dimensions into account and act upon them. The social part of TBL incorporates “(...) skills and education, social, social justice, workplace safety, working conditions, human rights, equal opportunity, and labor rights” (Jamali, 2006, p. 182). This study focuses on the intra-organizational aspects of social sustainability.

Organizations are continuously faced with many different types of challenges on a daily basis that require them to be agile and flexible. However, the occurrence of unexpected, unprecedented events, such as the current COVID-19 pandemic, demands organizational resilience (Alias, Ismail, Alia & Omar, 2019). This, among other things, requires the ability to manage unexpected disruptions and events to minimize unfavorable consequences and maximize the speed of recovery (Alias et al., 2019). In the academic debate on organizational resilience, a discussion on the actual meaning of the term exists (Duchek, 2019). According to the author, there is an increasingly favorable attitude towards the notion that organizational resilience entails more than just returning to a normal state of operating. She states that a growing number of scholars suggests that organizational learning and adaptation should be taken into account, allowing organizations to thrive during and after the crisis. Adding onto economic advantage, this could also have implications on intra-organizational, long-term, social sustainability. To achieve the above, motivated employees are deemed necessary.

A crisis such as the present brings a high amount of uncertainty to many and therefore leadership is necessary in all levels of society. As a nation looks to their country’s leader, politicians are guided by health agencies, organizations- and more specifically their employees need leaders that will maneuver their companies through testing times (Johnson, 2017). Amongst others, leadership practices are considered to be key factors that influence organizational resilience (Barasa, Mbau & Gilson, 2018; Pal, Torstensson & Mattila, 2014). Unexpected events not only have an impact on the organizational level, as they do equally so on the individual level. It is said that strong leader-follower relationships enhance performance and employee motivation (Omilion-Hodges & Sugg, 2019). Subsequently, motivated employees have a positive impact on organizational performance (Alghazo & Al-Anazi, 2016; Leroy, Segers, Van Dierendonck, & Den Hartog, 2018). As needs of employees can shift in difficult times, organizations need to balance the ability to react to those needs, provide supportive responses, and prioritize staff wellbeing while sustaining business. Therefore, leadership is key as leaders should constantly aim to increase employee motivation (Naile & Selesho, 2014). In other words, leading an organization through a pandemic requires more than maintaining economic advantage, as it conjointly relates to its employees and keeping them motivated, as they play a big part in organizational survival (Lindner, 1998).

Although the scope of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak is considerable, pandemics are no new type of crisis. However, our world is changing more rapidly than ever, which provides a new context for the existence and development of this specific crisis (Beck, 1992; Levin Institute, 2019). Furthermore, it is not only the modern pandemic that adds to the novelty of the situation, as the demographic currently dominating the workforce does equally so. As Baby Boomers, whom Jorgensen (2003) describes as those born between 1946 and 1962, start to retire, Millennials are on the rise. Valenti (2019) defines the Millennial cohort as those born between 1982 and 2004 and states that they are expected to make up 75% of the workforce by 2025.This group of young workers brings a new and different set of values, beliefs, needs and attitudes to the workplace and many organizations struggle with managing, retaining and motivating them (Thompson & Gregory, 2012; Calk & Patrick, 2017). Amongst other things, it has been said that Millennials express a stronger need for a good, open, meaningful and reciprocal relationship with their leaders than previous generations (Chou, 2012; Thompson & Gregory, 2012; Omilion-Hodges & Sugg, 2019). Additionally, most enterprises within the European Union are categorized as Small and Medium Sized-Enterprises (SMEs), providing a large majority of the employment to this new group of Millennial employees (Chowdhury, 2011). The combination of an unprecedented pandemic and a new workforce demographic makes for relatively uncharted academic territory. Omilion-Hodges and Sugg (2019) state that even though a considerable amount of literature on Millennials in a work environment exists, “the voice of Millennials is largely absent” (p. 75). Next to a stronger desire of a meaningful relationship with their leader, Millennials also have higher social needs within a work environment than their predecessors (Chou, 2012; Omilion-Hodges, 2019). Though an increasing human-centered approach can be observed in crisis literature, social dynamics are still often overlooked (Powley, 2009). Subsequently, understanding employee perceptions has become all the more crucial. Therefore, this research will focus on how Millennials perceive the relationship with their leaders during a crisis to affect their motivation, as “leadership is a process ascribed by followers” (Omilion-Hodges, 2019,

1.2. Research problem

A pandemic of the scope such as the current one has not been seen in over a hundred years, implying a different context for its development (Hays, 2005; Baldwin & Tomiura, 2020). Overcoming such a crisis requires organizations to be resilient, which relates to both the external and internal environment of the organization (Seville, 2016, Duchek, 2019). Literature states that leadership is a key ingredient to sufficient resilience, and that leaders likewise have to be able to manage internal and external challenges that they are subjected to during a crisis, both on an organizational and an individual level (Epitropaki, et. al., 2016; Jamal, Bakar, 2015). Coping with internal and external challenges influences the aforementioned economic, environmental and societal elements an organization has to take into account in today’s business context.

According to Calk and Patrick (2017) it is crucial to acknowledge generational differences within organizations, as different generations bring “(...) varying beliefs, work ethics, values, and expectations to organizations” (2017, p. 131). Studies prove that Millennial employees have different ways of prioritizing their work needs and, as stated earlier, often express a higher need of a meaningful relationship with their leader. Furthermore, it has been established that the relationship between leaders and their followers can have a positive influence on both organizational performance and employee motivation (Naile & Selesho, 2014). Considering the fact that followers play a crucial role within leadership, it is important to take on a relationship approach. Current literature, however, seems to lack in that regard. Crisis leadership is frequently discussed from a managerial perspective and often overlooks the intra-organizational social dynamics (Powley, 2009; Epitropaki, Kark, Mainemelis, Lord, 2017; Leroy, et. al., 2018). Additionally, literature on Millennials in the workforce often mainly focuses on how to attract, retain and motivate them from an organizational point of view (Thompson & Gregory, 2012).

