International Relations

Dept. of Global Political Studies Bachelor programme – (IR 61-90) – IR103L 15 credits thesis

The European Environment Agency in

International Relations

From a Passive Respondent to an Active Participant and

Influencer in International Relations

Abstract

Unlike environmental non-governmental organisations and other knowledge producers, the European Environment Agency (EEA) seems to attract seemingly little academic interests among scholars of international relations. With this in mind, this thesis seeks to discuss how knowledge institutions such as the EEA may be seen as active participants in IR, while simultaneously seeking to extend academic discussion considering the EEA itself. More explicitly, and in order to narrow down its focus, this thesis is driven by a research question: what is the role of the EEA in policymaking and monitoring done by the European Commission? This thesis adopts social constructivism as its theoretical framework while building on data obtained through both a quantitative content analysis and semi-structured interviews. Both of these methods are used to identify as what kind of a knowledge producer the EEA is institutionalised as a part of the policymaking-complex of the Commission. This thesis finds that the EEA is best understood as an autonomous actor in IR which’s role is to legitimise and support environmental policymaking of the Commission rather than function as an active policymaker itself.

Key words: European Environment Agency; EEA; European Commission; Environmental Policymaking; European Union; Directorate-Generals.

List of Abbreviations

CAAR Consolidated Annual Activity Report Commission European Commission

DG Directorate-General

DG AGRI DG for Agriculture and Rural Development DG CLIMA DG for Climate Action

DG ECHO DG for Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection DG ENERGY DG for Energy

DG ENTR DG for Enterprise

DG ENV DG for Environment

DG ESTAT Eurostat

DG GROW DG for Internal Market, Industry Entrepreneurship DG JRC DG for Joint Research Centre

DG MARE DG for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries DG MOVE DG for Mobility and Transport

DG NEAR DG for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations DG REGIO DG for Regional and Urban Policy

DG RTD DG for Research and Innovation DG SANTE DG for Health and Food Safety EEA European Environment Agency

EIONET European environment information and observation network

EU European Union

IR International Relations

Table of Contents

1. Introduction 1

2. Theoretical and Contextual Framework 4

2.1. The EEA and the DG Environment 4

2.2. Social Constructivism 6

2.3. Social Learning 6

2.4. Sociological Institutionalism 7

2.5. Further Contextualisation 9

3. Methods 11

3.1. Quantitative Content Analysis and the CAARs 12

3.1.1. Data Selection 12 3.1.2. Data 13 3.1.3. Coding 14 3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews 15 3.2.1. Conducting Interviews 16 3.2.2. Interviewee Selection 16 3.2.3. Data Reduction 18

4. Quantitative Content Analysis: Key Partners and Role 19

4.1. Key Partners 19

4.2. Role 21

4.3. Discussion of the Findings: Quantitative Content Analysis 23

5. Semi-Structured Interviews 25

5.1. Autonomy 25

5.2. Dependencies 26

5.3. Role of the EEA: Commission 27

5.4. Role of the EEA: the DGs 30

5.5. Discussion of the Findings: Semi-Structured Interviews 31

6. Conclusion 33

7. Bibliography 35

1. Introduction

The European Commission (Commission) has traditionally held a monopoly over two functions: drafting European Union (EU) legislation and enforcing the implementation of the EU legislation through monitoring its implementation by member states of the EU (Selin and VanDeveer 2015). With this in mind, Hofmann (2019: 351) suggests that the Commission has sought to incorporate EU agencies and non-state actors into these two functions since the early 2000’s. In fact, during the past few years some of the high-ranking officials of the Commission has voiced their support for increasing the involvement of EU agencies and non-state actors in the working processes of the Commission (Jevnaker and Saerbeck 2019: 60; Hofmann 2019: 343; Bürgin 2018). However, the role of these actors in the two functions of the Commission remain a matter of academic debate (Holzinger, Knill and Schäfer 2016; Metz 2014; Moodie 2016; Newell, Pattberg and Schroeder 2012; Newing and Fritsch 2009; Newing and Koontz 2014; Trondal, Murdoch and Greys 2015). Nevertheless, policymaking of the Commission can be seen having a direct influence on international negotiations taking place within the European Council and Parliament (Selin and VanDeveer 2015). Therefore, understanding evolving dynamics between the Commission and EU agencies becomes a matter of importance for fully understanding processes underlying environmental policymaking of the EU and engagement in environmental international relations (IR).

This thesis focuses on the European Environment Agency (EEA). In simple terms, the EEA is a formally autonomous EU agency and knowledge institution which functions simultaneously as a network point between different societal actors and institutions, from the EU Parliament to individual researchers (Martens 2010). However, from the very beginning the role of the EEA in policymaking of the EU has been unclear: the creation of the EEA in 1990’s was characterised by uncertainty for who’s purposes the EEA was created for, what the role of the EEA in the EU policymaking should be, and if the EEA is in fact even an autonomous institution (Zito 2009; Martens 2010). Motivated by this puzzle, this thesis is driven by a following research question: what is the role of the EEA in policymaking and monitoring done by the Commission? This thesis finds that the EEA is best understood as an autonomous actor in IR which’s role is to legitimise and support environmental policymaking of the Commission rather than function itself as an active policymaker.

This thesis builds on three distinguishable strands of constructivism which commonly perceive reality as socially constructed and translating into empirical forms through interaction:

social constructivism, sociological institutionalism and social learning (Saurugger 2013; Wood 2015). This thesis adopts social constructivism as its theoretical framework.

The Commission has a number of sub-institutions known as Directorate-Generals (DGs). The underlying commonality between the engaged scholarship focusing on the EEA is that it focuses primarily, if not exclusively, on the relationship between the EEA and the DG Environment (Martens 2010; Zito 2009; Jevnaker and Saerbeck 2019). This thesis departures from previous scholarship by arguing that in order to better understand the role of the EEA it becomes necessary to move beyond the immediate relationship the EEA may be seen having with its parent institution, the DG Environment. Instead, this thesis seeks to demonstrate that in order to provide a meaningful answer to the research question it becomes necessary to focus on the underlying dynamics between the EEA and Commission but also DGs in plural. Because the impact of agencies is rarely acknowledged by IR scholarship, this thesis contributes to IR scholarship by extending discussion considering the relationship between international institutions and agencies, and more explicitly between the EEA and Commission. Consequently, by treating the EEA as an active participant in IR, this thesis seeks to stimulate discussion considering social relevance of environmental knowledge institutions in EU environmental policymaking and engagement in environmental IR.

This thesis begins by contextualising the formal institutional relationship between the EEA and Commission through lenses provided by previous scholarship. This part of the theoretical discussion suggests that even though the EEA does not possess a legal claim to be included into the policymaking done by the in-house technocrats of the Commission, in the framework of social constructivism it is capable of practising influence through sustained communication (Ahmed and Potter 2013). Then, theoretical section focusing on social learning is used to provide a theoretical foundation for understanding how the EEA may be seen becoming an active participant in IR. This is done by building on Prince (1994a: 29, 33) who theorises that when dependencies arise between an actor and international institutions the former too becomes an actor in IR. Discussion considering sociological institutionalism on the other hand invites this thesis to suggest that the role of the EEA can be determined by seeking to understand how its role is (in)formally institutionalised by the Commission (Saurugger 2013; Selin and VanDeveer 2015; Martens 2010). After the theoretical discussion, methods section is used to introduce a multi-method approach for answering the research question driving this

builds on data obtained through semi-structured interviews, conducted with some of the staff members of the EEA. The interviews are used to both to cross reference the findings of the quantitative part of the research but also to shed light to the thematic areas discussed throughout this thesis, namely to the political autonomy of the EEA and potential dependencies between the EEA and Commission.

