Picture 1: Cacao pods at plantation in Pulau Samosir, Sumatera Utara, Indonesia, Louise Nilsson, 2018.

THE BIODIVERSITY LOSS CRISIS IN

SOUTHEAST ASIA

A literature review on current research

MV109C

Miljövetenskap: Kandidatkurs VT 2019 Handledare: Jonas Lundgren & Johanna Nygren Spanne

Abstract

This bachelor thesis focuses on the biodiversity loss problematics in Southeast Asia, since it is one of the most species rich places on Earth, coupled with the highest rate of loss of species. Four biodiversity hotspots encompasses Southeast Asia which implies areas of high endemism coupled with high rates habitat loss. This thesis aim to understand what current research in the field focuses on and what ways of protecting biodiversity in the area that exists. The main driver of biodiversity loss in Southeast Asia as well as in the rest of the world, are land-use alterations; forests and natural habitat being converted to monoculture plantations, as well as agricultural- and urban expansions. Through a systematic literature review of scientific material from 2010-2019, the biodiversity research in Southeast Asia is reviewed. What the literature review concluded was that an array of environmental- as well as socioeconomic problems intensifies each other in the area, such as poverty and biodiversity loss. International cooperation to halt biodiversity loss and the global demand for products produced in the area which greatly damages ecosystems needs to be addressed urgently. Actions to halt the mass-extinction of species and their connected ecosystem services needs to be taken by providing means to organizations and to scientists that work in the area and could possibly be addressed by moving from anthropocentrism towards a biocentric nature view.

Keywords: Southeast Asia, biodiversity, ecosystem services, systematic literature review, biodiversity loss, land-use alterations, biocentrism

Svensk sammanfattning

Denna kandidatuppsats gör en ansats till att belysa biodiversitetsproblematiken i Sydostasien, som är ett område med mycket hög artrikedom som samtidigt hotas av en intensifierad förlust av arter. Fyra ’biodiversitet hotspots’ omger Sydostasien, vilka indikerar platser med hög artrikedom vilka sammanfaller med hög förlust av habitat. Det största orsaken till förlust av biologisk mångfald i Sydostasien är omvandlingen utav artrika naturtyper till monokulturodlingar, och expansionen av jordbruk och urbana områden. För att undersöka den pågående biodiversitetsforskningen genomfördes en systematisk litteraturanalys av publicerade artiklar från 2010-2019. Vad litteraturanalysen kom fram till var att flera problem, socioekonomiska samt miljöproblem intensifierar varandra, liksom fattigdom och förlust av biologisk mångfald. Internationellt samarbete krävs för att stoppa exploateringen av de värdefulla arter och naturtyper som går förlorade till fördel för den globala handeln med produkter som kommer från området. Medel för att stoppa denna biodiversitetskatastrof måste riktas till forskning och organisationer som arbetar i området. Vi bör genast agera på ett globalt plan för att förhindra förlusten av biodiversitet samt dess tillhörande ekosystemtjänster, detta skulle kunna tacklas genom att vi rör oss ifrån den antropocentriska och emot den ekocentriska natursynen.

Nyckelord: Sydostasien, biodiversitet, ekosystemtjänster, systematisk litteraturanalys, biodiversitetsförlust, markanvändning, ekocentrism

Important terms

Southeast Asia: Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines,

Singapore, Thailand, Timor-Leste, and Vietnam together forms the area (Sodhi et al, 2010b).

Biodiversity: “the variability among living organisms from all sources including, terrestrial,

marine, and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems” (CBD description of biodiversity quoted from Mcgill & Magurran, 2011, p. 292).

Biodiversity Hotspot: “the exceptional concentrations of endemic species and the exceptional

loss of habitat” (Myers, Mittermeier, Mittermeier, da Fonseca & Kent,, 2000, p. 853) Southeast Asia lies within the 4 biodiversity hotspots Indo-Burma, the Philippines, Sundaland and Wallacea (Myers et al, 2000).

Ecosystem service: A service derived from the ecosystem functions (Shimamoto, Padial, da

Table of contents

1. Introduction ... 1

1.1 Purpose and framing of research questions ... 1

2. Background ... 2

2.1 Biodiversity loss drivers in Southeast Asia ... 2

2.2 The 6th mass- extinction ... 5

3. Identifying important issues of protecting biodiversity ... 6

3.1 Biodiversity hotspots ... 6

3.2 Ecosystem services ... 7

3.3 Environmental ethics as a theoretic framework to answer the biodiversity crisis ... 10

4. Method section ... 13

4.1 Overview of the literature review ... 15

4.2 Validity of results... 16

5. Literature review ... 17

5.1 Review of biodiversity- loss articles ... 17

5.2 Review of land-use alteration articles ... 21

5.3 Review of ecosystem services articles ... 24

6. Discussion ... 27

7. Appendix 1. ... 33

1 On a daily basis we have seen scientists, experts, and environmental groups warning us about the climate crisis and the effects it will have on our planet. Sustainable development as well as climate policies as solutions to cure the climate related issues are becoming integrated parts of our societies. However, the single largest environmental problem is the rate of biodiversity loss (Sodhi et al, 2010b), still decision-makers and the media remain as silent as our forests will be within a few decades. While we are travelling to experience tropical countries, the world’s species are going extinct at alarming rates. This is evident in Southeast Asia, where habitat destruction coupled with endemism is high. We are currently living through the “6th mass-extinction”, where species are declining faster than ever in human history, this is caused by human pressure on the Earth’s support systems through various activities (Braje & Erlandson, 2013). This thesis will concentrate on the biodiversity loss in Southeast Asia, since it is the single most species rich area on Earth, with most endemic species and the area that faces the largest extinction rates caused by habitat loss. First coming across the issues of biodiversity loss in Southeast Asia, we learn that the lack of knowledge and research is a significant issue. Therefore, an attempt of researching the current (2010-2019) published scientific literature could possibly answer what research is being conducted and funded in the field in the area.

1.1 Purpose and framing of research questions

The aim of this thesis is to find out what the biodiversity conservation research conducted in Southeast Asia is focusing on through reading and analyzing recent scientific literature. The research questions aims to answer what problems that exists in the biodiversity conservation research in Southeast Asia and what ways to halt the biodiversity loss in the region that exists according to the literature.

Limits of this thesis are; limited material being reviewed in this study, limited knowledge and studies in the specific field in the region, limits of data in the region and pre-existing bias of scientific literature being conducted in the field.

2

2. Background

In this section the state of biodiversity in Southeast Asia and the “sixth mass extinction” will be presented to give the reader an insight in the current biodiversity issues of Southeast Asia. 2.1 Biodiversity loss drivers in Southeast Asia

In this section, issues that the Southeast Asian biodiversity are facing will be presented Southeast Asia is an area of great development, and the growing economy and population is rapidly changing the Southeast Asian ecosystems. Evolutionary processes on Earth and geological shifts has made the Southeast Asian region unique and created places like the many islands that together forms Indonesia, an unique country with very high species endemism. Southeast Asia has one of the highest amount of species richness, endemism and unique ecological processes in the world (Sodhi, Koh, Brook, Peter, & Nq, 2004). Unfortunately, because of the pressure on these ecosystems they are under great threat of extinction. Anthropogenic pressure of the Earth’s systems is the foremost driver of biodiversity loss worldwide and the rapid loss of biodiversity is one of our most pressing environmental problems today (Sala, Chapin III, Armesto, Berlow & Bloomfirld, 2000, Rockström et al, 2009, Vitousek, Mooney, Lubchenco & Melillo, 1997). Southeast Asia consists of Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Timor-Leste, Thailand and Vietnam and is of particular conservation concern because it has the highest rate of habitat loss of the tropical regions in the world and is estimated to already have lost 95% of its original habitat (Sodhi, 2010b).

