Master's Thesis in Innovation and Design

The Customer Experience in

the Product After-Use Phase

A case study of the IKEA second-hand store

Author: Viviana Garcia Espinoza

Märardalen University

IDT - School of Innovation, Design, and Engineering Sweden, 2021

I

The Customer Experience in The Product After-Use Phase A case study of the IKEA Second-Hand store

Master's Thesis in Innovation and Design Viviana Garcia Espinoza

June 2021

Mälardalen University

IDT - School of Innovation, Design, and Engineering COMMITTEE

Examiner: Ph.D. Yvonne Eriksson Supervisor: Ph.D. Marcus Bjelkemyr Copyright © 2021

Viviana Garcia Espinoza.

All rights reserved. No part of this thesis may be copied or reproduced without the written permission of the author.

II

The Customer Experience in The Product After-Use Phase

A case study of the IKEA Second-Hand store

Master’s Thesis Viviana García Espinoza

Innovation and Design June 2021

III

Acknowledgments

This thesis marks the final stage in my wonderful journey as a student at Mälardalen University. I could not be happier and grateful that during this time, I have had the fortune of meeting and collaborating with amazing people, experts in the field of innovation who have contributed to my professional development.

First, I would like to thank my thesis supervisor, Marcus Bjelkemyr, for his support, guidance, and pieces of advice that contributed positively to the development of this study.

In addition, I would like to acknowledge the contributions of the case company, IKEA, to all its employees whom I had the opportunity to meet and discuss my project, in particular to Camilla Johansson for her involvement, mentoring, and the fruitful conversations we had during these months of collaboration.

Moreover, I want to thank Sofia Bystedt from ReTuna for granting me access to the facilities for conducting the interviews at Returen and the recycling station.

Lastly, to all the participants, thank you for your time, openness, and willingness to respond to my inquiries; your insights have been immensely valuable to my research.

Viviana Garcia June 2021, Sweden

IV

Abstract

As customers become more and more aware of the threats and limits of the current economic system, joined with the pressure of environmental policies, companies are pressured to rethink their offerings, processes, and business models in order to accelerate the transition to a circular economy. This transition requires significant changes in habits and behaviors, but simultaneously it offers opportunities for innovation. In this regard, business model innovation plays an essential role in enabling this transition via circular business models that close the loop. For the successful development, implementation, and adoption of new business models, a depth understanding of customers' needs is fundamental. However, little is known about the customer perceptions, motivations, and willingness to participate in circular economy. To address this gap, the study explores the transition to circular economy from the customers' perspective by employing a qualitative single case study bounded to the furniture retail company, IKEA, specifically the IKEA Second-Hand pilot store in Eskilstuna, Sweden. Through in-person interviews, observations, and a questionnaire, data from customers donating their used furniture to the recycling mall ReTuna, people discarding furniture at the recycling station, and people selling and giving away their used furniture via the social media platform Facebook, was captured to explore the customer experience in the after-use phase of furniture. Findings of the study present opportunities for the case company to strengthen its product recovery strategies.

Keywords: Circular Economy, Circular Business Model, Customer Experience, After-Use Activities, Reverse logistics

V

List of Figures

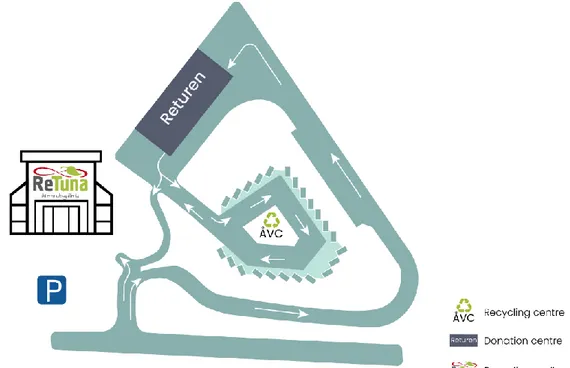

Figure 1 Illustration of the physical setting. Adapted from (Retuna, n.d) ... 6

Figure 2 Product Return Flow at IKEA Second-Hand Store – Context of the study .. 8

Figure 3 Circular Economy System Diagram – Ellen McArthur Foundation (Meloni et al., 2018) ...12

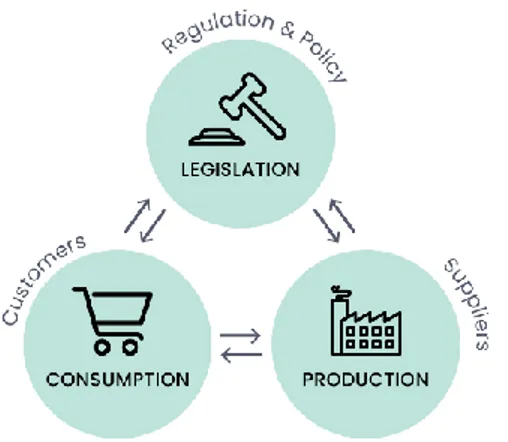

Figure 4 Circular Economy Determinants Based on (Prieto-Sandoval et al., 2018) ...14

