DOI: 10.1002/curj.84

‘Continuity and change’, large-scale

assessment and equity: a study of

gender-related differences regarding

conceptual knowledge

David Rosenlund*

Malmö University, SwedenThe study examines how students in Grade 9 handle conceptual knowledge through the concept of continuity and change in the context of large-scale assessment. The research questions address (a) what strategies the students use when they use the two parts of the concept concomitantly and (b) any gender-related differences regarding these strategies. A total of 100 student responses on a specific item in the national test in history are examined. The method of concept analysis is applied to identify the strategies of the students from the two groups. The analytical framework is based on previous research regarding the concept. The results show that just over half of the students use the concept as expected. Boys are overrepresented among the students that struggle with the concept. Any correlation between the identified strategies is discussed in addition to the implications the results may have on equity and education.

Keywords: large-scale assessment; conceptual knowledge; second-order concepts; history

education; historical thinking; gender

Introduction

It is well known that the content of formal school curricula has been shifting over time. In Sweden, from the first half of the twentieth-century onwards, the content of the history curricula has shifted from nationalist-oriented factual content, via a more objectively oriented factual content, to a curriculum content that aims to mirror the academic discipline of history (Rosenlund, 2016). This implies more than a simple change of what factual historical content (e.g. knowledge about historical agents and events) should be addressed in history education, as teachers are now expected to include other types of knowledge grounded in the academic discipline of history. This kind of knowledge from discipline has been included into primary and second-ary history curricula in a number of educational contexts (see e.g. Eliasson et al., 2015; Seixas, 2015b; Bertram, 2016) and is not unique to Sweden. One example of

*Faculty of Education and Society, Malmo University, 205 06 Malmö, Sweden. Email: david. rosenlund@mau.se

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

curriculum content that relates to the historical discipline, and thus, represents a dis-cipline-based type of knowledge is the concept of continuity and change. Introduced into the Swedish history curricula in 1994 (Skolverket, 2001, p. 67), this concept was given a more prominent place after the curriculum reform of 2011 (Skolverket, 2018, p. 213). The inclusion of discipline-based knowledge is not unique in history curricula and is regarded as more complex and abstract than more traditional factual content (Anderson, Krathwohl & Bloom, 2001; Young, 2014).

The inclusion of more complex types of knowledge into curricula has been prob-lematised on two interrelated grounds. First, research has shown that groups of al-ready disadvantaged students may have more difficulty acquiring a command over this knowledge than other groups (Teese & Polesel, 2003; Doherty, 2015; Rosenlund, 2019). Second, studies show that teaching this type of disciplinary knowledge in the classroom requires a high degree of teacher competence. This competence has to include both the complex knowledge itself and knowledge about how to teach it (Wilson & Wineburg, 2001; McCabe, 2017).

One central theme in the existing literature that addresses continuity and change in history education is that the two parts of the concept, continuity and change, are interrelated and should be addressed concomitantly. This is important because the interaction between continuity and change is a central part of understanding histor-ical processes (Blow, 2011) and serves to nuance the relationship between past and present (Seixas, 2015). What results from the interrelatedness when students use the concept is not addressed with any detail in the existing research. In this study, I examine the strategies that students use when they apply the two parts of continu-ity and change concomitantly. The identified strategies also relate to the discussion about the possible problems with equity that may be the result of introducing more complex knowledge into formal curricula (Beck, 2013, p. 187). The issue of equity is possible to address because the study is based on empirical material from a high-stakes assessment programme.

The overarching aim of the study is thus to further the knowledge about how stu-dents use conceptual knowledge. To achieve this aim, stustu-dents’ concomitant use of the continuity and change concept is used as a case study. Two research questions concretise the aim of the study: (1) What strategies do students use when they ad-dress continuity and change concomitantly? And (2) what differences, if any, can be observed between the strategies used by girls and those used by boys?

What kind of knowledge is ‘continuity and change’?

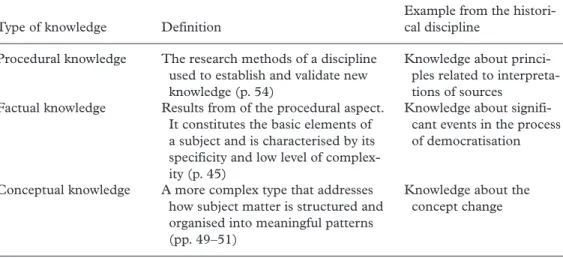

When discipline-based concept continuity and change was introduced into the Swedish history curriculum in 1994, the idea was that teachers include a concept with a rather high degree of complexity into their teaching. Anderson et al. (2001) offer one way to categorise this and other types of curricular knowledge with different degrees of complexity stemming from academic disciplines. They argue that it is use-ful, particularly for educational purposes, to make distinctions between three types of disciplinary knowledge: procedural, factual and conceptual (see Table 1).

As conceptual knowledge is the focus of this article, I discuss one aspect of concep-tual knowledge in the discipline of history and make an attempt to locate the concept continuity and change into this context. Thereafter, I present how the concept of continuity and change has been recontextualised into history education.

One feature of conceptual knowledge defined by Anderson et al. addresses how connections are made between factual statements of a discipline. How then have historians addressed this issue? Ricoeur argues that, in creating historical narratives, historians balance between an episodic dimension where events are chronological and a configurational dimension where the events are related to each other and pro-vided with meaning (Ricoeur, 1980, p. 178). The content of the episodic dimension can be seen as examples of factual claims in the history subject. The configurational dimension, I argue, contains aspects of conceptual knowledge, as it is in this dimen-sion that connections are made between the factual propositions. Moving closer to the procedural aspects of history and the practical use of sources, we turn to Lorenz, who also addresses how historians relate factual claims to each other. He argues that there is a narrative space open for the historian and that this space exists be-tween the sources that are available to the historian (Lorenz, 1994, p. 325). Similarly, Jordanova claims that political and ideological assumptions may influence historians’ interpretations of sources and the composition of these interpretations into historical accounts (Jordanova, 2006, pp. 103–104; see also McCullagh, 2004, p. 24). Despite approaching history from different philosophical perspectives, these historians view this part of their work as historians similarly. More specifically, they understand the need to relate the interpretations of historical sources to each other to construct his-tory. In the words of Anderson et al., the ability to relate factual propositions to each other is dependent on the historian’s conceptual knowledge.

