Master’s Thesis Malmö University

30 ECTS credits Health and Society

Public Health Programme 205 06 Malmö

Health and Society

SUSTAINABLE

BUILDINGS WITH A

HEALTH PERSPECTIVE

A QUALITATIVE INTERVIEW STUDY

INGER BJURNEMARK STARK

HÅLLBARA BYGGNADER

MED ETT

HÄLSOPERSPEKTIV

EN KVALITATIV INTERVJUSTUDIE

INGER BJURNEMARK STARK

Bjurnemark Stark, I. Sustainable Buildings with a Health Perspective. A

Qualitative Interview Study. Master’s Thesis of Public Health, 30 ECTS Credits. Malmö University: Health and Society, Department of Public Health, 2009.

When buildings are constructed and renovated today, environmental aspects are most often taken into consideration. There might, however, not always be a clearly expressed health perspective. This study explores the obstacles and opportunities to initiating a clearer health perspective in the construction and real estate branches. A qualitative method was used, consisting of semi-structured interviews with ten agents from the construction and real estate branches in the private and municipal sectors. The analysis was performed by the use of

organisational theory. The results show that different financial incentives such as “ROT-deductions” are the ones most discussed when it comes to attaining a clearer health perspective into the sustainability work of the branches. Suggestions for improvement in the legislative area were for example about specifying threshold values for certain substances in the indoor environment, and about improving policy for how chemical products are to be declared. Different classification systems for healthy buildings could also be of use, if coordinated to be better understood. Also the need to discuss ethics, morality and “attitude” in the branches was brought up.The need to use health economic measures to be able to make comparisons to other societal costs was also emphasized.

Keywords: Action Science, Indoor Environment, Million Programme, Renovation of Buildings, Sustainable Buildings.

Table of Contents

1. INTRODUCTION ... 5

1.1OBJECTIVES AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS... 6

2. BUILDING ISSUES ... 7

3. INDOOR HEALTH ISSUES ... 9

3.1ASTHMA AND ALLERGIES... 9

3.2SICK BUILDING SYNDROME...10

3.3DIFFERENCES IN SENSITIVITY...10

3.4EXAMPLES OF OTHER INDOOR HEALTH ISSUES...11

3.4.1 Particles ...11 3.4.2 Radon ...11 3.4.3 Noise...12 3.5THE COST OF ILLNESS...12 3.6OUR KNOWLEDGE IS LIMITED...13

4. LEGISLATION... 14

4.1ENVIRONMENTAL AND PUBLIC HEALTH OBJECTIVES...14

4.2THE SWEDISH ENVIRONMENTAL CODE...14

4.3BUILDING LEGISLATION...16

4.4KNOWLEDGE AND PRECAUTION...17

5. BUILDINGS IN NEED OF RENOVATION ... 18

5.1AN AGEING HOUSING STOCK...18

5.2HOUSING POLICY...19

5.3CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS AND DATABASES...21

5.3.1 The Building-Living Dialogue ...21

5.3.2 MIBB ...21 5.3.3 BASTA ...22 5.4OTHER INCENTIVES...22

6. METHOD ... 23

6.1INTRODUCTION TO METHOD...23 6.2DATA COLLECTION...23 6.2.1 Sampling...246.2.2 Conducting the Interviews...24

6.2.3 Interview Issues ...26

6.2.4 Number of Interviews ...26

6.4ANALYZING THE DATA...28

6.5ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS...28

7. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ... 31

7.1LEARNING ORGANISATIONS...31

7.2ACTION SCIENCE AND ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING...32

7.2.1 Espoused Theories and Theories-in-use ...32

7.2.2 Single-loop and Double-loop Learning ...34

7.2.3 Model I and Model II Theories-in-use ...36

7.2.4 Learning Disabilities...38

7.2.5 Interventions ...39

7.3ORGANISATIONAL THEORIES AS A BASIS FOR ANALYSIS...40

8. RESULTS ... 41

8.1THE INTERVIEWEES...41

8.2TAKING PRECAUTIONS AND LEARNING FROM MISTAKES...41

8.3AVAILABILITY OF KNOWLEDGE...44

8.4KNOWLEDGE,UNDERSTANDING AND ATTITUDE...49

8.5OPPORTUNITIES TO CREATE HEALTHY BUILDINGS...54

8.6SIDE FINDINGS...64

9. DISCUSSION ... 66

9.1OBSTACLES TO ACHIEVING HEALTHIER BUILDINGS...66

9.1.1 Taking Precautions and Learning from Mistakes ...66

9.1.2 Availability of Knowledge ...68

9.1.3 Knowledge, Understanding and Attitude ...69

9.1.4 Obstacles, a Summary...70

9.2INCENTIVES TO BRING ABOUT A HIGHER EMPHASIS ON HEALTH ISSUES...70

9.3DISCUSSION OF THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK...71

9.4CONCLUDING DISCUSSION...72

9.5FURTHER RESEARCH...74

REFERENCES... 75

APPENDICES ... 80

APPENDIX 1:INTERVIEW GUIDE...81

APPENDIX 2:APPLICATION FORM –ETHICS APPROVAL...85

APPENDIX 3:LETTER OF INFORMATION...88

1. Introduction

Our Swedish climate, as well as our modern habits of work and leisure, causes us to stay indoors most of the time1. There are, however, some emerging health issues connected with this contemporary indoor lifestyle. Building materials and construction methodscould have adverse effects on the indoor environment, causing a negative impact on occupant health status. This study explores the use of different incentives to create healthier homes.

When buildings are constructed and renovated today, environmental aspects are most often taken into consideration, because of different legislation but also for economical reasons. However, even when a building is constructed or renovated in an environmentally sustainable way, there may not always be a clearly expressed health perspective present. Although there are some guidelines for building and renovating in a sustainable way with a clear health perspective, such as the Building-Living Dialogue2 (2009) there are no obvious incentives for real estate owners or building companies to follow these guidelines. It must of course be beneficial for society in the longer perspective to build as healthy as possible, as this will increase the chance of people staying healthy, thus decreasing societal costs for ill health. It would therefore be better to choose materials and methods that according to present scientific knowledge are the safest. Even if all

connections between building materials and ill health are still not clear and proven, the Swedish Environmental Code (SFS 1998:808) states that the

Precautionary Principle should be used in all matters of threat to human health or the environment and that it is not always recommended to wait for scientific proof before taking action. The question is, though, how can this be implemented? As there seems to be no obvious benefits, financial or otherwise, in spending

resources on building extra careful just as a precaution, there might be a need for other incentives.

1An often mentioned amount of time spent indoors is about 22 hours a day, or 90 % of the time. (See for example Koenig, 2002; National Board of Health and Welfare, 2005:71)

1.1 Objectives and Research Questions

The main objective of this study is to look into how the construction and real estate branches take the health perspective into consideration when building and renovating, and how this might be improved. The research questions are:

o Which are the obstacles to achieving healthier buildings when building and renovating today?

o Which incentives would be needed to bring about a higher emphasis on health issues, as opposed to following minimum standards, when building and renovating?

