Interaction Design One-Year Master 15 Credits

Spring Semester 2020

Supervisor: Anne-Marie Hansen

Connectedness

Designing interactive systems that foster

togetherness as a form of resilience for

people in social distancing during Covid-19

pandemic.

Exploring novel user experiences in the

intersection between light perception, tangible

interactions and social interaction design

(SxD).

Abstract

This thesis project explores how interactive technologies can facilitate a sense of social connectedness with others whilst remotely located. While studying the way humans use rituals for emotional management, I focused my interest on the act of commensality because it is one of the oldest and most important rituals used to foster togetherness among families and groups of friends. Dining with people who do not belong to the same household is of course hard during a global pandemic, just like many of the other forms of social interactions that were forcibly replaced by the use of technological means such as video-chat apps, instant messaging and perhaps an excessive use of social networking websites. These ways of staying connected, however, lack the subtleties of real physical interaction, which I tried to replicate with my prototype system, which consists of two sets of a lamp and a coaster which enable to communicate through light and tactile cues. The use of such devices creates a new kind of ritual based on the simultaneous use of the devices by two people, thus enabling a new and original form of commensality that happens through a shared synchronized experience.

Keywords

Research Through Design; Interaction Design Technologies; Interaction Design; Commensality; Social Connectedness; Social Resilience; Remote Communication; Tangible Interaction; Tangible User Interface; Shared Experience; Covid-19 Pandem-ic; Social Distancing; Tangible and Embedded Interaction; Internet of Things (IoTs).

Table of Contents

2. Research Questions 5

3.Thereoretical Background 6

3.1 Designing in and for a crisis: 6

the pandemic crisis & mental health 6

3.1.2 How loneliness is taking its toll 7

3.1.3 Blurring boundaries: finding connection and resilience 9

3.2.1 Rituals & emotional contagion 10

3.2.2 From regulating emotions to social connections: rituals 11

3.2.3 A universal medium and shared experience, a specific ritual: Commensality 13

3.3 Looking for connectedness: challenges of communication technologies 14 3.3.1 Remote-mediated commensality 14

3.3.2 From words to nonverbal communication 14

3.3.3 Communicate beyond the screen: bridging touch, tangible interactions and IoTs 15

3.4.1 From awareness to connectedness: 16

Experience design in Social Interaction Design (SxD) 16

3.5 Canonical examples 19

3.5.1 LumiTouch 19

3.5.2 Friendl 20

3.5.3 Touch & Talk 20

3.5.4 CoDine 21

3.5.5 The Presence Table 22

4. Methodological approach 23

4.1 Research through Design (RtD) 23

4.2 Literature review 23

4.3 Online and participatory observations 24

4.4 Semi-structured interviews 24

4.5 Online survey 24

4.6 Cultural probes 25

4.7 Affinity Mapping 25

4.8 Sketching and material exploration 25

4.9 Prototyping 26

4.10 Usability testing: experience prototyping and retrospective think-aloud method 26

5.1 Design Process 27

5.2 State of the field research 27

5.3 Design Process & Methods 27

5.3 Fieldwork & Ethnographic research 28

5.3.1 Online and participatory observations 28

5.3.2 Semi-structured interviews 31

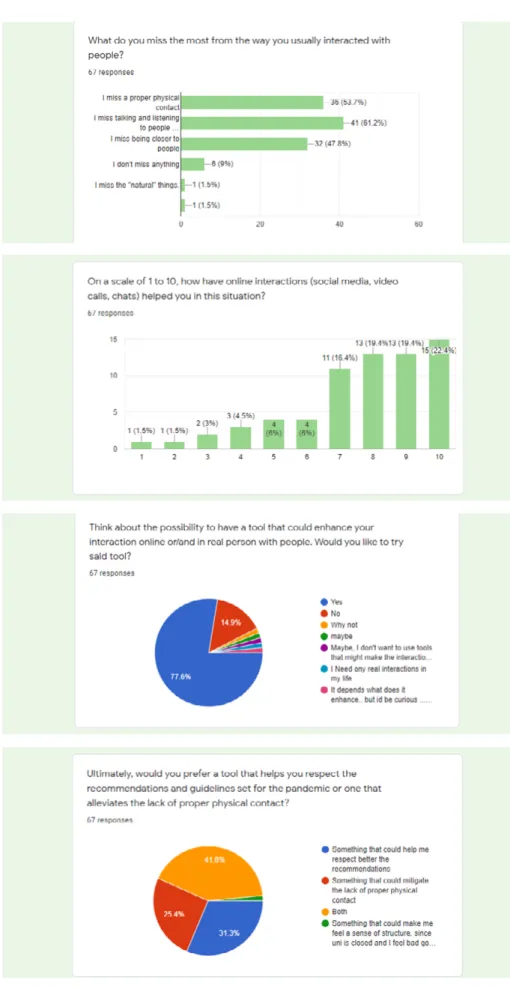

5.3.3 Online survey 33

5.3.4 Cultural probes kit 36

5.4 Initial data analysis and evaluations through affinity mapping 41

5.5 Ideation 44

5.6 Prototyping 47

5.6.2 The prototype system 49

6.Results & Analysis 59

1. Introduction

“There are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks where decades happen” is one of the quotes that is frequently attributed to Vladimir Lenin, supposedly describing the events of the Russian Revolution.

The years from 1917 to 1923 were indeed tumultuous ones not just for Russia, as the world was in the midst of the first global war and saw the outbreak of the deadliest pandemic in history. Just as the First World War and the Russian revolution, the Spanish flu is something very few people alive today can remember directly. As a result, the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic is an unprecedented event for almost everyone on the planet (Bao et al., 2020). For the first time in a century, it seems everyone is affected by the same problem, no matter where they live or who they are, and cooperation is of the essence. People all over the world have turned to technology to try and restore their social habits, which, for the most part, include close physical contact, now made impossible by social distancing regulations. Technology has, in the last 30 years, made it possible to be connected in previously unimagi-nable ways. However, videocalls, instant messaging and the likes still have not managed to adequately mimic real physical interactions. The lack of social contact has led many to feel lonely and disconnected and, as a result, many have tried to replicate forms of social interaction through the use of technology: many apps and other products have been developed to meet the needs of a population in need of human connections.

In such a scenario, it is vital for Interaction Design to play its role in the field of pandemic crisis management by experimenting with new and innovative design projects that can help people in maintaining stable social interactions, which are vitally important when it comes to their mental health during these times.

By using a Research Through Design (RtD) methodological approach, this thesis is aimed at understanding how to help people cope with their current living situation, namely under more or less strict social distancing rules during the 2020 COVID-19 outbreak.

The focus of this project is to explore how interactive technologies can foster togetherness as a form of resilience for people in social distancing and therefore which are currently remotely located. According to Zimmerman et al. (2010), it is through the design practice methods and processes deployed that RtD is considered a fruitful method of investigation (p.310). By adopting a human-centric perspective to understand how interactive technologies facilitate social relations and shared activity while being remoted located and we explore the implications of these socio-physical relations about the design of new interactive technologies that promote social interactions.

