Degree Thesis

HALMSTAD

Subject Teacher Education for Upper Secondary

School, Swedish and English, 300 credits

An Analysis of the way Grammar is

Presented in two Coursebooks for English

as a Second Language

A Qualitative Conceptual Analysis of Grammar in

Swedish Coursebooks for Teaching English

Independent Degree Project in

English, 15 credits

Acknowledgment

I wish to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor Veronica Brock. Without her guidance, endless support and patience, this essay would not be what it is today. I also want to thank her for always being there at any time and for whatever I needed. Lastly, I want to thank the rest of the faculty of the English section for their support throughout the years that I have studied at Halmstad University.

Abstract

This essay aims to investigate theoretically how two currently used coursebooks, What’s Up 9 and Solid Gold 1, in a local area of Southern Sweden, present (introduces and covers) grammar. The overall aim is to investigate how grammar is presented, using the present simple and the present continuous as examples. The findings are also mapped to teaching approaches, as well as SLA (Second Language Acquisition) research, to see what approaches are favoured for teaching grammar in the first decades of the 21st century. In order to investigate the course-books, a qualitative content analysis and conceptual analysis was chosen with the presentation of grammar mapped into different categories, by using concepts for teaching and approaches used in SLA. The results show that the two proposed coursebooks favoured a FoFs (Focus on Forms) approach for presenting grammar. Furthermore, the results show that grammar is pre-sented explicitly and, if the teachers use the structures proposed in the coursebook rigidly, they automatically follow a deductive teaching procedure. When using a FoFs, explicit instructions and taking a deductive teaching approach, it may be regarded as the coursebooks suggest a grammar-translation approach as well. However, when observing other exercises connected to the reading texts in the coursebooks, it was detected that both coursebooks favoured a text-based approach for teaching, where the learners are supposed to learn the structure of different texts. In doing so, the grammatical structures are learned subconsciously and implicitly, which indicates that grammar is, in general, taught implicitly in the coursebooks, but presented (intro-duced and covered) explicitly.

Keywords: grammar, grammar presentation, SLA research, explicit instructions, implicit in-structions, inductive teaching, deductive teaching, FoFs (Focus on Forms), FoF (Focus on Form), FoM (Focus on Meaning), grammar-translation approach, grammar exercises, text-based teaching.

Table of Contents

1. INTRODUCTION ...1

1.1. BACKGROUND ...1

1.2. SWEDISH COURSEBOOKS &CURRICULA ...4

1.3. THE AIM AND PURPOSE OF THIS ESSAY ...6

1.4. THE STRUCTURE OF THE ESSAY ...8

2. LITERATURE REVIEW ...9

2.1. THE NECESSITY OF GRAMMAR TEACHING ...9

2.2. APPROACHES TO TEACHING ENGLISH ... 10

2.2.1. Grammar-translation Approach ... 11

2.2.2. Behaviourism & Audiolingual Approach ... 12

2.2.3. Notional/Functional – Text-based Approach ... 13

2.2.4. The Communicative Approach... 15

2.2.5. Lexical Approach ... 16

2.2.6. Form-Focused Instructions ... 16

2.2.6.1. Explicit and Implicit Teaching ... 18

2.2.6.2. Inductive and Deductive teaching ... 19

2.3. RESEARCH IN COURSEBOOKS FOR TEACHING GRAMMAR... 20

2.3.1. Types of Tasks ... 21 3. METHOD ... 24 3.1. METHODOLOGY ... 24 3.2. MATERIAL ... 25 3.3. PROCEDURE ... 26 3.4. LIMITATIONS ... 27 3.5. ETHICAL CONSIDERATION ... 27

4. ANALYSIS & FINDINGS ... 28

4.1. WHAT’S UP 9... 28

4.1.1. The Present Simple and the Present Continuous in What’s Up 9 ... 30

4.1.2. Exercises to the Units in What’s Up 9... 33

4.2. SOLID GOLD 1 ... 34

4.2.2. Exercises to the Units in Solid Gold 1... 37

5. DISCUSSION ... 42

5.1. WHAT’S UP 9GRAMMAR PRESENTATION ... 42

5.2. SOLID GOLD 1GRAMMAR PRESENTATION ... 45

6. CONCLUSION & SUGGESTED FURTHER RESEARCH ... 48

REFERENCES ... 51

PRIMARY SOURCES ... 51

SECONDARY SOURCES ... 51

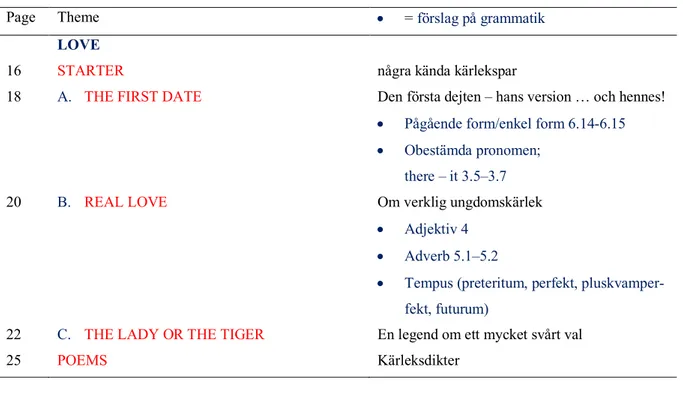

APPENDIX ONE: THEMES IN UNIT TWO FROM WHAT’S UP 9 ... 55

APPENDIX TWO: TEXT ‘THE FIRST DATE’ FROM WHAT’S UP 9 ... 56

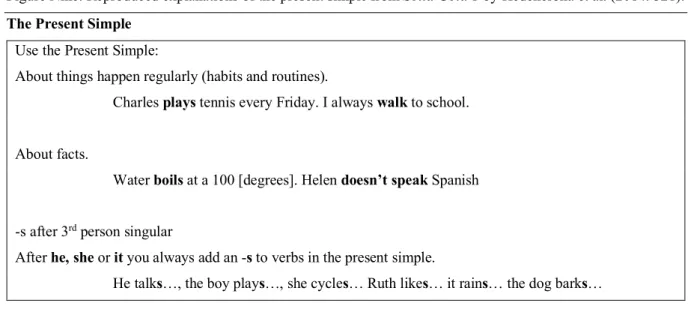

APPENDIX THREE: GRAMMAR EXPLANATIONS IN ENGLISH REPRODUCED FROM WHAT’S UP 9 ... 58

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

In Sweden, there is a requirement for all school students to learn English. It is one of the three main subjects together with Swedish and Math. Most students read Swedish as a first language and English as their second one. Therefore, any study of a Swedish school student’s journey towards becoming proficient in English falls within the field of SLA (Second Language Acqui-sition) research. Ellis (1997A: 3) defines SLA as the study of the acquisition of a language which is not the learner’s mother tongue. However, it is important to note that the word ‘second’ in SLA is a little confusing, as it does not mean exclusively the acquisition of a second language; it can be the acquisition of a third, fourth or even fifth language [ibid]. Equally confusing is the term ‘acquisition’ which can refer to both the acquisition of a language ‘picked up’ in a ‘natural’ setting, such as work and social interaction in daily contexts, or ‘learned’ in a ‘formal’ setting, such as a school (Krashen, 1981).