2. Building Issues

Until some decades ago, the construction of a building was a craftsman job for the warmer season. It took a long time to build a house, and the construction materials were well-known as they had been used for generations. Nowadays, buildings are constructed all the year around, and construction work has become more of an industrial process with a continuous flow of new techniques and materials. The construction faults that sometimes occur in modern buildings may often come from inferior technical solutions, carelessness somewhere in the building process, inappropriate construction materials and furnishings, or a combination of all the above. Indoor health issues might be caused by these faults in the construction process, but may also arise from inadequate maintenance or if a building is used in a way it was not intended for. (Hagentoft, 2002:180-182)

A national investigation about indoor environment, SOU 2005:55, considers dampness issues to be the most frequent problem in buildings of today, and that dampness is most commonly caused by construction material that has been damaged by moisture or that has not been allowed to dry properly before being used. Dampness in a building might also be caused by water leaking in from the ground, or be caused by other kinds of water leakage (Ibid.). Dampness may often cause mould in buildings, which, often together with inferior ventilation systems, could result in ill health for the inhabitants (National Board of Health and

Welfare, 2005:130).

Modern demands on energy efficiency could, at worst, also contribute to causing ill health. In Sweden, the requirements on increased energy efficiency in buildings came for the first time after the oil embargo of 1973/74 (Elmroth, 2006:79). Before that, buildings were not always sufficiently insulated, as fuel was cheap and readily available. To save energy when oil became in short supply, older buildings were often insulated and sometimes made airtight to prevent energy leakage (Elmroth, 2006:80). If the ventilation systems were not modified in accordance with these new demands, the indoor environment often deteriorated, causing problems with damp and mould (Hult, 2006:203-204). New buildings of today should be constructed according to regulations to avoid these issues, but

older buildings, whether they are renovated or not, are not always adequately ventilated3.

Another important indoor health issue is that of chemical emissions. One hundred years ago there were about 500 different construction materials available on the market, compared to today’s more than 60 000 different products (SOU

2005:55:58). The growing amounts of available construction products have made it increasingly difficult to keep control of all materials and, maybe most

importantly, the consequences of their interaction with each other and their environment.

To sum it up, construction materials and methods are sometimes suspected to cause ill health. Some relations are quite clear, while others still remain to be explored.

3 One contributing risk factor for decreased ventilation rates in older buildings is the modification into modern heating systems, such as district heating. (See for example Samuelson, 2002)

3. Indoor Health Issues

3.1 Asthma and AllergiesThe most well-known indoor health issue would probably be the increasing prevalence of asthma, wheezing and allergies in children and adults (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2005:130). These issues have increased

significantly during the last decades, as about 25 % of the population is affected today, as compared to these diseases being quite rare in the 1950s (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2009:95). Often the indoor environment is suspected, and as Bornehag et al (2005a) points out, the increase in allergic diseases coincides well in time with the decreased ventilation rates in buildings that came with the higher demands on energy efficiency a few decades ago. A case-control study by Bornehag et al (2005a), where 390 Swedish homes were inspected, indicates that low ventilation rates are associated with preschool children having wheezing, rhinitis or eczema. A related study, a cross-sectional study of 10.851 preschool children in Sweden, also by Bornehag et al (2005b) showed associations between prevalence of wheezing, asthma, rhinitis and eczema, and dampness issues in their homes4. Indoor health issues might be caused by poor building maintenance, but also newly built and renovated houses might cause problems,especially when it comes to chemical emissions. A study by Jaakkola et al (2004), examined the effects of recently renovated buildings on prevalence of asthma, wheezing and allergies in 5.951 Russian school children. This study showed a significant increase in asthma, wheezing and allergies in children living in newly renovated homes, an example being new linoleum flooring. Another study by Jaakkola et al (2006) has also established correlations between renovating with surface materials such as plastic wall materials and floor-levelling plaster, and onset of adult

asthma. Suspected health risks are for example composite wood materials, plastic materials and paint, as these materials might emit chemical compounds such as formaldehyde or phthalates (Mendell, 2007). Decreased ventilation rates are suspected to increase the risk of ill health from indoor pollutants in most cases5 (Mendell, 2007).

4 The indicators of dampness in this study were water leakage, condensation of windows, detached flooring material, and visible spots of damp or mould.

3.2 Sick Building Syndrome

According to Redlich and Sparer (1997) sick building syndrome (SBS) is a name used to describe different signs of discomfort from spending time in a specific building, and where no obvious causes are present. The symptoms of SBS could be for example irritated eyes, nose and throat, coughing, dry skin, rash, sensitivity to odours, headaches and fatigue (Redlich & Sparer, 1997). The source of SBS symptoms are often suspected to be poor building design, use or maintenance that is inconsistent with the original intentions for the building, occupant activities, and also inadequate ventilation and chemical or biological contaminants (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 1991). As SBS symptoms have become increasingly common since the 1970s, they might be connected to new energy efficient, air-tight buildings with mechanical ventilation, and an increased use of synthetic materials (Redlich & Sparer, 1997). There is also some evidence from workplace studies that not only properties of the building but also other factors such as psychosocial conditions might worsen the SBS symptoms (see for example Runeson et al, 2006). As all connections are still not clear, SBS should probably be seen as a complex issue with more than one possible solution (Redlich & Sparer, 1997).

3.3 Differences in Sensitivity

There are some groups in society that are especially susceptible to ill health due to environmental conditions. Children are more susceptible than adults to medical conditions from any kind of pollution, due to not being fully biologically

developed, and because they have faster metabolisms and higher respiratory rates than adults (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2005:60). Unborn children are extra sensitive to disturbances, as complex organ systems such as the brain, the immune system, the reproductive system and the hormone system are developing over a long period of time (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2005:64-66). Lately, some studies of the connections between environmental chemicals and increasing “modern diseases” have been made. As an example a study by Swan (2008) showed an association between a higher phthalate concentration in mothers and different reproductive disorders in their young children, for example

neuropsychiatric disorders6 and environmental chemicals are under suspicion (see for example Grandjean & Landrigan, 2006).

Also adults, if they have underlying diseases, might be more susceptible to ill health from indoor environmental causes. Those who suffer from allergies, immune suppression or lung disease, such as COPD7, are for example more likely to suffer from infections of the lungs if exposed to mould. (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009)

3.4 Examples of Other Indoor Health Issues

The list of indoor health issues could be very long, and the examples stated in this section do not constitute any attempt to make a complete list of possible health issues. They are, however, some examples of ill health that may be caused by building issues.

