Communication for Development One-year Master Programme 15 credits

#vistårinteut initiative and solutions to

the collective action problem

A case study of the professional and voluntary network based

on Facebook as platform

Abstract

The aim of the study is to investigate how Facebook is used to facilitate and inspire collective action. This will be done through a case study of the Swedish network of volunteers and professionals #vistårinteut [We Will Not Stand It] (VSIU). Further the aim is to examine what it is that makes people convert their concerns on social change into collective action by mobilisation in the network. Because they are part of the same network, the participants are assumed to have aspects as identity, motive, and purpose in common and the perception of collective identity and interest will be part of the study. The method for data collection is internet-based using two steps; 1) web-based survey and; 2) focus groups investigated through Facebook. Furthermore a Coding Scheme will be used to analyse the results through the theoretic framework of Collective Action theory, and the four solution categories to the Collective Action problem; market category, community category, hierarchy category and contract category. Eleven solution groups are selected due to the potential of social media to influence the capacity of each solution.

The most noticeable solution category in the results from VSIU is Community with strong indications of both common knowledge and common values, contributing to a steady community building and collective action online and in the streets. Facebook contributes to the common identity and community building by providing availability to information and support within the group. Another significant characteristics of Facebook as platform for collective action is the breakdown of geographical, political and social barriers.

However Community solely is discovered to be insufficient to solve the collective action problem and demands for solutions from at least one other category.

Table of Content

Abstract ... 1

Table of Figures... 3

Table of tables ... 3

1. Introduction ... 4

1.1 Social media in Sweden... 5

1.2 Purpose and research questions ... 5

1.3 Conceptualizations ... 6

1.4 Communication for Development ... 6

1.5 Limitations... 7

1. Literature review ... 8

1.1 New media and social media ... 8

1.2 Social media and social protest ... 9

1.3 Alternative and activist media ... 10

2. Theory ... 11

2.1 Collective Action Theory ... 12

2.1.1 The market category ... 13

2.1.2 Community solutions... 15

2.1.3 Hierarchy solutions ... 16

2.1.4 Contract solutions ... 17

3. Method... 17

3.1 Method for data collection... 17

3.1.1 Internet Research Method ... 18

3.1.2 Web-based online survey ... 19

3.1.3 Online Focus group ... 20

3.1.4 Sample ... 20

3.2 Reliability and validity ... 21

3.3 Method for analysis ... 22

4. Analysis ... 23 4.1 Survey ... 23 4.2 Focus groups ... 25 4.3 Market solutions ... 29 4.4 Community solutions ... 31 4.5 Hierarchy solutions ... 33

4.6 Contract solutions ... 34

5. Conclusions ... 36

5.1 Reflections and future reserach ... 38

Bibliography ... 39

Searches ... 41

Appendices ... 43

A. Survey results ... 43

B. Interview guide focus groups 1 and 2 ... 46

C. Interview guide focus group 3: Administrators ... 48

D. Coding scheme for analysis ... 49

Table of Figures Figure 4.1 Obtrusive-unobtrusive dimensions in IMR (Hewson et al, 2016:36). ... 18

Table of tables

Table 3.1 Categories and solutions to the CA problem (Lichbach, 1994). ... 131. Introduction

During the end of 2015 the numbers of refugees applying for asylum in Europe increased, and in 2015 162 877 persons applied for asylum in Sweden, whereof 35 369 were unaccompanied minors1 (Migrationsverket, 2016). In the aftermath of this situation four women founded the network of professionals and volunteers today called #vistårinteut (VSIU) [We Will Not Stand It] as a reaction to the experiences they saw and lived.

Helena Lindros was working at a home for minors and explains how frustration and fear grew inside her. Then one day she saw a post at Facebook from Sara Edvardson Ehrnborg about how nobody meeting these unaccompanied children and sees their pain will stand the situation, finishing; “We will not stand it” (VSIU, 2018a). Lindros describes how something happened inside her when reading these words, feeling she was not the only one crying in her car on the way home from work. She contacted Edvardson Ehrnborg who was working as a coordinator for newly arrived minors and youth in school. Shortly after, in September 2016 they created a Facebook group for a hundred of people to share experiences and advices in their work for these young refugees. Together with Kinna Skoglund and Sissel Larberg, both social workers, they founded VSIU and the Facebook group grew faster than they imagined and in one month they were thousands (ibid).

Today the core of the network consist of over 10 000 professionals and volunteers coming in contact with unaccompanied young refugees, organized through several secret groups on Facebook (VSIU, 2018b). The movement demands;

“1. That the Swedish Migration Agency immediately freezes all deportations of all unaccompanied minors and youth due to the legal uncertainty and lack of knowledge of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) which currently is predominant at the Swedish Migration Agency

2. That our politicians grant a refugee amnesty giving asylum to all children and youth who have been in Sweden for more than a year

3. That the state and local governments immediately stop the relocation within Sweden of thousands of unaccompanied minors and youth during their asylum process as a mean to prevent more suicides in Sweden by young refugees” (VSIU, 2018c).

1“a person who is under the age of eighteen, unless, under the law applicable to the child, majority is, attained earlier and who is separated

from both parents and is not being cared for by an adult who by law or custom has responsibility to do so” (UNHCR,Guidelines on Policies and Procedures in dealing with Unaccompanied Children Seeking Asylum, February 1997 http://www.unhcr.org/3d4f91cf4.pdf) (accessed January 8th, 2018).

Currently their Facebook page “Vi står inte ut men vi slutar aldrig kämpa” [We will not stand it but we will never stop fighting] has over 74 000 followers (VSIU Facebook, 2018) which illustrates is the fast growing pace of VSIU, in numbers of followers and members going from 100 to 10 000 in less than two years.

As a member of the network, the researcher has followed the development and elaborated an interest to see what we can learn from the network regarding mobilization through social media. Even though much has been written on social media and social change (Meikle. G, 2006; Manyozo. L, 2012; Scott. M, 2014; Gerbaudo. P, 2012) Lewis et al. states “empirical studies of online activism are surprisingly scarce” (2014:1) and that too little attention has been paid to Facebook’s role in social mobilization (ibid). These statements do not stand without opposition from scholars arguing for digital activism as ‘slacktivism’, whereby “casual participants seek social change through lowcost activities (…), short on any useful action” (Shirky, 2011:6) which also have to be taken into consideration in this project.