2. Theoretical and Contextual Framework

As an institution, the Commission is a legally autonomous institution which is responsible for designing EU directives, regulations and laws which are then directed to the EU Council and Parliament for further processing. Furthermore, the Commission is also responsible for monitoring that member states of the EU implement EU policies (Selin and VanDeveer 2015; Hofmann 2019). For the sake of simplicity, this thesis refers to these two functions from now onwards as ‘policymaking’ and ‘monitoring.’ What this legal autonomy means is that the Commission, but also its administrative branches known as the DGs, are not formally obligated to recognise knowledge produced outside of their in-house technocratic committees (Gornitzka and Sverdrup 2011). Therefore, it can be said that due to its legal autonomy the Commission as a whole can be treated as the institutional gatekeeper of the legislative framework of the EU. Despite its size as one of the biggest environmental agencies in Europe, the EEA attracts seemingly little academic interest among the scholars of IR. At the same time, the study of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and other knowledge-providers have captured the attention of scholars of social science in more general. This is almost paradoxical if taking into consideration that just like NGOs and non-state actors, the EEA can be treated as an autonomous actor, legally separated entity from the in-house technocratic committees of the Commission (Zito 2009). Yet, the EEA is rarely acknowledged as an actor in IR despite the fact that it can be seen having its own political agenda to stimulate an EU wide ‘transition towards a low-carbon, resource-efficient and ecosystem-resilient society by 2015’ (EEA 2015). With this in mind, in order to provide a theoretical framework for understanding how the EEA may be seen becoming an actor in IR, this thesis draws from three groups of constructivist scholarship used commonly to study dynamics between international institutional and knowledge-providers: social constructivism, social learning and sociological institutionalism. Before discussing each of the named schools of thought individually, the theoretical section continues next by contextualising the relationship between the EEA and the DG Environment.

2.1. The EEA and the DG Environment

The EEA is an EU agency which became operational in 1993 after a join initiative made by the Commission leadership and the European Parliament in 1989 (Zito 2009: 1229-1230). However, Martens (2010: 884-5) points out that there was no clear consensus among the

Zito (2009: 1229-31, 1234-6), beyond its original task of gathering and analysing environmental data, European Council Regulation 933/1999 empowered the EEA to draft ‘sound and effective environmental policies’ or assessments based on its objective assessment of the correlations between political and ecological trends. Both Martens (2010: 887) and Zito (2009: 1230) point also out that the EEA is a network agency, and that one of its functions is to animate its partnership network known as the ‘European environment information and observation network’ (EIONET). Hence, and in simplified terms, the EEA is both a knowledge-institution which simultaneously functions as a network point between different societal actors and institutions, from the EU Parliament to individual researchers.

The EEA is institutionally part of the DG Environment, and it is perhaps due to this institutional closeness that the EEA passes under the radar of some of the scholars of IR (Martens 2010). While building on data obtained through semi-structured interviews and public documents, both Martens (2010: 888) and Zito (2009: 1235) demonstrate that the dynamics between the EEA and the DG Environment are indeed complex: the two institutions are legally autonomous from one another, yet they share the same budget. However, while Martens (2010: 888) and Zito (2009: 1235) raise rightfully a notion that this budgetary interdependence may introduce tensions between the two institutions, the respective scholarship does not display convincing evidence that this interdependence would compromise the ability of the EEA to formulate its own political agenda. Therefore, because the EEA may be seen as an autonomous entity, capable of setting its own political agenda, this raises a question what is the role of the EEA in the policymaking and monitoring done by the Commission? As the work done by the Commission influences directly international negotiations taking place within the European Council and Parliament, understanding dynamics between the EEA and Commission becomes a matter of importance for fully understanding processes underlying environmental policymaking of the EU and engagement in environmental IR (Selin and VanDeveer 2015). Because the EEA is formally autonomous from the DG Environment it does not have the legal claim to be included into the policymaking done by the in-house technocrats of the Commission. Consequently, as a subject of a study, the EEA resembles environmental NGOs which are rarely legally entitled to participate in policymaking processes of international institutions, but which are widely considered as actors in IR. With this in mind, Ahmed and Potter (2013: 14-5) suggest that social constructivism proves a useful theoretical approach for ‘how NGOs influence international politics because it is concerned with the exercise of power through communication.’ In other words, and as discussed next, communication between actors may not always appear political but dynamics created by it over time may well be.

2.2. Social Constructivism

In the margins of this thesis, social constructivism is best understood as a theoretical umbrella under which the two other theories discussed in this thesis can be placed to. While building on all three strands of constructivism, this thesis adopts social constructivism as its theoretical framework. In the words of Söderbaum (2016: 86, drawing from Christiansen et. al. 1999): ‘social constructivist approach emphasizes the mutual constitutiveness of structure and agency, and pays particular attention to the role of ideas, values, norms and identities.’ Consequently, social constructivism can be seen as a broad philosophical framework for discussing social reality in which actors operate in, but also for recognising that actors’ mode of behaviour may change based on attitudes, norms, ideas and identities they hold (Söderbaum 2016; Risse 2009). While building on social constructivism, Ahmed and Potter (2013) discuss the role of NGOs in IR in their book-length collection of historical case studies. When reflecting the content of these case studies with one another, it seems that NGOs which do not have a legal claim to be included into the policymaking processes of international institutions practice their influence through communication (Ahmed and Potter 2013). In fact, Ahmed and Potter (2013: 14-5) point to another important dimension of communication, time: ‘when people, governments, or non-state actors communicate with one another over time, that communication can create common understandings of rules and behaviour.’ In other words, sustained communication increases the possibility that actors are able to persuade their counterparts to take into consideration specific set of variables in their policymaking. With this in mind, the concept of ‘influence’ is best understood in the margins of this thesis as the ability of an actor to present ideas that the recipient is likely to find appealing (Ahmed and Potter 2013).

This thesis extends the theoretical framework discussed in this section also to the EEA (Ahmed and Potter 2013; Risse 2016; Söderbaum 2016). Therefore, even though the EEA does not possess a legal claim to be included into the policymaking done by the in-house technocrats of the Commission this thesis considers that the EEA it is capable of practising influence through sustained communication (Ahmed and Potter 2013: 14-5). Consequently, in this light the role of the EEA shifts from being a passive respondent to an active participant and influencer in IR (Prince 1994a).

of social learning is ‘socialisation’ which according to Schimmelfenning (2000: 110) refers to a process in which actors internalise beliefs or practices. This process is captured more explicitly in the words of Saurugger (2013: 894): ‘[t]hrough continuous interaction, actors in groups of actors share a number of common values, which, in turn, influence their positions in decision-making processes.’ In this regard, social learning builds on the social constructivist understand that communication is best understood as a discussion rather than as a process of advocating fixed preferences, meaning that actors learn through sustained communication to adjust their opinions based on available information (Ahmed and Potter 2013; Saurugger 2013). Therefore, and by drawing from Prince, Finger and Manno (1994: 228), environmental NGOs and agencies interacting with international institutions may become agents of social learning by linking ‘biophysical conditions with political concerns.’

