Humanitarian Aid

A qualitative study of the ethical reasoning behind the allocation

from the perspective of five Swedish-based organizations

COURSE:Bachelor Thesis in Global Studies 15 ECTS PROGRAMME: International Work – Global Studies AUTHORS: Jennelié Danielsson, Anna-Maria Polasek EXAMINER: Johanna Bergström

Abstract

Jennelié Danielsson and Anna-Maria Polasek Pages: 33

Humanitarian Aid

A qualitative study of the ethical reasoning behind the allocation from the perspective of five Swedish-based organizations

The Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their Additional Protocols aim to protect those people who are not “participating in the hostilities” of war, such as “civilians, health workers and aid workers” and are the pillar of humanitarian law (International Committee of the Red Cross, 2010). The humanitarian principles including humanity, neutrality, independence and impartiality, are based on the international humanitarian law and committed to by all member states of the European Union (European Commission, 2019). Although these principles exist to guide the humanitarian organizations in their assistance and allocation of humanitarian aid, they are sometimes overlooked in terms of, for instance, self-interest, strategic motives and media attention. This results in ethical dilemmas for humanitarian organizations.

The aim of this thesis is to examine how Swedish aid donors, both a governmental and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), reason ethically in relation to the allocation of humanitarian aid towards conflict-affected areas. Semi-structured interviews have been conducted with four Non-Governmental Organizations and one governmental organization in order to examine and compare their ethical reasoning. The theories of consequentialism, utilitarianism, deontological ethics, socialization and rational choice have been applied to investigate the research questions further.

The results broadly indicate that all participating organizations reason similar in terms of ethics in contrast to the findings in the previous research. For instance, they all follow the humanitarian principles and use additional ethical frameworks in the allocation of humanitarian aid. Many similarities were found among the NGOs and the governmental organization as well as a few differences.

Keywords: Humanitarian aid, Humanitarian principles, Ethics, NGOs, Aid allocation, Aid donors

JÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITY

School of Education and Communication International Work

Bachelor Thesis 15 credits Global Studies Spring 2020 Mailing Address School of Education and Communication Visiting Address Gjuterigatan 5 Telephone 036-101000

Acknowledgements

To begin with, we would like to thank our supervisor Marco Nilsson at the School of Communication and Education at Jönköping University for providing us with valuable knowledge and guidance since day one. Further, we would like to thank the participants who, in the current stressful situation of Covid-19, took their precious time to share their experiences and expertise. Without our participants, this thesis would not have been possible to conduct. To family and friends for their unfailing support, especially throughout challenging periods, thank you. Lastly, we would like to express gratitude towards each other for constant support, encouragement and positivity since the beginning.

Table of contents

1. Introduction 1

2. Aim 2

2.1 Research questions 2

3. Definitions and theoretical concepts 2

3.1 Definitions of concepts 2

3.2 Consequentialism 4

3.3 Utilitarianism 5

3.4 Deontological ethics 5

3.5 Socialization theory 5

3.6 Rational choice theory 5

4. Previous research 6

4.1. Aid allocation and ethics 6

4.2 Self-interest and strategic motives 7

4.3 Media 8 4.4 Ethical dilemmas 8 5. Method 10 5.1 Limitations 10 5.2 Sampling 11 5.3 Collection of data 12

5.4 Recording and transcribing 13

5.5 Analysis of data 13

6. Result and analysis 13

6.1 Ethics regarding allocation 13

6.2 The dilemma of self-interest and strategic motives 18

6.3 The power of the media 20

6.4 Allocation based on costs and benefits 22

7. Discussion 24

8. Conclusion 26

8.1 Scientific relevance and future research 26

9. References 28

Annex 1: Interview guide 31

1. Introduction

In the year of 2020, 168 million people are estimated to need humanitarian support and protection, which is five times the amount of people in comparison to 20 years ago. The reasons behind the increased humanitarian need are due to a rising number of armed conflicts, food shortages and natural disasters. The purpose of humanitarian aid is to prioritize people with the most urgent needs (Sida, 2020a), as well as to save lives and mitigate the suffering of people who are affected by conflicts or natural disasters (Humanitarian Coalition, n.d.). In addition, humanitarian aid aims to strengthen communities and their ability to protect and recover after a crisis (Sida, 2020a).

The humanitarian principles include humanity, neutrality, independence and impartiality which aim to guide humanitarian actions. Through the international humanitarian law, the principles “have been taken up by the United Nations in General Assembly Resolution 46/182 and 58/114” (UNHCR, n.d.). The importance of respecting and acting from these principles has been emphasized by the General Assembly. These principles are of high importance and are followed by many humanitarian organizations, both to promote and act in line with the humanitarian principles is crucial for cooperation between organizations on the ground (Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2012).

In the case of Sweden, 52.1 billion SEK, which corresponds to 1 percent of the GNI, was estimated for the aid framework of 2020 (Sida, 2020b). Sweden was one of the five members in the OECD during 2018 who reached the 0.7 percent target of the GNI set by the United Nations (Parker, 2020). The Swedish government has together with the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) developed a strategy plan for 2017–2020 regarding the humanitarian aid where the goal is to contribute to:

[...] needs-based, fast and effective humanitarian response; increased protection for people affected by crises and increased respect for international humanitarian law and the humanitarian principles; increased influence for people affected by crises. (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2017)

Despite the good intention of humanitarian aid, it does not come without ethical dilemmas. For instance, research has shown that humanitarian aid can contribute to worsen a conflict (Stein 2001; Wood & Sullivan, 2015) which contradicts its purpose. Further, several studies have shown that the allocation of humanitarian aid is based on factors other than needs, such as self-interest (Donini, 2017; Einarsdóttir & Gunnlaugsson, 2016; Narang 2016), strategic motives (Narang, 2016) as well as media and fundraising (Einarsdóttir & Gunnlaugsson 2016; Olsen, Carstensen & Høyen, 2003). These dilemmas indicate that the humanitarian principles are overlooked, despite their importance for humanitarian organizations.

The majority of the studies found regarding the topics of aid and conflict-affected areas were quantitative (Gutting & Steinwand, 2017; Narang 2016; Savun & Tirone, 2019; Wood & Sullivan, 2015). Based on this, a clear knowledge gap was noted partly about the lack of

qualitative research as well as a combination of a deeper investigation of the ethics behind allocation to conflict-affected areas from the perspective of Swedish-based organizations themselves, which is what this study can contribute to.

2. Aim

The aim of this study is to examine how Swedish aid donors, both a governmental and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), reason ethically in relation to the allocation of humanitarian aid towards conflict-affected areas.

2.1 Research questions

● How do Swedish aid donors reason ethically to allocating humanitarian aid to conflict-affected areas?

● Are there any similarities and differences between how the Swedish governmental organization and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) reason ethically?

3. Definitions and theoretical concepts

The following section consists of five different theories and concepts of relevance for the understanding of this study. Hence, the study is deductive in the sense that the theories of consequentialism, utilitarianism, deontological ethics, socialization as well as rational choice theory are applied on the empirical findings. These theories were selected due to their relevance of the topic of ethics as well as to provide with a deeper analysis, which align with the aim of the thesis.