1.1 Social media in Sweden

In the third quarter of 2017, Facebook alone had 2,072 billion of active users globally (have logged in to Facebook during the last 30 days) (Statista, 2017). According to

Internetstiftelsen i Sverige (IIS) the use of Internet in Sweden is 99 % in the age of 12-65

years. Even among the oldest group, 76 years or older, a majority (56%) uses Internet. However the older population do not use Internet at the same daily basis as the younger (2018:5-6). The daily social media usage of global internet users was 135 minutes in 2017, compared to 126 in 2016 (Statista, 2018a). In Sweden the average time spent on social media was estimated to 46 minutes a day in 2016 (2017 not available at the time) (ibid, 2018b). Of the Internet users in Sweden, 81 % say they use social media platforms at some time, and 56 % daily (IIS, 2018:36). Also social media keep growing in Sweden, and Facebook remains as the most used social media platform on 74 %, followed by Instagram (53 %), which enhance the relevance of Facebook for this study.

1.2 Purpose and research questions

The aim of this study is to investigate how Facebook can facilitate and inspire collective

action. Further the aim is to examine what it is that makes people convert their concerns on

To be consistent to the aim the study will depart from the following research questions (RQ): RQ1: What motivates and inspires members of VSIU to take collective action?

RQ2: What do the members define as the strengths of the network?

RQ3: How do the members of VSIU perceive Facebook as an advantage or/and disadvantage? RQ4: How can the mobilisation of VSIU be understood as solution groups of Collective Action Research Program?

1.3 Conceptualizations

Mobilization and collective action: In this study mobilization is understood and referred to

in wide terms and closely connected to the concept collective action introduced in chapter 4. Mobilization or collective action is to act together in any formal or informal aggrupation with the purpose to improve the impact of the actions, or increase the chances to achieve the purpose (Lichbach, 1994).

Social movement/network: The study does not focus on the difference between

aggrupation’s such as movements and networks, and use both concepts when referring to VSIU. There is no consensus on definition on social movements nor networks but Della Porta and Diani’s assumption that social movements and collective behaviour appears as “attempts by society to react to crisis situations through the development of shared beliefs on which to base new foundations for collective solidarity” (2006:7) is coherent with the perspective of this study, but not exclusive.

Social change/social protest: Social change is a process of societal development, and social

protest is an objection to the social situation. Consequently individual rebellions can become social protests and ultimately social movements and social protests is an expression of demands for social change (Castells, 2015:226-235)

1.4 Communication for Development

In general terms the focus of Communication for development (C4D) has been on “how communication can be used to advance the well-being, or interests of people, especially those who are politically or economically marginalized” (Deane in Wilkins et al, 2014:226). Nevertheless scholars, practitioners and organizations of the field have more recently tried to harmonise the various concepts of C4D with emphasis on finding a perception that replicates its significance in both developing and developed societies. Therefore many have chosen to use the term ‘communication for social change’ (C4S) to acknowledge issues of

empowerment, active citizenship and social change rather than development only as livelihood (Manyozo, 2012:7). This perception is in line with this study as it focuses on actors of the civil society advocating for social change. Thus it puts this study in the domain as it combines a focus on the connections between people in VSIU through communication on Facebook within a process of social change by raising awareness about injustices. Social movements and networks are an apparent component in an active civil society and learning more about how they use social media to interact and communicate will be important to better understand the characteristics and potential of digital activism to create social change.

1.5 Limitations

Due to the limited time and resources in disposition for the study, the purpose is not to examine the possible uses of Facebook for every single member, but rather focus on how Facebook affects the mobilisation and activism of the network using the perception of advantages and disadvantages. Neither do the study apply any gender analysis, considering this to be an important and demanding issue and more suitable for another study.

As a member of VSIU the researcher has elaborated trust and confidence to the network and the members. The engagement and membership in the network gives her access to information both about the network and the members, but also includes personal experiences, biases and predispositions. For that reason it is vital to reflect upon that to ensure high levels of objectivity and make those explicit wherever possible (Jootun et al, 2009). Her activity in VSIU before the research was focused on access to the information being shared. During the research she took a step back to avoid influence from other data not being part of the study (e.g. conversations and comments in the groups) and consequently took on a more passive role, even though her support to unaccompanied children and youth continued.

The analysis is not an exhaustive analysis of Collective Action Theory, but limited to selected parts of the theoretic framework. Additionally the focus of study is not on a media perspective and therefore do not include a pure media theory, but instead uses media as an intersectional theme and sees the technological interconnectedness both as a result of and a tool for the social interconnectedness in which social movements act to create social change (Castells, 2015).

1. Literature review

Several perspectives on previous research related to the study are presented to give a background to the field of study. New media and social media contextualize the focus on Facebook as a tool for CA and social change, social media and social protest is relevant understand the difference between social protest and social change. Finally alternative and

activist media explains further how movements and networks can and are using new media

and ICT’s.

1.1 New media and social media

Graham Meikle defines social media as “networked database platforms that combine public with personal communication”. However Meikle also points out that the technologies do not serve one purpose, but is both adopted and adapted to our ideas which always come first (2016:6).

To continue Leah A. Lievrouw uses four features to differentiate new media from mass media. She states that new media 1) are constantly changing, 2) has a networked architecture, 3) has a sense of so called “ubiquity” – the feeling that new media is present everywhere, all the time, affecting everyone where used, and 4) are fundamentally interactive (2011:8-14). This implies that new media generates opportunities for people to share and exchange experiences, discuss ideas and opinions, learn languages etcetera in a new pace. Besides, on a societal level social media creates exceptional opportunities for information flow, emotional expression, and social influence or advocacy (Lewis et al, 2014:1). Therefore the use of social media does not have a particular predetermined outcome. Additionally Clay Shirky argues that the main potential of social media is to be found in their support of civil society and social change, and therefore is better analysed in years and decades rather than weeks or months. Shirky also claims that “[a]ccess to information is far less important, politically, than access to conversation” (2011:1-4) and that the developing communication landscape gives people further “opportunities or abilities to engage in collective action” (ibid). This is relevant as it emphasises on the conversations going on inside movements and networks through Facebook, the space for relationships and connections to grow, in purpose of social change. However Alexandra Segerberg and W. Lance Bennett (2011) state that one of the main analytical misconceptions when discussing social media and controversial politics has been the tendency to separate social media from the broader technological and social contexts in

which they function, but also from its’ broader political context (ibid:198-199). This represent the complexity of social media and social change when doing research, but likewise brings light to the opportunities that may lie in these tools.

1.2 Social media and social protest

The research on social media and social protest has increased the last decade, especially regarding what has been called the ‘Twitter Revolution’ and the impact of social media in both national and global protests. In this context Alexandra Segerberg and W. Lance Bennet (2011) have studied how Twitter can have an impact on the result and spread of collective action. They suggest that although different protest ecologies or environments are expected to be different there are several measurements that can facilitate the analysis; the crosscutting networking mechanisms that Twitter streams represent.