Every theory has its shortcomings. One of the shortcomings of social learning is that it does not provide a standardised conceptual framework for explicitly measuring the impact communication has on actors’ behaviour (Zito 2009: 1227-8; Prince, Finger and Manno 1994: 228). Whereas this thesis is driven by a question what the role of the EEA is in the policymaking and monitoring done by the Commission, a question which is arguably best answered by focusing on standards and patterns of interaction between the EEA and Commission, highlighting this pitfall may appear arbitrary. However, this pitfall becomes a matter of relevance because it exposes the process of socialisation open for criticism for not being able to prove that the output of the EEA can actually be seen influencing the Commission. With this in mind, Prince (1994a: 29, 33) suggest that ‘NGOs become independent actors on the international scene when mutual dependencies arise among key actors.’ This thesis adopts this classification and extending it also to the EEA. Consequently, while building on the scholarship of Prince (1994a: 29, 33), this thesis considers that under circumstances in which the EEA and Commission can be seen mutually dependent the output of the EEA, normatively speaking, influences the work done by the Commission.

2.4. Sociological Institutionalism

Lines between different strands of constructivism are at times overlapping and at first they may seem hard to distinguish from one another. Hence it is worth briefly clarifying the nature of sociological institutionalism and how it proves helpful for understand the role of the EEA in the policymaking-complex of the EU. With this in mind, in the context of this thesis sociological institutionalism can be broken into two major components. First, institutional

behaviour is taken to be motivated by an evolving normative pressure created by actors’ shared understanding of appropriateness (Saurugger 2013: 893). Secondly, dominant societal norms can be identified by focusing on a process known as institutionalisation: instances in which norms can be seen becoming part of institutional structures and practices (Goetze and Rittberg 2010: 38).

The Commission has a standardised mechanism for incorporating representatives of different societal interests with an advisory status into its policy preparation processes, and this mechanism is sometimes known as the EU Comitology system (Wood 2015: 13). As the Comitology system is arguably a mechanism designed to (re)legitimise policymaking processes of the Commission (for context see Wood 2015; Field 2013; Moodie 2016), this mechanism has captured the attention of some of the scholars of social science who seem to follow closely the logic of sociological institutionalism. While there are no legally binding quotas regulating the composition of the Comitology expert groups, this group of scholars rely commonly on quantitative research methods while seeking to understand which societal interests are being represented in these expert groups and what is their role in them (Christensen 2015; Vikberg 2019; Metz 2014; Gorniztka and Sverdrup 2008; 2011; 2015). To put differently, based on the patterns of expert group composition, this group of scholarship seeks commonly to identify what type of norm dominates the process of composing Commission expert groups. Even though the analytical focus of this group of scholarship is not on the EEA, it invites this thesis to argue that the role of the EEA in the policymaking-complex of the EU can be determined by focusing to understand how the role of the EEA is (in)formally institutionalised by the Commission (Ison, Collins and Wallis 2015).

As an EU agency, the EEA is arguably already part of the formal institutional structure of the EU and Commission. However, because the EEA does not have the legal claim to be included into the policymaking done by the in-house technocrats of the Commission, its ability to practice its influence in relation to the Commission is tied to its access to institutional practices (Goetze and Rittberg 2010). With this in mind, as mentioned above this thesis builds on the broader constructivist assumption that social reality evolves in accordance attitudes held by actors occupying it (Risse 2009). Consequently, this thesis considers that the analyses conducted by Martens (2010) and Zito (2009) a decade earlier cannot be respectfully be seen providing an up-to-date insight to the institutional role of the EEA.

2.5. Further Contextualisation

Environmental policymaking of the EU is a uniquely complicated political exercise both politically and institutionally. First, as a political process environmental policymaking blurs lines between different societal interests traditionally dealt in isolation from one another and, for example, Steinbach and Knill (2017: 430) suggest that economic and environmental development can be seen stimulating political tension between one another (Driessen and Glasberg 2013). Juntti, Russell and Turnpenny (2009: 208) also point out that at times environmental ‘policies seem to fall short or indeed directly contradict what the available scientific knowledge suggests is required.’ Therefore, and as also noted by Haas (2004: 572), just like any other form of societal interest, scientific knowledge has become politicised. These complex dynamics are captured more explicitly in the words of Bulkeley and Mol (2003: 144) who point out that ‘non-participatory forms of [environmental] policymaking are defined illegitimate, inefficient and undemocratic both by politicians and stakeholders themselves.’ Consequently, this raises the normative question of which actors are suitable for participating in environmental policymaking and at which stages of working processes they should participate in, a question raised collectively by the scholarship discussed in relation to sociological institutionalism (for context, see section 2.4) (Christensen 2015; Vikberg 2019; Metz 2014; Gorniztka and Sverdrup 2008; 2011; 2015).

Secondly, environmental policymaking of the EU is also a complicated institutional exercise. On one hand, environmental policymaking of the EU may be seen increasingly de-centralised, and for Wurzel, Liefferink and Torney (2019: 2) the ‘shift away from a top-down climate governance approach embodied in the 1997 Kyoto Protocol.’ On the other hand, Trondal and Jeppensen (2008: 427) argue based on their institutionalist large-n study that a ‘majority of EU-level agencies have incompatible horizontal organisational structures vis-a-vis the Commission.’ To put differently, despite the recorded trend of increasing inclusiveness in environmental policymaking of the EU, this development seems to have a limited impact on the formal institutional structures of the environmental policymaking (Hofmann 2019; Wurzel, Liefferink and Torney 2019).

The development of the environmental policymaking of the EU would seems to have had a limited impact on the legal autonomy of the Commission (Steinbach and Knill 2017; Migliorati 2020). What this means is that the Commission remains as the institutional gatekeeper of environmental legislation of the EU, making it a relevant vocal point for discussing environmental policymaking of the EU. However, before moving on discussing the methods

of the following research, it becomes necessary to address a question: which of the institutional levels can be considered as the most suitable reference point for studying the relationship between the EEA and Commission. In order to answer the research question driving this thesis, namely what the role of the EEA in the work done by the Commission is, it becomes arguably necessary to focus both on interaction between the EEA and Commission, but also with DGs in plural. This argument builds on the scholarship of Jevnaker and Saerbeck (2019) who build on data obtained through semi-structured interviews while seeking to understand how information provided by the EEA is being used by the Commission. Consequently, Jevnaker and Saerbeck (2019: 65) find that about ‘70% of Commission staff at the administrative level working on issues related to the environment and climate reporting [are] using information provided by the EEA,’ simultaneously suggesting that information provided by the EEA spearheads itself into more than one of the DGs. However, none of the engaged scholarship clarifies to which of the DGs the EEA actually provides information to (Martens 2010; Zito 2009; Jevnaker and Saerbeck 2019). Therefore, this thesis argues that the role of the EEA is best understood by first identifying with which of the DGs the EEA sustains communication with and then by seeking to understand how its role is being institutionalised both in relation to the DGs and to the Commission as a whole.