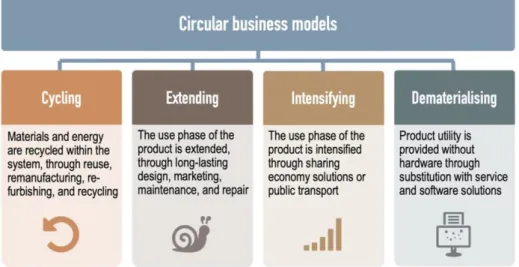

Figure 5 Circular Busines Model Strategies (Geissdoerfer et al., 2020) ...15

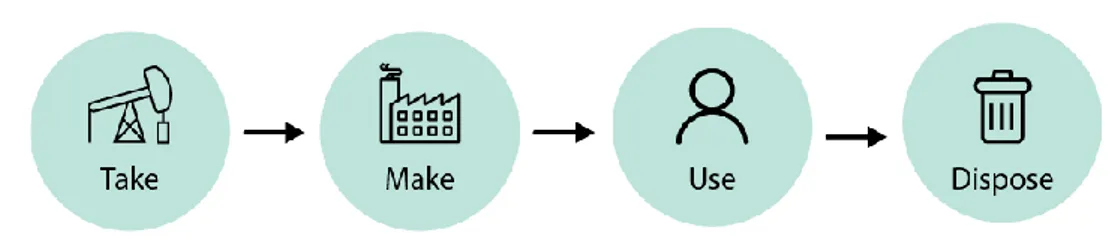

Figure 6 Linear Economy ...17

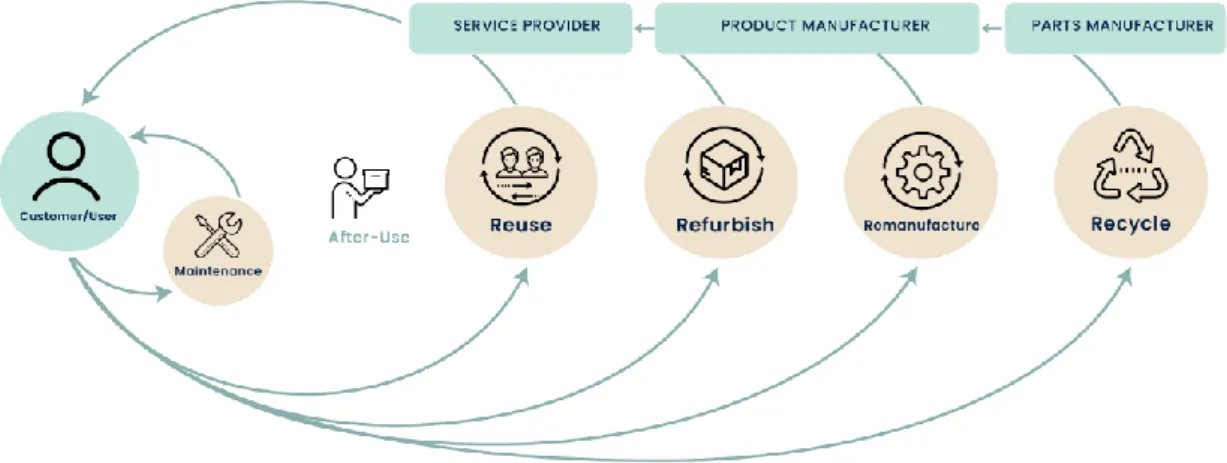

Figure 7 Customer Role in the CE. Adapted from CE system diagram (EMF, 2017) ...18

Figure 8 Closed-Loop Supply Chain. Based on (Agrawal et al., 2015)...20

Figure 9 Customer Value Categories (Schallehn et al., 2019) ...24

Figure 10 Research Design ...27

Figure 11 Research Process ...28

Figure 12 Case Study Overview...29

Figure 13 IKEA Corporate Structure (IKEA, 2020a) ...30

Figure 14 Overview of Data Sources ...31

Figure 15 Donator Customer Journey. Inspired on the Customer Experience Wheel (Martin & Hanington, 2012) ...53

Figure 16 Recycler Customer Journey. Inspired on the Customer Experience Wheel (Martin & Hanington, 2012) ...54

Figure 17 Seller Customer Journey. Inspired on the Customer Experience Wheel (Martin & Hanington, 2012) ...55

VI

List of Tables

Table 1 CE After-Use Activities. Adapted from (Reike et al., 2018) and (EMF, n.d)

...19

Table 2 Overview of Value for the Customer, Based on (den Ouden, 2012) ...23

Table 3 Interviews at the Donation Center (Returen) ...33

Table 4 Observation Instances During the Research Process. ...34

Table 5 Summary of Identified Factors Driving Customers to Discard their Furniture. ...39

Table 6 Reasons Why People Donate Furniture To Returen ...45

Table 7 Reasons Why People Dispose Of Furniture At The Recycling Station ...47

Table 8 Reasons why people choose to sell their used furniture ...49

Table 9 Reasons why People Choose to Give Away their Used Furniture ...51

Table 10 Motivational factors ...61

List of abbreviations

CE – Circular EconomyCBM – Circular Business Model BMI – Business Model Innovation CLSC – Closed-Loop Supply Chain

VII

Table of Contents

1.

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1

1.2 Problem Formulation and Research Gap ... 4

1.3 Purpose and Research Question ... 5

1.4 Relevance of the Study ... 5

1.5 Context of the Study ... 6

1.6 Scope and Delimitations ... 9

1.7 Thesis Outline ... 9

2.

Theoretical Framework ... 11

2.1 The Circular Economy ... 11

2.2 The Transition from Linear to Circular ... 13

2.3 Circular Business Model ... 14

2.4 The Role of the Customer in the Circular Economy ... 16

2.5 Customer Experience ... 22

3.

Methodology ... 26

3.1 Research Strategy ... 26 3.2 Case Study ... 28 3.2.1 Company Background ... 29 3.3 Data Collection ... 31 3.3.1 Interviews ... 32 3.3.2 Observation ... 33 3.3.3 Questionnaire ... 35 3.4 Data Analysis ... 36 3.5 Ethical Considerations ... 36 3.6 Research Quality ... 374.

Empirical Findings ... 39

4.1 Factors driving customers to discard their furniture ... 39

4.2 Choosing the After-Use Activity ... 42

4.3 Customer Experience Audit ... 52

4.4 Towards a Circular Economy; perceptions, roles, and responsibilities. ... 55

5.

Discussion ... 59

6.1 Motivational factors and perceived value of the after-use activities... 59

VIII

6.3 Supporting Customers in the transition to Circular Economy ... 64

6.4 Theoretical and Practical Implications ... 66

6.

Conclusion ... 68

6.1 Limitations and Future Research ... 68

References ... 70

Appendices ... 75

Appendix A Observation and Interview Protocol ... 75

Appendix B Online Questionnaire ... 77

Appendix C Questionnaire respondents list ... 80

Appendix D Analysis, themes, and codes ... 81

1

1.

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the study. First, the background describes the main concepts related to the broad topic guiding the study, followed by the formulation of the problem and the research gap. Next, the purpose, contributions, and a detailed description of the context are also presented. The final part of the chapter outlines the content of the thesis work.

1.1 Background

Biodiversity loss, water scarcity, pollution, and climate change are among the consequences derived from the unsustainable production and consumption patterns that humans have carried out over decades (UN Environment, 2019). The take-make-use-dispose economy system, recognized as the linear economy, is the term that describes the production and consumption patterns derived from the industrial era. This economic system, where inputs are transformed into waste (van der Laan, 2019), has been leading humanity to exceed the earth's carrying capacity (Salvador et al., 2020). Moreover, goods produced in this type of business model are commonly designed to have short lifespans (Salvador et al., 2020), employing a deliberate practice known as "planned obsolescence" (Bulow, 1986), where companies put pressure on customers to repeat the purchase cycle constantly. For instance, a significant amount of consumer goods such as packaging and textiles become waste at the end of their first use (EMF, 2013). Globally, only 19 percent of waste goes through material recovery via recycling and composting (Kaza et al., 2018). As a result of the overconsumption of natural resources and the generation of high amounts of waste, the planet's well-being is being affected (Salvador et al., 2020). Thus, the environmental damages caused are threatening the development of human societies and putting human life on earth at risk (UN Environment, 2019). Notably, society is becoming more and more aware of these threats and the limits of the current economic system (van der Laan, 2019). Agreements and frameworks targeted to policymakers, industry, and society, such as the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals, as well as the Paris Agreement on climate change (UN Environment, 2019), provide a broad agenda for approaching the economic, social and environmental challenges at an international level. In Europe, initiatives such as the "right to repair" proposed by the European Parliament aims to push legislations that will grant the consumers access to clear information about the repairability and expected lifespan of a product. In addition to encouraging sustainable consumer choices as well as

Introduction

2

promoting reuse by making repairs more appealing, cost-efficient, and systematic (European Parliament, 2020).