In line with Zimmerman et. al, this project employs methods and design artefacts to generate knowledge contributions, bringing together research and design, with the intent of turn our attention not only to the present or the past, but to the future (Zimmerman et al., p.310, 2010).

Accordingly, in regard to RtD, the focus on the future together with the focus on concretely defining a preferred state “allows researchers to become more active and intentional constructors of the world they desire” (p.310), by engaging in a discourse on ethical considerations about what we, as designers, design.

Therefore, this thesis intends to contribute in finding new ways to help people in these trying times building upon current theories of social interaction design, psychology of rituals and designing for social crises. By giving people a way to stay connected in a more meaningful and playful manner, and, in doing so, tend to their emotional (and physical) needs in order to create the right circumstances to collectively find a solution to the current situation. Building upon the research notion advocated by Zimmerman, Stolterman & Folizzi (2010) where research is depicted as “a way of broadening the scope and focus of designers, of challenging current perceptions on the role and form of technology” (p.311). Therefore, it is through the exploration of the role of technology that this research intends to promote and support social resiliance. To do so, I formulated three research questions that proved to be essential in the development of both the theoretical background, the process and design outcomes.

2. Research Questions

RQ 1: How can interaction design technologies, remotely connected, support the feeling of social

connectedness between people during physical distancing?

RQ 2: How can interaction design features, of four online connected artifacts, enable a synchronized shared interaction between two people remotely located?

RQ 3: How can interaction design features, of an artefacts’ system, recreate a sense of togetherness

3.1 Designing in and for a crisis:

the pandemic crisis & mental health

Many are the bodies and organizations interested in design for crises that contributed to promising results. Pioneers among all researchers are Yoko Akama and Ann Light (2012), both committed to cultural sensitivity, diversity, and participation to pursue a design practice that deeply engages with communities. Throughout their research they refer to the Information and Communication Technology (ICT), claiming that there is strong evidence that ICT is now used in facilitating social networks in both pre- and post-disaster contexts for bushfires, earthquakes, hurricanes and floods (e.g. Akama, 2012).

Whilst research into disasters of other entities such as fires and earthquakes has been detailed by today’s research, little has been heard of research into pandemics, such as malaria or the first SARS pandemic. This research could thus benefit the field of pandemic emergency and contribute to the knowledge just as other disciplines do. Furthermore, Light and Akama mention that “when participatory design work no longer takes the workplace as its domain but attempts to tackle bigger societal and environmental issues, the facilitation role increases in complexity,” (Light & Akama, 2012) but I would argue that a situation in which everyone can be affected (by the virus, in this case) and has to work towards a common goal to tackle the situation can have the opposite effect.

As the spread of COVID-19 started, so does the amount of research about the new virus. Much has been investigated about its nature and constitution and research is needed both to contain the pandemic and to make the world’s population always up to date on the current state of the number of people infected, the healed and the dead. The World Health Organization and health authorities have informed the world population since the first outbreak of the virus, announced in December 2019. First among these the World Health Organization and international authorities which recommended the adoption of containment measures to contain the virus’ diffusion. Among the various recommendations, WHO stressed the importance of a possible impact on mental health well-being resulting from both the sudden and worldwide nature of the virus and the restrictions which the world community is undergoing (World Health Organization, 2020a). It is indeed considered equally as important to investigate mental health well-being, especially in conditions where our interaction paradigm has been paused. Despite this, understandably, medical researchers have priority for a vaccine to be found soon, and there is not that much research on the effects that social distancing, and other forms of containment, are having on the world population at a psychological level. And in this specific regard, there is also the necessity to enrich the field Interaction Design in terms of designing for crises. All this should be observed and considered so that psychological demands can be met. From an interaction design perspective, it is an opportunity to also investigate the mental health area and be supportive of institutions, including health care and households. To outline my research framework, it is appropriate to start from the analysis of the restrictions adopted by nations in order not to overlook their impact on our lives.

3.1.2 How loneliness is taking its toll

An outbreak of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19), a cluster of acute febrile respiratory illness, was first reported in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 (Paules et al., 2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19) has spread subsequently to the rest of the world causing this respiratory disease to be a global pandemic. Nations around the world are taking measures to contain the number of infections, among which social distancing, self-isolation, and quarantine. The preventive measures quoted here above are aimed at reducing the total number of people infected at any given moment, thus flattening the curve of the pandemic.

The term social distancing refers to a variety of measures which aim to increase the physical distance between people. Indeed, according to the dictates of social distancing, if everyone limits their contact with people and public places, they can limit the spread of the disease. This practice is based on three main strategies. The first limits the physical interaction between people who come face-to-face; the second is to limit the size of gatherings – this decreases the likelihood that an infected person will be there. Thereby, social activities are cancelled or closed (i.e. closed schools, cancelled events, and shut down businesses like bars and movie theatres). The third is to follow the Stay at Home orders, which are designed to reduce personal interactions, except for minimal interactions to ensure vital supplies or in need to seek medical attention. All these listed measures of contagion containment help ensure that healthcare facilities have the bandwidth to give quality care to everyone who needs it. On the other hand, these measures “have very real costs—including psychological ones” (Brooks et al., 2020)” (Limcaoco et al., 2020). Indeed, according to the report 57 in March 2020, although the World Health Organization (WHO) and the competent health authorities are operating to contain the pandemic, “this time of crisis is generating stress by the world population” (World Health Organization, 2020b). This source of stress is represented by fear and anxiety and, consequentially, might be overwhelming and cause strong emotions in adults and children. Moreover, public health actions such as social distancing can make people feel isolated and lonely and can increase stress and anxiety. The most common feelings are those of social isolation which come to play when dealing with social distancing and loneliness. These specific negative emotions are associated with having fewer interactions with other people, due to the loss of our social lives. According to professor Cacioppo (2006), this results in a disruption in our usual interaction patterns, in other words, we are forced to act against our human nature.

“Humans are not particularly strong, fast, or stealthy relative to other species. They lost their canine teeth thousands of years ago and they never had the safety offered by natural armour or flight. It is the ability to think and use tools, to employ and detect deceit, and to communicate, work together, and form alliances that make Homo sapiens such a formidable species.” (Cacioppo et al., 2006)

It is, indeed, the ability to create relationships, networks and share that distinguish our species from others on planet earth, and when our communication paradigm is interrupted this could result in many feeling disenfranchised and powerless.

There is a lot of research that suggests people feel happier and more socially connected when they spend more time interacting with others, and that social interaction and social support are related to improvements in health and wellbeing (Berkman et al., 2000). According to Sun et al. (2019), this state of well-being is been nurtured for hundreds of thousands of years as an individual’s survival has depended on the nature of the interactions with other humans (Sun et al., 2019). Social relationships come to play an evolutionary adaptive value; according to some, it is through sharing and collaboration with others that we ensure reproduction and survival of our species (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Cacioppo et al., 2014; Spithoven et al., 2017). This derives from an innate “need to belong” that leads human beings to have “a pervasive drive to form and maintain at least a minimum quantity of lasting, positive, and significant interpersonal relationships” (Baumeister & Leary, 1995,p.).

