Systemic Changes for a Sustainable

Fashion Supply Chain

Exploring the Supplier Perspective

Saarinka Kiilunen

Elena Ferrara

Main field of study – Leadership and Organisation

Degree of Master of Arts (60credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organisation Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability (OL646E) 15 credits

Spring 2020

Systemic Changes for a Sustainable Fashion Supply Chain Exploring the Supplier Perspective

Saarinka Kiilunen and Elena Ferrara

Main field of study – Leadership and Organisation

Degree of Master of Arts (60credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organisation Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability (OL646E) 15 credits

Spring 2020

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to everyone who supported us in writing this thesis. Firstly, we would like to say thank you to our supervisor Elnaz Sarkheyli. Thank you for sharing your knowledge, providing us with helpful feedback and encouragement throughout the research process. Secondly, we are very grateful to the interviewees who shared their expertise and experiences with us.

Your contribution to this research has been invaluable. Saarinka Kiilunen and Elena Ferrara

Abstract

The covid-19 pandemic has caused detrimental disruptions within the fashion industry. The effects have rippled through fashion supply chains, yet the majority of the impact has been felt by vulnerable suppliers and workers at the bottom of the pile, highlighting critical systemic issues that have existed in the fashion industry for decades. Business relationships and buying practises in the fashion industry are heavily in favour of brands and wholesalers, leaving suppliers struggling to survive with little financial security in a highly competitive business environment.

The purpose of this study, after reviewing previous research about key characteristics of fashion supply chains and sustainable supply chain management concepts, is to first understand the current supply chain and the existing practises and issues within it, to then enable the investigation of the long-term systemic changes required which could contribute to the reform of fashion supply chain practises going forward. This research focuses on the under-represented perspective of suppliers, and the social issues existing within fashion supply chains.

Qualitative methods are used for data collection and analysis, interviews were conducted with fashion professionals in the supply chain and relevant documents detailing the impacts of the virus and

sustainable supply chain practises were also analysed. In this study, it is found that the power imbalance in fashion supply chains is the root cause of the majority of issues experienced by suppliers, such as biased buying practises, unfair payment terms, and prejudiced approaches to communication, which ultimately leads to the exploitation of workers. A partnership approach is required for buyer supplier relationships, through improving collaboration and communication efforts. Transparency practice needs to be developed to encompass social issues with SC, with an increased focus on brand accountability. Mass education of sustainability issues with the support of enhanced governmental legislation are deducted as key facilitators of sustainable development of the fashion industry going forward. Further research is required to understand the supplier side of the FSC more extensively and further study should also be undertaken to develop existing SSC practises to be more applicable to supplier issues upstream in the FSC.

Key words: Fashion supply chain; Power imbalance; Sustainable supply chain; Sustainable Fashion Supply Chains; Sustainable Supply Chain Management; Systemic issues

Abbreviations:

Comparative Keyword Analysis (CKA) Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Fashion Supply chain (FSC)

Knowledge Sharing (KS)

Non-Governmental Organization (NGO)

Organizational Learning towards Responsible Management (OLRM) Power Imbalance (PI)

Power Dynamics (PD) Resilient Supply chain (RSC) Supply Chain (SC)

Sustainable Development (SD) Supply Chain Management (SCM) Supply Chain Sustainability (SCS) Sustainable Supply Chain (SSC)

Sustainable Supply Chain Management (SSCM Sustainable Fashion Supply Chains (SFSC) Systemic Issues (SI)

Table of Contents

1.Introduction ... 1

1.1 Problem Statement ... 1

1.2 Purpose ... 2

1.3 Research Questions ... 2

1.4 Previous Research ... 2

1.5 Thesis structure ... 3

2. Literature Review ... 5

2.1 The Development of the Supply Chain ... 5

2.2 The Fashion Supply Chain ... 5

2.2.1 Key Elements of Competitive Fashion Supply Chains ... 6

2.2.2 Sustainability in Fashion Supply Chains ... 7

2.3 Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Fashion industry ... 8

2.3.1 Drivers for Sustainable Supply Chain Management ... 9

2.3.2 Sustainability Challenges in Sustainable Supply Chain Management ... 10

2.4 Sustainability Versus Resilience in Supply Chains ... 11

3. Methodology and Methods ... 13

3.1 Research Design ... 13

3.2 Data Collection Methods ... 13

3.2.1 Secondary data ... 13

3.2.2 Primary data ... 14

3.3 Data Analysis Methods ... 15

3.3.1 Interview Analysis ... 15

3.3.2 Document Analysis ... 15

3.4 Reliability and Validity ... 16

3.5 Ethical Considerations ... 16

3.6 Limitations ... 16

3.7 Presentation of Object of Study ... 17

4. Analysis ... 20

4.2 Systemic Issues in the Fashion Supply Chain ... 20

4.2.1 General Systemic Issues ... 20

4.2.2 Power Imbalance ... 21

4.2.3 Supplier Perspective ... 23

4.2.4 Brand Attitude and Buying Practises ... 24

4.3 Required changes in the Fashion Supply Chain ... 26

4.3.1 Changes required ... 26

4.3.3 Sustainable Supply Chain Practises ... 29

4.4 Future Prospects for the Fashion Industry ... 32

5. Discussion ... 35

5.1 Key Findings and Relation to Theory ... 35

6. Conclusion ... 38

List of References ... 40

1. Introduction

As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, the global apparel industry is now facing a profound situation which is more serious than any it has faced in over a generation (Anner, 2020; Udin, 2020). The virus has caused a steep rise in unemployment and reduced incomes, therefore the demand for apparel has plummeted, buying clothes is a luxury most cannot afford or justify in such uncertain circumstances (Fashion Revolution, 2020; Udin, 2020). As a further consequence of the pandemic, brands are abruptly cancelling orders which are already in progress or ready for shipment, and refusing to pay for them or cover the cost of raw materials, which has a detrimental impact on suppliers and their workers (Anner, 2020; Human Rights Watch (HRW) 2020; Nova & Zeldenrust 2020), leaving factories buckling under huge economical strain with little choice but to partially or fully shut down. This has so far caused approximately 150 million factory workers at the ‘bottom of the pile’ within supply chains to be made suddenly unemployed, with no financial safety net to support themselves and their families through this indefinite time period (Anner, 2020; HRW, 2020; Udin, 2020).

Supply chains are currently designed to minimise the brands’ responsibility and obligation toward their suppliers (Anner, 2020; Fashion Revolution, 2020). The factory has to cover the cost of all raw materials and labour for every order in advance of payment, as well as the cost of shipping and logistics. The majority of brands only pay production invoices between 30-90 days after the goods are delivered, which leaves suppliers in extremely vulnerable positions with no leverage to defend themselves against price bargaining and the absence of payment (Nova & Zeldenrust, 2020). Therefore, when external events (such as Covid-19) affect the fashion industry and have a knock-on effect on supply chains, vulnerable suppliers at the end of the line are the ones who inevitably bear the brunt of the burden. As they already operate within extremely thin profit margins, they are forced to let go of their employees, because without receiving payments from brands and retailers they have no financial capabilities to pay employee salaries. Further, due to the very minimal wages that the employees receive, their ability to save money to support themselves in times of crisis is essentially non-existent. In fact, persistently low wages have rendered many in debt, which will now continue to accumulate with no means of being paid off (Anner, 2020; International Labour Rights Forum (ILRF), 2020; Nova & Zeldenrust, 2020).