3.4.1 Particles

Particles are a comprehensive term for different solid, gaseous or liquid pollutants that might either be suspended in the air or settled on surfaces as dust. There are always particles in indoor air, and they come from sources such as outdoor air pollution, building materials, textiles, plants, skin and hair. Sometimes they might be polluted by for example soot, tobacco smokeand allergens from pets or dust mites. An increased content of particles in indoor air often causes irritation of eyes and airways and they might also carry allergenic substances or carcinogens such as radon. (Swedish Asthma and Allergy Association, 2001:44)

3.4.2 Radon

Radon is a significant health issue in some parts of Sweden. Radon is a radioactive gas which is formed from the natural decay of uranium. Radon is undetectable without instruments and may come from certain types of soil and rock, from drinking water or from certain building materials. When radon is suspected, certain construction methods must be used to avoid leakage into

6 For example autism spectrum disorder, Asperger’s syndrome and Tourette’s syndrome 7 In Swedish KOL; kronisk obstruktiv lungsjukdom

buildings, as it causes lung cancer. The Swedish limit for radon in dwellings is 200 Bq/m3. (Swedish Radiation Safety Authority, 2009)

3.4.3 Noise

Another important health issue is the occurrence of noise in buildings. Indoor noise might come both from the outside environment, for example from traffic or nearby industries, or from indoor sources such as elevators, ventilation systems or neighbours. It is important to reduce the noise levels as much as possible, as noise might in some cases cause for example hearing impairment, insomnia, stress, hypertension and heart disease. (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2008)

3.5 The Cost of Illness

How much does it cost to be ill, and who is paying? The life-time cost of for example asthma could be calculated in some ways, but not in others. Direct costs like health care and medical costs might be estimated, as well as indirect costs, such as loss of production, and cost of sick leave and parental leave. Other, intangible costs such as pain, worry and loss of life quality are more difficult to quantify.8

According to a literature review by Jansson et al (2007) there are only a few studies, nationally and internationally, that try to estimate societal costs for allergic diseases. There is therefore a need to gain more knowledge in this area, as it is of great importance for planning of health care and to prioritize research. The results of this study show an estimated yearly cost for asthma, rhinitis and eczema in Sweden of somewhere between SEK 4-11 billion. The large span of the cost estimates is explained by different health care systems and study designs in different countries, which sometimes makes the results difficult to translate to Swedish conditions.

It is important to bear in mind that these figures say nothing about the causes of allergic diseases. Indoor environment issues are suspected to cause ill health, but we do not now to what extent. The case of peoplebecoming ill from their indoor

environment might be seen as society having to pay for the shortcomings of other agents, such as chemical manufacturers or construction companies. However, the responsibility for initiating any health research needed rests largely on society.

3.6 Our Knowledge is Limited

Even if indoor air issues are associated to several types of ill health, many causal relations still remain to be proven. For example, the increasing prevalence of asthma and allergies over the last decades is not yet fully explained, but as this increase has happened to fast to be explained exclusively by genetic factors, there are most likely some lifestyle and environmental causes involved (Bornehag, 2008). As Mendell (2007) points out, there is no absolute certainty about which the truly causal exposures are when it comes to most indoor health issues, as the risk factors identified today may just be indicators that correlate to the true causes. Anyway, there seems to be some kinds of health issues in modern homes that need to be further investigated.

While waiting for more research on indoor health issues, it would seem like a good idea to protect public health by taking precautions against suspected materials and methods as much as possible.

4. Legislation

Indoor environment is a complicated area also when it comes to legislation. There are several different objectives, laws and ordinances that apply and that could be used to take public health measures towards an improved indoor environment.

4.1 Environmental and Public Health Objectives

The Swedish Parliament has adopted 16 environmental objectives and 11 public health objectives to provide a framework for different initiatives at national, regional and local level. The objectives relevant to indoor environment are first of all the environmental objective A Good Built Environment (Environmental Objectives Secretariat, 2008) and the public health objective Healthy and Safe

Indoor and Local Environment (Swedish National Institute of Public Health, 2009).

The environmental objective A Good Built Environment specifies for example that ventilation rates and limits for radon concentrations in buildings must follow certain standards. According to the Environmental Objectives Secretariat it will, however, be difficult to reach the different goals for ventilation and radon in this environmental objective as there are simply no efficient policy instruments available to be able to make measurements or otherwise to achieve what has been decided in the objective.(Environmental Objectives Secretariat, 2008)

4.2 The Swedish Environmental Code

The Swedish Environmental Code (SFS 1998:808) was adopted in 1998. The law includes only fundamental rules, which are complemented with detailed

provisions in ordinances from the Government. The Environmental Code may sometimes be used for issues that arise when using an older building, as this is often not regulated in any other legislation, such as building legislation (SOU 2005:55:34-35). In the 9th chapter of the Environmental Code (SFS 1998:808) there are for example special provisions about health protection:

Section 9: Dwellings and public premises shall be used in such a way as to prevent detriment to human health and shall be kept free of vermin and other pests. The

owners or tenants of the property in question shall take any measures that may be reasonably required to prevent or eliminate detriment to human health. (SFS 1998:808: Chapter 9, Section 9)

An example of a more detailed rule on indoor environment can be found in the Swedish Ordinance (1998:899) concerning Environmentally Hazardous Activities and the Protection of Public Health9:

Section 33: In order to prevent the development of risks to human health, all dwelling places shall:

1. provide adequate protection against excessive heat, cold, draught, damp, noise, radon, air pollution and other disturbances of a like nature

2. provide adequate exchange of air with a ventilation system or by other means 3. supply adequate daylight

4. maintain a satisfactory level of heating

5. provide facilities for maintaining good personal hygiene

6. provide access to water of sufficient quantity and of acceptable quality for drinking, food preparation, personal hygiene and other household requirements

For more detailed advice, the National Board of Health and Welfare publishes general advice on indoor health issues to specify the rules of the Environmental Code on health protection in residential areas for issues such as temperature, noise, radon, ventilation, dampness and microorganisms10.

The Environmental Code (SFS 1998:808) also contains a list of rules of consideration11, the fundamental one being the Precautionary Principle. This principle states that “…precautions shall be taken as soon as there is cause to

assume that an activity or measure may cause damage or detriment to human health or the environment.” (Chapter 2). This rule applies to all operations that may be relevant to the objectives of the Environmental Code.

9 In Swedish: Förordning (1998:899) om miljöfarlig verksamhet och hälsoskydd 10 These advices are called SOFS 2005:15, 2005:6, 2004:6, 1999:25 and 1999:21.

11 Besides the precautionary principle, other rules of consideration concerns for example burden of proof, knowledge, best possible technology, appropriate location, resource management and product choice.

4.3 Building Legislation

The framework when constructing new buildings is the Plan and Building Act, PBA (SFS 1987:10). The National Board of Housing, Building and Planning12 are responsible for the legislation under the PBA. Regarding technical demands on constructions the PBA is complemented with the Act (1994:847) on Technical Requirements for Construction Works, etc.13 The rules are not too detailed, but contains requirements on for example stability, safety, energy efficiency,

accessibility, economy and health issues. More detailed regulations are available for example in the Ordinance (1994:1215) on Technical Requirements for Construction Works, etc14, as shown below:

Section 5: Construction works must be designed and built in such a way that they

will not be a threat to the hygiene or health of the occupants or neighbours, in particular as a result of any of the following:

1. the giving-off of toxic gas;

2. the presence of dangerous particles or gases in the air; 3. the emission of dangerous radiation;

4. pollution or poisoning of the water or soil;

5. faulty elimination of waste water, smoke, solid or liquid waste;

6. the presence of damp in parts of the works or on surfaces within the works.

