Degree Thesis (part 2)

for Master of Arts in Primary Education – Years 4-6

Teaching reading comprehension strategies

A study of Swedish elementary school teachers’ practices and perspectives

Author: Michaela Stolpe Supervisor: Parvin Gheitasi Examiner: Jeanette Toth

Subject/main field of study: English (or) Educational work / Focus English Course code: APG247

Credits: 15 hp

Date of examination: 2020-11-06

At Dalarna University it is possible to publish the student thesis in full text in DiVA. The publishing is open access, which means the work will be freely accessible to read and download on the internet. This will significantly increase the dissemination and visibility of the student thesis.

Open access is becoming the standard route for spreading scientific and academic information on the internet. Dalarna University recommends that both researchers as well as students publish their work open access.

I give my/we give our consent for full text publishing (freely accessible on the internet, open access):

Yes ☒ No ☐

Dalarna University – SE-791 88 Falun – Phone +4623-77 80 00

Abstract: Previous studies show that explicit teaching of reading comprehension strategies is beneficial for pupils’ reading comprehension in EFL. However, there appears to be a lack of studies about the topic in a Swedish

context. This study investigates how teachers in years 4-6 in one elementary school in Sweden work towards improving their pupils’ reading comprehension in EFL. Further, the study explores what perspectives the teachers have on teaching reading comprehension strategies in EFL. The four participating teachers all have a teacher’s degree and experience with teaching EFL in years 4-6. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with four teachers and complemented with classrooms observations with two of the interviewed teachers. The results suggest that the teachers believe teaching reading comprehension strategies in EFL is important. Further, the results indicate that the participating teachers work with reading comprehension strategies that according to previous studies are beneficial for pupils’ reading comprehension. In addition, the teachers described working with similar strategies and teaching methods in the Swedish subject. Therefore, comparative studies between the Swedish subject and EFL to further investigate if the same reading comprehension strategies are beneficial in both subjects is recommended.

Keywords: English as a foreign language, reading comprehension, reading comprehension strategies, teachers’ perspectives.

1. Introduction...1

1.1. Aim and research questions... 2

2. Background...3

2.1. English in society according to official documents...3

2.2. Strategies in Swedish steering documents...4

2.3. Definition of terms... 5

2.3.1. Reading comprehension... 5

2.3.2. Strategies... 5

2.3.3. Metacognition... 6

2.3.4. English as a Foreign Language vs English as a Second Language...6

2.4. Previous research... 7

2.4.1. Reading comprehension strategies...7

2.4.2. Metacognitive strategies - key to reading comprehension...7

2.4.3. Reciprocal teaching... 8

2.4.4. Think aloud method... 9

2.4.5. Balanced comprehension instruction...9

2.4.6. Summary of reading comprehension strategies...10

2.4.7. Teachers’ perspectives... 10

2.4.8. “Good” and “poor” readers... 11

3. Theoretical Perspectives...13

3.1. Vygotsky’s Sociocultural theory...13

3.1.1. Zone of Proximal Development and Scaffolding...14

3.2. Social Cognitive Theory... 14

4. Method and material...16

4.1. Choice of methods... 16

4.1.1. Interviews... 17

4.1.2. Observations... 18

4.1.3. Validity and Reliability... 18

4.2. Ethical considerations... 20 4.3. Participants... 20 4.4. Implementation... 21 4.4.1. Pilot study... 21 4.4.2. Main study... 21 4.5. Method of analysis... 23 5. Results...24

5.1. Working with reading comprehension...24

5.1.1. “Like in Swedish”... 24

5.1.2. Reading the text... 25

5.1.3. Asking questions... 26

5.1.4. Summarizing and translating...27

5.2. Teachers’ persepectives... 28

5.2.1. In EFL or in other subjects... 28

5.2.2. The importance of the teacher...29

5.3. Summary of results... 30

6. Discussion...30

6.1. Results discussion... 30

6.1.1. Working with reading comprehension...31

6.1.2. Teachers’ perspectives... 33

6.2. Method discussion... 35

6.2.1. Method and instruments... 36

6.2.2. Validity, reliability and ethical considerations...37

References...41 Appendices...45 Appendix A... 45 Appendix B... 46 Appendix C... 47 List of tables Table 1 Participants... 21

Table 2 Approaching a new text... 25

1.

Introduction

Reading comprehension is fundamental for learning in all subjects and has been of interest to researchers for several decades (Westlund, 2016). Research shows that to achieve good reading comprehension pupils will benefit from receiving instruction on how to use reading comprehension strategies properly (Malmberg & Bergström 2000, p. 176). Moreover, reading comprehension in English should be of high value considering the English language’s status as a Lingua Franca and the amount of written information in English pupils are exposed to daily. Teachers teaching English in Sweden are obliged to teach: “Strategies for understanding significant words and context in spoken language and texts, for example by adapting listening and reading to the form and content of communications” (Skolverket 2018, p. 36.). Furthermore, pupils should be educated in strategy use as well as being made aware of useful strategies (Skolverket 2017, p. 13). However, in my teacher education I have received little training in how to teach these strategies to pupils and how to make them aware of their strategy use. Likewise, I have observed less explicit reading comprehension strategy instruction in English at the school where I had my internship. Nevertheless, Swedish pupils are doing well in their reading comprehension tests in the National Exams in English (Skolverket, 2019). This could indicate that they might be taught reading comprehension strategies in their classrooms. There are several methods available to teach reading comprehension strategies in both elementary school and in higher education. A number of studies have shown that especially teaching metacognitive strategies is key to improving pupils’ reading comprehension (e.g. Feng-Teng 2020; Dabarera, Renandya and Zhang 2014; Gutiérrez Martínez and Ruiz de Zarobe 2017). Despite this, I have struggled to find research on what strategies are being taught by teachers in Sweden.

I argue that the topic of what strategies are being taught in English as a Foreign Language-classrooms in Sweden aiming at improving reading comprehension is a topic relevant to research. This is because of the importance of the ability to understand English texts in today’s society and the findings of the benefits of teaching strategies. Moreover, it appears that there is a lack of research in a Swedish context on the topic, but pupils are still doing well on their reading comprehension tests in year 6. Considering this, there is a gap of knowledge on what reading comprehension strategies are being taught.

1.1.

Aim and research questions

The aim for this paper is to learn about practices and perspectives elementary teachers in Sweden have concerning working with reading comprehension in English as a Foreign Language. More specifically, the study aims to answer the following research questions:

How do teachers in years 4-6 in one elementary school in Sweden work with reading comprehension within their EFL teaching?

How do these teachers view working with reading comprehension strategies within the EFL classroom?

2.

Background

This section will present overview of official documents relevant to this study as well as the definitions of key terms. Previous research relevant to this study will also be presented.

2.1.

English in society according to official documents

In an increasingly global world where English is a Lingua Franca, the ability to read and understand English is essential for an active member of society. This is emphasized in the commentary material of the English curriculum (Skolverket 2017, p. 6), where English is considered an essential tool for an active member of today’s society. Additionally, The European Union (EU 2018) states eight key competences for each member to achieve in order to become a successful citizen.

