VIOLENCE RISK

ASSESSMENT THROUGH A

GENDERED LENS

IS THERE A NEED TO DEVELOP

GENDER-SPECIFIC RISK ASSESSMENT TOOLS?

LENA LEVEN

Degree Project in Criminology Malmö University 30 credits Health and Society Criminology Master’s program 205 06 Malmö May 2019

2

VIOLENCE RISK

ASSESSMENT THROUGH A

GENDERED LENS

IS THERE A NEED TO DEVELOP

GENDER-SPECIFIC RISK ASSESSMENT TOOLS?

LENA LEVEN

Leven, L. Violence risk assessment through a gendered lens. Is there a need to develop gender-specific risk assessment tools? Degree project in criminology, 20

credits. Malmö University: Faculty of Health and Society, Department of

Criminology, 2019.

ABSTRACT

Violence risk assessment is important given the impact and consequences it has on offenders, victims and the public. Different tools have been developed to assess an offender’s risk. However, so far these tools are based on male theories of offending and its applicability among female offenders has been questioned by proponents of the gendered perspective. The gendered perspective argues that violence and criminal behaviour emerges based on experiences that are different between men and women. The present systematic review aims to inform about the predictive validity of current risk assessment tools among female offenders to establish whether there is a need to develop female-specific tools. 17 studies have been reviewed and evidence overall supports the gendered perspective by showing that current tools have no, or only a limited, ability to predict future behaviour among women. Some promising results have been delivered by tools that include the ‘central eight’ risk factors which indicates that some of these factors might be relevant for female risk assessment. However, consideration of qualitative and quantitative differences of risk factors should be included in risk assessment among women to improve the predictive validity. The results are discussed in the light of a feminist perspective but also give a critical view on violence risk

assessment in general. Overall, this systematic review calls for more research that focuses on gender-specific risk factors and that promotes the development of new tools.

Keywords: female offenders, gendered perspective, predictive validity, risk factors, violence risk assessment

3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor Klara Svalin for supporting me throughout the whole process of writing this thesis. She was always available for any questions I had, and her expertise was most helpful.

I also want to thank my dear friends Hulda, Leila and Sofia. The last months would have been so much harder without you. Same goes for my partner Sergio. His trust in me and my abilities, helped me to gain confidence in myself.

I would also like to thank Markus Svensson from Malmö University who helped me conducting the systematic search and thereby preventing me from and my laptop from a break down.

4

Table of contents

INTRODUCTION ... 5 Background ... 5 Ethical considerations ... 6 Aim ... 6 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ... 7Gender-responsive risk and needs ... 7

Pathways perspective ... 8

METHODOLOGY ... 9

Study selection ... 10

First selection round ... 10

Inclusion criteria ... 10

Exclusion criteria ... 11

Second selection round ... 11

RESULTS ... 12

Summary of included studies ... 12

Quality assessment of included studies ... 14

Summary of excluded studies ... 14

Risk assessment tools ... 14

Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (VRAG) ... 14

Historical-Clinical-Risk Scale-20 (HCR-20) ... 14

Psychopathy Checklist - Revised (PCL-R) ... 15

Level of Service Inventory – Revised (LSI-R) ... 15

Level of Service/Case Management Inventory (LS/CMI) ... 15

ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS ... 15

VRAG ... 15 HCR-20 ... 16 PCL-R ... 17 LSI-R ... 17 LS/CMI ... 18 DISCUSSION ... 18 Methodological discussion ... 21

Strengths and weaknesses of this review ... 23

Recommendations and future research ... 23

REFERENCES ... 25

5

INTRODUCTION

It is surprising how past and current research was and is still able to ignore raising concerns about female violence and recidivism. Even though women still

represent a smaller number of forensic patients and prison inmates worldwide compared to men, the numbers of female offenders being involved in the criminal justice system is on the rise (de Vogel, de Vries, van Kalmthout & Place, 2012). Considering this fact, more attention needs to be placed on female offending and related aspects such as violence risk assessment (VRA) in order to predict future violent behavior and recidivism. It is important to strengthen the knowledge about VRA because it informs different aspects of decision-making, such as parole board decision-making, judicial sentencing hearings and supervision management (Garcia-Mansilla, Rosenfeld & Nicholls, 2009). Therefore, it is the task of

criminologists to inform research regarding the applicability of current criminological theories for female offenders as well as research regarding the predictive performance of current VRA tools.

The discussion of gender differences regarding VRA has been shaped by two theoretical approaches (Garcia-Mansilla et al., 2009). On the one hand, the gender-neutral perspective argues that risk factors in females and males are the same and that VRA tools, that are developed and validated for male populations, can be applied to women without adaption (ibid). On the other hand, the gendered perspective argues that factors related to violence and recidivism in women are different from those in men (ibid).

The argumentation of the gender-neutral perspective is mainly based on the “central eight” factors that are argued to be applicable to both men and women (Andrews et al., 2012). The central eight consists of the “big four” and the “modest four”, with the first describing the most proximate factors related to the occurrence of delinquency and the latter being less proximate to criminal activity (ibid). The big four include the following factors: history of criminal behaviour; antisocial personality pattern; antisocial attitudes, values, beliefs and cognitive-emotional states; and antisocial associates (ibid). The modest four consists of the following factors: human interaction (family and marital relationships); school and work; leisure and recreation and substance abuse (ibid). The gendered perspective suggests, however, that these factors are not, or only partly, gender-neutral and that it does not capture all factors relevant to female delinquency (Chesney-Lind & Pasko, 2013; McKeown, 2010). For example, factors such as relationships, parental responsibilities or victimisation have a different importance for female delinquency (Reisig, Holtfreter & Morash, 2006). In the following, a summary of available meta-reviews on the matter of gender differences in VRA is given to provide an overview of evidence.

Background

Geraghty and Woodhams (2014) examined 15 studies including nine different tools. These tools are shown to have a low to moderate reliability for female offenders. Only three of the examined tools yielded satisfying values of predictive validity.

Garcia-Mansilla and colleagues (2009) show that tools based on the structured professional judgment (SPJ) approach have a better ability to predict recidivism than actuarial method-based tools among female offenders. It is discussed that the

6

validity of different tools is not clear due to contrary findings among different studies. Furthermore, it is argued that similarities in risk factors outweigh the differences, but that the differences in predictive ability of the specific risk factors need to be considered.

Holtfreter and Cupp (2007) as well as Smith, Cullen and Latessa (2009) conducted meta-reviews of the Level of Service Inventory - Revised (LSI-R; Andrews & Bonta, 1995) and their results suggest that the LSI-R has difficulties in predicting recidivism among female offenders.

Results by McKeown (2010) show that research supports the use of the Historical-Clinical-Risk-20 (HCR-20; Webster, Douglas, Eaves & Hart, 1997) and the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R; Hare, 2003) among female offenders. However, it is pointed out that further research is required to assess whether gender-specific risk factors may further inform the assessment.

Some progress has been made regarding the development of tools for female offenders. De Vogel and colleagues (2012) have developed an additional manual for female offenders when using the HCR-20. This manual includes additional guidelines regarding the assessment on all three scales. The risk factors

incorporated have shown differences between males and females and therefore considered relevant (Daly, 1992; Davidson, 2009; Reisig et al., 2006; Rettinger & Andrews, 2010; Palmer & Hollin, 2007 & Salisbury, 2009). Factors included are, for example, manipulative behaviour, problematic relationships, child-care responsibilities or self-destructive behaviours. There is some evidence that these additional guidelines have a good interrater reliability as well as a good predictive validity (De Vogel et al., 2012). However, the evidence is very limited and only based on preliminary analysis.

In sum, previous reviews and research show that the evidence regarding predictive ability of VRA tools among women is equivocal and therefore there is a need to inform further by conducting the current review.