The pressure of environmental policies joined to the increasing environmental awareness of the consumers has been some of the drivers that have influence companies to rethink their offerings, processes, and business models (Julianelli et al., 2020). In this regard, as an alternative to the linear economic system, the concept of circular economy (CE) has emerged. The CE describes an industrial economic system that is "restorative by intention" (EMF, 2013). It centers on the importance of maximizing the use of products and materials, promising environmental and economic benefits by maintaining products and materials circulating, eliminating waste, and the use of natural resources (EMF, u.d.).

The transition to a more sustainable economic model will be systemic (EC, 2020), requiring transformations at the micro, macro, and meso level (Prieto-Sandoval et al., 2018). The micro level focuses on products, companies, customers and the actions required to increase the circularity (Kirchherr et al., 2017). The meso level centers on the cooperation between industries at a regional level, also defined as industrial symbiosis (Prieto-Sandoval et al., 2018). Lastly, the maso level comprehends the cooperation of institutions, governments, and policymakers for the development of environmental policies at a global and/or national level (Kirchherr et al., 2017).

An approach facilitating this transition is the design and implementation of Circular Business Models (CBMs). CBMs are business models that focus on maximizing the resources' values as long as feasible (Salvador et al., 2020) by slowing, closing, and narrowing resource loops (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017), including strategies for cycling materials such as reuse, remanufacturing, refurbish, and recycle, or extending use phase through long-lasting design, maintenance, and repair (Geissdoerfer et al., 2020).

In this new paradigm that the CE presents, the key principle centers on the idea that waste does not exist; thus, after-use products and their materials are considered as inputs to a new cycle of production and reuse (van der Laan, 2019). This aspect requires fundamental changes throughout the value chain, where certainly, customer involvement beyond the use of a product is crucial, at a micro level (customer-company), for the successful reincorporation of products and materials into the system. For instance, retailers and manufacturing companies have started to adapt their current supply chain by integrating reverse logistics strategies, thus, creating what is defined as a closed-loop supply chain (CLSC). In this regard, Esposito et al. (2016) present examples, such as the cases of apparel companies like Patagonia and the Swedish company Nudie Jeans that offer repair services in

Introduction

3

addition to recycling initiatives, where customers return their end-of-live items to the store, so the company repurpose and resell them. Similarly, Adidas provides a shoe-recycling program in Brazil, in which customers bring their old shoes to a store, then the company shreds them, transforming them into alternative fuels and raw materials.

Certainly, CE calls for the reinvention of the relationship between companies and customers (Meloni et al., 2018). In this context, where the customer is a supplier of the system, companies provide value networks that facilitate the cooperation of stakeholders and collaboration and trust through a shared responsibility for the return of products and materials (Julianelli et al., 2020).

The importance of understanding customers' attitudes, behaviors, needs concerning the transition to CE is highlighted by several authors (Hankammer et al., 2019; Schoenmakere et al., 2019; Julianelli et al., 2020), arguing that those aspects are fundamental for the successful development and adoption of products and services in the CE context. Similarly, in innovation management literature, den Ouden (2012) calls for a depth understanding of the customers' motivational values, particularly for developing value propositions for transformational innovations.

Those aspects are precisely the focus of this study. This study employs the case of the furniture retail company IKEA specifically its recently opened IKEA Second-Hand store. Such store is a pilot project where the company is testing a CBM based on the return of products from its customers in the way of donation, meaning that customers voluntarily and with no incentives give back their furniture to the company to be resold. However, in this case, the customer does not return the products directly to the company. Instead, they do so via the product return process enabled by the infrastructure that IKEA's stakeholder ReTuna provides. The case allows investigating the customer experience in the after-use phase, thus, understanding customers' attitudes, behaviors, needs, desires, and perceptions in their transition to CE from their perspective.

To give clarity to the reader is essential to highlight that in this study, the term after-use phase is after-used to describe the stage where the products are reintroduced to the circular system by the customer. Thus, the phase where the customer takes the role of supplier. Moreover, the term customer is employed as an umbrella term to describe the user, end-user, and consumer.

The following sections provide a more extensive explanation of the study, its purpose, context, and delimitations.

Introduction

4 1.2 Problem Formulation and Research Gap

As industries and society embark on a new age of transformation (den Ouden, 2012), multiple perspectives must be considered while developing new products, services, and business models aligned with CE principles (EC, 2020). The transition to a sustainable economic model constitutes significant challenges for all actors involved. Certainly, as den Ouden (2012) points out, transformations require changes in attitudes, performance, and characteristics. Undoubtedly, consumer behavior is crucial for facilitating the transition to CE (Schoenmakere et al., 2019). It is clear that habits and behaviors inherited from the linear economy must change. To achieve this, initiatives that encourage more sustainable and circular behavior and the implementation of mechanisms that support customers in adopting new circular practices are fundamental.

The current linear economy is characterized as being an open-loop model that places the customer at the end of the process (Salvador et al., 2020). However, that is not the case in the CE. Here, the customer takes an important role in the system, not only as a consumer of circular products but also as a supplier of the circular system, by taking their old products back into the system once their needs have been fulfilled. For instance, customers contribute to CE by giving their used products a second chance, keeping them, their components, and materials in use for longer by suppling the loops of reuse, refurbish, remanufacture, and recycle (EMF, u.d.). Although customer needs are the basis for value proposition development for CBMs (Hankammer et al., 2019), the role, perspectives, and desires of the customer in the CBM have been disregarded in CE literature (Kirchherr et al., 2017; Prieto-Sandoval et al., 2018; Hankammer et al., 2019; Salvador et al., 2020). In this regard, Hankammer et al. (2019) highlight that empirical understanding of customer requirements and goals is essential for companies to adjust their products and services, particularly in times of transformation. Hence, it is relevant to acknowledge and address this gap in order to support the transition to CE from the customer perspective. Concerning this, this study employs the specific case of a furniture retail company transitioning to CE testing a CBM that depends on the customer as a supplier of after-use products. Thus, the case illustrates the challenge of maintaining the resource supply faced by the company and provides the context for exploring customer experience in the after-use phase of their products, their needs, goals, and requirements during the take-back journey.

Introduction

5 1.3 Purpose and Research Question

The purpose of the following study is twofold. Firstly, by making use of the case study of the CBM of a furniture retail company, it aims to investigate aspects of the transition from linear to circular business model from its customer's perspective. The study is focused on understanding the activities carried out by customers in the after-use phase of a product, in this case, furniture, specifically during the reintroduction of used items into the circular system. Thus, providing valuable insights resulting in practical implications aimed to strengthen the CBM of the case company. Secondly, this study aims to identify opportunities and provide recommendations on how retail companies can support their customers transitioning to CE. Recommendations are based on the customer's challenges, desires, and needs identified during the research process about their role as suppliers of the circular system.

