0

What are the incentives behind

organisations’ usage of nudges in

sustainable marketing?

And is the dualistic definition of the term influencing how organisations apply

nudging?

BACHELOR THESIS WITHIN Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 hp

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Sustainable Enterprise Development

AUTHORS: Johanna Stenberg (970516), Alexandra Andersson (970206), Lovisa Nilsson

Eskesen (960411)

TUTOR: Thomas Cyron JÖNKÖPING May 2020

1

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: What are the incentives behind an organisations’ usage of nudges in sustainable marketing? And is the dualistic definition of the term influencing how organisations apply nudging?

Authors: Johanna Stenberg, Alexandra Andersson, Lovisa Nilsson Eskesen Tutor: Thomas Cyron

Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: Nudges, Sustainable marketing, Sustainable development

____________________________________________________________

ABSTRACT

Problem: Currently, there are two definitions of nudging, one that is connected to sustainable

development and another one that is not. This can create confusion for researchers and customers and could potentially lead to greenwashing when the incentive of the nudge does not match with the best outcome of the person being nudged.

Purpose: The purpose is to explore how organisations interpret nudging and how their underlying

incentives affect the use of nudging in practice.

Aim: This research aims to explore the incentives behind organisations use of nudging for sustainable

marketing in practice. The organisations incentives will be connected to any of the dualistic definitions of nudging in order to see which of the definitions that are aligned to practice.

Method: This research is a qualitative study and has been conducted under an interpretivist paradigm.

It has made use of semi-structured interviews to collect primary data, as well as newspaper articles and web sites to collect secondary data. To analyse the data, a general analytical procedure was used. The data was presented in a within-case analysis together with a cross-case analysis where the empirical data was compared with the theoretical framework to discuss and answer the research questions.

Result and Conclusions: The comparisons showed that three out of five organisations have the main

incentive of earning money from their nudge despite their sustainability agenda. Another finding was that only one organisation exclusively uses the definition of nudging that is connected to libertarian paternalism. These findings contribute to the literature and informs customers that nudges can be used for several purposes.

2

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank everyone that has participated in this study as representatives of the organisations. We are also very grateful for our tutor Thomas Cyron who has provided us with constructive and useful feedback throughout the process. Furthermore, we would like to express gratitude to the professors that sparked our interest in the topic of nudges and helped guide us in the beginning of the process.

3

Table of Content

1. Introduction 5

2. Theoretical Framework 7

2.1 From Income-Oriented to Sustainable Marketing 7

2.2 Nudging as a tool for sustainable marketing 9

2.2.1 An introduction to nudging 9

2.2.3 Libertarian Paternalism and a Technical Definition - Two Contradictory Definitions

12 2.2.4 Conclusion of chapter 13 3. Methodology 15 3.1 Research philosophy 15 3.2 Research approach 15 3.3 Research design 16

3.3.1 Multiple case study 16

3.3.3 Sampling of cases 16 3.3.5 Introduction of cases 19 3.4 Data collection 21 3.4.1 Semi-structured interviews 21 3.4.2 Secondary data 22 3.5 Data analysis 22 4. Empirical findings 24 4.1 Myrorna 24 4.2 Interface 26 4.3 Klimato 27 4.4 HSB 29

4.5 Göteborgs Stad (the city of Gothenburg) 31

5. Analysis & Discussion 33

5.1 Within-case Analysis 33 5.1.1 Myrorna 33 5.1.2 Interface 34 5.1.3 Klimato 35 5.1.4 HSB 36 5.1.5 City of Gothenburg 37 5.2 Cross-case analysis 38

4

5.2.1 Incentives 38

5.2.2 Dualistic definitions within organisations 39

5.2.3 Insecurity regarding what is a nudge and what is not 40

5.3 Future Research 40 5.4 Implications 41 5.5 Ethical issues 41 5.6 Limitations 41 6. Conclusions 43 7. List of References 44

Appendix 1: Criteria of Selection for Sustainable Organisations 48

Appendix 2: Interview Guide 49

5

1. Introduction

This section is a compilation of what the reader can expect to read further about in the thesis. It briefly introduces the concepts of marketing, sustainable marketing and nudging. The researchers will present the problematic aspects that a dualistic definition of nudging entails and explain the purpose of this thesis.

Figure 1: A nudge, elephant mother gently nudging her young calf (Nobelprize, 2018)

"Nudging was first described by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein in their groundbreaking book "Nudge". [...] To illustrate the act of nudging, they decided to use an elephant mother gently nudging her young calf in the right direction."

- MeBeSafe (2020)

Marketing has for long been focused on making organisation’s offerings attractive to its customers (Kotler, 2011; Jones et al., 2008), and have by some been seen as a practice to sell unnecessary things (Lim, 2016). As more people have become aware of the need for sustainable development, the changeable nature of marketing (Mela et al., 2013) has made it shift towards sustainable marketing (Foltean, 2019). Sustainability is an area that has become essential for organisations to consider in their business strategy if they want to remain relevant in today’s society. With the shift towards sustainable marketing, practitioners have met new challenges, such as changing consumer behaviour towards more sustainable choices.

The field of behavioural economics can provide tools that help to overcome this challenge, as it acknowledges that people's behaviour depends on more complex factors than traditional economic theory assumes (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008). One such tool that stems from the field of behavioural economics is nudging. The Nobel-prize winner Thaler and his companion

6 Sunstein coined the term nudging in 2008. Nudging concerns choice options and how to construct those in a preferable way (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008). One example of nudging is when a restaurant owner considers where to place the different types of food. If the owner wishes to encourage people to eat healthier, the healthiest choice would be placed where it is most accessible for the customers (ibid).

Through the concept of libertarian paternalism, Thaler and Sunstein (2008) connect nudging to the improvement of people's wellbeing. It is, however, uncertain if nudging is always related to societal benefits and sustainability because organisations can use nudging for several purposes with different incentives in mind (Hansen, 2016). For example, organisations that do not use nudging for sustainable marketing may use it for traditional marketing. This twofold application of nudging causes confusion for researchers investigating the subject, and also for customers. It can potentially lead to greenwashing when the incentive of the nudge does not match with the most sustainable outcome for the person being nudged.

The purpose of this research is, therefore, to explore how organisations have interpreted nudging and how their underlying incentives affect the use of nudging in practice. This purpose will be fulfilled by conducting a multiple case study, including five sustainable organisations that engage in sustainable marketing and using nudges. The research questions are, therefore: What are the incentives behind organisations´ usage of nudges in sustainable marketing? And is the dualistic definition of the term influencing how organisations apply nudging?