To justify these decisions and reactions to the virus, brands are referring to Force Majeure, a clause in contracts that removes liability under natural and unavoidable catastrophes, that unexpectedly impacts the course of events and restricts parties from fulfilling their obligations (Hargarve, 2019), even though pandemics are not a viable reason not to pay for completed orders, nor does it state in the contracts that Force Majeure is applicable for global health crises. Additionally, according to article 7.1.1 of the Vienna Convention for International Commercial Contracts, Force Majeure should only apply to the partner with the most relevant contractual obligation, which in the current circumstance would in fact be the suppliers, not brands or retailers (Anner, 2020; Nova & Zeldenrust 2020). Regardless of contracts or policies, the power imbalance between brands and suppliers is a critical issue which is ingrained into the current supply chain system.

1.1 Problem Statement

In light of Covid-19, the unsustainability of the existing fashion supply chain has resurfaced into the limelight, however the fundamental faults within the system that have caused millions of workers to be left unemployed and unsupported in the current crisis are not new. Nova and Zeldenrust (2020) state that “Workers, unions, and civil society groups have long argued that worker vulnerability is written into the DNA of global supply chains.”, (p. 7). Low tax revenues have left exporting country

governments with low capability to provide financial help to workers and businesses during the current crisis (Anner, 2020). Current discourse in related publications demand that brands and retailers step up

and take a more equitable approach towards their suppliers as a result of the pandemic (CCC, 2020; ILRF, 2020; Kelly, 2020).

The extreme fragility of the existing fashion supply chain system and its numerous issues are very apparent. As one of the most unsustainable industries in the world (Global Fashion Agenda (GFA), 2019), commitment to contributing to global sustainable development is imperative. Sustainable development is understood in this paper as “... development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Brundtland, 1987), a definition widely used and referred to when discussing sustainability across different industries. The Covid-19 pandemic has reiterated how urgently the reform of the supply chain practises is needed. Not only must supply chains become better equipped for handling unexpected events, transformation is crucial for the industry as a whole to become socially and environmentally sustainable. Whilst business practice as we know it is forced to grind to a halt due to the pandemic, an opportunity has arisen to understand what changes are required for supply chain practises to support the overall sustainable development of the fashion industry.

Throughout this paper the terms ‘systemic issues’ and ‘systemic change’ will be used regularly and refer to the fundamental flaws in the existing fashion supply chain system which have enabled it to be so unsustainable, and therefore also the fundamental changes that are required within the existing system to support the sustainable development of industry.

1.2 Purpose

A variety of existing systemic issues within global apparel supply chains have been exposed by the current Covid-19 pandemic. Using this as a starting point, the purpose of this paper is to understand the current fashion supply chain practises and sustainability issues within it. This will enable the authors to explore what long-term systemic changes are required within the fashion supply chain and to make valuable suggestions, grounded in research and theory, which could be incorporated into the reform of global supply chain practises going forward.

1.3 Research Questions

The following research question has been generated with the aim of meeting the purpose stated above: What systemic changes are required to reform the fashion supply chain to support sustainable development throughout the fashion industry going forward?

A further two sub-questions have been created to help gather appropriate information in order to answer the main research question:

1. What systemic issues within the existing fashion supply chain have been exposed by the current Covid-19 pandemic?

2. How could the current fashion supply chain practises be improved to support sustainable development in the fashion industry?

1.4 Previous Research

In reaction to the recent Covid-19 pandemic, a selection of reports have been published by a number of NGOs, charities, government organisations and reputable fashion organisations which highlight the ways in which the global fashion supply chain, and those working within it, have been affected by the crisis. For example, the Better Buying Institute (2020) produced a special report ‘Guidelines for “Better” Purchasing Practises Amidst the Coronavirus Crisis and Recovery’ which hopes to instruct fashion retailers on how to deal with the current crisis responsibly. Some other organisations that have released

documents include: The Business of Fashion (2020), Traidcraft Exchange (2020), The Centre for Global Workers Rights (2020) and the International Labour Office (2019). The publications discuss the issues which have enabled the events to unfold in the present manner, and make suggestions for changes to buying practises, payment terms, sales models, consumption patterns and various other areas within the fashion industry which could prevent similar events in the future having such a detrimental effect on the industry, and which would make the fashion system fairer and more sustainable. Whilst all of the aforementioned documents are valuable and supported by up-to-date industry knowledge, there is an absence of theoretical references to support a lot of the information presented. Furthermore, the majority of the published reports and papers are focused on the brand perspective or aim to provide strategies for brands to survive the current crisis, whilst neglecting the supplier perspective, even though it could be argued that suppliers are more severely affected by the pandemic as they lack the financial power and governmental support that brands can benefit from.

Current research and academic literature on fashion supply chains and sustainable supply chain management is fairly extensive and provides insights into typical supply chain structures and strategies. For example Talaya, Oxborrowa and Brindley (2018), Hingley (2005), Anner (2020) and Seuring and Müller (2008) have studied the power imbalance in supply chains that allows retailers to profit from the current fashion supply chain model, whilst suppliers are pressured to work under increasingly unstable market conditions. A variety of approaches have been developed which aim to improve the current fashion supply chain system, however these studies mostly focus on improving the environmental sustainability of supply chains and neglect the many social implications. The Triple Bottom Line (TBL) approach is argued to be crucial in developing a sustainable supply chain that takes into consideration all aspects of sustainability: economic, environmental and social (Fung, Choi & Liu, 2019; Moretto,

Macchion, Lion, Caniato, Danese & Vinelli, 2018; Li, Zhao, Shi & Li, 2014). Nonetheless, there is a lack of research regarding sustainable fashion supply chains that covers all three pillars of sustainability. The social side of sustainability is often neglected and there tends to be minimal consideration of the supplier perspective in sustainable development practises and strategies within the research field. This research aims to contribute to the existing research gap by determining what aspects of current supply chain practises require fundamental change, with particular focus on the supplier perspective.

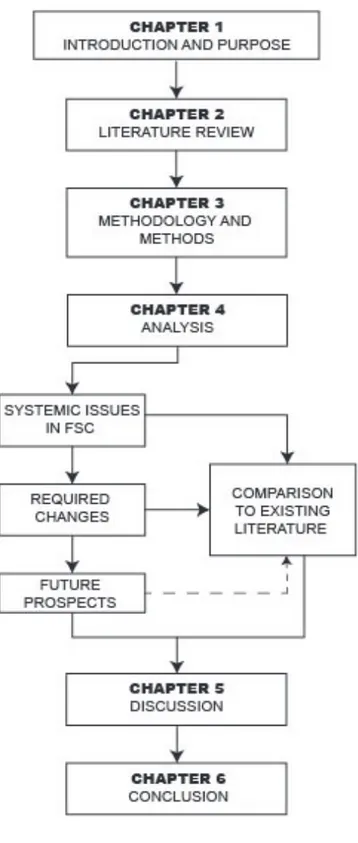

1.5 Thesis structure

Going forward the rest of this research paper is structured as follows: chapter two provides a literature review of key concepts related to fashion supply chains, sustainability in fashion supply chains and sustainable supply chain management within the context of this study. Chapter three explains the methodology and methods used in this research. In chapter four the empirical data analysis is presented and chapter five presents the key findings from empirical data and discusses them in relation to existing theories introduced in chapter two. Lastly, chapter six presents the final conclusions and

2. Literature Review

In this chapter, we present the key concepts which will be used as the theoretical foundation for this paper. In order to be able to pursue the desired avenue of research, and to make well-grounded suggestions for how the fashion supply chain (FSC) practises can be reformed in order to contribute to sustainable development, first a clear understanding of the academic basis of supply chains and existing sustainable supply chain practises is crucial. Through a review of existing literature, the core aspects of FSC, sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) and sustainable practises in FSCs are broken down so as to be best understood by both the reader and the researchers. Thereafter, the concepts of supply chain resilience versus supply chain sustainability are presented as approaches for optimal sustainable supply chain (SSC) performance. The key findings from the literature have been summarised into a visual diagram and can be found at the end of this chapter (Figure 2).

