‘Martyrs and Heroines’

vs.

‘Victims and Suicide Attackers’

A Critical Discourse Analysis of YPJ’s and the UK media

representations of the YPJ’s ideological agency

Amelie Malmgren and Michelle Fabiana Palharini

Malmö University, May 18, 2018Media and Communication Studies: Culture, Collaborative Media, and the Creative Industries

One-year Master Thesis (15 Credits) Spring, 2018

Supervisor: Ilkin Mehrabov Examiner: Michael Krona

2

Abstract

The present thesis compares media representations of Yekîneyên Parastina Jin (YPJ or the Women’s Protection Units), an all-female Kurdish military organisation, in British media versus the organisation’s own media outlets, with the aim to see how they differ, more specifically in terms of representations of their ideological agency. By utilizing critical discourse analysis (CDA) in combination with postcolonial theory, the media construction of four soldiers’ deaths have been scrutinized in 30 media texts in order to provide a deeper understanding of the hegemonic discourses and sociocultural practices which underpin these constructions. The result shows a discrepancy in terms of representations of YPJ’s ideological agency. On the one hand, YPJ adopts an explicit effort to assert their ideology through a propagandistic discourse that emphasises their values of resistance, freedom, egalitarianism, gender emancipation and democratic confederalism, portraying their fighters as fearless martyrs and heroines that are determined to die for their cause. On the other hand, the UK media represent YPJ’s ideology in generic ways in which hidden ideological ‘us vs. them’ representations are deeply rooted in a broader naturalised Western hegemonic discourse, with portrayals of YPJ’s fallen soldiers mostly characterised by sensationalism and victimisation. One part of such hidden ideological agenda is the way in which YPJ constantly gets included in, and excluded from, ‘us’ (the West), depending on who the enemy is, in addition to mainly receiving media coverage in direct relation to ISIS, a common Western enemy. The result is a representation that endorses YPJ’s fight within a hegemonic Western discourse, neglecting their ideological agency. This has sociocultural implications since such hegemonic discourse misrepresents YPJ’s struggle, constructing their fight mostly as part of a Western counterterrorist strategy, which further legitimises the Western power to construct history based on its own premises and claims of truth.

Key words: YPJ, UK media, media representations, Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), Postcolonial studies, hegemonic discourse, sensationalism, victimisation, Kurdish female fighters

3

List of Abbreviations

PKK - Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê (Kurdistan Worker’s Party) PYD - Partiya Yekîtiya Demokrat (Democratic Union Party)

YAJK - Yekitiya Azadiya Jinen Kurdistan (Union of Free Women of Kurdistan) YJA STAR - Yekîneyên Jinên Azad ên Star (Free Women's STAR Units) YPG - Yekîneyên Parastina Gel (People's Protection Units)

4 Table of Contents Abstract... 2 List of Abbreviations ... 3 Table of Contents ... 4 1. Introduction... 6

1.1 Aim and research questions ... 7

1.2 Relevance to Media and Communication studies ... 8

1.3 Delimitations ... 8

1.4 Thesis Outline ... 9

2. Literature review ... 10

2.1 Representation of female soldiers in Western media ... 10

2.2 YPJ in Western media ... 13

3. Contextualisation ... 16

3.1 The Kurds ... 16

3.2 The Kurds in Syria ... 16

3.3 The Syrian war: atrocities and opportunities ... 17

3.4 The Rojava revolution ... 18

3.5 Kurdish women’s movement ... 20

3.6 YPJ ... 24

4. Analytical Framework ... 26

4.1 Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) ... 27

4.2 Discourse / Semiosis ... 30

4.3 Power... 31

4.4 Ideology ... 33

4.5 van Dijk’s ideological square ... 35

4.6 Postcolonial theory ... 36

4.6.1 Otherness ... 37

5. Methodology ... 39

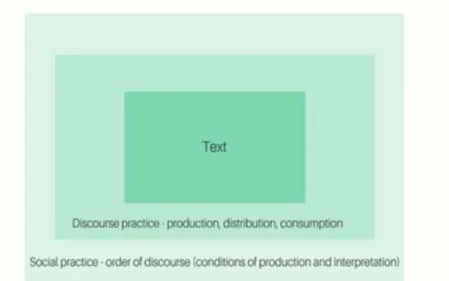

5.1 CDA and research strategy ... 40

5.2 Norman Fairclough: CDA as a method ... 41

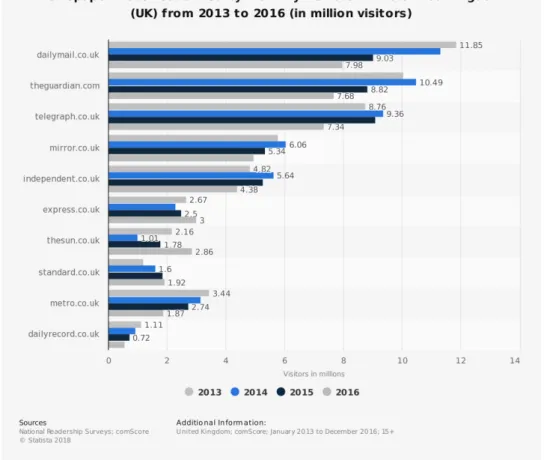

5.3 Data Collection ... 43

5.3.1 Limitations ... 43

5.3.2 Organisation and coding ... 45

5.4 Subjectivity, objectivity and reflectivity ... 46

6. Analysis ... 48

5

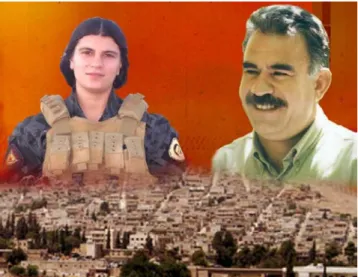

6.1.1 Arin Mirkan ... 48

6.1.2 Anna Campbell ... 48

6.1.3 Avesta Xabur ... 49

6.1.4 Barin Kobani ... 49

6.2 Case 1: Arin Mirkan ... 49

6.2.1 YPJ’s media... 49

6.2.2 British media ... 53

6.3 Case 2: Anna Campbell ... 59

6.3.1 YPJ’s media... 59

6.3.2 British media ... 63

6.4 Case 3: Avesta Xabur ... 67

6.4.1 YPJ’s media... 67

6.5 Case 4: Barin Kobani ... 70

6.5.1 British media ... 70

6.6 Analytical discussion... 74

6.6.1 Us vs. them (Otherness) ... 74

6.6.2 Representations of fallen YPJ soldiers: sensationalist and propagandistic discourses ... 76

7. Conclusion ... 79

7.1 Scope for further research ... 82

References ... 84

List of Figures ... 95

Appendix 1: Corpus ... 96

6

1. Introduction

“A country can’t be free unless the women are free”

(Öcalan, 2013, p. 7)

On March 15, 2018, Anna Campbell was killed by a Turkish air strike in the Kurdish enclave of Afrin in northern Syria and the news quickly spread around the world. Mostly because Campbell was the first British woman to die while volunteering in the war against ISIS (Dearden & Osbourne, 2018), but also because she was fighting alongside Yekîneyên Parastina Jin (YPJ or Women’s Protection Units in English), an all-female military organisation.

The Turkish onslaught on Afrin, known as Operation Olive Branch, constitutes one of the latest chapters in the Syrian crisis; a seven-year long conflict which involves various international political actors and thus has received the largest media war coverage in this millennium (Toivanen & Baser, 2016). However, even if the YPJ, with whom Anna Campbell fought side by side, have been engaged in armed battle since their establishment in March 2013 and the history of Kurdish female soldiers long proceeds the domino effect of the Arab Uprisings (Dirik, 2014), it was not until the ISIS’ siege of the autonomous Kurdish canton of Kobane in 2014 that they started to receive coverage in the Anglophone media (Szanto, 2016). A surge of attention swiftly spread among the Western media houses and on social media stories about YPJ soldiers like that of ‘The Angel of Kobane’1 went viral. Before the year was over, the organisation had been featured in an extensive photojournalistic piece in NBC News (Trieb, 2014), on CNN’s ‘Women of the year’ list alongside German politician Angela Merkel and British actress Emma Watson (CNN, 2014) as well as on BBC #trending (Devichand et al., 2014).