Moreover Zeynep Tufekci and Christopher Wilson investigate the role of social media in the participation of political protest. From their study with people from the Tahrir Square they conclude that “social media in general, and Facebook in particular, provided new sources of information the regime could not easily control and were crucial in shaping how citizens made individual decisions about participating in protests” (2012:263). However their research focuses more on collective protest and expression of social discontent rather than collective action in purpose of social change (see distinction p.10).

Furthermore, Kristen Lovejoy and Gregory D. Saxton have studied the Twitter utilization practices of the 100 largest non-profit organizations (NGOs) in the United States, and get to the conclusion that “there are three key functions of microblogging updates—‘‘information,’’ ‘‘community,’’ and ‘‘action.’’” (2012:337). In conclusion they claim that NGOs use Twitter and other social media platforms as Facebook and Instagram more extensively and strategically than traditional media. In addition the use of new platforms “appears to have engendered new paradigms of public engagement” and the opportunity to mobilize people and build meaningful relationships (ibid:337-338). Consequently this study can contribute further by concentrating on how one specific group might use Facebook for mobilisation.

Seungahn Nah and Gregory D. Saxton claim the ability for an organization to adopt social media technologies presents considerable opportunities to create a more levelled playing field. However our understanding of this is scarce, and the researchers propose an explanatory model based on “strategy, capacity, governance and environment” to better understand the

practises of social media (ibid:295). The reason for this deficiency partly is due to a lack of research on e.g. Facebook on an organizational level. Nah and D. Saxton evaluate several specific concepts in their results and identify membership to be strongly related to a decreased volume of social media updates and reach of dialogue. Member organizations possess a more participatory structure with further defined emphasis on stakeholders. Moreover future research should focus on connecting social media outcomes to participatory organizational mechanisms and stakeholder targeting (2012).

1.3 Alternative and activist media

Today media audiences or consumers are to the same extent users and participants, involved in networks and communities etcetera. Under these circumstances many groups “have found new media to be inexpensive, powerful tools for challenging the givens of mainstream or popular culture” (Lievrouw, 2011:2).

Leah A. Lievrouw discusses the roots and characteristics of alternative and activist new media and proposes that “alternative/activist new media projects do not only reflect or critique mainstream media and culture, they constitute and intervene in them” (ibid:19). Further Lievrouw detects five genres of contemporary alternative/activist new media projects being; culture jamming, alternative computing, participatory journalism, mediated mobilization and commons knowledge (ibid:19-22).

Based on the categorization Lievrouw uses mediated mobilization as the term to address the use of new media “as the means to mobilize social movements – collective action in which people organize and work together as active participants in social change” across traditional boundaries and barriers of space, politics and identity (ibid:149-159). Moreover mobilization is considered the core concept of social movement theory and “what makes a movement a movement, the process in which people convert their collective concerns into collective

action to bring about change” (ibid:154). In this process capabilities inside the movement are

activated but also created and become resources. Further internet in mediated mobilization is used to share information and build solidarity, frequently in form of social media, virtual worlds or/and blogs.

Lievrouw sets off her research in New Social Movement (NSM) theory where movements are characterised of having a collective identity such as worldview, gender and experiences. Besides being loosely affiliated, informal, anti-hierarchical networks, decentralized, diverse,

and constant in reorganization. Additionally they are distinguished by their extensive and sophisticated uses of ICTs as the actual field of action and tend to extend over time and across geographic boundaries (ibid:41-58).

Therefore, in mediated mobilization as genre, mobilization is not simply the distribution and collection of resources but even creates a collective identity and a feeling of solidarity. In terms of time and intensity mediated mobilization has gone from an intensive to extensive form of organization (ibid:174-175).

2. Theory

To continue the theoretic framework of Collective Action (CA) Theory is described. Furthermore eleven solution groups to the CA problem are identified and discussed out of their connection to social media, besides their fusion with mediated mobilization because of its conformity to VSIU in terms of purpose, tools, character, form and concerns. The use of the solution categories is not complete; somewhat the solutions discussed are the ones that seem most applicable to position the theoretical understanding of CA in VSIU. In some cases social media may provide tools to the solution that facilities mobilization and in other cases it might be the solution that improves the impact of social media activity or strategy.

Moreover Lichbach sustain that existing applications of CA theories “have focused almost exclusively on certain initial concerns about nonparticipation in protest and rebellion” (1994:10). This leads us to the choice of case study as the starting point is that the CA problem and prisoner’s dilemma to some degree is manged and under control in VSIU, based on their growing numbers and activity in social media. That does not mean they are guaranteed success in their work, but they have thrived to mobilize people and convert their concerns on social change into action. The approach on social media and participation rather than non-participation will therefore bring an update on the relevance of the CA solutions to inspire mobilization and activism online as well as offline. Moreover CA theory and Lichbach offers a wide scheme on possibilities to explain why people join a group, which include both emotional reasons connected to community building or group identity and more rational or strategic reasons e.g. need of information or technical support. This variety is suitable because of the diversity in VSIU (p.23).

2.1 Collective Action Theory

CA theorists undertake the assumption that individuals are self-interested and strategic, especially when involved in conflicts or disagreements. From here appears the prisoner’s dilemma – “Everyone wants everyone else to voluntarily renounce the use of force and fraud, but everyone also wants to retain that right for himself” (Lichbach, 1998:413). In other words, only few people engage in CA because the big majority prefer someone else to get out and attend the protest and consequently attain the public good for them. This places actors with the problem of public good and free riding, as the desire for public good alone is insufficient to engage in CA. The consequence is that not enough people attend the protest or event and the public good remains unattained (Lichbach, 1998). This assumption on self-interest is questioned in this study by using a case study who appears to some degree have overcome the dilemma. Moreover the study refers to the aims of VSIU (see p.5) as a public good even though there might be other collective and/or individual purposes involved.

One of the mayor deductions and predictions of CA thinking is what Mark Lichbach calls the ‘five percent rule’ - that less than five percent of the supporters for a cause will engage in CA, an assumption valid 95 % of the time. This supports the obstructive nature of self-interest in the creation of mass movements and mass protest and hence CA is rather the exception than the rule (Lichbach, 1998:408).

