Nudging in the right direction

A qualitative study on nudging online grocery store environments

BACHELOR DEGREE PROJECT

THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Sustainable Enterprise Development AUTHORS: Thérése Nelson & Jessica Nilsson

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Nudging in the right direction - A qualitative study on nudging

online grocery store environments

Authors: Thérése Nelson & Jessica Nilsson

Tutor: MaxMikael Wilde Björling

Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: Consumer behavior; digital nudging; grocery store industry; nudging; online.

___________________________________________________________________________

Abstract

Problem: Nudging has come to be widely used by organizations who wish to influence the

choices of their consumers. This concept has been greatly praised, criticized, discussed, and researched; however, this has mostly been set in offline environments, making nudging in online environments an area in need of further research. Over the last couple of years, grocery store e-commerce has increased immensely in popularity, a trend that is predicted to last and grow. Due to this, companies that offer online shopping will be required to understand and adapt in order to stay in the game.

Purpose: This paper is an attempt to increase the knowledge of digital nudging and its

usefulness, as a way to cope with a drastic demand change within the grocery store industry. The purpose of this study is to examine how nudging can be used to improve online shopping experience in the grocery store industry in Sweden. This paper is intended for students and professionals in business administration, and as well for nudge architects in the online grocery store industry.

Method: This research is a qualitative study that has been conducted under an interpretivist

paradigm with a dual research approach, deductive and inductive. Data have been collected through a literature review, one interview with a field expert within grocery store nudging, and nine consumer families. After analyzing these data, conclusions could be drawn in answer to the study purpose.

Conclusion: The main conclusion drawn from this study is that there are such large differences

in consumer behavior in online versus offline environments that it is practically impossible to transfer nudges without making any adaptations or changes to the environment and/or the consumers behavior. Rather than trying to convert analog nudges to digital, the authors found that listening to the consumers’ wishes is the best way to find inspiration for digital nudge creation.

Acknowledgements

Throughout the process of writing this thesis, the authors have received great support which have made it possible to conduct this report. For this we would like to express our gratitude. Firstly, we would like to thank our tutor MaxMikael Wilde Björling for providing us with

advice, useful feedback and great knowledge that has helped us immensely.

We would also like to address our gratitude towards Anders Volmerdal, who has contributed to this thesis greatly with his expert knowledge.

Thirdly, we would like to thank the nine families who volunteered for the model case interviews.

Lastly, we would like to thank our seminar colleagues who have brought valuable feedback throughout the project.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION ... 6

1.1BACKGROUND ... 6

1.1.1 Nudging... 6

1.1.2 The grocery industry ... 7

1.2PROBLEM DISCUSSION ... 9

1.2.1 Problem statement ... 10

1.3PURPOSE ... 10

1.4DELIMITATIONS ... 11

2. FRAME OF REFERENCE ... 12

2.1METHOD FOR LITERATURE REVIEW ... 12

2.2ANALOG NUDGING AND DIGITAL NUDGING ... 13

2.3OFFLINE AND ONLINE SHOPPING EXPERIENCE ... 14

2.4CONSUMER BEHAVIOR AND NUDGE PLACEMENT ... 15

2.5ONLINE USER INTERFACE... 18

2.6ETHICAL ASPECTS OF NUDGING ... 19

2.7CHAPTER SUMMARY ... 20

3. METHODOLOGY AND METHOD ... 22

3.1RESEARCH PHILOSOPHY ... 22

3.2RESEARCH APPROACH ... 22

3.3RESEARCH DESIGN ... 23

3.3.1 Interview with field expert... 23

3.3.2 Interviews with consumers... 24

3.4DATA COLLECTION... 27

3.5DATA ANALYSIS ... 28

3.6RESEARCH ETHICS AND DATA QUALITY ... 30

3.6.1 Research ethics ... 30

3.6.2 Data quality ... 31

4. EMPIRICAL FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATIONS ... 32

4.1IN-STORE BEHAVIOR AND NUDGING STRATEGIES ... 32

4.2BRAND LOYALTY AND DIGITIZATION ... 34

4.3THE TRADITIONAL GROCERY STORE AND THE FUTURE ... 35

4.4DEMONSTRATIONS ... 36

4.5ONLINE VERSUS IN-STORE DIFFERENCES ... 37

4.7FACTORS DRIVING CONSUMER DECISIONS ... 40 4.8OFFERS ... 42 4.9ONLINE DESIGN ... 44 4.10THE SCARCITY EFFECT ... 45 5. CONCLUSION ... 46 6. DISCUSSION ... 48 6.1PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS ... 48 6.2THEORETICAL CONTRIBUTION ... 49 6.3FUTURE RESEARCH ... 49 REFERENCES ... 51 APPENDICES ... 56

APPENDIX 1:INTERVIEW QUESTIONS FOR IN-DEPTH EXPERT INTERVIEW... 56

1. Introduction

Chapter 1 welcomes the reader into this report by broadly introducing the context of the research topic and thereafter narrowing it down through a problem discussion and statement. From the problem statement, a purpose is clarified and the two research questions for this study are presented. The chapter ends with an overview of what delimitations the authors have made in order to optimize the study.

1.1 Background

1.1.1 Nudging

According to neoclassical theory economic decisions are assumed to be based solely on calculations and free from emotions. Even though this traditional assumption is still in use, empirical and experimental evidence fortifies inclusion of psychology when analyzing economics (Mullainathan & Thaler, 2000; Lehner, Mont & Heiskanen, 2016). Many economic decisions are sensitive to psychological factors, e.g., retirement saving is strongly sensitive to human willpower. The concept of behavioral economics combines these fields and explores the effects of human actions and limitations on economic markets. In many cases, these analyses are able to fill in the blanks where neoclassical economics have failed to explain why some things happen (Mullainathan & Thaler, 2000).

From the very core of behavioral economics comes strategies for policy makers to alter people’s behavior in a foreseeable manner and affect their choices. When such altering is accomplished without changing what options are available or the economic incentives, it is referred to as nudging (Thaler & Sunstein, 2009). Further, the term choice architecture is used to describe the altering, or design, of how choices can be presented to consumers (Abdukadirov, 2016). Nudging has come to be widely used in choice architecture, e.g., by policy makers or organizations who wish to influence the choices of their consumers.

Seeing how nudging is about making changes in the choice environment, it is logical to conclude that such changes are dependent on the environmental context. The same nudge cannot therefore be implemented in a gym and in a restaurant. Further, as we are right in the middle of a digitalization era and people are spending more time than ever online, the digital

world has surfaced as a new and important context to be aware of. Referred to as ‘digital nudging’, this is described as influencing people’s behavior in digital environments through the use of user interface design elements (Weinmann, Schneider, & Brocke, 2016). Because people will be affected by the contextual design of the online environment no matter if it is deliberate or not, understanding of digital nudges can constitute a powerful tool for choice architects (Schneider, Weinmann & vom Brocke, 2018; Weinmann et al., 2016). Moreover, there is a secondary use of digital nudging which is about analyzing the offline world to determine where which nudges could be effective (Gregor & Lee-Archer, 2016).