In SLA research, one area of interest is the exploration of how a person acquires their language through internal and external factors (Ellis 1997A: 3-4; Lightbown & Spada, 2013: 38-39). Typically, an external factor is associated with the effect of formal instruction on the learner, whereas factors such as previous knowledge, or a natural disposition for SLA are regarded as internal ones [ibid]. With regards to the influence of external factors on language acquisition, as Krashen (1981) points out, there is a difference between the way in which language is ac-quired, or picked up subconsciously in passing in daily contexts, and the way in which language is taught and consciously learned in more focused situations, such as the school classroom (Krashen, 1981; Ellis 1997A: 3-4; Lightbown & Spada, 2013: 38-39). As teaching English in Sweden at Upper Secondary (Years Seven to Nine) and Sixth Form level (Gymnasiet) falls within a formal or instructional setting, the exploration of what and how to teach in these formal settings is of high interest to a future teacher of English to speakers of other languages (ESOL). With regards to a formal or instructional setting of teaching English, the Curriculum in Sweden for teaching English as a second language states that the ‘[t]eaching of English should aim at helping students to develop knowledge of language and the surrounding world so that they have the ability, desire and confidence to use English in different situations and for different pur-poses’ (Skolverket, 2011B: n.pag). Additionally, the student should develop ‘[t]he ability to express oneself and communicate in English in speech and writing’ (Skolverket, 2011B: n.pag).

In Swedish schools, one of the overall aims of teaching English is to make sure that the learners become communicatively competent. Communicative competence can be defined as the gen-eral ability to express oneself through the use of language accurately, appropriately and with flexibility (Richards & Rodgers, 2001: 159-160; Yule: 2017). Yule (2017), as well as Richards and Rodgers (2001: 159-160), state that the first aspect of achieving an all-round communica-tive competence is gaining grammatical competence, which involves an accurate use of words and structures. Therefore, one way of developing communicative competence is to work with grammar in an instructional and formal setting.

If grammar is considered important for developing communicative competence, which is also stressed in the Swedish Curriculum for teaching English, it is of interest to discuss what exactly should be taught, as well as what methods and approaches should be used to teach it. But, firstly, what is grammar and why should it be taught? It is, sometimes, described as the rules and sys-tem of a language, although it is also argued that language actually does not have any rules at all (Hanfling, 1980). If the latter is the hypothesis, then any grammar input would be completely unnecessary. However, the hypothesis in this essay is that formal grammar input does have its benefits. Consequently, the next questions are what should be taught, when should it be taught and how should it be taught? Ellis (2006), for example, suggests that teachers should focus on teaching elements of grammar that can help rectify specific learner errors produced in each of the four communicative skills, where communicative skills are reading, listening, speaking and writing. In contrast, Celce-Murcia (2001: 263) stresses that as there is no definitive order that has been established for successfully teaching grammar, it is up to the teacher to decide what specific area of grammar should be taught and when.

The question of how grammar should be taught, and for what purpose has been and continues to be extensively discussed in language teaching research, as well as among teachers in the field. Because of the increasingly popularity of a communicative approach (see section 2.2.4.) for the teaching of second languages, in many cases, the role of grammar has declined in im-portance since the 1980s (Celce-Murcia 1991). For example, Wang (2010: 78) noted that when the communicative approach was introduced in China, a focus on the formal teaching of gram-mar was reduced. This means that, in many classrooms, the explicit teaching of grammatical structures may not be as noticeable as it once was.

However, to my mind, even though an explicit focus on the teaching of grammar has gradually become less popular, it still has its benefits. Firstly, it is a way of understanding how languages in general work, and, therefore, greatly assists in the further acquisition of language, be it a first or second one. Secondly, it can be used as a way of noticing the similarities and differences between the learner’s first language and the language they are learning. For example, if a learner knows what a verb is and what it means to inflect or conjugate one, it might facilitate not only the learning of a new language, but also develop a meta-language for talking about language itself. Thirdly, an awareness of grammar rules enables learners to communicate their messages more precisely. Lastly, a knowledge of grammar demonstrates to those with whom we com-municate that we are skilled in the use of language and are informed, which gives authority to what we say and write.

Therefore, the formal teaching of grammar seems to have many benefits, but in what ways should it be taught? Ellis (2006) stresses that teaching grammar to complete beginners of a language is not a necessity; it should be introduced once the learners have acquired some ability in how they use a language. Therefore, once the learners are mature enough to gain grammatical awareness, it should be reflected in the teaching. When Swedish students read English in school years seven to nine (upper secondary school) and gymnasiet (sixth form), they are definitely ready for grammar education as, in general, they are no longer complete beginners. However, Ellis (2006: 102) points out that ‘there is now a clear conviction that a traditional approach to teaching grammar based on explicit explanations and drill like practice is unlikely to result in the acquisition of the implicit knowledge needed for fluent and accurate communication’. If that is the case, then a traditional grammar-translation approach (see section 2.2.1.), which has tended to dominate the teaching of grammar, may be interpreted as inadequate (Harmer, 2015; Richards, 2015). It seems as it will not necessarily enable the learners to achieve communicative competence in English, if they have been taught predominately through such an approach. Therefore, the question is what approaches to the teaching of English grammar tend to be pro-moted in Swedish school in the first decades of the 21st century?

One way of answering the questions is to explore the content of different coursebooks used for teaching English as a second language in Swedish schools, and, more specifically, to explore the content that relates to the teaching of grammar.

1.2.

Swedish Coursebooks & Curricula

The important question is what approaches for teaching English grammar are promoted in coursebooks written for use in Swedish schools? More specifically, what seems to be the ap-proach(es) favoured for teaching English grammar for school years Seven to Nine and Gymna-siet? In what ways is it presented in the coursebooks? Is it presented explicitly or implicitly? Are there indications as to whether teachers should teach inductively or deductively? My overall hypothesis is that these four terms and concepts - explicitly, implicitly, inductively, deductively- are closely linked to each other, and are instrumental in the choices teachers have to constantly make when deciding if and how they teach English grammar in Swedish schools.

An overall aim of the Swedish National Curriculum for the study of English, in school years Seven to Nine, is to give the learners opportunities to express themselves and use different strategies for communication, in both speaking and writing (Skolverket, 2011A: 30). More specifically, the core content of English in the Swedish Curriculum states that the learners should be exposed to different language phenomena, in order to vary, and enrich communica-tion, such as pronunciacommunica-tion, intonacommunica-tion, fixed expressions, grammatical structures and clause elements (Skolverket, 2011A: 33). However, although Skolverket recommends the formal teaching of grammar, it does not explicitly spell out what specific areas the learners should be exposed to. Neither does it provide any guidance for which methods should be used for the teaching of grammar. As noted earlier, in order to express oneself as accurately as possible without vagueness and ambiguity, learning grammar can be regarded as a way of achieving those aims, and, consequently, achieve communicative competence. The Curriculum also pro-motes a text-based teaching, where students are supposed to learn about different text genres, spoken and written, and their different structural elements, which will result in learning gram-matical structures implicitly. This idea is closely associated with a functional approach to teaching (see section 2.2.3.).