Firstly, the theory of consequentialism focuses on to determine if an action is morally right or wrong based on the consequences of that specific action (Graafland & Bosma, 2013; Fitzpatrick, 2008). Secondly, utilitarianism, which is a consequentialist theory, focuses on what consequences generate the most good (Graafland & Bosma, 2013; Hansson, 2009). Third, deontological ethics emphasizes duties which in turn decide if a behavior or an action is morally correct (Hansson, 2009). Fourth, the socialization theory implies how individuals and media are affected by each other (Giddens & Sutton, 2013). Lastly, the rational choice theory highlights rational behavior for individuals to reach their goals as well as taking costs and benefits into account when making a decision (Scott, 2000).

3.1 Definitions of concepts

Conflict-affected areas

UN Global Compact explains the concept conflict-affected area in different ways. First and foremost, an area where high level of armed violence might occur. Second, where there are concerns about human rights, political and civil liberties being violated. In addition, a conflict-affected area could be an area experiencing some kind of organized violence and lastly, an area which is transitioning from conflict to peace (United Nations Global Compact, n.d.).

Core Humanitarian Standards (CHS)

These core standards set out nine commitments that humanitarian organizations can apply in order to improve the quality as well as the effectiveness of their assistance (Core Humanitarian Standard, n.d.).

Donor

The Etymology Dictionary explains a donor as someone who “gives or bestows, one who makes a grant” (Etymology Dictionary, n.d.). In this thesis, the concept of a donor refers to an organization who allocates aid.

Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their Additional Protocols

The Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their Additional Protocols aim to protect those people who are not “participating in the hostilities” of war, such as “civilians, health workers and aid workers”. In addition, The Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their Additional Protocols “are at the core of humanitarian law [...] which regulates the conduct of armed conflict and seeks to limit its effect” (International Committee of the Red Cross, 2010). The humanitarian principles are based on international humanitarian law and committed to by all member states of the European Union (European Commission, 2019).

Humanitarian aid

Humanitarian aid refers to aid which is aimed at life-saving and the alleviation of suffering of people during as well as after a natural disaster or an armed conflict has occurred (Humanitarian Coalition, n.d.).

Humanitarian principles

The humanitarian principles consist of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence. Many humanitarian organizations are committed to these principles which origins from “the core humanitarian principles, which have long guided the work of the International Committee of the Red Cross and the national Red Cross/Red Crescent Societies” (Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2012).

Humanity refers to that “human suffering must be addressed wherever it is found. The purpose of humanitarian action is to protect life and health and ensure respect for human beings” (Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2012).

Neutrality emphasizes that “humanitarian actors must not take sides in hostilities or engage in controversies of a political, racial, religious or ideological nature” (Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2012).

Impartiality defines:

humanitarian action must be carried out on the basis of need alone, giving priority to the most urgent cases of distress and making no distinctions on the basis of nationality, race, gender,

religious belief, class or political opinions. (Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2012)

Independence relates to that:

humanitarian action must be autonomous from the political, economic, military or other objectives that any actor may hold with regard to areas where humanitarian action is being implemented. (Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2012)

NGO

Non-Governmental Organization refers to organizations where the majority are non-profit organization which, usually, are not affiliated with governments (Karns, 2020).

P5 country

“The Security Council comprises five permanent members—China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States—collectively known as the P5” (Council of Foreign Relations, 2018).

Self-interest

Self-interest is defined as to when someone makes a decision considering what is best for themselves and what advantages they will receive from that action (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.).

Strategic motives

Strategic is referred to as “helping to achieve a plan, for example in business or politics” (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.). In this thesis, this definition refers to motives executed from a strategic agenda.

3.2 Consequentialism

Consequentialism is a theory that emphasizes the consequences from an action or a choice rather than the underlying intention of that action (Graafland & Bosma, 2013, p. 615). Further, Fitzpatrick describes that from a consequentialist perspective “what makes an action good or bad depends on the effects that action engenders” (2008, p. 29). The initial intention of the action is not of relevance, but as stated earlier, the point of focus remains on the consequences. The consequences determine what is morally right or wrong through if the outcome is considered positive or negative (Fitzpatrick, 2008, p. 29). The aim is to choose the act which generates the best consequences (Howard-Snyder, 1994, p. 107). It is of importance to take both direct and indirect consequences into consideration when deciding what is morally right (Hansson, 2009, p. 53). In addition, actions which generate equally good outcomes are seen as wrong. Francis Howard-Snyder explains to not “produce less than the best consequences!” (1994, p. 107).

3.3 Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism is a “consequentialist theory” (Graafland & Bosma, 2013, p. 615) and is relatively new in comparison to the other philosophical theories. This ethical theory strives to maximize the sum of the good and is focusing on which consequence is generating the most good (Hansson, 2009, p. 34). In other words, one seeks to provide the greatest good for the greatest number of people. Dimmock and Fisher explain the theory in the following way: “we can decide what is morally wrong or morally right by weighing up which of our future possible actions promotes such goodness in our lives and the lives of people generally” (2017, p. 11). It is out of importance to note that one should prioritize its own utility as much as others. Individuals are carriers of the utility and emphasis is not put on their relationship between each other (Hansson, 2009, p. 53–54).

3.4 Deontological ethics

Deontological ethics is the main opposing theory to the utilitarian perspective. The emphasis is on duties. In addition to this, the duties are seen as the primary factors in which determine if the behavior or action is morally correct (Hansson, 2009, p. 44). According to the German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) and other philosophers in the field of ethics, the moral duties are absolute, meaning that some actions are always considered morally wrong, despite if the consequences of the action turn out to be positive (Hansson, 2009, p. 49). Hence, deontological ethics does not emphasize direct or indirect consequences. Deontological ethics also focuses on personal relationships between individuals (Hansson, 2009, p. 53–54).

Furthermore, duties can stand in conflict with each other. An example in the article is brought to attention which explains a situation where a person is on the way to a meeting but witness an accident and has to stay and call an ambulance for the injured person. Hence, the person cannot attend the meeting in time. The conflict in this case is whether the person should stay and help the injured person or attend the meeting in time. The latter mentioned duty can be disregarded, while the first mentioned duty remains (Hansson, 2009, p. 50).

3.5 Socialization theory

The socialization theory is the theory about how individuals affect each other. The socialization process can be divided into primary and secondary socialization, where they focus on different stages in peoples’ lives. Socialization is not only about how people affect each other in the physical space, media is also an important factor which affect individuals (Giddens & Sutton, 2013, p. 227). In this study, these different stages will not be investigated deeply, rather the idea of how individuals affect each other and are affected by the media, which will be applied from the organizations’ perspective.