Recent studies have gathered a considerable amount of information about stress management during health crisis thanks to studies conducted during SARS, H1N1, and Ebola outbreaks. Baum et al. (2009) stated that public safety measures often lead to increased rates of depression and anxiety in the community. Furthermore, those rates are even higher for people with high exposure, like healthcare workers and people with certain mental health conditions, which may be more vulnerable. Therefore, when social connection and interaction is not always ensured, e.g. when social distancing is mandatory, our behavioural reaction might lead us to increased levels of stress and anxiety, due to negative feelings, i.e. loneliness. Conforming to Spithoven et al.’s (2017) study, experiencing loneliness could increase stress levels, and in some instances even expose to mental disorders. More specifically, “loneliness has been related to physical health problems, such as obesity, sleep problems, elevated blood pressure, and diminished immunity, as well as mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem” (Spithoven et al., 2017, p.98).

Within public opinion and psychologists, experts have suggested that as we are frightened by an economic recession, we should be equally concerned about a possible social recession—"the psychological impact of quarantine is wide-ranging, substantial, and can be long-lasting” (Limcaoco et al., 2020). Moreover, “continued pattern of distancing socially, beyond the immediate pandemic, that will have broader societal effects” (Wright, 2020b). For instance, the possibility to have more people affected by depression, as well as more people afraid of spend time with others could be a potential risk.

As shown in the above studies, since the risks for our society for mental health well-being are high, the necessity for continuous research in psychology is imperative. As assessed by experts, crisis times can cause a series of imbalances which may adversely affect our lives. It could increase psychological stress, raise anxiety levels, cause affective and cognitive alterations this due, more specifically relevant for this research, to the decrease in social interaction.

Coming to agree with The New Yorker (March 2020)– “Loneliness is not just a feeling. It is a biological warning signal to seek out other humans much as hunger is a signal that leads a person to seek out food, or thirst is a signal to hunt for water. Historically, connections have been essential for survival. During the coronavirus pandemic, the loneliness signal may increase for many—with limited ways of alleviating it” (Wright, 2020b). Such ways may include relatively common video chat apps such as Zoom and Houseparty or, as is the case for the prototypes of this thesis, the Internet of Things.

3.1.3 Blurring boundaries: finding connection and

resilience

Despite loneliness itself being related to various forms of maladjustment, psychologists affirm the feeling of loneliness might be adaptive, as it increases the likelihood of survival through promoting social contacts. In this regard, Cacioppo et al. (2006) affirm that “the social pain of loneliness and the social reward of connecting with others motivate the person to repair and maintain social connections even when his or her immediate self-interests are not served by the sharing of resources or defence”. Indeed, loneliness is a cue of threatened belongingness needs that acts as a drive to re-establish and preserve social bonds.

According to Spithoven et al. (2017), since loneliness is a burdensome experience, defeating the negative emotions that it instils would be perceived as an intrinsic reward (p.97). Besides, it must be underlined that the “double” nature of loneliness goes hand in hand with, as previously anticipated, the “need to belong”, also known as “the desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation” (Baumeister & Leary, 1995).

This important desire can contribute to our mental stability and social interaction, having “multiple and strong effects on emotional patterns and cognitive processes” (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Consistent with the belongingness hypothesis, people form social attachments readily under most conditions and “resist the dissolution of existing bonds” (p.497).

In this specific pandemic circumstance, it might be vital to investigate the potential of this “the need to belong” and it should be fruitful to think about it as a means of resilience for the global population. It is with this urge that the formation of our resistance is ensured. It is attributed to our resilience in maintaining social bonds, and it occurs also in adverse circumstances. Indeed, adverse circumstances can strengthen bonds and, according to Baumeister and Leary (1995), detrimental conditions would even be compelling for the formation of social attachments. Furthermore, it has been stated by researchers that a bit of stress may act as a catalyst for positive change from a state of dissatisfaction and stress to one of problem-solving and resolution. Indeed, overcoming stressful events can make us more resilient, and doing this together could even be more beneficial for our relationships (Baumeister & Leary, 1995).

According to some researchers, the mere presence of other people can be comforting (Schachter, 1959; Baumeister & Leary, 1995). In this regard, it must be underlined that both loneliness and the need of belongingness could contribute to the activation of what is called our “coping mechanism” which help us react, defeat negative feelings, and resist uncertainties. This might be, more than ever, a resource during the pandemic crisis.

In this specific situation, possible connections between these theories and our present reality could be drawn. Indeed, it could be highly observable among public opinion and social media communication that as soon as people started to apply social distancing, also sought to find new ways of connecting each other.

Social media shows how people are having video calls and birthdays at a distance in an attempt to recreate the cosiness of parties and events online. The desire of establishing social relationships relies on the need for social interaction; this innate desire could lead us to find creative alternatives in the way we communicate and, consequentially, to

the foundation of new communication trends. Indeed, according to public opinion, a coronavirus culture is emerging, spontaneously and creatively, “to deal with public fear, restrictions on daily life, and the tedious isolation of quarantine and social distancing” (Wright, The Newyorker, 2020a).

“One of the amazing things about the human species—once harmless critters not much more than monkeys running around—is that, over time, we have become very creative. We have adapted to survive. That’s what people will rely on now—coming up with incredibly imaginative ways to find connections even when they’re not in the same physical space together” (Wright, The Newyorker, 2020a). Moreover, “when these rituals go missing, there is something resourceful and insistent in the human spirit requiring us to create rituals anew” (Imber-Black, 2020).

Within these considerations, it is important to reflect upon the type of circumstances we are prompt to live and the possibility to draw some important considerations concerning design opportunities. As shown above, there might be a positive by-product of the pandemic.

Indeed, for the past century, human life has focussed increasingly on money and material belongings, which, especially with technology, led to a disregard of human relationships. Now that we are suddenly constrained at home, the best means of surviving, psychologically and biologically, is to interact with people by whatever means available. And as mentioned before, the urge for being in contact created the formation of new rituals that take place through the means of technology and new communication tools.

3.2.1 Rituals & emotional contagion

COVID 19 set upon us, unanticipated, and unimagined by all who were not scientists and medical doctors. Children were unexpectedly required to be homeschooled by parents who were either suddenly unemployed or working from home; old people were left in their loneliness and friends were far apart. The master class I attend was swiftly moved online, along with undergraduate and graduate classes everywhere. Therapy sessions, smart working and meetings went to FaceTime or Zoom video calls. Our television screens and the internet were imbued with illness and death infographics and talks. With the advent of social media, we try to keep our contacts alive and, with them, the rituals that characterize our societies. And yet, now more than ever, we need new channels of communication. Just when a pandemic has involved everyone, part of the support to stay in touch with others is represented by media, namely video calling, chats and social media.

Therefore, it is through the observation of the rituals during Covid-19 born online that this project has taken shape. During the process, I found myself aligned with Imber-Black (2020) regarding the formation of rituals “which bent but did not break During COVID-19” (Imber-Black, 2020). Indeed, as anticipated before, new rituals were created, designed, and invented that captured and expressed the current moment, often helped by technology. Our rituals shape us, sustain us, and connect us against the threat of social disconnection.