The biodiversity crisis should become a greater concern because of the ecosystem goods and services that tropical areas provide for humans, both locally and globally. Tropical ecosystems provides many ecosystem services vital for humans, such as carbon dioxide (CO2 ) fixation, water supply and flood control, soil maintenance, and others such as ecotourism. With the essential processes that biodiversity provides to humans diminished, many conflicts will intensify. The tropical deforestation is mainly caused by land- use alterations; i.e. commercial agriculture, soybean farming, cattle ranching and palm oil plantations (Shimamoto et al, 2018). A problem, conservation-wise is that not many percent of tropical rainforests are being properly protected within national parks or reserves (Kricher, 1997) largely due to that they are in

3 developing countries. The world’s original tropical rainforests has already been destroyed to 20% and degraded severely to 40%. The cut-down rates are around 1-2% per year in Southeast Asia (Mansor, 2013).

Land- use alterations are today the greatest threat to the tropical biodiversity and the ecosystem services connected to them. Other important drivers are atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2 ) concentration, nitrogen deposition and acid rain, climate and introduction of alien species (Sala et al, 2000, Rockström et al, 2009, Foley et al, 2005, Vitousek et al, 1997). This is especially a great threat to biodiversity in tropical areas, as land-use alterations are expected to increase in the next decades (Green, Cornel, Scharlemann, & Balmford, 2005 & Sala et al, 2000). Cropland in developing countries has increased by 20% since 1960 (Green et al, 2005) but decreased in developed countries. In the future, as beforementioned it is estimated that land-use alterations will increase in tropical areas (Green et al, 2005 & Sala et al, 2000), namely, where nature protection is absent or underfunded (Kricher, 1997) and where the biodiversity is extremely high.

Picture 2: Tomato plantation and burial site on the base of a volcano in Gunung Sinabung, Sumatera, Indonesia, source: Louise Nilsson, 2018.

4 Southeast Asia is an extremely important area to concentrate conservation efforts towards due to its high rates of endemic species, as well as the rate of habitat loss and destruction. Southeast Asia is experiencing the highest rate of habitat loss in all tropic areas, and it is still increasing. There are projections that this could result in losses of 13-85% of all biodiversity in the region (Sodhi et al, 2010a). They also state that:

Southeast Asia contains the highest mean proportion of country endemic bird (9%) and mammal species (11%). This region also has the highest proportion of threatened vascular plant, reptile, bird, and mammal species (Sodhi et al, 2010a, p. 317).

This is greatly concerning not only because of the ecosystem services that these species provide humans with, but also for ethical reasons they are worth to protect. Since the development of Southeast Asia is destroying the biodiversity in the area, one of the most important issues is to create a market signal to protect biodiversity, as Squires states:

Properly priced biodiversity creates price signals and incentives that accounts for all contributions from biodiversity and ecosystems. Habitat conservation remains the centerpiece of biodiversity conservation (Squires, 2014, p. 144).

Current policies are predominantly ”command-and control”, relying on top-down compliance, which largely means, ineffectiveness and in this case, developing countries that are left with underfunded protected areas. Threatened species hotspots are found in Sumatera, Borneo, Sulawesi and Papua New Guinea (Squires, 2014) these are largely places of low income and corruption problems, which affects its wildlife conservation tremendously, many protected areas are for example, destroyed by illegal logging (Sodhi et al, 2010a). Further, Sodhi et al (2004) argues that the major challenges in mitigating the imminent threats to Southeast Asian biodiversity are primarily socioeconomic in its origin and they argue that the research in the area has been neglected in comparison to other tropical areas.

5 2.2 The 6th mass- extinction

This section should provide the reader with further examples of why we are facing a biodiversity crisis

Species going extinct is a natural process, but the current rate of extinction is 100 to 1000 times faster than the background extinction rate (Rockström et al, 2009 & Vitousek et al, 1997). It is quite impossible to calculate the species loss, since most of species are yet to be discovered. Most of (known) extinctions has happened to groups that are well-known, such as birds, we have already lost 1/4 of world’s bird species. It is estimated that 18% of mammals, 11% of birds, 5% of fish and 8% plant species are threatened with extinction (Vitousek et al, 1997). We are experiencing an ongoing mass- extinction event on our planet caused by the anthropogenic pressure on the Earth’s ecological systems, we are currently living through the geological epoch called Anthropocene (Braje & Erlandson, 2013). Scientists predicts that the “sixth mass- extinction” will result in a 50% loss of all biodiversity on Earth. This event would most likely trigger an ecologic collapse of our life upholding support systems (Braje & Erlandson, 2013).

In Holocene, the geologic epoch before Anthropocene, the carbon dioxide (CO2 ) concentrations were very stable, but the concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2 ) has increased exponentially since the Industrial Revolution begun. So by the human activities alone, we have stepped into a new geologic era, without human alterations to the environment we would still remain in Holoscene. Rockström et al (2009) presented the framework based on the “Planetary boundaries” which suggest that we have already crossed the boundaries of the rate of biodiversity loss.

The loss of biodiversity can exhaust the effect on other Earth system functions, and it interacts with several other planetary boundaries. The loss of biodiversity reduces the ecosystems ability to resist i.e. climate and ocean acidity (Rockström et al, 2009). Scientists estimate, as beforementioned that 30% of all mammal, bird and amphibian species will be threatened with extinction this century (and an additional 13% of species loss in plants and fishes, Vitousek et

6 al, 1997) and that climate change will be an even more important driver of species loss in the near future (Rockström et al, 2009).

Rockström et al (2009) points out that one environmental problem is not fixed in its state, but intensifies other environmental problems, in a sort of domino effect. The loss of habitat affects agricultural production as well, one “indirect” ecosystem service is the loss of pollinators (ex. Western Honeybee “Apis mellifera”) which ultimately will result in decreased harvests of pollination dependent plant species. Globally it is estimated that the ecosystem services provided by pollinators are worth up to $577 billion per year, this is the annual market value of global crop production directly dependent on pollinating animals (IPBES, 2016). Increased tropical deforestation also increases other threats to locals, the risk of infectious diseases such as malaria and its vectors (ex. mosquitos) in Asia and bat borne Nipah virus in Malaysia is correlating with deforestation (Foley et al, 2005).

3. Identifying important issues of protecting biodiversity

Theoretical guidelines for the thesis are presented below in the sections “biodiversity hotspots”, “ecosystem services” and “environmental ethics as a theoretical framework to answer the biodiversity crisis”.

3.1 Biodiversity hotspots

Here, the concept of biodiversity hotspots will be discussed

Biodiversity can mean many things, but most scientists and policymakers identifies species richness as a central component. That is, how many species that exists within an ecosystem. The Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD) defines it as: “the variability among living organisms from all sources including, terrestrial, marine, and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems” (Mcgill & Magurran, 2011, p. 292).