Certainly, customers play an essential role in the adoption of circular practices (Salvador et al., 2020); ultimately, they are who will decide if they accept it or not. Therefore, learning about their challenges, desires, needs, and perceptions is a fundamental step in the transition to CE. In this sense, and in order to explore the phenomenon from the customer's perspective and to understand what is required for customers transitioning to the circular economy to give their used products a second life, the study is guided by the following research questions:

Three research questions:

• RQ1 .- How do customers perceive their responsibilities and role in the after-use phase of a product in the circular economy?

• RQ2 .-What is the value that the customer gains by giving their used products a second life? What motivates them?

• RQ3 .-How can companies support their customers while transitioning from linear business models to circular business models?

1.4 Relevance of the Study

The study contributes to the field of innovation management in connection with business model innovation and the transition from linear to circular economy. It offers practical implications in investigating the challenges, needs, desires that customers encounter in the transition to circular practices, thus, provide recommendations on how retail companies can support their customers in this transition. Moreover, it contributes to filling the existing knowledge gap in CE literature concerning customer disregard by exploring and reporting the customer perspective on the transition from linear to the circular economy in the retail furniture industry.

Introduction

6 1.5 Context of the Study

The study is carried out in collaboration between academia and the retail industry, being the home furnishing retailer IKEA the case company.

The case company is undergoing an ambitious transformation of transitioning from a linear to a circular business model by 2030. To accomplish this goal, IKEA is developing and implementing diverse strategies focused on prolonging the life of products, components, and materials. Such strategies aim to enable their customers to acquire, care for and pass on products in circular ways (IKEA, 2020a). In this regard, the company is testing new profitable circular business models such as the Circular Store, where products collected from the buy-back program are resold at the IKEA shopping centers. Another example is the IKEA Second-Hand store located in the recycling mall ReTuna in Eskilstuna, Sweden, where the study's context lies. This second-hand pilot store opened in November 2020. Here, by using the infrastructure provided by ReTuna (Figure 1), the donated items are sorted, cleaned, repaired, and inspected before being exhibited and resold in the IKEA second-hand store inside the mall.

Introduction

7

ReTuna recycling mall and återvinningscentralen (ÅVC), the recycling center in English, are run by the energy company Eskilstuna Energi och Miljö (EEM), a

municipally-owned company. ReTuna has positively contributed to sustainability and CE in the region since its inauguration in 2015 (Retuna, n.d). It offers an infrastructure where old items are given a new life through repair and upcycling. Strategically located next to the recycling center (Figure 1), visitors who wish to donate their used items (electronics, clothing, furniture books, etc.) do so via the depot Returen. After receiving the item, Returen staff, employed by ReTuna via the municipal work integration program AMA (Eskilstuna municipality's resource unit for Activity, Motivation, and Work) (Retuna, n.d), perform an evaluation and decide

whether it is in condition to be reused or not. In the case that the item is damaged beyond repair, it is then taken to the recycling center. Items that are in condition to be reused are distributed to the 14 shops in the mall, including IKEA, then the shop staff clean and repair the items following their own quality standards. Lastly, the products are exhibited and sold, providing them a new life.

The products sold at the second-hand store are offered with a full warranty and return policy terms. Moreover, all the products meet the same safety requirements as those sold in all IKEA stores (IKEA, 2020b). For this reason, the company does not resell donated products that might represent a risk to the new owners. For instance, upholstered furniture, lamps, textiles, and children's products are not considered for reselling since they cannot guarantee the product's safety by restoring it and cleaning it with the resources they currently have (IKEA, 2020b). However, this type of furniture is only sold at the second-hand store if it comes from exhibition copies from the IKEA shopping center in Västerås (Retuna, n.d).

To offer a clearer overview of the context, Figure 2 illustrates the way that IKEA products are reintroduced to the system through a product recovery process supported by ReTuna.

Introduction

8

Figure 2 Product Return Flow at IKEA Second-Hand Store – Context of the study

This pilot store at ReTuna, which is part of a global innovation project within IKEA, is projected to be open until November 2021. During this time, the company's goals are to understand better several aspects, such as why their products turn into waste and their condition when discarded. Moreover, they aim to understand how customers reason when deciding to throw away IKEA products and explore the customer's interest in buying second-hand IKEA products directly from them (Ingka Group, 2020). Likewise, learnings and experiences from this pilot store are aimed to be used to explore the potential of this service in other markets (IKEA, 2020a). Lastly, since its inauguration, customers have shown great interest in the repaired products sold in the second-hand store, which have resulted in significantly high demand. Consequently, this high demand also represents a challenge for the company. For instance, the business model of the IKEA second-hand store relies on customers donating their old products to maintain profitability. Here is where the challenge of maintaining a resource supply arises. Hence, the phenomenon that this study investigates is the role of the customer in the CBM, more specifically, their role as supplier, their experience, and perspectives reintroducing their old products into the circular system.

Introduction

9 1.6 Scope and Delimitations

This study focuses on the customer's perspectives on transitioning to circular practices centered on the product after-use phase and their experience in the take-back journey. Aiming to explore customer's needs and what is required for them to take back their old products into the circular system in a profitable circular business model. Meaning that once the customer has decided to donate, sell, give away their old items, these will be reused, remanufactured, refurbished, or recycled, offering them a second life. This study does not cover the consumption of second-hand products aspect.

This qualitative research is designed to understand the phenomenon bounded in the context of the IKEA second-hand store in Eskilstuna, Sweden. By employing non-probability sampling methods, subjects considered for the study obey the following characteristics: 1) People that donate their old furniture at Returen, 2) Individuals that recycle their old furniture at the recycling center, 3) People that sell, donate, give away their used furniture making use of other means that the one in the immediate context (e.g., through buy and sell digital platforms)

1.7 Thesis Outline

This first chapter has offered a glimpse of the study. The following chapters deep dive into the details of the study as it follows:

• Chapter number two presents the theoretical framework, where the key concepts encompassing the study are discussed: the circular economy, the transition from linear to the circular economy, and its implications. Moreover, a brief description of the circular business model is also offered, followed by a discussion about the role of the customer in the circular economy and activities carried out during the after-use phase. Lastly, the definition of customer experience is also presented.

• The study's methodology is set forth in chapter number three, where the research strategy is outlined, including a description of the qualitative case study where the background of the case company is detailed. Additionally, data collection and analysis methods are also presented, followed by the ethical considerations and the approach for assessing the research quality.

Introduction

10

• The research questions are answered in Chapter five. Moreover, the study's practical and theoretical implications are described.

• Lastly, the thesis closes with chapter number six, in which the conclusions of the study, the limitations, and future research, are put forward.

2.

Theoretical Framework

This chapter provides definitions and analysis of the diverse theories, frameworks, and concepts that are the base of the study. Firstly, the concept of circular economy is presented—secondly, the transition from linear to circular economy explores the factors driving it—moreover, the concept of circular business models and the role of the customer in the CE are discussed. Lastly, the concept of customer experience is described.

