J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O L JÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITYGrowth-related Barriers and Their Impact on SMEs

A study of construction companies in Moldova

Master thesis within Business Administration

Authors: Vlad Demian

Tatiana Dumbrava

Tutor: Friederike Welter

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Growth related barriers and their impact on SMEs: The case of con-struction companies in Moldova

Authors: Vlad Demian, Tatiana Dumbrava Tutor: Friederike Welter

Date: 2009-06-02

Subject terms: Transition economies, Moldova, Small and medium-sized enter-prises, Barriers to growth, Growth models

Abstract

Introduction: The need to develop entrepreneurship and small and medium-sized

en-terprises (SMEs) constitutes a crucial issue in the transformation from centrally planned into market economy of the transition countries such as Moldova. Often, small busi-nesses exist in a poor business environment and therefore encounter barriers at various structural levels and points in time. These obstacles hamper the growth of the compa-nies resulting in their premature evolutionary slowdown.

Problem: Prior research has accounted for the barriers to SMEs growth in transition

countries. However, little research was done on Moldovan enterprises. What can be ob-served though is that these SMEs tend to seize in growth after a certain period. External, internal, and intrinsic barriers are the main causes of this phenomenon.

Purpose: The purpose for this research has been formed out of the belief that a better

understanding of the growth of small businesses in Moldova will prove to be a valuable contribution to the pool of research in this area. This study does not aim at making gen-eralizations. Instead, it explores the barriers encountered by entrepreneurs in the field of construction and links them to the growth, or lack thereof, of their companies. The re-sults will be applied to a growth model in order to observe its resulting alterations.

Method: Our research has the character of a qualitative study. Data gathering has been

done through the implementation of a questionnaire in 13 construction-based SMEs in Moldova. We then undertook 4 in-depth interviews over the telephone with the owners to gain more insight and generate ideas to be used in this thesis. The questionnaire was distributed by a contact person in Moldova whose major role was to establish trust with the owners and allow us to contact them for in-depth interviews.

Conclusion: The conclusion we reach is that our surveyed Moldovan SMEs do not

dis-play intrinsic barriers which are related to the manager‘s willingness to expand. Howev-er, internal and external growth inhibitors are present. Their effect can be observed in both small and medium-sized enterprises, but their prevalence differs depending on the firm size. The growth model that is put under these conditions suffers alterations in its structure, experiencing delayed growth stages and slower evolution patterns.

Acknowledgement

This thesis is written as our Master‘s Thesis in the Innovation and Business Creation Master Program at Jönköping International Business School. The hard work during the spring term in 2009 has both provided us with a better understanding of how small and medium-sized enterprises in Moldova develop and grow, as well as improved our skills regarding academic writing.

This work has been possible thanks to certain people who have shown personal and pro-fessional interest in our study. We would like to show our deepest gratitude to our thesis supervisor Friederike Welter for her support and committed guidance. We would also like to thank our colleagues who gave us their support during the whole process of writ-ing this thesis. Also, we are grateful to our close ones, families and friends, who have stood by us during this spring term.

Finally, we show our gratitude to all companies that have taken their time to participate in our research, providing us with information that made this thesis possible to com-plete.

……… ………... Vlad Demian Tatiana Dumbrava

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1

1.2 Problem Discussion ... 2

1.3 Research Purpose ... 2

1.4 Definitions: Entrepreneurship and SMEs in transition economies ... 3

1.5 Delimitations ... 3

1.6 Outline of study ... 4

2

Frame of reference ... 5

2.1 Entrepreneurship in a post-Soviet context ... 5

2.2 Role of SMEs to the economic development ... 6

2.3 Barriers to SME growth ... 7

2.3.1 External barriers ... 8

2.3.2 Internal barriers ... 10

2.3.3 Intrinsic factors ... 11

2.4 SMEs in Moldova and their barriers to growth ... 11

2.4.1 Market reforms and the development of private entrepreneurship ... 12

2.4.2 Relevance of SMEs today ... 14

2.4.3 Barriers to SME growth ... 17

2.5 Theory on the developmental stages of a company ... 19

2.5.1 Greiner‘s growth model ... 19

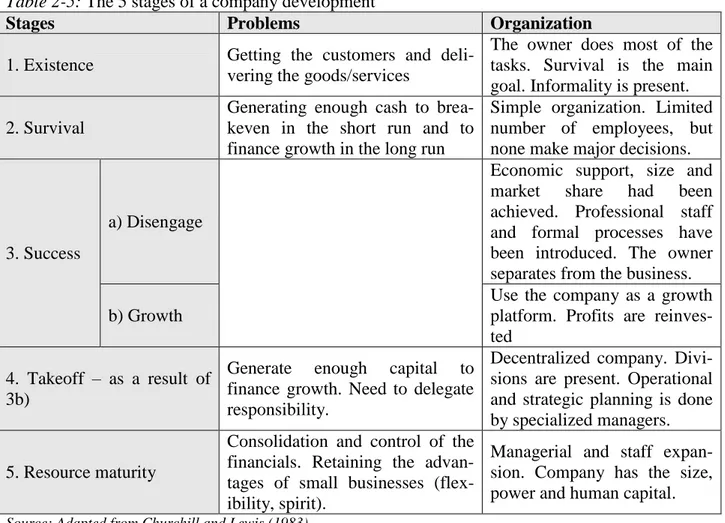

2.5.2 Churchill and Lewis‘ growth model ... 23

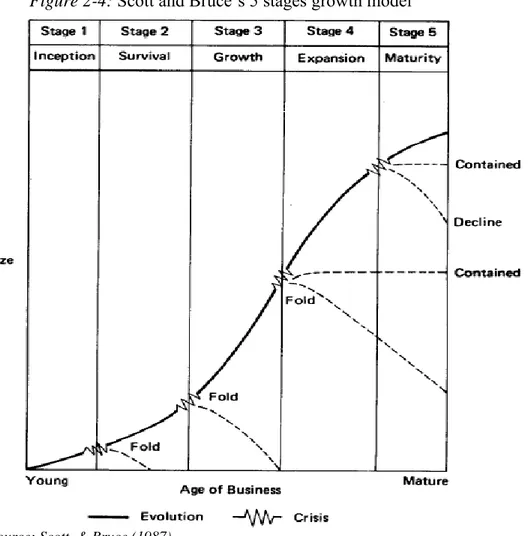

2.5.3 Scott and Bruce‘s growth model ... 25

2.5.4 Hanks, Watson, Jansen and Chandler unified growth model ... 27

3

Methodology ... 29

3.1 Research Design ... 30

3.2 Research Approach ... 30

3.3 Operationalization of research variables ... 31

3.3.1 Questionnaire ... 31

3.3.2 Interview ... 33

3.4 Sample selection ... 35

3.5 Quality standards: reliability and validity ... 36

4

Empirical Data ... 37

4.1 General information about the owners, companies and industry ... 37

4.2 Determining the evolution stage of the surveyed SMEs ... 38

4.3 External & internal factors that affect SME development ... 39

4.4 Intrinsic factors that affect SME development ... 46

5

Analysis ... 48

5.1 Determining each company‘s evolutionary stage ... 48

5.2 Analysis of the intrinsic factors ... 49

5.3 Analysis of the external factors ... 50

5.4 Analysis of the internal factors ... 54

5.5 Summary of the analysis ... 55

6

Conclusion: ... 60

7

Discussion & further research ... 61

References: ... Error! Bookmark not defined.