Since it is impossible to present any choice completely neutral, all decisions made in the design process will result in some sort of influence. Designers who fail to understand the environment they are working in may end up with unwanted consequences (Weinmann et al., 2016). This is true for nudges no matter whether they are set in a digital or physical environment. However, one major difference between these settings is the lead time, that is, the time from initiation to completion of a process, in this case a decision (Harrison, Hoek & Skipworth, 2014). Many things play out much faster online, which is an important factor to consider for choice architects. While nudges in a physical setting commonly affect people’s choices in general, digital nudges are more centered to influence at the exact point of decision making (Schneider et al., 2018). It is central for the understanding of the rest of this paper to realize the difference between these two settings. Therefore, the physical environment will hereafter be referred to as ‘offline’ and the digital environment will be referred to as ‘online’. Further, nudging in online settings will be referred to as either online nudging or digital nudging.

1.1.2 The grocery industry

As defined by The Swedish Food Retailer Federation, the grocery industry consists of four actors; grocery stores, agriculture, food producers, and hotels and restaurants, where the grocery stores represent the largest share of the total net turnover (Svensk Dagligvaruhandel, 2020). The grocery industry is the largest industry in Europe and the third largest industry in Sweden. With a turnover of about 195 billion SEK [2019], this industry is a significant influencer of the Swedish economy (Livsmedelsföretagen, 2021). In accordance with the topic of this paper, the focus will henceforth be narrowed off to the Swedish market and to the grocery store section of the industry, referred to as the grocery store industry. This industry section will be addressed in terms of offline and online environments, as defined above, where the main focus will be on the latter.

The popularity of online grocery shopping has increased a lot over the last few years, but the trend goes all the way back to 2007 (Axfood, n.d.; Svensk Digital Handel, 2018). It began with Middagsfrid who was the first company in the world to offer prepared shopping bags with recipes and ingredients for planned dinners (Axfood, n.d.). They also created an online option where the customer could shop groceries similarly as they would in stores, using a click-and-collect method. The pre-packed dinner bags solution has been used and developed by multiple actors following Middagsfrid and was until 2016 the most popular type of online grocery shopping (Di Digital, 2017). Since then, the largest actors within physical grocery stores in Sweden have adopted the click-and-collect service and developed functioning and modern e-commerce stores, making this the most popular type. In 2017, the online food trade claimed 1,6 percent of the total market share of grocery sales in Sweden, an increase that has shown to continue (Svensk Digital Handel, 2018).

The last years’ large increase in popularity of online grocery shopping is most likely due to this development of e-commerce stores (Svensk Digital Handel, 2018). Between the years 2017-2019 the average increase of online shopping in Sweden was approximately 25% each month (Ehandel SE AB, 2020). In late 2019, the spread of a dangerous corona virus was detected in China which quickly came to spread all over the world, and on March 11th, 2020, the World Health Organization declared a pandemic (WHO, 2021). The first case in Sweden was diagnosed on January 31st (Folkhälsomyndigheten, 2020). One of the first behavioral changes among Swedes in adapting to this situation was that they ordered their groceries online more than ever before. This generated a massive peak in the statistics of online grocery shopping in Sweden, with a starting point in the month of April. Online grocery shopping in Sweden in April 2020 was 101.2 % larger than the same month in 2019 (Svensk Dagligvaruhandel, 2020). In the year that has passed since, the pandemic as well as this peak is still ongoing ( Svensk Dagligvaruhandel, 2021).

Trend peaks like this is where online grocery retailers have their opportunity to attract loyal customers. Just because a certain customer began shopping groceries online due to a pandemic, does not necessarily mean that this customer will quit this when the pandemic is over. It is the online shopping experience that mainly will determine whether or not this customer is pleased with their new habit, or if they will prefer returning to their old one when they can. An online shopping experience consists of many factors - such as time, prices, ease of use, customer service, and more - and if those factors are appealing enough the odds increase that new customers might become loyal ones (Dennis, Merrilees, Jayawardhena & Tiu Wright, 2009).

1.2 Problem discussion

People make hundreds of choices every day. Some are intentional and some are not. Regardless, the outcomes of choices are affected by numerous factors. For a long time, scientists have been clinging to the assumption of neoclassical economics that people make decisions solely based on rational deliberations. However, behavioral sciences claim a less rational cause behind the decision-making process and that behavioral biases and the environmental setting should be added to the equation (Lehner et al., 2016; Weinmann et al., 2016). Also, Johnson et al. (2012) highlight the importance of environmental settings, or context, stating that how the choice is presented has a huge influence on the outcome.

Even though it has been established that supermarkets in general already are quite successful in using nudging strategies, empirical evidence suggests that the food provision industry still has much to gain from becoming more active in choice architecture towards consumers. This opportunity may be addressed by extending the use of social marketing strategies and external nudging (Filimonau, Lemmer, Marshall & Bejjani, 2017). An important consideration here is that motives for using nudges in supermarkets can differ. Some nudges may be rooted in increasing profit for the retailer, while some may be centered around a smart and profitable purchase for the customer. Of course, finding nudges that meet both motivations at once would be ideal (Huitink, Poelman, van den Eynde, Seidell & Dijkstra, 2020). Further, with an increasing popularity to shop online, a logical assumption would be that the strategies currently used may decrease in output produced, as they only have effect in physical stores. These are implications of an incentive for food retailers to expand their work with nudges adapted to the online world, a focus area which has not previously been of such influence as it is now (Weinmann et al., 2016).

In today’s society, the digitalization of our professional and private lives has almost become inevitable. The online presence of individuals is increasing and most of the errands people have can be done in an online setting. Due to this, many decisions are made in digital contexts. The difficulties that lay in translating offline nudges to online environments may be part of the reason for this yet limited research in the field. To specify, Dennis et al. (2009) found that online consumption is lacking possibilities to touch and feel the products, but it might be stronger in some situational factors, such that the consumer makes their decision in the comfort of their home instead of in a stressful setting in a shopping mall, and that navigability and web atmospherics are key aspects online that practically do not exist offline. Further, researchers

have determined that what they call atmospheric stimuli has considerable influence on consumers’ purchase decision processes. Such stimuli factors are smell, colors and music, and they enable physical purchase environments to arouse and entice customers in a way that online actors cannot do (Mattila & Wirtz, 2001; Turley & Milliman, 2000).

