Interaction Design meets Marine

Sustainability

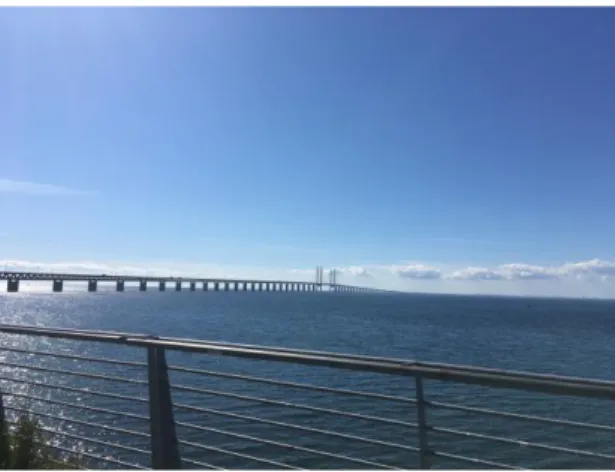

Mixed Reality Tour near the Oresund Bridge

Valentina Ustinova

Interaction Design One-year master 15 credits

Semester 2/2020 Supervisor: Susan Kozel

2

Abstract

This study investigates an Interaction Design approach as a tool to unfold complex topics. By making a bridge between IxD and AR/MR, it addresses a field of Marine Sustainability to find a way how IxD can contribute to it while coinciding with its values and goals. The design process results with the development of Mixed Reality tour where following the narrative, users move across three locations investigating past, present and possible futures of the Oresund strait. The final concept contributes to the discussion about the role of IxD in addressing experiential qualities of AR/MR and demonstrates how Interaction Design can contribute to Marine Sustainability in a way that is different from a technology-driven approach.

3

Contents

Abstract ... 2

Contents ... 3

1 | INTRODUCTION ... 7

State of the field ... 7

Problem definition ... 7

Study motivation ... 8

Research focus ... 8

2 | BACKGROUND and THEORY ... 9

2.1 | Context: Understanding Marine Sustainability ... 9

A fundamental role of big water and human perception ... 9

Marine Sustainability ... 9

Role of Environmental Education in Marine Sustainability ... 10

Goals of Environmental Education ... 10

Facing complexity and ambivalence ... 11

Audience and stakeholders ... 11

2.2 | AR/MR/VR – from a lab to media culture ... 12

Before-smartphone definitions. Milgram-Azuma approach ...12

Smartphone era: Barba-MacIntyre approach ...13

Transformations in the field ... 13

What do authors suggest? ... 14

Definition ... 14

Concepts ... 14

Frames ... 15

MRx: defining the experience in MR ...15

Definition & goals ... 15

Qualities ... 16

Diagram ... 16

Lenses ... 17

Shortly about VR in IxD ...17

2.3 | Design examples ... 18

4

Infinite Scuba (2017) ...19

Remote X | Rimini Protokoll (2013) ...20

Next to you at Korsvägen (2017) ...21

Parascope (2009) ...22

3 | METHODS and METHODOLOGY ... 23

3.1 | Literature reviews ... 23

3.2 | Interviews ... 23

3.3 | Observations ... 24

3.4 | Mind Mapping ... 24

3.5 | Sketching and Prototyping ... 25

Sketching ...25

Prototyping ...25

3.6 | Storyboards ... 26

3.7 | GDPR statement ... 26

3.8 | Project plan ... 27

Discover and Define ... 27

Develop and Deliver ... 28

4 | DESIGN PROCESS ... 28

4.1 | Discover ... 28

Interviews with experts ... 28

Outline ... 28

Motivation ... 28

The method in details ... 28

A view from IxD ...29

A view from oceanography and environmental education ...30

A view from scenography ...31

Refined goals ...32

4.2 | Define ... 32

Focus, Observations, Ideation ... 32

Focus ...32

Observations near Oresund bridge ...32

Motivation ... 32

Method in details ... 32

Results ... 33

Design takeaway ... 33

5 Motivation ... 34 Method in details ... 34 Results ... 34 Design takeaways ... 35 Ideation ...35 Mind mapping ... 35 Sketching ... 36 Design direction ...36 4.3 | Develop ... 37

Prototyping and Testing ... 37

First exploration ...37

Prototyping ...37

On-site user testing ...40

Results ... 40

Feedback from experts ...42

Results ... 42

5 | MAIN RESULTS AND FINAL DESIGN... 44

5.1 | Main Results ... 44

Outdoor application of AR ... 44

Interactions and visuals ... 44

Off-site use and accessibility ... 44

Role of the narrative ... 44

Time ... 44

Technical consideration ... 44

5.2 | Final design ... 45

Mixed Reality tour near the Oresund bridge ...45

Journey overview ...46 Details ...47 Concept overview ... 47 Visuals ... 47 Narrative ... 47 Interactions ... 47

6 | DISCUSSION ... 48

The final outcome ... 48

The design process ... 49

6

7 | CONCLUSION ... 50

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... 50

REFERENCES ... 50

APPENDICES ... 56

1 | Interviews ... 56 Marika Hedemyr ...56 Domenico Sgambati ...63 Varja Klosse ...672 | Mapping of the area near the Oresund bridge ... 72

7

1 | INTRODUCTION

State of the field

As envisioned by Winograd, there is a significant expansion of computing aspects focusing "on people, rather than machinery", which is emphasized in Interaction Design (IxD). (Winograd 1997, p. 156) Nevertheless, Löwgren (2002) argues that IxD can go further than just adopting new technology to existing users, but being "about exploring possible futures, where the users as well as the technology are different from today". (Löwgren, 2002, p. 187) Further, IxD approach supports the investigation of existing technology from a different perspective, revealing new possibilities and future applications – by turning the focus from technology itself to the experiences it may provide.

In recent years, Augmented Reality (AR) and Mixed Reality (MR) is a growing phenomenon, supported by the evolution of portable devices and the ubiquity of Internet access. (FitzGerald et al., 2012; Lee, 2012) Although AR/MR implementation in different fields is more accessible than ever before, yet it is not addressed in IxD in its full potential.

