Science Park Jönköping and its Potential

Future Ownership Structure

A Report on the Feasibility of Adding Business Collectives as a Third Owner

Authors: Jan Domelid, Eric Litton, & Charles Prator

Tutor: Bengt Johannisson

1

A b s t r a c t

Background: Science Park Jönköping (SPJ), a well established incubator in Sweden and

with close ties to the university, is interested in adding a third owner into their mix, and they are focused on the business collectives: Handelskammaren, Företagarna and Svenskt Närlingsliv. In order to satisfy this idea SPJ needed to understand their stance in the busi-ness community to pull this off. And, the authors research and surveying are the prelimi-nary steps in achieving this goal.

Purpose: The authors plan to aid SPJ in their objective of attracting local business

collec-tives: Handelskammaren, Svenskt Näringsliv, and Företagarna, as a stakeholder and co-owner in SPJ. This will be done in a three parts: by profiling their awareness and thus find out if SPJ is mature for taking the necessary step in approaching the business collectives.

Theoretical Framework: The theoretical framework can be divided into the following

areas: a general overview of science parks and incubators and what their processes entail, supplementation through relevant and similar cases around the world, a strategy encom-passing the direction SPJ take with the compiled information found in this thesis.

Method: This thesis focuses on compiling incubator case information and performing our

own survey to form a general conclusion for SPJ in regards to their profile or stance con-cerning the aforementioned goal. This has been done through looking at previous research in the specific area of ownership inside incubators and in combination with a survey of 30 companies and interviews with representatives of their organizations in the Jönköping re-gion concerning the addition of a third owner to SPJ.

Conclusion: Surprisingly to the authors, the results showed that a dominant part of the

Jönköping business community is in favor of establishing an owner relationship between SPJ and the local business collectives, and that no respondents disagreed with such an initi-ative. The authors findings show that there are synergies that can bee seen in such a co-operation, hence linking new ventures and innovative ideas with the already established en-terprises in the region. Nevertheless, interviews with the targeted business collectives state the complexity of such a task. Hence, the authors have suggested a direction advising that SPJ can move forward not with the initial scope of adding the business collectives as a co-owner but with the suggestion that they instead focus in co-operating closer and hence reaching their common goals of creating a better business climate in Jönköping, thus in-creasing the overall efficiency of new innovations and developments within the Jönköping region through a stronger co-operation between new ventures and already existing and well established companies in need of new innovative ideas and developments.

2

Acknowledgements

As authors of this thesis, we would like to acknowledge certain people that, without their help, made our work possible:

Science Park Jönköping for providing us the opportunity to work on this project. The companies who graciously donated their time in taking part in these surveys. Our fellow students and our tutor provided us with feedback and advice during the process.

Finally, our families whose support and advice made this possible.

Jan Domelid Eric Litton Charlie Prator

Jönköping International Business School Fall 2009

3

Ta b l e o f C o n t e n t s

1

Introduction ... 5

2

Purpose ... 7

2.1 Discussion of Problem ... 7 2.2 Delimitations ... 9 2.3 Definitions ... 92.4 Outline of the thesis ... 12

3

The Empirical Context of the Study – SPJ ... 13

3.1 Science Parks as a Phenomenon ... 13

3.2 Science Park Jönköping ... 14

3.3 Notes from a Conversation with Dan Friberg ... 15

3.4 Region of Jönköping ... 16

4

Frame of Reference ... 18

4.1 A Background on Science Parks ... 18

4.2 Ownership and Financing ... 20

4.3 Awareness as an Additional Concept ... 23

4.4 Strategy Theories Applicable for SPJ ... 25

4.5 Summarizing Frame of References ... 28

5

Method ... 29

5.1 Research Approach ... 29

5.1.1 Quantitative vs. Qualitative Research ... 30

5.2 Data Collection ... 32

5.2.1 Contact Database Information and Compilation ... 32

5.2.2 Telephone Interviews ... 33

5.2.3 Reasons for Choosing Sampling Strategy ... 33

5.2.4 Reasons for Choosing our Method ... 34

5.2.5 Survey Design and Execution ... 34

5.3 Validity, Reliability, & Credibility of our Surveying ... 38

5.3.1 Sampling Strategy ... 38

5.3.2 Chosen Method ... 38

6

Empirical Findings ... 42

6.1 Quantitative Data Collection ... 42

6.2 Voices of the Companies ... 48

6.3 Interviews with the Business Collectives ... 50

6.3.1 Företagarna in Jönköping ... 50

6.3.2 Handelskammaren in Jönköping ... 51

6.3.3 Svensk Näringsliv in Jönköping ... 51

6.3.4 Notes from Interview with Marc Nathan ... 51

4

7.1 Strategic Implications of SPJ ... 55

7.1.1 Where should SPJ be Active? ... 55

7.1.2 Where should SPJ Focus? ... 56

7.1.3 How Can SPJ Reach the Companies? ... 57

7.1.4 Feasibility of Adding the Targeted Organizations as Owners of SPJ 58 7.2 Concluding Recommendations ... 59

8

Conclusion ... 62

9

Discussion ... 1

10

Appendix ... 2

10.1 Science Parks Statistics from 2008 ... 2

10.2 Survey Questionnaire Swedish ... 3

10.3 Survey Questionnaire (English) ... 4

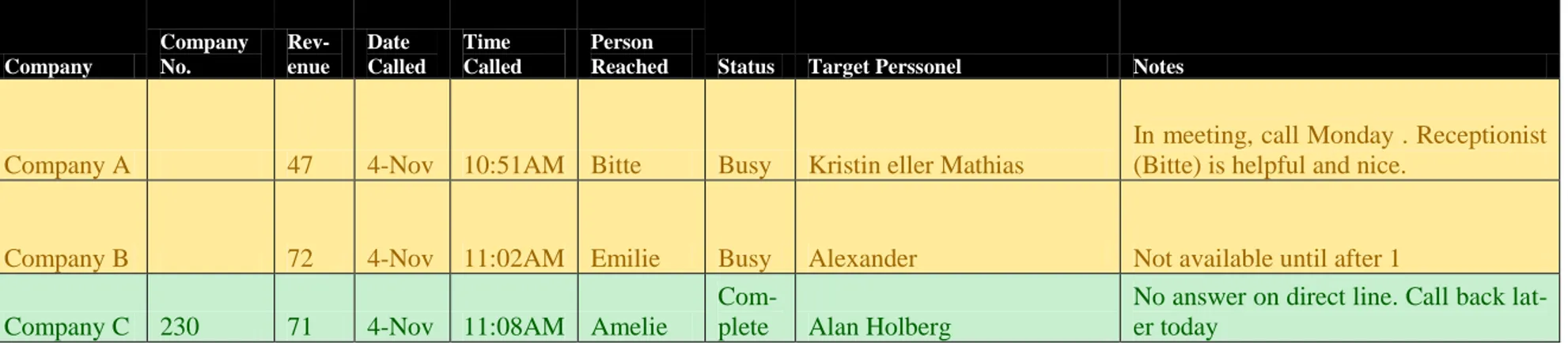

10.4 Excel Call Metric Tool ... 5

5

1

Introduction

Science Park in Jönköping current owners, being, Jönköping University and Jönköping municipality, are interested in inviting a third participant as a co-owner and financier of SPJ (Science Park, 2008). Advised by the current owners, the board of directors took initiative in investigating the feasibility of this task (J. Svedberg personal communication, 2009-09-24). Behind this reasoning lies the idea of making SPJ an even stronger organization that actively interacts with the private sector. Through this SPJ is looking at the prospect of building a stronger foundation with a broad ownership base as well as expanding the possi-bilities to support the organization.

SPJ’s objective involves seeking and determining the viability of attracting another investor to be among its current financiers, Jönköping University and Jönköping Municipality. Their targets are the business cooperatives: Handelskammaren in Jönköping, Företagarna in Jönköping, and Svenskt Näringsliv in Jönköping (take special note that they are focused on the local levels of these organizations).

In other words, SPJ is looking to actively incorporating the established enterprises in the Jönköping region, thus creating a natural collaboration between new ventures, business ideas and startups with the already well established companies, through the membership organizations active involvement within SPJ. This involvement, preferably done through a stakeholder position in SPJ as an active member of the board of directors, thus having the possibility to directly influence the decision making within SPJ and creating a communica-tive link to the already established enterprises in the Jönköping region. Through this, the current board has a vision of naturally interacting SPJ with the business arena in the region. (J. Svedberg personal communication, 2009-09-24).

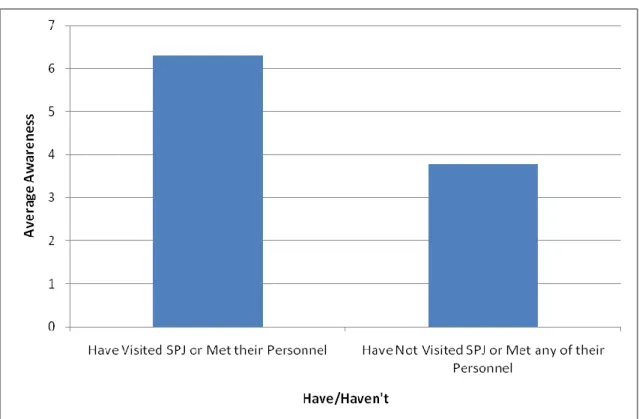

Although this is a long term objective of SPJ, this thesis will only cover the initial investiga-tional step in the future possibility of a new ownership structure, and finding out if the members of the previously mentioned established companies in the region are open for a closer collaboration with SPJ through their membership organizations. However, when in-vestigating such a task, several vital questions must be answered; Do the companies have a positive view of SPJ? Are he companies familiar with SPJ? Are the companies that have vi-sited SPJ more positive about SPJ than the companies that have not been in contact with SPJ? And if the companies are not familiar with SPJ, is it possible to see a pattern that can help SPJ creating a strategy to actively market themselves through creating various events, thus build up a positive image about themselves as something that is beneficial to the Jönköpign region? These raised questions are vital for SPJ in their long term goal of attract-ing new co-owners and the others of this thesis will try to answer the raised questions, hence making it possible for the SPJ management to further investigate the possibility of the discussed ideal plan of an active co-operation with the Jönköping business arena. The focus of the SPJ managment deals with the preliminary investigation in this objective by profiling SPJ’s awareness amongst their targets, identifying points of interest in attract-ing new active o-owners of SPJ. For this to become a reality, one has to initially investigate the companies of the membership organization and find out their perception of SPJ. Hence, the writers main task of this thesis has been to find SPJ´s perception among some of the established companies in the region. During the progress of this thesis, however,

6

the writers also saw the need to discuss SPJ´s plans directly with the business collectives that they are attracting and getting their view on the feasibility of the task.

A lot of research has previously been conducted investigating the benefits of incubators, science parks, research parks, technology park, business park and innovation centres, how-ever, in regards to the issues of financing incubators relating to invite business collectives through that their membership base that see the value of a science park and its start ups, there is limited amount of research. Generally speaking, SPJ is interested in what value me-dium and large sized businesses can derive from their incubator services and the companies located there. Consequently, the authors have seen the need to collect data through inter-viewing some of the companies and thus investigating if there indeed is a positive view of SPJ. Mainly answering if there already is a significant awareness to push this task forward, or if more interaction is needed from SPJ with the already established companies in the re-gion to accomplish the long term goal of SPJ´s management, being to creating a natural bridge where new ventures actively co-operate with the established companies. As SPJ´s management avenue in creating this natural bridge is to target the business collectives, e.g. Handelskammaren in Jönköping, Företagarna in Jönköping and Svenskt Näringsliv into becoming a co-owner of SPJ. The writers’ task will be to investigate the feasibility of such an event taking place.

7

2

Purpose

The purpose of this thesis is to examine the feasibility of adding the local business collectives in Jönköping as co-owners of SPJ.

2.1 Discussion of Problem

As mentioned earlier, SPJ’s target co-owners are:

1. Handelskammaren in Jönköping(The Chamber of Commerce): is one of the 12 Chambers of commerce in Sweden. Registered businesses in the county are allowed membership into the Chamber. Member’s represent many different sectors in the business arena but are separated into two man groups: Business development com-panies, and service organizations (Handelskammaren, 2009.

2. Företagarna (The Swedish Federation of Business Owners): creates better condi-tions for starting, running, developing, and owning a business in Sweden. (Företa-garna.se) The organization has 55 000 members in Sweden. The local organization in Jönköping makes sure to organize various events, from breakfast seminars, net-work-meetings, galas to hockey games, where the members can take in new infor-mation, exchange knowledge as well as establish new connections (Företagarna, 2009).

3. Svenskt Näringsliv (The Confederation of Swedish Enterprise): is Sweden’s largest and most influential business federation representing 50 member organizations and 54,000 member companies with some 1.5 million employees. It was founded in 2001 through the merger between the Swedish Employers’ Confederation (SAF, founded in 1902) and the Federation of Swedish Industry (founded in 1910) (Svenskt Näringsliv, 2009).

The focus of this thesis deals with the preliminary investigation in this objective by profil-ing SPJ’s awareness amongst their targets, identifyprofil-ing points of interest in attractprofil-ing new ac-tive o-owners of SPJ. For this to become a reality, one has to initially investigate the com-panies among the business collectives, find out their perception of SPJ and thus answering if SPJ is mature enough to proceed in targeting the new potential co-owners.

The benefits of such an investigation will provide insight in the differences in ownership models in the incubator arena, and by researching into the feasibility of a adding a private owner to an already established public ownership, future investigators will have more light shed upon different types of ownership structure, the resulting changes in objectives and motivations of such a change, and, finally, how the region will be affected by the change in focus on goals.

Accompanied to this niche subject, this analysis can provide an interesting perspective on an otherwise un-founded topic: how business incubators attract or incentivize new owners. Sustaining the capital for running an incubator’s operations is high priority, which allows this thesis in becoming applicable to the young and growing incubator. This case’s

direc-8

tion of detailing proposed methods in scoping the feasibility of attracting an incubator’s target, and how to effectively convince potential investors to develop a more involved fi-nancial role will aid in learning how to support this shared need in incubators, namely own-ership and its relationship with the incubator’s financial capital.

From this information, a further analysis reveals these three main questions surrounding the goal of our Purpose:

What is SPJ’s current public profile within the Jönköping business community and its organizations?

Can SPJ successfully approach the business community?

If not, is it possible that SPJ still can collaborate closely with the business commu-nity in developing the region of Jönköping?

9

2.2 Delimitations

After approaching these organizations, explaining our research, and why we found this top-ic of interest, we were only able to obtain the needed membership lists from both Företa-garna and Handelskammaren in Jönköping. Hence, we needed to delimit our survey from the companies being members of Svenskt Näringsliv due to a classified membership list. This will be elaborated further in the Problems section.

This thesis will perform a data collection of 30 randomly selected evenly distributed small-to-large size enterprises.

The research is not aimed at increasing SPJ’s public profile, nor any testing and implemen-tation of proposed strategies. And, our questionnaire is not intended as marketing tool for informing the public about Science Park. In regards to the geographical area, our research is only focused on the Jönköping region. Meaning, we aim to contact companies that are inside the cities of Jönköping and Husqvarna.

The authors on behalf of SPJ are targeting 15 companies from each group: Företagarna in Jönköping and Handelskammaren in Jönköping and Svenskt Näringsliv in Jönköping, in-terviewing one manager from each of these companies. The authors also interviewed the managers from the respective three membership organizations Due to difficulties ion ex-tracting the membership lists from Svenskt Näringsliv in Jönköping the authors could not interview any of their members, although, an interview was performed with the manager of Svensk Näringsliv. This issue is expanded further later on in this thesis. As a result the au-thors are looking at the companies as group that is comprised in a membership organiza-tion. In order to make conclusions from each potential target investor, a minimum sur-veyed sample of 30 must be harvested (Calkins, 2005). Therefore, the authors will focus on the group as a whole that is a part of a SPJ targeted enterprise collective in the Jönköping area.

2.3 Definitions

General Terms:Business Incubator: A more comprehensive term that can include science parks, but

dif-fers in that they focus on providing business support rather than just focusing on new and innovative ideas (Ylinenpää, 2001).

Science Park: There is no standardized and accepted unified definition of a Science Park,

however there are similar words to describe the same term ―…such as Research Park, Tech-nology Park, Business Park, Innovation Centre etc…‖ (Löfsten and Lindelöf 2004). Even though the definition of a Science Park according to IASP, the International Association of Science Parks, is ―…an organization managed by specialized professionals, whose main aim is to increase the wealth of its community by promoting the culture of innovation and the com-petitiveness of its associated businesses and knowledge-based institutions.‖ (IASP, 2002) and according to Thomson, an area devoted to scientific research or the development of science-based industries (Thompson, 1995).

10

Science Park System: The Science Park System in Jönköping county works with local

participants by focusing on areas of development through new business ideas, linkages be-tween enterprises, and knowledge transfer. Members include: Aneby Novumhuset, Vag-geryd Kreativ Arena, Science Plant, etc (Science park Jönköping, 2009).

Science Park Jönköping: Is a meeting-point for knowledge intensive businesses and

dri-ven entrepreneurs. (Science Park Jönköping, 2009)

Jönköping County: Is a political decision body that makes decisions about healthcare in

the region and regional development. This county includes 16 municipalities

Jönköping Municipality: Is the smallest political decision body, and it takes care of the in

the particular region called Jönköping.

Theoretical Terms:

Awareness: How well consumers are informed about the existence and the availability of a

brand and hence captures directly the extent to which the brand is part of consumers' choice sets (Clark et al, 2009).

Recognition: In the contexts of brands, can be defined as: a measurement of the ability of

consumers to recall their experience or knowledge of a particular brand (BNet, 2009).

Strategy: ―Tells you what opportunities the business is pursuing in the environment and

by, interference, what resources, organizational capabilities, and management preferences are required for effective implementation.‖ (Crossan, Fry and Killing, 2005).

Attraction Strategy: The attraction strategy is characterized when the main target group

are the already established companies. (Ylinenpää 2001).

Incubator Strategy: The incubator strategy is characterized as focusing on the researchers

or entrepreneurial students with new innovative ideas (Ylinenpää 2001).

Loaned Executive Program: A program where large companies loan their executives, i.e.

a Business or Product Development Manager, to incubator so as to provide incubator stu-dents (the small companies inside the incubator) with hands-on advice on their given ex-pertise. The incubator, in return, loans out their seasoned business managers and mentors to the large companies (M. Nathan personal communication, 2009-12-01).

Targets

Handelskammaren: (Chamber of Commerce) The association Handelskammaren in

Jönköping County are owned and ruled by the members. Create better developing possibil-ities for companies also play as important meeting place for the enterprises (Handelskam-maren, 2009).

11

Företagarna: (The Swedish Federation of Business Owners) creates better conditions for

starting, running, developing, and owning of businesses in Sweden (Företagarna, 2009).

Svenskt Näringsliv: (The Confederation of Swedish Enterprise) the employer’s equivalent

of a union. Their main focus is taking care of the employer’s interest (Svenskt Näringsliv, 2009).

12

2.4 Outline of the thesis

13

3

The Empirical Context of the Study – SPJ

The Empirical Context of the Study – Science Park in Jönköping, has been focused on in assisting both the authors and the reader in gasping the complexity of the studied matter; understand the background of SPJ, their history, organizational structure, the region where they are active but also understand why this study is of importance for SPJ.

3.1 Science Parks as a Phenomenon

To prelude the investigation into the objective, the authors have outline what exactly a business incubator is and what purpose or role they serve in the business community. The magazine Entrepreneur.com (2009) states that a business incubator as ―An organiza-tion designed to accelerate the growth and success of entrepreneurial companies through an array of business support resources and services that could include physical space, capi-tal, coaching, common services, and networking connections.‖ (Entrepreneur.com, 2009). Their goal is to provide aspiring entrepreneurs with the tools necessary to take their ideas and business foundations to flight. Oftentimes, these organizations, which are found all around the world, can provide access to funds, leasing space, computer equipment, and, most importantly, mentorship from top business managers from around the area.

The introduction of the first science parks emerged in the US in the 1950s, but the first science park in Europe was established in Scotland in the city of Edinburgh in 1965 (Yli-nenpää, 2001). As for Scandinavian countries, the first science park was opened in 1985, in Oulu, Finland (Ylinenpää, 2001).

A business incubator is a program designed to develop successful growth for entrepre-neurial firms by utilizing an array of different business services and resources. This is coor-dinated by incubator management teams that provide help through new contacts, business development, and financing assistance to newly started companies. The structure of an in-cubator can differ when it comes to what kind of resources and organization they have and what kind firms and customers they serve. An incubator or a science park have many syn-onyms, all different terms to describe a science park such as a ―…research parks, technol-ogy parks, innovation centres, technopoles, etc., and this rather diverse vocabulary indeed reflects the fact that there is no uniformly accepted definition of a science park.‖ (Hom-men, Doloreux & Larsson, 2005)

There is a difference between a pure research technology parks and incubators. The major difference lies in the scale of their projects and their degree of collaboration with the uni-versity, government, or any other private sector companies. However, the most significant difference is that most often research and technology parks do not offer any business sup-port, whereas this is one of the core businesses activities of a business incubator (Yli-nenpää, 2001).

A benchmarking study in the European commission also stated a difference between Eu-ropean incubators and US incubators. EuEu-ropean incubators have developed a great exper-tise in fields such as virtual networking, entrepreneurial training, and creating integration of incubator functions into broader strategies (Jenniskens, 2007). In contrast, US

incuba-14

tors are stronger in financing and management structure (Jenniskens, 2007). There is also a difference between the European/Japanese Science Park. The Government in Japan, France and the Netherlands, have played an active part in the science parks and its creation, while looking at the science parks in the United States the government tends to only be in-volved in the actual development of the parks, and not focusing on coordination the parks often done in Japan, France and the Netherlands. (Goldstein and Luger 1990).

Early stage business often comes to an incubator with the lack of knowledge, questions, and a lack of financial capital to grow their business ideas. And, this is where incubators come into play: they give them the basic tools to make their journey successful. Generally, there are three main services that they offer: mentorship, physical equipment and space, and connections. The first service, mentorship, is used guide incubates (the small compa-nies matriculating through the business incubation process) to their business fruition (En-trepeneur.com, 2009). The second service incubators offer are tangible equipment and ser-vices such as: leasing space, high speed internet, computers, and sometimes gyms and car-pooling (Science Park Jönköping, 2008). The last services, which can be understood as in-tangible services, are the networking and connections that are brought to the table (Entre-peneur.com, 2009).

With the incubator’s mentorship the companies can overcome some of their knowledge gaps, and with the incubator’s tangible service overcome some of their lack of resources. Also, networking is crucial for early business to help in raising financial capital. With these services, they can begin to grow, and, finally, they will hopefully be able to stand on their own feet and take their ideas to flight.

The start of incubators originally came from the west coast in the United States, in Stan-ford Research Park during the 1950s and its purpose was to support entrepreneurial and academic people at the university (Swedish Incubator association, 2009).

Even though the original start of Science Parks started as early as the 1950’s, the growth is still continuing. According to Swedish Incubators & Science Parks’ (now referred to as, SISP) research in 2008, concluded that the amount of companies in their science parks in Sweden has increased 20% between 2005 and 2008 (Swedish Incubator Association, 2009). In 2000 there were 2,752 companies in SISP, and it increased to 3,320 companies in 2008 (Swedish Incubator Association, 2009). For information see Appendix section 9.1.

The same report also shows an increase regarding the new working positions within the SISP science parks in Sweden. In 2005 there were 50,429 involved in the SISP science park companies, and in 2008 this number increased to 64,445, meaning a growth of 27% be-tween 2005 and 2008 (Swedish Incubator association, 2009). In short, there has been a pat-tern of growth within the SISP incubators and science parks in Sweden between 2005 and 2008.

3.2 Science Park Jönköping

To better understand the object of research the authors give an introduction to Science Park Jönköping and its history.

In Jönköping’s case, SPJ was founded in spring 1999 by Jönköping University and Jönköping Municipality, Jönköping County, 16 municipalities, Handelskammaren in

15

Jönköping and Företagarnas riksorganisation (D. Friberg personal communication, 2009-09-30).

Science Park Jönköping was founded as a model for new and developing businesses to create sustainable growth in the region of Jönköping. Until 2008, the Science Park System, which included other Science Park satellites, and Science Park Jönköping were one body. But, in 2008 the Science Park System and Science Park were separated into two distinct parts: Science Park Jönköping, and the encompassing, Science Park System (D. Friberg personal communication, 2009-09-30).

Today, the split has changed the hierarchy vastly. The Science Park System comprises of business collective members such as: Handelskammaren, Svenskt Näringsliv, Företagarna, and is also other entities such as the various municipalities and Jönköping county. This change in hierarchy moved the business collectives’ focus from one that was geared to-wards the Jönköping community as a whole toto-wards a more general relationship or more encompassing one amongst all Science Parks in the region. Presently, the Science Park Sys-tem is financed through the regional council of Jönköping (Science Park SysSys-temet, 2009). And, in SPJ’s case, they are owned 50% by the University of Jönköping and 50% by the Jönköping municipality. This 50-50 split was a natural result from the change in relation-ships in 2008. Clearly, Jönköping University and Jönköping municipality would become owners of SPJ since they invested equal money in SPJ on a yearly basis (D. Friberg person-al communication, 2009-09-30).

The reasoning behind this was that since only Jönköping University and Jönköping muni-cipality injected money into SPJ on a yearly basis (the funding being necessary for SPJ as a non-profit organization) it was decided that these two will become the owners of SPJ (D. Friberg personal communication, 2009-09-30).

It also gave the financiers, being geographically adjacent to SPJ, a better overview as active members and strengthened the relationship among the participants. However, the two members, Jönköping University and the municipality of Jönköping, are now interested in re-inviting the private sector as active members in order to address the future needs of en-terprises in the region.

3.3 Notes from a Conversation with Dan Friberg

This conversation took place on the phone on the 30 of September 2009. The authors here present the notes and conclusion from the conversation. In order to understand the past structure of SPJ, Mr. Friberg (tempo-rary CEO of SPJ), revealed information on their previous history with emphasis on their split-up from the traditional hierarchy. Below, is a summary of the conversation with Friberg. These notes have also been sent to Dan Friberg, in order for him to validate the accuracy of this information.

The founders of Science Park Jönköping in 1999 were: Jönköping University, Jönköping Municipality, the county council, 16 local municipalities, Företagarna in Jönköping, Han-delskammaren in Jönköping, and Svenskt Näringsliv in Jönköping. All these provided some capital in starting the non-profit. The only reoccurring entities that funded SPJ operations, by giving SPJ an annual funding were Jönköping University and Jönköping Municipality.

16

In June 2008 the original founders of SPJ seperated. In this split up SPJ was put as collabo-rator and was included in building on the present-day Science Park System. This system it-self has several entities within, where one of these entities is SPJ. The system has no owner-ship rights to SPJ, but functions as a network between the different entities in Jönköping County. These different Science Park Entities are Aneby Novumhuset, Eksjö, Gislaved, Arenum, etc. And, there are several new science park entities growing in other cities in Jönköping County. The purpose of the Science Park System is to increase the collaboration between the various Science Parks in the different municipalities in Jönköping County. Al-so, the Science Parks in the municipalities in Jönköping County are working together in rais-ing funds from the EU and the sharrais-ing of knowledge and previous experiences.

As a result of the restructuring in the Science Park System, it was natural that the two yearly financiers of SPJ, Jönköping University & Jönköping Municipality took their place as own-ers of SPJ.

Today, Företagarna, Svenskt Näringsliv, and Handelskammaren are involved in the Science Park System, but are not directly involved in SPJ’s operations or funding. This is the reason why SPJ is interested in the opportunity to get back Företagarna, Svenskt Näringsliv, and Handelskammaren in Jönköping as an active owner.

Figure 1, Source: (D. Friberg personal communication, 2009-09-30).

3.4 Region of Jönköping

To understand what kind of environment Science Park Jönköping is working in, one should describe this area of operation. Jönköping is a city located in southern part of den and has around 126,000 inhabitants and is among the 10 largest municipalities in Swe-den, and is increasing in citizens every year (Jönköping Kommun, 2009). Jönköping has

17

about 10,000 companies, which are comprised of 4,000 limited companies (Jönköping Kommun, 2009). It also has a diversified business arena in the nearby area of Jönköping with companies such as: Kabe, Arla foods, Kinnarps, Husqvarna, Lammhults, Fagerhuls, Sensys Traffic, Saab, and Systeam. In addition, Jönköping is as a strong logistics center, whose products reach a large part of Scandinavia (75%) (Jönköping Kommun, 2009). Moreover, Jönköping contains a growing University currently comprising of 11,000 stu-dents and about 800 employees (University Jönköping, 2009).

18

4

Frame of Reference

The frame of reference section has been focused on assisting the authors when making sense of our empirical observations from the 30 interviewed companies and deriving valu-able conclusions from them, both in forms what we can learn from previous research, oth-er success stories and strategic models that latoth-er can be used in our analysis and conclusion.

4.1 A Background on Science Parks

The first research to be made on incubators and Science Parks started as early as 1984 when Temali and Cambell first started to look into this area with their report ―Business In-cubator profiles: A National Survey‖ (Hackett & Dilts 2004). The research done by Timali and Cambell triggered two additional reviews to be completed by 1987. The additional re-views were completed by Cambell and Allen as well as Kuratko and LaFolette in 1987, (Hackett & Dilts, 2004). Since this early literature review, done in the 80s, the Incubators and Science Parks have grown tremendously, and are still growing even today (Appendix 9.1). Even though there have not been any major systematic reviews of the literature and research made since then that have concluded the large amounts of research that has been made (Hackett & Dilts, 2004). Authros such as Hommen, Doloreux and Larsson states in their research that ―…the performance of science parks remains a poorly understood phe-nomenon, and existing accounts provide, at best, only a fragmentary and incomplete pic-ture of the factors contributing to science park success. (Hommen, Doloreux & Larsson, 2005)

In order to understand the process in an incubator one can divide the operations of a Science Park into several stages. These stages are: selection, development and graduation (Norrman, 2008). The first stage is when the incubator chooses what kind of companies it will accept and which to reject (Norrman, 2008). This selection process may differ based on the focus of the incubator. Some might focus on IT, software, business services, inno-vation, biotech, and/or green-tech (Norrman, 2008). According to Hommen, Doloroux and Larsson ―…a science park is a learning site, combining in a pre-established territorial area productive, scientific, technical, educational, and institutional agents, based on the as-sumption that the co-location of these agents is expected to enhance the technological and innovation capability of the host region.‖ (Hommen, Doloreux & Larsson, 2005). Howev-er, Norrman (2008) states , the actual selection stage can be divided into four divisions. The criteria oftentimes look at either how well the team/individual was or how good the idea was (Norrman, 2008). Then the incubator must decide how flexible they are in accepting new applicants, and it comes down to the ways they evaluate the business venue under the criteria presented in the process section (Norrman, 2008). ―Survival-of-the-fittest and idea: The portfolio will presumably consist of a quite large number of idea owners (or upcoming en-trepreneurs) with immature ideas related to a broad spectrum of fields.‖ (Norrman, 2008). ―Survival-of-the-fittest and entrepreneur: The resulting portfolio will be diversified, and consist of entrepreneurs/teams with strong driving forces representing a broad set of ven-tures.‖ (Norrman, 2008).―Picking-the-winners and idea: Results in a highly niched portfolio of thoroughly screened ideas within a quite narrow technological area—often sprung from the research of highly ranked universities.‖ (Norrman, 2008).―Picking-the-winners and entrepreneur:

19

The portfolio consists of a few handpicked and carefully evaluated entrepreneurs, com-monly with ideas coupled to the research areas of a nearby university.‖ (Norrman, 2008). After the stage of selection there is a continuous ongoing development process (Norrman, 2008). It starts with infrastructural needs as well as coaching or training activities and vari-ous types of business support for the new businesses required to succeeding. And fur-thermore it includes the process of how the business will connect with outside world (Norrman, 2008). Basically, this stage is consisting of providing the entrepreneur within the required resources, both in form of office space but also on the level of helping to increase the know-how of successfully running a business and succeeding in establishing and net-work and marketing. The final step is the graduation when the business is ready to graduate (Norrman 2008). Basically it means that the company leaves the business incubator and stands on its own legs outside the incubator.

Sean M Hackett and David M Dilts (2004) completed the latest literature review where they include research made on incubators until 2004. Hackett and Dilts (2004) wrote that the re-search areas that have been studied consist of five primary rere-search orientations. These are: incubator development studies, incubator configuration studies, incubate development stu-dies, incubator-incubator impact studies and finally studies that theorize about incubators-incubation (Hackett & Dilts, 2004). According to Hackett and Dilts (2004), one problem with the research about the incubator is that there is no clear definition. In their report from 2004, they state that there have indeed been a lot of extensive research about incuba-tors and their development since their 80s (Hackett & Dilts, 2004).

In the research on incubators there are two major fields of research that are common. Per-formance outcomes, where you measure the benefit of having a science park, to know if governments, municipalities are getting their money’s worth, in the benefit received by the regional business arena (Norrman, 2008). Numbers of studies have been done in this area both by Norrman (2008) and Allen & McCluskey (1990) was the first to do a performance measurement on incubators among other. Other significant research regarding this topic has been done by Aernoudt (2004), Bhabra-Remedios & Cornelius (2003), Chan & Lau (2005), Lindelöf and Löfsten (2005) and OCED (1997), (Norrman, 2008). Hence, it has been a common study to look at the impact received by a Science Park and the benefit it gives back to the enterprises and entrepreneurial spirits in the nearby region. Other fields of research has been looking into how can Science Park improve management policies and their effectiveness. In the field of management one can find a Swedish researcher M. Klofs-ten (1998) who tried to find out how general practice that can be adopted on Science Parks, how they work as well as showing their successes factors that other incubators could learn from and take into practice (Klofsten, 1998).

Another interesting paper is written by Rosa Grimaldi and Alessandra Grandi (2005). This paper, published in 2005, focuses on incubators and new ventures. Their research ―Busi-ness incubators and new venture creation: An assessment of incubating models‖ done on empirical research on Italian incubators, identifies four different models on incubators Business Innovation Centers, University business incubators, Independent private incuba-tors and corporate private incubator (Grimaldi & Grandi, 2005).

As mentioned earlier, there is a difference between incubators between USA and Europe. In Europe the more common model which also is one of the first incubator models is the

20

business Innovation centre founded in 1984 by the European Commission (Grimaldi & Grandi 2005). Another very common form in Sweden is the University business incubator, in which the incubator is closely tied to the university in hopes of eliciting more innovation and ground-breaking ideas (Swedish Incubator association, 2009). Grimaldi and Grandi (2005) also mentions that the public Science Parks seems to have more tangible service and terms as well as amore nonpayment based systems than the private who rather have a more intangible service and payment system (Grimaldi & Grandi, 2005). In their research Gra-maldi and Gandi (2005) have been looking at characteristics that can evaluate how the business within an incubator is progressing. Looking at the following areas; institutional mission/strategy, the industrial sector, location, market, origin of ideas, phase of interven-tion, incubation period, sources of revenue, service offered and management teams, one can compare and contrast various incubators with each other (Grimaldi & Grandi, 2005). Looking the Swedish studies that the authors looked at, that has been carried out previous-ly in Sweden, this area has not been under extensive research in comparison with the stu-dies done in America and the rest of Europe. One bachelor theses have been examining how the business incubator affect student starting a new company. This topic has been mentioned by and Andersson & Yngvesson (2008). Another article was written by Norr-man (2008), previously mentioned in the processes section, and is one of few Swedish re-search papers that have been looking into the science parks. The article was applied on 16 Swedish business incubators. However, her research focused on the different models on the actual selection process when inviting a company to the incubator of a Science Park. The management teams of the science parks or incubators see this first selection as a vital step in order to get the right people and to be efficient with their resources (Norrman, 2008). Another thesis has investigated how the incubator and Science Park are seen by stu-dents, thesis ―Entreprenörskapscenter eller takeaway pasta‖ written by Jungåker, Elfsberg, Wetterlind (2008), where they studied Science Park in Jönköping, and their communication skills among the students at Jönköping University. Additional research carried out by Sahlin-Andersson (1990), Quintas et al. (1992) and Johannisson (1998) surprisingly shows that that co-operation between firms was less than one might expect. The study carried out by Sahlin-Andersson (1990) concludes the complexity of the issues ―that the reason for lo-cation in a Science Park was not to establish new contacts but to preserve old ones.‖ (Löf-sten and Lindelöf, 2004). Even though there has been a lot of research carried out in this area ―…the performance of science parks remains a poorly understood phenomenon, and existing accounts provide, at best, only a fragmentary and incomplete picture of the factors contributing to science park success.‖ (Hommen, Doloreux and Larsson, 2005).

4.2 Ownership and Financing

Ownership can look different, and most incubators in Sweden have their own legal limited company identity (Swedish Incubator association, 2008). Most structures of the members of SiSP run as an ―AB‖ (LTD). Of the 29 members in SiSP, 20 are run through the owner-ship form of an AB. The others are funded through foundations, by the public sector and by other legal forms. See appendix 9.1. Oftentimes when the incubator is close to a univer-sity, the university supports the science park, however; the support can be multi-dimensional. Some contribute with staff and others with facilities. In Jönköping the Uni-versity contributes by being one of the financiers of the Science Park.

21

There are different models for owning Science Parks in Sweden, some models mimic the SPJ system in Jönköping, while some are more similar to privately owned science park structures. In short there are three varying structures. They are: the municipality is the owner, the university is owner, and where a private consortium is the owner. These model types are exemplified below:

Science Park Mjärdevi, an incubator located in Linköping. The aim is centered on spin-offs from the university combined with big international companies and groups of scientists (Science Park Mjärdevi, 2009). Mjärdevi is run as a limited company (AB). According to Science Parks Mjärdevis annual report (2008) they had a turnover about 6.9 MSEK (2008), and they are 100% owned by Linköping municipality (Science Park Mjärdevi, 2009).

Karolinska Institute Science Park is a Science Park owned 100% by Karolinska Institute Holding AB who is a sister company to Karolinska Institute. They’re allowed to create profit and take risks, and their business idea is to be an integrated part of the Karolinska Institute innovation system and the commercialization of research (Karolinska Institutet Science Park, 2009). Their turnover in 2008 was 4.3 MSEK (Karolinska Institutet Science Park, 2009).

There is also one example of a private incubator owned and finance through private and institutional investors. Like ―Sjätte AP-fonden‖ and the private investor and founder Johan Staël Von Holstien. Iqubes turnover was 11 MSEK (2008). According their website it is written that it should be a green house for new businesses to reach commercialization for their products and services. Unfortunately, due to financial difficulties, the operation has currently stopped and Iqube have stopped in taking in new companies (Iqube, 2009). It also of interest in investigating the science parks across the globe. In terms of attracting the private sector and providing a benefit to society, they deliver. They, too, provide new job opportunities, new technologies, and help already established companies extensively. The following sections elaborate in more detail this topic.

The Business Incubators and Technology Parks in Croatia report outlined the different ownership structures in their country. This research paper examined 17 incubators in Croatia, and all of them had one thing in common. All of the examined incubators were had some type of financing from the city or municipality (Audeo Market and Public opi-nion research, 2008). See appendix 9.2.

However, what is interesting from the point of view of Science Park in Jönköping, who would like to include in ownership the private companies via their association or a chamber they’re apart of, is the amount of science parks that have achieved in integrating private companies as owners. From appendix 9.2, one can see that 17.6% of the 17 incubators that were investigated in Croatia had private companies as direct investors (Audeo Market and Public opinion research, 2008). Also note that the Croatian Chamber of Economy and Croatian Chamber of Trades and Crafts were involved as an active owner in 11.8%. (re-spectively, 5.9%) In short, SPJ may have an opportunity in attracting Handelskammaren, Företagarna or Svenskt Näringsliv into their ownership structure were they to present the precedence found in Croatia (Audeo Market and Public opinion research, 2008).

Science Park in Jönköping is not the only one looking into the matter of interacting with the public sector. One of them is Daresbury Science & Innovation Campus, which is more commonly referred to as Daresbury SIC. This newly funded Science Park, located in the

22

United Kingdom, is currently looking to enter a joint venture with the private sector busi-ness or a consortium of investors (Daresbury Science & Innovation, 2009). Their aim is to select the partner early 2010, and they are currently in evaluation, ―…the process of identi-fying a private sector partner is to develop up to 1 million square feet of space for business, research and innovation, providing facilities management and other services to the Campus and realizing commercial services and investment opportunities with the Campus compa-nies‖ (Daresbury Science & Innovation, 2009). The idea of integrating with the private business sector or a consortium is motivated by the importance of developing the region, providing new opportunities, and mainly as a way to increase the interaction between com-panies, universities, etc to develop the region even further (Daresbury Science & Innova-tion, 2009).

They also see the benefits of their operations as something that will bring, ―…businesses, universities, research organizations and industrial partners with the business support and investor community, to create up to 10,000 jobs.‖ (Daresbury Science & Innovation, 2009). As stated earlier, Daresbury Science & Innovation Campus is expecting to select a partner in the early 2010, which further substantiates the idea that there are indeed examples of other science park/incubators that are planning and expecting to succeed in interacting with the private sector as financiers of a Science Park and its operations by basing it on the benefits received by the society and already existing companies (Daresbury Science & In-novation, 2009). There are also other examples where the private sector has seen the bene-fits of having a strong Science Park in the region not only through new work opportunities, development in technology, and research but also as a channel that can promote and reform industrial structure (Daresbury Science & Innovation, 2009).

Established in 1989 the Kanagawa Science Park was the first established science park in Ja-pan (Kanagawa Science Pak, 2009). The science park project was promoted with the coop-eration of the national government and private sector companies (Kanagawa Science Park, 2009). Interestingly, Kanagawa Science Park is seen as a strategic project in promoting the whole region and its development "Kanagawa Science Park is one of the region's strategic projects which promote such reform in the industrial structure. It has been engaged in var-ious activities as a nucleus of creation in which R&D-oriented businesses are established, grow, gather together and interact.‖ (Kanagawa Science Park, 2009). This argument is something that organizations such as Handelskammaren, Företagarna and Svenskt Näringsliv and its members should have an interest in. Additionally, Kanagawa Science Park plays an important role in the development and implementation of the industrial poli-cies of the Kanagawa Prefectural Government and Kawasaki City Government, especially in terms of measures to develop and support venture businesses (Kanagawa Science Park, 2009).

As the authors conclude the frame of reference, we hope that the reader has now garnered a stronger understanding of business incubators, in general, but also in their services, goals, and benefits they provide their regions. In writing the frame of reference, our goal was to bring the reader up to speed in understanding the foundational knowledge of business in-cubators. From this point, we began tailoring that knowledge with emphasis to our specific topic ownership within incubators.

Next, after understanding the many ways incubators can be split up in ownership and how different ownership structures affect the incubators goals and focuses, the authors planned

23

to take the reader another step further. The goal was to reveal case studies in regards to other incubator’s specifically seeking out other entities as owners, and how to summarize how these incubators realized their goal. As one can understand, finding exact case studies to the problem of SPJ can be difficult due to the specific task of this paper. Nonetheless, a lot of studies were indeed found, however, a majority of them were not focuses on the ac-tual ownership of the science park itself.

The authors discovered that the research resembled much like an upside down pyramid, in which the base portion represented general incubator knowledge, and as the authors have proceeded downwards toward the pinnacle, where one find the specific research on cases that resemble the current situation non-existent. Hence, additional concepts have been added looking at a recent Stanford research.

4.3 Awareness as an Additional Concept

In regards to the long term goal SPJ is seeking, one must understand how cognizant busi-ness people in Jönköping are of SPJ and what they offer to the busibusi-ness community. In order to do this, the survey must be focused on revealing the awareness of Jönköping busi-ness people. While there is no specific term to categorize our kind of awarebusi-ness, the au-thors have borrowed the term from a branding framework and applied it to our situation. Recently a Stanford research group sought out to study the effect of advertising on con-sumer awareness. According to this research group, awareness can be defined as, ―… how well consumers are informed about the existence and the availability of a brand and hence captures directly the extent to which the brand is part of consumers' choice sets.‖ (Clark et al, 2009). Granted, this definition specifically deals with awareness in the context of a brand, the definition adequately defines what we are researching. Similarly, the authors are concerned with well SPJ’s target’s members are informed about the existence and the avail-ability of SPJ.

In the work done by the Stanford research group focused their work partly on the extent in which a brand entered the consumer’s mind as possible options when making a pur-chase. This benchmark is almost identical to our directive. When surveying this concept amongst our targets, the members of the mentioned business collectives, we acquire a bet-ter understanding of how commonplace it is for these business people have SPJ in the fo-refront of their conscious when they seek solutions for their entrepreneurial obstacles. Once this information has been collected, the authors can then utilize it to develop a strat-egy on how to market the idea of having the business collectives take part as owners. Thus, the survey information will dictate as to how exactly SPJ should take on the task of attracting these new owners. Take for example, the participants reveal that the majority of the collectives members are not aware of SPJ and what exactly they provide, it would suf-fice to assume that they will also not know or not have an opinion on their collective’s in-vestment into SPJ. Moreover, how can they understand the returns and benefits derived on such an investment and newly established relationship if they, the collective’s members, do not readily understand SPJ hence our need of accurately profiling the SPJ awareness of these business collectives’ consciences.

24

Figure 2, Awareness between SPJ and the Business Community

However, the focus of the survey must be further clarified to prevent any misunderstand-ing of our end-goal. As mentioned here, the authors are interested in the awareness of SPJ in the business arena of Jönköping. Incidentally, this niche of marketing terms where one comes to understand awareness sometimes can lead our reader to confusion in regards to the scope of our surveying. Similar terms to this concept are words such as ―recognition‖ (i.e. brand recognition) and ―identity‖ or ―image‖. These terms, although similar in nature, are not entirely aligned with the direction of our surveying.

Recognition in the contexts of brands can be defined as: a measurement of the ability of consumers to recall their experience or knowledge of a particular brand (BNet, 2009). And, from this definition it becomes clearly evident the difficulty in accurately boxing-in the proposed goals of this thesis. Although, brand recognition is within the same sphere of brand awareness the two differ in terms of their scope (BNet, 2009). To clarify, recogni-tion refers only to the preliminary viewpoint an individual has towards a company’s service or product. When market researchers are interested in surveying recognition their aim is to find out how well a consumer identifies a company’s brand against a competitor or by it-self. While this aim is in the direction of the authors surveying purpose it does not fully grasp the entire scope. One can survey how often business people identify SPJ. However, it does not shed light on whether or not the business community actively derives a value and seeks guidance from SPJ, taking special note that the latter point is more crucial to the development of how SPJ can orient themselves to better attract the collectives as investors. Secondly, the authors are not focused on SPJ’s identity or image. When seeking to profile identity one is trying to understand the set of beliefs that consumers hold about a particular brand (Kotler et al, 2008). Common questions when understanding a company’s identity is to ask, ―Do you view company A to be eco-friendly or green,‖ or, ―Is company A’s prod-uct actually of good value to consumer?‖ Similarly to recognition, identity does not align well with our survey’s aim, and does not fully encompass our project scope. The image that SPJ garners, while slightly pertinent to our attracting the collectives, does not provide us with wholly relevant information on how to persuade the business collectives.

All things considered, authors must collect data on how these target members readily seek or think of SPJ as a source for business services for their problems. In other words, how well Jönköping business people are aware of SPJ in general and as to the help they can provide to companies. This data will be the core information that will guide our efforts in suggesting a way in which to attract the collectives' investments. Understanding SPJ’s rec-ognition or identity in the Jönköping area not only lacks in its cursory approach to strategy not entirely aligned to the exact direction our information needs to lead us to strategy. Therefore, the authors have seen the need of using strategy theories in linking these sec-tions together with the later on performed survey.

25

4.4 Strategy Theories Applicable for SPJ

Using strategy is about looking at the current strategy of a firm to generate new ideas and strategic proposals and to evaluate the proposed strategies before implementation (Cros-san, Fry and Killing, 2005). It is vital for solutions to the challenges encountered by SPJ. However, one also must be aware of the risks in using a strategy.

Even though risk is unavoidable one should not get trapped in a, ―fruitless quest for a risk-free strategy.‖ (Crossan et al, 2005). Instead, one should be aware of the risks and decipher what the firm needs and identify opportunities that the firm has. When doing so, one can use strategic models in order to find methods to implement a strategy that is most likely to have a positive effect on the company and become a competitive advantage (Crossan et al, 2005).

According to our research, environmental risks, ―…arise from the potential inconsistencies between strategy and environment‖ (Crossan et al, 2005). It is fairly easy to make wrong as-sumptions, where timing and potential can be miscalculated and therefore result in a stra-tegic failure. A good example of this difference is the strastra-tegic approach made by Canon and Kodak regarding new digital technology in photography. Canon interpreted the tradi-tional environment using film in the cameras was changing to a more digitalized approach. Canon invested heavily into the digital cameras, while Kodak waited too long before invest-ing in the digital reform, and Kodak was left behind before beinvest-ing able to catch up (Crossan et al, 2005).

Previous studies addressing the success factors of science parks have been completed by Håkan Ylinenpää from Luleå University in 2001. The stated success factors in this research, were a, ―…local market for products and services produced in the park; access to suppliers of components and services in the region; a local culture favoring innovation, entrepre-neurship and co-operation; access to employees with adequate (and normally high) formal qualifications; access to venture capital and good communications; an attractive working and living environment.‖ (Ylinenpää, 2001). Directly drawing parallels to SPJ one can con-clude that they cover most of the outlined success factors needed to build a winning strate-gy.

26

Figure 3, Key Characteristics of successful Science Park strategies (Ylinenpää, 2001)

Ylinenpää’s (2001) Key Characteristics of successful Science Park strategies model, talks about the ―Attraction Strategy‖ and the ―Incubator Strategy‖. The attraction strategy is characterized when the main target group is the already established companies, and the in-cubator strategy is characterized as focusing on the researchers or entrepreneurial students with new innovative ideas (Ylinenpää 2001). Both these strategies share the same general suggestions: being cooperation with a university, put on local entrepreneurial functions, and garner a positive image of the science park. In regards to critical success factors, there is a variation between the attrition strategy and the incubator strategy (Ylinenpää 2001). The attraction strategy focuses on recruitment and co-operation with the university, work-ing towards value addwork-ing services, and finally linkwork-ing the tenants to the university (Yli-nenpää 2001). However looking at the incubator strategy, the most important lies in a legi-timate commercial and business orientation, basic support for new companies, and identi-fying new products from the university (Ylinenpää 2001). Putting SPJ into this scope, hav-ing the researchers and students with innovative ideas as their main target group, SPJ will find them in the incubator strategy.

27

Figure 4, Potentially successful development structures (Ylinenpää, 2001)

In this chart, the domination structures in the model are the horizontal orientation and ver-tical orientation (Ylinenpää 2001). Horizontal orientation is when a science park works with a network based industrial system, a specialized company integration, with horizontal information flows, co-operational among the various firms, as well as cooperation with universities (Ylinenpää 2001). An example of this is how Silicon Valley works. A vertical orientation firm however, is when a science park has independent firm based industrial sys-tems, vertically integrated, with a hierarchical information flow, secret relationship between the firms and independent and self reliable relations between the companies (Ylinenpää 2001). Drawing the parallel to SPJ where they are and want to be, it is clear that SPJ is hav-ing a dominathav-ing structure of a ―Network‖ –Horizontal orientation.

One should also keep in mind Porters (1980) reasoning that combining two strategies can be a risky approach, as this scope has been widely criticized during the latest years, and now however there is instead a ―considerable debate over the potential advantages of combined strategies.‖(Rubach &McHee,1998).

In seeking out opportunities, science parks can succeed by being in cooperation with the already established companies. Previous research states that a Science Park purely focusing on larger multinational cooperation’s is not the only way in succeeding (Ylinenpää, 2001). A strategy used by Madison Research Park, located in Madison, Wisconsin in the US, was to focus on ‖…creating as favorable conditions as possible for commercialization of re-search-based ideas in the form of spin-off companies from universities…‖ and other high-er education institutions (Ylinenpää, 2001). Anothhigh-er strategy, also brought up in Håkan Ylinenpää (2001), research was a strategy used in the Oulu Technopolis Science Park in Finland whose strategy is to ―attract established and larger corporations to locate know-ledge-intensive divisions or units in the park and close to the expertise and the recruitment base which a university represents.‖ (Ylinenpää, 2001).

Previous research shows science parks contributing and promoting to regional develop-ment. There are three general characteristics in doing so. The first is that science parks es-tablish a relationship to a university with advanced and innovative research. Second, that they benefit from a relationship with large and innovative companies, and, third, that they

28

create and maintain an image of the park (Ylinenpää, 2001). SPJ has all three of these func-tions, therefore their general success factors are good.

4.5 Summarizing Frame of Reference

In the frame of references the authors have provided the reader with information on basic ownership models to understand that there are indeed many types of ownership structures, as noted in Mjärdevi, Karolinska, Iqube Science Parks. These three science parks represent the different structures in ownership of a science park. SPJ, if this project is implemented, will represent all three: a university, publically, and privately owned science park, including this into our frame of reference for the simple fact that it sheds light on the newer notion the incubators and science parks can have different types owners, whom have difference needs and focuses in regards to their collaboration with the incubator/science park.

Then, from the previous context, the authors specifically outline two other science parks in the UK and Japan and how science parks are owned in Croatia. This information was pro-vided to show, again, that it has been successfully been done before, namely integration of a private owner into an incubators/science parks’ ownership. But, more importantly, that privatized owners truly help in regional benefit, something seen in both the Kanagawa and Daresby Science Parks. Why is this valuable? Well, this information can be used by SPJ in helping the business collectives to understand that, not only, has this been done before, but also, that it is indeed profitable for both entities and the entire region!

Next, the authors have outlined the differences between the different terms: identity/image, recognition, and our focus, awareness. This had a specifically strong utility in terms of the sur-vey, where one needs to understand the awareness of the business community. Including strategy reflects a similar construction of a relevant frame of mind. Ylinenpää’s two impor-tant strategies will assist the authors place SPJ on the spectrum between attractor and incuba-tor.

In conclusion, the content in the frame of references has guided the writers into formula-tion the following model, where SPJ and the business collectives can serve as a link be-tween new start ups and the already established businesses. The potential ownership situa-tion and the success factor of this taking place is also based on the idea of that SPJ are well known within the business community. This awareness (green) will then assist SPJ to form-ing an eventual ownership alliance (yellow) together with the business collective, hence working together in forming the synergies of assisting the start up with the right connec-tions when commercializing their ideas, and the business collectives to assisting (red) their members in getting in though with interesting innovations or developments in their exper-tise of business.

29

5

Method

The method section has been focused on in assisting the authors to create an adequate I questionnaire/interview material in order to most efficiently get as much information as possible form 30 CEO:s or similar high end positions from companies located in Jönköping. This section will look at the approach of the research and how the reliable data will be collected.

First and foremost, the author’s objective is to define and profile SPJ’s target, the business collectives such as Företagarna Svenskt Näringsliv and Handelskammeren, also interview the management of all thee business collectives. These collectives, as mentioned earlier, comprise of a variety of company sizes and revenue generation within the Jönköping area. In the long run, SPJ’s focus is to entice these business collectives into investing into SPJ’s ownership, but our immediate focus in this thesis is to define who exactly comprises these collectives and profile them. Comparatively, the latter part, profiling, of this objective is a more involved process.

What does profiling mean in this context? Well in terms of our scope, our profiling process will involve capturing an accurate assessment of how well SPJ’s targets are aware of SPJ in general, how aware they are of their services, and to assess if these target’s can derive a val-ue from what SPJ can offer. The larger picture of SPJ’s target’s awareness will define pre-cisely what SPJ’s profile is amongst these collectives’ members. In other words, profiling will allows us to get a stronger understanding to the degree in which SPJ is comprehended and in the forefront of the Jönköping’s small and large size firms’ conscience.

From that point, the authors have an assessment of that sector’s awareness of SPJ, and, ac-cordingly, can develop a strategy into attracting their collectives, of which they are mem-bers of, into investment into the ownership. Regardless of what the profile is, the authors’ data will dictate what kind of strategies and methods SPJ should implement in persuading a non-committed audience, or, in a worst case scenario, realize that the feasibility of the over-arching goal will not yield a large enough reward to overshadow the investment and cost in attracting these potential investors.

In the meantime, here we will detail the process on obtaining the data needed to provide a strategy in regards to the goal. The steps in process are as follows:

1. Defining of the Collectives’ Targets

2. Retrieving and Compiling the Collectives’ Members’ Information 3. Conducting our Surveying/Interviewing (quantitative)

4. Conducting interviews with management personnel of the three business collectives (qualitative)

5.1 Research Approach

The purpose can be defined as a descriptive purpose, meaning that we will observe, regis-ter, and document our findings (Agdell et al, 2009). Hence, getting an understanding of the situation of our task by own research and studies, meaning mainly primary data collection.