“N

OT A BRAND BUT A VOICE

”

The Advertising and Activism of Oatly in Germany

2nd year Master’s Thesis

Submitted by: Luisa E. Falkenstein

Malmö University

K3 – School of Arts and Communication

Media and Communication Studies: Culture, Collaborative Media and

the Creative Industries (Master of Arts)

Supervisor: Temi Odumosu

Examiner: Michael Krona

A

BSTRACTWhen describing the company’s ethos and brand, the creative director of Swedish oat drink pro-ducer Oatly, John Schoolcraft, routinely declares the company’s intention to be not a brand, but a voice. As popular activist causes become utilized by companies and commodified for advertising use, identifying the ways in which communication is used to create meaning becomes a relevant skill. This thesis takes Schoolcraft’s statement as a basis of inquiry into the ways in which a company can present itself through language. Through a multimodal discourse analysis of three different semiotic materials produced by Oatly in Germany; the text of a 2019 petition, two 2019 advertising posters and a selection of product packaging collected during the summer of 2020, the thesis seeks to identify the relevant discourses evoked by Oatly, the ways in which Oatly is represented within those discourses and the way in which Oatly’s semiotic resources might serve to create a myth of Oatly, the voice, not the brand.

The relevant discourses represented in the texts were sustainability, food consumption and pro-duction, government power and the empowerment of consumers. In these discourses Oatly positioned themselves (as well as the reader) as an agent of change, trying to affect progress. The discourses were often found to be connected to Oatly as a brand, but somewhat removed from Oatly’s products. A potential myth of Oatly as a leader in a political effort, might be substantiated within a small sphere of influence amongst consumers.

As the research design relies largely on the author’s own interpretations of the material, none of the inferences from the analysis may be considered absolute or objectively true.

Keywords: Advertising, Commodity Activism, Social Semiotics, Multimodal Discourse Analysis,

Oatly.

Word Count: 12.900 Grade Received: C

A

CKNOWLEDGEMENTSWriting this thesis has been a struggle. Between the self-inflicted stress of wanting to deliver a worthy final piece of writing for my degree and the troubles and turbulations of a global pandemic, I honestly did not think I would succeed in finishing it.

I am grateful to my thesis supervisor, Temi Odumoso, for her kind and patient support during the early stages of developing this thesis.

None of this would have been possible without the loving support of my family, especially my parents, who are the greatest. Also the greatest is my little sister Sarah, who always encouraged me and who made this thesis possible by venturing out into Berlin’s supermarkets during the height of Covid restrictions to procure Oatly packaging materials for my research.

I am also immensely grateful to all of my friends for their support, especially... ...Felicia, for giving me a reason to occasionally leave the house and socialize. ...Julia, for not letting me quit.

...Hanna and Jasmin, for enduring my occasional whining and being so understanding of my slack-ing on household chores.

T

ABLE OFC

ONTENTS1. INTRODUCTION... 1

2. BACKGROUND:THE STORY OF OATLY... 3

2.1. Humble Swedish Beginnings ... 3

2.2. “A Voice not a Brand” ... 4

2.3. The aftermath of the 2019 Petition ... 6

3. THEORETICAL CONCEPTS ... 6 3.1. Discourse ... 6 3.2. Social Semiotics ... 7 3.3. Myths ... 8 4. PREVIOUS RESEARCH ... 9 4.1. Strategies of Activism ... 10 4.2. Discourses of Advertising ... 11

4.3. Marketing and Commodification of Social Issues ... 12

4.4. The Case of Oatly ... 13

5. REVISITING MY RESEARCH QUESTION ... 14

6. RESEARCH DESIGN ... 15

6.1. Multimodal Discourse Analysis ... 16

6.2. Sampling and Material ... 17

6.3. Realization of Research Design ... 18

6.4. Ethical Considerations ... 18

6.5. Limitations... 19

7. RESULTS &DISCUSSION... 19

7.1. Oatly’s German Product Packaging ... 19

7.2. The Petition Posters ... 24

7.3. The Petition Text ... 26

7.4. Oatly as a Voice – Oatly as a Brand ... 27

8. CONCLUSION &OUTLOOK ... 29

9. REFERENCES ... 31

T

ABLE OFF

IGURESFigure 1 Petition poster photographed at Torstraße, Berlin ... 1

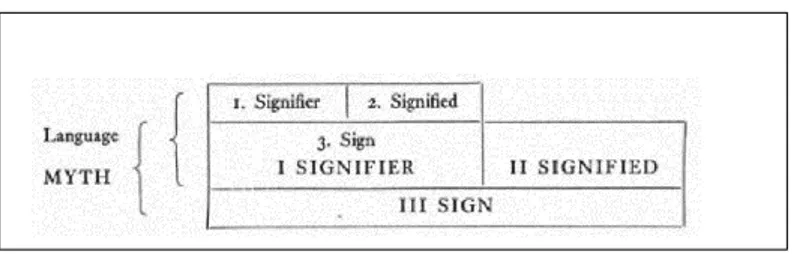

Figure 2 The concept of the myth according to Barthes (1972, p. 113) ... 9

Figure 3 Packaging Detail: Logo ... 20

Figure 4 Front of Packaging: Hafer Cusisine Bio and Hafer Bio ... 21

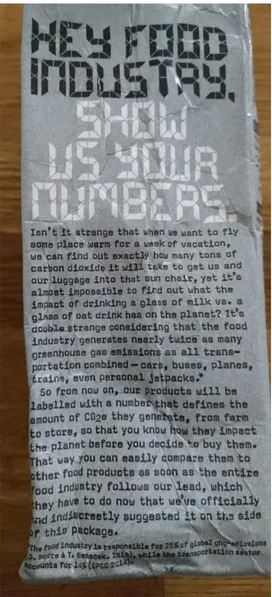

Figure 5 Packaging Side: Hey Food Industry! ... 21

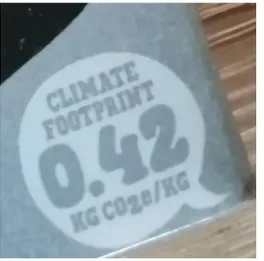

Figure 6 Packaging detail: CO2 footprint ... 22

Figure 7 Packaging Inside: The Oat Horoscope ... 22

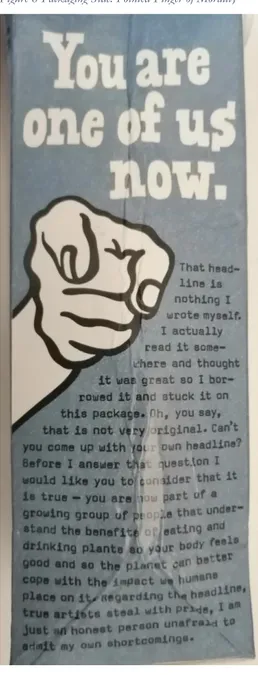

Figure 8 Packaging Side: Pointed Finger of Morality ... 23

1

1. I

NTRODUCTIONA current trend in advertising is corporations weighing in on current political struggles. Pride pa-rades, once a celebration of marginalized communities sticking it to the man, are now sponsored by the man, with anyone from tech giants to fast food franchises trying to prove their inclusivity, during Pride month. Colin Kaepernick, blacklisted from the NFL for kneeling during the national anthem to peacefully protest police brutality towards the Black community in the US, has become the face of a Nike campaign. Sustainability, fairness, inclusivity, and empowerment have become buzzwords for corporations trying to show to young and politically interested consumers that they can support a great cause, by consuming their products (Castañeda, 2012).