1.2.1 Problem statement

The concept of nudging has been greatly praised, criticized, discussed, and researched; however, this has mostly been set in offline environments, and online nudging is thereby an area in need of further research (Ranchordás, 2019). Since nudging was conceptualized back in 2009, it has been widely used in business strategies in order to lead consumers in a specific direction (Thaler & Sunstein, 2009). These strategies have for the most part been developed for offline environments and are not necessarily transferable into online environments. This leads to uncertainties as it is unknown how nudges will eventuate in a digitized environment. Even though this entails large risks and strategizing costs, companies that want to be up to date need to invest in the development of digital nudges as these are likely to enhance the online shopping experience for both consumers and businesses and can create competitive advantages in the market. Digital nudging has been lightly touched upon, but there is a definite research gap present, including but not limited to clarification of the underlying theoretical mechanisms (Weinmann et al., 2016).

1.3 Purpose

This paper seeks to examine how the socioeconomic concept of nudging is and can be used in an online setting to improve the online shopping experience. Digital nudging is not yet as commonly known or as widely used as nudging in offline settings (Weinmann et al., 2016). As the e-commerce market is fastly developing, and Swedish consumers are changing their lifestyle and habits accordingly, online product providers are experiencing pressures of higher demands. This is true for all online actors in general, and for the grocery store industry in particular (Svensk Dagligvaruhandel, 2020). The recent time’s continuous upwards movement of this trend constitutes a strong support for suggesting that the trend will last and grow further in the near future, which is why companies that offer online shopping will be required to understand and adapt in order to stay in the game. They might even be able to seize opportunities and create competitive advantages. This paper is an attempt to increase the knowledge of digital nudging and its usefulness, as a way to cope with this drastic demand

change within the grocery store industry. Hence, the purpose of this study is to examine how nudging can be used to improve online shopping experience in the grocery store industry in Sweden. The issue will be addressed from a management perspective by looking at consumers’ perceptions, experiences, and opinions in the case. The results of the study may come to serve as a useful tool for e-commerce businesses in their strategizing processes.

Based on this purpose statement, the following research questions have been established to guide the research:

Research question 1: What existing nudge strategies within physical grocery stores can be

implemented in an online environment?

Research question 2: What online focused nudges can be identified for grocery stores?

1.4 Delimitations

This research involves interviews with a sales consultant and with a set of consumer interviews organized as model case families. The workplace for the consultant is the city of Jönköping. The cities where the model case families live and do their grocery shopping are Stockholm and Gothenburg. These can all be considered larger cities. Grocery stores in larger cities are able to offer both click-and-collect and home delivery services, an important factor of this study, whereas grocery stores in rural areas may not be able to offer this to the same extent and variation. If this delimitation had not been made, there may have been a risk for a biased result.

2. Frame of reference

Chapter 2 sets the frame of reference for this report. Based on theories and previous studies, this chapter sets the context for the empirical study. The coverage on online versus offline settings, nudging, nudge placement and ethical aspects of nudging that is presented here contributes the knowledge needed for the reader to fully understand the study and its results. Lastly, the chapter is summarized in section 2.7.

2.1 Method for literature review

The following section is a literature review which has been a critical evaluation on current research of the subject nudging in the context of consumer behavior sciences. The literature review is based on 13 academic articles, which of 9 are peer reviewed, and 7 books. The majority of the literature was found through the Jönköping University database Primo and the database Google Scholar, using the keywords nudge, nudging, behavioral economics, consumer

buying behavior, consumer decision making process, ethics in nudging, e-consumer behavior, digital nudging. On a second level, further useful literature was found when studying the

reference lists of sources found through the databases. This was a way for the authors to streamline the information gathering process, and to make it possible to go even deeper into the subjects. In accordance with the suggestions by Collis and Hussey (2014), this information gathering was done using a systematic approach. Additionally, some sources were found thanks to recommendations from professors and tutors.

The authors mainly focused on finding academic articles that are peer reviewed as a way to ensure credible sources. The articles that are not peer reviewed were evaluated and reviewed thoroughly to make sure that the information presented in the articles were credible. The articles used in this study were written between the years 2003-2020, with the majority written after 2015. By mapping the gathered literature, as recommended by Collis and Hussey (2014), the authors defined five subheadings that relate to the researched subject and that interlinks with the literature.

2.2 Analog nudging and digital nudging

Nudging in physical environments, analog nudging, is traditionally aimed at the general public and is more direct compared to online settings. Some examples for the grocery store industry are nice smells to entice more people to come into the store, and soothing music playing which makes people feel less stressed and they stay in the store for longer (Spangenberg, Grohmann & Sprott, 2005). However, due to the constraints of online environments, e.g., not being able to affect human senses like in the examples above, nudging in online environments, digital nudging, differs from traditional techniques. As a consequence, nudges need to be more personalized. Digital nudges are often based on big data, which are generally very large sets of data generated through usage of technology and the Internet, such as individuals using social media or personal information held by banks, governments, or public sector organizations. Grocery retailers use big data to track consumers’ behavior and target customers with personalized offers (Cale, Leclerc & Gil, 2020; Cambridge Dictionary, 2021).

The outcomes of analog nudging techniques differ as not all consumers respond to the same things. However, in online environments where big data can help build personalized nudges, the success rate of each nudge is likely to be much higher. Big data driven nudges are dynamic, meaning that they are updated with real time feeds. If nudge creators incorporate such dynamics in their design algorithms, they will create an increased personal feel. Further, to make big data into manageable dimensions, it is often broken down in layers. The more layers the data has, the more detailed information the choice architecture has access to. Carolan (2018) explains the division of first-, second- and third-party data as (i) data acquired from membership and/or shopping loyalty cards, (ii) data acquired through mutually beneficial agreements like airlines or hotel chains, and (iii) data such as education level and income which is acquired using external actors.

In adapting to the online context, Gregor and Lee-Archer (2016) identify three pillars: policy, process and technology, as equally significant factors of digital nudging. These pillars cover social investment, adoption of nudges, and predictive analytics and real time application (Gregor & Lee-Archer, 2016). This breakdown of the components of digital nudging implies how complicated the process is. In the last decade, technology and behavioral patterns of individuals have been combined more frequently using big data and algorithms. By using the collected information as a tool to personalize offers or adjusting prices to the willingness to pay off target customers, large companies nudge customers in their preferred direction (Ranchordás,

2019). Companies that have the capacity to manage and use big data as a basis for designing nudges can map individuals’ habits in a more detailed manner than those who lack such abilities (Carolan, 2018).

2.3 Offline and online shopping experience

Physical purchase environments are traditionally stores or supermarkets, while digital purchase environments most oftenly translates to websites. The concept of nudging has long been used by supermarkets to steer people towards purchase choices that benefit the retailer (Huitink et al., 2020). Some examples are (i) placing the most popular item (often dairy products) at the back of the store to force the customers to pass all other shelves, increasing the chance that more items end up in their carts, and (ii) placing an item you really want to sell directly to the right of the bestseller, increasing the chance that customers will grab it since most people are right-handed (Mont, Lehner & Heiskanen, 2014; Underhill, 2000).

Further, nudges are more effective when they are created based on the psychological principles of human decision making. The decoy effect, the scarcity effect and the middle-option bias are examples of how this can be implemented. The decoy effect is to strategically place an unattractive item, a decoy, next to the product the organization wants the customer to buy, increasing the attractiveness of that product. The scarcity effect comes from that individuals tend to perceive scarce items as more attractive, so highlighting that a product is very popular or that the stock is very low might entice customers to purchase. Lastly, if an organization presents three or more items sequentially ordered by price, most often the customer will choose the middle option, this is called the middle-option bias (Schneider et al., 2018).

In online environments such tricks are difficult to apply. Instead, factors like the website's image construct, the e-retailer’s interactivity with the consumer, the ease of navigation and a pleasant web atmosphere stimulates the consumers’ emotions and can affect the purchase decision (Dennis et al., 2009). Consumers go through several different stages when shopping online and there are many factors that will influence their purchasing decision. The two major factors are what product is being purchased and where it is purchased, suggesting that the purchase environment possesses a huge influence (Mallapragada, Chandukala & Liu, 2016). While the offline shopping experience has its focus on getting the customer to physically move to the products, the online environment is forced to be more focused on catching the customer’s eye.

Because of this focus, eye-tracking is one of the most useful tools for building successful online shops. Eye-tracking is a method where the visual attention of an e-commerce website visitor is analyzed. The result is often displayed in the form of heat maps, where higher heat intensity corresponds to more time and attention spent on that area of the site (Bergstrom & Schall, 2014). Such analysis can be very helpful for nudge architects as it provides them with information on where to strategically place their nudges. The tool itself can be used for many different measures, depending on the interest of the user. In grocery e-commerce, some measures of interest may be conversion rate, new and returning visitors, and average sale (Bergstrom & Schall, 2014). Eye-tracking over time can provide an understanding of how a customer moves through the website, which is key in understanding consumer behavior. This tool can help with anything from knowing if people find it difficult to place items in the cart and find the checkout, to knowing which font makes more people happy. This way of analyzing consumer behavior is completely different to what is used in physical environments, and it is an important tool for online nudge development.

Even though the general discussion mostly is about either offline or online, these two worlds may also be combined. Referred to as phygital, this creates a deeper experience for the consumer. Phygital enables the consumer to experience both worlds, forcing retailers to develop their previously only physical businesses into more technological ones. By optimizing their experiential strategy through phygital solutions, such as self-scanning or payment technologies, retailers are able to extend the shopping experience for their consumers (Batat, 2019). Becoming phygital is a must for any retailer who wants to stay in the game, as consumer behavior trends are steering in that direction.

2.4 Consumer behavior and nudge placement

Even though designing a nudge can be quite an extensive project all on its own, one must not forget that on a larger scale it makes up an important part of the whole consumer decision making process. In accordance with the topic of this paper, the focus here is on consumers’ decision making in the context of grocery shopping. When it comes to shopping of any kind, consumers’ decisions are extremely sensitive to marketing, implicating a close relationship between consumer decision making theories and marketing models. A commonly used model here is the consumer proposition acquisition process model. This model shows six steps of a consumer's decision-making process that a manager needs to take into account, even if the consumer does not always go through the entire process. One of the critiques the model has

gotten is that it does not take impulse buying decisions into account nor fast moving consumer goods, milk being one example (Nordfält, 2005). However, Baines, Fill and Page (2011) argue that the model is used to understand the process of consumer decision making when planning in marketing and the process can be affected by other factors such as personality, situational factors, perception, or social pressure.

The reasoning behind this six-step model lies partly in Festinger’s (1957) cognitive dissonance theory. Cognitive dissonance suggests that we are motivated to reevaluate our beliefs, attitudes, opinions, or values as these can be affected by circumstances and can change the original perception (Festinger, 1957). By the logic of the model, a purchasing decision might be regretted as perceptions of the original issue could have been changed. Cognitive dis sonance can be experienced if the product or service does not meet the initial expectations of the consumer, and it might be viewed as a form of disappointment (Baines et al., 2011). Nordfält (2005) argues that retailers should adapt communication strategies by using nudges as these navigate customers through purchasing environments to make decisions and as these influence non-conscious factors within the decision-making process.

Although the consumer proposition acquisition process model is highly useful, it is not optimized for online settings. This is an issue that Smith and Rupp (2003) tackled with a proposition of their consumer decision making model for online shopping behavior. The Smith and Rupp model consists of three interlinked stages: the operational input, the process, and the output stage. The first stage is where the website's marketing efforts and socio-cultural factors affect the consumer. During the process step psychological factors and experience help the consumer to make a decision. In the output stage the consumer makes the purchasing decision (Smith and Rupp, 2003).

The Smith and Rupp model and the consumer proposition acquisition process model are founded on the same theoretical knowledge, with the exception that the Smith and Rupp model enables a deeper understanding of how consumers act in online environments. Although the Smith and Rupp model simplified the knowledge into three major stages, instead of six, the model takes the most vital parts of the consumer decision making process into account with adaptation to online environments, and within the three overarching stages are thorough descriptions of influencing factors (Smith and Rupp, 2003). The stage where the consumer evaluates their decision to purchase a product or not is the optimal stage to place a nudge, this is the same for both models. The motivation for this placement rests mainly in the fact that the

following step after this is where the consumer makes their purchasing decision. Since nudges are aimed at influencing the purchasing decision, it is strategically smart to place them right before this happens.

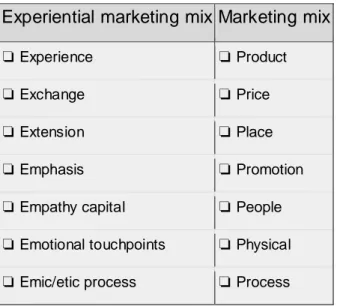

To facilitate strategic nudge placement in these models, marketing tools can be helpful. Traditionally, the marketing mix of the 7Ps have been a guiding tool for marketers in attracting consumers to the products in focus (Batat, 2019). Batat (2019) also presents a new, more elaborated marketing mix technique - the experiential marketing mix, also the 7Es. The composition of these two marketing models is shown in Figure 1. The modern 7Es model captures the psychological and socio-cultural parts of the consumer decision making process when transitioning from a physical environment into a virtual one in a way that the 7Ps model is weaker at capturing. By combining the Smith and Rupp consumer behavior model with this 7Es marketing tool, nudge architects are equipped to keep up with updates and changes in how consumers behave in online environments.

Experiential marketing mix Marketing mix

❏ Experience ❏ Product ❏ Exchange ❏ Price ❏ Extension ❏ Place ❏ Emphasis ❏ Promotion ❏ Empathy capital ❏ People ❏ Emotional touchpoints ❏ Physical ❏ Emic/etic process ❏ Process

Figure 1. The experiential marketing mix and the marketing mix (based on Batat, 2019). One of the most central decision-making factors for both offline and online environments is the value that each customer assigns to the product(s) (Mallapragada et al., 2016). The value of a product is not only monetary and may differ between consumers in terms of how they personally value product information, delivery time, customer service, and other non-monetary characteristics. Further, Dennis et al. (2009) claim consumers’ personal beliefs, attitudes, and intentions to be determinant for their purchasing decisions. From this, it is evident that online and offline shopping share many similar factors that can affect the customers’ decision-making processes. However, a distinctive difference between the two settings is what role these factors

play in the particular environment. Because of this, not all knowledge we have about the classical physical shopping experience is directly transferable to online environments.

The major differences in consumer decision making in online environments compared to in physical environments rely on the consumers’ information search, the purchase environment, and the knowledge that consumers are more conservative in an online environment. Consumers are more comfortable to try new products and brands when they are able to feel and touch them in a physical environment whereas well-known brands are more successful in online retail environments. Well-known brands with detailed product descriptions and possibly lower prices comfort consumers into purchasing the products. The website setting allows for consumers to gain more information about the products and with help of history saving technologies the consumer can purchase the previously bought products and save time (Wei, 2016).

2.5 Online user interface

In online environments nudging is most often presented through choices that individuals have to make through user interface (Weinmann et al., 2016). Online user interface is described as the link that connects the individual to the technology. User interface will steer the individual in the direction that the web designer wants, therefore designers need to understand the behavioral effects of their design to avoid unintended outcomes of nudges (Schneider et al., 2018; Weinmann et al., 2016). When understood and used correctly, digital nudges are utilized to alter what choice alternatives are presented, how they are presented, or both. The challenge choice architectures have in online environments is to design nudges that go beyond the human-computer interaction (Schneider et al., 2018).

Schneider et al. (2018) present a digital nudging design cycle where four steps are included. The first step is to define the goal of the nudge; the organization must decide what the goal of the nudge is, e.g., for an online grocery store, one goal could be to increase sales. The second step is to understand the decision-making process, where the designers need to understand the goals of the consumers and identify what factors influence them to make decisions. The two consumer behavior models presented in section 2.4, the Smith and Rupp model in particular, can be of great guidance here. The information gathered in the two first steps of the design cycle combined will help design the nudge, which is the third step. The fourth and final stage is to test the nudge. Online environments allow for fast changes of design and output, which makes testing and adjusting digital nudges easier, but also more challenging. This model takes

the advantages of web technologies into account, such as real-time tracking, analysis of user behavior and personalization of user interface (Weinmann et al., 2016).

Individuals in online settings are more willing to disclose information about themselves, providing designers with more information to build a digital nudge. However, individuals are also more cautious about accepting default options online, meaning that designers need to advance their work in order to be equally successful (Schneider et al., 2018). Designing digital nudges based on information from the user interface and the human decision process will most likely be beneficial for both consumers and organizations. However, research about behavioral aspects of user interface is limited. (Weinmann et al., 2016).

2.6 Ethical aspects of nudging

It is important to consider the ethical implications of nudging, as it is a concept that intrudes people’s daily environments. Nudges are supposed to help people towards better choices (Thaler & Sunstein, 2009). However, this is not always how they are used, and sometimes the motives behind a nudge can be strongly questionable. Nudges are not necessarily used to benefit the person being nudged (paternalistic nudging). It is not unusual to observe nudges that instead benefit the creator of the nudge, or a third party, e.g., the environment (non-paternalistic nudging) (Schmidt & Engelen, 2020). In his deeper discussion of the subject, Sunstein explains how some nudges risk being considered manipulative or controlling rather than helpful, and the importance for designers to be aware of current ethical implications in order to minimize such risk (Sunstein, 2015).

Some arguments against nudging are about freedom of choice and absence of domination. The criticism against intrusion of freedom of choice is defended by differentiating between the external options available and the execution of the freedom of choice itself (Schmidt & Engelen, 2020). It is rather that one of the criteria for nudges is that they must not interfere with individual dignity (Sunstein, 2015; Thaler & Sunstein, 2009). The absence of domination criticism is about a risk of feeling subordinate and finding oneself in an undesired power relationship (Schmidt & Engelen, 2020). This means that nudge designers must be cautious about the risk of nudges becoming a tool to exercise control over the nudge users.

Nudging is a topic that is highly sensitive to ethical dispute and public distrust. Whether or not the concept of nudging is ethical is irrelevant, since nudges as well as choice architecture are inevitable (Sunstein, 2015). The considerations to be made lay instead in the design process of

each nudge, to ask if this particular nudge and its execution are ethical. We know that nudges can have good or bad intentions, and that the responsibility to make them objective lies in the hands of the designer (Thaler & Sunstein, 2009). Used correctly, nudges can be a great tool to help people spend more time and attention on issues that matter more (Sunstein, 2015).

Since nudges deal with alterations of contexts and environments, they are often criticized to be manipulative (Schmidt & Engelen, 2020). By choosing what is presented, how, and in which context, choice architects have the power to steer people’s choices. However, there is an argument to be made that one must alter with each context because if not, it would not exist (Schmidt & Engelen., 2020; Thaler & Sunstein, 2009). This debate will not be solved in this paper, nor in the next to come. But what can be learned from this is the great importance of keeping ethical views in mind when designing and dealing with nudges.

2.7 Chapter summary

Nudging is a widely used concept. In this study, it is applied to grocery shopping in both offline and online environments. To differentiate between the environments, the terms analog and digital nudging are defined. The main difference between these two are that digital nudges fail to affect the human senses in the same way that analog nudges can. To compensate for this loss, big data is a good tool for online nudge developers and designers (Cale et al., Carolan, 2018). With these tools, nudges can be more personalized, and they can be updated in real time, a feature that analog nudges do not possess.

Online and offline environments differ in many aspects, and that is why nudges are not directly transferable between them. The walk through a physical store is a completely different experience for the customer than a shopping spree in an online store. In a physical store, nudge designers are interested in analyzing how customers move and behave, whereas in an online store they are instead interested in eye-tracking (Huitink et al., 2020; Bergstrom & Schall, 2014). However, this must not always be an either or-situation. The concept of phygital invites us to combine the online and the offline environment (Batat, 2019).

Developing and designing nudges is a complex process, as the nudge itself is just one part of the whole consumer decision making process. Consumers are extremely sensitive to marketing, suggesting a close relationship between consumer decision making theories and marketing models. The consumer proposition acquisition process model is commonly used to understand the decisions that consumers make (Baines et al., 2011). Moving into a digital setting, the Smith

and Rupp model is an adapted version that aims to understand the same thing, but in a different environment (Smith & Rupp, 2003). When it comes to marketing models, the marketing mix of the 7Ps has been used for long. Lately, this model has been complemented with the experiential marketing mix that takes a wider perspective on what factors are of influence for the process (Batat, 2019). These models are of great help in learning about the differences between the two environments, and about how to strategize in them.