7

2. Theoretical Framework

This section presents the history and current reality of the marketing world. The researchers will make use of the existing literature on how societal changes has created a demand for sustainable marketing, but also the implications that arrive with its application. Furthermore, the researchers will describe the dualistic definition of nudging and how the creators of the term intended its use. The application of nudging in business and consequential ethical implications will also be covered. Finally, the researchers will introduce the four most commonly used types of nudges and how these are applied.

2.1 From Income-Oriented to Sustainable Marketing

Marketing is described as both a philosophy and a toolbox used by organisations to organise their activities (Jones et al., 2008). It has, however, for a long time been a practice focused merely on making an organisation's offerings attractive to its customers (Kotler, 2011; Jones et al., 2008), many times only to convince customers to buy unnecessary things (Lim, 2016).

The practice of marketing has shown to be dynamic, implying that the practice changes along with changes in the society and the context it is practised within (Mela et al., 2013). Nowadays, it is about to change in the direction of sustainability issues. Kotler (2011, p. 132) points out the importance of marketers reconsidering their practices and that organisations "must address the issue of sustainability", which is also argued by Rudawska (2019). In line with this, Foltean (2019) writes that the new key area in marketing is sustainable marketing.

Sustainable marketing is described as “[...] creating, producing and delivering sustainable solutions with higher net sustainable value whilst continuously satisfying customers and other stakeholders” (Jones et al., 2008, p. 125). It is a rather new emergence in literature and has seen little development (Rudawska, 2019). It is suggested that sustainable marketing is the result of an encounter between green marketing, social marketing and critical marketing (Gordon et al., 2011).

Green marketing allows organisations to get a preferable environmental image while also get a profit (Sun et al., 2019), as well as encourage sustainable consumption (Gordon et al., 2011). It is currently used for areas such as sustainable packaging and using less harmful substances (ibid). There are both benefits and negative aspects of such a marketing approach. It could be

8 a source of profit as products that are good for the planet are becoming increasingly popular. However, some customers perceive green marketing as greenwashing (ibid), where some organisations are not very interested in sustainability but rather see it as something they have to communicate to stay competitive as a business (Jones et al., 2008).

Social marketing has more of a welfare approach and consider individuals and societies wellbeing (Sun et al., 2019), and is also concerned with how to affect people's behaviour (Gordon et al., 2011). It "[...] uses commercial marketing techniques to benefit society as a whole […]" (Johns, 2019, p. 127). It is a common practice within the area of public health (ibid) and has also shown helpful to push policymakers to consider various policies (Gordon et al., 2011).

According to Gordon et al. (2011), green marketing and social marketing do not equal sustainable marketing. A third dimension is needed. Critical marketing is less of a marketing practice but instead works as a tool to analyse marketing theory, which means it is often evident when marketing theory is questioned (Burton, 2001). Currently, it is used to assess, amongst other things, travels, food and clothes marketing from a sustainability perspective (Gordon et al., 2011).

There are weaknesses in each of the three approaches to marketing, therefore a holistic approach including all of them needs to be considered for sustainable marketing (Gordon et al., 2011). Gordon et al. (2011) explain these weaknesses as "[...] green marketing alone can do harm; social marketing alone cannot compete; critical marketing alone will not do the all-important job of changing hearts and minds". When the three approaches are interconnected within an organisation, it is possible to affect sustainable development in a positive way (ibid).

Sustainable marketing is becoming increasingly popular to investigate (Sun et al., 2019), but it is still an area in need of more research (Rudawska, 2019; Foltean, 2019). Particularly in past literature, sustainable marketing as a concept has been questioned since sustainability and marketing can be perceived as contradictions to one another because marketing is said to push consumption so that economies grow, while sustainability also includes environmental and social concerns and wish for economies to grow in a sustainable way (Lim, 2016). To cover the social and environmental aspect in a marketing practice while still having customers that

9 are willing to pay for the offering is one big challenge that sustainable marketing faces (Jones et al., 2008).

When using sustainable marketing, it is essential not to get caught in 'sustainable marketing myopia', where too much focus lies on creating sustainable products and services and as a result lose focus on fulfilling actual customer needs (Lim, 2016). To succeed with sustainable marketing, it is therefore beneficial to communicate the sustainable benefits of the product or service properly, since customers rarely are willing to buy such products if they do not understand its benefits (ibid). The organisations that have included sustainable marketing in their operation do this mainly in a fundamental way, perhaps implying that such marketing practice has not been used for a long time (Rudawska, 2019). Ethical aspects, which should consider the benefits for society in whole, is also of high importance for sustainable marketing to succeed (ibid).

It is clear that sustainable marketing may amount to several challenges for organisations. Convincing people that the sustainable choice is the right choice is one big challenge (Lim, 2016). This challenge is connected to human behaviour and decision making, meaning it can be eased by being able to make people act in the most preferable way. There is one tool from the field of behavioural economics that can help achieve this, and it is called nudging.

2.2 Nudging as a tool for sustainable marketing

2.2.1 An introduction to nudging

Nudging is a tool which allows organisations to construct choice options in such a way that the choice that is most beneficial for the individual and society is the easiest choice to make (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008). Therefore, it could be of great use when an organisation wishes to influence the choices that people make. Nudging stems from behavioural economics which is a sub-field of traditional economics that combines psychological aspects with traditional economic theory (Thaler and Mullainathan, 2000). The psychological aspects are said to help create "[...] a more realistic description of individual behaviour […]" (Croson and Treich, 2014, p. 346) compared to neoclassical economic theory. Thaler and Mullainathan (2000) claim the neoclassical economic approach to be anti-behavioural in nature and completely ignorant of any aspects of human behaviour. Thaler and Sunstein (2008) acknowledge that there are several aspects of human behaviour that can lead to mistakes. Kahneman (2003) presents the two

10 modes of the brain, intuitive thinking and reasoning, or system one and system two as they also are called. When using automatic and effortless thinking, known as system one, it is common that decisions do not result in the best possible outcome (ibid). In these cases, nudges can be very helpful in altering behaviour which will not be beneficial (Hausman, 2010).

The term nudging was widely introduced by Thaler and Sunstein (2008). Their book has since its release sparked a wide conversation on the topic, and potential opportunities and risks have emerged (Hausman and Welch, 2010). One example of nudging from the book is the situation where a cafeteria owner has to decide where to place the different types of food on her counter. How the owner chooses to arrange her products will ultimately influence the choice process of those who will eat at her cafeteria. This allows her to arrange the food in such a way that it would make visitors more prone to choose healthier options (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008). The original definition of nudging as explained by Sunstein and Thaler goes as follows;

"A nudge, as we will use the term, is any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people's behaviour predictably without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy and cheap to avoid. Nudges are not mandates. Putting fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not."