Appendices ... 67

Percentage of Moldovan firms and CIS countries‘ firms indicating problems in various sectors………. 67

Key problem areas in Moldovan SMEs………..68

Survey……….69

Figures

Figure 2-1: Evolution of SMEs in 2005-2007………... …. 15Figure 2-2: Greiner‘s 5 growth phases……….. …..21

Figure 2-3: Churchill and Lewis growth model……… …..23

Figure 2-4: Scott and Bruce‘s 5 stages growth model……….. …25

Figure 3-1: Determining the variables……….. …..32

Figure 4-1: General information about the owners, companies, and industry.. ….38

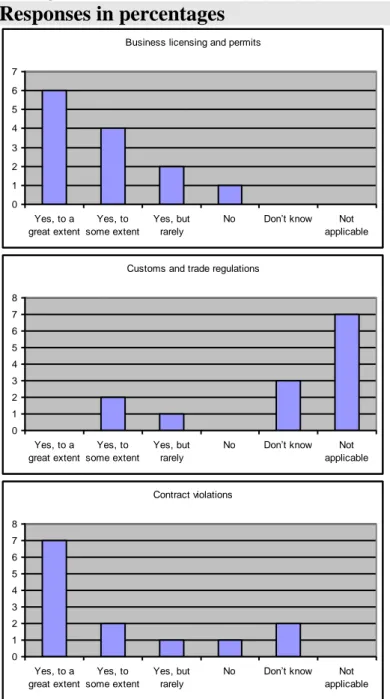

Figure 4-2: External and internal factors that affect SME development (re-sults)……….. …..40

Figure 4-3: Intrinsic factors that affect SME development (results)…………. .…47

Figure 5-1: Major factors affecting Moldovan SMEs………... …..56

Figure 5-2: Adjusted growth model to Moldovan SMEs……….. …..57

Tables

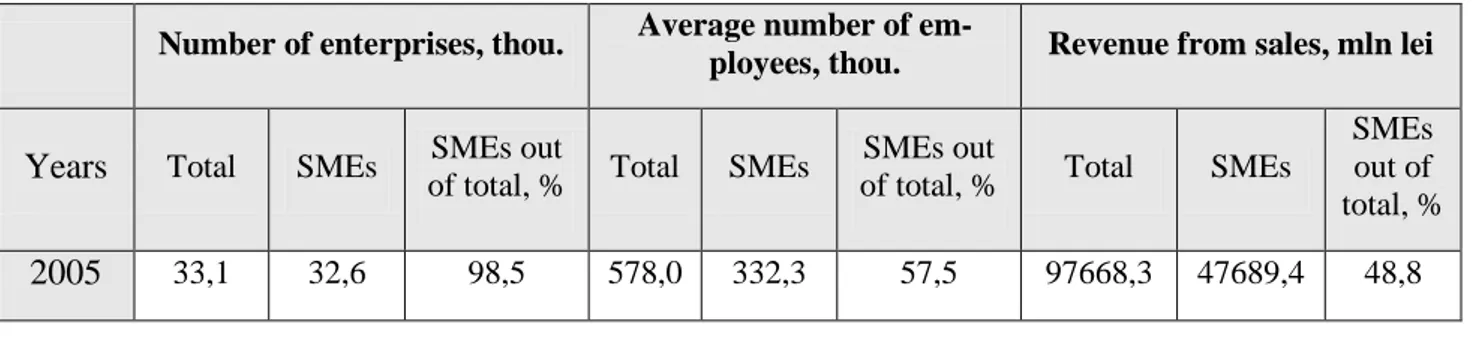

Table 2-1: Progress in transition based on selected EBRD indicators (2008) ……14Table 2-2: Evolution of SMEs in 2005-2007……….. ……15

Table 2-3: The dynamic evolution of SMEs according to type of activity……. ……16

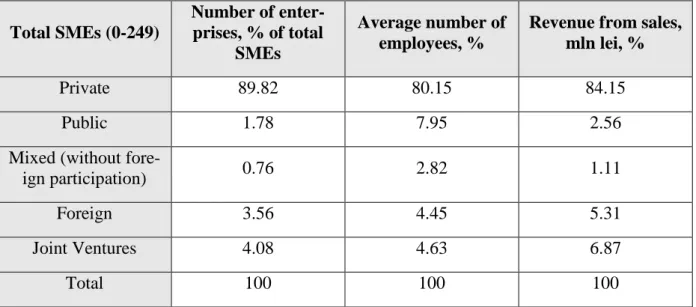

Table 2-4: Distribution of firms by ownership in 2007……….. ……17

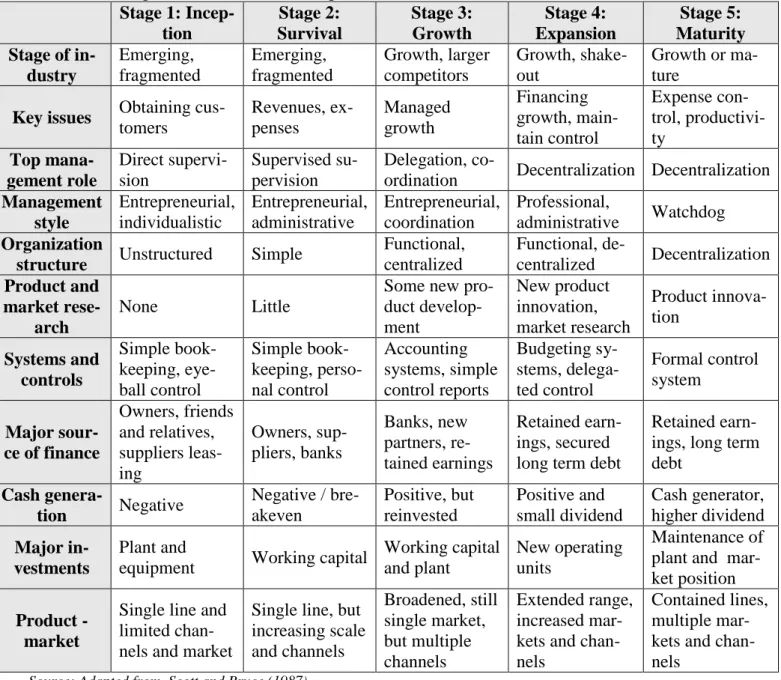

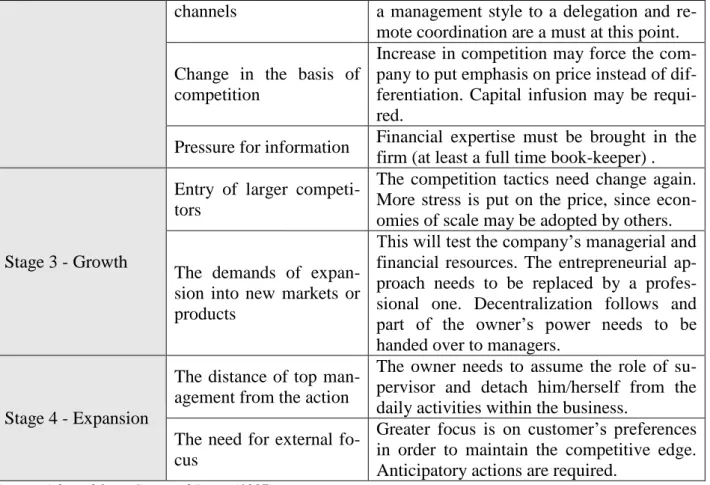

Table 2-5: The 5 stages of a company development………... ……24

Table 2-6: 5 stages of the business development………. ……26

Table 2-7: Crises in the stages of growth in small businesses………. ……26

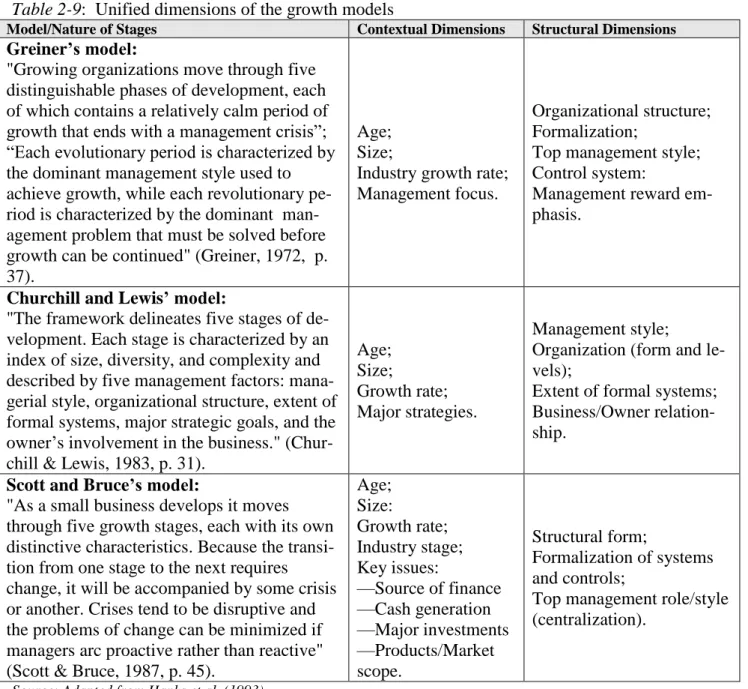

Table 2-8: Unified stages of growth models……….. ……27

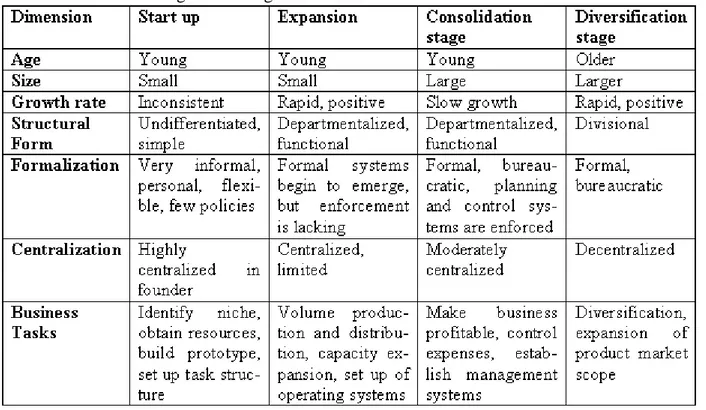

Table 2-9: Unified dimensions of the growth models……… Table 2-10: Hanks et al. generalized growth model……… ……28