In the fall of 2019 Swedish oat drink producer Oatly erected several posters in various locations across Berlin, Germany. What made these posters somewhat peculiar, was the fact that they did not seem to advertise a product and aside from Oatly’s logo in the bottom right corner made no reference to the company or its range of oat-based products. Instead, observers were prompted to “Sign the petition” (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Petition poster photographed at Torstraße, Berlin

Note: This image was retrieved from Herrmann (2019), where the image is accredited to Oatly.

The petition in question, number 99915, was filed on October 1st, 2019, through the official online forum of the German Bundestag (federal parliament). The petitioners demanded that in order to give consumers a better understanding of how their purchases affect the environment and thus enable them to make more informed sustainable decisions, the government should propose

2

legislation making the declaration of a product’s CO2e-footprint1 mandatory on all packaging for

foodstuffs (Petition 99915: CO2e-Kennzeichnung auf Lebensmitteln, 2019). On November 12th, 2019, the petition deadline, the petition had garnered the support of 57,067 signees, surpassing the threshold of 50,000 signatures needed to pass the petition on to the relevant committee of the Bundestag (Deutscher Bundestag, n.d.). The case sparked some media attention at the time, and may have helped Oatly establish itself as a brand on the German market (Sarholz, 2019; Werner, 2020).

For my final piece of writing for this degree, I have chosen to take a closer look at Oatly’s com-munication in Germany. This is a topic informed by my personal interest: I have been a happy consumer of Oatly’s products and a follower of their marketing both on- and offline for nearly two years. In addition, the key interest drawing me to pursue a degree in communication studies in the first place is my fascination with the ability of skilled creatives, marketers and designers to create a narrative around their product – to tell me a story and draw me in, to persuade me to give their product a chance.

I chose to look at this particular case by analysing three different media texts: Firstly, the original petition text, which is still available online; secondly, two different types of billboards advertising the petition, of which I found photos online, and thirdly, a small selection of packaging of different Oatly products, available in German supermarkets. These materials were analysed both individually and in context with each other. I was interested in exploring how these texts would promote Oatly as “voice, rather than a brand” as John Schoolcraft, Chief Creative Officer of Oatly and head of the “Oatly Department of Mind Control” so aptly described the company’s identity (Slush, 2018). My exploration focussed around one primary research question:

How does Oatly communicate as a voice rather than a brand in Germany?

Despite being largely inspired by my private interests, I nevertheless believe that there is some wider societal relevance to my research: Living in a world where consumption is constantly encour-aged and has become, according to some scholars, an aspect of our very identity (Hearn, 2012; Kettemann, 2014), making ethical decisions, which don’t cause harm to the world, or even better, which benefit the world, has become increasingly difficult. For one, because in our globalized world, driven by profit and a capitalist and neo-liberal ideology, understanding all the effects of one’s actions is nearly impossible. But also, because we are increasingly told how to be good by companies, who align themselves with causes seen as progressive or fair in order to further their

1 The term CO2e stands for Carbon dioxide and equivalent gasses, essentially encompassing all so-called greenhouse-gasses.

3

own goals of increasing profits (Hearn, 2012). In order to not become complicit in the commodi-fication of important social causes, consumers (and academics) need to understand how companies might use various modes of communication to create an image as a force for good, an advocate and political ally, in order to obtain the public’s support (and money). Therefore, despite my initially positive personal connection to my subject matter, my hope with this thesis is to develop my own critical voice and showcase the necessity of remaining critical of the way companies and those who hold power (e. g. political or financial) may try to persuade the public of their benefaction, regard-less of whether or not they are affecting positive change in the world (which I am in no position to judge in this particular case).

Over the course of this thesis, I will first introduce Oatly, summarizing the company’s history and self-proclaimed identity as a “voice” (Chapter 2). Following this I will elaborate on the theoretical concepts which I have employed as part of my research: discourse, social semiotics and myths (Chapter 3). These concepts will serve as the lenses through which I conduct my analysis, while the findings and ideas presented as part of my literature review, in the subsequent chapter (Chapter 4), will help me classify my findings in a media and communication studies context. I will focus on research regarding activism and advertising communication as well as previous research on Oatly. My research question will be revisited and revised in light of the previous chapters (Chapter 5) before I will discuss my research design and chosen method of multimodal discourse analysis with its implications and limitations (Chapter 6). The final two chapters will serve to present and discuss the results of my analysis (Chapter 7) and deliver concluding remarks and provide an outlook on future developments of my research aim (Chapter 8).

2. B

ACKGROUND:

T

HES

TORY OFO

ATLYTo contextualize my thesis, I will first give a more detailed background on who Oatly are as a company. As this chapter serves as more of a narrative framing of my research, my sources are non-academic, including newspaper articles, podcast episodes, and interviews with Oatly spokes-people. Most of my sources are persons directly affiliated with Oatly, thus making their information perhaps not unbiased, but nonetheless providing a good understanding of how the company pre-sents itself to the outside world.

2.1. HUMBLE SWEDISH BEGINNINGS

In the late 1980’s food scientists at the university of Lund in Southern Sweden were researching lactose intolerance and ways of producing milk-like substances for those afflicted with lactose in-tolerance. By 1994 one of the scientists, Rickard Öste, had discovered and patented a way to process oats into a nutritious substance, that could be used as an alternative to milk. Together with his brother Björn, an IT entrepreneur, Öste founded CEBA Foods AB, which initially produced

4

“oatmilk” as an ingredient for the food industry. In 2001 the company launched the brand Oatly, beginning instead to market their product as a consumer good (Von der Pahlen & Rautio, 2020). Upon opening their new production facility in Landskrona in 2006, the company name was offi-cially changed to Oatly AB (Landskrona Direct, 2006).

Oatly’s products were initially marketed specifically towards customers who could not consume dairy due to health reasons as well as vegans, and were available in Sweden and later in the United Kingdom (Von der Pahlen & Rautio, 2020). A big shift in the corporate structure and the brand identity came in 2012, when Toni Petersson was hired as the new CEO of Oatly. Under Petersson the company transformed its image from a food science novelty into a popular lifestyle product and a challenger brand (Alagiah, 2018).

A contributing factor to Oatly’s rise to fame was a 2014 lawsuit by the Swedish milk industry, who took issue with some of Oatly’s advertising slogans, such as: “it’s like milk but made for humans”. Finding themselves in the position of the underdog – a relatively small company versus a huge state subsidized industrial complex, Oatly published the entire lawsuit on their company website and published details of the case in full-page newspaper ads, thus garnering public support and ap-proval. Oatly has since launched its products in other countries such as Germany and the United States of America (Slush, 2018; Von der Pahlen & Rautio, 2020).

Whilst the original founder’s are still connected to the company as member’s of the board and retain partial ownership, they are no longer involved in Oatly’s daily business dealings (Von der Pahlen & Rautio, 2020). Over time, the company has attracted numerous investors and is now partially owned by groups such as Verlinvest (a Belgian investment group), China Resources (a state-owned Chinese conglomerate) and Blackstone Growth (part of American investment firm Blackstone Group), the latter of which caused some stir recently, as many consumers felt that Oatly’s ideals of sustainability were incompatible with Blackstone’s business dealings, which include projects criticised for causing deforestation and environmental pollution (Werner, 2020). With sales exceeding 200 Million USD per year (Slush, 2018), Oatly has grown significantly since its humble beginnings as a small Swedish enterprise.