In summary, the scholarship discussed throughout this theoretical section invites the following analysis to focus on a number of interrelated points. First, and as suggested above, the role of the EEA is tied to (in)formal institutional practices, inviting the following analysis to focus on the process of institutionalisation (Goetze and Rittberg 2010). However, in order to be able to analyse the process of institutionalisation it becomes first necessary to identify which of the DGs the EEA interacts with (Martens 2010; Zito 2009; Jevnaker and Saerbeck 2019). Secondly, as this thesis argues that the EEA is best understood as an autonomous actor in IR it becomes also necessary to focus on the thematic areas of autonomy and interdependence of the EEA. Consequently, as the ability of the EEA is taken to be tied to its access to institutional practices, the following analysis draws the analytical attention on patterns of communication which under the adopted theoretical framework is expected to lead to a process of socialisation.

3. Methods

This thesis is driven by a research question: what is the role of the EEA in policymaking and monitoring done by the Commission? This thesis departures from the scholarship of Martens (2010) and Zito (2009) as it expands its analytical focus from analysing only the relationship between the EEA and the DG Environment. By doing so, this thesis builds on the scholarship of Jevnaker and Saerbeck (2019: 65) when arguing that in order to understand the role of the EEA it becomes necessary to study relationship between the EEA and Commission but also between the EEA and DGs in plural. This thesis projects that the EEA is best understood as an autonomous actor in IR which is capable of influencing policymaking of the Commission through sustained communication.

This thesis builds on a multi-method approach and, therefore, the research design of this thesis can be divided into a quantitative and qualitative section. In the first part of the analysis this thesis carries out a quantitative content analysis focusing on Consolidated Annual Activity Reports (CAARs) of the EEA. This is done for two reasons. First, the quantitative content analysis is conducted in order to identify which of the DGs the EEA may be seen communicating regularly with. Secondly, as briefly pointed out in the theoretical section of this thesis, as a knowledge institution the EEA produces different types of outputs, namely analyses, assessments and co-created products and documents. Therefore, by focusing on patterns of communication it becomes possible to identify through which type of communication the EEA may be seen predominantly practising its influence, but also to understand as what kind of a knowledge producer it is institutionalised as a part of the policymaking-complex of the Commission.

The second part of the analysis builds on data obtained through semi-structured interviews which were carried out during the spring of 2020 with four of the former and current staff members of the EEA. This qualitative research is also conducted for two reasons. First, the interviews are conducted in order to cross reference the findings of the quantitative part of the research. Secondly, the interviews shed light to the thematic areas discussed throughout this thesis, namely to the political autonomy of the EEA and potential dependencies between the EEA and Commission. Also, the qualitative part of the research enables this thesis to provide further clarify to the question what the role of the EEA is in environmental policymaking of the Commission and the EU. Due to its nature as a multi-method research the following analysis produces two sets of findings. Therefore, findings of the analysis are also discussed as two separated collections.

3.1. Quantitative Content Analysis and the CAARs

This part of the analysis serves a triple function. First, it is used to identify which of the DGs the EEA may be seen communicating regularly with. Secondly, in the frames of the adopted theoretical framework the EEA may be seen practising influence through sustained communication (Ahmed and Potter 2013; Saurugger 2013). Therefore, this part of the analysis provides an insight for understanding through what type of communication the EEA may be seen primarily practising its influence, and which of the DGs it is most likely to be engaged in socialisation with. Thirdly, this part of the analysis is used to shed light to the question as what kind of a knowledge producer the EEA is institutionalised as a part of the policymaking-complex of the Commission or, in other words, what the role of the EEA seems to be.

For Riffe, Lacy and Fico (2005: 44) ‘[q]uantitative content analysis is most efficient when explicit hypotheses or research questions are posed.’ In the case of this thesis, these questions are with which of the DGs the EEA sustains communication with, and what type of communication dominates this relationship. Halperin and Heath (2017: 346) define quantitative content analysis as an obstructive form of textual analysis which can be used to ‘count the number of times a particular word, phrase, or image occurs in a communication.’ Also, as an obstructive research method quantitative content analysis is replicable and has a high internal validity. Naturally, this internal validity becomes at the price of external validity. For example, the selected research method provides a limited insight for understanding how the output of the EEA is being taken into consideration by the DGs in their final decision-making. However, it is worth highlighting that before such question can be effectively addressed it becomes first necessary to identify those DGs the EEA sustains communication with, and this question is meaningfully answered by using a quantitative content analysis.

3.1.1. Data Selection

The relationship between the EEA and Commission is a challenging subject to understand from outside of it. Despite the notion raised by Jevnaker and Saerbeck (2019), namely that information provided by the EEA is actively used by many of the Commission staff members working with environmental issues, the EEA is rarely named in communications between the Commission, Parliament and Council, or in other public documents issued by the Commission. In this regard, public documents issued by the Commission, even those with EEA relevance,

The EEA produces annually a number of public documents which are made available on the EEA website. Despite its high annual output of public documents, very few of the EEA documents address directly its relationship with its cooperation partners. Simultaneously, while the EEA has many areas of expertise, it also issues different type of documents which’s content is often irregular and variates from document to document. An exception to these rules are annual activity reports, or CAARs. These reports provide an overview of the annual output of the EEA: what activities and documents it has produced during the past year, but also who according to the EEA are key partners or, respectfully, clients of these activities and documents (EEA 2016; 2017; 2018; 2019a). Therefore, the CAARs may be seen representing the most comprehensive datasets available for understanding which of the DGs the EEA sustains communication with and what type of communication dominates the relationship between them.

3.1.2. Data

The following analysis focuses on the CAARs which are made publicly available on the EEA website. All together four documents are being analysed, and the interval these documents represent are activities carried out between 2015 and 2018. The documents are a form of primary data and they have been selected for three reasons. First, they present the most up-to-date data available considering the activities carried out by the EEA. The CAARs are published annually in June, meaning that the CAAR report for the year 2019 falls outside of the timeframe set for this thesis. Secondly, the EEA has carried out an internal reporting-style reform between the CAAR reports for 2014 and 2015, and this reform has influenced both the content of these reports but also how they are written. Consequently, CAARs published before 2015 are excluded from the following analysis because the two schools of documents cannot be coded by using the same protocol nor directly compared with one another without compromising the internal validity of the research. Thirdly, as the CAARs provide an overview of the annual activities of the EEA they may be considered to represent one of the most comprehensive set of data available for quantifying the frequency of interaction taking place between the EEA and DGs. Therefore, despite the shortness of the analysed interval it can be considers sufficient for providing an insight to the question which of the DGs the EEA may be seen communicating frequently with.

