Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=wasw21

Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership

& Governance

ISSN: 2330-3131 (Print) 2330-314X (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wasw21

Framing Standardization: Implementing a Quality

Management System in Relation to Social Work

Professionalism in the Social Services

Kettil Nordesjö

To cite this article: Kettil Nordesjö (2020): Framing Standardization: Implementing a Quality Management System in Relation to Social Work Professionalism in the Social Services, Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, DOI: 10.1080/23303131.2020.1734132

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2020.1734132

© 2020 The Author(s). Published with license by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC.

Published online: 02 Mar 2020.

Submit your article to this journal

View related articles

Framing Standardization: Implementing a Quality Management

System in Relation to Social Work Professionalism in the Social

Services

Kettil Nordesjö

Centre for Work Life and Evaluation Studies, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden

ABSTRACT

This article describes and analyzes how standardization is framed and adapted in relation to social work professionalism, by investigating how a regulation on quality management systems is implemented in a Swedish social service organization. A decoupling between department and unit frames enables the organization to fulfill objectives of organizational professionalism and external legitimacy while professionals can participate in the formulation of procedural standards relating to an occupational professionalism. Tensions are delegated to street-level. An implication is the possibility for managers and professionals to adapt standards to a professional practice, although this may undermine the uniformity of standards.

KEYWORDS

Standardization; professionalism; framing; quality management

1. Introduction

The increasing standardization of human service organizations (HSOs) through assessment tools and management systems has sought to promote accountability, legal security, transparency and effective and uniform services. However, the significance of standards, which are explicit, written, formal and connected to the norms of a certain practice (Brunsson & Jacobsson, 2000), for social work professionalism, e.g. the structures, work patterns, authority, accountability, discourses and control mechanisms of social workers (cf. Evetts,2009), remains contested.

On the one hand, following standards can lead to unreflective practitioners, a fear of making errors, and hindering of innovation in a profession that demands flexibility and discretion in order to fit the variety of needs (Ponnert & Svensson, 2016). Standardization may also require critical-thinking skills and reflexive awareness among professionals, and such informal logics may be unsupported from a policy level (cf. Broadhurst, Hall, Wastell, White, & Pithouse, 2010).

On the other hand, an increase in rules and routines may create contradictions between rules and a need for professional assessments (Evans & Harris, 2004). Standardization may also be used to legitimize and strengthen a professional practice (Skillmark, Agevall Gross, Kjellgren, & Denvall,

2017), by moving from “gut feeling” and relating professional legitimacy to evidence-based work (Barfoed & Jacobsson,2012; Boaz et al.,2019).

The future may not lie in the rejection of standardization, but “to find a balance between

flexibility and rigidity and to trust users with the right amount of agency to keep a standard sufficiently uniform for the task at hand.” (Timmermans & Epstein, 2010, p. 81; cf. Robinson,

2003). Such balance and potential adaptation of standardization to a professional context must deal with tensions between values such as accountability and efficiency on the one hand, and professional integrity on the other.

CONTACTKettil Nordesjö kettil.nordesjo@mau.se Centre for Work Life and Evaluation Studies, Malmö University, Malmö 205 06, Sweden

© 2020 The Author(s). Published with license by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way.

One way to investigate standardization’s relation and potential adaptation to social work profes-sionalism is to explore how different actors in an organization make sense of– or frame – the same form of implemented standardization. Actors’ framings are relevant for the study of implementation in street-level bureaucracies where social workers’ and managers’ discretion is high and policy is created in an ongoing process of meaning construction that needs to be grounded in organizational practices (cf. Cornelissen & Werner,2014; Lipsky,2010).

The aim is to describe and analyze how standardization is framed in relation to social work professionalism, by investigating how a nationwide regulation on quality management systems (QMS) is implemented in a Swedish social service organization. In a QMS, social work is organized in procedural standards such as processes, activities and routines in order to ensure accountability and the quality and uniformity of services. The focus in this article is on the how rather than the what, i.e. on how actors frame standardization rather than the use and content of standards. The guiding research questions are: (1) How is the QMS framed by actors in a social service organiza-tion? (2) What are the framings’ implications for the relationship between standardization and social work professionalism?

The study is relevant to research on standardization and professionalism in social work by empirically demonstrating how standardization correspond to different purposes and uses for different actors in a HSO. Also, research on problem framing has focused little on how local actors frame problems during policy implementation (Coburn, 2006; cf. Gray, Purdy, & Ansari, 2015). Managers, implementers and professionals may gain insights from how the article problematizes the conditions for the adaptation of standardization in terms of participation and compatibility with every day practice.

2. Standardization and social work professionalism

Standardization regulates and calibrates social life by rendering the modern world equivalent across cultures, time, and geography (Timmermans & Epstein,2010). Standards are often disseminated by experts, and can be a way to embed authority in rules and systems (Brunsson & Jacobsson,2000). To find a balance between the flexibility and rigidity, implemented standards need to be adapted to a professional practice, in a way contrary to the uniform purpose. Although they may not work as intended due to a flawed adaptation, they should not be considered failures since a standard’s flexibility might be key to its success (Timmermans & Epstein,2010).

The procedural standards studied in this article do not specify properties or performance, but how processes are to be performed and steps taken when certain conditions are met (Timmermans & Berg, 2003). For example, an application for social assistance is sorted into the process “social assistance”, where procedural standards in the form of activities (what is done, e.g. meet client) and routines (how is something done, e.g. what questionnaire is used) specify the forms of social work administration but not necessarily the content (the case is described in more detail insection 4).

Standardization is significant for HSOs, which cannot handle the complexity in human needs with the limited services at hand (Hasenfeld,1983). Clients need to be categorized, as when they are fitted to units based on specific client characteristics through assessment tools. In this perspective, standardization suppresses individuality in the service of industrial conformity (Timmermans & Epstein, 2010). In addition, in order to receive legitimacy from society, standardization may be promoted in the name of“customer focus”, “visibility” and “equal service”, which may correspond to the professional ethics of social work (Ponnert & Svensson,2016).