The understanding acquired from the analysis of the proposed concepts will form the basis for the rest of this paper, facilitating a holistically informed perspective to be used when gathering and analysing primary data and to generate suggestions for improving the sustainability of the global FSC.

2.1 The Development of the Supply Chain

Blanchard (2010) provides a simple definition of a supply chain (SC) as the sequence of events that encompass a product’s total life cycle, from conception to consumption, beginning with the original supplier of the raw material and ending with the final consumer of the product. SCs embody “activities that people have engaged in since the dawn of commerce” (Blanchard, 2010 p.6). The concept of SCs and the purpose that they serve are not new, and can be traced back to similar ideas from the Roman Empire where ‘commodity chains’ resembled what we know as SCs today (Juliana, Hsuan & Aseem, 2015). Existing modern SCs have evolved into intrinsically complex systems, largely due to globalization. Over the last twenty years, significant changes in the structure of the global economy have transformed global trade and production (Lund-Thomsen, Hansen & Lindgreen, 2019; Barnes, Lea-Greenwood & Arrigo, 2013). Globalisation has provoked unprecedented levels of international competition across industries; the fashion industry included (Bhardwaj & Fairhurst, 2010). Intense competition in the marketplace, technological developments and booming consumer demand have driven companies to expand their SCs across international borders, strategically seeking overseas manufacturers that can guarantee low labour costs (Juliana et al., 2015; Bhardwaj & Fairhurst, 2010). This method, known as ‘offshoring’, promotes manufacturing in low wage countries with minimal labour regulations, and has led to the development of demand-driven flexible supply chains with quick responsiveness as a vital attribute (Khurana & Ricchetti, 2016; Barnes et al., 2013; Smith, 1996).

2.2 The Fashion Supply Chain

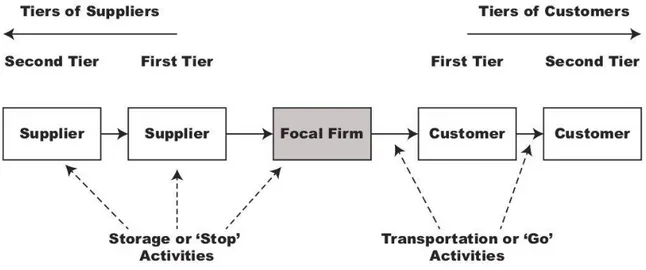

The FSC is described as a complex system due to its global nature, but at the core FSCs are built as any other SCs and require the management of all aspects. Grant et al. (2017) illustrate a simplified SC structure which is applicable to FSCs (see Figure 2.). The term ‘Focal firm’ represents fashion brands and retailers; within the suppliers the ‘First tier’ consists of suppliers and customers who are key partners for the focal firm and the ‘Second tier’ suppliers and customers are then the first tier suppliers and customers key partners, and so on. As Grant et al. (2017) describe, supply chain management (SCM) manages ‘Go’ or ‘Stop’ activities between supply chain partners. ‘Go’ activities include movement of goods forward in the SC, and ‘Stop’ activities include processing or the storage of goods. It must be noted that these activities are far more complicated in reality, especially in FSCs as the SCs are typically global complex systems. Additionally, firms tend to outsource activities that are not part of their core business functions, such as warehousing and logistics, which is an effective way to cut down the costs of operations but which also adds to the complexity of the SC network.

Figure 2. Author’s adaptation of ‘Supply Chain – Simplified’ (Grant et al., 2017)

Product flows in SC usually flow one-way from upstream to downstream. Upstream refers to the supplier and manufacturing part of the SC, and downstream refers to the activities concerning sales and the fulfillment of sold services of goods to the end consumer.

Globalisation has had a significant effect on the fashion industry and FSCs (Turker & Altuntas, 2014; Bhardwaj & Fairhurst, 2010). Moving away from the previous structure of advanced trend presentations at trade fairs and shows, and demand forecasts based on the year previous sales, globalisation, and the increased competition which it brought with it, pushed the fashion industry to evolve towards a new model commonly known as ‘fast fashion’ (Turker & Altuntas, 2014; Bhardwaj & Fairhurst, 2010). Fast fashion product characteristics resemble the nature of the contemporary fashion industry itself: short product life, need for trendiness, inexpensiveness and disposable by nature (Moon et al., 2017). Consequently, contemporary FSC are therefore characterised by short product life cycles, labour intensive and low-tech manufacturing, unpredictable demand, large product variety and low barriers to entry (Chen et al., 2019; Rufi-Ul-Shan et al., 2017). FSCs are also highly globally fragmented, with most manufacturing occuring in low labour-cost countries across South Asia, India and Europe.

2.2.1 Key Elements of Competitive Fashion Supply Chains

For fashion companies to function in a fast-paced market environment, their SC must be agile (Moon et al., 2017; Rufi-Ul-Shan et al., 2017). For a FSC to be competitive it must be flexible, cost-effective and responsive, which can be achieved through agility (Moon et al., 2017). An agile SC requires market knowledge and information in order to cut down the costs of manufacturing and production by ‘channel postponement’ and to be able to benefit from profitable opportunities in volatile markets (Grant et al., 2017). In FSCs this means postponing finalised order placements and inventory logistics to the last minute to reduce the potential risks and costs for the buyer related to the untimely sales of goods. Therefore, fashion brands can benefit from an agile SC that suits the unpredictable environment of the fashion industry, with its strengths in high demand for a variety of goods, as opposed to a lean SC which is better suited to industries that have high levels of predictability and low variety in goods (Grant et al., 2017).

Moon et al. (2017) define SC agility to be the “capability of a supply chain to adapt or respond in a speedy manner both to ever-changing market demands (in terms of value and variety) and to potential and actual disruptions.” Moon et al. (2017) also note that SC agility is an important element for apparel

companies if they wish to survive and thrive in unpredictable markets. Market demand is increasingly difficult to meet as consumers consume fashion based more on want than on need, and demand quick deliveries of goods. This ‘see-now, buy-now’ culture requires FSCs to provide the timely delivery of ‘on-trend’ apparel to customers (Rufi-Ul-shan et al., 2017). For brands to respond effectively to market demands, cooperation and collaboration is vital and requires significant commitment from all partners, which in return can increase the profitability of a SC (Moon et al., 2017).

Knowledge sharing (KS) is a crucial method for supporting collaboration and consequently effective SC performance (Chen et al., 2017). Chen et al (2017) state that by sharing knowledge, members of the same SC can work as ‘single entities’ to respond to market demands together and create value for customers. The research also suggests that KS has a positive impact on SC operation performance by improving response time and high inventory turnover, which enhances the competitiveness of the SC companies.