The connection between the choices presented and the consumer is called user interface. In online environments, online user interface is what connects the individual to the technology. Through interfering with the user interface, strategists can steer individuals in any direction they want, which is what nudging is all about (Weinmann et al., 2016). One strategy in this context can be to use a digital nudging design cycle. The cycle begins with deciding the goal of the nudge, then the decision-making process must be understood. The information gathered so far helps to complete the next step, to design the nudge. Lastly, the nudge is tested. If any adaptations are needed, the cycle starts over again. Such high-tech tools that are used for online user interface design place great demands on access to consumer information. Fortunately, individuals in online settings are often willing to share such information about themselves, e.g., through memberships (Schneider et al., 2018).

Since nudging is a concept that intrudes people’s daily environments, and the motives behind a nudge can sometimes be questionable, it is highly important to consider its ethical implications. There are arguments against nudging that concern freedom of choice and absence of domination, meaning that nudge designers must be careful about what control they exercise over nudge users (Schmidt & Engelen, 2020). Questioning whether the concept itself is ethical or not is mute since nudges are inevitable. The argument here is that one must alter with each context, because if not, it would not exist (Sunstein, 2015; Thaler & Sunstein, 2009). Used correctly, nudges can be a great tool to help people spend more time and attention on the right things.

3. Methodology and method

Chapter 3 presents the methodology and the method of this research. Firstly, the authors’ methodological choices are discussed in the contexts of research philosophy and research approach. Thereafter, the method is presented and motivated through a series of subheadings.

3.1 Research philosophy

Research philosophy is based on a system of beliefs and assumptions of the development of knowledge. When conducting a study, assumptions are made which will shape the outcome of the research, the methods used and interpretations of the findings. The assumptions made need to fit well with the research project and are important as they will help create a credible research philosophy (Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis, 2019).

As this paper studies the phenomenon of nudges, how these are used in different environments and how people perceive them, an interpretivist research paradigm was chosen as the most suitable research philosophy. The primary focus of an interpretivist study is to understand human behaviors and the fundamental meanings of an organizational life (Saunders et al., 2019). Nudging is a broad concept widely open for multiple interpretations, meaning that the social reality is subjective and can be perceived in different ways by different recipients. An interpretivist philosophy is highly suitable for nudging studies because of this particular construct (Collis and Hussey, 2014).

3.2 Research approach

This study has taken on a dual research approach. This is a qualitative study undertaken from a managemental point of view. The basic foundations for the research came from a literature review, from where the research strategy was built. This method for construction is referred to as deductive (Saunders et al., 2019). With a theoretical ground to stand on, the second part of the study was constructed using an inductive approach, which is suitable for an interpretivist study (Collis and Hussey, 2014; Saunders et al., 2019). This was done by collecting knowledge from one expert interview and 9 consumer interviews, from which conclusions have then been developed. The decision to take on a dual research approach was made in order to combine the

current knowledge within the topics of nudging and behavioral economics with observations to keep lessening an identified research gap.

3.3 Research design

The design of this research was built from a step-by-step approach to interpretivist study construction, and includes sample identification, choice of data collection methods, questions design, and collection of research data (Collis and Hussey, 2014). The research has been made in two parts: one interview with a field expert, and 9 consumer interviews. This section explains the two parts separately, covering sample identification, chosen data collection methods and questions design. The remaining step, collection of research data, is covered in section 3.4.

3.3.1 Interview with field expert

Interviews are suitable when the aim of the research is to study understanding, opinions and feelings through asking questions (Collis and Hussey, 2014). The number of interviewees may differ depending on the aim and construct of the research. In this case, one single interviewee has been selected for an expert interview on the grounds that this person is considered an expert in his field, and that the aim of the interview has been to gather knowledge and guidance for the construct of the questions for the following consumer interviews.

The interviewee selection process for this interview was carried out using judgmental sampling. This sampling method allows selection based on how knowledgeable the respondent is about the topic at hand (Collis and Hussey, 2014). The purpose of conducting an in-depth interview was to investigate how nudging strategies are used today in the grocery store industry and what expectations are realistic to have on its future usefulness. Thereby, finding a respondent knowledgeable about the field was absolutely necessary.

In order to start at a common ground and not lose focus of the interview goal, a set of seven open-ended questions were prepared for the interview (Appendix 1). This design choice was made to encourage the interviewee to provide longer answers and to develop from the prepared questions. To further encourage this, and to ensure maximum usage of the interview, the researchers came up with other questions along the way in response to what the interviewee said. This is referred to as probing the interviewee and means that the interview was semi-structured (Collis and Hussey, 2014).

Field expert introduction

The consolidated field expert, Mr. Volmerdal, works through his own business as a product sales optimization consultant. With 20 years of experience from sales, he eventually resigned to start his own business aimed at guiding grocery stores to better sales. The business is centered around a follow-up tool that measures what actually happens in the stores; how customers’ behaviors are influenced. Through using statistics, behavioral sciences, and product placement knowledge, he consults grocery stores in their sales strategies. Mr. Volmerdal’s experience and knowledge within sales optimization in the grocery store industry qualifies him as an expert within the topic of research.

3.3.2 Interviews with consumers

The design of the wider-sample part of the research was constructed from the learnings of the expert interview in combination with information from the literature review. This research design enables a combination of different types of data as a basis for research on consumer perceptions. Also, this part consisted of interviews, but here in the form of consumer interviews to get a view of the customer side of the topic. Since the aim has not been to produce findings generalizable to the population, but rather transferable to similar situations, these consumer interviews were organized in the form of model cases. This report equates ‘consumer interviews’ with ‘model cases’, and the expressions will be used interchangeably from here on. Networking was chosen as the sampling method for this part, where experience with certain situations was necessary in order for the interviews to be successful (Collis and Hussey, 2014). Some requirements to demarcate the respondents were made. These were: (i) the respondent must be an adult in their own household, that is, must be fully or partly responsible for grocery shopping, and (ii) the respondent must have shopped groceries both online and in store in the past six months. The goal of the consumer interviews was to understand consumers’ shopping behavior in relation to their perception of online nudges.

The consumer interviews were conducted the same way as the expert interview, as semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions (Appendix 2). The interviewees were encouraged to give examples and explain their reasoning mostly through probing (Collis and Hussey, 2014). The interview questions were designed in two parts, with one part asking general questions about grocery shopping habits, and one part posing case questions, that is, asking the respondents to choose which item they would purchase in a particular scenario. The

case questions were designed to expose the respondents to the nudging concepts middle option bias and the decoy effect. After going through all the model case interviews, the case question about middle option bias was removed from analysis. This decision was made on the grounds that it did not have the intended effect on the respondents, further motivated in section 3.4 below.