Among public opinion, it is said that — "over time, the impact of the novel coronavirus may be so sweeping that it alters human rituals and behaviours that have evolved over

millennia" (Wright, The Newyorker, 2020a). By exercising resilience, we have created channels for the support of such rituals and with them the hope that they can carry out their task in our lives despite the restrictions. To better understand the value of these rituals for social interaction, it is vital to analyse the functional paradigm which they consist of.

3.2.2 From regulating emotions to social connections:

rituals

It has happened to anyone, at least once in their life, to attend the birthday of a dear friend/s, or a relative; to greet someone by hugging him or shaking his hand; to toast to a particular event or to sit at the table and eat with someone. This is just a small list of rituals (among an infinite variety) that pervade a human life from birth and follow us through our daily lives. Rituals may provide us with a steady resource of connection, “whether as daily rituals for partings at the start of a school and workday, greetings when we return to one another, meals and bedtime” (Imber-Black, 2020).

Notwithstanding, we often overlook their regulating functions as we enact them, but actually, it is acknowledged that rituals serve many psychological functions (Boyer & Liénard, 2006). Indeed, Hobson et al. (2018) delved in depth on this topic formulating a framework of three primary regulatory functions, which are: the regulation of emotions, performance goal states, and social connection.

As a means of research in this project, the attention lies primarily on the regulation of emotions and social connection. The combination of these features generates a ritual experience which relies on bottom-up and top-down mental processing respectively, the convergence of these two processes regulates our psychological states which result in “both individual and social-based outcomes” (Hobson et al., 2018).

The bottom-up processing engages us through the recruitment of perceptual, attentional and memory stimulus features and refers to the sensorimotor elements of ritual, hence, the experience or enactment of specific physical actions. Indeed, the actions are characterized by rigidity, formality, and repetition. For instance, we can consider the toasting ritual which has a specific movement pattern that involves eyes, hands, and coordination. According to the experts, this represents a form of event segmentation that involves a cognitive process that “economized perception and guides attention” (Newtson, 1976; Zacks & Swallow, 2007; Zacks, Tversky, & Iyer, 2001)” (Hobson et al., 2018). In other words, due to the enactment of rigid actions, rituals are more attention-grabbing, and this gives them a memorable connotation. On the other hand, top-down processing is associated with “the integration of physical motoric features into broader narratives, appraisals, and interpretations” (p.264). Indeed, it is thanks to this process that rituals are considered meaningful, and it is possible to connect oneself to traditions, cultural and religious groups.

Associated with the improvement of emotional well-being, according to Hobson et al. (2018), experiencing an emotional or social deficit should elicit more ritualistic behaviour. Rituals are enacted to regain a sense of personal control and it is demonstrated that rituals are more likely to emerge when performers experience an emotional deficit. From the bottom-up processing, the act of performance may direct attention away from one’s emotions and in this regard, Boyer and Liénard (2006)

mantain that the physical action units of ritual engage a stream of working memory that temporarily dispels anxiety. Indeed, in accordance with Hobson et al., by enacting rituals, people start focusing on synchronizing gestures, body movements, voice and intonations, rather than an anxiety state. In this way, they activate a subconscious cognitive process that leads to allay the tension thanks to shifting the focus on movements and synchronization (Hobson et al., 2018).

On the other hand, due to the top-down processing, enacting rituals should reduce these deficits through the positive feeling of having completed a procedure attributed to a ritual. It is compelling to find connections in our reality in this current situation— when the socio-emotional deficit is stated—therefore, the need to regain control is craved. Consequentially, enacting rituals should reduce these deficits.

On a social connection point of view, Durkheim (1915) asserts rituals can build affiliation with group members, creating a sense of collective unity.

Following his line of theorizing, a ritual could represent an effective “mediating social mechanism,[…] it strikes a balance between opposing social and interpersonal forces (Hobson et al., 2018). Arguably, someone could assume that experiencing a deficit of social connection during uncertain times (e.g. the coronavirus situation) could lead us to a reduction of rituals. As stated by Hobson et. al. (2018), evidence to the contrary demonstrated that lacking affiliation increases ritualistic behaviour. Indeed, we often saw people having dinner (mealtime ritual) together e.g. on Zoom (video calls) and this might empirically provide tangible evidence of this tendency.

Following the line of theorizing, enacting a ritual could make the affiliative deficits disappear. Durkheim (1915) stated that collective rituals contribute to group cohesion due to shared attentional and emotional experiences, driving to a joint perceptual emotional contagion namely “collective effervescence”.

Coming to agree once again with Hobson et al. (2018), the call to perform rituals is based on the performance practice that would be able to "lead to joint attention, perceptions of emotional synchrony and self-another overlap" (p.270).

This thanks to the elicited synchronization of behaviours which generates a strong sense of oneness and cohesiveness. Moreover, in meaning creation and transference, a ritual generates feelings of self-transcendence, allowing a person to escape ego-based thoughts and anxieties.

Channelling the actual situation in the world with these theories could lead to thinking that certain rituals could be explored more employing technology—going beyond chat, calls and video calls. In my opinion, there is still potential and interactive technologies could be the key to the investigation.

It is in fact within these considerations that this project takes place, which aims to bridge emotional well-being and technology. Offering a transition from psychology, it turns to the involvement of technology and its potential in solving physical and social barriers. Besides, it shows how emotional contagion and the study of the mechanism of rituals—exploring all the ways that these intersect with human experience—contribute to social interaction, interaction design and HCI.

Moreover, according to Imber-Black “when the shutdown finally becomes a memory and some of the newly invented rituals slip away, I predict that many will maintain as discoveries of our creativities, our capacities, and our requirement for the human connections rituals provide” (Imber-Black, 2020). This project aims to support this statement and, in line with what Imber-Black (2020) stated, this could be fruitful not

only for the management of togetherness in uncertain times for future purposes, but also to involve these psychological mechanisms and sources more frequently in the Interaction design arena.

3.2.3 A universal medium and shared experience, a

specific ritual: Commensality

From the Roman feasts to the most important festivities of the year, the act of gathering around a table to eat a meal, also known as “commensality”, remains one of the most widespread and recounted rites throughout the history of the human species. Being together around a table eating a meal and drinking is a daily event so mundane, so ordinary that it is often taken for granted. Indeed, it is also a central part of social relationships and cultural rituals, as well as “a symbolic and a material means of coming together” (Fieldhouse, 2015). According to Szatrowski (2014), mealtime is a social activity and, in comparison with other social activities, it is considered a central part of our life. “It is through food that we celebrate, share, connect and strengthen the ties that bind us” (Hamilton & Wilson, 2009; Ochs & Kremer-Sadlik, 2013).

Indeed, Fieldhouse (2015) holds the view that “food sharing is an almost universal medium for expressing sociability” (Fieldhouse, 2015). For this specific connotation, it is considered the most frequently repeated social activity (Fiese et al. 2018). Even though food and mealtimes are constantly influenced and reinvented depending on the era and culture, mealtime continues to be an opportunity to strengthen bonds for loved ones. Whilst it is vital for the formation and stability of a family, it enhances the health and well-being of family members (Hamilton & Wilson, 2009, p.346). Moreover, eating together with others is also a personal experience, that helps to restore personal well-being in the act of “give and take” during a mealtime (Fieldhouse, 2015). This act of share meals, drinks, or a snack, happens in every single culture and not only at home. For instance, it is a common tendency to go to restaurants with ones family, lovers, or friends. All these activities are quite widespread in every single country in the world. As Szartrowski et al. (2014) put it since sociality goes hand in hand with commensality, they are closely linked (Fiese et al., 2008). Therefore, by its combination of characteristics—informality, the intimate nature and versatility—commensality’s power to dramatically change social relations is evident.