Employees are a vital aspect of organizational performance and survival. Their wellbeing and motivation are crucial, both in conventional and uncommon circumstances and strengthen an organization’s social capital (Epitropaki, et. al., 2017). Intra-organizational social capital indirectly influences employee motivation, as it increases when strong and decreases when weak (Hador, 2016). Literature on the relationship between Millennials, their leaders and work motivation seems at its infancy, and is rarely (if ever) put into the context of a crisis. Additionally, as Omilion-Hodges and Sugg (2019) argue, the Millennial voice hardly resonates in research on their cohort. Millennials are often negatively stereotyped and misunderstood by other generations, leading to organizational struggles on managing them (Thompson & Gregory, 2012). It is therefore necessary to understand how Millennial employees perceive the relationship with their leaders during a crisis and how they perceive that relationship to relate to their motivation. The current COVID-19 pandemic provides an opportunity for such research. Not only will this study bridge the gap in existing literature, it will enhance the understanding of the future workforce and aid organizations in motivating the employees they seem to struggle with in future (crisis) situations through the leader-employee relationship. As Singh, Rai and Bhandarker (2012) put it: “Fit between Millennials’ expectations and workplace realities will enable the organization to unleash the potential of Millennials, heighten their motivation, tap into their innovative and entrepreneurial capabilities, and prepare organizations to compete and excel globally” (Singh et al., 2012, p. 97).

1.3. Aim and research questions

This study aims to understand how Millennial employees perceive the relationship with their leader during a crisis to affect their motivation as a part of the workforce. As the research will be conducted in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic it is topical and it will make both an academic and practical contribution. Academically, it will add to the slim amount of literature that takes on the perspective of Millennial employees on organizational dealings and social dynamics within the context of unprecedented situations. By studying motivation through the lens of the employee-leader relationship, this research will provide unique insights. The study intends to integrate crisis leadership and

(Millennial) employee motivation theory and place it within the context of an ongoing global crisis (COVID-19). It will do so by focusing on the perceived relationship between leaders and employees. Practically, it will provide a better understanding of the relationship between Millennial employees and their leaders and what motivates these employees. This could have managerial implications for future strategies on leadership behaviors and motivation during a crisis. As stated earlier, future occurrence of crises, disasters and pandemics will increase and have a large impact on organizations worldwide (Linnenluecke et al., 2012; Ross et al., 2015). These organizations need to know how to carry this socially oriented, Millennial workforce through these crises.

To fulfill the aim of understanding how Millennial employees of SMEs perceive the relationship with their leader to affect their motivation during a pandemic, the following research questions have been formulated.

Research question 1: What do SME Millennial employees expect from the relationship with their leader

during a pandemic?

Research question 2: How do SME Millennial employees perceive the relationship with their leaders

during the current pandemic?

Research question 3: What are SME Millennial employees’ general motivational needs during a

pandemic?

Research question 4: How do SME Millennial employees perceive the current relationship with their

leader to affect their motivation during a pandemic?

1.4. Previous research

The following section discusses the evolvement and current state of literature on the main concepts within this research. This study focuses on Millennial employees specifically, and therefore a basic understanding of Millennials in the workforce is provided. Further, previous literature on organizational resilience, crisis leadership and (Millennial) employee motivation is reviewed, as they constitute the main focus areas in this study. Lastly, a gap in current literature is identified, followed by the contribution this paper aims to provide in closing said gap.

1.4.1. Millennials in the workforce

Millennials are often discussed in both academia and public press, and some confusion exists on who they actually are. The chosen categorization in this research is presented by Valenti (2019), who defines Millennials as those who are born between 1982 and 2004. It is important to take some background factors into account as each generation is shaped by unique life experiences and historical events (Thompson & Gregory, 2012; Calk & Patrick, 2017). First of all, Millennials are the first generation to be born into modern technology, which has enabled a better and broader comprehension of technology which has influenced their way of communicating (Thompson & Gregory, 2012). These authors further state that Millennials have often been raised in an environment where they have been subjected to constant feedback and individual attention, which translates into their attitudes and expectations in a work context. Several studies have shown that Millennials value personal goals over organizational goals, making them more individualistic than previous generations (Chou, 2012; Singh et al., 2012). This individualism has brought about an attitude where Millennials expect organizations to convince them to work for them, instead of the other way around, strongly differentiating themselves from older generations (Thompson & Gregory, 2012). Furthermore, growing up during the recession of 2008, Millennials have witnessed the decrease of contract-work, which has shaped their work expectations (Thompson & Gregory, 2012).

In the academic and public debate, Millennials in a work environment are often stereotyped as disloyal, needy, entitled and casual (Thompson & Gregory, 2017). However, there have been scholars that counter this notion by debunking these stereotypes, and argue that they are simply different from previous generations and that organizations should aim at understanding these employees and their

been found to be hard working, having a strong need to achieve, strive and prove themselves (Singh et al., 2012). In an extensive profile on the cohort provided by the authors, they further state that Millennials prioritize personal growth and self-fulfillment and are community minded. Furthermore, they value freedom to take initiative, equity and fairness, feedback on their performance and care less about stability and bureaucracy (Singh et al., 2012; Calk & Patrick, 2017). The former summarize Millennial expectations of a workplace as follows: “(...) Millennials would not like to be associated with a workplace which is bureaucratic, mechanistic, hierarchical, status quoist, de-empowering and non-entrepreneurial” (Singh et al., 2012, p. 102).

1.4.2. Crisis

‘Crisis’ is a complex term that can be examined in different ways, and on several levels (Rosenthal, Boin & Comfort, 2001). It is dependent on the perspective and the purpose of a study how crisis is defined (Frandsen & Johansen, 2016). However, most scholars agree that crisis represents a negative discontinuity, which means that there is major incongruence between the expected and what actually happens within the environment (Selart, Johansen & Nesse, 2013; Frandsen & Johansen, 2016). Additionally, crises can be perceived differently by individuals and organizations. It is crucial for an organization to know what a crisis is in order to indicate when they are experiencing one (Frandsen & Johansen, 2016). For researchers it is equally essential to know the definition of a crisis, to be aware of how many different crisis definitions are available and to form a pre-understanding of what frames a crisis. Therefore, it is important to define crisis and establish a typology for the term that will be used throughout this research.