Two ideal types of social work professionalism (Evetts,2009,2010) can illustrate two simplified relations to standardization. First, procedural standards lie close to an organizational professional-ism where social work is based more on organizational and bureaucratic ideals than on professional values and expertise. It is characterized by rational-legal authority and hierarchal responsibility. Professionals are subjects to accountability, resulting in the continuous control, monitoring– and standardization– of social work. Expert knowledge manifests in standards, making professionals

accountable to the conformity to standards rather than the standards themselves. Second, in the occupational professionalism, social workers are trusted by both clients and employers and have wide discretion and occupational control of the work. They are expected to explain their actions and considerations from the perspective of research, experience, and clients. There is collegial authority and associations and institutions monitor social workers’ ethics. Below, these two ideal-types are used to understand what kind of professionalism that framings of standardization are based on.

3. Framing as an analytical concept

Framing has had longstanding and wide applications in the social sciences (Cornelissen & Werner,

2014). To Goffman (1974), a frame is an interpretive lens through which individuals perceive and interpret the world and occurrences in this world. Frames organize experience and guide action, thereby rendering life occurrences meaningful to individuals and collectives, such as managerial practices (Boxenbaum,2006).

In this article, frames consist of problems, solutions and normative rationales concerning the QMS. Frames turn our attention to how meaning is constructed collectively, interactively and strategically. They are collective action frames, i.e. “action-oriented sets of beliefs and meanings that inspire and legitimate the activities and campaigns of a social movement organization” (Benford & Snow, 2000, p. 614). Frames are also interactional co-constructions, rather than isolated and individual knowledge structures, and strategic since managers purposefully may try to shape the frames of others in an organization (Cornelissen & Werner, 2014) to mobilize others to support a direction or change (Kaplan,2008). New frames can be introduced in an organization for different reasons. For example, importing an external master frame means linking a frame to those of successful social movements, such as the quality movement, in order to get a generalized cultural resource which can give the frame legitimacy (cf. Gray et al.,2015).

In order to analyze how the QMS is framed by different actors, three core framing tasks are used as analytical tools (Benford & Snow,2000; Snow, Rochford, Worden, & Benford,1986):

(1) Diagnostic framing: a problem and an explanation of its causes are identified.

(2) Prognostic framing: the proposed solution is contrasted to earlier or dominant solutions, which are delegitimized. To be successful, the solution needs to be theorized and linked to interests, norms, and values among potential allies.

(3) Motivational framing: actors present compelling arguments and a normative rationale to support the solution.

For the purpose of implementation, it is important to ground a frame in actual organizational practices. Otherwise, it will be difficult for actors to understand and accept a particular framing and its implications, in turn making it a cognitive and symbolic process (cf. Cornelissen & Werner,

2014). In this article, these organizational practices are Evetts’ (2009,2010) two previously described ideal types of occupational and organizational professionalism. In order for a frame to be accepted by a target group, it needs to resonate with the type of professionalism of the intended group. Such resonance consists of credibility, i.e. the consistency between the frame creator’s beliefs, claims, and actions, the fit between the frame and events in the world and the credibility of frame articulators. Also, the salience of a frame depends on how essential it is to the lives of the targets of mobilization, whether it is congruent with the everyday experiences of the targets of mobilization, and whether the frame is culturally resonant in relation to the targets’ cultural narrations (Benford & Snow,2000).

In sum, the analytical approach is to use the core framing tasks to identify the frame of a certain actor (e.g. department) and see how it resonates among another actor (e.g. unit). Each frame may be related to a type of professionalism, enabling or hindering resonance, thus determining the success

or failure of a frame in the organization. The process of analysis is further described in the next section.

4. Case and methods

This section describes the case, data collection and data analysis.

4.1. The case of the implementation of SOSFS 2011:9

The research design is a single case study, enabling a depth of observation and analysis necessary to understand the framing processes of actors on different levels (cf. Hartley,2004). The

implementa-tion of the regulaimplementa-tion SOSFS 2011:9 for management of systematic quality work (henceforth “the

regulation”), is a case of how standardization is framed in relation to social work professionalism. Since 1998, the Swedish Social Services Act has stated that interventions should be of good quality, and that the quality of services should be systematically and continuously developed and assessed. Quality is defined as when“an organization complies with the requirements and objectives of the organization under the laws and other regulations” (NBHW,2011a, p. 4). The regulation describes a QMS and was published in 2012 by the government agency the National Board of Health and Welfare (NBHW).

All 290 Swedish municipalities are required to adapt the regulation to their own social services, together with the staff, by identifying and structuring processes and routines for their different units from input to output to ensure the realization of the regulations, goals, and demands of the organization (NBHW,2011a). A process contains a series of activities and routines that in the end satisfy a need. For example, an incoming application for social assistance may be processed in the activity“receive application”, which is a first step to satisfy the absence of financial resources. Each activity has a result that triggers a new activity, and each activity can contain routines on how to perform a certain activity. They can refer to both administration and interventions. Processes, activities and routines are thus procedural standards that specify steps in how to carry out social work. Although the regulation does not specify the processes, routines or content, municipalities are

required to work in a“wheel of improvement” (NBHW,2012):

(1) Identify, describe and plan the work in processes and routines, make risk analysis (2) Work according to processes and routines and identify deviations, receive complaints (3) Monitor and evaluate results and analyze deviations

(4) Develop and improve the organization on the basis of information from 1–3

In this sense, the regulation is on the one hand top-down, mandatory and coercively enforced through components and requirements, and on the other hand bottom-up and adaptable, since it must be tailored to the organization. A study by the NBHW (2017) noted that the agency employed a top-down implementation strategy, where information on the regulation was posted on the NBHW website, without much support on how to adapt the QMS to one’s own municipality. Municipalities found the concept of QMS difficult to relate to unless you were a quality specialists. They were two causes of a slow and halted implementation.

The implementation was studied on three levels: the NBHW, the department for personal social services in a district of a Swedish municipality and the department’s two units for child welfare and social assistance. The department was chosen due to reports on the far-reaching work with their QMS in different units. Following an international (Kim & Kao, 2014) and Swedish (Tham & Meagher,2008) pattern for welfare workers, the two units had a high caseworker turnover, indicat-ing potential work environment problems and insufficient resources (cf. The Swedish Work Environment Authority,2018).

The units were both people-processing and people-changing (Hasenfeld, 1983), meaning they both categorized clients for other parts of the social services and work with face-to-face social work to improve clients’ situation. Still, the unit for social assistance contained more administrative activities than child welfare, making it an area of the social services potentially easier to standardize. Also, particular to the Swedish context is the way in which the Social Services Act does not give much guidance in individual cases, giving managers and caseworkers extensive discretion in individual assessment (cf. Thorén,2008). A QMS may thus challenge this discretion in both people-processing and people-changing units.

4.2. Data collection

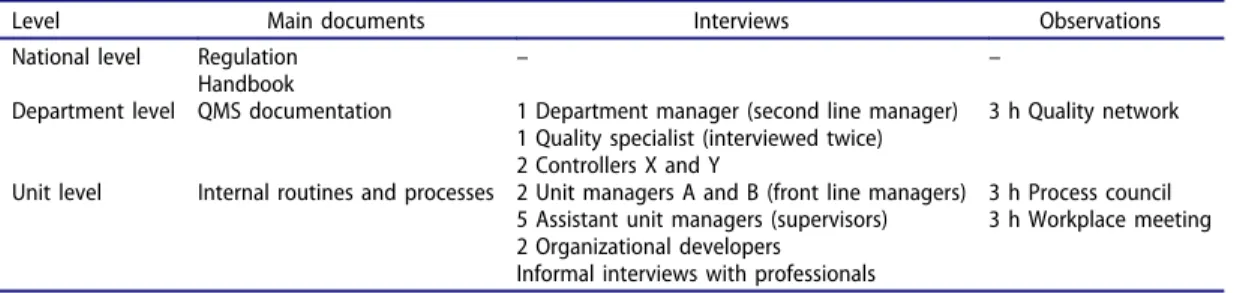

Data consist of interviews, observations and documents related to the NBHW and the social services department and units (summarized inTable 1). On a national level, data consisted of the regulation and a handbook. Earlier research was consulted to problematize the rationales for the implementa-tion. On department and unit levels, the department manager was contacted and an invitation for an interview was sent to staff who were said to be involved in the implementation of the QMS. Out of seventeen persons, thirteen agreed (nine women, four men). Two unit and one department manager have managerial responsibility in the implementation. Five assistant unit managers supervise profes-sionals and are a link to professional practice. Two controllers assisted the department manager and two organizational developers worked with the QMS in each unit. Lastly, a quality specialist had formulated the QMS and organized the implementation. All interviewees, except one of the controllers, had a bachelor in social work and experience of social work practice.

All were interviewed individually, except for the controllers and organizational developers who were interviewed in pairs. The quality specialist was interviewed twice. First in the beginning to grasp the idea of the QMS, then in the end to discuss practical challenges and implications. Interviews were made and recorded by the author in the interviewees’ workplace during two weeks 2018 and lasted 60–120 minutes. The interview guide was semi-structured with the themes background, the idea and purpose of a QMS, the implementation of the QMS, the use of the QMS and how a QMS might affect social work. It had been pilot tested and adjusted in another municipality prior to the study.

The author also made nine hours of passive participant observations where the QMS was discussed: a process council, a work place meeting and a quality meeting. The author was seated in the background and observed how problems and solutions of everyday professional social work related to the QMS were discussed, and who addressed them. For example, in the unit-specific process council, organizational developers and caseworkers discussed how to develop, revise or remove routines to make the QMS more effective. Observations were essential to capture case-workers’ views on the QMS, both by listening to discussions and by short informal interviews at breaks. Observations were summarized in memos by the author afterward.

Table 1.Data collection.

Level Main documents Interviews Observations National level Regulation

Handbook

– –

Department level QMS documentation 1 Department manager (second line manager) 1 Quality specialist (interviewed twice) 2 Controllers X and Y

3 h Quality network

Unit level Internal routines and processes 2 Unit managers A and B (front line managers) 5 Assistant unit managers (supervisors) 2 Organizational developers

Informal interviews with professionals

3 h Process council 3 h Workplace meeting

Finally, documents concerning the QMS were obtained from the quality specialist. Templates, processes, routines and general information about the local implementation gave an understanding of the QMS in theory and practice.

The research project has been subject to ethical review and approved by a Swedish regional ethical review board. Information about the study, interview and observation was sent in advance, and informed consent was obtained from all interviewees and participators in meetings.

4.3. Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and organized in the Nvivo 11 software along with documents and observational memos. All data was then analyzed by the author in four steps. First, it was read in full to get a sense of the overall implementation and organized in relation to the three levels. On the third level, actors were also grouped in two units.

Second, the three core framing tasks were used as analytical themes to construct frames. A diagnostic framing referred to what problems needed to be addressed with a QMS, and what caused these problems. For example, the department emphasizes the problem of lack of control and monitoring. A prognostic framing referred to descriptions of the solution and what made earlier solutions inade-quate. For example, the NBHW intended for the regulation to be less abstract and theoretical than before and be used to plan, lead, control, monitor, evaluate and improve all parts of the social services. A motivational framing referred to what actors wanted to achieve with their solutions and what their long-term goals were. For example, transparency and support structures for social work practice are arguments for a QMS on a unit level. This analysis of conceptions and arguments resulted a generalized frame on each level that could have similar or different sub-themes from other levels.

Third, Evetts’ (2009, 2010) two ideal types of professionalism were compared to the frames in order to understand what professional values they were built on. Internal inconsistencies in the frames and differences between actors and levels could then be found. For example, the unit frame seems to correspond to both an organizational and occupational professionalism.

Fourth, the resonance of one level’s frame on another level was analyzed in terms of credibility and salience. For example, the NBHW frame is considered credible on department level, since the agency is referred to as an articulator of regulation and recommendations of the social services.

Together, the data analysis shows how the QMS is framed in relation to social work profession-alism and how frames resonate in the organization. Although primarily theory-driven, the analysis also generated sub-themes inductively, thus swaying back and forth between theoretical concepts and empirical data, and between different steps (i.e. abduction, Alvesson & Sköldberg,2009). The trustworthiness of results is addressed as a question of transparency. The methods and data are described as thoroughly as possible to invite the reader to assess the plausibility of the analysis. However, a balance between a thick and a concise description must be considered, where frames have structured the presentation of results (cf. Larsson, 2005). Also, the findings were presented, discussed and tested in dialogue with the interviewees (communicative validity, Kvale,1997). 5. Framing a quality management system

This section describes the results through three frames: the frame of the NBHW, of the social services department and of the units of child welfare and social assistance.

5.1. The NBHW frame

In a diagnostic framing, the NBHW has stated that profound restructuring and reorganization of human services are in progress due to cost efficiency, while quality standards still remain (NBHW,

1999). Adding to this problem, the municipal level lacked a formalized system for ongoing govern-ance, monitoring, and evaluation of quality and results (NBHW, 2011b). This is relevant not least

due to the importance of“keeping your back safe” in light of demands from informed clients and consumerism (Hall,2012). Another related problem was the risk of a shutdown of the NBHW in the 1990s due to rationalization and regionalization (Hall,2012).

In a prognostic framing, regulating through a QMS became a solution to all of these problems. It was a way to create an integrated organization at NBHW, control the municipalities and give them tools to govern, monitor and evaluate results and quality. However, the NBHW saw the municipal implementation of the previous regulation as unadaptable, slow, not covering all relevant areas and as a top management issue, often excluding unit managers and professionals (NBHW,2011b). Also, municipalities viewed the previous regulation as too detailed, theoretical, and abstract (NBHW,

2009). Instead, the new regulation stated that managers should implement the QMS together with professionals. By structuring tasks in processes and routines, it would be possible to plan, lead, control, monitor, evaluate and improve all parts of the organization as a learning organization in

a“wheel of improvement” (NBHW,2012).

The long-term purpose in the motivational framing is to make sure that the right thing is done at the right time, in the right way. Keeping things in order prevents actions that could lead to harm for clients, i.e. deviations from the demands and goals applicable to the organization in relation to laws and regulations (NBHW,2012). In this way, the benefits for clients increase, but also for citizens in general since the QMS makes organizations more cost-efficient.

The NBHW frame promotes an organizational professionalism. The structuring of the social services makes it possible to find deviations that need improvement in the everyday practice of social work, making sure the right thing is done at the right time in relation to predetermined procedural standards. For the NBHW, this is an answer to problems of governance, consumerism, and cost-efficiency. The target group is the managerial levels, although professionals should be involved in the implementation.

5.2. The department frame

On the department level, an organizational professionalism continues to dominate. In the diagnostic framing, interviewees on the department level touch on three interrelated problems. First, the department manager called for tools “which are of practical, governing, planning and monitoring use.” Second, the large caseworker turnover leads to a lack of continuity and structure, which in turn threatens quality: “I can’t phrase it in any other way; [turnover] is a huge risk. How can one not think it would affect the quality of support to children?” (quality specialist). But the most frequent problem addressed is the external pressures to implement the regulation. Apart from being legally required by the NBHW, all other city districts seemed to have a QMS. However, this proved to be a misconception:

It was basically a collection of documents. There was some kind of list of routines and responsibilities. But it was very difficult to get a grip on the how when reading their documents. There was a great confusion (Quality specialist).

In the prognostic framing, no interviewee mentioned the earlier NBHW regulation. There is a citywide management system that does not concern quality, but instead the department’s goals and resources which are of a“constantly changing political agenda” (Department manager). The department’s solution, the QMS, was built by the quality specialist, who made processes for the district, departments, and together with the units. Their QMS is similar to the idea of NBHW, i.e. to work in a wheel of improvement. Many processes and activities for department and units are defined and accessible on the intranet, which units are supposed to fill with routines. Responsibilities are assigned and there is a yearly management review. However, some interviewees perceive the QMS as disconnected from the units. A controller reflects on whether the QMS is for the unit or department level:

It is still a library of documents where you can see the units’ processes. But how this will help and develop and strengthen the unit managers work in the management system… I don’t see it if I’m to be honest. (Controller

Y: It’s supposed to be a support?) Yes, but where’s the support between us at the department level and the unit managers in the management system? Are there other parts that we do not have access to? (Controller X) One reason for this disconnection may be that a QMS is abstract and difficult to understand. Initially no one on department level understood the concept, but after the quality specialist and the controllers had taken training courses, they realized the scope of creating and implementing a QMS (“not weeks, but years!”, quality specialist).

The difficulties of the concept are also apparent in an observation of a quality network meeting, where the quality specialist gathers all the department’s controllers and organizational developers to discuss how to proceed with the implementation of the QMS. All units reported different problems, needs, and conceptions of the purpose, use and responsibilities of the QMS. Where the solution is consistent to the quality specialist and department manager, its interpretations seem to vary greatly between units.

The interviewees on a department level describe a motivational framing with two QMS purposes. First, and consistent with the NBHW frame, it is a way to govern the organization, in order to analyze and make sure citizens get the services they need and have a right to:

The social services are very law-based. We have political goals that we should transform into action, and it’s important for me to know how to do it, how we know that we do it, and that the services we provide here have quality, that those who come here and have needs, that these needs have been met as far as possible. In this respect, I try to see that this system helps us. What do the services look like, what do they consist of and can they be changed? In a way we are working on continuous improvements. […] When we get audited, it’s practical when someone has complained about something that happened. Then it’s great to have this idea. Where in the process did this happen, where is the problem, is there something we missed? (Department manager)

Second, and not in the NBHW frame, a QMS brings transparency and support structures to social work practice. Routines and processes clarify how a task should be carried out, the department manager says, making the QMS valuable when there is a lack of management support. A controller expresses a similar view:“instead of running to the manager, you have to access the QMS and look, where do I find myself in the process?” (Controller X). These transparency and support structures are said to lead to improved work life conditions, the quality specialist says, since they reduce stress:

[When you have] mapped processes and structured and accessible guides and support documents, this in itself is stress-reducing. Especially in an organization that is in constant crisis, such as child welfare or social assistance, where staff turnover can be 100% [per year]. […] I think that the implementation of quality structures is stress-reducing. If you have new caseworkers all the time, purely hypothetical (laughter), you have to work with constant introductions. To be able to show a process. This is how we work. Here are the guidelines, these are the manuals. (Quality specialist)

Like the NBHW frame, the department frame promotes an organizational professionalism. Although the frame touches on social work support structures and improved work life conditions, these issues are still founded on the organizational type where a QMS, through predetermined rules and routines, can support social work practice and facilitate introductions. Although the QMS is formulated from the top of the organization, some interviewees perceive the QMS as separated from unit level.

5.3. The unit frame

In the unit frame, an organizational professionalism co-exists with an occupational professionalism. The units’ diagnostic framing consists of a lack of structure, transparency and work environment problems. In unit B (social assistance), an external investigation had been initiated due to low scores in a citywide user survey. According to an assistant unit manager, it showed that there was a great variation in how tasks were carried out due to a difficulty of finding information and routines. There was also a high caseworker turnover, resulting in sick leave that was both a cause and an effect of a poor working environment at that time. Interviewees in unit A (child welfare) touch on the lack of knowledge from monitoring and evaluation, that could help to clarify which interventions work:

Once we’ve made an intervention, we hurry to the next. When do we know that it has given the desired result? Or can it be that we halfway through the intervention realize that it doesn’t need to be as extensive as we thought, and that we can use the resources for someone else? Such things need to be improved. […] We can’t just feel our way through this. We must be able to measure it, and that must be based on a management system that works. (Unit manager A)

As on the department level, there is no mention of earlier NBHW regulation in the units’ prognostic framing. Asked how they assured quality prior to the QMS, organizational developers say they either made individual assessments based on professional knowledge that could differ between social workers depending on experience, competence, and organizational context. Or, they used shared folders containing routines and support documents that were seldom updated, and could vanish or be duplicated (unit B):

It was confusing. You don’t know what is valid. When I started here, the unit almost lived without routines, creating an uncertainty about what we actually do. So, the management system created a more structured way to support those who work here. (Organizational developer B)

Interviewees in the two units have different conceptions of the QMS. In unit A, the QMS is barely known, and neither implemented nor used. Although the quality specialist has provided an overall QMS structure based on joint workshops, there are still many pieces missing, says the organizational developer in unit A. The unit manager finds the use of the QMS unclear:

I would say that it is not sufficiently anchored in the organization as a whole that this is the way to do things. Rather, that it would be great if you do it. (Unit manager A)

In unit B, the department’s QMS has been partly merged with the unit’s digitally accessible and widely used“regulatory document” (RD). It was a result of the external investigation and contains over 100 pages of unit-specific processes and routines.“Every answer to every question you have can be found in the RD”, an assistant unit manager says, making it a safety net for unforeseen consequences, and a library to refer professionals to when they have question about how a certain task should be performed. Another part is the process council, where unit representatives (including caseworkers) regularly meet to discuss and decide on suggested revisions of the RD.

Hence, unlike unit A, a bottom-up participatory process of standardization is taking place in unit B. Interviewees in unit B and professionals in observations, describe it as meaningful and a shared way of working, although it is unclear for them how the RD connects to the department’s QMS.

In the motivational framing, there are two main arguments, both similar to the department frame. First, the QMS is once again a tool for governing and monitoring social work. However, the earlier frames’ focus on finding and handling deviations is not present on unit level. Instead, an assistant unit manager (unit B) says she gets a better overview of what is going on, who is responsible for what, and to whom she can delegate tasks. Second, a QMS can bring transparency and support structures, although on unit level, “keeping things in order” is more a question of social work practice than of external legitimacy. Mapping processes and routines clarifies what is reasonable or functional or not to do, for a unit or professional within a certain task description. It makes the introduction of new employees easier, and the temporary absence and increased caseloads due to turnover and sick leave, can be managed through routines.

However, the organizational developers are ambivalent about the feeling of safety that routines bring. The considerable growth of checklists, manuals, regulations, and systems in the last ten years has made the social services anxious, says an organizational developer, creating a fine line between a QMS as support and control:

We’ve become a very anxious organization, employees feel that someone can be confronted with something at any time.“It’s best to have a routine, so that I won’t be hanged”. Now I’m exaggerating … […] We’re supposed to go back to being professional, after all, we’re academics who’re supposed to be able to reflect and to do balanced assessments without checklists. And this anxiety becomes devastating. It affects our clients in the long run. You say no and maybe reject an application, and then it will be appealed, because you’ve been too anxious to make an individual assessment. Of course we should reject when it’s suitable. But not because we don’t dare

to make an assessment. So it’s really a balance. A management system is good as long as it is supports and develops practice, but it becomes a burden and problem when there is anxiety. The shift to trust management, or what to call it, will be tough. Because the social services are hierarchical and controlling and anyone can be hanged… (Organizational developer A)

In tandem with this reasoning, the other organizational developer says it is important to also remove unnecessary routines when new ones are added and to leave room for social workers to decide how to manage a task themselves. This proves to be difficult in a process council, where the RD is discussed and revised. A caseworker says that on the one hand, a certain routine is not used, nor updated. On the other hand, he and his fellow caseworkers are hesitant to remove it, since it feels safer to just leave it, just in case they might use it. In the end, the routine is not removed from the RD. It is later commented on:

There is a tendency not to dare to let things be loose. As soon as something is unclear, everyone requests a routine right away… you don’t dare to keep things vague, instead you want a clear routine where something is explained step by step in a checklist. It has become a drug of safety. (Organizational developer B)

Summing up, the unit frame is partly related to an organizational professionalism. Managers value the possibility to bring transparency and support structures to a social services context burdened by difficult work life conditions and a lack of knowledge of interventions. But there are also elements of an occupational professionalism. Although it has unclear ties to the department’s QMS, a participatory form of procedural standardization has emerged from unit level. Also, interviewees in both units have an ambivalence to what an encompassing procedural standardization brings to the social work profession. They are concerned about how the profession can handle the increased standardization they are a part of.

5.4. Summary

The QMS is framed in two different ways in the organization. On the one hand, there is the department frame grounded in an organizational professionalism, where a QMS is supposed to govern by finding deviations and adjusting processes and routines accordingly. This frame is closely related to the NBHW frame. On the other hand, there is a unit frame where a QMS is supposed to assist in creating social work support structures. This frame is partly related to an organizational professionalism, but also an occupational professionalism. Although managers use standards to govern professional practice, they are intended to be created and revised together with professionals. The results are summarized inTable 2.

6. Discussion and conclusion

The results have revealed a difference in frames between levels. Where the department frame is grounded in one type of professionalism, the unit frame is grounded in both types of profession-alism. In this section, this difference is discussed as a lack of frame resonance on unit level. A frame needs to resonate, i.e. perceived as credible and salient (cf. Benford & Snow,2000), in order to be accepted and grounded in social work professionalism.

First, the NBHW frame fully resonates on department level in terms of credibility and salience. Regarding credibility, the NBHW frame is linked to a master frame of quality, i.e. a frame that is widely known, frequently referenced and already infused with emotional intensity (Gray et al.,2015, p. 128). “It’s basically ISO 9001”, the quality specialist says, building on decade-old concepts of quality. Also, guidance and legal measures written by the NBHW have been shown to be considered credible among municipalities (Denvall, Lernå & Nordesjö,2014). This is also true for the depart-ment level who adopted the frame due to coercive and mimetic isomorphic pressures from the environment (Powell & DiMaggio, 1991). However, the fact that some interviewees do not see the connections between levels in the QMS may weaken the frame’s credibility.

The NBHW frame is also salient for the department level. The frame relates structure and predictability to practical management tools that are in demand among interviewed managers and controllers, and may be culturally resonant in that it presents what a manager should do– managing through a QMS. In sum, the department finds the NBHW’s quality master frame – corresponding to an organizational professionalism– both credible and salient.

Second, the department frame is partly salient and even less credible on a unit level. Regarding salience, QMS values relating to structure, predictability and uniformity seem to be important for both managers and professionals and grounded in their everyday experiences. But at the same time, these values create tensions within practice relating to the “drug of safety”.

The credibility of the department frame is more limited. Although unit managers find the problem of a large social advisor turnover and purposes of support structures and improved work life conditions relatable, there are no clear governance signals about how and whether the QMS should be used in units. Thus, where the department frame is partly salient, it lacks credibility for both managers and caseworkers, leaving room for unit-specific solutions.

The partial lack of resonance of the department frame on a unit level creates two different QMSs: a department QMS directed outwards for legitimacy and accountability reasons, and unit QMSs that are developing according their own needs. It is a pattern of decoupling (Meyer & Rowan, 1977), a deliberate separation between organizational structures that enhances legitimacy, i.e. the depart-ment quality master frame, and the organizational practices that within the organization are believed to be technically efficient, i.e. the unit frame (Boxenbaum & Jonsson, 2017). The decoupling thus risks turning the external QMS into a symbolic process.

All the same, the decoupling explains how the department and unit frames can co-exist and serve different purposes. By aligning themselves to an organizational professionalism and the department’s QMS, units are legitimizing their practice, both within the department, and possibly also externally as a social work profession. By aligning themselves to an occupational professionalism, units may influence and participate in the formulation of procedural standards and thereby achieve a“balance between flexibility and rigidity” (Timmermans & Epstein,2010, p. 81).

However, with this balance comes tensions and ambivalence on how to perform social work when professionals are conforming to procedural standards, possibly fueling anxiety and a fear of making errors (rigidity), rather than engaging with the formulation of the standards (flexibility). In this sense, the decoupling is also an organizational delegation of conflicts and contradictions in social

Table 2.Summary of core framing tasks and dominant type of professionalism on three levels.

National level Department level Unit level Diagnostic framing Risk of agency shutdown

Lack of governance of, and for, municipalities

Informed citizens, consumerism

External pressure Lack of tools for governing and monitoring

Case worker turnover and poor working environment

Low scores in survey Lack of structure,

transparency, and evaluation Case worker turnover and poor working environment Prognostic framing Critique of earlier solution: Regulation

was too detailed, theoretical, and abstract

New solution: QMS to plan, lead, evaluate, and improve

Critique of earlier solution: Citywide system lacks quality focus

New solution: QMS to plan, lead, evaluate, and improve

Critique of earlier solution: Varying practice, old and unclear routines New solution: Own

participatory QMS (“RD”) or no QMS

Motivational framing Governance and management Find deviations and adjust Benefits for service users Cost efficiency

Governance and management

Find deviations and adjust social work support structures Improved work life conditions

Benefits for service users

Governance and management Social work support structures Improved work life conditions

Type of professionalism Organizational professionalism Organizational professionalism

Organizational and occupational professionalism

work practice for street-level bureaucrats to deal with (cf. Lipsky,2010). At the same time as an arena is provided for professionals to deal with tensions between organizational and occupational profes-sional values, a formal overarching QMS can remain intact.

In conclusion, standardization has been framed in two ways in relation to two types of social work professionalism. Overall, it is framed in relation to an organizational professionalism aimed at conformity to procedural standards. On a unit level, it is also framed to support an occupational

professionalism where procedural standards are aimed at being formulated from professionals’

perspectives and needs. The tension between the two types of professionalism on unit level is handled through a decoupling of frames, creating two systems for standardization: one is directed outwards for legitimacy reasons, and the other inwards for efficiency reasons. In this way, social work professionals may strengthen their practice within their department, and legitimizing it externally together with the department.

The study have several limitations. As a single case study with a modest number of interviews, generalizability is limited. In addition, few professionals were interviewed, limiting the scope of a professional perspective that was instead captured through informal interviews and accounts from organizational developers and assistant unit managers. Also, as an organization where the regulation has been formally implemented, interviewees may have had a relatively favorable conception of standardization. Involving more professionals would shed light on how tensions and contradictions between the two types of professionalism are handled in practice.

7. Implications for research and practice

Findings suggest that standardization may benefit from being introduced and framed in relation to professionalism. Managers and implementers can offer support and reflect on how the object of implementation resonates with professionals’ social work practice in their specific organizational context. Arenas for dialogue can be used to explore a common ground between prescribed proce-dural standards and professionals’ experience and everyday social work. This may demand flexibility from all parts involved. Managers must take occupational professionalism seriously and open up standards to reflect the unpredictability and flexibility of social work. Social work professionals must reflect on how common processes and tasks of social work practice may be appropriately described and systematized for practice.

Implementing standardization in this way may be facilitated by viewing the adaptation of standards as in development and translation rather than as a predefined result (cf. Gremyr & Elg,

2014). What constitutes relevant standards must be discussed so that stakeholders’ different view-points may be revised in light of inputs of others (cf. Dahler-Larsen, 2019). Standards would be formulated and critically assessed in dialogue with both managerial and professional participation in order to be adapted to a certain practice.

This would not remove conflicts and contradictions but rather puts questions of dialogue and power in the front. But it infuses elements of exploration and experimentation and may contribute to a developmental learning where the underlying rationales for standards are made visible and discussed, thereby complementing an adaptive learning relating to standards and routinized beha-vior (cf. Ellström, 2001). Such an approach may increase the credibility of standardization and contribute to increased professional participation in the implementation of standardization.

Participation may also be important in light of the high turnover in the social services, which in this study has been a rational for standardization. Future research could investigate whether standardization is counterproductive and makes professionals leave the social services due to potential losses of professional integrity, or if they stay and use certain strategies to deal with the conflict of organizational and occupational professionalism. Also, future research could investigate how a developmental approach to the implementation of standardization may contribute to flexible standards that resonate with social work practice, or if such standards would be considered flawed

adaptations undermining and watering down the idea of accountability and uniformity inherent in standards.

Of course, this approach stands in contrast to NBHW’s top-down implementation approach with the aim to govern municipalities and supply them with governance tools. Problematizing the symbolic applications of standardization in local government could help avoid unnecessary demands for measurement that is rising fast in human services (cf. Mosley & Smith,2018). Shifting focus from failures of implementation to failures in the implementation idea itself (Weiss,1998) may therefore contribute to a discussion on the limitations of regulatory top-down implementation of standardiza-tion (cf. Martin & Williams,2019).

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on this article.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Funding

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare under Grant 2016-07220.

Practice points

Findings implicate that standardization may be more credible and benefit from being introduced and adapted to a professional practice. One way to do this could be through arenas for dialogue where a balance can be sought between standards and professionals’ experience and everyday social work. This could be facilitated by seeing rules and standards as in development rather than as a predefined result. Another practice point is the need to problematize regulatory approaches of standardization that risk being symbolic or legitimizing toward the external environment.

ORCID

Kettil Nordesjö http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3565-6563

References

Alvesson, M., & Sköldberg, K. (2009). Reflexive methodology: New vistas for qualitative research (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, USA: Sage Publications.

Barfoed, E. M., & Jacobsson, K. (2012). Moving from‘gut feeling’ to ‘pure facts’: Launching the ASI interview as part of in-service training for social workers. Nordic Social Work Research, 2(1), 5–20. doi:10.1080/ 2156857X.2012.667245

Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 611–639. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611

Boaz, A., & Davies, H. T. O., Fraser, A. & Nutley, S. M. (Eds.). (2019). What works now?: Evidence-informed policy and practice. Bristol: Policy Press.

Boxenbaum, E. (2006). Lost in translation: The making of Danish diversity management. American Behavioral Scientist, 49(7), 939–948. doi:10.1177/0002764205285173

Boxenbaum, E., & Jonsson, S. (2017). Isomorphism, diffusion and decoupling: Concept evolution and theoretical challenges. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, T. B. Lawrence, & R. E. Meyer (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism (2nd ed., pp. 77–101). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Broadhurst, K., Hall, C., Wastell, D., White, S., & Pithouse, A. (2010). Risk, instrumentalism and the humane project in social work: Identifying the informal logics of risk management in children’s statutory services. British Journal of Social Work, 40(4), 1046–1064. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcq011

Coburn, C. E. (2006). Framing the problem of reading instruction: Using frame analysis to uncover the microprocesses of policy implementation. American Educational Research Journal, 43(3), 343–349. doi:10.3102/00028312043003343

Cornelissen, J. P., & Werner, M. D. (2014). Putting framing in perspective: A review of framing and frame analysis across the management and organizational literature. The Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 181–235. doi:10.5465/19416520.2014.875669

Dahler-Larsen, P. (2019). Quality from Plato to performance. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan.https://www.palgrave.com/gp/book/9783030103910

Denvall, V., Lernå, L., & Nordesjö, K. (2014). Föränderliga strukturer: Organisering för kunskapsbaserad socialtjänst i Kronobergs och Kalmar län 2003-2013 [Changing structures: Organizing Knowledge-Based Social Services in Kronoberg and Kalmar County 2003-2013]. Department for Social Work, Linnaeus University.

Ellström, P. (2001). Integrating learning and work: Problems and prospects. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 12, 421–435. doi:10.1002/hrdq.1006

Evans, T., & Harris, J. (2004). Street-level bureaucracy, social work and the (exaggerated) death of discretion. The British Journal of Social Work, 34(6), 871–895. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bch106

Evetts, J. (2009). New professionalism and new public management: Changes, continuities and consequences. Comparative Sociology, 8(2), 247–266. doi:10.1163/156913309X421655

Evetts, J. (2010). Reconnecting professional occupations with professional organizations: Risks and opportunities. In: Svensson, L.G. & Evetts, J. (Eds..) (2010). Sociology of professions: Continental and Anglo-Saxon traditions, 123-144. Gothenburg, Sweden: Daidalos.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gray, B., Purdy, J. M., & Ansari, S. (2015). From interactions to institutions: Microprocesses of framing and mechanisms for the structuring of institutional fields. Academy of Management Review, 40(1), 115–143. doi:10.5465/amr.2013.0299

Gremyr, I., & Elg, M. (2014). A developmental view on implementation of quality management concepts. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 6(2/3), 143–154. doi:10.1108/IJQSS-02-2014-0012

Hall, P. (2012). Managementbyråkrati: organisationspolitisk makt i svensk offentlig förvaltning [Management Bureaucracy: Organizational and Political Power in Swedish Public Administration]. Malmö, Sweden: Liber. Hartley, J. (2004). Case study research. In: Cassell, C. & Symon, G. (Eds.)Essential guide to qualitative methods in

organizational research (pp. 323–333). London: Sage.

Hasenfeld, Y. (1983). Human service organizations. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Kaplan, S. (2008). Framing contests: Strategy making under uncertainty. Organization Science, 19(5), 729–752. doi:10.1287/orsc.1070.0340

Kim, H., & Kao, D. (2014). A meta-analysis of turnover intention predictors among U.S. child welfare workers. Children and Youth Services Review, 47, 214–223. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.09.015

Kvale, S. (1997). Den kvalitativa forskningsintervjun [The Qualitative Research Interview]. Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

Larsson, S. (2005). Om kvalitet i kvalitativa studier [On quality in qualitative studies]. Nordisk Pedagogik, 25(1), 16–35. Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. New York, NY: Russell Sage

Foundation.

Martin, G. P., & Williams, O. (2019). Evidence and service delivery. In: Boaz, A., Davies, H.T.O., Fraser, A. & Nutley, S.M. (Eds.) (2019). What works now?: evidence-informed policy and practice. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363. doi:10.1086/226550

Mosley, J. E., & Smith, S. R. (2018). Human service agencies and the question of impact: Lessons for theory, policy, and practice. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 42(2), 113–122.

NBHW. (1999). Ledning för kvalitet i vård och omsorg [Management for Quality in Healthcare] (Report No 1999-0-89). Stockholm: National Board of Health and Welfare.

NBHW. (2009). Sammanställning av svar på enkät angående SOSFS 2006: 11 [Compilation of Questionnaire Concerning SOSFS 2006:11] (Report No 60-11673/2009). Stockholm: National Board of Health and Welfare. NBHW. (2011a). SOSFS 2011:9 Ledningssystem för systematiskt kvalitetsarbete [SOSFS 2011:9 Management for

Systematic Quality Work]. Stockholm: National Board of Health and Welfare.

NBHW. (2011b). Utredning av konsekvenser av förslag till föreskrifter och allmänna råd om ledningssystem för kvalitet [Investigation of the Consequences of Proposals for Regulations and General Advice on Quality Management Systems] (Report No 00-7272/2009). Stockholm: National Board of Health and Welfare.

NBHW. (2012). Ledningssystem för systematiskt kvalitetsarbete – Handbok för tillämpningen av föreskrifter och allmänna råd (SOSFS 2011:9) om ledningssystem för systematiskt kvalitetsarbete [Management System for Systematic Quality Work– Handbook for the Application of Regulations and General Advice (SOSFS 2011: 9) on Management Systems for Systematic Quality Work] (Report No 2012-6-53). Stockholm: National Board of Health and Welfare.

NBHW. (2017). Implementering efter egna förutsättningar– Uppföljning av implementering av föreskrift om lednings-system i tre kommuner [Implementation According to Own Conditions– The implementation of the Regulation on Management Systems in Three Municipalities] (Unpublished). Stockholm: National Board of Health and Welfare. Ponnert, L., & Svensson, K. (2016). Standardisation—The end of professional discretion? European Journal of Social

Work, 19(3–4), 586–599. doi:10.1080/13691457.2015.1074551

Powell, W. W., & DiMaggio, P. J. (1991). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Robinson, G. (2003). Technicality and indeterminacy in probation practice: A case study. British Journal of Social Work, 33(5), 593–610. doi:10.1093/bjsw/33.5.593

Skillmark, M., Agevall Gross, L., Kjellgren, C., & Denvall, V. (2017). The pursuit of standardization in domestic violence social work: A multiple case study of how the idea of using risk assessment tools is manifested and processed in the Swedish social services. Qualitative Social Work, 18(3), 458–474. doi:10.1177/1473325017739461

Snow, D. A., Rochford, E. B., Jr, Worden, S. K., & Benford, R. D. (1986). Frame alignment processes, micromobiliza-tion, and movement participation. American Sociological Review, 51(4), 464–481. doi:10.2307/2095581

Swedish Work Environment Authority. (2018). Projektrapport“Socialsekreterares arbetsmiljö” (Project report ”The work environment of social service caseworkers). Stockholm: The Swedish work environment authority.

Tham, P., & Meagher, G. (2008). Working in human services: How do experiences and working conditions in child welfare social work compare? British Journal of Social Work, 39(5), 807–827. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcm170

Thorén, K. H. (2008). Activation policy in action a street-level study of social assistance in the Swedish welfare state (Doctoral thesis) (pp. 1404–4307; 165). Växjö, Sweden: Växjö University Press.

Timmermans, S., & Berg, M. (2003). The gold standard: The challenge of evidence-based medicine and standardization in health care. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Timmermans, S., & Epstein, S. (2010). A world of standards but not a standard world: Toward a sociology of standards and standardization. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 69–89. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102629