2.2. “AVOICE NOT A BRAND”

What first drew my attention to Oatly and made me want to investigate further, was not the com-pany’s history or its products. I was first introduced to Oatly as part of a university course titled “Introducing the Creative Industries”, during which two different student groups presented the Oatly’s unique and creative approach to branding and advertising. At the time, having only recently relocated to Sweden from Germany, where Oatly had only just become available in health food

5

stores and was relatively unknown, I was immediately intrigued by the company’s unusual style of communication.

This style, according to John Schoolcraft, Oatly’s Global Chief Creative Officer and head of the “Oatly Department of Mind Control” (Slush, 2018), is the result of the company’s aspiration of being not a brand, but a voice (Alagiah, 2018). A sentiment that is repeated frequently whenever the company is discussed: Oatly as a company, that does not want to be a company, a brand that does not want to be a brand, but something other, perhaps something better. Schoolcraft claims that Oatly is inherently driven not by sales or commercial concerns, but by the desire to make people’s lives and the world at large better and to be a good company and be seen as a force for good (Slush, 2018).

After joining the company in 2012, Schoolcraft, along with the newly assigned CEO Toni Peters-son, changed not only Oatly’s product packaging, but in fact the company’s structure and outlook on marketing and creativity. Notably, the conventional marketing department was dissolved (and the Department of Mind Control introduced) to allow for more creative control by the higher-ups without the need for a middleman. Creative decisions became CEO-level decisions (Alagiah, 2018). The idea behind Oatly’s communication strategy became to attract attention by being different, unexpected and by being “fucking fearless”, as one company directive puts it (Slush, 2018). Oatly’s re-branded packaging, which was launched in 2014, was designed to look as unconventional as possible, made to give the impression of being homemade and hand drawn in the CEO’s basement, according to Schoolcraft. Similarly, posters and video clips were produced with the objective of not looking like they were part of a campaign and made by a professional advertising agency, but instead breaking the rules of conventional marketing. It should be noted, that Oatly’s newly de-signed packaging and promotional materials were indeed dede-signed by Martin Ringqvist and his team at the Gothenburg-based agency Forsman & Bodenfors (Alagiah, 2018).

The launch of Oatly’s new look and newfound voice was met by the aforementioned lawsuit by representatives of the Swedish dairy industry, which ultimately helped the company build its image of a challenger to the established food industries (The Challenger Project, 2018). This has influ-enced the way Oatly presents itself ever since, challenging convention not just in the way their ads and packages are designed but also in their allusion to causes such as sustainability, veganism and empowering consumers to make better choices. The petition, which will be one of the texts scru-tinized in this thesis, can be seen as one indicator of Oatly as a challenger to the establishment and the status quo within the food industry in Germany.

6

2.3. THE AFTERMATH OF THE 2019PETITION

Immediate reactions to the petition were not entirely positive. Oatly’s petition and the big effort of promoting it (especially in Berlin) was deemed a great marketing success with little potential for real political change by some (Sarholz, 2019).

As the writing of this thesis has spanned a longer timeframe than originally planned, I am now in a position, where I can report on the aftermath of the petition. On September 14th, 2020, the general manager of Oatly DACH (the German-speaking market, including Germany, Austria and Switzerland), Tobias Goj, was able to present the demands of the petition in person in front of the Bundestag’s committee for petitions (Oatly, 2020), meaning that the cause will be further pursued. During the summer various other brands, such as Fritz-Kola and Frosta also joined Oatly in pro-moting the petitions success and the upcoming hearing (Werner, 2020). These companies, among others, have joined Oatly in a newly launched initiative advocating the use of CO2e-labels in the food industry (Oatly, 2020). It appears therefore that this campaign is far from over and that Oatly did not abandon the cause after achieving public attention for the initial petition.

3. T

HEORETICALC

ONCEPTSIn its own words, Oatly aspires to be seen not as a company, or a brand, but instead as a voice. The aim of this thesis is to scrutinize some of the promotional materials produced in the fall of 2019 and during the spring of 2020, as well as a political petition authored by Oatly to determine in which ways this aspiration can be detected in the company’s communication. To guide my re-search, I relied on three theoretical perspectives, which will be summarized in this chapter. In order to identify how Oatly connects itself to wider issues in society, namely the very current concepts of sustainability, ethical production and consumption, environmental protection and em-powerment of consumers/ citizens, I will seek to identify these relevant discourses as they are alluded to in their communication. To better understand how these discourses are represented in Oatly’s communications, and how they might be understood by an audience, the research will be rooted in social semiotics.

And finally, to discern how the relevant discourses and the ways in which they are presented might create a myth of Oatly, that lies beyond their identity as a brand, I will refer to Roland Barthes concept of the myth.

3.1. DISCOURSE

Discourses lend expression to the human experience. They are the ways in which “aspects of the world – the processes, relations and structures of the material world, the ‘mental world’ of thoughts

7

feelings, beliefs and so forth, and the social world” (Fairclough, 2003, p. 124) become represented in language. Language, in this case, does not simply refer to the written and spoken word, but to all modes of human communication and expression (Barthes, 1991). It is thus through analysis of discourses that researchers may understand underlying social phenomena (Fairclough, 2003). According to Fairclough (2003), discourses may be distinguished by their way of representing (the actual manifestation in language) and by their relation to other elements of social life. Kress & Van Leeuwen (2001), define discourse as “a knowledge of practices, of how things are or must be done [...] together with specific evaluations and legitimations of and purposes for these practices.”, as well as: “a knowledge which is linked to and activated in the context of specific communicative practices” (p. 114). The former might be observable through an analysis of linguistic features, such as semiotic properties.

Despite being observable through the analysis of language, discourses are not tied to the materiality of their mode of expression, but exist through the underlying principles of social order (Kress & Van Leeuwen, 2001, pp. 24–27). In other words: simply because a discourse is not evoked at a certain time, it does not mean that it does not exist or matter.

One discourse may, depending on its context, be expressed in different representations. Similarly, specific representations may be evolved from separate discourses. Therefore, discourses are rarely observed in isolation, but must be considered in relation to other discourses and to their specific context and the personal histories of its participants (Fairclough, 2003; Kress & Van Leeuwen, 2001). While discourse may be discussed as an abstract concept, Kress and van Leeuwen (2001) emphasize that actual lived experience is never abstract (p. 27).

For the purpose of this thesis, it is my understanding that Oatly might allude to specific discourses in their communication in order to portray itself a certain way (i. e. as part of an activist struggle). In order to understand how Oatly communicates it would therefore be necessary to determine the discourses with which Oatly aligns itself.

3.2. SOCIAL SEMIOTICS

If we seek to understand how humans articulate their experience through discourse, it might help to look at the way we make sense of the world and create meaning. According to Chandler (2007) meaning is not transmitted, but instead actively created through a set of codes and conventions in the communicative process. We gain understanding of the world around us through understanding signs and the codes they make up.