Other rules that may effect indoor health issues are for example the Ordinance on Function Control of Ventilation Systems (SFS 1991:1273), and the Law on Energy Declaration in Buildings (SFS 2006:985). For new buildings and extensions, the BBR15 applies. This is an instruction manual for construction, where all requirements are collected. It contains both mandatory provisions and general recommendations (BFS 1993:57). For comprehensive amendments that will raise the useful lifespan of a building significantly, there might be

requirements for using the BBR also for older buildings (National Board of Housing, Building and Planning, 2003a:54). Otherwise, for older buildings, the

12 In Swedish: Boverket

13 In Swedish: Byggnadsverkslagen

14 In Swedish: Förordning om tekniska egenskapskrav på byggnadsverk, m m

15 In Swedish: Boverkets Byggregler. The full name is Building Regulations BFS 1993:57 with amendments including BFS 2006:22 (BBR) of the Swedish Board of Housing, Building and Planning.

BÄR16, a collection of advice on changing and renovating buildings, is used (National Board of Housing, Building and Planning, 2006).

4.4 Knowledge and Precaution

To sum it up, it seems like there would be adequate laws to ensure a healthy indoor environment to everybody. The authorities for example have possibilities by law to influence which construction materials and technical constructions that are allowed to use when building and renovating. The problems appear for the most part to lie in the implementation of the laws, as it takes a large amount of resources to keep control of how the laws are complied with, and also that there in many cases are no concrete threshold values for example for what should be considered to be an inconvenience for people’s health (SOU 2005:55:46-47).

Regarding construction of buildings, the solution of many indoor issues will probably lie in an increased amount of research on the subject of constructing good modern buildings. As for example Hagentoft (2002:179) points out, it would not be an option to try to go back to older construction methods, as they would not be able to meet the demands on our modern life style. Also, old buildings have their own set of problems, which often includes draft, high energy use, and in many cases also dampness and mould (Hagentoft, 2002:179). Old construction solutions would surely also be too expensive and time consuming to use in a larger scale.

5. Buildings in Need of Renovation

5.1 An Ageing Housing Stock

More than half of the existing apartment buildings in Sweden were built between 1945 and 1975. Today, many of these buildings are in need of a thorough

renovation because they are run down, but also to be able to meet new energy saving standards. (National Board of Housing, Building and Planning, 2005)

The most intense building period in Sweden was between 1965 and 1975. Even if there was an increase in building activities immediately after the war, there was still a large housing shortage in the beginning of the 1960s. The Government therefore initiated the “Million Programme” whose goal it was to construct 1.000.000 new homes in ten years. The goal was reached, and in 1975 dwellings for more than one million17 families had been built. (SABO, 2008)

Afterwards, the Million Programme has been subject to extensive criticism, as it often involved a fast, industrialised form of building with the workers being pressed for time and where new, experimental methods and materials were used. At the same time, the Swedish living standards were in need of fast improvement. (Vidén, 1999:140)

In 2003 the National Board of Housing Building and Planning made a summary of the need for renovation in Swedish apartment buildings. Of 1.350.000 apartments that were built between 1946 and 1975, it was estimated that about 400.000 of them had already been renovated. Even if 25.000 apartments have been renovated each year since then, this would mean that today at least half of the apartments remain to be renovated. Most of these are likely to be built during the Million Programme. (National Housing Credit Guarantee Board, 2008:6)

It is difficult to know which possible issues the new buildings of today will lead to in the future. Even if all new houses would be without problems, the new

buildings that are constructed in a year are less than one percent of the existing

building stock (National Board of Housing, Building and Planning, 2003b:66). Many houses that were built in the 19th century or in the beginning of the 20th century are still used. The houses that are built today will therefore continue to affect us for maybe one hundred years. Therefore we cannot count on getting rid of building problems any time soon by building new houses, which makes it an important public health issue to take also the older buildings into consideration when addressing indoor health issues. Many of the older, run down apartments are inhabited by people with low socio-economic status who might not have the possibility to choose where to live or to influence the maintenance of the building, which makes this public health issue even more urgent.

5.2 Housing Policy

The rights of real estate owners are regulated in the Constitution, which states that the owner of a building has the right to make decisions about the building, with very few limitations (SFS 1974:152, Chapter 2, Section 18). The owner is also responsible for keeping the building in sufficient condition according to

environmental and building legislation, as stated above. The owner of a dwelling is therefore responsible for obeying all applicable laws. For those who own their own homes it is probably a natural thing to keep it in good order, to their best knowledge, as it is themselves and their families who are influenced by the condition of the building.

Regarding rented apartments, however, it is important to remember that real-estate companies and tenants are different agents who might in some cases have

different goals for the dwellings. For example, a real estate owner might see a building as a short term investment, which could affect the way the building is maintained, and which in turn could lead to the tenants not having sufficient living conditions. Issues of this kind would most likely be present in areas where the real-estate owners focus on short term profit, where the tenants have low income, where the tenant turnover is high and where the sense of caring and responsibility within the area is relatively weak. (National Housing Credit Guarantee Board, 2008:10)

A real-estate owner is required by law to maintain a lowest acceptable standard in all apartments. The tenants’ rights are regulated in the “Tenants Act” (Land Code, SFS 1970:994, Chapter 12) where it is stated that measures that affect the utility value, or that will lead to large changes to the apartment, must be approved by the tenants. There are, however, no possibilities for tenants to demand any measures in addition to the lowest acceptable standard (National Housing Credit Guarantee Board, 2008:13). An owner of a building is presumed to be interested in making profitable investments to raise the utility value of their property, and as long as the tenants are aware of how these investments will affect them in terms of utility and cost, the real-estate owner is free to proceed with any measures, or to abstain from taking any measures at all (National Housing Credit Guarantee Board, 2008:13).

In Sweden almost half of the rented apartments are owned by non-profit housing companies18 (SOU 2008:38:78-79).The Swedish non-profit housing sector has four main characteristics: it is non-for-profit operated, it is mostly owned by municipalities, it is open to everybody and the rents are used as norm for the rental levels for all rented housing (National Board of Housing, Building and Planning, 2008:7).

The municipal housing companies have often been used as instruments of social and economic policies, for example by producing housing to reduce over-crowding, to end housing shortage and to improve housing standards. They have also been utilized to build houses where and when the Swedish industries needed labour. Until about twenty years ago, the non-profit housing companies were mostly built up through different kinds of State funding, but nowadays most companies have become limited liability companies, even if they in most cases are still owned by the municipalities. (National Board of Housing, Building and Planning, 2008:26-28)

In some areas, the renovation of apartments cannot be seen as profitable from a business economical point of view, even if it could be seen as necessary from a socio-economic perspective.

18 In Swedish: Allmännyttan

5.3 Classification Systems and Databases

There are a number of environmental classification systems and databases on the Swedish market. They are intended to be of help for the construction and real estate branches in their choices of building materials and construction methods. The companies are not compelled by law to use any of the systems, but they are often used on a voluntary basis, and they are sometimes referred to in tender documents. Below I will give examples of some of the common environmental classification systems and databases that are used.