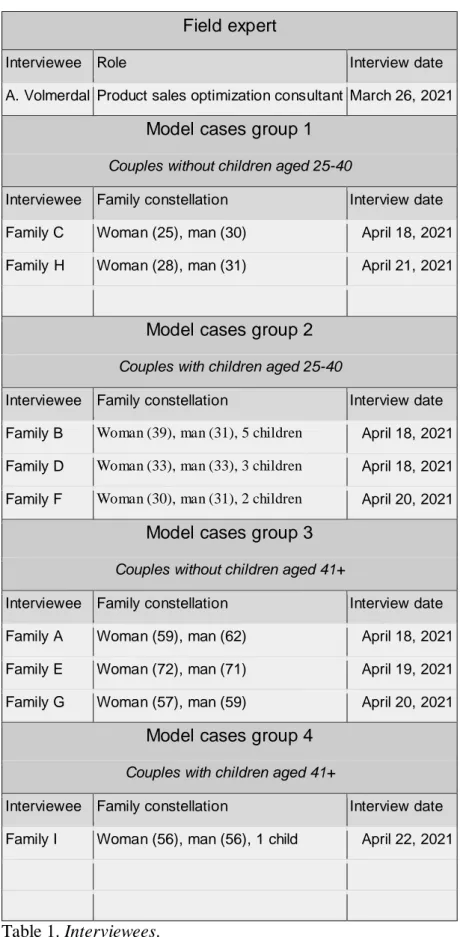

Being under an interpretivist paradigm, the researchers aimed for a limited study scope in order to acquire profound and inclusive data. To provide a good focus and reach the aim with a good coverage of model cases, a goal was set for the number of interviews to be between 8-12. 11 interviews were booked, whereof 2 ended up being cancelled by the interviewees.

The authors chose to divide the model cases into four demographic groups, as displayed in Table 1. The motivation behind this grouping lies in knowledge from the literature review and the expert interview. They both suggest that different demographic groups have different priorities when shopping for groceries. The two most prominent factors in this case were identified to be generation and having kids or not. Hence the groups were divided into families with and without children, and in two different age spans. The authors did not set an age limit for participating in the study, however, the stated requirements made sure that only adults participated as interviewees. The study was constructed like this in order to identify and confirm if there are any differences in priorities when grocery shopping between the age groups and in families with children.

Field expert

Interviewee Role Interview date A. Volmerdal Product sales optimization consultant March 26, 2021

Model cases group 1

Couples without children aged 25-40

Interviewee Family constellation Interview date Family C Woman (25), man (30) April 18, 2021 Family H Woman (28), man (31) April 21, 2021

Model cases group 2

Couples with children aged 25-40

Interviewee Family constellation Interview date Family B Woman (39), man (31), 5 children April 18, 2021 Family D Woman (33), man (33), 3 children April 18, 2021 Family F Woman (30), man (31), 2 children April 20, 2021

Model cases group 3

Couples without children aged 41+

Interviewee Family constellation Interview date Family A Woman (59), man (62) April 18, 2021 Family E Woman (72), man (71) April 19, 2021 Family G Woman (57), man (59) April 20, 2021

Model cases group 4

Couples with children aged 41+

Interviewee Family constellation Interview date Family I Woman (56), man (56), 1 child April 22, 2021

3.4 Data collection

Both the expert interview and the model case interviews were conducted using the online video meeting platform Zoom. The decision to use an online interaction tool was partly based on recommendations from the Swedish Public Health Agency to limit physical contact (Folkhälsomyndigheten, 2020; WHO, 2021). Further motivation for this decision was to avoid travelling costs and emissions. Meeting via video instead of in person means there is a risk of connectivity issues such as delayed or lagging image or sound. Serious issues of such kind could potentially lead to some reactions or expressions being missed. To minimize this risk as much as possible, each respondent was asked to perform the interview in a place where they could ensure a stable Internet connection. That proved successful, and the result was that no interview was damaged by connectivity issues. The respondents were asked to be seated undisturbed for this time.

The researchers presented case questions with two different nudges to the interviewees to be able to see if the nudges worked and how the reactions were (question 15, 16 and 17, Appendix 2). The case questions could have been designed differently as they brought some unexpected implications to the study and did not give the results the researchers were hoping for. Questions 15 and 16 provided some useful material and were kept for interpretation. Question 17 gave no useful material as the respondents were so strongly influenced by other factors than those that the researchers aimed to investigate, that their responses came to not be about the study topic. Some deeper reflection on these two issues is presented below.

The first case aimed to test the decoy effect. The case consisted of questions 15 and 16, where the interviewees first were presented with two cups of coffee, one small cup and one large cup, and had to choose which one they preferred. In the next question a decoy was planted, a third cup of coffee, where the large cup of coffee from the previous picture now became the middle-sized option instead. In the first part of the case the result was that six out of nine interviewees chose the small cup, and three chose the large cup. In the second part, four out of nine interviewees chose the middle-sized cup, and five interviewees still chose the small cup. The reasons from the model cases for not choosing differently were that they thought the large cup was too expensive, that they did not want more coffee or that the large cup appeared too big. To make this case question more successful the researchers could have chosen another product, such as water or milk, that would not affect the consumers’ opinions as much as coffee did.

Another change that the researchers could have made is to lower the prices as this led the consumers away from the nudge as well.

The second case, question 17, presented pictures of three different types of soap where the intention was to see if the consumer chose the middle one. This was thought as a way to test the middle option bias nudge. Unfortunately, this case did not give any useful results for the researchers, which led to removal of this question. It turned out that the interviewees only focused on the design of the bottles. The only result that came from this question was that most of the men chose the soap to the left, as this looked cheap and functional, and most of the women chose the soap to the right as this looked designer wise most attractive, only one person chose the middle one, this was due to that this bottle was transparent and she liked that. One person did not want to answer the question at first, as she would never purchase plastic soap bottles for sustainability reasons. This result is not useful for this study but could be helpful in other studies. What the researchers could have done differently in this case was to choose another product which is more neutral and where the design of the product would not divide the genders as much as it did. Another change that the researchers would have wanted to implement is prices of the products, as in this case prices might have changed the results somewhat.

3.5 Data analysis

This study has been conducted in multiple languages, Swedish and English. The expert interview and the consumer interviews were conducted in Swedish. This decision was made on the grounds that both authors as well as all interviewees are native to the Swedish language, and this would avoid unnecessary language barriers or misunderstandings. The necessary translation step poses a limitation, no matter where in the process it is placed. Because the authors have a good knowledge of the English language, this was seen as the place where the risk of misinterpretation was the lowest. Hence a decision was made to place the translation on the authors rather than the respondents, which is thought to minimize sources of error as much as possible. The translation was conducted just before the analysis phase, meaning that recordings and transcripts are in Swedish and material for all steps thereafter are in English. To minimize the risk even further, the translation of all quotes that are presented in chapter 4 were externally viewed and approved by a Jönköping International Business School alumnus. Thanks to these actions, the authors do not believe that the study has been hurt in terms of translation or interpretation.

Before the data analysis could take place, the interview recordings had to be transcribed. Depending on the amounts of data, researchers may choose to fully or partly transcribe the recordings (Collis and Hussey, 2014). Because the researchers of this study have been working with an expert interview and with model cases, the amount of recordings was manageable and did not need to be reduced before transcription. Hence, a full transcription of each interview was made.