8

Semiotics is the study of signs; it seeks to understand how humans make meaning through the use of signs. Signs have no intrinsic meaning in and of themselves. Meaning is assigned to them, often unconsciously, based on people’s own bias, knowledge and experiences (Chandler, 2007, pp. 10–11). French linguist Ferdinand de Saussure developed his idea of semiology, laying the groundwork for one school of modern-day semiotics. Saussure described the relationship between a signifier, the psychological impression received by a person, and the signified, the concept of which the person conceives of as a result of the process of signification. A sign is therefore the whole of the signifier and the signified. More modern approaches to semiotics, based on Saussure’s model, define the signifier as a more material form of the sign (something that can be heard, seen or otherwise ob-served), rather than a psychological impression (Chandler, 2007, pp. 14–15).

Social semiotics approach meaning-making as a social process, dependent on specific social and cultural contexts. Any actions and artefacts humans employ in the process of communicating meaning are semiotic resources (van Leeuwen, 2005).

These semiotic resources “have a theoretical semiotic potential constituted by all their past uses and all their potential uses and actual semiotic potential constituted by those past uses that is known to and considered relevant by users of the resource.” (van Leeuwen, 2005, p. 4). The term semiotic resource is not constricted to just one form of communication. According to Chandler (2007) anything can be a sign, as long as it signifies something else to someone (p. 10), similarly any action may signify an articulation of a cultural or social meaning and thus carry semiotic potential (van Leeuwen, 2005, p. 4).

To understand how Oatly positions itself vis-a-vis certain discourses, social semiotics may offer insights into the ways in which meaning is signified through semiotic resources in Oatly’s commu-nications and how the meanings might be understood by the consumers Oatly is trying to reach.

3.3. MYTHS

The final concept operationalized in my research is that of the myth, a concept popularized by French semiotician Roland Barthes. Myths are the dominant ideologies of a specific time which are asserted through communication (Chandler, 2007, p. 144). According to Barthes: “since myth is a type of speech, everything can be a myth provided it is conveyed by a discourse” (p. 107). Speech and language are in this case not limited to the spoken or written word, but encompass also photography, music, cinema, reporting or publicity (Barthes, 1991, p. 118).

Mythology builds on Saussure’s understanding of the signifier and the signified. However, a myth is constructed through a semiological chain (see. Fig. 2), in which the signified of one signifier

9

serves in turn as a signifier for another signified, creating a “second-order semiological system”

(Barthes, 1991, p. 113).

Figure 2 The concept of the myth according to Barthes (1972, p. 113)

Mythical concepts can thus be represented by numerous signifiers, which are aligned in accordance with current cultural values. Both the signifiers as well as the relevance of the concept are not fixed but are subject to historic change and changing convention. This also means that concepts can be suppressed, popular narratives altered, or new myths created by those with power and influence

(Barthes, 1991, pp. 118–119).

For the purpose of this thesis I utilized the concept of mythologization, the creation of a myth, to explore how Oatly might represent itself as a voice, thus building a myth of Oatly as an actor in a social or political movement, and something other than a brand among its consumers and follow-ers. This myth of Oatly might be observed by looking at the way in which the company name and logo itself signifies the company, but when connected to other texts, constructs a new sign: Oatly the voice, Oatly the activist, Oatly, the not-brand. This approach acknowledges Oatly as exerting influence over the way current discourses are conceived and valued in a specific cultural context. The ability of a company to exert this type of power in a consumerist and capitalistic society is briefly touched upon by Hearn (2012) and Kettemann (2014) in my literature review.

4. P

REVIOUSR

ESEARCHThis chapter seeks to position my thesis within previous media and communication studies re-search. As the aim of my research is to determine how Oatly’s communications may be seen as indicative of them being a voice rather than a brand, it is necessary to understand what these two concepts are supposed to mean. For the purpose of my study, I understand a voice to refer to being an advocate for a public interest cause as part of a social movement. The term is thus rooted in the realm of activism. The term brand is rooted in the idea of Oatly as a company, driven by economic motivations, striving to portray itself a certain way and persuade consumers to purchase their prod-uct and is thus rooted in the realm of advertising.

Therefore in this chapter, I will summarize some key findings and positions relevant to the study of both advertising and activism communication, as well as the realm of corporate social responsi-bility and commodity activism, which helped further my understanding of how companies may

10

attempt to combine both their own vested interests (e. g. sales, company growth) and public inter-ests (e. g. environmental protection) as part of their communications and business practices. Furthermore, this chapter will briefly assess how Oatly has been approached as part of media and communications research and how my approach was inspired by the research done before mine. Both advertising and activism communications can be understood as part of strategic communica-tion: the purposeful use of communication by an organization to achieve their goal. In the case of activism, this goal would be related to promoting social causes or environmental improvement. In the case of marketing and advertising communications the goals are to create awareness and gen-erate sales (Hallahan et al., 2007, p. 6).

4.1. STRATEGIES OF ACTIVISM

According to Ricketts (2012): “community empowerment and community activism are essential aspects of a healthy democracy [...] and are vital for the process of identifying, promoting and even changing widely held social values” (p. 10). In order to fulfill its democratic function, it is important that activists are able to represent the interests of the public strategically and can successfully justify why a particular issue is of social relevance (Ricketts, 2012, p. 8).

To successfully achieve their aim, activists need to plan and execute an appropriate communication strategy, determining how issues are framed, who issues shall be addressed to and how responses shall be handled. According to Shaw (2013) one failing of many activist campaigns is that the com-munication strategy is either not well planned or is adjusted on the fly without keeping the end goal in sight, thus crippling the campaign.

Activists can be individuals or groups in various states of organization, from spontaneous protests to long-term planned campaigns. Causes are just as diverse, including environmental issues, social justice, human rights or animal welfare (Ricketts, 2012).

Often activists or activist groups are aligned with social movements, which are characterized by their values or goals, i. e. the feminist movement. Within the movement itself there are unnumbered groups, organizations, and individuals who share some or all values and work separately towards a common cause. Aligning with relevant social movements is an important tool in activism as these movements can bridge the gap between the individual actor and the state (Ricketts, 2012). When aligned with very current topics a well devised campaign, can quickly affect change by convincing elected officials to assent to the movements demands (Shaw, 2013).

In terms of activists’ motivation, Ricketts (2012) elaborates on the idea of a public interest, as opposed to a vested interest. A public interest need not be shared by a majority of society to be considered such. What does matter however, is the personal stakes of the people engaging with the

11

issue. If the activist or group of activists have personal stakes in the outcome of their activist cam-paign, their issue would be considered a blended issue or a vested interest issue. These interests and motivations can mark the difference between activism (driven by public interest) and lobbying (driven by vested interest) (Ricketts, 2012, p. 12f.). The apparent difference between a public inter-est and a vinter-ested interinter-est may influence the success of an activist campaign, as it can determine how an activist’s motivation is judged and how worthy of support they are thus considered. Ricketts suggests that, “as a public interest advocate, your motives should not be viewed suspiciously as you have nothing personal to gain other than achieving a better outcome for your community or for the planet” (p. 16).

4.2. DISCOURSES OF ADVERTISING

Cook (2001) defines advertising as one genre of discourses, whose main objective is to promote goods or services. Its main function is thus to persuade people to engage with whatever is adver-tised (p. 5-6). To do so, advertisements cannot rely on just one mode of communication in isolation but must employ multiple modes of communication including the wider discursive context. Advertisements rely on their immediate context, both in the sense of relating to other discourses and in the sense of relating to their immediate surroundings. Ads can be parasitic, meaning that they may usurp discourses in their immediate surroundings. This might be the case if an ad is printed in the middle of a magazine and elements of the ad change the perception of the surround-ing articles or vice versa (such as an ad for a car next to an article about vehicular manslaughter or an add for a vegan lipstick next to an article about animal testing). When studying advertisements should be studied within both their literal and figurative contexts (Cook, 2001, pp. 35–37).