In the Swedish Curriculum for English Five (1st year of gymnasiet), the aim of the subject is, in

general, similar to the Curriculum for Years Seven to Nine. However, when it comes to working with grammar, the Curriculum merely states that the learners should be allowed to learn how words and phrases, in writing and speaking, create structure and coherence (Skolverket, 2011B: 55). Additionally, in English Five, Skolverket (2011B: 55) states that the learners should ex-press themselves with variation and complexity. To my mind, this would be impossible without a formal knowledge of grammar, and, therefore, it should constitute an important element in

the teaching of English. Estling Vannestål (2015: 19) also argues in favour of teaching gram-mar, as she is of the opinion that achieving communicative competence in English includes an ability to express oneself coherently and correctly in different situations, and for different pur-poses, which also is stressed in the Swedish Curriculum for teaching English. Insufficient gram-matical knowledge can lead to breakdowns in communication. Estling Vannestål’s opinions about the nature of communicative competence are similar to those of Yule (2017), as well as Richards and Rodgers (2001). Although the Swedish Curriculum for both English Five and Years Seven to Nine state that the teaching of grammar should be included at some stage, there is no indication or explanations for which methods or approaches a teacher should use in order to teach it. This means that teachers, themselves, have to decide which specific areas of gram-mar to focus on and when, which teaching methods to use, and, most importantly, when they should be used.

As noted earlier, in the Swedish Curriculum for English as a second language, there are no explicit requirements for what the learners are supposed to learn, regarding grammar. In con-trast, in England, the Curriculum for the study of English as a first language sets out detailed instructions and guidelines for what the learners are expected to learn. Of course, there is a significant difference between acquiring and learning a first and a second language. Neverthe-less, the Curricula can still be compared, as the English Curriculum points out ‘[t]he grammar of our first language is learnt naturally and implicitly through interactions with other speakers and from reading. Explicit knowledge of grammar is, however, very important, as it gives us more conscious control and choice in our language’ (GOV, 2014). Additionally, in England, the specific areas of grammar, which the students must learn at different levels, are provided for teachers, whereas in Sweden, it is left to the teachers themselves to interpret the Curricula, and decide what should be taught. Figure One below set outs the content that School Year Five (ages nine to ten) learners, in England, should be introduced to.

Figure One. Example of content taken From the English national Curriculum (GOV, 2020-11-10) for year five (ages nine to ten)

Year 5: Details of content to be introduced (statutory requirements)

Word Converting nouns or adjectives into verbs using suffixes [for example, ate; ise;

-ify]

Verb prefixes [for example, dis-, de-, mis-, over- and re-]

Sentence Relative clauses beginning with who, which, where, when, whose, that, or an omitted relative pronoun

Indicating degrees of possibility using adverbs [for example, perhaps, surely] or modal verbs [for example, might, should, will, must]

Text Devices to build cohesion within a paragraph [for example, then, after, that, this,

firstly]

Linking ideas across paragraphs using adverbials of time [for example, later], place [for example, nearly] and number [for example, secondly] or tense choices [for exam-ple, he had seen her before]

Punctuation Brackets, dashes or commas to indicate parenthesis Use of commas to clarify meaning or avoid ambiguity Terminology for

pu-pils

Modal verb, relative pronoun relative clause

parenthesis, bracket, dash cohesion, ambiguity

Conversely, when learning Swedish as a first language in Sweden, the only stage when the explicit teaching of grammar is a requirement is in Swedish Two (2nd year Swedish at

gymna-siet). Skolverket (2011B: 170) explains that the leaners must learn the structure of the Swedish language: how words, phrases, sentences and clauses are built, and how they are related to each other. In comparison to the detailed and specified content in the English Curriculum for English as a first language, the Swedish one is much more general. Thus, in teaching Swedish as a first language, the teacher still has to decide which specific areas of grammar to focus on, as they are not explicitly spelled out.

1.3. The aim and purpose of this essay

The aim of this essay is to explore the ways in which different coursebooks designed for the teaching of English in Swedish schools introduce and cover aspects of grammar. The aim is to explore how grammar, in general, is presented, using mainly the present simple and the present continuous as examples. In this essay, the term presentation is connected to not only the

introduction of grammar, but also how it is covered. My hypothesis is that most coursebooks still tend to promote a traditional grammar-translation approach (see section 2.2.1.), where spe-cific grammatical structures or forms are introduced explicitly, which, consequently, can dictate a deductive teaching approach, as Jeremy Harmer points out:

For many teachers, decisions about what to teach are heavily influenced by the coursebook they are using. Not only do coursebooks offer a syllabus that teachers are expected to follow, but, more importantly, they have strong suggestions about how the syllabus should be taught. When the book has been chosen by the institution they work for, teachers often have little alternative but to follow its syllabuses and procedures […]. (2015: 71)

As the aim of the essay is to examine how grammar is presented in general, but as its scope does not allow for the exploration of every specific grammar point, it will be mostly limited to an examination of the present simple and present continuous forms, as examples of the way in which grammar is presented. The reason for focusing on these two forms as examples is directly connected to one area of difficulty speakers of Scandinavian languages often experience, when learning English. For example, in Swedish, there is no inflection for a person or a number. Therefore, when using the present simple form, learners tend to miss the third person-s (Da-vidsen-Nielsen & Harder, 2001: 30). Moreover, Swedish does not have a continuous form, which, consequently, leads intermediate learners to overuse the continuous form (ibid.: 31). The essay will also be limited to analysing two different coursebooks currently used today in a local area in Southern Swedish, What’s Up 9 (2007) and Solid Gold 1 (2014). Accordingly, the following question is posed:

- In what way(s) is grammar, using the present simple and present continuous as examples, presented in the proposed coursebooks designed for the teaching of English for years Seven to Nine and Gymnasiet in Swedish schools?

As Harmer (2015: 71) notes, coursebooks offer a Curriculum and content to which the learners are to be exposed. An advantage of their use is that, as the Swedish Curriculum for English does not spell out what areas of grammar, and content the learners should be exposed to, course-books can aid teachers in their work. It is easier for them to design lessons, if they have a solid starting point to work from. Moreover, coursebooks are, usually, written and designed by teach-ers with a long experience of working in the field.

1.4. The Structure of the essay

The essay is divided into a ‘Literature Review’ in which the field of second language acquisi-tion, as well as different methods and approaches used for teaching grammar are presented. Next comes a method and methodology section, with step by step and detailed explanations of the procedure used, in order to investigate the research questions. This is followed by a presen-tation of the results and analysis of the ways in which grammar is presented in coursebooks for the teaching of English in years Seven to Nine and Gymnasiet, in Swedish schools. This leads to a discussion about the ways in which grammar has been introduced and covered in the ex-amined coursebooks. Finally, a conclusion summarises the research questions with suggestions for further research areas.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Necessity of Grammar Teaching

Some linguistics argue that in order to master a language proficiently, one must master all of its separate but overlapping language systems (such as its grammar, lexis, pragmatics, seman-tics, discourse, phonological systems) equally. Wang (2010: 78) explains that contemporary linguistics concur that a language consists of sounds, lexis and grammar, all of which influence each other and affect the language system as a whole. Despite this, Wang asserts that grammar is the aspect which is the most important factor, because it is through grammar that sounds and lexis gain their meaning (Wang, 2010). Chomsky (1965) goes further in his reasoning and ex-plains that grammar should be seen as its own theory of a language. If grammar is the most important factor in a language system, it may be interpreted as a necessity for language teach-ing.

