Swedish Dialects and Folk Traditions, 1981

SVENSKA

LANDSMÅL

OCH

SVENSKT FOLKLIV

Tidskrift utgiven av

Dialekt- och folkminnesarkivet i Uppsala

genom

ERIK OLOF BERGFORS,

redaktör,

och

SVEN SÖDERSTRÖM,

redaktionssekreterare,

under medverkan av

Lennart Elmevik, Folke Hedblom, Åsa Nyman och Bo Wickman, Uppsala, Hugo Karlsson, Göteborg, Bengt Pamp, Lund, Åke Hansson, Umeå

1981. Årgång 104

H 305 från början

SWEDISH DIALECTS

AND

FOLK TRADITIONS

Periodical founded in 1878 by J. A. Lundell

Published by

THE INSTITUTE OF DIALECT AND FOLKLORE RESEARCH, UPPSALA

Editor:

ERIK OLOF BERGFORS

Editorial assistant:

SVEN SÖDERSTRÖM

In collaboration with Lennart Elmevik, Folke Hedblom,

Åsa Nyman, and Bo Wickman, Uppsala, Hugo Karlsson, Göteborg, Bengt Pamp, Lund, Åke Hansson, Umeå

1981

Volume 104SVENSKA LANDSMÅL

OCH

SVENSKT FOLKLIV

Tidskrift grundad 1878 av J. A. Lundell

Utgiven av

DIALEKT- OCH FOLKMINNESARKIVET I UPPSALA

Redaktör:

ERIK OLOF BERGFORS Redaktionssekreterare: SVEN SÖDERSTRÖM

Under medverkan av Lennart Elmevik, Folke Hedblom,

Åsa Nyman, och Bo Wickman, Uppsala, Hugo Karlsson, Göteborg, Bengt Pamp, Lund, Åke Hansson, Umeå

1981

Årng 104

Tryckt med bidrag från

Humanistisk-samhällsvetenskapliga forskningsrådet

ISSN 0347-1837

Innehåll/Contents

BERGFORS, ERIK OLOF, och GUSTAVSON, HERBERT, Nils Tiberg

1900-1980 68

Summary 71

BROBERG, RICHARD, Karl L:son Bergkvist 1899-1980 76

Summary 77

HEDBLOM, FOLKE, Swedish Dialects in the Midwest: Notes from

Field Research 7

HOLMBERG, KARL AXEL, MåSe, possa och sporr. Om ord på gam-

malt ör, ös 27

Summary: On Swedish words with short root syllables, contain-

ing old Sw. ör, ös 38

ORDtUS, TORSTEN, Ljud på band. Att spela in rätt och bevara

betryggande 39

Summary: How to record in tape and preserve the recordings 55 SÖDERSTRÖM, SVEN, Från den sydsamiska ordboken 56

Summary: From the South Lappish dictionary 67 VÄSTERLUND, RUNE, och PETTERSSON, MARIE-LOUISE, Nils Ti-

bergs tryckta skrifter 1925-1980 73

Meddelanden och aktstycken/Notes and documents

BENSON, SVEN, En kurs i talspråksforskningens metodik . . . . 78 Summary: A course in the methodology of research into spoken

language 82

Juridiska och etiska problem i samband med talspråksundersök-

ningar 82

Summary: Legal and ethical problems in connection with inves-

tigations into spoken language 86

BJÖRKLUND, STIG, Ertse 'myrmalm' i Övre Västerdalarna. En järn-

terminologisk studie 86

Summary: Ertse 'bog-ore' in Upper Västerdalarna 90 DRUVASKALNS, INGA-LILLL, Kagghartsning vid ett svagdricks-

bryggeri 90

Summary: The resining of barrels at a small-beer brewery 92 NYMAN, ÅSA, Barnfoten, En egendomlig benämning på en måltid 93 Summary: Child's foot. A strange name for a meal 96

WIDMARK, GUSTEN, Sven Markgrens samlingar från Skelleftebyg-

den i ULMA 96

Summary: Sven Markgren's records from northern Västerbotten 98

Litteratur/Reviews

BENSON, S., Blekingska dialektstudier. II. Lund 1981. Anm. av

Claes Åneman 99

Summary: Dialect studies from Blekinge in Sweden. Reviewed

by C. Å. 102

BJÖRKLUND, A., & NORDLINDER, G., Visor & verser från haven

Sthlm 1980. Anm. av Agneta Lilja 102

Summary: Songs and poems from the seas. Reviewed by A. L. 104

REHNBERG, M., Hejarn borrar, släggan slår! Svensk folkdiktning kring arbetslivet. Sthlm 1980. Anm. av Marie-Louise Pettersson 104 Summary: Hejarn borrar, släggan slår! A book of Swedish folk

poetry of labour. Reviewed by M.-L. P. 106

TILLHAGEN, C.-H., Fåglarna i folktron. Falköping 1978. Anm. av

Agneta Lilja 106

Summary: The birds in popular beliefs. Reviewed by A.L. 108 Nyutkommen uralisk litteratur. Anm. av Tryggve Sköld . . 108

Summary: Recently published works on Uralic etymology. Re-

viewed by T.S. 112

Från arkivens verksamhet 1979-1980 113

Summary: From the annual reports of the institutes of dialect

and folklore research 1979-1980 113

Insänd litteratur/Works received 16.2.1979-31.1.1981. Av /By Rune Västerlund, Kerstin Mattsson, Marie-Louise Pettersson . . . 115

Swedish Dialects in the Midwest:

Notes from Field Research

By Folke Hedblom

Early Swedish COlonization in the Midwestern States

Swedish immigration to the Midwest began in the 1840s and 1850s. The best known of the first settlers is the Uppsala student Gustaf Unonius, who settled in the wilderness west of Milwaukee in 1841 (Unonius 1861-62). Most important by far was the group immigration of the Erik Jansonist sect to Illinois in the fall of 1846, when about I 000 persons arrived at the same time with about 500 more following during the next few years. They founded a religious-collectivistic colony called Bishop Hill in northwestern Illinois. Even before the Civil War several Swedes and their families settled in Iowa, Minnesota, Kansas, and Nebraska, but the bulk of them arrived in the years 1865-1880. After the Home-stead Act had been passed, and the war was ended, and severe crop failures had stricken Sweden in the years 1867 and 1868, emigration from Sweden increased considerably. By 1930 about 1.2 million Swedes had immigrated to the United States.

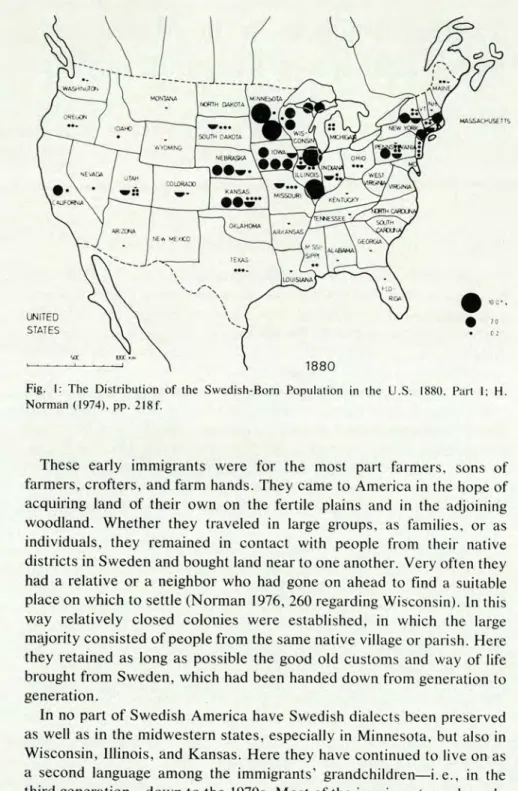

To a considerable degree these immigrants could retain their Swedish mother tongue as their everyday speech and pass it on to their children. As late as 1930 the U.S. census recorded over 600 000 Americans whose mother tongue was Swedish (Nelson 1943, 49). This is a significant number—almost 10% of all Swedish speakers in the entire world at that time. The majority of the immigrants settled in the midwestern and Great Plains states. In 1880 no less than 76.54% of all Swedish-bom n in the United States were living in this area, among them more than 21% in Illinois, 20% in Minnesota, 9% in Iowa, 5% in Kansas, 5% in Nebras-ka, 4% in Michigan, and 4% in Wisconsin (Norman 1976, 242). The proportions remained relatively unchanged in 1900, although the per-centage of Swedish-bom n had decreased, especially in Kansas.