3.6 Rational choice theory

Rational choice theory is mostly used within the field of economics but is commonly used by sociologists and political scientists as well. According to this theory, actions are essentially rational and all choices made by individuals are measured by the possible costs and benefits

before making a decision. Individuals acting out of the rational choice theory strive to achieve their goals. Since it is not achievable for individuals to always reach their goals, decisions need to be made, which is where the costs and benefits are taken into consideration. Despite how irrational an action might seem, rational choice theory argues that all social action as a whole can be explained as rational (Scott, 2000, p. 126–128).

Continuously, Scott explains that social relationships are sustained and depend on equal profitability, meaning that all sides benefit from the social relationship. However, one actor would not continue with this interaction if the profit would occur to be one-sided (Scott, 2000, p. 131).

4. Previous research

The previous research of this study consists of different peer-reviewed articles. These were found in databases such as ProQuest, Politics Collection and Scopus. In order to determine the relevance of the articles, the aim and research questions of this study were kept in mind. The articles are categorized from several identified themes.

4.1. Aid allocation and ethics

To begin with, Graafland and Bosma investigate the moral duty of development aid from Western countries to Low Developing Countries (LDCs) and focus on the reduction of poverty (Graafland & Bosma, 2013, p. 611). The authors explain this moral duty from several ethical theories. Firstly, from the utilitaristic perspective, there is a major focus on the consequences of one’s action since the basic principle regards “the greatest happiness for the greatest number” (Graafland & Bosma, 2013, p. 613). From a utilitarian perspective, the effectiveness of aid needs to be measured, as it is a way of taking the consequences into account, in order to determine whether or not aid should be allocated. For instance, if the aid is allocated to a country with an undemocratic government that would use the aid inefficiently, aid should not be allocated (Graafland & Bosma, 2013, p. 613, 615).

Secondly, the viewpoint of libertarianism is applied and emphasizes negative and positive rights. In this regard, development aid is seen as a moral duty only to some extent (Graafland & Bosma, 2013, p. 620). Further, a deontological perspective is brought to attention. From this ethical theory, wealthy countries have a moral duty to allocate development aid and they have an obligation to refrain from the current world order (Graafland & Bosma, 2013, p. 616–617). Lastly, Henry Shue and John Rawls are brought to attention and they both have a standpoint that is based on basic rights. From their view, there is in fact a moral duty from Western countries regarding development aid (Graafland & Bosma, 2013, p. 620). Another article categorized as the main focus on ethics is The Moral Politics of Foreign Aid by Hattori, who questions in what sense foreign aid can be understood as a moral practice and if there is any empirical substance to that statement. Hattori presents three different claims of ethical justifications for foreign aid within the liberal field. One of the justifications is defined as imperfect obligation and focuses on industrial states providing foreign aid considering basic

needs to developing countries, as it is viewed as a human right. Another ethical justification defines foreign aid as a response to obstacles or issues that could be solved with technical expertise, out of a moral perspective. The third ethical justification for foreign aid is to provide it for humanitarian reasons (Hattori, 2003, p. 230–231). In addition to these, Hattori investigates another perspective through his article, where he adds that foreign aid can be viewed as a social relation of giving (Hattori, 2003, p. 232) as well as beneficence (Hattori, 2003, p. 237).

4.2 Self-interest and strategic motives

Moreover, Einarsdóttir and Gunnlaugsson emphasize the ethics in the allocation of aid by conducting a literature study, with the aim to explore if there are any moral concerns taken into consideration in the allocation of aid regarding development and humanitarian needs (Einarsdóttir & Gunnlaugsson, 2016, p. 347). They begin to investigate ethical reasoning about humanitarian and development aid, starting with development ethics followed by bioethics. Development ethics is defined as “the construction of a good society, free from the potentially damaging influences of development” (Einarsdóttir & Gunnlaugsson, 2016, p. 356). A common factor for aid allocation both regarding humanitarian and development aid is donors’ self-interest (Ibid.). Herd behavior, meaning giving aid based on other countries allocation, can also affect how development aid is allocated (Einarsdóttir & Gunnlaugsson, 2016, p. 353). It is stated that ethical considerations are not considered as the main factor for allocation of aid. According to Einarsdóttir and Gunnlaugsson, self-interest has been a higher priority compared to the needs. For instance, political alliances, colonial ties, international trade, UN votes and herd behavior are different identified self-interest motives (Einarsdóttir & Gunnlaugsson, 2016, p. 356). Following the notion of humanitarian ethics, Donini, in his review of Slim’s book

Humanitarian ethics. A Guide to The Morality of Aid in War And Disaster, summarizes the

main points of the book. Donini mentions the importance of ethics in humanitarian assistance and several challenges that can occur during the practice of humanitarian action (Donini, 2017, p. 418). In correlation to the self-interest motivation behind aid (Einarsdóttir & Gunnlaugsson, 2016, p. 356), Donini emphasizes how humanitarian assistance of different kinds can be out of a political agenda, which according to Slim is a pitfall (Donini, 2017, p. 418). He presents the four humanitarian principles regulating the international law regarding humanitarian aid: humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence (Donini, 2017, p. 419; Narang, 2016, p. 192). Further, it is discussed that the humanitarian principles are used by donors and political actors as a way to gain political points or do good from the view of remaining donors. Many states and other dominant actors seem to have forgotten the purpose of humanitarian aid, in terms of ethics. Lastly, Donini points out that Slim’s book does not give answers on how to solve the ethical challenges as a humanitarian worker, but the tools which can be applied (Donini, 2017, p. 420). Additionally, in the article about forgotten conflicts written by Narang, he uses a quantitative method to investigate the following questions:

‘Which crisis areas receive humanitarian assistance?’, ‘how does recipient need affect the allocation of humanitarian aid in relation to more strategic considerations?’ and ‘does the

termination of a civil conflict cause states to put greater emphasis on strategic interests when allocating humanitarian relief, even in the face of persistent need?’ (Narang, 2016, p. 212)

Forgotten conflicts and forgotten emergencies “generally refer to conflict areas-typically civil wars-that the international community has essentially ignored or gradually neglected over time” (Fink & Redaelli 2011; Oxfam 2000; Smillie & Minear 2003, 2004 referred to in Narang, 2016, p. 190). This can occur due to the level of interest of foreign policy in the specific area. However, if the humanitarian principles are to be followed, aid should be given to the equivalence of the need by donors and humanitarian agencies (Ibid.). The aim of the study is to find empirical evidence by presenting political and strategic interests of donors in comparison to the need of recipients, rather than generate a new theory or test an existing one (Narang, 2016, p. 191). Similar findings have been found by Einarsdóttir and Gunnlaugsson (2016) and Donini (2017). Narang has chosen to divide this research by observing humanitarian aid allocated to areas with ongoing civil war and compare it to allocation to post-conflict situations. As the study is quantitative, several indicators are used. Indicators to determine political-strategic interests in this article are: oil exports, former P-5 Colony, P-5 Contiguity and P-5 “affinity”, while indicators to determine humanitarian need are: Gross National Income (GNI) per capita, infant mortality rates, life expectancy, logged number of conflict-related deaths as well as logged number of refugees and Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) (Narang, 2016, p. 200–201). It is concluded that donors’ political and strategic interests are less apparent in humanitarian aid to ongoing conflicts. However, it is shown that the aid allocated to post-conflict areas are much more strategic and political, rather than based of the needs. Hence, this leads to some conflicts being forgotten by actors (Narang, 2016, p. 190).