(Thaler and Sunstein, 2008, p. 6)

The ‘choice architecture’ in this definition refers to the design of a particular choice situation and could be both good and bad (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008). The choice architect (such as the owner of the cafeteria) has the power to design the decision process in a way that makes some choices easier or more difficult to make for the people who are being influenced by nudging (hereafter mentioned as ‘nudgee’). The choice architects themselves might not be aware of the power they possess. The person designing the choice situation will be the choice architect independently of whether he or she is aware of or has an intention behind the design or not (ibid).

Thaler and Sunstein (2008) also touch upon the issue of when it is necessary to use nudges. They mean that people are in most need of nudges when they are faced with a more complex decision and where the nudgee has little expertise and capability of taking a well-informed decision. This expertise can be presented by organisations who have knowledge within their

11 field. To make good nudges, there is also a need for the choice architect to be able to guess what will lead to the best outcome for the nudgee. This is why the most beneficial circumstance for nudging is where the nudger can provide more expertise and where the differences in preferences are not that big. Thaler and Sunstein (2008, p. 247), therefore, conclude that “nudging makes more sense for mortgages than for soft drinks”.

2.2.2 Four Types of Nudges

The Nordic Council of Ministers (2016), Lehner et al. (2016) and the Science and Technology Select Committee (2011) have identified four main ways to change people's behaviour by using nudging. These ways are not necessarily connected to a specific definition of nudging but can instead be seen as practical tools. These four types of nudges are; Provision of information, use of social norms and regular feedback, changing the physical environment and changes in default options.

To use information to nudge people lies on the assumption that people wish to do the right thing but may lack the information on how to do so (Campbell-Arvai, 2012). Some research also sees that it is important how the choice architect presents the information as well as what information that is presented (Lehner et al., 2016). One way to nudge through information is to target energy consumption, for example showing the usage and impact of energy use (ibid). Better options of energy use may also be nudged through default options, where there is a higher number of customers using green electricity when this is the default option (Campbell-Arvai, 2012). Studies have shown that changing the default option to a preferable one has had great impacts (ibid), and this type of nudge is seen as the most promising type (The Nordic Council of Ministers, 2016). Social norms may also have a great impact on human behaviour (Schubert, 2017) since humans are strongly influenced by social norms (Lehner et al., 2016). Several experiments have shown that this is true. One increased the re-use rate of towels at a hotel by letting guests know that other's re-use them during their stay (Lehner et al., 2016). Another type of nudge has been used for a long time, as grocery stores have considered their physical environment, such as the placement of products carefully (Lehner et al., 2016). As a nudge, it also affects the choices made in relation to influencing pro-environmental behaviour (The Nordic Council of Ministers, 2016). One example of this is to reduce food waste by offering smaller plates for meals at a hotel to decrease food waste (Lehner et al., 2016).

12

2.2.3 Libertarian Paternalism and a Technical Definition - Two Contradictory Definitions

Thaler and Sunstein (2008) connect the term nudging, to the newly founded concept of libertarian paternalism. This term is explained as a liberty-preserving strategy that maintains freedom of choice. The paternalistic aspect of the term comes into play when choice architects influence behaviour with the aim of making people's lives longer, healthier and better (ibid). This is also the purpose of sustainable societies, where human wellbeing can be created while considering the earth's ecological limits (Robert et al., 2012). The same approach to human wellbeing and consideration of the earth's limits can be found in sustainable marketing, where social marketing aims to "[...] benefit society as a whole" (Johns, 2019, p. 127) and green marketing emphasises the importance of sustainable consumption (Gordon et al., 2011).

Although Thaler and Sunstein (2008) express excitement over what nudging and libertarian paternalism can do for societies, there is also a scepticism towards the combination of these two concepts. Hausman and Welch (2010, p. 125) express that "[...] some nudges are paternalistic; others are not". Nudges are, therefore, not always designed to benefit the people in question (ibid). A statement that is further supported by Hansen (2016) who claims that there are multiple definitions of the term nudging. He believes there is a conceptual need for a more technical definition of the term nudging that is focused on behavioural economics. The technical definition that Hansen suggests as the most suitable goes as follows:

"A nudge is a function of (I) any attempt at influencing people's judgment, choice or behaviour in a predictable way, that is (1) made possible because of cognitive boundaries, biases, routines, and habits in individual and social decision-making posing barriers for people to perform rationally in their own self-declared interests, and which (2) works by making use of those boundaries, biases, routines, and habits as integral parts of such attempts. Thus a nudge amongst other things works independently of (i) forbidding or adding any rationally relevant choice options, (ii) changing incentives, whether regarded in terms of time, trouble, social sanctions, economic and so forth, or (iii) the provision of factual information and rational argumentation" - (Hansen, 2016, p. 173)

Hansen (2016, p 174) believes this definition of the term would be most beneficial as “it makes sense to refer to the many marketing tricks used to fool us into buying things we don’t need as

13 nudges as well. That is, the technical definition recognises that it is possible to nudge ‘for bad’ or ‘for profit’ as well as ‘for good”. He further explains the danger of adopting a view of nudging as a sub-category or even equating the term with libertarian paternalism. This would entail that anyone that is supportive of nudging, consequently, also is of libertarian paternalism which is not the case with the technical definition (Hansen, 2016).

Hausman and Welch (2010) further discuss the ethical aspect of nudging and how any organised attempt to shape the way people choose might be considered as disrespectful and controlling. This is further supported by Grüne-Yanoff (2012), who argues that libertarian paternalism reduces the liberties of people as the power of the regulators will increase or because they simply influence and alters choice processes. He also states that the “[...] justification of the liberty-welfare trade-off is not compatible with liberal principles” (ibid, p. 644) which goes against the original view of Thaler and Sunstein (2008).

2.2.4 Conclusion of chapter

Marketing has for long been focused on making organisation's offering attractive to its customers (Kotler, 2011; Jones et al., 2008), and has by some been seen as a practice to sell unnecessary things (Lim, 2016). As society changes, so does marketing (Mela et al., 2013). With sustainable marketing as a new key area in marketing (Foltean, 2019), new challenges arise for marketing practitioners. Several of these challenges are concerned with making humans behave in a way that will lead to choices that benefit themselves and society as a whole.