For the last two decades, there has been a significant shift in AR/MR research in HCI and IxD. While moving from specially build technologies for AR and MR to the smartphone ecosystem, researchers have started to review fundamental definitions of AR/MR to adapt them for the current context. (Barba et al., 2012; Rouse et al., 2015) Moreover, researchers have opened discussions about the experiential character of AR and MR and introduced vocabulary and instruments for describing and evaluating various aspects of AR/MR experience. (Barba et al., 2012; Barba & MacIntyre, 2011; Rouse et al., 2015)

Most of the theories and applications are, however, centered on the technological aspect. Researchers argue that as AR/MR works start to enter daily life, it becomes more important to recognize their historical, cultural, and aesthetic perspectives. (Barba et al., 2012; Rouse et al., 2015) Moreover, various authors suggest considering how these technologies link with fundamental areas of life to serve social needs and purposes, emphasizing the significance to direct them towards constructive goals. (Barba et al., 2012; JafariNaimi, 2015)

Problem definition

Blevis (2007) defines design as an "act of choosing among or informing choices of future ways of being" (p. 503). His article on Sustainable Interaction Design opened a discussion about the role of sustainability in IxD, arguing that it can and should be a central focus of interaction design. From the perspective of design values, Blevis mostly concentrates on materials, objects, and design choices that lead to sustainable futures. In addition to this, Mankoff et al. (2007) describes a concept of Sustainability through Design, focusing on cognitive aspects of sustainability – "how to influence sustainable lifestyles and decision-making through design and technology". (Mankoff et al., 2007, p. 2123) It includes providing information to raise awareness, influence sustainable behaviours, stimulate reflection and engagement in sustainability issues. Nunes & Alvão (2017) note that one of the challenges in this approach is that many studies focus primarily on providing information to raise awareness, while technologies should create a reflection about the meaning of sustainability and connecting reasoning to user’s motivation and values.

8

Nunes & Alvão (2017) also suggest the dialogue between IxD and other areas that address sustainability. Authors acknowledge the lack of researches in different contexts and believe that a multidisciplinary approach can provide methods, concepts, and ideas contributing Interaction Design field. Taking this into account, this project approaches marine sustainability – the area which is not addressed enough in IxD research. Moreover, there is no previous research combining both marine sustainability and AR/MR experience.

Marine sustainability can be viewed from different perspectives. Roff & Zacharias (2011) suggest 3 main categories of values, why marine sustainability should be considered: Intrinsic Value (independent of human needs), Anthropocentric Value (human-centred), and Ethical Value (moral responsibility).

Marine protection is an enormous challenge, primarily because it requires motivating people who may have no physical connection to marine areas to experience and understand them. (Colleton et al., 2016) McMillan et al., (2017) suggest that technologies may have great potential as an effective tool to motivate an interest in and empathy for marine environments at a global level.

Within the literature and on the market, we can find several AR and VR materials addressing environmental topics, environmentally aware consumer behaviour, and even experiments with its underwater use. (Koutromanos et al., 2018; McMillan et al., 2017; Vasilijevic et al., 2011) However, there is a lack of examples addressing both sustainability (especially marine sustainability) and the experiential aspect of AR.

Study motivation

The motivation for this study arises from investigating a complex field of Marine Sustainability and intention to find a way how IxD can contribute to it. Besides that, dealing with marine environments means addressing hidden and, in some sense, invisible things and factors, while IxD may help to approach and unfold this topic.

Furthermore, most of AR/MR works are mainly technology-driven, and IxD approach may help to get away from tech-centred agenda in a heritage segment. It could be stated that IxD decisions are not based on the optimal conditions to work with the technologies but aim to contribute to the whole experience.

Finally, the motivation for this study goes beyond just anthropocentric category of values, arguing that marine sustainability should be considered regardless of particular human needs or interests. However, as human beings, we may explore and address it with the existing tools trying to engage a user in a physical and emotional dialogue. (Kolko, 2011)

Research focus

The research question is: How can Interaction Design address current problems faced by Marine Sustainability?

In particular:

• How can IxD coincide with three main values, but also expand them to consider the role of AR/MR experience?

• How does location-specific use influence AR/MR experience? • What are the learning and experiential outcomes for the user?

9

Expected design contribution is an interactive artifact using experiential qualities of AR/MR in the IxD framework to address Marine Sustainability.

2 | BACKGROUND and THEORY

2.1 | Context: Understanding Marine Sustainability

A fundamental role of big water and human perception

The oceans play a fundamental role in the functioning of our planet. Since the oceans are responsible for the regulatory control of conditions on earth by regulating the global climate, water is the essential ingredient of and for all life as we know it. Moreover, scientists assume that oceans could successfully exist without land, but earthly life without the goods and services of the oceans is unthinkable. (Roff & Zacharias, 2011)

Oceans have been traditionally viewed as an inexhaustible resource and for a long time, society believed that human actions can not affect a state of the ocean. However, now the oceans are distressed by human activities and continue to degrade – we are destroying biodiversity by reducing the number of species, having an impact on habitats and their communities, and indeed damaging the whole ecosystem. Moreover, human perception of the natural state of the seas and oceans experience gradual change because people tend to normalize the current conditions of nature. Roff & Zacharias (2011) argue that "although the oceans are progressively being degraded, each human generation comes to accept the degraded state as the norm". (Roff & Zacharias, 2011, p. 4)

The concept of the global village (McLuhan, 1962) has become very obvious these days – human civilization has reached a point where its actions can cause changes at the planetary level. Moreover, global issues, including climate change, the rising level of CO2 and global warming, now dominate our environmental concerns. In addition, the current pandemic contributes to the experience of this concept, showing a global connection. Besides that, demonstrating how fast nature recreates itself without human activities.

Marine Sustainability

The concept of sustainable development originated from the UN Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm in 1972, where it gets defined as "development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs". (EASAC & European Commission, 2016, p. 10-11) Further, in 2015, the UN General Assembly adopted a sustainable development goal "to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources". (EASAC & European Commission, 2016, p. 11) Despite that, the concept of marine sustainability is not new, as the sustainable use of the seafloor was first addressed in 1992.

As mentioned in the report, the seas around Europe have their specific oceanographic character, distribution of species and ecosystems. In each case, the regulation of marine environments is at a different stage of development. (EASAC & European Commission, 2016)

10

Role of Environmental Education in Marine Sustainability

Educational activities are an essential element to transform the outline of environmental degradation and to lead the change towards sustainable development. According to the UNESCO report, “education is the primary agent of transformation towards sustainable development". (Education for Sustainability, 2002, p. 9) Providing scientific and technical skills, it also gives the motivation, justification, and social support for employing them. The concept of Environmental Education was one of the major topics on the UN Conference on the Human Environment held in Stockholm in 1972. After the conference, it was concluded that environmental education should be recognized and promoted in all countries. (Education for Sustainability, 2002) Moreover, it plays an important role in understanding the natural world and human relationships to it and is part of much wider struggles regarding processes of local development and environmental management. (Blum, 2012)

Environmental education is held in different ways and the most popular are the engaging activities that combine leisure and education, particularly while working with kids and teenagers. (Ham & Krumpe, 1996) Educational activities could be held by many types of organizations, for example conservation units – in particular, marine protected areas (MPAs) – focus on biodiversity conservation, merging it with scientific researches, and, in some cases, public visitation and educational activities. (Topanotti et al., 2019) Often MPAs become hubs of environmental education, offering guided tours and organizing educational programs.