Ethical considerations

Since the evidence regarding the applicability of VRA tools among female offenders is equivocal, ethical considerations arise. Consequences of inaccurate assessments can be long-lasting and harmful, to the individual being inaccurately assessed but also to the public. Underestimation of risk can, for example, lead to harm against other inmates or officers due to inappropriate supervision and limited service (Reisig et al., 2006). In contrast, an overestimation of risk can, for example, cause inadequate management of the offender, i.e. the offender is held under closer supervision than necessary. This, moreover, can have economic consequences by causing waste of correctional resources (Reisig et al., 2006). Therefore, the need for a clear picture on VRA among female offenders is necessary also from an ethical perspective.

Aim

The current paper reviews the evidence regarding VRA among female offenders. This systematic review aims to answer the question whether a gender-specific tool for females is necessary. The hypothesis is, based on the gendered perspective, that VRA tools based on female risk factors and criminogenic needs are vital. The question is answered by reviewing literature that examines the predictive validity

7

of existing risk assessment tools. Results are critically analysed from a feminist perspective.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

As discussed above, proponents of the gender-neutral approach argue that existing VRA tools are applicable to female offenders due to gender neutrality of risk factors incorporated in these assessment tools. In contrast to this approach, the gendered approach to risk assessment suggests that violence and criminal behaviour emerges based on experiences that are different between men and women (Garcia-Mansilla et al., 2009). Therefore, risk assessment tools should consider these differences. This approach is supported by feminist theories, arguing that existing criminological theories are inadequate in explaining female offending (Chesney-Lind, 1989).

Most of the available research on VRA is based on male offenders and the question of applicability to female offenders is becoming more prominent (e.g. Davidson, 2009; Garcia-Mansilla et al., 2009; Reisig et al., 2006). Male offending has been assumed to be the norm in research of VRA, mainly because male offending is more prominent (Davidson, 2009). However, it has been acknowledged for many years that gender is the most important predictor in criminal offending (Davidson, 2009). Even though it is acknowledged as an important predictor, gender is not considered as being involved in risk assessment and growing concerns led a small number of researchers to question this approach (Garcia-Mansilla et al., 2009).

Furthermore, it is highlighted that major criminological theories have ignored the role played by patriarchal arrangements, social roles and stereotypes (Chesney-Lind, 1989). In addition, it is argued that past research had led to a denial of existence of gendered social disadvantages and also compromised the importance of efforts to reduce these gaps (Andrews et al., 2012). The nature of violence offers another important difference. Females tend to target children, elders and intimate partners whereas male violence occurs against women (Garcia-Mansilla et al., 2009). Furthermore, female aggression is argued to be indirect as opposed to the direct form of male aggression (ibid). Therefore, concerns are raised

whether the same instruments can be used to predict crime and violence which are in itself completely different between male and females.

Gender-responsive risk and needs

In addition to the central eight, female-specific risk factors may influence the reliability and validity of VRA. Van Voorhis, Wright, Salisbury and Bauman (2010) raise seven different factors that might be relevant to risk assessment: First, victimisation and abuse are found to be related to criminal behaviour. This relationship is often influenced by trauma or substance abuse following

victimisation and thereby increasing the risk of criminal conduct.

Second, relationship problems are related to female delinquency. It is evident that women identify themselves through their relationships with others. Therefore,

8

these relationships, if troubled, may increase the likelihood of criminal behaviour and violence.

Third, mental health is shown to be a differentiating factor between male and female criminality. Females show more problems of depression, anxiety and self-injurious behaviour, which have been shown to be strong predictors of recidivism in female offenders. There are two problems regarding mental illness and current VRA: first, historical assessment of mental health diagnoses is flawed because offenders often may not be officially diagnosed and therefore tend to be underreported. It is hypothesised that behavioural measures may be more

appropriate to be incorporated in VRA. Second, the relationship between factors associated with recidivism and mental health is unclear. Some forms of mental illnesses are linked to reoffending while others are not. However, current tools combine mental disorders into one category and therefore may not capture the interrelatedness appropriately.

The fourth gender-responsive factor suggested is substance abuse. Even though related to both male and female offending and included in some available instruments, it is hypothesised that substance abuse has unique effects among women, especially due to its relationship with other risk factors such as mental illness and victimisation. This is supported by of findings of Andrews and colleagues (2012) who show that substance abuse is more strongly linked with recidivism in female offenders than in male offenders.

As a fifth factor self-efficacy is considered important when conducting risk assessment. On the one hand, this factor can act as a protective factor, women who have high levels of self-efficacy and self-confidence may experience a reduced risk of recidivism. On the other hand, low levels can be related to increased risk of recidivism.

Sixth, poverty is a factor that can influence females’ risk for violence and

recidivism. Women are more often involved in financial problems due to limited education, alcohol or drug problems and child-care responsibilities. This factor is included within the central eight, but it is argued that poverty affects women differently than men.

Lastly, parental issues are relevant to female recidivism. Having parental responsibilities can be both a risk factor (having financial means to support the child by illegal activities) and a protective factor (staying away from crime in order to execute parental tasks). Still, women are more involved in these responsibilities compared to men.

In conclusion, the seven factors presented give a good foundation to question the gender neutrality of current tools and suggest factors that might be relevant in addition to the central eight. Unfortunately, the evidence is scarce which calls for more research attention into gender-responsive needs and risks.

Pathways perspective

In addition to differences in risk and need factors, evidence shows that pathways to criminal behaviour for female offenders are different from male pathways (e.g. Andersson, 2013; Daly, 1992; Davidson, 2009). This is consistent with

9

2003) and general strain theory (Broidy & Agnew, 1997). Women’s pathways into crime include a history of drug-related offenses, fragmented family history, physical and/or sexual abuse, mental health problems and economic disadvantages (Davidson, 2009).

Daly (1992) has identified different pathways within female offenders: One pathway is called “street women” and includes females who run away from home, start using drugs and use illegal ways to financially support themselves such as prostitution, drug dealing or theft. Another pathway is called “drug-connected pathway”. Women in this category are involved in using, manufacturing and/or distributing drugs in the context of their relationships. In contrast to street women, these women have an earlier onset of drug use and are less often arrested. Two other pathways are related to history of abuse and/or neglect. “Harmed and

harming women” have a history of chaotic living conditions and have been abused within the family context. One could describe them as “difficult children”,

meaning they are often involved in antisocial behaviours in school and are in contact with the juvenile justice system. Another pathway is called “battered women”, which includes women with a history of abuse, however, these have been abused by their partners. The last pathway does not incorporate gendered factors of criminal behaviour (Reisig et al., 2006). Daly (1992) called this

pathway “other” and includes women that are “economically motivated” (Morash & Shram, 2002; p.37). These women commit crime in order to increase their financial means, however, they do not show history of abuse, drug addiction or violence (Daly, 1992). Some women commit crime in order to cope with poverty while others do it to increase their wealth (Reisig et al., 2006). Just as the

women’s pathways into criminal offending are different from men’s pathways, so are the pathways to desistance or persistence (Laub & Sampson, 2003). There is evidence that similar factors concerning abuse, criminal partners, drugs etc. are linked with recidivism in females (Benda, 2005). In conclusion, available theories and research lead to the fair point of questioning gender neutrality of VRA tools.