By now a plethora of news stories, comments and reports have been written about YPJ, often accompanied by visual illustrations and interviews (Toivanen & Baser, 2016). However, the majority of the attention the soldiers have received has been in direct

1 In 2014 a photograph of a YPJ soldier smiling into the camera while giving the victory sign was shared in the thousands on Facebook and Twitter where she was dubbed ‘The Angel of Kobane’. Accompanying texts claimed she had killed over a hundred ISIS fighters single-handedly, making her a symbol of resistance. Later the same image resurfaced in tweets claiming that she had been captivated and beheaded by ISIS. According to BBC News both stories were fabricated and ‘The Angel of Kobane’ never existed (Devichand et al., 2014).

7 relation to their assumed antithesis – ISIS. As a matter of fact, it is difficult to find news on the organisation where ISIS is not mentioned. This hyperbolic juxtaposition of ‘female’ fighting ‘male’ has also led to a media representation of YPJ as “modern-day heroine figures that are largely glorified” (p. 294). Another equally popular rendering in Western media, especially among tabloids, is an exaggerated focus on the soldiers’ physical appearance and headlines like ‘Battling beauty takes her own life to avoid Islamic State torture’ (Lawton, 2014), ‘Angelina Jolie of Kurdistan dies while battling ISIS’ (Robinson, 2016) and ‘Female Kurd soldiers fighting ISIS explain why they wear lipstick and make-up on battlefield’ (Webb, 2016) serve as good examples.

What we find troubling is that, regardless of whether YPJ soldiers have been represented as heroic superwomen fighting ISIS or as gun-toting beauties, portrayals in Western media have often neglected to mention that the organisation’s history is highly intertwined with that of the Kurdish freedom movement (Dirik, 2014). Nor do they tend to clarify that YPJ is part of the armed wing of Rojava, a de facto autonomous region in Northern Syria which practises democratic confederalism and is held by scholars as one of the most radical social experiments in today’s Middle East (Cemgil & Hoffmann, 2016; Hunt, 2017). Rather on the contrary, if the organisation’s ideological underpinnings do receive attention, it is mostly in simplistic and trivialised ways (Alonso Soriano, 2016). It might therefore not come as a surprise that the Western media representations of YPJ have already received criticism from scholars and activists alike (see Alonso Soriano, 2016; Dirik, 2014, 2015a; Szanto, 2016; Tank, 2017; Toivanen & Baser, 2016).

What is surprising, however, is that no one within Anglophone academia has yet focused on how YPJ represent themselves. Especially considering that they are active media makers and frequently update their web page, Facebook page and Twitter account.

1.1 Aim and research questions

The purpose of this study is to provide a deeper understanding of how YPJ portray themselves in the media by comparing their self-produced representations to those of Western media in order to see how they contrast. We believe that this serves as a good approach to critically reflect upon the monolithic and reductionist representations of YPJ’s ideological agency in the Western media. Thus, by examining four different case

8 studies with the help of Critical Discourse Analysis in combination with Postcolonial theory, we aim to problematize Western media discourses on the YPJ’s ideological agency while contrasting it with how YPJ choose to portray themselves. As such, we pose the following main research question:

How does YPJ's own media representation differ from the way the organisation is commonly portrayed in Western mainstream media?

We also pose the following operational sub questions in order to guide the research process:

How do YPJ portray themselves in terms of their ideology through their media channels?

How do Western media portray YPJ and their ideological agency? How do their portrayals differ from that of YPJ?

1.2 Relevance to Media and Communication studies

This thesis explores two opposing ways of presenting the same group of women, namely YPJ soldiers engaged in the Syrian war. The study of representations in media is important within the field of Media and Communication Studies and this thesis contributes with a stimulating discussion on the Western media discourses surrounding female soldiers, in addition to an analysis of YPJ’s own media representation - a research topic which to our knowledge has not been explored in English-speaking academia before. As a matter of fact, research on YPJ from a Media and Communication perspective remains scarce, thus, this study should be considered a humble addition to an area in dire need of further investigation.

1.3 Delimitations

In order to answer the abovementioned research questions we will focus on four different YPJ soldiers’ death and analyse how they have been portrayed in YPJ’s own media

9 channels and British media respectively2. Our emphasis is on larger hegemonic discourses and sociocultural practices in Western verses Kurdish society, thus, media outlets from each culture will be analysed together and we will not focus on institutional processes and differences within each media house. We will further limit our study to the analysis of these media representations and will not discuss how they have been received by audiences and the possible consequences they might have had. Neither do we aim to provide an exhaustive analysis of the media representations of the Syrian conflict as a whole, or give a full account of the political specifics that led up to each soldier’s death. Our interest lies solely in analysing how these four cases have been portrayed in a Western context versus YPJ’s own media outlets and problematize the hegemonic discourses within these representations.

1.4 Thesis Outline

Our study consists of 7 chapters. In this first introductory chapter we have outlined our area of interest in addition to presenting our research questions, choice of methodology and analytical framework. In addition, we have also situated the thesis within Media and Communication Studies. In chapter two, Literature review, we present relevant research on media representations of the female soldier with particular focus on previous research conducted on media portrayals of YPJ. In the following chapter, Contextualisation, we provide an extensive account of the Kurdish freedom movement, as well as YPJ’s background and ideology. In chapter four, Analytical Framework, the analytical structure that guides this study is explained and motivated. Chapter five, Methodology, focuses on our methodological considerations in addition to a discussion on our corpus, limitations and reflexivity in qualitative research. In chapter six, named Analysis, we present an analysis of our selected data by using our analytical framework in combination with abovementioned methodology. The final chapter, Conclusion, is where our findings are presented together with a concluding discussion before areas for further research are suggested.

10

2. Literature review

Even if YPJ’s own media representation has not (to our knowledge) been explored within English-speaking academia before, a fair amount of research has been conducted on Euro- American media representations on female soldiers in general. In this chapter we present previous research which is relevant to our thesis, with a special focus on the studies conducted on Western media portrayals of YPJ.

2.1 Representation of female soldiers in Western media

The presence of women in war is certainly not new and various scholars have already paid attention to the common perceptions and representations of female soldiers engaged in armed conflicts around the world. In 1982 Jean Bethke Elshtain wrote one of the foundational texts on war and gender where she problematizes the illusion of men as ‘Just Warriors’ and women as ‘Beautiful Souls’ and convincingly argues for a disenthrallment of the two tropes by illuminating to what extent they have come to define women as non-combatants and men as incorrigible beasts and warriors. Unfortunately, we argue, her reasoning is still as relevant today and can be seen echoed in various pieces of contemporary research on media representation of women engaged in armed conflict during the last decade. American scholar Brigitte L. Nacos’ study on female terrorists, for example, concludes that, even if there is no evidence that female terrorists are fundamentally different from their male counterparts in terms of motivation, ideological dedication and brutality, Western media’s treatment of them is still “consistent with the patterns of societal gender stereotypes” (2005, p. 436).

Nacos establishes six frames that are used in media in order to describe female terrorists and to validate and elucidate behaviour that is considered out-of-character for women, namely; (1) The Physical Appearance frame, (2) The Family Connection frame, (3) Terrorist for the Sake of Love frame, (4) The Women’s Lib/Equality frame, (5) The Tough-as-Males/Tougher-than-Men frame, and finally (6) The Bored, Naïve, Out-of-touch-with-reality frame (2005, pp. 438-445). Even if these categories are not mutually exclusive and often tend to overlap, none of them, as Pinar Tank points out, “adequately reflects women’s agency from a political or ideological vantage point” (Tank, 2017, p. 410). Rather on the contrary, by relying on frames like these, Western media undermines

11 female fighters’ political agenda by instead focusing on features which are easier to sell to their readers.