Some places allow combining environmental education with historical and cultural context. For example, Italian MPAs, like Punta Campanella1 in Campania and Porto Cesareo2 in

Puglia, are rich with sightseeing on the land and develop guided tours and educational programs including both environmental and cultural context. It enriches engagement and interest from the general public, like tourists. Moreover, it provides a context to imagine and understand how nature in a specific area is changing through time because of human impact. Another example is Marine Educational Centre Naturum3 – the visitor centres with activities and exhibitions, located at several of Sweden's national parks and nature reserves. Visitor centres offer a wide range of educational activities like guided walks, exhibitions, information about the area's national parks and nature reserves.

Goals of Environmental Education

The main guidelines for Environmental Education are stated in the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP, 1975). According to this document, the goal of environmental education is:

to develop a world population that is aware of, and concerned about, the environment and its associated problems, and which has the knowledge, skills, attitudes motivations and commitment to work individually and collectively toward solutions to current problems, and the prevention of new ones.

1MPA Punta Campanella https://www.puntacampanella.org/ 2MPA Porto Cesareo http://www.ampportocesareo.it/

11

Central objectives to achieve the goal are awareness, knowledge, attitude, skills, evaluation ability and participation.

Facing complexity and ambivalence

One of the difficulties of Environmental Education is that the field is quite broad and covers a wide range of audiences, applying a variety of methodologies and instruments. Environmental issues cover topics that are diverse in origin, time and space scale, and control forces. Kassas (2002) offers three main systems, which overlap in Environmental Education: environmental issues may be perceived both within limited space and global scale; they may relate to many disciplines – ecology, societal pressures, scientific constraints; these issues are multi-dimensional as they relate to interactions among nature, sociosphere and the technosphere.

Another challenge is the perceived remoteness of seas and oceans. It requires motivating people who may have no physical connection to marine areas to experience and understand them (Colleton et al., 2016). People mostly are familiar with the natural structures of the land – mountains, canyons, forests – and its inhabitants, but we have no such perception for seas and oceans (Roff & Zacharias, 2011). Thus, the curiosity about the marine environment needs to be awakened.

This means that environmental interactions and processes of sustainable development are “not linear, and therefore complex, not easy to grasp, and linked with ambivalence and uncertainty”. (Kassas, 2002, p. 346) May IxD approach be beneficial to address it? As mentioned by Kolko, a design process is "a way of organizing complexity or finding clarity in chaos". (Kolko, 2011, p. 15)

Audience and stakeholders

The target audience of Environmental Education is the general public. This global and very broad outline usually is divided into two main education sectors: the formal: school-based; and non-formal: much wider range of audiences, outside of formal school system. (Ham & Krumpe, 1996; UNEP, 1975)

For example, for natural parks and MPAs, site-based educational activities play an important role because their target audiences are more likely to impact protected resources. Ham & Krumpe (1996) define two priority audiences for site-based education: on-site visitors and local communities. On-site visitors may consist of adults and children, national and foreign tourists. Local communities may include many different audiences (school children, business owners, community leaders, etc.).

Authors describe the on-site public as a noncaptive audience that freely chooses to attend or ignore communication content. Therefore, site-based education should not be viewed as teaching or instructional activity in the academic sense – it must be enjoyable, engaging, and able to capture and maintain attention. Finally, the goal is not just to teach the specific material about the environment, but primarily to familiarise the audience with the marine environment and its inhabitants, building a foundation for emotional connection. Thus, the message must have a clear organization and a central point to be understood by the audience. (Colleton et al., 2016; Ham & Krumpe, 1996)

12

2.2 | AR/MR/VR – from a lab to media culture

From media culture to Interaction Design?

AR and MR technologies developed from being a lab technology only available for computing community until becoming a natural part of current media culture. During this evolution, the focus of researchers broadened from plainly technological aspects towards a broad range of experiences that this technology can offer.

According to the literature, both VR and AR technologies originated in the late 60s, with the work of Ivan Sutherald and his invention of a head-mounted display. (Cipresso et al., 2018; Rouse et al., 2015; Sutherland, 1968) However, the ideas of alternative reality were introduced much earlier in science fiction. And the similar result was first presented in the 1950s by Morton Heilig. His immersive, multi-sensory machine Sensorama included wind and scent production, vibratory sensation, and 3D display.

AR and MR technologies have been recognized as an alternative to VR only in the early 90s, but, according to Rouse et al. (2015) media artists since the 60s were experimenting with artifacts and installations “that could be considered forerunners of MR” (p. 175).

Before-smartphone definitions. Milgram-Azuma approach

Frequently cited classification of AR and MR was published by Milgram and Kishino in 1994. Authors portray MR as a general term for virtuality continuum (Figure 3) – between VR and the unmediated real environment. Milgram states that AR belongs to the virtuality continuum and applies to all cases in which the real environment is augmented by virtual objects. VR in this spectrum represents completely immersive virtual environments. (Milgram & Kishino, 1994)

Figure 3. The linear mixed-reality spectrum by Milgram & Kishino (1994)

Azuma et al. (2001) follow Milgram in defining AR as a particular kind of MR. He describes that the AR system has the following properties:

• combines real and virtual objects in a real environment; • operates interactively, and in real-time;

• aligns real and virtual objects with each other.

Figure 2. Illustration of Heilig's Sensorama Figure 1. Head-mounted

display by Sutherald (Packer & Jordan, 2001)

13

Azuma argues that AR can potentially apply to all senses, including hearing, touch, and smell. (Azuma et al., 2001)

These definitions have served as a foundation for a research community for the last two decades. Several authors have offered revisions of Milgram and Azuma definitions. (Billinghurst et al., 2015) They offered their diagrams to replace or supplement Milgram’s (Rekinoto Nagao 1995; Mann 2002; Smart et al 2007). Still, these authors operate within the same framework: explorations are focused on the display itself and a user is understood as a receiving subject. (Barba et al., 2012; Rouse et al., 2015)

Barba & MacIntyre (2011) argue that this conclusion positions AR as a subgroup of MR, and not a separate discipline. And as a result, it consists of the same principles and expectations, and mainly relies on the visual display.