5.3.1 The Building-Living Dialogue

The Building-Living Dialogue19 is a project of cooperation between the

Government, different authorities, municipalities, and companies who are in the construction and real estate branch or that are connected to these. The main objectives in the areas of indoor environment, energy use and use of natural resources are to create a sustainable building and real estate sector before the year 2025. The parties involved are committed to working towards a sustainable development not only by adapting the Swedish Environmental Objectives, but also by following certain internal goals that exceed the national objectives. (Building-Living Dialogue, 2009)

5.3.2 MIBB

MIBB20 stands for environmental inventory of the indoor environment in existing housing. It is a housing declaration that has been prepared in cooperation between a number of housing companies and organisations. The method includes a tenant questionnaire about for example heating comfort, noise, light, indoor air quality, and dampness and mould. Also an inspection is performed of apartments and common areas with regard to for example indoor and outdoor environment, maintenance and energy use. (SABO, 2006)

19 In Swedish Bygga Bo-dialogen

5.3.3 BASTA

BASTA is a database system whose aim it is to accelerate the phasing out of unsafe chemical substances in construction material. The suppliers are responsible for the registration of their products being performed correctly. The criteria of the system are based on REACH, the European Union chemical legislation. BASTA is owned by IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute and the Swedish Construction Federation. It is run as a non-profit limited company. The BASTA database is accessible for anyone, free of charge. (BASTA, 2009)

5.4 Other Incentives

There might be other incentives to consider, besides the ones listed above. Companies in the construction and real estate branches are surely interested in maintaining and developing their trademark. There is also a public awareness about indoor health issues that might be on the rise just as the interest in other environmental issues. As asthma and allergies are increasing, patients’ organisations like the Swedish Asthma and Allergy Association might get stronger and more influential by recruiting more members.

6. Method

6.1 Introduction to Method

For this study, a qualitative study method was chosen, as I wanted to bring out the underlying reasoning of different agents representing the research area, and to find out about their opinions about how to achieve an improved health perspective in their branches. A quantitative method would not in the same way show different nuances and insights that can be brought forward in a qualitative study, for example by posing follow-up questions in an interview situation. The method chosen for the study was interviews, as they according to Dahlgren et al (2007:79) are a good way to learn about people’s experiences and to get descriptions of events in the life worlds of the informants. Also, as Silverman (2007:113) points out, “…interviews are relatively economical in terms of time and resources”. As both time and money tend to be scarce resources for researchers, this also speaks in favour of interviews as a research method. The interview form was semi-structured, which according to Kvale et al (2009:27) means neither a closed questionnaire nor an open conversation, but that the interviews are conducted using an interview guide that presents different themes as bases for discussion.

Other qualitative methods that could have been used in a study like this one are for example observations or text analyses. Observations are mostly used when finding out about how people behave and interact with their environment (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009:115). Texts, for example official documents or other written material, might be analysed in the same way as transcribed interviews (Silverman, 2007:153-154). None of these methods was, however, considered to be useful in this context, except as for background information, as there is no available material that would have answered the research questions sufficiently.

6.2 Data Collection

The data collection method consisted of semi-structured interviews withdifferent agents representing real estate companies, construction companies and the municipality.

6.2.1 Sampling

The agents that would be of interest to the study were identified as representatives of real estate owners, building contractors, building consultants and civil servants on municipality level. Acriterion that had to be fulfilled in order to be

interviewed was to be in a position to make decisions, influence choices or otherwise have good knowledge about building materials, building methods or other housing issues. This could be performed through for example being

responsible of purchasing or through influencing policy decisions. Some interview candidates were identified by my supervisor, some I found through acquaintances and then the interviewees were asked to suggest other participants to the study. The interview candidates were contacted by e-mail, with brief information about the study, and they were then invited to contact me to set up an appointment if they were interested. In some cases, a reminder was sent about a week later.In total,28 candidates were contacted, which resulted in ten interviews. Those who declined did it because of lack of knowledge on the interview topic, or due to time issues.A majority of the candidates who turned me down were able to suggest another, more suitable, person to be interviewed. Only a few of the candidates did not answer me at all.

As this study does not involve any pronounced gender issues, I have not made any special effort to achieve an even distribution of male and female interviewees. As it turned out, seven women and three men were interviewed. The age span was fairly evenly distributed from approximately late twenties to early sixties, which is probably reasonable as I primarily looked for agents with some experience in their positions. Even if it would also have been interesting to talk to some younger people who were new in their professions, the ones I contacted declined, mostly due to their lack of experience. The distribution regarding different sectors is also fairly even. Six of the interviewees are employed in the public sector at

municipality level or work in non profit organisations. Four of the interviewees work in private companies or are self-employed.

6.2.2 Conducting the Interviews

It was decided that the interviews were to be performed either at the participants’ work places or at Malmö University, according to the participants’ choices. It is of

course important not to be disturbed during an interview, and to avoid background noise as much as possible. There were also other things to consider, for example if the participants had time and possibility to leave their work places during the day or if they preferred to be interviewed in the evening. There could possibly also be the issue of not wanting co-workers or managers to listen in to the interview. As it turned out, all of the interviewees chose to be interviewed at their respective work places. In one case, a telephone interview was performed, as it was preferred by the interviewee.

The themes of the interview guide (Appendix 1) were built on health issues, causal relations, responsibilities, knowledge, and about different incentives to influence the actions of the construction and real estate branches.

Some follow-up questions were written down in advance for each theme in the interview guide, but all relevant topics that evolved throughout the interviews were followed up. This involves the art of active listening, which according to Kvale and Brinkmann (2009:138-139) takes a lot of concentration and knowledge about the interview topic.

According to Dahlgren et al (2007:81-82) there are different opinions about whether to use a tape recorder or not when making qualitative interviews. As my interviewing experience is limited, I decided that in order to be able to listen properly to the interviewees and in the same time be able to formulate suitable follow-up questions in the interview situation, it was more or less necessary for me to use a tape recorder. Otherwise there would have been a great risk of missing out on some important information when concentrating on making elaborate notes of the answers. As Dahlgren et al (2007:82) say: “…when we take notes we

unconsciously sort out what does not seem important and these parts will be lost forever”. Another reason for using a tape recorder would be that my interviews were conducted in Swedish.The material was then translated into English during the process of the analysis. If hand-written field notes were first to be interpreted into a proper computer transcript and then later translated into English, this would mean that they would have to be interpreted twice, and even more information could have been lost in translation.There is of course the issue of an interviewee not wanting to be recorded, as he or she might for example feel uncomfortable

about it. Then there would be no other choice but to make field notes instead. In this study all the interviewees agreed to be tape-recorded during the interview.

The first interview appeared to be a little on the long side and also, some

questions were considered to be a little difficult to understand. I decided to adapt to this situation and narrow the interview guide down a little by rephrasing some questions, where the answers were overlapping. This turned out to be a good move, as several of the following interviewees presupposed that the interview would last for an hour, and had scheduled me accordingly. In some aspects, the first interview therefore worked as a trial interview, which was not intended from the beginning. Still, I consider these problems to be quite minor, as this interview turned out very well, even if it took unnecessary time to explain some vaguely phrased questions. The length of the interviews varied between about 1 hour and 1.5 hours.

6.2.3 Interview Issues

A problem with interview studies could be that the people who agree to be interviewed might have a special interest in healthy buildings and other health issues, and they might therefore not be representative for the whole group of agents. Also, when the interviewees are asked to suggest other participants for the study, they will probably recommend people they believe have a special interest in these topics. This might be compared to the “healthy volunteer effect” issue that is often discussed when it comes to participating in quantitative health studies, as participants who enrol in a study tend to be healthier than the average population (see for example Thomson et al, 2005). This could possibly create bias. In this study the participants were expected to discuss the building and renovation of homes, and they have hopefully been able to discuss both positive and negative sides of the business, even if they could all be considered to be representatives of the “good guys” with a genuine interest in healthy buildings.

6.2.4 Number of Interviews

It is always difficult to know in advance how many interviews will be needed in a study. According to Kvale and Brinkmann (2009:113) the best way to go about it is to end the series of interviews when saturation is reached, which means that

nothing new that is of significant value is experienced in the latest interview. There is, however, also the time frame of the study to consider, in this case 20 weeks. After the initial literature study, and after the ethics application (Appendix 2) was approved, I first set the interview period to one month. As it turned out, I was unable to find a sufficient number of interview candidates in this time period, so I decided to continue until ten interviews were completed.This number of interviewees can surely be seen as quite large enough to make an interesting analysis, as the interviewees represent different types of companies in the

construction branch and the real estate branch, as well as different departments of the municipality. If time had allowed it, a larger number of interviews could have been performed, which for example could have made it possible to make

comparisons between the opinions of different groups of agents, and to draw more generalised conclusions. This would maybe have added an extra dimension to the study.

6.3 Registration of Data

After an interview was concluded it was transcribed into a Word-document with the interview guide working as a frame for the text. All hand-written notes from the interviews were also gone through as an extra support when interpreting the tapes. I transcribed the interviews myself, not only for economical reasons, but also to get practice in the art of transcribing, and to get to know the material better. As Kvale and Brinkmann (2009:180) say:

Researchers who transcribe their own interviews will learn much about their own interviewing style; to some extent they will have the social and

emotional aspects of the interview situation present or reawakened during transcription, and will already have started the analysis of the meaning of what was said.

Reliability and validity of a transcript may of course be questioned, and to check reliability Kvale and Brinkmann (2009:184) suggest that two persons transcribe the same material and analyze the differences. As good as this may sound, it would be very time-consuming and expensive. Instead I have made an effort to make good quality recordings, and the tapes were also kept available to the

supervisor, opponent and examinator if they would want to check the material at some point during the examination process.

To examine the validity of a transcript, Kvale and Brinkmann (2009:186) propose the question “What is a useful transcription for my research purposes?” With this question they claim that there is no really objective way to write down a tape recording, but that interviews are transcribed in different ways depending on the purpose, and that the form of transcription should be explained in the study (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009:186). As this study is not a linguistic analysis, but a search for facts, beliefs and opinions, the interviews were not transcribed in a verbatim way with markings for pauses in speech, different tones of voice, etcetera. Instead they were simply interpreted into written language, word by word but not

necessarily with full sentences or correct punctuation. The transcription resulted in 164 pages of text.

6.4 Analyzing the Data

The analysis of the transcripts was performed using an ad hoc method inspired by Kvale and Brinkmann (2009).The interpretation was made in different steps, as described below.First of all I printed the transcribed interviews and read them through thoroughly. Then, while reading the texts a second time, I started looking for common themes. These themes were marked with marking pens, a different colour for each theme. When this was done, the transcribed material was remodelled in the computer, so that it showed theme by theme. Then I read through the text, theme by theme, to be able to describe the main points of each theme and to find suitable passages to use as quotations to illustrate the different themes. During this work, I returned several times to the original transcriptions to check the context of a statement or to find more information about a topic.

6.5 Ethical considerations

When conducting an interview study there are some ethical concerns involved, one of them being the issue of informed consent. This means first of all that the participants are to be informed about the study and its purposes in advance. The information does not have to be too detailed though, as this may in some cases affect the way the participants will answer the questions of the interview.

Secondly, the issues ofconfidentiality must be explained, which can for example relate to if the participants are made anonymous or not, and it should also be explained who will have access to the research material. Last but not least, the participants are also to be informed about that they are participating voluntarily and that they have the right to withdraw at any time without necessarily having to explain why. It is often recommended to have a written agreement between the interviewer and the participants that explains the issues of informed consent. (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009:70-71)

In this study the ethics has been sustained by using a written consent form (Appendix 3 & 4) where the main purposes of the study were stated, the issues of confidentiality were explained and the voluntary participation was clarified.As quite a small group of people has been interviewed and as it is stated in the report that the interviews are conducted with people from these certain groups of professionals, there are of course the risk of the interviewees being recognized even if their names and work places are made anonymous. To be as careful as possible I have therefore offered the interviewees to go through and approve all occurring direct quotes before the publication of the report. Eight of the ten participants agreed to check their quotes. The interviewees were also asked what they wanted to be called in the thesis, by choosing a professional title to be used for the quotes. This was hopefully a good way to get appropriate titles and to avoid misleading names.

Some of the participants in this study asked for clarifications about the purpose of the study, or wanted to get the questions in advance to be able to prepare the answers. As I saw no problems with this, those who asked got the clarifications or questions. Possibly, all participants could have got the main themes of the

interview in advance, but as I did not ask the participants to account for exact facts and figures, but more for their beliefs and opinions, there should not have been very much need for preparation on the interviewees’ side.

Another ethical issue concerns the transcription of interviews, where it for example is important to be careful about the confidentiality of the interviewees and to store recordings and transcripts in a safe place (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009:186-187). Also, transcripts with incoherent language and inferior grammar

might be embarrassing for the interviewees, as people might not be aware of the fact that this is normal for oral language (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009:187). In my report, all citations from interviews used in the text has been made anonymous as well as translated into coherent language, for the benefit of the interviewees as well as the readers.

This study has been approved by the local ethics committee at Malmö University, Dnr. HS60-09/225:9.

7. Theoretical Framework

7.1 Learning Organisations

While studying the construction and real estate branches, I came to take an interest in how knowledge is acquired, spread and used by the agents who are working within these organisations. Learning and knowledge could certainly be seen as core issues in any organisation, and would therefore be considered an important feature when studying the obstacles and opportunities to making improvements in an organisation. The issue of learning in organisations therefore became the main topic of my analysis.

A learning organisation, as an ideal type, is an organisation that learns

continuously from its experiences in order to be able to solve its tasks in a better way. The management has an important function, for instance with developing a vision around the organisation's objectives, to encourage its members to discuss important matters openly, to support creativity, encourage risk taking and be generous with information. The members of a learning organisation have good knowledge about objectives and results, participate in frequent evaluations and are informed about any important issues that may arise (Nationalencyklopedin, 2009a).

The theories I will be using were originally brought forward in 1974 by Chris Argyris in cooperation with Donald Schön. For availability reasons the books I have used are the somewhat later writings of Argyris et al (1985; 1993; 1997; 2005), which I will use as a basis for the analysis, as they provide a compre-hensive, well-known and relevant theory on learning in organisations. As a support I will use the ideas of Senge (2006) and his description of “learning disabilities” as they are comprehensible and easy to translate to everyday situations. In this study the theories will be used to find patterns to explain for example how knowledge is used in organisations and which the main barriers of organisational learning are.

