1

Problematizing Discourse on

Poverty and Social Justice

A critical analysis of the knowledge production of SDG

education materials in the context of Nord Anglia Education

Bogáta Kardos

Department of Education Master Thesis 30 HE credits

International and Comparative Education

Master Programme in International and Comparative Education (120 credits)

Spring term 2020

2

Table of contents

List of Abbreviations ... 6 List of Figures ... 8 Abstract ... 6 Acknowledgements ... 9 Chapter 1 – Introduction ... 101.1 Background of the study ... 12

1.1.1 Equity in education and education for all ... 12

1.1.2 Human rights and social justice ... 14

1.1.3 International schools ... 16

1.1.4 Nord Anglia Education ... 17

1.1.5 SDG education and the World’s Largest Lesson ... 19

1.2 The aim of the study, objectives and research questions ... 19

1.2.1 Objectives ... 21

1.2.2 Research questions ... 21

1.4 Relevance of the study to the field of international and comparative education ... 22

Chapter 2: Conceptual and theoretical framework ... 23

2.1 Globalization and poverty ... 23

2.1.1 What is globalization? ... 23

2.1.2 The global economy ... 24

2.1.3 Poverty in the global, neoliberal, capitalist world order ... 28

2.1.4 Intersectionality and the global world order ... 31

2.1.5 The transnational feminist critique of capitalism and neoliberalism ... 32

2.2 Globalization and education ... 36

2.2.1 Knowledge economy and educational policy ... 36

2.2.2 Critical pedagogy ... 38

2.2.3 Intersectionality and transnational feminism in education ... 40

Chapter 3 – Methodology ... 42

3.1 Discourse analysis ... 42

3.1.2 Hegemony ... 43

3

3.3 Feminist and Transnational Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis ... 44

3.4 Ontological and epistemological considerations ... 45

3.5 Research design and strategy ... 47

3.6 Research Process ... 48

3.6.1 Process of analysis ... 48

3.6.2 Selection of materials ... 49

3.7 Quality criteria ... 50

3.8 Limitations and delimitations ... 51

3.9 Ethical considerations ... 51

Chapter 4 – Findings ... 53

4.1 Why It Matters – Poverty, SDG 1... 54

4.1.1 The general format of Why It Matters – Poverty ... 54

4.1.2 Poverty is caused by hindrances in productivity... 55

4.1.3 Poverty affects a huge part of the population and many children, mostly in developing countries ... 55

4.1.4 It is financially affordable therefore possible to eradicate poverty on the long-term ... 55

4.1.5 Poverty affects the whole worlds because it causes tension and hinders economic growth 56 4.1.6 We can all help in the eradication of poverty as individuals ... 56

4.2 Why It Matters - Zero Hunger, SDG 2 ... 56

4.2.1 The general format of Why It Matters – Zero Hunger ... 56

4.2.2 Hunger is caused by insufficient dealing with food and food resources ... 57

4.2.3 Hunger affects a big part of society and it is growing ... 57

4.2.4 Hunger has to be eradicated because it hinders people from being productive and it is a barrier to fulfilling sustainable goals ... 58

4.2.5 We can help by making conscious individual choices in our food consumption ... 58

4.3. Why It Matters – Clean Water and Sanitation ... 58

4.3.1 The general format of Why It Matters - Clean Water and Sanitation, SDG 6 ... 59

4.3.2 Water scarcity affects an increasingly big part of the population ... 59

4.3.3 The lack of access to clean water is caused by pollution and insufficient infrastructure and managements to treat water waste ... 59

4.3.4 Water sustainability is a human right, essential for economic growth and for the achievement of other SDGs, gender equality and good health ... 60

4.3.5 With the involvement of civil society and raising awareness this goal can be achieved .... 60

4.4 Why It Matters – Equality, SDG 10 ... 60

4.4.1 The general format of Why It Matters – Equality, SDG 10 ... 61

4.4.2 Inequality is caused by many aspects and concerns a big part of the population, especially developing countries ... 61

4

4.4.3 Inequality hinders social and economic growth, and induces several further social problems

... 62

4.4.4 Social inequality affects everyone because of the interconnectedness of the world and because it persists everywhere ... 62

4.4.5 Transformative change is needed to achieve this goal and inclusiveness in social and economic growth must be promoted ... 62

Chapter 5: Analysis ... 64

5.1 The nature of poverty in the texts ... 64

5.2 Causes of poverty identified in the texts ... 66

5.3 The social and economic system that the text is looking for solutions for poverty in ... 67

5.4 The connections drawn between poverty to other forms of oppression ... 69

Chapter 6: Discussion ... 70

6.1 The relation of the knowledge created by the Why It Mattes materials and the social imaginary of Nord Anglia ... 71

6.2 The discourse about poverty and social justice ... 72

6.2.1 A competitive society striving for constant development and growth ... 72

6.2.2 A hierarchal global community ... 73

6.2.3 Making the world a better place as an individual mission ... 74

Chapter 7 - Pedagogical and moral implications arising from the analysis ... 75

Chapter 8 - Further research ... 77

Chapter 9 - Conclusion ... 78

References ... 79

Other sources ... 82

Why It Matters materials ... 83

6

Abstract

Education has an important role in working towards equity and social justice. Education is assigned the role to balance out inequalities in education, and to provide people with opportunity for social mobility. This thesis seeks to critically explore international curricula in the context of an international private school company. The theoretical framework of this study is drawn on moral philosophy (Pogge), intersectionality and transnational feminist theory (Mohanty and Nancy Fraser), and previous critical knowledge on globalisation, international schools, social inequality and social justice. This study seeks to conceptualize a critical position towards the neoliberal agenda organizing globalization and argues that the current system actively maintains social inequality and poverty. It takes a stance against the globalizing, neoliberal, capitalist economy, claiming that it is inherently hierarchical, maintains the current hegemonic status quo between the social classes, and deprives big groups of people of their basic human rights. Furthermore, this thesis claims that educational actors have moral responsibility in striving for a more equal society. The scope of the research is the discourse on poverty and social justice created by an international, private school company, Nord Anglia Education and by educational materials for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Key words: education and morality, social justice, poverty, neoliberalism, transnational feminism, critical discourse analysis