Mackay (1998) offers an alternative point of view, inspired by the evolving concept of ubiquitous computing. She writes that the most innovative aspect of AR is "not the technology: it is the objective" (p. 20). Instead of replacing physical objects with a computer, she suggests creating ways "that allow people to interact with the real world in natural ways and at the same time, benefit from enhanced capabilities from the computer". The vision of the future is as the "familiar world, enhanced in numerous, often invisible ways.” (Mackay, 1998, p. 20)

Barba et al. (2012) note that despite specialists' visions, technologies evolved according to a different scenario. Instead of "head-worn displays, gloves, and other sensors to enter virtual worlds [...] the sensing apparatus and computing power have been compressed into the smartphone". (Barba et al., 2012, p. 931)

Smartphone era: Barba-MacIntyre approach

Transformations in the field

The major changes during the last two decades are that we moved from specially build technologies for AR and MR to the smartphone ecosystem. Despite scientists' expectations, instead of "head-worn displays, gloves, and other sensors to enter virtual worlds" all the technologies have been "compressed into the smartphone". (Barba et al., 2012, p. 931) Thanks to this " users can not only see this advanced technology, but also they can hold it, use it, experiment and develop with it, and experience it for themselves". (Barba et al., 2012, p. 935) Authors suggest analysing its direction and influence it towards constructive goals.

However, Milgram's and Azuma's technical definitions were developed before the smartphone era, when AR was an experimental technology. Barba & MacIntyre (2011) argue that this concept of AR and MR is not capturing the experiential aspect of AR and MR when they move beyond the lab to the real world and become a part of our everyday media culture. (Barba et al., 2012; Barba & MacIntyre, 2011) Researchers argue that in the current era of the smartphone ecosystem MR research can go beyond the older technology-based concept.

Milgram-Kashiro's description is based on the opinion that all MR experiences are most importantly characterized by their method of display, which is usually visual (Barba et al., 2012; Rouse et al., 2015) Though, other researchers argue that MR experiences combine more "cognitive capacities" than just a visual perception. Including “representational and

14

symbolic processes associated with learning, memory, and meaning-making.” (Barba & MacIntyre, 2011, p. 118)

What do authors suggest?

Barba & MacIntyre (2011) note that recent technology evolution makes researchers redefine these display-centric conceptions. They do not deny the predominance of visuals but emphasize embodied elements, like orientation and motion, as a "control input" in MR experiences.

Overall, Barba-MacIntyre approach is focused on the user as a perceiving, experiencing, and meaning-making subject. Their characteristics are considering "different types of human experiences, either with or without technology, as part of the family of MR experiences". (Barba & MacIntyre, 2011, p. 118)

Authors suggest updating the understanding of AR and MR for the new paradigm of computing by:

1) Revising definitions – using elements of past definitions to formulate a version meeting the current state of the field.

2) Expanding the understanding of three fundamental MR components – vision, space, and technology.

3) Updating Montello's model of spatial scales to understand the visual, embodied, and spatial-temporal dimensions of MR experiences. (Barba & MacIntyre, 2011)

Definition

Barba et al. (2012) formulate the way to look at AR and MR in the age of the smartphone: • for a definition of MR – look to Mackay;

• for a definition of AR – to Azuma;

• to describe the relationship between them – to Milgram and Kishino.

Besides that, Barba & MacIntyre (2011) offer their own interpretation of MR, grounded in Azuma's definition: "Mixed Reality maps physical and virtual elements into a hybrid frame of reference that mediates interactions in time and space" (p. 120). They conclude that MR is characterized by having the following elements: mapped, embodied, spatial, temporal, framed. (Barba & MacIntyre, 2011)

Concepts

Barba & MacIntyre (2011) illustrate three core themes of MR research – vision, space, and technology. By vision is meant the predominance of the screens, by space is meant an arrangement of objects within the environment, and technology is standing for a device, which nowadays more often is a smartphone. Furthermore, Barba et al. (2012) suggest transforming vision to perception, space to place, and technologies to capabilities, to adopt and investigate MR experience in a smartphone ecosystem. Aditionally, Rouse et al., (2015) note that these categories provide a foundation for an experiential approach to MR.

15

Frames

Further, Barba & MacIntyre (2011) adopt Montello's (1993) model of spatial scales and propose a taxonomy of five frames to understand the visual, embodied, and spatial-temporal dimensions of AR and MR experiences.

According to Montello (1993), spatial scales are distinguished "on the basis of the projective size of the space relative to the human body, not its actual or apparent absolute size" (p. 315). He identified four scales and a fifth was proposed by Barba & MacIntyre (2011): • Figural space • Vista space • Environmental space • Geographical space • Panoramic space

The Figure 4 illustrates a model of five frames or spatial scales.

Barba & MacIntyre (2011) advocate for narrowing down a scale of vista till currently visible segment and adding a panoramic space, which stands for the area surrounding an observer – to experience it the subject must turn around.

MRx: defining the experience in MR

Based on Barba & Macintyre framework, Rouse et al. (2015) offer to extend the cognitive frames to also recognize the cultural and social dimensions of MR experiences. They provide a new term to highlight the focus on experience, formulate goals and primary qualities for this type of MR, suggest a diagram in complementing Milgram's spectrum, and finally, authors formulate three perspectives or lenses for exploring and examining the experiential aspect of MR.

Definition & goals

Rouse et al. (2015) introduce a term MRx to distinguish applications with a focus on experience from the more general class of MR. The x marks the value of user experience. Therefore, MRx applications intend to shift the focus from the mediating technology to the "quality of the experience they provide". (Rouse et al., 2015, p. 178)

Authors point out that forms of MRx are "designed to be engaging experiences, not primarily as tools for accomplishing tasks". (Rouse et al., 2015, p. 178). Further, researchers propose that MRx design goals could involve "entertainment, personal expression, informal education, or collective action" (p. 178). As a result, Engberg & Bolter (2015) conclude that “one key quality that distinguishes MRx from MR is an attention to the aesthetics of the experience” (p. 183).