3.1.3. Coding

The CAARs represent a set of primary data. Because the CAARs can be seen as a collection of management and output related information, the focus of the analysis is narrowed down to specific sections of the reports. With this in mind, this thesis draws from Riffe, Lacy and Fico (2005: 69) while creating its own coding protocol. Consequently, the CAARs as a whole are treated as sampling units, while sections 1.1-1-3 of the CAARs are treated as recording units. This is because together these sections may be seen representing the annual output of the EEA (for context see CAAR 2016; 2017; 2018; 2019a). In fact, each section can be seen representing a thematic area of the EEA’s expertise: ‘1.1 Informing policy implementation’ (analysis and data related activities); ‘1.2 Assessing systemic challenges’ (assessments related activities); and ‘1.3 Knowledge co-creation, sharing and use’ (co-creation activities) (EEA 2017: 2; EEA 2018: 20; EEA 2019a: 68, 79). Within these recording units, the analysis focuses on tables summarising the annual outputs of the EEA. Context units within these tables are the type of output and the associated key partners, namely the DGs (Riffe, Lacy and Fico 2005: 69). Units of an analysis are different types of output of the EEA, namely documents and activities. Because the EEA produces different types of output the following research relies on open coding. Each of the different types of output is assigned a numerical value and, based on the conducted coding protocol, the EEA may be seen producing twelve different types of outputs, namely documents and activities (for the coding table, see Appendix 1). In the next stage of the coding protocol, each of the output of the EEA is place into a category. These categories are also created also by using open coding. As this part of the analysis is interested to understand with which of the DGs the EEA may be seen communicating with, each of the DGs is used as a category of their own. Finally, by following this coding protocol, the sampling units (sections 1.1-1.3 of the CAARs) are coded manually. By following the logic of Riffe, Lacy and Fico (2005: 85), each of the units of an analysis is located into the sampling unit and assigned 1 (one) and 0 (zero) depending whether they associate a given DG as their key partner. At this point it is worth emphasising that discussing the nuanced differences between the different types of units of an analysis fall outside of the immediate focus of this research. However, by remaining sensitive towards the fact that the EEA produces different types of outputs enables the research to identify sustained patters of communication materialising at any level of formal interaction between the institutions. As such, quantitative content analysis

what kind of a knowledge producer it is institutionalised as a part of the policymaking-complex of the Commission.

3.2. Semi-Structured interviews

Despite being one of the biggest environmental agencies within Europe, obtaining qualitative data considering the relationship between the EEA and the Commission remains difficult. On top of being seemingly absent from many of the documents issued by the Commission or the DGs, the EEA is rarely addressed in media or in public speeches. Simultaneously, accessing information considering the meetings of the Commission expert groups (discussed in the section 2.4 of this thesis) in which the EEA participates in is not made consistently available for the general public. In other words, the relationship between the EEA and its partners remains a black box.

Scholarship focusing on the EEA as an actor relies commonly on semi-structured interviews as a method of data collection (see Martens 2010; Zito 2009; Jevnaker and Saerbeck 2019). Halperin and Heath (2017: 289) define semi-structured interviews as a method of data collection which enables researcher to obtain both factual information but also an insight to people’s experiences. Rowley (2012: 262) in return considers semi-structured interviews especially useful when the research seeks to shed light to a topic that has not been yet studied extensively, a criterion which the relationship between the EEA and Commission arguably fulfils. Therefore, as the relationship between the EEA and its cooperation partners remains a black box, this thesis builds on the previous scholarship by agreeing that generating qualitative data considering the relationship between the EEA and Commission is done best through semi-structured expert interviews (Martens 2010; Zito 2009; Jevnaker and Saerbeck 2019).

As pointed out in the theoretical section of this thesis, the EEA attracts seemingly little academic interest among the scholars of IR. In the absence of extensive body of scholarly literature considering the relationship the EEA and Commission, using close ended questions would effectively restrict the research from generating new information about the subject-matter at hand (Rowley 2012; Jacob 2012: 3). Because this thesis focuses primarily on the relationship between the EEA and Commission, using semi-structured interviews can be considered as the most suitable form of interview for exploring the subject-matter as it provides the opportunity to structure interviews around specific themes and topics, and by doing so generate new information (Christopher 2015: 84).

3.2.1. Conducting interviews

All together four semi-structured interviews took place during the spring of 2020 and each of the interviews lasted between 25-70 minutes. The interviews followed a series of standard questions created for the purposes of this thesis, and the questions included into the interview guide were complemented by follow-up questions as the interviews progressed. The benefit of using an interview guide is that it allows interviewee to structure interviews around specific themes and topics without compromising the possibility of respondents to reflect their own understanding and professional experiences (Halperin and Heath 2017: 285-300). With this in mind, the interview questions were designed to invite the interviewees to focus broadly on the relationship between the EEA and Commission, and the EEA and DGs. Because the focus of this thesis is on the relationship between the EEA and Commission some of the interview requests were originally met with conservative attitudes. Therefore, the interview guide was provided in advantage in order to give interviewees the possibility to examine the questions before hand. The interviews were conducted via telephone and consent of participation were collected electronically. In order to ensure the quality of the analysis, the interviews were recorded and later transcribed into a textual form (Halperin and Heath 2017: 299-300).

The conducted interviews have two shortfalls worth discussing. First, due to the small population size this thesis remains reluctant to make extensive generalisations based on the made findings. However, because the aim of this thesis is not to generate a theory that would be applicable to other institutional contexts, the number of interviews can be considered justified as they provide an insight for better understanding the institutional relationship between the EEA and Commission (Rowley 2012: 269). Secondly, and as pointed out by Halperin and Heath (2017: 286), conducting telephone interviews does not enable the author to control the circumstances in which the interview takes place nor obtain useful information through observing the interviewees body language. However, due to unforeseen travel restrictions created by an ongoing Covid-19 pandemic the original plan of conducting face-to-face interviews needed to be replaced, and telephone interviews were selected as a form of interviewing because they provide the possibility to pose follow-up questions during the interview.

selected as an interviewee based on their common area of expertise, namely that they have both an overview and experience from working with the DGs. Each of the interviewees have been part of the EEA between 4 and 26 years.

Rather than interviewing staff members of the Commission, the following research focuses on information obtained through semi-structured interviews with some of the staff members of the EEA. This selection can be justified for two reasons. First, Jevnaker and Saerbeck (2019) have recently shed light into the question how information provided by the EEA is taken into consideration by some of the staff members of the Commission who are working with issues related to environmental matters. Therefore, rather than duplicating efforts made by previous scholarship, interviewing EEA staff members enables this thesis to produce novel data. To put more elaborately, interviewing staff members of the EEA provide an insight for understanding how some of the staff members understand their role relation to policymaking done by the Commission and DGs. Also, as the main focus of this research is on the EEA, interviewing staff members of the EEA seems logical as they can be expected to hold more comprehensive insight considering the role of the EEA in the policymaking-complex of the EU than their Commission counterparts.

Secondly, as discussed both in the introduction of this thesis and in relation to sociological institutionalism, the Commission has sought to increase the role of EU agencies and non-state actors in its policymaking processes since 2000 (Hofmann 2019). With this in mind, Halperin and Heath (2017: 290) note that the likelihood of an interview effect increases in situations in which the respondents might feel that they are expected to give a socially acceptable answer to an interview question. Halperin and Heath (2017: 294) do suggest that the interview effect can be controlled to some extend in face-to-face interviews, however due to the travel restrictions created by an ongoing Covid-19 pandemic conducting interviews with staff members of the Commission remains a subject suitable for future research. In other words, in comparison to their Commission counterparts, this thesis argues that staff members of the EEA are likely to be less prone to overestimate the role of the EEA in relation to the policymaking done by the Commission. While the possibility of interview effect can be fully excluded under rare circumstances Halperin and Heath (2017: 290) suggest that by granting interviewees an anonymity they are ‘more likely to produce honest responses than those that identify the respondent.’ Therefore, interviewees are given a full anonymity.

3.2.3. Data Reduction

In order to reduce the amount of information obtained through semi-structured interviews into a more manageable quantity, the interviews were coded based on broad themes discussed in the theoretical section of this thesis. The themes focused are the EEA’s political autonomy, dependencies between the EEA and Commission, and the role of the EEA. Also, because using semi-structured interviews enabled interviewees to reflect their experiences and understandings of the subject-matter, an additional theme became included into the coding scheme during the analysis, namely networking activities of the EEA. This theme is embedded into the analysis as it can be seen shedding light to the questions what the role of the EEA is in relation to both the Commission and EU environmental policymaking.

Even though data obtained through semi-structured interviews can be analysed systematically by organising the data according to specific themes and then studied to identify for patterns of explanations, which increases the internal validity of the research, the analysis cannot be completely separated from the researcher’s subjectivity (Halperin and Heath 2017: 304-306). However, and as articulated by Christensen (2015: 144), even though qualitative research may be seen shadowed by the question of internal validity it remains important mechanism of generating new information. Therefore, as the focus of this research is empirical rather than theoretical, namely it focuses on identifying patterns of practices and patterns of information exchange between the EEA and Commission, the interviews can be expected to generate meaningful and valid insights for understanding the role of the EEA.

4. Quantitative Content Analysis: Key Partners and Role

In the margins of this thesis the EEA can be seen having two types of primary functions and three thematic areas of expertise. Based on the engaged literature, the two functions of the EEA are 1) operating as a network point between different societal actors and 2) collecting environmental data (Zito 2009: 1229-31, 1234-6). However, as discussed in the theoretical section of this thesis, circumstances surrounding the creation of the EEA was characterised by uncertainty for who’s purposes the EEA was created for, and what the role of the EEA in EU policymaking should exactly be (Zito 2009; Martens 2010). Therefore, as the EEA is not formally required to constrain its interaction only to its parent DG, the first part of the quantitative content analysis begins by discussing which of the DGs the EEA interacts with. Based on the analysed CAARs, the EEA has three thematic areas of expertise. First, section 1.1, ‘[i]nforming policy implementation,’ refers to a process of combining, analysing and communicating collected data sets (EEA 2016: 10; Interview 3). Secondly, section 1.2, ‘[a]ssessing systemic challenges,’ refers to a process of actively tracking trends between ecological conditions and implemented policies (EEA 2017: 51; Interview 3). Thirdly, section 1.3, ‘[k]nowledge creation, sharing and use,’ refers to a process of creating and co-managing documents and products together with the network partners of the EEA (EEA 2018: 73; Interview 3; Interview 4). With this in mind, the latter part of the quantitative content analysis remains sensitive towards the fact that the EEA has three thematic areas of expertise and different types of output. Consequently, this part of the quantitative analysis focuses on identifying what type of communication dominates the relationship between the EEA and DGs. Also, and based on this information, this part of the analysis demonstrates as what kind of a knowledge producer the EEA is institutionalised as a part of the policymaking-complex of the Commission.

4.1. Key Partners

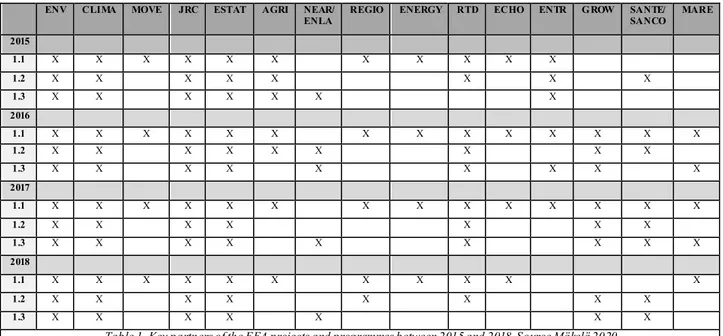

During the process of open coding, each of the DGs is treated as a category of their own. Also, each of the different types of activities presented in the sections 1.1-1.3 of the CAARs are treated as units of an analysis and assigned their own numerical value from 1 to 12 (for the coding table, see Appendix 1). As a result, the conducted quantitative content analysis suggests that during a time-period of four years the EEA have had 15 different DGs as its key partners. With this in mind, Table 1 provides an overview of the key partners of the EEA projects and programmes between 2015 and 2018. In order for a DG to be included into this table they have

been named as a key partner in at least one of the projects or programmes of the EEA during this time period.

ENV CLIMA MOVE JRC ESTAT AGRI NEAR/

ENLA REGIO ENERGY RTD ECHO ENTR GROW SANTE/ SANCO MARE 2015 1.1 X X X X X X X X X X X 1.2 X X X X X X X X 1.3 X X X X X X X 2016 1.1 X X X X X X X X X X X X X X 1.2 X X X X X X X X X 1.3 X X X X X X X X X 2017 1.1 X X X X X X X X X X X X X X 1.2 X X X X X X X 1.3 X X X X X X X X X 2018 1.1 X X X X X X X X X X X 1.2 X X X X X X X X 1.3 X X X X X X X Table 1. Key partners of the EEA projects and programmes between 2015 and 2018. Source Mäkelä 2020

The adopted theoretical framework steers the analytical focus of this research on sustained patterns of interaction and communication which are normatively speaking expected to increase the likelihood of socialisation (Schimmelfenning 2000; Saurugger 2013). Consequently, identifying which of the DGs are most likely to be engaged in the process of socialisation with the EEA can be determined based on the consistency and endurance of interaction. Based on this theoretical framework, the DGs presented in Table 1 can be divided into two collections: the DGs the EEA interacts regularly and irregularly with. With this in mind, the first collection consists the DGs with whom the EEA interacts irregularly with, and the DGs included into this group are DG for Enterprise (ENTR), DG for Internal Market, Industry Entrepreneurship (GROW), and DG for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (MARE). These three respective DGs are placed into this group because each of them lacks a clear and enduring pattern of interaction across the analysed interval. Consequently, this group of DGs is removed from the rest of the analysis as irregular interaction is expected to impact negatively the process of socialisation between the EEA and the respective DGs at this point in time (Schimmelfenning 2000; Saurugger 2013).