Many organizations also form long-term strategic relationships with SC partners to manage SC issues and create competitive advantage. Additionally, key relationships with suppliers increase responsiveness, agility, speed and profitability (Rufi-Ul-shan et al., 2017). Cross-supply chain collaboration enables firms to address SC issues, incurred costs and to face risks (Moon et al 2017). Collaboration in SCs supports improved performance of the entire SC as well as individual firms. No company can succeed alone, especially in the fashion industry (Moon et al 2017). Members of a SC who care for each other’s business and conduct activities in a power balanced way, support collaboration and cooperation (Moon et al 2017).

2.2.2 Sustainability in Fashion Supply Chains

The fashion industry is notorious for its use of hazardous chemicals, causing considerable amounts of water pollution and carbon emissions, and for supporting poor working conditions and barely existing labor rights (GFA, 2019). These exploitative traits are enforced by pressures on fashion companies to reduce lead times and costs, which cause production conditions to worsen further and hinder

opportunities for sustainable production practises (Rufi-Ul-Shan et al., 2017). There is a lack of global sustainability standards, legislations and regulations to support sustainability in global supply chains, which combined with the geographical complexity of FSCs results in higher social and environmental sustainability risks (Rufi-Ul-Shan et al., 2017). Additionally, Rufi-Ul-Shan et al. (2017) noted that the most cited reason for a traditional SC to change to sustainable SC is the pursuit of cost and risk reductions, as well as an internal commitment towards sustainability, although stakeholder influence and governmental policies can also positively influence sustainable integration into SC.

SCs are by definition ‘unfair’ and asymmetric relationships are more typical in SCs then cooperation and power symmetry (Hingley, 2015). This imbalance of power in SC is usually benefitting the retailer, who controls the decisions of product development, pricing and delivery, which affects every part of the SC (Moon et al., 2017; Talaya et al., 2018). Suppliers and manufacturers try to balance this power by using sub-contractors to manage orders, reducing their own risks, however this can also increase risk potential across the whole FSC (Rufi-Ul-shan et al., 2017). Furthermore, traderules, financial structures and technological developments have emphasised the power imbalance (PI) found in global FSCs, causing the development of the following two mechanisms: the ‘price squeeze’ and the ‘sourcing squeeze’, which both impact workers in the supply chain (Anner, 2020). The ‘price squeeze’ refers to the main firm’s interest to keep labor costs and wages down. The ‘sourcing squeeze’ refers to time efficiency; the time it takes to design, source, make and ship an item. Anner (2020) also argues that global organisations pressure suppliers and governments of manufacturing countries to keep the wages down in order to keep and attract investors. To address this PI, Anner (2020) suggests that powerful companies'

purchasing practises must be fundamentally changed, by being forced to provide stable orders and share the responsibilities and costs of production.

Talaya, Oxborrowa and Brindley (2018) identify the power features of retailers as ‘application power’ and describe them as the following: 1. Large retailers can press the production prices down, due to their size as they can ‘shop around’ for the cheapest price; 2. Large retailers can enforce suppliers to

collaborate in reducing cost by creating internal design, sourcing and manufacturing sites to increase their (retailers) revenue; 3. Retailers demand small orders but in large varieties, which complicates the supplier’s workload and increases their costs, resulting in a decrease in their economic power; 4. Suppliers are forced to adapt to environmental demands to improve efficiency and retailers enforce social sustainability to protect the brands image (Talaya et al., 2018).

However, Hingley (2015) suggests that weaker organizations tolerate the imbalance of power if it is clear that entering the relationship will benefit them, or if the retailer needs something from them. Talaya et al. (2018) also identified ‘supplier response’ mechanisms, which are the following: 1. Suppliers improve design and employee development in order to respond to retailers demand in short time speed, which is cost effective and simultaneously improves their own competitive advantage that supports sustainable development 2. If suppliers can have higher entry price points (the price of the retailers pay for their goods) than competitors, they usually have higher exit prices as well, which means suppliers goods are not sold for the minimum sales price and provide higher profits to retailers, which provides a better position for the suppliers in the SC. 3. Adhering to retailer’s environmental demands in FSC and other demands is perceived as brand protection activities that can impact brand

performance, similar to retailers’ approach to brand protection. Additionally, being a supplier to high street brands increases the supplier’s presence and visibility in the global SC. (Talaya et al 2018).

2.3 Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Fashion industry

The Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals describe SCM as: “… The planning and management of all activities... Importantly, it also includes coordination and collaboration with channel partners... In essence, supply chain management integrates supply and demand management within and across companies.” (Grant et al., 2017). Whilst the above definition gives an accurate description of typical SCM, it lacks the integration of sustainability. John Elkington’s Triple Bottom Line (TBL) concept has been widely recognised as a beneficial framework for organizations to transform their business into a more sustainable one, by giving equal focus to all three aspects of sustainability: economic,

environmental and social. By applying the TBL approach, the economic value can be maximised without compromising environmental or social value (Fung et al., 2019; Grant et al., 2017; Rafi-Ul-Shan et al., 2017; Li et al., 2014).

As FSC are intrinsically geographically complex, and are composed of characteristics which makes them very subjective to business disruptions and sustainability issues, companies in FSCs need to understand sustainability and integrate it into their business strategies to avoid disruptions and to guarantee SC continuity and viability. Li et al. (2014) state that for companies to become sustainable, they need to change their performance objectives to maximize efforts to all three areas of the TBL, this can lead to enhanced competitiveness by meeting customer needs, economic goals and by deeper collaboration with suppliers which contributes to the fulfilment of long-term goals. Additionally, Li et al (2014) state that Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is an effective governance tool for sustainability in FSC; the focal company sets standards for CSR that are followed by their suppliers, who then enforce CSR practises further up the SC, creating a favorable environment for sustainability. An effective state of equilibrium should be maintained amongst all SC members, from upstream to downstream, to ensure cohesive sustainable development (SD) and thorough strategic sustainability (Li et al., 2014). Key stakeholders in Sustainable Fashion Supply Chains (SFSC) are retailers, designers, manufacturers, distributors and all

stakeholders involved in product consumption (Fung et al., 2019). In order to create a SFSC, retailers need to work closely with their SC network, as considerable efforts are required from each stakeholder to support the SD of the SC (Fung et al., 2019).

Codes of conduct are another way for companies to ensure sustainable practises amongst all of their supply chain partners, in order to achieve SD goals (Talaya et al., 2018; Grant et al., 2017). This also allows for companies to follow the chain of custody of raw materials and assists with traceability, however it also enables retailers to absolve themselves of the associated risks and obligations, instead passing them on to their suppliers (Talaya et al., 2018). Grant et al. (2017) state “what goes downstream in the supply chain must also come back upstream: hence reverse logistic is important” (p.33),

highlighting reverse logistics as a key part of SSCM. Reverse logistics address all activities of SCs, it aims to reverse the logistics in the opposite direction from the typical one-way flow. However, efforts like reverse logistics, closed-loop SC and other SSCM development initiatives can increase the complexity of SCs.