Reprinted from Languages in Conflict. Linguistic Acculturation on the Great Plains. Edited by Paul Schach. Published by the University of Nebraska Press. Lincoln and London 1980.

UNITED

STAT ES C2

Sef

8 Folke Hedblom

Fig. 1: The Distribution of the Swedish-Bom Population in the U.S. 1880, Part I; H. Norman (1974), pp. 218f.

These early immigrants were for the most part farmers, sons of farmers, crofters, and farm hands. They came to America in the hope of acquiring land of their own on the fertile plains and in the adjoining woodland. Whether they traveled in large groups, as families, or as individuals, they remained in contact with people from their native districts in Sweden and bought land near to one another. Very often they had a relative or a neighbor who had gone on ahead to find a suitable place on which to settle (Norman 1976, 260 regarding Wisconsin). In this way relatively closed colonies were established, in which the large majority consisted of people from the same native village or parish. Here they retained as long as possible the good old customs and way of life brought from Sweden, which had been handed down from generation to generation.

In no part of Swedish America have Swedish dialects been preserved as weil as in the midwestern states, especially in Minnesota, but also in Wisconsin, Illinois, and Kansas. Here they have continued to live on as a second language among the immigrants' grandchildren—i. e., in the third generation—down to the 1970s. Most of the immigrants spoke only dialect. At the time of emigration their school education had been slight, and some of the oldest ones were probably illiterate.

Swedish Dialects in the Midwest 9

Beginning with the 1870s, when the mass emigration from Sweden set in, the stream of immigrants turned more and more to the cities. These immigrants found employment primarily as laborers in industry, in the mines, in lumber camps, and in railroad construction. To be sure, people from the same region of the home country tried to remain together in the cities also; but there people from various provinces—whether from the country or from the city—mingled with each other at their places of work, in social organizations, in churches, etc. The speech development followed the usual pattern for Swedish America: the most striking and distinctive dialect features were sloughed off rather early, within the first generation. Among their children, the second generation, who were bilingual and attended American schools, the position of Swedish was quickly weakened, even as the daily language of the home. And by the third generation Swedish had disappeared. Good examples of this are afforded by such cities as Omaha, Chicago, Minneapolis, etc.

The following presentation is concerned with bilingual Swedish speak-ers bom n in America. They will be referred to as second- and third-generation speakers. Immigrants who arrived in America before the age of fifteen will also be regarded as second-generation speakers. These people, who lived their entire lives in the country and belonged to the rural, or farm, population were in general not affected by the America-Swedish cultural propaganda, which strove for the retention of the Swedish language and a distinct Swedish way of life in America. They represented what Fishman has called "the little tradition level". None of the dialect speakers cited in the following has ever been to Sweden.

The Dialects in the Rural Settlements

It was in the ethnically homogeneous farming communities, more or less isolated from the linguistically "foreign" environment, that the neces-sary prerequisites existed that made it possible for the various Swedish dialects to continue to live their own lives, and it was there that they could remain the clearly dominant language far into the twentieth cen-tury. In these communities the homogeneity extended not only to Swed-ish language and traditions in general, but also to the traditions and speech of a specific province or even parish in Sweden.

The continuity and strength of tradition in the se settlements was often very strong. Even in the 1970s I met various farmers in Isanti and Chisago counties in Minnesota who still lived on the very farms their grandfathers had cleared from the wilderness in the 1850s and 1860s. If there were several sons in an immigrant family, the father often helped them clear the land for their own farms in the vicinity. Thus the family remained in the new community. Marriage outside the community was

10 Folke Hedblom

unusual. Similar conditions prevailed in the adjacent settlements in Burnett and Polk counties in northeastern Wisconsin until 1880 accord-ing to the historian Hans Norman (1976, 269). Here too the immigrants remained living for a very long time at the place where they had originally settled. Twenty years later 43-49% of them were still there. In that area the Swedes comprised the largest immigrant group (Norman 1974, 249 ff.).

In these settlements life was lived as long as possible according to the model of the self-contained economic society, which was characteristic for Sweden even during the middle of the nineteenth century. This ancient way of life was now reproduced in America, especially in forest regions, where nature was more similar to that in Sweden. Most of what was needed was produced or created by the people themselves. Money was in extremely short supply. It is surprising that the isolation of these farming communities lasted so long—until weil into the twentieth cen-tury. It was not until the advent of the automobile that it was broken. In 1962 a farmer in Lindstrom, Chisago County, Minnesota (bom there in 1900) discussed this matter in the Småland dialect (Hedblom 1975, 37): Still during my childhood, before the time when everybody got his own car, you heard only Swedish, mostly Småland vernacular, here in the streets of Lind-strom. That was the only speech you heard, you couldn't hear an English word in many many years (sic). Now it's the other way. If I start talking Swedish, there is not even a third of them who understand me! The other people think I am half mad! You could hear from the language from where the people came. There are great differences between the people down here and those who came from Vibo, north of Center City [just one to two miles distant]. We heard it also when they spoke English, they have a different accent. We seldom saw them. They came into town once or twice a week, that was all. Maybe they came from different provinces in Sweden. We called them Småland people, and Skåne, Öland, Östergötland, Västergötland people. But what those places [in Sweden] were like we had no idea about. But the Småland people around here, they spoke the same way, all of them.

Thus third-generation Americans identified each other on the basis of their Swedish dialects. The biblical "shibboleth" was in working order in the Småland settlement!

This permanence of settlement or high "persistence level" (Norman 1976, 266) of the inhabitants of the old Swedish farming communities was the first prerequisite for the preservation of the dialect. The second was the circumstance that people lived in extended families, in which grandma and grandpa lived their entire lives with their children and grandchildren—there were, after all, no old peoples' homes in those days. Since the grandparents spoke no other language except their native dialect, the grandchildren had to learn it in order to be able to communi-cate with them. In this way many families preserved the ability to speak

Swedish Dialects in the Midwest 11

Swedish even after English had otherwise become the language of everyday communication. When the old people died, the dialect fell into disuse. The third condition that contributed to the preservation of the dialect was the fact that the community was constantly supplied with new immigrants who came from the same dialect area in Sweden. If, on the other hand, such newcomers had lived in America for a considerable length of time among Swedes who spoke other dialects, their native dialect would have undergone a certain degree of leveling. This, in tum, contributed to a weakening of the position of the original settlement dialect. And when the stream of new immigrants from Sweden was almost completely cut off around the tum of the century, the position of Swedish on the whole was attenuated.

The Dialects of Sweden. Field Investigations in America

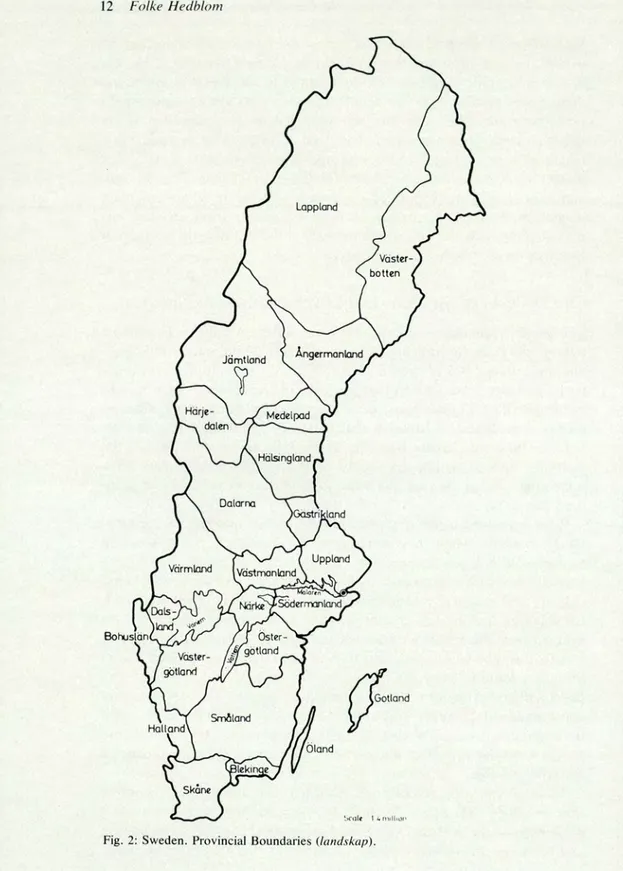

The Swedish language is split up into many different dialects. For almost a thousand years Sweden has been divided into 25 provinces (landskap)

and more than 2 000 State church parishes (socknar). In many of these parishes dialects are spoken that are quite distinct from those of neigh-boring parishes. Certain parish dialects, particularly in Dalarna, differ so greatly from Standard Swedish that outsiders find it difficult to decide whether they are actually Swedish. Many dialects are still in use as the everyday speech within the family or the village, though they have undergone change through the constantly increasing influence of Stan-dard Swedish.