……29

Table 5-1: SMEs‘ evolutionary stages (analysis)………... ……49

1

Introduction

The first chapter gives an introduction to the background of this study, followed by the discussion of the research problem of our thesis. Then the research purpose and questions are presented. Af-ter presenting several definitions, the chapAf-ter ends with the delimitations of the study and an out-line of the following chapters.

1.1

Background

As a member of the Central Eastern European countries and with an economy in transition, Moldova is nowadays going through a period of economic recovery after the collapse of the Soviet Union regime. In its transition process, Moldova is facing various challenges in trying to find ways to establish and promote its enterprises, especially small and medium enterprises (SMEs) which are given great importance in the country‘s economic progress and recovery.

During the transition years (1991-2008), little research was available to give a coherent picture of the Moldovan business environment and to determine the obstacles that entrepreneurs and SMEs encounter. What we know is that many of the transition countries encountered difficulties at differ-ent points in time. Most of them face external barriers such as unstable regulations and economic conditions, ineffective banking system, excessive bureaucracy, and high taxation, as well as inter-nal barriers such as limited managerial capabilities, lack of know-how experience, and resistance to change, all of which come as legacies of the previous regime (Welter, 1997; Aidis, 2005a, 2005b; Krasniqi, 2007). These obstacles have negative effects on the economic development of the countries, the well being of their population, and on all the businesses that try to develop in this unfavorable environment. What entrepreneurs then do is tailor their business practices in order to fit into the system of doing business which is specific to transition countries.

Various studies about entrepreneurship and SMEs in transition economies note that even though the transition countries started from approximately same point after the collapse of the regime, they experienced differences that influenced the development of entrepreneurship as the transition process progressed (Mugler, 2000; Fogel & Zapalska, 2001; Pfirrmann & Walter, 2002; McIntyre & Dallago, 2003; Smallbone & Welter, 2001a, 2009; Aidis, 2005a; Aidis & Mickiewicz, 2006). It is here that context gains in importance as it influences the nature and pace of entrepreneurship (Smallbone & Welter, 2009). Entrepreneurship appears to have developed more quickly in coun-tries where reforms proceeded smoothly (Mugler, 2000), whereas in councoun-tries where market re-forms took place slowly or partially, the lack of stability in the external environment has reflected in the characteristics of firms at the micro level (Smallbone & Welter, 2001b; 2006). What was common for all transition countries was the development of private business ownership (Aidis, Welter, Smallbone & Isakova, 2007; Aidis, 2005a).

The need to develop SMEs as part of a wider social and economical restructuring constitutes one of the crucial issues in the transformation from centrally planned into market economy of the tran-sition countries (Smallbone & Welter, 2001a, 2001b, 2006, 2009; Aidis, 2005a; Pfirmann & Wal-ter, 2002; Bartlett, Bateman & Vehovec, 2002; McIntyre & Dallago, 2003; Welter 1997; Bateman, 2000). Moreover, the dynamic growth of SMEs is among the key driving forces behind the eco-nomic recovery in the former Soviet economies especially if we notice that the private sector in these countries consists mainly of SMEs. Their contribution is manifested through the creation of jobs and growth in income, acting as change agents and as a vehicle for economic and social de-velopment in transition economies (Smallbone & Walter, 2009; Aidis, 2005a, 2005b; Christian, 2002; Carree & Thurik, 2002).

In Moldova, the first small businesses appeared in the late 1980s and marked the beginning of pri-vate sector establishment in the economy (Aculai, Rodionova, Baron, Dumitrasco & Welter,

2000). The SME sector has seen an increase in the number of enterprises, with the most typical ac-tivities in trade. However, Moldovan SMEs find it challenging to develop in an unstable business environment that lacks proper market-oriented policies and adequate laws (Welter, 2006; Rutkowski, 2004; World Bank, 2004).

1.2

Problem Discussion

Little research has been conducted on entrepreneurship and SMEs in transition economies. At the same time, even if some data is available, it cannot be applied to all countries, since the picture is different when a closer look is taken at single countries (Welter, 1997).

Research has showed that Moldovan SMEs have a slow evolutionary pattern and tend to seize in growth after a certain period. According to the Center for Strategic Studies and Reforms (CISR, 1999), in 1999 approximately 99% of all Moldovan SMEs were small and only 1% grew to be-come of medium size. Another study showed that 80% of all SMEs are micro enterprises (Euro-pean Commission, 2001). Moreover, according to EBRD/World Bank (2006) estimates, Moldova has the worst quality of governance and environment for entrepreneurship among the transition economies.

We conduct our study on the SMEs within the construction industry in Moldova. Our aim is to analyze several companies as they are presented from the owners‘ perspectives, see their present growth status, and try to link it with external, internal, and intrinsic factors entrepreneurs and their businesses may be affected by. The paper focuses around this issue and tries to determine the link between the growth obstacles and the premature evolutionary slowdown and possible stagnation of SMEs.

In this context, we review theories of small firm growth as a point of departure for our discussion. According to several growth models (Greiner, 1972; Churchill & Lewis, 1983; Scott & Bruce, 1987; Hanks, Watson, Jansen & Chandler, 1993), a natural business growth follows several stages marked by crisis points which signal to the company the need for restructuring in order to advance to the next evolutionary stage. Working with the framework proposed by Hanks et al. (1993), the paper investigates the alterations that their growth model undertakes in the Moldovan SMEs. When using the growth model theories, we also account for the unstable business environment specific to the transition countries and its impact on the development of entrepreneurship and SMEs.

1.3

Research Purpose

The purpose for this research has stemmed out of the belief that a better understanding of the growth of SMEs in Moldova will prove to be a valuable contribution to the studies in this area. Our thesis does not make generalizations based on the empirical data, but instead provide its readers with a closer look at the barriers encountered by entrepreneurs in the field of construction, as well as explore the stage when their companies stagnate.

The research area involves many activities, but this thesis, according to the problem discussion, follows the following research questions:

What are the barriers that hamper the growth of Moldovan construction-based SMEs? Do certain growth barriers prevail at specific developmental stages of SMEs?

According to growth models, what impact do growth barriers have on the normal

1.4

Definitions: Entrepreneurship and SMEs in transition economies

In this section we will provide definitions for ―transition economies‖ and ―entrepreneurship and SMEs‖, which will be used throughout the paper. Transition can be defined as a process of change from a centrally planned to a well functioning market oriented system, involving ―the advance of

the private sector‖ and the ―transformation of the economic, financial and legal institutions‖ in the

market economy (Aidis & Sauka, 2005, p.3). However, not all countries in former Soviet republics may have market economy as the ultimate goal (Smallbone & Welter, 2009). The Moldovan gov-ernment declares that it‘s strongly pro-market oriented, but experience shows that it‘s different in reality. Therefore, we will adopt Smallbone & Welter‘s (2009) explanation that transition refers to ―former centrally planned economies, where sufficient changes have been introduced to allow

pri-vate businesses to exist, although market conditions may have only been partially installed‖ (p.12).

Entrepreneurship is discussed in this paper as it takes place under conditions of transition econo-mies. Entrepreneurship is an ill-defined multi-dimensional concept (Aidis, 2005a; Carree & Thu-rik, 2002). Even with all the researches in the social sciences, it still suffers from a diversity of meanings (Koppl & Minniti, 2003). The definition adopted in this paper is inspired by what other researchers have said: entrepreneurship is the willingness of individuals to create new economic opportunities and take advantage of them by introducing their ideas on the market and making de-cisions on the use of resources and institutions (Wennekers & Thurik, 1999; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Carree & Thurik, 2002). Thus, entrepreneurship in the context of transition economies in-volves both the outcome of the individuals‘ actions, as well as the way they behave, especially be-cause of the rapidly changing nature of entrepreneurship in such conditions (van de Ven & Engle-man, 2004).