To help with such challenges, organisations that use sustainable marketing would benefit from using a tool that helps them to guide people into making the right choice. Here, nudging can be a useful tool in the sense that it helps the user to present the most preferable option in a way which makes it the choice that is easiest to take (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008). Nudging is connected to the field of behavioural economics and particularly stems from libertarian paternalism that connects nudging to making choices that contributes to sustainable development (ibid). Hence, the tool fits well in addressing the challenges of sustainable marketing.

There is, however, also a more recent definition of nudging that do not connect it to sustainable development (Hansen, 2016). Hence, even though Thaler and Sunstein (2008) argue that organisations can use nudging as a tool to influence people’s choices, “[...] the evaluation of

14 nudges depends on their effects—on whether they hurt people or help them” (p. 247). This creates confusion for researchers and customers. It could potentially lead to customers being misled into thinking that an organisation is more sustainable than it actually is. Therefore, this research aims to explore the incentives behind an organisation usage of nudges and which of the opposing definitions sustainable organisations use in practice and how this affects their approach to nudging.

15

3. Methodology

This section presents the research philosophy, research approach and research design of this study. The researchers explain the selection process of the included cases and how the conducted interviews were structured. Lastly, this chapter will demonstrate how the collected data is analysed in order to answer the research questions.

3.1 Research philosophy

The research philosophy has to do with the development of knowledge and which systems and beliefs the researchers have chosen to apply to a particular study. The researchers will inevitably make some assumptions throughout the study, which in turn will influence how the research question, method and data is interpreted. In order to create a credible research philosophy, it is essential to have a consistent set of assumptions which fits well with the research project (Saunders et al., 2019).

In this particular study, the interpretivist research philosophy has been chosen as the most suitable one. Collis and Hussey (2014, p. 45) explain that this paradigm "[...] focuses on exploring the complexity of social phenomena" and aims to understand social phenomena through the interpretation of qualitative data. This fits well with the research as the aim is to explore the incentives behind an organisation's use of nudging for sustainable marketing in practice. Furthermore, from existing literature, it was made clear that there is no current agreement upon the definition of nudging, meaning that whoever uses them today may use them in any way they like. This urges for the use of an interpretivist paradigm since interpretivism suggests that reality is designed by how humans understand things (Collis and Hussey, 2014).

3.2 Research approach

The interpretivist research philosophy often tends to lead to an inductive research approach (Saunders et al., 2019). When it comes to topics that are newer and where there is little existing literature, the inductive approach might be considered more appropriate in order to generate data and reflect on theoretical themes (ibid). An inductive research approach means that you make conclusions based on observations and go from individual observations to later make

16 conclusions about general patterns on the topic (Collis and Hussey, 2014). Nudging is a fairly new topic which does not provide great amounts of existing data. The inductive approach, therefore, serves the purpose of this research well, as the researchers go on to deeper explore the topic to identify theoretical themes and patterns.

As an interpretivist paradigm was chosen for this research, the choice fell naturally on a qualitative approach since such an approach has a stronger connection to interpretivism (Collis and Hussey, 2014). To fulfil the purpose of this research, it was necessary to collect in-depth information to interpret rather than being able to statistically analyse the data, which implies that a qualitative approach fits better than a quantitative approach.

The purpose of this study is to explore how organisations have interpreted the definitions of nudging and how their underlying incentives affect the use of nudging in practice. An exploratory research approach allows us to gain new insights through techniques such as case studies (Collis and Hussey, 2014). Saunders et al. (2019) suggest that a small sample might be considered more appropriate than a large sample of subjects when using an inductive approach. The researchers have, therefore chosen to collect primary data for this research through a multiple case study where in-depth interviews were carried out with five organisations.

3.3 Research design

3.3.1 Multiple case study

For this research, a multiple case study has been used as the research design. A multiple case study may be used when a complex social phenomenon is to be understood (Yin, 2014). This fits well with the purpose of this particular research and its interpretivist paradigm. Yin (2014) further explains that a case study may be used to investigate circumstances when there is a vague connection between the phenomenon and the context it is used within. The context of nudging, the phenomenon explored in this research, is rather confusing in the sense that it may be used in several different ways and therefore impose different meanings. Therefore, a multiple case study is beneficial to use for the purpose of this study.

3.3.3 Sampling of cases

In this study, the cases consist of organisations, where four of them are profit-driven, and one is a municipality. The judgemental sampling method was used to select samples. Collis and

17 Hussey (2014)write that this method allows the researchers to choose samples based on how knowledgeable they are about the topic that is being studied. This was necessary for the research since the purpose is to look at sustainable organisations that use nudges, meaning that the researchers could not sample any random organisation. All cases were selected based on two criteria.

Firstly, the organisations had to engage in sustainable marketing. As sustainable marketing requires organisations to "[...] creating, producing and delivering sustainable solutions with higher net sustainable value whilst continuously satisfying customers and other stakeholders" (Jones et al. 2008, p.125) it was necessary to look for organisations that consider sustainable development in practice.

If a sustainability agenda is present, the organisation will aim to produce sustainable solutions as well as consider both customers and other stakeholders, which is aligned with the definition of sustainable marketing. From this reasoning, three different assessments connected to sustainable development were used to see whether organisations use sustainable marketing or not. These three assessments, listed and explained in Appendix 1, are; The Triple Bottom line, that clarifies that the organisation is prone to work with sustainability issues and has taken an approach which includes all factors that are necessary for sustainable development. If some of the UN Sustainable Development Goals are incorporated in their practice, this is also a clear sign that organisations take responsibility towards the planet and life on it. Lastly, the Global Reporting Initiative requires a payment if organisations wish to be a part of that initiative. If organisations are willing to pay money in order to do their reporting properly, it is likely that they are committed to sustainability actions. Which organisations that fulfil which assessments can be seen in Figure 2.

The second criterion of sampling was that the organisation had to use nudges. The chosen organisations have either been mentioned in a nudging context or claimed themselves that they have been using nudges. All organisations had, at some point, been mentioned in connection to external consulting firms that create nudges, where three of the organisations were sampled. However, two of the organisations nudging initiatives was found in newspaper articles and was for that reason asked to be a part of this research.

18 Figure 2: Which criteria’s the organisations have been chosen on, respectively.

3.3.4 Sampling of respondents

The interviewees acquired knowledge and experience regarding nudging and were, therefore seen as relevant to the interview. None of the interviewees requested to be anonymous. Table 1 provides an overview of the interviews.

19

Sector

Organisation Interviewee

Date

Duration

Second-hand

store chain Myrorna

Communication & PR

responsible,sustainability 10/3 45 min Modular carpets

industry Interface

Marketing Director for Norden &

Baltikum 25/3 45 min

Municipality Göteborgs Stad Traffic office, city clean up 1/4 40 min Restaurant

Service Klimato CEO 3/4 20 min

Housing

Cooperative HSB Market & Communication Manager 14/4 25 min Table 1: Details about interviews.