2.3.1 Drivers for Sustainable Supply Chain Management

Mann et al. (2010) suggested five external and internal drivers of SSCM. External drivers are: compliance to country specific legislation and environmental aspects forced by legislation; CSR measures; and consumer demand. Internal drivers are: better financial performance and higher revenues as a result of sustainable performance; internal business functions that affect process; operations such as reverse logistics; and social drivers such as stakeholder management to satisfy stakeholder needs and demands. External stakeholder pressures support proactive firm-intrinsic learning towards SSCM by creating urgency, while internal pressures can hinder SD as members of the organization might not be able to achieve consensus over SD (Roy et al., 2020). Therefore, Roy et al. (2020) suggest Organizational Learning towards Responsible Management (OLRM) which implies internal processes in firms to develop sustainable oriented learning through knowledge acquisition, knowledge distribution, knowledge

interpretation and organizational memory. OLRM requires internal refocus to internal learning to acquire and develop knowledge that supports SSC performance (Roy et al., 2020).

Interestingly, Seuring and Müller (2008) argue that only proactive companies create SSC, not in response to non-governmental organization (NGO) pressures or consumer demand. The scholars support that supplier monitoring (eg. codes of conduct) is an important factor that creates a ‘baseline’ for

sustainability in SSCM. This is echoed by Roy et al. (2020), although their findings suggest that proactive firms are in fact created from external pressures; internal and external pressures provide specific triggers that affect operational responses to sustainability in various ways. Roy et al. (2020) identified ‘two pathways to manufacturers' contribution to SC sustainability performance. Firstly, they recognised a reactive pathway, which implies suppliers acting only on sustainability pressures, which leads to fragmented input. The second pathway is proactive, where suppliers make deliberate efforts towards sustainability from an organizational level through firm-intrinsic learning. These actions can fundamentally support SD and practises in FSCs (Roy et al., 2020).

Grant et al. (2017) state that there is an increased need for collaboration and for relationships benefitting all stakeholders of a SC in order to positively affect sustainability. Relationships with key suppliers and retailers also allow for improved management of social and environmental sustainability issues (Rufi-Ul-Shan et al., 2017). Product design also affects all parts of the SC, therefore product development may require collaborative design development with suppliers, to ensure sustainability throughout the product life cycle, from manufacturing to end of life (Grant et al., 2017). In support of this, Fung et al. (2019) state that the TBL should also be considered at the product design stage to support SD.

Communication and KS support collaborative behaviour and cooperation, they can also increase awareness levels and bonds between suppliers and buyers (Talaya et al., 2018). It is found that when the relationship between focal firms and their suppliers is based on transparency and trust, it supports SSCM (Oelze, 2017). Thus, communication of SC functions has become an important transparency practice for many companies, which is demonstrated by providing supplier and factory information to stakeholders according to Turker and Altuntas (2014). Product level transparency is also found to be a component that supports formation of SSCs and improves ‘sustainable business economy’ according to Fung et al. (2019). Grant et al (2017) also state that ‘greening of supply chains’ is collaborative effort and that collaboration usually increases sustainable performance levels overall in global markets (Li et al., 2014). This is supported by Seuring and Müller (2008), who argue for the cooperative development approach and the benefits of strong communication between suppliers throughout the SC. By outsourcing SC activities, e.g logistics and warehousing, firms may lose some control of their operations despite agreements and contracts, thus losing control of sustainability efforts (Grant et al., 2017). Therefore, managers should take a development approach to working with their suppliers, i.e not relying solely on performance measurements, to monitor sustainable compliance and optimise opportunities for advanced SD (Moretto et al., 2017).

Moretto et al. (2018) suggest that organizational structure needs to engage employees through

education, KS, and with clear goals for sustainable activities to support the overall sustainable practises of the company, therefore sustainability should be implemented into the core of the company.

Additionally, Moretto et al. (2018) suggest the use of a ‘roadmap toward sustainable supply chain’ as fashion companies core interests are not usually to address sustainability issues, they often lack a structured approach to sustainability. The writers argue that usage of this roadmap allows managers to combine operational and organizational practises, and environmental and social sustainability practises, without losing focus.

2.3.2 Sustainability Challenges in Sustainable Supply Chain Management

Creating a SSC requires consideration of both environmental and social aspects, however the existing literature and research largely focuses only on the environmental aspects (Fung et al., 2019; Jabbarzadeh et al., 2018; Rajesh, 2018; Rufi-Ul-Shan et al., 2017; Fahimnia & Jabbarzadeh, 2016; Seuring & Miller, 2008), which some scholars argue is due to there being no consensus regarding reporting and measuring social sustainability within SCs (Rufi-Ul-Shan et al., 2017; Fahimnia & Jabbarzadeh, 2017). As Grant et al (2017) state, ‘greening’ of SC focuses on environmentally friendly activities across SC functions,

emphasis on reducing carbon emissions. They argue that the responsibility to create ‘green supply chains’ relies on collaborative efforts between transport services, governments and non-government policy makers only, excluding the main companies, such as fashion brands, from the equation. Social implications of SSCM are often missed altogether or focus is given only to the more tangible elements such as, number of jobs created and exposure to dangerous chemicals, highlighting a shortfall in holistic TBL perspective to SSCM (Rufi-Ul-Shan et al., 2017; Fahimnia & Jabbarzadeh, 2016).

It is imperative for companies to change their performance objectives to maximize profits to all three areas of the TBL, without trade-offs, if they aim to become sustainable organizations (Li et al., 2014). Organisations that have started on the journey to sustainability, tend to fail due to following traditional business management methods that do not support all TBL aspects. Change for sustainability requires managers to develop a strategic long-term plan and vision that involves all areas of the TBL (Moretto et al., 2018), as is supported by Fung et al. (2019) "any failure in social sustainability will harm the business" (p.7). This statement is reinforced by reports of a fast fashion company’s total revenue decrease due to their failure to address social sustainability issues, such as the use of sweatshops and excessive waste created by their business model (Fung et al., 2019).

2.4 Sustainability Versus Resilience in Supply Chains

Fashion companies have benefited for decades from the existing SC structures and the strategies within it, however there are also considerable risks involved that can reduce an organisation’s capability to withstand unexpected disruptions (Jabbarzadeh et al., 2018; Rafi-Ul-Shan et al., 2017; Fahimnia & Jabbarzadeh, 2016). The recent Covid-19 disaster, as well as a number of previous economic, natural and political disasters, have demonstrated how dramatic the consequences of disruptions can be on SCs, and emphasise how important it is for SCs to be designed with resilience and sustainability at their core (Jabbarzadeh et al., 2018; Rafi-Ul-Shan et al., 2017; Fahimnia & Jabbarzadeh, 2016; Papadopulous et al., 2016; Silvestre, 2015).

The definition of a resilient supply chain (RSC) is commonly understood as the ability for a SC to absorb disturbances whilst maintaining its core functions and original form (Jabbarzadeh et al., 2018; Fahimnia & Jabbarzadeh, 2016; Papadopulous et al., 2016 Silvestre, 2015). The robust resilience of a SC is created by careful design which makes it resistant to disruption risks (Jabbarzadeh et al., 2018; Rajesh, 2018;

Fahimnia & Jabbarzadeh, 2016; Silvestre, 2015), and is grounded in base principles of agility and flexibility (Rajesh, 2018). Within SC resilience research there is a lack of consideration of sustainability factors, as well as a lack of investigation into the impacts of risk mitigation strategies on supply chain sustainability. Jabbarzadeh et al. (2018) argue that this is insufficient given the necessity for all contemporary

businesses to incorporate SD into their core operations.

SSCs are generally understood as eco-efficient SCs that also consider social and ethical issues, whilst consistently trying to reduce all forms of waste, and engaging in strategic partnerships to enhance responsiveness and innovation through collaboration (Jabbarzadeh et al., 2018; Rajesh, 2018; Silvestre, 2015). SSCs are progressive forms of green SCs that integrate all elements of sustainability into the traditional cost-orientated SCM operations and have a wider series of performance objectives (Jabbarzadeh et al., 2018; Rajesh, 2018). Despite this, it is commonly acknowledged that the social element of SC design is often neglected (Fung et al., 2019; Jabbarzadeh et al., 2018; Rajesh, 2018; Rufi-Ul-Shan et al., 2017; Fahimnia & Jabbarzadeh, 2016; Silvestre, 2015; Seuring & Miller, 2008)

A few authors have touched upon how SC sustainability is incomplete without consideration of how sustainability initiatives can affect and potentially impede system resilience (Jabbarzadeh et al.,

2018;Fahimnia & Jabbarzadeh, 2016). This sentiment is echoed by Fiskel (2006) who states the need for progression past the ‘steady state model’ of sustainability, to develop adaptive strategies that balance resilience capabilities with long-term human and ecological prosperity. This highlights the research gap and increasing demand for joint consideration of sustainability and resilience in supply chain design to optimise both approaches and maximise overall SC performance. A hybrid methodology for designing resilient and sustainable SC proposed by Jabbarzadeh, Fahimnia and Sabouhi (2018). This methodology demonstrated that although overall SC cost increases as it becomes more sustainable, the increase in supply chain sustainability simultaneously enhances the supply chain resilience, and its cost performance is less affected by disruptions (Jabbarzadeh et al., 2018). The hybrid approach presented is proven to be successful in enhancing the cost performance of the SC when using sustainability and resilience

approaches in combination with one another, therefore validating a more holistic approach to SC design and development.

The insight gained from the aforementioned studies, as well as all of the literature analysed form the theoretical background presented in this chapter, will be used as the basis for the rest of this research

paper. The literature summary diagram (see figure 2. below) presents the key concepts from the existing body of knowledge of FSC and sustainable FSC practise.

3. Methodology and Methods

The purpose of this paper was to understand the current FSC practises and the issues within them, in order to explore what systemic changes are required within the FSC to support the overall SD of the industry. Therefore, the epistemological position taken for the research is interpretivism, as the authors aimed to answer the research questions through studying different SC actor’s perception of the issues and changes required in the FSC. The interpretivist approach requires researchers to interpret elements of the study in order to find the subjective meaning of social action (6 & Bellamy, 2012; Bryman, 2012) therefore integrating human interest into a study. The chosen data collection methods also compliment the interpretive approach, as interpretivism is based on naturalistic methods of data collection such as interviews and observations, as well as finding meaning in secondary data (Dudovskiy, 2018).

This chapter explains the choice of an inductive approach to the research with an explorative purpose, and further describes the use of qualitative methods for both collecting and analysing primary and secondary data. Reliability, validity, ethics and limitations are discussed, and the chapter concludes with the presentation of the object of study.

3.1 Research Design

The research followed an inductive approach, meaning that any assumptions and suggestions made are based on research results. The results are objective as researchers generalise their findings to develop theories (Bryman, 2012). The research had an explorative purpose and followed qualitative methods. The explorative purpose allowed the researchers to satisfy their own curiosity whilst providing a better understanding of the studied field, while qualitative methods allow for in depth research and therefore a deeper understanding of the studied topic (Silverman, 2015; 6 & Bellamy, 2012).

This study focused on global FSC practises, more explicitly on the systemic issues existing in the FSC that were heightened by the Covid-19 pandemic in spring 2020. The explorative purpose of the study allowed the researchers to gain insights of different FSC stakeholders experiences and their perceptions of FSC issues. The aim was to gather a comprehensive understanding of existing SC issues and changes required from a supplier perspective and compare these findings to key concepts explored in the literature review. This enabled the researchers to identify commonalities, gaps and new insights to support the required change towards a more sustainable fashion industry and SC practises. The research was considered as an iterative process, with constant reflection on the data gathered.

3.2 Data Collection Methods

3.2.1 Secondary data

Secondary data was gathered in three different manners. Firstly articles, reports and other relevant industry resources were collected and reviewed in the initial stages of the research in order to get a base understanding of the current issues within the fashion industry which have been highlighted by the Covid-19 pandemic. A summary of these resources has been documented in Appendix 1. of initial secondary resources. Thereafter, a literature search was conducted using Malmö University Libsearch service and the Google Scholar platform to provide an extensive understanding of the topics discussed in the literature review, which was synthesised to form the theoretical foundation for this paper. Lastly, a key-word search was conducted on the Google search engine from April 9th to April 15th, 2020 to find further resources to confirm and validate the information previously deducted from the first round of secondary data collection. The keyword data collection on Google focused on three main keyword

combinations: 1. “Covid-19 fashion” that resulted in 388,000 hits, of which first 50 search results were focused on and further filtered based on the following words and phrases occuring in the title or description of the text: collaboration, Covid-19 affects, sustainable fashion, fashion in time of covid and survival strategies. 2. “Covid-19 fashion industry” search resulted in 3960 hits in total of which the first 50 results were screened and final selection was based on the following themes occurring in the title or description: fashion industry, post Covid-19, sustainable fashion, global impact and impact of covid-19. 3. “Covid-19 fashion sustainability” resulted in 420,000,00 hits and as before, the first 50 hits were

examined with the focus on the following themes: Covid-19, greenwashing, sustainable fashion and sustainable designer. All together 150 results were analysed and narrowed down to only relevant publications corresponding to the research topic of this paper. This selection contained mainly

newspaper articles so it was narrowed down further to only include two reports published by the most legitimate sources and a content analysis was conducted, together with the most relevant report found in the initial stages of the research process. This document analysis, and the findings from it, were used in combination with primary data gathered from interviews to broaden the scope of data gathered and to provide deeper understanding of the research topic. See Appendix 2. for the table of analysed documents.

3.2.2 Primary data

Primary data is collected with a specific purpose for a study (Bryman, 2012). In this paper primary data was collected from semi-structured interviews using open ended questions, which allows researchers to better understand the studied phenomena based on the interviewees experience and knowledge of it. It also allows for interviewees to express themselves more freely, whilst the interview follows a preset theme and questions that should be discussed (Bryman, 2012). Another reason for conducting interviews for this study was to gather extensive knowledge about sustainability issues in FSC from different industry professionals, and to understand what actions are required to create systemic change in order to alleviate the mentioned issues in FSCs. Furthermore, the interviews provided a method to investigate the concepts explored in the theory background, such as collaboration, in more depth, as well as how these concepts impact the different stakeholders of FSC, such as suppliers and brands, independently.

Each interview followed an interview guide with set themes to ensure that the same main focus areas of the study were discussed during each interview (see Appendix 3). For each theme a set of questions were prepared beforehand and were modified slightly to match each interviewee, which allowed interviewees to answer questions to the best of their personal knowledge and capabilities. Each theme was selected based on prior theoretical analysis of FSC and SSCM in existing literature.