Lobeck and Denham (2014: 4) asked several students to define ‘grammar’. In most cases, the students explained that grammar is connected to writing only. The discipline of grammar, in the students’ opinion, consists of teachers covering a wide range of rules, regarding punctua-tion, vocabulary and spelling, as well as working with other structural elements used in writing [ibid]. The students believed that grammar is prescriptive, i.e. connected to notions of what is correct and what is not, and that teachers are supposed to provide the students with a knowledge of accurate English. This view of English, as a way of using correct and incorrect English, has its roots in the seventeenth-century England, where speaking and writing correctly seemed to be a key to social success [ibid]. When rules are connected to notions of what is judged to be right and what is wrong, they are regarded as being prescriptive (ibid.: 5). The question of who decides what is correct and incorrect grammar then arises. Usually, it is an authority who de-cides what language to use and what is considered to be ‘correct’ English [ibid]. In a school situation, the teacher is seen as an authority of the correct use of English.

In contrast to a prescriptive approach to grammar, Lobeck and Denham (2014: 6) explain that descriptive grammars focus more on how the language is actually used in natural situations. Lobeck and Denham (2014: 6) write ‘[d]escriptive grammatical rules, the set of unconscious rules that allow you to produce and understand a language, differ from grammar rules you typ-ically learn in school […]’. Consequently, what is considered grammatical and ungrammatical

will most likely differ between the two approaches. However, if the aim is to give the students communicative skills for being able to speak English in daily and natural contexts, then the use of descriptive grammars should be employed for achieving that particular outcome.

Although there are formidable arguments in favour of learning and teaching grammar, there are also problems regarding which grammatical structures should be focused on, as well as the order in which they should be taught. Zhang (1999: 108) explains that language is an expressive form, which not only occurs in natural settings, but that it is also a spontaneous activity, and, therefore, a person cannot learn all the rules for specific contexts. That said, language is also a medium for creativity, which means that learners are able to employ a limited range of rules in order to create an unlimited range of language, as a way of expressing meaning (Yu, 2008: 110-111). In contrast, Woods (1988) stresses that, when it is claimed that someone understands a language, this is usually referred to as an ability to express oneself to a high enough standard, and an ability to produce the target language with satisfactory grammatical accuracy. As a re-sult, there are uncertainties as to what can be taught and what cannot in terms of acquiring a foreign language. However, in relation to this essay, the hypothesis is that there is an advantage in grammar teaching, but where the approaches used for it are ambiguous, and are certainly something teachers must reflect on, when he or she designs and teaches lessons.

This invites the question as to why it is important to teach grammar in the first place. According to Ellis (2006: 84), to teach grammar ‘involves any instructional technique that draws the learn-ers’ attention to some specific grammatical form in such a way that it helps them either to understand it metalinguistically and/or process it in comprehension and/or production so that they can internalize it’. However, what approach and what methods a teacher should use is not described in the Curriculum for English in Sweden and, therefore, it is up to the teacher to decide what procedures should be used in the teaching.

2.2. Approaches to Teaching English

In this section, the most common approaches to the teaching of English to speakers of other languages (TESOL) are discussed. Furthermore, the essay is also limited to explore these ap-proaches only. Each and every one of these apap-proaches may be dealt with more substantially considering the coursebooks, but the scope of this essay does not allow for such in depth

explorations. The aim is to introduce them here, because the hypothesis proposed in this essay is that many coursebooks tend to promote an approach to the teaching of grammar that resem-bles and draws on a traditional grammar-translation approach (see section 2.2.1.).

In order to be able to discuss different approaches for teaching, it has to be made clear what is meant by an approach, as well as a method, as they are not synonymous with each other (Harmer, 2015). There is a difference between different procedures teachers use and different set of theoretical ideas which are used to justify these procedures [ibid]. Harmer (2015: 54) defines an approach as ‘the theories about the nature of language and language learning. These provide the reasons for doing things in the classroom and the reason for the way they are done’. A method, on the other hand, is defined as ‘the practical classroom realisation of an approach’ (Harmer, 2015: 54). It is a way of bringing the approach to life in the classroom [ibid]. However, because this essay is limited to only theoretically investigating how a teacher might use a coursebook, the appropriate term to use is approach. Because this is a theoretical observation of how grammar is presented, it may be expanded into a further study, where observations are carried out of how teachers teach the grammar areas in the two proposed coursebooks and their reactions to the content. Although some concepts and ideas in this essay may well be interpreted as being a method rather than an approach, according to Harmer’s definitions, the terms ap-proach and method should be treated synonymously in this essay. Henceforth, an apap-proach is a coverall term used for teaching procedures, methods and techniques.

2.2.1. Grammar-translation Approach

When it comes to teaching a second language, one of the most traditional approaches used is called a grammar-translation approach (Harmer, 2015: 56; Yule, 2017: 212; Richards & Rodg-ers, 2001: 5-6). Traditionally, the focus is on encouraging the learner to read and write in the second language rather than to speak. It is taught by using vocabulary lists and grammar exer-cises, usually, connected to written texts, and without any particular connection to everyday language [ibid]. Although memorisation is encouraged, memorising language and sets of rules does not necessarily help students to talk and discuss English in everyday contexts (Richards & Rodgers, 2001: 5-6). Unfortunately, when teachers use this approach, students can often leave class with high grades, but find themselves rather helpless when they try to communicate in natural contexts, since the teaching has not prepared them for those kind of conversations [ibid]. Harmer (2015: 56) notes that a grammar-translation approach typically introduces learn-ers to specific points of grammar, followed by a series of example practice sentences in which

the grammar area is illustrated. A grammar-translation approach usually employs exercises where the learners translate sentences between the L1 (first language) and the L2 (second lan-guage) [ibid]. There are some crucial areas to reflect on regarding this approach. Firstly, the language is only worked on at a sentence level, where studies of longer texts are excluded, especially at the early stages [ibid]. Secondly, there is less focus on spoken language, if any and, lastly, accuracy is encouraged and seen as a necessity in order to master a language [ibid]. Since there is a focus on accuracy, a grammar-translation approach may be interpreted as being concerned with notions of prescriptivism. Thus, if a grammar-translation approach is taken, linguistic items such as ’the present continuous’ are typically presented one at a time and prac-tised in isolation. Errors are also frequently and explicitly corrected. The learners are often pressurised into writing in the TL (Target Language), rather than speaking, and they are en-couraged to do so correctly from the start. The learners’ mother tongue is most often used as the language of instruction (Harmer 2015: 55-56; Richards 2015: 60). The typical types of tasks used in a grammar-translation approach are what are called grammar exercises (see section 2.3.1).

2.2.2. Behaviourism & Audiolingual Approach

Another approach to acquiring a language is through the formation of good habits, which has links to the behaviourist approach, is referred to as an audiolingual approach (Harmer, 2015:45). The behaviourist approach has its roots in B F Skinner’s theory, where habits are believed to be acquired through conditioning; a famous experiment took place where a rat ob-served a light go on (a stimulus), and then, when going up to a bar and pressing it (response), was rewarded with food (reinforcement). Harmer (2015: 45) writes that ‘if this procedure is repeated often enough, the arrival of the food pellet as a reward reinforces the rat’s actions to such an extent that it will always press the bar when the lights comes on: it has learnt a new behaviour’.