7

List of Abbreviations

CDA Critical Discourse Analysis

DA Discourse Analysis

FCDA Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis

IMF International Monetary Fund

MUN Model United Nations

SDGs Sustainable Development Goals

UN United Nations

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and

Cultural Organization

UNICEF United Nations International Children’s

Emergency Fund

WB World Bank

8

List of Figures

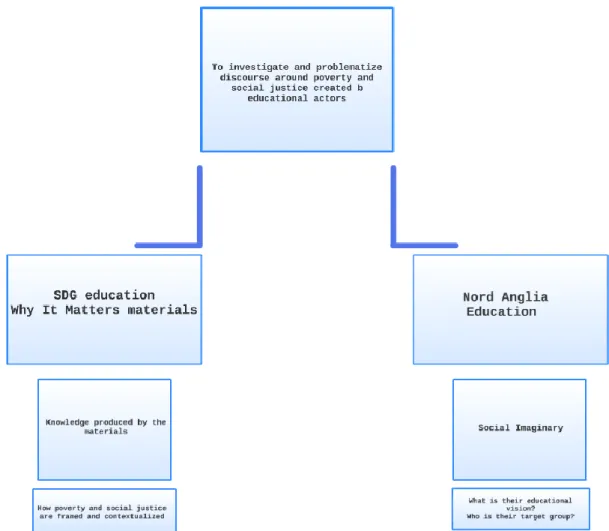

Figure 1: The illustration of the organization of the thesis and the levels of analysis

p. 10

9

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank many people who have been supporting me during the two years of this master program and in the writing of this thesis. First, I would like to thank the professors in the program; I have gained a great amount of knowledge and I truly enjoyed all the discussions they made possible during the courses. I am very grateful to my supervisor, Malgosia, who have provided me with tremendous amount of professional and emotional support throughout the realization process of this thesis. I would like to thank my fellow students, colleagues in the program, I gained a lot from all the different perspectives and knowledge they all brought to the program. I would especially like to thank my supervision group and my Study Buddies – it has been great to work together, and these professional relationships are very special to me. I would also like to thank many others for their friendship during this program and hopefully, beyond it.

I would like to thank my Hungarian support group, and that they helped me so much in moving abroad. I would like to thank the feminist community, who have had a great influence on how I see the world for a very long time and taught me a lot about ethics. I would also like to thank my family, especially my mum, for always encouraging my curiosity. And I would like to thank Merel, Annica, Irini and Orsi for all the amazing critical discussions and emotional support during the thesis writing period. And of course, I would like to thank my dog, Zumi, whose unconditional love meant even more in the isolated times during the Covid19 pandemic.

10

Chapter 1 – Introduction

My main interest in education science have always been equity, inclusion, social justice, both on the systemic level and in pedagogical spaces. I have always thought of education as one of the main tools and places in society, which can lead to a more just world. Where with raising awareness, critical thinking and listening to others’ stories and experiences, students can reimagine the social structures, practices in their lives and communities, politics and more. Prior to this thesis, I was reading transnational feminist theories and they opened up new realms for how to view society and social inequalities. I have been interested in power relations, systemic processes that cause inequalities and I developed a new lens to analyse them. Transnational feminist scholars discuss how the intersectional lens on oppression and social justice is needed today to work towards a more just society, and many of them link this knowledge to education in ways that I find extremely important in educational research. Transnational feminist research also regards the position of the researcher as an important part in research, as our own experiences influence our biases and view on the world, therefore the knowledge and the “truth” about society. Which does not mean that the research is not reliable, more that the position must be made clear for the sake of transparency. Therefore, I included an introduction which explains my motivation to conduct this research.

During my studies and activist work I started investigating academic scholarship discussing poverty and encountered several scholars who are critical with the current economic system. Many claim, that for poverty to be eradicated the system has to change and apply different ideological approaches, than the one it operates by today. Additionally, I have always been interested in private international schools. On the one hand, because pedagogically they tend to be highly valued and are leading actors in diversity, human rights education, innovative pedagogical methods; on the other hand because they are accessible for usually only a small group in society due to their fees; and privatization of education is a widely debated topic when it comes to its effects to equality. After some research, I also found that Nord Anglia Education, which is a successful international education company is in close cooperation with the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and they implement Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) materials. I have also

11

investigated the SDGs before, and since they are a very important part of international educational processes, I have always been motivated to explore them more.

During this master program, the in-depth investigation of topics such as international schools, morality of education, neoliberalism and intersectionality have been an important part of my learning process. Intersectional, transnational feminism offers great knowledge, way of thinking, pedagogical and methodological tools, and a mindset that can bring researchers to discuss educational issues in a way that can induce transformational social change. Furthermore, I read the master thesis from our program Problematizing the Peace Discourse in World’s Largest Lesson A critical exploration of knowledge production through discussions of violence of Maggie O’Neill (2019) which I found very inspirational and valuable to educational research.

With all these considered, in this thesis I seek to connect transnational feminist theory to the international and comparative education field and education about poverty and social justice. This study seeks to critically explore knowledge produced about these issues by SDG materials, and compare it to the context of Nord Anglia with a transnational feminist lens. The map below is a visual representation of the realms and topics explored in the thesis (Figure 1).

12

1.1 Background of the study

1.1.1 Equity in education and education for all

The world economy has been greatly altered since the 1970s, under the phenomenon which is often referred to as globalization. The world economy became a competitive space, “creating winners and losers” (Dervis, 2007, as cited in Zajda, Davies & Majhanovich., 2008, p. 3). The most important mission is to make globalization more inclusive, to reduce inequalities and to address social issues (Dervis, 2007, as cited in Zajda et al., 2008). Education has been assigned the role to work against inequalities and contribute to a more just society. The main role of education in today’s society is to improve the economic and social opportunities and prospects of individuals, which can be achieved by providing quality education for all (Zajda et al., 2008).

However, social and economic inequalities affect education in a variety of dimensions. Zajda et al. (2008) name seven dimensions of educational inequalities: individual differences in capacities; socio-economic status (SES) based on class inequalities and social background (education of the parents, income and cultural capital); family values and approach to education and material resources provided by families for studying; “the schools as a reproductive source of educational inequality; the education system that mirrors the structure of social society and reproduces existing class structure (i.e. school accessibility and school segregation); gender inequality; inequalities related to ethnic discrimination (p. 6).

The social and economic system mentioned above is described under many names: globalization, neoliberal capitalism, market economy. I will further elaborate on the definition I implement later in the thesis. However, structural changes in education in the past forty years are mainly the result of privatisation and marketization, and “quality/efficiency driven reforms around the world” (Zajda et al., 2008, p. 3). The effects of school choice and privatisation of education are widely debated. School choice is often framed as an opportunity for the poor to be able to access better quality education, however, they are the least likely to benefit from privatization processes (Verger, Fontdevila & Zancajo, 2016). Inequalities in education are due to these processes and funds for schools are not equally available, which has a negative effect on the quality of education (Zajda, 2018).

At the same time, education has been thought to be the tool for social mobility. Education is expected to be able to even out inequalities; it is expected to provide the same

13

educational opportunities for all regardless of their SES, gender or family background (OECD, 2018). Educational outcomes then would not depend on aspects that students have no control over (OECD, 2018).

However, research shows that no education system has been able to eliminate the effect of socio-economic inequalities in education (OECD, 2018). Countries, where economic inequality is lower, have been doing better in supporting social mobility, and those with higher level of economic inequality have been struggling more (OECD, 2018). At the same time, economic inequality between groups have been increasing: the economic inequality among OECD countries is at the highest level today since the 1980s (OECD, 2018) This urges equity in education even more (OECD, 2018). This data provided strong motivation for my study. If economic inequalities are growing, which is traceable on educational achievements, it is important to critically explore the systemic context of where the gap between groups is widening. Furthermore, if education has an essential role in tackling poverty and differences due to SES, it is important to investigate and evaluate educational actors. This study seeks to investigate the reproductive role of education: how education mirrors the current social system; and whether with educational materials it can question the current hegemonic status quo in order to strive for a more just social system.

Culture and education are closely intertwined, and they mutually affect each other. Culture is an abstract word, therefore challenging to define. In comparative education, it is common to define culture along the line of anthropological definitions (Marshall, 2014). Hofstede (2010) refers to culture as a “mental software” which influences how people behave, think and feel; and that the programming of this software is the social environment, family, social group and schooling (as cited in Marshall, 2014, p. 47). Education has a key role in conveying values and norms of a particular culture; and the decision on what is taught in education are based on values and ideologies (Bartlett & Burton, 2012, as cited in Marshall, 2014). The ideologies that form education and what values are conveyed in education appear on many levels of schooling, but the most obvious one is the curriculum (Joseph, 2010, as cited in Marshall, 2014). Beliefs about what knowledge should be taught in schools is embodied in the curriculum (Schiro, 2013, p. 2, as cited in Marshall). Therefore, investigating the knowledge produced by curriculum on social justice and equality is an important aspect of evaluating the role education plays in social change.

The role of education in improving the world is a widely accepted notion. Equality and equity and fair chance for all to improve their lives is “the heart of democratic political and economic institutions” (OECD, 2018). The ethics of education are also widely discussed

14

in moral philosophy. Kant claimed that both ethics and human rights are universal (Kant, 2017). Thomas Pogge (2008) sees the fulfilment of human rights as the requirement for a just world; and claims that institutions are moral actors, that constitute the constant world order and have moral responsibility in which direction the order takes (Pogge, 2010). In the following part, I draw on his idea on human rights and social justice, which provides the core theoretical approach for this thesis: that education has moral responsibility and should strive for social justice.

1.1.2 Human rights and social justice

Pogge argues that a “complex and internationally acceptable core criterion of basic justice” can be “formulated (…) in the language of human rights” (Pogge, 2008, p. 50). He discusses human rights as “claims on coercive social institution” and “claims against those who uphold such institutions” (Pogge, 2008, p. 50). He claims, that each human life has personal and ethical value; and that human rights are fulfilled if everyone can lead a life that is “worthwhile”. He calls this “human flourishing”, which builds on the two notions of having both a personal and an ethical value to life. Furthermore, Pogge argues that flourishing has different aspects to it; and it is for each person to decide where they put their emphasis to lead a worthwhile life; each person should have autonomy of their own lives. He defines autonomy as the “purpose of one’s own” – it does not connect to self-legislation or people developing their own values, it is more about that people can autonomously develop a purpose for their own life, which is both personally and ethically valuable (Pogge, 2008, p. 37).

Pogge (2008) argues that social justice and human flourishing are closely linked together. Social justice is the “equitable treatment of persons and groups”; and it is used to morally assess social institutions (p. 37). By social systems, Pogge (2008) understands “social system’s practices”, “which govern interactions among individual and collective agents as well as their access to material resources” (p. 37). These institutions “define and regulate property, the division of labour, (…), as well as political and economic competition” (Pogge, 2008, p. 37). For the moral assessment of these institutions, a “criterion of justice” has to be created, which evaluates whether the system treats the people within in a morally appropriate way. The measure of human flourishing is an important aspect in this assessment (Pogge, 2008).

Pogge (2008) argues that the in the interconnected world, a holistic understanding is needed; “the living conditions of persons are shaped through the interplay of various

15

institutional regimes, which influence one another and intermingle in their effects” (p. 39). He argues that the effects of the global institutional order and that in that criterion of justice must operate by the wider meaning of autonomy: that one can choose their own way of life as a way to human flourishing (Pogge, 2008).

What is needed for human flourishing, therefore the realization of human rights? Pogge (2008) discusses two essentialities: “the liberty of conscience, such as freedom of access to informational media” (p. 54); and access to “basic goods’, such as food and drink, shelter, clothing and healthcare, basic education, freedom of movement and action and economic participation (p. 54). He argues, that since many groups are deprived of access to these goods, the realization of human rights has not been achieved yet (Pogge, 2008). He claims that poverty deprives people from their basic human rights and that it is due to the operation of the global institutional world order (Pogge, 2010). Therefore, he claims that the eradication of poverty is the priority moral task in today’s society, and that institutions are morally responsible actors in it (Pogge, 2010).

Connecting Pogge’s definition on social justice and the role of institutions in the moral order provided this study with the motivation to investigate the relation between education and poverty. More specifically, the reproductive role of education in the current world order is conceptualized, and knowledge produced about poverty in international curricula is critically explored.

Furthermore, my choice of curricula and educational context is also motivated by moral aspects. Pogge (2010) argues that in the hierarchal, interconnected world, those who have more power, also have more responsibility. This notion also has great importance in feminist theory. MacKinnon and Dworkin (1988) argue that in the current world order, marginalized groups are made to seem and are thought to be responsible for their own marginalization, and power relations are made invisible; which makes the responsibility of those in power also invisible. They furthermore claim, that for a more just world order, the responsibility of those with bigger power has to be made visible; and that the goal is a more equal distribution of rights; for which the ruling groups need to have less power (or no power) over other groups (MacKinnon and Dworkin, 1988). These views motivated my choice in the educational materials and educational context: I chose to investigate a leading educational company (Nord Anglia) and education material produced by an influential transnational institution (the UN). I argue that they have great power in knowledge production and discourses on the social order and society, which also influences the

16

organization of the world order. Hence, by the critical investigation of the knowledge and discourse they produce, they can be held accountable in their morally responsible roles.

1.1.3 International schools

The era of modern international schools started in 1924 with the foundation of the International School of Geneva and Yokohama International School (Hayden & Thompson, 2016). The number of international schools have been growing, especially rapidly since 2000 and according to the International School Consultancy (ISC) there are about 5.6 million students studying in about 11, 600 international schools today, and the international school market generates 54.8-billion-dollar annual income (ISC, 2020). The initial purpose of international schools, until around 2000, was to educate children of globally mobile expatriates, sometimes with an explicit ideology promoting global mobility and citizenship (Hayden & Thompson, 2016). However, since the beginning of the century the ratio of host country nationals and foreign students have changed, and by 2016 80% of the international schools’ students are nationals of the host country (Hayden & Thompson, 2016). International schooling has become a commodity, offering innovative knowledge and global mindedness, and the schools have also placed their focus on attracting host country students (Hayden & Thompson, 2016).

In the meantime, privatization and marketization has also had a great impact on the landscape of education (Koinzer, Nikolai & Waldow, 2017). Market instruments have been growingly present in the governance of schools, and market mechanisms have appeared in the landscape of education with the promotion of school choice, and the expansion of private schools which are less influenced by the state and more affected by parents as consumers (Koinzer et al., 2017). The privatization of schooling has affected equality and social segregation. Those in favour of school choice argue that free choice grants the right to parents to provide their children with the best education, and also enable disadvantaged students to choose between schools and improve their education (Koinzer et al., 2017). However, others argue that school choice further advances the privileged and widens the gap between social groups, while also changing the notion that education is a “public good” (Koinzer et al., 2017).

This study takes Nord Anglia Education, a private, international education company as the context of the study. This company is a successful education business with private

17

schools all over the world, which claims to be strongly committed to educate students concerning social inequalities.

1.1.4 Nord Anglia Education

Nord Anglia Education is an educational company founded in 1972 by Kevin McNeany. He is an entrepreneur in the educational sector, he founded another international educational company, Orbital education in 2005, in which year he also stepped down from Nord Anglia (Wikipedia, 2020). Nord Anglia company is an outstandingly successful business: it is the only education company that gained a full listing in the London Stock Exchange1. In 2008, the company was bought by Baring Private Equity Asia for £190

million, and it was privatized in the stock market (Business Live, 2013). Their head office is located in London, UK, and their global HQ is located in Lam Tin, Hong Kong, which is also the place for all legal and business aspects of the company.

This thesis does not attempt to conduct a network analysis on Nord Anglia, nor does it go in depth on the business features of the company. However, since this study has a critical approach with an emphasized focus on economic aspects of society, it is important to note that Nord Anglia has an important role in the education business. That being said, the company’s main purpose is profit-making, which requires constant expansion of schools and the school network. The fact, that an educational institution’s main purpose is to bring profit, raises the question of whether it can fulfil moral responsibilities discussed in the theoretical and conceptual framework of this study. In the following part, I focus on the image of the company as an educational entity, their vision of the world they are educating children for and their approach towards education itself. Nord Anglia serves as the context for the curricula analysed in this thesis, and their vision will be discussed in the Discussion (Chapter 6) part.

1.1.4.1 The vision of Nord Anglia

Nord Anglia offers ”premium” education to their students. They promise personalised learning for every child to ”achieve what they never thought to be possible”. Their main slogan is ”be ambitious” and their philosophy consists of the following: there is no limit what the children can achieve, and they nurture ”relentless optimism” and confidence. According to their vision, children can achieve anything with passion, determination and an innovative

18

mindset. They also promise to educate children to be creative and to have a ”vision to change the world”.

Nord Anglia promises ”the best” for children and an education carried out by world-class teachers. The website states that one in three students from Nord Anglia schools gets enrolled in one the best hundred universities in the world. They promise for children to gain ”access to opportunities beyond the ordinary”. According to their website, Nord Anglia schools provide an education for the future and prepares students to embrace ”tomorrow’s opportunities” so that children can ”take advantage of emerging career paths”.

As mentioned before, Nord Anglia nurtures global mindedness, and they claim that “tomorrow’s leaders need a global mindset”. They promise a diverse, international learning community. All schools have a unified vision and the main curricula are the same for all schools (for example the English National Curriculum and the International Baccalaureate), but all schools adjust to their host countries in different way. They nurture global mindedness, with their Global Campus platform students can connect with their peers all across the different schools and they are encouraged to learn together and from each other.

Nord Anglia also supports students in ”making the world a better place” as they state that it is ”a dream many would like to accomplish one day”. Their education focuses on supporting the social consciousness of the students and encourages them to care ”more deeply about the world”. They offer outstanding opportunities for their students to connect with organizations such as the United Nations (UN) and the UNICEF. The Annual Global Challenge event is organized in cooperation with the UNICEF and is about raising awareness to the SDGs and social issues, for example ”fighting against poverty”. Student ambassadors of Nord Anglia schools are invited to global summits with the UN and UNICEF organized at the headquarters of the UN in New York, where they can take part in seminars and gain close experience of policy making processes.

1.1.4.2 Nord Anglia’s target group and tuition fees

Nord Anglia has 66 premium day and boarding schools, in 29 different countries in the Americas, Europe, and in Asia. All schools are private schools, their fees are adjusted to the countries and their annual prices in Europe for secondary education students range between 10000-32000 EUR (Appendix 3). Due to their fees and the lack of scholarship, they cater only for those, who can afford the fees. Discount is offered if more siblings are enrolled at the school. Nord Anglia puts a strong emphasis on nurturing an international, global community, and this is shown in their transfer policy as well, which attempts to help families relocating

19

have a smooth transfer process. Priority in admissions is given to those transferring between schools and their bureaucratic processes between schools are handled by the staff and not the parents.

1.1.5 SDG education and the World’s Largest Lesson

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was adopted by all UN member states in 2015, and its main aim is to end extreme poverty, to fight inequality and injustice and to tackle climate change (World’s Largest Lesson, n.d.). The agenda is discussed in the 17 SDGs, and they call for action by all countries in a global cooperation (UN, n.d.). I apply the SDG education here as a common concept for different ways how Nord Anglia is involved in education for the SDGs, in cooperation with the UNICEF. Nord Anglia organizes a Model United Nations (MUN) event each year. MUN is a simulation, where students play out UN committees and summits; they usually take place in the form of a conference, where students prepare themselves to debate and discuss different social issues (Best Delegate, 2007). It is an extra-curricular activity, and students engage in research, presentation, public speaking, debates, and they can improve their writing skills, critical thinking, leadership skills and cooperative skills.

Furthermore, Nord Anglia claims that their teachers use materials from the World’s Largest Lesson to educate students about the SDGs. The World’s Largest Lesson was launched in 2015 by Project Everyone. Project Everyone is a communications agency, with a mission to contribute to a fairer world by 2030. They are in close collaboration with the UNICEF, just as the World’s Largest Lesson. Although I do not conduct a network analysis on the World’s Largest Lesson, it is interesting to note that among the leading partners of Project Everyone is the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Google, and Mastercard, which are all among (or associated with) with the most successful businesses in the world. The presence of large businesses further complicates the discourse on social justice and eradication of poverty that is created: the endorsement by businesses that are successful within the neoliberal, capitalist system might imply that their interest of wealth accumulation influences their effect on knowledge production

.

1.2 The aim of the study, objectives and research questions

1.2.1 The aim of the study

20

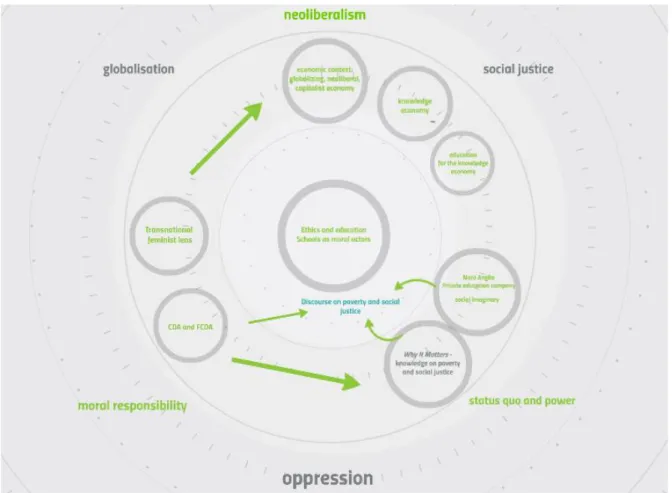

The aim of the study is to critically explore the discourse on poverty and social justice created by the knowledge production of international curricula and the educational context of an international school company. More specifically, the knowledge produced about poverty and social justice in the Why It Matters materials is investigated and further interpreted by being compared to the social imaginary of Nord Anglia. I argue that the knowledge produced by the materials and the social imaginary of their educational context together create a discourse on poverty and social justice. The education materials are critically explored following the methodology of critical discourse analysis (CDA) and feminist discourse analysis (FCDA), and the knowledge produced about poverty and social justice is discussed through a transnational feminist lens. Furthermore, the knowledge is compared to the social imaginary of Nord Anglia; and the discourse they create together is discussed with reflections on how they contribute to the realization of a more just society or how they maintain the current hegemonic status quo. As the position of this study claims that educational institutions have moral responsibility, implications with regards to morality are also discussed. The map below is the visualisation of the aim of this study and the comparison (Figure 2).

21

1.2.1 Objectives

In order to fulfil the aim of this study, I set the following objectives for the process of the study.

For studying the context and the background of the materials • to explore the social imaginary of Nord Anglia

o by investigating their educational vision o by exploring what they offer for students

o by examining their target group (who they cater for) For the analysis

• to explore the knowledge the SDG educational materials – Why It Matters? information sheets produce about poverty and social justice

o by exploring the context of poverty provided in the materials

o by mapping the solutions promoted to eradicate poverty and to work towards social justice

o by investigating the reasons named by the materials for why poverty should be eradicated

• to compare the knowledge produced by the materials to the social imaginary of Nord Anglia

1.2.2 Research questions

• What knowledge is produced about poverty and social justice by the Why It Matters materials?

• How does this knowledge relate to the social imaginary of Nord Anglia?

• What discourse is created by the knowledge production of the Why It Matters materials when compared to the social imaginary of Nord Anglia?

22

1.4 Relevance of the study to the field of international and

comparative education

This thesis seeks to contribute to the field of international and comparative education field by critically investigating international curricula regarding poverty and social justice. The context of the curricula analysed here is an international school company, and the curricula is endorsed by transnational agencies (UNICEF, UNESCO). The analysis and evaluation of education is an important task in the field of international and comparative education, especially in the globalizing world (Zajda, 2018). Investigating the effects of globalization and internationalization on education is the scope of many studies, research and theories in the field of international and comparative education (Marshall, 2014). This thesis seeks to both conceptualize globalization and the economic system and investigate how it influences educational discourse.

Furthermore, the UN SDGs receive international attention, and were adopted by all the member states of the UN. The UNICEF and the UNESCO are influential transnational organizations with a major focus on education. Official materials of the World’s Largest Lesson and the Model United Nations (MUN) step over country borders; they are produced for international educational purposes and implemented by many countries and many educational institutions (World’s Largest Lesson, n.d.). Furthermore, comparative studies in education serve the purpose of understanding the relationship between the society and education, and “to promote international understanding” (Marshall, 2014, p. 7).

Additionally, this thesis applies a transnational feminist theoretical framework. The goal of transnational feminism is to make the world a more just place for everyone; transnational feminism is actively working against discrimination between social groups on the global scale (Arruzza et al., 2019). I argue that transnational feminist theory provides a comprehensive understanding of the global world, and a valuable tool to analyse educational practices and discourses. I seek to contribute to the field of international and comparative education by conducting a research with transnational feminist lens.

23

Chapter 2: Conceptual and theoretical framework

2.1 Globalization and poverty

Globalization is a very broadly defined, theorized and researched phenomenon. In this section, I attempt to present some definitions of globalization and the global economy, to outline the social and economic context where the analysis of educational materials is embedded in. Then, I line up some aspects of critique towards the current tendencies of globalization from different critical scholars. My approach towards globalization is in line with many critical theorists, viewing it as a phenomenon that is actively and continuously created, which is different from the common notion according to which it is an organically happening and inevitable process. The discourse on globalization often justifies unjust economic activities and hierarchies2 in society, which I treat as problematic in this paper. The definitions and approaches presented here all address the organization of power in our globalized society. Which also means these approaches admit that globalization and the organization of the world is directed by different power holders and therefore can be changed.

2.1.1 What is globalization?

It is challenging to put together a comprehensive definition and to find a focus when discussing globalization. In this section, I summarize those definitions that best represent the above described problem in conceptualizing globalization.

Globalization is the process of the quickening and expanding interconnectedness in all areas of life, such as culture, economy, social life, while also the “organization and exercise of power on a global scale” (Held, 2004, p. 15). Economic, political and cultural decisions are crossing nation-state borders, and individual decisions can have a much broader effect than ever. Due to technological and communicational developments, people can get connected much more easily regardless of their geographical locations. The flow of news from all over the world is intensified and much more accessible (Held, 2004, p. 15). The cultural aspect of globalization brings major changes in people’s identities and self-conceptions and in the realms of human interactions (Papastephanou, 2005, p. 534).

2 For example it is a common notion that poor people are poor because they are not working hard enough, because they make bad decisions, and they could easily turn around their economic situation if they just tried harder. This is the argument of many neoliberal politicians as well, Margaret Thatcher called poverty a „personal defect” (Bregman, 2016).

24

With globalization, decision-making processes have also significantly changed. This interconnected world is regulated by a global institutional infrastructure. International organizations have replaced the nation-states in many aspects of social, political and economic decision-making, policy creation and executive duties. The United Nations (UN) and its agencies take up political and social roles in many countries. Global economy and finances are governed by the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and global trade is in the hands of the World Trade Organization (WTO) (Held, 2014, p. 17). In many cases these organizations are viewed as international entities that are beyond the interest of nation-states. However, the current order was mainly created, and it is still mainly ruled by the more powerful developed countries, especially the G7 countries3. The global institutional infrastructure is modelled and arranged in a way that it serves the interest of these countries’ domestic business and finance elites, while dismissing the interests of the poor and the vulnerable, especially of less developed countries (Pogge, 2010, p. 22). This point is further discussed later in this chapter.

The main focus of this thesis is the role of educational institutions as actors to fight against poverty and economic inequality in the globalizing world. The current system of globalization cannot be described without shedding light on economic processes and discussing globalization alongside neoliberalism and capitalism. I do not argue that globalisation in itself is a negative imaginary. This work is however rejecting the current neoliberal capitalist economy and argues that social justice and equality cannot be achieved in the current dominant system. This thesis attempts to conceptualise neoliberalism and the capitalist economy with through a critical lens and deconstruct the discourse on social justice embedded in these realms. This also serves as the conceptual and theoretical backbone for the analysis of this study, which investigates the role of education in the current system and the discourse on poverty and social justice in educational materials.

2.1.2 The global economy

In order to achieve the aim of this research, it is essential to investigate the economic aspects of the globalizing society. Every aspect of our life is intertwined with economy, and since the focus of this research is the knowledge production about poverty and social justice,

3 G7 is the term for the Group of Seven, which consists of the world’s seven largest economies and most industrialized nations. These countries have more than 62% of the global net wealth. The group was formed in 1975 and they hold a meeting every year. The group consists of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United Stated of America.

25

it is of crucial importance to establish the economic context in which modern poverty takes place.

The current economic system is a global, neoliberal, capitalist market economy. In this section I define all these concepts and attempt to develop a comprehensive description of the economic context.

The essence of a capitalist market economy is that “production is in the hands of private individuals and firms” and that the market is a free market (Mueller, 2012, p. 1). The other core feature is that the state does not interfere with the processes of the market, e.g. prices or the flow of finance. In other words, capitalism is an “exchange-value system, in which the means of production are privately owned, controlled and characterized by competition and the profit motive” (Naglieri, 2010, p. 158). The modern capitalist market economy consists of different institutions that together operate the economy (and society) - private ownership, competition, banks, corporations, and property rights and the judicial institutions that enforce these rights (Mueller, 2012, p. 2).

Neoliberalism is the policy agenda of the Western countries underlying and directing the capitalist practices and global economic processes since the 1970’s (Olssen, 2004, p. 231). It is a major obstacle to democracy, as it eliminated social regulation and it hinders policy initiatives in areas which could regulate the concentration of power and capital, e.g. policies to protect the jobs and wages of the lowest paid groups, to preserve stability in financial areas and public services (that the market cannot ensure), and the expansion of public education and health care (Olssen, 2004, p. 231). Neoliberalism is the ideology that spread the view that the only way for globalisation is focusing on economic growth, wealth accumulation and to do it without government regulations (Olssen, 2004). Neoliberalism sets an increasingly narrowing economic and social vision: one that operates by competitive individualism and is sustained by policy reforms and subtle discourse changes that shift the focus to individual interest and that reformulate the language around social justice as well (Roberts & Peters, 2008, p. 1). Neoliberalism claims that individuals have individual responsibility, that the key to success is education, and that with economic growth, eventually everyone will get out of poverty.

Lingard also defines neoliberalism as the ideology leading globalisation as we know it. An ideology which prioritizes markets over the state and regulation and emphasises the interest of individuals rather than the collective. He argues that the individualism of neoliberalism deems people „responsible for their own ’self-capitalising’ over their lifetimes” (Lingard, 2009, p. 18 as cited in Ball, 2012).

26

As mentioned earlier, globalization influences all areas of life. Carnoy and Rhoten argue (2002) that globalization reorganizes the world economy. However, it is important to note that the world-wide expansion of the capitalist economy is the core drive in globalising processes, it is not just one part of globalization but it is its driving force; and the institutions governing the economy are actors contributing to and forming these processes. Naglieri discusses the global capitalist market economy as market imperialism according to Naglieri, following Marxist traditions (Naglieri, 2010). Market imperialism’s main demand is to have a global economic uniformity, a world without borders, where the marketplace can invade all areas of life. In the current global economic order, the ultimate goal is the accumulation of wealth, which has shifted nation-states’ priority to integrate into the global economic processes, by demonstrating economic growth (Kazamias, 2009a, p. 1089). Capitalism is staged as the only possibly global economic currency, which provides corporations and more powerful countries to access the whole population as potential customers, retailers, laborers or capitalists (Naglieri, 2010, p. 158). It is imperialism in a sense, that the main beneficiaries and the controlling forces of the economic system are developed, Western countries (high income countries in Europe and the United States), where the institutions governing capitalism (IMF, World Bank, WTO) are located. Most of the biggest corporations are also based in these countries, and they have the financial and political influence to dominate international markets. Market imperialism maintains Western hegemony through multinational corporations across the globe and ensure influence on unstable, developing countries’ governments through these corporations (Naglieri, 2010, p. 58). There is a common illusion that capitalism looks differently all over the world and that it is more just in some places than others – which is true to some extent but needs further elaboration. Naglieri (2010) argues that “capitalism has become the universal economic system”, and the only way to join the global marketplace is by accepting its rules, which goes against the common belief that the economic system accommodates to the local contexts and that nation-state governments can have their own economic regulations; rather the economic map becomes quite homogenous (p. 58). But this homogeneity does not bring global equality, as it is often believed. Quite the opposite.

It is indeed true that capitalism has different faces on different parts of the world and for different groups of society, but it is not because capitalism in itself is diverse or because it would accommodate to cultural or social differences. It is because capitalism is inherently hierarchical. Market imperialism renders parts of the world and nations into different roles in the global economy, and globalization reinforces already existing power relations and

27

patterns of domination. Bauman (1998) refers to the current world order as glocalization, arguing that for more privileged groups it is indeed globalization in a sense of gaining possibilities, but for the less privileged it is localization, meaning that their social position is more fixed than ever before. The ongoing global processes are mainly about the redistribution of privileges and deprivations, of wealth and poverty, of power dynamics and of freedom and oppression. It is a world-wide process, which creates a “world-wide socio/cultural self-reproducing hierarchy”, since the roles and the diversity the globalized market and culture offers are not making all participants equal partners (Bauman, 1998, p. 43). If anything, the gap between the groups is becoming bigger; glocalizing processes are about concentration of capital, resources and the freedom to act. The gap between the poor and the rich is becoming bigger in capital but also in their relationship: the mutual dependency between the rich and the poor, although still existing, became far more distant, and the poor are out of sight for the rich (Bauman, 1998, p. 44). At the same time, while mobility for the privileged has been growing, for the underprivileged, geographical, but even more so existential mobility is a lot less accessible objective (Habermas, 1998, as cited in Papasthepanou, 2005, p. 537). The international and comparative education field has a crucial role to investigate the different appearances of capitalism, oppression and economic differences, through comparison between countries, places and education systems.

Another important economic aspect is that as a consequence to nation-states having lost their influence on economic processes in the global economy, inequality in the distribution of wealth and income has escalated rapidly in the past few decades4 (Olssen,

2004). On the free market, where supposedly everyone has free choice, richer countries developed a lot quicker than poorer countries (Olssen, 2004), since free choice in the capitalist economy is bound to money, therefore those who have more money have more opportunities. One of the objectives in the global market is to eventually integrate different groups of the society, but at different times in the global economy and accumulation process (Olmos & Torres, 2009). However, the time difference makes the inequalities bigger, and brings up the question who gets to decide who can be integrated.

4 The richest people in the world, 2153 people had more wealth than 4.6 billion of the poorest people together. The combined wealth of the 22 richest men in the world is more than the wealth of all the women in Africa (Oxfam, 2019). https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/620928/bp-time-to-care-inequality-200120-en.pdf

28

2.1.3 Poverty in the global, neoliberal, capitalist world order

Poverty is present and talked about all over the world. It is one of the greatest problems society struggles with and has been one of the greatest issue humanitarian organizations have attempted to solve. However, there are different discourses going on about poverty and there is plenty taken-for-granted knowledge about it in general. I problematize the mainstream discourse on poverty, which serves as the theoretical framework, which seeks to critically explore knowledge about poverty and social justice in education.

The general discourse on poverty is most often concerned with poverty as a phenomenon, an abstract problem without mentioning what causes poverty, nonetheless who is responsible for it. Poverty is an abstract concept and often made to seem as a neutral problem. Quite often the discourse around poverty implies that poverty is something that naturally exist, which is something that we should tackle. Furthermore, it is often talked about as something that is the fault of poor individuals because they are lacking the ambition, or the skills, not to be poor (Bregman, 2016). I conceptualize poverty as an actively created and maintained status and economic situation for groups in our society, and as a phenomenon that can only be fully understood when the relations and dynamics of the economic system as a whole are mapped. I will treat poverty as a phenomenon that is needed to be maintained in a capitalist market economy for other groups’ maximized interest. In this section I define how I view poverty for this study drawing mainly on Thomas Pogge’s (2008, 2010, 2016) work, who views poverty as a crime against massive groups of society, and the result of actively maintained violations of human rights. This is an important theoretical stance in this study, which views educational institutions as moral actors in achieving social justice, therefore it claims that educating for the eradication of poverty is among the moral responsibilities of these institutions. Additionally, since economic inequalities are expected to be balanced out in education, it is crucial to understand the economic and social context which produces the inequalities.

2.1.3.1 “Poverty is foreseeable and avoidable”

Already in the 1970s, the question of the enlarged moral responsibility of governments, corporations and individuals was raised (Pogge, 2010). It was also around this time, when the recognition of poverty as “the greatest source of avoidable human misery” came about, since much more people have died from hunger and curable diseases since the

29

end of the Cold War, than deceased due to wars or repressive government systems over the 20th century (Pogge, 2010, p. 11). Poverty is persistent; the number of people undernourished

in 2018 was 811.7 million (the number has been growing since 2015 when it was 785.4 million, and is predicted to grow further) (FAO, 2018). Around 844 million people do not have access to safe drinking water (UN, 2019, p. 4.). Around 2.3 billion people do not have access to a basic sanitation service (WHO/UNICEF, 2017 as cited in UN, 2019). Nearly 2 billion people lack access to basic medication (WHO, 2020), and 773 million people are illiterate, most of whom are women (UNESCO, 2020). 218 million children are in child labour (ILO, 2020). People of colour, women, and very young children are overrepresented among the global poor (Pogge, 2010).

The eradication of poverty has been in the main focus of debates around development for decades now. Despite the mass mobilization of institutional and material resources, the results have been moderate and poverty permits. It remains a structural feature in our societies, while the income and wealth disparities have been visibly growing. High and middle-income countries have experienced an accumulation of wealth that they have never before (however, marginalized groups in these countries might not have experienced much of it), but at the same time the majority of the world population suffers from continuous deprivation, for example from extreme poverty and hunger (Cimadamore, Koehler & Pogge, 2016, p. 11).

The human rights of people in poverty are harmed, which also harms their ability to practice their civil rights and duties. Malnutrition, illiteracy and the lack of schooling impede big groups of people from engaging in political and civil action, to contribute to the civil and political happenings and actively exercises their political rights. At the same time, this makes it easier for rulers and politicians to attend to the interests of those with bigger capacity, e.g. foreign individuals with capital, corporations and foreign governments (Pogge, 2010, p. 12). In other words, poverty itself harms human rights and makes it further possible for groups with capability and power to oppress and exploit groups living in poverty.

2.1.3.2 Poverty and moral responsibility – global justice

The inclusion of the ethical dimension when discussing the economic system and poverty, as well as the role of education, is providing the backbone of this thesis. According to Papastephanou (2012) questions to be asked when analysing globalization and the impacts

30

of the current world order from a deontological5 point of view, are about asking who benefits

from this economic system? What does globalization mean for the nature? For marginalized groups? How do the current system and discourse affect social justice and equality? What happens to diversity? (Papastephanou, 2012, p. 48). The idea of economic growth and wealth accumulation are investigated alongside these questions.

Modern poverty exists and grows within the current design of the global institutional order. As mentioned earlier, it is the G7 countries and those global organizations that largely influence global economy (IMF), global trade (WTO), currency (World Bank), whose interests most effectively shape and dictate the current world order (Pogge, 2010). The institutions operating the global economy apply neoliberal policy agenda focusing on economic growth and wealth accumulation (Pogge, 2010). It is, however, difficult to find responsible agents, and no individual can be held fully responsible. However, since citizens, company leaders, businessmen of these more powerful and fairly democratic countries, and so many individuals themselves benefit and at the same time maintain the current world order, they can be somehow held responsible, to different extent (Pogge, 2010, p. 22). This connects back to Pogge’s definition of human rights, as claims on institutions and those who maintain the institutions (see Chapter 1). Educational institutions are part of the social system, therefore can be morally investigated as well, for example with critically exploring knowledge production and their actions regarding social justice. This thesis focuses on the discourse on poverty and social justice that is created by educational materials and the social imaginary of educational actors.

It is essential to critique the idea of the free market or free competition, which claims that everyone is provided with the same opportunities, therefore everyone could make their own fortune. This is the idea behind including more and more countries in the global free market and claiming that once they are included, equality will be more achievable. However, as mentioned earlier, different countries and social groups start off with different capital which limits or extends their pool of choices. In this logic, everyone has a legal right to actively participate in the global capitalist order, and if they fail to do so, they failed in the competition of individuals and therefore are not worthy of the system’s privileges – poverty becomes an individual failure (Bregman, 2016). In achieving social justice, moral responsibility should be attached to those with bigger power. One can argue that governments exist to represent and promote the interests of their nation’s people, therefore it is appropriate

5 The deontological view refers to the ethics of relationality extended to the whole world (Papastephanou, 2012). Deontology holds ethics as universal moral that has laws (Ethics Unwrapped, 2013).

31

for them to shape the global institutional order in a way which benefits their people (Pogge, 2010). Furthermore, it is also an adequate argument that governments have to be partial and concentrate on their own people’s interest. Pogge (2010), however argues that partiality is only permitted in the context of fair play, fair competition. Partiality exists only on the condition of fairness, therefore all actors’ should be committed to preserve the fairness of the whole social setting, in order to be able to maintain their partiality (Pogge, 2010). In other words, it is essential to apply an ethical lens to economic and political actions and fairness should be always the key foundation.

2.1.4 Intersectionality and the global world order

Intersectionality can be defined and conceptualized in several ways, and it is widely discussed whether it is a theory a methodology or an analytical tool. In this thesis, I apply intersectionality as a lens that is infused both with my theoretical framework and my analysis. The vantage point of intersectionality is that social division and inequalities are caused by power differences appearing between different groups of society. Furthermore, it views and analyses the world as a complex system of power relations and claims that oppression is caused by groups in power discriminating and exploiting other groups (Collins & Bilge, 2016). Oppression has a systemic virtue and operates along the line of differentiating groups in society and discriminating them based on these differences. Additionally, oppressive systems such as sexism, racism, classism, heterosexism are intertwined with each other (Collins & Bilge, 2016). Which means that people and groups who are part of more discriminated groups, suffer from the oppression of all oppressive systems together. The intersectional lens can be applied to view oppressive systems as a complex system, and to place social inequality in a framework that conducts an in-depth analysis on how oppression and exploitation operates (Collins & Bilge, 2016). The global social inequality has been growing especially rapidly with the expansion of the neoliberal ideology (Collins & Bilge, 2016). At the same time, power differences have been made invisible in the neoliberal realm, with the promotion of individualism and the notion of free, open market that is supposedly provides everyone with the same opportunities. Neoliberalism renders success and failure as consequence to individual choices and responsibility, which also implies that social inequalities are produced fairly, or they exist by nature (Collins & Bilge, 2016). The intersectional lens reveals the power structure and the systemic virtue of oppression, therefore can help us revise social practices and support action that can tackle oppression (Collins & Bilge, 2016).

32

2.1.5 The transnational feminist critique of capitalism and neoliberalism

2.1.5.1 Why a transnational feminist critical theory?

Transnational feminist theory recognizes the intersections of different oppressive systems (Crenshaw, 1991). It discusses capitalism and patriarchy as two systems that operate together in our society today. This thesis addresses these systems as oppressive systems, and I argue that the feminist lens gives a more in-depth analysis of the current world order. Furthermore, to have a thorough analysis of our society today and an approach towards social justice and poverty that is able to address problems on a systemic level, it is important to view capitalism and patriarchy as intertwined systems that implement oppression cooperatively, since as mentioned earlier, women suffer significantly more from poverty. I also argue that patriarchal oppression which oppresses women as a group, is a global problem, and takes place in all societies and in all parts of societies, only in different forms and to different extent6.

There are many different trends and directions in feminist theory. In this thesis I apply an intersectional transnational feminist lens, which analyzes power and power relations in oppression. Feminism is a mainstream ideology today, and many actors in the capitalist system have recognized the importance work towards gender equality to some extent. However, the mainstream media and many mainstream actions taken towards gender equality, have a liberal feminist approach which goes hand in hand with neoliberalism, and focuses on bringing equality to women in upper classes, for them to break the glass ceiling, and diversify the current hierarchal system, meaning for women to become corporate leaders next to men (Arruzza et al., 2019). Liberal feminism only helps privileged women to gain more power, by outsourcing oppression like caregiving and household chores to less privileged women. Liberal feminism is individualist and elitist, just as the neoliberal capitalist system that causes oppression and inequality in our society. Liberal feminism does not stand for the majority of women, but it disguises the same oppressive and hierarchical system to be “progressive” and “diverse” (Arruzza et al., 2019, p. 12).

The approach to feminism discussed here, on the contrary, is an intersectional, anti-capitalist and decolonial transnational feminism that critiques the patriarchal, neoliberal,

6 The wage and wealth gap between men and women persists globally in all racial groups and all classes. The unpaid care work is disproportionately done by women, even in those countries where the male participation is highest (Inequality.org, n.d.) Violence against women is a global phenomenon and it exists in all forms all over the world (rape, patnership violence, workplace violence) and it violates women’s rights and hinders equality in all areas of life (WHO, 2017).