2.1 The Circular Economy

The 18th century marked the beginning of an era of important transformations for humankind. The use of novel materials and new energy sources paved the way for implementing innovative techniques for production, transportation, and distribution of goods leading to tremendous economic growth. As a result, this period of transformation known as the Industrial Revolution brought prosperity to many and changed society through technological and economic development (den Ouden, 2012). On the other hand, economic activities that have been carried out since then are responsible for biodiversity loss, pollution, and water scarcity and are strongly linked to the drivers of climate change (Schoenmakere et al., 2019).

Salvador et al. (2020) draw attention to the fact that we live in a time where the benefits of the industrial systems of the past have become threats for modern society and business. As den Ouden (2012) points out, in times like this, "We can choose to be paralyzed in despair, or we can choose to see the abundance of opportunities that these multiple crises bring" while highlighting that many innovative solutions are often generated in times of crisis and change. In this sense and as an alternative to the take-make-use-dispose, namely linear economy, which is material and energy-intensive (EMF 2013) and has led society to surpass earth's carrying capacity (Salvador et al. 2020), the concept of Circular Economy (CE) has emerged. CE promises a solution to this challenging global outlook. Here, products do not become waste; instead, they are reused, and their value is extracted to the maximum before safely returning to the environment (EMF, 2013).

Early concepts and core elements of the CE were presented in the "The Economics of the Coming The Coming Spaceship Earth" disclosure by Boulding in 1966, being formalized decades later by Pearce and Turner in the early 1990s (Salvador et al., 2020). For the past decade, the concept has gained considerable attention from the scientific community, becoming an important field of academic research

Theoretical Framework

12

(Geissdoerfer et al., 2017). Notably, such increased attention to the topic coincides with the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF) influential work that has framed and further popularized the concept outside academia (Geissdoerfer et al., 2020). For instance, the European Commission introduced in 2015 the CE strategic action plan for a systematic and transformative transition followed by a renewed version in 2020 with the aim to accelerate this transition (EC, 2020).

EMF defines CE as "an economy that is restorative and regenerative by design that aims to gradually decouple growth from the consumption of finite resources" (EMF, 2017). Furthermore, Geissdoerfer et al. (2020) provide a more comprehensive definition in which CE is defined as an "economic system in which resource input and waste, emission, and energy leakages are minimised by cycling, extending, intensifying, and dematerialising material and energy loops. This can be achieved through digitalisation, servitisation, sharing solutions, long-lasting product design, maintenance, repair, reuse, remanufacturing, refurbishing, and recycling."

Figure 3 Circular Economy System Diagram – Ellen McArthur Foundation (Meloni et al.,

2018)

According to EMF (2017), CE is guided by three principles: 1)Design out of waste and pollution.

2)Keep products and materials in use. 3)Regenerate natural systems.

Theoretical Framework

13

These principles are the basis for the development of sustainable strategies for design, produce, consume, and use products in circular ways. Moreover, Figure 3 visualizes the CE system where the materials (biological and technical) cycle through the system. Biological materials cycle into cascades, whereas technical materials do it through processes of repair/maintenance, reuse, remanufacture/refurbish and recycling (EMF, 2013).

Lastly, the CE represents systemic transformation (EMF, 2017; EC, 2020) that requires a shift in the ways of how industries produce, customers consume, use and dispose of, and how policymakers legislate (Prieto-Sandoval et al., 2018) in order to achieve a full-scale industrial transformation. Undoubtedly this is a challenging quest. However, CE provides a framework for redesigning the economic system where creativity and innovation are exploited in favor of the transition to a more sustainable economy (EMF, 2013).

2.2 The Transition from Linear to Circular

As highlighted in the previous section, CE is here aiming to transform the economic and industrial system. According to den Ouden (2012), a transformation is essential to counter the plentiful negative effects of the industrial age. Similarly, Stahel (2016), as cited in (Prieto-Sandoval et al., 2018), indicates that "concerns over resource security, ethics and safety as well as greenhouse-gas reductions are shifting our approach to seeing materials as assets to be preserved, rather than continually consumed".

In the context of CE, the major challenge of the transition to a more resourceful and sustainable economy relies on changing the behaviors, ecosystems, infrastructures, and legislations that have co-developed over the years, enabling the linear economy (Schoenmakere et al., 2019). Moreover, transformations take place in micro (products, companies and customers), maso (industries), and macro (cities and governments) levels involving the society as a whole (Prieto-Sandoval et al., 2018), requiring the active engagement and contribution of multiple stakeholders (EC, 2020).

Prieto-Sandoval et al. (2018) present three determinants in the transition to CE shown in Figure 4. These three elements are in a sense interconnected, complementing and supporting each other. For instance, legislation refers to the regulations and policies, the overall legal framework that influences, supports, and motivates both customers (consumption) and suppliers (production) to adopt sustainable practices. Moreover, the production determinant encompasses the suppliers who produce according to the regulations and offer sustainable products and services that are aligned with the customer demands. Lastly, the consumption

Theoretical Framework

14

determinant refers to customers and their willingness to accept circular products and services and acquire sustainable behavior. (Prieto-Sandoval et al., 2018)

Figure 4 Circular Economy Determinants Based on (Prieto-Sandoval et al., 2018)

Innovation is a vital component of the CE transition strategy. For instance, the EC (2020) states that the drivers of the transition are "the innovative models based on a closer relationship with customers and digital technologies." Similarly, Schoenmakere et al. (2019) argue that the transition depends on "the emergence of innovation in technologies, social practices, organizational forms, and business models." Likewise, EMF (2013) claims that the shift to a CE "has direct implications for the development of novel business models that create value in novel ways."

Geissdoerfer et al. (2020) argue that Business Model Innovation (BMI) is seen as fundamental for industrial practitioners since it enables a systematic shift on an organizational level towards a CE. In addition to this, in a content analysis on CE literature, Kirchherr et al. (2017) conclude that the primary enablers of this transition are new business models and the customers willing to adopt new practices. In this regard, Salvador et al. (2020) indicate that incorporating elements of CE on current business models will ease the adoption of CE practices among both organizations and customers as opposed to implementing radical changes that might constitute a more significant challenge in the acceptance of CE (Salvador et al., 2020).

2.3 Circular Business Model

The essence of a business model represents the way an organization creates, delivers, and captures value (Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010), as cited in Geissdoerfer et al., 2020). BMI constitutes the transformation, diversification, acquisition, or development of new profitable models, affecting the entire individual

Theoretical Framework

15

of a combination of its value creation, delivery, and capture elements (Geissdoerfer et al., 2020). Hence, the concept of Circular Business Models (CBM) is situated under the umbrella of BMI. CBM is the combination of the core aspects of a business model with the CE principles. In other words, CBMs are viable and profitable models designed, adapted, or transformed to run circular systems that aim to maintain resource value at its maximum for as long as feasible while eliminating or reducing waste (Salvador et al., 2020).

Organizations are able to implement different strategies in order to transform or adapt their current business models towards a CE context. Geissdoerfer et al. (2020) define CBM as "business models that are cycling, extending, intensifying, and/or dematerialising material and energy loops to reduce the resource inputs into and the waste and emission leakage out of an organisational system. This comprises recycling measures (cycling), use phase extensions (extending), a more intense use phase (intensifying), and the substitution of products by service and software solutions (dematerialising)". This definition highlights four generic strategies for the development of new value propositions presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5 Circular Busines Model Strategies (Geissdoerfer et al., 2020)

Note that the strategy identified as "cycling" involves the implementation of after-use activities such as reafter-use, refurbish/remanufacture and recycle where the key element relies on effective take-back systems and the willingness of the customers to take part in it in order to enable the circularity of the products and its components.

Theoretical Framework

16

Moreover, in CE, a new approach to the supply chain involving the take-back journeys is fundamental for the successful implementation of CBMs. A close-loop supply chain (CLSC) is a system that enables the circularity of products, materials, and components via the reverse logistic process. According to Schenkel et al. (2015), as cited in van der Laan (2019), closing the loop offer four types of values for businesses:

• Sourcing value: refers to the direct financial impacts, such as lower-cost sourcing of products, components, and materials and the avoidance of negative outcomes, such as disposal fees and environmental fines.

• Environmental and social value: communicating product recovery initiatives to relevant stakeholders providing a green corporate image may lead to improved brand image.

• Customer value: new services and products offered through product recovery activities may lead to higher customer satisfaction and loyalty.

• Information value: collecting and inspecting products can provide essential information to improve product design and optimize the close loop value chain. The following section describes what is found in CE literature as the desired role and contributions of the customer in the CE, specifically on the after-use phase, and offers a more detailed view of CLSC.

2.4 The Role of the Customer in the Circular Economy

Organizations aim to create and deliver value for their customers in return for economic profit via business models. Ultimately, the value propositions developed on the business strategy hold the elements that influence customer satisfaction and loyalty towards the company and its offerings. The customer is notably important for a successful transition towards the CE. This is because on the customer relays the acceptance or rejection of the CBM value propositions as well as the willingness to adopt new behaviors that enable the CE.

In order to have a better perspective of the new role that the customers play in the circular economic system, it is relevant to bring up to the discussion the traditional or current economic system, namely the linear economy, and highlight the differences.

Theoretical Framework

17

Figure 6 Linear Economy

In the linear economy (Figure 6), which is characterized as a forward supply chain, the customer is simply situated at the end of the process (Salvador et al., 2020). In this linear system, materials are extracted, transformed into goods, followed by the use phase, and lastly thrown away. During the after-use phase of the linear system, the product and its components directly become waste, often ending up in landfills, restricting the possibilities of recovering its value. In other cases, the value from discarded products and their materials may be extracted if recycled properly; nevertheless, this is contextual and depends on the available waste management infrastructure and legislation. Moreover, as (van der Laan, 2019) points out, recycling is a low-level recovery activity. Although it helps reduce waste, it does not recover other inputs such as energy, water, and labor employed in the manufacturing process.

A critical aspect of the linear economy is the business models based on producing goods with short useful lifespans, namely "Planned Obsolescence" (Bulow, 1986). This practice puts pressure on customers to constantly repeat the cycle of purchase, use, and disposal since goods are designed to last a single use (Salvador et al., 2020). This deliberate practice that manufacturers implement helps them increase sales volumes while consuming resources and generating large amounts of needless waste. Hence, a common practice is the "perceived obsolescence," where goods became obsolete merely due to their aesthetic aspect being considered outdated or unfashionable even though being entirely functional. As a result, this type of production and consumption practices have led to the overconsumption of natural resources, negatively impacting the environment.

In the CE, the role of the customers goes beyond just consuming circular products. Here, the customer's participation is notably important, taking a new role in the value chain becoming a supplier of the system. For instance, in the CE, the customers are expected to take the products, their material, and components back into the system during the after-use phase, supplying the loops of repair, reuse, remanufacture, refurbish, and recycle. Figure 7 illustrates the role of the customer

Theoretical Framework

18

in CE in the after-use phase, where there is a return flow from customers to producers and service providers (van Boerdonk et al., 2021).

Figure 7 Customer Role in the CE. Adapted from CE system diagram (EMF, 2017)

In the CE literature, academics and practitioners offer resource life-extension strategies that serve as starting points for developing value propositions in the context of CE. For instance, Reike et al. (2018) provide an extensive review on the strategies enabling CE, also called value retention options, in which the "10R framework" is the most comprehensive. 10R stands for refuse, reduce, resell/reuse, repair/maintain, refurbish, remanufacture, repurpose, recycle, recover (energy), and re-mine. In this regard, among the ten value retention options presented in the 10R framework, five of those are closely related to the after-use phase where the customer is involved: repair/maintain, reuse/resell, refurbish, remanufacture and recycle. Accordingly, in this study, those five value retention options are referred to as CE after-use activities. During these activities, the customer's involvement and participation are vital to keeping the products and materials in the circular system extending its life.

Although CE literature presents these after-use activities in a general manner, and the role of the customer has somehow been assumed, a better definition of the key activities that the customer is required to carry on every after-use activity is needed. Reike et al. (2018) offer a more detailed description of the after-use activities describing the key activities required to carry both the customer and service provider. Such insights are presented next in Table 1.

Theoretical Framework

19

Table 1 CE After-Use Activities. Adapted from (Reike et al., 2018) and (EMF, n.d)

The transition towards CE at the micro-level (companies and customers) requires shifting from the linear supply chain into a circular one (van der Laan, 2019). A CLSC is a forward supply system that incorporates reverse logistics to close the loop. According to van der Laan (2019), CLSCs are determined by the context (nature and reason of the customer returning the product), the supply chain driver for recovering the product (economic, social responsibility, or legislation), recovery method (recycling, value-added, direct reuse) and the stakeholders involved in the closed-loop.

Based on Agrawal et al. (2015) literature review, product acquisition, collection inspection and sorting, disposition, and disposal are identified as the key activities carried on the reverse logistics process.

CE After -Use Activity Key Activity – Customer Key Activity – Service Provider Repair/ Maintenance

Repair or replace faulty parts of a product so it can be used with its original function.

Restore the functionality of the product by repairing or replacing deteriorated parts.

Reuse

Resell

Buy second-hand or find a customer for their no longer used product (which is still in good condition and fulfills its original function).

Possibly some cleaning, minor repairs are required.

Buy, collect, inspect, clean, sell.

Refurbish Return for service under contract or dispose.

Restore an old product and bring it back to date. Replacement of key components might be necessary.

Remanufacture Return for service under contract or dispose.

Use parts of a discarded product in a new one with the same function. Decompose and recompose.

Recycle Dispose of separately; buy and use secondary materials

Acquire, check, separate, shred, distribute, sell. Process material to obtain the same quality.

Theoretical Framework

20

Figure 8 Closed-Loop Supply Chain. Based on (Agrawal et al., 2015)

Figure 8 visualizes the interaction between the forward and the reverse supply chain where the brand owner initiates the close loop in collaboration with the customer. The first stage, product acquisition, refers to the process commonly performed by retailers where used products are acquired from customers/end-users to further processing (Agrawal et al., 2015). Manufacturers can collect products from diverse collection points, for example, directly from customers, through retailers, or third-party logistics services. As the condition of the collected product may vary, an inspection of each item is required (Agrawal et al., 2015). Lastly, an assessment of the quality of the recovered product is essential (van der Laan, 2019); the results of this assessment guide the decision towards the next stage of the product. In the disposition stage, depending on its quality, the product may continue its life cycle through after-use activities such as repair, reuse, refurbish, remanufacture, recycle, or it can be disposed.

Although customers have the freedom to decide what happens to their products after they have used them, research in the second life of consumer electronics (Meloni et al., 2018) shows that consumers have limited awareness of the value of used products and knowledge of how to return them, being this a barrier in the CE activities. Moreover, companies aware of this barrier and realizing that placing the

Theoretical Framework

21

burden of reverse logistics entirely on the customer is not an effective strategy (Esposito et al., 2016). New ownership structures, as described by (Hankammer et al., 2019), can mitigate this burden by increasing the business's responsibilities via service-based strategies where the producer keeps the ownership and control over the product, increasing the likeability that product can be repaired, refurbished, reused (Salvador et al., 2020). Other approaches offer incentives to the customers to motivate them to return their old products to the manufacturer, such as buy-back programs. However, Esposito & Tse (2016) suggest that instead of financial incentives, companies should start by building stronger relationships with customers based on "shared values and responsibilities" by creating awareness and effectively communicating their efforts to reduce waste (Esposito et al., 2016). To elaborate further on that, taking the customer's perspective, the reason for participating in the closed-loop process may vary, as the return of old products can be intrinsic or extrinsic motivated. For instance, companies may extrinsically motivate their customers to return old products through incentives in their take-back systems such as buy-take-back or reward programs. For example, the company HP offers a "trade-in" option where used equipment is exchanged for credit toward a new product of the brand and a "return for cash" option where the customer hand in their old equipment and receives monetary compensation.

In this regard, a study conducted by Das & Dutta (2016) in the CLSP with incentive-dependent returns shows that when more incentives the customer are offered for their old products, the collection rate of used products increases. However, this also adds more cost to the collection process. Therefore, companies must determine the optimal incentive amount to be offered, so the profits are maximized (Das & Dutta, 2016).

On the other hand, behaviors motivated by social responsibility such as donation to charity for altruistic reasons are often intrinsically motivated. The act of donation is driven by emotions and sympathy for the cause. Moreover, according to Oppenheimer & Olivola (2010), donation provides emotional incentives to the donator, such as enjoyment, instant gratification, empowerment, inspiration, and happiness. However, the authors highlight the risk of monetary incentives in prosocial motivated behaviors, arguing that this might cripple the social utility of the action, moving those behaviors from social to the economic realm (Oppenheimer & Olivola, 2010).

In the context of CE, an example of donation-based business models is the second-hand store Stockholms Stadsmission in Sweden. The organization is charity-based and works with social care, work integration, and education. This social enterprise profits from selling donated items to fund their social programs while creating benefits for the environment reducing waste. In this sense, coming back to what Esposito & Tse (2016) suggests, companies can recover products from customers

Theoretical Framework

22

interested in sustainable practices and social responsibility, values that must be shared between company and customer.

2.5 Customer Experience

As argued in previous sections, the transition towards a more sustainable economic system requires changes in behaviors and attitudes inherited from the unsustainable linear economy. Moreover, these changes must be permanent and embraced by as many people in order to make a significant impact (den Ouden, 2012). The author den Ouden (2012) acknowledges that in order to influence behavior change at a large scale and persuade people to embrace new attitudes, the solutions must provide a positive and pleasurable experience that addresses their motivational values. Experience is a distinguishing factor in an organization's offering. It focuses on the cognition and emotional level (Norman, 2013) with the intention to provide positive and enjoyable interaction with the organization and its offerings.

In literature and practice is often found a distinction between the term user and customer experience. The former is commonly employed in design, information technology, human-computer interaction (Norman, 2013), whereas the latter is commonly used in marketing (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). The user experience (UX) is the set of emotions, perceptions, behaviors, and responses that a person goes through while interacting with a system, service, or product in a determined context of use (ISO, 2019). On the other hand, the customer experience (CX) comprehend the same set of aspects; however, it concentrates not only on one single interaction but instead focuses also on the journey and relationship between the customer and the organization and its offering before, during, and after the consumption of the offering (Schallehn et al., 2019). That said, it is important to point out that for this study, both terms are used indistinctly given that the CX is a term used to describe the UX over long periods and the close relationship through the consumption journey between the organization and the customer (Salazar, 2019).

The different interactions between the customer and the organization during the journey are called touchpoints. Lemon & Verhoef (2016) identify four types of touchpoints through the customer journey, those are: 1) Brand owned, 2) Partner owned, 3) Customer-owned, and 4) Social/External. Moreover, the authors also externalize that nowadays, the diverse channels and media available are allowing customers to interact with companies (and vice versa) in an increasing number of

Theoretical Framework

23

touchpoints adding complexity to the journey. Consequently, this has evoked the recent focus on organizations on improving the CX (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). The touchpoints represent instances in the journey where the company can make choices to add customer value. In the context of CE is during these instances where customers can also make choices regarding their participation in after-use activities (van Boerdonk et al., 2021).

By deconstructing and analyzing the customer journey, companies can better understand the customer's options, choices, and motivation during the different phases; as a result, areas of improvement may be identified. Moreover, the customer journey analysis should understand and map the journey from the customer perspective; therefore, it requires customer input (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016).

In the CE context, the relationship between companies and customers is no longer merely based on one-time transactions. Instead, it aims for a long-term relationship that ensures product recovery. Therefore, a customer journey in the CE setting must include activities, goals, needs, and touchpoints that support the after-use phase. den Ouden's (2012) value framework suggests experience as a value proposition at the user level. The value framework is divided into four levels of value 1) user, 2) organization, 3) ecosystem, and 4) society. In addition, it integrates views from social sciences as four perspectives of value: economy, psychology, sociology, and ecology. In this regard, the author indicates that the overall experience must provide value for their money, contribute to their happiness, enable them to be a member or belong to a group that is important for them, and lastly, allow them to minimize the effects on the environment. Table 2 summarizes the value for the customer in creating CX according to den Ouden,(2012) value framework.

Table 2 Overview of Value for the Customer, Based on (den Ouden, 2012)

ECONOMY Value for money

Use-Value The value of an offering that the user perceives. It can be determined by how useful it is to a determinate person or situation.

Exchange

Value The amount of money a user is willing to pay for the offering

PSYCHOLOGY

Happiness

Human Values

Standards that guide actions, choices, judgment, among other characteristics, that define the self as a competent and moral member of the society. Those standards are determinate and learned from society and its institutions.

Motivational Values

1) Power: Social status and prestige.

2)Achievement: Personal success according to social standards.

3) Hedonism: Pleasure & gratification of oneself.

Theoretical Framework

24

5) Self-direction: independent thought and action choosing. 6)Universalism: understanding, appreciation, and protection for the welfare of people and nature. 7)Benevolence: Preservation and enhancement of the welfare of people that is close.

8)Tradition: Respect, commitment, and acceptance of customs and ideas.

9)Conformity: Restraint of actions and impulses likely to violate social norms.

10) Security: Safety, harmony, and stability. (Schwartz, as cited in den Ouden (2012)

Positive Psychology

Focuses on positive experiences. Determinants or drivers for: Contentment & satisfaction for the past, optimism for the future, and happiness and well-being in the present.

SOCIOLOGY Belonging

Symbolic Value

The personal meaning given to an offering that does not relates to its value in use.

Sentimental

Value Value perceived on an item that relates to emotions its history evokes on a specific person.

ECOLOGY

Eco-Footprint Human development The search of needs and satisfiers or solutions to develop and live according to their needs and interest.

Similarly, Schallehn et al. (2019), in a study on CX creation for after-use products, summarizes seven main categories related to customer value, where the subcategories represent the characteristics that determine the CX in the purchase phase of circular products. (Figure 9). This categorization is based on the value typology proposed by Holbrook (1994), which captures the economic, social, hedonic, and altruistic components of perceived value (Sánchez-Fernández & Iniesta-Bonillo, 2007).

Theoretical Framework

25

It is relevant to point out that neither den Ouden's (2012) nor Schallehn's et al. (2019) customer values have been developed specifically to address the CX in the after-use phase. The former takes a holistic perspective of value, while the latter focuses on the customer value in the acquisition phase. However, these categorizations serve as a framework for analysis of the tangible and intangible, extrinsic and intrinsic, and emotional cost/benefits, namely customer value perception in the context of this study.

To conclude, CX can offer a competitive advantage to organizations. It allows them to connect with customers at an emotional level creating a solid bond and, as a result, establishing loyalty towards the organization and its offerings (den Ouden, 2012). In this regard, Hankammer et al. (2019) argue that organizations must commit to exploring their customers' underlying needs to identify new value propositions. However, it is relevant to acknowledge that a superior CX may represent an extra cost for the provider. Schallehn et al. (2019) suggest focusing on cost-efficient processes in order to ensure that the offering is financially viable.

21

3.

Methodology

This chapter gives a comprehensive description of the methodology employed in the research process of the study. The first sections present the research strategy, followed by the case study and case company description. Moreover, the data collection methods, data analysis, and finally, the ethical considerations are also described.

3.1 Research Strategy

As presented in Chapter 1, the purpose of this study is to investigate aspects of the transition from linear to circular business model from the customer's perspective. Therefore, by employing a qualitative case study as the methodology, the objective is to understand the activities carried out by customers in the after-use phase of furniture and their perceptions and opinions on the reintroduction of old items into the circular system. Thus, the study is defined as a qualitative case study. Taking interpretivism as the philosophical position or inquiry paradigm, the study centers on the understanding of participants' experiences. Interpretive research, also referred to as constructivism (Creswell, 2013; Merriam & Tisdell, 2016), assumes that there are multiple realities which are socially constructed. Thus, meaning is constructed rather than found (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016).

Although the study essence is the understanding of customers perceptions and experiences towards a specific phenomenon, which in this case is the transition to the CE and their role as a supplier of the circular system, the research strategy could fall in what Creswell, (2013) classifies as the phenomenological research methodology. However, as Merriam & Tisdell (2016) argues, in general, all qualitative research is to some extend phenomenological, this is because, through qualitative research, the researcher tries to "uncover participants' understandings of their experiences." Therefore, this study is categorized as a qualitative single case study, due to that the phenomena investigated explores a "real-life, contemporary bounded system" (Creswell, 2013). To offer a more straightforward overview of the research implemented in this study Figure 10 provides a visualization of the research design.

Methodology

27

Figure 10 Research Design

Moreover, the research process (Figure 11) is structured in four phases: initial exploration, data collection, data analysis, and results or conclusions. A brief description of the research phases is offered next:

• Initial exploration: The first phase of the study encompasses de exploration and problematization of the case, the definition of the research question, and the scope of the study. This was done in close collaboration with the case company, IKEA, through regular (weekly) meetings with the local market manager. Moreover, site visits specifically in ReTuna (the recycling mall) where the IKEA second-hand store is located, Returen (the donation center), and Återvinningscentral (the recycling center). Additionally, informal interviews with employees on-site also were carried out.

Moreover, during this phase, the theoretical framework was defined. To do so, a literature review on the main topics connected to the research questions was carried out. The review included peer-reviewed journal articles and book chapters. The search was conducted using diverse keywords, such as circular economy, customer or consumer, experience, reuse, product recovery, closed-loop supply chain. Search strings evolved as new concepts related to the research topic emerged during the article reviews. The databases used were Scopus, Science Direct, and Google Scholar. Moreover, snowballing and cited reference search, specifically in literature review articles, was an alternative approach employed to access additional articles. Lastly, a supplementary approach to search included books and articles belonging to the program course literature.

Data Analysis -Thematic Analysis

Data Collection Methods - Interviews, Observations, Questionnaire Methodology- Qualitative Case study

Approach - Inductive

Methodology

28

• Data collection: Three sources of data collection have been selected; interviews, observations, and questionnaires. The selection of participants was based on individuals who have experienced the phenomenon (Creswell, 2013). Hence, a purposeful sampling strategy was implemented during interviews and observations in Returen and the recycling center, whereas a voluntary response approach was implemented on the questionnaire.

• Data analysis: This phase was carried out in parallel with data collection, which consisted of thematic analysis of each interview and observations followed by presentation and discussion of the findings with the case company.

• Results: the final stage of the process is the presentation of results, conclusions, where findings are interpreted and presented.

Figure 11 Research Process

A more detailed explanation of each phase of the research process is presented in the following sections and chapters.

3.2 Case Study

Case study research, as defined by (Creswell, 2013) is a "qualitative approach in which the investigator explores a real-life, contemporary bounded system (a case) or multiple bounded systems (cases) over time, through detailed, in-depth data collection involving multiple sources of information (e.g., observations, interviews, audiovisual material, and documents and reports), and reports a case description and case themes." This methodology is relevant in exploratory research; on one hand, it is beneficial not only for understanding a contemporary phenomenon but also for studying the effects of change or innovations (Martin & Hanington, 2012).