In addition, entrepreneurship is examined as it takes place in SMEs. Previous research has indi-cated that the two concepts are found to be in close relationship. As Lumpkin & Dess (1996) put it, ―the small business firm is simply an extension of the individual who is in charge‖ (p.138). Nowa-days, the small businesses are seen more than ever as a vehicle for entrepreneurship: ―certainly,

small firms are an outstanding vehicle for individuals to channel their entrepreneurial ambitions‖

(Carree & Thurik, 2002, p.5). They contribute not just to employment and social and political sta-bility, but also to innovative and competitive power (Wennekers & Thurik, 1999; Carree & Thurik, 2002). Moreover, Acs (1992) also distinguishes the small firm as a vehicle for entrepreneurship among the consequences of the increased importance of small firms.

1.5

Delimitations

In this thesis, we limit our SMEs to those that are located in the capital of Moldova and perform activities in the field of construction. We base our results on a limited number of companies main-ly because of three reasons: time and distance constraints, and some of potential participants‘ re-luctance to take part in such kind of study.

Given that this research is conducted on a small number of SMEs in Moldova, this study does not make generalizations based on its findings, but instead explores some of the problems SMEs in Moldova are faced with, thus increasing the pool of research which is limited in this area. There-fore, it is important for us to clearly state the context within which our study occurs to allow for easier transferability of any findings.

In addition, this study did not examine the exact moment in the company‘s evolutionary life when the growth barriers become noticeable or the moment in which they peak or decline. Another

limi-tation of this study is that is did not seek a general pattern of all companies, since micro and large enterprises did not take part in the research.

Moreover, given that the study is cross-sectional, our conclusions need to be tested over time to improve their credibility.

.

1.6

Outline of study

In this section, the outline of our thesis will be clarified.

To start with, Chapter one has provided the background of the study and the discussion of the re-search problem in this thesis, leading to the formulation of the rere-search questions.

Chapter two presents the frame of reference which includes a compact review of the literature

re-lated to the research problem of this study: entrepreneurship in transition economies and develop-ment of SMEs. Furthermore, the literature review covers the obstacles SMEs face in their stages of development and introduces several growth models which will serve as tools for our analysis.

Chapter three includes a description of the methodological procedures of the study. We explain

our research approach and design, the operationalization of the variables to be used in the data ga-thering tools, our sample selection, as well as briefly discuss the quality standards of our study.

Chapter four presents the empirical data gathered for our study. The results of the questionnaires

are presented, which are intermingled with the detailed presentation of our in-depth interviews.

Chapter five includes the analysis of the empirical data in the context of the developed frame of

reference.

Chapter six reveals the general conclusions of the undertaken study and answers the research

questions.

Chapter seven includes our reflections and recommendations for further research within the area.

Introduction Frame of reference Methodology Empirical findings Analysis Conclusion Discussion

2

Frame of reference

In the frame of reference, we introduce the reader to a compact review of entrepreneurship in a post Soviet context and a brief discussion of the different forms of entrepreneurship under transi-tion conditransi-tions in order to portray to the reader the background in which Moldovan SMEs devel-oped. We put an emphasis on SMEs in transition economies, especially those in the former Soviet Union, because there are few studies on Moldovan SMEs. This will provide us with a better under-standing with the unstable business environment in Moldova, which is of great relevance to the small business growth theories used in the discussion of our research problem: SMEs in Moldova, their growth or lack thereof.

2.1

Entrepreneurship in a post-Soviet context

The late 1980s were characterized by the downfall of the Soviet Union and the following collapse of the centrally planned economic system. Since the 1990s, the former Soviet countries expe-rienced a social, political, and economic transformation of huge proportions (Smallbone & Welter, 2001a, 2001b, 2006, 2009; Welter 1997; Aidis, 2005a; Pfirmann & Walter, 2002; Bartlett et al., 2002; McIntyre & Dallago, 2003). The process of economic restructuring has resulted in profound and dramatic changes to their economic, political, and social landscapes (Aidis et al., 2007; Aidis, 2005a). These changes were accompanied by an increase in newly created private enterprises mainly due to the growing consumer demand for products and services which were scarce under the former regime (Aidis, 2005a). The development of private business ownership was one major change common for all ex-Soviet countries (Aidis et al., 2007).

Nevertheless, not all countries followed the same transition path. In this regard, Smallbone and Welter (2001b) propose not to view transition as a deterministic process but rather one which can follow different paths and which is subjective to an array of factors. Various studies about entre-preneurship and SMEs in transition economies note that even though the transition countries started from approximately same point after the collapse of the regime, there are still a number of the differences to be noticed in the development of entrepreneurship as the transition process pro-gressed (Larcon, 1998; Trzeciak-Duval, 1999; Mugler, 2000; Fogel & Zapalska, 2001; Pfirrmann & Walter, 2002; McIntyre & Dallago, 2003; Smallbone & Welter, 2001a, 2009; Aidis, 2005a; Ai-dis & Mickiewicz, 2006). These differences can be observed in the scale and efficiency of the reform process, as well as in the economic and political processes and levels of social development for entrepreneurial ventures (Fogel & Zapalska, 2001; Smallbone & Welter, 2001b). Mugler (2000) reaches the conclusion that entrepreneurship appears to have developed more quickly in countries where reforms proceeded smoothly and where there has been a strong pre-socialist indus-trial tradition. In countries where market reforms did not proceed easily, the turmoil on the eco-nomic and political arena has reflected in the characteristics of small businesses (Smallbone & Welter, 2001b; 2006).

Various researchers have tried to assess the importance of different historical influences on entre-preneurship development in a post-Soviet context and ask whether there is a Soviet legacy influen-cing the process of entrepreneurship (Smallbone & Welter, 2001a; 2009; Yalcin & Kapu, 2008; Aidis, 2005a; Scase, 1997, 2003). Among the main factors that are important in explaining today‘s level of entrepreneurship and the starting conditions in the early 1990s, Welter (2006) mentions the state of the pre-socialist entrepreneurship progress in connection with the individual background in entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship developments during the Soviet times. Even under condi-tions of a centrally planned economic system, there still were different forms of private entrepre-neurship besides entrepreentrepre-neurship within state enterprises. Some of these forms of

entrepreneur-ship survived becoming a part of the new private business sector in the transition period (Small-bone & Welter, 2001a).

―Nomenclatura‖ businesses represent one form of entrepreneurship under transition conditions which was present particularly in the former Soviet republics (Smallbone & Welter, 2001a). Bau-mol (1990) considers this type unproductive or even destructive since the political influence is used for private gain by protecting market niches. Roberts and Tholen (1998) notice a dominance of the ―Mafia-style capitalism‖, given that the same ruling elites from the former Soviet Union re-mained in power in the new independent countries (as cited in Aidis, 2005a).

Other types of entrepreneurship in transition countries include self-employment and part-time businesses. They resulted to be ―anchors‖ for many former employees of state-owned firms, who have either lost their jobs through the restructuring of state-owned enterprises or forced to take a leave of absence (Smallbone & Welter, 2001a).

Some research has been predisposed to identify entrepreneurship in former Soviet Union countries as represented mainly of proprietors who start up a business because of necessity (Scase, 1997, 2003; McIntyre, 2003; Dallago, 2003). In assessing the role of small businesses in transition econ-omies, Scase (1997) classified most small businesses in transition countries as proprietorship and not entrepreneurship. In Scase‘s (1997) view, "proprietorship" is used to define the ownership of property and other assets that may be used to realize profits but are not employed for wealth accu-mulation in the long run. Scase (1997) contends that these activities do not generate income which is meant to be reinvested, but rather offer employment and provide income to the owner and em-ployees for their own disposal. This implies that a large proportion of SME owners in transition countries would fall into the ―proprietorship‖ category, at least when their businesses are started (Aidis, 2005a). However, it should be mentioned that other researchers have contested this view. Dahlquist and Davidsson (2000) concluded that initial startup motives are not a reliable predictor of later business growth (as cited in Welter, 2006). In addition, the authors emphasize that entre-preneurship is also influenced by the learning capacity of the individuals. Welter (2006) suggests that proprietorship may be a feature of the early stages of transition, losing importance in countries at a more advanced stage of change to a market-oriented economy.