In this study CA is interpreted in wide terms, associated to mobilization and social change. It is not in favour of neither Face-to-Face actions nor online activism, but focus on how the use of Facebook can facilitate the work in VSIU, in the streets or on Internet. Therefore this study wants to investigate if and how the use of Facebook plays a role in how VSIU solve the CA problem, by looking at the inspirations and motivations of the members and relate these to solutions of the CA problem. The actions of VSIU are considered to be collective due to the membership in the network and the common cause of VSIU. Even though individuals carry out actions in their private sphere, the network is assumed to have an impact on the engagement of the individuals in the lives and rights of the non-accompanied children and youth, and individual actions are then considered to be pieces of CA. Consequently no distinction is made between more private and collective actions, but the focus is VSIU as the compilation link between people and actions.

Lichbach identifies in his Collective Action Research Program (CARP) four solution categories through which to overcome the prisoner’s dilemma and expand mobilisation for the

public good. The categories are market, community, contract and hierarchy and it takes solutions from at least two categories to overcome a CA problem (Lichbach, 1998).

Through these four solutions Lichbach identifies 22 solutions to solve the CA problem presented in Table 3.1.

Solution Categories Solutions to resolve the CA problem

Market Increase benefits; Lower costs; Increase resources; Improve the productivity of tactics; Reduce the supply of the public good; Increase the probability of winning; Increase the probability of making a difference; Use incomplete information; Increase risk taking; Increase competition among enemies; Exit; Change the type of public good.

Community Common knowledge; Common Values

Hierarchy Locate agents and entrepreneurs; Locate principals and patrons; Reorganize; Increase competition among allies; Impose, monitor, and enforce agreements Contract Self-government; Tit-for-Tat agreements; Mutual exchange agreements.

Table 2.1 Categories and solutions to the CA problem (Lichbach, 1994).

Hereafter the eleven selected solutions are presented and related to social media. These solutions will contribute further on to understand different characteristics in CA in VSIU and help us answer the fourth research question foremost, but also provide a framework to discuss the three first questions.

2.1.1 The market category

The market solution category operates on the cost/benefits of participating in CA. Given the CA problem, market solutions look at how external or related variables can alter an individual’s decision to participate.

Increasing the benefits: The CA problem can be solved when individuals take action or participate because the benefits from their contribution outdo the costs of their actions. Thus the level of demand for the public good can help solve the CA problem (Lichbach, 1994). Social media can increase the perceived benefits of participating because of the instantaneous and multiple communications in tools such as Facebook, Instagram, Blogs, and WhatsApp which facilitates a bigger audience to communicate and organize fast. A perception of more friends, access to fast information, instant support and help are a couple of the benefits social media can facilitate to overcome the CA problem.

Lowering the costs: The costs of CA are particularly important to understand how and why people mobilise. Costs contribute to constrain the preferences and decision of the individual, and thus if costs are altered, the disposition to participate or not is adjusted (Lichbach, 1998). Internet and ICT’s do not only facilitate the communication inside movements, but also increases the opportunity to share their information with the rest of the world (or those in access to Internet), to a low cost. This opens up to reach new populations with the message, and vice versa. One example may be to share hashtags and widen campaigns to new users and inspire digital activism.

Increase resources: Increased resources will allow the activist to buy more of the public good (Lichbach, 1994:12). However resources can be in form of time, effort or energy, and belong to a group equally an individual. ICT’s, including social media can help to improve efficiency of resources as it offer online meetings through video calls instead of travelling, and to post video messages instead of send written emails. Obviously this can also lower costs, but more importantly the availability will improve and the activists have more time and energy for other tasks.

Improve the productivity of tactics: The CA problem can be solved if an individual’s effort and spent resources on attaining the collective good is comparatively more productive than this person would have to spend aiming for a private good. Because of this, any innovation or improvement in technology or tactics could increase the CA (Lichbach, 1994) and social media are itself both technology and tactics/strategy. One example is how people today can have online video-meetings to organize global campaigns, which save resources and time for every individual. Consequently tactics can improve the efficiency of social media, and vice versa.

Increase the belief in the probability of winning: Potential protesters and activists will take action if they are convinced that the CA will achieve the public good they pursue. The belief that CA can make a difference appears as a crucial to this solution (ibid:13) and social media has an enormous capacity to contribute to the spread of information which influences the perception of success and advances to the audience and the participants. Additionally it allows for people to participate and take action form far away by sharing posts, re-tweet, write comments, and coordinate the visibilization of the protest. However it is important to have in mind that this also works the other way around and witnessing repression can have a reverse effect on mobilization.

The probability of making a difference: This solution departs from the importance individuals place on their effort. CA problem occurs as individuals believe someone else will take care of the problem for them. The smaller the group is, the easier for an individual to measure or appreciate the importance of their actions (ibid).

However this is where we encounter the sceptics of digital activism, stating that simply sharing or liking a post can satisfy the feelings of contribution, and therefore lowers the probability of the individual to get involved in more time-requiring actions. Evgeny Morozov (2009) argues that such acts are low-cost and with low impact, and essentially meaningless, while creating a good feeling for the individual. Yet, it can also be considered that doing something, e.g. post a photo or re-tweet posts, is better than nothing. This is especially relevant in the light of research showing that sharing and dissemination of information do contribute to attract more attention and inspire mobilization (Barberá et al., 2015).

2.1.2 Community solutions

However the most likely solutions to social movements and social media belongs to the Community category as it emphasises how social media can alter how members of a community act collectively (Lichbach, 1998). This is based on the assumption that “[c]ommunal relationships beget the communal beliefs that beget communal action” (Lichbach, 1994:15). Through communication, activities, organization and coordination of individuals can be facilitated and furthermore nurture mutual expectations and aims. Because communication is essential to mobilisation, the Community category addresses the impact of communication directly.

Common knowledge: “One part of a communal belief system is common knowledge that overcomes mutual ignorance” (ibid). This solution claims that participants might share a common understanding that they will act together, and implies that individuals who see thigs similarly are more likely to act together. However this can be done as simultaneous or sequential action, which opens up for the participants to contribute at different times, when it suites them.

Social media can contribute because it facilitate communication concerning protest and social change which will assist in promoting the process as it prepares the activists and supporters for action. Besides, the spread of plans of action of some individuals will spur others to take action.

Common values: Individuals sharing the same values on how to act and can build the CA on the same knowledge and values, will consequently create a stronger collective identity. Potential activists will participate if they can see the costs as benefits, can attach a value of entertainment to the actions, or identify it as a self-reflecting political experience. The decision to participate can also be altered by a desire of the individual to express an ethical preference, fairness, and/or social incentives (ibid:15-16).

Consequently Facebook can increase the potential of common values since it facilitates community building and thus contributes to the development of a common identity. However violating these collective values and norms can have negative repercussions.

