Anti-bullying interventions for

Children with special needs

A 2003-2020 Systematic Literature Review

Wenwuyu Gao

One year master thesis 15 credits Supervisor Lily Augustine

Interventions in Childhood

Examinator

1 SCHOOL OF EDUCATION

AND COMMUNICATION (HLK) Jönköping University

Master Thesis 15 credits Interventions in Childhood Spring Semester 2020

ABSTRACT

Author: Wenwuyu Gao

Anti-bullying interventions for chidlren with special needs A 2003-2020 Systematic Literature Review

Pages: 27

Children with special needs are often considered as a vulnerable group, who faces double risk than general peer groups to be bullied. Bullying interventions are a useful method that can be used to help children enhance their self-esteem and coping skills. The aim of this systematic review is to explore anti-bullying interventions programs for children with special needs, and intervention outcomes. A search for scholarly articles has been carried out in four databases,739 articles were identified and six articles included in the analysis after applying inclusion and exclusion criteria. The anti-bullying interventions were beneficial for children with special needs to reduce risk of bullying , while the results were varied. This study combined Bronfenbrenner's ecological model with various anti-bullying intervention designs to discuss the results. This study make up a lttle gap in the area of anti-bullying intervention for children with special needs, and provide an overview of these program. Limitations of the study and further research will be discussed.

有特殊需要的儿童通常被视为弱势群体,并且面临着两倍于同龄人的被霸凌风险。欺凌 干预作为一种有效手段,可以用来帮助儿童增强自尊和应对能力。本系统综述的目的是 探讨针对有特殊需要的儿童的反欺凌干预方案和干预效果。在四个数据库中搜索了学术 文章,得到738 个结果,并最终得到满足条件的六篇文章。反欺凌干预措施对于有特殊 需要的儿童有利于减少欺凌的风险,但干预结果却各不相同。这项研究结合了 Bronfenbrenner 的生态模型与各种反欺凌干预设计来讨论干预结果,弥补了对有特殊需 要的儿童的反欺凌干预方面的一点空白,并提供了这些计划的概述。研究的局限性和进 一步的研究将讨论。

Keywords: Bullying, bullying intervention, children with special needs, Bronfenbrenner, ecological model

Postal address Högskolan för lärande och kommunikation (HLK) Box 1026 551 11 JÖNKÖPING Street address Gjuterigatan 5 Telephone 036–101000 Fax 036162585

2

Table of Content

1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 BACKGROUND 2 3 AIM 6 4 METHOD 7 5 RESULTS 12 6 DISCUSSION 21 7 CONCLUSION 25 REFERENCE 27 APPENDIX 1 31 APPENDIX 2 33 APPENDIX 3 341

1 Introduction

Bullying, is a serious issue which raised awareness in worldwide in recent years. Bullying behavior recently to be observed more often at school and and resulted in negative effects to all involved individuals (Peña-López, 2017). For short term, bullying will negatively affect on victims’ physical, mental, and academic well being. For long term, bullying victims will face high levels of anxiety, low self-esteem, and increase the frequency of thinking about suicide (Kowalski, Limber, & Agatson, 2008; Olweus, 1993).

One group at risk for being bullied are children with special needs. According to Lygnegård et al. (2013), the concept of a child in need of special support is any individual under 18-year -old with or without diagnosed disability, health conditions, requiring specific services or other forms of additional support. Children with special needs, especially children with disabilities were twice as likely to be identified as both perpetrators and victims in bully than students without disabilities, ( Rose, Espelage, & Monda-Amaya, 2009). In most general contexts, children with disabilities are suggested with higher risk to be bullied or treated unfairly than other students, because they look “weak” or less powerful (Turner et al., 2011; Kendall-Tackett et al., 2005; Sampson, 2016). Also, disabilities and special needs of the children result in their limitation of gaining social skills, which is another important reason of being bullied. Besides, due to the limitation of their special needs, it is difficult for children to express their feelings and needs properly.

In 1989, United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child demonstrated that, no children should be treated unfairly on any bias no matter what culture, religion, sex, disabilities or economic statues they live with (UNCRC, 1989). Combining the effect of bullying

victimization, anti-bullying interventions are more essential. Bullying intervention programs can be generally divided into interventions and preventions. Various bullying intervention and prevention programs have been done with children without disabilities or special needs, whereas few have been discussed in special education area. For this reason, this study will focus on previous literature about anti-bullying intervention programs, which implemented on children with special needs as victims. The outcomes of interventions will be analyzed and discussed later in this study.

2

2 Background

2.1 Definition of bullying

Bullying is a preventable serious issue widely discussed in the world. It affects children’s mental health and physical well being. Before exploring the effectiveness of bullying interventions, it is essential to define bullying.Bullying can be aggressive behavior in some contexts, bullying means something different from aggressive behavior, not all forms of aggression include bullying, and not all forms of bullying include aggressive acts (Olweus, 1993). According to Smith and Sharp (1994), bullying was identified as “the systematic abuse of power,” with undesirable actions repeated over time. Generally, bully can be divided into two categories, direct bullying and indirect bullying (Houchins, Oakes, and Johnson, 2016). To be more precise, bully includes three subtypes, physical, relational, property damage, and verbal.

Children who involved in bullying progress play different roles. According to Gumpel (2008), involving children can be divided into three types. The first group is pure bullies, who consistently conduct harmful emotional, social or physical actions to peers. The second group is victims, who repeatedly encountered bullying behavior from their peers. The last group is the bully-victims who both bullies others and are bullied. Most of children involving bullying are the third type, whether they are intended or not. This type of children shows higher risk for having psychological problems than other two groups (Yen, Ko, Liu, & Hu, 2015).

There are both short term, direct effects of bullying and more long term effects. Bullying can affect victims’ physical, mental, and academic well being, resulting in high levels of anxiety, low self-esteem, and increase the frequency of thinking about suicide (Kowalski, Limber, & Agatson, 2008; Olweus, 1993). Apart from this, victims who suffered long-term bullying have higher risk at depression, low self-esteem, and school failure (National Alliance on Mental Health, 2007).

2.2 Bullying and Children with special needs

The concept of children with special needs is defined as an individual under 18 years old with or without diagnosed disability, health conditions, requiring specific services or other forms of additional support (Lygnegårdet al., 2013). For example, children with sensory, motor or neurological defects belong to this group (OECD, 2007).

3 In recent years, bullying has been reported frequently in schools and resulted in severe outcomes (Peña-López, 2017). A regional study of middle and high school youth (n = 21,646) shows that, students with disabilities were twice as likely to be identified as perpetrators and victims in bully than students without disabilities (Rose, Espelage, & Monda-Amaya, 2009). Regarding researches from Blake et al. (2012), Nansel et al. (2001) and Vessey et al. (2014), around 30 percent of all students were involved in bully process (i.e. perpetrator, victim and bystander). And some researches suggested that children, who look “weaker” or smaller, especially with disability, are more likely to be abused or neglected than their peers without disabilities (Turner et al., 2011; Kendall-Tackett et al., 2005; Sampson, 2016). This makes bullying victimization of children with special needs more vital.

2.3 Bullying intervention and bullying prevention

In a previous review of literature, intervention is a collective terminology including actions, methods, treatment and therapy. Interventions are often characterised by a conscious action which aims to achieve a specific goal for a person, family, school or community. Interventions can be summarized and implemented in school or education context. Developing an intervention process is divided into six sections, defining problems and goals, understanding its causes, clarifying contextual factors, identifying how to make a change, testing and refining in a smaller scale and evaluating (Wright et al., 2015).

Prevention as a common method of intervention programs, are often related to intervention. Prevention means the act to stop something before its happening, or stope somebody from doing something. In this study, prevention means that the program focuses on stop peers from bullying others, and prevent children be bullied. The Olweus Bullying Prevention Program(OBPP) is one of the most researched bullying prevention programs, which aims to reduce existing bullying, stop new bullying happens, and achieve better peer relationships in school context (Olweus, 1993; Olweus & Limber, 2010). Based on this program, prevention is not only focus on existing bullying, but also aims to prevention new bullying behavior. In this context, children with and without bullying experience can all participate in this kind of programmes.

Therefore, prevention as a solution is a part of intervention programmes. When discussing bullying intervention, it is essential to distinguish its intervention goals and target groups. In

4 this study, the term intervention will be divided into two categerories, after bullying intervention and the others. As one of the study purposes is to find bullying interventions programmes for children with bully experiences, the term anti-bullying intervention will be mentioned in following context means after bullying interventions.

2.4 Bullying intervention and Bronfenbrenner’s model

As mentioned by Bronfenbrenner (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), children’s developments are influenced by both the environment and biology factors. Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model with five various systems is an effective tool to identify facilitators and barriers of participants. Microsystem includes personal biological makeup and the immediate surroundings of an individual, and Mesosystem composed of relations between one’s immediate environments. Exosystem is made up of external environmental settings which affect development indirectly. Macrosystem consists of the larger cultural context, and Chronosystem is related to time dimension and changing over time (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). First three systems are obviously recognized in interventions. In this systematic review, anti-bullying interventions will be discussed combining with Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model.

Children with special needs are often considered as a vulnerable group. As mentioned by OECD (2007), some of children in needs of special help have various difficulties, such as physical problem (sensory, motor defects), learning development disorder and social barriers. Bronfenbrenner’s model has five systems and subordinate elements. In intervention planning process, this model is helpful to use to identify children's problems. For example, children with intellectual development disorder (IDD) often have difficulties in Microsystem, which is reported as limited language and social abilities. In Mesosysterm, children with IDD show less positive peer relationships compared to others.

After understanding problems and causes, clarifying factors influence the intervention target is necessary (Wright et al., 2015). During the research, most of children with special needs are at school age, so that many school based anti-bullying interventions were conducted. According to the findings of the Ttofi and Farrington (2011) meta-analysis and other intervention studies from the field of prevention science (O’Connell, Boat, & Warner, 2009; Spoth et al., 2013), there are some implementable bullying prevention in schools. Most common anti-bullying

5 interventions were based on preventions by setting themed classes and stimulated video training, which aims to help children gain assertive skills to react in bullying situation. Some other interventions were based on increasing children’s interactions with peer groups, or involving more facilitators in children’s environment context. According to Bronfebrenner’s ecological model, schools, classes and peers are key elements in Microsysterm that can influence the intervention goals. Many programmes based on these factors to setting intervention steps. Ttofi and Farrington (2011) and other researchers(O’Connell, Boat, & Warner, 2009; Spoth et al., 2013), summarized results of the described programmes from participants’ personal assertie skills, peer relations and other performance in schools, wihch covered both Microsystem and Mesosystem.

During researching process, less literature about anti-bullying interventions for children with special needs were found. Some interventions involved children with special needs, however not many specific solutions were designed for them. The details will be presented later in following parts.

2.5 Gap of knowledge in bullying intervention for children with special needs

When the research direction was decided, the author did some literature research on databases. In previous literature, most existing articles relevant to bully and children witih special needs are focused on the correlations between bullying and the negative effects bring to these children. Few of researchers implemented bully intervention programs on children witih special needs. Although there is a systematic review studies (Houchins, D. E., Oakes, W. P., & Johnson, Z. G., 2016) that integrated some bully intervention programs for students with disabilities (SWD), and examined the effectiveness of several intervention programs specific for SWD by using Council for Exceptional Children (CEC) standards, some limitations still existed. First of all, this review used only one well-established database to conduct the initial search, which limited the searching area of the review. Second, most intervention programs include only interventions focused on bullying prevention. Furthemore, bullying interventions could be interdisciplinary studies (Rahill & Teglasi, 2003), more relevant fields can be taken into consideration, such as cooperation between psychologists and schools.

Besides, many of these interventions were preventions. As aforementioned, prevention as a solution belongs to interventions. In this research area, examing the results of prevention

6 programs for children with special needs is relatively difficult due to ethical problems. For example, it is unethical to exposure children with special needs into the environment of being bullied to exam the effectiveness of the intervention. Although simulate environment and some assessment scales can replace to some extent, more relevant factors such as potential bias need to be considered.

3 Aim

Children with special needs have an heightened risk of being bullied, therefore effective interventions supporting children with disabilities who been bullied is vital to identify. Yet few seem to have been implemented.

Most of literature only focused on the correlations between bully and children with disabilities, such as facilitators and barriers in bullying context. But few of the existing literature explored bully intervention for children with special needs and their outcomes. Most of researches briefly mentioned some intervention approaches in discussion or conclusion part, whereas not implemented in practice. Although there was an aforementioned systematic review related to this study topic, the authors include both prevention and intervention programs together. Hence, the studies about after bullying intervention for students with disabilities are important to be discussed.

This study was guided by these two research questions:

1. What kind of bullying interventions are found in previous studies for children with

special needs who experienced bullying?

2. Does these after bullying interventions for children with special needs have positive

7

4 Method

A systematic review was conducted. A systematic review design consists of 6 steps. Define the research question, Design the plan, Search for literature, Apply inclusion and exclusion criteria, Apply quality assessment and Synthesis (Jesson, Matheson, & Lacey, 2011). This study used PICO (Table 1).

4.1 Procedure

Data were collected by four databases, Eric, CINHAL, PscyINFO and PubMed. The databases were searched to identify any study in each database published between 2003 to 2020, reporting the outcomes of bullying interventions to children with special needs that been bullied. Considering the procedure of conducting intervention programs take time, studies before 2003 were excluded.

Search Threads: (children or adolescents or youth or child or teen* or student) AND

(interven* or therapy or treatment or strategy) AND ((bully* or (peer victim*) or cyberbullying or harassment or teasing)) AND (disability or disabilities or disabled or impairment or impaired or special or special needs or special support).

The search string applied in Eric on 1st February 2020, and the same words were used to search on other databases.

4.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were used for identifying selected articles, and to exclude inappropriate articles. The extraction table of inclusion and exclusion criteria is shown below.

4.3 Studies selection

Articles were selected from 4 databases (Eric, CINHAL, PscyINFO and PubMed). In order to narrow done studies and collect specific articles regarding research questions, the limitations of age group and language were applied.

4.3.1 Title and abstract screening

By using keywords searching on aforementioned database, 739 articles were found, including 96 duplicates. Most articles were excluded due to different age groups, such as children younger than 5 years old or young adults, not peer reviewed and different research methods.

8 Therefore, only 27 of articles were included in full text screening procedure.The inclusion and exclusion criteria were then applied to these 27 articles. After full screen testing a total of 6 articles remained to be extracted. The detail of selection process is pictured in the following Figure 1.

Inclusion Exclusion

Population 1) Children in need of special supports that were bullied

2) Age range 5 – 18

1) Participants in other age groups 2) Children as bullies

3) Children without special needs

Intervention 1) Bully intervention programs 1) Bullying prevention programs

Comparison 1) Children’s performance from the same group before intervention

2) A control group of children without intervention

Outcomes 1) Children’s performance measured by scales

1) Studies without outcomes of intervention

Others 1) Peer reviewed. 2) Published in English. 3) Published since 2003

4) Longitudinal studies or follow-up studies with at least two waves.

1) Books, reports and systematic review.

2) Qualitative studies 3) Retrospective studies 4) Full text unavailable

9

Eric

PsycINFO

PubMed

CINAHL

177

262

162

138

739

Duplication 96

Abstract and Title Screening

643

Full text screening 27

Excluded

1. Other age group

2. Children without special

needs

3. Children without bullying

experience

4. No outcomes mentioned

5. Other research methods

10

4.4 Data extraction

After selection, a protocol was used to extract data. It includes general information of the articles (authors, published year, the title, and name of the journals), study purpose, research design, participant groups, results of articles, authors’ opinions in discussion and limitations of the studies. (see Appendix A)

4.5 Quality assessment

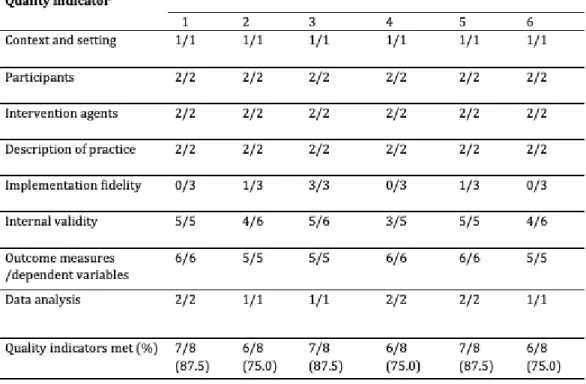

One research questions focus on positive outcomes of the interventions for bullied children with disabilities. Indicators developed by Council for Exceptional Children (CEC, 2014) will be used to assess the intervention programs (Appendix A). CEC standards were based on previous studies by Gersten et al. (2005) and Horner et al. (2005), but included more specific elements of indicators, and tested by Cook et al. (2015) prior to publication (Houchins et al., 2016).

As presented in Table 2, the first four indicators are about critical features of intervention, participant demographics and their status of special needs, the role of intervetion agents and their qualifications, and the record of implementation process. Implementation fidelity means whether the study assess and report the study by using direct and reliable measurements (i.e. observation and self-report scales). Internal validity represents that researchers provided sufficient information to prove that the outcomes are directed by interventions. Outcomes measures is related to what outcomes were found and what assessments were used to meaure. And the last one Data analysis reports the effect size of outcomes and the relations to intervention (CEC, 2014).

11 Table 2 Quality assessment

Selected studies will be presented by using a table. General information of articles will be analyzed first to give an overview of each study. In order to answer the first research question, the intervention programs will be described and synthesized in a table with four main categories, a) what is the

intervention, b) who was involved, c) where was it conducted, and d) how often does the intervention, e) what outcomes were measured, f) how outcomes were measured.

12

5 Results

From a total of six articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Five of the six papers implemented interventions and looked at positive outcomes for children with disabilities. Over 50% of participants achieved intervention goals and showed better performnce compared with their behavior before interventions. The sixth article was a single case design and outcomes where reported differently. Most selected empirical articles implemented interventions and collect data to analyze the effectiveness. One of the selected articles did not present a very clear statement that the statistics was collected from single case. Brief information of selected articles will present in the table below (Table 3).

5.1 Intervention programs

In order to answer what kind of bullying interventions are found in previous literature, the different interventions programmes need to be described. All interventions have been synthesized into a table with four main categories, features of the interventions, involved participants, conducting process, and outcomes measures and improvements .

First three selected articles are aimed to intervene students with Autism based on various programs. Study 1 developed a peer-mentoring program, which includes one student with autism with four peer students. An introduction meeting was provided before 12 sessions in 7 months. The content of the sessions included common issues, like work skills, friendship, bullying, interests and behavior. Students self-esteem, social satisfaction and peer victimization was measured as outcomes (see Table 3).