More than fifty years ago, Hermann (1963) presented one of the first definitions of crisis. Based on his experience in the military, politics, and business, he defined an organizational crisis as something that “(...) threatens the high-priority values of the organization, presents a restricted amount of time in which a response can be made, and is unexpected or unanticipated by the organization” (Hermann, 1963, p.64). Hermann defined three key characteristics of a crisis which are ‘threat’, ‘short response time’, and ‘surprise’. Regardless of its age, these three characteristics compose one of the most frequently used definition in crisis research (Frandsen & Johansen, 2016).

Taking on a more direct approach to crisis are Pauchant and Mitroff (1992), with the following definition: “(...) disruption that physically affects a system as a whole and threatens its basic assumptions, its subjective sense of self, its existential core” (Pauchant and Mitroff, 1992, p. 12). This is similar to Ulmer, Sellnow and Seeger’s (2007) approach, who describe crisis as a “(...) specific, unexpected, and non-routine event or series of events that create high levels of uncertainty and threaten or are perceived to threaten an organization's high-priority goals” (Ulmer, Sellnow & Seeger, 2007, p.7) Both definitions are more profound as they include the physical and psychological aspect of a crisis. They contain the basic assumption that the members of the system uphold are challenged to the point where they realize that the system’s foundation is faulty, or that they need to establish defense mechanisms to uphold the system in the future (Frandsen & Johansen, 2016)

Building upon the psychological aspect of a crisis, James and Wooten (2005) describe crisis as “any emotionally charged situation that, once it becomes public, invites negative stakeholder reaction, and thereby has the potential to threaten the financial wellbeing, reputation, survival of the firm or some portion thereof” (p.142). The word ‘emotionally’ indicates that crises are perceived differently among different stakeholders and thus have different repercussions for people and organizations. They argue that there are two types of crises which are ‘sudden’ and ‘smoldering’ crises. Sudden crises are unexpected events on which the organization has no influence (James & Wooten, 2005). Smoldering crises start as a small internal problem that become public to stakeholders and over time develop into a crisis (James & Wooten, 2005). However, their research focuses on smoldering crises as they frame it as “emotionally charged situation that, once it becomes public, invites negative stakeholder reaction” (p.3), whereas the COVID-19 pandemic seems to be more of a sudden crisis.

Another popular and widespread definition of crisis comes from Pearson and Clair (1998). In their paper Reframing Crisis Management (1998) a crisis is defined as “a low-probability, high-impact event that threatens the viability of the organization and is characterized by ambiguity of cause, effect and means of resolution, as well as by a belief that decision must be made swiftly” (p.60). Pearson and Clair go into more detail than James and Wooten, Ulmer, Sellnow and Seeger, or Pauchant and Mitroff as they recognize that a crisis is ambiguous (Frandsen & Johansen, 2016). Accordingly, Acquier, Gand, and Szpirglas (2008) stress the importance of recognizing the fact that crises often make for situations where clarity lacks. As can be observed, many academic efforts have been made in defining crisis. Even though each definition emphasizes different aspects, consistent recurring elements are unexpectedness and discontinuity that threaten the organizational operations, with a limited amount of response time.

1.4.3. Organizations in Crisis

According to Duchek’s (2019) review on organizational resilience literature, there has been a growing scholarly interest in the field since the beginning of the 21st century. A literature review on the field reveals several trends and patterns. Most scholars agree on the fact that organizational resilience relates to both the external and internal environment of an organization (Duchek, 2019). However, as it is a complex concept, organizational resilience is a term that has proven to be hard to define. Organizational crises are commonly recognized as having three stages, as Promsri (2014) puts it: a pre-crisis stage, a crisis stage and a post-crisis stage. Nonetheless, different views exist on what resilience to these crises actually entail and which purpose it serves. Some state that it is an organization’s capability to ‘bounce back’ from a crisis and return to normalcy, whereas others argue organizations should also be able to adapt and/or thrive during and after a crisis (Cheese, 2016; Duchek, 2019). The latter states that an increasing favorable attitude towards the notion of adaptation and thriving can be observed in literature. Organizations are exposed to crises on a daily basis (Seville, 2016). While flexibility and agility are necessary to deal with daily problems and changes, resilience is an important success factor in dealing with unexpected threats and crises (Ducheck, 2019). In times of crisis, organizations need the ability to develop solutions through rapid idea generation and coordination (Ducheck, 2019). As Seville (2016) states, the “(...) challenge for the 21st century is to create organizations that are future-ready, with an inbuilt capacity not only to weather the storms of change, but to be able to thrive in such environments” (p. 3). Organizations must be able to anticipate pro-actively and manage the risks that come with a crisis and whilst establishing coping mechanisms for crisis that cannot be anticipated (Seville, 2016). When organizations are faced with unexpected events, their resilience is being tested (Duchek, 2019). Resilience is the ability to deal with internal or external distresses and recover from them (Rose, 2004; Carvalho, Cruz-Machado & Tavares; Annarelli & Nonino, 2016). Wildavsky (1988) defines resilience as “(...) capacity to cope with unanticipated danger after they have become manifest, learning to bounce back” (p.77). Therefore, organizational resilience is both dynamic and contextual. Dynamic because resilience changes over time and contextual because every organization has a particular weakness (Seville, 2016).

1.4.4. Leadership and employee motivation

Exponential population growth, technological development and globalization are just a few drivers in the acceleration of the speed rate of change that our world has been subjected to in the second half of the 20th, and the first two decades of the 21st century (Cheese, 2016). This fast pace of change has had its implications on the way organizations are structured, operate and the risks they face (Beck, 1992). Subsequently subjected to this fast pace of change are leadership and employee motivation. Leadership has gone through different phases. From ‘command and control’ in the 1980s, through ‘empower and track’ in the early 2000s to the current bottom-up approach of ‘connect and nurture’ (Gandolfi & Stone, 2016). Simultaneously, the view on employee motivation has shifted from seeing employees as organizational input with a monetary reward to the recognition of the link between employee attitudes, needs, motivation and performance (Lindner, 1998). Additionally, Nohria, Groysberg and Lee (2008) state that traditional motivation literature takes on too much of a hierarchical stance, and argue for a shift towards a more horizontal model of addressing all employee needs without trade-offs.