7.2 Action Science and Organisational Learning

Learning, according to Argyris (1993:3), is something that occurs when detecting and correcting errors. In a learning situation, a match is created when an action works according to the intention, and if not it is considered as a mismatch (Argyris, 2005:262). If a new outcome is produced for the first time, this is also considered to be learning (Ibid.). As learning according to these arguments is not only about having new ideas or developing new policies, but also about actively implementing these ideas or policies and evaluating their effectiveness, learning could thus be referred to as a concept of action (Argyris, 1993:2-3).

It is important to bear in mind that it is not the organisations that learn, but human beings acting as agents in the organisations. An organisation may provide a suitable learning environment for problem solving. It is also possible for individuals to bring various biases and constraints into an organisation, which might influence how problems are solved and which choices are made. (Argyris, 1997:8)

Throughout our lives we keep learning new things, and even if we might have experienced something similar before, no situation is exactly like another. We do, however, not start from the beginning every time we find ourselves in a learning situation, as this would be a waste of time and brain power. Argyris (1985:80-81) describes this phenomenon by way of that human beings, when designing their actions “…learn a repertoire of concepts, schemas, and strategies, and they learn

programs for drawing from their repertoire to design representations and action for unique situations”. These designs are our theories of action. Many of these actions are believed to be learned early in life (Argyris, 1993:20). In organi-sations, designs for action, such as policies and routines, are created as part of a master program to teach individuals to fulfil the goals of the organisation as efficiently as possible (Argyris, 2005:262).

7.2.1 Espoused Theories and Theories-in-use

All human beings have two different kinds of theories of action. Espoused

theories are the theories and values that we believe to be following, while

consultant was asked how he would act if having a disagreement with a client. According to him “…he would first state what he understood to be the substance

of the disagreement, and then discuss with the client what kind of data would resolve it. This was his espoused theory. But when we examined a tape recording of what the consultant actually did in that situation, we found that he advocated his own view and dismissed that of the client”. But what about these two theories, why do we claim to follow certain rules or to have certain values, when we are clearly acting otherwise? This is not just about the common dilemma of “saying this and doing that”, but it is really about two different theories of action, even if we are mostly not aware of having more than one. Both the espoused theory, which is the values we claim to have, and the theory-in-use, which is the theory we act according to, consist of actions we have designed ourselves and therefore are responsible for. The two theories might be consistent or inconsistent with each other to different degrees and it takes conscious reflection and active learning, to learn to be aware of these inconsistencies. (Argyris et al., 1985:81-83)

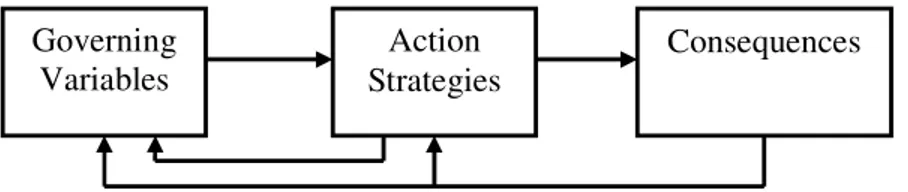

As is shown in figure 1 below, the governing variables of a theory-in-use are the values that provide the framework for the actions. We have many different governing variables that may be more or less influenced by any given action. A governing variable is not an absolute state, but can be seen as a continuum that should be kept within acceptable limits. As the governing variables are different, actions that raise the value of one may lower the value of another. Therefore there must often be a trade-off among the variables. (Argyris, 1997:217)

Action strategies are the moves a person makes in particular situations to keep the different governing values within an acceptable range. Action strategies have

Governing Variables

Action Strategies

Consequences

consequences, which may be intended or unintended. The intended consequences are those the actor believes will result. Unintended consequences, although unwanted, may still be designed. For example, if a person you talk to does not react in the way you anticipated, the consequences of the conversation might be different than you expected. (Argyris, 1997:217-218)

To better understand these concepts, here is an example from Anderson (1997: emphasis in the original):

A person may have a governing variable of suppressing conflict, and one of being competent. In any given situation she will design action strategies to keep both these governing variables within acceptable limits. For instance, in a conflict situation she might avoid the discussion of the conflict situation and say as little as possible. This avoidance may (she hopes) suppress the conflict, yet allow her to appear competent because she at least hasn't said anything wrong. This strategy will have various consequences both for her and the others involved. An intended consequence might be that the other parties will eventually give up the discussion, thereby successfully

suppressing the conflict. As she has said little, she may feel she has not left herself open to being seen as incompetent. An unintended consequence might be that the she thinks the situation has been left unresolved and therefore likely to recur, and feels dissatisfied.

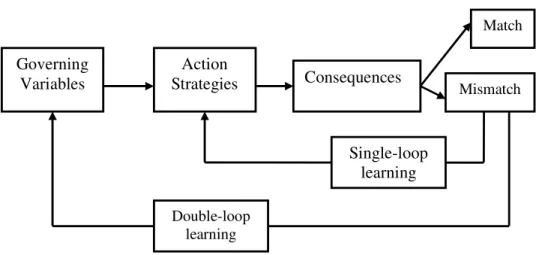

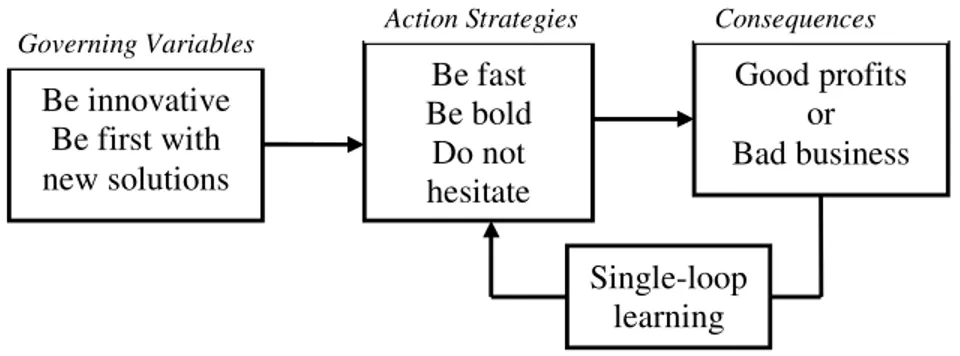

7.2.2 Single-loop and Double-loop Learning

When responding to a detected error, the most typical action would be to look for another action strategy that suits the prevailing governing variables (Argyris et al., 1985:85). An agent that has as a governing variable to suppress conflict would for example first try to avoid starting a controversial discussion, and if this fails he will try to change the topic and talk about anything the others would agree about (Argyris et al., 1985:85). This is an example of single-loop learning, where errors are detected and corrected without any changes in the governing values, which could be compared to double-loop learning where the process includes taking a step back and re-evaluating the governing variables of the situation (Argyris, 2005:262-263). An example of this would be that the agent mentioned in the case above would choose to have an open inquiry instead of suppressing the conflict.

To give another example, a thermostat on an electric heater is a single-loop learner. It is designed to regulate temperature by turning the heat up or down when needed. If a thermostat were a double-loop learner, it might start

questioning why you need to have 23˚C inside, and maybe even suggest a better solution to the heating issues.