It is this stimulus-response-reinforcement model that is of interest in the audiolingual approach to learning languages and which was influenced by the general adoption of the behaviourist approach to learning in the USA during the early 1920s and 1930s (Harmer, 2015: 56-57; Rich-ards 2015). In contrast to a grammar translation approach, audiolinguism encouraged a focus on the spoken language. As noted above, audiolingualism relies heavily on the stimulus-re-sponse-reinforcement model, where forming good habits seem to be the key to successfully acquiring and learning a language effectively [ibid]. The aim is to engender good habits by

repeating phrases and learning them by heart [ibid]. Substitution is also a key component in the building of different sentences, where the learners, in small steps, switch words in semi-fixed expressions, such as ‘there is a cup on the table’, and then use the word spoon instead of cup as the substitute, which then creates a new expression, such as ‘there is a spoon on the table’ [ibid]. They were also supposed to repeat these semi-fixed expressions after the teacher in chorus [ibid]. Through this rigid procedure, the learners were shielded from making mistakes. Unfor-tunately, much of audiolingual teaching remained on a sentence level, and developing a lan-guage used in daily-contexts was not commonly encouraged [ibid]. The emphasis was placed on correctness with a purpose of learning phrases and utterances accurately, which then was supported by positive reinforcement [ibid]. However, the question that still remains is whether the utterances, statements and phrases the learners have learnt are meaningful in daily contexts. Nevertheless, by using this approach, the learners should definitely have learned to use the utterances grammatically correct.

Translated to a classroom situation, it seems as if drilling and constant repetition, and revision of the content, are regarded to be the key to learning languages (Harmer, 2015: 45). As with the rat, it is all about learning a specific behaviour. Thus, a behaviourist approach is, traditionally, taught by drilling and revising the content thoroughly. For example, the learners are given a cue (stimulus), which they respond to; if the learners are successful, they are rewarded with the reinforcement, usually, positive feedback, such as encouraging comments [ibid].

2.2.3. Notional/Functional – Text-based Approach

A notional/functional approach focuses on how the language is used in daily contexts. Chomsky (in Burns, 2016: 87) claims that language acquisition involves language in use, an active pro-cess of drawing on innate rules to generate language production. Therefore, language teaching should be connected to working with exercises and tasks in which language is practised as naturally as possible. Encouraging learners to use the language communicatively rather than absorbing grammatical structures and rules is favoured in this approach [ibid]. Hymes (1971B: 278) compared communication with competence and argues that, if speakers are to use lan-guage effectively, grammatical knowledge should only be a complement to other kinds of knowledge, for example, the communicative setting. This means that the tasks and exercises should focus on language usage in natural contexts, where grammar teaching is only a comple-ment when it becomes necessary.

Originally, a functional approach was connected to a systemic functional approach, which can be ‘understood as a resource we use to create meaning’ (Richards, 2015: 87). It can also be used to ‘make use of a series of interrelated systems that users draw on each time they use language’ [ibid]. Texts (spoken and written) are in focus for the communication and such texts reflect the context in which they are used. As Harmer (1987: 4) noted, just because a learner knows the verb ‘to be’, this does not mean they can use it to introduce themselves. In a functional ap-proach, which draws on the field of pragmatics, it was argued that language is used to do things, to perform specific functions such as inviting, apologising, expressing likes and so on. As such, the language (formal and informal) for expressing each specific function was identified. An ability to request an item at the breakfast table might, for example, include having to learn a range of expressions from ‘Could you possibly pass me the butter, please’ to ‘Chuck us the butter’. A functional approach also draws on the work on speech acts, introduced by Oxford philosopher J. L. Austin, and further refined by J. R. Searle. A speech act presents not only information, but also an action at the same time (Searle, 2002). When using a speech act, a function is also identified in the utterance, such as apologising, promising or requesting etc [ibid]. For example, ‘I would like the salt please, could you please pass it to me’, not only is the phrase used for acquiring the salt, but also for requesting that someone pass it, information as well as a function. As a result, there was a focus, in a functional approach, on appropriacy of context and the suprasegmental elements of pronunciation such as stress, intonation and body language. The problem was that the language needed for performing functions is also made up of identifiable grammatical structures, which led to a realisation that learners would also need to learn about structures in order to perform functions.

Drawing on the work of Halliday (Richards 2015: 87), and a growing interest in the field of discourse analysis, a notional/functional approach gradually developed into text-based or genre-based teaching. In this approach, the focus lies on learning the construction and use of different text genres [ibid]. The teacher provides the learners with scaffolding for a range of text types, be they written or spoken, so that they can elaborate on their previous knowledge of these texts. In doing so, they eventually learn how these texts are created, and can use the lan-guage related to each text. Subconsciously, the learners acquire the grammar when they learn these structures of the different texts.

Not only has a text-based approach to teaching had a significant impact on both first and second language teaching in Australia and New Zealand, it has also influenced the Swedish Curriculum for teaching languages, Swedish and English (Richards, 2015: 87). Learners are required to cover a wide range of texts, and learn how these different texts are constructed and used. How-ever, a ‘text’ in this approach refers to ‘structured sequences of language that are used in spe-cific context and spespe-cific ways’ (Richards, 2015: 87). For example, when the learners are as-signed to write argumentative essays, they must find out the language used for that specific context, discover who the targeted reader of the text is, and adapt it to its purpose. Moreover, a ‘text’ in this approach does not necessarily have to be connected to written English, a telephone call to arrange appointments, as well as casual conversations should also be treated as ‘texts’ (Richards, 2015).

2.2.4. The Communicative Approach

For the past four decades at least, a communicative approach, which promotes language as a system for communication, has been gaining in popularity amongst teachers (Harmer, 2015: 57). However, as Harmer (2015: 57) points out, to teach communicatively means different things to different people. Although there is some disagreement between researchers as to the exact nature of the approach, most of them would argue that CLT (Communicative Language Teaching) has shifted the focus on structural grammar and vocabulary to a focus on what lan-guage is used for [ibid]. If the assumption is that lanlan-guage is communication, then the use of meaningful exercises, which generate communication increases [ibid]. The emphasis lies on using language in settings and situations which is as natural as possible. Richards (2015: 68) explains that the essence of teaching communicatively is that learners learn a language through using it for authentic communication. The approach should not be considered as merely con-sisting of descriptions of specific rules or descriptions of grammatical structures, but more about communicative language that occurs naturally [ibid]. In relation to the communicative approach, Hinkel and Fotos (2002) explain that English language learners will acquire different forms of the language naturally, if a communicative approach is used; it is believed that lan-guage can be acquired without any formal grammar input [ibid]. However, there still are ambi-guities as to if and how teachers should teach grammar when taking a communicative approach.

Tasks and exercises typically associated with teaching communicatively are information-gap activities (tasks that make the learners communicate with others in order to gather the new information they do not possess at the time of speaking), jigsaw activities (where the class is divided into groups, where the different groups have the necessary information for completing the tasks) and task-completion activities (puzzles, games, map-reading etc) (Richards, 2015: 71). The main purpose behind these tasks is for the learners to communicate in order to com-plete them.