Although leadership and employee motivation are no small fields of research and undeniably stand alone as concepts, there are similarities that can be taken into consideration. Both concepts stem from long lines of research that have evolved throughout the past century. Additionally, both are embedded in psychology and behavioral science (although increasingly researched within different disciplines). Leadership theory is based upon the notion that one's behavior influences or motivates others to achieve (organizational) goals (Fiaz & Saqib, 2017). According to Nohria et. al. (2008) “(...) people are guided by four basic emotional needs, or drivers, that are the product of our common evolutionary heritage” (p.1), that can be met by organizational levers of motivation. Both concepts have increasingly captured the attention of scholars. Leadership has gained much attention in both practice and academia and many different leadership styles have been identified, making the concept hard to define (Northouse, 2016). Similarly, employee motivation is a complex construct and, though recognized as essential, is often hard to understand and define (Lindner 1998; Alghazo & Al-Anazi, 2016).

However, a more human, or employee-centered shift is taking place in both leadership and employee motivation literature. Achim, Dragolea and Bălan (2013) state that “(...) motivation represents the synergistic effect of an amount of stimuli on the behavior of employees in performing their job duties” (p. 686). According to the authors, leaders are responsible for striving towards optimal economic performance of the organization, whilst taking the capacity, opportunities and needs of employees into account. This is no different during a time of crisis. As crises have an impact externally and internally, leaders maintain a responsibility of responding to both sides (James & Wooten, 2005). Addressing employee needs and motivating them should remain equally important as returning to a state of economical normalcy or improvement on an organizational level. Even more so, it is often argued in literature that motivated employees lead to better organizational performance (Lindner, 1998; Alghazo & Al-Anazi, 2016; Achim et. al, 2013). Accordingly, Johnson (2017) states that “(...) the execution of effective crisis leadership requires that leaders have the appropriate resources to lean upon and skilled colleagues to help them” (p.4), stressing the importance the leader-employee relationship in times of uncertainty and stress.

Research suggests transformational and charismatic leadership as appropriate types of leadership during periods of high uncertainty (DuBrin, 2013; Teo, Lee & Lim, 2017). Northouse (2016) defines transformational leadership as “(...) process whereby a person engages with others and creates a connection that raises the level of motivation and morality in both the leader and follower” (p. 264). Before and during the crisis, transformational leadership establishes a trust within the organization. If followers and stakeholders trust the leader they will be more likely to show support during the crisis (DuBrin, 2013).

Charismatic leaders communicate determination, promote a mission and a vision while expecting high performance on work processes, and forecasts organizational performance (Northouse, 2016; Teo et. al., 2017). They constantly self-monitor their own actions, motivate to gain social power, and attain “self-actualization” (Northouse, 2016, p. 64).

1.4.5. Contribution to literature and knowledge

Frandsen and Johansen (2016) point out that the evolvement of media has led to what they call a ‘crisis society’, where crises can attain a certain iconic status. This brings to mind Beck’s (1992) concept of a risk society, where events such as industrialization, technological development and climate change are continuously creating new, unprecedented risks and crises that have an effect on a larger geographical scale than ever before. As pointed out earlier, this not only affects individuals, but organizations as well. The COVID-19 breakout is a representative illustration of such an international effect, as many (post-)modern organizations have spread their value chain globally. This makes it an interesting case for further investigation. In this study, a pandemic is presented as the crisis, which has rarely been done in previous literature as not many have occurred on such a large scale in this postmodern society. Human-centered crisis leadership and employee motivation are fields of research that are increasingly gaining the interest of scholars, which adds to the relevance of this study. As this approach arises, the importance of perception becomes paramount. Johnson (2017) points out the value of a leader’s

perception of a crisis. This study delves takes on another angle: the employee’s perception of the leader during a crisis. An elaborate literature review has further revealed a lack of knowledge on employee motivation during a crisis. Even less literature considers Millennial employee motivation during a crisis. The amount of literature on Millennial employee motivation is slim, often unrepresentative of the cohort’s voice and seldomly put in the context of a crisis.

Furthermore, Duchek (2019) suggests that future research should focus on ongoing practices during a crisis, and this paper aims to do precisely that. It addresses Millennial employee motivation through the lens of the perceived employee-leader relationship during an ongoing crisis. This will bridge the gap in current literature as it ties the concepts of crisis leadership and Millennial employee motivation together. Additionally, the unprecedented character of the COVID-19 pandemic provides a novel context, which enhances both practical and academic relevance.

1.5. Layout

This section presents an overview of the chapters within this study. Chapter 2 consists of the theoretical concepts that are being used. First, leadership within a crisis is discussed, providing a working definition of crisis, organizational resilience, crisis leadership, leadership as a reciprocal process, and a discussion on Millennials and leadership. Lastly, the theoretical framework includes a section on motivating Millennial employees which includes general, and Millennial specific motivation theory. For an operationalization of the theoretical concepts, please see appendix 1.

Chapter 3 outlines the design and choice of method of this research. The methodology section explains which strategy was used and further discusses ethics and the study’s limitations. The method section discusses the theoretical operationalization, data-collection and data-analysis. Chapter 4 first describes characteristics of the respondents and their organizations. It is then divided into paragraphs that align with the sub-questions that can be found in section 1.3. Each paragraph first descriptively presents the results of the study, based on the themes that arose during the interviews. These will then be analyzed in relation to the main concepts of crisis leadership and Millennial employee motivation. In Chapter 5 the main findings of the research are summarized, followed by main points of discussion. Lastly, Chapter 6 presents the conclusions of the study, with suggestions for future research.

2. Theoretical framework

This section provides an overview of the theory and concepts that are used in this research, and is structured as follows. The first section (2.1.) places leadership in the context of a crisis. As the COVID-19 pandemic is referred to as a crisis in this study, it is important to know what is meant by a crisis. Therefore, the section begins with a working definition of crisis. Then, the concepts crisis and organizational resilience will be linked to leadership. Next will be a discussion on crisis leadership as reciprocal process. Lastly, the section links Millennials to leadership.

Section 2.2. comprises theory on the second main concept of this study: motivation. First, general motivation theory will be discussed, followed by a presentation on relevant Millennial motivation theory.