METHODOLOGY

A systematic review of the literature was conducted to identify quantitative studies that explore the predictive utility of VRA tools for female offenders to answer the question whether a specialised tool for female offenders is needed. Predictive validity is commonly used to assess the accuracy of VRA tools and gives a measure of a tool’s ability to correctly identify the likelihood of violence or recidivism (Singh, 2013). The ROC analysis produces a measure of predictive validity which is called Area Under the Curve (AUC) and gives a global

discrimination index. As mentioned by Geragthy and Woodhams (2015), an AUC of 0.00 represents a perfect negative prediction, an AUC of 0.50 is equal with a prediction at chance level and an AUC of 1.0 shows perfect positive association. Generally, an AUC that is larger than 0.70 is considered as moderate predictive ability and larger than 0.75 as good predictive ability (ibid). Furthermore, the correlation coefficient (r) is commonly used and represents the direction and strength of an association between two different variables. A value of -1.0 indicates a perfect negative association and a value of +1.0 indicates a perfect

10

positive association. Generally, a value higher than 0.30 represents a moderate relationship and values larger than 0.50 indicate a strong relationship (ibid). An initial scoping search was conducted in January and February 2019 to

determine the need for a systematic review. The database Libsearch was used as it contains a broad range of multiple databases. Since it scans a broad range of databases, Libsearch, however was not used for the systematic search as it cannot be identified easily which database a specific article is retrieved from. The

scoping search identified the above-mentioned meta-reviews but did not find studies that explored the same hypothesis.

Study selection

Literature searches were conducted in March 2019. Ten different electronic databases were chosen because they include literature within the field of social sciences. They were searched for published articles that were accessible through Malmö University’s library. These databases were tested for their suitability. It was found that six were not useful because either their search functions did not enable a proper exclusion option, or searches yielded zero articles within the field of interest. The searches were carried out with PsychInfo, Criminology Database, Scopus and Academic Search Elite. The search term ‘gender differences’ was changed to ‘human sex differences’ based on the thesaurus function. The search on all databases were based on the following search terms: (quotation marks need to be used when two words should appear only together)

1. “risk assessment” OR recidivism OR re-offending

2. “female offenders” OR “female offender” OR “women offenders” OR “human sex differences”

First selection round

The first selection round included screening of title and abstract based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria (see below). Some criteria could be applied when entering keywords into the search bar and some criteria have been applied after starting the search. Criteria applied before results showed, were the age range, peer-reviewed (if possible) and search in abstract. The different databases gave different options of excluding or including certain document types, subjects, methodologies or publication titles after results appear. These options are based on the results in each database, meaning that the options vary. In some cases, reading abstract and title did not enable exclusion or inclusion of the article. These ones were included in the second round for full-text reading.

In order to increase the comprehensiveness of the search, reference lists of key papers in the area were searched for other relevant articles to be included in the final selection (see appendix, table 8). Articles that have been found via

Libsearch, but did not appear through the systematic search, were also included in order to create a holistic picture of the available evidence. For transparency, the appendix includes a more detailed description of the searches (table 7) as well as all hits per database with reasons for exclusion (table 8).

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) adult offenders (>18 years of age), (2) female or mixed gender samples, (3) include a measure of predictive validity, (4) articles published in English, (4) quantitative methodology, (4) peer-reviewed, (5)

11

published between 2000 and 2019; only studies after 2000 were considered relevant because all available actuarial or SPJ tools were developed in the late 1990s or 2000s (Andersson, 2015), (6) commonly used risk assessment tools (more than one study found that examines a tool).

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded based on: (1) using a male sample, (2) review or theoretical article, (3) examine a sample of sex offender (4) examine intimate partner

violence, domestic violence or related areas, (5) examine treatment or

rehabilitation program, (6) sample of civil psychiatric patients, (7) examine risk of victimisation, (8) related to drug abuse or addiction, (9) related to medicine and health risks.

Exclusion criteria one was chosen because having studies that are purely based on male offenders cannot yield results regarding the research question. Criteria two was chosen because this study aims at reviewing quantitative research that has been done in the field. Criteria three and four were chosen since these females involved in sexual and domestic violence are very rare (Garcia-Mansilla et al., 2009). The examination of a treatment and rehabilitation program was excluded because it would not answer the research question. Exclusion criteria six was applied because the target group are offenders. Exclusion criteria eight was applied because studies specifically examining drug abuse and addiction were not considered relevant for the current research question. Lastly, criteria nine was chosen since it is not relevant to the hypothesis regarding VRA.

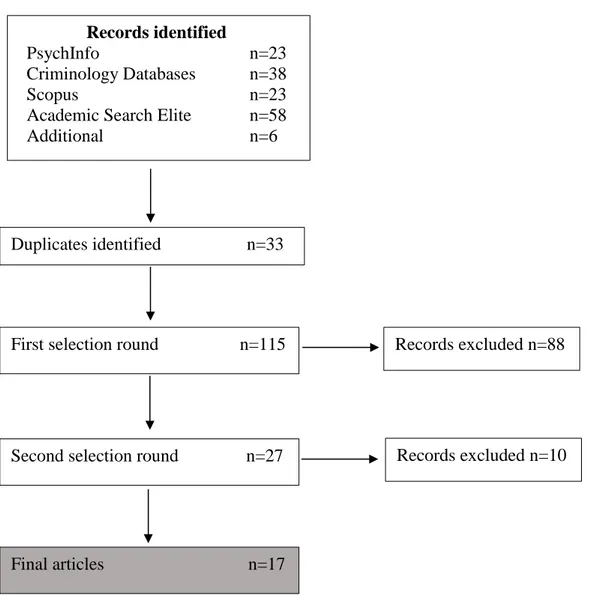

Most of the articles were identified through the systemic search (n=142) and the minority was found via the first random search or via the key paper search (n=6). 58 articles were found via Academic Search Elite, 23 articles via Scopus, 38 results yielded the search in the Criminology Database and 23 papers were found via PsychInfo. 33 duplicates had been identified in total, which left 116 articles to be screened in the first selection round. Of these 116 articles, 88 had been

excluded according to the criteria, which leaves 27 articles for the second selection round (Figure 1).

Second selection round

The same criteria as used in the first selection round were applied but this time within the whole text. In total, ten articles were excluded with reason, which leaves 17 studies for the systematic review (Figure 1). Two articles were excluded because they were either a review or a meta-analysis and four articles have been excluded since they did not evaluate predictive ability of tools. Both criteria have been applied in the first screening, but it only became apparent when reading the full text that these six articles did not fit the criteria. Additionally, four articles have been excluded because risk is assessed via self-reports. It was decided to exclude these ones because meaningful risk assessment on which decisions regarding parole or treatment can be made, should be based on assessment by trained professionals (Hare, 1998).

12

RESULTS

Summary of included studies

In total, 17 studies are included in this review and detailed information on study characteristics can be found in Table 1. The studies are based on either

prospective or retrospective designs. Prospective designs include an assessment of risk based on interviews and a follow-up period, whereas retrospective designs rely on an assessment of risk based on reports previously conducted. In total, five different tools are included in the review: HCR-20, VRAG, LSI-R, LS/CMI, PCL-R (for further explanation see below). Some studies assess one tool while others assess multiple. The samples are based on different populations, such as forensic patients, prison inmates, offenders serving a community sentence or

paroles/probationers. There is variability in the outcomes measure between the studies. Some studies assess recidivism by following on official records for different kinds of violations or crimes, others rely on self-reported violations or crimes and some do not assess recidivism but violence, either via self-reports or official records.

Records identified

PsychInfo n=23

Criminology Databases n=38

Scopus n=23

Academic Search Elite n=58

Additional n=6

Duplicates identified n=33

First selection round n=115 Records excluded n=88

Second selection round n=27 Records excluded n=10

Final articles n=17

13 Ta b le 1 . S u mma ry o f in clu d ed s tu d ies Stu d y Desig n Sa m p le Size T o o l Ou tco m e m ea su re C o id et al. , (2 0 0 9 ) P ro sp ec tiv e fo llo w -u p , ass es sm en t b ef o re relea se , av er ag e fo llo w p er io d 1 .9 7 y ea rs R elea sed p ris o n er s/p ar o lees 321 P C L -R , H C R -2 0 , VR A G Of ficial rec o rd o f an y r eo ff e n se o r b rea ch o f p ar o le o r p ro b atio n co n d itio n s De Vo g el et al. , (2 0 0 5 ) Mix ed d esig n : r etr o sp ec tiv e a n d p ro sp ec tiv e, av er ag e fo llo w p er io d r etr o sp ectiv e 7 6 .4 m o n th s; p ro sp ec tiv e 1 0 .2 m o n th s Fo ren sic p atien ts 42 HC R -2 0 , P C L -R Of ficial rec o rd o f an y v io len t reo ff e n se an d in p atien t v io le n ce D y c k et al. , (2 0 1 8 ) R etr o sp ec tiv e as ses sm en t b ase d o n s ec o n d ar y d ata , av er ag e fo llo w p er io d : 3 .4 2 y ea rs C o m m u n it y s u p er v is ed o ff e n d er s 35 L S/ C MI Of ficial rec o rd o f an y n e w ch a rg e E is en b ar th et al. , (2 0 1 2 ) R etr o sp ec tiv e as ses sm en t b ase d o n s ec o n d ar y d ata , fo llo w p er io d m a x . 8 y ea rs Fo ren sic p atien ts 80 P C L -R , VR A G, H C R -20 Of ficial rec o rd o f an y r ec o n v ictio n Go rd o n et al. , (2 0 1 5 ) R etr o sp ec tiv e as ses sm en t b ase d o n s ec o n d ar y d ata ; f o llo w p er io d : 1 2 m o n th s C o m m u n it y s u p er v is ed o ff e n d er s 113 L S/ C MI Of ficial rec o rd o f an y r eo ff e n se Gr ee n et al. , (2 0 1 6 ) R etr o sp ec tiv e as ses sm en t b ase d o n s ec o n d ar y d ata , av er ag e fo llo w p er io d : 1 5 .5 m o n th s Fo ren sic p atien ts 24 HC R -20 Do cu m e n ted ac tu a l, atte m p ted o r th rea ten ed in flictio n o f h ar m to an o th er p er so n o r p ro p er ty Hasti n g s et al. , (2 0 1 1 ) P ro sp ec tiv e fo llo w -u p , ass es sm en t b ef o re relea se , fo llo w p er io d : 1 y ea r P ris o n in m ates a n d r elea sed p ris o n er s 145 VR A G in st itu tio n al m is co n d u ct & o n e -y ea r p o st -r elea se rec id iv is m : sel f-rep o rted ar res ts an d cr im in al b eh av io u r Ho ltf reter et al. , (2 0 0 4 ) P ro sp ec tiv e fo llo w -u p , ass es sm en t b ef o re relea se , fo llo w p er io d : 6 m o n th s R elea sed p ris o n er s/p ar o lees 134 L SI -R Self -r ep o rt o f rea rr est o r v io latio n o f p ar o le o r p ro b atio n co n d itio n s Ma n ch a k et al. , (2 0 0 9 ) R etr o sp ec tiv e as ses sm en t b ase d o n s ec o n d ar y d ata , fo llo w u p p er io d : 1 2 m o n th s R elea sed p ris o n er s/P ar o lees 1105 L SI -R Of ficial rec o rd o f co n v ictio n f o r an y n e w o ff e n se P alm er et al. , (2 0 0 7 ) Mix ed d esig n , as sess m e n t v ia sec o n d ar y d ata an d in ter v ie w s b e fo re relea se an d f o llo w -up , fo llo w p er io d : 2 .5 y ea rs R elea sed p ris o n er s/p ar o lees 96 L SI -R Of ficial rec o rd o f rec o n v ictio n f o r an y cr im e R eisi g et al. , (2 0 0 6 ) P ro sp ec tiv e fo llo w -u p , ass es sm en t b ef o re relea se , fo llo w p er io d : 1 8 m o n th s C o m m u n it y s u p er v is ed o ff e n d er s 402 L SI -R Of ficial rec o rd o f v io latio n o f su p er v is io n co n d itio n s a n d r ea rr est/ rec o n v ictio n R etti n g er et al. , (2 0 1 0 ) R etr o sp ec tiv e as ses sm en t b ase d o n s ec o n d ar y d ata , av er ag e fo llo w p er io d : 5 7 m o n th s R elea sed p ris o n i n m a tes a n d co m m u n it y s u p er v is ed o ff e n d er s 531 L S/ C MI Of ficial rec o rd o f g en er al a n d v io len t r ec id iv is m Salis b u ry et al. , (2 0 0 9 ) P ro sp ec tiv e fo llo w -u p , ass es sm en t b ef o re relea se , fo llo w p er io d : 6 m o n th s d u ri n g in ca rce ratio n , 4 4 .2 m o n th s af ter r elea se R elea sed p ris o n er s 134 L SI -R Of ficial rec o rd o f an y n e w cr im es a n d tech n ical p ar o le v io latio n s Sch aa p et al. , (2 0 0 9 ) R etr o sp ec tiv e as ses sm en t b ase d o n s ec o n d ar y d ata , fo llo w p er io d u n k n o w n Fo ren sic p atien ts 45 HC R -2 0 , P C L -R Of ficial rec o rd o f an y r ec o n v ictio n Vo se et al. , (2 0 0 9 ) P ro sp ec tiv e fo llo w -u p , ass es sm en t b ef o re relea se , av er ag e fo llo w p er io d : 4 ,7 y ea rs R elea sed p ris o n er s/p ar o lees 401 L SI -R Of ficial rec o rd o f an y n e w m is d e m ea n o u r o r felo n y co n v ictio n W ar ren et al. , (2 0 1 7 ) R etr o sp ec tiv e as ses sm en t b ase d o n s ec o n d ar y d ata , fo llo w p er io d u n k n o w n P ris o n in m ates 183 HC R -2 0 , P C L -R, VR A G T h rea ten ed , p h y sical o r sex u al p ris o n v io len ce : self -r ep o rt a n d d o cu m e n ted in fr ac tio n s W eiz m an n -He n eli u s et al. , (2 0 1 5 ) P ro sp ec tiv e fo llo w -u p , ass es sm en t b ef o re relea se , av er ag e fo llo w p er io d : 8 y ea rs R elea sed p ris o n er s/r elea sed fo ren sic p atie n ts 48 P C L -R Of ficial rec o rd o f v io len t r ec id iv is m

14

Quality assessment of included studies

All studies have been assessed regarding their quality. The quality of studies varies due to different methodological designs and sample size. Some of the studies conducted their assessment based on secondary data and did not interview the participants which is a restriction which needs to be taken into consideration when evaluating the evidence. This is a restriction because the original evaluators of the available information are likely to have different approaches to assessment and characterisation of relevant information (Green et al., 2016). Furthermore, some studies only have a limited time of follow-up, which can compromise the quality. Having a limited follow-up period may increase the chances of missing cases of recidivism or violence after the timeframe (Coid et al., 2009). Another common issue is the sample size, especially in prospective studies. Sample sizes are smaller due to the limited number of female offenders. In retrospective studies, the problem is less evident since assessments of years back can be obtained. However, due to the sacrceness of available evidence regarding female samples, no studies have been excluded due to quality limitations.

Summary of excluded studies

As discussed above, different exclusion criteria have been applied in order to limit the evidence to studies that can answer the research question at hand. In the appendix, a detailed list of all articles can be found with a reason for exclusion where applicable.

In sum, the main reasons for exclusion were that studies did not examine VRA tools at all or that they did not examine commonly used tools. Another common reason for exclusion is the examination of treatment or prevention programs rather than VRA tools. Additionally, studies were excluded because the methodology did not match, meaning they were review articles, meta-analysis or qualitative studies. Lastly, some studies were excluded because results were not discussed separately by gender.