In the field of history education research, conceptual and procedural aspects of the historical discipline have been popularised with the term ‘second-order con-cepts’, and some of these second-order concepts have also been introduced into

Table 1. Definitions of types of knowledge (from Anderson et al., 2001) Type of knowledge Definition

Example from the histori-cal discipline

Procedural knowledge The research methods of a discipline used to establish and validate new knowledge (p. 54)

Knowledge about princi-ples related to interpreta-tions of sources

Factual knowledge Results from of the procedural aspect. It constitutes the basic elements of a subject and is characterised by its specificity and low level of complex-ity (p. 45)

Knowledge about signifi-cant events in the process of democratisation Conceptual knowledge A more complex type that addresses

how subject matter is structured and organised into meaningful patterns (pp. 49–51)

Knowledge about the concept change

formal history curricula internationally (see e.g. Eliasson et al., 2015; Seixas, 2015b; Bertram, 2016). With this terminology, factual knowledge is labelled as first-order knowledge. Although a canon of agreed-upon second-order concepts does not exist, the following are frequently used as examples of second-order concepts: evidence, historical account, empathy, continuity and change, historical perspective and cause and consequence (Lee, 2004, p. 130; Seixas, 2015a, pp. 6–9). Some of these sec-ond-order concepts lean more towards procedural knowledge (i.e. the concept of ‘ev-idence’), while others have characteristics of conceptual knowledge (i.e. the concept of ‘continuity and change’).

History education researchers have identified continuity and change in the work of academic historians and confirm that the concept is used to make connections between historical phenomena that are chronologically separated (Foster, 2013, p. 9; Seixas, 2015a, p. 261). One identified strategy is that both parts of the continuity and change concept are used by historians and exist concomitantly in the study of a historical process (Foster, 2013). Regarding change, research shows that histori-ans evaluate historical processes of change and describe these changes in terms of progress or decline. In most studies addressing continuity and change in the context of history education, more attention is given change than continuity. Change is de-scribed as varying in speed and having different degrees of impact (Foster, 2013, p. 9; Seixas, 2015a, pp. 262–264). Blow (2011) has suggested a progression model where the two parts of the concept are addressed separately on the lower levels of the model and addressed concomitantly on the higher levels.

I argue that here it is evident that continuity and change is used by academic his-torians and in history education research as conceptual knowledge as it is defined by Anderson et al. The concept is used to make connections between factual claims that originate from the discipline. This study examines the extent to which students use this disciplinary tool to make sense of the past.

Gender differences and historical knowledge

In many educational contexts, it is possible to identify group-level differences regard-ing school results. Such differences between boys and girls have been observed in Sweden (Björnsson, 2005; Klapp, 2015) and elsewhere (Voyer & Voyer, 2014), where boys have received lower results. These studies indicate that these differences may be the result of a lower degree of motivation among boys resulting from a combination of society’s lower expectations of boys and a negative approach to education among boys. Boys’ lower results as a group calls for further research regarding how these dif-ferences can be understood at the level of a specific school subject.

Some studies address gender differences regarding second-order knowledge in his-tory education. Huijgen et al. (2017, p. 122) used multiple-choice questions to ex-amine students’ capacity for perspective taking and found no significant differences between boys and girls. Samuelsson and Wendell (2016, p. 497) examined responses on a constructed-response question to address students’ competency to interpret sources, and they also found no differences between boys and girls. Andersson-Hult (2016) examines upper-secondary students’ historical consciousness using

constructed-response items. Here, the results show only small differences in the com-plexity of how boys and girls make connections between the past, the present and the future (Andersson Hult, 2016, pp. 92–97).

Research on gender differences involving first-order historical knowledge is incon-clusive but points in three general directions. First is the research indicating that boys perform better than girls in history. In an examination from the NAEP in the United States, a test with predominantly multiple-choice questions, it was found that boys outperform girls (Heafner & Fitchett, 2015, p. 242). In a similar study addressing the End Of Course Assessments in Florida, Furgione found that boys also perform better than girls. Again, the test consisted of multiple-choice items (Furgione et al., 2018, p. 82). Similarly, de Groot-Reuvekamp et al.’s study using multiple-choice questions to examine students’ (aged 6–12 years) understanding of historical time found no significant gender differences regarding emergent understandings of historical time. However, regarding the more complex stages of initial and continued understanding, the study shows that boys perform slightly better than girls (2017, pp. 238–239). In an intervention study aimed at improving students’ understanding of historical time, de Groot-Reuvekamp et al. also looked for gender differences regarding the students’ (aged 7–8 and 10–11) understanding of historical time. In the study, which used multiple-choice questions, the authors found that boys in both age groups per-formed better than girls (de Groot-Reuvekamp et al., 2018, p. 53). Second, in a study of students aged 8–12, Hodkinson examined temporal cognition and retention of historical knowledge and found that girls and boys performed on the same level (Hodkinson, 2009, pp. 59–60). Third, research indicates that girls have a somewhat more sophisticated approach to history. In a study of the results of the AP exam in the United States, Venkateswaran’s findings go in all the three aforementioned direc-tions; more specifically, boys perform better on multiple-choice items, girls perform better on essay questions, and on document-based questions which follow a con-structed-response format, the identified differences between boys and girls are neg-ligible (Venkateswaran, 2004, p. 509). In a study addressing writing and history, De La Paz et al. found that girls performed better with historical writing (2017, p. 47). One interesting pattern in the research presented here is that the gender differences that come to light regarding first-order knowledge, where boys seem to outperform girls, is not as evident in the studies addressing second-order knowledge and those based on document-based questions, where girls more often have the upper hand. The study presented in this article can contribute to the knowledge about eventual gender-related differences regarding conceptual knowledge, as it addresses students’ command over the concept of continuity and change.

Method

In this study, I examine student responses on the Swedish national test in history to further the knowledge about how students from different groups use conceptual knowledge. Every year, each lower secondary school in Sweden is required to con-duct a national test for Grade 9 students in one of four subjects (geography, history, religious studies or civics) subsumed under the label ‘social science subjects’. This

means that approximately 25% of Swedish students take the test in history each year (2017: n = 26 606 students). This national test can be considered as a high-stakes test, as it has a significant impact on the students’ grade. The high-stake factor in-creases the possibility of higher motivation for the students to do their best on the test. It also underscores the significance of the national test regarding equity because a student’s performance on the test will affect their grade, and thus, their opportu-nities later in life. The sample of answers included in this study was collected from completed tests that teachers are obliged to submit to the academic institution that creates the test. As the teachers are obliged to submit completed tests from students born on a certain date, the submitted tests are seen as a representative sample of all the tests taken in 2017.

From the tests submitted in 2017 (n = 716), a random selection from 50 girls and 50 boys was made. In the test from 2017, as in all the tests between 2013 and 2019, a constructed-response item is used to assess students’ command over continuity and change, and the responses to this item were used as the empirical data of this study. Two students did not participate in the part of the test where the item addressed in this study was present. As a result, the total number of students in the study is 98. An additional 13 students did not provide a response on the item addressing conti-nuity and change. These 13 students answered other items in the test; therefore, the absence of responses on this particular item can be interpreted as involving the lack of relevant conceptual knowledge required to produce an answer.

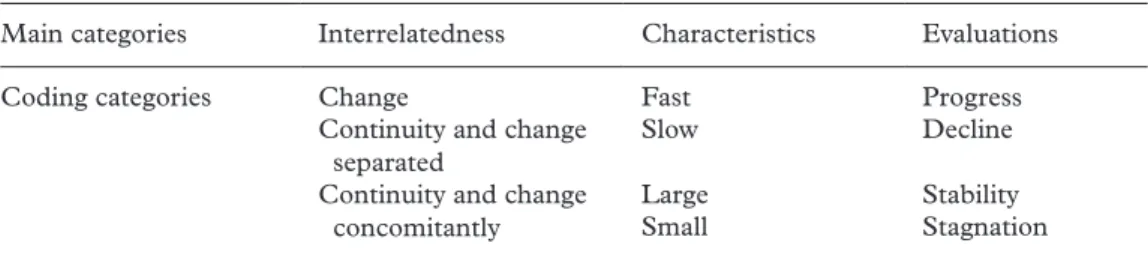

The method of concept analysis was chosen to examine the content in the student re-sponses. Concept analysis is a variant of content analysis where a deductive approach with predefined categories is applied to the empirical material (Schreier, 2012, pp. 84–86). As the aim is to further the understanding of what strategies enable students to work with continuity and change as two interrelated parts, an analytical framework was needed to make such an examination possible. First, based on existing literature on continuity and change, such an analytical framework was defined (see Table 2). It consisted of four main categories, each with more descriptive subcategories. This framework was used for an initial examination of 15 student responses. This initial analysis revealed that one of the main categories was not visible in the answers. The category that was removed addressed whether students applied the concept from the present perspective or from the perspective of the people living in the time periods addressed in the test item (Foster, 2013).

The first main category, which is the focus of this article, is based on the assump-tion that continuity and change should be addressed concomitantly, and this feature

Table 2. Coding categories

Main categories Interrelatedness Characteristics Evaluations

Coding categories Change Fast Progress

Continuity and change

separated Slow Decline

Continuity and change concomitantly

Large Stability

was visible in the initial examination. The more detailed coding categories of this main category are defined based on indications in the literature that some students address the two parts of the concept separately and some use them as interrelated parts (Blow, 2011; Foster, 2013). The second main category addresses how students characterise examples of change and examples of continuity, and here, the coding categories are adopted from Counsell’s (2011) discussion on this issue. The third main category relates to how students evaluate continuity and change and is based on discussions regarding how students approach change (Blow, 2011; Counsell, 2011). In order to include coding categories that could be used in relation to continuity, I referred to the empirical material. The initial reading of 15 student responses resulted in the addition of the categories stability and stagnation to the analytical framework. The 98 answers were coded in relation to the descriptive subcategories in the analyt-ical framework.

The first main category in the analytical framework is very similar to the aspects asked for in the test item that the students answer. In the item, it is clearly stated that the students should use both parts of the concept continuity and change in their answers (the item is presented in detail below). This feature of the concept is also reflected in the history curriculum (Skolverket, 2018, p. 213). The second and third main categories are not addressed in the item. However, they are included in the framework to determine to what extent these features are present in the answers and, if so, how they contribute with quality to the responses.

After the coding, the material was divided into two groups, girls and boys, and a comparative analysis was made between the two groups to determine if there were any differences regarding their command over the concepts of continuity and change. This comparative analysis has both qualitative and quantitative aspects. In order to examine the relationship between the aspects in the analytical framework, a Spearman correlation analysis was chosen because the variables are ordinal.

The responses to one item are examined, which means that the study is based on a limited part of the national test and, as it is a constructed-response item, means that students’ writing abilities may have an impact on the results. It is not possible to address the latter limitation by comparing the responses to this item with answers on multiple-choice question because no items on the national test address continuity and change. These limitations mean that the results presented in the article need to be interpreted with some caution and that further research is needed.

Ethical considerations

The submission of the aforementioned student answers is prescribed by the Swedish National Agency of Education with the purpose of research and test de-velopment (2020). The Agency of Education requires that the tests are anonymised by the teachers before being submitted, which negatively affects the possibility to acquire informed consent from the students. The collection and handling of the empirical material used in this study is nevertheless in accordance with the ethi-cal guidelines of the Swedish Research Council—the responses are produced as a result of regular school practice, they contain no personal or sensitive data, and

T

able 3.

Inter

rela

tedness of continuity and change

No expression of continuity or change

Only change

Continuity and change chronolog

ically separa

ted

Continuity and change used concomitantly

Bo ys 8 14 11 16 Girls 7 12 10 20 T otal 15 26 21 36

they are anonymised (Swedish Research Council, 2002, p. 9; Swedish Research Council, 2017, p. 28). These factors justify an exception from the principle of informed consent, as the students’ integrity is not infringed. To further ensure the students anonymity, information about the students’ school or county will not be included in this article.

Students’ competency to identify continuity and change in a national test The responses used in this study are from a constructed-response item that encour-ages students to use the concept of continuity and change in relation to a given historical process. The student responses were read in relation to an analytical frame-work that was constructed based on findings from previous research (see above). Each quotation is numbered and includes a letter indicating whether the answer is from a boy (B) or from a girl (G).

In this constructed-response item, students are presented with a timeline to which there are five time periods attached, spanning from the Middle Ages to the present. In these periods, seven historical examples are presented in writing, in which some are also accompanied with images. Each historical example lends itself to how a specific social phenomenon was perceived during that time period. The item is for-mulated with the following wording, ‘Using examples from the periods of history on the timeline, write about and discuss continuity and change in views of [the social phenomenon] in Sweden’.

The Agency of Education decided that the content of the test is to remain confi-dential until 2023. As a result, sections in the answers where the social phenomenon is mentioned have been removed. These sections are replaced with brackets, as in, [the social phenomenon]. Some quotations contain information that could reveal what social phenomenon is addressed in the item, and these have been replaced with [X]. These changes negatively affect the clarity of the quotations but are necessary due to the classified nature of the test. In the discussions regarding each of the quotations, I have attempted to clarify the quotations as they relate to the analytical framework.

Interrelatedness—the concomitant use of continuity and change

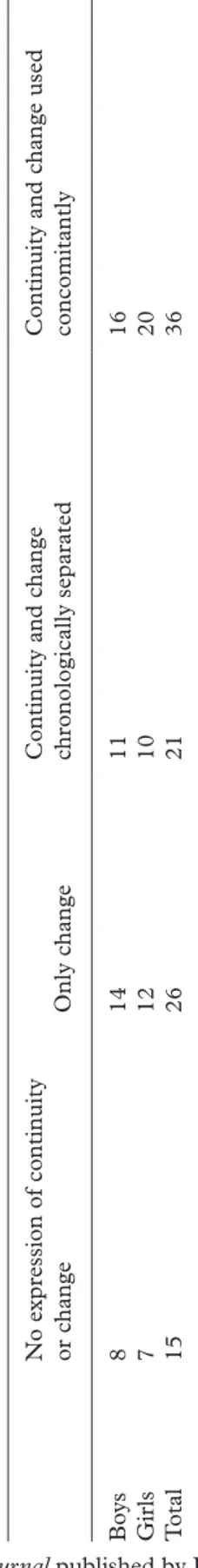

In this section, the first of the main categories in the analytical framework will be ad-dressed. The analysis shows that 15 students do not use any of the concepts of con-tinuity and change and do not show any sign of having command over the concepts asked for in the item (see Table 3).

A total of 26 students in the sample use the concept of change, but not continuity, to make connections between the historical examples that are placed along the time-line. In the analysis, no distinction is made between students who identify one dif-ference between two examples and students who identify several difdif-ferences between two or more of the historical examples. Differences in quality can be found in the 26 responses, but these differences will not be addressed here. In the following example, a student addresses change but does not show any sign of having command over the concept of continuity:

In the middle ages, [the societal institution] preached that [the social phenomenon] is a [X]. In

the 17th century, this changed, as they made laws that it was a [Y]. (594G)

Student (594) argues that there is a difference regarding the perception of the social phenomena between the examples from the Middle Ages and the seventeenth cen-tury, as it came to attract interest from an additional societal institution.

A total of 57 students used both continuity and change in their responses, and these can be divided into two separate groups based on how they used the concept. The first of these two ways is visible in the responses from 21 students; it is charac-terised by addressing continuity and change as chronologically separated. This means first addressing a period where there is change, after which there comes a period of continuity. An example of this is seen in the response from Student 267:

From the Middle Ages to the 19th century, the negative view of [the social phenomenon] was a continuity, but there was a change in the 19th century when people began to call it a [Y]. (267B) Student 267 identifies a continuity in the how people perceived the social phenom-enon between the Middle Ages and the nineteenth century. This is done without any explicit reference to the historical examples found on the timeline. There is no indication that the student identifies any change in this time period. The student then identifies a change in the nineteenth century. Therefore, in this response, change and continuity are separated from each other chronologically; first, there is a period of continuity, after which there is a period of change.

The quotation from Student 267 can be compared with the following quotation, which is categorised as the second way to address both continuity and change. The difference between the two quotations is that Student 371 identifies examples of continuity and change that exist concomitantly. This way to address the concept is found in 36 responses:

The view on [the social phenomenon] in Sweden has changed over the centuries; it has gone from having been a [X] within the church during the Middle Ages to the fact that [the social phenom-enon] was a [Z] during the 19th century, which is completely absurd. Although there has been a change, there is a continuous hatred of [the social phenomenon], even today, and the hatred of [the social phenomenon] has been going on since the Middle Ages. But it is positive that there have

been good changes since [judicial change in a certain year]. (371B)

In the quotation, Student 371 explicitly relates continuity and change to each other, which is why the answer is categorised as a concomitant use of the concepts. He begins by identifying a number of changes in the perception of the historical process. Thereafter, he claims that despite these changes, certain aspects exist continuously while these changes occur. These aspects of continuity are substantiated by referring to historical examples on the timeline. Forty-one responses do not contain both continuity and change. The responses in the second column in Table 3 refer solely to the concept of change. In the responses in the third and fourth column, it is possible to identify the use of both parts of the concept, as the responses here include examples of both continuity and change. These results lend support to the categories in the progression model presented by Blow, as the steps that she describes are also clearly visible in the material analysed in this study (Blow, 2011). In addition, it is worth noting that a larger share of girls address both con-cepts, which is an issue discussed in more detail in the following section.

Characteristics of continuity and change

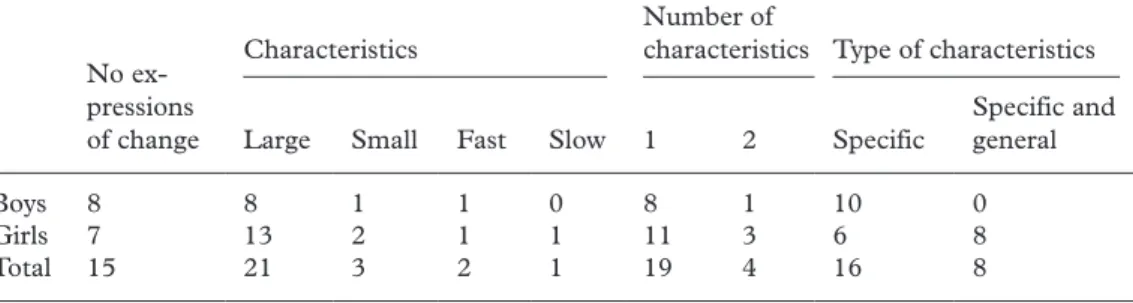

The second of the three categories in the analytical framework is about how students characterise the examples of continuity and change that they identify. In the literature on continuity and change, the speed and extent of change is frequently mentioned as aspects fruitful to address in relation to the concepts. In relation to the extent of a change, formulations about large or small changes, in addition to reflections about fast and slow changes, were coded to this category (see Table 4).

In the responses, some students address these characteristics of change, and it is possible to identify two different ways to frame the use of these characteristics. One is labelled specific and the other is labelled as general. The following quotation can be used to exemplify both these ways. In the second part of the quotation, the student directs our attention to the characteristics of a number of examples of change. This strategy is combined with a general, synthesising approach in the first two sentences of the quotation.

The view of [the social phenomenon] is something that has developed continuously but that has also changed. If you compare how people looked at [the social phenomenon] during the Middle Ages and how you look at it today, there is a huge difference. If you look at the Middle Ages, it was seen as a [X], but then the view of it changed and it was seen as a [Y], and this was in the 1600s. Then, in the 19th century, the view of [the social phenomenon] changes even more as it is seen as

a [Z], and we see once again a continuity from the Middle Ages to the 19th century. (448G)

In the second sentence, the student makes a general claim that there is a huge differ-ence in the view of the social phenomenon over time. Then, the student moves on to provide two specific examples of change relating to the examples found on the time-line in the test. In the second example on the timetime-line, the student claims that the view of the social phenomenon has changed ‘even more’, relating to the first example. The student also provides us with a characteristic of the specific example as being large. Here, we first see a more general claim about the extent of change over the whole time period covered in the test item, and then, a characterisation of a specific example of change.

How students in the sample characterise examples of change is presented in Table 4 above. A larger share of girls add characteristics to their descriptions, and most of the girls and boys characterise change as large, while other characteristics are used to a much lesser extent. Although there are few students using more than one character-istic, the middle section of the table shows that a larger share of girls do this. Finally,

Table 4. Characteristics of change

No ex-pressions of change

Characteristics

Number of

characteristics Type of characteristics

Large Small Fast Slow 1 2 Specific

Specific and general

Boys 8 8 1 1 0 8 1 10 0

Girls 7 13 2 1 1 11 3 6 8

in the two strategies presented in relation to the quotation from Student 448 above, the strategy of providing a characteristic of a specific example of change is seen in 16 responses. The second strategy—combining a specific characterisation of change with a general statement—is seen in eight responses. Here, a comparison between boys and girls shows that all the examples of general claims regarding the extent of change is made by girls.

In the next section, I present how students use evaluations of continuity and change.

Evaluations of continuity and change

In previous research, the terms ‘progress’ and ‘decline’ have been used to formulate how students evaluate aspects of change. To identify similar evaluations of aspects of continuity, the terms ‘stability’ and ‘stagnation’ are used in this study. Stability is used to describe instances where students regard continuity as positive, and stagnation is used when students view continuity in negative terms.

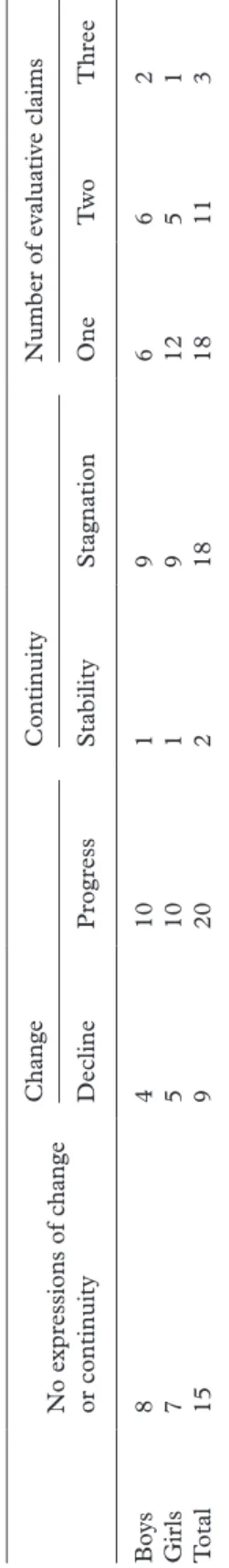

As seen in Table 5, examples of evaluative claims regarding both continuity and change can be found in the answers. A total of 32 students make evaluative claims in the responses, with some students making more than one such evaluative claim. The most frequent form of evaluative claim is that of progress, which is found in answers from 20 students. An example of this can be seen in the following quotation.

You can see on the timeline that there was continuity in that [the social phenomenon] was first [Y], and later also treated as a [Z] until the 20th century when there was a change. Then [the social phenomenon] was not seen as a [Y], and since the [a judicial change in a certain year], [the social phenomenon] is not seen as a [Z]. Then it just continued to get better and a big change in re-cent years is that you can be convicted of harassment against [the social phenomenon]. (675B) The student begins with presenting two examples from the timeline, and in the second sentence, the student argues that something has changed. This change is sub-stantiated by references to the timeline and is followed by an evaluative clam, as the student writes that things ‘continued to get better’. This is construed as the student arguing that changes in the twentieth century and the changes that followed in the twenty-first century have been positive, and thus, are examples of progress.

One aspect of continuity that is visible in the answers from 18 students is stagna-tion, a term used by students who argue that periods of continuity were negative. This way to evaluate continuity is seen in the following quotation.

During the 19th century, [the social phenomenon] began to be seen as a [Z]. This marks a major change from previous years. It gave a (albeit erroneous) reason why people became a part of [the social phenomenon], which led to that they were seen as [Z]. This excluded them even more out of society, since no one wanted to be associated with [Z] people. One continuity is that [the social phenomenon] was still seen as something bad, something [X]. This continues until the 20th

cen-tury. (75G)

In this answer, the student provides two examples from the timeline and argues that it is possible to identify continuity between the time periods based on these exam-ples. In the last sentence, the student makes the evaluative claim that this continuity should be regarded as negative. Therefore, this type of example is considered an ex-ample of stagnation.

T

able 5.

Ev

alua

tions of continuity and change

No expressions of change or continuity

Change Continuity Number of ev alua tiv e claims Decline Prog ress Stability Stagna tion One Tw o Three Bo ys 8 4 10 1 9 6 6 2 Girls 7 5 10 1 9 12 5 1 T otal 15 9 20 2 18 18 11 3

To make evaluative claims like those presented in the two quotations above, a student needs to address at least two historical examples and actively relate them to each other from an evaluative perspective. To make an evaluative claim, the student needs to relate the processes of change or continuity to some kind of standard. There were no such standards included in the item presented in this study, so the students making evaluative claims did this by relating to moral or ethical standards that they brought to the task themselves.

As mentioned, 32 students make evaluative claims in their responses, and more claims regarding change are made than those that address continuity. Progress is ad-dressed to a larger extent than decline, and stagnation is more common than stability. When the presence of evaluative claims is compared between boys and girls, one can see that there are only minor differences between the two groups, as there is one boy more who characterises change as progress and one girl more who characterises change as decline. In relation to continuity, no differences were found between boys and girls.

When boys and girls are compared, the last three columns in Table 5 show that more girls than boys make evaluative claims in their answers. This is most evident among students who make one claim. Of the students who make more than one claim, the numbers are more equally distributed among the sexes, with one boy more in each of the last two columns. These results complement the ideas brought forward by Counsell (2011) and Foster (2013), as they provide a detailed description of ways in which evaluations can be used to add quality to discussions on continuity and change.

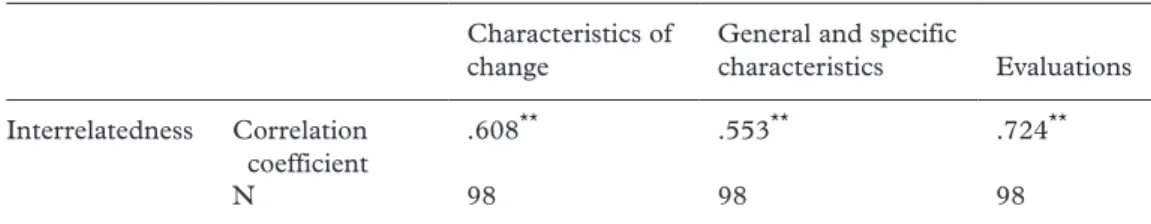

Correlations between strategies

In this section, I present how the use of characteristics and evaluations correlate with the use of both continuity and change in the answers. The correlation coefficients are presented in Table 6.

First, there is a positive Spearman correlation coefficient of .608 between re-sponses where examples of change are characterised in terms of extent and speed, and responses where both parts of the concept are addressed. This is interpreted as reflecting that the students who make more frequent use of characteristics are also more likely to address both continuity and change. In the same direction is the re-lation between the use of both specific and general characteristics, on the one hand, and the degree of interrelatedness, on the other hand. In this case, the positive cor-relation coefficient is .553, indicating that students that make both specific and more

Table 6. Correlations between strategies (All correlations are significant on the 0.01 level) Characteristics of

change General and specific characteristics Evaluations Interrelatedness Correlation

coefficient .608

** .553** .724**

general comments about change are more likely to use both parts of the concept. A positive correlation was also found between the increasing number of evaluations and responses where students use both concepts; in this case, the coefficient is .724. The following quotation is an example where the correlation between evaluations and concomitant use is visible.

In the Middle Ages until 1800, you can see a continuity. In both times, they think [the social phenomenon] is somehow wrong. In the Middle Ages, it was against an [X], and in the 1600s, it was still considered that [the social phenomenon] was wrong, and it now also a [Y]. In the 19th century, there was still a negative view on [the social phenomenon], but then they also choose to

see it as a [Z]. This is a constant negative view of [the social phenomenon]. (12B)

The pattern of continuity that the student constructs is about a continuous negative view of the social phenomenon, and thus, involves elements of evaluation. This type of response is coded to the category ‘stagnation’. The student evaluates the change when [Z] was included to explain the social phenomenon as negative. This type of response is thus categorised to the category ‘decline’. These examples of continuity and change are also interpreted as an example of the concomitant use of the concept. This is because the example of change is incorporated into a narrative of continuous aversion against the social phenomenon, and this type of response is coded to the concomitant category regarding interrelatedness.

Conclusions—how do students approach continuity and change?

Two research questions guided this study. The first of these involved the strategies that students used when they addressed the two parts of the concept continuity and change concomitantly, and the second involves the eventual differences at the group level between girls and boys. Regarding the first question, the results show strong correlations between answers where students characterised and evaluated examples of continuity and change and answers where the two parts of the concept were used concomitantly. Although the concomitant use of both parts of the concept were ex-plicitly asked for in the item, nearly half of the students did not do this. In the same manner, more than two-thirds of the students did not use the two strategies to char-acterise or evaluate the examples of continuity and change.

I argue that, when answering this item in the national test, the students were encouraged to work in Ricoeur’s configurational dimension. The quotation from Student 12 above exemplifies how connections between historical phenomena can be constructed. In this process, the concept of continuity and change is used as a tool that enables the student to organise the connections into meaningful patterns. In Lorentzian terms, this means the student uses the concept to fill the narrative space between the historical examples. The fact that the student makes evaluations indi-cates that he has brought his own values with him into the configurational dimension. This falls in line with Jordanova’s claim that we bring our own assumptions with us when we approach the past.

The second research question addresses eventual differences between boys and girls regarding what strategies they use when addressing continuity and change. The

girls in the sample used the three aforementioned strategies to a larger extent than the boys did, indicating that boys, on a group level, have more difficulty than girls in acquiring command over the concept continuity and change, and thus, lack an important part of what constitutes historical knowledge, the conceptual part. Adding to the impaired status of these students’ historical knowledge comes the fact that this has an effect on their grades. The results presented here nuance the picture of negligible differences between boys and girls given in previous research about gen-der differences regarding second-orgen-der knowledge. This indicates a need for further research regarding the relation between gender, item format and types of knowledge.

Discussion

To begin, I discuss the issue of differences among the students in the sample as a whole as well as group-level difference between girls and boys. Thereafter, I suggest how the re-sults of this study may be useful when addressing continuity and change in the classroom. Approximately 50% of the students in the sample did not use continuity and change in the expected manner, which is to use them in relation to each other. This indicates that many Swedish students do not have a command over the essential aspect of the concept—to address continuity and chance concomitantly—even though this should be addressed in history education. To further the understanding of this situation, we need to understand the conditions surrounding history education in Sweden.

For teachers to successfully implement the concept of continuity and change in history education, a number of factors must be in place. Adjusted for this specific context with concepts borrowed from Bernstein (2000), I base the following dis-cussion on four criteria for successful implementation (Century & Cassata, 2016, p. 186). These criteria are that teachers have (a) the necessary recognition rules in terms of knowledge about continuity and change, (b) the necessary realisation rules regarding how to mediate the knowledge to the students, (c) the willingness to ad-dress the concepts in their history classes and (d) sufficient support, in terms of time and educational material, to address the concepts in the classroom. Given that many of the students struggle with the concepts, I argue that this indicates a deficiency in one or more of these factors. The existing research regarding these factors is scarce in Sweden, but studies have found that some history teachers lack either (a) knowledge about conceptual aspects (Jarhall, 2012), (b) the competency to teach this type of knowledge (Samuelsson & Wendell, 2016; Stolare, 2017) or (c) an interest in ad-dressing conceptual knowledge in their teaching (Eliasson & Nordgren, 2016). Some studies put forward the argument that these factors are relevant in relation to concep-tual knowledge (Wilson & Wineburg, 2001, pp. 139–154; Monte-Sano, De La Paz & Felton, 2014, pp. 559–561). It is probable that (d) is also a relevant factor because time (Larsson, 2017) and textbook material that addresses conceptual knowledge is scarce (Reichenberg & Skjelbred, 2010, p. 208; Rosenlund, 2015, p. 52; Ammert & Sharp, 2016, pp. 70–71, 78–79). The context indicated by this research can help give an understanding of why so many of the students struggle with the concept of con-tinuity and change, with an overrepresentation of boys. On a group level, boys seem to struggle more than girls. This may be the result of lower motivation and negative

attitude towards education among boys and lower expectations on boys from teach-ers (Björnsson, 2005; Voyer & Voyer, 2014). However, it is likely that skilled and motivated teachers with relevant resources and sufficient time on their hands would have better opportunities to overcome the obstacles that hinder these students from acquiring command over more complex types of knowledge like conceptual knowl-edge. This conclusion may also be relevant for subjects other than history where conceptual knowledge is a part of the formal curriculum. To redress the inequity that appears to come with the inclusion of more complex knowledge in the curriculum, each of the four factors presented above needs to be carefully addressed to establish a thorough knowledge base, with possibilities for equal opportunities for all students.

The correlations between the three strategies can provide some directions for address-ing continuity and change in the classroom. As shown in Table 6, strong correlations exist between the use of characteristics and evaluations, on the one hand, and a concomitant use of continuity change, on the other hand. It is worth noting that the two former strat-egies were not asked for in the item, and thus, were what the students brought to the task as a result of what they had learned in their history classes or outside the history classroom. This indicates that if all students would be given access to these strategies, it might result in more students being able to address continuity and change in a more con-structive way. In relation to the characteristic strategy, this could be addressed by using terms suggested in previous research, like the extent and speed of change. In relation to the evaluation strategy, this could be carried out by having the students discuss conti-nuity and change from aspects used in previous research, progress and decline and, as previously discussed, applying the terms stability and stagnation in relation to continuity.

This means it could be worthwhile for teachers to address continuity and change by designing history lessons that encourage students to characterise and evaluate as-pects of both continuity and change. To facilitate this, teachers need to teach students constructive ways with which they can bring their own political and ideological as-sumptions to the task of identifying and creating meaningful patterns between factual historical claims. That would equip students with tools that are essential for working with Ricoeur’s configurational dimension. It would also result in a larger share of stu-dents with a command over the central part of conceptual knowledge in the history subject. Such planning and teaching is dependent on skilled and motivated teachers with adequate time in the classroom and high-quality resources.

Disclosure statement

No financial interest or benefit that has arisen from the direct applications of the research presented in this article.

References

Ammert, N. & Sharp, H. (2016) Working with the Cold War: Types of knowledge in Swedish and Australian history textbook activities, Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society, 8(2), 58–82.

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R. & Bloom, B. S. (2001) A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: a revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives (Complete edn) (New York, NY, Longman).

Andersson Hult, L. (2016) Historia i bagaget: En historiedidaktisk studie om varför historiemedvetande uttrycks i olika former [History as bagage—Various forms of historical consciousness]. (Umeå, Umeå Universitet).

Beck, J. (2013) Powerful knowledge, esoteric knowledge, curriculum knowledge, Cambridge Journal of Education, 43(2), 177–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057 64X.2013.767880

Bernstein, B. B. (2000) Pedagogy, symbolic control, and identity: Theory, research, critique. (Lanham, MD, Rowman & Littlefield).

Bertram, C. (2016) Recontextualising principles for the selection, sequencing and progression of history knowledge in four school curricula, Journal of Education, 64, 27–54.

Björnsson, M. (2005) Kön och skolframgång: tolkningar och perspektiv [Gender and school success: Interpretations and perspectives]. (Stockholm, Myndigheten för skolutveckling Stockholm). Blow, F. (2011) ‘Everything flows and nothing stays’: How students make sense of the historical

concepts of change, continuity and development, Teaching History, 145, 47–55.

Century, J. & Cassata, A. (2016) Implementation research: Finding common ground on what, how, why, where, and who, Review of Research in Education, 40(1), 169–215.

Counsell, C. (2011) What do we want students to do with historical change and continuity, in: I. Davies (Ed) Debates in history teaching (New York, NY, Routledge), 288.

de Groot-Reuvekamp, M., Ros, A. & van Boxtel, C. (2018) A successful professional development program in history: What matters?, Teaching and Teacher Education, 75, 290–301.

de Groot-Reuvekamp, M., Ros, A., van Boxtel, C. & Oort, F. (2017) Primary school pupils’ per-formances in understanding historical time, Education 3-13, 45(2), 227–242. https://doi. org/10.1080/03004 279.2015.1075053

De La Paz, S., Monte-Sano, C., Felton, M., Croninger, R., Jackson, C. & Piantedosi, K. W. (2017) A historical writing apprenticeship for adolescents: Integrating disciplinary learning with cog-nitive strategies, Reading Research Quarterly, 52(1), 31–52.

Doherty, C. (2015) The constraints of relevance on prevocational curriculum, Journal of Curriculum Studies, 47(5), 705–722.

Eliasson, P., Alvén, F., Yngvéus, C. A., Rosenlund, D., Ercikan, K. & Seixas, P. C. (2015) Historical consciousness and historical thinking reflected in large-scale assessment in Sweden, in: K. Ercikan & P. Seixas (Eds) New directions in assessing historical thinking (New York, NY, Routledge), 171.

Eliasson, P. & Nordgren, K. (2016) ‘Vilka är förutsättningarna i svensk grundskola för en inter-kulturell historieundervisning?’ [What are the conditions in Swedish compulsory school for an intercultural history education?], Nordidicatica-Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education, 2, 47–68.

Foster, R. (2013) The more things change, the more they stay the same: Developing students’ thinking about change and continuity, Teaching History, 151, 8.

Furgione, B., Evans, K., Jahani, S. & Russell, W. B. III (2018) Divided we test: Proficiency rate disparity based on the race, gender, and socioeconomic status of students on the Florida US History End-of-Course Assessment, Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 9(3), 62–96. Heafner, T. L. & Fitchett, P. G. (2015) An opportunity to learn US history: What NAEP data

sug-gest regarding the opportunity gap, The High School Journal, 98(3), 226–249.

Hodkinson, A. (2009) Are boys really better than girls at history? A critical examination of gen-der-related attainment differentials within the English Educational System, History Education Research Journal, 8(2), 51–62.

Huijgen, T., Van Boxtel, C., van de Grift, W. & Holthuis, P. (2017) Toward historical perspective taking: Students’ reasoning when contextualizing the actions of people in the past, Theory & Research in Social Education, 45(1), 110–144.

Jarhall, J. (2012) En komplex historia: lärares omformning, undervisningsmönster och strategier i histo-rieundervisning på högstadiet [A complex history: Teacher reform, teaching patterns and strate-gies in history teaching in high school] (vol. 17) (Karlstad, Karlstads Universitet).

Jordanova, L. J. (2006) History in practice (2nd edn) (London, Hodder Arnold).

Klapp, A. (2015) Does grading affect educational attainment? A longitudinal study, Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22(3), 302–323.

Larsson, H. A. (2017) Historieundervisningens framtid: En oviss historia [The future of history education: An uncertain story], in: R. Florin Sädbom, M. Gustafsson, & H. A. Larsson (Eds) Framåt uppåt!: Samhällsdidaktiska utmaningar. (Jönköping, Jönköping University).

Lee, P. (2004) Understanding history, in: P. Seixas (Ed) Theorizing historical consciousness (Toronto, University of Toronto Press).

Lorenz, C. (1994) Historical knowledge and historical reality: A plea for ‘internal realism’, History and Theory, 33(3), 297. https://doi.org/10.2307/2505476

McCabe, A. (2017) Knowledge and interaction in on-line discussions in Spanish by advanced lan-guage learners, Computer Assisted Lanlan-guage Learning, 30(3–4), 325–347.

McCullagh, C. B. (2004) What do historians argue about?, History and Theory, 43(1), 18–38. Monte-Sano, C., De La Paz, S. & Felton, M. (2014) Implementing a disciplinary-literacy

cur-riculum for US history: Learning from expert middle school teachers in diverse classrooms, Journal of Curriculum Studies, 46(4), 540–575.

Reichenberg, M. & Skjelbred, D. (2010) ‘Critical thinking’ and causality in history teaching ma-terial: An analysis of how the French revolution is presented in a Norwegian and a Swedish History Textbook for Junior High School, in P. Helgason, S. Lässig, & R. Henrӱ (Ed) Opening the mind or drawing boundaries? 185–218.

Ricoeur, P. (1980) Narrative time. Critical Inquiry, 7(1), 169–190.

Rosenlund, D. (2015) Source criticism in the classroom: An empiricist straitjacket on pupils’ his-torical thinking? Hishis-torical Encounters, 2(1), 47–57.

Rosenlund, D. (2016) History education as content, methods or orientation? A study of curriculum pre-scriptions, teacher-made tasks and student strategies (New York, NY: Peter Lang).

Rosenlund, D. (2019) Powerful knowledge and equity: How students from different backgrounds approach procedural aspects of history in large-scale testing, Nordidactica: Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education, 2019, 28–49.

Samuelsson, J. & Wendell, J. (2016) Historical thinking about sources in the context of a stan-dards-based curriculum: a Swedish case, Curriculum Journal, 27(4), 479–499. https://doi. org/10.1080/09585 176.2016.1195275

Schreier, M. (2012) Qualitative content analysis in practice (Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications). Seixas, P. (2015a) Looking for History, in: A. Chapman & A. Wilschut (Eds) Joined up history: New

directions in history education research (Charlotte, NC, Information Age Publishing).

Seixas, P. (2015b) A model of historical thinking, Educational Philosophy and Theory, 49, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131 857.2015.1101363

Skolverket [National Agency for Education]. (2001) Compulsory school: Syllabuses (Fritzes, Stockholm).

Skolverket [National Agency for Education]. (2018) Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and school-age educare: revised 2018 (Norstedts, Stockholm).

Stolare, M. (2017) Did the Vikings really have helmets with horns? Sources and narrative content in Swedish upper primary school history teaching, Education, 45(1), 36–50.

Swedish Research Council (2002) Forskningsetiska principer inom humanistisk-samhällsvetenskaplig forskning [Research Ethics in Social Science Research] (Stockholm, Swedish Research Council). Swedish Research Council (2017) Good research practice (Stockholm, Swedish Research Council). Teese, R. & Polesel, J. (2003) Undemocratic schooling: Equity and quality in mass secondary education

in Australia (Carlton, Melbourne University Publishing).

Venkateswaran, U. (2004) Race and gender issues on the AP United States history examination, The History Teacher, 37(4), 501–512.

Voyer, D. & Voyer, S. D. (2014) Gender differences in scholastic achievement: A meta-analysis, Psychological bulletin, 140(4), 1174–1204.

Wilson, S. & Wineburg, S. (2001) Peering at history through different lenses: The role of disci-plinary perspectives in teaching history, in: S. Wineburg (Ed) Historical thinking and other un-natural acts (Philadelphia, PA, Temple University Press), 139–154.

Young, M. (2014) Powerful knowledge as a curriculum principle, in: M. Young, D. Lambert, C. Roberts & M. Roberts (Eds) Knowledge and the future school: Curriculum and social justice (2nd edn) (London, Bloomsbury), 65–88.