3.3.5 Introduction of cases

Interface

The organisation Interface was founded in 1973 and became a world leader in the modular flooring industry. It was one of the first organisations to make a public commitment to work for sustainability, which is the main topic of consideration and strategy in the organisation. Their current sustainability goal is to be climate positive by the year 2040 (Interface, 2020). Interface has participated in Nudge Global Impact Challenge, also called the Nudge Academy, that empowers organisations to create sustainable change (Nudge Academy, 2015).

City of Gothenburg

The City of Gothenburg is a Swedish municipality that takes care of education, healthcare and environmental issues amongst other things within the municipality. For this study, the traffic department of this organisation was the one of interest since it is in this department their nudging efforts have been conducted. For the traffic office in the city of Gothenburg, the main goal is to keep the city clean from litter. They also recycle, try to minimise the use of single-use products and work with waste management (City of Gothenburg, 2020). Their single-use of nudges was acknowledged in Göteborgsposten (Engelbrektson, 2017).

20

Klimato

Klimato is a startup company that offers four different services that mainly target restaurants. All of the services wish to address the contribution food makes to climate change. One of them calculates and presents carbon dioxide emissions for different food dishes. Another one gives restaurants a climate label to put on their most environmentally friendly dishes. They also help with writing climate reports in order for the restaurants to see their progress. Lastly, they provide climate compensation for restaurants. Hence, the overall idea of the organisation is to help restaurants to lower their emissions and help restaurant guests to make better choices. Their overall sustainability goal is to reduce food waste (Klimato, 2020). Klimato’s usage of nudging was announced on Nudging Sweden’s LinkedIn page (LinkedIn, 2020).

HSB

HSB is an organisation that plan, build, finance and manage housing accommodations. They have a sustainability initiative called HSB Living Lab, where they aim to find new innovative and sustainable solutions such as nudging initiatives to implement in their organisation. HSB's sustainability goals are based on the UN SDGs and the Swedish sustainability goals, which then resulted in eight goals for their own new productions projects (HSB, 2020). HSB has used external consultancy firms to create some of their nudges and has therefore been mentioned on several nudging consultancies web pages.

Myrorna

Myrorna is a Swedish retail chain that has been operating for 120 years and sell second-hand items. The organisation functions like any store chain, with a budget, sales requirements and financial surplus but donate their sales surplus to the Salvation Army's social work in Sweden. They have two main missions, where one is to help people that struggle to enter the labour market to get a job. The other mission is to inspire people to re-use items rather than buy new ones. In that way, they contribute to both social and environmentally sustainable development. Their engagement in sustainability is used as an ethical guideline for the whole organisation (Myrorna, 2020). Myrornas nudging project was mentioned in Svenska Dagbladet (Bolter, 2017).

21

3.4 Data collection

3.4.1 Semi-structured interviews

Primary data is collected for the purpose of a specific study by the researchers themselves (Collis and Hussey, 2014). For this research, the method of primary data collection was five semi-structured interviews. This is an interview method that allows for flexibility in the sense that all questions do not have to be prepared in advance (ibid). Collis and Hussey (2014) further mention that semi-structured interviews can be useful when concepts and ideas have to be understood in order to find opinions and beliefs of the interviewee. This fits well with the exploratory nature of this research and research questions. The researchers made use of the critical incident technique, which can be valuable since it helped interviewees to talk about issues in the context of their own experience about events that have occurred in real life and how these events developed (Collis and Hussey, 2014). For this research, it was a useful technique in order to understand the rationale behind why organisations choose to use nudging and how they experienced the process.

All interviews took place through online communication platforms such as Skype and Zoom or over the phone. The reason for which the interviews were not conducted face to face was because of the great distances between the researchers and sampled organisations. The use of online communication platforms avoids costs and emissions associated with travelling. When collecting data, it was also recommended by the Swedish Public Health Authority to limit travels due COVID-19. Furthermore, the interviews were conducted in Swedish to not make any misconceptions due to language barriers, as all interviewees, as well as the researchers, have Swedish as their first language. The interviewees were also asked if they were comfortable with having the interview recorded, so it was possible for the researchers to later return to the data and gain a clear and comprehensive understanding of the data.

Due to the increased risk of bias when using an interpretivist study, data triangulation was used. Both primary and secondary data was collected; secondary data was mainly used to strengthen what the respondents mentioned in the interviews. It was also useful to further investigate the nudges the organisations had made (Collis and Hussey, 2014).

22

3.4.2 Secondary data

Secondary data is described as already existing data (Collis and Hussey, 2014). In the case of this research, secondary data was gathered from the organisations' websites in order to collect more information and strengthen their statements. From newspaper articles, the researchers could see the outcomes of the nudges and the impact it had on the organisations sustainable marketing. Where the researchers found secondary data for the individual cases can be seen in Table 2 below.

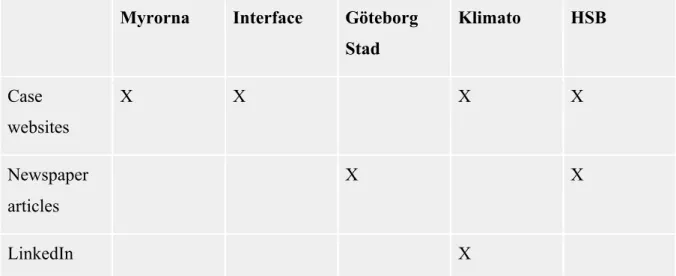

Myrorna Interface Göteborg Stad Klimato HSB Case websites X X X X Newspaper articles X X LinkedIn X

Table 2: Secondary Data sources

3.5 Data analysis

The data collected for this research was analysed through non-quantifying methods of analysis as an interpretivist research paradigm was chosen. The general analytical procedure was selected in order to systematically analyse the data of this study (Collis and Hussey, 2014). The procedure encompasses three flows that are occurring simultaneously throughout the process of analysis. The three flows are to reduce data, display data and draw conclusions while also making sure that the conclusions are valid (ibid), these flows can be seen in Figure 3.

23 Figure 3: General Analytical Procedure

As an interpretivist study often entails a large collection of data, the researchers have been careful about selecting the data that seem relevant to the research that helped to answer the research questions. The first step in the analysis was, therefore, to code the primary data from the conducted interviews with all researchers present. Twenty categories were then identified out of the codes and linked to each other in order to create five main themes, which can be seen in the data display in Appendix 3. The identified themes were; Marketing objectives affecting nudging, sustainability objectives, interpretation of nudging in the organisation, application of nudging and connection between sustainability and nudging. The data was then summarised and presented in the empirical findings chapter. Lastly, conclusions were drawn that responded to both of the research questions. This was made through firstly conducting a within-case analysis which is "[...] unique to the inductive, case-oriented process" (Eisenhardt, 1989, p. 532) which has been applied to this study. According to Eisenhardt (1989), a within-case analysis often presents data in a descriptive way. In this research, the within-case analysis consists of the empirical findings that have been connected to the theoretical framework in order to discuss the similarities and differences between theory and practice within each case. From this, it was possible to see with what incentives the organisations use nudging, respectively. Interpretations on which of the theoretical definitions that every organisation is the closest to was also made. As the last step, a cross-case analysis was conducted. This analysis made use of the interpretations and discussion from the within-case analysis in order to compare the organisation's incentives and definitions with each other. From this, patterns emerged that could provide answers to both of the research questions (Eisenhardt, 1989).

24

4. Empirical findings

In this section, primary and secondary data will be presented for each case after identifying and summarising all data that is relevant for answering the research questions. Each case will first present previous nudging initiatives that have taken place in the organisations. Then, the underlying incentives and beliefs of the organisations will be presented in order to create a better understanding of the perception of nudges. All quotes mentioned in this section has been gathered from the conducted interviews.

4.1 Myrorna

Myrorna expressed that they had a clear example on a nudge initiative that they have done, as seen in Figure 4. In the interview, Myrorna explained that the idea of the nudge was to see whether people who are aware of when they last used their clothes would get rid of more clothes than people who do not know how often they use a certain piece of clothing. Forty participants were selected, where half of them were given tools to mark their clothes with the latest date the clothes were used. All forty participants were told that the clothes they wish to get rid of were to be collected at a specific date. The initiative did not go as Myrorna thought, from the results, Myrorna figured that it would have been enough with a short piece of information on how people should behave.

Figure 4: Myrornas Nudge Initiative - “Sustainability project to keep your closet in order”. (Myrorna, 2017)

After assessing this unsuccessful nudge, they realised that they did not identify a problem before implementing the nudge. They used the nudge to see whether a problem existed or not

25 and came to the conclusion that nudges are not helpful in performing such tasks. This initiative, however, made their customers more conscious of their consumption patterns. Therefore, Myrorna created another nudge in the form of a free micro-course where you received an email every day on information on what you can do with your consumptions patterns. During the interview, they said that "this micro-course is our first step in consciously working with nudging to help people change their behaviour […]". This particular nudge was also mentioned on their webpage but was not stated as a nudge there.

Another nudge they have used is the introduction of second-hand clothes in stores that do not sell second-hand clothes otherwise to challenge social norms. They also considered the placement of products in their own stores, such as placing a certain type of product close to the checkout counter. Myrorna also expresses in the interview that they "[...] use simple sales messages to make people feel good about shopping second hand, such as mentioning that second-hand shopping is a contribution to social and environmental sustainability".

Myrorna defines nudges as "[...] it pushes people in a certain direction, through perhaps giving inspiring tools, for example, some form of controlling communication". The purpose of their nudges is that "it should be easy to make the right choice". They believe that it is a tool that can be used for sustainability, but they "[...] would not say that nudges themselves are connected to sustainability, it is just a way to change behaviour". It can just as well be used for unsustainable purposes. When they use nudges, they believe that it is ethical and a positive thing, since their goal is that people should use their clothes for longer. When considering how to nudge people, Myrorna says that they see that they want their customers to act in a certain way. They have a continuous discussion about how the customer acts at the moment and how they can alter this behaviour.

From Myrornas point of view, there is clear potential in nudging projects to catch the attention of people. In the future, they want to use it to get the attention of people who normally do not buy second hand. They also express that it is important that we change the way we currently think in order to adapt to sustainable development. Here, they think nudging has an important role and can contribute. They had also realised that they used nudges before they knew what it was.

26

4.2 Interface

Interface describes their practical usage of nudging as their product offerings since they are a sustainable company offering sustainable products. When asked to explain an example of a previous nudge, Interface mentions a project they have created. The intention of the project was to do good and 'touch' people which the interviewee emphasised to be considered as a nudge. On Interface website there are practical examples on the types of projects that Interface described in the interview, one of them is called "Climate take back" which is a new mission for Interface sustainability journey, see Figure 5 (Interface, 2020). The project was to try to use the time they have with their customers to promote the sustainability journey of Interface and then ‘push’ them to believe that Interface is the obvious choice for them because of the different positive environmental aspects the company stands for.

Figure 5: Interface project (Interface, 2020)

Storytelling was also claimed to be a tool that could be used for nudging when they said: “[...] that is also an example of nudging, to approach each other in this area in hopes of making the customer make a sustainable decision to choose Interface’s products for a certain project [...] depending on the sustainability goals of the customer."

Interface does not "[...] talk about nudges or nudging as a term, it is rather something we do". When asked, they say that they see nudging as "[...] marketing and communication initiatives that touch the target group and make it [the target group] act, hopefully, in the way you wish".

27 They explain that they “[...] want them [the customers] to make an active, sustainable choice and choose our products because we have worked really hard to make them as good as possible”. It is further mentioned that they believe nudging is a good tool for sustainable marketing. Interface claims that it is probably not common that people connect nudges to sustainable behaviour.

4.3 Klimato

Klimato mention one example of a nudge they have used as helping their customers to present the climate impact of their food. They did this by showing them graphs and comparisons on their food emissions by comparing vegetarian and meat dishes, Figure 6 shows an illustration of the menu comparison from their website, Klimato (2020). “We try to [...] work with nudging in different ways” both towards the end-customers and companies and restaurant chefs.

28 Klimato wants to create a factual and transparent way to nudge people towards sustainable choices. “Partly with our climate labelling to influence the consumer to choose more environmentally friendly [...] and we also use our report function and climate goals towards the companies to change their behaviours and transforming their business so that they become more sustainable”. Klimato later claims that they are not sure if this example could necessarily be connected to nudging, but they have seen that the chefs in question have learned to lower their emission and that their service has encouraged chefs to change their menus to more environmentally friendly ones.

Klimato says that they wish for their climate label to be "[...] a social norm so that when guests go to a restaurant that does not have Klimato, they say that why do you not show your [environmental] impact when others do that […]".