Taking a semiotic approach to contemporary advertising discourses, Kettemann (2014) raises the point that it is no longer the consumption of goods, but instead the symbolic consumption of meaning which drives consumer decisions. As his analysis is rooted in social constructivism, it is his understanding that values and meanings are assigned by social agreement and are never fixed

(Kettemann, 2014, p. 46).

As people strive to portray themselves in the most favourable light in every social interaction, consumption (purchasing, using & ingesting of goods and services) becomes one aspect of this portrayal, thus it is no longer the product itself which is consumed – it is the meaning and the values associated with said product. As consumers define and confirm their identity through their consumption, they simultaneously reinforce the need for consumption as a basis for articulating their identity (Kettemann, 2014, pp. 45–47).

12

In order for meaning to be consumed by way of consuming goods, meaning must be transferred onto goods by correlating them with desirable outcomes and emotions. This, according to Kettemann (2014), is the prime function of advertising. Advertising is both influenced by the cur-rent cultural context and simultaneously exerts influence over the way certain cultural realities are constructed (Kettemann, 2014, p. 48).

Building on Barthes’ concept of the myth, Kettemann (2014) exemplifies how advertisements are constructed to portray certain characteristics: A women’s fragrance is advertised in warm, red tones, evocative of sensuality and temptation, while a men’s fragrance is advertised in colder tones and with images evoking action and coolness. Ideas such as happiness and togetherness as well as beauty (which is suggested will lead to the former) appear to be used frequently in advertising a variety of products and thus might be considered especially relevant to contemporary consumers

(Kettemann, 2014).

4.3. MARKETING AND COMMODIFICATION OF SOCIAL ISSUES

As certain social issues (such as social justice or sustainability) become more relevant to consumers, companies must adapt their communicative practices to ensure they communicate these values. One practice that has been observed in recent years is an increased showing of so called Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). The idea behind CSR is for companies to not only profit, but to also improve the world around them. Companies like clothing retailer Patagonia or cosmetics company Lush, have therefore adapted some practices and characteristics of grassroots activism and protest movements as part of their communications and business practices (Aronczyk, 2013; Moscato, 2016). In the case of Lush, Aronczyk (2013) dissects the company’s involvement in various protests, chal-lenging whether the company’s involvement truly benefits the social cause it supports. According to the author “Lush employs a marketing strategy strongly integrated around transparency, fair trade, human rights, and justice” (p. 7). As part of their marketing, the company has supported numerous philanthropic causes and has partnered directly with different organizations involved in political struggles.

In an effort to provide support for a number of causes, Lush had some of their stores used as campaign centers, turning their own employees into campaigners and protesters in the process. The company has planned and executed letter writing campaigns as well as poster campaigns on various social issues (Aronczyk, 2013, pp. 7–10).

Focussing specifically on the company’s campaign in support of a Canadian anti-fracking grass-roots organization, Aronczyk (2013) reveals that some of the efforts undertaken by Lush to discredit the oil industry, which in turn incited similar efforts on the opposing side, may have

13

undermined the overall effort by the environmental activists. Furthermore, it appears that Lush’s involvement in the protests ultimately only benefitted the company through its marketing proper-ties, as the company was essentially unaffected by the outcomes of the political struggle it had involved itself in, calling the authenticity of the protest into question.

Moscato (2016) engages with a different case of corporate activism, focussing on American cloth-ing retailer Patagonia. As part of a marketcloth-ing campaign, Patagonia produced DamNation, a documentary highlighting the situation of America’s waterways as a result of dam building, which was shown in US cinemas. According to the research, the viewers of the documentary positively reflected upon Patagonia’s involvement in the film production and the values the company thus embodied.

However, the author notes that this might be due to the fact that Patagonia has long embraced values of sustainability and environmental protection and its base of consumers is already inclined to support these causes as well. Thus, making the documentary more of a re-confirmation of the company’s position. According to Moscato (2016): “what Patagonia created with DamNation was not a social movement in the classic sense, but a CSR-as-activism campaign that leveraged the loyalty of its stakeholders and the beliefs of its founder and leadership into a genuine opportunity to shift public policy and enact important environmental change” (p. 112).

Taking a critical stance towards, what they call the commodification of activism Castañeda (2012) and Hearn (2012) assess processes of commodification of social issues.

As social activism is linked to positive emotions and covetable values it therefore creates a sense of “feel good” consumption if used as part of a marketing strategy. Consumers are reimagined as activists and vice versa (Castañeda, 2012). Because processes of meaning-making and identity cre-ation become more influenced by capitalism, consumption becomes a source for personal validation (Hearn, 2012). This might create an “extreme ideology of shopping as a form of activ-ism” (Castañeda, 2012, p. 288) and beget a process of self-branding of consumers, who perceive their consumption of goods marketed as socially responsible as actual activism, ultimately feeding into a culture of commodifying and consuming social issues as a result of capitalist ideologies (Hearn, 2012). Casatñeda (2012) criticises that especially minority populations are likely to find their struggles co-opted by marketing communications, without profiting from the generated awareness of their cause or the revenue it generates for the advertising party.

4.4. THE CASE OF OATLY

Possibly the greatest source of inspiration for my thesis came from a research article by Ledin & Machin, published earlier this year. The authors critically examine three different types of semiotic

14

materials produced as part of Oatly’s marketing to understand how values such as sustainability are communicated. The analysis regards Oatly’s product packaging, different street posters and a short promotional video clip. Their materials, sampled strategically as part of a focussed ethnographic approach, were collected in 2018 and 2019, prior to the German campaign on which my thesis is focussed.

Through a multimodal discourse analysis, Ledin & Machin (2020) discerned three central meaning-making principles deployed in Oatly’s communication: an evocation of a more simple, and ulti-mately better, past; a high level of meta-communication and seemingly paradoxical “anti-advertising”; and an embodied address, creating a special relationship to their audience.

Ultimately, Ledin & Machin (2020) conclude, that Oatly’s communication is evocative of values such as sustainability, eco-friendliness, health and free choice, but does not address any of these issues head on, thus, rendering their marketing highly effective, but empty of actual potential for real life change. According to the authors Oatly’s messaging appears to end with the purchase of an Oatly product – replacing real-life political change activism with simple consumption, of a chic and adversarial branded product.

It would be remiss of me not to point out, that Oatly currently seems to be quite a popular topic for master’s level theses in media and communication studies as well as other disciplines. During my initial research stage, I encountered two theses by media and communication studies students: Firstly, a thesis which comprised of a rhetorical analysis of Oatly’s packaging and a secondly, a thesis which researched the way in which consumers engage politically with Oatly, through a series of interviews. After being at first intimidated, I assured myself that my research approach was different from those already implemented. I am sure there are more such theses out there and I hope to add my own to a growing canon of literature on this company.

5. R

EVISITINGM

YR

ESEARCHQ

UESTIONThe previous chapters have provided the background of my research, introducing the metaphorical giants on whose shoulders this thesis stands. Before moving on to my analysis, I will briefly revisit my research question.

RQ: How does Oatly communicate as a voice rather than a brand in Germany?

I took the term voice to mean an actor engaged in advocating for a public interest cause, in short: an activist. As Ricketts (2012) describes, such an actor would need to identify and promote relevant social values and attempt to advance changes that are of a wider societal relevance. For an activist campaign to be successful it is considered useful if it is part of a larger social movement (Ricketts, 2012).

15

Activists are engaging with matters that are of a public interest, meaning that if the aims of the campaign are achieved, the benefits will not only befall the activist, but rather society at large. Companies, or brands, are more likely to be communicating vested interests, meaning that the results of their campaign will directly benefit themselves. In fact, any advertising communication could be considered driven by a vested interest, as the aim of such communication is usually related to persuading consumers to engage with the advertised product or brand (Cook, 2001; Hallahan et al., 2007).

At its core my research is concerned with the way meaning is created and how those meanings can serve to create a myth, a piece of knowledge as part of a specific cultural context. Specifically, this thesis regards the way in which different materials produced by Oatly communicate the company’s aspiration of being a voice in current political and social discourses and how these meanings might be received by an audience. Some of the discourses identified in previous research, that may be of relevance to my thesis are: social justice, environmental protection and sustainability.

As acknowledged in my literature review, there is ample academic evidence of companies contrib-uting to social and political causes as well as of companies co-opting the feel and look of activism for the purpose of advertising, without contributing to the actual political struggle. According to Ledin and Machin’s (2020) research, Oatly falls somewhere in the latter category, as the company does appear to align itself with current social change discourse, but does not seem to actually try to affect any social change.

I should clarify that the aim of my research is not to determine whether Oatly is a brand or whether the company could be considered an activist. Such a discussion would not be productive. At the end of the day Oatly is a company, despite their protestation to the contrary. A company with high profile investors and an expanding range of products which they intend to sell. While my research can support claims regarding the company’s ethos and commitment to certain social issues, the economic interests would always render any efforts of engaging in social issues a vested interest, and thus be considered closer to lobbying. It should however be noted that neither lobbying nor activism are inherently good or bad practices (Ricketts, 2012). But these type of judgements are ultimately irrelevant for this thesis, which is simply aimed at discerning how Oatly employs com-munication in a particular context and how I as a reader can unveil their meanings.

6. R

ESEARCHD

ESIGNWhen first designing my research, I was planning on focussing on the visual properties in Oatly’s communication and conducting a visual analysis built on social semiotics. However, it quickly be-came clear that such an approach would simply not do my research aim justice. Ultimately, I

16

followed the example of Ledin & Machin (2020), choosing to observe my chosen materials through a multimodal discourse analysis, opening my analysis to include a plethora of aspects of communi-cation and leading to what I feel was a more nuanced discussion of the way Oatly might employ semiotic resources to affect the way they are perceived as part of current discourses and how these might be received.

My research was designed to firstly, determine some of the discourses manifested in Oatly’s com-munication, and the position Oatly takes in these discourses. Secondly, I hoped to discover how these discourses where signified as part of Oatly’s communication and might be understood by an audience. And thirdly, I endeavoured to discern how the semiotic potential of my chosen materials might help to conceive of a myth of Oatly; the voice, not the brand.

6.1. MULTIMODAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS

We experience the world through multiple senses and are exposed to information through a variety of media employing different modes of communication. We therefore make meaning by synthe-sizing the different signifiers presented to us through different semiotic resources. Consequently, it is appropriate to approach social semiotic research with a methodology which accounts for dif-ferent modalities rather than being constrained only to one discipline (Chandler, 2007).

Multimodality has emerged as term to emphasize the ways in which meaning is created and trans-ported not just through language, but through other modes of communication (visual, space, digital) (Ledin & Machin, 2018). Rather than considering individual signs and the meanings they might connote, a multimodal approach is concerned with the way signs are employed in combina-tion with each other; uncovering their meanings in context of each other and their social context (Machin, 2007, p. ix). According to Machin (2007) semiotic resources are deliberately chosen to be employed, a process which is never neutral, but always motivated by the interest of the person or entity producing the text in question (p. xxi).

According to Ledin & Machin (2018) multimodal discourse analysis is one strand of multimodality, which is concerned with the social aspect of communication, combining aspects of critical dis-course analysis and visual analysis and lending itself to an analysis rooted in social semiotics (p. 27). The authors employed this methodology to ascertain how popular discourses of sustainability and ethical consumption were evoked in different modes of texts by Oatly (Ledin & Machin, 2020). My approach in this thesis follows an interpretivist-constructivist paradigm, meaning that it is the underlying epistemological assumption, that reality is created through perception and interpretation by those experiencing it. There is no objective truth and knowledge about the world and human

17

experience are constructed based on individual previous knowledge, experiences or research (Blaikie, 2007, p. 23).

Accordingly, this research is aimed at understanding social phenomena from the perspective of experience. As a researcher it is therefore common to take the position of ones research subject, or close to it (Schwandt, 1998, p. 229). In my analysis my own position was akin to that of a consumer encountering Oatly’s communications and critically assessing them.

6.2. SAMPLING AND MATERIAL

For my research, I chose to analyse three types of texts:

- The text of the petition posted to the Bundestag’s petition forum, - Two photos of different posters advertising the petition in Berlin, - The packaging of selected Oatly products available in Germany,

The types of text were chosen, as they are all deployed in different spatial and ideological contexts. While the petition text is available online, to anyone who might peruse the Bundestag’s petition forum, regardless of physical location, the posters were on display in specific fixed locations across Berlin, accessible to anyone physically walking past them. The packaging was obtained in Berlin supermarkets, however Oatly’s products are available in different locations throughout Germany. Because the texts are all displayed and accessed in very different ways, they were unlikely to ever be seen side by side in the same moment and might ultimately reach completely different audiences. Furthermore, the texts were chosen because they presented disparate properties with regard to size, space, text, images and materiality.

Since I had limited my research query to specifically look at Oatly in Germany other texts such as Oatly’s website or social media channels were dismissed because content is often shared and re-used across different national platforms and it would have been difficult to ascertain whether a chosen text was specifically aimed at a German audience or not.

The photos of the petition billboards were used in several newspaper articles and blog posts, with Oatly being repeatedly identified as the original image source. I therefore considered the photos as well as the posters depicted in them as official material produced by Oatly.

The product packaging was collected by way of a convenience sample: Since I was unable to visit a German supermarket and obtain any products myself due to the Covid19 travel restrictions which were in place for most of the year, I instructed my sister to purchase products on my behalf. The selection of products therefore represents the products she was able to procure during the summer. In total I was able to consider nine different product packages as part of my analysis. There are currently 18 different products available in German supermarkets (Oatly, n.d.).

18

6.3. REALIZATION OF RESEARCH DESIGN

Through a multimodal discourse analysis, my aim is to uncover the ways in which Oatly attempts to communicate not as a brand, but as a voice, an advocate in a social and political effort. In my analysis I will focus on different modes of Oatly’s communication: language (written text), images, space and context and the way in which these are employed to make meaning. To answer my overall research question, I devised sub-questions, which served to relate my analysis to the theoretical framework of my research.

- What are the most relevant discourses alluded to in Oatly’s texts? - How are these discourses represented in these texts?

- How is Oatly positioned within these discourses?

- How can these semiotic resources be seen as being employed to evoke a myth of Oatly as a voice, or an actor in a movement, among consumers?

While these questions helped to guide me through my analysis, I did not let them become blinders, but instead allowed for any additional insights that might spring up from the material to influence my examination. Schwandt (1998) suggests, that in research conducted under a constructivist-in-terpretivist paradigm, it is common for the researcher to be led by their research material rather than their framework (p. 221).

6.4. ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Ethics are the principles by which we judge our behaviour. In general, our western understanding of an ethical person would describe someone who upholds values such as justice, fairness and autonomy (Croucher & Cronn-Mills, 2014, p. 12). Theses principles should also apply when con-ducting research, therefore this chapter will address my ethical considerations in writing this thesis. Croucher and Cronn-Mills (2014) name Plagiarism as one of the most common cases of unethical (and in fact, prohibited) behavior in academic writing. Plagiarising is defined as the use of another author’s work or ideas without giving due credit. In writing this thesis (and indeed any previous academic text) I took great care to always include references to words or ideas taken from another’s work.

One of the principles of ethical conduct highlighted above is autonomy. After choosing the topic for this thesis I joked with friends that it would make an excellent addition to an application, should I ever decide to apply for a job at Oatly. This would present a clear conflict of interest and might impact my ability to remain impartial and critical in my assessment. As I have no present or planned future affiliation with Oatly, I judged the risk for such a conflict of interest to be minimal. However, as my research is concerned with advertising material, which is aimed at persuading the reader of

19

the company’s values and integrity, I felt it was especially necessary to maintain a critical mindset and not accept all of Oatly’s communications at face value.

6.5. LIMITATIONS

As Schwandt (1998) acknowledges: “Constructivists are deeply committed to the contrary view that what we take to be objective knowledge and truth is the result of perspective” (p. 236). If we assume that reality as such exists only as we create it through our interpretation against our specific cultural and individual background, each of us creates their own reality. According to Chandler (2007) there is no reading without rewriting, as every reader will automatically fill text with their own assumption and knowledge. Thus, ultimately my research reflects my reality as I perceive it and create it. All I can hope to offer with this thesis is a glimpse into my thought process and one possible reading of my chosen texts. I found this sentiment well expressed by Fairclough (2003) stating, that all textual analysis is inevitably selective, as “we choose to ask certain questions about social events and texts, and not other possible questions” (Fairclough, 2003, p. 14).

As mentioned in my ethical considerations, I was aware of the necessity to remain critical and impartial in my analysis. However, I did choose this research topic based on my personal interest in both Oatly as a company and the topics of activism and advertising. Therefore, my own position as a researcher might be too close to my subject. I have spent quite an extensive amount of time (nearly 7 months), working on this thesis and an even longer amount of time following Oatly and observing their communications and business practices. For that reason, I would consider myself well versed in all things Oatly. This might pose a problem, as I cannot regard Oatly’s materials with fresh eyes. I tried to mitigate negative effect of my own pre-conceived notions on my analysis as best as I could.

7. R

ESULTS&

D

ISCUSSIONIn this chapter I will first present the results of my analysis for each type of text individually, before discussing them in relation to one another, thus highlighting the way in which context may change how meanings are created.

7.1. OATLY’S GERMAN PRODUCT PACKAGING

The packaging of a product is the semiotic material which directly connects the consumer to the brand via the product. The packaging is what the consumer encounters in the supermarket and takes home into their private space. In the supermarket these materials are encountered in accord or in opposition with other brands and other products and, in the case of a first-time consumer, must be persuasive enough to convince them to purchase, or, in the case of a repeat consumer, must be instantly recognizable.

20

Oatly’s product packaging underwent significant changes under the direction of John Schoolcraft, who describes the design as looking as if the packaging had been handprinted in a basement with a potato (Alagiah, 2018). Ledin & Machin (2020) describe the design of the packaging as simplistic and child-like naive, noting in particular the uneven print of the company logo (see. Fig 3) and other icons, the choice of fonts, as well as the washed-out color palette.

Amongst my sample, I noted that every product packaging seemed to have its own base color, although I noticed that for both products that were marked as “Bio” (eco), the carton was a shade of beige. On every product the Oatly logo is printed onto the initially customer facing side (i. e. the front of drink cartons and the top of the spreads), taking up about one third of the space on that side and placing Oatly as a brand front and center in all the discourses evoked on the packaging. The discourses that are represented on the packaging revolve around food consumption and pro-duction and sustainability as well as alternative lifestyle choices and the empowerment of the consumer.

Discourses concerning food consumption and production are perhaps the most expectable, given that Oatly’s products are in fact foodstuffs. The front of each packaging gives only a product name (usually the word Hafer (oats) with another descriptor such as “deluxe” or “Barista”). Underneath, food is represented by way of a simple drawing relating to the respective products; in the case of the drinks, this is a drawing of a glass or a coffee cup, for the cooking cream it is drawing of a saucepan and for the spreads it is a drawing of a piece of bread. Oatly, as a brand, is directly present in this food related discourse. The packaging design directly links the brand logo (at the top) through an arrow or similar shape, to the drawing below. The order of operations is clear: Oatly is identified as the provider or producer of a product (whose name is written on the arrow) which is made to be consumed. I noticed that the product names did not necessarily reveal what the exact nature of the product was. This is usually revealed on the back of the packaging, where alongside ethe mandatory indications of ingredients and nutritional values, the product is identified as an oat drink, a spread on the basis of plant materials, or a plant cream suitable for cooking.

Further discourses surrounding food are represented by indicating that some of the products in-clude “no milk, no soy”, “oh wow, no cow” or the notice that the product is vegan (both can be seen in Fig. 4). As Oatly is presented on the packaging as the provider of this vegan product, the brand is thus seen as aligning with discourses surrounding veganism, which might be seen as ex-tending to discourses of sustainability and ethical consumption. While Oatly is positively aligned Figure 3 Packaging Detail: Logo

21

with veganism, the indicator that the product includes “no cow” or “no milk”, places Oatly as adversarial to those products, and by extension to their producers.

This adversary, as well as further knowledge regarding sustainability and the environ-ment are referenced in the texts on the sides of some packaging, which include a missive addressed to the food industry (see Fig. 5). The message points out in a flippant and humorous tone that while it is possible for an individual consumer to ascertain the en-vironmental impact of flying, it is barely possible to unmask the environmental ben-efits of choosing oat drink over milk. Linking the consumption of milk as opposed to oat drink to CO2 and flying, well known contributors to air pollu-tion and climate change, suggests the gravity of the choice between milk and oat drink, which is further heightened as the text asserts that the food industry is responsible for twice as many emissions of greenhouse gasses as the transportation sector. Due to the importance of the deci-sion, the text continues, it is necessary to inform consumers of the CO2 footprint of their food, so they can make informed decisions. In the same text, Oatly also announces that it will begin labelling all of its products, daring the food industry to match their actions.

Oatly addresses the food industry from an outsider’s po-sition. There is a clear differentiation between “you” – the food industry, which causes pollution and environ-mental destruction and tries to obfuscate it and “we” – Oatly, who has nothing to hide and are making its impact known, so the consumer is better informed. Oatly clearly tries to separate itself from the food industrial complex of which it is very much a part. This is further Figure 4 Front of Packaging: Hafer Cusisine Bio and Hafer Bio

22

substantiated by Oatly seemingly making good on its promise and indicating a climate footprint in the bottom corner of the front of the packaging (see Fig. 6). This footprint, however, is currently only indicated on those product packages which also display Oatly’s message to the food industry

(in my sample: Barista and deluxe).

While the missive does not state explicitly that oat milk would be the more sustainable choice or that the more sus-tainable choice is the one consumers should make for moral reasons, both of these beliefs can be inferred from the con-text: the fact that the text is printed on the packaging of a vegan, oat product, which repeatedly points out that it is vegan and free of milk, and of course the fact, that the need for environmental protection and the fight against climate change have become buzzwords, reported in media and proclaimed at protests, clearly making them the ethical and morally right cause to support through ones consumer choices. As Kettemann (2014) described, products are charged with meaning that go beyond the actual product. In the case of Oatly, the product actually seems to take somewhat of a backseat; the name does not reveal what the product actually is, and the visual representation is a fairly simple drawing, the focus of the packaging therefore seems to be on other easily recog-nizable meanings, such as veganism or sustainability.

In addition to veganism, some of the packaging also nods at other lifestyle choices and related activities. The inside of the labels on oat spread packages reveal an oat inspired horoscope, a list of lucky numbers and a word puzzle. These kinds of texts are easily associated with leisure activities, fun and in the latter two cases, perhaps also with alternative beliefs. They give the impression that Oatly celebrates quirkiness and non-conformity. These texts, unlike the outside of the packaging are also only visible to the consumer who has already purchased and consumed the product, thus creating an air of secrecy and comradery. Imagining a zodiac sign “the oat” (see Fig. 7), actually gives consumers a concept with which to personally (most likely jokingly) identify.

Figure 7 Packaging Inside: The Oat Horoscope Figure 6 Packaging detail: CO2 footprint

23

The final text I will discuss, printed on the side of packaging for Hafer deluxe, opposite the challenging message to-wards the food industry, addresses the consumer directly. Next to a large drawing of a pointed finger, reminiscent of images such as Uncle Sam telling the youth of America to join the US army, Oatly proclaims that “You are now one of us” (see Fig. 8). The following text is written in a some-what rambling tone, emphasizing repeatedly, that the reader and Oatly are now part of a group of people making the lifestyle choice of consuming plant based products, benefiting the planet in the process. In the text, Oatly aligns itself with the reader, by indicating that they are both now part of the same movement. At the end of the text there is a reference to the author being “just an honest person”. In the context of the packaging, this “person” becomes one embodiment of Oatly, pointing the finger at one specific person, the reader, and telling them they are now involved in what is revealed as an ongoing social struggle, and prac-tically giving them no choice but to agree with the sentiment of being part of that movement. The references to honesty and the benefits of “eating and drinking plants” for both the consumer and the planet, define the consumer as an empowered and ethical being.

One aspect of the packaging that might change how its meanings are perceived is the language: while the product names use the word Hafer and the legally required product information are pro-vided in German, the majority of texts discussed in this chapter are written in English. On one hand this could signify inclusivity, as English texts are accessible to people from many different backgrounds. On the other hand it could mean the opposite, as about 30% of the German popu-lation do not speak any language other than German and the country is ranked behind other European nations when it comes to the populations English proficiency (Trentmann, 2013). It is therefore questionable to which degree a random consumer reading the packaging in the super-market might understand which discourses are evoked on the packaging.

Furthermore, I have to question if a consumer would actually read the entire packaging, or in fact the packaging of multiple different products. Some of the discourses might only appear as brief throwaway mentions when observed in isolation and only reveal a pattern of Oatly strategically Figure 8 Packaging Side: Pointed Finger of Morality

24

positioning itself as part of these discourses, when observed in combination between different materials.

7.2. THE PETITION POSTERS

The next materials which I will observe for my research are two images of posters, advertising petition 99915, in Berlin. The first image (Fig.1, seen on p. 1) shows a larger poster displayed on scaffolding on the face of a building. The second image (Fig. 9) shows three posters which are mounted along the underground train tracks at Berlin Alexanderplatz.

Both posters share the same individual elements; a written prompt, a drawing of a raised fist clutch-ing a pen, the link to the petition, and Oatly’s logo, all in front of a light blue background. But while the first text shows them all in one coherent format, the second breaks the content up into three parts, which may be observed individually or in combination, depending on the reader, and thus changing the way the connections between the elements are perceived.

The first half of the prompt is written in black and simply reads “sign the petition”, the second half is written in white and offers a little more information on the petition, namely that it’s goal is to make CO2-labels on foodstuffs mandatory by law. The font, reminiscent of the font on an old-school digital display, is the same as the one used to introduce Oatly’s message to the food industry on their packaging.

The image of the raised fist is stylized in a similar style as the text, reminiscent of video games or other digital media. The semiotic potential of language is defined as the sum of its common uses (van Leeuwen, 2005) and raised fists are commonly associated with political or social struggle, often raised by those fighting injustice or oppression in solidarity with the cause and those fighting along-side them. Therefore, the image might here be understood as a sign of empowerment. The fist is shown clutching a pen – possibly evoking ideas such as “the pen is mightier than the sword”. The mention of CO2 once again elicits the urgency of protecting the world from pollution, how-ever this time the positive action to counteract these negative effects, is not through consumption, but through political action – along a path provided by Oatly, who are represented by their logo as well as the petition link, which apparently reroutes through Oatly’s website.

The single poster (Fig. 1) spans the entire height and width of scaffolding on a building, making it very hard to miss and imposing over its surroundings. Oatly’s logo in the bottom right corner and the petition link, positioned on to the left of the raised fist, are the smallest elements on the poster, with the raised fist, and thus the concept of social struggle, of solidarity and of empowerment, taking center stage. Another discourse invoked on the poster is that of government power – after all the demand of the petition is that a new law be ratified. In the context of the poster, government

25

power is seen as a positive force for change, as it is positioned in opposition to negatively connted CO2. In the order of operations, Oatly appears to be presented as a facilitator of a political struggle, providing a way for the public to make their voice heard and affect important change. Oatly is represented as diminutive next to the might of the raised fist of empowerment.

This hierarchy of discourses changes, when regarding the posters pictured in Figure 9. Where pre-viously Oatly appeared only as a small part of the whole, being aligned with the empowered public and supporting and facilitating their struggle towards political change, in the arrangement of the three posters the sizing of the individual elements paints a different picture.

Figure 9 Trio of Petition Posters at Alexanderplatz train station, Berlin

Note: This image was retrieved from Herrmann (2019), where the image is accredited to Oatly. (Herrmann, 2019)

The first poster on the left bears only the company’s logo. Oatly appears the same size as the raised fist in the second poster and the prompt and its clarification on the third. Due to this arrangement the three elements appear equal in importance. When reading the posters left to right, like I did for my analysis, Oatly actually appears as the first concept presented to the reader, with the petition taking a backseat. However, this may not be true for a commuter standing on the platform and waiting for the train, as some of the posters may be blocked by other people or they might simply chose not to look at all posters or even notice that they belong together.

Another possible meaning of the three posters could be that the raised fist is actually representative of Oatly as the challenger or the underdog, fighting the might of the food industry and needing the help of the public, who is directly addressed in the prompt to sign the petition and the government, who can make the desired changes to the law. Ricketts (2012) points out that social movements