Another characteristic of entrepreneurship development in transition countries constitutes the transfer of illegal entrepreneurship practice to legal private enterprises under the new market econ-omy (Aidis, 2005a). In addition, a large informal sector emerged as a result of the black market ac-tivities in the centrally planned economies (Welter, 1997; Christian, 2002). Many of the acac-tivities of SMEs in countries with high administrative barriers are being performed out in the unofficial economy (Welter, 1997). Christian (2002) asserts that smaller firms have a greater need to operate in the unofficial economy because of the higher load that taxes and regulations place on them. Networks and informal connections gain in importance under such conditions especially in the countries of the former Soviet Union. It is the so-called ―blat‖, an informal network cooperation which is a means to acquire needed good and services (Ledeneva, 2006). It gains in importance when transforming entrepreneurship that existed under central planning into entrepreneurial activi-ties during transition. More generally, networks and connections are essential for entrepreneurship under transition conditions, as they are based on mutual trust and reduce business risks in an unst-able economic and political environment (Smallbone & Welter, 2001a). However, such practices might go against the well-being of the company in the long run since entrepreneurs conduct their business with the same people over and over again (Welter, 2006).

2.2

Role of SMEs to the economic development

The restructuring period in ex-Soviet countries was accompanied by an increase in new private businesses. The development of SMEs is one of the issues in the transformation from centrally

planned into market economy as part of a wider social and economical reorganization (Smallbone & Welter, 2001a, 2001b, 2006, 2009; Aidis, 2005a; Pfirmann & Walter, 2002; Bartlett et al., 2002; McIntyre & Dallago, 2003; Welter 1997; Bateman, 2000). As the privatization process does not necessarily result in an improved economic situation of the country, the emergence and growth of SMEs is of special importance (Aidis & Mickiewicz, 2006). Moreover, the dynamic growth of the new private sector is among the key driving forces behind the economic recovery in the former Soviet economies. Still, Glinkina (2003) challenges the view that small businesses are forces of economic progress in transition economies by arguing that in such conditions proprietorship and not entrepreneurship emerges with the sole purpose of survival and consumption.

Nonetheless, SMEs are given a great role in the economic recovery of the transition economies. These enterprises are regarded as change agents in transforming economies and are seen as a ve-hicle for economic and social development in transition economies (Smallbone & Walter, 2001a, 2001b, 2009; Aidis, 2005a, 2005b; Christian, 2002). In Moldova, the first small businesses ap-peared in the late 1980s, signaling the beginning of private sector establishment in the economy (Aculai et al., 2000). From all the ex-communistic countries only Albania and Romania held firm to the idea that giant enterprises were the most efficient (Bartlett et al., 2002).

SMEs are important in transition economies as they contribute to employment, output, and capital generation (Smallbone & Welter, 2001b; Aidis & Mickiewicz, 2006; Trzeciak-Duval, 1999). Em-ployment is increased as a way to make up for some of the labor released from large state-owned enterprises as a result of the post-socialist economic restructuring. But still, this has been one of the few sources of new jobs during the transition period (Smallbone & Welter, 2009). However, even if SMEs do not provide the population with ―net new jobs‖, they ―reduce the erosion of

hu-man capital by providing alternative employment opportunities for relatively skilled yet unem-ployed workers‖ (Aidis, 2005a, p.2).

SMEs have also facilitated the introduction of a wide range of new technologies and managerial techniques, as well as create new business fields and contribute to the development of service, knowledge-based industries, and innovation (Welter, 1996; Smallbone & Welter, 2001b; Aidis & Mickiewicz, 2006; Aidis, 2005a; Dyker, 1997, as cited in Bateman, 2000). However, in transition economies, the innovative activity in SMEs is hampered by the weak nature of public institutions that support innovation (Smallbone & Welter, 2009).

In spite of all formal institutional limitations, SMEs have emerged in transition economies. But even with the attested contribution of SMEs to the economic recovery in former Soviet countries, Aidis & Sauka (2005) note that the development of the SME sector was ignored due to the strong accent on the reorganization and privatization of state enterprises, resulting in less resources being redirected to the needs of SME development (as cited in Aidis, 2005a). As a result of institutional policies that are not market-oriented to a full extent, SME development is seriously held back. The biggest problems in these countries stem out of the lack of consistent strategies, which creates a bureaucracy unfavorable to SMEs (Welter, 1997).

2.3

Barriers to SME growth

Since the beginning of the economic liberalization, the SME sector has gone through considerable development (Krasniqi, 2007). But even though a great number of new small businesses have en-tered the market, they have not grown as rapidly as might have been expected (Bartlett & Bukvic, 2001). The large majority of SMEs are of very small size in nearly all countries, displaying a tradi-tional character and risk-averse attitude, with survival as their major concern, while competitive-ness and growth being of less concern to entrepreneurs (Dallago, 2003). Moreover, their

contribu-tion to economic development in transicontribu-tion economies in terms of jobs, innovacontribu-tion, and external income generation is rather limited (Smallbone & Welter, 2006).

In countries where the transformation process has been slow, the inadequate institutional environ-ment results in key barriers that impede the developenviron-ment of SMEs. Therefore, SMEs do not grow sufficiently and rapidly enough to carry out their role as engines of economic growth. These bar-riers can result in a misdirection of entrepreneurs from productive into unproductive forms of ac-tivities (Baumol, 1990; Bartlett & Bukvic, 2002). This means that resources are being diverted to deal with unnecessary costs instead of being put to productive use, resulting in restricted entrepre-neurship and limited contribution of SMEs to the country‘s economic growth (Smallbone & Wel-ter, 2006, 2009).

Welter (1997) proposes a classification of barriers into external and internal barriers. The external barriers comprise the external environment of private enterprises: the macro economic develop-ment, legal and regulatory environdevelop-ment, financial infrastructure, taxes, corruption, and unfair com-petition (Welter, 1997; Aidis, 2005a, 2005b; Krasniqi, 2007). Internal barriers stem out of the structure of the individual enterprise and the possible weaknesses of the owner‘s and employees‘ knowledge about the requirements of the market economy and skill-related competencies (Welter, 1997). We will also introduce another dimension in this context and namely the intrinsic factor. It deals with the owner‘s willingness to develop the enterprise and could be related to the prevalence of former business mindset, attitudes, and values (Chelariu, Brashear, Osmonbekov & Zait, 2008).

2.3.1 External barriers

Macro economic development

Lumpkin & Dess (1996) affirm that even if small businesses are growth oriented, the external en-vironment can still slow down their ability to achieve their growth potential. When it comes to transition economies, all of them suffered from inappropriate economic structure inherited from the previous system. As Smallbone and Welter (2001a) note, a ―hostile economic environment‖ with high inflation rates, increasing unemployment rates, and declining real earnings characterized the transition process (p.249). Moreover, SMEs in transition countries are faced with decreased demand for the product and display low purchasing power as a result of a very tough domestic and foreign competition (Krasniqi, 2007; Aidis 2005a). Access to materials, late payments by clients, and public procurement rules are other barriers that hamper SME development (Bartlett & Bukvic, 2001).

Freedom of entry and privatization improved the overall climate for the SME sector growth and encouraged potential entrants (Krasniqi, 2007). But this concerns mainly the sectors with low in-vestment requirements such as trade and services. These sectors are featured by high profitability, quick turnover of funds, and in case of negative changes in the environment by the possibility of a quick shutdown of the enterprise and transfer of capital into other spheres of activity (Aculai et al., 2000). Transition countries still stagnate in those sectors where entry barriers in terms of invest-ments are relatively high such as the manufacturing sector (Welter, 1997). This affects the entre-preneurs‘ decision to invest, especially in projects that require a longer time to produce return (Krasniqi, 2007). Moreover, Bateman (2000) also asserts that the fact that most active SMEs are engaged in small-scale retailing and importing activities will prove to be of great concern in the long run.

Legal and regulatory environment

The legal framework in a country involves the creation of laws relating to property, bankruptcy, commercial activities, contracts, and taxes (Smallbone & Welter, 2006; Welter 1997; Krasniqi,

2007). All of the transition economies have made efforts in building up the legal framework, al-though some were more successful than others. Some countries still face the lack of appropriate legal framework or lengthy administrative procedures such as registration with the tax, opening a bank account, or obtaining licenses (Christian, 2002). And even if the legal system is in place, the frequent changes in laws have negative effects on businesses due to higher level of uncertainty and increased compliance costs (Hashi & Mladek, 2000; Smallbone & Welter, 2006; 2009; Bartlett & Bukvic, 2001). The weak law enforcement and the frequent changes cause further confusion among business owners and government officials (Smallbone & Welter, 2009). As Bartlett and Bukvic (2001) assert, ―complicated laws, rules and regulations concerning companies can be

es-pecially tough on small and growing companies‖ (p.6). Moreover, entrepreneurs also face

prob-lems such as the inability of state employees to offer them appropriate services as a result of low public sector salaries, and lack of experience and knowledge about market economy conditions (Krasniqi, 2007; Welter, 1997; Smallbone & Welter, 2006; 2009). Therefore, time and money con-suming formalities coupled with personnel that lack education and training act as obstacles slow-ing down the growth of firms.

Financial infrastructure

The financial infrastructure constitutes another major barrier to small business development in transition countries where market reforms took place slowly or partially (Welter, 1997; Bartlett & Bukvic, 2001; Hashi 2001; Aidis 2005a; Earle & Sakova, 1999). Financial barriers that affect SMEs include the high cost of credit, relatively high bank charges and fees, high collateral re-quirements, and a lack of outside equity and venture capital (Bartlett & Bukvic, 2001; Welter, 1997; Smallbone & Welter, 2009).

In many ex-Soviet countries, the banking system is still highly inadequate. State-owned banks fa-vor their old established customers due to their knowledge of customers and also as a result of the connections from the former regime (Christian, 2002; Welter, 1997). When it comes to the newly established SMEs, banks do not possess experience and know-how in dealing with them (Small-bone & Welter, 2006; Christian, 2002; Krasniqi, 2007). Moreover, banks face liquidity constraints and are reluctant to finance small firms as a result of inherited liabilities from the central planning period (Welter, 1997; Smallbone & Welter, 2006).

Taxes

The overall tax burden impedes the development of small businesses (Hashi, 2001; Bartlett & Bukvic, 2001). What is meant here by tax burden includes not only the rate of tax, but also the way in which the tax system is administered (Christian, 2002). Tax systems tend to discriminate against small firms, as high rates of taxation and social insurance contributions added to enterprise income taxes place a larger tax load on small enterprises (Christian, 2002; Smallbone & Welter, 2001b). When compared to European Union countries‘ average tax rates, Hashi and Mladek (2000) con-clude that the tax rates and employee contributions in transition economies are relatively high. Al-so, the complicated ways of taxation force SMEs to employ outside consultants, which only further increase the transaction costs (Krasniqi, 2007).

Entrepreneurs choose to evade taxes given the business environment where government typically considers small businesses mainly as a source of revenue and where inadequate law enforcements lead to corrupted behavior (Smallbone & Welter, 2006). As Smallbone and Welter (2001b) put it, ―due to lack of commitment on the side of government, SMEs are more commonly seen as sources

for income for state authorities and officials, rather than as potential motors of economic devel-opment‖ (p.74). The tax system combined with the ―heavy-handed bureaucracy‖ lead to evasion

(Bartlett & Bukvic, 2001, p.6). It is a common practice for the transition economies in which the governmental officials intentionally overregulate the system in order to extract benefits from the

helpless business sector (Shleifer & Vishny, 1994). Smallbone & Welter (2006) mention evasion strategies such as setting up ―fictitious‖ enterprises and paying employees‘ salaries in cash, the lat-ter resulting in violation of labor law.

Corruption

Corruption represents another strong characteristic of the transition economies and it continues to be an obstacle for the development of the private sector (Aidis, 2005a; Frye & Schleifer, 1997; Bartlett & Bukvic, 2001; Smallbone & Welter, 2001b). The collapse of the socialist regime has re-sulted in an environment which was appropriate for the development of a ―grabbing hand model‖ of government intervention (Aidis, 2005a). Frye and Shleifer (1997) talk about this model men-tioning that it is characterized by corrupt behavior used for private gain and goes against the de-velopment of the private business. The ruling political elite still have considerable power over many procedures in establishing and promoting SMEs and may abuse its position by demanding bribes (Bartlett & Bukvic, 2001; Christian, 2002). The so-called ―nomenclatura‖ businesses use political influence to protect themselves from competition and receive preferential treatment from government (Smallbone & Welter, 2001b). Moreover, trust in institutions is lowered as a conse-quence of their corrupted behavior (Uslaner, 2003, cited in Wallace & Latcheva, 2006).

For example, an increase in the number of permits and licenses leads to a higher cumulative bribe to be paid to politicians and bureaucrats, thus deterring many firms from pursuing their activities (Shleifer & Vishny, 1994). Therefore, corruption has a negative influence because it makes busi-ness transactions more costly (Krasniqi, 2007). Moreover, the same author reaches the conclusion that corruption not only encourages the unofficial economy, but also discourages both domestic and foreign investments which are badly needed in transaction economies (Krasniqi, 2007). Weak-ly specified regulations coupled with weak public law enforcement encourage corruption both when a company is registered at the beginning and in everyday economic transactions (Smallbone & Welter, 2006; 2009).

Informal networks gain in importance in the absence of working formal structures. Business own-ers depend on them in the absence of developed business infrastructure and support services (Ai-dis, 2005a).

Unfair competition

The early transition period was dominated by oligopolies and monopolistic enterprise structures as a result of the state ownership of almost all firms under central planning (Christian, 2002). Because relationships were formed between government officials and enterprise managers, state-owned en-terprises enjoyed access to customers in the case of government contracts. This happened more of-ten in the manufacturing and construction sectors in most transition countries, which are dominat-ed by monopolies in the form of the former state-owndominat-ed enterprises which have been privatizdominat-ed (Welter, 1997).

2.3.2 Internal barriers

For many business owners in transition countries, private business ownership indicated the start of a new career (Roberts & Zhou, 2000). In a survey conducted on support needs in the Ukraine, Moldova and Belarus, independence represented the most frequent incentive to start a business, followed by ―a desire to boost income" and "personal fulfillment" (Smallbone & Welter, 2001a). Only a few respondents mentioned unemployment as a reason for start-up. The authors call them "reluctant entrepreneurs" (Smallbone & Welter, 2001a). This is in accordance with several

researchers‘ views that in transition economies, entrepreneurs are necessity rather than opportunity driven (Scase, 1997; 2003; Glinkina, 2003; Dallago, 2003).

The same study on entrepreneurs in the Ukraine, Moldova and Belarus indicate that entrepreneurs possess a high level of education (Smallbone & Welter, 2001a). However, since the management techniques of state enterprises were different under central planning, they become obsolete in the new conditions of market economies, resulting in lack of specialized knowledge and techniques (Welter, 1997; Dallago, 2003).

According to Storey (1994), one of the greatest factors contributing to the performance of the small business is represented by the human capital of the entrepreneur especially in the form of managerial skills. In former Soviet Union countries, entrepreneurs are reluctant to admit their lack of skills as they perceive it as a managerial weakness and tend to blame the problems of their companies on the external environment (Welter, 1997). Or it can happen that private business owners are not aware of their skill shortcomings and this can impede the survival and growth of private businesses in transition countries (Aidis, 2004, as cited in Aidis, 2005a). But these know-how skills and techniques are passing problems; specific managerial techniques prove to be more important in the long run (Welter, 1997). Moreover, the individuals‘ capacity of learning over time, as well as the possibility of possible changes in external environment should not be underestimated (Aidis, 2005a).

2.3.3 Intrinsic factors

Intrinsic factors are mainly related to the owner‘s willingness to expand the business. The attitude towards expanding a firm has been discussed by Wiklund, Davidsson and Delmar (2006). Accord-ing to these authors, some small business managers are reluctant to expand their companies if they have the expectations that the consequences of growth will be negative. In other cases, it may hap-pen that managers do not fully realize the growth potential of their enterprises.

In the case of transition countries, the communistic legacy in terms of attitude and entrepreneurial mindset follows the entrepreneurs who still put an emphasis on creating strong ties with the state administration and focus on ways to cope with the external environment instead of building up other skills such as the ability to decide autonomously and develop a positive attitude towards risk (Welter, 1997). It is the same way that Earle and Sakova (1999) characterize the ―homo

sovieticus‖, mainly as displaying reduced risk tolerance, increased dependence on the state, and

psychological barriers to business ownership. Apathy, helplessness, and the attitude that private entrepreneurship runs against the social norms are aspects of the communistic way of thinking as well (Smallbone & Welter, 2001a; Chelariu et al., 2008; Yalcin & Kapu, 2008). At the same time, Smallbone and Welter (2009) point out that to label entrepreneurs in the countries of former Soviet Union as displaying ―learned behavior‖ does not always hold, since there were individuals who were quick at taking advantage of opportunities (p.41). Moreover, this fact also reveals the noteworthy capability of individuals to adapt to changing conditions (Smallbone & Welter, 2009).

2.4

SMEs in Moldova and their barriers to growth

So far, we reviewed the literature on transition countries and their SMEs. External, internal, and intrinsic barriers that hamper the development of SMEs have been identified. In order to better grasp our research problem, we believe it is necessary to gather as much information about our specific case, that of Moldova, and present it in this frame of reference.

The literature overview will prove that Moldova still carries the burden of communism in many of its aspects, including in the development of its SMEs. The next paragraphs will depict how differ-ent processes took place as part of the transformation from cdiffer-entrally planned economy to a market-oriented one. We will also inform the reader of the success rate of the implementation by the gov-ernment of various reforms, followed by a brief presentation of SMEs, and a more ample descrip-tion of their barriers to growth. We would like to remind the reader that in our thesis entrepreneur-ship is viewed as it takes place in SMEs. Also, data concerning Moldovan SMEs proved to be poor or inexistent, which made the collection of information a bit difficult.

2.4.1 Market reforms and the development of private entrepreneurship

One of the most important findings in the SME literature is that context matters because it has an effect on both the role of small firms and their structure and performance (Karlsson & Dahlberg, 2003). Davidsson (2003) insists on the need to recognize the heterogeneity of environmental con-ditions when assessing the development of entrepreneurship (as cited in Smallbone & Welter, 2009). Context becomes especially important in transition countries where market conditions are only partially installed, as it displays a strong influence on the pace of entrepreneurship develop-ment (Smallbone & Welter, 2001a, 2001b, 2009). These countries have experienced economic and social change, including the development of a new private sector, as well as considerable change in laws, regulations, and norms (Raiser, Di Tommaso & Weeks, 2001). In the following paragraphs, we will discuss how well the market reforms have been implemented in Moldova as this context has implications for the extent to which a legal SME sector is likely to develop. Moreover, creating a good business environment is a key aspect of the transition from central planning to a market economy as it stimulates entrepreneurial activity and leads to job creation (Steves, Fankhauser & Rousso, 2004).

The scope of Moldova's economic collapse surpassed that of all the other former Soviet republics following the break-up of the Soviet Union, as Moldova faced one of the deepest and most ex-tended recessions among the transition economies (Hensel & Gudim, 2004; World Bank, 2004). By the late 1990s Moldova's official economy had declined to around two fifths of its Soviet size, whereas most of the former Soviet economies in Central Europe managed to go back to their 1990 levels (Hensel & Gudim, 2004). As it might have been expected, Moldova‘s transition to a market economy did not prove to be an easy road given that it experienced an unstable internal political environment, high susceptibility to external shocks, and mixed reform implementation (World Bank, 2004). Policies related to the property reform and the private sector have been proposed and accepted, but, at the same time, no measures were taken by the authorities to create a favorable de-velopment environment (Munteanu, 2004).

Moldova introduced its first reforms at the beginning of 1990s. It is the period after the collapse of Soviet Union when GDP plummeted by two thirds over 1991-1994, and so did employment and income (Ministry of Economy/TACIS, 2004). The so-called ―first wave‖ reforms can be associated with the year 1992 when macroeconomic stabilization was achieved quickly through market-oriented laws, introduction of the national currency, liberalization of prices, suppression of infla-tion, and privatization of enterprises (Ministry of Economy/TACIS, 2004; World Bank, 2004). Monetary policies were introduced to end the hyperinflation experienced in the early 1990s (Hen-sel & Gudim, 2004). At this point in time, Moldova was viewed as a successful reformer. The Economist (1995) labeled Moldova at that time as the ―laboratory of sound reforms‖ (CISR, 2002).

In terms of privatization, this process started step by step, the first one being ―The Draft Economic

Reform Program of the Government of Moldova" in 1991 (Fedor, 1995). Due to its newness and

make any intervention where it felt needed. A second major step was established in 1994 with the "Program of the Activity of the Government of the Republic of Moldova for 1994 to 1997" that fo-cused on the restructuring and privatization of SMEs (Fedor, 1995). As a result, many state-run small and medium-sized enterprises quickly sold off (Hensel & Gudim, 2004). This small-scale privatization, as in other transition countries, contributed to the establishment of entrepreneurship (Smallbone & Welter, 2009).

The development of entrepreneurship was sought through other means as well starting with the first ―Law on Propriety‖ adopted in 1991 with the purpose of securing the right to private property (CISR, 2002, p.50). During initial stages of reform, non-state enterprises appeared in the form of operatives (Aculai, Rodionova & Vinogradova, 2006; CISR, 1997). In 1991, 3,500 co-operatives existed, which were involved in construction, consumer services, and the production of consumer goods. Later on, after the approval of the ―Law on Entrepreneurship and Enterprises‖ in 1992, which established juridical and organizational forms of entrepreneurial activities, many co-operatives were transformed into individual enterprises, joint-stock companies, limited liability companies, and other private forms (Aculai et al., 2006). The number of enterprises registered in Moldova was continually growing during the period of transition, although at varying rates. Be-tween 1992 and 1995, the annual growth rate was as high as 150 to 200 per cent, indicating oppor-tunity exploitation by Moldovan people, but also decreasing living standards that forced some in-dividuals to start their own businesses (Aculai et al., 2006).

Mass privatization started after the issue of the 1995 bill called "Program for Privatization for

1995-1996" which introduced cash auctions and capital markets, offering all the tools for the

mar-ket process to evolve (Fedor, 1995). The reason why this mass privatization started was due to the fact that the majority of the companies that were going through the restructuring process were run-ning at a loss and the government could not afford to subsidize them. The Moldovan government felt that salvation could come from transferring the property rights, together with the risks and re-sponsibilities, to the private entrepreneurs who would presumably handle the establishments more effectively. The companies were sold either as a whole when a small scale privatization happened, or piece by piece (plant or equipment) when bigger companies were involved and single buyers were either hard to find or uninterested in purchasing the entire enterprise (Fedor, 1995).

Even though the legal framework and government support were present before 1994, the real pri-vatization process started to grow around 1997. According to World Bank (1998), 1997 was the year in which 2,535 state-owned companies were transferred to private owners, out of which 1,139 were medium and large. New business establishments were on the other hand in a bigger amount, numbering 3,929 in the same year. Either way, the same source reveals that the private sector slowly started to grow and the percent share of GDP produced by non-state owned enterprises grew accordingly, starting with an increase of 20 per cent in 1994, followed by a steady 10 per cent annual increase all the way to the year 1996 when it reached 40 per cent (World Bank, 1998). Nevertheless, Moldova experienced trouble by mid ‗90s when its ―reform experience […] followed

a decidedly stop-and-go pattern‖ (World Bank, 2004, p.10). In the following years, Moldova faced

political instability, economic depression as a result of the 1998 Russian financial crisis, sudden increase in poverty rates, and the mass labor migration abroad (Ministry of Economy/TACIS, 2004; World Bank, 2004). Several reforms were implemented successfully and included rationali-zation of the energy sector, pension reform, and land privatirationali-zation (World Bank, 2004). Still, the same source relates that the government failed with the reforms in the end since the ―political

con-sensus backing the reformers […] was fragile‖ (World Bank, 2004, p.10).

CISR (2002) argues that the end of 1990s marked the ―bottom‖ of the crisis in Moldova. Accord-ing to Ministry of Economy/TACIS (2004), 2000-2001 represented another turnAccord-ing point for

Mol-dova, as GDP began to grow again, unemployment became stable, and positive changes in the in-dustry, agriculture and constructions were noticed.

If we look at the nowadays situation after more than 15 years of transition in terms of selected EBRD indicators (EBRD, 2008), Moldova has been relatively slow with respect to the framework conditions needed to establish a market economy, with areas such as enterprise restructuring, com-petition policy, non-banking financial institutions and infrastructure reform changing particularly slowly. Moreover, Moldovan entrepreneurs have to deal with numerous administrative interven-tions from the government, which further slows down the process. It is therefore not surprising that the pace of small business growth in Moldova has been relatively slow, given that entrepreneurship and private sector business development depend on the wider process of institutional and economic restructuring. Table 2-1 depicts the progress in transition, where indicators range from 1 (little or no change from a rigid centrally planned economy) to 4+ (which represents the standards of a ma-ture market economy).

Table 2-1: Progress in transition based on selected EBRD indicators (2008)

2008 Large-scale privatization 3 Small-scale privatization 4 Enterprise restructuring 2

Price liberalization 4

Trade and forex system 4+

Competition policy 2+

Banking reform 3

Non-bank financial institutions 2 Infrastructure reform 2+

Private sector share in GDP 65%

Source: EBRD (2008)

The main inefficiencies with the reforms are created by the so-called ―groups of interest‖ that maintain control and are hostile to foreign investments and private owners (CISR, 1999). They have taken advantage of the country's weak political structures and have slowed down the structur-al reforms as much as possible (Hensel & Gudim, 2004). This phenomenon proves to be common for transitional periods in which the country‘s scarce goods are transferred from the state to the private holder based on a very fragile and biased distribution system.

2.4.2 Relevance of SMEs today

This section will present the situation of SMEs in Moldova1 as of 2005. Certain features will be used to show to show their importance in Moldova‘s economic recovery especially when it comes

Criteria Micro enterprise Small enterprise Medium enterprise

Average number of employees 1-9 10-49 50-249

Annual sales income (mln lei) <3 <25 <50 Total annual cost of assets <3 <25 <50 Classification of SMEs according to www.businessportal.md

to job creation and income generation. This is another means to portray the background for the re-search problem of our thesis which is related to the SMEs‘ barriers to growth.

According to the National Bureau of Statistics of Moldova (NBSM)‘s press release (2007), in 2007 there were 39.3 thousand SMEs whose number increased by 10.7 per cent in comparison to that from last year (2006). The SME sector has seen an increase in the number of enterprises. However, the increasing number in enterprises does not necessarily portray the situation as SMEs, as Moldo-van SMEs can be characterized as ―too many, too small‖ (Dallago, 2003). The evolution of SMEs between years 2005 and 2007 can be followed in the following figure (figure 2-1):

Figure 2-1: Evolution of SMEs, 2005-2007

Source: NBSM (2007)

In 2007, the SME sector represented 98.3 per cent from the total number of enterprises in Moldo-va. SMEs play an important role in job creation since they employ 59.8 per cent of the total num-ber of employees in all Moldovan enterprises. Also, SMEs make up for 45 per cent of revenues from sales, whereas the rest of the firms (1.7 per cent) account for 55 per cent. Aculai et al. (2006) give an explanation for this: the discrepancy can be justified by the fact that many small enterpris-es have low potential for development. They encounter various obstaclenterpris-es such as lack of skills and experience about the running of a business, unfavorable business climate, as well as limited access to financial capital. In addition, some entrepreneurs are not interested to grow their companies since they remain satisfied with the minimum level of income that can be generated. On the other hand, the capacity of public enterprises is much higher: they have the necessary equipment, per-sonnel and markets for development, as well as support from government (Aculai et al., 2006). Ta-ble 2-2 portrays the main indicators that show the progress of SMEs in between 2005 and 2007:

Table 2-2: Evolution of SMEs, 2005-2007

Number of enterprises, thou. Average number of

em-ployees, thou. Revenue from sales, mln lei

Years Total SMEs SMEs out

of total, % Total SMEs

SMEs out

of total, % Total SMEs

SMEs out of total, %

2006 36,1 35,5 98,3 574,9 332,7 57,9 117372,4 54280,7 46,3

2007 40,0 39,3 98,3 574,1 343,5 59,8 148512,7 66786,6 45,0

Source: NBSM (2007)

The situation of SMEs in Moldova can be characterized by increasing rates of growth in the num-ber of SMEs representing various branches (table 2-3). The most typical activity for SMEs is trade. Forty one per cent of all SMEs have registered wholesale and retail trade as their main activity. This sector is followed by real estate, renting and business services (13.3 per cent) and manufactur-ing industry (12.7 per cent). Trade prevails among the types of activity of SMEs because this sec-tor is featured by high profitability, quick turnover of funds, and in case of negative changes in the environment by the possibility of a quick shutdown of the enterprise and transfer of capital into other spheres of activity (Aculai et al., 2000). DAI (2000) mention the construction sector as pre-valent as well due to its activities that require low start-up costs and relatively low skill require-ments.

Table 2-3: The dynamic evolution of SMEs according to type of activity

2006 2007 2007 increase from 2006 SMEs (thou.)

SMEs out of: SMEs

(thou.) total firms, %

SMEs out of: total firms, % total SMEs, % total firms, % total SMEs, % Total 35,5 98,3 100 39,3 98,3 100 110,6 out of which: Agriculture, hunting and

fo-restry 2,0 95,4 5,6 2,1 96,5 5,4 106,0 Manufacturing industry 4,5 96,6 12,7 5,0 97,1 12,7 110,5 Electricity, gas and water 0,1 80,6 0,3 0,1 82,0 0,3 109,8 Construction 2,1 99,0 5,9 2,4 98,8 6,1 114,7 Wholesale and retail trade 14,7 99,1 41,4 16,1 98,9 41,0 109,6 Transport and communications 2,5 98,8 7,0 2,8 98,6 7,2 111,3 Real estate, renting and business servic-es 4,5 99,0 12,7 5,2 99,1 13,3 116,8 Other activities 5,1 98,1 14,4 5,6 97,9 14,0 108,2 Source: NBSM (2007)

Nowadays, private firms make up the overwhelming majority of enterprises registered in Moldova. The statistical data of NBSM show that in 2007 the absolute majority of SMEs (90 per cent) are privately owned. This results from a combination of ―de novo‖ enterprises on one hand, and ongo-ing privatization of former state-owned enterprises on the other (Aculai et al., 2006). Private SMEs employ 80 per cent of the total number of SMEs‘ employees and their turnover is 84 per cent of the total SMEs turnover. Moreover, they account for 65% of GDP (EBRD, 2008). The data pre-sented in the following table (table 2-4) concerning the distribution of firms by ownership offer a view of the considerable place occupied by private SMEs in the Moldovan economy.

Table 2-4: Distribution of firms by ownership, 2007

Total SMEs (0-249) Number of enter-prises, % of total SMEs Average number of employees, %

Revenue from sales, mln lei, %

Private 89.82 80.15 84.15

Public 1.78 7.95 2.56

Mixed (without

fore-ign participation) 0.76 2.82 1.11

Foreign 3.56 4.45 5.31

Joint Ventures 4.08 4.63 6.87

Total 100 100 100

Source: Own calculations –adapted from the NBSM (2007)

A high degree of regional differentiation can be observed in the formation of SMEs‘ network. At the end of 2007, more than two thirds of the total number of SMEs (79.1 per cent) were located in the Central Region (65.9 per cent of these being in the capital Chisinau) and 13.2 per cent were in the North Region. The South region accounted for 5.1 per cent of SMEs and 2.6 per cent in the Autonomous Territorial Unit of Gagauzia (NBSM, 2007). The same source reveals that out of all SMEs in Moldova, 41.3 per cent operated at a profit, 46.7 per cent admitted losses, with the rest reporting lack of economic activity (NBSM, 2007).

From the description above, we can see that SMEs form a major part of the Moldovan economy contributing greatly to its GDP, job creation, and income generation. Still, even with all the devel-opments, the small business in Moldova is still not given proper attention (Munteanu, 2004). Poli-cies related to the property reform and the private sector have been proposed and accepted, but, at the same time, no measures were taken by the authorities to create a favorable development envi-ronment (Munteanu, 2004). Moldova can be characterized as having a poor business and invest-ment climate that constrains private sector developinvest-ment and is a major impediinvest-ment to its growth (World Bank, 2004). What will follow is a section that deals specifically with the barriers entre-preneurs face in the development of their businesses.

2.4.3 Barriers to SME growth

Labeled as one of the ―early stage transition countries‖, Moldovan entrepreneurs encounter vari-ous obstacles as a result of an inadequate legal frame and lack of institutional infrastructure for en-trepreneurship and small business development (Welter, 2006; Rutkowski, 2004; World Bank, 2004). Moreover, entrepreneurs are seen as ―cash cows‖ by the governments, as the latter arrange