One such case is highlighted in Mats Utas’ (2005) research on female fighters in the Liberian civil war (1999-2003); that of a woman called Black Diamond. At the time she was Liberia’s highest-ranking female rebel, “a fearsome commander known for handcuffing wayward soldiers - male and female - to an air conditioning grate and beating them with a rubber hose” (Itano, 2003, para 6). According to Utas (2005), her brutality made her a counter-hegemonic actor to the dominant Western gender discourse and thus renowned in media for not behaving as an ordinary woman-at-war who bears the brunt of male violence (and consequently falling under Nacos’ (2005) The Tough-as-Males/Tougher-than-Men frame). Like Elshtain (1982), Utas too points out that the “binary opposition between peaceful women and violent men runs deep in Western emotio-histories” (2005, p. 405) and the appearance of Black Diamond and her fellow female soldiers therefore resulted in a state of confusion among journalists and an obsession with their feminine traits like hair-does, makeup and clothes; everything that stood in stark contrast to their roles as rebel combatants. To exemplify his reasoning Utas refers to the following excerpt from an article published in the Guardian, where Black Diamond is elaborately described by journalist Rory Caroll:

Her look is Black Panther-turned-movie star: mirror sunglasses, frizzy wig beneath the beret, silver earrings, red-painted nails. After clearing the port with just a handful of female fighters, she reloaded the Kalashnikov, adjusted the Colt .38 wedged in her hip and roared off in a silver Mitsubishi pick-up. (Carroll, 2003 cited in Utas, 2005, p. 404).

Chris Coulter, who researched interpretations on female fighters in the neighbouring country of Sierra Leone, complements Utas’ observation by stating that there is “decidedly a sexualized language in Western media descriptions of West African female fighters” (Coulter, 2008, p. 64). Coulter also agrees with Utas’ conclusion that, even if the portrayals of Black Diamond definitely did not deny her agency, they did ultimately reproduce and reinforce a broader dominant media frame that “has established Liberia as a case of difference—of the “African Other” to the rest of the world” (Utas, 2005, p. 404). In ‘normal’ African conflicts, like those in Uganda and Congo, women participated in rebel movements too but only by occupying supporting roles: “(t)hey cook, clean, and

12 often sleep with soldiers – not always by choice” (Itano, 2003, para 4). In other words, functions which did not challenge the conventional perception of what women in war do (and do not) and thus made them far less interesting to Western media outlets.

Another group of women engaged in conflict who has received considerable attention are the Palestinian female suicide bombers. Dorit Naaman (2007), who conducted research on their representation in Western (and Arabic) media found that, in contrast to the Black Diamond’s sensationalized hyper-agency, these women’s agency was completely removed. Naaman therefore concludes that “the most common way that Western media grapple with the deviation from traditional womanly roles is by adopting a thesis that female suicide bombers are victims of patriarchy” (2007, p. 943). She too exemplifies her argument with an article from the Guardian, where writer Giles Foden raises the question if men are in fact to blame for the women in terrorism and turns to Dr. Meir Litvak from Tel Aviv University for an answer:

Litvak certainly believes the role of women in Muslim suicide bombing is a function of patriarchal control: “Those who send these women do not really care for women’s rights,” he says. “They are exploiting the personal frustrations and grievances of these women for their own political goals, while they continue to limit the role of women in other aspects of life. (Foden, 2003 cited in Naaman, 2007, p. 943).

In combination with similar examples, Naaman convincingly argues that Western media’s treatment of Palestinian female suicide bombers relies on convenient gendered (and religious) stereotypes which do not consider the fact that women, like men, are fully capable of choosing to give up their life for a political cause. Rather on the contrary, by depicting them as “deviant from prescribed forms of femininity, forms that emphasize a woman’s delicacy and fragility but also her generosity, caring nature, motherliness, and sensitivity to others’ needs” (Naaman, 2007, p. 936) media places them in a Western hegemonic framework, which “enables readers and viewers to maintain both the comfortable gender status quo and their preconceived notions about the Palestinian-Israeli conflict” (Naaman, 2007, p. 952).

Sara Struckman (2010), yet another scholar who has focused on representations of female suicide bombers in Western media, reaches the same conclusion. She analysed how the

13 Black Widows – Chechen women who carried out suicide bombings to avenge lost husbands and sons during the country’s struggle for independence (and thus falling under Nacos’ (2005) Terrorist for the Sake of Love frame) – were portrayed in the New York Times. Struckman highlights that the term Black Widow was initially coined by Russian media outlets and later adopted by Western media; however, the New York Times did not fully buy the motivation given for the women’s violent actions. Consequently, the newspaper had to provide other culturally suitable reasons to account for their incentive and in doing so it “simultaneously broke away from and remained faithful to media’s role as a ‘circuit of culture’, skilfully disseminating acceptable feminine- especially acceptable Western feminine – gender roles” (Struckman, 2010, p. 92). The result of her research shows that most of the coverage suggests that “men are workers with political motivations and women are drawn into violence and terrorism only through their relationships with men” (Struckman, 2010, p.103); and, even if the Black Widow’s motivation for carrying out vengeance was questioned, the New York Times still relied heavily on gendered explanations which stripped the Black Widows of agency, “effectively robbing them of a desire on political grounds to fight for the Chechen cause” (Struckman, 2010, p. 103). A conclusion highly similar to that of Naaman’s (2007) research on the Palestinian female suicide bombers.

As above examples have shown, Western media representations of women engaged in armed conflict are more often than not perpetuating Elshtain’s (1982) binary opposition of ‘violent men as perpetrators’ and ‘women as victims’ (Koçer, 2016). Or, in cases like that of Black Diamond, whose brutality was hard to victimize, the female soldier is portrayed as something exceptional and deviant (Coulter, 2008, p 62), even if a growing body of research argues that women do join militant organisations for “their own purposes that they aim to fulfil within the ideology of militancy” (Olshanska, 2014, p. 9) and that women do commit violent actions, rationally or irrationally, just like men (see Alison, 2004; Cohen, 2013; Naaman, 2007; Sjoberg & Gentry, 2007).

2.2 YPJ in Western media

As mentioned in the introduction, YPJ have just recently started to receive attention by scholars and mainly within the fields of Peace and Conflict, Feminist, and Middle Eastern

14 Studies. There are, however, a few researchers who have analysed how the organisation and its soldiers have been represented in Western media. Mari Toivan and Bahar Baser, for example, compare how YPJ are portrayed in British and French media between 2014 and 2015 and distinguish four main frames used for depiction - 1) Struggle for equality/emancipation/liberation, 2) Personal/emotional motivations, 3) Physical appearance, and 4) Exceptionalism (Toivan et al., 2016, p. 301) - which are not too different from those of Nacos’ (2005) mentioned above. Toivan and Baser conclude that, even if some dissimilarities could be found between the countries (British media tended to emphasize the evolution from victimhood to female heroes fighting ISIS, whereas French media chose to present them as modern-day Joan of Arcs defending the Kurdish liberté, égalité, fraternité (2016, p. 310) – YPJ were mainly portrayed with gendered agency and, just like Black Diamond (Utas, 2005), sensationalized for doing a ‘men’s job’ (Toivan & Baser 2016, p. 310). Little attention was paid to YPJ’s political agenda and their relation to the Kurdish Workers’ Party, PKK (which is criminalized in both countries), thus Toivan and Baser argue that “the frames that the media used to narrate female Kurdish fighters made their stories palatable for French and British audiences by omitting certain aspects that might come across as controversial” (2016, p. 310). An observation that is echoed in Pinar Tank’s article, where she concludes that “(d)espite a rising interest in Kurdish female fighters, few reports in English-language mainstream media investigate these fighters’ political agenda” (2017, p. 406). And, like Toivan and Baser (2016), Tank too found that the narratives used by media when depicting YPJ “speak to preconceived notions of femininity, centred on frailty and victimhood” (Tank, 2017, p. 406).

Another scholar who has also analysed media representations of YPJ is Edith Szanto (2016), although in a slightly different way. Her research focuses on the most widely disseminated pictures and videos in Anglophone media of women involved in the Syrian uprising and, as far as YPJ, she raises a highly interesting question. Why have they received so much attention compared to other all-female military organisations, like Hara’ir Dayr Zawr (Free Women of Dayr Zawr), Banat Walid (Daughters of al-Walid) and Ummuna ‘A’ischa (Our Mother Aisha), who are also fighting in the Syrian war (2016, p. 310)? Szanto conjectures that these groups are too ‘Muslim’ for the Euro-American taste and, thus, harder to sell than YPJ, who are interestingly ‘oriental’ but not too much so (2016, p. 310).

15 Yet, the hardest critique of Western media representations of YPJ undoubtedly comes from Dilar Dirik (2014; 2015b), a scholar and Kurdish activist, who writes that:

Typical of western media's myopia, instead of considering the implications of women taking up arms in what is essentially a patriarchal society - especially against a group that rapes and sells women as sex-slaves - even fashion magazines appropriate the struggle of Kurdish women for their own sensationalist purposes (2014, para 4).

She also highlights that Western media “erroneously present Kurdish women fighters as a novel phenomenon” (Dirik, 2014, para 2), when the truth is that they have been fighting for decades, the only difference is that they did so “with very little media attention” (ibid. para 16).

16

3. Contextualisation

In this section, we seek to contextualize the background of YPJ and to offer a deeper understanding of the organisation from a social, historical and, most importantly, ideological perspective. In order to do so, however, we deem it necessary to begin with a brief historical background on the Kurds, the oppression they have been submitted to and how the Syrian Kurds were able to establish themselves politically and military in in the northern part of the country known as Rojava. We will then provide an explanation of their current politics and the Kurdish Women’s movement in order to understand how and why YPJ emerged.

3.1 The Kurds

The Kurds are an indigenous ethnic minority native to the Kurdistan region, or the “Land of the Kurds” (Gunter, 2014, p. 1), which is situated in the mountainous Middle Eastern borders at the convergence of Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria. Estimates on their population size vary greatly, with the most realistic approximations ranging from 35-40 million, of which around 19 million are found in Turkey, 10-18 million in Iran, 5.6 million in Iraq, 3 million in Syria, 0.5 million in the former Soviet Union and around 1 million in Europe (Knapp, 2016, p. 1). They compose the third biggest ethnic group in the Middle East (after Arabs and Turks) (ibid.) and the world’s biggest ethnic group that does not possess their own independent state (Gunter, 2014, p. 1). Throughout the 21st century they have been living under great injustice, suffering from several forms of oppression such as denial of territory and political voice, murder and persecution (Kurdistan National Congress, 2014, p. 4; Federici, 2015, p. 81).

3.2 The Kurds in Syria

In Syria, the Kurds compose the country’s second largest ethnicity and they have long been considered a threat to Syria’s Arab nationalistic identity. In the 1960s and 1970s, various efforts were carried out to ‘arabise’ the Kurdish regions in the North; for example the sudden government population census in 1962 when the Syrian Kurdish population was requested to prove that they had been residing there since (at least) 1945. All Syrian

17 Kurds who could not prove it lost their citizenship, resulting in around 120,000 Kurds becoming “ajanib” (foreigner in Arabic) overnight (Human Rights Watch, 1996). As such they were not entitled to passports and could not exercise “the internationally legal right to freedom of movement and to legally leave and return their own country (Syria)” (ibid. p. 3). Unregistered Kurds also lost civil rights like voting, participating in politics, legally marry and owning property (Tank, 2017, p. 412). Further efforts to arabise the Syrian Kurds led to Kurdish towns receiving Arabic names, Arabs receiving Kurdish land, the prohibition of officially using the Kurdish language and celebrating Kurdish folklore and festivities. (Human Rights Watch, 2009; Kurdistan National Congress, 2014).

The Syrian government’s harsh treatment also made it difficult for Kurds to mobilise and find political outlets, despite a popular desire to improve their standings (Federici, 2015, p. 82). There have been efforts though, like the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Syria founded in 1957, but most of the early political aspirations were weak and fragmented, owing in part to the constant suppression from the Syrian government. Under the Hafez al-Assad regime Kurdish political parties and organisations were outright banned and classified as illegal (Federici, 2015, p. 82). Thus, when Kurdish protesters demonstrated openly en masse for the first time in Qamishli in 2004, the government responded with swift violence resulting in mass arrests and more than 30 people being killed (Amnesty International, 2004).

3.3 The Syrian war: atrocities and opportunities

The onset of the war in Syria, sparked by the Arabic Uprising in 2011, confronted the Assad regime with the prospect of several enemy fronts and in 2012 the government was forced to withdraw its security forces from the country’s Kurdish-populated areas in the North. The assumption was that the Kurds would not be able to challenge the government anyway and that local armed militias, especially ISIS, would keep them under control (Tank, 2017). This sudden power vacuum, however, presented the local Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) with the opportunity to raise to power, and by late 2013 three Kurdish cantons (Afrin, Cizîrê and Kobani) in the region of Rojava had been declared autonomous (Toivanen & Baser, 2016; Federici, 2015). This would have been inconceivable, as noted by Federici (2015), before the outbreak of the Syrian war.

18 Figure 1 - Map of Rojava as of February 2014 (wikipedia.com, n.d.) (CC0 1.0) PYD was initially established in 2003 by former members of Turkish PKK (the Kurdish Workers’ Party), to whom Syria gave temporary sanctuary during the 1990s since they were able to use the party as a “bargain chip against the Turkish state’s control of the water flowing from the Euphrates River into Syria” (Tank, 2017, pp. 413-414). During this period many Syrian Kurds joined the PKK and when the party was ousted from the country in 1998 as a result of war threats from Turkey, PYD emerged as an offshoot to the original (Gunes & Lowe, 2015). This connection is often denied due to PKK being listed as a terrorist organisation by the European Union and the United States (Toivar & Baser, 2016). However, as Gunes and Lowe point out, it was this affiliation that gave PYD “greater discipline, organization and strategic planning in comparison with the older, fissiparous Kurdish parties” (2015, p. 4) and thus the ability to establish themselves as the main Kurdish party in northern Syria. Another new dynamic brought on by the Syrian war was the militarisation of the Syrian Kurdish struggle which became necessary, especially with the rise of ISIS (ibid.). As such, PYD’s armed wings YPG (People’s Protection Unit) and their female equivalent YPJ came to play key roles in the establishment of Rojava as an autonomous region (Federici, 2015).

3.4 The Rojava revolution

PYD’s Rojava project is remarkable in many ways but what makes it exceptional (Cemgil & Hoffmann, 2016; Gunes & Lowe, 2015; Hunt, 2017) is that it marks the first attempt to govern according to democratic confederalism, a political model developed by PKK’s

19 former leader, Abdullah Öcalan, who continues to lead the Kurdish freedom movement (Gunes & Lowe, 2015, p. 5). When Öcalan established PKK in 1978, it was a Marxist-Leninist movement aimed at achieving Kurdish independence through waging an insurgency against the Turkish government (Moreland, 2017). However, over the years Öcalan developed his ideology, especially after Syria’s aforementioned ousting of PKK in 1998 and his subsequent arrest and imprisonment by the Turkish state. While in solitary confinement, Öcalan came in contact with the writings of American eco-anarchist Murray Bookchin, whose thoughts on social transformation eventually led Öcalan to a radical paradigm shift: the Kurdish movement should renounce from their initial goal to establish a socialistic state of their own and instead aim for a pluralistic society where multi-lingual, multinational and multi-religious citizens would co-exist peacefully under a self-managing institutional structure (TATORT, 2013, p. 20). This political metamorphosis was the result of a critical reflection upon the capitalist society, which Öcalan deems a failure, and his conviction that it is inseparable from the nation-state model.

It is often said that the nation-state is concerned with the fate of the common people. This is not true. Rather, it is the national governor of the worldwide capitalist system, a vassal of the capitalist modernity which is more deeply entangled in the dominant structures of the capital than we usually tend to assume: It is a colony of the capital (Öcalan, 2011, p. 13).

Öcalan further argues that the capitalist system (and as a result the nation-state too) leads to unbalanced power distribution, exploitation and cultural assimilation (2011, pp. 11-12). Thus, “a separate Kurdish nation-state does not make sense for the Kurds” since it would only perpetuate their subjugation and “replace the old chains by new ones or even enhance the repression” (p. 19). Instead he proposes democratic confederalism, a system of “political self-administration, in which all groups of the society and all cultural identities express themselves in local meetings, general conventions, and councils” (p. 26), an administration which is “flexible, multi-cultural, anti-monopolistic, and consensus-oriented” and where “ecology and feminism are central pillars” (p. 21). Öcalan’s ideas are currently being implemented in Rojava and, as such, each of the region’s three cantons, Afrin, Cizîrê and Kobani, has its own government, constitution and parliament in addition to its own laws, courts and police forces. There are quotas in

20 place to ensure that all ethnicities3 are represented and that at least 40 per cent of all institutions, administrations and bodies are comprised by one of the sexes. In addition, male/female co-presidency is applied in order to ensure gender equality (Kurdistan National Congress, 2014). Each canton decide over their own social systems and education and in the Charter of Democratic Autonomy, the issue of natural resources, economy and property is highlighted as follow:

“The economic system in the areas of self-administration [Democratic Autonomy] work in an equitable and sustainable global development based manner, based on the development of science and technology, which aim at ensuring humanitarian needs and a decent standard of living for all citizens, through the increase of production and efficiency, and by ensuring a participatory economy whilst promoting competition in accordance with the principle of Democratic Autonomy ("Each according to his/her work"), and preventing monopoly and applying social justice” (2014, pp. 12-13).

Each canton also has its own set of YPG and YPJ armies, which together defend Rojava.

3.5 Kurdish women’s movement

Even if it were the female combatants of YPJ who stole the headlines in 2014 when they defeated ISIS in Kobani, it is important to point out that female soldiers are not new in the Kurdish struggle. Rather on the contrary, Kurdish women have been actively engaged in battle since the establishment of PKK in 1978 (Tank, 2017, p. 416) and, during the party’s insurgence against the Turkish state, many of the infamous suicide bombings were carried out by female soldiers (Gunes, 2013).

According to Çağlayan, Öcalan recognized early on that PKK would need the support and active participation of women, if the “People’s war” he had initiated against Turkey was to be successful (2012, p. 9). The party therefore commenced an intense female mobilisation, especially in the rural areas of the country. In doing so, they also challenged

3 In Rojava Kurds, Arabs, Assyrians (Assyrian Chaldeans and Arameans), Turkmen, Armenians, and Chechens, who religiously follow Islam, Christianity and Yazidism live together (Kurdistan National Congress, 2014, p. 12).

21 traditional Kurdish family structures which strictly controlled women under patriarchal rule at the time (Çağlayan, 2012, p. 9). As pointed out by Tezcür, “many women (…) associated joining the insurgency with the opportunity to leave oppressive conditions” (2014, p. 258) and the number of female soldiers steadily increased. PKK provided an opportunity to fight against Turkey but also against the gendered hierarchies within their own society in which “(l)ack of education, economic dependency, lack of freedom, honor killings and similar modes of women’s subjugation ran rampant” (Pavičić-Ivelja, 2017, p. 138).

In the 1990s when the conflict between PKK and Turkey escalated, female soldiers made crucial contributions on the battlefield and women like Berı̂tan, who killed herself instead of surrendering to the enemy in 1992, became role models for male and female soldiers alike, as well as important symbols for the Kurdish Women’s movement (Melis, 2016, para 4). Female PKK soldiers also begun to organise autonomously within the organisation and form their own military structures. In 1993 YAJK - Yekitiya Azadiya Jinen Kurdistan (Union of Free Women of Kurdistan)4 was established; a women’s-only guerrilla army complete with its own headquarters, commanders and training academies in the mountains of Kurdistan (Çiçek, 2015, para 12). This was actively encouraged by Öcalan (ibid.), whose initial criticism of patriarchy had deepened; by now he was convinced that only a bottom-up-approach which simultaneously addressed gender biases would bring freedom and equality to the Kurds. His theory was based on the conclusion that, if women constituted the most oppressed subgroup within a larger disempowered class (which they clearly did) the aspiration towards empowerment “must start from none other than women themselves since the liberation of the most oppressed subgroup consequently represents the liberation of groups and subgroups on all levels above it” (Pavičić-Ivelja, 2017, p. 137); much like the pyramid of capitalism in Marxist theory where the working class at the bottom supports all other classes but also have the power to topple the existing social order by revolting. In Öcalan’s own words:

The extent to which society can be thoroughly transformed is determined by the extent of the transformation attained by women. Similarly, the level of woman’s

4 YAJK still exists today but under the name YJA STAR - Yekîneyên Jinên Azad ên Star (Free Women's STAR Units) (Çiçek, 2015, para 12)

22 freedom and equality determines the freedom and equality of all sections of society. (2013, p. 57).

This theory eventually matured into a social science that Öcalan named Jineology, which literally translates into ‘the science of women’ (‘jin’ is the Kurdish word for woman) (Neven & Schäfers, 2017). The main aim behind Jineology is to bridge the gap that contemporary social sciences cannot fill since they are deemed too fragmented and divided (Nurhak, 2014). As a social science Jineology stems from Öcalan’s criticism of the development of existing scientific disciplines “within the framework of capitalist modernity” and following these tenets, it envisages a holistic slant on humankind, society and the universe; a “new epistemological approach fuelled by a conscience of freedom” (Valiente, 2015, para 19), which puts women at its core and holds their liberation as the solution. A central tenet in Jineology is the ‘principle of resistance’, which states that:

Women must see life as a domain for resistance. This is because without resistance women are being kept captive between four walls. Women are being loitered with simple tasks; therefore, to counter this, women must empower themselves by resisting in every possible way. (Öcalan, 2013 cited in Valiente, 2015, para 14). A principle that not only gives women the right to resist, but also to defend themselves. Öcalan explains this with his ‘rose theory’ which draws on universal principles of nature where every organism defends itself in order to survive. Hence, “living organisms such as roses with thorns develop their systems of self-defense not to attack, but to protect life” (Dirik, 2015b, para 4) and, acccording to Öcalan, so should women.

As pointed out by Pavičić-Ivelja (2017), the principles proposed by Jineology were not only applied within PKK, but women in general were encouraged to tackle and take on traditional male roles in their daily lives, thus “Jineology soon became one of the central tenets of the Kurdish struggle, permeating all aspects of life, from the battlefield, economy and politics to everyday activities” (p. 138).

Currently in Rojava, the women have continued this tradition and merged it with democratic confederalism. In 2005 Yekîtiya Star (Star Union of Women) was inaugurated, an umbrella organisation which fosters and supports smaller communes of local women who in turn focus on education, economy and self-defence (Jinha.com, 2015, para 4). Everything is done by women for women without the interference of men

23 (ibid.). Among the first laws to be passed in Rojava were those that protect women and children.

“Women have the right to exercise themselves in political, social, economic, cultural spheres and in all areas of life. Women have the right to organise themselves, and eliminate all forms of discrimination on grounds of gender. Furthermore, the rights of children are protected, particularly preventing child labour that exploits them psychologically and physically, and prohibiting marriage at a young age are the red lines of the understanding of democratic autonomy. The proportion of the representation of both genders in all institutions, administrations and bodies is of at least 40%” (Kurdistan National Congress, 2014, p. 12).

However, as pointed out by Dilar Dirik (2014), “it would be a stretch to call Kurdish society gender-equal, considering the prevalence of male-dominated rule and violence” and women in traditional families are still facing serious challenges despite years of struggling against chauvinism5. Thus, other initiatives besides Yekîtiya Star are: KCAVW – the Kurdish Committee Against Violence on Women - which organises seminars in an attempt to spread awareness on female-directed violence and encourages members of society to protect abused women” (Sheikho, 2017, para 3) and the SARA Organisation which advocates for women’s right in addition to collecting data and statistics on violations of these rights in Rojava (ibid.). In 2012 Yekîtiya Star also set up a women’s academy (where both sexes are welcome) and subjects like sociology, history and economy are taught through the lens of Jineology and democratic confederalism (Biehl, 2015). The following extract from Janet Biehl’s interview with Dorşîn, one of the teachers, serves as a good example:

“Our dream,” she said, “is that women’s participating and building society will change men, a new kind of masculinity will emerge. Concepts of men and women aren’t biologistic—we’re against that. We define gender as masculine and

5According to KCAVM’s annual report published on January 18, 2017, 799 women were victims of domestic violence in Rojava that year. The SARA Organisation’s report from 2016 affirms that “29 women received death threats, 3149 pressed charges for domestic violence, 38 were sexually harassed, 53 were minors forced into marriage, 13 were raped, and 27 tried to commit suicide as a result of familial and societal pressures” (Sheikho, 2017, para 20).

24 masculinity in connection with power and hegemony. Of course we believe that gender is socially constructed.” (Biehl, 2015, para. 28).

The academy also specialises in educating female revolutionary cadres thus, “(e)very program culminates in a final session called the platform. Here each student stands and says how she will participate in Rojava’s democracy. Will she join an organization, or the YPJ, or participate in a women’s council? What kind of responsibility she will take?” (Biehl, 2015, para. 28).

3.6 YPJ

YPJ was established in 2013 as an autonomous female counterpart to YPG (The People’s Protection Units) which is the armed wing of PYD. By now the YPJ makes up an estimated 35 percent of Rojava’s armed protection (Bengio, 2016, p. 39) and the organisation’s quick growth must be understood in the light of the context outlined above. The subjugation Kurdish women have endured (and are enduring) under traditional patriarchal rule, Öcalan’s encouragement of women reclaiming their right to organise and self-defend, in addition to the emergence of Jineology and democratic confederalism have all played important roles. Another imperative factor, however, was the rise of ISIS (Bateson, 2015). Harking back to the early 2000s, with their roots in al Qaeda, ISIS became one of the key players in the Syrian war and, over the course of 2013 and 2014, made large territorial gains in the country (Stanford University, 2017, para 1). With it came strict rule under religious Sharia Law and devastating violence, in particular a ‘hyper-masculine’ form of sexual violence against women, who were systematically raped, forced into marriages and/or sold as sex slaves (Ahram, 2015). Thus, as highlighted by Knapp, precisely because Rojava strives to be a radical democracy where women oppose to patriarchal claims of rule, the region came under attack by ISIS and its allies (2016, p. 133). This consequently led to more women joining YPJ since the organisation provided an opportunity to fight back (Bengio, 2016, p. 39). More experienced PKK female soldiers also began to arrive in Rojava and started training young people on how to handle weapons (Knapp, 2016, p. 136). These PKK soldiers also taught them theories on defence and self-protection, inspiring trust in families and encouraging more women to join the trainings (ibid.).

25 By now there are YPJ academies in each canton in Rojava and the soldiers are active on all defence and social fronts (Bateson, 2015). When volunteers join YPJ they are enrolled in military training in addition to compulsory education in Jineology, the right to self-defend and democratic autonomy (ibid.). As stated on YPJ Press’ page:

“Women’s protection units YPJ have two main pillars as follow:

First: intellectual training within the framework of ideological, political, cultural and social to acquire standards and a model of free life, sexual and national awareness, and to adopt an ecologically democratic mindset.

Second: Military training, where they are trained in the use of weapons, as well as martial arts on the fronts and the development of war tactics and technical skills, in order to achieve combat skill based on legitimate defense approach, and attention to physical fitness” (ypj.press, n.d.).

As for the internal structures of YPJ and YPG, although both organisations are very similar, for YPJ more importance is placed on their social role and the specific patriarchal challenges women face (Bateson, 2015). YPJ soldiers are thus “designated the role of protecting women’s values and defending gender freedom; the focus is not just on their military capabilities” (p. 35), even if they are just as valued as soldiers as their male counterpart YPG. As noted by Tank: “(t)heir agency is best expressed in the words of Sozda, a YPJ commander in Amûde: ‘We don’t want the world to know us because of our guns, but because of our ideas. We are not just women fighting ISIS. We struggle to change the society’s mentality and show the world what women are capable of’” (2017, p. 427).

26

4. Analytical Framework

In this chapter, we present the analytical framework that composes the backbone of the present thesis. Firstly, it is important to consider that the use of discourse analysis as a method requires the researcher to choose a theoretical framework within this field. As Martin Barker affirms, although scholars in this field do not always agree on any pivotal definitions of discourse analysis, the questions they are drawn to converge at a common intersection, that is, the “nature and role of language and other meaning-systems in the operation of social relations” (2008, p. 152). Most notably, scholars are concerned with the ‘power’ that these systems exert in the shaping of “identities, social practices, relations between individuals, communities, and all kinds of authority” (Baker, 2008, p. 152). Amongst many different tendencies in the work of discourse analysis that treat power as the key element in discourse, Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) has emerged as one of the most widely used frameworks in the past few decades. CDA not only offers a comprehensive theoretical framework but also an overarching method for carrying out the discourse analysis, which is concerned with how social and political inequalities are manifested in discourse (see chapter 5 for a detailed explanation of CDA methodology). As Michael Meyer states:

In general CDA asks different research questions. CDA scholars play an advocatory role for groups who suffer from social discrimination. (…) [I]n respect of the object of investigation, it is a fact that CDA follows a different and a critical approach to problems, since it endeavours to make explicit power relationships which are frequently hidden, and thereby to derive results which are of practical relevance. (Meyer, 2001, p. 15).

In the case of our research topic and questions, the analysis of power relationships and the interconnectedness between language and culture present in discourse play an important role. Here it is crucial to consider that the present work deals with two different streams of discourse, namely that of the UK media about YPJ, and that of YPJ about themselves. As shown in the contextualisation above, social and political inequalities are important elements in the understanding of YPJ; a military organisation with a strong ideological foundation which represents a watershed in terms of how they acknowledge the role of women. As such, we regard CDA as the appropriate framework to analyse how

27 relationships of power manifest in discourse (from both sides) and how they either challenge or generate social and political inequalities.

Although CDA composes the backbone of the present discourse analysis, we also use Postcolonial theory in order to support the understanding of power relationships and their connection with the historicity of discursive events and the broader context in which the present research topic unfolds. This should also aid in the comprehension of discursive events’ “involvement in making history (their remaking of orders of discourse)”, as proposed in CDA by Norman Fairclough (1995, p. 11). An outline of these theories will be provided in the following sections. Further related concepts are also defined in the subsections where they are pertinent.

4.1 Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA)

The origins of CDA is recognised as dating back to the 1970s with the works of Roger Fowler, Robert Hodge and Gunther Kress at the University of East Anglia (see Fairclough, 1992, p. 25; Thornborrow, 2002, p. 24; Trčková, 2014, p. 14). CDA is part of the hermeneutic tradition, which holds meaning to be ‘an ontological condition of social life’ that precedes the individual and determines the way an individual perceives the self and others. As Lilie Chouliaraki shows, in terms of linguistics, hermeneutics maintains that the ‘social’ can only exist as a result of our capacity to transform it into language (2008, p. 678). That is, “It is the historical nature of language or, more accurately, the horizon of interpretation that linguistic communication has historically constructed, that provides the conditions for understanding our world” (ibid.).

Within the backdrop of hermeneutics, as argued by Hans-Georg Gadamer, the social, political and economic scopes are components of our experiences that are moderated through language (1976, p. 31). Accordingly, it is possible to affirm that, as a research approach, CDA must be recognised in terms of specific contexts and historical elements, or as Michael Meyer puts it, CDA draws on the assumption that “all discourses are historical and can therefore only be understood with reference to their context” (2001, p. 15).

28 CDA can also be considered as a broader label for a “special approach to the study of text and talk” which has emerged from several disciplines, and which is characterised as an overtly critical “approach, position or stance of studying text and talk” (van Dijk, 1995a, p. 17) rather than epitomising a school of thought. An important aspect of CDA is its problem-/issue-oriented nature. Fairclough states that CDA is a type of critical social science that is conceived in order to shed light onto the problems “which people are confronted with by particular forms of social life” (2001, p. 125). In this sense, CDA envisages to supply the means that can be used by people in addressing and successfully dealing with these problems.

The object of analysis of CDA are dialectical relationships connecting semiosis and elements of social practice, in which semiosis encompasses “all forms of meaning making – visual images, body language, as well as language” (Fairclough, 2001, p. 122). More specifically, CDA is concerned with the drastic changes that have been emerging in contemporary social life, with the role played by semiosis amongst processes of change, and with “shifts in the relationship between semiosis and other social elements” (Fairclough, 2001, p. 123). As Fairclough argues, the part played by semiosis in social practices cannot be taken for granted. Instead, this role has to be established through analysis, which highlights the importance of CDA as a scientific tool in the understanding of semiosis in the context of social practices (2001, p. 123). Also Gillian Rose, a scholar who has been focusing particularly on the visual component of semiosis, points to the danger of taking its meaning-making role for granted and argues for a critical evaluation of the impact images have on our understanding of the world (2007, p. 12). Here it is important to note that Rose distinguishes between vision and visuality. Vision simply refers to the physical ability to see, but visuality describes the ways in which our vision is constructed: “how we see, how we are able, allowed, or made to see, and how we see this seeing and the unseeing therein” (Foster, 1988, p. ix cited in Rose, 2007, p. 2). Visual imagery, thus, photographs included, are never innocent but they construe the world and present it in particular ways and should therefore be considered a cultural practice which “both depend on and produce social inclusions and exclusions” (Rose, 2007, p. 12). A critical approach towards visual semiosis is therefore paramount in order to analyse how this is accomplished and how the problems arising from it should be understood.

29 Another scholar who draws attention to CDA’s ‘problem- /issue- oriented’ nature is van Dijk who argues that this aspect allows for any theories or methods to be utilised on the basis that these fruitfully enquire into social problems that are relevant, for example forms of social inequality. This also highlights the multidisciplinary nature of CDA, or as van Dijk puts is, “empirically adequate critical analysis of social problems is usually multidisciplinary” (1985, p. 353). Fairclough too states that CDA as theory (or method) is in a “dialogical relationship with other social theories and methods, which should engage with them in a ‘transdisciplinary' rather than just an interdisciplinary way (…)” (2001, pp. 121-122).

In epistemological terms, CDA is rooted in “a combination of critical-dialectical and phenomenologic-hermeneutic approaches” (Wodak & Weiss, 2005, p. 123). However, as argued by Ruth Wodak and Gilbert Weiss, in terms of theory, “(t)here is no such thing as a uniform, common theory formation determining CDA” (2005, p. 123) but rather numerous approaches. Other scholars also share the same conclusion, such as Meyer when he states that “(t)here is no guiding theoretical viewpoint that is used consistently within CDA, nor do the CDA protagonists proceed consistently from the area of theory to the field of discourse and then back to theory” (2001, p. 18). As such, the task of mapping the theoretical framework is not only highly dependent on the research question at hand but also on the ability of the researcher to craft the analysis of data collected along with theories that can explain the researched phenomena. This, in turn, is a task that may happen simultaneously since the analysis of the collected data sets the discursive patterns and categories, which then require theoretical explanation (see further detailed explanation in section 5.3).

Fairclough suggests that, when utilising transdisciplinary categories, CDA analysts often take an unduly simplistic slant to the use of concepts such as power and ideology (2008, p. 817). Besides, some critiques of CDA often refer to the vagueness with which CDA uses the term ‘discourse’ (see Widdowson, 1995, p. 158). As such, we proceed by providing an elaboration on some important terms as to build solid foundations for the analysis.

30

4.2 Discourse / Semiosis

Fairclough argues that the word ‘discourse’ itself can be used in various senses, as follows:

(a) meaning-making as an element of the social process, (b) the language associated with a particular social field or practice (e.g. ‘political discourse’), (c) a way of construing aspects of the world associated with a particular social perspective (e.g. a ‘neo-liberal discourse of globalization’) (2009, p. 1).

Because it is common to find confusion amongst these different ways of using the word discourse, Fairclough suggests using the term ‘semiosis’ for the first (a), which is the “most abstract and general sense” (2009, p. 1). Furthermore, using the word ‘semiosis’ for the first gives discourse analysis an edge, suggesting that it involves a variety of ‘semiotic modalities’ other than just language (such as visual images and body language) (2009, p. 1-2).

The notion of ‘discourse’ used in CDA is rooted in Michel Foucault’s ideas on discourse and power (Fairclough, 1995; Jäger, 2001) – in fact, discourse constitutes a key element in Foucault’s theoretical line of reasoning (Rose, 2001, p. 136). As pointed out by Hesmondhalgh, critical discourse analysis uses aspects of linguistics and Foucault’s idea that the experienced reality is constructed by discourses that are interwoven with relations of power (as cited in Hodkinson, 2010, p. 67). Concerned with the production of knowledge (as opposed to only meaning) and arguing that knowledge is constituted and socially constructed under circumstances of power, Foucault’s ideas compose a major variant of the social constructionist approach (Hall, 1997, p. 15) and he has consequently made enormous contributions to the fields of cultural and representation studies with his ‘discursive’ approach (Hall, 1997, p. 42). As Siegfried Jäger explains, knowledge here concerns multifarious kinds of content that compose a consciousness as well as numerous types of meanings that people use to construe and shape reality in their respective historical contexts (Jäger, 2001, p. 33). Such knowledge arises in discursive contexts in which people are inserted during their existence, and it is precisely this knowledge that discourse analysis aims to identify.

31 Another important approach to the notion of discourse is that of Jürgen Link who offers a resourceful cultural science approach following Foucault. According to Link, discourse analysis should focus on:

current discourses and the effects of their power, the illumination of the (language-based and iconographic) means by which they work - in particular by collective symbolism which contributes to the linking-up of the various discourse strands (as cited in Jäger, 2001, p. 33).

This analytical basis presents an interesting perspective in terms of discourses found in our capitalist postmodern society as a means to make the capitalist ideology legitimate and ensure its prevalence (Jäger, 2001, p. 33), a view that relates to Fairclough’s third sense of discourse (c). This is a key understanding for the present work, since it aids in explaining ideological contextual patterns from the UK media as inserted in a neo-liberal discourse frame. This can be inferred from Link’s view of discourse as being an institutionally consolidated speech that determines action and as such exercises power (as cited in Jäger, 2001, p. 34).

The view of discourse as a means of interpreting elements of the world that are associated with a certain social perspective (Fairclough’s third sense of the world discourse) is used in the present analysis at the level of social practices as proposed by Fairclough’s CDA methodology (see further detailed explanation in section 5.2). In this sense, the concepts of power and ideology becomes pivotal in the discourses found in the data analysis, and also directly related to cultural values. As such, in the following section we elaborate on these two concepts as to offer a clear definition of what is meant by power and ideology in the present work.

4.3 Power

Various definitions of power can be found within different academic fields, making it a highly debated concept. Within this variety of definitions, CDA scholars have also provided their own elaborations on the concept, for example Wodak who states that “power is about relations of difference, and particularly about the effects of differences in social structures” (2001, p. 11). Language, in turn, plays an important role in relation

32 to power since it “indexes power, expresses power, is involved where there is contention over and a challenge to power” (Wodak, 2001, p. 11). In this sense, language can be used to establish power, challenge power and alter distributions of power.

An important aspect of power and language is the power/discourse relationship. Here, two aspects must be highlighted, namely ‘power in discourse’, and ‘power behind discourse’ (Fairclough, 1989, p. 43). Power in discourse holds discourse as the means through which relations of power are employed and put into practice, such as the power in “cross-cultural discourse where participants belong to different ethnic groupings, and the 'hidden power' of the discourse of the mass media” (Fairclough, 1989, p. 43). In contrast, power behind discourse concerns effects of power in relation to orders of discourse and how they are shaped and constituted by relations of power (ibid.).

Mass media, such as news media outlets, present some interesting elements in terms of power in their discourse. One of them is “one-sidedness” or, as Fairclough argues, in media discourse there is a clear split between producers and interpreters (or producers and consumers, if the media product is considered a commodity) (1989, p. 49). In addition, because media discourse is conceived for the mass audiences, producers build their discourses to an ‘ideal subject’, and actual interpreters (audiences) have to work out how they relate to the ideal subject (1989, p. 49). Thus, according to Fairclough, producers possess exclusive rights over the production and, as such, can decide on what to include or exclude, as well as how to portray events (1989, p. 50).

In addition, there is an unequal influence of social groupings that is also determinant of whose perspective is adopted in media coverage (Fairclough, 1989, p. 51). For example, in their investigation of structuring and selecting news, Johan Galtung and Mari Ruge argue that the probability of an event to become news is higher the more the event concerns elite nations, elite people, personal terms, and negative consequences (1974, p. 66). As a consequence, people and organisations used as sources in news reporting are not representative of all social groupings in the population (Fairclough, 1989, p. 50). Such asymmetric influence of social groupings takes place in the overall balance of sources, perspectives and ideologies, which to a large degree favour existing power-holders. As Fairclough argues:

33 the media operate as a means for the expression and reproduction of the power of the dominant class and bloc. And the mediated power of existing power-holders is also a hidden power, because it is implicit in the practices of the media rather than being explicit (1989, p. 51).

Against this backdrop, ideologies emerge as closely related to power since power relations determine the nature of ideological assumptions and because, as Fairclough posits, ideologies compose the means of power legitimisation of existing social relations and differences of power (1989, p. 2). Such legitimisation is possible through the establishment of recurring norms that take these relations and differences of power for granted, which then become a commonsensical way of behaving (Fairclough, 1989, p. 2). Since the use of language is the “commonest form of social behaviour” (ibid.), language occupies a central place in ideologies. In the following section we present the understanding of the concept of ideology that is adopted in the present work.

4.4 Ideology

“One of the aims of CDA is to `demystify' discourses by deciphering ideologies.”

(Wodak, 2001, p. 10)

The understanding of the concept of ideology plays an important role in the present work, for two main reasons. Firstly, because as demonstrated in the contextualisation section, ideology is an active element in the understanding of YPJ. Secondly, because the investigation of how YPJ’s ideological agency is portrayed by the UK media and by YPJ themselves is central in our research. In this sense, the understanding of how ideological stances manifest in the UK media’s discourse around YPJ is paramount in the analysis, an assumption based on Fairclough’s argument that language is a material form of ideology (Fairclough, 1995, p. 43). Following this premise, it is key for CDA analysts to understand how social issues are mediated within the backdrop of ideologies. In the case of the UK, the latent ideology is capitalism in the form of neo-liberalism.

During the past two centuries, many philosophical and sociological schools of thought have proposed several definitions for the term ideology (van Dijk, 1995b, p. 244), making it a problematic concept due to the amount of conflicting definitions that exist (Trčková,

34 2014, p. 18). CDA scholars have also elaborated on the term, mostly taking a critical-theoretical stance. Ruth Wodak, for instance, argues that critical theory offers an important perspective for the understanding of CDA and notions of ideology (2001, p. 10). An example of this is the relationship between the concepts of ideology and culture, and mass communication as discussed by Thompson. For him, ideology encompasses ‘social forms and processes’ through which ‘symbolic forms’ disseminate in the social world, that is: “the ways in which meaning is constructed and conveyed by symbolic forms of various kinds” (as cited in Wodak, 2001, p. 10). In this sense, the study of ideology involves a systematic examination and scrutiny of social contexts where symbolic forms are utilised as to determine relationships of domination (ibid.). Similarly, Fairclough sees ideology as an interpretation of reality that is constructed as a means to power legitimisation (Fairclough, 1995, p. 14) and, therefore, ideology composes an important element in the establishment and maintenance of ‘unequal power relations’ (Wodak, 2001, p. 10). An important aspect to note is that, as Wodak points out, for CDA, language ‘is not powerful on its own’ but it rather acquires power as it is used by powerful people (2001, p. 10).

Amongst CDA scholars, van Dijk proposes an approach towards a theory of ideology from a “multidisciplinary, sociocognitive and discursive” point of view (van Dijk, 1995b, p. 244). Arguing that earlier definitions of ideology are rather “vague philosophical” or “sociological jargon” (1995b, p. 244), van Dijk sets out to make explicit, amongst other elements, relationships between ideology, discourse and social practices. van Dijk’s definition of ideology is quoted here at length:

Ideologies are basic frameworks of social cognition, shared by members of social groups, constituted by relevant selections of sociocultural values, and organized by an ideological schema that represents the self-definition of a group. Besides their social function of sustaining the interests of groups, ideologies have the cognitive function of organizing the social representations (attitudes, knowledge) of the group, and thus indirectly monitor the group-related social practices, and hence also the text and talk of members. (1995b, p. 248)

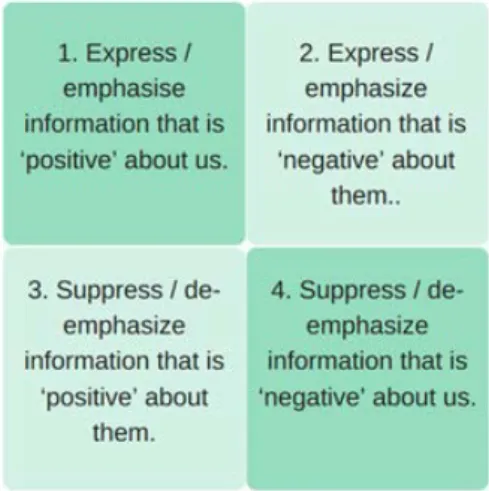

Within his definition, ‘values’ constitute an important concept. According to van Dijk, ideologies are evaluative, forming the underlying foundations for judgements around what is ‘good or bad, right or wrong’, which in turn sets common guidelines for social