What happened to these dialects during the second half of the nine-teenth century, when they were uprooted from their native soil and transplanted in a new environment side by side with a dominant foreign language and with other Swedish dialects that were also strange to them? Until 1962 practically nothing was known in Sweden about the Swed-ish language in America. In that year the first research expedition was sent out from the Institute of Dialect and Folklore Research, Uppsala. It was followed by new expeditions in 1964 and 1966. It was natural that in these expeditions emphasis should be put on the dialects and on the dialectcolored American-Swedish colloquial speech. Soon the program was broadened, however, to include American Standard Swedish. From the beginning it was clear that the undertaking was a salvage operation. It was essential to collect quickly the most varied and comprehensive material possible.

All in all over 500 voices were recorded with a combined recording time of almost 300 hours. Technically the recordings were made on a professional level with an experienced accoustical engineer as technician and driver of the specially equipped microbus that was brought along.

12 Folke Hedblom Lappland Väster-botten Jämtland Ångermanland Härje- dalen Medelpad Hälsingland Dalarna Gastr land

Varmkind Västmanland Uppland

Dals- land Bohuslan Närke Småland leren Södermanland Vaster-gotland Oster- i; gotland Gotland Halland Skåne Oland !,cult 1 nfilhop

t - -

-; - . C A N A D A

7-,

oc

n7,2-Argt1 v -t • Lake Fron n sa •—••-•••.—•-"e- 1,. `,_ • "'

rIallK Karlstad k ...., ,': -: e' 4.,„ 6

"Red Vask ish , , L"' kelliher / 4 tIt2t»

-

/---"

DAK OTA Bemidj i

Puluth

5T. L Ul5 ;Thok 1611 River

A A

Ni 1 5 5 0 U R 1

Smolan Sa" Enterprise TOPEKA ' alemsborYAssa r ia

alun • I-i ndsborg

Fremon •New Gottlana

Mc Ph e rson

-a MINNES 0 T A 1.1.11e," La,s,..,4 / die l_ake • Tia mora Car•bri4 in ddrom. Minneapolis 1 '• 0‘. S`-' rantsbung . • • siren 71,F.•ol1t1 Lake Trade Lake W I S CON SI N PAUL Holmes "fr"A.2'9•Alexan .•Kensington 5 DAKOTA 14, St romsbur

/Ok'te. LI htOLN Holdregeo. • «Punk .5.9014 \il A Boone SweileVaikey Madrid. DES MOINE5 aha -- 13rantlora oncor .a Swedes e,t;wed Rock Is1.3n4 Bishop 1.-411 63113 ILLINOIS e Wichita

Swedish Dialects in the Midwest 13

Fig. 3: Some of the Main Places in the Midwest States Where Tape Recordings of Swedish Dialects Were Made, 1962-66.

The recordings were made in situations as natural as possible, some-times several persons were recorded in informal conversation, and sometimes without the speakers' knowledge. It would have been desir-able (as was done with similar recordings in Swedish) to have an inter-viewer who spoke the same (or a similar) dialect as the informants, but this, of course, was not possible. To a certain extent this drawback was compensated for by the fact that the leader of the expedition had had direct experience for about thirty years with dialect speakers and envi-ronments in all of Sweden's provinces.

14 Folke Hedblom

The purpose of the expeditions was not exclusively linguistic. We had to use these opportunities to try to arrive at a broad, objective documen-tation of the speakers' life environment, that is, the actual connection between the language and the life of the people in the Swedish settle-ments. (A chart of these expeditions is found in Hedblom 1969, 100.) The author made supplementary investigations in Illinois and Minnesota in 1973 and 1976.

Surviving Swedish Dialects in Homogeneous Settlements:

Two Examples

A good example of an American-Swedish dialect that is very much alive in the third generation is the Hälsingland speech of Bishop Hill, Illinois. I reproduce here a short excerpt from a conversation I recorded there in 1973. I conversed with a woman, bom n in 1906, about life on the farm on which she and her sister had grown up.' Her mother had also been bom n in Bishop Hill as the daughter of a woman who had immigrat-ed with the Eric Jansonists in 1850. Her father had immigratimmigrat-ed at the age of ten with his parents from a neighboring parish in Hälsingland. In their parents' home she and her sister always spoke the Swedish dialect, the only form of Swedish they knew. In school they learned English, the language they used in speaking with their schoolmates, who liked to poke fun at their "funny" Swedish. The sisters themselves call their dialect "Bishop Hill Swedish", and they are aware of the fact that it is notfin, correct Swedish. Nowadays they use Swedish only when speak-ing with each other and with a few old friends—especially when the conversation turns to the old days—and in speaking to visitors from Sweden. Otherwise English has long been their everyday speech, even when speaking with their husbands and children. The children do not know any Swedish at all. Around 1935 all religious services in Swedish ceased in the only church in town (Methodist).

In the following she tells about helping their parents shock oats: Dåm sjacka (shocked) havra ... å vi földe mä förståss. Iblann så sätte vi åpp en sjack (shock) å då skulle vi sätta en tåpp (top) på den å så sa vi: »Ja, nu skulle vi marka (mark) den så vi visste åm den stog åpp tell dom tröska.» Moster Liva bruka säja »Dä var mejntingen (the main thing), dä.» Dä var mejntingen åm han stog åpp tell dåm tröska. Åm sjacken stog ... när ä regna ... å åm då blåsste hårt så blåsste den bundeln (the bundle) såm dåm sätte åppå, blåsste åv.

They shocked oats and we accompanied them, of course. Sometimes we put up a shock and then we had to put a top on it and so we said, "Now we should mark it so we can know if it will be standing till they start the threshing". Aunt Liva usually said, "That is the main thing". The main thing was that it remained

Swedish Dialects in the Midwest 15

standing until they threshed. If the shock was standing ... when it rained ... and if the wind was hard, the bundle on top blew down.

The dialect is easy to identify as that of the parish of Hanebo in southern Hälsingland close to the border of Gästrikland—the parish from which her grandmother emigrated in 1850. The dialect is close to the one I spoke as a child. Elderly people in southern Hälsingland who listened to these tape recordings were astonished at the genuine intona-tion of the dialect as weil as at its old-fashioned authenticity on the whole. The English and Standard Swedish elements do not disturb the general impression. The Standard Swedish words and phrases she knows were probably learned in church, where she and her sister were very active.

The foreign elements are quite modest in number. As even this short specimen shows, the English loanwords (in italics) are not numerous. The phonology, prosody, accents, vowels, and consonants are essential-ly those of the dialect. There is no English "brogue". Onessential-ly sporadicalessential-ly do such English phonemes as /r/, /1/, and /o/ intrude into Swedish words. In morphology the declensional and conjugational systems have been retained virtually undisturbed. Even loanwords are adapted to the mor-phology of the dialect. The main thing became mejntingen, the bundle

becomes bundeln, the shafts becomes sjäftene, shocked becomes

sjacka, etc. In contrast the old three-gender system is in a state of dissolution—a condition to which both Standard Swedish and English have contributed. The speaker often vacillates among all three genders. Sometimes the masculine predominates, but more often it is the Stan-dard Swedish nonneuter (utrum). In her lexicon the speaker has retained many words that have long since become obsolete in the original dialect, a circumstance that contributes strongly to the general impression of archaism. As is usually the case with immigrant tongues in America, a considerable portion of native vocabulary has been lost and replaced with borrowings from English (Haugen [1969, 74-97] speaks of the "great vocabulary shift"). In the syntax there are various forms of English interference such as are common in American Swedish in general.

This speaker is perfectly bilingual in American English and Hälsing-land Swedish. Her English is faultless, and there are few traces of an English substratum in her Swedish.2 She switches to English when, for example, someone injects a comment in that language into the conversa-tion. When her Swedish vocabulary is inadequate, she resorts to an English word in unchanged form. The English loanwords of the ordinary American-Swedish type that have been integrated into her Swedish in

16 Folke Hedblom

the great majority of cases follow the rules of the dialect in regard to phonology and morphology—as, for instance, in words like fence, field, porch, shock, store, stove (for additional examples see Hasselmo 1974 and Haugen 1969).

It should be noted, however, that the individual differences among conservative dialect speakers are significant. This becomes apparent when we compare this woman with another Hälsingland dialect speaker, from Isanti County, Minnesota. He also belongs to the third generation and is of the same age, having been bom n in 1903. He grew up on a farm in a settlement in which most of the families came from the same parish in northern Hälsingland, many as early as the 1860s. He too attended English-speaking schools and uses English for most of the day' s situa-tions, even when speaking to his wife, but his English reveals distinct traces of the phonology of his Swedish dialect. But his command of his dialect is substantially more certain and consistent than that of the Bishop Hill speaker. Phonology and morphology are well preserved, and even the three-gender system functions as it did in the original dialect. His dialect is the only kind of Swedish he knows, and Standard Swedish levelings are insignificant. The state of his dialect is so stable and dominant that he makes use of English terminology when his Swedish vocabulary is inadequate—for example, in speaking about technical matters. But he does not switch to English. The English words (with certain phonetically difficult exceptions) conform to the phonological, morphological, and syntactic patterns of the dialect. The following short example is taken from a conversation dealing with a picture of an old steam engine used for threshing in his younger days:

Då du starter injärn ... å drar på-n-här levvern, då engedjer n-här klöttjn . .. Du

revösjer rotesjn på jule hänne....A sö ä en annan revösjlevver då, söm du

tjentjer tajmninga hänne.3

When you start the engine and pull this lever, then this clutch engages. You reverse the rotation of this wheel. And then there is another reverse lever by which you change the timing here.

Only one noun (hjul `wheel') and one verb (draga 'pull') are Swedish. For the rest, only pronouns, auxiliary verbs, and adverbs are taken from the Swedish. As for the word tajmninga 'the timing', pronunciation, word formation, gender, and inflectional suffix are those of the dialect. The text shows how the speaker ingeniously makes maximal use of the English store of technical terms with minimal infringement upon the phonetic and morphologic patterns of his Hälsingland dialect. His appro-priation of English words is clearly different from the immigrant's desul-

3 The transcription here is very broad. A larger part of this recording is printed in Hedblom 1977, 56-62.

Swedish Dialects in the Midwest 17

tory "mixing". For such a transfer of words the speaker must be bilingual; but he is, as has been shown, a bilingual of a type quite different from the woman in Bishop Hill.

The truly dialect-homogeneous settlements, in which a single parish dialect is completely dominant as in the above two cases, are, naturally enough, in the minority. Of all of the recorded material homogeneous dialects comprise about five to ten percent. In the two cases here discussed the prerequisites for the retention of the Hälsingland dialect are especially favorable. The families from Hälsingland were numerous among the Eric Jansonists and they had arrived early. This put them into a socially advanced position. In regard to the Swedish settlements in Wisconsin Hans Norman (1974, 260) has demonstrated that it was those groups of immigrants who on the one hand arrived first and on the other hand were large in number who achieved a socially dominant position in the community.

These settlements in northeastern Wisconsin along the St. Croix River constitute a continuation of the Swedish colonization area on the west-ern side of the river in Chisago and Isanti counties in Minnesota. These two counties on the Chisago lake system northeast of Minneapolis make up the largest cohesive rural area in all of Swedish America. Nearly every farm on an area of 2 237 square kilometers was cleared and cultivated by Swedes. The first ones arrived in the 1850s, and as late as 1920 almost one-fourth of the total population were Swedish bom (Nel-son 1943, 190). Here dialects that had existed far apart in the homeland for the first time confronted each other on a rather large scale. Yet they were neither blended nor leveled out, but continued to exist side by side. People from the various provinces settled close together, and the perma-nence of these province and parish settlements was so strong and persistent that the author as late as the 1970s, when English had become almost exclusively the everyday 'speech within the family, could trace the dialect boundaries that run through the region between, for example, Småland, Hälsingland, and Dalarna and even between different Swedish parishes within the various provinces. The inscriptions on the grave-stones of the small burial grounds, which most often were churchyards, show that the first settlers on the surrounding farms came from closely circumscribed areas—parishes and villages—in Sweden. On some farms the dialects still exist, some of them surprisingly conservative, others leveled in the direction of Standard Swedish, with the usual influence from English. But the dialects have not become blended with each other. The fact that a large number of them were Baptists contributed to their cohesion, but there were also many Lutherans in the vicinity. I had similar experiences among the still more numerous Småland people in Chisago County and in the adjacent settlements in Wisconsin, on the

18 Folke Hedblom

eastern side of the St. Croix River, where the majority of the Swedish settlers had come from Västmanland and surrounding provinces.

In the question of the dialect-conservative settlements the people of the upper parishes of Dalarna occupy a special position. Their dialects, which differ sharply among themselves, are no doubt some of the most conservative in northern Europe. They were completely incomprehensi-ble for Swedish outsiders, and could be used only within a very small circle. But just as they had in Sweden, the American Dalecarlians also spoke a modified Standard Swedish. In 1966 we made recordings of the speech of second-generation people whose parents had come from the parish of Älvdalen. The settlement, founded in 1880, is near Mille Lacs Lake, Minnesota. The informants—twelve in number—conversed en-tirely in dialect. But in Bishop Hill the situation was quite different. Here the Dalecarlians were in the minority. It is reported that they frequently used their dialect as a secret language—for example, on the party telephone line. This aroused suspicion and stamped them as socially inferior, and therefore they gradually abandoned their dialect. Some of them are even said to have denied their Swedish origin.

While editing our recordings of speakers of conservative dialects we became aware of the fact that some of them retain linguistic features that long ago disappeared from the living dialects in Sweden. This holds true for phonetic, morphological, and syntactic features that until then had been known only from older literature. One of the dialects for which this obtains is the old city dialect of Stockholm (Hedblom 1975, 40).

Swedish Dialects in Heterogeneous Rural Settlements

In the large majority of cases no one dialect group was in such a strong position in its settlement that it could maintain its speech outside the family in a more or less unchanged form—aside from the usual English loans. This holds true especially for speakers of the second and third generation. As a rule the minority leveled out the most divergent fea-tures of their dialects in accordance with the speech norms of the majority, which came close to Standard Swedish, was perceived as being finare, and therefore enjoyed higher social prestige. There follow severäl illustrative examples.

I encountered a case of dialect confrontation that led to a change of dialect in Kimball, Minnesota. A farmer, bom on his farm in 1894, and his two sisters told me the following in Swedish (Hedblom 1975, 45): Father (bom 1852) came from northern Värmland in 1876 and mother (bom n 1861) from the province of Dalarna. When we were small, we always spoke the Dalarna dialect, mother's and her mother's language. Later on the family moved to this place, and we began school here, where all the children came from

Swedish Dialects in the Midwest 19

Värmland families. They laughed at us because we spoke Dalecarlian. So we turned to speaking the Värmland dialect like father, even within the family. But to grandma we always spoke Dalecarlian, the only language she understood. So we could speak three languages, Värmland, Dalarna, and English. It was easy for us to change language.

The brother, who had remained on the farm, now spoke only his Värm-land dialect and English. A VärmVärm-land dialect expert has assured me that this man's dialect is a pure, archaic north Värmland vernacular with no traces of other dialects except for the usual English loans. The sisters, who had been living in different Swedish-speaking areas in America, now spoke Standard American Swedish. They remember only individual words and phrases from their mother's Dalecarlian.

Such a change of dialect, of course, can take place only in childhood. This example sheds light on the question whether it is the father's or mother's dialect that prevails in the family. This usually depends on which dialect is spoken by the majority in the community and which enjoys higher social prestige. In those cases where the difference be-tween the dialect of the minority and that of the majority was so great as to make mutual understanding very difficult, or in cases where the minority was not certain that the dialect of the majority was "correct" Swedish or that it represented a reliable Standard Swedish norm, it lay near at hand to resort to a more radical expedient: one abandoned Swedish in favor of English, the language one had learned in school and whose social status was beyond question. The following case from Kansas is instructive.

In 1964, not far from the city of Enterprise (southeast of Abilene), we visited a Swedish colony that had been founded by immigrants from the province of Gästrikland in the 1860s. Most of them had come directly from Sweden, and they formed a very • close-knit community with little intermarriage at first. By now the community had dissolved. Agriculture in the vicinity had been streamlined, and the descendants of the settlers had moved away. But once each year they met at the old church for "clean up day"—to decorate the graves of their relatives—and we met them there just on that day. After we had conversed somewhat haltingly for awhile, the dialect of Gästrikland emerged. But a woman said in Swedish with an accent that betrayed that she did not have the same origin as the others: "Father came from the island of Gotland and mother from Östergötland. Thus they had quite different dialects. When we people spoke, the other people laughed at us. So we went over to English. The north Sweden (Gästrikland) people—they thought they knew how to speak, but we didn't. Theirs was right, but ours was not." The Gästrikland dialect had a higher level of prestige. It was not only the speech of the compact majority, it was also doser to Standard Swedish,

20 Folke Hedblom

which has its historical origin in the neighboring provinces around Stockholm.

But settlements of this kind, where there is a majority with a relatively uniform dialect, were, to the best of my knowledge, unusual in the Great Plains states of Kansas and Nebraska and even in Iowa. This is because of the different character of Swedish immigration in these states. Most immigrants did not come here directly from Sweden; rather, they had lived for a longer or shorte,r period of time in Illinois, especially in Chicago and Galesburg or iå other rather large cities, together with people from various parts of Sweden, and there they began to level their dialects. The great majority of the earliest Swedish immigrants to Kan-sas came in groups organized by colonization companies in Illinois at the close of the 1860s. Even though to a certain degree they remained together according to their places of origin in Sweden, and even though relatives and friends from there joined them later, no settlements devel-oped here that were as unified in regard to language as those in Minneso-ta.

In the largest Swedish concentration in Kansas, in the center of the state, around the little town of Lindsborg south of Salina, one can observe how children and grandchildren of people from Värmland, Västergötland, Småland, Blekinge, etc. are predominant at this or that place, but none of them were dominant to such a degree that the preservation of their own dialects was a matter of course. Quite early, too, there seems to have been extensive intermarriage between people whose parents were from different provinces and even marriage with non-Swedes. The speech of most of those we met in the 1960s had undergone leveling. In New Gottland descendants of immigrants from the provinces of Västergötland and Blekinge were predominant. Various features of the Västergötland dialect have been preserved, but of the Blekinge dialect scarcely more than a few weak traces can be heard in spite of the fact that the immigrants from this province on Sweden's south coast were quite numerous. Among the immigrants themselves this dialect seems to have had low status, even among those who spoke it. Here are several examples. A Mr and Mrs Berg were both horn in or near New Gottland of parents who immigrated in the 1860s and 1870s from Blekinge. The speech of both is leveled out. Mr Berg's parents always spoke Blekinge dialect, but he himself said (in Swedish), "I think the Blekinge dialect is one of the worst kinds of speech in Swedish", and he took pains even when young to speak as "fint" as possible (Am 194).4 But opinions regarding what was "fint" varied. In the community

4 The abbreviation Am designates the series of tape recordings from America in the

Institute of Dialect and Folklore Research (Dialekt- och folkminnesarkivet), Uppsala, Sweden.

Swedish Dialects in the Midwest 21

of Assaria, where the Blekinge people formerly were the dominant group, it was felt that the Småland people spoke "fint" (Am 205).

In Lindsborg a man whose parents had been among the numerous immigrants from Värmland in 1869 maintained that his wife's speech was ugly (fult). "It has too much Blekinge in it", he said in Swedish. "She does not speak Swedish fluently." And he complained about both her pronunciation and her vocabulary, which deviated from his own normal Värmland speech (Hedblom 1975, 48). Sweden's southernmost dia-lects—those of Blekinge, Skåne, and southern Halland—had low status. They differ sharply from Standard Swedish and are closer to Danish. Nowhere in Swedish America have I found more than remnants of dialects from Skåne, Blekinge, or southern Småland among second-generation speakers.

In Boone, Iowa, I met a ninety-six-year-old widow who had emigrated from Småland with her parents at the age of two. She had lived her whole life among Swedes in Moigona, Swede Valley, and Fort Dodge. Her speech was still colored somewhat by her native dialect (Am 227). But she said she had always been ashamed of her Småland speech especially when she heard "norrlänningar" speak, i.e., persons whose dialects are closer to Standard Swedish. A similar attitude was ex-pressed by a ninety-year-old Småland immigrant in Wisconsin. He pat-terned his speech on that of the Västmanland majority, to which his wife and her parents belonged (Am 242). The dialects of Västmanland are very similar to Standard Swedish.

In Nebraska, too, we found the same negative attitude toward their native dialects among people of southern Swedish extraction. A ninety-two-year-old woman in Funk, not far from Holdrege, where she was bom, related that in her youth she had spoken like her mother and her mother's mother, who had come from Skåne. But after she had married a man from central Sweden, he removed (plockade bort) most of the dialect from her speech. Her Swedish was now strongly leveled. And she added that most speakers were now so intermingled (så blandade) that they had been forced to level out their speech. Now the family language was predominantly English.

In Nebraska the dialects clearly were in a weak position among Swedish speakers right from the beginning. The Swedes were certainly numerous; in 1900 the Swedish-bom n and their children numbered about 74 000 (Nelson 1943, 285). The greater number of them were farmers, for the most part concentrated in about ten settlements in the regions around Axtell-Holdrege, Stromsburg-Swede Home, etc., in the eastern half of the state. But many of the immigrants had not come directly from Sweden, but had lived among Swedes in other parts of the United States before settling in Nebraska, whereby their dialects bad been leveled out.

22 Folke Hedblom

That Swedish died out so early here in comparison with states such as Minnesota, Kansas, and Texas, was probably due to the fact that immi-gration directly from Sweden came to an end relatively early, at the beginning of this century.

In regard to Iowa one can observe that the Swedes there were a mobile population, so that that state often served as a transition area for immigrants who continued on to other states. Among the Swedish speakers recorded in 1964 in the old settlements in the vicinity of Boone and Des Moines the dialects had been leveled out. A powerful leveling factor in this connection was no doubt the coal mining industry, which employed many Swedes from various places in Sweden.

But even in these states, especially in Kansas, we encountered several cases of weil preserved dialects among third-generation speakers in "mixed" settlements. This was true of families who still lived on the farm that grandpa and grandma had cleared and where the feeling for family traditions was especially strong and lively (Hedblom 1975, 49).

The second-generation dialect speakers whom we met in the Dakotas had strongly leveled speech. This was what one should expect. Immigra-tion there was, on the whole, of late date and secondary; to a large extent the settlers came from Minnesota and other states.

When dialects from various provinces in Sweden came in contact with each other in such secondary settlements it was not the present major-ities that came to dominate the language. More important were people's attitudes toward the various dialects. People tried to model their speech on the dialects which had the highest social prestige, those which one perceived to be closest to Standard Swedish and were spoken by people from central and northern Sweden, for example, Gästrikland and Väst-manland. A third-generation Hälsingland speaker in Chisago County, Minnesota, told us how provoked he'was when a Småland speaker from the adjacent settlement, where the Småland people formed a strong majority, addressed him in his dialect, characterized by diphthongs and a uvular r. "I answered him in English!" he said. That he should have modified his own dialect was obviously out of the question!

Dialects in America and in Sweden.

Swedish Dialects and American English

A mixing or amalgamation of different Swedish dialects in the second and third generation that might have led to the formation of a composite dialect (Ausgleichsmundart) like Pennsylvania German is not to be found in our recordings except in individual cases in a few families: The clearest case of this occurred in Bishop Hill, and 1 have given a very

Swedish Dialects in the Midwest 23

brief report of it in Studies for Einar Haugen (1972, 293). The individual in question is a woman with a Småland and Västergötland background who in the 1920s married into a family from Gästrikland, in which four generations lived together. In order to make herself understood by the oldest generation (great grandpa and great grandma), she had to intro-duce both words and pronunciation from their dialect into her own speech. But after the death of the old people, she and her husband have very seldom spoken Swedish, and their children do not speak Swedish at all. It seems safe to assume that the children—in case they had taken over their parents' language—would have followed their father's dialect, which is fairly close to Standard Swedish rather than their mother's "mishmash".

Thus it can be stated without hesitation that the American-Swedish dialects that were not leveled maintained their identity to the end—to their impending annihilation, which will accompany the disappearance of the third generation. (The youngest third-generation speaker recorded by us was bom in 1921.) The salient features of grammar and lexicon that make possible an immediate identification of the home province (and sometimes also the parish or even the village) have been preserved by those speakers who were characterized above as conservative. What distinguishes the American-Swedish dialects from the original ones (as we know them from recordings of the late 1800s and the 1900s) is, naturally enough, the strong impact of English, not least of all the syntactic one, together with the loss of significant parts of the vocabu-lary that became irrelevant in America. When one plays recordings from America for older dialect speakers in the original homelands, the usual reaction is: "Oh, my, it sounds as though grandpa had returned! Only a very old person can speak like that." The English element does not detract from the total impression. It is interesting to observe that the conservative features—primarily lexical and inflectional—that have been preserved in American-Swedish are different from those that have been retained by the most old-fashioned among the dialect speakers in the home regions of Sweden. In Sweden it was primarily those words and forms that deviated most markedly from Standard Swedish that disappeared and were replaced by correspondences from the standard language. In America such words and forms could be preserved, for here there was no reliable standard spoken Swedish with which the dialects could be compared. Words and forms such as kräkene 'the cattle',

skonene 'the shoes' , blistra 'to whistle', skärva 'pull a person's hair',

dömpe '[has] fallen', and the like in Bishop Hill Swedish have been given up in Sweden. In such cases the difference between dialect speech in America and in the places of origin was brought about by the language development in Sweden. Similar observations have been made by sever-

24 Folke Hedblom

al scholars regarding German as spoken in America (Paul Schach 1958, 201).

There is another interesting difference between Swedish dialects in the home country and those I have recorded in America. In Sweden many words are common to both the dialects and the standard language—loan- words that have been so completely adapted to the phonology and morphology of the dialects that they seem natural even to older dialect speakers. Many of these words, such as konstig `queer' and boskap `cattle', are unknown to Swedish dialect speakers in America. The reason for this is probably that these words had not gotten a foothold in the dialects at the time of emigration, the 1850s and 60s. The absence of such words from the dialects in America can also be regarded as a kind of conservatism.

This is easily overlooked by people in Sweden when they listen to American Swedish. When the Swedes in America felt the need to express concepts like konstig and boskap, and when the various dialectal terms were felt to be out of fashion or unusable, they simply supplement-ed their word stock from English with crazy and ca ((le (more examples in Hedblom 1978). The problem of why one in American Swedish exchanged words that are common and practicable in Standard Swedish in Sweden for English loanwords cannot be solved without taking into account the dialects that lie behind the Swedish-American's more or less dialect-colored speech. This, of course, holds true especially for the many Swedish-speaking Americans who cannot read Swedish.

In editing the field recordings from America we also discovered that it is often difficult to distinguish between old dialect and English words and phrases as we heard them from the loudspeaker. Often the dialects, especially those from central Sweden, are closer to English than to Standard Swedish. This can hold true for phonetic, morphologic, lexical, and syntactic details. Sometimes it is a maner of a chance coincidence, sometimes of features of older language periods that have been pre-served on both sides. Examples: dial. marka 'to mark' (St. Sw. märka), dial. lika 'to like' (St. Sw. tycka om), dial. vara bråttom 'to be in a hurry' (St. Sw. hava bråttom), etc. Similar observations on German dialects in the United States have been made by Paul Schach (1954-55, 222).

Circumstances such as these show that a thorough knowledge of the dialects in the homeland is necessary when we endeavor to distinguish in emigrant tongues between changes caused by the impact of the language of the new country and the linguistic heritage that the speaker or his forebears brought from the old country.

The Swedish language that the children and grandchildren of the rural farm immigrants to America spoke in the 1960s and 70s reveals a spectrum of grammar, vocabulary, and modes of expression that extend

Swedish Dialects in the Midwest 25

all the way from a conservative dialect with an essentially unchanged structure and a restricted number of easily identified English elements to a strongly leveled American Standard Swedish of the same type that is spoken in cities like Chicago and Minneapolis, a "koine" with shifting dialectal coloring. Both the conserving and the changing factors are to be found above all in social and cultural conditions. These factors are, of course, based also to a significant degree on the speakers' own attitudes toward their dialects; here the personal disposition—rearing and family tradition—plays an important role.

That the Swedish language in America was doomed to die out with the disappearance of the second and third generation was not merely a result of the steady pressure exerted by English and by the prestige-laden culture that sustained that language. It also resulted from the circum-stance that the Swedish language was largely split up into many different dialects and from the lack of a recognized Swedish colloquial norm that could constantly make itself felt among those who lived on the plains and in the woodlands outside of Swedish cultural centers like Chicago and Minneapolis, and who thus lived on "the little tradition level".

[Translated from the Swedish by Paul Schach]

References

Hasselmo, Nils 1974. Amerikasvenska. En bok om språkutvecklingen i Svensk-Amerika. Lund 1974.

Haugen, Einar 1969. The Norwegian Language in America. A Study in Bilingual Behavior. Second edition 1969 by Indiana University Press.

1972. "Studies for Einar Haugen. Presented by friends and colleagues." The Hague 1972. Janua Linguarum. Series Maior, 59.

Hedblom, Folke 1969. "Swedish Speech in an English Setting: Some Observa-tions on and Aspects of Immigrant Environments in America." In Leeds Studies in English. New Series. Volume II. 1968. Leeds 1969.

1975. Svenska dialekter i Amerika. Några erfarenheter och problem. In

Kungl. Humanistiska Vetenskaps-Samfundet i Uppsala. Årsbok 1973-1974. Uppsala 1975.

Amerikasvenska dialektproblem. In Dialectology and Sociolinguistics. Es-says in Honor of Karl-Hampus Dahlstedt 19 April 1977. (Acta Universitatis Umensis. Umeå Studies in the Humanities. 12.) Umeå 1977.

1978. "Amerikasvenska dialekter i fonogram. Hanebomål från Bishop Hill, Illinois." Svenska Landsmål I Swedish Dialects 1977. Uppsala 1978. Also in:

Skrifter utgivna genom Dialekt- och folkminnesarkivet i Uppsala. Ser. A: 15. (Title "En hälsingedialekt i Amerika. Hanebomål från Bishop Hill, Illinois". Uppsala 1978.)

Nelson, Helge 1943. The Swedes and the Swedish Settlements in North America 1—II. (Skrifter utgivna av Kungl. Humanistiska Vetenskapssamfundet i Lund

26 Folke Hedblom

Norman, Hans 1974. Från Bergslagen till Nordamerika. (Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Studia Historica Upsaliensia 62.) Uppsala 1974.

1976. "Swedes in North America." In Runblom-Norman: From Sweden to

America. A History of the Migration. (Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Studia

Historica Upsaliensia 74.) Uppsala 1976.

Schach, Paul 1954-55. "Die Lehnprägungen der pennsylvaniadeutschen Mund-art." Zeitschrift fiir Mundartforschung 22. 1954-55.

"Zum Lautwandel im Rheinpfälzischen. Die Senkung von kurzem Vokal zu a vor r-Verbindung." Zeitschrift fiir Mundartforschung 26. 1958-59.

Unonius, Gustaf 1861-62. Minnen från en sjuttonårig vistelse i nordvestra Ame-rika. 1—II. Uppsala 1862. (English translation. "A Pioneer in Northwest America 1841-1858." Edited by Nils William Olsson. 1—II. Swedish Pioneer Historical Society. Chicago, Ill.)

Måse, possa och sporr

Om

ord på gammalt ör, ös

Av Karl Axel Holmberg

Inledning

Vårt nuvarande skriftspråk bygger av historiska skäl på den uppsvenska språkformen men har också åtskilliga inslag av sydligare ursprung. Så är bl. a. fallet vid de en gång kortstaviga, under sin utveckling från forn-svensk till nyforn-svensk tid stavelseförlängda orden.

Frågorna kring stavelseförlängningen, förhållandet riksspråk — dialekt och skriftspråkstradition — dialekt är nära förknippade med namnet Bengt Hesselman. Denne insåg tidigt dialekternas, särskilt uppländskans och de centralsvenska dialekternas, betydelse för förståelsen av riks-språkets utveckling. Metodiskt var han därvid nydanande i det han utgick från dialekterna, inte från fornsvenskan. Han visade också hur dialektalt färgade författarna ännu på 1500- och 1600-talen var. Hessel-man kunde vidare tidigt formulera de regler som gäller för förlängningen av den korta rotstavelsen. Det gör han redan i sin första skrift, Skiss öfver nysvensk kvantitetsutveckling, i Språk och stil 1, 1901; jfr s. 23. Jag citerar dock här vad han skriver i Kritiskt bidrag till läran om nysvenska riksspråket, i Nordiska studier tillegnade Adolf Noreen (Upp-sala 1904): »De nuvarande, särskildt medelsvenska, dialekternas till-stånd i fråga om kvantiteten År i hufvudsak följande: kortstafviga ord, som innehålla a eller ä i stamstafvelsen ha i alla medelsv. dialekter — och för öfrigt i de allra flesta svenska dialekter — genomgående undergått vokalförlängning: fsv. tåk > tåk, bra > bra. Men om stamvokalen är i,

9, å, ö,

gå de olika dialekterna i sär. Vi ha dels i stor utsträckning bevarad korthet och förlängning af följande konsonant, dels vokalför-längning såsom vid ord med a, ä. Det förra förekommer i synnerhet i uppländskan (med undantag af Roslagen), i olika grad på skilda håll, enligt regler, som växla från det ena mindre området till det andra, men vidare också i Mälardialekten d. v. s. i den eller de dialekter —upp-ländska och sörmupp-ländska — som talas i bygderna omkring Mälaren.

28 Karl Axel Holmberg

t, men äfven af s och r, i mindre grad af öfriga konsonanter (mest i n. Uppland). Den torde också vara något mer utbredd i sådana ord, där vokalen är urspr. (9?), något mindre, där den varit å (å?). Någon olikhet i fråga om valet af de båda alternativen — vokalens eller konsonantens förlängning — mellan en- och tvåstafviga former (sluten och öppen staf-velse) är hittills ej med säkerhet konstaterad. — I de öfriga medelsvenska dialekterna, till hvilka jag närmast räknar den egentliga sörmländskan (i Södermanland med undantag af Mälartrakterna och Södertörn), närkis-kan och östgötsnärkis-kan synes vokalförlängning i kortstafviga ord vara genomgående — oberoende af vokalens eller konsonantens beskaffenhet. På liknande sätt förhålla sig de flesta andra svenska dialekter.» (S. 378 f.) Hesselman ställer också upp generella regler för stavelseförlängning-en. Hans synsätt i hithörande frågor har blivit vägledande. Reglerna för stavelseförlängningen ovan accepteras bl. a. av Wessen, Svensk språk-historia 1, § 78. Men citatet innefattar i själva verket en uppränning till ett stort forskningsprogram. Hesselman själv utvecklade temat i flera skrifter, särskilt i De korta vokalerna i och y i svenskan (UUÅ 1909). Kvar var sålunda å och ö och 1924 kom också i Hesselmans efterföljd två avhandlingar om dessa vokaler, Torsten Bucht, Äldre u ock o i kort stavelse i mellersta Norrland (SvLm B 22), och Folke Tyden, Vok. u ock o i gammal kort stavelse i upp- ock mellansvenska folkmål (SvLm B 23). År 1970 följde en avhandling av Claes Åneman, Om utvecklingen av gammalt kort i i ord av typen vidja i nordiska språk med särskild hänsyn till svenskan (Uppsala 1970). Åneman behandlar väsentligen subst. mid-ja, smedmid-ja, vidmid-ja, fittje, -a och verben fittja och vittja. De dialektgeogra-fiska framsteg som skett sedan de nämnda avhandlingarna skrevs är i Ånemans arbete väl tillvaratagna.

Nyligen har ytterligare en avhandling ventilerats om gammal kort stavelse, nämligen om ord där ö följts av kort r eller kort s: Sven Pihlström, Kortstavighet och stavelseförlängning, Hur några av de gamla kortstaviga orden erhållit sin form i svenskt riksspråk (Uppsala 1981; Acta universitatis Upsaliensis, Studia philologiae Scandinavicae Upsa-liensia, 16).

Presentation av Pihlströms avhandling

Som framgår av titeln tar Pihlströms avhandling sikte på riksspråket. Detta har i ord där ö följts av kort r eller kort s ibland uppsvenska former som i mosse, borr, ibland mellansvensk-götiska som i påse, spår etc. »Beror det kanske på att de olika ordens former har haft olika stor utbredning i dialekterna? Har för övrigt varje ord sin egen enskilda historia, eller finns här några samband av betydelse? Vad får sägas vara en följd av rena tillfälligheter?» (S. 9.)

Måse, possa och sporr 29

Att besvara frågorna ovan får väl sägas vara avhandlingens syfte. Metoden framgår av följande citat: »I denna avhandling skall orden på

ör, ös --- göras till föremål för dels en dialektgeografisk och dels en historisk undersökning» (s. 9).

Inledningsvis preciseras de ord det är fråga om. S. 13-35 följer den dialektgeografiska undersökningen och dess resultat, s. 36-80 den histo-riska undersökningen och s. 81-118 materialsamlingar till den histohisto-riska undersökningen. Mera härom nedan.

Avhandlingen är alltså kort. Ordhistoriska undersökningar brukar vara utrymmeskrävande.

I det följande skall Pihlströms avhandling skärskådas. Vad jag anför återgår i huvudsak på min opposition som fakultetsopponent vid Uppsa-la universitet den 16 maj 1981.

Vilka ord behandlas?

S. 12 i avhandlingen anger Pihlström de riksspråksord som återstår efter det att han gjort åtskilliga uteslutningar för att »få materialet så enhetligt och relevant som möjligt» (s. 10). Det är or-orden borr, borra, fur — fura, fåra, gorr, skåra, sporre, sporra, spår, spåra, os-orden bloss, blossa, boss, dråse, dråsa v., frossa s., mosse, -a, påse. (I avhandlingen tas os-orden först utom i materialsamlingen.) De följande kartorna tar emellertid inte med verben, dvs. blossa, borra, dråsa, sporra, spåra. Ett verb fåra tas upp först i materialsamlingen. På en karta tillkommer ett

får s. 'fåra'. I den historiska undersökningen medtas verben borra, sporra, spåra samt skorra — skåra. Där tillkommer också ett ord moss.

Verben blossa och dråsa saknar helt behandling. Det är svårt att inse vilka principer förf. följt. Tre ord, snor, dåsa och flåsa, tas inte med — som det tycks mig på tämligen svaga grunder; se s. 11. Ordet frusen

saknas, likaså bosa (ner), Tyden s. 113, morron, dens. s. 111 f., krossa,

dens. s. 115. (Förteckningar över hithörande ord finner man utom hos Bucht och Tyden i Noreen, Vårt språk 3 s. 117 ff.)

Den dialektgeografiska undersökningen

Pihlströms dialektgeografiska undersökning utgörs i själva verket bara av kartor. Karteringen avser endast att »i de centralsvenska dialekterna fastställa kvantitetsförhållandena» i de undersökta orden på ör, ös (s. 13). På kartorna är sålunda symboler för bevarad kortstavighet, konso-nantförlängning och vokalförlängning inlagda. Det karterade området är Uppland, Södermanland, Närke, Västmanland, Dalabergslagen, Gästrik-land och ÖstergötGästrik-land. Det centralsvenska området omfattar sålunda inte hela sveamålsområdet. Hälsingland, som inte direkt behandlas i

30 Karl Axel Holmberg

Buchts avhandling, borde ha tagits med, likaså givetvis nö Småland och Öland som ju räknas till sveamålen därför att sveamålsdrag påträffas även där. Att förf. skyggar för dalmålen må vara förståeligt men synes inte vetenskapligt motiverat. Förf. gör ytterligare inskränkningar. »Framför allt har jag --- velat bestämma de geografiska gränserna mellan den uppsvenska konsonantförlängningen och den mellansvenska och götiska vokalförlängningen» (s. 13). Slutligen blir det Södermanland som förf. inskränkeiintresset till, och där Selaön (»Sela»), Mörkö, Näshulta och Sorunda (s. 18-20). Någon materialsamling som redovisar var orden anträffats samt upptecknare, uttal, betydelsenyanser, varia-tion och andra fakta av betydelse för den källkritiska granskningen tillhandahålls ej. Det är skada, ty välgjorda materialsamlingar har bestå-ende värde. Det är väl nästan aldrig självklart hur förhållandena gestaltar sig utanför ett undersökt dialektområde; åtminstone hade översiktliga beskrivningar varit på sin plats.

I det inledningsvis lämnade citatet angav Hesselman det område, som då, i dialektforskningens barndom, var känt som konsonantförlängnings-område. Pihlström anser att kartläggningen visar följande: »Centrum i området med konsonantförlängning av ör- och ös-orden är Uppland med undantag av sydöstra delen. Härtill ansluter sig östra Västmanland och sydöstra hörnet av Dalarna. Södra Fjärdhundraland i Uppland, östligaste Västmanland och till dels Folkärna i sydöstra Dalarna bildar ett kortsta-vighetsområde inne i västra delen av konsonantförlängningsområdet. Inom det centralsvenska dialektområdet i övrigt är stavelseförlängningen realiserad som vokalförlängning. Detta område omfattar alltså sydöstra Uppland, Södermanland, Östergötland, Närke, mellersta och västra Västmanland, större delen av Dalabergslagen och hela Gästrikland» (s. 16).

Detta resultat förefaller till en del uppseendeväckande. Det stämmer emellertid inte med den bild kartorna ger. Ett ord som t. ex. boss har belägg i Roslagen, i södra delen av mellersta Västmanland och i nö Södermanland. (Området i Södermanland skall vara större än vad kartan anger, jfr nedan.) Även borr, får, fåra, mosse, skåra, spår har större utbredning vad gäller de konsonantförlängda formerna. Fura med -rr-har mycket liten utbredning. Bäst stämmer beskrivningen i fråga om dråse, gorr, påse.

Anledningen till att text och bild inte stämmer torde vara att Pihlström anser att belägg utanför det angivna området måste underkännas. For-merna med lång konsonant är riksspråkspåverkade. Det kan dock inte gälla vid får, fåra, skåra, spår. Han anser f. ö. att orden »borr, borra, fura, får, fåra, gorr, skåra, spår, spåra, boss, dråse, mosse (mossa) och påse har bibehållit sina genuina former i dialekterna ända in i vår egen tid

Måse, possa och sporr 31

trots århundradens ordspridning och skriftspråkspåverkan» (s. 15). Det förefaller självmotsägande. En motsägelse är det egentligen också att beläggen, trots att de underkänns, är inlagda på kartorna. Förf. har väl fått tillgripa en sådan nödlösning därför att ingen materialsamling läm-nas.

Pihlström söker ge bevis för att gränsen för de konsonantförlängda formerna är den angivna i söder (Västmanland lämnar förf. därhän, jfr ovan).' Han skriver: »Översiktliga undersökningar av de mellansvenska dialekterna ger inte mycket stöd åt en föreställning att kortvokaliska former har gått längre söder ut i andra fonemkombinationer än ör och ös» (s. 18). Han anför t. ex.: »Däremot heter det bek i Östergötland och Närke. (Av 23 belägg från Östergötland är 21 på bek och 2 på beck, av 19 belägg från Närke bara 1 på beck.) Även på de flesta håll i Södermanland heter det bek — av 19 belägg 12 på bek och 7 på beck — och bek finner man redan i den nordligaste delen av landskapet (i Tumbo och Vansö t. ex.). Arvidis former och dialektformen bek tyder på att formerna bek, skep, spet, veka och förmodligen också heta är ursprungliga i Söderman-land. Detsamma gäller säkerligen även för Närke» (s. 18f.). Formen vicke i Östergötland vållar dock besvär: »Tydligen kvarstår ... voka-lens korthet, i varje fall i vicke, såframt den inte är en följd av riksspråks-påverkan» (s. 19).

Enligt förf. tillhör »ingen del av Södermanland det uppsvenska kon-sonantförlängningsområdet » (s. 19). »Sörmländska belägg på konsonant-förlängda former som inte tillika är riksspråkliga är det ont om i Hessel-mans bok» (dvs. i och y) (s. 19). Hans egna konsonantförlängda belägg från Södermanland överensstämmer med riksspråket. »Vart Sorunda hör i dialektalt avseende framgår inte av mitt material», skriver förf. »Formerna forra och sporr på Sela och skorra i Näshulta visar dock att det uppsvenska konsonantförlängningsområdet ligger nära» (s. 20).

Pihlström gör alltså rent hus med åtskilligt dialektmaterial och med de bästa dialektforskare. Fullt så enkelt är det väl ändå inte. Dialektmate-rialet måste samlas, ställas upp och värderas. Avgörande är inte antalet belägg utan om skäl kan anföras för att en form får antas vara genuin, rätt uppfattad osv. Arvidis skrivningar bevisar inget om hela Söderman-land — och Närke? — utan väl endast att hans eget mål hade en del variation eller att han kände till en del sådan, närmast från Strängnäs vid 1600-talets mitt. Ty&n har stort förtroende för sitt material, jfr s. 39. Hesselman skriver om målen i Södermanland: »Andra uppsvenska ka-raktärer uppträda utom i Södertörn också i större eller mindre utsträck-ning i norra och särskilt nordöstra delen av sörmländska fastlandet.

I Jfr om detta landskap Geijer-Holmkvist, Några drag ur Västmanlands språkgeografi s. 4ff., i SvLm 1929 (h. 188).

32 Karl Axel Holmberg

Längre mot väster och söder inom landskapet avtaga de så småningom, och de flesta upphöra alldeles längs en linje eller ett bälte, som löper snett genom landet med en bukt mot öster i huvudsaklig riktning nord-väst-sydost från mälarstranden väster om Strängnäs ned till ett stycke väster om Trosa; närmast havet gå de ännu längre mot söder ...» (Södermanlands folkmål, i Sörmlandsboken, En skrift om hembygden, Sthlm 1918; s. 80f.). Bland drag i detta nordöstliga område anger Hessel-man »uppsvensk kvantitet i t. ex. tom, tima, skråma med långa vokaler eller skott, tenn, lock, droppe, spårr o. dyl. ...» (s. 81). (Vicka finns också i Södermanland, jfr ibid. s. 79.) Torsten Ericsson menar att de kortstaviga med vokalförlängning utgör »ett bland de mäst betydande kännetecknen för södra-västra gentemot det övriga sdml., dock i olika omfattning» (Grundlinjer s. 74; jfr s. 79). — Dialektinsamlingen hade nära nog bara börjat när Hesselman skrev sina grundläggande arbeten i början av seklet. Ett omfattande, ovärderligt material har kunnat insamlas sedan dess. Det duger långt.

Tre ord, bloss, frossa och sporre, har avvikande utbredning av de konsonantförlängda formerna (kartorna s. 22, 25, 34). Förf. anser att bloss och frossa var »ovanliga ord med dåligt fäste i allmogespråket. De långkonsonantiska former som upptecknarna har funnit i dialekter med vokalförlängning måste vara avhängiga av lån eller påverkan från riks-språket» (s. 16f.). »Bloss och frossa var förmodligen ingenting som människor använde respektive hemsöktes av i vardagslag» (s. 17).

Förf. borde ha gjort en saklig utredning. Redan av beläggen i ULMA framgår emellertid att man kunde fiska kräftor vid bloss, att man hade tredjedagsfrossa, annandagsfrossa och vårfrossa. Det stöder väl inte Pihlströms åsikt. Betr. sporre hänvisar jag till Tyd&I s. 113. Det skulle föra för långt att här göra den undersökning Pihlström underlåtit.

Kartorna

Förf.:s material för kartläggningen är (enl. s. 21) uppteckningar på sedeslappar i ULMA, typordlistor (»typordslistor») och Hesselmans Upplandsordbok ibid., Envalls, Grips, Isaacssons, Schagerströms, Tise-lius' och Ty&ns kända framställningar. Det förefaller vara litet dialekt-material och få monografier. Västmanlandsordboken och Dalabergslags-ordboken, som inte är i sedes, har väl använts? Förf. har tydligen avstått från ortnamnsarkivets dialektordssamling. Eftersom endast kartan an-vänts för redovisning av dialektmaterialet kan inte t. ex. Herweghr infly-ta, eller t. ex. hänvisningar till Ty&n, Bucht, Torsten Ericsson, Borg-ström m. fl. förekomma. Så gammalt dialektmaterial som Herweghrs, eller äldre dialektmaterial som t. ex. Gustaf Ericssons eller Grills, måste ju utgöra värdefullt stöd vid överväganden om äkta eller oäkta. (Torsten