4.3 Media

Another aspect brought to attention by Einarsdóttir and Gunnlaugsson regarding allocation of humanitarian aid is the impact of the media and fundraising. The attention by media can influence the allocation of humanitarian aid being targeted to certain regions in a crisis (Einarsdóttir & Gunnlaugsson, 2016, p. 355). Further, Olsen, Carstensen and Høyen introduce the CNN-effect when discussing the correlation between media and allocation. The CNN-effect implies the possibility of the media to influence the policies of Western governments. They explain:

In relation to international emergency assistance, therefore, it is commonly assumed that massive media coverage of a humanitarian crisis will lead to increased allocations of emergency funds, whereby humanitarian needs have a better chance of being met. (Olsen, Carstensen & Høyen, 2003, p. 110)

4.4 Ethical dilemmas

Bell and Carens bring different ethical dilemmas of human rights and by humanitarian NGOs to attention. They used a qualitative method by observing a two-day workshop where both representatives of different human rights and humanitarian International Non-Governmental Organizations (INGOs) as well as different academics and practitioners attended (Bell &

Carens, 2004, p. 301). The purpose of this study is to identify what dilemmas can occur for INGOs in foreign lands and how to manage and adapt to these (Bell & Carens, 2004, s. 303). The following dilemmas were identified:

[...] (1) conflicts between human rights principles and local cultural norms; (2) the tension between expanding the organizations mandate; (3) whether and how to collaborate with less-than-democratic governments; and (4) the ethical limits of fundraising. (Bell & Carens, 2004, s. 301)

Additionally, Stein describes different challenges and dilemmas for NGOs working within complex humanitarian emergencies as well as their implication for conflict resolutions. Some of the dilemmas and difficult tasks that humanitarian NGOs are faced with is the fact that humanitarian aid and relief can worsen conflicts, instead of solving them. In addition, another dilemma regards delivering humanitarian relief and assistance during civil wars, which at times can be challenging. As civilians become targets in civil wars, it is more difficult for humanitarian workers to keep them protected (Stein, 2001, p. 20–21). Another challenge is the fact that resources from humanitarian NGOs can end up in the hands of actors other than the indented target group (Stein, 2001, p. 28). Although the practices of NGOs have received some criticism, there have been actions taken in order to improve the work. Many international humanitarian agencies have for instance adopted the Code of Conduct for the International Red Cross movement and NGOs in Disaster Relief as well as to some technical standards which are related to delivery of food aid and water, by the Steering Committee for Humanitarian Response (SCHR). In addition, NGOs have developed models regarding the assessment of needs which take several factors into account (Stein, 2001, p. 31).

Wood and Sullivan explore some possible negative effects that humanitarian aid can cause in a context of civil conflict. They are studying this from two perspectives: first, they observe if humanitarian aid can cause one-sided violence towards civilians from rebels, and second, if it can be caused by the government (Wood & Sullivan, 2015, p. 1). The study is quantitative and the used data is from post-cold war African countries. Several different variables were used in order to test the hypotheses as well as examine the data from different perspectives (Wood & Sullivan, 2015, p. 11–12). The results of their study show clear patterns that the risk of increased violence by rebel groups against civilians occur in areas where humanitarian aid is allocated. However, it was not as apparent in the situation regarding violence from the government (Wood & Sullivan, 2015, p. 21). In addition, the fact that humanitarian aid and assistance can contribute to conflict is brought to attention by Stein who exemplifies this with the situation of Rwandan refugees in Zaire after the genocide. In this case, despite the presence of humanitarian NGOs and the United Nations, “perpetrators of the genocide had re-imposed authority over hundreds of thousands of refugees” (Stein, 2001, p. 20). It has also been seen that there is a risk for renewed conflict through the relief provided by the NGOs (Stein, 2001, p. 27). When such situation occur that the humanitarian aid contributes to conflict, Stein states that withdrawal should be considered, which raises questions regarding ethics, strategy and operations. Withdrawal has occurred in cases where infrastructure has been destroyed or when NGO staff have been harmed or put at risk. Another way of withdrawing can be of more

strategic importance, such as a case in eastern Zaire in 1994 (Stein, 2001, p. 35). The NGOs who withdrew did it due to bad security conditions in the area as well as in order to put “pressure on the international community to respond to the security dilemma” (Stein, 2001, p. 36).

5. Method

The chosen method for this study is a qualitative method. With a qualitative study, it is possible to achieve a deeper understanding of certain topics. Semi-structured interviews were conducted and the interviewees are then able to express their thoughts and knowledge more. This is not possible to the same extent with the use of a quantitative method, for instance in a survey, with fixed answers. Since this study aims to fill a gap of knowledge, a qualitative method is commonly used in cases where there is a lack of knowledge as well as unanswered research questions (Hjerm, Lindgren & Nilsson, 2014, p. 149). In addition, the use of a qualitative method contributes to rich information about the chosen topic that is being studied, rather than generating results that can be generalized, which is not the aim of this study (Bryman, 2011, p. 372).

There are several kinds of qualitative methods which, according to Bryman, are common to combine in a qualitative study. For instance, qualitative interviews, focus groups, observations and analysis of documents are methods usually combined (Bryman, 2011, p. 344). However, due to time limitations, one method to collect data was chosen in this thesis. The interview questions were formulated in advance, hence, they were structured and asked to all participants. Semi-structured interviews also allowed for flexibility since open questions were asked to the participants (Hjerm, Lindgren & Nilsson, 2014, p. 150) and the interviewers can ask follow-up questions to important topics that are brought to attention as well (Bryman, 2011, p. 260). When the same questions are asked to all participants, it facilitates the process of analyzing and comparing the results. The validity of the study is increased as the interviews are prepared and structured in advance (Hjerm, Lindgren & Nilsson, 2014, p. 150–151).

Although it was challenging to find participants due to the current situation with Covid-19, a satisfactory number of participants was found. However, if this would not have been the case the qualitative method of policy analysis could have been applied to complement data from the absent participant(s).

5.1 Limitations

Although a qualitative method is considered as the most suitable for the purpose of this study, there are limitations within this method. As mentioned earlier, due to the small number of participants, the results of a qualitative study are difficult to generalize. These are not representative for the whole field of study. Another limitation is that qualitative studies are, due to their lack of structure in most cases, difficult to replicate in comparison to a quantitative method. Difficulty in replication can also be due to the fact that the researcher is the one determining what data is of relevance. A lack of transparency considering the researcher’s

process during the study is also a common limitation (Bryman, 2011, p. 368–370). While being conscious of these limitations, the authors of this study aim to be transparent by explaining every step the process thoroughly, in order to increase the possible ability to replication as well as increase the dependability, in correspondence with reliability (Bryman, 2011, p. 355). Further, the aim of the study as well as the research questions were considered when collecting the data. Considering the small number of participants, as mentioned earlier, there will not be a possibility to generalize the study. However, since the aim is to achieve a deeper understanding, generalization was not the intention.