The term biodiversity was first described by naturalists in the 1800s, such as Alfred Russel Wallace (known for the Wallace-line, and the biodiversity hotspot “Wallacea” is named after him) when they started to distinguish species on how common they were (Mcgill & Magurran,

7 2011). Biodiversity has many definitions and therefore makes it hard to distinguish one clear meaning of the term. Biodiversity can be measured in many ways because of its complexity, taxa, variety, abundance, geographical occurrence etc. (Mcgill & Magurran, 2011). One of the most important ways of using biodiversity is to identify biodiversity hotspots, a vital tool in conservation planning (Mcgill & Magurran, 2011).

Myers et al (2000) definition of biodiversity hotspots is, “the exceptional concentrations of endemic species and the exceptional loss of habitat” (Myers et al, 2000, p. 853). They identified 25 biodiversity hotspots in the world in the paper from 2000. In 2019, it has added up to 36 biodiversity hotspots in the world (CEPF, 2019).To qualify as a hotspot the area must hold 0.5 (or 1500) of the world’s 300, 000 plant species as endemics (the species only exists in one place)

.

Most of the described biodiversity hotspots are in the tropics, which largely means developing countries, where threats are greatest and conservation resources are scarcest (Myers et al, 2000).The second determinant to qualify as a biodiversity hotspot is the degree of threat though habitat loss, to qualify, a hotspot should have lost more than 70% or more of its primary vegetation, 11 hotspots have already lost at least 90% and 3 have lost at least 95%. Since the four biodiversity hotspots that covers almost whole of Southeast Asia (Indo-Burma, the Philippines, Sundaland, Wallacea) has lost over 90% of its original habitat, this is arguable the most critical area for conservation efforts in the world. Out of these hotspots, 7 are in Asia and 4 are in Southeast Asia, most of Southeast Asia is considered biodiversity hotspot because of the rapid decline of habitat and the high amount of endemism (Sodhi et al, 2004). Although, some problems with the definition of what is a biodiversity hotspot still exists and are argued in the scientific community to be a too broad concept for biodiversity assessments.3.2 Ecosystem services

Here, the theory behind ecosystem services will be discussed

Humans are, through a variety of activities, altering the composition of biological communities at all scales, from local to global. “Ecological experiments, observations, and theoretical developments show that ecosystem properties depend greatly on biodiversity” (Hooper et al., 2004, p.3). The loss of biodiversity has therefore upset the market of both the market- and the non-market ecosystem services (Hooper et al, 2004). Business as usual sometimes suggests that we can provide technical solutions of losses of ecosystem services, however, this is not feasible

8 in the case of biodiversity. The destruction of biodiversity is irreversible and creates domino- effects on other biotic systems, as suggested by Rockström et al (2009). Nature is not something nice to look at, it provides our essential needs such as fresh water, food, clean air, fuel and is therefore essential to protect (Hooper et al, 2004).

There is a co-dependency, between ecologic and economic values. If we want to preserve a functioning ecosystem, our ecosystem services, we have to put a monetary value on these functions. The best way to do this is to account for a biomes’ (a specific ecosystem’s) ecosystem services, namely, the human well-being derived from letting that ecosystem simply existing (Davidson, 2013). It is, nevertheless difficult to put monetary value on the functions of our planet, especially with the future generations in mind. It is also argued that biodiversity has an intrinsic value, a value for simply existing (Davidson, 2013). However, to assess economic value on the ecosystem services in order to protect biodiversity seems to be one of the most powerful tools to protect biodiversity today.

Hooper et al (2004) breaks down the functions of ecosystems into these categories:

• Ecosystem functioning • Ecosystem properties • Ecosystem goods • Ecosystem services

The first, the ‘ecosystem functioning’ is the broadest of the four concepts, which includes the three other categories. ‘Ecosystem properties’ are for instance pools of materials, such as carbon or organic matter and rates of processes (e.g. fluxes of materials and energy among units). ‘Ecosystem goods’ are ecosystem properties with direct market value, such as food, construction materials, medicines, tourism and recreation. ‘Ecosystem services’ are those properties of ecosystems that directly, or indirectly benefits human endeavors. These are among others, maintaining hydrologic cycles, regulating climate, cleansing of air and water, pollination and storing of nutrients etc. (Hooper, 2004).

9 An ecosystem service is, as stated above, normally described as a “direct” or an “indirect” service to human well-being. “Direct” ecosystem services include the things we directly use such as food and the “indirect” ones are the underlying ecosystem processes that are needed for the direct ones to function, i.e. pollination of crops (Dänhardt et al, 2013).

The most commonly used definition of ecosystem services is the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) recited in Dänhardt et al (2013) four distinctive types of ecosystem services are suggested there:

• Provisioning ecosystem services: ex. food and water • Regulating ecosystem services: ex. climate, pollination

• Cultural ecosystem services: beauty, biodiversity, traditional knowledge etc. • Supporting ecosystem services: ex. photosynthesis

All ecosystem services are supported by biodiversity in a wide sense, valuating ecosystem services is challenging, especially for the indirect ones as their monetary value might be invisible to decisionmakers (Dänhardt et al, 2013). Another problems, that’s directly connected to the tropics is that is the lack of data on ecosystems, most research is conducted on terrestrial systems (Corlett & Primack 2006).

Ecosystem services are vital for biodiversity conservation, as it is to local people dependent on the ecosystem services. This has been a widely neglected issue when it comes to account for the well-being that ecosystem services provide in the policy debate. Chaigneau, Coulthard, Brown, Daw & Schulte-Herbrüggen (2018) describes that the problem of poverty and biodiversity loss are two of the most critical challenges in the world and that these problems are linked and that they tend to intensify at various scales.

10

3.3 Environmental ethics as a theoretic framework to answer the

biodiversity crisis

The ethical guidelines used in the thesis will be presented in this section

As previously mentioned, it is widely accepted that biodiversity loss and poverty issues are linked and that they frequently coincide at various scales (Chaigneau et al, 2018).

To live through Anthropocene is not the same for everyone, most of us in the northern hemisphere are not directly affected on a daily basis. That is not the case with the biodiversity neither the people in Southeast Asia and in the tropics. Ecological and social resilience may be linked through the dependency on ecosystems of communities and their economic activities (Adger, 2000). Traditional knowledge of ecosystems are often neglected in favor for intensified land use. Natural and social capital, as well as resilience, coevolves and coexists and are in fact both important factors of human well-being (Adger, 2004). Ecological resilience often refers to the ability for a system to recover and to maintain a steady ecological state (Adger, 2000), this system intertwines with social resilience when people are directly dependent on their surroundings. The reality of this is that poor people in developing countries are worst affected by shifts in the resilience of their surroundings, for example in the event of environmental catastrophes (Adger, 2004). To exemplify, if a poor community in Indonesia is dependent on its surrounding tropical rainforest, and an international logging company cuts it down and plants palm oil, their ecological and social resilience is being compromised as their resource availability shifts drastically.

Adaption is a dynamic social process, how we will act collectively to face environmental changes depends largely on our social capital, argues Agder (2003). The future and present effects on climate change are spatially and socially differentiated. The future impacts will be hardest on resource dependent communities. The key vulnerable groups are often excluded from making decisions on the public management of climate-related risks, this means that they are ignored in decision making processes regarding their surroundings, as the poorest households tends to be in at-risk areas (Adger, 2003). The social capital is proven to work, in many cases of risk of environmental disaster, people in at risk areas cooperate to solve the issue, in the absence of a responsible government.

11 The loss of biodiversity and the ecosystem services are deeply connected with the hardships of local people living in connection with their local nature. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) defines cultural services in terms of the ”nonmaterial benefits people obtain from ecosystems” (Daniel et al, 2012, p. 8813) these types of ecosystem services can mean cultural diversity or spirituality, religious values and more. It is since long established that climate change will affect poverty stricken areas in the world as changes like drought and temperatures will intensify. Daw et al (2016) states that ecosystem service frameworks are highly focused on ”hard values”, rather than ”soft” ones, regarding the well-being aspect. This means that the well-being derived from ecosystem services are focused on monetary values derived from that service, not the actual ”well-being” by people. This could undermine the local people’s well-being derived from that potential ecosystem service, and therefore destroy their well-being. Daw et al (2016) states that peoples’ well-being being compromised from losing ecosystem functions initially may go unnoticed until a critical threshold is passed.

Biocentrism is the worldview that puts all of earth’s beings and ecological processes as equals. It states that all beings have an intrinsic value, no matter its monetary value. It is considered the opposite of anthropocentrism, which focuses solely on mankind’s intrinsic value. Arne Næss, the philosopher behind the deep ecology movement, was one of the first to see the linkages of the disappearance of cultures to the degradation of biodiversity. This is a radical environmental philosophy indeed, but there might be a lesson or two to learn as the deep ecologists decades ago already saw the ecological (not environmental) crisis coming towards us and recognized that there had to be a shift in the way we view the world to cope with it (Næss, 1994).

Global religions, culture and ecology are closely linked. There are emerging ideological worldviews in the tropics, of ecological justice which is grounded in nature’s rights (Gudynas et al, 2017). ”Southern biocentrism recognizes the rights of Nature but does so in an intercultural perspective, is much more politicized, and is part of ’ontological openings’ to alternatives of ecological community that go beyond modernity” (Gudynas et al, 2017, p. 262). Wienhues argues that the theory of ecological justice should be biocentric, which means that all living beings should be included, instead of only certain non-human beings have moral standings of some kind. She also argues that it is quite impossible to construct an ideal theory

12 on ecological justice, since there is an irresolvable conflict between the need for humans to harm or kill other beings (Wienhues, 2017).

Borràs (2016) argues that:

the weaknesses of our environmental laws stem in large part from the fact that legal systems treat the natural world as property that can be exploited and degraded, rather than as an integral ecological partner with its own rights to exist and thrive (Bórras, 2016, p. 113).

She further argues that environmental legal frameworks has historically been developed to legalize and legitimate environmental harm, since nature is considered a legal ’property’. The differences between the anthropocentric approach to protect nature and biocentrism is that nature is not an object of protection, but a subject with fundamental rights in the latter (Bórras, 2016).

Folke (2006) says in his article about the resilience perspective and its increasing importance in understanding the dynamics of social-ecological systems, that socio-ecological resilience research is still in the explorative phase. Recent advances in the field include things like; understanding social processes such as knowledge-system integration, social networks and adaptive governance that allow for management of important ecosystem services. He further argues:

Research challenges are numerous and include efforts clarifying the feedbacks of interlinked social-ecological systems, the ones that cause vulnerability and those that build resilience, how they interplay, match and mismatch across scales and the role of adaptive capacity in this context (Folke, 2006, p. 263).

Challenges such as the one presented above is going to be discussed further in the analysis and discussion.

13

4. Method section

In this section the literature review method used will be defined and the overall literature that was reviewed will be presented in section 4.1 and ethical perspectives concerning the literature in section 4.2.

To gain a holistic understanding of the state of the biodiversity research in Southeast Asia, a systematic literature review was conducted. The Web Of Science and GreenFILE databases were used to obtain scientific material using the keywords; “biodiversity” AND “Southeast Asia” in the frame period of 2010-2019. Only peer-reviewed articles were obtained. The method was influenced by Garrecht, Bruckermann & Harms (2018) systematic review of empirical studies. A PRISMA Flowchart (see figure 1) (preferred- reporting system of items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses statement) based on the method of Garrecht et al (2018) was used to systematically find scientific material for the literature review.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow-chart for systematic literature review, modified from Garrecht et al (2018).

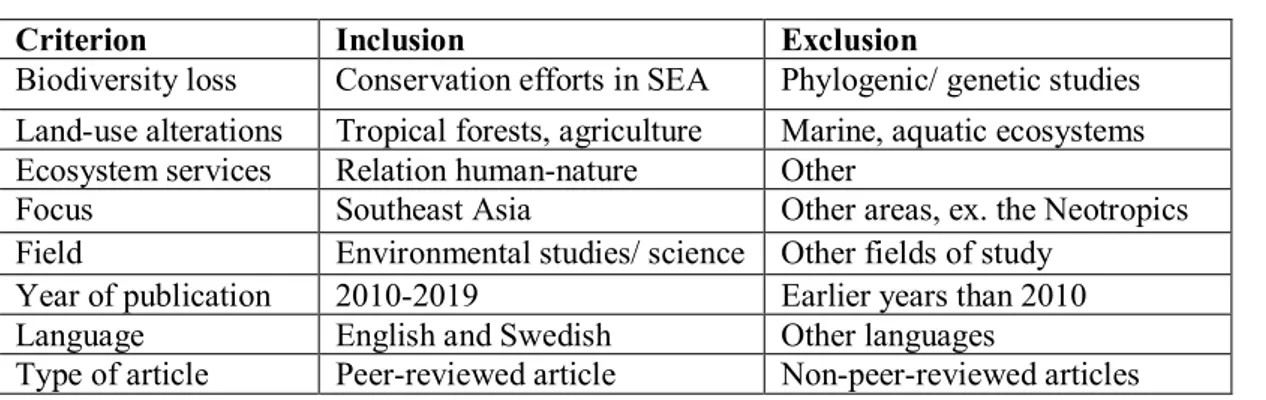

To find articles to suit the research endeavor, an inclusion as well as an exclusion criteria’s had to be created. The exclusion criteria is based on the research quest and therefore, articles had to

14 meet the criterion of either conservation efforts in Southeast Asia, terrestrial land-use alterations and ecosystem services. The year range 2010-2019 was chosen to examine what the current biodiversity research is focusing on, which is the main quest and the research purpose in this thesis. The languages and the exclusion of studies such as molecular science, phylogenetics etc. were excluded since that is out of my area of study.

Table 1: Inclusion & exclusion criteria for articles

Criterion Inclusion Exclusion

Biodiversity loss Conservation efforts in SEA Phylogenic/ genetic studies

Land-use alterations Tropical forests, agriculture Marine, aquatic ecosystems

Ecosystem services Relation human-nature Other

Focus Southeast Asia Other areas, ex. the Neotropics

Field Environmental studies/ science Other fields of study

Year of publication 2010-2019 Earlier years than 2010

Language English and Swedish Other languages

Type of article Peer-reviewed article Non-peer-reviewed articles

Because of the set criteria (see Table 1), 30 articles out of the in total 53 were to be excluded from the literature analysis. Using the set criteria, 53 articles out of totally 1074 fitted the eligibility set of this research endeavor. Six (6) articles were not available, despite being requested through different databases. The included articles (23 in total) were later divided into the categories; ecosystem services (n=5), land-use alterations (n=8), biodiversity loss (n=10) to further examine the articles.

15

4.1 Overview of the literature review

Here, a brief overview of the scientific literature reviewed will be presented

The analysis start with a descriptive analysis of the material, including what countries that the articles were conducted in, what years they were published and in what journals they were published.

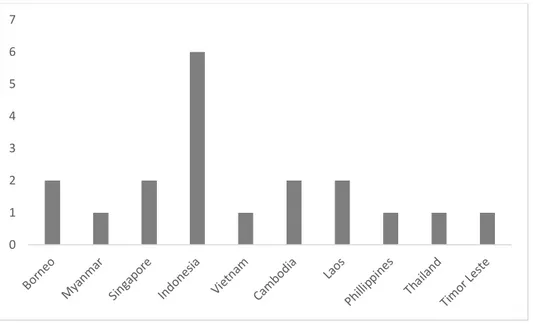

Figure 2: Areas included in the reviewed articles, some includes multiply countries:

Myanmar n= 1, Singapore n= 2, Indonesia n= 6, Vietnam n= 1, Cambodia n= 2, Laos n= 2, Philippines n= 1, Thailand n= 1, Borneo (island belonging to Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia) n= 2, Timor Leste n= 1

The articles were conducted in multiply countries in Southeast Asia (see figure 2). Some articles focused on multiply countries at once. Articles that included other areas of Asia or other tropical areas were excluded from this thesis.

The articles were published in the following academic journals; Biodiversity and Conservation (“Biodivers Conserv”) (n=3), Biological Conservation (n=3), Ecosystem Services (n=3), Global Environmental Change (n=3), Conservation and Society (n=2). The rest of the articles were published one each in Conservation Letters (n=1), Ecology and Society (n=1), Forest Policy and Economics (n=1), Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment (n=1), Global Change Biology (n=1), Human Ecology (n=1), Sustainability (n=1), Nature Climate Change (n=1) and in WIREs Climate Change (n=1). The scientific articles in this analysis lives up to the

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

16 requirements for a systematic literature analysis as described by Eriksson Barajas, Forsberg & Wengström (2013). They emphasize that scientific articles, in addition to being original work must be accessible, reliable and have desirable form and structure.

4.2 Validity of results

Here, the validity of the scientific material reviewed is discussed briefly

Some authors were found in multiply of the articles in this review, such as Fisher and Miettinnen. Further, this may be a biased literature review since many authors and co-authors of the articles can work together, as biodiversity conservation in Southeast Asia is a quite narrow (and underfunded) area of study. The authors may influence each other’s work, which may have both positive and negative aspects. There is also an existing bias towards publishing articles that are “relevant” as to the area of study, so other as well as local perspectives are lost. This results in that the literature review might be less exhaustive than it could have been.

17

5. Literature review

The results of the literature reviewed will be presented and analyzed through an environmental ethical lens.

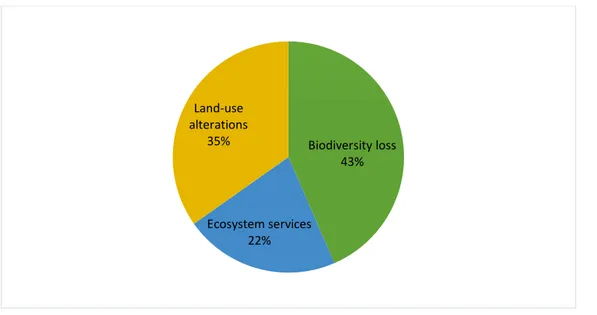

The 23 articles were divided into the categories “biodiversity loss”, “land-use alterations” and “ecosystem services” and are presented below. These themes were used to identify and include articles and further, to exclude articles of other themes in the method section. After a brief presentation of the articles in each category, an analysis will follow and afterwards, a discussion section.

Figure 2: Themes of articles in review (biodiversity loss n=10/43%, land-use alterations n=8/35%, ecosystem services n=5/ 22%

5.1 Review of biodiversity- loss articles

Short synthesis

Totally nine articles (n=9); Brun et al (2015), Dressler, To & Mahanty (2013), Fisher et al (2011a), Fisher et al (2011b), Giam, Clements, Aziz, Chong & Miettinen (2011), Hughes et al (2017b), Koh & Sodhi (2010), Morita & Matsumoto (2018), Sidik, Supriyanto, Krisnawati & Muttaqin (2018), fell into the category ”biodiversity loss”. These articles addresses various themes and issues of biodiversity loss conservation in the area. Koh & Sodhi’s (2010) article

Biodiversity loss 43% Ecosystem services 22% Land-use alterations 35%

18 focuses on the biodiversity loss and the drivers of it in Southeast Asia and they state that the main driver is the habitat alterations, as discussed before. Two (Brun et al, 2015 & Hughes et al, 2017b) articles focuses on the shortcomings of protected areas (PA’s) and biodiversity hotspots. Further, two (Koh & Sodhi, 2010 & Morita & Matsumoto 2018) articles calls for the need of a better international multi-faced strategies to stop the deforestation and biodiversity loss in the area. The article from Sidik et al (2018) focuses on the biodiversity loss caused by loss of mangrove forest habitats. Further, two of the articles (Giam et al, 2011 & Fisher et al, 2011a) focuses on biodiversity conservation by the regeneration of logged forests and to protect second growth forests. The second article from Fisher et al (2011b) aims to address the issue of the costs and benefits of plantations versus protecting forest biodiversity and ecosystem services. Lastly, the article from Dressler et al (2013) focuses on socio-economic issues that the locals within a national park area are facing because of top-down environmental regulations.

Analysis

The rapid loss of biodiversity and the possibility that the area could lose up to 42% of local species is discussed by Koh & Sodhi (2010) which is also the overall quest to explore in this thesis. The conservation policies effects in reality and how top-down regulations can be improved to suit the needs of local peoples and local biodiversity is being addressed in Dressler et al’s (2013) article. Dressler et al (2013) studied the conservation efforts in a national park in Vietnam. There, the conservation policy increased land value, made elites become landlords, widened the gap of rich and poor villagers, the increased market value that comes with the policies contributes therefore to over-exploitation of forests within national park (Dressler et al, 2013). This is contesting the general view of what effects environmental protection has on local communities. As among others, Sodhi et al (2010b) states, it is urgently needed to address the social issues to understand what environmental protection that will suit specific areas social challenges.

Two articles are focused on if conserving biodiverse areas will be profitable in comparison to plantations and/ or logging and how the ecosystem services provided by conserving the areas instead of converting them into plantations or timber will be profitable (Fisher et al, 2011b & Sidik et al, 2018). Fisher does not state that this is a desirable outcome, but rather that there is

19 a great need for revising the ecosystem- service payment mechanisms. For example, indirect ecosystem services might be impossible to make reliable valuations of and are often excluded or overlooked in this sense. So, inevitably, the monetary benefits of converting forests in the short term to plantations exceeds the benefits of conserving them. Brun et al (2015) & Hughes et al (2017b) are arguing that protected areas (PA’s) are insufficient and biodiversity hotspots are poorly protected, the biodiversity hotspot concept are argued too large areas to be protected in i.e. PA’s, especially since almost all Southeast Asia are considered threatened areas. Hughes et al (2017b) states that >75% of species remain unprotected because biodiversity hotspots fall outside of protected areas. The range of the taxa of interest of protection (such as endangered, vulnerable species etc.) in biodiversity hotspots are as well, argued to be overestimated by IUCN and this further reduces the actual conservation efforts being made. The PA’s could potentially be wrongfully placed in order to protect specific endangered species. It is not feasible to use the biodiversity hotspot concept in biodiversity conservation in these situations since the biodiversity hotspots covers too large areas. Brun et al (2015) study from Indonesia also stresses that the construction of roads within PA’s further risks intensified illegal logging.

That Southeast Asia could lose up to 42% of local (species) populations because of deforestation in the next century would mean that at least 50% of these species would go extinct globally since they are endemics (Koh & Sodhi, 2010). The focus of two the articles is that international conservation efforts; aid and regulations are not sufficient or poorly developed for meeting the needs of the area. Morita & Matsumoto (2018) and Koh & Sodhi (2010) urges the need to develop interdisciplinary strategies and programs to join together to address the many issues caused of deforestation and habitat alterations. Forest conservation has many positive outcomes; climate change mitigation, adaption, and biodiversity/ecosystem conservation. Morita & Matsumoto’s study was conducted in Thailand, Indonesia, Laos and Cambodia in 2018 (Morita & Matsumoto, 2018). There is a need for an interdisciplinary and multi-faceted strategy requiring all stakeholders to work together to achieve the ultimate goal of reconciling biodiversity conservation and human well-being in the region (Koh & Sodhi, 2010). Then, habitat conservation efforts, specifically mangrove forests in Indonesia are being evaluated. Benefits from conserving mangrove forests are; carbon benefits (mangroves serves as carbon sinks), this will enhance the value of mangrove forests in terms of ecological, social, and

20 economical benefits (Sidik et al, 2018). This could improve the valuation of these exploited, yet very biologically important ecosystems in terms of serving as nurseries for many species.

Fisher et al (2011a) and Giam et al (2011) addresses the need of regenerating logged forests, this is a crucial step towards protecting habitats that has once been cut down. It is also a new angle to the conservation efforts that we have seen in the northern hemisphere. One way to preserve habitats specific for Southeast Asia is to protect not only primary forests but also promote protection for selectively logged forests. Selectively logged forests represents cost-effective ways to enlarge protected areas, improve connectivity between them and to create new and large protected areas (PA’s) in Borneo (Fisher et al, 2011a). They also point to that there is limited relevance of protecting primary forests (in the Sundaland region, one of the four over-lapping hotspots in Southeast Asia), since selective logged forests serves as important habitats for endangered species. They suggests that selectively logged forests should be assessed for their ecological value and be prioritized for better protection (Giam et al, 2011).

Several of the articles point at revising different systems to improve biodiversity conservation is needed urgently. The four biodiversity hotspots that covers almost whole Southeast Asia (Indo-Burma, the Philippines, Sundaland, Wallacea; Myers et al, 2000) has already lost over 90% of their original habitat, this is arguable the most critical area for conservation efforts in the world (Myers et al, 2000). This could be addressed by reviewing the biodiversity hotspots and the actual range of species in urgent need of protection, and implementing more biocentric perspectives (Bórras, 2016) into biodiversity protection.

Ways to move forward in the scientific community are to work together internationally to form resilient communities (see Folke, 2006). To focus on resilience in the near- future is essential to cope with changes in the environment, especially since the area mainly consists of developing countries. To move towards social and ecological resilience and biocentrism and away from top-down regulations, policies and “hard” ecosystem service values could improve the social and environmental problems in the area, which are deeply connected (Chaigneau et al, 2018). The resilience perspective (see Folke, 2006) could be a perspective to use in biodiversity conservation efforts in the area. Bórras (2016) argues that legal systems historically have been

21 developed to defend environmental destruction and that there is a need to re-define policies concerning the rights of nature.

It can be argued that the use of ecosystem services to protect biodiversity is the opposite of the biocentric ethics. This is not necessarily the case, since the ecosystem services are simply an economic tool to point out why the ecological processes are essential for a range of purposes and to estimate the economic value of these. On the other hand, the cultural ecosystem services are problematic as they are often overlooked because of the lack of direct monetary values. In this part of the world, as well as in the neo-tropics, these types of biocentric worldviews are already a part of the culture it can be argued (see Gudynas et al, 2017) and therefore by using ethics to promote the biodiversity conservation efforts as well as to understand the cultural and environmental links of the area could be one solution to further promote conservation.

5.2 Review of land-use alteration articles

Short synthesis

In total, eight articles (n=8); Ahrends et al (2015), Fox (2014), Islam, Pei & Mangharam (2016), Mang & Brodie (2015), Marlier et al (2012), Miettinen, Shi & Liew (2011), Sodhi et al (2010a), Webb et al (2013), fell into the category of land-use alterations and altogether, they represent various problems that are directly connected to land-use alterations. Two of the articles Ahrends et al (2015) and Fox (2014) focuses on the land conversion to rubber plantations, another article (Mang et al, 2015) addresses non-oil tree plantations and the effect they have on biodiversity. The article from Miettinen et al (2011) shows the deforestation rates in Southeast Asia the period 2000-2010. Webb’s (2013) article focuses on the deforestation and the future projections of Myanmar mangrove biodiversity. Sodhi et al’s (2010a) article focuses on human-modified landscapes effects on biodiversity. Lastly, the articles from Marlier et al (2012) & Islam et al (2016) studies the socio-economic losses of the slash-and-burn agriculture systems and the implications of the El Niño fires on Southeast Asian biodiversity.

22 Analysis

The deforestation rates over the last decade in Southeast Asia states that especially peatland forest systems are in rapid decline and there is great need for taking action against the deforestation because of its carbon storage properties, one regulating ecosystem service connected to peatland forests (Miettinen et al, 2011). Other important ecosystems declining are the mangrove forest systems, Webb et al’s (2013) articles studies the Myanmar mangroves and concludes that there is a threat of near future agricultural expansion and industrial investments coupled with low governance effectiveness, this ultimately puts great pressure to safeguard biodiversity in Myanmar (Webb et al, 2013).

Other than the more well- known problem of oil palm plantations expanding over the area, Ahrends et al (2015) & Fox (2014) articles covers, namely, the land conversion from forests to rubber plantations. Rubber plantations in PA’s compromises livelihoods, causes erosion, and alter landscape functions (Ahrends et al, 2015). Rubber plantations also causes losses of natural and agricultural biodiversity, greater use of surface and groundwater suppliers, pesticide use, some farmers loose land to industrial plantations etc. Policies need to recognize and limit damaging effects of rubber plantations (Fox, 2014). Other non-oil-tree plantations are studied in one article. Rubber and cacao plantations support lower biodiversity than intact, primary forests. In Mang & Brodie’s study (2015) Acacia plantations was not statistically different from forests, although, they mention that species composition could be critically altered. Older plantations were more similar to forests than new plantations (Mang & Brodie, 2015). This perspective is needed as the rhetoric of only palm oil plantations as the main cause of land-use alterations is not the whole truth. Once again, the socio-economic factors, such as the ones that are predicted for Myanmar are needed to be analyzed to halt the land-use alterations.

As beforementioned, Miettinen et al (2011) analyzed the deforestation rates in the area the past decade, they concluded that throughout the region, peat swamp forests showed the highest deforestation rates of 2.2% / year, lowland evergreen forests 1.2 decline per/ year. In 2000- 2010 mainly Sumatra (Indonesia) and Sarawak (Malaysian Borneo), had the greatest losses by decline of 50% of peatland forests. Deforestation rates endanger species, increase elevated

23 carbon emissions from deforested peatlands and therefore contributing to the higher levels of carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere. Miettinen et al (2011) conducted the study in Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Timor- Leste. Further, human-modified landscapes and how the synergistic effects from many environmental problems together threatens biodiversity is analyzed in Sodhi et al’s article (2010a).

Long-term studies are needed to understand biotic sustainability in regenerating and degraded forests, particularly in the context of the synergistic effects of multiply agents of biodiversity loss (e.g. invasive species and climate change). The preservation of large tracts of mature forests should remain the principal conservation strategy in the tropics according to Sodhi et al (2010a). There are several articles stating that strategies developed specifically for Southeast Asia are needed, as the alterations are causing the rapid decline of biodiversity.

Other main problems of protecting the biodiversity are the wildfires and the slash-and burn agriculture specific to the area, Islam et al (2016) & Marlier et al (2012) examine this problem. They propose that reducing deforestation will improve public health risks, and other ecosystem services declined by El Niño fires (Marlier et al, 2012). The haze pollution caused by the slash-and-burn agriculture causes deforestation, soil erosion, global warming, threats to biodiversity, health risks, economic and productivity losses, trans-boundary haze pollution etc. (Islam et al, 2016).

To answer the research quest, some ways to halt the land-use alterations as presented by the literature are to further analyze the transboundary and synergistic environmental problems which intensifies biodiversity loss caused by land-use alterations. This could be addressed in the best of scenarios, with reducing the land-use alterations in Southeast Asia. By putting further market signals on protecting biodiversity and the ecosystem services that they provide could be a start, since the problems are mainly caused by the global demand of crops. To halt land-use alteration, the resilience perspective (see Folke, 2006) can be helpful in developing strategies for locals to cope with the changes in their near environment as well as in developing environmental protection. The first and foremost issue that the literature is pointing at is the lack of funding and the lack of overall interest for the area’s biodiversity. To value the ecosystem services and to make calculated decisions with help of i.e. international

24 environmental programs could be a way forward to help farmers in the area. To reduce the loss of biodiversity, the resilience perspective could be a way to address this issues as poor households tend to be worst off in environmental catastrophes (Adger, 2004). To allow people dependent on their surrounding ecosystems to be heard in decision-making is also a crucial step to protect biodiversity in these areas and to move towards a biocentric nature view, it can be argued.

5.3 Review of ecosystem services articles

Short synthesis

Totally six articles (n=6); Antons et al (2010), Castonguay, Burkhard, Müller, Horgan & Settele (2016), Kibira, Behie, Constanza, Groves & Farrel (2017), Kubitza, Krishna, Alamsyah & Qaim (2018), Rasmussen et al (2015), Sumarga, Hein, Eden & Suwarno (2015), fell into the category of ecosystem services. Together they represent various themes regarding the ecosystem services research. Kibira et al’s (2017) article measures the monetary and non-monetary ecosystem services of the Veun Sai-Siem Pang National Park in Cambodia for the first time, in total the ecosystem services are worth $129.84 million annually, although many sociological problems exists such as corruption and poaching. The national park are facing multiple threats; illegal logging, poaching, corruption and more while being one of the most important eco-regions in the world. The article from Kubitza et al (2018) shows the economic benefits that locals derive from palm oil plantations and further how this can effect conservation efforts, especially when the livelihoods improves. Then, the two articles from Rasmussen et al (2015) & Sumarga et al, (2015) shows how to combine multiple methods to see what ecosystem services that are actually being used and show how ecosystem services can be valued and mapped. Lastly, the two articles from Castonguay et al (2016) & Antons (2010) studies the ecosystem services and states that the traditional and cultural ecosystem services are being lost, one article specifically focuses on traditional knowledge of biodiversity and ecosystem services.

25 Analysis

The existing positive effects from palm oil plantations on the life quality of the local residents in response to the revenues from the production are analyzed by Kubitza et al (2018). In Kibira et al’s (2017) article, the sociological problems that the Veun Sai-Siem Pang National Park in Cambodia locals are facing such as illegal logging, poaching, corruption, even though being one of the most biodiverse areas in the area are studied. There is inevitably a difference between what is best for the environment and what the policies trying to protect the local biodiversity are actually achieving. Even though it is estimated that the ecosystem services are worth millions of dollars, this is not something that the local residents can put in their pockets, to be precise. It can be argued that there is a pressing need of class analysis when it comes to biodiversity conservation policies in developing countries. This is also touched upon in the article by Sodhi et al (2010b), that the issue of creating environmental protection needs to be connected within the sociological dynamics of the area where they are meant to be adopted to properly function.

According to biocentrism, nature has an intrinsic value (Bórras, 2016) and this is included in ecosystem services in theory, but in reality it is hard to put monetary value on simply the existence of species. It can be argued that we need a shift away from the way of thinking of the well-being of only humans, but also the well-being of other species.

Rasmussen et al (2015) & Sumarga et al (2015) are providing new ways of measuring ecosystem services. Rasmussen et al (2015) states that it is the first study in Southeast Asia to combine multiple methods to see what ecosystem services are used and how and how they differ from ecosystem services availability (Rasmussen et al, 2015). In the study by Sumarga et al (2015) they show how ecosystem services can be valued and mapped, how they also can support land use planning from value trade-offs from land conversion in Indonesia (Sumarga et al, 2015). The article of Kubitza et al (2018) shows positive effects of palm oil plantations in Indonesia on farmers’ livelihoods, economically as well as that the oil palm plantations needs lower labor than other crops. Further, oil palm regulation policies will have to account for the economic benefits of locals (Kubitza et al, 2018).

26 The articles from Antons (2010) and Castonguay et al (2016) concerns the problem of safeguarding biodiversity knowledge, traditional knowledge and other cultural ecosystem services. International collaboration is important to avoid disputes concerning biodiversity related knowledge held across borders (Antons, 2010) disputes of traditional and cultural knowledge between Malaysia and Indonesia are mentioned. In rice ecosystem services there are changes in the social-ecological state of communities. Cultural ecosystem services have been lost as the ways of producing rice has intensified (Castonguay et al, 2016). Once again, the social factors that resilience builds upon can be argued, strengthens from cultural ecosystem services and are therefore vital to protect.

As Daw et al (2016) states that ecosystem service frameworks are highly focused on ”hard values”, rather than ”soft” ones, regarding the well-being aspect. As the articles reviewed suggests, the life quality derived from the converting forests to plantations are showing that local residents are experiencing higher life quality than before the plantation or other negative effects from environmental policies. The well-being derived from the oil palm plantations to the locals are showing the opposite of the general idea that conserving ecosystem services are more valuable to local’s than the opportunity to access better life quality than before.

Biodiversity loss and poverty issues are linked and frequently coincide at various scales (Chaigneau et al, 2018), through the literature reviewed (see Kubitza et al, 2018) they are focusing on another aspect, namely of moving from poverty through planting oil palm and thereby acquiring the means of a better life quality. Kubitza et al (2018) suggests that regulations needs to take the social aspect into account. Kibira et al (2017) study to measure the ecosystem services worth in the Cambodian national park is interesting to analyze because even though the area faces many social problems and this could be tackled by i.e. examine the weaknesses of our environmental laws, which according to Bórras (2016) are not biocentric and stem from the fact that legal systems treat the natural world as property that can be exploited and degraded. The social problems of a developing nation such as Cambodia in this case, needs to be examined to understand what kind of environmental protective laws that can be imposed on the local population and thereby work the way intended.

27 The analyzed articles in all of the categories points at that there is a need for focusing on the socioeconomic aspects in Southeast Asia to develop environmental protection and to understand the drivers of the rapid biodiversity loss (see Sodhi et al, 2010). It can be argued that we need to change the way we think of the nature, from anthropocentric to biocentric in order to be able to protect biodiversity.

6. Discussion

The discussion aims to answer the thesis questions; to research the biodiversity loss in Southeast Asia through recent scientific literature, analyze problems of biodiversity conservation and ways of promoting biodiversity conservation in Southeast Asia.

Figure 3: Venn-diagram over the three interconnected themes

Summarized, the main problems regarding the objectives of this literature review, are the rate of biodiversity lost in Southeast Asia and as Sodhi et al (2010a) and Koh & Sodhi (2010) points out that the rate of biodiversity loss is very high in the area (and is projected to increase by 13-87%) as well as the loss of peatland forests in Indonesia and in Malaysian Borneo (Miettinnen et al, 2011). The main issue is regarded as the lack of funding of biodiversity conservation, which ultimately leads to the lack of access of data and scientific material in the area. Further are the socioeconomic problems that the locals are facing through top-down environmental policies a great issue to address. To halt the land-use alterations and at the same time provide locals with the means necessary to sustain their lives, it is necessary to create better market price mechanisms, such as creating better ecosystem service payment mechanisms as suggested by Fisher et al (2011b) as they are not matching the returns of the activities that causes habitat

biodiversity loss ecosystem services land-use alterations

28 destruction. Efforts should be directed to protect biodiversity, ecosystem services mainly in stopping habitat destruction caused by agricultural expansion, plantations and urban areas. Lastly, if there is an underlying purpose behind ecosystem service policies promoting traditional knowledge and biodiversity knowledge and how responsible these will be in safeguarding biodiversity according to mainstream media and international policies when scientists are pleading for funding and resources to protect the biodiversity hotspots.

There is a need to provide means to help the area battle the deforestation and the loss of species and ecosystem services, and to provide incentives to help fight illegal poaching and logging activities, especially in PA’s. The demand for illegal products as well as uncertified crops who directly damages habitats and pushes species towards extinction needs to be addressed globally. It is not enough for international organizations to promote solutions such as ecologic farming, ecotourism or promoting traditional biodiversity knowledge when there are widespread criminal networks selling endangered animals and a global demand for i.e. crude palm oil and rubber. Especially, as Rockström et al (2009) defines the thresholds of environmental problems that intensifies each other, there is a need for global incentives to cooperate internationally to solve this pressing issue. The loss of biodiversity will lead to the loss of life-upholding processes on Earth, not only in Southeast Asia, even though it is clear that developing countries and citizens whom directly depend on ecosystem services, such as farmers are worst affected by climate-related issues and loss of ecosystem functions.

29

Picture 3: Monument text cited: “The first 4 oil palm seedlings (Elaeis guineesis Jacq.) to be introduced from West Africa were planted here in 1848. In 1911, commercial cultivation of their descendants began in North Sumatera. The subsequent development of extensive plantations has placed Indonesia as the number one producer of palm oil in the world.” Botanical Gardens, Bogor, West Java, Indonesia, 2018, Louise Nilsson.

Widely, it can be argued that the capitalistic system and imperialism are the underlying causes of the deforestation in Southeast Asia (the demand of cheap products made from palm oil, rubber, timber etc.). The realization that the global demand for these products is the main driver of the land-use alterations needs to be clearer. There is a long history of imperialism in Southeast Asia and to see the connections of i.e. the oil palm being introduced in for example Indonesia by the British (personal communication, Soetomo, 3 October, 2018) and the global demand created to fill the demands of the western world’s need for palm oil products. Because of the area’s history of imperialism it can be one further argument that this is a global problem that needs to addressed accordingly.

Discussed in the reviewed articles regarding ecosystem services are mainly themed around the safeguarding of biodiversity knowledge (Antons, 2010 & Castonguay et al, 2016) and new and improved ways of measuring ecosystem services (Rasmussen et al, 2015 & Sumarga et al, 2015). It is interesting to critique the different uses of the term ecosystem services. The cultural ecosystem services in particular and what the traditional ecosystem services means in protecting the biodiversity in Southeast Asia. It is interesting to discuss the possible economic incentives

30 for these types of ecosystem services to be protected, i.e. to safeguard information about medicinal plants. It can be argued that this type of ecosystem services seldom serves as any real protection, i.e. safeguarding of holy forests and other spiritual or traditional uses of land. Underlying purposes could come from market interest. This could be a solution but also a further threat to safeguarding ecosystem services as seen in a biocentric perspective (Bórras, 2016), as intrinsic values are excluded from market values. These ecosystem services could be used to find new ways of producing medicine etc. through harvesting plants or using medical substances found in i.e. amphibians or other at risk species. One risk is that this will cause further problems in protecting biodiversity.

There is a strong relationship between human well-being and healthy ecosystems, ecosystem services are proven to be even more vital for developing countries as many people depend on them to an higher extent than in developed countries (Daw et al, 2016). The cultural ecosystem services such as i.e. holy forests can be a matter of income for local peoples as they draw ecotourism, which are also considered ecosystem goods (Hooper et al, 2004). In this matter, these types of ecosystem services are of high value, not only the provisioning ecosystem services are valuable for local people if they can create an income from tourism etc. The general rhetoric is also being challenged in multiply of the articles reviewed, since in environmental policies the local perspectives are often forgotten.

Another problem, is that developing nations differs enormously from developed. In the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) the article 3 states that;

States have, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations and the principles of international law, the sovereign right to exploit their own resources pursuant to their environmental policies, and the responsibility to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction and control do not cause damage to the environment of other states […] “or of other areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction (Antons, 2010, p. 1191).

The sovereign rights of a nation to exploit their natural resources coupled with the blurry picture given of the local and indigenous communities embodying the traditional ways of life that are

31 often explained as a way forward for environmental protection is problematic. Developing nations cannot chose to protect their nature the same way developed nations can. In Sodhi’s et al (2010) article the protection of the region’s remaining forests and biodiversity will require the integration of social issues such as rural employment into conservation planning efforts. This is one way to both safeguard the protection whilst providing incentives for local’s to do so, instead of making a livelihood out of plantations, poaching or other illegal activities which damages their local ecosystems.

A new report from IPBES (the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services) compiling the work of 15, 000 scientific publications from all over the world stating that 1 million species are on the brink of extinction, was recently published. Still the rhetoric in media and scientific publications seem to reduce the giant effort which is immediately needed if we want to halt the extinction rates with answers such as “we need a drastic change” and ”we need to support indigenous groups with biodiversity knowledge”. This rhetoric is still remaining after this catastrophic report, and it is carrying the same message as this thesis, namely that the biodiversity loss is the main environmental problem to focus on. This problem although remains partly hidden in mainstream media coverage as well as by publication bias and research in favor of i.e. climate change mitigation or plastic waste problems. The IPBES report is the first global assessment ever to systematically include and examine local and indigenous knowledge, issues and priorities. Among a lot of information already discussed in this thesis, the report states that agriculture expanded by 100 million hectares just in the tropics the period 1980-2000 were altered, mainly by cattle ranching in South America and by 7.5 million hectares of which 80% is oil palm were altered in Southeast Asia, by at least half at the expense of intact forests (UN, 2019).

The question is if it is ethical to put the burden of safeguarding our common environment and ecosystem services on marginalized groups, which most of the rhetoric seem to point at. Is it not the global demand for endangered animals and the lack of interest to protect biodiversity, and the demand for more agricultural and urban expansion that has led us to where we are at today. To quote another angry environmentalist: Myers et al (2000, p. 858) argues: