(Un)Exceptional Measures Against a Housing Crisis

A Study of Temporary Housing in Sweden

Author: Dragan Kusevski

Master Thesis

Urban Studies Master’s Programme

Department of Urban Studies, Malmö University

Abstract

The lack of affordable housing has been a long-standing problem for many cities in Sweden, and the recent refugee crisis has only highlighted the difficulties for economically weaker constituencies to enter and sustain in the existing housing market. The pressing situation and a new law, obligating the municipalities to supply housing, forced the authorities to look for solutions. The thesis investigates the recent changes and use of one of these offered solutions – temporary housing permits. Using a qualitative approach, it tries to capture both the formative-discursive processes and the material outcomes of this measure, in order to understand what informs the decision and its possible implications. The study employs theoretical concepts from Giorgio Agamben’s theory on the ‘state of exception’, as I consider them important for the understanding of the processes. The interventions in the housing system are made possible only by declaring that the shortage of housing is in an ‘exceptional situation’, one that can only be resolved with irregular practices, exceptions from standard norm and regular procedures. A look into the legal-formative mechanisms and the materialization of the temporary housing permits is given. The thesis argues that a wider perspective is needed and tries to bring into the discussion the political and social aspects of using a measure like this one. Although conceptualized as a quick and temporary remedy, it is maintained that the utilization of temporary housing permits can potentially have harmful long-lasting effects on the understanding of housing provision, living standards, and planning processes. This suggests that authorities have to be careful when using exceptional measures and calls for a fundamental and systemic re-thinking of housing in general.

Contents

1.0 Introduction ... 2

1.1 General aim and research questions ... 3

1.2 Thesis structure ... 4

2.0 Research design and methodology ... 5

2.1 Case studies and qualitative approach ... 5

2.2 Methods of data collection and analysis ... 7

2.3 Limitations, constraints, and reflexivity ... 9

3.0 Conceptual perspectives... 10 3.1 Conceptualization of housing ... 10 ... 12 Homo Sacer ... 12 State of Exception ... 13 ... 14

4.0 Building the context ... 16

4.1 The housing context in Sweden ... 16

... 16

Deregulating the housing ... 17

The universalistic character of the housing policy ... 18

... 19

Segregation problems ... 20

4.3 The temporary building permits in the PBL ... 20

4.4 Summarizing the context ... 22

5.0 Analysis ... 22

5.1 Formative and legitimizing mechanisms ... 23

Discourses of disaster ... 23

Calls for greater efficiency ... 24

Changes needed here and now ... 25

Legitimacy through temporariness ... 26

5.2 Materialization of the temporary housing permits ... 28

5.2.1 Housing for asylum-receivers ... 29

5.2.2 Student and youth housing ... 33

5.2.3 Temporary housing permits as a city-development tool ... 36

Summarizing the evidence of the materialization of temporary housing ... 37

6.0 Discussion and conclusions ... 38

List of references ... 42 Appendices

1.0 Introduction

The recent influx of refugees from war-torn countries in Sweden, which peaked in 2015, accentuated the increasing shortage of affordable housing in the country. Already a long-standing problem for many cities, the new arrivals only highlighted the difficulties for economically weaker constituencies to enter and sustain in the existing housing market. After the first groups arrived, stricter border controls and other measures have considerably reduced the number of arrivals. Despite the reduced numbers, faced with a problematic housing situation of settled asylum-recipients, which often includes conforming to overcrowded apartments and/or illegal contracts (Boverket, 2015b, p.8), and expecting more people to come in the following years, the Swedish government decided to introduce measures that would assure a balanced distribution of newly-arrived people through the municipalities and deliver means for the local governments to deal with the matter of providing housing for this group. A new law (SFS, 2016:38) was introduced in 2016, that now obligates the municipalities to accept a certain number of refugees (with already obtained residence permit) that the Migration Office (Migrationsverket in Swedish) assigns to them, with no possibility for an appeal, contrary to the previous voluntary refugee-acceptance. The law, introduced with the intention of instigating more even distribution of asylum-recipients, takes into consideration several different parameters, such as labor market conditions, population size, previous acceptance of newly arrived residents, etc. when deciding how many people each municipality would have to accommodate.

In some municipalities, difficulties in obtaining housing for the newly-arrived people have been reported even before the new law (Boverket, 2015b), and many of them expressed doubt that they will be able to meet the quota set by the Migration Agency. In a 2016 survey, done by the Swedish national television (SVT) where the top 50 municipalities by number of assigned asylum-recipients were contacted, only 14 (out of 46 responses) were confident that they will completely meet the requirement for that year, and even less (4) were optimistic about 2017 (Marmorstein and Larsson-Kakuli, 2016). As a result of the growing concerns, the state authorities started to look for different solutions that would be available to the municipalities, so they can better handle the housing situation on their territory.

Therefore, in 2017, the government passed a change in the Planning and Building Law (henceforth: PBL) which facilitates quicker and easier issuing of temporary building permits meant for housing (Sveriges Riksdag, 2017a). The measure was directly aimed to tackle the housing shortage in the short-term, stating that in many of the municipalities of the country, the need for housing today is so large that it cannot be met in a timely manner by ordinary planning and construction processes 1). Building housing on temporary permits has been a practice before, although the law very clear since it contained a requirement for

need

always considered to comply with it. The new amendment introduces a section that deals with temporary permits specifically

are met for a permanent one, as long as it is ensured that the land would be restored to the original state after the expiration of the permit. The maximum possible length of the permit is 15 years (10 + 5 years possible extension) and these permits can be issued until May 2023, when the measure ceases to exist. It is expected that this change will increase the use of temporary permits for housing construction and encourage utilization of unused land.

Ways to stimulate the production of new homes in Sweden have been discussed and tried prior to this change, some of them using similar approaches - looking for means to lower construction costs and processing time through modifying design standards and other requirements and simplifying the process in general. A notable example are the recent changes in requirements for student housing (Boverket, 2013; 2014). The arrival of large groups of people has put additional pressure on the housing provision, so the perceived urgency was a reason to look for other solutions as well. One of the proposals that the National Housing Office (henceforth: NHO, Boverket in Swedish) suggested was a departure from general housing solutions and an initiation of a new housing-construction model that would target specific groups (with low income) and not all households (Boverket, 2015b). Changes in the PBL so that housing construction could be regulated differently during emergency times, were also suggested (Boverket, 2015a). We may see all of these developments as forerunners of the amended law for temporary permits, I argue, since they are part of the same spectrum of solutions to the housing crisis. As such, both the temporary housing permits and the preceding processes will be the object of analysis of this thesis.

1.1 General aim and research questions

The pressing need for affordable housing undoubtedly creates tension in the Swedish society, especially in the bigger cities, for which temporary exemptions and deregulatory measures seem to offer a quick remedy and buying some time. However, it is not clear what these interventions would mean for the housing system in the long-term. It is important to bring to light the potential effects this could have on living standards and housing rights and explore the consequences for different groups and classes, especially those most directly affected by it

the potential dwellers.

Therefore, this thesis argues that a wider perspective is needed, and tries to bring into the discussion the political and social aspects of using a measure like this one. Although conceptualized as a quick and temporary remedy, it is maintained that the utilization of temporary housing permits can potentially have long-lasting effects on the understanding of housing provision, living standards, and planning processes.

The interventions in the housing system, are made possible only by declaring that the shortage of housing is in an situation , one that can only be resolved with irregular practices, exceptions from standard norm and regular procedures. For that reason,

that allows these practices to occur. To explore the rationale of the measure along with the possible outcomes and implications then, both the argumentation and legitimization in

documents that introduce the measures will be analyzed, as well as the actual materialization of spaces that arise from them.

The acute shortage of affordable housing is not a solely Swedish phenomenon, on the contrary many countries struggle with this issue, especially the cities that offer attractive study or job opportunities. In many places a turn to solutions like temporary housing and lowering living

standards has been noted recently. These include con -

and Tokyo challenging the size norms and living standards through innovative and serialized design (Post, 2014; Keegan, 2018); movable modular homes in Austin and Sydney (Sebag-Montefiore, 2017; Kimble, 2018); floating student-housing containers in Copenhagen (Mun-Delsalle, 2017), etc. The widespread use of similar answers to a housing crisis makes the quest to explore the possible effects they could have even more important and timely.

Research questions:

What informs the decision for the new changes in PBL regarding temporary housing permits?

How are the permits utilized in practice? By whom and to what end?

What possible implications can the changes have regarding the housing crisis, housing provision, planning processes, and living standards?

1.2 Thesis structure

The thesis is structured in six chapters. In the second chapter the research design and methodological tools used in the study are presented and discussed. The primary and secondary data are also presented, as well as the limitations and constraints related to the used method and the collection of data.

Chapter three consists of a presentation of the theoretical concepts that will serve as analytical lens through which the temporary housing permits and the related processes will be observed. Here, theorization on the political and social aspects of housing is introduced, as well as the

elated research.

The fourth chapter includes an outline of the Swedish context, particularly the housing and refugee crisis, as well as an overview of the regulation of the temporary permits in the Swedish law through the years.

Chapter five consists the presentation and analysis of the results, divided in two sub-chapters: formative and legitimizing mechanisms of the measure and the analysis of the material outcomes of the temporary housing permits.

Finally, chapter six offers a comprehensive synthesis of the different strands of analysis, discussion and concluding remarks including future research suggestions.

2.0 Research design and methodology

When I was first familiarized with the introduction of temporary housing as a remedy for the Swedish housing I knew very little about the topic or the context, but I was curious to find out what informs this decision, how would it play out, and what would it mean for the prospects of affordable housing. As the initial curiosity started to develop into a study, the matter of how to approach the questions it tries to answer became important. Following the logic that the p.226), the choices of methodology and design of the research were made hoping that they would best facilitate answering the research questions and allow insightful understanding of the matter. In the rest of the chapter these choices are explained and discussed.

2.1 Case studies and qualitative approach

A design of a research is a strategy, a logical outline that the researcher must adopt and/or create, so that the matter under study is approached in the best possible way. De Vaus (2001) of a research design is to ensure that the evidence obtained enables us . The experience from social science research can offer several designs that are often used, such as: longitudinal study, cross-sectional study, experimental study, case study, etc. Although it could prove helpful to have a

My aforementioned unfamiliarity with the subject somehow determined that this work would be more investigative and exploratory in nature. Additionally, the actualization of temporary housing in Sweden and the related changes in laws and regulations took place fairly recently (introduced in 2017), so it was of no surprise to realize that the matter is still not researched thoroughly (if at all). Because of this, I decided that a case-study design and a qualitative approach offer the best way to investigate the matter.

I find

case-a problem in one or more recase-al-

real-contextual information about a case (Yin, 2009). I find this important because of the lack of previous research and available data, and the nature of the questions this research tries to answer.

According to Yin (2009), there are three distinguishable types of case studies: exploratory, descriptive, and explanatory (p.4). The exploratory type is recommended when there is a little information available as it is the case with this research, so the study can be considered exploratory since it tries to explore the formative mechanisms and outcomes of a legal/political measure, but it also tries to answer why questions why the measure is employed, to what end

thus implying an explanatory character as well. Contrary to the common misunderstanding, the

case-methodology by default (Yin, 2009). However, a qualitative approach is adopted here because

I argue, in order to get a nuanced understanding of the decisions, argumentations and perspectives behind the employment of temporary housing, and not be constrained by the lack of available data and information.

According to Stake (2003) a case study can be intrinsic, instrumental, or collective. Intrinsic

case study is a study where e particular case

through the case. A n is study can be considered both intrinsic and instrumental. The primary interest are the temporary housing permits, which makes them the case of this study, but the thesis also tries to draw conclusions and explanations beyond the case itself, about social and political aspects of housing, city planning and city life.

It becomes obvious that it is important, in qualitative case-studies especially, to carefully select

the cases to study. ing

but most importantly opportunities to learn (p.152). Although the case study in this thesis was decided from the start, as the primary interest was the case itself (which usually happens with intrinsic case studies (Stake, 2003)), still certain choices had to be made. The thesis is designed as a single case study (temporary housing) which contains several

so-With that in mind, the units (multiple temporary housing projects) were selected from four different cities in Sweden (Stockholm, Gothenburg, Malm , and Lund) each of them in the top ten municipalities by received asylum-recipients in 2017, for which the temporary housing was meant initially. Contributing factor was also that these cities offer the most information about the projects, through official documents and websites. After the early detection of three types of use of the temporary housing permits in practice (housing for asylum-recipients, student housing, and as a city-development tool), it was important that samples from each of them is included.

The data was also obtained at more than one level: broader, national level (from the National Housing Office, documents from state institutions) and narrower, local level (from employees in municipalities and non-profit associations), in order to reflect the relationship between the legal-formative mechanisms and the outcomes of the measure and to potentially present different perspectives.

The collection of the data was mainly done through interviews and document analysis, while sources like media reports, official statistics, and websites were occasionally used to enrich the discussion. Literature review was also done in order to get more familiar with the Swedish housing context (most of it is presented in Chapter 4).