2.1. Leadership in Crisis

2.1.1. Crisis

Previous literature on crisis points out the various interpretations scholars have of the subject. Although carefully considering these interpretations, to lay a convivial foundation of the complex concept, this paper makes use of the most recent definition of crisis, as presented by Coombs (2014). In his book Ongoing Crisis Communication (2014), Coombs defines crisis as “(...) perception of an unpredictable event that threatens important expectancies of stakeholders related to health, safety, environmental, and economic issues, and can seriously impact an organization's performance and generate negative outcomes” (p. 3). Coombs introduces the concept of perception, which emphasizes that crisis events are perceived differently by stakeholders. This interpretation of crisis is supported by Alpaslan and Mitroff (2011) that state that “all crises are complex systems of multiple, interacting and interdependent crises, all of which can and will be viewed differently by different stakeholders” (p. 38). Both definitions highlight the importance of stakeholders within crisis situations. Alpaslan and Mitroff (2011) further describe crisis as messy. They reason that affected stakeholders perceive a crisis differently and have contrary opinions and understandings of the crisis (Alpaslan & Mitroff, 2011). Second, a crisis is a series of interdependent “issues, problems, and assumptions” (Alpaslan & Mitroff, 2011, p. 37) that cannot be dealt with separately. Third, crisis are no secluded events and one crisis most likely triggers a chain reaction of crises (Alpaslan & Mitroff, 2011).

2.1.2. Leadership and organizational resilience

As previously discussed, to overcome a crisis, organizations are required to be resilient. For organizations to be resilient, the organizational environment must be properly understood (Seville, 2016; Duchek, 2019). To successfully anticipate crisis events, research shows that vigorous planning and strategic leadership with a clear decision making process, that supports organizational development, is needed (Promsri, 2014). During times of severe adversity, decisions must be made promptly and failures could have dramatic consequences (Ducheck, 2019). This emphasizes that leadership plays a crucial role within organizational crisis and resilience. Seville (2016) names leadership and staff engagement as main ingredients in creating a resilient organization. Seville (2016) even states that “leadership is the most critical requirement for a resilient organization” (p. 33) and that human resources are vital elements for organizational survival (Seville, 2016; Ducheck, 2019). Thus, the organization’s performance and structure is greatly influenced by its members and their behavior (Tolbert & Hall, 2009). Therefore, when analyzing an organizational crisis, the social, and human aspect should not be overlooked.

In their operational definition of leadership, Gandolfi and Stone (2016) state that “(...) there must be one or more leaders, (ii) leadership must have followers, (iii) it must be action oriented with a legitimate (iv) course of action, and there must be (v) goals and objective” (p. 216). This indicates that there can be more than one leaders. Winston and Patterson (2006) approach leadership in a more integrative and

practical manner and define it as “(...) a leader is one or more people who selects, equips, trains, and influences one or more follower(s) who have diverse gifts, abilities, and skills and focuses the follower(s) to the organization’s mission and objectives causing the follower(s) to willingly and enthusiastically expend spiritual, emotional, and physical energy in a concerted coordinated effort to achieve the organizational mission and objectives” (p.7). Due to its practicality, this definition is deemed applicable to the current research.

2.1.3. Crisis leadership

Having established the importance of a leader’s role during a crisis, it is crucial to clarify what is meant by a crisis leader. Pearson and Claire (1998) consider a crisis leader to be someone that faces a challenge that they have never faced before and cannot predict the cause and effect of the challenge. This means they do not know how it will affect their organization or how to fix it, whilst simultaneously having to quickly decide on the ongoing progress. However, leaders rarely face a combination of all these challenges as organizations try to protect them from being exposed to all of them (Johnson, 2017). Therefore, Johnson argues that these attributes of a crisis leader, as provided by Pearson and Claire (1998), lack attention for the emotional impact and external inquisition, as leaders, too, are humans that are affected by the emotional stress that a crisis inflicts upon them (Johnson, 2017).

DuBrin (2013) describes a crisis leader as “a person who leads group members through a sudden and largely unanticipated, negative and emotionally-draining circumstances” (p. xi). This is considered a useful definition as it points out the challenges of leadership during a crisis (Johnson, 2017). However, although the definition addresses what a crisis leader does, it misses an elaboration on how they need to do it. Providing more insight on the latter, James and Wooten (2005) state that “the best crisis leaders are those who build a foundation of trust not only within their organization, but also throughout the organization’s system” (p. 142).

This study’s working definition of crisis leadership is provided by Johnson (2017), who defines the concept as: “(...) the ability of leaders not to show different leadership competencies but rather to display the same competencies under the extreme pressure that characterize a crisis - namely uncertainty, high levels of emotion, the need for swift decision making, and at times, intolerable external scrutiny. It is this that will define success” (p. 15). As Johnson (2017) states, it is impossible for leaders to demonstrate all leadership competencies under all circumstances. Furthermore, it decreases the operational character of the definition as it adds more practicality (Gandolfi & Stone 2016).

Similarly taking on a more practical approach, Boin, Kuipers and Overdijk (2013) have created an extensive framework to assess crisis leadership, which is based on four main tasks. First, sensemaking is necessary to process information from the surroundings to create a dynamic picture of the crisis. According to Frandsen and Johansen (2016) crises are social constructions, and they can be perceived differently by all stakeholders. In essence, the authors state the following: “(...) when a crisis breaks out, it is important to closely follow how the crisis is interpreted by different external and internal stakeholders and how their interpretations develop - or not develop - over time” (p. 49) Second, leaders must make critical decisions and effectively coordinate among parties and steer an organization's strategy. Third, meaning making is crucial to provide a situational interpretation and promote authentic hope and confidence to stakeholders. Fourth, rendering accountability will not only restore legal and moral requirements but also re-establish trust and facilitates learning from the crisis (Boin, Kuipers & Overdijk, 2017).

2.1.4. Leadership as a reciprocal process

As has previously been established, crisis leaders are expected to handle both the internal and external stakeholders of an organization. However, it is important to acknowledge the fact that employees embody a different type of stakeholder group than external stakeholders. Employees inherently have a relationship with the both the organization they work for and their leaders (Frandsen & Johansen, 2016). This relationship is based on a sense of belonging and commitment to their job and it implies that

employees have stakes (such as job security, salary and motivation) that influence their perception of an organization both in and out of crisis (Frandsen & Johansen, 2016). Fostering this sense of belonging can enhance an employee’s motivation (Nohria et al., 2008). Additionally, the way an organization and/or a leader communicates with their employees during a crisis affects those stakes (Omilion-Hodges & Sugg, 2019). According to the authors, trust and transparency will enhance a feeling of safety and could lead to higher motivation. In accordance with Frandsen and Johansen’s (2016) psychological approach, Ducheck (2019) argues that collective sensemaking plays a big role in cognitive resilience, calling on a leader’s “capability to improvise and solve problems creatively” (p. 14). Further, Powley (2009) argues that in order to endure a crisis, interpersonal connections within organizations are crucial, as organizational resilience stems from positive intra-organizational relationships. This involves introducing social mechanisms such as increasing awareness of peers, rising relational structures, and teamwork into existing interpersonal networks (Powley, 2009; Teo et al., 2017).

The fact that actions and interactions between leaders and followers are highly dependent on environmental and contextual elements, suggests that leadership should be seen as a reciprocal process (Fairhurst & Uhl-Bien, 2012). Fairhurst and Uhl-Bien (2012) view “leadership as a relational process co-created by leaders and followers in context” (p.1044). Leadership is located where actors “engage, interact, and negotiate” with each other to understand the organization and produce valuable outcomes (Barge & Fairhurst, 2008, p.1044). Thus, leadership is a highly “contextualized” and “interactive” process (Fairhurst & Uhl-Bien, 2012). This indicates that organizational resilience can be (partially) reached through relational processes (Teo et al., 2017). To conclude, not only does the leader’s perception of a crisis contribute to the way the situation is handled, but employees’ perceptions of a leader’s behavior and their relationship with that leader during an organizational crisis matter just as much as they (and their motivation) play a key part in the performance of the organization and its survival and/or adaptation. Therefore, it is important to shed some light on these perceptions.

2.1.5. Millennials and leadership

As Alpaslan and Mitroff (2011) state, crises are complicated, often unprecedented and perceived differently by all stakeholders. Therefore, when an organization is subjected to a crisis, it is bound to undergo organizational change, at least to a certain extent. As discussed above, this change requires organizations and leaders to be resilient and to adapt to their new circumstances. Leaders are expected to handle the situation both externally and internally and should continuously aim to keep their employees motivated, for both the sake of mere organizational survival and potential thriving (Seville, 2016; Johnson, 2017).

Previous literature on Millennials in the workforce has revealed that many negative stereotypes surround the cohort (Thompson & Gregory, 2012). However, it is increasingly being argued that if organizations set aside their stereotypical views on Millennials, they will have greater success in attracting, engaging, motivating and retaining the generation that will take over the future workforce and is said to be the most productive one ever (Burkus, 2010; Thompson & Gregory, 2012). According to these authors, leaders need to adapt their leadership style to retain and keep the Millennial talent motivated, “one that promotes relationships and meets individual needs” (Burkus, 2010; Thompson & Gregory, 2012, p. 243). Omilion-Hodges and Sugg (2019) conceptualized five leader archetypes targeted at Millennial employees which are leader as mentor, teacher, manager, friend, and gatekeeper. The leader as mentor communicates individualized and personally to create a reciprocal relationship that accommodates the employee and the organization (Omilion-Hodges & Sugg, 2019). A leader as teacher is “an instructor who disperses knowledge, provides motivators, and actively participates in the training of the employees” (Omilion-Hodges & Sugg, 2019, p. 89). The leader as manager archetype separates the leader from the follower by power structure, status, and role division (Omilion-Hodges & Sugg, 2019). A leader as a friend is described by Millennials as a person that they have built a friendship with. Though, if necessary leaders must show authority (Omilion-Hodges & Sugg, 2019). Lastly, the leader as a gatekeeper implies a leader’s access to information and their ability to determine to which extent the sharing of this information would be in favor of the followers. Further, learning from and being inspired by a leader who leads by example is found most motivating by Millennial employees

(Omilion-Hodges & Sugg, 2019). Leaders who lead by example were characterized as hard working, excellent at what they do, passionate, transparent and matched their statements with their actions (Omilion-Hodges & Sugg, 2019). Millennials further value relationships among each other and their leaders more than other generations (Burkus, 2010; Thompson & Gregory, 2012; Omilion-Hodges, Sugg, 2019).

2.2. Motivating Millennial employees

2.2.1. Motivation theory

Building upon Johnson’s (2017) notion of crisis leadership, effective leaders ought to display the same competencies under the extreme pressure that is felt during an ongoing crisis. As he states, high levels of emotion are an important characteristic of a crisis. Amongst other things, this speaks to the emotional needs of employees, and how they change in different situations. Lindner (1998) stresses that motivated employees are needed in rapidly changing work environments, and that leaders should understand what it is that motivates employees within the context of the roles they perform in order to be effective. Furthermore, Johnson’s notion corresponds to Winston and Patterson’s (2006) statement that a leader should enable a follower to “(...) willingly and enthusiastically expend spiritual, emotional and physical energy” (p.7), in order to achieve an organization’s mission and goals.

Generally, motivation theory is based on the notion that human needs, or drives, have to be satisfied (Maslow, 1943; Nohria et al., 2008; Achim et al., 2013). Ramlall (2004) defines needs as physiological or psychological deficiencies that arouse behavior. If these needs are being met, they will positively affect someone’s behavior in striving towards a certain goal. However, it is important to take into account that needs can change over time, vary amongst people and are influenced by many factors. Next to the factor of crisis, another important element to consider is generation. The current workforce contains more generations than ever before, which has its implications on workplace dynamics (Calk & Patrick, 2017). As Baby Boomers are starting to retire and Millennials are ascending the corporate ladder, this group is becoming the majority of the workforce. As with every generation, Millennials have their own expectations and views on work (Calk & Patrick, 2017; Omilion-Hodgins & Sugg, 2019). Their needs, and the way they prioritize those needs can therefore be different from their predecessors.

In their article on employee motivation, Nohria et al. (2008) argue that traditional thinkers base their understanding of motivation and human behavior exclusively on direct observation and therewith fail to grasp important nuances. They exemplify it as “trying to infer how a car works by examining its movements without being able to take apart the engine” (p.1). Thus, they propose a framework that is based on cross-disciplinary research. Their findings suggest that humans are guided by four basic emotional needs (or drives), as displayed in figure 1. An important characteristic of this model is its horizontal nature. Nohria et al. (2008) stress the fact that in an optimal situation, all four needs should be met equally, and that organizations must be wary of addressing them as if they were interchangeable. This represents a more holistic and sustainable approach to employee motivation, which is why it will be used for the foundational understanding of employee motivation in this research.

Figure 1 Employee Motivation (Nohria et al. 2008)

The four drives that the Nohria et al. (2008) discuss, displayed in figure 1, are the drive to acquire (obtaining scarce goods, both tangible and intangible), the drive to bond (forming connections with groups and individuals), the drive to comprehend (satisfying curiosity and mastering the world around you) and the drive to defend (promoting justice and protecting against external threats). Even though they emphasize that all drives should be met as much as possible, they also state that each driver can be met individually through distinct organizational motivational levers. The drive to acquire can best be met through a reward system, the need to bond requires a strong organizational culture, the drive to comprehend can be satisfied through job design and the human need to defend should be met by proper performance-management and resource-allocation processes. In their framework, these levers come accompanied by suggested actions (see figure 1.) that can be carried out by an organization.

Due to a lack of existing frameworks on motivational needs during a crisis, the abovementioned framework will be applied within this research. Even though it does not specify circumstantial aspects, it is based on the thorough research and literature review conducted by Nohria et al. (2008) on employee motivation and it is therefore deemed adequate to serve as a foundational understanding of work motivation in this study.

2.2.2. Millennial motivation

It has been established that employee motivation plays a big role in the relationship between a leader and their followers, and that proper motivation of employees enhances organizational performance (Naile & Selesho, 2014). These authors even argue that the “quality of a manager’s relationship with an employee is the most powerful element of employee motivation” (p. 187). Achim et al. (2013) state that motivating is an art form and that “not everyone can motivate, but anyone can be motivated in various forms and ways” (p.685). Thompson and Gregory (2012) likewise claim that “relationships with managers may be key to successfully leveraging, motivating and retaining Millennials” (p. 239). As stated earlier, Millennial employees prioritize their needs differently compared to other generations. Apart from wanting a meaningful relationship with their leaders, they want to feel coached and mentored by their leader and often prioritize having a more positive and less formal work environment over high salary (Calk & Patrick, 2017). They have further been found to be more altruistic, and more

positive towards teamwork (Chou, 2012; Calk & Patrick, 2017). Important distinctions between Millennial employees and older generations are the need of constant feedback, open two-way communication and the need for meaningful, personally fulfilling and more socially conscious work (Chou, 2012; Calk & Patrick, 2017; Omilion-Hodges & Sugg, 2019). Furthermore, they tend to strive for a different type of work-life balance than older generations. They seem to be more interested in what they do, not when they do it, where they do it or what they wear whilst doing it (Calk & Patrick, 2017). A leader’s communicative behavior plays a significant part in motivating Millennial employees (Omilion-Hodges & Sugg, 2019). According to Cheese (2006), when confronted with a crisis, leaders should “(...) engender calm and be able to communicate vision and response to unfolding events as well as to connect and listen” (p. 328). He stresses the importance of stability and reassurance for all of those involved. Many of the needs of Millennial employees can be placed in a category within the framework proposed by Nohria et al. (2008) and could therefore theoretically be met by an organizational lever of motivation. It is however important to note that it is hard to generalize the needs of Millennials in the workforce, as Calk and Patrick (2017) state that they are an eclectic group. Another consideration to take into account is that these needs might change when employees find themselves in a crisis. Literature on Millennial employee needs during organizational change or crisis is, however, very slim (if existent at all). In part, this research will contribute to bridging that gap.

To conclude, it can be said that meeting the emotional needs of employees is a big part of a leader’s responsibilities. As Kotter (2008) puts it, appealing to basic human needs, values and emotions will enhance motivation. As is evident, both (crisis) leadership and employee motivation are highly psychologically embedded. Needs and circumstances are constantly changing and therefore a leader needs to be able to adapt to the situation, both practically and emotionally, in order to motivate employees in an ongoing crisis. This highlights the importance of capturing employee perceptions during a crisis, such as a pandemic, and how these feelings relate to their motivation. Providing (future) leaders insights on how their role within the relationship is perceived by the employee will help them understand which needs become of heightened importance during a crisis, and how they could potentially be addressed. Factors that characterize modern society such as globalization, climate change and mass communication are likely to cause an increase in crises (and their escalation) that organizations are be subjected to (Boin & Lagadec, 2000). Therefore, anticipating and acknowledging the changing needs within the employee-leader relationship could be useful in future organizational crisis strategy.

3. Methodology and Methods

3.1. Methodology

3.1.1. Research strategy

As this study aims to gain a deeper understanding of how Millennial employees’ perceive the influence of the relationship with their leader on their work motivation, a qualitative approach has been used (Bryman, 2012; Silverman, 2010). Qualitative research is concerned with understanding human behavior from the interviewees’ perspective (Silverman, 2010). The COVID-19 pandemic put the respondents in a highly dynamic reality that was constantly subjected to change, which made a qualitative approach the appropriate one.

As the context and circumstances of this research were unprecedented, there existed a lack of similar literature. Therefore, the research has mainly been of an inductive nature (Bryman, 2012). Even though literature exists on motivational needs of Millennials, the lack of literature that puts those needs into the context of a crisis left no preconceived ideas on those needs. These needs surfaced during the interviews and provided themes that aided the answering of the research questions. As is typical for inductive research, the process, theory and analysis have continuously been reflected upon, and was thus iterative. In order to fulfill the aim of understanding how SME Millennial employees perceive the relationship with their leader to affect to their motivation, first-hand data was used. To obtain the necessary data, semi-structured interviews with employees of two Small and Medium Sized-Enterprises (SME) were held. Using two organization’s was a practical consideration, as it was more feasible to conduct ten interviews in two SMEs than in just one.

3.1.2. Reliability and validity

The reliability of a study considers the way the area of focus is measured (6. & Bellamy, 2012). As this study was inductive, and had little clear indicators provided by theory, a consistent way of measurement was of high importance. In a qualitative research such as the current, reliability strongly relies on the abilities of the researchers. To guarantee consistency, certain steps were undertaken. First, all interviews were conducted together by both researchers, in the same room. If during an interview anything was overlooked or seemed divergent, the researchers could keep each other in check and make sure the obtaining of the data was done consistently. Second, all coding was done by both researchers together with a constant reflection on the process (see appendix VI. and VII.). If any uncertainty regarding the coding arose, the measurement was assessed and improved or changed if necessary. Third, the researchers have been in constant communication throughout the research (both physically and digitally), making sure the focus remained clear on both ends. Furthermore, as the COVID-19 pandemic was an ongoing, ever changing and dynamic event, all ten interviews were conducted over the span of a week, in order to make sure that all data was obtained during the same phase of the crisis (see appendix IV.).

Research validity poses the question if a used measure in fact measures what one wants to find out, and how statements based on data approximate to truth (Bryman, 2012; 6. & Bellamy, 2012). This research does not aim to test a hypothesis and accordingly considers an interpretivist epistemology. Furthermore, social phenomena are regarded as accomplished by social actors and their interactions that are in a constant state of change. In other words, a constructionist ontology is considered (Bryman, 2012). To be able to assure validity to a certain extent, the appropriateness of the methodology, research questions and method have been carefully considered and assessed throughout the process. It was believed that the qualitative approach fits the aim of this study: to understand perceptions. The semi-structured character of the interviews allowed the research to be inductive. Furthermore, the sample of this study fits the demographic of the group that this study aims to investigate and understand.

3.1.3. Ethics

The respondents in this research were asked about the relationship with their leader in their current work environment, which could be seen as a sensitive topic. Therefore, confidentiality, anonymity and data discretion was guaranteed to the respondents. At the beginning of each interview, respondents were informed about this and were asked to agree verbally. All names of the interviewees, colleagues that where mentioned and the company have been made anonymous within the transcripts.

3.1.4. Limitations

As the SARS-CoV-2 still spreads, the COVID-19 crisis is a historic event that we were all part of. Belonging to the same demographic as the respondent group, the researchers were well aware of potential biases, as the breakout has affected all of our lives. However, it was precisely this fact that sparked the interest in the topic of this research and urged the desire to make a useful contribution. Due to the time constraints of two months, only ten employees from two organizations in total could be interviewed. As COVID-19 has called for many travel restrictions, all interviews were held digitally. This might have an effect on the course of the interview. The fact that the situation developed and changed daily, required people and organizations to adjust frequently. Thus, the point of time when the data was collected played an important role. Last but not least, it was important to take into consideration that the crisis was still ongoing and that it had an impact on many people’s lives in many different aspects, both personally and professionally. Careful consideration and discretion were therefore needed when conducting the interviews.

In this research, the respondents decide who they refer to as a leader. The fact that this study does not specify who this leader is, can be seen as both a strength and a limitation. A strength because it enables respondents to answer intuitively, allowing different, and more personal perceptions of whom they consider to be a leader within their workplace into the data. A limitation because the distance between an appointed leader and an employee might be different, possibly impacting the respondents’ perceptions of their relationship. One of the reasons of this study’s relevance is, as mentioned, that crises are likely to increase in the future. However, findings of this research are not inherently applicable to other crises as the scope and nature might differ from the current pandemic.

3.2. Research methods

3.2.1. Operationalization

The main theoretical concepts in this study were crisis, crisis leadership, the employee-leader relationship and (Millennial) employee motivation. Drawing upon the aforementioned theory (see Chapter 2.), concepts and frameworks were broken down into indicators that aided the analysis of the obtained data (see appendix I.). These predefined indicators were synthesized with, and linked to categories that surfaced during the interviews with the respondents.

3.2.2. Data collection

Between 06-05-2020 and 12-05-2020, data was obtained through semi-structured interviews with ten Millennial, non-managerial employees that were born between 1982 and 2004 (Valenti, 2019). This age group will make up a big part of the future labor market, which made the participants appropriate respondents. An interview guide (see appendix II.) was made to aid the researchers in finding out what they were interested in. However, the open format of semi-structured interviews also allowed respondents to add on concepts or themes through intuitive responses.

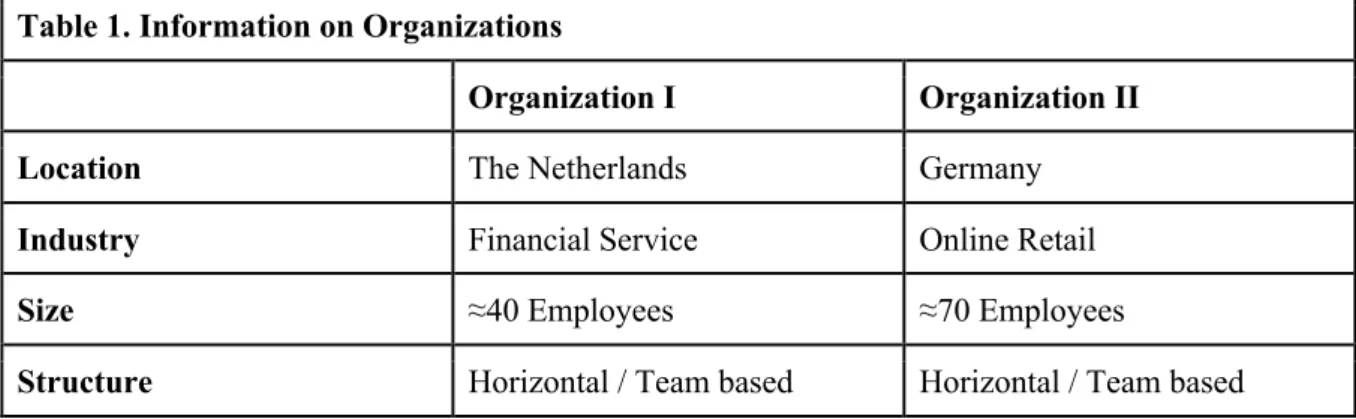

The interviews were held with employees of SMEs in The Netherlands and Germany. The European Commission (2003) defines an SME as having less than 250 employees. The SMEs were to be of similar size in countries with a similar welfare system and governmental response to the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. This has further enhanced the validity of the study (6& Bellamy, 2012). Additional criteria