According to Miles and Huberman (1994), analyzing qualitative data is a three-step process starting with reducing the data, followed by displaying the data, and finishing with drawing conclusions. Because this study involved two different kinds of respondents and interview settings, the data analysis stage has had to differ somewhat between these two. The expert interview had only one respondent, meaning that there was no need to co-organize its transcript with others. This transcript was analyzed by identifying themes of interest that were highlighted in the original transcript. The rest of this section will explain how the transcripts of the model case interviews were analyzed.

One way to reduce data is to restructure it. The data for this study was collected through interviews, meaning that it was at this point arranged in accordance with the interview questions. No theoretical framework was applied for the restructuring of the data, meaning that the researchers let the new data structure emerge during the data collection stage. This resulted in a structure where the most interesting excerpts from each interview were identified, and where these then were restructured into a collected overview of the key excerpts from all interviews. Such excerpts were obtained through using memos, that is, notes of the authors’ comments and reflections. Because the study design in this case was about seeking depth and richness of the data, it was important for the researchers to easily be able to find their ways back into the unreduced data when necessary. This was achieved by marking in the overview which excerpts belonged to which interview.

The next step was to display the data. Depending on the study design and the content of the data, it may be interesting to display the data not only in text. For this study, the constellation of interviews was of particular interest for interpretation as well as for understanding, so the researchers decided to present this information using a table (Table 1). In this table, the model case families were divided into four groups based on age and if they had children or not. This division was a decision that resulted from the identified patterns in the data reduction stage. Moreover, there were two questions from the interviews that the authors decided would be best

presented and interpreted through tables (Table 2 and 3). Beyond these tables, the data has also been displayed using quotations from the model case interviews. Along the process, the data has been analyzed and interpreted, and after conducting all the above steps, the data was ready for conclusions to be drawn.

3.6 Research ethics and data quality

3.6.1 Research ethics

In order to ensure a strong research ethics for this study, the authors have strictly followed the recommendations of Bell and Bryman (2007) and Collis and Hussey (2014). Voluntary participation is one of the most central aspects of research ethics. Study respondents should not feel pressured in any way about taking part or about what they ‘should’ deliver. Participation should, if possible, not be motivated by rewards as this may generate biased results. No such rewards were offered in this study, and the participants were informed that participation is voluntary and that they are free to withdraw at any time should they feel like.

Informed consent is about revealing the study purpose to the participants. This study has an experimental character, suggesting that there must be a balance between information given to respondents before the interviews and some restraint to not risk adventuring the study purpose (Collis and Hussey, 2014). Pre interviews, the respondents were informed that the authors were studying grocery shopping in-store versus online, and that the authors were interested in knowing about their habits and opinions. They were not informed that the authors were looking at nudges in particular. However, this became quite clear to some as the interviews went along, but this was not a problem since interview questions were structured in a specific order, so that when they knew ‘too much’, that was alright. As the two last interview questions were about exposing the respondents to nudges, they all knew our intentions at the end. However, for the expert interview, no such balance was needed since that interview did not have an experimental arrangement, rather it was important for our expert to have the full information in order to provide the best answers.

It is important not to cause the participants any physical or mental harm (Collis and Hussey, 2014). The only risk that was identified about harm for this study was if information was shared inappropriately. Even though the study subject for this research was not of a sensitive kind, one must respect that the participants’ personal information or standpoints should not be revealed.

To ensure this, no mass emails were sent out, only personal ones, and all email and data was protected by passwords that only the researchers of this paper had access to.

All interviewee respondents of this study consented that the interviews would be recorded to enable transcription and thorough studying of the data by the researchers. In line with the European law of GDPR, the recordings and transcripts must only be saved as long as they are of use, which is until the grading of this report is finalized (Riksdagen, n.d.). This was agreed upon with all interviewees. Further, the authors made the decision to anonymize all families as they did not see any usefulness in using their names. Rather they believed it to be easier for the reader to follow the findings, analysis, and discussion if the families were named Family A, Family B, Family C, etcetera. According to Collis and Hussey (2014), ensuring the respondents’ anonymity may contribute to more open and honest answers. However, the family constellations (age and number of children) were not anonymized since this information was important for analysis and interpretation of the results. The case with the expert interview differed from those with the model case families. The expert interview was of a more formal construct, and in this case, there was no need for anonymity to simplify understanding on the part of the reader, nor to entice more honest answers. Mr. Volmerdal therefore was asked to choose if he wanted to be anonymous, but he had no such wish.

3.6.2 Data quality

Although there is a clear definition of what nudging is, the concept is broad and open to multiple interpretations. Further it is used in many different contexts. Since this was identified as a potential source of error, it has been important for the authors to be clear about definitions and implications throughout the report. In terms of this clarity, the authors have attempted to achieve a high level of confirmability by presenting a comprehensive description of the research process, including distinct connections between collected data and analyzed findings (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Because this study has been looking at a concept that is built around human behavior, which in turn is affected from multiple perspectives, triangulation has been a key tool for the authors. Triangulation means acquiring multiple perspectives by using multiple sources and is a practical tool to strengthen credibility (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Peer debriefing, which is a form of triangulation where peers who stand outside of the particular research are called in as advisors, have been applied to this work in two ways. The first of these was the Jönköping International Business School alumni who consolidated the quote translations. The second one was a duo of education programme colleagues who read and

consolidated on the research report during the final stages of its production. It has also been important to collect and document the study data systematically. By the help of the requirements listed in section 3.3.2, and by thoroughly documenting all recordings and transcripts, this study possesses strong dependability according to the recommendations of Miles and Huberman (1994) and Collis and Hussey (2014).

For a study to be of academic interest to others, it must have a certain level of transferability, meaning that the study findings should be generalizable and transferable to similar situations (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Although the research approach has been clearly defined as focusing on model cases, which do not implicate generalizability to the population, the key word here is ‘similar situations’, meaning that the results of this study must be able to be transferred to situations with the same prerequisites as those of the model case families here (Miles & Huberman, 1994). With this in mind, the findings and conclusions from this study are applicable to future studies as long as there are enough circumstantial similarities, and with some adaptations, the study may be reproduced for multiple areas of use. Conclusively, the actions described in this section have altogether contributed to a strong level of research validity.

4. Empirical findings and interpretations

Chapter 4 consists of thorough presentations and interpretations of the empirical findings of this study. The combination of empirical findings with interpretations in this chapter is a choice motivated by the recommendations of professor J. Backman (2016). Starting with an overview of the studied model cases, the chapter then presents the findings arranged in 10 categories emerged from the consumer interviews, including connections to previous knowledge.

Based on one expert interview and 9 model cases from consumer interviews the authors have concluded the following findings as an attempt to identify opportunities and shortages within nudges in online environments as a way to answer the two research questions for this study.