5.2 Sampling

For this study, a purposive sampling has been applied. This means that the actors are chosen out of relevance of the research questions. A purposive sampling has two levels of sampling, firstly, organizations are chosen, secondly, individuals within the organizations are selected out of the most appropriate position regarding the topic (Bryman, 2011, p. 350–351). In order to receive more interviewees, a snowball sampling was applied in two cases. Snowball sampling is when an already chosen interviewee refers to another relevant person within the field who possibly can participate in the study. Hence, the sampling is not random nor representative (Bryman, 2011, p. 196–197). Despite this, a snowball sampling was advantageous for this study since it provided with experienced interviewees within the related field.

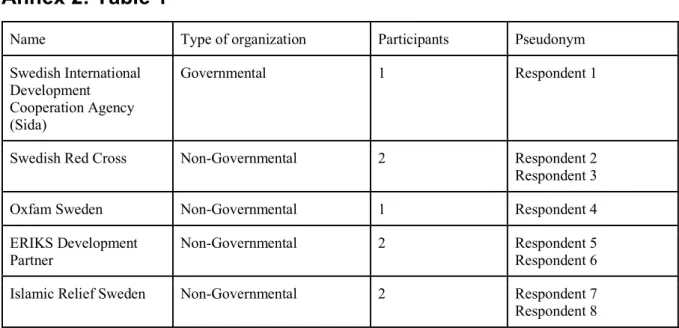

Seven organizations working with, among other things, humanitarian aid in conflict-affected areas were initially contacted by email found on their official webpages. Due to a lack of responses and the limited time-frame, the organizations were also contacted by phone. A total of eight people from five organizations were interviewed, one of which was a governmental organization and the remaining were NGOs. In all cases, except for one, the interviews were conducted individually. The two respondents that were interviewed together elaborated and complemented their answers well. Hence, the joint interview did not cause any obstacles. All respondents remain anonymous and the information is treated with confidentiality. The respondents were informed of the purpose of the research both when they were initially contacted and before the start of the interview. Hence, the ethical claims of information and confidentiality were respected. In addition, the received information by the participants will solely be used for the scientific purpose (Bryman, 2011, p. 131–132). The organizations and number of participants are presented in the table below.

Name Type of organization Participants Pseudonym Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) Governmental 1 Respondent 1

Swedish Red Cross Non-Governmental 2 Respondent 2 Respondent 3 Oxfam Sweden Non-Governmental 1 Respondent 4 ERIKS Development

Partner

Non-Governmental 2 Respondent 5 Respondent 6 Islamic Relief Sweden Non-Governmental 2 Respondent 7 Respondent 8 5.3 Collection of data

In order to collect the data in this study, phone interviews and video calls were conducted. These were chosen due to several reasons. The main reason was because of the current situation regarding the virus Covid-19 and the recommendations from the Swedish authorities. Due to this, phone interviews were, in terms of effectiveness both in relation to the time-frame and cost, advantageable. The main advantage with video calls is the possibility to observe the facial expressions, reactions and gestures by the interviewees, which is a difference compared to phone interviews, where neither of these are possible to observe (Bryman, 2011, p. 432–433). In this study, two phone interviews were conducted either because technical difficulties or the interviewee’s preference. The rest of the interviews were video calls. The length of the interviews were between 30 minutes to one hour. Due to the fact that the thesis is written in English, the respondents were asked if the interviews should be conducted in English or Swedish. All respondents agreed to conduct the interviews in English. The fact that there could be a significant language barrier when conducting interviews in a second language was a possible risk that was kept in mind. However, all the respondents were highly skilled and no issues or misunderstandings occurred during the interviews. By conducting the interviews in English, the transcription process was facilitated as translations did not need to be made. In summary, since no misunderstandings or translation occurred, the validity did not decrease. Furthermore, to increase the validity, an interview guide was made since it creates a structure, which in turn increases the validity (Hjerm, Lindgren & Nilsson, 2014, p. 150–151). The questions used for the interviews were a number of 18. The reason for the number of questions was because one of the organizations only could participate if it was a maximum of 20 questions. The authors found this reasonable since there was a high need of participants. Throughout the interviews, additional follow-up questions were asked if needed. The interview questions were primarily based on the research questions, the aim of the study, as well as theories and previous research mentioned in this study. The first two questions were introduction questions used for creating a comfortable setting for the participants (Hjerm, Lindgren & Nilsson, 2014, p. 156). The following questions were all of relevance for the

research questions and were categorized in relation to ethical theories and previous research which created a logical order which contributes to the validity (Hjerm, Lindgren & Nilsson, 2014, p. 157). Due to the fact that the research questions, the purpose as well as previous research and theories have been taken into consideration when formulating the interview questions, there is an increased possibility to reach an increased validity of the study, since the information measured is relevant for the study (Bryman, 2011, p. 352).

5.4 Recording and transcribing

All interviews were recorded with consent from all participants who were asked and informed before starting the interview. Hence, the ethical claim of consent was respected (Bryman, 2011, p. 132). The interviews were also transcribed. By recording and transcribing the interviews, it is possible for the authors to remember both what was said and how it was said. In addition, it facilitated the analysis (Bryman, 2011, p. 428).

5.5 Analysis of data

As mentioned earlier in section 5.3 Collection of data the interview questions were based on the chosen theories in the study, previous research, aim and research questions. After transcribing all of the interviews, the material was coded widely with these as a point of departure. A thematic analysis was applied in order to systematically find common themes from the data. Initially, longer passages from the transcribed interviews were coded in order to create broader thematic categories (Hjerm, Lindgren, Nilsson, 2012, p. 56). These categories and codes were all related to the research questions, previous research, aim as well as theories of this thesis. Moreover, when the identified codes started to appear in a significant pattern, broader themes and relation between these could be found from the data (Hjerm, Lindgren, Nilsson, 2012, p. 63). To facilitate the process of analyzing the data, the transcriptions were color-coded. Each color, which represented a theme, was organized into separate folders. These themes are used as the foundation of the result as well as of the analysis. In order to concretize and strengthen the presented empirical findings, quotes from the respondents have been used throughout the result and analysis.

6. Result and analysis

In order to answer the research questions, a total of eight interviews were conducted with five different organizations. The interview questions are based on theories, previous research, the purpose of the study as well as research questions. The results are presented below in themes that have been categorized from the coding process of the data.