2.2 Methods of data collection and analysis Document analysis

Collecting information from documents seemed to be a logical starting point to get into the subject, as it offered several advantages. First, since the research deals with a legal measure and a topic that has been debated on an institutional level, it was clear that documented traces such as discussions, reports, legal outcomes were available. Most of the material was well documented and easy to access through institutional websites. The documents also offer the opportunity to get back to them for re-reading and re-analyzing multiple times during the research and allow to get insight into events and discussions that occurred through different periods of time. This was important for the research because it allowed me to get familiar with the context in which the case takes place, and more importantly to investigate particular debates and processes that have led to changes in laws and regulations. As most of the material are official documents, such as law propositions, official reports, official statements, etc., they they were essential to the study which tries to illuminate the relationship between the official discourse and its material outcomes and the possible effects from it.

It can help to reveal how policy is made and whose ends it serves

Consequently, when analyzing the documents, attention was paid to the problem formulation, narratives, explanations, and argumentation for the offered solutions.

In the abundance of official documents and reports, it is important to carefully sample and decide what to include and what to exclude from further analysis (Yin, 2011, p.148). The chosen documents were selected on the basis on the amount and quality of information they provided about the decision-making process and reasoning about temporary housing and related regulations. In the following section, a short presentation of documents is made:

A need for changes in the PBL in response to the refugee crisis

This is a short letter from the National Housing Office to the Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation ( in Swedish) from 2015, in which changes in PBL are required. The letter was interesting for this research because of the way it formulates the problem of refugee influx and the nature of the required changes to regulate rules differently in times of crisis.

Time-limited building permits for housing Proposal 2016/17: 137

This document is the proposal for the law changes for the temporary housing permits, and as such presents important source of information due to its direct relevance to the case. It is valuable to the research because it includes the explanation and reasoning behind the decision, as well as voices of doubt and argumentation from different parties.

Time-limited building permit for housing - 2016/17: CU21

The document presents the report from the discussion of the Civil Affairs Committee on the Governmental proposal for the law changes. It includes motions and debates between different

members of the committee, which provides insight in the rationale and arguments both in favor and against the changes.

Proposals for regulatory changes for more housing for young people and students This is a report from the National Housing office from 2013 in which changes in regulations and design requirements for student housing are suggested, in order to enable more efficient construction of student housing. It is not directly connected to the case, but it is analyzed as it suggests similar means for facilitating construction of housing as the temporary housing changes.

Aside from these documents, other reports were read and analyzed, mainly to provide Calculation of the need for new housing by 2025

ousing situation for the new arrivals Settlement Act in

practice. A study of the responsibility of the municipalities and the role 2018), etc.

Interviews

Although the document analysis offered valuable source of data collection, it has its limitations order to get more insightful information, it was necessary to turn to other sources as well, such as interviews. Interviews are probably one of the most used methods in qualitative research, as it allows targeted inquiry and valuable insight hard to find in official documents. Therefore, . The use of interviews was crucial for the study

-reports was lacking and observation was impossible.

Yin (2011) recognizes two types of interviews: structured and qualitative, and points that the overwhelmingly dominant mode of interviewing in qualitative research . In this study so-called semi-structured interviews were used, as this type implies more open-ended questions, and allows conversational mode (ibid.) where the interview can be steered to The sel

relevant source. The interviewees were still selected purposefully, depending on their role and expected knowledge. All of the respondents were asked questions about the ongoing temporary housing projects, the recent change of laws, and particularly their perspectives and reasoning about the subject. Themes and information that emerges from the document analysis were also brought up.

Seven interviews were conducted in total, lasting between forty minutes and an hour (see Appendix 2). Four of the interviews were done in person, in offices of the interviewees; two of the interviews were done by telephone, and one was done as a written correspondence, where questions were sent in advance, and answers were received several days later. All of the interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed by the author. Although telephone interviews have disadvantages to face-to-face conversation, they can also be useful as they

offer possibilities to interview persons that otherwise would be physically impossible to reach ( , 2012). The written correspondence was on demand of the interviewee, and although it offered limited insights, it was the only way to get answers.

Other means

Besides document analysis and interviews, other means of collecting data was used. Official statistics about the distribution of the temporary housing permits and asylum-recipients from tistics offered an initial overview of the amount and geographical distribution of the permits.

Media reports were also used sporadically, to enrich the discussion or provide information when no other data was available. Media reports and journalistic texts as a source of information are often used in social research, and although the approach has disadvantages like the often-unclear purpose or method of doing the reports (Bechhofer and Paterson, 2012), they their insights, information and analyses are frequently more penetrating, enlightening and infinitely better written than the more pedestrian

2.3 Limitations, constraints, and reflexivity

Case-study design has been criticized mainly because of its focus on small samples and therefore difficulty to generalize

(2006) points hat knowledge cannot be formally generalized does not mean that it cannot p. 227). A crucial advantage of the case-study is that it offers a close look on processes, but the careful choice of the samples for analysis is important if we want to test or build a theory from it (p.229). In that manner, the choice of the units of analysis was made purposefully to provide both variety and insightful information. However, it has to be noted that the access to data about the use of temporary housing permits by municipalities was somewhat limited, so it also influenced the choice of the units to some extent.

Other common criticism of qualitative methods is that it tends to be too subjective. To overcome this, I tried to include data from multiple sources, present different perspectives, and use quotations of original statements, in order to increase the validity of my interpretations. I am also aware that the sampling of the analyzed documents could prove to be incomplete, as there can always exist other documents, which can prove to be relevant for the case. For that reason, I tried to be thorough in collecting all of the related documents, given the time available. As a limitation must be considered also the fact that most of the documents were in Swedish language, so I had to translate them to English as I am not a fluent speaker of Swedish (although I have some knowledge). This could have potentially caused errors in the analysis and interpretation, although I tried to double-check every translation. The interviews were also conducted in English, and although all of the respondents spoke the language fluently, it might have impeded them to express themselves as they would have in their native tongue.

3.0 Conceptual perspectives

The theoretical lens, through which this research will analyze the modification in the laws and concept, as developed by the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben, and the interpretation of his work by other authors, especially in its use in city-related research. The reasons for this are emergency or crisis and its seemingly repeatable and prolonged nature. This would mean treating the exemptions and relaxations of rules as symptoms of a state of exception and will hopefully help to better understand their nature. The decision for the application of this concept and the conviction of its compatibility to the particular case initially came because of the introduction of a new section in the PBL in which a possible extensive influx of asylum-seekers is treated as an emergency and placed in a section dealing with natural disasters and war situations, enabling emergency measures to take place if necessary. The notions of urgency for handling the housing situation around the country coming from different state levels and agencies, in which the temporary housing measure can be placed, also provided foundation for application of this concept in the analysis. Additionally, since the research deals with planning Therefore, at the beginning, discussions about the social and political aspects of housing will be included in order to clarify the stance and perspective of the thesis.

3.1 Conceptualization of housing

In a large extent this thesis borrows from Marcuse and Madden (2016) when forming the stance the housing system is always the outcome of struggles between dif

The reason for social tension around housing, as they explain, is that it presents a different thing for different groups for some it is a living, social space

).

It is precisely this ability that makes housing an increasingly commodified object in recent times, moving away from the original purpose to provide shelter and security. The exaggerated focus on the economic value of housing has made the living in many cities unaffordable for many and offers little choice for those with less economic power but to accept

p.51).

When the system is set like that, the home often becomes site of alienation and oppression. Not wishes makes many people not feeling at home. Experiencing the home in that sense means

a

People are also becoming subjects to oppression through housing. H

inequalities, and conflicts experienced in the society in general, also translate into the housing

Madden point to the fact that residential oppression reflects patterns of social inequalities, and some groups experience oppression more strongly than others, depending on socio-economic status, race, or gender. However, housing can also be liberating, since it often provides a unifying platform for many resistance efforts, such as rent strikes, anti-eviction actions, etc. In order for decent housing to be affordable and available for everyone, decommodifying is needed so that its main purpose as a living space is brought back as a priority. This means asking who and what housing is for, who controls it, who it empowers, who it oppresses

necessary to think and debate housing in political and social terms, so that embedded systemic malfunctions are brought to light. Technical solutions and improvements, although sometimes solve the problems if the same housing system that produces alienation and oppression is maintained.

discourse often used about housing. The idea of crisis means that inadequacy or unaffordability are a temporary anomaly in an otherwise

well-where housing is commodified, and not mea

moment of the problem and leave a failing system

intact.

It important to defend, discuss and

re-a formre-al right, but it becomes bre-asis for more equre-al re-and just

Lefebvre) the right to belong to and the right to co-produce the urban spaces that are created by city dwellers contributes to developing people and space rather than destroying or exploiting people and space

contemporary states housing as a legal right, and housing as a social right. The former is usually related to a selective housing policy in which housing is allocated to those who cannot obtain housing themselves, and the latter to universal housing policy which functions through

interpret housing as a social right, although maneuvers towards a more selective policy and legalistic rights are noted.

State of exception

the status quo. The concept of state of exception has been studied by the influential political theorist Giorgio Agamben, who argues that it is the mechanism of government that has become paradigmatic for the modern state. He traces the historical development and transformation of the concept, and points to the dangers of adopting it as a norm casting people and whole State

of Exception Homo Sacer. Sovereign Power and Bare Life

and discussed, as well as the use of the concepts in related research. Homo Sacer

In the very beginning of Homo Sacer

Greeks made difference between an animalistic, natural life, without political meaning zoe, which happens outside the polis, the political realm; and the human life inside the polis, the political life bios. (Agamben, 1998, p.1). Agamben frequently refers to zoe

and this concept becomes fundamental in his further exposition. He connects this distinction to a figure in Roman law, that as a punishment has been stripped out of its citizenship and cast outside of the juridical order,

meaning it can be killed with impunity. This life,

but someone has been stripped away by law, so a person is reduced

(ibid, p.103) to a homo sacer. It is an inclusion in law, by exclusion (from the juridical order). Agamben then draws parallels to contemporary society and claims that modern governments f today there is no longer any one clear figure of the sacred man, it is perhaps because we are all virtually homines sacri (p.68). Heavily inspired by Foucault, he builds on the idea of biopolitics and considers it

based on the tury, changing the means of governing the state by putting focus on human body and life, using techniques Agamben sees the same reduction of human -political mechanism that produces bare life the state of exception.

Agamben conceptualizes the space where the exception is enacted, and human rights are taken away as the camp. Although he provides examples of actual existing spaces (camps) through the history where we can see the concept materialized, ultimately he argues that the camp has pa (Agamben, 1998, p.95) and the states evoke abstract permanent camps

State of Exception Agamben concludes in h

the juridical procedures and deployments of power by which human beings could be so shifts his focus to the state of exception. From the start, he points to the difficulty to define the term mainly because of its ambiguous position between law and politics. For Agamben (2005), understood on political and not

juridico-the he state of exception

is not a special kind of law (like the law of war); rather, insofar as it is a suspension of the

cept .

where it was meant to be applied in the case of war or attacks on the strongholds. However, during the next century it become possible to procla

change from a real, or military, state of siege to a fictitious, or political one (p.5). Agamben illustrates through historical examples how the military

(p.13), opening the way for the concept to be used for governing reasons, as pleased.

iustitium

n the iustitium (even in the case where a dictator is in the office) there is no creation of a new magistracy Therefore, the state of exception technique is not just compatible with authoritarian or tyrannical societies (as it was often used in the past), but is instead about the opening of a wholly anomic space for human action in a more general sense (Coleman, 2007, p.189). After all, such practices have been disseminated in contemporary states, including so-called democratic ones (Agamben, 2005, p. 2). Scholars have argued the state of exception to be an inevitable part of democracy, like Rossiter who in time of crisis, a democratic, constitutional government must temporarily be altered to whatever degree is necessary to overcome the peril and restore normal conditions o sacrifice

(Rossiter, 1948, quoted in Agamben, 2005, pp.8-9).

legitimizing tool that prepares the ground for the existing of the state of ,

as an objective given, necessity clearly entails a subjective judgment, and that obviously the only circumstances that are necessary and objective are those that are declared to be so (p.29)

Lastly, Agamben argues that the state of exception is the power hominus

. that changes all the concepts of politics, because once

the state of exception becomes the rule, international rule and domestic rights change (Agamben, 2013, 5:42 min.).

Bringing to the city and its relevance to the study

being increasingly used by geographers and city researchers, partly

p.99) and concludes:

This thesis, finally, throws a sinister light on the models by which social sciences, sociology, urban studies, and architecture today are trying to conceive and organize the public space of (even if it has been transformed and rendered apparently more human) that defined the biopolitics of the great totalitarian states of the twentieth century (p.102)

The interest in the spatial aspects somehow seems inevitable, also because the sovereign rule, which decides for the exception, is tied to a territory a state space (Minca, 2006), for which the laws and regulations have validity, and from which the exception moves objects from, placing them in a zone of indistinction where the exception gains form, meaning and

legitimation city level, where city authorities

both within and beyond the confines of existing legal frameworks

state of exception in the name of necessity, in urban regeneration and development projects. They question the decision-making on necessity however, as it seems that urban poor neighborhoods are the most likely victims of the exception.

-seeker, exactly because s/he is casted

-the mercy of -the juridical context in which he seeks asylum and is exposed to any kind of

-101) For Datta (2016), exceptionality can be seen in the normalized state treatment of squatter homes

The state of exception theory will hopefully help to better illustrate the processes of easement of housing standards and point to their potential implications. We saw that the city can be, and often is the site where the state of exception is declared and operates. Several indicators demonstrate that the temporary housing permits and the related processes employ the state of exception logic: the introduction of special rules and norms for certain groups or spaces the exceptionality; the suspension of norms and standards for housing through which exceptionality is created; the void of potentiality that this leaves in the law it is left to the municipalities to decide how low or high the standards would be; and the notions of common good behind it. Therefore, combined theory of Agamben and Marcuse and Madden would help us bring to light the mechanisms of state of exception and its potentiality when applied to housing provision.

of exception is rather

geometry of exceptional spaces is that it obscures the ways in which the exception operates as concept as spatializing, not spatialized, and emphasizing the processes of transformation and

th focus

iscursive processes of creation, transformation and legitimization of exceptional measures and their outcomes seen as temporal materialization of the exception in space.

and theoretical - leaving

lve form of

interpretative value, Schinkel and van den Berg (2011) suggest adjusting of the concepts, so it certainly be helpful in our case, since suspension of rights is limited to rights to housing and

living standards, and the potentia all rights

4.0 Building the context

Before going into particularities of the recent events connected to the subject of this study, i.e. the temporary housing permits, I believe that it would be important to present at least some of the context in which these processes take shape. In no way should this be considered a complete history of the housing situation in Sweden, since that would be a complex and overly ambitious task for the scope of this research, but hopefully through several crucial points it will illustrate the political and social landscape in which the recent developments are embedded. The diachronic analysis will provide us with not only a better understanding of the present-day situation i.e. where we are today, but also with hints of the processes that have led to it. This attempt will be organized in three sub-chapters: the first one describing the broader history of the housing context in Sweden; the second chapter explaining more recent developments connected to the influx of refugees in the country; and the third chapter gives overview of the temporary permits in the Swedish laws and regulations.

4.1 The housing context in Sweden

fair to say that Sweden is facing the biggest housing shortage in recent years. However, this is not the first time that the country has found itself in a similar position. In the post-war period, mainly due to the booming industries, housing was very much in demand, especially in the larger and industrial cities in Sweden.

a place to live meant waiting in queues for ten years or more (Hall and Viden, 2005, p.303). In

the 1960s, the so-called a large-scale government initiative,

in order to solve the housing issue providing homes for the increasing labor force of the growing industries. According to Hall and Viden (2005), an important factor that sparked this accelerated construction, was also the extremely low housing standard in Sweden, in comparison to other European countries (p. 302). Consequently, the goal was to tackle the shortage and to modernize the stock at the same time. Between 1965 and 1974, with a considerable help from the government in form of subsidies and other means, more than 900 000 units were built, and with that it seemed like the issue was solved once and for all. The decline of many industries in the following decades left many vacancies in the housing stock, so some of the buildings had to be even halted or reduced in size. Suddenly, Sweden was a country with a housing surplus. Despite being criticized for some aspects, an important success -quality residential architecture and urban design (Nylander, 2013, quoted in

2016

and Mollina (ibid.) are to be found in the comprehensive housing policies coupled with housing subsidies, regulation of loan interest rates, and highly regulated

have more control over the type of housing, its geographical distribution and cost of construction.

Deregulating the housing

Since the 1970s, it is argued that the housing system in Sweden starts to take more neoliberal

( ) shape. According to

Grundstr m and Mollina (2016, p.324), 1974 -

terminated, can be considered as the beginning of these (neoliberalizing) processes. The rent control has changed in 1978 towards a more market-based principle. This change meant that between the tenants and the landlords. Although the process is still followed by the state and extremely, this has placed the landlords in a stronger negotiating position. The following period saw a dramatic drop in the construction of new housing (ibid, p.325) partly due to the created surplus, but also because the governmental help dramatically dropped. In the beginning of the 1990s moves in the same direction continued, perhaps because Sweden was heading towards a European Union membership and was willing (or required) to make changes in its regulations and policies (including housing policy) so they will be more in accordance with the EU principles. The conservative government (in office

The social-democratic government that instead continued to cut the subsidies (ibid, p.272). Moreover, in 1991 the Ministry of Housing (bostadsdepartementet in Swedish) was abolished, and the housing-related matters were incorporated in the Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation ( ), with the

difference (quoted in Grundstr m and Mollina,

2016, p.327)

Since the 1990s, an increasingly large number of newly constructed residential areas started to have an exclusive feel, and these apartments were meant and marketed for middle and upper-classes (p.330). Many cities went through a process of re-invention, as a way out of the post-industrial despair, leading to proliferation of flagship and dockland projects (see for example

ckholm). These efforts were often meant to attract more affluent citizens and recover the tax base to the cities which was lost during the decline of the industries. According to Baeten (2012) this strategy

factual situation, since the population increase in most of the cities was happening due to an influx of refugees and economic migrants

job) market and needed affordable dwellings. This discrepancy between the housing stock being built and the actual economic power of a large portion of the population contributed to increased homelessness, overcrowding and accepting lower living standards due to lack of affordable options, especially in the bigger cities

Christophers (2013) argues that to call the Swedish housing system, as it is today,

regulated and, as such, relatively isolated from market forces and configurations

Christopers (2013) argues that as neoliberal we can consider the processes like the marketisation of the tenant-owned housing, the marketisation of the municipal rental housing, Since the 1960s, the tenant-owned housing sector has been increasingly deregulated and marketized (p.889). Similarly, changes from the 1990s in the regulation of the municipal housing companies (henceforth: MHCs), traditionally considered pillars of the Swedish housing welfare, meant that they could sell their stock, and many have sold big portions of it, especially in Stockholm. A later change, from 2011, stipulates that MHCs would have to work

a principle which guaranteed that no tenure-form would be considered favorable, with more leaning policies towards home-ownership (p.894).

Swedish housing completely deregulated or neoliberalized. He highlights three particular features: the rent regulation, the rental queue system, and the regulation of personal letting and sub-letting. Christophers then concludes that the Swedish housing is not completely neoliberalized yet, althou

-of- (p.907), mostly hurts the most vulnerable population, and re-produces socio-economic inequality.

The universalistic character of the housing policy explains the crucial differences between this

, while the selective

a growing tension between a still dominant universal discourse, on the one hand, and outcomes that have developed in a selective direction, on the other .

In 2001, Bengtsson argued that the universalistic principles of the housing policy were still present in the discourse, like the political-discursive embrace of all tenure forms and types of housing, and the availability to all in the MHCs, but the outcomes were getting an increasingly changes in the same direction, like increasing financial demands on regular tenants, while at

4 1 = A housing crisis

-migrants, looking for job opportunities in the well-functioning industries. However, a change in policy introducing stricter regulations, meant that the biggest part now would be consisted of asylum-seekers and refugees. In fact, Sweden has become one of the largest recipients of refugees per capita, internationally (Liden and Nyhlen, 2014, p.2). Fleeing from wars and the political and economic situation in their respective countries, the number of immigrants increased in the 1990s and recently after 2011, when the war in Syria has started. This influx of people, although it lost some of the initial intensity, is still lasting today and rendered the already existing shortage of affordable housing in certain parts of the country, more visible than it has been for a long time.

2015 was the peak year when around 163 000 asylum seekers came to Sweden. The asylum applications were mostly distributed between Sk

uted across in 2015 were from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq, respectively (p.72).

Initially the distribution of asylum-receivers was done on voluntary basis, meaning that each municipality was able to decide independently on the number of people it would accept, based on their own evaluation of the housing, labor-market and other capacities. Complaints about inequal intake of refugees have been present even before, for example in 2004 when the mayor , p.30). In 2015, the dissatisfaction became stronger, resulting in a statement by the prime-minister Stefan L vren saying that all municipalities should receive asylum seekers and nobody should dodge responsibility Braw, 2015).

Consequently, in 2016, the government issued a new law (SFS, 2016: 38) according to which each municipality now must accommodate certain number of asylum-receivers, assigned by the Migration Office. This created tension in the housing market in many places throughout the country, with many of them already reporting a housing shortage even before this responsibility. The National Housing Office produced a repo

Situation of Newly- ) in which it noted that t

an urgent need for new and affordable housing, arguing that the shortage in some of the municipalities is a cause for lot of the newly-arrived migrants to acquire illegal accommodation and to live in overcrowded apartments, thus facing social and health problems. The report also suggested an array of actions in order to tackle the problem. These include: enabling more intensified construction, especially in places with good labor opportunities; limiting the option for moving to places with already tough housing situation; review and improvement of the queue-system in the MHCs; building houses for specific social groups (those with the lowest

income); and a call for broad collaboration between departments and researchers (Boverket, 2015b). In another report, an estimation has been made that around 600 000 new housing units will be needed in the next nine years, 320 000 of which are needed as early as 2020 (Boverket, 2017)

Segregation problems

It is important to also mention that since the 1970s Sweden has been dealing with residential segregation (Andersson et al., 2010, p.237), reflected predominantly along socio-economic lines (rich-poor; working-middle-upper class). However, since the 1980s and onwards it began to appropriate an ethnic dimension as well (Musterd and Andersson, 2005, p.787), with more and more immigrants concentrating in certain areas, usually in the larger cities (and usually inhabiting the rental housing stock). Therefore, strategies for tackling segregation have been present on the policy agenda as early as the 1970s, including attempts for dispersal and stricter placing-regulation of newly-arrived immigrants which

promised, i.e. breaking segregation and releasing pressure from the big cities (Andersson, et al., 2010, p.249).

4.3 The temporary building permits in the PBL

In the first two official documents that dealt with the planning and building regulation the City Building Statute (Byggnadsstadgan) of 1874 and 1907 - temporary building permits regulated, or for that matter even mentioned. They appear for the first time in the City Building Statute of 1931:

"In the case of construction a building that is intended to last for a limited amount of time, or construction of smaller buildings which are intended to serve the general good, even if it is in contravention of the city plan, the building plan or the area regulations, the building board must grant a permission as long as the company proves to not significantly ruin the soil using it for the intended purpose."

(SFS, 1931:364, p.50)

Temporary permits got an expanded section in the City Building Statute of 1947 where they were regulated in terms of time-limitation and size of the allowed buildings. The section was kept without significant changes in the subsequent 1959 Statute.

st paragraph "In the case of the construction of a temporary building of a simple nature, the building board may, even if the company is in violation of the

Building permits, as stated here, must be granted only for buildings of one story and must intend to leave the building for a maximum of three years from the date of the building permit. However, the county administrative board may, for special reasons, allow th

In 1987, the first Planning and Building Law (PBL) is adopted, which in many ways attempted to modernize and improve the planning system. The PBL transferred the planning responsibility to the municipalities and gave the citizens more opportunities to influence the planning process. In relation to temporary permits, it expanded the time limit to a maximum of 20 years and modified the rules and wording to include a possibility to temporary alter a part of a building and its use.

"If building permits cannot be granted due to the regulations of sections 11 or 12, building permits for temporary measures may be given, if requested by the applicant. Such a permit shall be given if the application is supported by a detailed plan regulation for temporary use of building or land. A building permit referred to in the first subparagraph may be granted to construct, build or otherwise alter a building or other facility and alter the use of a building or building component. The permit shall be given for a maximum of 10 years. At the request of the applicant, the time may be extended by a maximum of five years at a time. However, the total time may not exceed twenty years.

(SFS, 1987:10)

An update of the PBL was introduced in 2008, in which wording and content was amended again. A change in wording from temporary ( ) to time-limited building permit ( ) was made, and the time limit was shortened to a maximum of 10 years.

8 chap. For a measure that meets one or some, but not all the requirements of section 11 or 12, a time-limited building permit may be granted if the applicant requests it and the measure is intended to last for a limited period of time. Such a permit shall be given if the measure is supported by a detailed plan regulation for temporary use of building or land. A time-limited building permit may be granted for a maximum of five years. At the request of the applicant, the time may be extended by a maximum of five years at a time. The aggregate time may exceed 10 years only

(SFS, 2007: 1303)

In 2010, a new PBL, which is still in force, was adopted. The purpose was to simplify planning (Karlsson and Olinder, 2016). Here, the only significant change in relation to temporary building permits was the expansion of the time limit to 15 years.

" time-limited building permit may be granted for a maximum of ten years. At the request of the applicant, the time may be extended by a maximum of five years at a time. The aggregate time may exceed fifteen years only if the permit is to be used for a purpose referred to in the

900.)"

The last amendment of the law, as mentioned before, was made in 2017 with the housing crisis as a background (Sveriges Riksdag, 2017, p.1). The proposal was adopted in February 2017, with a mandate from May 2017 to May 2023. In essence, it introduces a section that implies housing in

the area is temporary and that time-limited building permits may be granted even if the measure ibid, p.17)

33a / cease to apply U: 2023-05-01 by law (2017: 267) / For new housing and related measures, a time-limited building permit may be granted if requested by the applicant, the site can be restored, and the measure fulfills any prerequisite from

30-Such a building permit may be granted for a maximum of ten years. At the request of the applicant, the time may be extended by a maximum of five years at a time. However, the total time may not exceed fifteen years. Law (2017: 266).

(SFS, 2010:900)

4.4 Summarizing the context

A historical overview of the housing context and the refugee situation in Sweden shows the circumstances in which temporary permits have become a housing solution. We can say that the country has already found itself in a similar situation in the post-war period, although it must be noted that the political landscape is not the same as in the years of the Million Program. Years of deregulations in

municipal housing stock and similar measures, have made housing an expensive commodity for many people and left the authorities with fewer tools to deal with the situation. The influx of refugees has only made the shortage of affordable housing more visible. With more and more municipalities complaini

notions of crisis and suggestions for immediate solutions like increasing the construction efficiency and targeting specific groups have emerged. Against this background, temporary permits have become a viable solution. The

that the measure has gradually transformed from a provisional and peripheral measure meant for smaller structures, to appropriate for building housing.

5.0 Analysis

The overarching aim of this analysis is to find out how temporary permits are utilized in practice, by whom, for what purpose as well as the potential implications they have for different processes. However, looking through the lens of a , it is important not to focus only on the materialization of the exception, but also on the process of creation itself - its inception, discussion and reason behind it. Accordingly, the analysis will focus on two aspects: the discourse of exception and its materialization, as well as the relation between them in order to capture the nature and the effect these processes have or could potentially have. The discourse is being produced both by central state (political subjects, national agencies, etc.) and local state bodies, while the execution of the spatialization is usually taken by local state or private actors (municipalities, local social services, MHCs, private companies). It is important

to keep in mind that these processes, from inception to materialization, are not always straightforward and actors at different levels are sometimes negotiating and contesting. 5.1 Formative and legitimizing mechanisms

Trying to understand what informs the decisions behind using exceptional and de-regulating measures to deal with the housing issues, it was crucial to look into key documents. Laws, regulations and official documents

. As such, law is considered a productive force: -spatial relation izing, provided in the documents. This is in line with the suggestion to focus on the processes of transformation and emergence (Belcher et al., 2008, p.501) of spaces of exception, and the criteria of their definition (Schinkel and van den Berg, 2011, p.1914).

Discourses of disaster

The housing shortage was and remains to be a pressing issue that the municipalities have to handle. According to a survey conducted by the NHO, 243 out of the total 290 municipalities reported housing deficit for 2018 (Boverket, 2018). Although it is hard to interpret these reports since it is not clear which benefits would

not-refugee influx coupled with shortcomings in the housing condition pushed the municipalities to look for solutions, especially since the law obligates them to take in a certain number of migrants every year.

In a letter from 2015, the NHO suggests that changes in the PBL are needed in order for the municipalities to be able to cope with the emergency situatio

country are more or less forced to violate the law in order to cope with the emergency of the the government to issue special exemptions in cases of emergency, such as a refugee crisis. The suggested text goes as follows:

If an extraordinary event has occurred which involves a particularly extensive burden o be taken promptly, the government may issue anomalous and temporary regulations from this law, required for the necessary construction activities to proceed (Boverket, 2015a, translated by the author)

The official change in the law made in 2017 states If the influx of asylum seekers has been seekers to be organized quickly, the government may issue exemptions on regulations SFS, 2017:985).

This letter, and the subsequent change in the law, does not relate directly to the temporary housing permits, but creates a possibility for housing to be regulated differently in the proclamation of a state of exception in

the housing system and a

legitimized by the inability of the municipalities to follow the laws for providing housing. The threat to the stability of the (housing) order is personified in the asylum-seeker, seen in the

disasters and wars, thus making the stripped from (housing)

rights and standards, easier to legitimize. It is also suggested that the extent of the regulations that could be exempted should be vaguely regulated, which creates uncertainty on the effects it could potentially have and puts the potential dwellers in a zone of unpredictable living conditions.

Calls for greater efficiency

The slow construction of new housing which is unable to catch up with the population growth is often pointed to as the main reason for the housing crisis. Because of this, solutions for improving the efficiency of new construction are often pursued in the planning and building regulations, usually by searching for ways how to ease and simplify them. The amended law for temporary housing permits can be seen as a part of this trend.

In the proposition of the law (Sveriges Riksdag, 2017a) it is explained that due to the slow construction of new housing, new, more efficient measures are needed. The bill proposes that the PBL should introduce a special regulation on temporary building permits. It is stated that this

(p.1) of the existing possibilities.

long as it shows that the land would be restored to its original condition once the permit expires (Sveriges Riksdag, 2017a, p.4). Also, now it stipulates that a temporary permit can be given if it fulfils one, several or all the requirements for a permanent one. This is made for a reason that situations where, in order to achieve effective land use, it is appropriate to provide a temporary building permit despite the fact that the building meets all the conditions gulations in the Planning and Building Regulations (PBF in Swedish) were also made, related to: fire safety, hygiene, noise protection, accessibility, etc. (Boverket, 2015c).

or housing

being given and that argued

that for the municipalities this since an

examination of the temporary intent, and moreover, that

that municipalities can process more applications for temporary building permits for housing .

Through the years, exemptions from rules and lowering of the standards for housing have been done on several occasions, with the idea that it would accelerate construction rates (SOU, The proposal suggests eased

or lowered design requirements, such as for separate living room, requirements for the dimensions of kitchens and other rooms, requirements for hygiene room in each apartment, etc.

A danger from overcrowding is recognize negative aspects to

. Other technical requirements are also amended or eased, like fire protection, air ventilation in small homes, direct sunlight requirement, energy conservation requirements, waste management, elevators, etc. All of these exemptions were meant to provide lower construction costs and more flexibility in the design.

Suspension of law in the name of greater efficiency is the main feature of the state of exception. The exemptions from the aforementioned examples can arguably be conceptualized in the same manner. The temporary permits are meant to provide quicker, simpler, and more efficient way so that this process can take place. It is a sort of paradoxical case of sacrificing the housing explanation of the state of exception concept.

The (temporary) suspension of the rules creates a void in the law, an absence of regulations which leaves uncertainty over how the materialized temporary housing would look like and to what extent could it be exempted from regular norms and standards. It is noted that the permit can fulfill one, some, or all of the requirements normally needed for a permanent one. The decision of approving the quality of the dwellings is left to the municipal authorities, which in this case

housing - they will be the

. However, the potential to be a dweller in the

not equally distributed throughout society, and it hides a risk for systematic oppression to be (re)produced through housing. The temporary housing is meant to be for particular groups such as students and refugees. Even if it is not specifically assigned, it is likely that the potential dwellers would be the ones who are in the direst need of affordable housing the less affluent citizens.

Changes needed here and now

The aforementioned narratives of efficiency in the production of new housing are complemented with a discourse of urgency, arguing for measures that would have an effect sooner, rather than later.

Therefore, in the proposition for the law for temporary housing permits (Sveriges Riksdag, 2017a), it is explicitly pointed that the measure is suggested because short-term solutions are needed, to complement the long-term take on the housing shortage. The current situation

housing t

This becomes a key rationale for the introduction of the new law, since a call for greater efficiency does not necessarily imply an immediate, quick reaction.

It is clear that the housing system is perceived as being at a breaking point and the pressure is used to support the claim that solutions are needed quickly. Although some measures taken promptly can improve the housing situation for people in a desperate need of shelter, it is important not to lose sight of the reasons which contribute to the shortage of affordable homes. Too much focus placed on efficient and quick technical solutions would perhaps produce more units, but exemption measures and bypassing procedures increase the risk for inadequate housing. Moreover, it could obfuscate the systematic failures and thus prevent them from being

addressed proliferate. It is also

questionable if the amount of housing units is the real issue since the system that was gradually set to produce mainly for affluent groups, in order to make the largest profit, will always be short on affordable homes. Gray and Porter (2015) consider the basis on which the decision on

Legitimacy through temporariness Another legitimizing instrument

restored to its original condition is supposed to ensure that the buildings are really of temporary character. Additionally, the regulated expiration date, 1 May 2023, also renders the measure temporary. This is brought as an evidence that the long-term strategy would not be neglected (p.16),

.

However, the time-duration of the law has been debated. Motions from the Civil Committee discussing the proposal have raised the question, some saying that a time limit is not needed, others arguing that the proposed duration is too long - in practice it means that many of the homes may remain until 2040 (Sveriges Riksdag, 2017b, p.12).

position remains that since the need for housing is hard to predict, it is hard to assess how long should the measure stay. It is then concluded that the need for housing suggests that it should apply until the situation in the housing market has improved. In view of this, the committee finds, like the government, that six years appear to be an appropriate period of validit

Similar reasoning is used for the relaxations and lowering of the standards for student and youth

housing, where again esigning

a smaller home is reasonable for this type of housing because it is meant (Boverket, 2013, p. 57).

Legitimacy grounded on temporariness is two-fold: based on the temporary status of the law change, and the actual temporary character of the buildings. Although the exceptions are time-regulated, as it was pointed, the 15 years duration of the permit means that neighborhoods with

temporary houses would last until 2040, which from a dweller a

perspective could mean that one could potentially live in a home with lower standards for a large portion of his/her life (childhood).

Although temporary, the measure can potentially have long-lasting effects on people lives and understanding of housing provision, even urban planning. Baptista (2013) claims that legality of exceptions rely on their temporary status, this runs counter to institutionalized

. Moreover,

or exceptional powers of intervention routinely operate outside of traditional democratic forms Furthermore, they can create a long-lasting understating that low standards are acceptable for some groups of people and normalize the notion that insecure and substandard conditions are an acceptable aspect of life in expensive cities. The effect on individuals can also be long-term, as living in uncertain and stressful circumstances can have prolonged consequences. Diken (2004) shows

5.2 Materialization of the temporary housing permits

The laws and documents related to temporary permits can be considered their initial and spatial-legal formative mechanism. This mechanism includes a potentiality, since it does not always produce the same spaces, or for that matter materialize at all. The power that decides when the law becomes materialized in an actual physical form is in the hands of the local government, more precisely in the planning authorities. In order to get an insight into the s it produces.

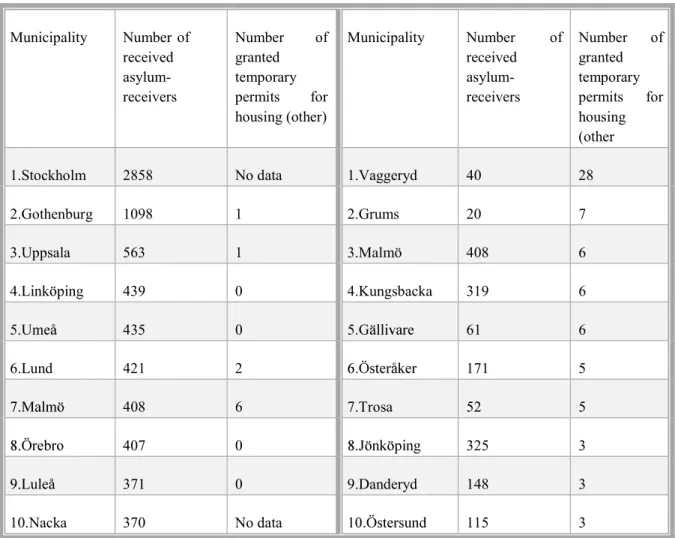

where they were granted in the last two years and how many. Combined data from the NHO and the Migration Office (Appendix 1) offers a way to find out if there is a correlation between issuing of temporary housing permits and the number of accommodated asylum-receivers per municipality. Municipality Number of received asylum-receivers Number of granted temporary permits for housing (other) Municipality Number of received asylum-receivers Number of granted temporary permits for housing (other 1.Stockholm 2858 No data 1.Vaggeryd 40 28

2.Gothenburg 1098 1 2.Grums 20 7 3.Uppsala 563 1 3.Malm 408 6 439 0 4.Kungsbacka 319 6 435 0 61 6 6.Lund 421 2 171 5 408 6 7.Trosa 52 5 407 0 325 3 371 0 9.Danderyd 148 3 10.Nacka 370 No data 115 3

Table 1. The left partition ranks the top ten municipalities by number of assigned asylum-receivers, the right partition ranks the top ten municipalities by number of granted temporary housing permits. The data is for 2017. Sources: Boverket and Migrationsverket (see Appendix 1 for a detailed table)