2.2.5. Lexical Approach

A major question, which has been discussed thoroughly in SLA (Second Language Acquisi-tion), is whether grammar or vocabulary is the most important part of learning a language (Harmer, 2015: 62; Harwood, 2002: 1). In the 1990s, a lexical approach which is based on the assertion that ‘language consists not of traditional grammar and vocabulary but often multi-word prefabricated chunks’ grew in popularity (Lewis, 1997: 3). The focus of the approach is on learning lexical phrases, collocations, idioms and fixed and semi-fixed expressions, which are a significant part of a language (Harmer, 2015: 63). For example, a semi-fixed chunk such as ‘Hello, lovely to see you’ should be filled with a particular kind of slot filler. In this example, ‘lovely’ can be replaced with other positive adjectives, such as nice, wonderful etc. Native users of a language have literally thousands of these chunks available and, in a lexical approach, to learn as many of these chunks as possible is seen as the key to learning a language [ibid].

2.2.6. Form-Focused Instructions

In any teaching situation, instructional settings (the way in which content and topics are pre-sented in a lesson) are always visible, regardless if the approach is a traditional grammar trans-lation one, or more of a communicative one. Typically, in instructional settings, Form-Focused Instructions are often used. The term Form-Focused Instruction (FFI) is defined by Ellis (2001:2) as ‘any planned or incidental instructional activity that is intended to induce language learners to pay attention to linguistic form’. In short, teaching grammatical structures may be seen as an instructional setting. For example, to work with the 1st conditional, which is con-structed by using the subordinator ‘if’ followed by the ‘present simple’, and then the modal auxiliary ‘will/will not’ followed by a ‘verb’ in its ‘infinitive form’, such as ‘if the museums charge for entry, a lot of people will not be able to visit it’. The 1st conditional is known as the

likely or possible conditional (Foley & Hall, 2012: 165). To aim of using FFI is to pay attention to specific linguistic features, such as conditionals, the present simple, or the present continuous etc.

The concepts Focus-on-Form (FoF), Focus-on-Forms (FoFs) and FoM (Focus on Meaning), explicit and implicit learning as well as inductive and deductive teaching all are connected to Form-Focused instructions. Therefore, the following sections set out to exemplify these key concepts, as they will be used in structuring the analysis of the coursebooks for English used in Swedish school. Figure Two below also illustrates the relationship between the concepts. Figure Two: Relationship of Form-Focused instructions

Implicit FoM

Form-Focused instructions Inductive/Deductive

Explicit FoFs and FoF

As its name implies, FoFs focuses on the forms of language rather than the meaning. Conse-quently, learners are taught grammatical rules isolated from other content (Ellis, 2006). Some-times, the targeted grammar area is taught through a series of lessons, where the targeted area is focused on and isolated in a specific context only. This is, usually, done through the repeated drilling and memorization of the form and an emphasis on accuracy [ibid]. In doing so, the learners are, more or less, automatically exposed to a grammar-translation approach, which can be interpreted as lacking in providing the learners with useful English competencies in future daily situations. In general, it means that the learners are exposed to a specific area of grammar isolated in a particular context. Moreover, it seems as if the teacher is supposed to explicitly tell the learners what they are going to learn in this setting.

On the other hand, FoF (Focus on Form) tries to alternate between both implicit and explicit learning and advocates both approaches in interactions with each other (Ellis, 2006). The over-all aim is to focus on the meaning but, on some occasions, the focus shifts to the grammatical element within the context [ibid]. For example, if a text uses conditionals, the focus should switch from meaning into a focus on form instead such as by paying attention to a grammatical area that is used in a particular text. In doing so, the learners are shifting between meaning and form but, usually, this is conducted by explicitly telling the learners what they are doing (Ellis,

2016). As Long and Robinson (1998: 23) explain, FoF, ‘consists of an occasional shift of at-tention to linguistic code features – by the teacher or one or more students’. The use of FoF thereby enables the learners to pay attention to specific grammatical features and talk about them. Doughty and Williams (1998) also argue that FoF is more beneficial than FoFs, because of the cognitive process the learners are exposed to, since they switch between a focus on form and meaning. However, it seems that much research indicates that a combination of FoF and FoFs is most beneficial, especially if a teacher starts with FoFs, since it enables the learners to pay attention to one specific linguistic feature (Ellis, 2006).

The last approach in Form-Focused Instructions is FoM (Focus on Meaning). This approach is, mainly, connected to working with the meaning of language and not on the forms (Burgess & Etherington, 2002). Therefore, grammar may well be interpreted as a phenomenon that oc-curs implicitly. Grammar may be dealt with as it ococ-curs in the context, but that is not the overall aim. Ellis (2009: 17), however, writes that a FoM approach can pay ‘attention to linguistic form [which] arises naturally out of the way the tasks are performed’. However, the general aim is to focus on the meaning of language. Although the focus lies on meaning, tasks can still be designed in a way that exposes the learners to specific language features, if necessary. FoM has received negative critique, because some researchers claim that learning a language to some extent requires the learner to pay attention to structural elements in a language (Schmidt, 1994; 2001). In relation to explicit and implicit grammar learning, FoM is closely associated with implicit teaching, because language is treated as something that occurs naturally.

2.2.6.1. Explicit and Implicit Teaching

Hulstijn (in White, 2015: 48) refers to explicit learning as conscious knowledge, whereas im-plicit learning is unconscious knowledge. Ellis (2009) also explains that exim-plicit instructions and/or teaching involves that the learners, to some extent, are made aware of the language, which they are exposed to during a lesson, for example, grammatical areas. Ellis (2015: 19) also writes that ‘[l]anguage acquisition can be speeded by explicit instructions’. As explained, FoF as well as FoFs can be associated with explicit teaching, because the learners are made aware of the linguistic content of the lesson through explicit instructions. So, with regards to explicit instructions, and with coursebooks as an example, the rules and content should be writ-ten out for the learners. For example, if the chapter headline says ‘present continuous’, followed by a description of the rule, and, lastly, example sentences, it should be interpreted as an explicit instruction.

In contrast, an implicit instruction and/or teaching aims at providing the learners with language rules without them being aware of it (Ellis, 2009). It would appear that an implicit approach focuses more on fluency of communication rather than the learning of strict rules. Ellis (2015: 6) writes ‘[…] the underlying fluent use of language is not grammar in the sense of abstract rules or structures, but it is rather a huge collection of memories of previously experienced utterances’. Consequently, the rules should be learnt subconsciously by doing exercises and tasks, and not explicitly explained to the learners. De Graaff and Housen (2009) argue that, when a teacher uses implicit teaching, all grammatical knowledge is learned when encouraging the learners to engage in authentic communicative activities.

In relation to teaching English, according to Norris and Ortega (2000), research shows that explicit teaching has been found to be slightly more effective than implicit teaching. However, research also indicates that a combination between the two might be the best alternative. As Ellis (2006: 102) points out, explicit grammatical knowledge might facilitate the learners’ newly acquired implicit knowledge.

2.2.6.2. Inductive and Deductive teaching

One of the still unresolved questions within language teaching and, with explicit grammar teaching in particular, concerns whether a teacher should use an inductive or deductive teaching approach (Nešić & Hamidović, 2015: 190). In a deductive approach, the learners are presented with explicit rules (regarding form, function and use) concerning a specific grammar point be-fore being encouraged to use it in context. On the other hand, Thornbury (1999: 54-55) explains that, when grammar is taught inductively, the learners are encouraged to explore different struc-tural and functional elements of grammar, and formulate the grammar rules by themselves. As they work through a series of exercises, they are encouraged to figure out the rule by noticing the form and function of the grammar point focused on, and the context in which it is typically used. However, it is the teacher who supports the students by guiding them through a series of exercises which are designed to allow them to discover where and how a certain grammar point is used. Hinkel and Fotos (2002) claim that the advantages of using an inductive teaching ap-proach are that the learners themselves are able to make an analysis of how different elements are connected to each other.

If a deductive approach is taken, according to Thornbury (1999: 54-55), three main principles tend to be followed. Firstly, the teacher provides the learners with a clear definition and expla-nation of a specific grammar area. Secondly, the teacher gives the learners examples of how the target grammar area is used, where the aim is to illustrate the most frequent usage of a certain grammar rule [ibid]. Lastly, the students themselves practise the grammar point by do-ing example sentences or exercises [ibid]. The advantages of a deductive approach are that it leaves little space for mistakes, since the application of rule is supported through multiple ex-ercises and examples (Nešić & Hamidović, 2015: 192). However, the one disadvantage is that the approach does not always prepare students for language use which occurs naturally [ibid]; the teacher may not be able to illustrate the specific grammar point in a context that might occur naturally.

Although a coursebook may provide explicit information about the grammar to be focused on, it is still important to remember that the choice of taking either an inductive and/or a deductive approach in the classroom is up to the teacher.

2.3. Research in Coursebooks for teaching grammar

In their analysis of nine different coursebooks used for teaching English language internation-ally, Nitta and Gardner (2005) discovered that the trend seemed to be that learners benefit from form focused tasks to improve their L2 (targeted language) accuracy. Despite noticeable differ-ences between the books, Nitta and Gardner (2005) noted that each one is based on a Presen-tation-Practice approach to the introduction and coverage of specific grammatical forms and structures [ibid]. This means that the coursebooks tend to begin with a presentation of the tar-geted area, followed by a series of mechanical pattern practice exercises such as, gap-filling, matching, completion and rewriting that encourage the learner to work with the specific gram-mar point in question. Ellis (1991) explains that the popularity of mechanical gramgram-mar practice is generally supported by the opinion that repeated practice leads to proficiency.

Celce-Murcia (1991) noted that after an anti-grammar movement in the 1980’s, the role of teaching grammar gradually changed from a focus on habit formation to grammar awareness activities. There was a significant shift between how teachers teach grammar to how learners learn grammar. However, as Ellis (1991) noted, there is a belief that mechanical practice leads

to proficiency, another belief is that practice does not necessarily contribute to the ability to apply and use the structure of the target grammar area accurately and appropriately [ibid]. Therefore, Ellis (1991) stresses that pattern practice should be replaced with consciousness-raising (C-R) tasks. Ellis (1997B: 160) defines grammar consciousness-consciousness-raising tasks as ‘a ped-agogic activity where the learners are provided with L2 data in some form and required to perform some operation on or with it, the purpose of which is to arrive at an explicit under-standing of some linguistic properties of the target language’. More specifically, C-R tasks en-gage the learners in thinking and communicating about language in order to understand the targeted structures. Although Ellis promotes R tasks, Hopkins and Nettle (1994) surmised C-R tasks could be problematic on two counts. Firstly, replacing practice activities with C-C-R tasks only does not necessarily meet the practical demands in different teaching situations; for exam-ple, they may not meet the learners’ expectations about teaching. Secondly, C-R task ap-proaches are often already used in classrooms.

Nitta and Gardner’s (2005) findings from their analysis of the nine different coursebooks used for ELT (English Language Teaching) were interesting considering the debate about C-R tasks. While recent SLA researchers still try to find evidence and provide arguments against practising tasks (tasks connected to working with grammar in consolation in specific contexts) in the first decades of the 21st century, the analysis showed that they are still frequently used in the

mate-rial. In each of the analysed coursebooks, a presentation stage was easily detected, followed by a practice stage, regardless if the learners learned the grammar rule explicitly or implicitly. Similarly, Ellis’ (2002) analysis of grammar teaching books also suggests that they are clearly characterised by explicit instructions, followed by practising the target structure. Nonetheless, Nitta and Gardner (2005) also discovered that the approaches to teaching grammar in the coursebooks do also provide a combination between C-R tasks and practising tasks. Thus, the learners are provided with opportunities to discuss the targeted structure, but they still have to practise the targeted structure.

2.3.1. Types of Tasks

There are different types of tasks that are commonly used in coursebooks, some are connected to C-R tasks, whereas others share closer relationship to a grammar-translation approach, for example grammar exercises. The term ‘tasks’ is a bit confusing here, as it may be interpreted as being an ‘exercise’, which is defined as ‘an action or actions intended to improve something

[…]’ (Cambridge English Dictionary, 2020). Usually, the terms ‘task’ and ‘exercise’ are not synonymous with each other. However, in this essay, henceforth, the terms ‘task’ and ‘exercise’ should be read synonymously, and will be used so as well.

Grammar consciousness raising tasks are defined by Ellis (1997B: 160), as noted earlier, as ‘a pedagogic activity where the learners are provided with L2 data in some form and required to perform some operation on or with it, the purpose of which is to arrive at an explicit under-standing of some linguistic properties of the target language’. To build an explicit knowledge of the target area, these exercises have a direct link to the grammar points. When the learners do these tasks, they, automatically, absorb the grammar rules (Nitta & Gardner, 2005). Thus, C-R tasks has many similarities to taking an inductive teaching approach.

Another type of C-R task is called interpretation tasks (Nitta & Gardner, 2005). Ellis (1997B) suggests that the main goals of such tasks are to help the learners identify a form-function map-ping. In the tasks the learners are provided with input that encourages them to notice the target area; and to compare similar items. Additionally, interpretation tasks usually include pictures as a way to present meaningful contrasts. In contrast to grammar consciousness-raising tasks, because there is a clear focus to match meaning with form, to use explicit knowledge about the target grammar area is not a necessity.

Focused communication tasks share a common feature with the types of tasks previously men-tioned in that the task draws the learners’ attention to problematic linguistic forms (Nitta & Gardner, 2005). However, in contrast to grammar C-R tasks and interpretation tasks, with fo-cused communication tasks, the targeted area is elicited during on-going communication (No-buyoshi & Ellis 1993). Here the learners are encouraged to produce the target grammar area. However, what these three types of tasks have in common is that they may be interpreted as taking an inductive approach towards teaching. They all encourage the learners to pay attention to the target grammar area by discussing or learning the rule by doing the different tasks. In contrast to C-R tasks such as the three types mentioned above, practising tasks focus more on consolidating the learning of grammatical knowledge. Ur (1988) suggests three different types of grammar practice: mechanical practice, meaningful practice and communicative prac-tice. Mechanical practice as well as meaningful practice are typically associated with grammar exercises, and more interestingly, commonly used in language classroom teaching. Grammar

exercises are characterised by rather emotionless effort, for example, tasks such as gap filling, matching, completion, and rewriting (Nitta & Gardner, 2005). Grammar exercises share a close relationship to taking a grammar-translation approach.

3. Method

In the current study, a qualitative content analysis was chosen, in order to analyse the way in which the teaching of grammar is presented (introduced and covered) in two different course-books, used in Swedish schools for teaching English as a second language. They are What’s Up 9 (2007), used in Year Nine, and Solid Gold 1 (2014), used in English Five (1st year at

gymna-siet). Even though the former coursebook was published in 2007, and the latter in 2014, they are both currently used in a number of schools in the local area in the South of Sweden where the study took place.

The aim of the study is to answer the research question: In what way(s) is grammar, using the present simple and present continuous as examples, presented in coursebooks designed for the teaching of English for Years Seven to Nine and Gymnasiet in Swedish schools? To do so, What’s Up 9 and Solid Gold 1 have been chosen as the primary literature for the analysis in this study. With regards to the presentation of the grammar, it should be interpreted as being both the introduction of grammar as well as how it is covered in the chosen coursebooks.

In this method section, the methodology, material as well as the analytical procedure are pre-sented.

3.1. Methodology

In order to carry out this study, a content analysis was chosen as the method for examining how grammar is presented in two coursebooks currently used in the local area in Southern Sweden, where the study took place, and to explore how they present any content that focuses on gram-mar. This study was further connected to a conceptual analysis. In general, a conceptual analysis focuses on a concept(s) chosen for examination and with quantifying the number of times the particular concept(s) occurs (Silverman, 1999). However, as this study begins with a hypothe-sis, which is closely connected to a targeted grammar area and the way it is presented, the aim is to take a qualitative approach rather than a quantitative one (Silverman, 1999). This means that rather than counting the number of times the targeted grammar areas occur, the focus is on examining when and how they are presented, in detail, from a qualitative perspective.

In order to examine the ways which elements of grammar, mainly the present simple and pre-sent continuous, examples are prepre-sented from a conceptual perspective, any elements discov-ered that focused on the teaching of grammar were mapped to the following concepts implicit teaching, explicit teaching, FoF (Focus on Form), FoFs (Focus on Forms), FoM (Focus on Meaning), a grammar-translation approach, as well as other approaches in SLA teaching, and different types of tasks, such as grammar exercises. Thus, the chosen concepts constitute an analytical framework for the mapping and categorisation of the way that grammar is focused on in the coursebooks.

3.2. Material

The coursebook What’s Up 9 consists of a textbook and a separate workbook. It was written and designed by Gustafsson, Österberg and Cowle (2007). The textbook is divided into differ-ent themed units, with each unit consisting of and based around at least three written texts (henceforth referred to as reading texts) connected to the theme, and which the learners are to read and comprehend. These reading texts can be factual or fictional. For example, the first text might be a humorous story, the second a realistic story, and the third a factual reading text. There is always a progression between the texts; the first text in a unit is supposed to be easier than the second. In the workbook, there are a series of exercise connected to each reading text. The exercises are designed for the learners to work with vocabulary, writing, speaking, phonet-ical features and, sometimes, grammar.

Solid Gold 1 is designed by Hedencrona, Smed-Gerdin and Watcyn-Jones (2014). This course-book does not have a separate workcourse-book, but includes all the exercises and reading texts in a single publication. First, it is divided into a text section, with nine ‘themed’ units. These themes cover living conditions, social issues and cultural features in the English-speaking world. After the ‘themed’ units, Solid Gold 1 is divided into four sections – resource, exercise, vocabulary bank and a grammar section. The resource section is designed to help the learners develop their English by doing exercises connected to the reading texts (both factual and fictional) and extend their communicative skills. The resource section is also linked to each unit, where the different exercises are presented chronologically to the reading texts as they appear in the units. The exercise section aims to help the learners practice vocabulary and discuss the topics presented in the reading texts. The vocabulary bank helps the learners expand their vocabulary further, and, lastly, the grammar section is designed to help the learners expand their grammar

knowledge. In the resource section for each unit, the writers of Solid Gold 1 explicitly state which area of grammar the learners can work with. For example, in Unit Four’s resource sec-tion, the focus is on the present simple and the present continuous forms. However, the grammar input is only included as a complement; only to be used if it is felt the learners need more work on the suggested area.

3.3. Procedure

In this study, more specifically for the presentation of grammar, in each coursebook, I identify different approaches to teaching grammar: inductive, deductive, explicit instructions, explicit instructions, FoF, FoFs and FoM, in relation to how the present simple and the present contin-uous forms have been presented. Moreover, different types of tasks are also identified in order to deepen the analysis and for comparison to previous research, in the field of teaching English grammar as a second language. The tasks of interest for this analysis are reproduced in figures to illustrate how the grammar is presented. The different approaches function as a coding device for categorising the presentation of grammar and types of related tasks. It may be interpreted as a framework used for the analysis of the coursebooks.

The first stage was to identify the occurrence of any specific areas in each coursebook that dealt with the present simple and the present continuous forms, which was the targeted grammar area. Having identified the areas, the next step was to examine how the grammar was intro-duced, by deciding if it was presented in an implicit or explicit manner. A further step was to examine the nature of any exercises related to the presentation of the target area in order to investigate how the learners were supposed to work with the grammar input, in this case the present simple and the present continuous forms. The content of the presentation and exercises were then mapped to the concepts of implicit, explicit, FoF, FoM, FoFs, as discussed in the ‘Literature Review’ section.

After that, I examined any reading texts, which were supposed to be connected to the targeted grammar area; the first two exercises in What’s Up 9 and the first three exercises in Solid Gold 1 connected to each reading text were then examined. The aim here was to identify the type of exercise the learners were supposed to work with, and mapped to the concepts of a grammar-translation approach and grammar exercises. As stated earlier, the hypothesis in this study is that the grammar presentation itself is associated with grammar-translation. However, when

analysing the proposed exercises connected to the reading text, where the present simple and present continuous were supposed to be used, any other approaches were noted and mapped to relevant concepts as well. In doing so, I was able to categorise the grammar presentation and different types of exercises. The same analytical procedure was carried out separately for each coursebook.

3.4. Limitations

The study is limited to a theoretical exploration of the proposed coursebooks. This means that the presentation of grammar in the coursebooks will be analysed from a theoretical aspect ac-cording to SLA (Second Language Acquisition) research, and different teaching approaches commonly used today in ELT (English Language Teaching). Furthermore, it is limited to the concepts and approaches presented in the ‘Literature Review’. It is, as always, possible to in-vestigate further in each and every one of the proposed concepts, for example ‘Prescriptivism’. That said, to observe the practical realisation of the coursebooks grammar input in a classroom situation is a suggestion for further studies with ethnographical observations in classrooms and interviews with teachers, both experienced and recently examined teachers, to highlight their reactions.

3.5. Ethical Consideration

As the study investigates two coursebooks used today, in a local area in Southern Sweden, some material will be reproduced directly from the coursebooks. Since I will reproduce some of the material, mainly descriptions/explanations and exercises, an ethical consideration would have been for me to have contacted the writers/publishers for their approval. However, as only a few pages have been reproduced in this study, and I make no claims of the qualities of the course-books, I chose not to do so. The aim is to highlight how grammar is presented with regards to SLA research and teaching approaches. Skolverket (2011A) also claims that teachers have the authority to copy 15 pages or up to 15 % of a coursebook in their teaching. Since I do not exceed this limitation, it may also be regarded as an argument for it not being a necessity for contacting the writers.