Following this line of thought, the ritual of commensality results to be the most universal ritual for both bonding relationships and restoring personal well-being. However, the pandemic puts its universality in jeopardy due to factors such as social distancing and gathering restrictions. It becomes therefore a priority for the design of this project to explore alternatives in an attempt to help to restore this important ritual.

3.3 Looking for connectedness: challenges of

communication technologies

3.3.1 Remote-mediated commensality

While the coronavirus limited the possibility to gather as a restriction, especially for those who live away from each other, the speedy rhythm of modern life has reduced the opportunities for families to have meals together. In this regard, a recent study demonstrated that families want to eat dinner together, but lack the time or resources to achieve their desires (Snyder et al., 2007). For many, dinner around the table is a time to reaffirm cultural and familial identity, values, ideals (Larson et al., 2006). Unfortunately, advances in technology are dragging people into the digital lifestyle, full of virtual communication, but lacking a sense of cosiness and intimacy.

Furthermore, nowadays’ remote communication allows primarily text-, voice and video messages, voice, and videoconferencing, means as such are apps like WhatsApp, Zoom or Houseparty. With the pandemic, among public opinion social media show how people are having video calls and birthdays at a distance in an attempt to recreate the cosiness of parties and social gatherings online. One possible direction could be expanding the meaning of conversations on videocall platforms by developing new extensions that enrich the digital experience (Miller, 2020), or as this thesis aims for to create new tangible types of interactions for a different form of remote communication. According to Ogawa et al., remote communication methods and technologies such as email, messaging, videoconferencing, and calls, are not able to convey rich interactions between people and therefore some important subtle signals, such as touch and non-verbal cues, are destinated to get lost in the communication (Ogawa et al., 2005). Following this line of theorizing, it should be fruitful to consider physicality to enable a more significant contact in remote communication, introducing tangible interactions to support this communication and find new resources.

3.3.2 From words to nonverbal communication

While the social importance of dinnertime inspires my vision, it is important to understand how to reconnect people through technology that enhances co-presence, thus it is important to define the basis of communication.

Finding myself in accordance with Haque (2016), by creating a physical link and incorporating the use of tactile interactions in the communication, it would open a new channel for nonverbal communication while being remotely connected through technology (Haque, 2016). As stated previously, the ritual of commensality relies on several interactions, these rely primarely on nonverbal communication which involves all our five senses at the same time, namely eyesight, hearing, olfaction and taste. Focusing on the sense of touch, Knapp et al. (2013) put that touch is particularly essential in nonverbal communication (p. 182) and it is for this reason that it becomes an important element for the foundation of this project.

define it as the combination of all human interactions that goes beyond speaking or the use of words (Knapp et al., 2013). According to the experts, while we are communicating, we can be aware of our actions and we can commonly control our responses through words or movements (Knapp et al., 2013). But we can also communicate through nonverbal cues which are instead more spontaneous and of which, to some extent, we are less in control. Indeed, the brain deploys a specific hemisphere of our brain (the right one) when it comes for the processing of nonverbal signals. Therefore, building upon what Knapp et al. explain, nonverbal communication should be viewed as a significant part of the whole human communication process. As it is also through nonverbal communication that we express, and it allows us to go beyond words, messages, talks and it represents an important part in our everyday life since “it facilitates an enormous amount of informational cues” (Knapp et al., 2013).

In a social context where the communication pattern is not always ensured, a new way to reinvent certain mechanism must be investigated, and technology use is at the essence.

3.3.3 Communicate beyond the screen: bridging touch,

tangible interactions and IoTs

Several significant studies have been dedicated to human touch and, even more considerable for this project, how they are integrated and developed in the HCI and Interaction Design fields. This investigation spans from an introduction to the sense of touch, towards the realm of tangible interactions and the Internet of Things.

According to Hertenstein et al. (2006), touch is vital for the foundation of human social life. Indeed, it is the most developed sensory modality at birth and throughout infancy and childhood it supports cognitive functions, brain, and socioemotional development (Hertenstein et al., 2006).

In comparison with other non-verbal communications, such as facial expressions and bodily gestures, touch is considered the main channel for expressing intimacy, impact, and feelings (Field, 2014; Morrison et al., 2010). As Morrison at al. (2010) put it, touch creates feelings of social presence due to involvement of physical interaction and co-location; indeed it can “mediate social perceptions in various ways” (p. 305). Touch can serve as a communicative way to convey thoughts and feelings to regulate them in others or for oneself (Hertenstein et al., 2006; Morrison et al., 2010).

Within theories in psychology and anthropology, the sense of touch has been and continues to be fundamental in Interaction Design. For instance, in the formation of a tangible interface. Indeed, while physicality plays a fundamental role in interpersonal communication, GUI-based systems for distributed interactions do not provide any physical communication (Brave et al., 1998). Thus, touch it has been the foundation of many new challenges for design which present the prerequisite to designing not only digital but physical. As Ishii & Ullmer (1997) theorize, one of the loci of computation it is found in the physical environments we inhabit. They propose to allow users to “grasp & manipulate bits in the centre of users’ attention by coupling the bits with everyday physical objects and architectural surfaces” (Ishii & Ullmer, 1997). With this, they introduced Tangible User interfaces as an alternative to the GUI that makes greater use of physical space and real world objects as interface tools. The tangible

Interfaces represent a general approach to human-computer interaction that puts greater emphasis on physicality than tradition graphics-based interfaces. One of the resulted projects theorized on this basis is ambientRoom. In this context, the attention is on the integration of computational augmentations into the physical environment, taking advantage of the “natural physical affordances” to achieve “heightened legibility and seamlessness of interaction between people and information”(p.2). Conforming to Hartson “a physical affordance is a design feature that aids, supports, benefits, or enables physically doing something” (Hartson, 2003). According to the experts, the integration of haptic elements, like a button or a shape, to a digital device could lead the interaction with the user to a better understanding of the functionality of tools and, thus a smoother and seamless interaction. Following this theorizing, Peterson in defining haptic devices stated that “although physical touch is often associated with proximity and intimacy, technologies of touch can reproduce such sensations over a distance, allowing intricate and detailed operations to be conducted through a network such as the Internet” (Paterson, 2006). This opens the doors to the world of synchronization and tangible presence. In the theorization of these, while users can make full use of their hands and bodies and use their spatial kinaesthetic senses, they share physical objects and environment. This provides a deeper sense of cohesion since what it is shared, following what it was stated before, represents a tangible and graspable presence.

In line with the expert Holmquist (2019), rather than talk about interfaces and interaction, designers should reckon digital artefacts more “holistically”(p.4). According to his research, already the boundaries between hardware and software are starting to disappear, leading to a new class of hybrid digital-physical products. Besides, Stankovic affirms that the world will be overlaid with sensing, embedded in “things”, creating smart (Stankovic, 2014). This revolution in digital products is already manifest in areas such as the Internet of Things (Holmquist, 2019; Leppänen et al., 2017; Stankovic, 2014). Indeed, Leppänen et al. (2017) present the Internet of Things (IoTs) vision as defined by a global network of interconnected services and smart objects that support humans in everyday activities through sensing and communication capabilities (Leppänen et al., 2017). With the help of IoTs systems, the communication paradigm in technology becomes much more compelling, opening the world of communication technology to several experimentations. The focus is primarily on the implementation of human-to-thing, human-to-human and thing-to-thing interactions, made possible via Bluetooth or Wi-fi, as Parekh (2019) write in his review. Indeed, Wi-Fi has a “ubiquitous coverage” which makes it preferable for enabling IoTs connectivity. Within these considerations, this project aims to bridge mediated communication between people at the distance aided by tangible interfaces, IoTs and connected systems. Allowing connectedness between smart devices to enable connectivity between people.

3.4.1 From awareness to connectedness:

Experience design in Social Interaction Design (SxD)

Even before the advent of a pandemic crisis, social media communication and services are steadily permeating our everyday life and constantly revise the fabric of our social interactions. According to some, “as computing moves into the background andsmart objects and environments, designed interaction becomes embodied in everyday materials and artifacts”(Giaccardi et al., 2013). Furthermore, a scenario whereby socially substantial data is registered, and networked connections are produced based on our embodied interactions in physical spaces is foreseeable. Just as Giaccardi et al. (2013) put it “both in HCI and Interaction design the focus has been for some time on filling the gap between digital interaction and the material aspects of artifacts and systems (p. 326).

Firstly, plenty of research has explored new possibilities for translating embodied forms of expression into rich digital ones. In the meantime, studies have been conducted to embed digital information into interactive artifacts to populate our everyday world. Concurrently, “in social computing domains, there has been an investigation of how people can perform socially significant interactions through digital means” (p.326). Within this project vital was the exploration of the paradigm of Social Interaction Design (SxD).

Giaccardi et al. (2013) define Social Interaction Design as following—“it merges social data, social networks, and socially sensitive interactions with a view for expressivity in computing” (p.326). In line with the dictates of the experts, we as interaction designers should “embrace the fluid social practises of connectivity” and, in parallel, “we also need to facilitate “lived and felt” interactions with the social and material contexts where socially generated data are produced and shared, rather than just ‘adding’ social data over the material world as a flat layer of information and media content” (Dourish, 2012; Giaccardi et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2013). The major challenge for this project relies on the “third wave” of social computing which focuses on the integration of social and collaborative digital tools and everyday life. Thus, that concretize the interest in bridging this “third wave” of ubiquitous social interactions and tangible computing (Giaccardi et al., 2013). To fulfil this challenge, co-experience must be investigated in combination, as a means of enriching people lives with experiences through artifact-mediated activities.

Coming to agree with Wei (2011), most of the technologies available for connecting people at a distance provide them with “information exchanges and messaging systems” (p.23), instances as such are Facebook and WhatsApp chats or video calls. Very little has been done foster that goes beyond the mere exchange of a text, namely a shared experience. What characterizes experience is much more compelling in terms of user experience and involves the user in a process of meaning. As stated by Hassenzahl (2010) “experience is a story, emerging from the dialogue of a person with her or his world through action” (p.8). As a consequence, people elaborate on the experiences they “felt” in a meaning-making process (Hassenzahl et al., 2013). This process may aid users to reach a better overall experience, both with the device itself and the person he/she relates to through the device. As analysed previously in rituals enactment, while we enact in a certain action, we “experience” it and this facilitate the user in stress management. In an experience design scenario, a smart device could enable a shared experience like in a postmodern ritual, contributing to the creation of what Battarbee (Battarbee, 2003) defines as “socially created experiences, or co-experiences” (p.109). Indeed, interactive technologies can support co-experience through the means of mediated communication channels and shared physical activities. Just as Sanders (2001)

Figure 1. People using masks on the street during COVID-19 pandemic

& Battarbee (2003) put it “co-experience is the user experience, which is created in social interaction. Co-experience is the seamless blend of user experience of products and social interaction. The experience, while essentially created by the users, would not be the same or even possible without the presence of the product and the possibilities for an experience that it provides” (Battarbee, 2003). Since co-experience takes place as experiences are created together and/or share with others, it is driven by social needs hence communication and social relationships. This process can lead to an increase in feelings of connectedness by providing availability awareness and opportunities for sharing everyday life.

While smart objects can play a role by remapping social data onto objects that are a part of our daily routine, they can enable special kinds of awareness of people we care about. Linked to the research for making users aware of the remote presence of friends and family namely “awareness system”. Awareness systems were first investigated to connect remote worksites (e.g. Brave et al., 1998). As stated in the research carried out by Grevet et. al. (2012) “a more recent theme that has emerged in social awareness systems is achieving “connectedness,” or the positive feeling associated with an ongoing awareness of a social relationship (Dey & De Guzman, 2006)”(p.103).

Informed by these theories, the design focus was to mediate co-presence, for remotely located people, aiming to “social togetherness” during a commensality moment.

3.5 Canonical examples

The following paragraph represents the review work of the most pertinent explorations which contributed to this project. Motivated by the multi-faceted nature of this research, canonical examples are selected based on their pertinence, in line with the theories presented in the theoretical background. As the design interest in enabling a sense of togetherness for physically separated people increases, a great collection of works has been developed to enrich the HCI and Interaction. Thanks to this proliferation, this review spans from the analysis of remote connections, mealtime connectedness, intimate awareness systems in domestic computing, and social connectedness.

3.5.1 LumiTouch

LumiTouch (2001) is a picture frame interactive object, and it is developed by a group of researchers at the Media Lab. The LumiTouch frame concept picks up on this emotional connection and enables people who are physically separated to detect each other’s presence and communicate feelings. Moreover, it rapresents a lightweight presence but a valuable one.

In this work, the interaction is carried out through a photograph frame. This because in our imaginary a framed photograph represents a central keepsake for people, since it often stands in for a personal connection (Chang et al., 2001). It reminds us of moments in time and the emotions and experiences associated with them. We look at the people in the image and wonder about them, hope to be in touch with them. The interaction is enabled as the following. Lumitouch is deployed to two remotely separated people. Each of them has a LumiTouch frame at their location, and the two frames are connected over the Internet. When one of them squeezes the frame, the other friend’s frame lights up. The light colour shifts in response to how hard and how long the person grips the frame. One friend can simply enjoy the sentiment represented by the shifting colours on the frame or reciprocate by squeezing back.

3.5.2 Friendl

Friendls (2012) project consist of a set of interactive candles that enables remote communication while dining designed by a group of designers, Beuthel et al.

The prototypes deployed are designed for people located at a distance to connect each other through augmented candles. The candles are placed in a dinner setting environment and whenever the one users touch the candle, it lights up on the touched area. The interaction consists of touching the surface of the candle, thus while a person interacts with a candle, the other candle (remotely located) imitates the interaction on the other side through light cues. The peculiarity of the interaction relies on the synchronicity of the two prototypes, which enable the co-presence effect. Participants reported feeling of connectedness even if it was a lightweight interaction. The light emanated by the augmented candle affects the atmosphere, enabling a more pleasant mealtime experience. Since enabling synchronized interactions is a common feature of both Friendl and the presented project, the review of this work proves to be important for the development of the prototypes presented in this paper.

3.5.3 Touch & Talk

Touch & talk (2010) is a haptic interactive device developed by Rongrong Wang and Francis Quek. They developed a device for digitally mediated remote touch which allows affective interaction. In line with the discussion on the review literature in psychology and communication, touch represent an important medium in convey emotions and presence (Wang & Quek, 2010). Thus, touch based interaction can foster affect transmission and consequentially build connectedness between users. In Touch & talk the interaction has been enabled through the connection of three main elements: a microcontroller board that translate the pressure of a squeezable object into signals on a wristband. The user can squeeze the first device, enabling the measurement of the force which informs different haptic effects on the second prototype. As a predominant aspect of the system, touch and haptic affects are simultaneously reproduced. This

feature makes this project review of essence for the thesis here presented.

3.5.4 CoDine

Co-dine (2011) represents an interactive multi-sensory system for remote dining and it was developed by Wei and her team. The CoDine system provides a new solution for family bonding. It consists of a dining table embedded with interactive subsystems that augment and transport the experience of communal family dining to create a sense of co-presence among remote family members (J. Wei et al., 2011). The mutual presence is enabled thanks to shared dining activities which are gesture-based screen interaction, mutual food serving, ambient pictures on an animated tablecloth, and the transportation of edible messages. The innovation of this project relies on the intention of engaging interactive dining experience through enriched multi-sensory communication. Moreover, the projects present a resourceful number of interactive technologies: tactile sensors, subsystems and tablecloth which consists of thermo chromic inks combined with Peltier semiconductor elements and interactive screen. These series of feature and the overall aim of the project both invited the review of CoDine.

Figure 4. Touch & Talk components and prototype

3.5.5 The Presence Table

The Presence Table (2011) is a prototype that connects two households through an ambient, expressive interaction. It is developed as a reactive surface for ambient connection by Matthew Canton. The surface of the table illuminates and creates a reactive “trace” of human gestures and everyday objects (Canton, 2011). This trace is shared through a network connection to a linked surface remotely located. Indeed, this device is an embodiment possibility of ubiquitous computing in the domestic space. It is developed from design research with family members who lived apart but maintained a close sense of emotional connection. The main design characteristic is that the table senses gestures and give feedback without using a projector or external display. The system uses a camera inside the table, tracking data from a Community Core Vision1 application, and custom software created with Processing2. The software controls an LCD that sends light up to the fiber optic wires at the surface of the table. In the concept, the software records signals and transmit them across the internet to a paired table in another location.

4. Methodological approach

An overview of the methodological approach and methods that inform this project are presented in this section, focusing primarily on the main methods that informed the process. A more detail presentation of the methods will be presented In the Methods & Process chapter where I will detail the methods’ structure and expand on how I apply them and how they informed this project.

The project’s main methodological approach is Research Through Design (RtD) formulated by Zimmerman et al. (2010) and Gaver (2012). It is followed by a literature review method and ethnographic research conducted as participatory and online observation (Holtzblatt & Beyer, 2015; Martin & Hanington, 2012).

To further investigate people everyday lives subject to lockdown restrictions that currently affect all the nations in the world an online survey and derivable probes were used as in the case of Cultural Probes (Gaver et al., 1999; E. B. N. Sanders & Stappers, 2014) and piloted by the designer remotely. For the ideation phase I followed methodologies such as affinity diagramming, sketching, prototyping and ultimately an hybrid user testing characterizing by retrospective think-aloud protocol. Ultimately, the structure of the process was based on the four-stages design process promulgated by IDEO in The Field Guide to Human-Centered Design (2010), but also investigated by Frog throughout several case studies.

4.1 Research through Design (RtD)

Research Through Design (RtD) is the methodological approach that I followed throughout this project. According to Zimmerman et al. (2010), it is through the design practice methods and processes deployed that RtD is considered a fruitful method of investigation (p.310). Therefore, in line with Zimmerman et. al, this project employs methods and design artefacts to generate knowledge contributions, bringing together research and design, with the intent of turn our attention to the future of our projects and desires (Zimmerman et al., p.310, 2010). By adopting a human-centric perspective, I chose a RtD methodological approach aiming to understand how interactive technologies facilitate social relations and shared activities while being remoted located. I explored the implications of these socio-physical relations about the design of new interactive technologies that promote social interactions. Therefore, inspired by different theories from different research fields and disciplines, both the research and the design process intend to contribute to the field of Interaction design, communication technology and Social Interaction Design with substantial knowledge production.

4.2 Literature review

As a preliminar investigation a literature review was employed to explore relevant theories and to define the theoretical foundation of this project. The method was chosen to increase the knowledge of the thematic area and prior studies and to outline

the project’s direction. This method also included the exploration of the design arena in which the project aims to contribute in. Accordingly, this research referred to different search portals and databases namely ACM Digital Library, MAU Library, MitPress.edu, ResearchGate, and Malmö University Electronic Publishing.

4.3 Online and participatory observations

In the ethnographic research phase several research methods are chosen to gain a better understanding in relation to how people’s lives in order to inspire thoughtful designs that foster empathy (Martin & Hanington, 2012). Online observation is a type of ethnographic research that consists of the observation of online trends and social communication activities with the aim of gather knowledge of people’s lives and social changes. With this method, it is observable the behaviour changes and upcoming needs based on online trends. Together with online observations, participatory observation in the form of an ethnographic research method was conducted. According to DeWalt (2010), applying this method, the designer places himself in the user’s context as a “participating member” of his activities to immerse himself in his need and gain a comprehensive understanding of his experience while also observing the groups’ dynamics (Ellovich, 2011). This allows the designer to exercise empathy and inspiration together with the participant. In this method both the role of the observer and an active role are designer’s roles. This stage was vital to gain a better understanding and insights in relation to how people were experiencing social distancing and the other national restrictions , in order to find interesting scenarios to explore.

4.4 Semi-structured interviews

According to Hanington & Martin, “interviews are a fundamental research method to collect opinions, experiences, and perceptions” (Hanington & Martin, Interviews, 2012). For this reason, semi-structured interviews were chosen by the conductor (me) for the fieldwork, characterized by closed and open questions. With this etchographic method is characterized by the adaptation of questions and topics. Indeed the conductor is asked to guide the conversation but, at the same time, remain open to variations and changes depending on the interviews’ progression. It is thanks to the openess of this method that the designer can range from the research topics to considerations of any nature. This makes this methodology as efficient in qualitative data gathering as regular interviews thanks to the generation of deeper feedback and comments of participants.

4.5 Online survey

According to Hanington & Martin (2012), an online survey is considered an ethnographical method to collect information about “people’s feelings, behaviours, thoughts, and perceptions” (Hanington et al. 2012). It uses a method for collecting information from a larger amount of respondents, efficiently collecting “a lot of data

in a short period and are versatile in the type of information that can be collected” (Hanington & Martin, Surveys, 2012).

4.6 Cultural probes

According to Gaver, Dunne and Pacenti (1999), cultural probes are essential in Interaction Design research, in particular for conducting a Research Through Design project (Gaver et al., 1999). Cultural probes are presented as a series of interactive tools which participants are provided with, to interact with them in their natural settings throughout a certain period. What distinguishes this method are the qualitative data that are possible to gather that, as claimed by the researchers, are used to arouse information that can offer insight into people’s daily choices, reflections, and desires (Gaver et al., 1999). Accordingly, Wallace et al. (2013) claim that probes are considered tools both for designing and understanding (Wallace et al., 2013). In essence, designing probes consist of creating objects whose materiality and form are designed to relate to a particular question and context and to pose questions “through gentle, subtle, provocative, creative means” (p.3441). Therefore offering a participant intriguing ways to consider a question or task and formulate an answer through the act of completing the probe in a creative way (Wallace et al., 2013).

4.7 Affinity Mapping

In line with what Martin and Hanington (2012) stated in their research, the affinity diagram is used to analyse and map out both considerations and intuitions of the designer as a final process of the research method. The data gathered from fieldwork’s research methods are clustered based on their analogous themes to accurately consider and visually represent all the results before proceding with the definition of the concepts (Martin & Hanington, 2012).

4.8 Sketching and material exploration

In line with Buxton (2007), sketching is essential for design thinking and concept development, it is through it that the designer can explore different ideas rather than convey defined and fixed concepts, being able to explore them and draw considerations and evaluating the design opportunities (Buxton, 2007).

The material exploration method aims to identify perceived material qualities by utilizing electronics as materials (Bdeir, 2009) and further to experience the affordances of the physical materials per se. According to Bdeir (2009), thinking of electronics as material help the designer to focus on how the sensors work and how this informs the designer for insights but also obstacles implications, priming them with several design iterations. These methodologies were chosen as they are a quick way to explore ideas and identify the pros and cons and implications in concepts.

4.9 Prototyping

Identified with one of the main design stages, prototyping is a method employed for the investigation of the design of interactive artefacts, to represent the various states of an evolving design and to explore its options (Houde & Hill, 1997).

In accordance with what Houde and Hill (1997) claim, the designer should focus on the essential questions about the interactive system being designed: “What role will the artifact play in a user’s life? How should it look and feel? How should it be implemented?” (p.1). Only by focusing on the purpuse of the prototype that the designer takes better decisions regarding the prototype to build. In this way, we might design prototypes with a clear purpose and, therefore, we can better adopt prototypes and better convey about their design (Houde & Hill, 1997).

For Houde & Hill, these important questions are visually translated into important aspects of the design of an interactive artifact, represented by a three-dimensional space (Figure below).

4.10 Usability testing: experience prototyping and

retrospective think-aloud method

According to Houde & Hill (1997), “once a prototype has been created, there are several distinct audiences that designers discuss prototypes with” (p,2).They are “the intended users of the artifact being designed; their design teams; and the supporting organizations that they work within” (Erickson, 1995; Houde&Hill, p.2). The evaluation of the prototype start from the design team members “by critiquing prototypes of alternate design directions”(p.2). Consequentially, they show prototypes to users to gain feedback on in progress designs. The purpose of showing the prototype to the users is to evaluate the experience of the prototype and by that, being open to progress and possible directions (Houde&Hill, 1997). Indeed, according to Fulton and Buchneau (2000) by handing over a prototype the focus is not necessarily on the devices

and its elements, but on a comprehensive experience in context with them (Fulton

& Buchneau,2000). Together with the Retrospective think-aloud (RTA) method, the usability test gains feedback and responses (Martin & Hanington, 2012). According to Martin & Hanington (2012), the RTA is a research method usually applied in usability tests and it sees the designer observing and analysing participants while compliting a task using the prototype (p.180). After using the prototype, the participants are asked to expand on their experience by reflecting on it, providing the observer with opinions, feelings and spontaneous insights (Martin & Hanington, 2012). This testing section

“What do Prototypes Prototypes” (Houde & Hill in Handbook of HCI, 1997)

5.1 Design Process

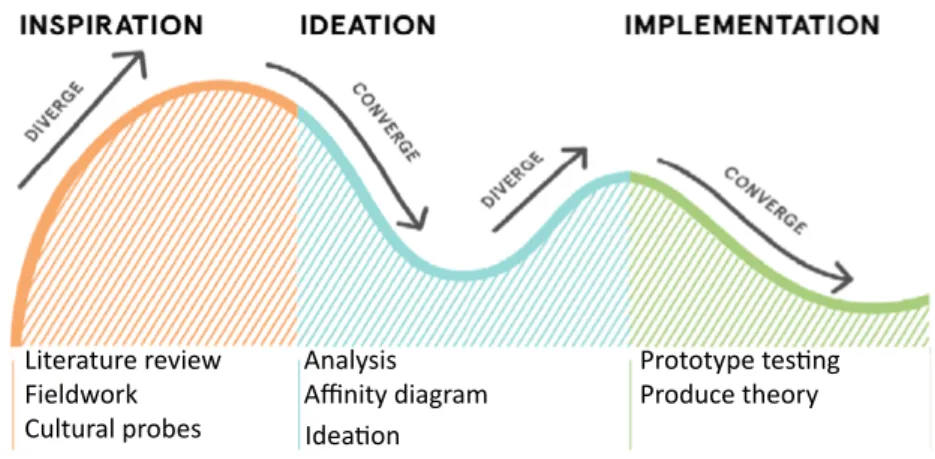

The thesis project here reported followed a four-stage design process which results to be an adaptation of the IDEO’s design process (Ideo, 2015), tailored on this specific project. Throughout the process is it possible to encounter diverge and converge phases which inform the project from the inspiration, ideation and, ultimately, the implementation phases. The first stage is defined as a “divergent stage”, which comprises both the exploration of the research context and data gathering for the foundation of the theoretical background study and fieldwork (as shown in the figure below). In the second stage namely “convergent stage” analysis and synthesis of the data gathered from the first stage are carried out. The third stage is a “divergent stage” where ideas and concepts are developed throughout the analysis until user-test. Finally. The last stage, a “convergent stage”, employs testing and analysis of the design outcomes in order to produce knowledge in line with the research questions.

5.2 State of the field research

As a preliminary investigation a literature review was to explore relevant theories and to define the theoretical foundation of this project. In the first stages of the project the inspiration phase and the brief were still open, therefore a background investigation of previous studies was used to increase the knowledge in the thematic and outline the first research qustion. This method also included the exploration of the design area in which the project aims to contribute. Therefore, it comprises the analysis of canonical examples as pertinent projects in the area of interest. Several search portals and databases were retrieved in this literature review that comprises ResearchGate, MAU Library, ACM Digital Library MitPress.edu, and Malmö University Electronic Publishing. Useful data were gathered from the websites, social media and journals namely The New Yorker, The Guardian, Vimeo, YouTube channels (Vice, Interaction

5. Design Process & Methods

Figure 7. Project process inspired by Ideo process, 2010

Literature review Fieldwork Cultural probes

Analysis

Affinity diagram Prototype testingProduce theory Ideation