One of the key competences stated by The European Union (EU 2018) is multilingual competence. Multilingual competence does not specifically call for knowledge in English but considering the English language’s status as a Lingua Franca it is an important language to know. Multilingual competence is of high relevance to this paper since it is about understanding language. To achieve multilingual competence, it is written - amongst other aspects - that individuals should be able to read and understand texts, as well as being able to use tools appropriately to learn (EU, 2018). “Tools to learn” is another term for strategies. Hence, the interpretation made from this is that reading strategies are a part of achieving multilingual competence as described by the European Union.

Similarly, the commentary material explains that it is through English pupils will be able to access and understand information from for example EU or other organizations that use English as a primary language (Skolverket 2017, p. 6). However, even for a reader who would be considered proficient, reading governmental texts, and understanding them, is not always easy and often requires a lot of work. Considering this, reading strategies should be an essential part of the English education. Yet, in the commentary material, only one example of a strategy is mentioned – guessing competence, meaning the ability to draw conclusions even if the text is inconsistent (Skolverket 2017, p. 14). In addition, the Swedish Education Act chapter 10 §2 (SFS 2010:800) states that a purpose of the education is to give pupils a good foundation for further education. Considering many higher educations are conducted in English and with

academic texts written in English - in Sweden as well as abroad - reading strategies in English would be essential for a person interested in higher education.

2.2.

Strategies in Swedish steering documents

The syllabus for English in the Swedish curriculum (Skolverket, 2018) as well as the commentary material (Skolverket, 2017) mention “strategies” numerous times in relation to teaching and learning English. A relevant example for this paper is strategies for understanding while reading, which is part of the core content for grade 4-6 (Skolverket 2018, p. 36). Further, the knowledge requirements for grade E at the end of year 6 states that “To facilitate their understanding of the content of the spoken language and texts, pupils can choose and apply a strategy for listening and reading” (Skolverket 2018, p. 38). Being part of both the core content and the knowledge requirements, the assumption that strategies are important in English as a foreign language teaching can therefore be made. However, only one example of a strategy is mentioned, giving little guidance to teachers as to how and what to teach.

The one strategy mentioned, and somewhat elaborated, in the commentary material is “guessing competence”. Here, “guessing competence” refers to the ability to draw conclusions even if the text is inconsistent (Skolverket 2017, p. 14). The other strategies pupils are supposed to learn in order to “choose and apply a strategy for listening and reading” is not explicitly explained. In addition, it is suggested that pupils through education should receive guidance to raise their awareness about strategy use, since it is important for them to know what strategies they use and can use (Skolverket, 2017, p. 14). There are no other strategies than “guessing competence” mentioned for reading, but the document indicates that several should be taught. To know about other relevant strategies teachers would need to search further.

The commentary material also comments on the knowledge requirements and explains that there is a progression throughout the grades as to how pupils choose and use strategies to understand written and spoken word (Skolverket 2017, p. 19). This could indicate that pupils in grade 6 are not yet expected to have an armory of strategies to use. This is of relevance to this study’s aim to investigate what strategies are being taught in year 4-6.

In conclusion, both the Swedish official documents and the European Union consider proficiency in languages a key to be an active member of society. English, being the official language used to communicate between countries, is therefore important for everyone.

Moreover, the curriculum and commentary material for English mention strategies numerous times in relation to reading, and therefore strategies can be considered of high value in English education in a Swedish context. However, only one example of a strategy is mentioned in relation to reading, giving little guidance to teachers as to how and what to teach. Considering the lack of examples of strategies to teach in the steering documents, research on what strategies elementary teachers in Sweden do teach is of relevance.

2.3.

Definition of terms

In this section, some relevant terms will be defined. 2.3.1. Reading comprehension

The term reading comprehension is complex and debated among scholars. Hence, the definition can differ between, for example, a sociocultural perspective and a cognitive perspective. One example of a definition is “The simple view of reading” (Gough and Tunmer, 1986) where it is suggested that reading comprehension is dependent on both decoding and listening/language comprehension. If the reader lacks in either decoding or listening/language comprehension it is impossible to achieve reading comprehension.

Another definition is by Sweet and Snow (2002, p. 23-24) who define reading comprehension as a process where meaning of a text is created through interaction between the reader and the text. They suggest that the sociocultural context has impact on the reader’s understanding and vice versa. This means that neither the reader nor the text stands alone. Further, it is explained that to comprehend, the reader will need to possess various abilities such as cognitive capacities, pre-knowledge, vocabulary, and fluency - to name a few (Sweet and Snow 25-26). For this paper, the definition by Sweet and Snow (2002) is chosen because it acknowledges both the sociocultural aspects as well as the cognitive aspects.

2.3.2. Strategies

Westlund (2016, p. 65) defines strategies as the mental tools used by a learner to achieve a certain ability. This is in line with the curriculum’s definition of strategies; different methods to learn and acquire the language (Skolverket 2017, p. 13). Therefore, the definition is relevant in a Swedish context. A more elaborated and official definition of strategies for this study is one of O’Malley & Chamot (1990) where strategies for language learning can be divided into socio-affective, cognitive, and metacognitive. Socio-affective strategies are about working together

and asking for help. Examples of cognitive strategies are analyzing and drawing conclusions. Metacognitive strategies are about reflecting on one’s own learning process and monitoring it. The reason for choosing this definition is that it is universally used and accepted by a number of Swedish scholars (e.g. Tornberg 2015; Malmberg 2000; Westlund 2016).

2.3.3. Metacognition

According to Flavell (1979), metacognition is thinking about one’s own thinking and monitoring cognitive abilities and processes. In relation to strategies, it means being able to consciously choose, use and evaluate appropriate cognitive strategies for learning. Or in short, monitor the learning.

To explain metacognition, and in doing so, metacognitive strategies, Flavell’s (1979) theory on metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive experiences will be used. The reason for choosing this definition is that a number of studies referred to in this paper (e.g. Feng-Teng 2020; Dabarera et. Al. 2014; Persson 1994) have chosen Flavell’s definition, and to avoid confusion it seems appropriate to use the same definition. Second, the explanation correlates with how the chosen definition of learning strategies (O’Malley & Chamot 1990) describes metacognitive strategies.

2.3.4. English as a Foreign Language vs English as a Second Language

As defined by Pinter (2017, p. 200) English as a foreign language (EFL) refers to learning English in a school context in a country where English is not the primary language used in society. Even though English is used in the Swedish society in several contexts it is still in a learning context considered a foreign language.

English as a second language (ESL) is sometimes used as an equivalent to EFL, which is not quite the case. Pinter (2017, p. 200) explains ESL as when pupils with a different mother tongue than English learn English in a school context where it is the primary language of the country and the school.

The study will focus on a Swedish learning context where English is considered a foreign language. Hence, the term chosen for this study is EFL.

2.4.

Previous research

This section will present an overview of some research previously conducted about the topic of this thesis. Since this study aims to research what kind of strategies are being taught by EFL-teachers in Sweden, research on strategies possible to teach are needed to compare with the empirical data.

First, an overview of some established ways to teach strategies is presented, with no ambition to account for all ways possible to teach strategies. Second, benefits of teaching metacognitive strategies are presented. Third, an attempt to highlight “good” and “poor” readers in relation to strategy instruction is made. Finally, some teachers’ perspectives are presented.

2.4.1. Reading comprehension strategies

Below, some general findings from previous studies about teaching reading comprehension strategies are being presented. This section is of high relevance to the aim of this paper, since it will give opportunities to compare the empirical data collected for this study with previous research on the topic. By knowing which strategies and methods to teach are supported by research, it is also easier to formulate relevant interview questions and create an observation guide. First, studies about metacognitive strategies conducted with EFL-pupils are presented. The studies following are unfortunately not conducted with EFL-pupils since it appears that there is a lack of studies in this area. The pupils have English as their first language (L1) and learn English, or Swedish as their L1 and learn Swedish. However, since the findings of the studies with EFL-pupils match the results of the studies with L1 that are also concerning metacognitive strategies, the choice was made to keep the studies as they bring insights to the topic. It was also suggested by Cummins (1979) that abilities learned in one language can be transferred to a different language, meaning that reading comprehension strategies learned in L1 could be possible to use by pupils in for example EFL.

2.4.2. Metacognitive strategies - key to reading comprehension

To successfully help pupils improve their reading comprehension in EFL, teaching metacognitive strategies is key. Several studies have shown that this is the case when comparing a test group to a control group where the test group received metacognitive instruction or teaching, and the control group did not. For example, Feng-Teng (2020), concludes that explicit metacognitive training was beneficial to 5th grade pupils in Hong-Kong and enhanced their

reading ability. The study was conducted with 25 test pupils and 25 control pupils. The method used had three phases. First, the pupils read a text and answered questions about the text. Second, they were encouraged to reflect on their own about their comprehension. For this step, the pupils had help from a printed list with metacognitive prompts. Third, the pupils discussed their reflections. This phase is similar to the think aloud method, which will be further explained below. Similarly, Dabarera, Renandya and Zhang (2014) show that explicit strategy instruction was beneficial for the reading comprehension in English as a second language for year one secondary students in Singapore, the majority being 12 years old. The method used in the study was Reciprocal Teaching, which is further described below. In addition, similar results were found by Gutiérrez Martínez and Ruiz de Zarobe (2017). Their study of 145 Spanish 5th

graders shows that teaching reading strategies has significant results on EFL-pupils’ reading comprehension as well as their ability to be more independent readers. The strategies taught in the study were: activate previous knowledge, predict what the text is about, observe the text structure, observe text type and guess from the context.

2.4.3. Reciprocal teaching

Reciprocal teaching is one method to teach reading comprehension strategies. It was developed by Palinscar and Brown in 1982 in a pilot study and then studied and evaluated in two studies in 1984 (Palinscar and Brown 1984, pp. 124-125). The first study was conducted by a researcher with a test group and a control group and the second by teachers in regular classroom settings. Reciprocal teaching is based on how “good” readers use strategies to make comprehension while reading. Palinscar and Brown (1984, p. 121) list four strategies essential to teach: predicting, questioning, clarifying, and summarizing. Additionally, reciprocal teaching was inspired by Vygotsky’s sociocultural perspective and the scaffolding approach, meaning an expert demonstrates to - in time - make the learner more independent:

The teacher models and explains, relinquishing part of the task to the novices only at the level each one is capable of negotiating at any point in time. Increasingly, as a novice becomes more competent, the teacher increases her demands, requiring participation at a slightly more challenging level, that is, one stage further into the zone of proximal development (Palinscar and Brown 1984, p. 169).

In their study Palinscar and Brown (1984, p. 167) found that all of the 24 students - the majority American 7graders - but one improved their comprehension. Further, the effect of the training lasted for several weeks and there was no difference in success depending on whether the teaching was conducted by a researcher or a regular teacher. As mentioned above, the method

was also found beneficial by Dabarera, Renandya and Zhang (2014). This could indicate that the method is beneficial in both English as a primary language (L1) and in EFL.

2.4.4. Think aloud method

The think aloud method - where the goal is to make pupils better at monitoring their own comprehension - was developed by Davey (1983). In a similar manner to reciprocal teaching the pupils learn by imitating an expert and gradually learn to use the strategies more independently. Five steps are explained by Davey (1983, p. 45) and the teacher is encouraged to first model all steps aloud before letting the pupils try them in pairs and finally on their own. The five steps include making predictions, explaining images in ones’ head while reading, linking previous knowledge to the text, verbalizing confusing sections of the text, and demonstrating how to make corrections when not understanding.

Think aloud as a promising method to improving pupils’ reading comprehension is supported by findings in a number of studies (e.g. Anderson and Roit 1993; Caldwell and Leslie 2010). In their study with nine experimental and seven control teachers together with their pupils aged 12-16, Anderson and Roit (1993, p. 134) found substantial improvement in reading comprehension for the pupils after having received teaching in thinking aloud. Likewise, Caldwell and Leslie (2010, p. 334) found in their study with 68 pupils in middle school that the pupils made more inferences – indicating improved reading comprehension – while using thinking aloud in comparison to when not thinking aloud.

2.4.5. Balanced comprehension instruction

To make teaching strategies successful, more than just good instruction is needed (Duke and Pearson 2008, p. 108) A nourishing classroom climate where plenty of time is devoted to reading is also required as well as reading with a clear purpose, discussions of texts and own text writing. This, together with good instruction is according to Duke and Pearson (2008, pp. 108-109) a winning concept for teaching reading comprehension strategies. In their article where they discuss previous research on effective methods to teach reading comprehension strategies, Duke and Pearson (2008, p. 109) argue that a good method for instruction starts with the teacher explaining and modelling a strategy, followed by cooperative work aiming towards independent use of strategies. Emphasized is also the importance of teaching multiple strategies - a strategy is not particularly successful on its own (Duke and Pearson 2008, p. 109). Suggested

are six reading comprehension strategies, not too different from the strategies mentioned above in previous methods:

To summarize, we have identified six individual comprehension strategies that research suggests are beneficial to teach to developing readers: prediction/prior knowledge, think-aloud, text structure, visual representations, summarization, and questions/questioning (Duke and Pearson 2008, p. 114).

2.4.6. Summary of reading comprehension strategies

As presented in the research above, teaching reading comprehension strategies – in particular metacognitive strategies to make the pupils aware of the strategies and their own learning - is an important tool for improving reading comprehension for pupils (e.g Duke and Pearson 2008; Davey 1983; Palinscar and Brown 1984; Anderson and Roit 1993; Caldwell and Leslie 2010; Feng-Teng 2020; Dabarera, Renandya and Zhang 2014; Gutiérrez Martínez and Ruiz de Zarobe 2017). Further, working with a scaffolding approach where the teacher models to make the pupils more independent readers is a well-working method (e.g. Duke and Pearson 2008; Davey 1983; Palinscar and Brown 1984). Lastly, the research also points to a few specific strategies beneficial to teach. The strategies mentioned in more than one study are summarizing, predicting, thinking aloud or verbalizing, questioning, and using previous knowledge (e.g. Duke and Pearson 2008; Davey 1983; Palinscar and Brown 1984).

2.4.7. Teachers’ perspectives

Different approaches on how to teach reading comprehension strategies and the advantages in doing so have been listed above. There are a broad range of methods available and therefore the research needed to be narrowed down before presenting. However, research about what methods and strategies teachers teach and how they experience teaching strategies, has shown to be a much smaller field of research. Therefore, it is difficult to present a complete and reliable picture of this topic. In addition, teachers’ perspectives on teaching reading comprehension in EFL has appeared to be an even smaller field. Therefore, studies concerning teaching reading comprehension in first or primary languages will instead be presented. Below are a few examples presented and no effort in trying to present a generalizable picture is made. Teachers appear to be struggling with achieving balanced reading instruction. This is indicated by findings by Concannon-Gibne and Murphy (2012) who conducted a questionnaire with 400 Irish primary school teachers and interviews with 12. The study shows that the focus of reading instruction and teaching was phonics and decoding in early years and that reading in higher

grades mainly aimed at reading for pleasure. Comprehension and vocabulary therefore held a secondary role. Moreover, it is discussed in the study that there is not enough training for teachers in the field of reading comprehension in order to teach reading strategies (Concannon-Gibne and Murphy 2012, p. 445).

Results show that teaching in Sweden is also lacking in instruction towards achieving reading comprehension for pupils in the Swedish subject and it appears to be a lack of research about how teachers in Sweden teach reading comprehension in EFL. However, findings by Tengberg and Olin Sheller (2013, p. 698) who conducted interviews with three teachers and 37 pupils in grade 7 support that there is a lack of instruction of reading comprehension strategies in the Swedish subject. According to the study, the pupils’ previous education in grade 4, 5 and 6 had not made the pupils accustomed working with reading comprehension strategies. Accordingly, Westlund (2013, pp. 277-278) states in her thesis that teachers in Sweden’s approach to reading comprehension in the Swedish subject seemingly is to let pupils work with answering questions about texts and then correct the answers. This method is somewhat questioned by Westlund (2013) for not being a beneficial method. By contrast, the Canadian teachers in the same study held an approach where they actively supported reading comprehension by using the method Reading Power, which is similar to Reciprocal Teaching. In short, Reading Power was developed by Adrienne Gear and is based on what good readers do (Gear 2015, pp. 11-13). The method also teaches the pupils metacognitive thinking.

2.4.8. “Good” and “poor” readers

First, an explanation of the terms “good” and “poor” readers is called for. Here, good and poor only refer to the reading ability and components of this possessed by pupils, whether it being decoding, fluency or comprehension, and not to any other attributes of said pupils.

Research shows that there are differences between “good” and “poor” readers and the way they use strategies to comprehend what they read (e.g. Davey 1983; Persson 1994; Duke and Pearson 2008). According to Davey (1983, p. 45), “poor” readers often lack the ability to make predictions, explain images in their head while reading, draw on prior knowledge, supervise their comprehension or use strategies to correct difficulties in the text. In contrary, Duke and Pearson (2008, p. 107) list what “good” readers do. Examples - to name a few and compare to what “poor” readers do not do - are making predictions, activating prior knowledge,

understanding and fixing mistakes, and reading different texts differently. In other words, there are differences in what cognitive and metacognitive abilities “good” and “poor” readers possess. “Poor” readers can, and often do, possess both cognitive and metacognitive abilities. However, there might be a difference in the correlation between these in comparison to “good” readers. Persson (1994, p. 3) wrote her doctoral thesis on the difference in metacognitive competence between “good” and “poor” readers. Amongst the 53 Swedish pupils in grades 5 and 8 it was found that “good” readers tended to have good correlation between their cognitive and their metacognitive abilities. They had also learned to learn – or monitor their own learning. The case was not the same for the “poor” readers who could have cognitive and metacognitive skills but lacked a correlation between them (Persson 1994, pp. 203-204).

Another difference between “good” and “poor” readers is the way they, in some cases, respond to and benefit of reading strategy training. As found by Müller, Richter, Križan, Hecht and Ennemoser (2015) in their study on 235 German 2nd graders, strategy training could even be

harmful for children who were both “poor” readers and had an inefficient word recognition process. In contrary, both “poor” readers that had a more efficient word recognition process and for “good” readers strategy training was beneficial for their reading comprehension (Müller et. Al 2015, p. 60). This is an interesting finding since most other studies referred to in this paper draw general conclusions based upon group results.

To summarize, these findings suggest that metacognitive training is beneficial for most pupils, though one study argues that it in some cases can be non-beneficial to some pupils. Additionally, “good” and “poor” readers differ in what abilities they possess and what strategies they use.

3.

Theoretical Perspectives

Below, the theoretical perspectives this thesis holds will be presented. First, Vygotsky’s Sociocultural theory, including scaffolding and The Zone of Proximal Development will be introduced. Second, Bandura’s view on Social Cognitive theory will be accounted for briefly.

3.1. Vygotsky’s Sociocultural theory

The sociocultural theory was developed in contradiction to behavioristic theories where conditioning is considered the way which humans learn through. According to the sociocultural theory, cultural abilities such as reading and writing, are not taught through conditioning. Those abilities are of a higher psychological level and are taught by mediating (Säljö 2014, p. 298). Mediating is explained by Säljö (2014, pp. 298-299) as how human beings use tools, such as language and symbols, to learn and make understanding of the world. Moreover, the main concept of sociocultural theory is that humans learn cultural abilities through interaction with other human beings (Säljö 2014).

Lev Vygotsky is regarded the Sociocultural theory’s founding father (Säljö 2014, p. 298). According to Vygotsky (1978, pp. 27-28; 33; 57), language is one of the most important tools for humans. It is through language we communicate and create meaning. This is in line with the aim for the English syllabus where language is described as the primary tool for learning, communicating, and thinking (Skolverket 2019, p. 34).

Previously in this thesis, methods to teach reading comprehension strategies have been accounted for. Examples of these methods are Reciprocral Teaching and Thinking Aloud, where language in social context between teachers and students plays a vital role. The students are taught to plan their reading and monitor their learning process through these methods. This is very similar to how Vygotsky (1978, pp. 28-29) explains that children learn to use language as a tool to solve problems and monitor their behavior before doing.

Additionally, Vygotsky (1978, p. 57) states that “all higher functions originate as actual relations between human individuals”. Further explained by Säljö (2014, p. 303), this means that functions such as thinking and advanced remembering, are developed through communication between people. To connect to this thesis, reading comprehension strategies can

be considered “higher functions” and should therefore, according to sociocultural theory, be developed in a social context between people.

3.1.1. Zone of Proximal Development and Scaffolding

A key concept of Sociocultural theory is that the child is dependent of an adult or a more competent peer for support in order to develop further (Säljö 2014, p. 304). A number of ways to teach strategies accounted for in the previous research section of this thesis, also hold this approach to learning (e.g. Duke and Pearson 2008; Davey 1983; Palinscar and Brown 1984). Moreover, Vygotsky (1978, pp. 84-85) considered human beings to be in a constant process of learning and developing. When a person is most open to instruction, they can successfully reach knew knowledge with the help from a teacher or a peer. This is called the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) and is determined by the span of where the child is in their development, to where they can reach (Säljö 2014, pp. 305). The key is for the teacher to be observant of the pupil’s ZPD to give the right support and plan their lessons accordingly. The Zone of Proximal development is therefore relevant to acknowledge both when discussing teachers’ perspectives on teaching and how they teach.

The support given within the ZPD is known as scaffolding. Vygotsky (1978) emphasizes the important role the teacher plays for the pupil to reach new knowledge – hence, learning in a sociocultural context with the help of other people. Säljö (2014, p. 306) explains how the teacher or a more competent peer first gives a lot of support with the goal for the pupil to later manage the task on their own. As explained by Gibbons (2013, p. 39), scaffolding should be temporarily and future oriented. It should help the pupils achieve higher goals by building on their previous knowledge.

3.2.

Social Cognitive Theory

According to the social cognitive theory, humans are shaped by both behavioral and cognitive aspects, as well as by external factors (Bandura 1986, p. 18). Similar to Vygotsky (1978), Bandura (1986, pp. 18-19; 454; 498) highlights the human mind, and in particular humans’ linguistic ability and abstract thinking, as being important tools for human action and interaction. Humans are prone to testing scenarios in their minds before acting and they motivate and guide their choices and actions by thinking ahead and drawing on previous knowledge. As mentioned previously in this thesis, drawing on previous knowledge and

predicting are two important strategies to teach pupils in relation to reading comprehension (e.g. Duke and Pearson 2008; Davey 1983; Palinscar and Brown 1984). Further, Bandura (1986, pp. 19-20) explains that learning might occur by own experiences or by observing someone else. It is suggested that certain skills, such as linguistic skills, can only be learned by modeling. Hence, the social context of learning is as important as the cognitive abilities.

Another important human skill is according to Bandura (1986, p. 21) metacognitive ability. As mentioned previously in this thesis, metacognitive strategies are also important for improving reading comprehension (e.g. Feng-Teng 2020; Dabarera, Renandya and Zhang 2014; Gutiérrez Martínez and Ruiz de Zarobe 2017). Through metacognition, humans can oversee their own thinking and judge their own abilities. However, possessing metacognitive skills and using them is not the same as using them efficiently (Bandura 1997, p. 223). To enhance the self-efficacy, and by doing so be more efficient users of strategies, pupils can be taught how to self-guide through verbalizing their thoughts while performing a task (Bandura 1997, p. 224). In comparison to reading comprehension strategies, this is very similar to the teaching model of Think Aloud, which has been accounted for previously (Davey, 1983).

In relation to strategy teaching, Bandura (1997, p. 225) emphasizes the importance of adapting the strategy use to certain circumstances. Individuals must discover what strategies works for them in different situations by drawing on previous knowledge and efficiently use their cognitive skills. This means that teachers need to consider that different strategies work for different pupils and implement this in their teaching of strategies.

4.

Method and material

In this section, the choice of methods to collect data for this thesis will be presented and argued for. The instruments used will be explained and the selection of participants will be presented. Furthermore, ethical considerations as well as validity and reliability concerning the chosen methods will be discussed. Lastly, the implementation of the study and the method of analysis will be accounted for.

4.1.

Choice of methods

A distinction between qualitative and quantitative methods is often made. Quantitative methods are used when researching something that can be quantitatively measured, e.g. how many, how often or to what extent something occurs. An example of a quantitative method is questionnaire which is often distributed to a large group of respondents (Larsen 2018, p. 31.). Qualitative methods on the other hand, are about finding out informants’ thoughts or feelings about a certain phenomenon (Jacobsen 2015, p. 15). Examples of qualitative methods are interviews and observations. Because the transcribing of interviews is very time consuming, interviews are usually conducted with a smaller group of informants, as opposed to a questionnaire which usually have more informants (Stukát 2011, p. 45).

The choice of method depends on the research questions of the study (Stukát 2011, p. 41). In case for this study, the questions are about teachers’ perspectives on teaching reading comprehension strategies, and how the same teachers work with improving their pupils’ reading comprehension in EFL. These questions could possibly be answered with the use of a questionnaire, but it would be more difficult to get answers with depth (Stukát 2011, p. 49). Further, Stukát (2011, p. 39) suggests that when researching something that has not been thoroughly researched before, qualitative methods are more appropriate to use. The author of this paper has not been able to find much research conducted about teaching reading comprehension strategies in EFL in a Swedish context. Lastly, perspectives is in this case a different word for feelings or thoughts. Therefore, the qualitive methods interviews and observations were chosen to collect data for this study.

An argument for using more than one method is that it can give a deeper understanding of the researched phenomenon. This is called method triangulation (Larsen 2018, p. 38, Stukát 2011,

pp. 41-42). By using both interviews and observations, a deeper understanding about the teachers’ perspectives and their ways to improve reading comprehension might be achieved. Further, the two methods can show different aspects of the phenomenon. For example, observations can both confirm an informant’s statement or show something different. Below, a more detailed description of each method will be presented.

4.1.1. Interviews

Interviews can differ in how they are planned and conducted. They can be structured, semi-structured or un-semi-structured. In a semi-structured interview, the same questions are asked in a pre-determined order to all informants, while in a semi-structured or an un-structured interview, the order is not as necessary and follow up questions can be asked. Further, in a semi-structured or an un-structured interview, the informant can speak more freely about the topic of interest to the interviewer (Larsen 2018, pp. 138-140; Stukát 2011, pp. 43-44). The advantages of choosing a semi-structured interview is that the informants can elaborate their answers and the interviewer can ask questions that arise during the interview. However, the disadvantages are that the interviewer needs to be well prepared and skilled to gain the information needed for the study. Kihlström (2007a, p. 50) emphasizes the importance of not asking leading questions but allowing the informant to speak from their own experience and points out that this ability requires good knowledge about conducting interviews. In addition, the process of analyzing the material afterwards is time consuming (Larsen 2018, p. 139; Stukát 2011, p. 45).

For this study, a semi-structured approach to interviews was used. By choosing this method, the informants were given the opportunity to give examples on reading comprehension strategies not explicitly asked about. Because it is a narrow field of research in the Swedish context, it would be difficult to make a full-covering form with questions for the informants to answer, since they might use teaching methods with less coverage in previous research.

To register the answers of the informants, the interviews were recorded on a cellphone. Taking notes during a semi-structured interview can be difficult since focus should be on the conversation between the interviewer and the informant and not on taking notes (Stukát 2011, p. 45). In addition, Kihlström (2007b, p. 232), suggests audio-recording for higher reliability. Further, the interviews were transcribed.

For this study, an interview guide was constructed (See Appendix B). The interview guide was somewhat inspired by Westlund’s (2013) interview guide from her study regarding reading comprehension strategies. The interview guide for this study consisted of 15 questions. The first three questions were general background questions about the informants. These were followed by questions about their English teaching and more specific questions about reading comprehension and reading comprehension strategies. In order to compare the results with previous research, strategies presented in previous research were included in the questions. In addition, a number of follow-up questions were asked to each informant. The interview method and interview guide were tested in a pilot study.

4.1.2. Observations

Observations were used as a complement to the interviews. By comparing the observations to the interviews, one method could either confirm findings from the other method, or find new aspects. According to Stukát (2011, p. 55), observations are used to see what people do and not just what they say they do. Informants can have reason to not be completely truthful in interviews and in those cases, observations can be useful to find out more. There are also cases where an informant is not aware of their behavior in situations, and therefore tells a different story (Larsen 2018, p. 150).

Similar to interviews, observations can be more or less structured. In a more un-structured observation, the observer takes notes on-going throughout the observation about what they find interesting. In a more structured observation, the observer will use an organized scheme to answer pre-determined questions. In this study, a semi-structured approach to the observations was used. This means that the observations were conducted with specific themes and keywords in mind - an observation guide (See Appendix C). This approach allowed for more flexibility to note unexpected events during the observations (Stukát 2011, p 56; Larsen 2018, pp. 150-151). A pilot study was done to test the observation guide and give practice to the observer. Stukát (2011, p. 56) explains that observations are time-consuming and require the observer to be well prepared. For this reason, a pilot study is desirable.

4.1.3. Validity and Reliability

Both validity and reliability are of importance to the quality of a study and must be considered during the entire research process (Larsen 2018, p. 129). Below, validity and reliability, as well as how they have been considered for this study, will be discussed.

For a study to achieve high validity, the researcher must conduct the study in such manner that the investigated material is what was aimed to be investigated. In other words, the research must be relevant to the aim and research question of the study (Larsen 2018, p. 129; Thornberg and Fejes 2019, p. 275). Further, the researcher must be able to account for how the research has been conducted and how the conclusions have been made (Larsen 2018, p. 130). Validity is also about how well the research can be understood by other people (Kihlström 2007b, p. 231). For example, if there is a lack of connection between different parts in the researched material, the validity can be considered low.

For this study, validity has been considered in a number of ways. Larsen (2018, p. 130) states that qualitative studies with interviews are a way of increasing validity since it is possible to make corrections of difficulties or new aspects during the process. For this study, interviews and observations were conducted. A pilot study was conducted for both the interviews and the observations. Kihlström (2007b, p. 231) explains that a pilot study to test the interview guide and give practice to the researcher increases the validity. Furthermore, both the interview guide and the observation guide were reviewed by a supervisor. In addition, Kihlström (2007b, p. 231) suggests method triangulation for higher validity. As mentioned, this has been used in this study.

Reliability is about how reliable and believable a study is, as well as how carefully and accurately it has been conducted (Larsen 2018, p. 131; Khilström 2007b, p. 231). Larsen (2018, p. 131) and Kvale (2015, pp. 115-116) explain the difficulties of maintaining high levels of reliability in qualitative research. This is due to the impact the researcher, the environment and the state of the informants might have on the answers given to questions in interviews. Additionally, in observations the researchers’ interpretation can differ due to personal aspects. All factors mentioned are difficult to eliminate. Therefore, it is of high value to the researcher to carefully account for all steps taken in the research process (Kvale 2015, pp. 115-116).

Another way to increase the reliability is to conduct interviews and observations together with another researcher. By doing so, two persons’ interpretations can be compared (Kihlström 2007b, p. 232; Larsen 2018, p. 132). However, this was not possible in this study. Instead, the interviews were recorded with audio-recording, at the informants’ consent. According to Kihlström (2007b, p. 232), this increases the reliability since the researcher can listen to the

interviews several times and make new interpretations. Further, the reliability is also higher if the transcripts and the analysis of the interviews are carefully conducted (Larsen, p. 132).

4.2.

Ethical considerations

Every researcher needs to consider ethical aspects of their study. The Swedish Research Council (2017) has written a document with guidelines that should be maintained by researchers in Sweden. Below, relevant guidelines for this study and how they have been considered will be accounted for.

According to the Swedish Research Council (2017, pp. 26-27), participants in a study have the right to be informed about the purpose of the study. They should also be given the proper opportunity to consent to participating in a study. Before the interviews and observations in this study, the informants were informed in writing about the purpose of the study and could voluntarily consent to participate. The consents were collected in writing through a letter of consent. The informants were also informed that they can choose to withdraw their consent at any point. In addition, the principal of the school where the interviews and observations were held was informed and asked to consent.

Further, the Swedish Research Council (2017, pp. 26-27; 41) emphasizes that the researcher is responsible for assuring anonymity for the informant. In this study, no names or other personal information except gender, years of teaching and approximate age is shared nor gathered in writing or recording. To be able to connect the right interview to the right observation, coding is used. For example, the teachers are referred to as teacher 1, teacher 2 and so on. Further, the interviews were recorded, and consent was collected from the informants regarding this. The recordings are stored in a device that is protected by a password only known to the researcher until the thesis is finished and assessed. As explained by the Swedish Research Council (2017, p. 42), there are rules as to how data-material should be stored.

4.3.

Participants

The aim for this study was to have three to four informants participating in both an observation and an interview. The selection of participants was limited to teachers in years 4-6 who teach EFL and an inquiry was sent to the principals at seven schools in one municipality in Sweden. After a few days and no replies, a reminder was sent, and three principals agreed to forward the

e-mail to their teachers. However, no replies were received from teachers. Unsuccessful attempts to personally and via connections contact teachers were also made. Due to lack of responses, teachers at a school where the author of this paper has personal connections were approached, and two agreed to participate in the study for both observation and interview. Additionally, two more teachers from the same school were available for an interview but not for an observation. Hence, the selection of participants for this study was one of convenience (Larsen 2018, p. 125). The choice of convenience can be mirrored in the lack of spread in gender and age of the participants. All four teachers are female, 40-55 years old and have a teacher’s degree. However, two of them do not have a degree in teaching EFL but have taught the subject.

Table 1 Participants

Pseydonym Age Teacher’s degree EFL degree Number of years teaching Number of years teaching EFL Currently teaching EFL

Teacher 1 40-55 Yes Yes 26 20 Yes

Teacher 2 40-55 Yes No 5 2 No

Teacher 3 40-55 Yes Yes 20 10 Yes

Teacher 4 40-55 Yes No 30 “a few years” No

4.4.

Implementation

This section will account for how the observations and interviews were implemented. 4.4.1. Pilot study

A pilot study was conducted with a teacher working in grade 6 to test the interview guide and observation guide and give practice to the researcher. The informant in the pilot study has similar characteristics as the informants in the main study; female, 40-55 years old, has a teacher’s degree and teaches EFL. Both the observation and the interview were held at the teachers place of work and done in a manner like the upcoming study. During the observation it was discovered that the observation guide was not satisfactory, and after the pilot study it was revised to be more precise. The interview questions were found to work well, and only minor changes were therefore made to the interview guide to make it easier to understand and follow. 4.4.2. Main study

Before collecting the data for this study, he four informants were given information both in person and via a letter of informed consent. They were all given a couple of days to read the information and decide if they wanted to participate. Before the observations and interviews the teachers gave their consent.

The two observations took place where the teachers usually work. They were held before the interviews with the observed teachers to have the possibility to ask questions about what was observed. During the 40-50 minutes long observations, the author sat in the back of the classroom and tried not to disturb the lesson or interact with the teachers or the pupils. This means that the researcher observed with the intention of not contributing to or disturbing the events that were observed (Larsen 2018, p. 148). However, at one time at each observation, the observed teacher asked the observer to translate a word, to which the observer answered. In addition, there is always a risk that the people being observed will act differently because they are being observed (Stukát 2011, p. 57). This needs to be taken in consideration when the results are later analyzed. Further, an observation guide was used to ensure that relevant observations were made, and a computer was used to take notes throughout the observations when something relevant to the study occurred. It is also worth mentioning that pupils were present during the observations but only the teachers’ actions and general events of the lessons were noted.

All interviews were held at the teachers’ place of work. Three in empty classrooms and one in another available room. The interviews were conducted in Swedish since it is the mother tongue of both the interviewer and the interviewees. The interviews lasted for about 20 minutes. During the interviews, audio recording was used. This gave the interviewer opportunity to focus on the conversation instead of taking notes. As mentioned, an interview guide was used during the interviews to ensure that relevant questions were asked. The same interview guide (see Appendix B) was used in all interviews. However, due to the amount of information the different teachers spontaneously shared, the questions were not always asked in the same order. There were also different follow up questions asked to each teacher depending on the information they shared. The follow up questions are not noted in the attached interview guide (appendix B). At the end of every interview, the interview guide was looked over to ensure that no questions had been left out, and the interviewees were asked if they wanted to add anything else. Despite this, question number 5 “Vad betyder begreppet läsförståelse för dig? / What does the word reading comprehension mean to you”? was forgotten in the interview with teacher 1.

4.5.

Method of analysis

The method of analysis was similar to how Larsen (2018, pp. 160-163) describes content analysis. The first step in the process of analysis was to listen to the interviews a couple of times. Further, in order to analyze the collected data, the interviews had to be transcribed. According to Larsen (2018, p. 156), the transcriptions need to be as precise as possible to give the study high validity. However, it is also mentioned that this is a time-consuming process. Due to time constraints, the interviews were not transcribed in full. Small comments from the interviewer such as “Mm” or “Aha” were not included in the transcriptions Additionally, in two interviews, the interviewer and the interviewee discussed matters that were off topic to the study, and those parts were also excluded from the transcriptions. Due to ethical aspects, names or other identifying aspects mentioned, as well as information about specific pupils in the interviews were excluded or rephrased. Furthermore, a choice was made to not include pauses, intonations or laughs in the transcriptions. According to Kvale and Brinkman (2014, pp. 221-222) this is a choice the researcher can make based on how the interviews will be used. In this case, the language itself is not the object of research, but the content of what was said is. During the transcribing, patterns started to appear. The patterns were similar methods used between the teachers, opinions they shared or disagreed on or words that were frequently used by the teachers throughout the interviews. The patterns could also be connected to the research questions, the interview guide or the previous research. Therefore, keywords were noted on a notepad in order to be remembered and used when analyzing the transcriptions.

After transcribing the interviews and printing the transcriptions, the transcriptions were read in whole a couple of times. Further, color coding with regular felt-tip pens was done. The keywords that had been written down during the transcribing were used as categories that each had a different color. In this part of the process, the transcriptions were overview read eight times, one time for each category, to search for the patterns. The keywords were: pre-understanding/previous knowledge, images/pictures, Swedish/other subjects, working together, talking, asking questions, translating/look up and summarizing. Finally, quotes matching each research question with associated categories, were cut out and put on a whiteboard to have an overview of the results. After having read through the background and previous research, the transcriptions were read through again with the aim of finding connections to the background and previous research. These findings were noted in a digital copy of the background and previous research section in Word.

The notes from the observations were not as time-consuming to analyze. They were read through a few times with the keywords from the transcribing in mind, while notes with interpretations were taken. Further, they were compared to the interviews with the same teacher and to each other.

5.

Results

In this section, the results of the empirical study will be presented. As stated previously, the aim for this paper is to learn about practices and perspectives elementary teachers in Sweden have regarding working with reading comprehension in English as a Foreign Language. The results of both interviews and observations will be presented together under different themes. First, findings relevant to research question one “How do teachers in years 4-6 in one elementary school in Sweden work with reading comprehension within the EFL classroom?” will be presented. Second, findings relevant to research questions two “How do these teachers perceive working with reading comprehension strategies within the EFL classroom?” will be presented. Since the interviews were conducted in Swedish but the paper is in English, the quotes from the informants needed to be translated.

5.1.

Working with reading comprehension

The teachers talked about several different methods and approaches to work with reading comprehension in EFL. These are presented under the following sub-headings.

5.1.1. “Like in Swedish”

All four informants were in cohesion about referring to Swedish or other subjects when talking about how they work with reading comprehension – either briefly or with longer explanations. Teacher 3 stated that she talks more about reading comprehension strategies when she teaches Swedish. Similarly, teacher 1 explained how the pupils in EFL have started to use a strategy she has taught them in Science class. In addition, teacher 4 who does not have degree in EFL, referred to her teaching methods in the Swedish subject a number of times and explained how she uses the same methods when teaching EFL- such as looking at pictures and headings, pre-knowledge, and summarizing. Lastly, teacher 2 mentioned how teaching reading comprehension strategies is important in the Swedish subject and exemplified by mentioning

that she teaches her pupils to highlight important words and that she has done the same when teaching EFL.

5.1.2. Reading the text

Three of the informants pointed to the benefits of looking at pictures as a way to start approaching a new text:

Table 2 Approaching a new text

Teacher 1 Teacher 3 Teacher 4

” We look at pictures, the

headings… things to achieve a pre-understanding.”

“The textbooks are also built up with image support.”

“I talk about ways to approach a text, maybe you start with a picture.”

“A lot builds on creating a pre-understanding of the text, we talk a lot, often about a picture.”

“You talk about the text, look at pictures and the headings…”

In addition, teacher 2 and 3 mentioned watching movies to achieve pre-knowledge or to have more of a context before reading a text.

Two of the informants held a similar approach to reading in EFL-classes. Teacher 1 and 4 both described how they typically start by reading the text aloud with the whole class or listening to a recording. This is then followed by reading aloud in pairs, the whole class aloud together, or one person at a time aloud for the whole class. Finally, the pupils quietly read on their own or to the teacher. After reading the text and gaining some understanding, the pupils would typically start working with questions or with exercises in a workbook. Teacher 1 also said that she and her pupils try to predict what the text will be about after having looked at pictures and headings. Both teacher 1 and 4 emphasized the importance of talking a lot about the text before having the pupils working on their own as well as looking at the structure of the text. The observation of teacher 1 confirmed her description on how she works when starting to work with a new text. During the lesson the class first looked at the pictures and discussed them and the title. The teachers also asked questions, for example: “What do you think will happen? Something good or something bad?” After that they listened to a recording of the text while looking in the textbooks. Next, the teacher asked questions about the text before letting the pupils read to each other in pairs. For example: “Why did she break her hand?”. Finally, the text was read aloud in class by the pupils, one sentence at a time per pupil. In the interview, the teacher further explained that she always works a lot with the text orally in the group before letting the pupils

work more on their own in writing. In a similar way, teacher 2 also described that she used to read each text aloud several times when she taught English. She described she would explain every sentence after reading it. Further, the pupils then read the text quietly to themselves. Teacher 3 on the other hand, described a somewhat different approach to reading the text. She explained that the type of reading depends on what type of text the class is working with. During the observation with the teacher, the class listened to a recording of a text about The United States almost immediately after having said good morning and talked about the schedule of the day. Hence, there was no warm up exercise. After that, the pupils were asked to collect their textbooks and read the words in the wordlist aloud to each other. They also listened to the text again while looking in their textbook. There was no other reading of the text during the lesson. When asked about this during the interview, the teacher explained that she did not find the text appropriate for the pupils to read aloud in class, but that they had done it previous week with a text with more dialogue. She also mentioned that they during the previous lesson had watched a short movie that had connection to the text. In addition, she said that they often work a lot with the words from the text and that the meaning of words is a way to start approaching the text. During the lesson, they worked with the words as a post-reading activity as opposed to a pre-reading activity. The three other teachers also mentioned working with words but stated that they believe that understanding the whole or bigger picture is more important than focusing on single words or details.

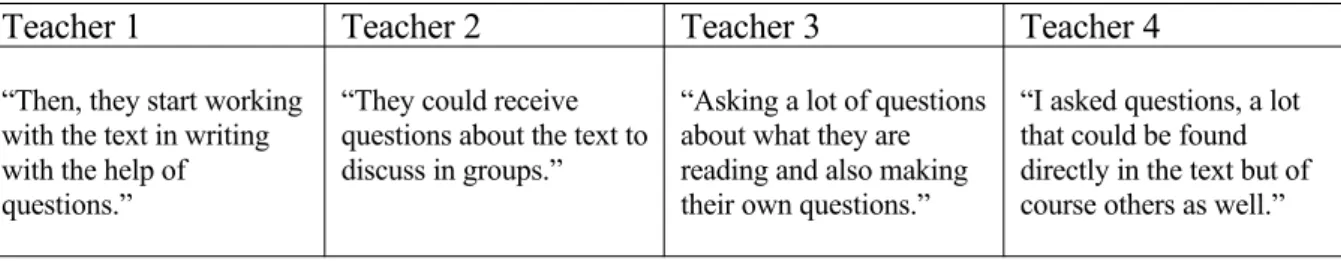

5.1.3. Asking questions

All four teachers mentioned that they work with questions about texts, either before, during or after reading.

Table 3 Working with questions

Teacher 1 Teacher 2 Teacher 3 Teacher 4

“Then, they start working with the text in writing with the help of questions.”

“They could receive questions about the text to discuss in groups.”

“Asking a lot of questions about what they are reading and also making their own questions.”

“I asked questions, a lot that could be found directly in the text but of course others as well.”

As found in the interviews, asking questions could both be part of achieving pre-knowledge before reading, developing more comprehension during reading or as a way of processing the text after reading. This was also found in the observation with teacher 1 where she asked the pupils questions about the title and the pictures before starting to read the text, as well as asking

questions and thinking aloud after reading the text. Moreover, both teacher 2 and 3 described the use of cooperative learning when working with questions after reading a text.

Teacher 3 explained how she let the pupils create their own questions as opposed to just answering pre-made questions. She suggested this as a way to “lure” the pupils into the text. The other teachers did not mention a similar way of work, instead they mentioned that the pupils were given pre-made questions to work with or discuss.

5.1.4. Summarizing and translating

All four teachers said that they work with summarizing when teaching EFL. Teacher 1 had a number of examples that depended on the proficiency of the class. When teaching year 4, she explained that she has worked with organizing pictures as a form of summarizing a text. With more proficient pupils she had the pupils writing summaries with the help of keywords as a form of homework quiz, instead of using wordlist and translating those. Teacher 4 said that she sometimes worked in a similar manner. When they had homework quizzes, she would ask the pupils to orally summarize the text of the week. A third example given from teacher 1 was from the workbook she is currently using where an exercise was to connect the start and endings of sentences with each other. She then asked her pupils to make a summary with the help of the sentences. The last example she gave was having the pupils orally summarize a text from a previous lesson, as a way to start the new lesson and remember what they worked with last time. Likewise, teacher 3 explained that she works in a similar way; “I always strive at summarizing, it is really important. And then reconnect in the upcoming lesson”.

In the observations, two different ways of summarizing were found. While teacher 3 used an exercise from the workbook as a way to finish the lesson where the pupils named one thing from the chapter they had read, teacher 1 used summarizing more continuously throughout the lesson. For example, she summarized the pupils’ predictions about the text before starting to read.

Teacher 2 described that when she taught EFL, she used to summarize in Swedish because her pupils at the time understood little English. The pupils would help her, and they would summarize together. According to her, it was a way of making the pupils understand the context of what was read. Moreover, she explained how she had to translate every sentence of every text to Swedish to make the pupils understand. Translation and explaining in Swedish was also brought up by teacher 1; “After having listened to the text, they translate the text in pairs” and

“When we read the text, I have to explain in Swedish. But some of them does not understand my Swedish either. It is very complex”. In addition, both teacher 1 and 3 emphasized the skill for pupils of being able to look up words in lexicons by themselves.

5.2.

Teachers’ persepectives

As described above, all four teachers mentioned ways they work or have worked with reading comprehension and reading comprehension strategies in EFL. This can give some indication about their perspectives on the matter. However, their perspectives and opinions will be presented in more detail below.

5.2.1. In EFL or in other subjects

When directly asked about their opinions about teaching reading comprehension strategies, teacher 1 and teacher 2 stated that they believe it is of high importance to do so when the pupils are poor readers or lack linguistical skills. Teacher 1 elaborated by explaining that the school where she works has many pupils with weak language skills and that if she does not teach reading comprehension strategies, the reading will be overwhelming for the pupils to take on by themselves. This was also emphasized by teacher 4 who pointed to the fact that the school has many pupils that are poor readers and have a weak linguistical background. She further explained by referring to the Swedish subject where she stated that working with reading comprehension strategies is very important. Therefore, she said she believes it is important in EFL as well and that not talking about the texts would have negative consequences for the pupils. Like teacher 4, teacher 1 also referred to a different subject. In her case, she explained that she must also work a lot with reading comprehension strategies when she teaches Science. Teacher 3 did not give an answer as straight forward as the rest of the informants. She did say that she believed that reading comprehension is something that needs to be worked with in the classroom but explained that she mostly talks explicitly about reading comprehension strategies in her Swedish lessons. However, she also mentioned that reading comprehension strategies are part of learning English as well and gave examples on how she incorporates it in her teaching as presented under previous heading.