It is important to remember, though, that a model as showed in figure 2 above is an ideal type. These two kinds of learning in reality exist on a continuum. There is also the possibility that values and strategies are nested and that an action may appear single-loop or double-loop depending on which governing variables are under examination. It would, for example, be possible that both “suppressing conflict” and “discussing openly” from the examples above would meet the same goal of “getting others to do what I think best”. (Argyris et al., 1985:86)

How can we know when we are facing problems that should be solved through double-loop learning? According to Argyris et al (1985:86-87) “…double-loop

problems requires dealing with the defences of human beings”. Situations that are about feeling threatened or embarrassed, things appearing to be difficult or even impossible to discuss, or when learning problems persist are often likely to need double-loop learning (Argyris et al., 1985:87).

Figure 2. Single-loop and double-loop learning Governing Variables Action Strategies Consequences Argyris et al (2005:263) Match Mismatch Single-loop learning Double-loop learning

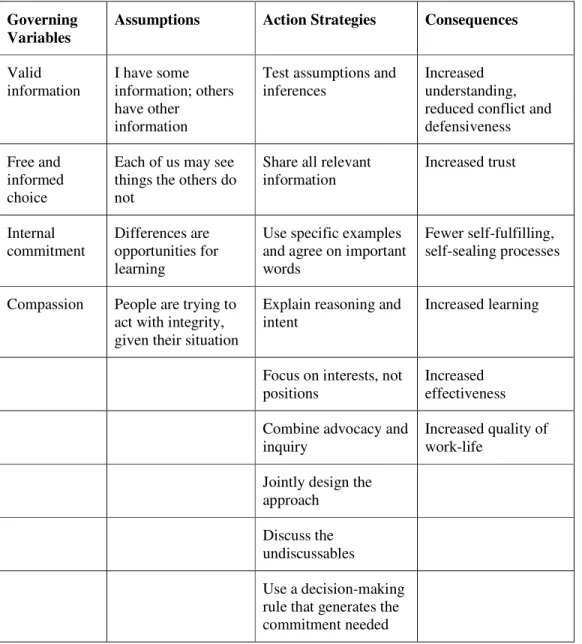

7.2.3 Model I and Model II Theories-in-use

The occurrence of differences between single-loop and double-loop learning could be explained by discrepancies in the agents’ theories-in-use. For this reason, Argyris (2005:266) differentiates between two models of action, where Model I is consistent with single-loop learning, while Model II fits better with double-loop learning. Model I is the dominant theory-in-use, and it shows no significant variance regarding gender, social status, wealth, race, education, age, culture or type of organisation throughout the world (Argyris, 2005:264). A typical Model I theory-in use would look as follows:

Table 1. Model I Theory-in-use Governing Variables Assumptions Action Strategies Consequences Achieve my goal through unilateral control I understand the situation; those who see it differently do not Advocate my position Misunderstanding, conflict and defensiveness

Win, don’t lose I am right; those who disagree are wrong Keep my reasoning private Mistrust Minimize expressing negative feelings I have pure motives; those who disagree have questionable motives

Don’t ask others about their reasoning

Self-fulfilling, self-sealing processes

Act rationally My feelings are justified

Ease in Limited learning

Save face Reduced effectiveness Reduced quality of work-life

Argyris 2005:264

Since Model I is the most common theory-in-use, the behaviour in most organisations will be in accordance with this model, which will lead to organisational defensive routines being created. An organisational defensive routine is “…any action, policy, or practice that prevents organizational

prevents them from discovering the causes of the embarrassment or threat”. Double-loop learning thereby is inhibited and both individuals and organisation is overprotected. (Argyris, 1993:53)

To be able to go from the dysfunctional Model I and aim for double-loop learning it is important to have a correct strategy. It is also essential to remember that Model II is not the exact opposite of Model I. Model II, as shown in table 2 below, strives to reduce the counterproductive factors, or prevent them from developing at all, using governing variables as valid information, free and informed choice and internal commitment. (Argyris, 2005:266)

Table 2. Model II Theory-in-use Governing

Variables

Assumptions Action Strategies Consequences

Valid information I have some information; others have other information

Test assumptions and inferences

Increased understanding, reduced conflict and defensiveness Free and

informed choice

Each of us may see things the others do not

Share all relevant information Increased trust Internal commitment Differences are opportunities for learning

Use specific examples and agree on important words

Fewer self-fulfilling, self-sealing processes

Compassion People are trying to act with integrity, given their situation

Explain reasoning and intent

Increased learning

Focus on interests, not positions

Increased effectiveness Combine advocacy and

inquiry

Increased quality of work-life

Jointly design the approach

Discuss the undiscussables Use a decision-making rule that generates the commitment needed

7.2.4 Learning Disabilities

When discussing learning theory, and especially the concepts of single-loop learning and Model I theories-in-use, I would think that Peter Senge’s (2006:18-25) descriptions of ”learning disabilities” would fit as good examples of single-loop learning, as they are presented in a detailed yet easily understandable way. According to Senge (2006:18) it is no accident that despite of their intelligent, committed members, most organisations tend to learn poorly. This comes for example from how the organisations are designed, how jobs are defined and from how all human beings have learned to think and interact, both as agents of their organisations as well as in other situations. The learning disabilities, as described in Senge (2006:18-25) are as follows:

1. I am my position –Most people think of their jobs as what they do every day, and not the greater purpose they may take part in. It is also common for people to see themselves as a part of a system where most things are outside their control. Hence, their sense of responsibility is quite limited. Bad results in the organisation probably happened because “someone screwed up”.

2. The enemy is out there – When something goes wrong, we all have a tendency to blame something or somebody outside ourselves.This is very common in some organisations, where for example some other department or organisation is always to blame.This way of thinking is related to “I am my position” because when we focus exclusively on our own position, we cannot see how far the consequences of our own actions might extend. In real life “out there” and “in here” might be quite closely related.

3. The illusion of taking charge – It is trendy to talk about taking charge and facing the problems aggressively, instead of allowing them to grow into crises. But sometimes, taking aggressive action is only “reactiveness in disguise”. Being truly proactive is more about being aware of how our own way of thinking contributes to our problems.

4. The fixation on events – We are prone to see life as a series of events that all have obvious causes. This way of seeing things might prevent us from discovering underlying long-term patterns and the causal relations behind them. As many threats today, such as environmental issues, are slow processes, it is important not to be fixated on short time events.

5. Maladaption to gradually building threats – We need to slow down and learn to pay attention to the slow, gradual processes. All big threats are not dramatic, but might be very subtle.

6. The delusion of learning from experience – It is not possible for us to learn everything from direct experience. Sometimes the consequences happen far away or sometimes in the future, where it is not possible for us to assess our effectiveness directly. Organisations might try to break down complex issues into pieces to make them more manageable, but that makes it difficult to get a general picture of the problem.

7. The myth of the management team – There is a myth that management teams always work together to find the best solutions for their organi-sations. In reality management meetings often revolve around saving face, laying blame, producing watered-down compromises and fighting for turf. “When was the last time someone was rewarded in you organization for

raising difficult questions about the company’s current policies rather than solving urgent problems?”

7.2.5 Interventions

Sometimes we feel helpless and even enslaved by different organisational pressures although we created them ourselves. So, why do “…human beings

create and maintain these policies and practices that they judged to be counterproductive?” To achieve a better understanding of these issues it is necessary to involve organisational learning, to be able to challenge the existing routines and the status quo of the organisation. (Argyris, 2005:261)