Another nudge they mentioned is that they are developing an app for "normal people" or end-customers, where the idea is that you can find Klimato restaurants where you can collect points and compare your own emissions with your friend's emissions. For example, you can compare a person that lives in Malmö with a person from Stockholm, or between different offices. This can, in its own way, inspire and nudge people to make more climate-friendly options.

When asked about their own definition of nudging, Klimato described it as "[...] when you succeed in changing behaviours [...]". After this statement, they continued to explain that "[...] we don't really have a definition, even though we work with nudging more or less, we usually say that we inspire people to make smart choices or encourage them". They also use the term "sustainable nudging" when describing how they work with nudging by inspiring, guiding and encouraging people to make sustainable choices. Klimato believes that nudging can be used as a tool for sustainable marketing if it is used in the correct way. Klimato expresses that the word nudge has a positive meaning.

They move on by saying that they “ [...] think it's important to work with nudging by letting the person in question, or the object, have their own choices and not force them to do this, or eat like this, buy this, but rather work with open choice options”. When discussing nudging, they mention the importance of not pointing fingers at anyone who, for example, eats meat but rather have a positive encouragement strategy instead.

29

4.4 HSB

One example of a nudge is when an external consultant came up with the idea of building a hen house next to an accommodation to influence people’s food waste and educate them about how long it actually takes for an egg to be produced. They are not sure if the hen house could be called nudging, but they would classify it as influencing. The hen house was actually successful and reduced food waste, see Figure 7.

Figure 7: HSB Living Lab - "Hens decrease food waste."

Another example of nudging is when HSB previously have used encouragements like; "close the tap!" or "turn of the lamp!". However, they consider their most successful type of nudge throughout time to be those connected to waste management. If they provide waste management opportunities close to the housing, it automatically increases. This is also the most tested type of nudge in HSB. They used both provisions of information and accessibility for their nudge. In some housing associations, it even turns into regulations.

30 They mention a third initiative they did to make water savings as a game you can install on your phone where the one who saves the most water wins. But they are unsure whether this qualifies as a nudge or not.

HSB does not believe that it is beneficial to mention their use of nudging in their marketing since a nudge is supposed to "[...] be something that you build in, it is not really supposed to be noticed. It is only supposed to make everyday life easier [...]". Therefore, the organisation claims that they do not want to be associated with the term nudging. Not because there is anything wrong with the connotations of the term, but because they rather choose to focus on the end results of the nudge. They do, however "[...] feel good about yourself in the process. Almost like when you recycle plastic bottles and cans". They consider the risk of making things sound better than they are and that this could potentially lead to greenwashing, which they aim to avoid.

HSB define nudging as a way to influence people, for example, by pushing a customer in the right direction. They say "Well, it is a way to influence, for example, a customer in the right direction. It should be easy to make the right choice". They definitely believe that nudging will be used more in the future. When asked if they connect the term nudging to sustainability, HSB answered “absolutely, especially in terms of transports, energy use, waste management and even loans. Everything that lowers a threshold”. They also think that nudging is supposed to make everyday life easier for the nudgee and that the nudge is not supposed to be noticeable.

Nudging for HSB is not viewed as something that is beneficial especially for sustainable marketing. Instead of mentioning that they use nudges in their marketing, they want to express the "added value" the nudgee gets from the behaviour they are being nudged towards. They do not see the point in saying that they "built-in something tricky" to change people's behaviour. HSB was more interested in the results of the nudge and did not see that the use of nudging in itself would be something that the customer wants to hear.

31

4.5 Göteborgs Stad (the city of Gothenburg)

The city of Gothenburg mentions that people are very much aware of the behaviour of others and wish to fit into the social norms. Therefore, the problem with, for example, littering of cigarette butts, can be hard to avoid since throwing those on the ground is a very common behaviour. Before the city of Gothenburg considered using nudging as a tool, they found that littering was a big problem in the city, and they saw the opportunity to start using nudging to get rid of this problem.

Figure 8: Newspaper article about their nudging example, Göteborgs-Posten(2017)

The city of Gothenburg mentioned several examples of nudges they have used.One is that they painted their waste bins and ashtrays in different colours and wrote messages to encourage people to look for the ashtrays. One message was; “Do you know that there is an ashtray in our orange waste bin?”. This nudge was successful and got a lot of media coverage. They were mentioned in a newspaper article in Göteborgs-posten (2017) as seen in Figure 8, as well as the tv-channels Tv4 and SVT väst. After carrying out this initiative, about 50 other municipalities reached out to them as they were curious about the results of their nudging.

Another nudge was at a beach that had problems with littering. They then removed all the littering bins from the beach and placed a container there. "We put up a sign there and wrote

32 on it: 'On this beach, we throw the litter in the container' [...]. Then, the social norm was that here we clean up and throw away the litter".

They also mentioned a nudge that did not go well. They placed plastic bottles and cigarette butts in Slottsskogen in order to acknowledge the problem with littering. Waste bins were marked clearly to make people use them more, but the nudge resulted in people throwing more litter in Slottsskogen since there already were plastic bottles and cigarette butts there.

Göteborgs Stad said that nudging is when you "try to turn around, or affect people to change their behaviour with help from different things". They further explain "For me, it [nudging] is a tool for sustainability, and I never knew about the word nudging until I got in contact with 'A Win-Win World'. Well, we have done this before, but now we got a word for it." When asked about what their sustainability goals are, they answered "I actually don't know that! I thought you were interested in nudging and what we are doing. Sustainability… I don't dare to answer."

When discussing examples of nudges that other organisations have made, they mention that it also can be used only for the purpose of earning money. When they make nudges, they want them to be fun since they do not believe that pointing fingers works. Nudging should be about offering the right alternative in an easy way. They further mention that they believe that people are willing to do the right thing if they get the chance to do so; therefore the right choice should be easy to take.

They claim to be the first ones in Sweden to try nudging. Other municipalities got very interested in the results and the practicality behind the nudge. Due to this, the city of Gothenburg thinks that people associate them with nudging, an association they do not know if they benefit from or not.

33

5. Analysis & Discussion

The following section presents the study's analysis and discussion, which aims to compare, investigate and analyse theory with collected empirics. The researchers will first provide a within-case analysis on each organisation separately and then compare the results in a cross-case analysis in order to identify potential patterns. The section discusses the study's results with the intention of providing a basis for the thesis conclusion and suggestions for future research.

5.1 Within-case Analysis

5.1.1 Myrorna

According to Myrorna, they use nudging for positive purposes as they think "it should be easy to make the right choice". They also believe that their own nudging is ethical since their goal is to make people use their clothes for longer, which is ultimately good for the environment and society. These statements are interesting since it can be presumed that Myrorna sees nudging as Thaler and Sunstein (2008) did when they connected it to libertarian paternalism. However, when asking Myrorna about their definition, they say this; "[...] it pushes people in a certain direction, through perhaps giving inspiring tools, for example, some form of controlling communication". They are furthermore clear that nudging does not necessarily have to be connected to positive outcomes or sustainable development at all. The lack of societal benefits and sustainable development in their definition makes it fall better in line with the technical definition Hansen (2016, p. 173) mentions in his article. Especially similar is the part of Hansen's definition where he says that "A nudge is a function of (I) any attempt at influencing people’s judgment, choice or behaviour in a predictable way [...]”.

Myrorna has used nudging through small sales messages to make people feel good about shopping second hand as well as introducing new sections in traditional clothing stores in order to change social norms. Both of these initiatives may be traced back to the incentive of promoting sales. This is not aligned with the paternalistic aspect of nudging, which has the aim of "making their [the nudgee's] lives longer healthier and better (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008). A conclusion can be drawn that the incentives of nudging for Myrorna varies. In some cases, nudging is used as a traditional marketing tool to promote sales, whilst in others, it can be

34 connected to libertarian paternalism as the ultimate goal is connected to sustainability and the wellbeing of the environment and society.

Furthermore, Myrorna has identified a clear potential in nudging projects to catch the attention of people. This might suggest that the use of nudges in itself could be considered an incentive for its use for Myrorna. They are not afraid of being associated with the term nudging as suggested by this expression; "We went out in media and bragged about nudges pretty hard". It can be discussed whether Myrorna would prefer this association if they defined nudging as the technical definition suggests; as a technical tool.

While Myrorna is aware of what nudging is and is able to provide us with a definition, they gave one example of a nudge they have used. This example, as mentioned in the empirical findings, forced their participants to mark their clothes to see how often they use each piece of clothing. This might be considered an experiment rather than a nudge since nudging should not force people to take any action. Myrorna also mentioned that they had not acknowledged any clear problem before implementing the 'nudge’. Thus, they did not have any clear incentives with the 'nudge', besides from conducting a test to see the outcome.

5.1.2 Interface

Interface says that they do not "[...] talk about nudges or nudging as a term, it is rather something we do", which can be interpreted as if the dualistic definition of the term does not impact how Interface sees nudging. They consequently could not provide any clear definition of nudging they made use of within the organisation. However, as stated in the empirical findings, Interface mentioned that they connect the term 'nudging' to "[...] marketing and communication initiatives that affect the target group and makes it [the target group] act, hopefully, in the way you wish". The definition Interface mention is not in line with any of the dualistic definitions theory mentions. However, since Interface does not consider any aspect of sustainability or societal benefits in connection to nudging, it may be that their definition fits better with Hansen's (2016) definition that does not mention such aspects either.

When discussing the practicality of their nudges, it becomes clear that the main incentive of Interface's nudges is to sell their products. One project which they mentioned as nudging had the goal of making customers believe that Interface's products were the obvious choice for

35 those looking for a sustainable alternative. Another nudge they have made had a similar incentive, where they say they communicated that the customer would make a sustainable choice if choosing Interface's products. This can also be interpreted as they want their customers to feel like they have done the right thing by purchasing their products. However, the results Interface sees from that nudge, if successful, is an increase in sales and satisfied customers which most likely will generate more sales.

Even though the main incentives behind Interface's nudges seem to be to earn money, the nudges are designed in a way that will contribute to sustainable development. The nudges that Interface mention are merely their own sustainable product offerings. Therefore, Interface makes a good example of how nudging may be used to address the challenge sustainable marketing faces in convincing people that the sustainable choice is the right choice. It does, however, also make it a bit confusing since the incentive behind Interface's nudges can be connected to the technical definition which disregards sustainability. But still, the outcome of the nudge if successful, will be a sustainable one.

5.1.3 Klimato

Klimato described their own definition of nudging as "[...] when you succeed in changing behaviours [...]" and that they "[...] think it's important to work with nudging by letting the person in question, or the object, have their own choices and not force them to do this, or eat like this, buy this, but rather work with open choice options". This proposes that Klimato's definition is focused on the outcome of the nudge since they mention that the initiative has to 'succeed' for it to be considered a nudge. There is, however, inconsistency in how Klimato explains nudging, since they also say that "[...] we don't really have a definition, even though we work with nudging more or less, we usually say that we inspire people to make smart choices or encourage them".

Some of the nudges Klimato mention can be connected to the four types of nudging mentioned in literature. One of these is that they let their customers provide information to the end-customer in terms of climate labelling. This is a clear example of the nudging type 'provision of information'.

36 During the interview, Klimato also uses the term "sustainable nudging" which could imply that they recognise that nudges also can be 'unsustainable' in nature. Therefore, it can be interpreted as if Klimato is aware of there being a dualistic definition of nudging. This is also visible when looking at the examples of the nudges they provide. For example, Klimato claims to be nudging other organisations by encouraging them to use their climate label with the argument that other organisations are doing it. This suggests that there is a clear incentive to enhance the opportunity of earning money. As Klimato's service offerings are sustainable, it can be argued that they use both of the definitions of nudging. Here, the aspect of their incentive to earn money would count as a technical nudge, while them offering a sustainable choice could be connected to the definition by Thaler and Sunstein (2008).

5.1.4 HSB

HSB is a clear example of an organisation that has aligned their definition of nudging with the incentives behind their nudges. They say that nudging is "[...] a way to influence, for example, a customer in the right direction. It should be easy to make the right choice" and that they see a connection to sustainability. Their definition is also clearly aligned with what Thaler and Sunstein (2008) explain as nudging. As HSB uses the word 'influence', one can presume that they do not consider nudging as forcing a certain alternative upon anyone, which is also mentioned by Thaler and Sunstein (2008) when they say that a nudge should "[...] be easy and cheap to avoid". When HSB says that "It should be easy to make the right choice" and then mention that nudging is connected to sustainability, they make the same connection as Thaler and Sunstein (2008) do when they interlink libertarian paternalism and the aspect of sustainability with nudging.

As previously mentioned, HSB’s example on nudging can clearly be connected to how they describe nudging. An evident example is that they choose to place waste management close to the living area, which increases the waste being properly thrown away. This nudge is arguably helpful with influencing the 'customer' in the right direction as well as beneficial from a sustainability point of view. Also, the nudge where people compete in who saves most water fits nicely with how HSB describe nudges. Both of these nudging examples, as well as the other ones mentioned in empirical findings, have a clear incentive; to contribute to sustainable development.