6.1 Ethics regarding allocation

The results indicate that all organizations use ethical frameworks of some sort regarding allocation of humanitarian aid to conflict-affected areas. Respondent 1 explains that:

[...] the principles for the allocation of humanitarian aid, which you mention later in your questions, are of course the humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence, so that’s what guides our work as well as humanitarian law. (Respondent 1)

The rest of the respondents also emphasize their use of the humanitarian principles in their work and especially in the allocation of humanitarian aid. Respondent 1 exemplifies that these principles are what guides their humanitarian allocation, as well as life-saving and needs-based priorities. The fact that the humanitarian aid should be needs-based is a common factor stated among all the respondents. According to Respondent 3, the humanitarian principles are the “cornerstone of everything we [the organization] are” and what they stand for. These humanitarian principles align with Hattori who explains that one ethical justification to allocate humanitarian aid is due to humanitarian reasons (2003, p. 130). In addition, several factors which facilitate the allocation of humanitarian aid to conflict-affected areas, according to the respondents, are available resources, access to the conflict-affected area and the safety level in the area. However, the use of the humanitarian principles expressed by all respondents, does not align with Donini’s statement, who claims that the humanitarian principles are used with an agenda to gain political points or do good from the view of the remaining donors (2017, p. 420).

The application of the Red Cross Code of Conduct is mentioned by Respondent 2, Respondent 5 and Respondent 7, which aligns with Stein’s research (2001). Respondent 2 explains that this Code of Conduct implies ethical behavior of the staff. The Sphere standards “define the minimal applicable forms of support in various situations that can be offered in a humanitarian intervention” (Respondent 3) which Respondent 3, Respondent 6 and Respondent 7 state are used in each organization they work for. Another common ethical guideline for Respondent 5, Respondent 6 and Respondent 7 is the Core Humanitarian Standards (CHS).

As stated above, all respondents express that the allocation of aid is based on needs and the humanitarian principles. Similar answers are expressed in the question of an ethical dilemma regarding two conflict-affected areas in need of humanitarian aid where the organization only have the ability to deliver humanitarian aid to one of the areas. One exception where need is not the primary factor for allocating humanitarian aid is expressed by Respondent 4, who says that the aid allocation also depends on the donors and where they demand the aid to be allocated. Respondent 1, Respondent 2 and Respondent 3 state that they allocate aid to both conflict-affected areas that are in need. However, Respondent 5, Respondent 6 and Respondent 7 explain that they prioritize the area where the need is more urgent. Respondent 7 says that they do a “comparison [of] people in need in both locations, not only in need but severity of the needs”. These respondents also mention despite their limited resources, they still try to make an effort in both areas. One aspect where the organizations differ is the fact that Respondent 5 and Respondent 6, working for ERIKS Development Partner, are in general only active in places where they “already have an established partner” (Respondent 5), similar to Respondent 1 who explains that “we allocate funding to an implementing partner or agency”, which for instance can be NGOs. Reflected in these answers from the respondents are the humanitarian principles which, again, are humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence.

Since these principles are guiding the decision-making in this ethical dilemma, it is possible to connect this to deontological ethics. More specifically, the humanitarian principles can be seen as duties from the perspective of the organizations, since the majority of the respondents would either support both conflict-affected areas or prioritize based on needs. The needs are based on the humanitarian principles, leading the organizations to aspire to allocate and assist in the other place as well. A further connection to deontological ethics is the general importance of the humanitarian principles for each organization which is emphasized by all respondents. Both situations show that these are duties that are aspired to be obtained, since, perhaps it could be morally wrong to support one area but not the other due to the principles of neutrality and impartiality.

According to Stein (2001) as well as Wood and Sullivan (2015), as mentioned in the previous research, humanitarian aid can have negative impact by worsen an existing conflict. In order to prevent this from occurring, Respondent 5 and Respondent 7 express the use of the Do-No-Harm principle as an approach, which aims to make sure “not to contribute on enhance any conflict” (Respondent 7) or worsen a situation in any way. Similarly, Respondent 1 and Respondent 7 mention that the organizations use a conflict perspective, which includes conflict sensitive aid which refers to that “the aid should not worsen or enhance tensions or split societies that may lead to conflict or exaggerate an ongoing conflict” (Respondent 1). This conflict perspective is in line with the humanitarian principles and it is out of importance to follow them. In order to do this, Respondent 1 explains that specific questions “needs to be answered when it comes to conflict sensitivity so the aid does not interfere the ongoing tensions or conflicts in the area where it’s delivered”. Respondent 7 elaborates further by explaining that in addition to this, the organization uses a risk management plan which includes risk analysis of possible outcomes by their own interventions and external risks. Respondent 6 also emphasizes the importance of a complex analysis, stating that it is necessary both in the planning phase and continuously throughout a project for the humanitarian intervention. It is also of importance to have a local anchoring by involving local partners due to their knowledge of the context and actors, which can help ensure that the intervention is not provoking anyone, but rather building inclusion. In alignment to this, Respondent 4 expresses that a proper analysis of the situation is conducted and the acknowledgements are taken into account. By focusing on the local context, the organizations take a common dilemma stated by Bell and Carens into consideration regarding the conflict between human rights principles and local cultural norms (2004, p. 301). It becomes a way to mitigate conflicts between the organizations and the local actors which are involved.

Moreover, Respondent 3 states that to not enhance a conflict they are working within is a constant effort and often a dilemma that the organization is confronted with. In contrast, the common dilemmas among NGOs mentioned by Bell and Carens (2004), were not found in the answers from the respondents. Despite this, the respondents thoroughly discuss ways in which they deal with the dilemma of not enhancing a conflict through the allocation of humanitarian aid. To deal with the dilemma of not fueling a conflict, Respondent 3 refers to the fundamental principles which include the humanitarian principles. In addition to this, the Geneva Conventions are mentioned as well as the organization constantly having negotiations with

involved actors and explains the importance of a written agreement with the different parties involved in the conflict. Risks and threatful situations are anticipated and the organization tries to mitigate them, however Respondent 3 explains that “it’s not always easy”.

Additionally, Respondent 2 explains the use of different methodologies, such as the Better Programming Initiative. This methodology aims to question different actions before implementing them both in order to prevent and predict the outcomes of that intervention. Respondent 2 stresses that this is in order “to make sure we don’t introduce anything worse” (Respondent 2). Through the questions asked during this programming, the aim is to generate the best outcome. Hence, this methodology could be closely connected to consequentialism. As explained in the theory section of this thesis, consequentialism is an ethical theory which focuses on which consequence of an action is generating the best result (Howard-Snyder, 1994, p. 107). Since the goal in this situation is to ensure that humanitarian aid is not worsening the conflict, which is done through anticipating the best consequences, a connection to the rational choice theory can be made, since it focuses on the action of reaching the goals. As shown in the results above, all respondents have demonstrated different methodologies and principles where they weigh and try to predict consequences of their interventions to reach a positive impact not to enhance the conflict they are active within. These approaches were all brought to attention by the respondents when explaining how each organization take possible consequences into account when allocating humanitarian aid. For instance, the Do-No-Harm principle is expressed as an approach to not worsen the situation or enhance a specific conflict by Respondent 5 and Respondent 7. Similarly, the use of conflict-sensitive aid as explained by Respondent 1 and Respondent 7, has a common aim to prevent worsening and negative outcomes through asking certain questions as Respondent 1 says, which is equivalent to the approach in the programming explained by Respondent 2. Another common approach to not worsen the situation in a conflict-affected area, correspondingly to the theory of consequentialism, is through anticipating and mitigating the risks (Respondent 3) or to implement a risk analysis of possible consequences (Respondent 7), or as Respondent 4 and Respondent 6 state, doing a complex analysis both throughout the planning process as well as during the intervention. Respondent 2 highlights the importance of taking “unintended consequences” into account before allocating humanitarian aid. In situations where unintended negative consequences can occur, the organization aims to measure these in order to prevent these from occurring. In addition to this, the organization has established standard operating procedures, meaning that:

[...] whenever a conflict flares up we would have task force with known people getting together which will conduct a rapid analysis of the situation and this analysis will determine whether we should go in or not. (Respondent 2)

In this analysis, questions of one’s actions are always asked and elaborated continuously throughout the project. Likewise, this type of analysis can correspond with consequentialism due to the emphasis on consequences in order to decide what is morally right. Indirect consequences are important to take into consideration from the consequentialist perspective as well (Hansson, 2009, p. 53) which is apparent in the reasoning about unintended consequences

by Respondent 2. In addition, other instances to assure humanitarian aid has a positive impact can be to make assessments, according to Respondent 1 and Respondent 7, which aligns with previous findings by Stein (2001). Respondent 1 explains that “we [the organization] make the assessments and do the follow up and try to ensure its and that people are benefiting” to confirm that the humanitarian aid contributes to its purpose. Both Respondent 5 and Respondent 7 are focusing on a long-term perspective when linking the humanitarian aid to the outcomes such as rehabilitation and development. In addition to these, Respondent 7 adds that “Result Based Management, is a key tool we [the organization] also use for assessing the positive outcome”. Respondent 6 explains that in order to have a positive impact, a thorough analysis of the context, different actors, target group, the existing structure in the area, needs and the root causes of the problem are all aspects necessary to consider. Respondent 2 agrees with the importance of involving the target group in order to achieve a positive impact. Another aspect brought to attention by Respondent 4 is monitoring and sending an external auditor that observes that the humanitarian aid is used for its purpose. The achieved information about positive impact in this section relates to the aim of consequentialism, which is to choose the act which generates the best consequences (Howard-Snyder, 1994, p. 107), since assessments, follow ups, Result Based Management and context analysis are conducted in order to achieve the best possible outcomes by ensuring that the humanitarian aid has a positive impact. In connection to that humanitarian aid could worsen a conflict, Stein raises the fact that donors should consider withdrawal of the allocated aid, in order to not worsen the situation (2001, p. 35). This is a widely discussed ethical dilemma among the respondents. The most common factor for withdrawal of humanitarian aid among the respondents is the security level for the employees, as Stein (2001) points out in her article as well. Respondent 3 explains that the security level refers to threats of such nature that the lives of the employees are put at risk. Respondent 5 agrees and adds that the “security for our target group” is taken into consideration. Another reason for withdrawal is mentioned by Respondent 7, who says that if the humanitarian principles are compromised then that would create a challenging situation which would lead to withdrawal. In addition, interference of aid delivery or aid diversion as well as non-access would make it more difficult for the organization to support the conflict-affected area. The fact that the organization are likely to withdraw if the humanitarian principles are not followed can again connect to deontological ethics since the organization clearly show their standpoint and to what extent they relate to the humanitarian principles. Therefore, it appears as a duty to follow the humanitarian principles, considering that the organization would rather withdraw humanitarian aid than to compromise these principles. In contrast, two of the respondents, Respondent 1 and Respondent 2, express that the organizations they work for do not consider withdrawal in these instances but rather either lower the activity and adapt to the situation or put the allocation on hold. Continuously, they mention that in a situation where aid is constrained due to external factors in the conflict, diplomacy and negotiation are used to have a dialogue in order to find solutions for humanitarian aid to still be able to be delivered.

6.2 The dilemma of self-interest and strategic motives

One of the major findings in the previous research is that allocation of aid is based on self-interest and strategic motives rather than needs (Einardóttir & Gunnlaugsson, 2016; Donini, 2017; Narang, 2016). In contrast, the result of this study shows the opposite. Self-interest and strategic motives did not appear to be significant for the respondents when allocating humanitarian aid. Respondent 1 states that since the organization is governmental, they allocate where the government is steering them without any self-interest, according to themselves. Respondent 1 put emphasis on that “It's no contest for us, we just do what we are told”. However, the general interest as well as the policy of the government are likely to affect the decision-making of the allocation made by Sida, though this is not expressed by the respondent. As mentioned earlier by Respondent 1, the allocation of aid is based on needs, life-saving and the humanitarian principles. Respondent 6 agrees and adds that ERIKS Development Partner has steering documents to avoid self-interest in their allocation. While Respondent 4 expresses that self-interest should be avoided in the allocation, it is also acknowledged that it can be a challenge to not be affected by it at times. Respondent 4 continues and explains how self-interest can become dominant in some situations, where the funding is bigger than the needs. In these situations, it is explained that some organizations decline more funds from the donors, while other organizations use the additional funding for other motives than support, “just to get rid of the money” (Respondent 4).

Furthermore, Respondent 4, Respondent 5 and Respondent 7 all mention strategic funding aimed towards certain crises where there is a major need. Respondent 7 exemplifies with the crisis in Yemen where the situation continues to worsen, as a result funding has increased. Another aspect is brought to attention by Respondent 2, Respondent 3 and Respondent 7, which is added value of each organization. Added value refers to use the area of expertise that the organization may have and uses in places where there is a need. In order to achieve the best results as well as to avoid duplication, it is important to coordinate with different actors active in the conflict-affected area. While these examples show a certain type of self-interest and strategic motives, it does not correspond with previous research which for instance highlight colonial ties (Einarsdóttir & Gunnlaugsson, 2016) and a political agenda as strategic motives (Donini, 2017; Narang, 2016). Respondent 2 expresses that:

So for example, if Swedish Red Cross, if we have an added value in a post-conflict area, that's where we can take part. So, in that sense, we don’t have to make those choices. We coordinate amongst each other. We look at who is best placed to do work in a certain place and who can add value in another place. And how can we coordinate and to have good synergies together. (Respondent 2)

Respondent 4 continues and explains how the organization is affected by other actors:

It’s affected in a good way because when you look at the humanitarian situation, you come together and you support each other. So where you are in a situation where you got several organizations you divide the tasks into the organizations doing what needs to be done, and what

they do best and that you manage that situation, the skills in the organizations in the best way possible so that you can help the most people possible. (Respondent 4)

Hence, coordination and added value are connected in the way that it does not appear to be a competition or one-sided interests between the different organization active in the area but rather cooperation. This aligns with Scott’s explanation about social relationships within the rational choice theory. Continuously, he describes these relations to depend on equal profitability, focusing on that all sides benefit from the relationship (Scott, 2000, p. 131). In this scenario, added value can be seen as a situation of equal profitability, where all actors are able to contribute with knowledge from their area of expertise. In addition, strategic funding is not seen as a strategic motive or an act of self-interest, since allocation is based on needs. Moreover, in his study, Narang concludes that strategic and political allocation are more common in post-conflict areas than in ongoing conflict areas where needs are prioritized (2016, p. 190). Narang’s conclusion does not align with the result from the respondents. Respondent 1 clearly states that there is “no real difference” regarding the allocation from the organization to ongoing conflict areas or post-conflict areas. International humanitarian law and the humanitarian principles are both crucial in guiding the allocation of humanitarian aid to ongoing conflict areas as well as post-conflict areas. Similarly, Respondent 7 expresses that “In both cases, humanitarian principles are the starting point”. However, Respondent 5 highlights another perspective where the major difference between an ongoing conflict area and a post-conflict area is the security issue, which is more central in an ongoing conflict. Despite the situation, Respondent 5 states the importance of understanding the conflict and context, as well as ensuring that no harm is being done that would worsen the conflict.

In addition, the priorities to a post-conflict area differs from an ongoing conflict area, according to Respondent 3, Respondent 4 and Respondent 7. They explain that the humanitarian aid allocated towards an ongoing conflict area is focused on the needs and life-saving, while aid allocated to a post-conflict area is more focused on reconstruction, resilience and a long-term development in order to strengthen the conflict-affected communities which prevent the conflict to occur again. Respondent 7 concludes “In short, [in] post-conflict we are looking little more long-term humanitarian response”.

Additional tools to prevent a conflict to reoccur presented by the respondents are the use of conflict-sensitive aid (Respondent 1, Respondent 7), conflict analysis, Do-No-Harm principle, elements of peace building and engagement with local actors (Respondent 7). Similarly, Respondent 4 states that empowerment of the locals is important to build up the economic status of the area. Respondent 6 agrees with the importance of involving local actors, and explains:

I would say that I think that what we really need to take into consideration is that we work through the actors and through the already existing structures as much as possible that we try not to create parallel systems that would then deteriorate as we leave or would. Or yeah, people wouldn't really embrace. (Respondent 6)

Continuously, Respondent 5 has another view, stressing the importance of understanding the specific conflict and context in order to prevent a conflict from recurring. Meanwhile, Respondent 2 explains, as mentioned in section 6.1 Ethics regarding allocation, that the organization uses methodologies, specifically named Better Programming Initiative, where certain questions asked, Respondent 2 elaborates further:

[...] you ask certain questions throughout the programming. Like, okay what’s the geographic place of the well? Has that any meaning to certain groups of people, will they meet there? Could it be a fact that people meet at the well, that it contributes to peaceful acts, or will it be a divider? So we look at such aspects all the time. (Respondent 2)

In contrast to Narang’s (2016) conclusion regarding strategic and political allocating to post-conflict areas, the statements from the respondents show the opposite. More specifically, the result shows that the difference between allocating humanitarian aid to a post-conflict area and to an ongoing conflict area rather has to do with different priorities in the situations, due to the circumstances they are in. For instance, these circumstances could be life-saving and needs-based priorities in an ongoing conflict, or a focus on reconstruction and development in a post-conflict situation. In addition, the use of different principles and methodologies, such as the Do-No-Harm principle and conflict analysis, also indicate the opposite of Narang’s conclusion, since the organizations are thorough and transparent in their allocation. Hence, there is no sign of any strategic interest based on the statements of the respondents.

6.3 The power of the media

Within the humanitarian sector, it is common to work closely in relation to other donors. As stated by Einarsdóttir and Gunnlaugsson, herd behavior, meaning giving aid based on other countries allocation, can affect how humanitarian aid is allocated (2016, p. 357). Allocation based on other factors than needs can raise questions in terms of ethics. However, Respondent 1 explains that the humanitarian aid is needs-based and as the organization is governmental, it is not “approached by other donors” affecting their decision of where to allocate. Though, Sida is working in a close partnership with the United Nations, more specifically the Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). OCHA has mandate to coordinate aid, however the assessment is done by Sida before the allocation.

The statements by the respondents from the NGOs differ in the sense that Respondent 6 and Respondent 7 state a risk of duplication of humanitarian aid and resources if there is a lack of cooperation between the organizations active in an area. Respondent 8 agrees and says “we don't want duplication of our efforts”. Another issue brought to attention is instances where organizations are not following the humanitarian principles, stated by Respondent 2 and Respondent 7. This creates a situation where NGOs might be generalized for a mistake made by another actor. Respondent 2 exemplifies:

I mean, if they [another organization] do something wrong, in the minds of people they might not, even in the area where we work, they might not differ between that organization and the Red Cross, so yeah, it affects us immediately. (Respondent 2)

Respondent 4 explains another perspective by highlighting cooperation between organizations where tasks are divided among them in a humanitarian intervention which can be a positive aspect.

Furthermore, as shown, herd behavior does not appear among the respondents as they all express that they are not affected by other donors when allocating humanitarian aid. On the contrary, Respondent 3 stresses that the organization tends to intervene in areas where less actors are already active since Respondent 3 states that “as a matter of fact we tend to go where no one is going”. In connection to the socialization theory which regards the way individuals affect each other (Giddens & Sutton, 2013, p. 227), the result points in another direction showing that all the organizations tend to allocate humanitarian aid based on the needs which connect to the humanitarian principles that all respondents state is guiding their allocation. In addition, from the socialization theory, you can derive that people are affected by media and can be socialized by media (Giddens & Sutton, 2013, p. 227). As Einarsdóttir and Gunnlaugsson point out, media can influence the allocation of humanitarian aid, more specifically where it is allocated (2016, p. 355). The dilemma about media attention is acknowledged by several respondents. Similar to Einarsdóttir and Gunnlaugsson (2016), Respondent 8 emphasizes that media attention definitely has an impact on allocation of humanitarian aid. Some global crises receive more media coverage, hence the information reach more people and the public funding increase. In contrast, other crises become under-supported as a result of less media attention. Respondent 2 and Respondent 4 agree on that the media attention facilitates the fundraising from the general public. In addition, the CNN-moment “implies the possibility of the media to influence the policies of Western governments” (Olsen, Carstensen & Høyen, 2003, p. 110) hence, increasing the allocation of humanitarian aid (Ibid.). Respondent 4 brings the CNN-moment to attention and stresses a positive aspect of the CNN-effect:

In charities you talk about CNN-moment, when the disaster becomes world news, and when that disaster becomes world news, generally you’re able to appeal for money and more access to government money, and you’re therefore more able to help. So often, one of the first things an organization will do is to highlight the problem that is existing and also to make sure people in the West are able to see it. (Respondent 4)

As a result, the organization is able to increase its resources and thereby help more people in need. However, Respondent 4 raises the issue in correlation to this instance by expressing how only certain conflicts that are of significance in the West receive more media coverage, while other crises remain unacknowledged. Though, Respondent 2 stresses that: