Companies’ actions towards global

sourcing risk

A multiple case study on small companies in Sweden

Paper within: MASTER THESIS

Author: EMELIE FAGERLIND

KLARA GRANHEIMER

Tutor: PER SKOGLUND

Master’s Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Companies’ actions towards global sourcing risk: A multiple case study on small companies in Sweden

Authors: Emelie Fagerlind, Klara Granheimer Tutor: Per Skoglund

Date: 2014-05-12

Subject terms: Global sourcing risk, Risk assessment, Risk mitigation, Small

compa-nies and Risk management

Acknowledgements

The process of writing this Master thesis has been very rewarding both on an academic and on a personal level. During this time period there are several persons that have been

sup-ported and encouraged us. In this section we would like to express our appreciation to them.

Firstly, the authors would like to thank the supervisor Per Skoglund for all the comments, guidance and constructive criticism. The time you devoted and the feedback we got have been highly appreciated. Secondly, the authors of this thesis would like to thank the partic-ipating companies and respondents. We highly appreciate the time you set apart for the in-terviews, as well as for being patient during the whole process from the first contact until

the finishing of this study. Without the respondents this thesis would not exist. Finally we would like to express our appreciation to our family and friends for supporting

us and showing patience during this long process of writing a thesis. One special thank goes to our close friends Stefanie Weichert and Sebastian Wachauf-Tautermann for your

encouragement and comments. Thank you.

Jönköping 12th May 2014

______________ _______________

Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to analyze how a small Swedish company manages

two factors of global sourcing risk, namely supply risk and environmental risk in relation to its first-tier global suppliers.

Theoretical framework: The prior research is used to serve as a base for this study and it

mainly includes risk identification, risk assessment, risk mitigation and supplier relationship. Thus, risk assessment tools, risk mitigation approaches and strategies as well as power and trust, in supplier relationship, are discussed. The focus is on the first-tier suppliers, there-fore, only risks related to the supply and the environment are included.

Method: For the purpose of this study, a qualitative approach was taken and an abductive

research process was used, which allowed us to collect prior research simultaneously as the empirical data. Furthermore, a multiple case study was chosen, including seven companies. Ten face-to-face interviews and one email interview were conducted based on semi-structured interview questions.

Findings: The empirical findings collected for this study comply with the prior research in

the theoretical framework to some extent. However, some parts of the prior research were not found as well as new insights were provided. All mitigation strategies discussed in the theoretical framework were applied by the case companies, to some extent. Furthermore, relationships with suppliers appeared to be something the case companies highly valued, and also a strategy used in order to mitigate against risk.

Conclusions: The conclusions drawn in this thesis are mainly that a small company does

not assess risk to a large extent, and reasons for that are that they do not prioritize it. Fur-thermore, a small company having a process for risk assessment in place is using a purely qualitative and relatively simple method. Moreover, a small company makes use of a wide variety of mitigation strategies, however to a different extent. The strategies applied are all characterized by being reactive and rather simple, such as using high inventory levels, safety stock and dual sourcing. It can also be concluded that a small company uses relationship as a mitigation strategy on strategic, tactical as well as on an operational level. Lastly, manag-ing risk is not somethmanag-ing a small company considers as an overall strategic strategy of the company, but rather a consequence of its sourcing decisions. Therefore, the mitigating strategies concern mostly lower levels of tactical and operational nature.

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1

1.2 Problem statement ... 2

1.3 Purpose ... 3

1.4 Definition of key terms... 3

1.4.1 International purchasing and global sourcing ... 4

1.4.2 Risk ... 4

1.4.3 Small companies ... 5

1.5 Disposition of the thesis ... 6

2

Theoretical framework ... 7

2.1 Risk identification ... 7 2.1.1 Supply risk ... 8 2.1.2 Environmental risk ... 9 2.2 Risk assessment ... 9 2.3 Risk mitigation ... 9 2.3.1 Approaches ... 10 2.3.2 Strategies ... 10 2.4 Supplier relationship ... 132.4.1 Supply chain classifications ... 13

2.4.2 Level of supply chain interaction ... 13

2.4.3 Power ... 14 2.4.4 Trust ... 14

3

Method ... 16

3.1 Research approach ... 16 3.2 Research process... 16 3.3 Research design ... 173.3.1 Selection of cases and respondents ... 17

3.4 Data collection ... 18 3.5 Data analysis ... 19 3.6 Trustworthiness ... 20 3.7 Ethical considerations ... 20

4

Empirical findings ... 21

4.1 Company background ... 21 4.2 Risk identification ... 21 4.2.1 Supply risk ... 21 4.2.2 Environmental risk ... 22 4.3 Risk assessment ... 23 4.4 Risk mitigation ... 235

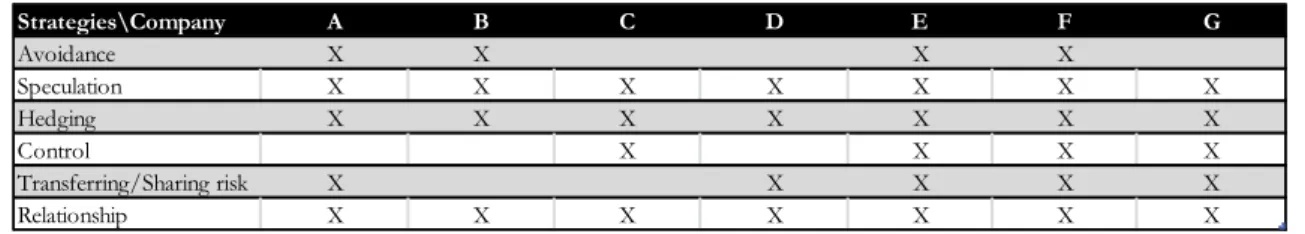

Analysis ... 31

5.1 Global sourcing and international purchasing ... 31

5.2 Risk identification ... 31 5.2.1 Supply risk ... 31 5.2.2 Environmental risk ... 32 5.3 Risk assessment ... 33 5.4 Risk mitigation ... 33 5.4.1 Avoidance ... 33

5.4.2 Speculation ... 34

5.4.3 Hedging ... 35

5.4.4 Control ... 36

5.4.5 Transferring/sharing risk ... 37

5.4.6 Relationship ... 38

5.5 Risk handling in small companies ... 39

6

Conclusions ... 40

6.1 Theoretical implications ... 40

6.2 Managerial implications ... 41

6.3 Limitations and further research ... 41

References ... 42

Appendix 1 ... 48

Tables

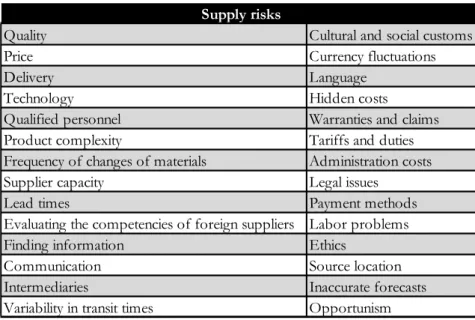

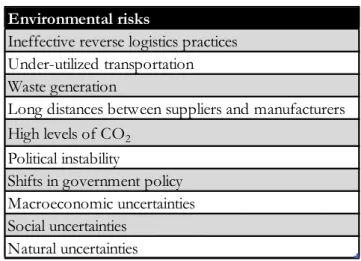

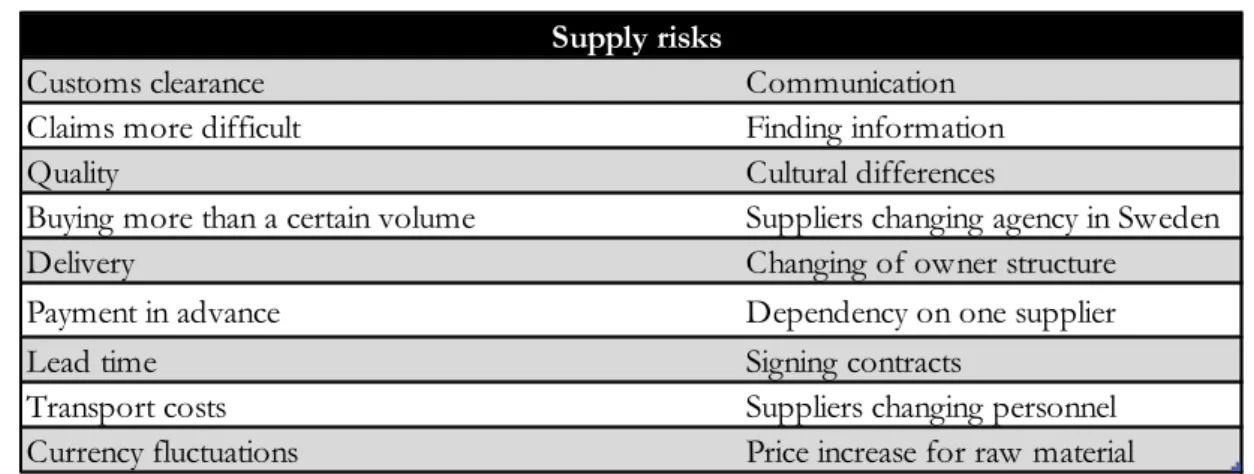

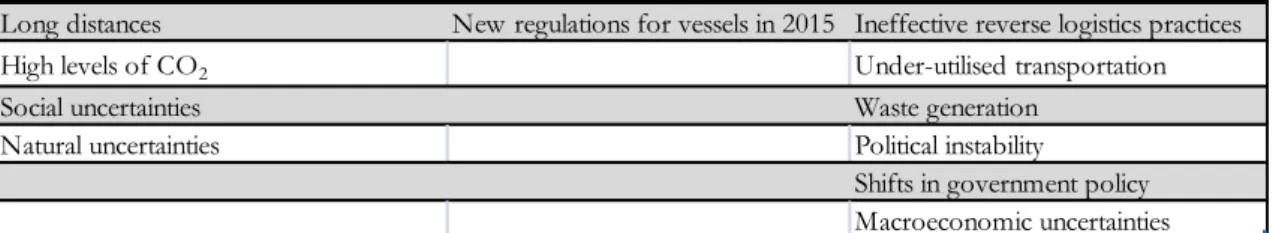

Table 2.1 Supply risks ... 8Table 2.2 Environmental risks ... 9

Table 3.1 Choice of research design ... 17

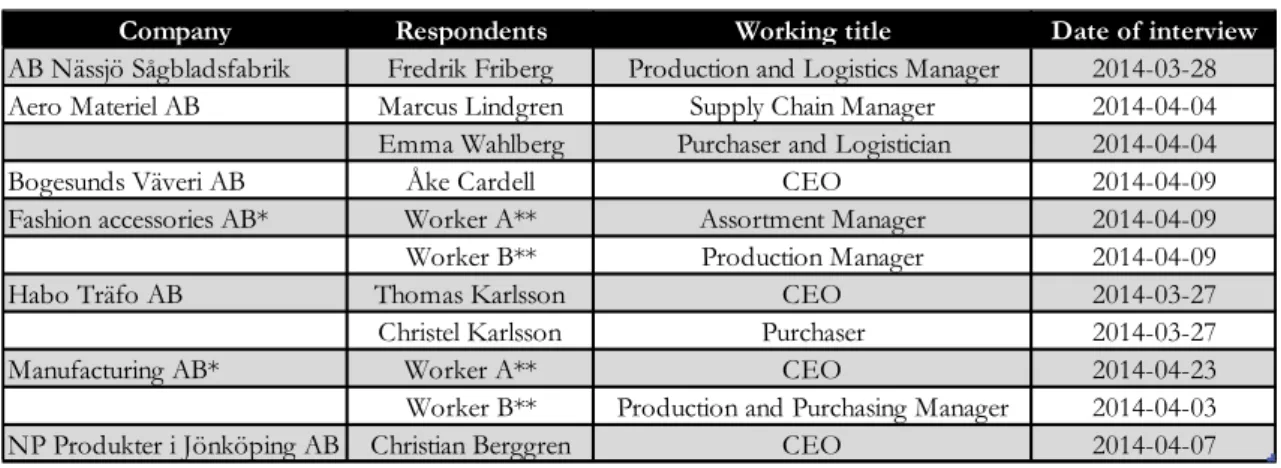

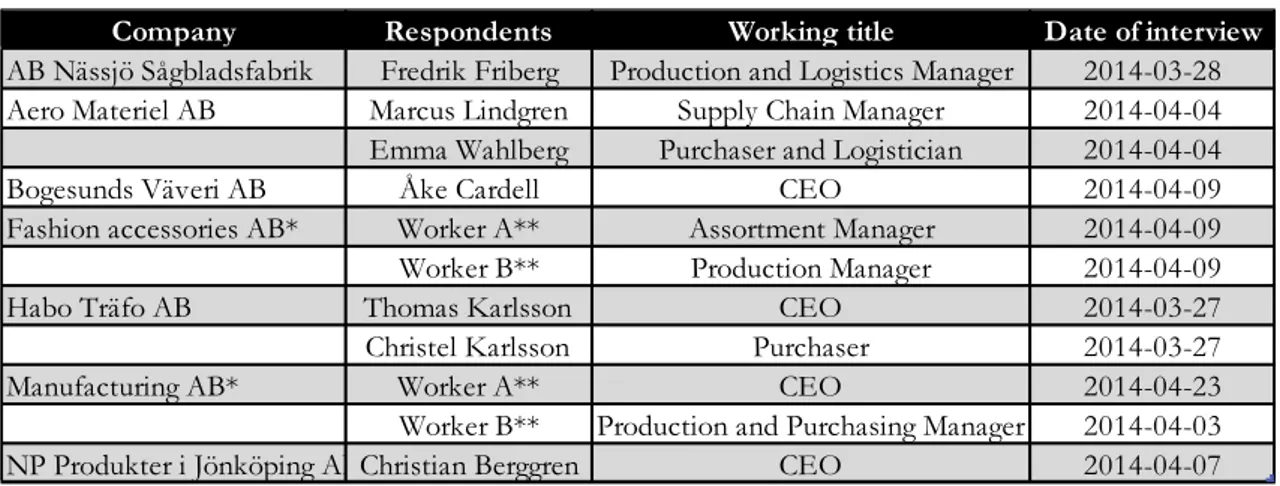

Table 3.2 List of respondents ... 18

Table 4.1 Company information ... 21

Table 4.2 Supply risks ... 22

Table 4.3 Environmental risks ... 22

Table 4.4 Summary of strategies used by the case companies ... 30

Table 5.1 Analysis of supply risks ... 32

Table 5.2 Analysis of environmental risks ... 32

Figures

Figure 1.1 Disposition of the thesis. ... 6Figure 2.1 Perspective of supply risk and environmental risk. ... 7

1

Introduction

In this chapter the reader will be introduced to the topic and context of this thesis. A brief presentation and discussion of risks related to the supply chain and sourcing in a global environment will be given. This is in order to create a basis for understanding of the context, which this thesis will be part of. In addition, this chapter will provide the reader with a presentation of the problem as well as the purpose and the research ques-tions. In the end the most relevant terms and concepts of the thesis will be defined.

1.1

Background

Humans have traded with each other ever since goods were moved among the ancient cit-ies in Mesopotamia, Egypt, China and India. However, trade on a global level did not take place in larger scale until several centuries later, when the shipbuilding and navigation sys-tems improved (Ackermann, Schroeder, Terry, Upshur & Whitters, 2008). During the time of the great explorers and navigators, which started around the mid 1450’s, transporting goods far distances was a risky business. According to the general assumptions back then, only one out of five ships sent out would return. The rest would be lost to pirates, ship-wrecks, storms and other threats. In order for the business to still be profitable, they need-ed to make sure that the profit made from the goods carrineed-ed by the fifth ship would be enough to cover the losses of the others’ failure. Consequently, managing risk in relation to global trade has been the reality for business people during centuries (Moore, 2012). Nowadays, the level of risk is significantly lower than an expected investment loss of 80 percent (Moore, 2012). However, there are a number of risks in every business environ-ment and the changes worldwide contribute to the continuous creation of new risks (Giu-nipero & Eltantawy, 2004). Therefore, it is still crucial to be aware of and manage risks within the supply chain, in order for companies to avoid negative consequences and costly disruptions (Wagner & Neshat, 2012). Even though much has happened during the latest centuries, in terms of supply chain risks, the hazards of piracy are still problematic for mer-chant ships passing the East African coast (The Telegraph, 2014). Apart from that, risks in modern global supply chains are related to currency fluctuations, inaccurate forecasts, vari-ability in transit times, quality, culture, dependency, opportunism and commodity price fluctuations (Cho & Kang, 2001; Chopra & Sodhi, 2004; Ellegaard, 2008; Fisher, 1997; Manuj & Mentzer, 2008a; Monczka, Trent & Petersen, 2006; Spekman & Davis, 2004). Many of the scholars within the field emphasize the fact that global sourcing is more com-plex than domestic sourcing. This is because of the increased inter-firm dependence, as well as the longer supply chains in terms of actors and geographical distance. Altogether, this exacerbates the vulnerability of the firm (Christopher, Mena, Khan & Yurt, 2011; Craighead, Blackhurst, Rungtusanatham & Handfield 2007; Monczka et al., 2006; Wagner & Bode, 2006). Although every company is exposed to risks in the supply chain, it appears that organizations involved in a global supply chain operate in a more complex surround-ing. This is because of the longer geographical distances of the supply chain and the larger number of risks, such as cultural differences, currency fluctuations and variability in transit times that was previously mentioned. According to Jüttner, Peck and Christopher (2003), cost reductions is often the major focus within global supply chains, meaning that inertia risks such as lack of responsiveness and flexibility are usually sacrificed.

Looking at global supply chains, the size of the company seems to have an impact on the level of risk. Large international organizations are usually present in countries in the same area or relatively close to their suppliers, thus they are able to better manage the activities of selecting suppliers internationally compared to smaller companies (Agndal, 2006). In ad-dition, it is argued that mainly large companies can achieve control over activities within the supply chain, and effectively manage the upcoming risks. Small companies are increas-ingly trading internationally, thus they are exposed to similar risks as large firms. However, since they seem to lack necessary resources, processes and structures it is more difficult for small companies to manage the upcoming risks (Jüttner & Ziegenbein, 2009). Hoffmann, Schiele and Kabbendam (2013) stress that bigger firms are able to build up experience fast-er due to their largfast-er volumes purchased compared to small firms. In addition, largfast-er or-ganisations have more resources in place to develop activities for their supply risk man-agement (Hoffmann et al., 2013). Due to the longer and more difficult distances, the lack of organizational capabilities, the slower building of experience and fewer resources, it could be argued that sourcing globally is more complicated and implies more risks for small companies.

These risks could be very costly for firms. Previous studies show that disruptions in the supply chain could have significant negative impact on both operating performance (Hen-ricks & Singhal, 2003, 2005; Jüttner et al., 2003), shareholder value (Hen(Hen-ricks & Singhal, 2003, 2005), and on the performance of the supply chain as a whole (Wagner & Bode, 2008; Wagner & Neshat, 2012). As a consequence of smaller companies usually having less financial resources, in terms of equity reserves and weaker cash flow, their capacity to buff-er themselves against supply risks are limited (Knudsen & Sbuff-ervais, 2007; Thun, Drüke & Hoenig, 2011).

1.2

Problem statement

As stressed above, being aware of and managing the risks are crucial for companies’ surviv-al in the business (Wagner & Neshat, 2012). Christopher and Lee (2004) argue that a supply chain cannot be efficient if it is exposed to high risk. From another point of view, all supply chains are in reality risky, since supply chain disruptions cannot be avoided (Craighead et al., 2007; Giunipero & Eltantawy, 2004). In order to safeguard from these risks the firms need to understand these issues, assess the degree of risk and develop strategies of how to mitigate the consequences (Giunipero & Eltantawy, 2004). However, it appears that most companies lack the tools, understanding, capability and/or willingness to do so (Christo-pher & Peck, 2004; Trent & Monczka, 2005). In addition, Christo(Christo-pher et al. (2011) found in their research that there are differences in the level of maturity of how to manage risks of global sourcing between companies. However, some firms have the right organization in place in order to understand how to manage these risks. Therefore, being one of these firms, having the right capabilities, can be crucial in the competition with other companies (Trent & Monczka, 2005). In addition, companies that manage their supply chain better concerning risk, tend to have a higher performance (Wagner & Neshat, 2012). According to Jüttner et al. (2003) implementing risk assessment throughout the entire supply chain is complex and difficult, due to the large number of actors involved.

It could be argued that smaller companies usually face larger challenges handling these risks. For instance, there are a small number of employees working within these firms, meaning that they usually are more generalists than specialists (Agndal, 2006). Hence, pur-chasing in general and sourcing risk in particular might not get the attention needed within these firms. In addition, the international purchasing approach within these firms is

de-scribed in words such as; unplanned (Scully & Fawcett, 1994) and emergent (Agndal, 2006). According to previous research conducted quantitatively, small firms tend to be reactive towards managing general supply chain risk (Thun et al., 2011) as well as international sourcing risks (Scully & Fawcett, 1994), even though using a proactive or preventive ap-proach appear to be superior in managing supply chain risks (Chopra & Sodhi, 2004; Giu-nipero & Eltantawy, 2004; Grötsch, Blome & Schleper, 2013; Thun et al., 2011).

Even though it is highlighted above that there is an increased popularity of conducting re-search on supply chain risk, there are still limited studies on small companies (Christopher et al., 2011; Ellegaard, 2008; Knudsen & Servais, 2007). Even more specifically, Christo-pher et al. (2011) highlight that there is a need for research in the field of global sourcing risk, focusing on the downstream supply chain, and especially in terms of strategies of how to mitigate these risks. Similarly, Sodhi, Son and Tang (2011) emphasize the need for stud-ies within supply chain risk processes, including assessment and mitigation of risk. As far as we are concerned, there are just a small number of studies covering the topic related to the actions taken by smaller companies to reduce supply chain risks (Thun et al., 2011) and in-ternational sourcing risks (Scully & Fawcett, 1994). For the fact that we have observed that there is a lack of theories covering how small companies manage risk, especially in terms of assessing and mitigating, we argue for that we have found a gap in research, which we in-tend to contribute to.

1.3

Purpose

By taking the aforementioned gap as a starting point and adding the fact that risk manage-ment is considered complicated to implemanage-ment in the whole supply chain, as well as the fact that it is recommended to focus on the downstream flow, our aim is to solely study the fo-cal company’s risks in relation to its first-tier suppliers. Therefore, only the two factors of global sourcing risk, supply risk and environmental risk will be included. More specifically the purpose of this thesis is stated below.

Our purpose with this study is to analyze how a small Swedish company manages two factors of global sourcing risk, namely supply risk and environmental risk in relation to its first-tier global suppliers. In light of the concept of global sourcing risk, being able to identify, assess and mitigate risks appears to be of great importance to reduce the consequences of events occurring. Therefore, this thesis will be formed around these three key words. Identifying risks could be considered a prerequisite for studying risks in general; however the main focus in this thesis will be on the other terms instead. Having that as a background, our intention is to put more emphasize on assessment and mitigation. In order to guide us through this study towards achieving the purpose, the following two research questions are formulated:

How does a small company assess global sourcing risks?

How does a small company act in order to mitigate global sourcing risks?

1.4

Definition of key terms

Some of the key terms of this study are relatively complicated and the meaning of them is not evident. Therefore, this section will provide a discussion regarding these terms, in order for the reader to understand better the meaning of the expressions.

1.4.1 International purchasing and global sourcing

International purchasing literature lack in consistency, in regards to terminology and defini-tions. In fact, a selection of terms exist: international purchasing (Knudsen & Servais, 2007), global sourcing (Trent & Monczka, 2003), global purchasing (Quintens, Pauwels & Matthyssens, 2006) and international sourcing (Scully & Fawcett, 1994). Some authors use the terms interchangeably (Handfield, 1994), while others argue that, there is a significant difference between them (Trent & Monczka, 2003). In comparison with domestic purchas-ing, international purchasing is in general more complex in regards to logistics. This is due to the increased lengths of transport, currency fluctuations, and differences in regulations, time-zone, and language. On the contrary, global sourcing is even more complex than in-ternational purchasing. Global sourcing is more proactively integrated and includes coordi-nation between the buyer’s and the supplier’s operations in terms of materials, designs, processes, technology etc. Furthermore, the integration may also include first and second tier suppliers (Trent & Monczka, 2003).

In coherence with Trent and Monczka (2003) we have decided to distinguish between in-ternational purchasing and global sourcing. It seems like there is a connection between the choice of term and the size of firms studied. Research performed in SMEs tend to use in-ternational purchasing (e.g. Agndal, 2006; Knudsen & Servais, 2007; Servais & Jensen, 2001), while global sourcing is more commonly used in studies of large companies (e.g. Christopher et al., 2011; Deane, Craighead & Ragsdale, 2009; Steinle & Schiele, 2008; Trent & Monczka, 2003). The reason for this is that small companies in general do not view sourcing from another country as a strategic action, which larger companies do to a larger extent.

In line with Trent and Monczka (2003) we define international purchasing as “...a commer-cial purchase transaction between a buyer and a supplier located in different countries” (p. 613). Global sourcing is defined in accordance with Monczka and Trent (1991) as “. . . the integration and coordination of procurement requirements across worldwide business units, looking at common items, processes, technologies and suppliers” (cited in Christo-pher et al., 2011, p. 68).

1.4.2 Risks

When risk is discussed, two different meanings are usually distinguished. These are risk as danger and opportunity, and risks as solely danger. The fluctuation above and under the expected value is usually used as the explanation of risk within classical decision theory as well as according to common practice in the area of business research (Wagner & Bode, 2006). According to March and Shapira (1987, p. 1404) risks are defined as the “variation in the distribution of possible outcomes, their likelihood and their subjective value”. That is an example of the risks viewed both as a danger and opportunity. In contrast, the same au-thors found empirical evidence showing that the majority of managers perceive risks most-ly as puremost-ly danger. More scholars within the field of business research (Wagner & Bode, 2006) have adopted this view. As an example, Harland, Brenchley and Walker (2003) con-clude after discussing several definitions that supply chain risk could be explained by the “chance of danger, damage, loss, injury or any other undesired consequences” (p. 52). In a similar way, but regarding supply risks Zsidisin (2003a) presents another definition: “supply risk is defined as the probability of an incident associated with inbound supply from indi-vidual supplier failures or the supply market occurring, in which its outcomes result in the inability of the purchasing firm to meet customer demand or cause threats to customer life

and safety” (p. 222). Another important term to be clarified is supply disruptions, which is defined as “unforeseen events that interfere with the normal flow of goods and[/or] mate-rials within a supply chain” (Ellis, Henry & Shockley, 2010, p. 35). As stated in the purpose, risk mitigating strategies are one of the major focal points of this thesis and we intend to use the definition presented by Jüttner et al., (2003), risk-mitigating strategies are “...those strategic moves organizations deliberately undertake to mitigate the uncertainties identified from the various risk sources” (p. 200). For the fact that there is an increased frequency and intensity of global occurrences, and that previous scholars have been focusing on the negative consequences of risks (e.g. Christopher and Lee, 2004; Craighead et al., 2007; Wagner & Bode, 2006; Wagner & Neshat, 2012), we find the view of risks as purely nega-tive most used. In addition, this view of risk appears to correspond most to the reality of supply chain business (Wagner & Bode, 2006). Therefore, we will discuss neither positive disasters, nor when companies deliberately gamble on risk.

1.4.3 Small companies

The definition of a small company varies between countries. Within the European Union (EU), a company is classified as small if it has less than 50 employees and an annual turno-ver of maximum 10 million Euros (European Commission, n.d). On the contrary, in the U.S there is no general definition, but rather it depends on factors such as industry, type of product manufactured and type of services provided. A company having 500 employees can still be classified as small (U.S. Small Business Administration, n.d.). According to Cooper (2012), 99,7 % of the companies in the U.S are considered as small. Thus, it is of great importance to be careful in comparing studies conducted on small companies in the U.S and within the EU. Since, this thesis will be based on empirical data from Swedish companies, we will use the definition provided by the European Commission.

1.5

Disposition of the thesis

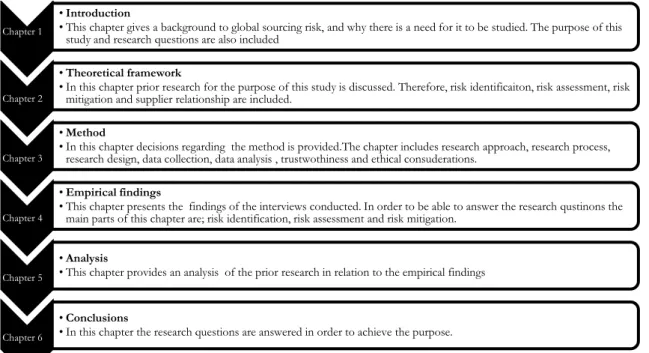

In Figure 1.1 the disposition of the thesis is presented.

Figure 1.1 Disposition of the thesis. Chapter 1

• Introduction

• This chapter gives a background to global sourcing risk, and why there is a need for it to be studied. The purpose of this study and research questions are also included

Chapter 2

• Theoretical framework

• In this chapter prior research for the purpose of this study is discussed. Therefore, risk identificaiton, risk assessment, risk mitigation and supplier relationship are included.

Chapter 3

• Method

• In this chapter decisions regarding the method is provided.The chapter includes research approach, research process, research design, data collection, data analysis , trustwothiness and ethical consuderations.

Chapter 4

• Empirical findings

• This chapter presents the findings of the interviews conducted. In order to be able to answer the research qustinons the main parts of this chapter are; risk identification, risk assessment and risk mitigation.

Chapter 5

• Analysis

• This chapter provides an analysis of the prior research in relation to the empirical findings

Chapter 6

• Conclusions

2

Theoretical framework

In this chapter the theoretical framework will be presented. It begins with three aspects of risk management, namely, risk identification, risk assessment and risk mitigation. In the end of the chapter the relational per-spective taken, will be presented.

According to Christopher et al. (2011), there are no models dealing specifically with risk as-sessment and risk mitigation within the field of global sourcing. However, since global sourcing could be seen as highly related and a part of the supply chain (Christopher et al., 2011), it could be argued appropriate to form the theoretical framework mostly around supply chain risk literature. This chapter is structured in accordance with the three steps of managing supply chain risk within small and medium-sized companies presented by Jüttner and Ziegenbein (2009), which also fits with the concepts stated in the purpose. The section of risk identification will include a classification of risks, mainly focusing on supply risk and environmental risk. The second step include a framework of assessing risk. Risk mitigation is the last step and in that, section approaches and strategies will be presented. In the litera-ture, sourcing is frequently described as the establishment of external relations with suppli-ers, in order to be able to develop and promote effective supply chains (Van Weele, 2005). Therefore, we aim to study global sourcing risk from a relational perspective, which will be added in the end of the theoretical framework.

2.1

Risk identification

Risks within the supply chain can be categorized as either quantitative or qualitative. The first mentioned includes for instance, overstocking, and insufficient availability of material and components, and currency fluctuations. The latter refers to risks such as, poor quality, cultural differences and language barriers (Manuj & Mentzer, 2008b). In order to better be able to understand the quantitative and qualitative risks in relation to global sourcing, they can be classified according to Christopher et al. (2011), that distinguish between supply risk, environmental risk, process and control risk, and demand risk. In accordance with the purpose of the study, the focus will be on supply risk and environmental risk. The part we aim to focus on is in the dotted box shown in Figure 2.1 below.

(adopted from Christopher & Peck, 2004; Mentzer et al., 2001)

Based on different classifications of supply chain risk (Christopher & Peck, 2004; Manuj & Mentzer, 2008b), Christopher et al. (2011) present one model focusing on global sourcing risk. According to our knowledge, these are the only scholars classifying global sourcing risk.

2.1.1 Supply risk

Supply risk can be defined as “... the potential deviations in the inbound supply in terms of time, quality and quantity that may result in uncompleted orders” (Kumar et al. 2010, p. 3718). When the performance of the supplier is inconsistent, the performance is difficult to predict, and thus the supply risk increases. Factors such as capacity constraints in the pro-duction, poor quality control and machine breakdowns, are all examples of issues that can result in interruptions of supply, regarding quantity, quality and lead time (Kumar et al., 2010). As a result of the increased global sourcing, the issue of supply risk has been en-hanced in importance (Deane et al., 2009).

Cho and Kang (2001) further divide global supply risks into three categories; logistics sup-port, cultural differences and regulations. One challenge within logistics support is the long distance that global supply implies. As the geographical distance increases and the lead time lengthen, the number of risks that may occur also increases. Furthermore, unexpected de-lays in delivery can emerge as the transportation systems and intermediaries may not be as reliable as in the home country. The second category is cultural differences which relate to; religion, values, attitudes, manners, customs and language. These are all examples of factors of psychic distance that can disturb the information flow between two firms located in dif-ferent countries (Nebus & Chai, 2012; Prime, Obadia & Vida, 2009). Cultural differences are considered one of the most difficult challenges for companies purchasing international-ly. Due to the cultural differences, miscommunication might create subsequent problems with the supplier. The last category is regulations, which includes governmental regulations, tariffs and quotas etc. (Cho & Kang, 2001). In Table 2.1 supply risks are presented.

Table 2.1 Supply risks

(Cho & Kang, 2001; Chopra & Sodhi, 2004; Ellegaard, 2008; Fischer, 1997; Manuj & Mentzer, 2008a; Monczka et al., 2006; Nassimbeni, 2006; Spekman & Davis, 2004; Thun et al., 2011; Zsidisin, 2003b)

Quality Cultural and social customs Price Currency fluctuations Delivery Language

Technology Hidden costs

Qualified personnel Warranties and claims Product complexity Tariffs and duties Frequency of changes of materials Administration costs Supplier capacity Legal issues

Lead times Payment methods Evaluating the competencies of foreign suppliers Labor problems Finding information Ethics

Communication Source location Intermediaries Inaccurate forecasts Variability in transit times Opportunism

2.1.2 Environmental risk

Deane et al. (2009) define environmental risk as the “...risks associated with the economic, political, cultural, natural, and infrastructure aspects of various countries of the world” (p. 862). Hence, this category includes risks external to the supply chain, which still affect the focal firm. There are several sourcing activities resulting in pollution and emissions of CO2

that negatively impact the environment. Waste disposal and long distances between suppli-ers and the focal firm are two examples of these (Christopher et al., 2011). From a political perspective, risks such as political instability and shifts in governmental policy are also in-cluded in this category (Rao & Goldsby, 2009). The environmental risks found in previous literature are presented in Table 2.2 below.

Table 2.2 Environmental risks

(Christopher et al., 2011; Rao & Goldsby, 2009)

2.2

Risk assessment

Risk assessment is generally described as “... evaluating or calculating the probability of oc-currence of an unwanted event and its impact” (Hoffman et al., 2013, p. 202). Firstly, the probability of each risk needs to be assessed; and secondly, the impact has to be evaluated; and thirdly, the degree of the mitigation actions already in place needs to be assessed (Jüttner & Ziegenbein, 2009). In regards to the probability of a risk to occur, the assess-ment can either be done quantitatively using objective information, based on mathematical rules or qualitatively using subjective information, based on experience, beliefs and judge-ments (Jüttner & Ziegenbein, 2009; Tummala & Schoenherr, 2011; Zsidisin, Ellram, Carter & Cavinato, 2004). Within the perspective of global supply chains, objective information about risks such as disasters tend not to be available, hence basing these decisions on quan-titative data is not appropriate. However, in the case of variations in lead-time there is usu-ally enough historical data in order to make proper estimates of future lead times. There-fore, combining the quantitative and qualitative assessments is appropriate in a global sup-ply chain for assigning probabilities to risks (Manuj & Mentzer, 2008b). However, for small companies qualitative assessment is usually sufficient (Jüttner & Ziegenbein, 2009).

2.3

Risk mitigation

This section is divided into two parts. Firstly, approaches towards risk mitigation will be presented. Secondly, risk mitigation strategies are discussed.

Environmental risks

Ineffective reverse logistics practices Under-utilized transportation Waste generation

Long distances between suppliers and manufacturers High levels of CO2

Political instability

Shifts in government policy Macroeconomic uncertainties Social uncertainties

2.3.1 Approaches

The approach towards mitigation strategies can be either reactive or proactive (referred to as preventive by Thun et al., 2011) (Grötsch, 2013; Knemeyer et al., 2009; Thun et al., 2011; Zsidisin et al., 2000). According to Grötsch et al. (2013) there is also an approach re-ferred to as passive. However, that means to act chaotically and aimlessly, and thus consid-ered to be the weakest approach. Therefore, it will not be further discussed in this section. Reactive

By using the reactive approach, the company reacts after the risk has occurred and the im-pact is only shown after the risk emerges (Grösch, 2013). Reactive instruments are striving to mitigate negative impact that the risk is causing. Examples of reactive instruments are; using multiple sourcing and to use safety stock, in order to mitigate the consequences of a delayed delivery. The reactive instruments do not act directly on the risks; instead they are striving for absorbing the damage caused by a risk. It appears that small and medium-sized companies often focus on reactive instruments, by building up redundancies. On the con-trary, larger companies appear to work more proactively, trying to decrease the likelihood of a risk to occur (Thun et al., 2011). There are some explanations why small companies tend to use more reactive measures, such as high levels of inventory. Firstly, their custom-ers often do not want to hold inventory themselves but rather request short lead times. Secondly, the small companies usually are not able to provide their customers with infor-mation that could be a substitute for inventory (Christopher & Lee, 2004). As a conse-quence of being forced to keep higher levels of inventory, there are potential subsequent risks for these companies to meet the cost targets (Jüttner & Ziegenbein, 2009).

Proactive

When the company plan ahead to mitigate the risk before they occur, they use a proactive approach. Similar to the reactive approach, the proactive approach is induced before a risk emerge, however the difference is that the latter only shows an impact on the firm after the occurrence takes place. Therefore, a proactive approach focuses on both identifying poten-tial risks, determine the probability of the risks to occur and plan and operate for mitigation before risks emerge (Grötsch, 2013). Furthermore, Thun et al. (2011) stress those proactive instruments try to decrease the probability of a risk to occur within the supply chain. Some examples of proactive instruments are track & trace and radio-frequency identification (RFID). These instruments are proactive as they control processes and the potential prob-lems are identified earlier in the supply chain, which can lead to avoidance of the problem. However, track & trace and RFID are expensive to implement, thus many small and medi-um sized companies do not have the resources needed. In addition, it might not be appli-cable for companies only having small flows of material, information etc. (Thun et al., 2011).

2.3.2 Strategies

Mitigation strategies are defined as “... those techniques that are employed prior to disrup-tions” (Deane et al., 2009, p. 877). Traditionally, strategies such as multiple sourcing and safety stock were widely used to prevent risks from occurring. However, using these buff-ers often limited the operational performance of companies and it resulted in firms being less efficient. In addition, it had a negative impact on the companies’ competitive ad-vantage. Therefore, new approaches towards risk management have been adopted (Guini-pero & Eltantawy, 2004). In integrating the company’s internal functions and connecting them with external actors such as suppliers, firms seek to reduce the risk (Christopher et

al., 2011; Guinipero & Eltantawy, 2004). By basing the relationship to the supplier on trust and transparency of information, the collaboration is enhanced and the risks are reduced (Christopher et al., 2011; Christopher & Lee, 2004; Spekman & Davis, 2004).

There are several strategies of how to mitigate risk within the context of the entire supply chain (e.g. Jüttner, Peck and Christopher, 2003; Guinipero & Eltantawy, 2004; Christopher & Peck, 2004; Manuj & Mentzer, 2008a; 2008b; Son & Orchard, 2013). However, it ap-pears that Christopher et al. (2011) are the only researchers providing a model entirely fo-cusing on global sourcing. Their model includes network re-engineering, collaboration be-tween global sourcing parties, agility and creating a global sourcing management culture. After revising their model, it appears that it might not be more appropriate in our case, than those focusing on the entire supply chain. The reason why, is that the purpose of this thesis is to study small companies where the purchasing strategy is described as unplanned (Scully & Fawcett, 1994) and emergent (Agndal, 2006) and the strategies presented by Christopher et al. (2011) are considered being on a too high strategic level, therefore less hands on and practically feasible compared to the model provided by Manuj and Mentzer (2008b). In their study, they present seven different mitigation strategies based on Miller (1992), namely avoidance, postponement, speculation, hedging, control, transfer-ring/sharing risk and security. Below a description of these will follow.

Avoidance

“Avoidance occurs when risks associated with operating in a given product market or geo-graphical area are considered to be unacceptable” (Miller, 1992, p. 322). Depending on the firms’ participation in uncertain markets or not, different avoidance strategies are needed. Firms that are already present in an uncertain market, can use divestment in order to exit the market, while firms not yet active in these type of markets, might wait to enter into these markets until the uncertainties have decreased to more decent levels. In addition, firms can also choose to only be present in markets with low uncertainty, thus utilizing a more careful approach (Miller, 1992).

Postponement

Postponement means that the actual commitment of resources, such as labeling, assembly, packaging and manufacturing, is being delayed in order for the company to be more flexi-ble. The examples just mentioned are categorized as form postponement, which also im-plies that the costs incurred will be delayed. Another category is time postponement, which refers to companies that do not move the goods from the manufacturing plant until they received a customer order. This strategy is argued to have great potential benefits (Manuj & Mentzer, 2008b). Furthermore, this category is similar to the agility strategy presented by Christopher et al. (2011).

Speculation

The opposite of postponement is speculation, since decisions are based on a forecasted customer demand. In this strategy, risks are selectively taken, meaning that there is a deci-sion behind which risks are acceptable and which are not (Manuj & Mentzer, 2008b). Hedging

In the context of a supply chain, hedging can be done by having a dispersed base of cus-tomers, suppliers and facilities. By using this approach, single events such as natural

disas-ters and currency fluctuations do not affect the whole supply chain at the same time and/or with the same severity. Dual sourcing is an example of hedging against risks of dis-ruption, quality, quantity, price and opportunism (Manuj & Mentzer, 2008b). In addition, Vestring, Rouse and Reinert (2005) emphasize creating a balanced portfolio of risks and benefits by choosing different regions and countries to source from. It is also of great im-portance that this portfolio is created to have an appropriate balance over short and long term.

Control

A number of risks lead companies to integrate vertically. These are for example, power bal-ance within the buyer-supplier relationship, asset specificity and opportunism (Williamson, 1979), by the supplier. By vertically integrating, the control might increase since the risks of supply are reduced. Another control mechanism relates to the design of contracts. Flexible clauses and contracts based in a country with better legal resources might be helpful if something goes wrong (Manuj & Mentzer, 2008b).

Transferring/Sharing Risk

Sharing of risks can be done in several ways through off-shoring, outsourcing and contract-ing. In using off-shoring and outsourcing the risks have been transferred to the supplier, however this means that the control is reduced (Manuj & Mentzer, 2008b).

Security

The technology has facilitated the identification of risky shipments. Nowadays, it is rather easy to get to know exactly what goods are moving, as well as identifying unusual and cau-tious elements worth focusing on (Manuj & Mentzer, 2008b).

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the strategies used for mitigating risks must “fit” the specific firm, in terms of characteristics and needs. The environment that surrounds the firm and its supply chain will lead to them using different strategies for assessment and mit-igation (Manuj & Mentzer, 2008b). Since this thesis is to be analyzed from a relational per-spective, the categories of postponement and security are considered to lack in relevance, and thus will be disregarded.

Strategic decisions within the field of logistics are traditionally discussed in terms of strate-gic, tactical and operational. Strategic decisions are taken in a long-term perspective, over one or more years, affecting the overall business. Tactical decisions refers to a shorter time horizon stretching from monthly to annually, focusing more on, for example, the produc-tion planning. Lastly, operaproduc-tional decisions are even more short-term, related to the daily and weekly operations within a firm (SteadieSeifi, 2011). In order to clarify the five mitiga-tion strategies described above, as well as put them into an more understandable context, the three levels of strategic decisions will work as a basis when summarizing these. The strategy of avoidance could be considered being on a strategic level, since it involves which regions to source from, or more precisely not to source from, and thus more related to the overall strategy of the firm. Furthermore, hedging and control could also be seen as includ-ing decisions on a strategic level, such as creatinclud-ing a balanced portfolio of risks and integrat-ing vertically. On the contrary, actions within the category of transferrintegrat-ing/sharintegrat-ing of risk could be categorized as tactical. The reason for that is that the actions within this strategy relate to contracting, which could be classified as a middle-term decision. Lastly,

specula-tion refers to acspecula-tions taken on a more regular basis in a short-term perspective, such as keeping safety stock, and thus could be considered as operational decisions.

2.4

Supplier relationship

In mitigating risks within the supply chain, collaboration between the actors is of great im-portance, since it can reduce the risk (Christopher et al., 2011). Therefore, the relational perspective is emphasized as a suitable way of analyzing risk management within organiza-tions (Chen, Sohal & Prajogo, 2013). The perspective of the supply chain serves as a basis in understanding the buyer-supplier relationship. Hence, a supply chain classification and various types of buyer-supplier relationships is presented below. Buyer-supplier relation-ships will be discussed in relation to two parameters, power and trust, since these factors are considered to be of great importance in long-lasting partnerships (Skoglund, 2012).

2.4.1 Supply chain classifications

In accordance with Harland (1996), supply chain management can be divided into four sys-tem levels. The first level refers to the internal chain within a company. The other levels all exist in integration with other organizations, inter-organizational relations. The second level is the dyadic level that exists between two parties, whereas the third level refers to the ex-ternal chain, which is an extension of the dyadic relationship also including customer’s cus-tomers and supplier’s suppliers. The fourth and last level is the network where different supply chains are interconnected. Mentzer, DeWitt, Keebler, Min, Nix, Smith and Zacharia (2001) present a three-step categorization. In contrast to the previous mentioned categori-zation, the first internal level is excluded and instead of a dyadic relationship, they suggest a triadic relation, including the focal firm, its first-tier supplier and its first-tier customer.

2.4.2 Level of supply chain interaction

A continuum can be used to describe the degree of interaction between two actors within the supply chain. This continuum ranges from single transactions to fully integration within the organization. Within this scale three levels can be identified, ranging from low to high, i) transaction, ii) collaboration and iii) integration. Depending on how much effort that is put into the relationship and how big the yield is, the level of integration varies. (Bäck-strand, 2007).

Transaction relationships are usually based on the concept of transaction cost economics (Williamson, 1985) and the main consideration is to minimize the transaction cost. The fo-cus in this arm’s-length type of relationship is on the transfer or exchange of goods and services as well as to secure against bounded rationality and opportunistic behavior. Related to opportunism, (1999) describes these types of relations in terms such as distrust and competition. Examples of this collaboration could be defined as “...working jointly or co-operating with someone who one is not immediately connected to” (Bäckstrand, 2007, p. 35). In similarity to the transaction relationship, transaction cost economics can also be suitable in describing collaboration relations, which is a type of partnership. Terms such as bounded rationality, asset specificity and opportunism are usually referred to in transaction cost economics. In addition, the industrial network approach, which is described by three factors, namely actors, resources and activities, could be relevant in this discussion (Håkansson, 1989; Williamson, 1985). Partnership and adversarial relation are two exam-ples of collaboration relationships (Bäckstrand, 2007). Power-dependence and adversarial interactions are typical ways of identifying these two relationships in relation to transaction cost economics, whereas interdependence-trust and collaboration are used within the

in-dustrial network approach (Skoglund, 2012). The last level is integration, which is defined as “the incorporation of two units into one unit” (Bäckstrand, 2007, p. 35). This category includes more formal relationships, such as joint ventures and fully integrated ownerships (Bäckstrand, 2007).

In the next sections, the two parameters of buyer-supplier relationships presented above will be discussed in more detail.

2.4.3 Power

Usually, power and dependence are considered to be contradictory (Cox, 2004). In a “sup-ply chain context power could be defined as “the capacity to optimize the behaviour of suppliers and subcontractors in accordance with desired performance objectives” (Stannack, 1996, p. 51). Even though only the upstream perspective is discussed, it is rea-sonable to argue that it would be relevant in a downstream perspective as well. There is a relationship between power and dependence, meaning that low power also leads to low de-pendence, thus a situation of independence (Cox, 2004). However, if the power is unevenly distributed between the actors and one of them acts in an inappropriate way, the part being unfavorably treated usually seeks an alternative partner. In addition, whether a company is proactive in its way of managing risk in relation to its suppliers, it is much more likely if they have a power advantage in the relationship (Cox, Watson, Lonsdale & Sanderson, 2004).

In a dyadic relationship, the perceived dependence has an effect on the perceived vulnera-bility of the companies. Vulneravulnera-bility is defined as “...the simultaneous consideration of a disturbance and the negative consequences of this disturbance” (Svensson, 2004, p. 469). The higher the level of dependence the higher will also the perceived vulnerability becomes (Svensson, 2004).

2.4.4 Trust

Trust is defined as “one party’s confidence that the other party in the exchange relationship will not exploit its vulnerabilities” (Dyer & Chu, 2000, p. 260). Trust could be described as the glue that bring parties together and also as a factor that can reduce transaction costs (Heumer, 2004). In social exchanges as well as in business and work relations, trust is of great importance (Young, 2006).

As mentioned above interdependence is usually a result of high levels of power. However, there are other explanations as well. Håkansson and Snehota (1995) argue that interde-pendence can be an effect of interaction in a long-term relationship, or as an action actively taken by the parties to demonstrate trust and interest in continuously cooperating with each other (Håkansson & Snehota, 1989). During a relationship, several adaptations occur from each party’s side. They learn about each other’s processes and routines and the information is transferred smoothly. The interdependence is present on several levels, between actors, resources and activities (Håkansson & Snehota, 1989).

It is important to distinguish between pure dependence and interdependence. The first mentioned is directed only in one way, whereas the latter is directed in at least two ways. Being dependent is a situation that is avoided by every part. However, a state of interde-pendence is usually a result of purposeful actions, where the parties lock themselves in a re-lation aiming for a long-term cooperation (Skoglund, 2012). Trust appears to be a key in in-terdependent relationships and the more emotions that are involved, the lower the risk

as-sessment (Young, 2006). Similarly, it is argued that risk and trust are contradictory (Heu-mer, 2004). Furthermore, there is a relation between trust and the handling of contracts. In relations including a high level of trust contracts serve as support for the coordination, whereas in relations where the level of trust is low, contracts have a different function, fo-cusing on control and power (Mellewigt, Madhok, & Weibeld, 2007).

3

Method

In this chapter there will be a description of how this research was conducted and why. The major parts in-cluded are research approach, research design, selection of cases, method of data collection as well as method of data analysis. Lastly, there will be a discussion regarding trustworthiness.

3.1

Research approach

In order to achieve the purpose, a qualitative approach was taken, since it provides a deep-er unddeep-erstanding for the topic studied (Holme & Solvang, 1997). The qualitative and the quantitative are the most widely used approaches (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2009). One of the main differences between the two approaches is that a qualitative study is based on opinions and meanings motivated by words, whereas a quantitative study is based on num-bers and statistics. Furthermore, quantitative studies result in numerical and statistical data, are based on many respondents, while qualitative studies require classification into catego-ries, and are based on a relatively low number of respondents (Saunders, Lewis & Thorn-hill, 2009).

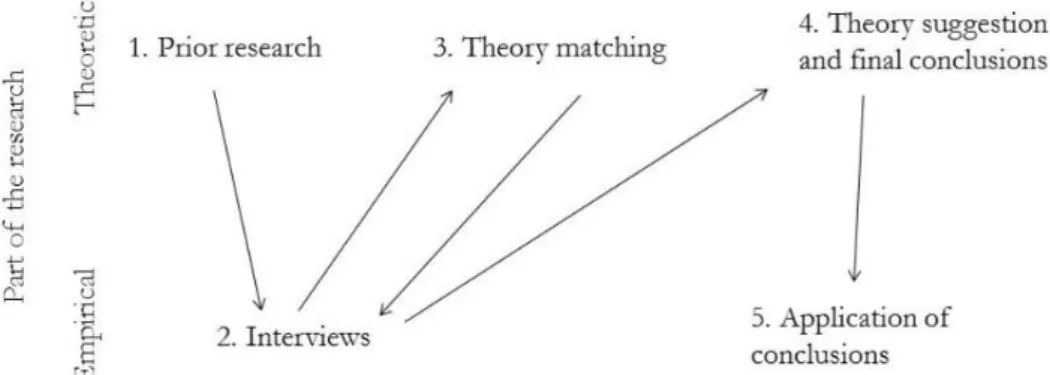

Another type of decision that needs to be considered is whether to use the deductive, in-ductive or abin-ductive approach (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2008). The approach devoted in this thesis is the abductive, which is commonly used in case studies. An abductive approach was chosen as it allowed us to collect theory and empirical data simultaneously, which im-plies a learning loop (Pedrosa, Näslund & Jasmand, 2012). Thus, we were able to change and add theory depending on the empirical data we collected. As can be seen in Figure 3.1 the abductive approach is influenced by both the inductive and deductive, but unlike the other approaches, the abductive approach has the advantage to imply understanding (Al-vesson & Sköldberg, 2008).

3.2

Research process

The research started with the first version of a theoretical framework, which was used in designing the interview questions. Then interviews were carried out, and after each inter-view we reconsidered and updated the theoretical framework if something new were found that we had not included before, hence new theory were added. Thus, the interviews and theory matching were done simultaneously. When all the interviews were executed and the theory was matched, we analyzed the empirical findings together with the theory. That re-sulted in suggested new theory and conclusions. At last, the conclusions were applied on the companies interviewed. The process is shown in Figure 3.1.

(adopted from Pedrosa et al., 2012)

Figure 3.1 Research process.

3.3

Research design

When choosing research strategies, there are a number of factors that need to be taken into consideration, which are presented in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1 Choice of research design

(Yin, 2009)

To begin with, the research questions that are stated in order to achieve our purpose should be paid attention to. As this thesis aims to answer the two research questions focus-ing on “how”, only experiment, history or case study appear to be appropriate. Since we neither have the attention to control the behavior of our interviewees nor to study a con-temporary event, we chose to conduct a case study. This is also in coherence with Christo-pher et al. (2011), who argue for the case study as being the most appropriate choice when conducting research within logistics.

In the beginning of the study, three cases were included. Since that appeared not being enough, other cases where added gradually until data saturation was considered reached. This is in accordance with the abductive approach, since adding new cases are necessary in order to test and develop theories (Danermark, Ekström, Jakobsen, & Karlsson, 2003).

3.3.1 Selection of cases and respondents

In order to select cases we used a few criteria. Since the purpose of this study is to study small companies, they had to fit with the definition of a small company (European Com-mission, n.d.). Furthermore, we chose companies within different industries, manufactur-ing, wholesaling and fashion, with the intention to get a broader view. The website www.allbolag.se was used in order to screen for companies located relatively close to

Jön-Method Form of research question Requires control of behavioral events? Focuses on contemporary events?

Experiment How, why? Yes Yes

Survey Who, what, where, how many, how much? No Yes Archival Research Who, what, where, how many, how much? No Yes/No

History How, why? No No

köping. On the one hand, it was practically impossible to cover the entire Sweden within the study, and on the other hand, there is no guarantee that the result would have been bet-ter. Therefore, we argue for only using companies in the region of Jönköping. However, this will have a negative impact on the generalizability of the study to other companies in other parts of the country. After the screening, we called the CEO of the companies we found. Since our purpose is to study global sourcing risk, we only proceeded with the com-panies that had at least one supplier located internationally, which they purchase from on a relatively regular basis.

The selection of respondents was made together with the CEO of the companies. Our in-tention was to speak to the CEO as they usually have a holistic view of the company, the purchasing manager, as they presumably work within purchasing daily and the logistics manager, as we believed that they are familiar with our topic. However, since we are focus-ing on small companies, not all of them had an employee for all the requested positions. A limitation of this study is that in three out of the seven companies, only one respondent was interviewed. The reason for not including more respondents was simply that there were no more employees involved in the purchasing and logistics processes. This can have an impact on the study, since the respondents can have biased the answers. The ents and companies are all listed in Table 3.2. Since some of the companies and respond-ents would like to be anonymous in the study, the respondrespond-ents will be referred to as (Com-pany A, B, C etc.) in the empirical findings chapter. This means that the reader will not be able to link the label, neither to the companies nor to the respondents. Consequently, two respondents from the same company will be referred to by the same label, and thus not able to distinguish. We do not believe that this could have any major influence on the study, since it is of little importance to distinguish between the different respondents. It is of greater interest to be able to differentiate the companies.

Table 3.2 List of respondents

3.4

Data collection

The data collection was done by using face-to-face semi-structured interviews as well as one interview via email. According to Yin (2009) interviews are one of the most important sources when it comes to case studies. We chose to conduct interviews as it is possible to focus directly on the research questions and, in addition, it provides insights since infer-ences and explanations can be given. By conducting semi-structured interviews, infor-mation can be obtained in a flexible way as questions can be added to provide a deeper

ex-Company Respondents Working title Date of interview

AB Nässjö Sågbladsfabrik Fredrik Friberg Production and Logistics Manager 2014-03-28

Aero Materiel AB Marcus Lindgren Supply Chain Manager 2014-04-04

Emma Wahlberg Purchaser and Logistician 2014-04-04

Bogesunds Väveri AB Åke Cardell CEO 2014-04-09

Fashion accessories AB* Worker A** Assortment Manager 2014-04-09

Worker B** Production Manager 2014-04-09

Habo Träfo AB Thomas Karlsson CEO 2014-03-27

Christel Karlsson Purchaser 2014-03-27

Manufacturing AB* Worker A** CEO 2014-04-23

Worker B** Production and Purchasing Manager 2014-04-03

NP Produkter i Jönköping AB Christian Berggren CEO 2014-04-07

* The name of the company is in reality something else ** The respondent chose to be anonymous

planation. In addition to that, certain questions can be excluded if the interviewee does not feel comfortable answering the specific question or does not think it will provide input to the study (Bailey, 2007). One of the drawbacks with interviews is that the formulation of questions can lead to a poor result (Yin, 2007). To reduce this risk, we based our interview questions (see Appendix 1) on questions used in previous studies within the area (Black-hurst et al., 2005; Christopher et al., 2011). Two other disadvantages are the variations in how the different interviewees answer the questions and that they answer the questions in the way they think the interviewer would like, instead of being totally honest (Yin, 2007). However, these drawbacks are harder to prevent. As we only did face-to-face semi-structured interviews and one interview via email, we only collected primary data (Saunders et al., 2009). The interviews were carried out in Swedish, meaning that the authors of this thesis translated everything to English. For example, this means that, the quotes were not translated literally. This might have influenced the empirical findings as well as the analysis and conclusion. However, the empirical part was sent to the case companies in order for them to check for possible misunderstandings. The interviews contained mostly open-ended questions, which enabled the respondents to answer them in more detail and crea-tively. Furthermore, the questions were phrased to stimulate unbiased, truthful and unaf-fected answers.

Interim summaries were done during the collection of the data in accordance with Saun-ders et al. (2009). Due to the summaries, we could see what had been found so far, if we had to add something to the theoretical framework and it also enabled us to change the questions for the rest of the interviews if we found it necessary. As we got the opportunity to audio record the interviews, both of the researchers could fully concentrate on the re-spondent and the interview. It also allowed us to use direct quotes for the empirical data (Saunders et al., 2009).

3.5

Data analysis

A case study-based research requires analysis of the data, and it often involves categoriza-tion, interpretation and inferences (Pedrosa et al., 2012). The data analysis for this study was carried out by following a model in Roulston (2014), analyzing and representing inter-view data: practical steps. The first step was to reduce data to locate and examine phenom-ena of interest, which was made by eliminating repetitive statements and data irrelevant to the topic. In order to carry out this step, we colored the parts in the transcripts with differ-ent colors depending on what answers that belonged to which part in the theoretical framework, for example, risk identification, risk assessment and risk mitigation. Thus, the uncolored text was reduced. Thereafter, we proceeded to the second step, which includes reorganizing, classifying and categorizing data. This was done by re-coloring the important information by respondent instead, so every respondent was tied to a specific color, and that was done in order for us to be able to see which information that was received from which respondent/company. Then we printed the colored information and cut it into small pieces and placed them in categories where they fitted, having the theoretical framework as a base. This was done for the mitigation part of the thesis as we realized that it was the part where we got the most information. The categories were structured in the same way as the mitigation part in the theoretical framework. Then in the third step, interpreting and writ-ing up findwrit-ings, the researchers should consider assertions and propositions in light of pri-or research and thepri-ory in pri-order to develop arguments. This was done by comparing the prior research with the empirical findings.

3.6

Trustworthiness

In order to measure the quality of research, some criteria can be evaluated. We chose to base mainly this part on Pedrosa et al., (2012), who analyzed 134 case study- based articles in the field of logistics and supply chain management in order to assess and evaluate the quality of the articles. Thus, we found it relevant to use this article as a base for the quality discussion of this thesis. Trustworthiness is divided into three parts; transferability, truth-value and traceability.

Transferability refers to “the extent to which a study’s findings apply to other contexts” (Pedrosa et al., 2012, p. 278). It is similar to external validity, which refers to generalization, however, transferability acknowledges that time can change context and people, which is a limit to the opportunity to generalize findings. Pedrosa et al. (2012) present some actions that could be taken in order to enhance the transferability. In this thesis, Pedrosa et al. (2012) were followed by explaining how and why the cases were selected, which is neces-sary to provide the reader with insight into the suitability of the cases for the research pur-pose, questions and the context studied.

Truth-value refers to “the match between informants’ constructed “realities” in their par-ticular context and those represented by the researcher” (Pedrosa et al., 2012, p. 278). It emphasizes the importance of respondents correcting and/or confirming the researcher’s interpretation of their answers. In order to enhance the truth-value of this thesis we sent a draft of the empirical findings to the respondents, which allowed them to confirm that the information was true and that we were allowed to use it in the thesis. We also described the data analysis process, which allows assessment of how the data were processed to generate the findings, and therefore to judge the truth-value. Both of the methods used are in line with what is presented in Pedrosa et al. (2012).

Traceability relates “to the documentation of the research process and data sources” (Ped-rosa et al., 2012, p. 279), and it includes for example dependability. In order to enhance the traceability, a description of the data collection technique and process, and an explanation of how and why the respondents were selected are important (Pedrosa et al., 2012). Those recommendations were all followed in this thesis.

3.7

Ethical considerations

In order to comply with general ethical considerations, the respondents had the opportuni-ty to be anonymous if they wanted to. Moreover, they could choose not to answer the questions and could end the interview anytime they wanted. All the aforementioned meth-ods are in line with the recommendations in Saunders et al. (2009).

4

Empirical findings

The empirical findings are divided into three parts. To begin with, there will be a discussion regarding risk identification, where tables of both supply risk and environmental risk are presented. Then, findings related to risk assessment and risk mitigation will be discussed. In other words, the empirical findings will follow the same structure as the theoretical framework.

4.1

Company background

In Table 4.1 a short description of the case companies is provided. As presented before, the respondents and the companies will be referred to as Company A, B, C, D, E, F and G and the labels were added in a random order.

Table 4.1 Company information

4.2

Risk identification

Most of the case companies lack a process for risk identification (Company A; B; C; E; F). According to Company A, they do not identify risks as they never experienced any issues related to supply, whereas Company B claims that the reason for not identifying risks is that they have not searched for any new suppliers lately. However, this is likely to happen in the future. Furthermore, it is stressed that lack of time is a reason for not identifying risks (Company B). The only company that identifies risks is Company D, which stresses that they are aware of existing risks.

4.2.1 Supply risk

The conception of the existing risks, both in terms of supply risk and environmental risk differs between the companies in the study. In Table 4.2 the supply risks that are men-tioned are listed.

Company Respondents Working title Date of interview

AB Nässjö Sågbladsfabrik Fredrik Friberg Production and Logistics Manager 2014-03-28 Aero Materiel AB Marcus Lindgren Supply Chain Manager 2014-04-04 Emma Wahlberg Purchaser and Logistician 2014-04-04 Bogesunds Väveri AB Åke Cardell CEO 2014-04-09 Fashion accessories AB* Worker A** Assortment Manager 2014-04-09 Worker B** Production Manager 2014-04-09 Habo Träfo AB Thomas Karlsson CEO 2014-03-27 Christel Karlsson Purchaser 2014-03-27 Manufacturing AB* Worker A** CEO 2014-04-23 Worker B** Production and Purchasing Manager 2014-04-03 NP Produkter i Jönköping ABChristian Berggren CEO 2014-04-07

* The name of the company is fictional ** The respondent chose to be anonymous