Study two was a single subject design using video modeling intervention. The procedures are presented in Figure 1.

13 Participated children took Skills Acquisition Assessment Session (SAAS) and In Situ Probes both before and after the video modeling intervention to make comparisons. Children needed to repeating watch three videotaped scenarios in video modeling session until they reached learning criterion of 3 out of 4 correct responses in video modeling and SAAS sessions. The correct response is coded as an appropriate assertive response in 10 seconds. However, due to the baseline of each child is different, the length of sessions would be vary.

The third study is similar as the first one while it was a single subject design. The core of this intervention is building children’s confidence and sense of inclusion by increasing peer interactions between general student groups and the participant. The baseline consists of 6-11 observations on each participant with ASD during the lunchtime. Each observation lasts 25-30 min without any instructions. Before conducted intervention, an introduction meeting was given to explain the program and make schedules. This peer network meetings were held twice a week during lunch in an empty classroom or conference room for approximately 4 weeks. Electronic materials and snacks were including during all the meetings aiming to provide a comfortable environment and common topics for participants.

The fourth intervention is an Internet based intervention to students with wild range of disabilities. One nurse supported each group discussion with a webisode every 2 weeks, for a total of 24 weeks. Five instruments were used in this intervention, Student Information Form, Disability Form, Child-Adolescent Teasing Scale (CATS), Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC), and Piers-Harris Children’s Self-concept Scale (PHCSCS). Four different

components of teasing: personality and behavior, school-related teasing, environment factors and body characteristics were measured by the first scale CATS (Vessey, Horowitz, Carlson, & Duffy, 2008 ). PSC is designed to include parents’ reports. And the last one, PHCSCS (Piers, 1984), is a questionnarie which includes 80 different items for participants to check and report themselves. Pre- and post results were compared to see whether students demonstrated better self-concepts and greater resilience in reporting bullying or not. ,

Bullying/ victimization intervention program (BVIP) was implemented in fifth study to students with wide range of disabilities. BVIP is a school based intervention, which divided into seven sessions: Group rules and Mutual interest inventory, Empathy, Problem-solving model: Media, Problem-solving model and coping, School maps: Identifying social-culture

14 resources, Body maps: positive esteem and empowerment and Review, skill application and wrap up. 13 children whose victimization screening scores over 24 were involved in this program and divided into three types of intervention groups: individual only (n=2), group only (n=6) and individual + group (n=5). Four instruments were implemented to measure

participants’ outcomes: Content Test, Bullying Victim Self-Efficacy Scale, Coping With Bullying Scale for Children and Behavior Assessment System for Children-Second Edition: Self-report of Personality (BASC-2 SRP). The first test with 24 components is aiming to measure students’ knowledge of bullying, while the second one with 17 items is used to assess student’s efficacy to address bullying victimization issue. Coping With Bullying Scale for Children is a instrument with 6 subscales to exam participants coping skills of bullying and collecting their opinions of these skills. The last one BASC-2 SRP is related to personal’s risk level within five components: inattention, internalizing problems, individual adjustment, school problems and emotional symptom index. Besides, Reliable Change Index (RCI) also used to calculate whether children’s change in social-emotional functioning is clinically significant or not.

Study six described a school based group intervention called GBAT-bullying (Group

Behavioral Activation Therapy program, Chu, Colognori, Weissman, & Bannon, 2009) with four modules, which aims to teach children protective strategies to reduce both the risk and frequency of been bullied. After the introduction meeting, participants took 14 weekly meetings following the intervention process. The intervention incudes 14 hour- long sessions and starts with introduce the facts about school life and bullying. Then students were explained how to build one’s social network, stand up for oneself and mobilize one’s forces and resources. Two individual sessions were also scheduled to collect feedback privately. The participating group is 5 students age 12 to 13 who experienced bullying. Four of five of them were diagnosed Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) comorbid with other disorders, whereas one child diagnosed ADHD. Various measurements were applied in this study to collect pre- and post treatment data and examine the results. The study mainly measured participants from three aspects, symptom severity and functional impairment, bullying impairments and anxiety/ depression degree. Multidimensional measurements were applied to collect data, including pre-treatment and post treatment scores.

15 NR Reference Sample age Disability Nr of

waves

Type of Outcome

Improvement Measurement Country

#1 Brandley, R. (2016)

12 Grade 7 Autism 2 Self-esteem Social satisfication Bully reduction Increase self-esteem, social satisfaction,reducing bullying

1. Harter Self-Esteem Qustionnaire. 2. Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction. 3. Bullying (Anti-Bullying Alliance,2007). 4.Semi-structured Interviews with students

UK

#2 Rex, C., Charlop, M.H. & Spector, V. (2018)

6 8-13 Autism 3 SAAS criterion Situ Probes criterion

Learned to react to bullying and social exclusion

1. Skills Acquisition Assessment Session Video and Question 2. Situ oribe script

USA

#3 Sreckovic, M. A., Hume, K., & Able, H. (2017) 3 15 Autism 2 Confidence Sense of inclusion Increase in peer interactions and reduce rates of bullying victimization

1,Investigator created a checklist with all components from all orientation meetings.. 2.Weekly peer network meeting treatment fidelity checklist for the facilitator. 3.Weekly peer network meeting treatment fidelity checklist for peer partners

USA

#4 Vessey, J. A., & O’Neill, K. M. (2011) 65 8-14 Wild range disabilitie s 2 Resilience Less bullying Improve self-concepts, develop resilience, enable to handle bullying

1. Student Form. 2. Disability Form. 3. Child-Adolescent Teasing Scale (CATS). 4. Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC) 5. Piers-Harris

Children’s Self-concept Scale (PHCSCS)

16 #5 Graybill et al. (2016) 12 Grade 4-8 Wild range disabilitie s 2 Content knowledge, self-efficacy, coping skills, self-reported level of victimization and social/ emotional functioning. Change in content knowledge, increase self-efficacy, increase in coping skills, decrease in self-reported levels of victimization and increase in self reported social/ emotional functioning

1. Content test 2. Bullying victim self-efficacy scale 3. Coping with bullying scale with children 4.Behavior assessment system for children-second hand edition:self-report of personality

USA

#6 Chu et al. (2015) 5 12-13 SAD, MDD, GAD and ADHD 2 Stronge group attenence, Decrease score in ansiety and depression.

Learn coping skills with anger and assertive response to bullying. Improve peers and family relationships.

1. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule. 2. ADIS Clinician Severity Rating. 3. Multidimensional Bullying Impairment Scale. 4. Screen for Childhood Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders–Child/Parent. 5. Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale–Child/Parent. 6. Social anxiety disorder. 7. Generalized anxiety disorder. 8. Separation anxiety disorder. 9. Major depression disorder

USA

17 Study n Nr session Duration People involved Conducted by Type of intervention

#1 14 7 months Students with and without diagnosed autism

School Group intervention

# 2 2 Depends on

baselines

Children with autism and therapists Therapists Video modeling intervention

#3 8 4 weeks Children with and without autism School Peer network intervention

#4 12 24 weeks Children with range of disabilities and nurses

School and nurses Web-based program

#5 13 15 weeks Children with range of disabilities and research assiatants

School Bullying/ Victimization Intervention Program (BVIP)

#6 5 14 weeks Children with mood disorder and a

children with ADHD

Therapist Group behavioral activation therapy-bullying (GBAT-B)

18

5.2 Results and outcomes of intervention programs

All of the selected articles showed positive outcomes of intervention programs in different levels.

Significant achievement gained in the first study. Self-esteem, Social satisfaction and Bullying are three main aspects that measured pre- and post intervention (see Appendix 2). In this peer mentoring program, Bullying showed most significant impact (p<0.01,Cohen’s d =2.25), and following with Academic subscale in Self-esteem (p<0.01, Cohen’s d= 1.21). Another subscale Social in Self-esteem also has great improvement (p<0.01,Cohen’s d=1.15). Besides, the achievements in other subscales in Self-esteem (see Appendix 2) and Social satisfaction (p< 0.01, Cohen’s d= 1.08) were also improved.

Considering the second study is a single design study and participant children have different baselines, the outcomes will present separately in Table 5.

Table 5

In this video modeling intervention, the main idea was repeating the procedures until they met the criterion, which made this study has less implementation fidelity. Although the results suggested that, 50% of children (three of six) displayed appropriate response in situ process, which showed positive outcomes of this intervention. There were still three children with difficulties to reach the intervention goal that learning to assertively respond bullying and social exclusion. When children with longer baseline offered an additional in situ probe, 66.7%

Participant Baseline VM SAAS Situ1 Situ2

Abby 4 6 2 4/4 Justin 6 4 2 1/4 Jack 7 12 7 4/4 Nick 9 5 5 2/4 Jill 10 4 3/4 4/4 Alex 12 4 2 0/4 4/4

19 of children (four of six) achieved intervention goal in total. Further investigation should be done to see the rationale of the issue, as well as more sample should be included to examine the effectiveness by implementing this intervention.

Similar to the second intervention program, the third study with web-based intervention has few samples. Three participants showed positive achievements in increasing total social interactions. From the side of students with ASD to peers, Participant 1 showed 19.2% of mean change from baseline (0.8%) in initiations and 56.6% of mean change from the baseline (19%) in responses to peers. The numbers of Participant 2 in same context are 16.0% mean change from 19.0% and 25.0% mean change from 45.8%. Participant 3 has less increase in initiations than Participant 2 that the mean change is 13.4% from 6.6% while in responses to peers was 56.6% of mean change from the baseline (19%). From peers to students with ASD, the results presented that Participants 3 has highest mean change as 37.3% from 7.7% in initiations and 55.7% from 26.8% in response, following with Participant 1, 37.1% from 2.9% and 60% 0.8%. Participant also had significant achievement on 31.0% of change from 12.3% in initiation and 33.0% of changes in response from baseline as 42.8%. Besides, participants also reported with reduction of bullying victimized experience, according pre and post scores of Bullying Victimization Scale (BVS), which presented in Appendix 3.

The fourth articles mainly used three scales to measure children’s performance both pre and post intervention to make a comparison. Positive outcomes can be seen according to scores of CATS (t=3.342, p=0.001, Cohen’s d=0.34) and PHCSCS (t=2.546, p=0.007, Cohen’s d=- 0.25). This suggested that participants experienced less bothering situation after they finishing the interventions. However, there were non-significant findings noted for PSC (t=0.220, p=0.83, Cohen’s d=0.02). Apart from measurements, involved nurses who led this program reported that more friendships were observed increasing during intervention process while there was no specific webisode exactly referring to building friendship.

Fifth research questions were set to examine the outcomes of Bullying Victimization intervention Program. In general, students with disability who involved in this study increased their knowledge of bullying related contents (Emily C. et al., 2016). Regarding to pre and post results and paired t-test, participate children showed significant change in content knowledge (t= -3.01, p<0.05), coping skills (t= -2.82, p<0.05) and statistically increased self-efficacy (t=

20 -2.82, p<0.05). Apart from this, reduction of self-reported level of victimization (t= 4.9, p<0.01) and self- reported social/emotional functioning level was achieved. For self- reported social/emotional functioning level, 46% of students (n=6) participated in BVIP showed a clinically significant increase.

In sixth study, Group Behavioral Activation Therapy-Bullying was reported feasible to implement in school context (at least one school) with satisfaction from participants. Attendance in this intervention was strong, except four of five students were missing one group session. Three of the participants were reported decreasing scores on the self-reported Multidimensional Bullying Impairments Scale, one remained stable and one showed increasing. Four participants with diagnosed mood disorder were reported clinically significant changes in Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale-Children, and demonstrated changes in Screen for Childhood Anxiety Related Emotional Disorder. However, the scores of one member with ADHD remain stable without any changes in these two scales.

21

6 Discussion

In this systematic review, CEC standard (2014) was applied as the main measurements to examine the outcomes of bullying intervention studies for children with special needs. Six empirical intervention studies were involved in this process. Although previous literature examined the bullying prevention and interventions for general children and students with disability, this study focus on only intervention studies of bullying victimization of children with special education needs. According to Evans et al. (2014), effective interventions should be culturally relevant and focus in specific student populations to address their specific needs. Combining the understanding of CEC (2014) standard, these quality indicators were used in this systematic review to examine methodological rigor and present the content of analysis structure to compare and contrast specific study components. The following discussion will start from method rigor of these studies, and discuss in detail on contextual environments, and outcome measurements, including limitations.

6.1 Method rigor

When examining the method rigor, there are different adherence levels. None of the articles met all eight criteria. Three studies (Brandley, 2016; Sreckovic & Able, 2017; Graybill et al., 2016) met seven of eight criteria, and other three studies (Rex, Charlop, & Spector, 2018; Vessey & O’Neill, 2011; Chu et al., 2015) met six of eight criteria. Only one article (Sreckovic & Able, 2017) reported implementation fidelity and met three sub standards. This means that although other five studies described the measurements they uesed during interventions, more information should be provide to provde the reliabity of the study. And two of articles (Brandley, 2016; Graybill et al., 2016) met all criteria of the internal validity, which means that variables in other interventions were not clearly controlled, or description of the process were not sufficient. To be more specific, three single case studies (Rex, Charlop, & Spector, 2018; Sreckovic & Able, 2017; Chu et al., 2015) did not show the controls for common threats to internal validity. These findings demonstrated that bullying intervention studies in special education area should pay more attention on controlling the common threats to internal validity and using direct and reliable measurements to assess the implementation fidelity. However, all of these six studies met the criteria of context settings, participants, intervention agents, description of practice, outcome measures, and data analysis. All of six studies reported the information of specific populations and contextual and environmental factors that facilitate

22 participants. Also, all authors conducted and reported appropriate data analysis procedures according to their different study designs.

6.2 Context and settings

All of the studies met the standards for context and setting, whereas the intervention locations were varied. Except one studies (Brandley, 2016) was conducted in the Unite Kingdom, the rest five articles were conducted in the United Stated. Of the studies conducted in the United States, two studies (Rex, Charlop, & Spector, 2018; Chu et al., 2015) were done with therapists’ supervision in clinical context for students with Autism and mood disorder Another four intervention programs recruit most of participants in mainstream schools and conducted interventions in schools, while one study (Graybill et al., 2016) did not describe whether involved schools are mainstream schools or special schools. Furthermore, this study did not discuss whether different school settings may affect the final results.

Bronfenbrenner (1979) proposed an ecological model with varied systems of the environment and the interrelationships among the systems shape a child’s development. The model is general divided into five different levels, Microsystem, Mesosystem, Exosystem, Macrosystem and Chronosystem. Microsystem includes the immediate surroundings of an individual, such as family, peer group, neighbourhood and also one’s personal biological makeup. Mesosystem consists of connections between one’s immediate environments (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). Both these two systems can impact children directly.

Combining with Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), it is obviously to see children are not isolated in development process. Four of selected articles include group intervention therapy, one study (Vessey & O’Neill, 2011) used webisode as media in group intervention program, and one signle case study (Rex, Charlop, & Spector, 2018) used video modeling training intervention. Three key elements in these interventions are peers, therapists or researchers, and media (webisode, videos), which belong to Microsystem level according to the model. In this level, elements can affect individual’s development directly For example, two peer mentoring programs (Brandley, 2016; Sreckovic & Able, 2017) were based on increasing interactions between participants and general peer groups to help students with Autism gain self-esteem, social satisfaction, and reduce bullying victimization.

23 As mentioned in Bronfenbrenner's model (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), building friendships is one of the facilitators to increase children’s self-esteem and sense of inclusion, which is a potential theme across the entire intervention. Besides, as an important element in Microsystem, media can become a facilitator or barrier that affects the development of children, depending on the information it conveys. Two studies use video and webisode as media (Rex, Charlop, & Spector, 2018; Vessey & O’Neill, 2011) to teach participants coping skills to handle bullying victimization. This is beneficial to increasing participants self-esteem and reduce new bullying.

Mesosystem in Bronfenbrenner’s model is consists of connections between elements in Microsysterm. For example, one thing happens in child’s immediate family may affect his or her academic performance in school. One study (Vessey & O’Neill, 2011) collected parents perception on children, and another study conducted GBAT-bullying program (Chu et al., 2015) assess parents percpetion on participants both pre-treatment and posttreatment. This matched factors in Mesosystem. Involving this connection in to intervention process is not only helpful to provide sufficient information to design plan, but also beneficial for future studies.

In Exosystem level, one study (Sreckovic & Able, 2017) reported that two participants was taking both extra assistance from support personnel. Factors in Exosysterm only affect individuals in indirect way. Social support as one of factors in this level is still important to children’s development. However, none of selected articles discussed that whether social support backgound of individuals will affect final results.

Macrosystem is composed of larger cultural context. Chu et al.(2015) mentioned that participants were recruit from ethnically diverse, public middle schools, but no more details described. Chronosysterm is related to time changing. More future studies are needed.

6.3 Outcome measurements

Participants in selected articles were varied in the population demographics. Some researchers focused on one specific student group with extra needs, while some focused on students with wide disabilities or impairments. Three of articles (Brandley, 2016; Rex, Charlop, & Spector, 2018; Sreckovic & Able, 2017) involved in students with Autism, two involved students with wild range of disabilities (Vessey & O’Neill, 2011; Graybill et al., 2016) and one included

24 students group of mood disorder except one with ADHD (Chu et al., 2015). However, one study of students with mood disorder and ADHD (Chu et al., 2015) did not clearly claim that involving participants were diagnosed before being bullied or after bully victimization.

Considering different studies targeted different participant groups and intervention aims, there was no common scale or instrument to measure the effectiveness of these bullying intervention programs. All selected articles used different outcome measure assessments. One of the studies (Sreckovic & Able, 2017) used a teacher-report scale (or profession-report scale) and direct observation method to record pre and post intervention performance of students. And all selected studies included both students’ self-reported scales or interviews to measure participants experience pre and post intervention results. Although regarding to CEC standard (2014) and Houchins et al. (2016), an evidence-based intervention requires at least two group studies that methodologically reasonable, four group comparisons without random assignment, or five single-subject design studies with at least 20 participants. Some intervention studies applied in these studies were the first try of implementation. More future research in specific area is required to examine the interventions.

Looking through Table 3 in results section, athough various scales and instruments were applied to assess participants performance, the aspects of outcomes they measured are similar. The most common outcome is learning knowledge coping skills to response bullying victimization. Four studies (Rex, Charlop, & Spector, 2018; Vessey & O’Neill, 2011; Graybill et al., 2016; Chu et al.,2015) measured this aspect, following with the increasing self concept that measured by three studies (Brandley, 2016; Vessey & O’Neill, 2011; Graybill et al., 2016). Three articles focued on reduce new bullying (Brandley, 2016; Graybill et al., 2016; Chu et al.,2015), and two atircles focused on peer interactions or imporving peer relationships (Sreckovic & Able, 2017; Chu et al.,2015).

6.4 Limitations

Apart from aforementioned parts, there are also some flaws in these selected articles. First, it was difficult to examine the effectiveness of bully intervention for children with special needs. None of the articles clearly mentioned the definition of effective before the intervention designs. Although it is difficult to set common measurement of effectiveness of all interventions, the effectiveness of bullying intervention for specific disability or impairment

25 could be explained. Second, culture differences exist in different countries, even different schools. When target groups refer to children with various cultural backgrounds, intervention programs should control the common threats that participants may face. Besides, it is also worthy to pay attention that some participated children may have difficulties about self-reported feelings, which may affect measuring outcomes. In selected literature, all of the studies involving self-reported measurements (i.e. semi-structured interview, self-reported scales), whereas some tests were not enough to prove whether students acquire knowledge. For example, the main idea of the single case study (Rex, Charlop, & Spector, 2018) that conducted video modeling training was asking children to repeat watching videos until they met the criteria of each stage. Even though researchers add a situ probe process and semi-structured interview at the end of the intervention to examine the knowledge that children learned from videotapes, there was still not convincing. This because that after repeatedly watching the video many times, the child may make a subconscious choice.

For ethical consideration of selected literature, one thing interesting to note is the equality in the number of genders. The sixth study (Chu et al., 2015) included five boys with various mood disorders and one girl with ADHD. Although the study claimed that the participants were drawn from large, ethnically diverse, public middle school, the difference of gender may affect study results.

26 This systematic review focuses on interventions for children with special needs who experienced bullying. Children with special needs have a heightened risk of being bullied, therefore effective interventions supporting them is vital to identify. Two research questions were set to explore this topic. First, explore the intervention programs for children with special needs that experienced bullying in previous studies. Second, synthesis and analyze the outcomes of intervention.

To answer the first research questions, six different interventions were found. Five intervention programs conducted within groups, whereas the video modeling intervention conducted separately with each single participant. Two of five group interventions were related to peer mentoring in school setting, and Sreckovic and colleagues (2017) combined it with online meetings. Another intervention based on online webisode involved network into intervention as well. It is interesting to see that, except traditional therapy, Bullying/Victimization Intervention Program and a novel school based Group behavioral activation therapy-bullying, more and more new techonology becomes the media of intervention for children with special needs.

Based on the results, the second research question is answered. All posttreatment outcomes of the studies showed better performance compared to pre-treatment. Most positive outcomes were reported from various aspects: increasing children self-esteem, reducing bullying victimization and acquiring knowledge related to bullying.

Overall, this systematic review make up a little gap in the area of anti-bullying intervention for children with special needs and provide an overview of various intervention program. Besides, this study discuss the intervention plan, combined with Bronfenbrenner's ecological model. Furthermore, this review also discusses the limiation of interventions and proposed new suggestion, for example, the correlation of participants school backgrounds and outcomes.

However, there are still some limitations in this systematic review. First, in this literature review only six studies met the criteria. Prevention programs for children who were bullied and with special education needs were excluded in this study. Although the initial consideration was that prevention programs have more difficulties to examine outcomes, because it was unethical to expose children into bullying situation. Simulation of bullying situation can make

27 up this limitation in a way. So for future researches, bullying prevention programs could be taken into account with more concrete criteria. Second, CEC standard (2014) were selected to apply as a measurement, while some criteria were difficult to meet, i.e. implementation fidelity. This is not only because the study (Vessey & O’Neill, 2011) was conducted and published before new version of CEC publishing, but also because that CEC standard is more strict and specific than other scales. Apart from this, some interventions were the first attempt of the program. Thus, the flaws of design and procedure were understandable, and future researches are necessary to conduct. Some studies (Vessey & O’Neill, 2011; Chu et al., 2015)involved nurses and psychologist into bullying interventions, which indicates the future tendency of using interdisciplinary approaches in bullying intervention researches.

28 Blake, J. J., Lund, E. M., Zhou, Q., Kwok, O., & Benz, M. R. (2012). National prevalence rates of bully victimization among students with disabilities in the United States. School Psychology Quarterly,

27, 210–222. doi:10.1037/ spq0000008

Bosworth, K., Espelage, D. L. and Simon, T. R. 1999. Factors associated with bullying behavior in middle school students. Journal of Early Adolescence, 19: 341–362.

Bradshaw, C. P. (2015). Translating research to practice in bullying prevention. American Psychologist, 70(4), 322-332.

http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.ju.se/10.1037/a0039114

Bradley, R. (2016). ‘Why single me out?’Peer mentoring, autism and inclusion in mainstream secondary schools. British Journal of Special Education, 43(3), 272-288.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The Bioecological Model of Human Development. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (6th ed, pp. 793–828). Hoboken, N.J: John Wiley & Sons

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development. Harvard University Press.

Chu, B. C., Hoffman, L., Johns, A., Reyes-Portillo, J., & Hansford, A. (2015). Transdiagnostic behavior therapy for bullying-related anxiety and depression: Initial development and pilot study. Cognitive

and Behavioral Practice, 22(4), 415-429.

Evans, C. R., Fraser, M. W., & Cotter, K. L. (2014). The effec- tiveness of school-based bullying prevention programs: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19, 532–544. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2014.07.004

Graybill, E. C, Vinoski, E., Black, M., Varjas, K., Hernrich, C. & Meyers, J. (2016) Examining the outcomes of including students with disabilities in a bullying/victimization intervention. School Psychology Forum: Research in practice, 10(1), 4-15.

Gumpel, T. P. (2008). Behavioral disorders in the school participant roles and sub-roles in three types of school violence. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 16, 145– 162.

doi:10.1177/1063426607310846

29 Houchins, D. E., Oakes, W. P., & Johnson, Z. G. (2016). Bullying and Students With Disabilities: A Systematic Literature Review of Intervention Studies. Remedial and Special Education, 37(5), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932516648678

Kumpulainen, K., Rasanen, E. and Henttonen, I. 1999. Children involved in bullying: Psychological Disturbance and the persistence of the involvement. Child Abuse & Neglect, 23: 1253–1262.

Lygnegård, F., Donohue, D., Bornman, J., Granlund, M., & Huus, K. (2013). A systematic review of generic and special needs of children with disabilities living in poverty settings in low-and middle-income countries. Journal of Policy Practice, 12(4), 296-315.

Olweus, D. (1994). Bullying at school. In Aggressive behavior (pp. 97-130). Springer, Boston, MA.

Olweus, D., & Limber, S. P. (1983). Olweus bullying prevention program.

Peña-López, I. (2017). PISA 2015 Results (Volume III). Students' Well-Being, 132—138.

Piers, E. (1984). Piers Harris Children’s Self-concept Scale: Revised manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Rahill, S. A., & Teglasi, H. (2003). Processes and outcomes of story-based and skill-based social competency programs for children with emotional disabilities. Journal of School Psychology, 41, 413–429. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2003.08.001

Rex, C., Charlop, M.H. & Spector, V. Using Video Modeling as an Anti-bullying Intervention for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 48, 2701–2713 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3527-8

Sreckovic, M. A., Hume, K., & Able, H. (2017). Examining the efficacy of peer network interventions on the social interactions of high school students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 47(8), 2556-2574.

Students with Disabilities, Learning Difficulties and Disadvantages Policies, Statistics and Indicators © OECD 2007, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/40299703.pdf

Ttofi, M., & Farrington, D. P. (2011). Effectiveness of school- based programs to reduce bullying: A systematic and meta- analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7, 27–56.

30 UNCRC (1989) The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 2.

https://downloads.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/UNCRC_united_nations_conventio n_on_the_rights_of_the_child.pdf?_ga=2.152075248.859833839.1590098266-1632204310.1585 906985

Van der Wal, M.F., De Wit, C.A.M. and Hirasing, R.A. 2003. Psychosocial health among young victims and offenders of direct and indirect bullying. Pediatrics, 111: 1312–1317.

Vessey, J. A., Horowitz, J. A., Duffy, M., & Carlson, K. L. (2008). Psychometric evaluation of the CATS: Child-Adolescent Teasing Scale. Journal of School Health, 78, 344–350.

Vessey, J. A., & O’Neill, K. M. (2011). Helping students with disabilities better address teasing and bullying situations: A MASNRN study. The Journal of School Nursing, 27(2), 139-148.

Vessey, J., Strout, T. D., DiFazio, R. L., & Walker, A. (2014). Measuring the youth bullying experience: A system- atic review of the psychometric properties of available instruments. Journal of School

Health, 84, 819–843. doi:10.1111/josh.12210

Yen, C., Ko, C., Liu, T., & Hu, H. (2015). Physical child abuse and teacher harassment and their effects on mental health problems amongst adolescent bully-victims in Taiwan. Child Psychiatry &

Human Development, 46, 683–692. doi:10.1007/s10578-014-0510-2

31

Appendix 1

Quality Indicators for Assessing Methodological Rigor

Quality indicator Indicator element Desig

n Context and setting

Participants Intervention agents Description of practice Implementation fidelity Internal validity Outcome measures /dependent variables

8 Describes critical features of the context or setting (school or classroom)

1. Describes participants’ demographic.

2. Describes disability or risk status and method for determining status

1. Describes role of the intervention agent, and background when relevant to review.

2. Describes agents’ training or qualifications.

1. Describes detailed intervention procedures and agents’ actions or cites accessible sources for that information.

2. Describes, when relevant, study materials described or cites accessible source.

1. Assesses and reports implementation fidelity related to adherence with direct, reliable measures.

2. Assesses and reports implementation fidelity related to dosage or exposure with direct, reliable measures.

3. Assesses and reports implementation fidelity (adherence/dosage) throughout intervention and by unit of analysis.

1. Researcher controls and systematically manipulates independent variable.

2. Describes baseline or control conditions.

3. During baseline or control conditions, participants have no/ extremely limited access to intervention.

4. Assignment to groups: (a) random; (b) non-random but matched; (c) non-random but techniques used to detect differences and, if any, controlled for differences; (d) non- random using cutoff point.

5. Provide three demonstrations of experimental effect at 3 time points.

6. Baseline phase has at 3 data points that establish a predictable pattern (except in certain cases).

7. Controls for common threats to internal validity. 8. Attrition is low across groups.

9. Attrition is low between groups 1. Outcomes are socially important.

2. Defines and describes measurement of dependent variables.

1. B 1. B 2. B 1. B 2. B 1. B 2. B 1. B 2. B 3. B 1. B 2. B 3. B 4. G 5. S 6. S 7. S 8. G 9. G 1. B 2. B 3. B 4. B

32 Data analysis

3. Reports effects of intervention on all measures.

4. Appropriate frequency and timing of outcome measures. 5. Provides evidence of adequate internal reliability.

6. Provides evidence of adequate validity.

1. Techniques are appropriate for detecting change in performance. 2. Single subject graph clearly presents outcome data for unit of

analysis to determine effect.

3. Report appropriate effect size statistic(s) or provide data to calculate the effect size.

5. B 6. G

1. G 2. S

33

Appendix 2

Appendix 2

Pre scores Post scores

n Mean SD Mean SD Effect

size (Cohen’s d) Self-estee m 12 Academic 2.21 0.34 2.78 0.57 1.21 Social 2.47 0.45 3.00 0.47 1.15 Athletic 2.27 0.38 2.71 0.41 1.11 Appearanc e 2.44 0.48 3.11 0.73 1.08 Behavior 2.38 0.58 3.05 0.64 1.09 Global 2.49 0.47 3.06 0.53 1.13 Social Satisfaction 12 1.82 0.74 2.77 0.99 1.08 Bullying 12 3.08 1.35 0.41 0.99 2.25

34

Appendix 3

From students with ASD to peers (mean change)

From peers to students with ASD (mean change) Frequen cy of bully victimized Initiatio ns Respons es Initiati ons Respon ses Before baseline/ After maintenance Particip ant 1 19.2% 56.6 % 37.1% 60.0% 12/1 Particip ant 2 16.0% 25.0% 31.0% 33.0% 1/ 0 Particip ant 3 13.4% 44.5% 37.3% 55.7% 35/ 13

35