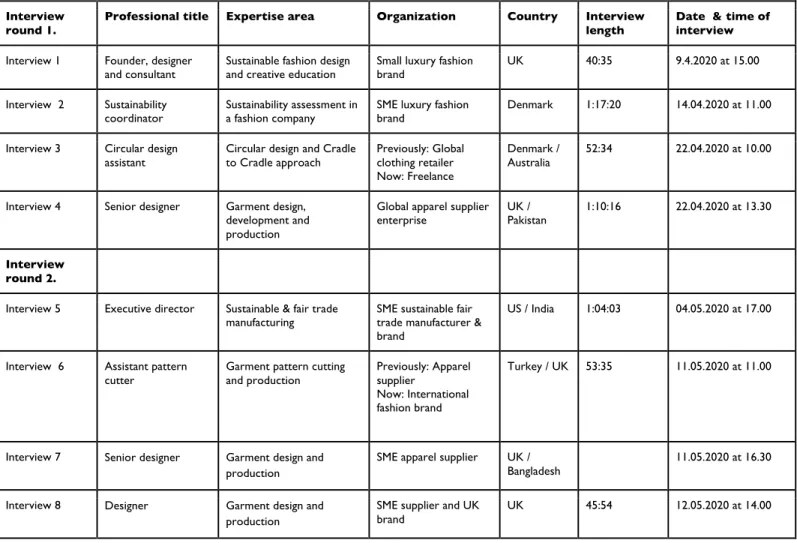

In total eight interviews were conducted with fashion professionals that had been working in the industry for at least two years or more. Originally, the focus of interviews was to gain an overall understanding of the FSC sustainability challenges and how these issues were amplified by Covid-19. However, following elements of the grounded theory approach (Silverman, 2015; Byrman, 2012), data from the first four interviews was analysed to understand the most prevalent themes at that point in the process. From this initial analysis, it was decided that the research focus would shift to concentrate on the supplier stakeholder perspective, as it appeared that the supplier interview responses provided new information, some of which was contradictory to the current body of research regarding sustainability in FSC. Moreover, this decision was made due to the lack of existing academic literature which focuses on the supplier perspective. Therefore, the remaining four interviewees were all from the supplier side of the SC, in order to delve deeper into their understanding of existing issues and the potential changes required. Lastly the aim of conducting multiple interviews was to reach a saturation point, where no new information, ideas, thoughts or views would have been found. By reaching a point of saturation, research could conclude that the studied phenomenon is explored extensively (Silverman, 2015;

Byrman, 2012). The saturation point was reached in this study after the eight interviews. All interviews have been conducted by Zoom, the conference call online platform and lasted between 40 to 80 minutes. Interviews were conducted from 9th of April to May 12th.

3.3 Data Analysis Methods

This study required data interpretation, reflection and connection building between key themes found in primary and secondary data. The analysis of data required an in-depth approach that goes beyond the description of codes, and finds the underlying themes and connections within the data. Collected data has been analysed using content analysis methods and elements of the grounded theory framework as it supports the overall inductive approach, as data coding in grounded theory includes constant revision of established themes and codes (Bryman, 2012).

3.3.1 Interview Analysis

Firstly, the content of the conducted interview transcripts was analysed to establish codes. Codes were established by highlighting words, sentences and paragraphs which seemed most relevant to the research topic. The frequency of which they appeared in the transcript, or how often the interviewee referred back to the same specific topic area during the interview was acknowledged and documented. An additional comparative keyword analysis (CKA) was then conducted on each transcription to identify further features that may have previously been missed and could otherwise go unnoticed. CKA is considered as part of an inductive approach and fits well with the concept of grounded theory (Silverman, 2015).

Secondly, codes were organized to categories based on the theme of the codes. Codes were continuously revisited to guarantee an accurate thematic categorization of codes, which supports cohesive results in data analysis as the data is subjective to the researchers' interpretations of it (Silverman, 2015; Bryman 2012). Initial data analysis coding and categorization was conducted on the first four interviews and thereafter, data collected from the further four interviews was used to compare to the already established categories, by comparing and revisiting new and old data until data saturation was reached (Silverman, 2015; Bryman, 2012).

Table 1. An example of the interview data coding and categorisation process.

Category Code(s) Quotes/ Comments Interpretation

Systemic Issues Pace of the industry +

Relentless growth Interview 1. 1. Because the whole industry sustains itself by running at an extremely fast hamster wheel and only way everyone can kind of profit from that is if it goes faster and faster and faster. 2 .And because they've been running at such a fast pace for so many years, they've been unable to invest in any other income revenues or newer ways of working and thinking because they've been running increasingly quicker and quicker to keep up with shareholders demands to constantly increase profits.

The increasingly fast paced nature of the industry, and the growth mindset of selling more and more to create more and more profit, has created a system which resembles a non-stop hamster wheel that could not have been stopped without Covid-19.

3.3.2 Document Analysis

Document analysis was conducted by following the steps of content analysis, which supports

investigation of a wider set of textual data (Silverman, 2015), and followed a thematic content analysis approach. This is a common approach for analysing documents and can be recognised in many qualitative data analysis approaches, such as qualitative content analysis (Bryman, 2012). The thematic analysis method allows researchers' judgment to determine the themes used, although themes need to be constant within an analysis (Nowell, Norris, White & Moules, 2017; Bryman, 2012). Additionally, themes

are used to combine fragments of data that might be meaningless alone and to capture important factors in relation to the research purpose (Nowell et al., 2017). The first step of the content analysis was to establish themes and count the number of times those themes appear in the studied text. In this analysis, the themes used in this research were generated from the interview data analysis categories, such as “Systemic issues”. The themes used were generated inductively from primary data, supporting data driven analysis (Nowell et al., 2017). The purpose of the document analysis was not to specifically answer the research questions, but to support the analysis of the interview data. By identifying the frequency of the themes from the interview data within the documents, the document analysis provided a background and deeper understanding of the interview answers.

Table 2. An example of the document data coding and categorisation process.

Category Frequency Document Quotes/ Comments Interpretation

Systemic Issues 5 The State of Fashion 2020. Coronavirus Update - McKinsey & Company

Fashion, due to its discretionary nature, is particularly vulnerable. The interconnectedness of the industry is making it harder for businesses to plan ahead.

Fashion industry is vulnerable for disruptions and the interconnectedness hinders long-term planning.

A simplified combined data coding table can be found in Appendix 4, and a google link to the master spreadsheet for all data coding and categorisation can be found in Appendix 5.

3.4 Reliability and Validity

The issue of reliability deals with replicability, whether the same study could be repeated at a different time or by different researchers and still yield the same results (Silverman, 2015). As this study has followed an inductive approach, there is a risk of error as there are multiple hypotheses, patterns and regression lines that can be developed from the data set (6 & Bellamy, 2012). For qualitative research, this can be difficult to guarantee as quite often results are reliant on various people’s personal

experiences and feelings at that given time. One way to assure reliability in qualitative research is by recording and coding conducted interviews and clearly documenting the methods and strategies which will be used in the research report in appropriate detail, therefore these steps were followed to ensure reliability in this study. By using a combination of methods such as interviews and content analysis, and checking if the findings from these various methods align and draw similar conclusions, validity will also be established as much as possible (Silverman, 2015).

3.5 Ethical Considerations

During the research process, different actions were undertaken to ensure trust with the interviewees. The interviewees were approached in a professional manner via email or LinkedIn, and the main purpose of the research and the requirements for the interview were explained. All interviewees were informed in advance that their data would be used in this Master thesis, and the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses was assured. None of the interviewees expressed concern regarding confidentiality or consent. All participants consented to the recording of the zoom meetings prior to their starting and no non-disclosure agreements were requested due to the trust built. The majority of the interviewees expressed support for the research purpose and a keen interest in reading the thesis once completed.

3.6 Limitations

This research has numerous limitations. Firstly, the theoretical background for social sustainability practises in FSC is limited and the existing body of knowledge focuses largely on brands' perspective of sustainable practises in FSC and somewhat disregards the supplier perspective. Therefore, this research

is aiming to contribute to the existing research gap in FSC studies, however as it is an underdeveloped research area further studies are also required, to validate and support any conclusions made in this study.

Due to the professional backgrounds of the interviewees, mainly issues within high-street brands and retailers, and their supply chains and suppliers, have been considered for this research. The luxury sector of the fashion industry has therefore not been included in the research scope, and any findings of this paper may not be applicable for that side of the industry.

Furthermore, primary data was collected from a limited amount of interviews due to the time and scope restrictions assigned to this paper. Whilst the data gathered from the interviews is valid, although subjective to researchers' interpretations of it, a larger interview pool would have further supported the legitimacy of the research findings. Additionally, the research was conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic which could have affected the perspectives of interviewees as their businesses were under stress or they were furloughed from their work. Consequently, this may have affected their experience of the studied phenomena and the interview answers. Ideally, the time frame to conduct the research would have surpassed the Covid-19 pandemic, which would have enabled the researchers to compare the perception of the issues that were amplified by the pandemic to the perception of the same issues under more normal circumstances within FSCs. In doing so, a more extensive conclusion regarding the systemic changes required in FSC could have been developed.

3.7 Presentation of Object of Study

The global fashion supply chain is intrinsically complex and geographically fragmented, with numerous different organisations and parties providing different functions and services upstream and downstream in the sequence of events that encompass a product’s total life cycle, and which have a knock-on effect on the rest of the SC (Juliana et al., 2015; Bhardwaj & Fairhurst, 2010). Globalisation has provoked unprecedented levels of business competition throughout the fashion industry, which has driven the steady increase in pace and rate of growth at which the industry and everyone within it must operate in order to survive (Khurana & Ricchetti, 2016). However, in a way that has never occurred before, the Covid-19 pandemic has ground the industry to a halt, causing unprecedented levels of disruption. The virus has already left a detrimental impression on the world that will not be easily forgotten. Aside from the grievous amount of human victims it leaves behind, the pandemic has also already had a serious impact on the global economy. Countries across the world are having to impose national lockdowns to protect citizen health and avoid exhausting vital resources such as healthcare, food and energy supplies. Consequently, this has resulted in significant production, shipping and logistical issues, mass order cancellations and high levels of job loss across the SC (Better Buying, 2020). In wealthy countries, governments are coming to the rescue for their citizens and businesses with financial support and coherent direction, but unfortunately this is not the case in developing countries (Clean Clothes Campaign (CCC), 2020; ILRF, 2020). As Nova and Zeldenrust (2020) state, many major apparel

exporting countries lack the sufficient public financial resources to cover the health costs caused by the pandemic and to support their apparel labour force, due to decades of poor buying practises and

imbalanced power dynamics (PD) between SC parties. Vulnerable suppliers at the end of the line are the ones who inevitably bear the brunt of the burden, and as a result over 150 million factory workers have now found themselves unemployed, with no financial security or hopes of governmental support (CCC, 2020).

The impacts of Covid-19 have highlighted a multitude of issues within the FSC and its practises. For the purposes of this paper, interviews were conducted in order to understand these issues and the changes

that fashion professionals working directly within the SC believe to be required to make the FSC more holistically sustainable. Interviews were initially aimed at a wider interviewee pool within the fashion industry, so that the studied phenomena would be explored and understood from both the supplier and the retailer perspective, to ensure a balanced initial understanding. After reviewing the first round of interviews, the focus of the data collection was shifted towards the supplier perspective, as it was found that this sector of the FSC is under-represented in current academia and has been most heavily affected by the existing issues in FSCs.

The interviewees had a range of professional experience within different sized organisations located in different continents, therefore bringing a variety of insights and opinions to the study. However it must be noted that the majority of interviewees worked in the high-street sector of the industry as opposed to the luxury sector, therefore when brands and retailers are discussed going forward the authors are referring to high-street brands and retailers. The interviewees chosen worked with teams in a variety of geographical locations, therefore insight was given into how the effects of the virus and issues within the FSC have been felt in the West, and in manufacturing countries such as Pakistan (Interview 4), India (Interview 5), Bangladesh (Interview 5; Interview 7) and Turkey (Interview 6). As job loss is also being felt as an effect in the Western market, all interviewees, apart from Interviewee 5 who is the executive director of their own company, had either lost their jobs, been furloughed or had experienced

cancellation of freelance work due to Covid-19.

Table 3. Interview profiles

Interview

round 1. Professional title Expertise area Organization Country Interview length Date & time of interview

Interview 1 Founder, designer

and consultant Sustainable fashion design and creative education Small luxury fashion brand UK 40:35 9.4.2020 at 15.00 Interview 2 Sustainability

coordinator Sustainability assessment in a fashion company SME luxury fashion brand Denmark 1:17:20 14.04.2020 at 11.00 Interview 3 Circular design

assistant Circular design and Cradle to Cradle approach Previously: Global clothing retailer Now: Freelance

Denmark /

Australia 52:34 22.04.2020 at 10.00

Interview 4 Senior designer Garment design, development and production

Global apparel supplier

enterprise UK / Pakistan 1:10:16 22.04.2020 at 13.30

Interview round 2.

Interview 5 Executive director Sustainable & fair trade

manufacturing SME sustainable fair trade manufacturer & brand

US / India 1:04:03 04.05.2020 at 17.00

Interview 6 Assistant pattern

cutter Garment pattern cutting and production Previously: Apparel supplier Now: International fashion brand

Turkey / UK 53:35 11.05.2020 at 11.00

Interview 7 Senior designer Garment design and production

SME apparel supplier UK /

Bangladesh 11.05.2020 at 16.30

Interview 8 Designer Garment design and production

SME supplier and UK

To broaden the scope of data gathered and to provide deeper understanding of the research topic, three documents were analysed. As they are referred to in the analysis chapter, document 1 is ‘The State of Fashion 2020. Coronavirus Update’, a report published by the highly reputable fashion media company Business of Fashion and McKinsey & Company, a global management consulting firm, which aimed to understand the Covid-19 impact on the fashion industry. Document 2 is the report ‘Guidelines for “Better” Purchasing Practises Amidst the Coronavirus Crisis and Recovery’ published by the Better Buying Institute, a non-profit global initiative platform which provides data-driven insights into purchasing activities, in April 2020. The report presents results from a survey of 294 suppliers from 39 countries regarding impacts and best practises suppliers globally are experiencing as a result of the coronavirus crisis and guidelines for retailers and brands. Document 3 is ‘Supply Chain Sustainability: A Practical Guide for Continuous Improvement’ a document published by the United Nations Global Compact in 2010 to provide guidance for companies to improve sustainability actions in their supply chains.