16

Qualities

According to Rouse et al., three primary MRx qualities, distinguishing it from the more general class of MR, are:

• Hybrid

• Deeply locative and often site-specific • Aesthetic, performative, and/or social

Authors note that each of these qualities characterizes a subgroup of MR general MR features. However, MRx applications' purpose is to act for the interest of experience. (Rouse et al., 2015)

MRx aims to "reinterpret the space through digitally mediated interactions" (Rouse et al., 2015, p. 179), therefore its relation to the location is aesthetically or culturally significant to the experience. For example, it may "highlight the historical significance or personal meaning of the site". (Rouse et al., 2015, p. 179)

Diagram

Rouse et al. (2015) suggest a diagram that visualizes the MR and MRx applications (Figure 5). It aims to integrate the experiential dimension to Milgram's diagram.

17

Lenses

Rouse et al. (2015) suggest exploring MRx from three lenses (perspectives): media studies, performance studies, and design studies. Each lens brings its own perspective of understanding MRx. Therefore, from a media studies, MRx is perceived as a "new medium of representation and a new platform for inscription"; for performance studies – provides an innovative performative space; for design studies – creates a "new environment for collective and social interaction". (Rouse et al., 2015)

These lenses lead to three dimensions for articulating and examining the experiential aspect in MRx:

• Aesthetic dimension – the way in which "the experience engages or reconfigures the user’s perceptual relationship to the environment".

• Performative dimension – the way in which the experience brings the user into an interactive relationship with the environment

• Social dimension – the ability of the experience to get the user beyond individual outcomes and connect to others for achieving some mutual goals.

Rouse et al. (2015) conclude that as MR work starts to enter daily life, it becomes more important to recognize the historical, cultural, and aesthetic perspectives of this technology. Further, JafariNaimi (2015) suggests considering how MRx environments link with the economic, social, and cultural domains to serve the social needs and purposes. Moreover, it links with Barba et al. (2012) opinion that "when MR was in its infancy researchers were just trying to keep it alive and help it grow" (p. 935), however now, when it is becoming mainstream, we must try to influence its direction towards constructive goals.

Shortly about VR in IxD

Along with AR/MR technology, the experience of full immersion in a virtual world is also opening a wide range of opportunities for IxD. Design concepts, like embodiment and place, continue to be investigated by VR researchers. (Sutcliffe et al., 2019)

Kilteni et al. (2012) demonstrate that VR can be a tool to explore body perception within a virtual environment. Therefore, authors argue that VR has a unique advantage to expand factors linked with the embodied experience and achieve results that would be impossible in a physical reality. Moreover, in some studies, VR is allowing to approach "the multidimensionality of the embodied experience by inducing whole body illusions". (Kilteni et al., 2012, p. 374)

Regardless of the opportunities produced by a presence in a virtual environment, VR isolates the user from the real world. At the same time, AR and MR allow using a real-world setting for experience and exploration. Therefore, when aiming to encourage the user's engagement with a real environment, the design choice of AR/MR technologies is supported by the possibilities they provide.

18

2.3 | Design examples

Rising (2018)

4VR and AR experience by Marina Abramović

Figure 6. Rising by Marina Abramović.

Marina Abramović's Rising addresses the effects of climate change by bringing users to observe the rising sea level. As other Abramović's performances, Rising builds around time, the artist, and the public body. However, with Rising, the artist's presence is brought into another dimension, transmitting the presence of the artist virtually with VR and AR.

Using AR smartphone application or VR headset, viewers enter a virtual space coming face-to-face with the artist, who stands inside a glass tank that is slowly filling with water.

A user can choose to save her from drowning by supporting the environment, which lowers the water in the tank.

This design example shows how an artist may unfold the environmental topic and how VR and AR may be utilized to develop an emotional connection when addressing the human impact on the environment.

19

Infinite Scuba (2017)

5VR scuba diving experience by Cascade Game Foundry

Figure 7. Infinite Scubaby Cascade Game Foundry.

Infinite Scuba is a VR video game allowing users to experience scuba diving in real-world locations and interact with the underwater environment. It also has an edition Dive with Sylvia VR, where the user follows a famous oceanographer Sylvia Earle on a 5-minute tour of a real dive site in Belize with authentic wildlife.

This example demonstrates the application of VR, aiming to simulate the real-world experience. In this case, the underwater world is a place to explore, and VR technology is a tool, allowing a user to reach a remote environment.

20

Remote X | Rimini Protokoll (2013)

6An immersive performance by Stefan Kaegi and Rimini Apparat

Figure 8. Remote X byStefan Kaegi and Rimini Apparat.

In Remote X, a group of fifty people is guided through the city by a synthetic voice, wearing headphones. Creators argue that "the encounter with this artificial intelligence leads the group to perform an experiment on themselves". People are watching each other, making individual decisions, and yet continue being a group. Remote X questions artificial intelligence, big data, and predictability of people. It was taking place in various cities, and in each location, a new site-specific version was built upon the dramaturgy of the previous city.

This design example demonstrates the use of an audio narrative to transform a place and add another dimension to the familiar surrounding. Besides that, it shows how site-specificity contributes to the experience when utilizing or addressing particular details of the site.

21

Next to you at Korsvägen (2017)

7Mixed reality walk by Marika Hedemyr

Figure 9. Next to you at Korsvägen by Marika Hedemyr.8

Next to You is a private mixed-reality situation where the experience of the place and the passers-by is intensified. Participants are using a smartphone app and headphones, being free to choose a direction, which is crucial for the course of events. The artist argues that "a smartphone in your hand can open up new worlds and connections, and also create isolated bubbles and segmented societies". Exploring this aspect through an interactive walk, the artist remixes the vision of the city of Gothenburg with quotes from novels and facts about the place.

This design example demonstrates the artistic exploration of how AR technology can be used to add layers to the present environment, tell a story and create situations of critical reflection.

7Next to you at Korsvägen (2017) https://www.nexttoyou.art/ 8Photo: Marika Hedemyr

22

Parascope (2009)

9Public installation by Unsworn Industries

Figure 10. Parascope by Unsworn Industries.

Creators describe Parascope as a public viewer showing future panoramas based on citizen proposals. It is designed to help people imagine, compare, and discuss many potential futures. Parascope looks like traditional binoculars, but instead of showing a real environment, it uses AR technology to display visualizations of a possible future in a particular place.

Parascopes are used regularly in the city of Malmö, helping to imagine future daily life with fewer cars. Installations aim to engage citizens in a discussion on how to redesign the city to support other sorts of transport.

This example illustrates how AR could be used to open imagination about potential futures. Besides that, it demonstrates how AR may be experienced through various physical artefacts, rather than just a smartphone.

23

3 | METHODS and METHODOLOGY

3.1 | Literature reviews

Being an essential component of academic works, literature reviews are used in a design project to gather and synthesize research on a specific subject.

According to Martin & Hanington (2012) a literature review aims to extract data from various sources, using previous knowledge base for the current project. Authors suggest that the review should synthesize the information, finding connections between references while keeping the focus on the design project. According to Pan (2016) synthesis "is done by grouping various sources according to their similarities and differences" (p. 3). Additionally, Martin & Hanington (2012) suggest organizing the material by research categories, deconstructing complex topics to several key terms. Besides that, it may be organized chronologically, methodologically and thematically. Moreover, Pan (2016) points out that literature analysis may not always result in a singular conclusion but might involve reflection on how pieces of data fit together.

Martin & Hanington (2012) write that "the guiding factor in selecting literature for the review should be the relevance to the project, clearly suggesting how it informed or informs the design investigation" (p. 112). Besides that, the authors emphasize the importance of selecting the literature from credible sources. Therefore, literature reviews for design project may combine a wide variety of sources, but either way, they must be accurately referenced.

3.2 | Interviews

Martin & Hanington (2012) describe interviews as a primary research method to collect personal expertise, opinions, attitudes, and perceptions. There are different ways to specify the character of an interview – depending on the structure, target audience and amount of respondents.

An interview may follow a certain formal structure or have a flexible conversational format. In any case, it is recommended for the researcher to have a set of topics to address during an interview. Martin & Hanington (2012) argue that flexible interview format has the advantage of being more comfortable for a respondent, while the fixed script of questions may be seen as impersonal. Yet, an unstructured conversation mostly relies on the researcher guidance, while the structured set of questions is easier to control and analyse. In the literature, authors particularly address stakeholder, key informant and user experience interviews, as being part of the design process. (Kuniavsky, 2003; Martin & Hanington, 2012) According to Martin & Hanington (2012), a stakeholder interview is gathering information from people who may have an interest in the study. While key informant interview focuses on people who have professional or expert knowledge in a particular field.

The user experience interview is described by Kuniavsky (2003) as being more formal and standardized, requiring neutrality from an interviewer. Author remarks that these kinds of

24

interviews mostly follow the same structure, starting with general questions, then leading to more specific information and concluding with a summary of outcomes.

Martin & Hanington (2012) argue that paired or group interview may create a more natural environment for discussion. Though, the researcher should consider the potential influence of participants to each other. Moreover, the authors advise developing an interview around artefacts. Similarly, Sanders & Stappers (2012) argue that artefacts, pictures and open-ended materials may serve as a tool for inspiration and expression.

Among the common difficulties during interviews Kuniavsky (2003) names close-ended or directing question, inaccurate choice of words, asking people to predict the future, peers or authority pressure. Author notes that "the interpretation of answers also depends on the way questions are asked". (Kuniavsky, 2003, p. 126)

Kuniavsky (2003) recommends minding that people tend to avoid conflicts, may not always tell what they think or believe and may sometimes answer a different question from the one asked. Author notes that "the interpretation of answers also depends on the way questions are asked". (Kuniavsky, 2003, p. 126) I consider this when analysing expert interviews to make analysis less ambiguous.

3.3 | Observations

According to Martin & Hanington (2012) the observation is a fundamental research method, which requires "attentive looking and systematic recording of phenomena – Including people, artifacts, environments, events, behaviours and interactions" (p. 120).

Researchers emphasize the importance of observations since it provides additional information and context. (Kuniavsky, 2003; Sanders & Stappers, 2012) For example, Kuniavsky (2003) writes that people may not always share their opinion to avoid a conflict or because of trying to say what is expected. Additionally, Sanders & Stappers (2012) point out that observing people while performing a task may reveal the information a person is not sharing verbally.

Martin & Hanington (2012) suggest structuring observations, using existing frameworks. For example, AEIOU, which is an organizational framework helping the researcher to arrange and document information. AEIOU stands for Activities, Environments, Interactions, Objects, and Users. Finally, authors note that in any type of observations, it is useful to have an organizational framework in mind, to focus on relevant details.

3.4 | Mind Mapping

In the literature, mind mapping is described as a method of visually organising a problem space to develop a better understanding of complex topics. As a visual thinking tool, mind mapping can support idea generation and concept development when the connections between multiple elements are unclear. Moreover, it provides a nonlinear way of externalising the information, helping to combine, interpret, communicate, store, and retrieve information. (Martin & Hanington, 2012)

Martin & Hanington (2012) emphasise that the way of thinking is rarely linear, and complicated problems cannot be easily isolated from each other. Therefore, mind maps aim

25

to reveal a pattern of thoughts, allowing to summarise assumptions, make and break connections, and consider options while shaping the data into a concept.

To draw a mind map, the authors suggest the following several steps. First, identifying a focus question and concentrating on it. Second, drawing extensions, distinguishing primary connections. Third, revealing more profound levels of secondary information. Then, continuing to make free associations until all related pieces of data are pictured. And finally, trying to strengthen concepts and their interconnections to create new knowledge and understanding. (Martin & Hanington, 2012)

3.5 | Sketching and Prototyping

Sketching

Sketching is a fundamental part of the design process, especially in the early stages. According to Buxton (2011) , one of the essential aims of sketching in the ideation stage is "to provide a catalyst to stimulate new and different interpretations" (p. 115).

He argues that rapid and low-quality sketching can truly afford to play, explore, and learn because of the low investment into the process. While "too much concern for quality too early may well have a negative effect". (Buxton, 2011, p. 139)

Sketching process may include different materials – from pen and paper to digital tools, or physical modelling. However, "the importance of sketching is in the activity, not the resulting artifact (the sketch)". (Buxton, 2011, p. 135)

Sketches should be quick, inexpensive, disposable, use minimum details, they should suggest, explore rather than confirm, etc. Buxton emphasizes the importance of ambiguity, arguing that an essential element of sketches is the ability "to be interpreted in different ways". (Buxton, 2011, p. 113) Among other attributes, he also names that sketches should "suggest and explore rather than confirm". (Buxton, 2011, p. 113)

Buxton (2011) also notes that it is possible that sketches for experience and interaction design may differ from traditional sketching since they have to address different components of the user experience.

Prototyping

Martin & Hanington (2012, p. 138) describes prototyping as “a tangible creation of artifacts at various levels of resolution, for development and testing of ideas”. Houde & Hill (1997, p. 3) define a prototype as "any representation of a design idea, regardless of medium". Authors emphasize that regardless of tools and media used to create prototypes, the most important is "how they are used by a designer to explore or demonstrate some aspect of the future artifact". (Houde & Hill, 1997, p. 2)

Houde & Hill (1997) argue that a problem when speaking of prototypes in the HCI field is the complexity of interactive systems and lack of common vocabulary across disciplines.

Figure 11. A model of what prototypes prototype by Houde & Hill (1997).

26

They suggest that designers may focus the exploration on some particular features of a prototype. Authors suggest that by understanding what design questions should be answered, designers may define what kind of prototype to build. (Houde & Hill, 1997) Therefore, Houde & Hill (1997) propose the model to describe three important aspects of interactive artefacts. Authors define these three aspects as role, look and feel, and implementation (see Figure 11). Each dimension aims to answers a set of questions, for example:

Implementation usually requires a working system to be built; look and feel requires the concrete user experience to be simulated or actually created; role requires the context of the artifact’s use to be established. (Houde & Hill, 1997, p. 3)

3.6 | Storyboards

In the literature storyboards are described as "a visual narrative that generates empathy and communicates the context in which a technology or form factor will be used". (Martin & Hanington, 2012, p. 170) Storyboarding is used to visually represent the context of how, where, and why the user may engage with a product.

Martin & Hanington (2012) suggest using simple drawings, focusing the attention on a specific detail or message, however showing enough context. Researchers recommend using text to support the visuals and depict the passage of time when necessary. As well as presenting only one key idea behind each storyboard.

3.7 | GDPR statement

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is the privacy and security law of the European Union (EU), which imposes a number of obligations when collecting the personal data related to people in the EU. 10

Personal data is defined as "any information that relates to an individual who can be directly or indirectly identified", for example, names and email addresses as well as location information, ethnicity, gender, biometric data, religious beliefs and political opinions. Moreover, pseudonymous data also falls under the definition if a person may be identified from it.11

According to the GDPR "in order for processing to be lawful, personal data should be processed on the basis of the consent of the data subject concerned or some other legitimate basis"12. Therefore, consent is one of the legal bases that can be used to justify a

collection, handling, and storage of people's personal data.

10What is GDPR, the EU’s new data protection law? https://gdpr.eu/what-is-gdpr/ 11What are the GDPR consent requirements? https://gdpr.eu/what-is-gdpr/

27

3.8 | Project plan

Figure 12. Design process model.

The project plan is inspired by the Double Diamond model13. It consists of four main phases,

requiring convergent and divergent thinking. However, the design process is highly responsive to the findings, allowing the goal refinement after the first explorations.

Discover and Define

In order to gather knowledge about the current state of the field, I define a research focus and learn about existing design examples, I start exploratory research with literature reviews and technology explorations.

To obtain first-hand knowledge and personal expertise I conduct individual interviews with specialists from different fields. The information gathered on this stage leads to the refined goals and context changes.

13 Design Council. The Double Diamond: A universally accepted depiction of the design process.

https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/news-opinion/double-diamond-universally-accepted-depiction-design-process

28

To gather information about the new context, I use observations, structured according to AEIOU organizational framework.

I analyse insights from each method to frame opportunities for the design concept and identify key directions.

Develop and Deliver

From the early stages of the project, I use sketching for idea generation, documentation, and reflection. Sketches serve as a base and inspiration for prototype development.

In order to develop an interactive artefact, I use digital prototyping, keeping in mind Houde & Hill (1997) approach. During this stage, I consider the key findings from the exploratory phase – literature, interviews, and observations.

Testing of the prototype includes on-site testing with 3 students and online testing with 3 people with an expertise in environmental education and natural guiding.

Based on the feedback, the final corrections of the prototype are made. As well a direction for future improvement is defined.

4 | DESIGN PROCESS

4.1 | Discover

Interviews with experts

Outline

The initial intention for discovery was to investigate the application of AR in IxD. Also, to explore ways to use AR when addressing marine sustainability. Further matters that evolve – which factors to consider and how to approach the prototyping process while addressing marine sustainability. This phase started with literature reviews and followed with interviews.

Motivation

The motivation to use interviews on this phase was to obtain first-hand knowledge and personal expertise from specialists in different disciplines. The main goals may be divided into two groups:

• To get an understanding of the context, opinions, values and concerns of potential stakeholders. As well as to learn about factors to consider while addressing marine sustainability as an interaction designer.

• To get insights about work with AR technologies from the IxD perspective. Moreover, to discover potential opportunities of a multidisciplinary approach.

The method in details

29

• Marika Hedemyr – an artist and interaction designer, working across choreography and public art.

• Domenico Sgambati – an oceanographer in Marine Protected Area, marine biology instructor and coordinator of European voluntary project in the field of environmental protection.

• Varja Klosse – a lighting designer, working with theatre performances.

Interviews were performed by video call with a duration of 30-40 minutes. Transcriptions are available in the Appendix 1. Further, findings and refined goals are presented.

All participants have provided written consent to participate in this study and granted permission for the data generated from this interview to be used for the study purposes. All participants agreed that a brief synopsis could be included in the documentation of the study, including name, institution or organization and a brief bio. No sensitive data were collected.

A view from IxD

The main result of the interview with Marika Hedemyr was a review of previous assumptions about the outdoor use of AR. The assumption was that the outdoor use of AR is distracting a user from the place. Instead, Hedemyr described that her aim to work with AR is “to provide a tool that can make you see through the phone so you can experience a place”. (Appendix 1, p. 56-63)

A tool to focus the attention

The interview helped to reconsider the initial idea and understand that the use of AR on the specific location may, in contrast, be a tool to activate the place, focus the attention on some particular topic, helping to analyse and understand it. As well as be a tool opening the imagination on various interpretations of time, space, meanings, and narratives.

Hademyr said that “the smartphone and the headphones together can work as a tool to sensitise your body and core your attention to the actual location”.

Sensation of time

Another design takeaway was that AR experience can be an instrument helping to get the sensation of the place through time. “People often comment on that, on this oscillation of different times that they experience”.

Moreover, the conversation revealed that the timing and tempo of the narrative are essential for the experience. When being outdoors, the timing should be much shorter in comparison with the museum. “One minute is super long when you’re outdoors with a smartphone”. Hedemyr noted that in the museum “you can easily do a film for minutes. But that doesn’t work [outdoors], you might have to do 20 seconds “.

She also emphasised that the designer must evaluate timing and tempo according to the engagement, bodily sensation, and environment. “You really listen to that moment of like: oh, no, it’s too boring. In order to sense what does your body tell you about the tempo at the location.”

Role of the location

The environment around also impacts the use of narrative. The quiet natural locations may require slowing down the tempo.

30

Besides that, the location itself may provide a design context. For example, Hedemyr tells that conflicting narrative at the location determined a choice of the place during the previous project.

Inspiration from real objects

Hedemyr also explained the ideation process around real objects, like microphone, statoscope, binoculars, X-ray. Real instruments, “that allow us to see things that we might not see, or you might not pay attention unless someone pointed at it.” Later in the process, designers might recreate, evolve, or combine some features of these objects.

Artistic approach

The final and also a valuable insight from this interview was connected with the artistic approach. Hedemyr said: “as an artist, I really want to open imagination”. In contrast to the pedagogic approach, the artistic way strives to leave some things open for interpretation.

A view from oceanography and environmental education

The main intention of the interview with an oceanographer Domenico Sgambati was to learn about the context and values, which may help understanding what to consider while addressing marine sustainability as an interaction designer.

Bringing people outdoors

One of the main insights from this interview was the reasoning behind the outdoor environmental education, and the role technologies may play. Sgambati said: “The work that parks have to do is to bring people in contact with nature. Because it is the best way to understand it and feel it with emotions and with senses”. (Appendix 1, p. 63-67)

Sensory and emotional experience as a tool

He argued that environmental education techniques should contribute to sensory and experiential immersion in nature. Looking from the point of IxD, it linked with Dourish (2001) arguments about embodied interaction approach – presence and participatory status in the world. Sgambati suggested that direct contact with nature is necessary for a sensory and emotional experience. However, technologies could be beneficial for cognitive understanding. “The onsite experience is mandatory. Otherwise, you are just working with your understanding and not feelings”.

Further, he recommended that the best reason to use technologies could be when identifying the limit of natural resources. “Understanding the limits and then covering the limits with technology”. However, dealing with marine ecosystems creates limits. “Even if you can see [it], you can be just on the surface area; you cannot go in the open ocean in the deep sea”. Therefore, he suggested that technology can help to reveal something physically hidden under the surface.

Finding natural monuments

Another design takeaway was about outdoor guiding techniques. “We usually find some specific things that we call natural monuments. A natural monument is a tool that we use to explain the ecological equilibrium in this site.” Sgambati suggested making a map of interest points or natural monuments and “build a path that helps people to touch different areas and understand how the biodiversity is distributed in the area”.

31

Using specific facts or games

Besides that, to communicate environmental concepts in a limited amount of time, he recommended two ways. First is addressing some specific entertaining facts about animals or other organisms. “For people is it more interesting if you speak about hidden behaviours of animals, of algae”. And another way is “finding games that are making people involved in an activity, so they can lose their rationality for a while”.

Sgambati told about one of the techniques used in environmental education, called flow learning. It is a four-step technique described by Joseph Cornell (1989)14. It consists of

increasing enthusiasm, touching the topic, games and sharing the experience. Sgambati remarks that the result depends on the temperament of the audience and the age of people, because kids play games naturally, while “adults want to see big predators or something that is very powerful”.

Respecting values

The final insight was about the values of the field. This conversation revealed that as a designer, it is essential to have a sensitive approach and not try to compete with the goals and methods of the field. For example, when trying to replace the contact with nature by technology.

A view from scenography

The reasoning behind interviewing a light designer was to learn about the way to develop the visual narrative, especially when addressing an overly complicated topic of the marine ecosystem. Moreover, the study interest was to learn about techniques and effects that may contribute to the visual structure and support the narrative.

Developing a structure

The interview revealed that one of the critical moments when working with a narrative is developing a structure to provide the reasoning behind the design decisions. For instance, the use of certain techniques or effects may visually refer to a specific time or emotion. “Before the performance, I know which source of light and which light effect will be responsible for a certain character or emotional condition, or time. At some moment, there are 4 or 5 key elements. And in the future, I already know why one or another element is used in this part and why it cannot be used in another part.” (Appendix 1, p. 67-71)

The use of contrast

According to the interviewee, the transition between different scenes is a crucial moment, since the contrast between the scenes helps to focus the attention. “Everything highly depends on how things change [...] the contrast should be strong, so the moment of recognition would happen”. By the moment of recognition Klosse meant a moment of empathy. She explained that empathy may develop when a viewer (or a user) is self-identifying with a character or a topic. “You recognise and feel a certain emotion”.

Synchronising elements

One of the critical insights was the importance of synchronising all the elements of design. Klosse said: “It is important in which moment everything happens. You may have great

32

ingredients, but if they are not mixed or mixed badly, or have wrong transition timing – it will look quite different.”

Considering the state of a viewer

Furthermore, Klosse recommended considering the inner world or state of a viewer because it affects the experience and the ability to connect. She suggested that the experience could start “from the moment then a ticket has been bought” or be affected by the specific task or kind of notifications a person receives. “It depends on what you want to achieve. Based on that, you may develop some preparation before the start of the play.”

Refined goals

In summary, the interviews assisted in re-evaluating initial intentions and refining design goals:

• moving from technology to the experience it may provide • from indoor application to the outdoor location

• from separate AR objects to storytelling, where AR contributes to the narrative • from general application for learning to the interaction with the specific place.

4.2 | Define

Focus, Observations, Ideation

Focus

The refined goal required selection of specific outdoor location. Since the project targets a topic of marine sustainability and operates in the city of Malmo, the selection criteria included places on the seacoast in Malmo or its surroundings.

After the selection process, the choice stopped on the area near the Oresund bridge. Three main reasons were supporting the choice. First, it is a picturesque place where a remarkable human-made monument meets the sea. Second, the meaning of the Oresund bridge in a cultural, historical, and environmental context. Finally, it may serve as a clear indication of time: before and after the bridge. Further, the investigation followed by observations and ideation.

Observations near Oresund bridge

Motivation

Observations were made to get sense and understanding about the place, its visitors, environments. Moreover, to define opportunities of the place: interest points (places to stop) and objects at the location that could inspire the design process.

Method in details

The visit and observations of the area followed with location mapping. Findings were organised keeping in mind the AEIOU framework. As a result, visual location mapping was developed, and three interest points were defined.