The second collection consists the DGs with whom the EEA may be seen interacting regularly with. However, as demonstrated in Table 1, the patterns of interaction and

DGs are discussed next in three groups. The first group consists the DGs which are named as key partners of the EEA in the recording units 1.1 throughout the analysed interval. The DGs included into this group are DG for Mobility and Transport (MOVE), DG for Agriculture and Rural Development (AGRI), DG for Regional and Urban Policy (REGIO), DG for Energy (ENERGY), and DG for Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection (ECHO). Second group consists DG for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations (NEAR) which can be observed to be consistently among the key partners in the recording units 1.3 throughout the analysed interval, and this logic applies also to DG for Health and Food Safety (SANTE) in the recording units 1.2. Furthermore, this group consists also DG for Research and Innovation (RTD) which is consistently among the key partners both in the recording units 1.1 and 1.2 throughout the analysed interval. The third and last group consists rest of the DGs with whom the EEA may be seen interacting regularly with in all three recording units and throughout the analysed interval. The DGs included into this group are DG for Environment (ENV), DG for Climate Action (CLIMA), DG for Joint Research Centre (JRC), and Eurostat (ESTAT). The data discussed in the section 4.2 of this thesis is made available in the Appendix, and the findings made during this discussion are visualised in Table 2 made available in the section 4.3 of this thesis.

4.2. Role

As mentioned in the methods section, during the analysed interval the EEA can be seen engaging in twelve different type of activities and, during the process of coding, each of these activities are assigned their own numerical value from 1 to 12. Hence, rather than focusing on only one type of pre-determined activity, open coding enables the author to remain sensitive towards any form of sustained communication and interaction between the EEA and the DGs which can be used to identify patterns of formal interaction. With this in mind, as the first part of the analysis has already been used to identify a population of interest which remains relevant for the purpose of this study, this part of the quantitative content analysis focuses on patterns of sustained communication and interaction. This is done in order to verify as what kind of a knowledge producer the EEA is institutionalised as a part of the policymaking-complex of the Commission.

First, the analysis focuses on the sections 1.1 of the CAARs, and it concentrates explicitly on the EEA activities in which the key partner has been either the DG MOVE, DG AGRI, DG REGIO, DG ENERGY or DG ECHO (for context, see Appendix 2). Based on the obtained

data, the DG MOVE is consistently among the key partners in activities 1 and 2, the DG AGRI in activity 2, the DG REGIO in activities 4 and 5, the DG ENERGY in activity 1, and the DG ECHO in activity 5. At the same time, the conducted analysis points out that the EEA has carried out a number of other activities during this time period. However, because these activities cannot be seen representing a consistent form of communication or interaction, they are being excluded from rest of the analysis as irregularity in interaction is expected to impact negatively the process of socialisation (Schimmelfenning 2000; Saurugger 2013).

Next the analysis focuses on all three sections of the CAARs and explicitly on the EEA activities in which the key partner has been either the DG RTD, DG SANTE, or DG NEAR (for context, see Appendix 3). Based on the obtained data, the DG RTD is consistently among the key partners of the EEA in activities 1-6 in the sections 1.1 and 1.2. On the other hand, and in the case of the DG SANTE, there exists a pattern of sustained interaction in relation to type 1 activities in the sections 1.2, whereas in the case of the DG NEAR this can be seen to be the case in relation to type 3 activities in the sections 1.3. Therefore, it seems evident that the EEA does not interact with all of the DGs in an identical manner across its three thematic areas of expertise (1.1.-1.3). It appears also evident that there exists variation in the trend of communication taking place within the thematic areas and depending which of the DGs the EEA may be seen engaging with.

Next the analysis focuses on the sections 1.1 of the CAARs and concentrates explicitly on the EEA activities in which the key partners have been the DG ENV, DG CLIMA, DG JRC and DG ESTAT (for context, see Appendix 4). Consequently, based on the obtained data the DG ENV is consistently among the key partners of the EEA activities in activities 1-6, the DG CLIMA in activities 1-6, the DG JRC in activities 1-6, and the DG ESTAT in activities 1-6. Hence, there is one clear pattern of interaction among all of the DGs across the analysed interval. On the other hand, activities represented by numbers from 7 to 12 do not form a clear and consistent pattern of interaction in the case of any of the DGs.

Next the analysis focuses on the sections 1.2 of the CAARs and concentrates explicitly on the EEA activities in which the key partners have been the DG ENV, DG CLIMA, DG JRC and DG ESTAT (for context, see Appendix 5). Based on the obtained data, the DG ENV can be seen consistently among the key partners of the EEA in activities 1, 3 and 4, the DG CLIMA in activities 1 and 3, the DG JRC in activities 1, 3, 4 and 5, and the DG ESTAT in activity 3.

Next the analysis focuses on the sections 1.3 of the CAARs and concentrates explicitly on the EEA activities in which the key partners have been the DG ENV, DG CLIMA, DG JRC and DG ESTAT (for context, see Appendix 6). In these sections, the DG ENV is consistently among the key partners of the EEA in activities 2-5, the DG CLIMA in activity 5, the DG JRC in activities 2, 4 and 5, and the DG ESTAT in activities 2 and 4. Even through there is some overlap between different patterns of interaction, there is no one clear pattern of interaction that would be common to all of the DGs alike.

4.3. Discussion of the Findings: Quantitative Content Analysis

The conducted quantitative content analysis serves a triple function. First, it is used to identify which of the DGs the EEA may be seen communicating regularly with. Secondly, in frame of the adopted theoretical framework the EEA may be seen practising its influence through sustained communication (Ahmed and Potter 2013; Saurugger 2013). Therefore, this part of the analysis provides an insight for understanding through what type of communication the EEA may be seen primarily practising its influence, and which of the DGs it is most likely to be engaged in socialisation with. Thirdly, the patterns of sustained communication are used to understand as what kind of a knowledge producer the EEA is institutionalised as a part of the policymaking complex of the Commission.

Section: Type: DG

MOVE AGRI DG REGIO DG ENERGY DG ECHO DG RTD DG SANTE DG NEAR DG ENV DG CLIMA DG JRC DG ESTAT DG

1.1 1 X X X X X X X 2 X X X X X X X 3 X X X X X 4 X X X X X 5 X X X X X X 6 X X X X X X X 1.2 1 X X 2 X X X X 3 X 4 X X X X X 5 X X X 6 X X 1.3 1 2 X X X 3 X X 4 X X X 5 X X X 6

Table 2. Summary of the frequently occurring communication from the EEA to the DGs between 2015 and 2018. Source: Mäkelä 2020

Based on the findings, it becomes evident that the output of the EEA is not channelled only to one of the DGs. Instead, based on the data obtained from the CAARs, the EEA can be seen

sustaining communication with 12 of the DGs. With this in mind, Table 2 provides a summary of the data discussed in the sections 4.1. and 4.2. of this thesis. This visualisation demonstrates that based on the frequency and quantity of formal and sustained communication, the EEA may be seen most embedded into the policymaking done by the DGs in the following order: the DG ENV/DG JRC, DG RTD, DG CLIMA/DG ESTAT, DG MOVE/DG REGIO, DG AGRI/DG ENERGY/DG ECHO/DG SANTE/DG NEAR.

Based on the conducted analysis, the EEA does not engage all of the DGs in an identical manner. The distribution of identified communication patterns summarised in Table 2 show that sustained communication takes however most frequently place in data and analysis related activities (section 1.1), followed by assessment related activities (section 1.2) and least activity can be recorded in relation to co-creating and co-managing information (section 1.3). Also, data related activities represent the only thematic area in which the EEA is in interaction with a clear majority of the DGs. It is worth highlighting that producing a more fine-grained discussion of the quality of influence these different types of activities can be seen having on the work done by the DGs fall outside the immediate focus of this thesis. However, based on the obtained evidence this thesis argues that the EEA practices its influence primarily through data and analysis related activities.

In summary, the conducted analysis demonstrates that the influence of the EEA is not tied to a single DG alone. In fact, and as a side note, based on the analysed sections of the CAARs it seems that the official output of the EEA is channelled as a rule to the DGs rather to the Commission as a one coherent entity. Therefore, in order to understand the role of the EEA in the policymaking-complex of the Commission it becomes necessary to focus on its relationship with the DGs in plural. The conducted analysis also provides an insight for understanding as what kind of a knowledge producer it is institutionalised as a part of the policymaking-complex of the Commission. Rather than drafting ‘sound and effective environmental policies,’ or assessments, as it was empowered to do by the European Council Regulation 933/1999, the primary role of the EEA seems to be complementary (Zito 2009: 1229-31, 1234-6). In other words, and just like the in case of influence, the primary role of the EEA may be seen to support Commission policy implementation through data and analysis related activities.

5. Semi-Structured Interviews

As discussed in the theoretical section of this thesis, the institutional closeness between the DG Environment and the EEA have invited some of the previous scholarship to draw attention to the monetary dependency between the two institutions (Zito 2009: Martens 2010). However, there seems to be no convincing evidence that this interdependence would compromise the ability of the EEA to formulate its own political agenda. Therefore, in order to better understand whether the EEA can be indeed treated as an independent, this part of the analysis begins by briefly focusing on the (in)formal institutional autonomy of the EEA and dependencies between the EEA and Commission (Ison, Collins and Wallis 2015; Prince 1994a).

The second part of the analysis focuses primarily on the role of the EEA in relation to the Commission and to the EU. This part of the analysis is used to generate additional and qualitative knowledge about the role of the EEA but also to cross references some of the findings made earlier in the quantitative content analysis of this thesis. Consequently, this part of the analysis invites the author to suggest that the role of the EEA is perhaps best understood as a part of a political triangle in which both information and legitimacy is being exchanged between member states of the EU, the EEA, and the Commission.

5.1. Autonomy

According to its current regulation, the EEA has two obligations: produce a ‘State of the Outlook’ report every five years, and to publish environmental data (European Parliament 2009; Interview 2). In this regard, the role of the EEA is well framed, yet as pointed out by one of the interviewees it leaves the EEA room to manoeuvre and to decide how it wishes to pursue these objectives in practice (Interview 3). At this point it is worth highlighting the nuanced distinction between the objectives of the EEA and its means to pursue them. In terms of the latter, as an autonomous agency the EEA is able to pursue its objectives according to its own strategic decisions. On the other hand, and in terms of the objectives, the work done by the EEA follows its multiannual and annual work programs, and all interviewees pointed commonly to a fact that the content and objectives of these programs is drafted by the Management Board of the EEA. This Board is a collection of representatives of the EEA’s cooperation partners, namely representatives from international organisations, the European Parliament, the Commission and DGs, around 30 member countries, Scientific Community of the EEA, just to name few (EEA 2019b; Interview 4). All of the interviewees consider the EEA to be formally and informally autonomous. When asked about the presence of the Commission

and DGs in the Management Board, interviewee 4 responded: ‘do they overrule us, or can they overrule us? The answer is no to both of those questions. We are independent.’ In summary, based on the conducted interviews the EEA is both able to autonomously steer its working processes, and its Management Board is not formally nor informally overruled by the Commission or DGs. Therefore, the EEA seems to be best understood as an autonomous political actor.

5.2. Dependencies

As discussed in the theoretical section of this thesis, Prince (1994a: 29, 33) theorises that when dependencies arise between an actor and international institutions the former too becomes an actor in IR, a theoretical standpoint adopted by this thesis. With this in mind, when asked how the interviewees considered that the role of the EEA has evolved over time, two of the respondents pointed to a legislative reform that they considered relevant for contextualising the relationship between the EEA and DGs. They commonly referred to an updated EEA regulation from 2009 which effectively makes it legally obligatory for both member states of the EU and the DGs alike to cooperate with the EEA (Interview 3; Interview 4; European Parliament 2009). This development is captured in the words of interviewee 3 who stated that: ‘early days they felt they had an option. Actually, if you read the regulation, they don’t have an option. They have to participate and collaborate.’ Interviewee 3 furthermore highlighted the fact that in 1998 Cardiff Summit effectively integrated environment as a subject into all socio-economic policymaking of the EU, providing an insight for understanding how come the EEA may be seen engaging with a number of different socio-economic DGs (European Council 1998). In summary, there seems to exist a formal dependency between the EEA and DGs.

When discussing the role of the EEA in relation to the DGs, and more explicitly the role of the EEA’s output, two of the interviewees highlighted spontaneously the importance of timing (Interview 2; Interview 3). As discussed above, as an autonomous agency the EEA holds the monopoly to choose how it pursues its annual objectives in practice, including the right to decide when it publishes its documents and reports. The two interviewees draw attention to the question of timing from opposite perspectives, and interviewee 3 highlights the fact that in order for the output of the EEA to have an impact on the work done by the Commission the multiannual and annual work programs of the two institutions need to be synchronised:

publish whenever we want,” exercising this independence, and it doesn't fit in. If it doesn't land, and so it doesn't support them, and our work really goes to waste.’

(Interview 3)

In other words, it seems that a as a coherent entity the EEA recognises that in order for it to be able to influence policymaking of the Commission it needs to take into consideration work programs of the Commission. On the other hand, interviewee 2 approached the question of timing from another perspective. In this case, it seems that the timing of the EEA reports has also a significance from the point of view of the Commission and DGs, meaning that there exists a mutual dependency between the two schools of institutions:

‘At times it has happened that I have experienced that a client or different parts of the Commission may ask that a particular report is published at a particular time, or maybe before an event or after an important event. So, the timing is quite important.’

(Interview 2)

In Summary, based on the information obtained through semi-structured interviews it seems that there exist formal dependencies between the EEA and Commission, but also between the EEA and EU member states who are obligated by legislation to cooperate with the EEA. There seems also to exist informal dependencies between the EEA and Commission as a whole: the EEA needs to practice its autonomy strategically in order to be able to influence policymaking of the Commission, whereas the DGs recognise that the output of the EEA is able to influence their working processes. Therefore, when combined with the notions made earlier in this part of the analysis, namely that the EEA seems to be best understood as an autonomous political actor, it seems evident that the EEA can be treated as an autonomous actor in IR.

5.3. Role of the EEA: Commission

As discussed on the theoretical section of this thesis, engaged scholarly literature provides little insight for understanding what the role of the EEA is in policymaking of the EU and Commission (Zito 2009; Martens 2010). With this in mind, when asked what is usually the role of the EEA in projects in which one of the key clients is a DG, interviewee 2 responded by emphasising that ‘in the EEA everything is international,’ but also that the EEA does not engage programs on a bilateral level but all of its programs are regional by scale. To put differently, even though the EEA interacts with individual states its programs are designed to