Risk assessment tools

In the following section, the risk assessment tools which are central to this review are briefly explained. VRA instruments can be categorised within two different groups – actuarial assessments or structured professional judgment (SPJ). Actuarial assessments are based on formal decision algorithms or weighted combinations of variables that are purely based on empirical findings (Garcia-Mansilla et al., 2006). The SPJ method incorporates both variables based on empirical findings and clinical judgment. The tools within this approach give guidelines for the assessment but the final risk judgment is based on the

clinician’s expertise how to weigh the different variables (Garcilla-Mansilla et al., 2006).

Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (VRAG)

The VRAG is an actuarial risk assessment tool which consists of 12 items that are developed based on male forensic patients (Quinsey, Harris, Rice & Cormier, 2006). The items assess the index offense, psychopathy, alcohol use and previous non-violent criminal behaviour (Quinsey et al., 2006).

Historical-Clinical-Risk Scale-20 (HCR-20)

This scale belongs to the SPJ method and is designed to guide decisions about violence risk among different populations, such as civil psychiatric patients,

15

forensic patients and criminal justice population (Webster et al., 1997). The tool consists of 20 items: ten items reflecting historical factors, five items reflecting clinical factors and five items for risk management factors (Webster et al., 1997).

Psychopathy Checklist - Revised (PCL-R)

The PCL-R is an actuarial tool and includes 20 items assessing a two-factor structure of the psychopathy construct (Hare, 2003). Factor one contains items regarding affective and interpersonal factors, whereas factor two assesses antisocial and unstable lifestyle, including criminal behaviour, impulsivity and irresponsibility (Hare, 2003). Originally, the PCL-R was not designed as a VRA instrument. However, due to the association of psychopathy and violence, it is commonly used as such (Schaap, Lammers & de Vogel, 2009).

Level of Service Inventory – Revised (LSI-R)

The LSI-R is based on the central eight (Andrews & Bonta, 1995) and includes 10 subscales with a total of 54, mostly dynamic, items: 1) Criminal history, 2)

education/employment, 3) financial situation, 4) family/martial relationship, 5) accommodation, 6) leisure and recreation, 7) companions, 8) alcohol and drug use, 9) emotional/personal, and 10) attitudes orientations (Andrews & Bonta, 1995). This tool cannot be placed in either the actuarial or SPJ categories but is a partially structured approach that needs to be placed between the two categories (Skeem & Monahan, 2011).

Level of Service/Case Management Inventory (LS/CMI)

The LS/CMI belongs to the category of actuarial tools and consists of eight subscales (the central eight) with different number of items (Andrews, Bonta & Wormith, 2004). The LS/CMI is the successor of the LSI-R and therefore shows some similarities. The subscales assess following areas: criminal history,

education/employment, family/marital, leisure/recreation, companions,

alcohol/drug problem, pro-criminal attitude/orientation and antisocial patterns. (Andrews et al., 2004).

ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS

In the following, a general overview of all reviews is given. Thereafter, a more detailed discussion of the available evidence including the values of predictive ability is presented separately for each risk assessment tool. In support of the gendered perspective, evidence of 12 studies shows that current risk assessment tools are not satisfactory in predicting violence and recidivism in female

populations. This is based on the fact that the measures of predictive validity either do not reach values higher than the recommended threshold (AUC< 0.7; r< 0.3) or given values are not significant, which means that the findings cannot be generalised. Support for the gender-blind perspective comes from nine studies, including four studies that also deliver results contradictory to the gender-blind perspective. These studies show values over the recommended threshold that are also significant.

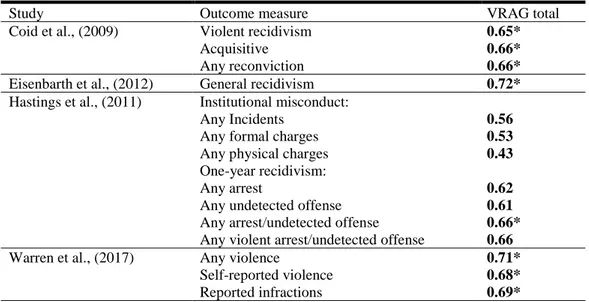

VRAG

Four studies evaluate the predictive ability of the VRAG by conducting a ROC analysis but having different outcome measures (see Table 2). In total, two studies

16

deliver some evidence that the VRAG can be used among female offenders (Eisenbarth et al., 2012; Warren et al., 2017). However, results by Warren and colleagues (2017) show limited predictive validity, because the recommended threshold is reached only when self-reported violence and reported infractions are analysed together, but not separately. The other reviewed evidence reports low and/or non-significant levels of predictive accuracy (Coid et al., 2009; Hastings et al., 2011).

HCR-20

In total, six studies evaluate the predictive validity of the HCR-20 (table 3). Only two of these studies assess the HCR-20 including the final risk judgment (De Vogel & de Ruiter, 2005; Schaap et al., 2009). One of these studies finds a good predictive validity of the HCR-20 as an SPJ method (including final risk

judgement) but not as an actuarial tool (excluding final risk judgment) (De Vogel & de Ruiter, 2005) and one does not report significant results for any method (Schaap et al., 2009). Additionally, two studies show that the HCR-20 as an actuarial tool is not able to predict general recidivism or violence (Eisenbarth, 2012; Green et al., 2016). Two studies indicate that the total scale and the historical subscale can predict violent recidivism (Coid et al., 2009) and violent behaviour (self-reported and official combined) (Warren et al., 2017).

Table 2. Predictive values VRAG

Study Outcome measure VRAG total

Coid et al., (2009) Violent recidivism 0.65*

Acquisitive 0.66*

Any reconviction 0.66*

Eisenbarth et al., (2012) General recidivism 0.72*

Hastings et al., (2011) Institutional misconduct:

Any Incidents Any formal charges Any physical charges

0.56 0.53 0.43

One-year recidivism: Any arrest

Any undetected offense Any arrest/undetected offense Any violent arrest/undetected offense

0.62 0.61 0.66* 0.66

Warren et al., (2017) Any violence 0.71*

Self-reported violence 0.68*

Reported infractions 0.69*

17 PCL-R

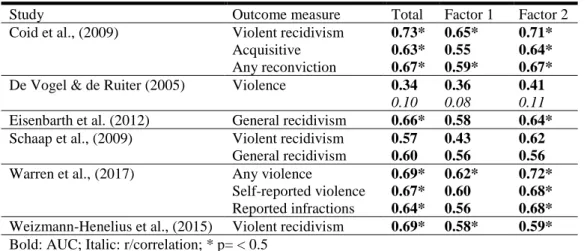

In total, six of the reviewed studies include an analysis of the PCL-R. Three studies deliver some evidence in favour of the PCL-R (Coid et al., 2009; Warren et al., 2017; see table 4). In more detail, Coid and colleagues (2009) report that the PCL-R total score and factor 2 can significantly and satisfyingly predict violent recidivism, but not acquisitive crimes or any reconviction. Furthermore, Warren and colleagues (2017) support that factor 2 can predict violence. Additionally, results by Weizmann-Henelius and colleagues (2015) show that the PCL-R significantly predicts violent recidivism for female offenders. Nevertheless, the AUC values just lie below the recommended threshold of 0.70. The same is evident from results shown by Eisenbarth and colleagues (2012). Values are significant for predicting general recidivism (PCL-R total and Factor 2), but do not reach the recommended threshold. Two studies (de Vogel & de Ruiter, 2005; Schaap et al., 2009) do not deliver evidence that the PCL-R, or its underlying factors, can predict future behaviour.

Table 4. Predictive values PCL-R

Study Outcome measure Total Factor 1 Factor 2

Coid et al., (2009) Violent recidivism 0.73* 0.65* 0.71*

Acquisitive 0.63* 0.55 0.64*

Any reconviction 0.67* 0.59* 0.67*

De Vogel & de Ruiter (2005) Violence 0.34

0.10

0.36 0.08

0.41 0.11

Eisenbarth et al. (2012) General recidivism 0.66* 0.58 0.64*

Schaap et al., (2009) Violent recidivism 0.57 0.43 0.62

General recidivism 0.60 0.56 0.56

Warren et al., (2017) Any violence 0.69* 0.62* 0.72*

Self-reported violence 0.67* 0.60 0.68*

Reported infractions 0.64* 0.56 0.68*

Weizmann-Henelius et al., (2015) Violent recidivism 0.69* 0.58* 0.59*

Bold: AUC; Italic: r/correlation; * p= < 0.5 LSI-R

In total, six studies evaluate the predictive ability of the LSI-R total (see table 5). The subcomponents of the LSI-R are not presented because not all reviewed studies conducted a separate analysis. Two studies indicate good predictive validity (Manchak et al., 2009; Palmer & Hollin, 2007). Most of the other studies

Table 3. Predictive values HCR-20

Study Outcome measure Total H C R FRJ

Coid et al., (2009) Violent recidivism 0.70* 0.73* 0.69* 0.59

Acquisitive 0.61* 0.62* 0.60* 0.55

Any reconviction 0.67* 0.67* 0.67* 0.59*

De Vogel & de Ruiter (2005) Violence 0.59 0.20 0.63 0.22 0.61 0.17 0.52 0.07 0.86*

Eisenbarth et al. (2012) General recidivism 0.59 0.61 0.56 0.56

Green et al., (2016) Violence 0.27 0.28 0.31 -0.08

Schaap et al., (2009) Violent recidivism 0.54 0.68 0.42 0.47 0.65

General recidivism 0.54 0.58 0.41 0.56 0.58

Warren et al., (2017) Any violence 0.74* 0.74* 0.67* 0.63*

Self-reported violence 0.68* 0.68* 0.62* 0.63*

Reported infractions 0.66* 0.64* 0.66* 0.58

18

show significant results but do not reach the recommended threshold (Holtfreter et al., 2004; Reisig et al., 2006; Salisbury et al., 2009; Vose et al., 2009).

LS/CMI

In total, three of the reviewed studies evaluate the predictive ability of the LS/CMI (Dyck et al., 2018; Gordon et al., 2006; Rettinger & Andrews, 2010). The subcomponents of the LS/CMI are not reported because not all studies conducted a separate analysis. First, Dyck and colleagues (2018) show that the LS/CMI has a good ability to predict general recidivism among female offenders. Second, results by Gordon and colleagues (2006) display that the LS/CMI has no ability to predict reoffending by showing a non-significant correlation as well as a non-significant AUC value. Lastly, Rettinger and Andrews (2010) present

significant correlations between the LS/CMI and general as well as violent recidivism.

Table 6. Predictive values LS/CMI

Study Outcome measure LS/CMI Total

Dyck et al., (2018) General recidivism 0.94*

Gordon et al., (2006) Reoffending 0.10

0.58

Rettinger & Andrews (2010) General recidivism 0.63*

Violent recidivism 0.44*

Bold: AUC; Italic: r/correlation; * p= < 0.5

DISCUSSION

Research questioning the gender-neutrality of current VRA tools has become more popular during the last decade. More specifically, it has been questioned whether VRA tools that have been developed based on male offenders can be used among female offenders without adaption (e.g. Garcia-Mansilla et al., 2009). This review systematically evaluates quantitative evidence that examines the predictive validity of current VRA tools among female offenders to answer the current hypothesis. Overall, findings show that current VRA tools have limitations when predicting future behaviour among female offenders. In the following, a

Table 5. Predictive values LSI-R

Study Outcome measure LSI-R Total

Holtfreter et al., (2004) Rearrest 0.16

Violation of rules 0.17*

Manchak et al., (2009) Recidivism 1 year

Recidivism 3 years

0.77* 0.23 0.34

Palmer & Hollin (2007) Reconviction 0.53*

Reisig et al., (2006) Recidivism full sample

Recidivism non-gendered pathway Recidivism gendered pathway Recidivism Unclassified

0.07 0.29* -0.14 0.49*

Salisbury et al., (2009) Serious prison misconduct 0.12*

Technical violation 0.18*

Rearrest Non-significant, not reported

Any failure post-release 0.21*

Vose et al., (2009) Recidivism after measurement 1 0.11*

Recidivism after measurement 2 0.20*

19

discussion takes place that is based on different groups and outcomes measures. This is done to show in more detail which tools might be useful regarding different populations and outcomes.

The VRAG has been shown to be partly useful when predicting any recidivism among forensic patients (Eisenbarth et al., 2012; Warren et al., 2017).However, using the VRAG among prisoners and parolees to predict prison misconduct, recidivism or violation of parole rules, is not recommended. Therefore, the VRAG has limited applicability but might be useful as an assisting guideline when

developing new, female-specific tools, especially among forensic patients. Furthermore, the HCR-20 does not prove to be useful among either forensic patients nor prisoners or parolees. Furthermore, it is not able to predict prison misconduct, recidivism or violation of parole rules when used as an actuarial tool. The total scale as well as the historical scale are shown to predict violent

recidivism (Coid et al., 2009; Warren et al., 2017). Whether the HCR-20 can predict recidivism when used as an SPJ tool is not clear due to mixed and scarce evidence (De Vogel & de Ruiter, 2005; Schaap et al., 2009). The mixed findings might be due to differences in assessor’s knowledge (Green et al., 2016). It is evident that the weighting process, i.e. determining which factors are most

important for the prediction of risk, has an influence on the reliability of the VRA. There seems to be a tendency of clinicians to underestimate the risk posed by female offenders (Green et al., 2016), which implies that an independent

evaluation might not be advised among female offenders. In turn, the goal should be to find a standardised way of balancing the items differently for females and males.

The results, moreover, do not provide confidence regarding the use of the PCL-R among prisoners to predict violence; or among forensic patients to predict

recidivism or violence. Its usefulness has been limited to the prediction of violent recidivism among parolees. Surprisingly, in all reviewed studies factor 2 of the PCL-R shows higher, yet mostly non-significant, levels of predictive ability. This suggests that factors related to antisocial lifestyle, such as impulsivity and

criminal history, are more important when predicting future behaviour among female offenders compared to affective and interpersonal factors. This is in contrast with results reported by McKeown (2010) that show factor 1 to be the stronger predictor of future behaviour. Therefore, the construct of psychopathy and its predictive usefulness among women needs further attention and supports the notion of developing new tools for female offenders.

Some usefulness among female offenders is acknowledged when using the LSI-R. It appears that it might be useful when predicting one-year recidivism among released prisoner (Manchak et al., 2009; Palmer & Hollin, 2007). Since the LSI-R includes some risk factors that are considered relevant for females, e.g. financial situation, family/martial relationships and education, the results are not surprising (Andrews & Bonta, 1995). However, evidence is mixed and using the LSI-R among female prisoners could be misguided when practitioners rely heavily on results delivered by the LSI-R. It is argued that the LSI-R does not fully capture the diversity of circumstances of female offenders (Holtfreter & Cupp, 2007). These results might be improved by further emphasising gender-specific risk factors as well as criminogenic needs. Furthermore, results can be improved if qualitative and quantitative differences among risk factors, such as financial

20

situation, relationships and education, are acknowledged and weighted differently among females than among males.

The LS/CMI, which is an updated version of the LSI-R, also shows some usefulness when predicting recidivism (violent and general) among community-supervised offenders. Results are mixed which leads to the conclusion that the LS/CMI should be used with great caution. It is argued, again, that the risk factors that provide the foundations for the LS/CMI are partly gender-neutral and which leads to the usefulness of the LS/CMI among female offenders. However, additional risk factors and a different weighting of them might deliver more consistent results.

Overall, the presented evidence questions the gender neutrality of current risk assessment tools regarding different samples as well as different outcome

measures. From the analysis of predictive validity of current VRA tools, it can be concluded that current assessments are not, or less valid for use among female offenders and establishes the need to either develop new tools or adapt current ones.

The LS/CMI and the LSI-R have shown some usefulness and it is argued that this might be a good basis for the development of risk assessment tools for female offenders. Both tools are based on the central eight risk factors which indicates that some of these factors might be gender neutral. A consideration of the underlying theory and research has indicated that there are differences in risk factors as well as pathways into crime that can improve the predictive ability among female offenders. As discussed, female offenders are more heavily influenced by victimisation, trauma, mental health issues, drug problems and economic disadvantages (e.g. Van Voorhis et al., 2010). These factors should not be neglected and provide a good starting point to develop female specific VRA tools.

In addition to the LSI-R and LS/CMI, some evidence has been found in support of the VRAG, this is however, based on limited literature. All three tools, that show some promising results in the current review, are (partly) actuarial tools, i.e. they are based on formal decision algorithms or weighted combinations of variables rather than using professional judgment. This is in contrast with past studies that show that the final risk judgment works better than actuarial tools among women (Garcia-Mansilla et al., 2009; McKeown, 2010). This is neither rejected nor supported by the current findings. A comparison between actuarial tools and SPJ tools is difficult due to the small amount of evidence regarding the SPJ approach. As argued before, a differential importance between certain risk factors is

acknowledged which could be executed by using a final risk judgment. However, this would be a rather subjective approach since every evaluator would include items that one finds relevant and important which is influenced by the assessor’s knowledge and experience (Green et al., 2016).

To set the results into a broader context, a comparison with results from male samples will now be briefly discussed. If results indicate that current VRA tools do not reliably predict recidivism/violence among men, then this would have implications for the current argumentation as other factors might be important apart from gender-specific risk factors. Some of the reviewed literature includes male participants and the results show mixed findings. It is shown that the

HCR-21

20, as well as the historical and clinical subscale can significantly predict future behaviour among male offenders (Coid et al., 2009; Green et al., 2016; Warren et al., 2018). However, there is also some evidence that the HCR-20 predicts future behaviour better for females than for males (Coid et al., 2009). A meta-analysis by Singh, Grann and Fazel (2011) indicates that the HCR-20 shows good predictive ability among male offenders, which supports the evidence at hand. The meta-analysis by Singh and colleagues (2011) further indicates that the VRAG reliably predicts future behaviour among male offenders which is also supported by the findings reviewed (Coid et al., 2009; Hastings et al., 2011; Warren et al., 2018). The results regarding the PCL-R are mixed. The meta-analysis reports rather low levels of predictive validity for males (Singh et al., 2011), which is supported by Coid and colleagues (2009) who report higher levels of predictive validity for females than for males. However, Warren and colleagues (2018) report good predictive validity of the PCL-R for male offenders. Regarding the LSI-R the meta-analysis by Singh and colleagues (2011) reports rather low levels for the among male offenders. None of the reviewed studies discuss the LSI-R among female offenders. The LS/CMI is not included in the meta-analysis and reviewed findings indicate mixed evidence (Dyck et al., 2018; Gordon et al., 2006). In conclusion, the evidence regarding the use of current VRA on male offenders is mixed as well but does show some promising directions. Even though the

predictive ability of current VRA tools among men is unclear as well, this should not disregard the findings of the current review. Improvements might be possible when incorporating less gender-neutral but more gender-specific risk factors for both male and females.

Most of the reviewed evidence is in favour of the current hypothesis regarding an adaptation of existing tools or even the development of new tools. From an ethical and academic standpoint, one should not be satisfied with tools that are only partly supported for the use among female offenders but should demand the development of new tools based on female risk factors.

As discussed above, there has been some progress in that direction since De Vogel and colleagues (2012) have introduced the additional manual for the HCR-20 for female offenders. Some of these promising results indicate that it might improve the predictive ability when female-specific risk factors, e.g. victimisation, economic disadvantage or relationships, are included. However, evidence is purely based on pilot studies and needs further research.

Methodological discussion

As previously mentioned, differences in design between the studies are apparent. After a more extensive examination it is obvious that studies using a retrospective design deliver some evidence that current tools have a good predictive validity among female offenders. This could be due to the fact that retrospective studies often have more participants and therefore a better power. Furthermore, rare events, such as female recidivism, are more easily studied in retrospect because more data can be collected on these events (Salkind, 2010). None of the

prospective studies, which are generally considered as having a higher quality due to reduced risk of biases and the possibility to establish causality (Euser, Zoccali, Jager & Dekker, 2009; Salkind, 2010), find results that support the use of current tools within a female offender population. This shows that the study design should be considered when evaluating VRA tools and more high-quality studies are needed.

22

Furthermore, the reviewed literature has considerable differences regarding the follow-up period, which varies from six months to more than eight years. It is argued that a one-year follow-up is sufficient because it is considered to be the period of maximum risk for recidivism (e.g. Manchak et al., 2009). The same timeframe also limits the risk of a reduced sample size due to attrition (ibid). However, some argue that one year is not enough in order to have a proper assessment of recidivism (e.g. Coid et al., 2009; Salisbury et al., 2009). With a longer follow-up, the risk for attrition bias increases, but it is argued that a statistical comparison of the initial group and the follow-up sample can show whether differences are significant or whether samples, even though reduced, are comparable. The reviewed literature has a great variability in follow-up periods and obvious differences between follow-up periods and results cannot be found. In other words, the follow-up period does not seem to have an effect on the results.

Due to the apparent variability in outcome measures, follow-up time, design, target population and tools, a comparison between studies always poses some difficulties. It should be considered how far in prospect a prediction can be made. A too long of timeframe could be detrimental as risk assessments are and will never be able to predict behaviours too far in the future. It would be beneficial to see some more coherence within research regarding risk assessment.

A further methodological consideration regards the way of measuring the predictive validity. The reviewed studies either use AUC or correlation as a measure of predictive validity. Using measures of correlation has flaws especially when measuring rare events (base rate below 50%) because results are influenced by the base rate (Singh, 2013). In the case of recidivism in females, the base rate is often low which means correlation is not a perfect measure. Moreover, it is argued that significance tests for correlations are imprecise when conducted with samples smaller than 500 participants. Only two of the reviewed studies that uses correlation as a measure of predictive validity includes a sample greater than 500 (Manchak et al., 2009; Rettinger et al., 2010).

The AUC has the advantage of being cut-off independent and base rate resistant. Furthermore, it is considered to be the standard way of measuring predictive validity and most of the studies at hand use this measure. It is argued that the samples should be greater than 200 participants in order to justify the use (Singh, 2013). The minority of the reviewed studies fulfil this criterion. As discussed above, small sample sizes are a recurring problem within the study of female offenders. Additionally, it is argued that the AUC does not measure calibration accuracy but only discrimination accuracy, which means it captures differences between groups rather than being able to identify high risk individuals (Singh, 2013). In order to assess predictive performance better, it is argued by Singh (2013) to use more than one measure of predictive ability.

In addition, examining the predictive validity of current tools to answer the hypothesis whether new tools for females need to be developed might not be the perfect way. For example, issues regarding content validity and its practical utility might be missed. Moreover, it might be difficult to draw the conclusions that new tools are needed based on the fact that current tools do not work as well for females as they should. However, it is considered the only way of gathering suitable literature that can answer the question whether current tools are

23

applicable among a female offender population as many studies do not assess content validity or practical utility.