2.1.3 Hierarchy solutions

This solution category assumes a pre-existing organisation and then seeks more established processes to deal with issues related to the CA problem. This implies that the pre-existing organisation is the ‘visible’ hand that lower costs, increase efficacy, and provides resources. Because of the decentralised character of social media, its’ connection to hierarchy solution category might not be obvious, but the role of social media to movements and organizations depends on who is using it. The larger the size of the pre-existing organisation, the more likely its’ message will reach and cause interest to other audiences.

Finding and locating principals and patrons: The prisoner’s dilemma can be overcome if outsiders (could be participants or not yet participants) with great capacities for some reason can subsidize the costs of participation. As a guideline, Lichbach mentions how bigger national or international established organizations have contributed considerable to the efficacy of local civil rights demonstrations (1994:18).

Social media in this case offer great opportunities for publicity, and through shares, likes, tweets and retweets the word can be spread across boundaries and borders, and mobilize new audiences. It can even contribute to a distribution of power, and overcome boundaries.

Reorganization: This solution is actually composed by three separate solutions. The first is to form an exclusionary club and somewhat limit the membership. The second way is to create efficient subgroups that might be willing to support the cause. The last option is to create a federal group and somehow become decentralised, similar to how many protest organizations, but also terrorist groups, are composed of local groups. As mentioned above, it can be easier to solve the CA problem in a smaller group (Lichbach, 1994:18).

On one hand, social media provides platforms to reorganize and distribute the action, and allows for global movements and networks to create global sub-groups to exchange experiences and information, or coordinate global campaigns. On the other this also provides tools for “exclusive” groups where only those with access can participate.

2.1.4 Contract solutions

One of the issues activists can face is that they “act independently in an interdependent situation” (Lichbach, 1994:16). To overcome this difficulty, individuals can organize and govern themselves, reaching for the success of shared advantages. This is done without external assistance based on the idea that potential participants can self-manage and establish contract among them through collective norms (ibid).

Because the Internet serves as a new environment for connectivity, communication and action, we can see how norms and institutions are needed to govern behaviour online, but also to motivate CA.

Self-government: This solution is based on the creation of certain procedures to design, monitor and enforce rules inside a group to avoid opportunistic behaviour, cheating, and free riding (ibid:16-17).

Facebook among other social media include some kind of control in terms of behaviour and norms, not only for the platform to decide in their agreements with the users, but anyone registered can report posts, photos, accounts etcetera they perceive as not accurate or e.g. discriminative.

The accuracy of these categories and solutions will be further investigated and analysed through the case study in chapter 5.

3. Method

Further the method for data collection and analysis is presented and discussed in terms of advantages, disadvantages and including other possible options.

3.1 Method for data collection

The method for data collection of this research is divided in two parts. The first consist of a quantitative web-based survey, and the second part of qualitative interviews with focus groups

online. Additionally the terms for sample will be described and the choice of method is discussed to create transparency and candidness.

3.1.1 Internet Research Method

Internet-Mediated Research (IMR) methods are procedures to collect research data which

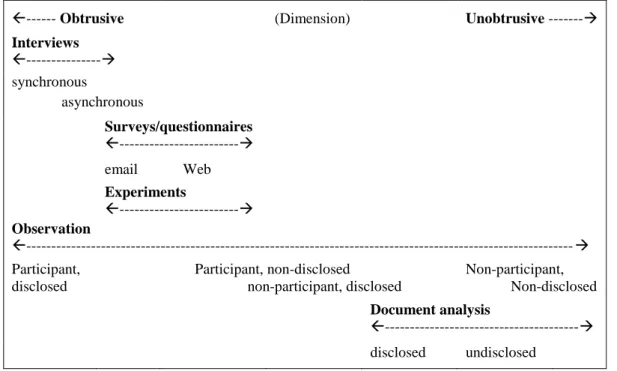

make use of the Internet. Hewson et al. present a framework to classify the most common forms of IMR methods, using an obtrusive-unobtrusive dimension (see Figure 4.1).

--- Obtrusive (Dimension) Unobtrusive ---

Interviews --- synchronous asynchronous Surveys/questionnaires --- email Web Experiments --- Observation --- Participant, disclosed Participant, non-disclosed non-participant, disclosed Non-participant, Non-disclosed Document analysis --- disclosed undisclosed

Figure 3.1 Obtrusive-unobtrusive dimensions in IMR (Hewson et al, 2016:36).

Consequently surveys/questionnaires, interviews and experiments are primary obtrusive methods, where the norm is to obtain valid consent from the participants before they participate in the research. However a method can be more or less obtrusive depending on the approach of the specific study. For example, asynchronous interviews (e.g. emails) are likely to be less obtrusive than synchronous interviews (e.g. online chats) because the participants can decide when to participate. Nonetheless it can be considered more obtrusive to use email directed to the inbox of the participants, than web-based methods published for the public. However, a couple of benefits of IMR approaches have been established, such as the elimination of geographical boundaries, facilitated access to otherwise hard-to-reach populations, cost and time efficiency, and possible improved reliability due to automated procedures. However these advantages are contrasted with challenges (ibid:38) of reduced levels of control and knowledge discussed further below. Lastly, because of the access to easy

and user-friendly software online, in combination with the tech-literacy of the sample due to their daily practices in the network the constraints related to technology are restricted.

3.1.2 Web-based online survey

In this study, survey method is used as a first step to generate a brief understanding and identify themes for qualitative research. The reason to choose web-based online survey is that VSIU already provides an adequate location to publish the survey in the main Facebook-group “Information” where one of the administrators publishes the survey to enhance credibility and increase the respondent rate (Hewson et al, 2016:38-46).

To avoid the risk of overwhelming data at this stage of the study, the survey consist of closed questions, made up by simple options, with a ‘other option’ with text field to each question and for final comments in the end. The disadvantages of closed questions e.g. forced answers and oversimplification of issues, were evaluated but disregarded because the purpose is to get general answers rather than details (ibid:3-8).

In the introduction the aim of the survey and the study is explained, as the terms of confidentiality and anonymity. After submitting the answers there is a last ‘de-brief’ page for further information about the study and provides contact information of the researcher.

Because of the general aim of the survey the demand for respondent rate is not stringent. However, to be able to make any conclusion a minimum of 100 respondents was calculated, which turned out at 227 respondents which after validation came down to 220. At the time of the publishing the survey the Facebook group had around 1050 members but there are no numbers on how many who saw the post. However the respondent rate of the 1050 members turned out 2,16% whereof 96,9 % were valid. The drop-out of 7 responses is due to double submissions, however the risk of further repeated submissions is not considered to affect the results significantly.

The survey depends on the chosen software, and in this case simplicity and flexibility has been prioritized to get a good overview. Other requirements are user-friendly for the participants, unlimited respondents and automatic collection of data. With a limited budget ‘Google Forms’ was the choice of software enabling all declared functions plus a wide choice of layouts.

3.1.3 Online Focus group

In comparison to other group interactions focus groups provide the researcher on greater levels of influence on what data to be produced. This provides efficiency in comparison to e.g. individual interviews which is more time consuming. Nevertheless this depends on the capacities of the researcher to assemble and direct the group, and the structure of the interviews (Morgan, 2012:6-13). A helpful appeal as researcher is to take the role of facilitator rather than leader during the interviews. However the focus groups in this research demanded an active leader to motivate activity in the groups.

Participation online can enable visual anonymity and consequently reduce inhibitions as social costs of disclosure are reduced. In this study the participants use their Facebook profiles and therefore can be identified by name and/or photo which might decrease the candour. However the sample in the focus groups is voluntarily and permits the participants to consider these circumstances before they assign to the interviews.

However, the biggest advantage of the IMR approach in this study is the possibility to include a geographic diversity with participants from more rural areas otherwise not accessible taken the researcher’s location in Stockholm. The asynchronous structure of the interviews was appropriate case because of the different schedules of availability of the participants depending on work hours and other commitments (Hewson et al, 2016:47-51). In addition, semi-structured interviews was applied to ensure certain data, but adapted and developed as the interviews proceeded and the researcher discovered new topics (see interview guides in Appendix B and).

In addition it would be interesting to use observation as method to collect data through chats, posts and comments from the Facebook groups of VSIU. However this would give more of an ethnographic character to the study and might be more appropriate for a smaller group to ensure candidness and confidence.

3.1.4 Sample

The focus groups are selected from the survey, based on experiences and accessibility of the participants. One group have previous experiences in social movements and networks, and a second group has no or little previous experience. The third group consist of three of the administrators responsible for the strategic work of VSIU and criteria do not apply to them as the sample was selected in dialogue to find the most suitable option. The results from the

administrators are indicated ‘admin, 2018’ as reference in the study. The participants from focus group 1 and 2 have been assigned the group number and a letter to maintain anonymity, e.g. 1C or 2A. Criteria Sample: focus group 1 Sample: focus group 2 Age 30-45:2, 46-60:2, 61<:1 30-45:1, 46-60:1, 61<:1

Sex 4 female, 1 male 4 female

Education level <3 years university:2, >3 years university:3

>3 years university:3, high school:1

Location Rural areas:2, smaller town:1,

medium-sized city:1, big city:1

Rural areas:1, smaller town:2, big city:1

Previous experience Yes, continuously: 4, Professional:1 No:4 Time on social media daily

in the engagement in VSIU

<30min:2, 3-4hs:2, >5hs:1 <30min:2, 1-2hs:1, >5hs:1

Table 3.1 Sample of participants in focus groups

However, the sample is volunteer and therefore not in complete control of the researcher. 40,9% (90 respondents) of the survey respondents answered ‘Yes’ to participate in the focus groups whereof three left no contact information. The three focus groups each consist of 3-5 people, taking place in separate Facebook groups at different times during March and April. Each group was open for discussion for about two weeks. One participant in focus group 2 accepted the invitation to the group but never participated in the discussions, so the final number of participant in focus group is three. However, the other three were considered to provide enough of data to continue and no measures were taken.

The sample for the focus groups can be considered as convenience sample based on availability and interest of the participants and can cause a lack of transferability (or external validity) in qualitative research. However, because the aim for the research is rather to study a specific group this is considered as a less big problem. However, there is also the risk that the participants are not representative for the group of study and the bias of the participants has to be kept in mind (Saumure & Given in Given, 2012:2). However the main reason for this convenience sample is the limited time in disposal and need to find participants interested to participate actively.

3.2 Reliability and validity

Reliability issues in IMR are often associated to the levels of control, which in comparison to more traditional methods is often reduced. To increase reliability of the web-based survey the pilot survey was tested in Firefox, Chrome and Safari to see consistency between different browsers. As ‘Google Forms’ do not provide any tool to exit the survey in a controlled way,

e.g. an ‘exit survey’ button, the survey instead was formulated to require answers to all the questions to provide submission in purpose to acquire complete answers (Hewson et al, 2016:144-150). Additionally the pilot survey was tested and consulted with the administrators to ensure it presented clear and unambiguous instructions, and the terminology adapted according to the practices and habits of the network in both survey and focus groups.

Moreover these instructions include number of questions, expected time to dedicate etcetera to keep the respondents from early dropout and maximise the data validity. The design of questions was decided to ‘check-boxes’ with only one answer allowed in purpose to avoid measurement error related to interpretations of the survey. In the same way instructions on the focus groups regarding aim, number of themes, and time-interval to answer was published before initiating the interviews to give the participants time to reflect and decide if participate or not.

Equally the instructions to the focus groups included information on proceedings and time interval to encourage participation (see Interview guide Appendix B).

3.3 Method for analysis

Because of the mixed character of the data collection on this study, a Coding Scheme was elaborated to combine the results of the two methods (see Appendix D, p.49). Its strength lies in the ability to combine quantitative and qualitative data even though the quantitative data is to serve mostly as a guide for the qualitative research.

However, in the coding process it is essential the categories or themes identified do not overlap. This means the themes need to be exclusive and unambiguous, but also comprehensive and concrete to avoid further problems with validity and reliability (Julien in Given, 2012:2-4). Where encountered difficulties to distinguish the categories a second categorization has been done and afterwards the two versions have been compared.

One of the strengths with a coding scheme is that the coding can be done simply with post- its, markers and papers. However it is a time-consuming process and one tool to handle this is the web-based survey where tendencies and themes can be withdrawn easily. As the interviews were in written format, the resources of time demanded to transcription were minimum and could instead be dedicated to the coding process. Additionally the categorizations of the results were done in Swedish, and only those parts relevant for the thesis were translated to English. Software packages can be used to facilitate the organization

of the coding, but it was not considered necessary in this case due to manageable amounts of data.

One issue related to the reliability of this method is the subjectivity of the researcher. One tool to improve the objectivity and the reliability is that more than one researcher interpret the data, in this case not possible due to structure of assignment.

4. Analysis

The results from the survey and focus groups are presented and analysed according to the eleven solutions to the CA problem presented in theoretic framework. Both survey results and interviews have been translated from Swedish to English and the original interviews are found in the appendices together with survey questions and interview guide. In conclusion all the eleven solutions can be identified in the data, with emphasis on the Community solution category. However all the solutions are intertwined and mutually supporting, and even stand in interdependence to solve the CA problem.

4.1 Survey

As mentioned in chapter 4 the purpose of the survey is to serve as an introduction to the focus groups and give a first brief image of the situation. The results from the survey (Appendix A.) first of all show a wide diversity in VSIU in terms of age, location and experiences. However 93,2 % identify themselves as female, and the numbers of educational level shows a big majority (85 %) have studied three years or more at the University (see Appendix A. p.43-44). Regarding location the division between bigger cities, medium-sized cities, smaller towns and rural areas is close to equal, with the majority (56,8 %) living in rural areas or smaller towns around Sweden. This diversity indicates participation across boundaries and barriers in VSIU in accordance with characteristics of NSM’s (Lievrouw, 2011) and is discussed further in the analysis as complementary data is needed.

On the question about the main purpose of the engagement in VSIU 39,7 % of the respondents answered “To get support and a feeling of solidarity” (see Appendix A p.44). In the comments section, one respondent pointed out that “The network is very important because I live alone and at the same time volunteer as family home”; a strong example of what the need of support and belonging can look like, and how social media can provide the access when it is not accessible in our physical surroundings (Lievrouw, 2011).

The strengths in this study are referred to in terms of perceptions of strengths, advantages and benefits. 41,8 % of the survey respondents answered they considered political advocacy as the primary strength of the network. The other three options; dissemination of information, expertise and support for the members all got similar numbers and 0,8 % replied ‘all options’ (Appendix A p.44). Additionally several other options were added, such as “helpfulness and heart”, “not feel alone in my frustration”, and “the visibility that we are many”. These numbers and quotes stand in contrast to the assumed self-interest in the creation of movements (Lichbach, 1998:408) as the respondents emphasize solidarity and support as their personal purpose (could be called a private good to compare with public good) but also as a strength of VSIU. To create support someone has to give it, and if it is considered as strength someone is giving it. Consequently the private good has become a public good we can argue. Likewise the awareness about the impact of the network was assumed to vary according to the specific engagement of each member. However the respondents in the survey emphasises political advocacy as a main purpose of both the network and personal engagement, arguing for a strong coherence between public and private good, and low degrees of self-interest. Worth mentioning is that 40,9 % of the survey respondents (see Appendix A p.45) answered they had no previous experience of engagement in social movements or networks, and additional 35,9 % answered Yes, but rarely or limited experience. However, this is chosen not to be further analysed by e.g. looking at correlation on previous experience and other data, mostly because of the limited time in disposal. In sum a big part of the member have no previous experience but for some reason chose by mobilize in VSIU, which brings focus to the concerns on participation instead of nonparticipation when studying CA as Lichbach argues (1994:10).

To continue, according to the survey, the main advantage of organizing on Facebook is the availability (38,8 %), followed by the visibility (34,7 %). These answers enhance the importance of the collective being visible as one big group. On the other side the importance of the availability is a complement to the expressed importance of constant access to support and information in the network (see Appendix A p.45). This ubiquity is characteristic of social media and appears to spill over to the network itself (Lievrouw, 2014). The importance of availability consequently brings relevance to the choice of Facebook as platform for VSIU, and inspires both information flows and emotional expression but also CA in form of advocacy and influence in agreement with Lewis et al. (2014:1).

However the disadvantages of Facebook were not investigated in the survey, but one respondent comments that “Facebook also have disadvantages: Difficult to get an overview, hard to find post you have seen earlier etcetera”. The disadvantages are further examined in the focus groups.

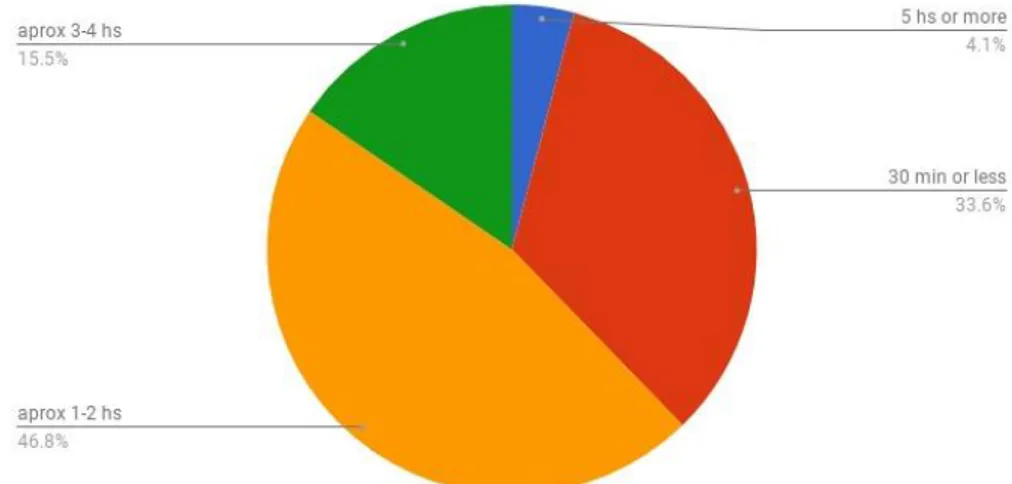

Furthermore another respondent comments; “I was more active last year, wrote to politicians and participated in demos. Now I’m burned-out”. When looking at the time people spend on social media only in their engagement we can see that 19,6 % spend 3 hours or more each day, whereof 4,1 % spends 5 hours or more (see Appendix A p.45). In comparison to the 135 minutes presented as daily social media usage of global internet by Statista (2018a) the members of VSIU can appear to be on average, with some exceptions. However because the question only regards time on social media associated with VSIU, it could be assumed that the total time when adding presence on social media for other purposes would end up above the average. Nonetheless it relates to Lichbach’s ‘five percent rule’ (1998:408) if we want to analyse who makes the most of the effort in VSIU. We cannot make a complete comparison because the data collection did not include that information, but the 4,1 % spending 5 hours or more on social media daily is very close to Lichbach’s 5 %. However the 4,1 % is far from alone as a big majority spends 1 hour or more daily in their involvement with VSIU. This analysis does not take into consideration the contribution from supporters of the cause not involved in VSIU and demands another perspective to investigate deeper.

Either way the results of the survey are not sufficient to answer the research questions and will now complemented with the focus group interviews.

4.2 Focus groups

Every respondent expresses its’ own particular back-ground and story to why and how they engaged and became member of VSIU. In common they have the connection to unaccompanied children and youth, no matter if it is in professional or more private context. The administrators make clear that “The network is open to all adults who meet young unaccompanied in their daily lives in their profession or non-profit / engagement / relationships” (admins, 2018). Furthermore no unaccompanied are members of the network, but some former unaccompanied who came as unaccompanied minors, but has been approved of asylum and are today adults (ibid). This common experience indicates a communal belief system and is a drive for CA according to Lichbach (1994:15).

To continue motional connections and meetings to unaccompanied children and youths is a returning theme as the main reason to get involved in VSIU. In all focus groups respondents express a feeling of ‘something had to be done’. 2C expresses how a coincidence made her convert her concerns on social change into CA by joining the network “I joined VSIU by a lucky coincidence - I do not work with unaccompanied minors - I'm an engineer - but had seen information occasionally about the situation and always thought it was terrible and "someone should do something".” As in the case of 1C, there is a tendency of ‘one thing lead to another’ in the answers regarding the development of the engagement in the network. 1B says that “I have always been engaged, but not like now. It feels very strong that I'm fighting for the lives of my youngsters. I've lived through many nights together with these anxious boys. I have no choice but must fight for them...”. 1B is explicit on the feeling of having no choice, and also expresses a need of a context, where more people feel like her, which she also refers to as one of the benefits. This ‘something has to be done’ mentality does not cohere with the prisoner’s dilemma in CA theory and might be one of the reasons why VSIU does not seem to be struggling with the CA problem. The members take action, sometimes first individually but at some point join VSIU because they see a need. To CA theory this means the benefits outdo the costs of the actions, but also that people with a similar view on the subject always are more likely to act together (Lichbach, 1994). Additionally the engagement in VSIU seems to be a tool to do something, and the vision of thousands having the same experience can spark this common identity and energy. Using the network as a tool is more in coherence with mediated mobilization and the use of new media as the means to mobilize social movements and inspire CA (Lievrouw, 2011).

Another reason to join and remain in VSIU is the possibility to influence as a collective. IC says “I have been active in various actions and it feels good to do something hands on”. 2A came in touch with the unaccompanied children and youth as social science teacher to asylum seekers in Sweden and later on became a guardian.

“I wondered what else I could do and registered to become a guardian at the municipality. Pretty soon I noticed that there was so much that wasn’t working. Even though I was completely new to both the guardianship and asylum rights, I realized that it was even worse in authorities, homes, schools and county councils. In the spring 2017 I received the tip of a colleague to my husband about VSIU. Since then, I have been through an intensive course in asylum rights 24/7.”

Quite clearly 2A already was working for her private good out of the need she saw in society, but it was the connection to others in VSIU that made her convert these concerns on social change into CA (ibid) in VSIU. Likewise the administrators mention that one purpose of VSIU is to find collaborations and 1C answers that; “I know that legal information I have

received has made a difference in cases and helped me in my thinking and resonance about

the asylum process of several young people .”

Likewise 1E emphasises the support as one of the mayor benefits of being part of the movement, even though she also mentions the knowledge and expertise as important reasons both to become a member and to stay active. “I shouted kindly for help and did not know how to proceed. I got tips and links […] I received an invitation to the chat, I received emails […], I received phone calls about places to hide. Invaluable support”. This implies indications of strong of meaningful relationships, and even trust which according to Castells is the glue that sticks people together in social contracts (2015:1).

However it also associates to the impact of membership on the activity on Facebook its’ volume and reach of dialogue. Nah and D. Saxton (2012) identify membership to have decreasing impact on social media impact and reach. However this is contradicted by the focus groups who in different forms express how the membership inspires to be more active on Facebook as a platform for political advocacy and influence. 1E explains how the support within the network has developed while increasing in numbers as “We who have received help are passing the help on to others in the same situation” with indicates continuing training. In more concrete terms 2B identifies the features of VSIU to be;

“1 Give voice, comfort and support inside on the network 2 Provide common power for the professionals

3 Give civil society a political and public voice.”

Thus these answers on one side enhance the importance of the collective being visible as one big group. On the other side the importance of the availability has been expressed in the constant access to support and expertise in the network.

The knowledge and awareness about the strategies and impact of the network was assumed to vary according to the specific engagement and necessities of each member. However several members, through the survey and the focus groups, emphasises the political advocacy as a main purpose of both the network and their personal engagement and connects their actions directly to the results, which is interesting taken the discussion on slacktivism. For example 2C says;

“I hear from the administrators that the media is watching a lot of statistics on followers, clicks and comments on VSIU's public page, and it's important that we are active there. So indirectly, when the politicians see that it matters. Otherwise, I think it's important to email directly to politicians, with comments on articles that are public, etc.”

With no doubt the actions create a good feeling for the individual based on the feeling of making a difference but if the administrators are right, as Barberá et al. claim (2015) the digital activism VSIU implement on Facebook actually does contribute to the probability of winning and making a difference. In either case, the activity on Facebook encourage the members to not give up which can be argued increases the resources of energy. However the increase of resources is not enough alone to solve the CA problem, but as the other solutions it is an incomplete explanation of CA and requires combinations (Lichbach, 1994:23-25). Other issues related to Facebook that are brought up are whether or not it actually connects people and create what Lovejoy and D. Saxton calls meaningful relationships (2012). 2B states that;

“It [Facebook] was supposed to be a way for people to get closer to each other. And it may just happen if you have something to gather around. I have been invited to several other communities due to the involvement in VSIU. So it works, one thing leads to another. I still do not think that so many of my "regular" contacts on Facebook have joined because of me. Perhaps they have become a little more aware than they would otherwise.”

However if we focus on the advantages 2A claims that “The biggest advantage is that neither time, work, country or something else sets limits for who can meet online and exchange knowledge. Imagine getting instant info from someone in Afghanistan. Absolutely impossible only a few years ago!”. She refers to both the availability and ubiquity that ICT’s are characterized of and adds “Social media is good for easy and direct spread of info such as reports, live broadcasts, sentences, etc.” However she completes by adding that “it's easy to get caught up and think everyone sees this. Through the filter bubbles, it’s mostly those already established who will be updated” which is more in accordance with 2B.

The respondents in the focus groups all agree on the statement of the incredible work the administrators do. According to 2B “Those who manage the conversations must do a tremendous job, because there are not so many low-water comments and no trolls to be found.” Even though they reflect upon the challenges and difficulties about Facebook, the administrators point out that the benefits make it worth it;

“We really only see the benefits of organizing ourselves on [Facebook]. There seems to be a great value in joining a group of like-minded people. There is an educating purpose as well. For example, I read in a thread yesterday that a person answered a question and then expressed that "oh, I'm new here and answered a bit foolish, I'm learning", and someone else answered "yes, we are here together, you are in the right place, we learn from each other"”.

The perspective of ‘learning by doing’ and the importance of availability are returning subjects in the focus groups and direct to both planned and unplanned actions (Lichbach, 1994). Consequently there is space for flexibility and development on strategies and methods.