Another consideration regards the contradiction in trying to prevent violence by assessing risk rather than predicting risk. More specifically, Hart (1998) argues that the goal of VRA should be the prevention of violence and recidivism and not purely predicting it. If prevention is a goal, then this can have an influence on the results (e.g. AUC, correlation) as risk management can mediate the association between risk assessment and recidivism, which will lead to lower values of

predictive validity if the risk management actually reduces recidivism (Belfrage et al., 2012). Additionally, it is argued that most often the potential impact of risk management on recidivism is ignored. In most of the reviewed literature, intervention is not discussed as a possible confounder. Only Gordon and colleagues (2015) discuss that it is not controlled for participation in an

intervention program or for the intensity of supervision, even though it might have an effect.

Strengths and weaknesses of this review

This review advances the understanding of previously executed reviews in the sense that it aims at answering the question whether female-specific tools are needed. Furthermore, the review used a comprehensive search strategy by not only examining four different databases but also going beyond that and using previously noted papers and including references of key papers. This leads to a comprehensive assessment of all evidence available. Moreover, the

comprehensiveness of the evidence makes it possible to assess the predictive ability of five different VRA tools. These five tools are commonly used practice in forensic psychiatry and the institutional setting around the world (Canada, US, UK, Netherlands and Germany).

Even though the VRA tools are commonly used in different countries, the evidence at hand relies on research based on Western cultures and can only be generalised to such. Furthermore, the current review might be constrained by publication and language biases, even though many electronic databases as well as other sources have been used to obtain evidence. As such, no reports, conference proceedings or discussion papers are included and no searches for grey or

unpublished literature have been conducted. However, this kind of material is hard to access and is out of the scope of the current review. Furthermore, language bias might exist due to exclusion of non-English papers. Unfortunately, the

systematic search did not yield many studies discussing SPJ based tools which makes a comparison between actuarial and SPJ tools difficult.

Recommendations and future research

It is recommended for practice that risk assessments are conducted with great caution if they rely upon the tools reviewed in this study. Since there are no alternatives so far that have been researched well enough to give confidence, existing tools need to be used to make assessments. However, practitioners and decision-makers should acknowledge the concerns raised by the current review. It is advised not to base decisions solely on given risk assessments tools but also include questions regarding female-specific risk factors.

There is a great need for future research to explore the validity and reliability of female specific risk factors. Differences between male and female offenders is evident but the relevance for risk assessments is less clear. Therefore, future

24

research should continue to explore the gendered approach. This is not only relevant for risk assessments, but the differences in risk factors and criminogenic needs might also be relevant for treatment and prevention. Furthermore, the influence of intervention and supervision on the association between VRA and recidivism should be emphasised in future research. The results for males, even though not explicitly studied in this review, are not completely convincing either and therefore a critical investigation of current tools should be conducted

regarding both genders. It needs to be established whether SPJ based or actuarial tools are better and if and how current tools can be improved. Especially,

evidence regarding female offenders is scarce and therefore deserves more attention from researchers and practitioners.

25

REFERENCES

Andersson, F. (2013). The female offender: patterning of antisocial and criminal behaviour over the life-course. Malmö University, Faculty of Health and Society. Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (1995). The Level of Supervision Inventory–

Revised. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems, 106, 19-52.

Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J., & Wormith, S. J. (2000). Level of service/case

management inventory: LS/CMI. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems.

Andrews, D. A., Guzzo, L., Raynor, P., Rowe, R. C., Rettinger, L. J., Brews, A., & Wormith, J. S. (2012). Are the major risk/need factors predictive of both female and male reoffending? A test with the eight domains of the Level of Service/Case Management Inventory. International journal of offender therapy and

comparative criminology, 56(1), 113-133.

Benda, B. B. (2005). Gender differences in life-course theory of recidivism: A survival analysis. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative

Criminology, 49(3), 325-342.

Broidy, L., & Agnew, R. (1997). Gender and crime: A general strain theory perspective. Journal of research in crime and delinquency, 34(3), 275-306. Chesney-Lind, M. (1989). Girls' crime and woman's place: Toward a feminist model of female delinquency. Crime & Delinquency, 35(1), 5-29.

Chesney-Lind, M. & Pasko, L. (2013). The female offender: girls, women and

crime (3rd edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Coid, J., Yang, M., Ullrich, S., Zhang, T., Sizmur, S., Roberts, C., Farrington, D.P. & Rogers, R. D. (2009). Gender differences in structured risk assessment: Comparing the accuracy of five instruments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical

Psychology, 77(2), 337.

Daly, K. (1992). Women's pathways to felony court: Feminist theories of

lawbreaking and problems of representation. S. Cal. Rev. L. & Women's Stud., 2, 11.

Davidson, J. T. (2009). Female offenders and risk assessment: Hidden in plain

sight. LFB Scholarly Publications.

De Vogel, V., & de Ruiter, C. (2005). The HCR‐20 in personality disordered female offenders: a comparison with a matched sample of males. Clinical

Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory & Practice, 12(3), 226-240.

De Vogel, V., de Vries Robbé, M., Van Kalmthout, W., & Place, C. (2012). Female Additional Manual (FAM). Additional guidelines to the HCR-20 for assessing risk for violence in women. Utrecht, The Netherlands: Van der Hoeven

26

Dyck, H. L., Campbell, M. A., & Wershler, J. L. (2018). Real-world use of the risk–need–responsivity model and the level of service/case management inventory with community-supervised offenders. Law and human behavior.

Eisenbarth, H., Osterheider, M., Nedopil, N., & Stadtland, C. (2012). Recidivism in female offenders: PCL‐R lifestyle factor and VRAG show predictive validity in a German sample. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 30(5), 575-584.

Euser, A. M., Zoccali, C., Jager, K. J., & Dekker, F. W. (2009). Cohort studies: prospective versus retrospective. Nephron Clinical Practice, 113(3), c214-c217.

Garcia-Mansilla, A., Rosenfeld, B., & Nicholls, T. L. (2009). Risk assessment: Are current methods applicable to women?. International Journal of Forensic

Mental Health, 8(1), 50-61.

Geraghty, K. A., & Woodhams, J. (2015). The predictive validity of risk assessment tools for female offenders: A systematic review. Aggression and

violent behavior, 21, 25-38.

Gordon, H., Kelty, S. F., & Julian, R. (2015). An evaluation of the Level of Service/Case Management Inventory in an Australian community corrections environment. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 22(2), 247-258.

Green, D., Schneider, M., Griswold, H., Belfi, B., Herrera, M., & DeBlasi, A. (2016). A comparison of the HCR-20V3 among male and female insanity acquittees: A retrospective file study. International Journal of Forensic Mental

Health, 15(1), 48-64.

Hare, R. D. (1998). Psychopaths and their nature: Implications for the mental health and criminal justice systems. Psychopathy: Antisocial, criminal, and

violent behavior, 188-212.

Hare, R. D. (2003). The psychopathy checklist–Revised. Toronto, ON, 2003. Hastings, M. E., Krishnan, S., Tangney, J. P., & Stuewig, J. (2011). Predictive and incremental validity of the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide scores with male and female jail inmates. Psychological assessment, 23(1), 174.

Hoffman-Bustamante, D. (1973). The nature of female criminality. Issues

Criminology, 8, 117.

Holtfreter, K., & Cupp, R. (2007). Gender and risk assessment: The empirical status of the LSI-R for women. Journal of contemporary criminal justice, 23(4), 363-382.

Holtfreter, K., Reisig, M. D., & Morash, M. (2004). Poverty, state capital, and recidivism among women offenders. Criminology & Public Policy, 3(2), 185-208. Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2003). Shared beginnings, divergent lives: