Examining Cross-Sector Collaboration in Indonesian

Socially-Driven Organization

Towards Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals

Mohammad Ridwan

Tapiwa Bokosi

Main Field of Study - Leadership and Organization

Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organization (one year) Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organization for Sustainability (OL646E) 15 credits Spring 2020

Acknowledgements

We want to thank our supervisor Peter Gladoic Håkansson for the help and guidance rendered during this thesis and for inspiring us to undertake the challenge of the topic about Cross-Sector Collaboration in Indonesian socially-driven organizations. The input and conversations we had encouraged and empowered us with new ideas and thoughts. We would not have been able to do the project without his help. We would also like to also thank our teachers Hope Witmer, Jonas Lundsten, and Fredrik Björk, for your guidance, wisdom, and knowledge throughout the program.

Generally, we would like to appreciate all of the leaders of the research subjects who took part in this master thesis project. It was great to meet so many people who are passionate about the work they do in the sustainable development realm. We are always amazed and motivated to meet all of the warriors of humanity who are determined to set up a better tomorrow for everyone on this planet. Special gratitude is given to all Indonesian fellows, youth leaders, activists, and change-makers (Relawan Muda Riau, After School, Pendar Pagi Foundation, Aventure-ID, I-YES Indonesia, Gema Mahardika Riau, Mentoring Youth, Seribu Guru Riau, Ruang Desa Foundation, and Yayasan Indonesia Hijau) who have inspired us to move forward not only with the thesis but also with life. Your contribution towards this thesis on providing authentic and valuable data, participation, and feedback throughout the process is priceless and countless. This thesis would not have been possible without your assistance. All in all, you all are the body and soul of the thesis. Finally, we would like to thank our family for the encouragement and support rendered before and during our studies.

In conclusion, you all are the reason we have reached this far.

Thank you

Abstract

Cross-sector collaboration is an innovative strategy and practice implemented by socially-driven organizations towards reaching the sustainable development goals. However, it is challenging to develop successful, effective collaborations that are important to cross-sector dynamics and political contexts, particularly in developing countries like Indonesia. Therefore, the paper aims to examine how socially-driven organizations in Indonesia collaborate with other sectors by using certain factors. In addition, this research also investigates the success and failure factors of collaboration among sectors. To meet this goal, this paper examines three essential factors for cross-sector collaborations; power distribution, communication, and shared goals from three different sectors; socially-driven organizations, governments, and societies.

The research was conducted through semi-structured interviews by using Zoom, an online-based video conferencing platform, for video communication. Furthermore, the interviews were analyzed by the content analysis method, while the Cross-sector Collaboration Framework developed by Bryson, Crosby, and Stone (2015) was used to identify the sectors and factors of collaboration. The results showed that the three collaborative factors that are used in this research significantly affect the development of the organization to collaborate with the external three sectors. Furthermore, quality education becomes the most common goal of all of the collaborating partners in question. In addition, face to face communication, the use of social media have a significant impact on the communication, promotion of the goals and defining the power distribution to the other collaboration sectors. However, communication breakdowns, unclear goals, powerless figures, and bureaucratic procedures become the main challenges of collaboration. Therefore, organizations need to develop alternative ways to tackle these issues.

Keywords: cross-sector collaboration, socially-driven organization, Sustainable Development Goals, Semi-structured interview, content analysis, communication, power distribution, and shared goals Words number: 19736

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements 2 Abstract 3 Table of Contents 4 List of Tables 7 List of Figures 7 List of Abbreviations 8 1. Introduction 1 1.1. Background 11.1.1. Sustainable Development in Indonesia 1

1.1.2. Socially-driven organization in Indonesia 2

1.1.3. Cross-Sector Collaboration 3

1.1.4. Social innovation development in Indonesia 4

1.2. Thesis Structure 5

1.3. Research Details 6

1.3.1. Research Problem 6

1.3.2. Research Aim and Purpose 6

1.3.3. Research Questions 6

1.3.4. Research Method 6

1.4. Significance of the project 7

2. Theoretical Framework 8

2.1. Selection of the framework 8

2.2. Selection of the factors 12

2.2.1. Power Distribution 12

2.2.2. Communication 12

2.2.3. Shared Goals 13

2.3. Selection of the collaboration sectors 13

2.3.1. Socially-driven organization–socially-driven organization collaboration 14

2.3.2. Socially-driven organization–government collaboration 14

2.3.3. Socially-driven organization – society collaboration 14

3. Research Methodology 15

3.1. A qualitative research approaches 18

3.2. Epistemology and ontology 19

3.3. Data collection methods 19

3.3.1. Semi-structured Interviews 19

3.5. Ethical issues 21

3.5.1. The ethic of interviewing people 21

3.5.2. Confidentiality and Anonymity 21

3.5.3. Positionality 21

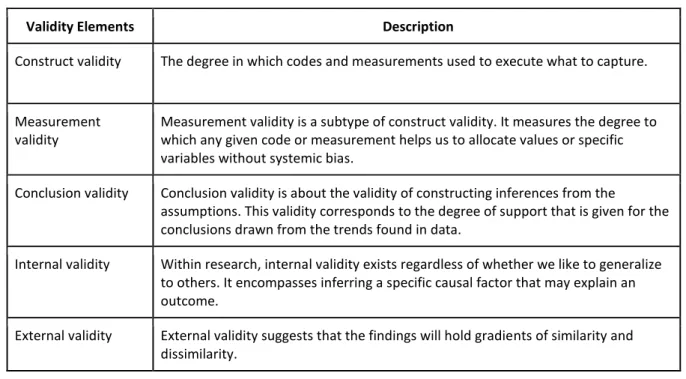

3.6. Reliability and Validity 22

3.6.1. Reliability 22

3.6.2. Validity 22

3.7. Limitations of the study 23

4. Result 24 4.1. Socially-driven organization – socially-driven organization collaboration 24

4.1.1. Communication 24

4.1.2. Shared goals 25

4.1.3. Power distribution 25

4.2. Socially-driven organization – governmental collaboration 26

4.2.1. Communication 26

4.2.2. Shared goals 27

4.2.3. Power distribution 27

4.3. Socially-driven organization – society collaboration 27

4.3.1. Communication 28

4.3.2. Shared goals 28

4.3.3. Power distribution 29

5. Discussion 30

5.1. Perceptions of cross-sector collaboration between socially-driven organizations 30

5.1.1 Communication 30

5.1.2 Shared goals 30

5.1.3 Power distribution 31

5.2. Perceptions of cross-sector collaboration between socially-driven organizations and the

government 31

5.2.1 Communication 31

5.2.2 Shared goals 32

5.2.3 Power distribution 32

5.3. Perceptions of cross-sector collaboration between socially-driven organizations and

society 33 5.3.1 Communication 33 5.3.2 Shared goals 33 5.3.3 Power distribution 34 6. Conclusion 35 6.1. Concluding remark 35

6.2. Implication 36

6.3. Recommendation for further research 36

References 37

List of Tables

Table 1. Objective and task of socially driven organization in Indonesia (Krishna, 2003) Table 2. Sustainable Development Index Indonesia 2009-2018 ( Maryanti and Nursini, 2020)

Table 3. Comparison of major cross-sector collaboration-related theoretical frameworks (Bryson, Crosby & Stone, 2015).

Table 4. Validity elements (Bellamy & 6, 2012)

List of Figures

Figure 1. SDG Goal 17: Partnerships For The Goals Source: United Nations website (retrieved from https://www.un.org/partnerships/content/sustainable-development-goals)

Figure 2. Community Empowerment Program in Indonesia by JICA (Kenny & Fanany, 2017) Figure 3. Three sectors of sustainability (Giddings et al, 2002)

Figure 4. Theoretical framework for the design of cross-sector collaboration (Source: Bryson et al., 2015) Figure 5. The qualitative research phenomenon (Silverman, 2015)

Figure 6. I-YES organization (2017). Retrieved from https://iyesindonesia.wordpress.com/ Figure 7. Aventure organization (2019). Retrieved from https://www.aventure-id.com/ Figure 8. Pendar Pagi Foundation (2012). Retrieved from http://pendarpagi.org/en/ Figure 9. Usaha Desa Sejahtera (2018) Retrieved from: https://www.usahadesa.com/ Figure 10. RMR (2018). Retrieved from http://www.relawanmudariau.com

Figure 11. Seribu Guru (2019). Retrieved from: https://www.1000gurufoundation.org/ Figure 12. After School Pekanbaru (2019). Retrieved from:

https://www.instagram.com/p/B8IHMTDlm5d71E1hnddWQA9KYP7kB5vcSgCI8w0/ Figure 13. Yayasan Indonesia Hijau (2018). Retrieved from

http://www.yayasanindonesiahijau.org/profil/

Figure 14. Mata Garuda Riau (2019). Retrieved from http://matagarudalpdp.org/ Figure 15. ASEC (2016). Retrieved from: https://asec.web.id/about/

List of Abbreviations

ASEC: Actual Smile English Club CEO: Chief Executive Officer

CSSPs: Cross-Sector Social Partnerships HDI: Human Development Index HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus

I-YES: Indonesian-Youth Education and Social JICA: Japan International Cooperation Agency NGO: Non-Governmental Organization RMR: Relawan Muda Riau

SDGs: Sustainable Development Goals SDI: Sustainable Development Index UN: United Nation

1

1. Introduction

This is the first part of the thesis that will discuss the main themes of the paper and explain the thesis's fundamental background. This chapter consists of six sub-chapters containing the background, research problem, research aims and objectives, research questions, significance of the research, and research structure.

1.1. Background

A study by Stephan, Patterson, Kelly, & Mair (2016) concluded that societal challenges in public health, education, social inequality, and environmental pollution have been overgrowing in our society. Before societal challenges become too devastating, implementing a constructive solution is a goal to tackle the challenges (Carroll, 1979; Hartman, Hofman, Stafford, 1999; Rondinelli, London, O'Neill., 2006). Therefore, Hesselbein and Whitehead (2000) claimed that the complexity and interconnectedness of societal challenges are too large and complicated to be solved by one organization or one sector alone. These organizations cannot thrive or survive with visions confined within their organizations' walls, even though they have some resources and talents to tackle social issues towards sustainable development (Hesselbein and Whitehead, 2000). In relation to these issues, a study on Integrative Leadership and the Creation and Maintenance of Cross-sector Collaboration (2010) concluded that major social issues could only be addressed effectively if many organizations collaborate (Crosby & Bryson, 2010). Therefore, organizations need to make alliances and look beyond their confinements to achieve more significant results and meet societal challenges (Hesselbein & Whitehead, 2000).

1.1.1. Cross-sector collaboration and its significance

Several studies have been done on the significance and importance of cross-sector collaboration in achieving sustainable development. According to Bryson, Crosby, and Stone (2006), cross-sector collaboration is an affiliation of government, business, the non-profit and community to address some of the most complex social challenges of society. Another study defined cross-sector collaboration as the remediation of social challenges that cannot be solved easily by individual organizations without the participation of multi-organizations (McGuire, 2006). To address these social challenges and achieve definite community objectives, Patrono, Marciano, Jeong (2018) claimed that various sectors of society, such as corporations, NGOs, philanthropy, media, culture, and government, must work together to tackle the challenges efficiently. Hood, Logsdon, and Thompson (1993) also agreed that there is a more crucial need for collaboration because societal challenges are getting more sophisticated. Concerning this statement, Meadowcroft (1999) claimed that cooperation among all stakeholders is the highest priority in developing national sustainable development policies and practices. This requires strong political will and contributions from all stakeholders (Meadowcroft, 1999). Furthermore, Crosby and Bryson (2010) highlighted the necessity for many organizations to collaborate to tackle many major social problems. 1.1.2. Cross sector collaboration in Indonesian context

In Indonesia's context, many cross-sectoral collaborative studies have also been done, stressing the need for cross-sector players to build alliances to resolve societal issues. These studies include cross-sector collaboration in poverty reduction, HIV prevention, disaster risk reduction, tuberculosis care, and waste management (Edi, 2015; Raharja & Akhmad, 2020; Djalante, Garschagen, Thomalla & Shaw, 2017; Surya et al., 2017; Willmott & Graci, 2012). Notwithstanding Indonesia's positive performance in achieving the MDGs (see appendix 9) and SDGs (see appendix 6), the question remains how socially-driven organizations collaborate with other sectors to achieve organizational objectives through the SDGs, as social problems are difficult to be addressed by one sector alone. Therefore, aligned with the UN Global Goals, cross-sector collaboration among public, private, and NGO/civil society sectors will be the key to achieving progress against the targets outlined in the Agenda 2030 (Stiles & Davies, 2016) if leaders want to reach sustainability. To achieve this aim, the authors investigate the experience, perception, and success and

2 failure factors of cross-sector collaboration among socially-driven organizations, governments, and society in Indonesia.

1.2. Research Problem

With the world facing dynamic, interdependent, evolving threats, and wicked sustainability problems, the efforts to tackle them are not adequate to resolve by an individual organization (Dentoni, Bitzer, & Schouten, 2018). Crosby and Bryson (2010) claimed that without cross-sector collaboration, organizations fail to address complex sustainability challenges due to a lack of efficient resources, knowledge, and skills. Hence, it calls for various society sectors to address the challenges efficiently (Patrono, Marciano, Jeong, 2018). While cross-sector collaboration is widely used to solve complex and wicked problems of our time, building and managing them can be extremely challenging (Graham, 2019; Bates, 2013; Schmida, 2020). According to a study done on cross-sector collaboration by the Hilton Foundation, 75% of collaborations have failed to meet expectations and have experienced low efficiency and effectiveness (Schmida, 2020). Another study by Vithya Srichareon, MacGill, and Nakawiro (2012) argued that there is no clear guidance for socially-driven organization actors about mechanisms for collaboration with the other sectors to meet sustainable development since sustainability is a challenging concept to apply in practice. Concerning to Indonesian context, Edi (2014) claimed that the government, civil society, NGOs, and companies are the key players in collaboration but the research mostly conducted from the business viewpoint (Arya & Salk, 2006; Bennett, Mousley, Ali-Choundhury, 2008; Murphy, Perrot, Rivera-Santos, 2012; Rathi, Given, Forcier, 2014). Since the research on socially-driven organization, government, and society is not fully available in Indonesian context, there is a need to investigate more on this area. Therefore, through this study, the authors aim to address the knowledge gap that exists in cross-sector collaboration processes and dynamics between socially-driven organizations and government and society in the Indonesian context.

1.3. Research aim and objectives

The following research objectives are created as a framework to achieve the purpose of this study. Hence, the objectives of this study:

1. To understand how cross-sector collaboration works among socially-driven organizations, government, and society in the Indonesian context.

2. To identify the success and failure factors of collaboration by exploring the experiences of socially-driven organization actors in dealing with government and society in Indonesia.

3. To contribute to cross-sector collaboration knowledge, specifically in the three sectors within Indonesian context.

1.4. Research Questions

1. How do socially-driven organizations collaborate efficiently among socially-driven organizations, government, and society to achieve organizational development in Indonesia?

2. What are the perceptions of socially-driven organization actors collaborating with other organizations, government, and society related to success and failure in the collaboration in Indonesia?

1.5. Significance of the project

As mentioned before in chapter 1.2 (research problem), designing and implementing successful and effective collaboration has been proven to be particularly challenging. In addition, there is a lack of research in Indonesia, specifically in examining the depth of the cross-sector collaboration between socially-driven organization actors to the government and society (Edy, 2014). However, this area of research has received more attention in recent decades. Thus, one of the purposes of this study is to investigate the dynamics and processes of cross-sector collaboration and identify the success and failure factors. Besides, this research may also provide data that can be used by other studies and researchers either for reference or other

3 objectives (Landøy, 2017). This is especially for researchers who work on the same subject in an Indonesian perspective or another field area, either qualitative or quantitative research (Edi, 2014).

A study by Lundvall, Johnson, Anderson, and Dalum (2002) has been explained before that collaboration among sectors affects the development of innovation. In relation to social innovation developed by the organization, Pratono, Marciano, and Jeong (2018) claimed that social innovation gives millions of underprivileged groups in Asian countries a promising pathway for improved quality of life. Therefore, the authors anticipate that this research can help social innovation actors achieve sustainability by forging strong and successful cross-sector collaborations and partnerships. Furthermore, the authors hope positive cross-sector collaborations and partnerships will bear fruit in Indonesia's strategy towards poverty reduction, quality education, and unbalanced income distribution (British Council, 2018). Lastly, the authors hope that this study will shape the success of cross-sectoral collaboration between socially-driven organizations and key partners.

1.6. Thesis Structure

The thesis consists of six chapters. Chapter 1 introduced the background of the subject area, including the context, the phenomenon, the reason, and the importance of cross-sector collaboration and socially-driven organization. The problem statement explains the study's research gap and goal, the intent of the study, the research questions, the study's significance, and the thesis structure to direct the reader through each section. Chapter 2 addresses the study's theoretical context based on cross-sector collaboration. Chapter 3 illustrates the research methodology and justifies the selection of research philosophy, approaches, strategies, data collection methods, and data analysis. Chapter 4 demonstrates the study's main findings and the data gathered from the research. Chapter 5 compares the findings by reflecting on the literature. Finally, Chapter 6 summarises the research findings, shows the research's limitations, and provides recommendations for future research.

4

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Cross-sector collaboration

A study by Bryson, Crosby, and Stone (2006) concluded that cross-sector collaboration is a knowledge, tasks, abilities, and resources sharing mechanism by more than two sectors to achieve the goals that might not be accomplished by a single organization alone. Collaboration structure may range from informal and temporary duties to highly formal hierarchical structures (Simo & Bies, 2007). Since the collaboration work has increased considerably over the past years (Selsky & Parker, 2005), diverse types of collaboration sectors have been formed and incorporated (Becker & Smith, 2018; van Huijstee, Francken & Leroy, 2007) such as companies, governments, and civil societies. Another study claimed that the government is categorized as the collaboration sector; however, other sectors such as business, NGOs, foundations, higher education, and community groups are often counted as well (Crosby & Bryson, 2010). Furthermore, the characteristic of cross-sector collaboration is marked by pursuing social issues, economic growth, sustainable environment (Selsky & Parker, 2005), and contributing to fulfilling the SDGs goals (Albrectsen, 2017).

In line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (see appendix 7), the United Nations has deemed collaboration as one of five universal building blocks of all UN Global Goals, arguably the leading agenda for systemic change at a global scale (UN, 2020). In addition, the United Nations recognizes cross-sector collaboration as a mechanism to create social value (McDonald & Young, 2012), which can not be addressed by a single sector and may not be believed as a sustainable solution. (Austin, 2000a, 2000b; Fadeeva, 2004; Googins and Rochlin, 2000; Waddock, 1988). Furthermore, cross-sector collaboration is a crucial trait any organization needs to adapt to reach sustainability. It is known as a survival strategy for organizations to get through (Gazley, 2016). Therefore, cross-sector collaboration is needed to examine organizations' ability to identify partners, organize relationships and networks, and learn to manage knowledge cooperatively to create a more significant social impact (Chen, Lin, & Yen, 2014).

Related to the concern of collaboration, Ridho, Vinichenko, and Makushkin (2018) agreed that collaboration with different socially-driven organizations and multiple stakeholders among government, private sector, academia, and civil society from all countries was demanded to meet the 17 SDGs goals (see appendix 7). In addition to this, Florini and Pauli (2018) claimed that SDGs goals number 17 (see appendix 6) linked directly to cross-sector collaboration. To be more specific, after evaluating the SDGs report (United Nations, 2020), the authors concluded that cross-sector collaboration specifically relates to SDG goal number 17 target 17.9, 17.14. 17.16, 17.17, 17.18, and 17.19 (see appendix 6). Cross-sector collaboration aligns with United Nations SDGs goal number 17 is shown in Figures 1.

5

2.2. Socially-driven organizations

A study by Geok (2017) concluded that socially-driven organizations are evolving to fulfill the needs of societal challenges. It is also mentioned that socially-driven organizations, including their policies and institutions boards, need to develop capacity and capabilities and stay relevant by hiring, retaining and motivating the right people to address the complexities of social challenges and beneficiaries' needs. In addition, socially-driven organizations are recognized as an ecosystem of key players and partners working towards sustainable development (Sosial, 2018). The ecosystem includes enablers, impact investors, donors, local government, academia, community, resources exchange, capacity building, and organizational development.

Referring to the Indonesian context, a study by Antlöv, Ibrahim, and Tuijl (2006) said that the fall of President Soeharto in 1998 and the democratic transition in Indonesia had brought many changes in civil society. Since then, Antlöv, Ibrahim, and Tuijl (2006) claimed that the number of socially-driven organizations within civil society significantly improved. It happened because spreading democracy opened new possibilities for civil society organizations in Indonesia to develop a civil society organization's freedoms and transparency frameworks (Antlöv, Ibrahim, & Tuijl, 2006). As a result of this social movement, they found ten thousand civilian society organizations in Indonesia that year. Some of them are categorized as social groups, mass participation organizations, unions, ethnic groups, religious organizations, civic organizations, NGOs, professional societies, and political affiliates. Furthermore, Meadowcroft (1999) suggested that cooperation among all stakeholders is the highest priority in developing national sustainable development policies and practices and requires strong political will and contributions from all stakeholders.

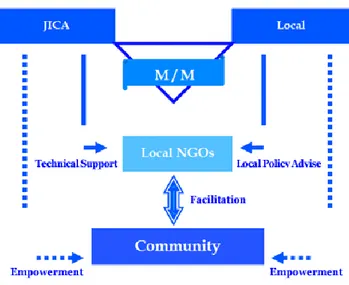

As an illustration, table 1 and figure 2 below describes the objective and task of a socially-driven organization, as well as, the community empowerment program among sectors in the Indonesian context. Table 1. Objective and task of socially-driven organization in Indonesia (Krishna, 2003).

Type Nature Unit of observation and action

Intended result Tasks in support Time horizon for tasks Social-driven organization Activity Community organizations, * facilitated by and interacting with outsiders Better physical and social infrastructure for communities - Decentralization - Authorize and inform communities, and link them better with local governments

- Short to medium term

6

Figure 2. Community Empowerment Program in Indonesia by JICA (Kenny & Fanany, 2017)

2.3. Sustainable development goals in Indonesia

A study by Ridho, Vinichenko & Makushkin (2018) reported that political leaders in the General Assembly of the United Nations launched and adopted a global vision called the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with 17 goals as its core (see appendix 7). To achieve these SDG goals, Vangen, Hayes, and Cornforth (2015) claimed that cross-sector collaboration holds power for growth in all goals and targets in sustainable development. Furthermore, a study by Giddings, Hopwood, and O'brien (2002) argued that sustainable development is a debated topic, with ideas influenced by the diversity of individuals and organizations worldwide. They continued that it is typically viewed as the intersection of three sectors: environment, society, and economy, conceived as distinct but interrelated entities. As an illustration, Giddings, Hopwood, and O'brien (2002) have presented the concept of sustainability in figure 3 below.

Figure 3. Three sectors of sustainability (Giddings, Hopwood, & O'brien, 2002)

In regards to sustainable development in Indonesia, several studies on Indonesian development claimed that the National Development of Indonesia is focused on “Pancasila” as its goal and direction (Habibie, Hardjosoekarto & Kasim, 2017). They further concluded that national development in Indonesia seems to be following the declaration of the Sustainable Development Goals. Another study by Pratasa (2019) claimed that Indonesian Development Agenda following SDG goals were organized in the form of programs, indicators, and funding support. The Indonesian National Development also specified that all sectors are compatible with SDGs (Pratasa, 2019). Concerning the SDGs index, Maryanti and Nursini (2020) have reported the Indonesian Sustainability Development Index (SDI), as shown in table 2.

7 Table 2. Sustainable Development Index Indonesia 2009-2018 (Maryanti and Nursini, 2020)

Furthermore, Suwarno (2019) explained that knowledge of the SDGs is crucial as a foundation for Indonesian socially-driven organizations to face the challenge of collaboration, promoting equal opportunity, philanthropy, and voluntarism. By knowing the standard, law, and recent development of SDGs, socially-driven organizations might know how to move around and mobilize around the SDGs goals (Hege and Demailly, 2017). Concerning this matter, there are many ways to understand, promote, and explain SDGs' recent development. One of the best promotion tools is social media. A study by Killian et al. (2019) claimed that social media has tremendous potential to meet the SDGs, especially in areas like gender (Chin & Jacobsson, 2016). Another study concluded that social media triggers the response from stakeholders and raises people's awareness (Gómez-Carrasco, Guillamón-Saorín, & García-Osma, 2020). Furthermore, all media significantly impact ensuring, educating, and providing a public discussion forum (Irwansyah, 2018).

2.4. Bryson’s cross-sector collaboration frameworks

This section explains each aspect of Bryson et al. 's (2015) framework, including the overview of 26 propositions/factors as needed in cross-sector collaboration work (see Figure 7). In addition, the fundamental factors in collaboration will be explained concerning choosing the most available factors for this research.

2.4.1. Bryson’s cross-sector collaboration aspects and factors

Concerning the collaboration aspects, the Bryson framework takes into account the following aspects: (1) general antecedent conditions; (2) initial conditions; (3) collaborative processes; (4) collaborative structures and (5) tensions and conflicts (6) outcomes and accountability (Bryson et al., 2015). The collaboration aspects including their factors are explained as follows.

General antecedent conditions

Based on the previous studies, it explained that the institutional environment is highly crucial for cross-sector collaboration on policy and public problem-solving as it requires broad interaction across jurisdiction sectors (Sandfort & Moulton, 2014; Scott & Meyer, 1991) that may affect the outcomes, structure, and purpose of the collaboration significantly (Bryson et al., 2015; Dickinson & Glasby, 2010; Mcguire & Agranoff, 2011). For example, public administrators are strongly required by the government policy to manage cross-sector collaboration to receive public funds or obtain grant programs. (Stone, Crosby and Bryson 2013). In addition, Bryson et al., (2015) argued that organizations must build legitimacy by using structures, processes, and strategies within their environment to foster effective cross-sector collaboration. Furthermore, political dynamics may also significantly influence the development of cross-sector collaboration (Bryson et al., 2015). This political environment is also connected to the policy of windows of opportunity (Lober, 1997). Based on the definition of policy windows of opportunity, a study suggested that the forming of collaboration depends on the interaction of problem and solution (Kingdon, 1995) by creating opportunities by mobilizing stakeholders and resources (Lober, 1997).

8 Another aspect of general antecedent conditions is the need to address a public issue. Some studies concluded that non-governmental collaborators would be more effectively utilized to address the public problems as they have additional skills, prior financial resources, and experience (Demirag et al., 2012; Holmes & Moir, 2007 in Bryson et al., 2015) Besides, based on Kettl (2015) in Bryson et al., (2015), public managers and policymakers are acutely aware that addressing public issues may not be solved by the government alone. He continued that to distribute the risk, provide efficient approaches, and strengthen the window of opportunity, and it needs the involvement of businesses, private sectors, non-profit, and community partners. He claimed that this is the key reason to form cross-sector collaboration.

Initial conditions, Drivers and Linking Mechanisms

The presence of initial conditions or specific drivers plays a significant role in forming cross-sector collaborations as the environmental condition cannot stand alone to facilitate the development of cross-sector collaboration (Bryson et al., 2015). Besides, the other aspect discussed in the initial condition is the significance of pre-existing and existing leadership, which were addressed by some theoretical frameworks. In contrast, the importance of leadership characteristics was discussed by empirical works (Bryson et al., 2015). Some of the important leadership characteristics are educational qualifications, age, problem-solving ability (Esteves et al., 2012; McGuire & Silva, 2010), collaborative mindsets (Cikaliuk, 2011), and the ability to increase the understanding of different stakeholders on framing the issue as well as the relevance of the issue for them (Page, 2010).

A study claimed that agreement on the problem definition and the collaborative objectives consider the stakeholders' interdependency (Bryson et al., 2015). Other researchers continued to have great significance for cross-sector collaborations (Bies & Simo, 2007; Gray, 1989 cited by Bryson et al., 2015). Besides, collaboration accuntability and shared goal can be promoted byformal collaboration agreements on the composition, processes, and mission. (Babiak & Thibault, 2009; Gray, 1989).

The other aspect discussed in the initial condition is the pre-existing relationships and networks. According to Bryson, Crosby, & Stone (2014), Bryson et al. (2011) in Bryson et al. (2015), pre-existing relationships and networks has a vital role because the previous integrity and reputation can be recognized by other stakeholders. The positive collaboration in the past create social constructs that enable and protect future collaborations and exchange (Bryson et al., 2015; Jones, Hesterly, and Borgatti, 1997; & Ring and Van De Ven, 1994)

In the involvement and commitment of boundary-crossing leaders aspect, Crosby and Bryson (2010) call leaders as champion and sponsor. Their key characterteristics include: (1) having collaboratve mindset (Cikaliuk, 2011), (2) ability to frame understandable issue (S. Page, 2010), (3) problem solving, and (4) relevant age and qualification (Esteves, Franks, & Vanclay, 2012; McGuire & Silvia, 2010).

Collaborative structure

The capacities, capabilites and leadership skills of a partner bring into the network, determine the network structure that are triggered by norms, rules and enggagement practice (Bryson et al., 2015). In addition, structured can be reformed every single time due to uncertain membership and over collaboration (Vangen & Huxham, 2012). Furthermore, a study by Siv Vangen and Winchester (2014) concluded that crossing national restriction cause a dynamic of structure (Siv Vangen & Winchester, 2014).

Collaborative process

Previous research on Bryson, Stone, and Cosby’s cross-sector collaboration theoretical framework indicates that processes and structures work closely together in fostering effective cross-sector collaboration, bridging differences among stakeholders, helping partners to establish inclusive structures, creating a unifying vision, and managing power imbalances (Bryson et al., 2015). These inclusive processes, otherwise known as collaboration processes, include trust and commitment, communication, legitimacy, and collaborative planning, which will be discussed below.

9 According to Casimir, Lee, and Loon (2012), trust and commitment are often depicted as the essence of collaboration. Another study claimed that trust comprises interpersonal behavior, confidence in organizational competence, expected performance, and a common bond and sense of goodwill (Chen & Graddy, 2010).

Koschmann, Kuhn, and Pfrarrer (2012) argue that communication creates collaborations as higher-order systems that are conceptually distinct from individual member organizations. Another study claimed that regular face to face communication is the primary driver in effective collaboration and creating trusting bonds between partners (Kapur & Steuerwald, 2019). A previous study also claimed that face-to-face contact is the most refined communication type, as it can convey many indicators, vocal inflection, and body language. In addition, face-to-face contact encourages mutual meaning with reciprocal interaction and personal attention, emotions, and feelings that fill the discussion (Daft, Lengel, & Trevino, 1987).

An organization seeking to acquire necessary resources must build legitimacy by using structures, processes, and strategies deemed appropriate within its environment (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012). In collaboration, Bryson et al. (2015) mentioned that both external and internal legitimacy is critical. In internal legitimacy, stakeholders ought to feel inclusivity in decision-making settings (Ansell and Gash, 2008).

According to Mintzberg, Ahlstrand, and Lampel (2009), collaborative planning has two approaches; deliberate and emergent. The deliberate, formal plan involves careful advance articulation of mission, goals, and objectives; roles and responsibilities; and phases or steps, including implementation. In the new approach, a clear understanding of purpose, goals, roles, and action steps emerges over time as conversations encompass a broader network of involved or affected parties (Koppenjan 2008; Vangen & Huxham 2012). In conclusion, Clarke & Fuller (2010) claimed that deliberate and emergent planning are likely to occur at both collaboration and individual collaborating organizations.

Tensions and conflicts

According to Bryson et al. (2015), conflicts and tensions can likely affect and influence internal workings (Bryson et al. 2015). These conflicts involve power imbalances, competing for institutional logics, autonomy vs. interdependence, stability vs. flexibility, inclusivity vs. efficiency, and interval vs. external legitimacy.

Related to this issue, a study confirmed that using effective conflict management practices, such as extensive use of regular meetings to raise and resolve issues, and other kinds of “boundary work” (Quick and Feldman 2014) are essential. Another study by Saz-Carranza and Longo (2012) found that collaboration actors adopted two practices to manage competing logics: involving and communicating with a wide array of stakeholders to build external legitimacy and facilitating joint-learning spaces to promote internal trust. Outcomes and accountability

According to Bryson, Stone, and Crosby’s viewpoint (2006), cross-sector collaboration is more likely to be successful when collaborative partners have an accountability system that tracks inputs, processes, and outcomes. As stated in the study of Simo and Bies (2007), this requires partners in collaborations to be resilient and engaged in regular assessment, hence the model provides partners with an existing framework and accountability system. Therefore, the theoretical framework on cross-sector collaboration developed by Bryson, Stone, and Crosby includes assessing Accountabilities and Outcomes.

Creating and sustaining cross-sector collaborations provides a public value that could not be designed and implemented alone (Simo & Bies, 2007). This type of collaboration involves organizations using collaborative partners' strengths while compensating for their weaknesses. The former is linked to managing costs effectively while meeting the public's needs and aspirations (Simo & Bies, 2007). In addition, the goals, motivation, and “gain” of partners must be realized, by producing lasting public benefits at a reasonable cost, in other words, by linking individual and organizational self-interests and capabilities with the common good (Bryson et al., 2015).

10 An accountability system is a complex issue when talking about cross-sector collaboration because it is unclear who takes accountability and what the multiple stakeholders are competing in defining results and outcomes (Bryson et al., 2015). They explained that accountability helps collaborators manage, track, and measure inputs and resources to measure and document outcomes and results.

In conclusion, Bryson et al. (2015) have identified a diagram of aspects and factors that contribute to the success of the cross-sector collaboration, which includes sub-factors, such as collaboration processes and structures, leadership, accountabilities, and conflicts and tensions that can be seen in figure 4 below.

Figure 4. Theoretical framework for the design of cross-sector collaboration (Source: Bryson et al., 2015).

2.4.2. The Fundamental factors of Bryson’s cross-sector collaboration

framework

After reviewing 196 papers and three books published within the time frame 2007-2015, Bryson et al., (2015) have concluded the list of possible collaboration aspects and factors in their framework, as mentioned in chapter 2.4.1. However, due to the time limitation, the authors did not examine the implementation of all 26 factors; instead, the authors chose the fundamental factors which have the most supporting papers. The collection of published academic papers related to each factor was identified to determine which collaboration factors are more fundamental, more available, and contribute to cross-sector collaboration.

11

In relation to deciding which factor is more fundamental, the authors scanned the first five pages (50 academic papers for each factor) on Google Scholar. Then, the authors grouped each paper according to the factor. The process continues until all 26 factors with its 50 papers are scanned and grouped. Next, the authors analyzed each group of factors and decided which factors have more supporting academic papers. As a result, based on appendix 8, after scanning the first 50 academic papers for each factor and considering the keywords used in the factors, the result eventually showed that communication, power and goal have more supporting academic papers than the rest of the factors. Therefore, the authors consider these three factors as the most fundamental factors for this research. The collection of the first 50 academic papers of each factor is attached in appendix 8.

12

3. Research Methodology

This part of the thesis reflects the research question and the research aim, which is to investigate the cross-sector collaboration processes among organizations, government, and society. This chapter presents the strategies chosen by the authors and the arguments for the choices made. To answer the research aims and objectives (see section 1.3 ), the chosen research approaches, method of analysis, selection of the framework, sectors, and factors, as well as data collection methods (semi-structured interviews) will be justified. For analytical usage, the data is typically converted into written text.

3.1. Epistemology and ontology

Several studies concluded that epistemology is focused on understanding the truth of social reality and what defines valid, reasonable, accurate and legitimate information (Blaikie, 2003; Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2007). In addition, some studies argued that epistemology is defined as a concept that the researcher uses to intentionally or implicitly describe the process of gaining knowledge (Carter & Little, 2007; Pascale, 2010) through the same principles, procedures, and ethos as the natural science (Bryman & Bell, 2015).

Concerning the epistemology paradigm, a study by May (2011) concluded that there are four main paradigms in which knowledge is derived: positivism, interpretivism, realism, and pragmatism (Bryman and Bell, 2015). The first one to be explained is positivism. According to Bryman and Bell (2015), positivism is used by the natural sciences researchers in various contexts that contain deductive and inductive theory and connected more to quantitative analysis (Bryman, 2009; Creswell, 2009). The base of positivism in testing or developing hypotheses on data collection to draw conclusions (Bryman and Bell 2015). Next, interpretivism is the opposite of positivism, which is concerned with the social sciences rather than natural sciences (Bryman and Bell, 2015). From this context, interpretivism is associated with qualitative research (Bryman, 2009; Creswell, 2009). This paradigm involves the perception of human behavior and their different interpretation of reality. According to findings, the existing awareness is focused on personal interpretation (Bryman and Bell, 2015). In terms of knowledge creation in a scientific approach, realism is identical to positivism, where objects exist in the human mind (Saunders, Lewis, and Thornhill, 2009). At last, a study by Tashakkori and Teddie (2003) claimed pragmatism is the best paradigm for mixed methods because it takes into account multiple perspectives to gain knowledge (Creswell, 2009). Based on the explanation of the paradigm above, interpretivism is considered to be used because it is associated with qualitative research, which is chosen as a research approach of this thesis. In addition, the researchers gained the data by interviewing ten different organizations and interpreting the interview result to get the conclusion, which is in line with interpretivism.

The next to be explained is the ontological perspective. A study by Bellamy and 6 (2012) mentioned that ontology is a philosophical term that deals with the hypotheses regarding the reality, what exists, the value assigned to it, and what makes things happen or function. This approach argues that the truth does not arise on its own, but is created in social experiences by people and their interpretation of reality in social interaction (6 & Bellamy, 2012; Blaikie, 2003; Silverman, 2015; Walliman, 2006).

In this research, there are three ontological paradigms discussed since they provide valid knowledge: subjectivism, objectivism, and constructionism (Saunders et al., 2009; Bryman and Bell, 2015). Constructionism reflects society's significance and phenomenon that is perceived by social actors (Bryman and Bell, 2015). In addition, constructionism is an adaptive process that organizes an individual's experimental world (Mayer, 1992). Next, objectivism is the view that social entities exist without the control of social actors. It has the dominance of quantitative research methods (Carter and Little, 2007). The last one is subjectivism, which refers to the social actor's expectations and behavior (Saunders et al., 2009). The authors can maintain the subjectivity and transparency in qualitative research by having access to the participants' real views, behaviors, values, and knowledge (Carter and Little, 2007). To conclude, according to this research's aims and objectives (see section 1.3), it can be argued that this research adopts both subjectivism and constructivism. In addition, these two perspectives refer to qualitative research, social

13 actors' perspective, social phenomenon, real views, and values from the participant, which become the focus of this research

3.2. Research method

This chapter outlines the investigative steps taken to examine the cross-sector collaboration processes among organizations. To address the research questions, it needs to be clear how and why each question was investigated.

3.2.1. A qualitative research approach

According to Auerbach and Silverstein (2003), qualitative research involves analyzing and evaluating texts and interviews to uncover substantive phenomena and characteristics of a specific phenomenon. In other words, the research employs words to describe the phenomenon (Cresswell, 2014). Furthermore, Silverman (2015) argued that qualitative research has an explorative aspect of creating a more in-depth insight into phenomena contexts. This approach consists of observation, interviews, focused groups, analyses of documents, diaries, and other immeasurable data. Qualitative approach is beneficial to collect descriptive information about a topic in terms of expectations, emotions, and motivations (Silverman, 2015).

Furthermore, Silverman (2015) mentioned that qualitative research requires a descriptive explanation of the phenomenon in real life with their capacity to investigate realities that literally cannot be identified elsewhere. One of the key attributes of qualitative research is that the sequences ('how') and practices ('what') can be extracted by using naturally occurring data (Silverman, 2015). These key aspects (how and what) align with the established research question (see figure 5). For all those reasons, the authors thought a qualitative approach for this research was more appropriate. The authors believe the qualitative approach will be a guide in understanding the processes involved in cross-sector collaboration. Furthermore, this approach will enable the authors to take into account frequently described factors, such as communication, distribution of power, and aligning shared goals, which can affect the success or failure of the cross-sector collaboration phenomena.

Figure 5 The qualitative research phenomenon (Silverman, 2015).

3.2.2. Selection of qualitative research approach

In regards to deciding what type of research approach to use, based on the research questions, it needs more people's perception, views, ideas, and interpretation, which aligns more to qualitative research approach. Besides, based on the aims and objectives of the research to investigate how collaboration works among entities and their success and failure factors, this research needs more word expression (Cresswell, 2014) to investigate people’s behavior, responses, and experiences in cross-sector collaboration. In addition, since there will be an interview and dialogue between the authors and the interviewees, qualitative research is used in this research because of the focus on people's experiences, witnessing, thoughts, or feelings by drawing inspiration from humanistic phenomenology and conversations (Landøy, 2017). Moreover, due to the limitation of understanding quantitative software, a qualitative research method is chosen for this research. Furthermore, collecting data from a far distance between Sweden and Indonesia makes the qualitative (interview) process efficiently applicable to obtaining data from the organizations. Lastly, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and time limitation, this thesis avoided using double methods. In conclusion, because the research topic is related to human resource (HR) topics, it is much better to have face-to-face

14 interviews to get the most data and information. That is why a qualitative approach is the best choice for this research.

3.2.3. Content Analysis

According to Silverman (2015), it is crucial to find correlations in diverse data sets and analyze them systematically. The steps used in this research analysis included memo writing of the data and initial coding. These steps enable researchers to answer research questions and make conclusions (Silverman, 2015). Besides that, this data was also followed by a content analysis from different interviews. Several studies claimed that content analysis is a tool for evaluating verbal, visual, or written communications (Cole, 1988). It was first used for magazines, hymns, newspapers, political speeches, articles, advertisements analysis in the 19th century (Harwood & Garry 2003). Other studies claim that content analysis has a lengthy history of usage in communication, psychology, journalism, sociology, and business. Its use has seen steady growth over the last few decades (Neundorf 2002).

In order to analyze the content, Marshall (1996) argues that it is necessary to keep in mind the research questions to select the appropriate data. If there is so much data to evaluate, then the sampling method is the key. The most common sampling method is selecting the data randomly to ensure that the analysis remains relevant to the research questions (Marshall, 1996).

In this research, as suggested by Rowley (2012), the interviews were analyzed based on the key elements: organizing the data set, familiarizing with the data, classifying, coding and data interpretation, and presenting and writing the data. The interviews were recorded and transcribed, and after transcription, some of the transcripts in the Indonesian language were translated into English

Based on the step-by-step plan of Baarda and Goede (2005), the method of analyzing the research questions was carried out. To minimize the error, the researchers checked the transcription properly. The data analysis started with organizing the compilation of the transcribed interviews, scanned for repeated words, phrases, incorrect spellings, context misunderstandings, and errors in pronunciation.

To familiarize the interviews' data, the authors read the data carefully, annotate specific emerging trends, take note separately, and highlight the key texts. This phase was critical for setting the direction of data analysis (Rowley, 2012). The next step was the classification, coding, and interpretation of the data, which involved arranging the data, determining themes and coding the texts according to the topics. The identified topic relied on the cross-sector collaboration framework stated in Chapter 2, and the data were encrypted and classified accordingly. Lastly, the excerpts from the analysis were extensively read, and the key concepts that emerged were presented, including the linkages discovered concerning the theoretical framework.

3.3. Selection of the framework

A study reported by Bryson et al. (2015) concluded that some major frameworks had been developed for interpreting cross-sector collaboration for the last ten years. Some of them were developed by Bryson, Crosby, and Stone (2006); Thomson and Perry (2006); Ansell and Gash (2008); Agranoff (2007); Provan and Kenis (2008); Emerson, Nabatchi, and Balogh (2011), and Koschmann, Kuhn, and Pfarrer (2012). The comparison of what each of these frameworks emphasizes can be seen from Table 3 below.

Table 3. Comparison of major cross-sector collaboration-related theoretical frameworks (Bryson, Crosby & Stone, 2015).

Major cross-sector collaboration theoretical frameworks

Particular emphases

Bryson, Crosby, and Stone (2006) Cross-sector collaboration, institutional logics, planning, contingencies, power and the importance of remedying power imbalances, the need for alignment across components

15

Thomson and Perry (2006) Learning, organizational autonomy, leadership, administration Ansell and Gash (2008) Face-to-face dialogue, incentives and disincentives, the importance

of remedying power imbalances

Agranoff (2007, 2012) Leadership through a whole range of roles, processes, and structures, public value, capacity building, and learning

Provan and Kenis (2008) Governance structures

Emerson, Nabatchi, and Balogh (2011) Collaborative regimes, what makes collaborations work, capacity building, pulling out collaborative actions from overall impact/ outcomes

Koschmann, Kuhn, and Pfarrer (2012) Authoritative texts and their effects on activities and partners

Based on the table above, Bryson et al.’s (2015) framework concluded that the concepts of collaboration developed by the scholars are diverse. Still, they are mainly consistent by putting more focus on inter-organizational collaborations. However, after analyzing different cross-sector collaboration frameworks above, the authors decided to use the Bryson framework for several reasons. The first reason is that Bryson et al.’s (2015) framework has been developed by reviewing major cross-sector collaboration frameworks above and coming up with updated framework, aspects and factors (Bryson et al., 2015). In addition, Bryson et al.’s (2015) framework emerged by investigating 196 articles and three books to emphasize on using specific keywords such as cross-sector collaboration, partnership, combinations, collaboration, accountability, outcomes, power, and antecedents. Furthermore, Bryson et al.'s (2015) framework provides a significant review of empirical studies from 2007-2015 on cross-sector collaboration with the time covering more than a decade (Bryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2015).

Moreover, as can be seen from Table 3 above, Bryson et al.’s (2015) framework particularly focuses on cross-sector collaboration compared to the rest of the framework, which strongly relates to this research's focus. The next reason is that Bryson et al.’s (2015) framework particularly emphasizes the power and power imbalance in their focus compared to the rest of the framework (Bryson et al., 2015). This power and power imbalance becomes the focus of our selected factors, which will be explained further in choosing the collaboration factors section. In addition, this framework also emphasizes the importance of leadership roles, which become one of the collaboration factors the researchers investigate in this research as well. At last, Bryson et al.’s (2015) framework is chosen rather than the initial one (Bryson et al., 2006) because it is a revised version that provides the latest theoretical and empirical research over a decade (Kapur & Steuerwald, 2019). All these reasons make the authors consider Bryson et al.'s framework more updated and applicable to this research than the rest of the available major frameworks above.

3.4. Selection of collaboration sectors

Reflecting Bryson et al.’s (2015) framework, to tackle severe social problems and achieve beneficial community outcomes, the organizations need to understand that multiple sectors of a democratic society, such as business, nonprofits, philanthropies, media, community, and government, must collaborate to deal effectively and humanely with the challenges (Bryson et al., 2006). In line with this claim, (Kettle, 2015) argued that cross-sector collaboration among government, organizations, companies, and civil society had become a center of public management research (Kettl, 2015). Realizing that any organization or government cannot fix a social problem on its own or has a high risk of failing, certain researchers summarized that the collaboration with the community, private sector or NGOs would strengthen the window of opportunity, minimize the risk and provide appropriate solutions for creating cross-sector collaboration (Kettl, 2015 quoted by Bryson et al., 2015).

16 Concerning the Indonesian context, Edi (2014) claimed that the government, civil society, NGOs, and companies are the key players in collaboration. However, another study concluded that collaboration and organization learning were mostly conducted from the business viewpoint (Arya & Salk, 2006; Bennett et al., 2008; Murphy et al., 2012; Rathi et al., 2014). Therefore, since business viewpoint has been investigated more than other sectors, this might indicate that government, society, and socially-based organizations are under investigation. Therefore, the authors decided to choose government, society, and socially-driven organizations only for this research. Moreover, due to the time limitation and pandemic situation, the authors could not investigate the other sectors such as companies, media, and other international bodies. In conclusion, the author decided to choose and use three sectors (socially-driven organizations, government, and society) to examine cross-sector collaboration in Indonesian context. To support the reasons for choosing these three sectors, the explanation and benefits of each collaboration sector are explained as follows.

3.4.1. Socially-driven organization–socially-driven organization collaboration

According to the Alternative Board (2015), a socially-driven organization is built around positively contributing to society, oftentimes referring to non-profit organizations. After reviewing literature on socially-driven organizations, these types of organizations are also known as social enterprises but for the purpose of this thesis, they will be referred to as socially-driven organizations. In addition, Khan (2016) stated that socially-driven organizations have the power to play a crucial role in sustainability, more specifically social sustainability. Furthermore, a study by Shier and Handy (2016) argued that the role of socially-driven organization has become increasingly important in providing services and creating social change to better meet the emerging needs of service users and the general population. They also claimed that cross-sector collaborations among socially driven organizations enable these organizations to increase the likelihood of success in creating social value (for instance improved social outcomes) through social innovation by addressing the limitations of economic resources and political power. In addition, according to Simonin et al., (2016), nonprofits choose to work collaboratively for a wide range of reasons. For example, to boost organizational efficiency, increase organizational effectiveness, or drive broader social and systems change.

3.4.2. Socially-driven organization–government collaboration

As mentioned in the theoretical framework developed by Bryson, Crosby, and Stone (2006), the collaboration between the private sector and the government provides public value for the community. In this thesis, reference is made to both the local and central Indonesian government. The subjects of the study have either existing or pre-existing collaborations with either the local or central government of Indonesia. Providing public value through collaboration with the government has given the best outcome and extraordinary legal power, specialized expertise, and public service ethos (Bryson et al., 2006). In addition, Simo and Bies (2007) claimed that the private sector is stepping up to fill in the gaps in available services because of local, state, and federal administrative failures. Concerning this issue, for public managers, cross-sector collaborations allow governments to leverage funds, expertise, and risk-sharing with other sectors to provide critical ingredients to the successful delivery of public goods and services. Furthermore, for nonprofit managers, collaborations allow their organizations to meet their stated mission better and expand that mission to related areas of interest (Boyer, Forrer, & Kee, 2014).

Simo and Bies (2014) further argued that the challenges governmental entities face today have become more problematic, requiring multi-sector players and action. In the collaborative public management paradigm, government involvement is not only assumed but is extended to include public policy, management involvement, accountability, and performance expectations. Government policies and grant programs require or strongly suggest that public managers organize cross-sector collaborations to obtain public funds (Bryson et al., 2014).

The cross-sector collaboration framework highlights the importance of governance for networks or collaborations through structure and processes for collective rules and decision-making (Stone, Melissa, Barbara, Crosby, Bryson, 2010). In addition, a study by Cheng (2018) stated that these rules provide the

17 structure for the interactions of public and nonprofit partners, shaping the scope and incentives of participating partners. The rules will help these collaboratives establish a common language (Cheng, 2018). Through a common language and established rules, trust is established between participating partners. According to Bryson’s cross-sector collaboration framework, trust is often depicted as the essence of collaboration (Lee et al., 2012). In conclusion, the processes of trust-building, leadership building, and conflict resolution play essential roles in governing government-social-driven organization collaboration as it is considered a key to cross-sector collaboration (Bryson, Crosby & Stone, 2014).

3.4.3. Socially-driven organization – society collaboration

A study by White (1999) concluded that socially-driven organizations had been classified from the state and private sectors, meeting the interests of disadvantaged groups by collaborating with the communities and civil society in various ways. Jimenez and Zheng (2017) also suggested that these socially-driven organizations come in the form of ‘hubs’ made up incubators, entrepreneurship accelerators, and co-working spaces that provide a meeting place for the community, for knowledge sharing, collaboration, mentorship, linkages, and networks. Their statement also aligns with Bryson et al. (2015) 's framework that the cross-sector collaboration will strengthen windows of opportunity. For the purpose of this thesis, the local community citizens, made up of recipients of the public service, volunteers, members,alumni and beneficiaries of the socially-driven organization’s services, will be referred to as the society.

In this research, the word "society" means individuals who are external stakeholders of the socially-driven organizations, such as students, teachers, volunteers, farmers, villagers, etc. As societal needs become more pressing, this presents a social and economic opportunity for organizations to provide high quality services through social innovation (Hubert, 2010). At the heart of social innovation lie the society. With Indonesia being the third-most populous democracy, the society is still experiencing challenges such as poverty, unemployment, inadequate access to education, and unequal resource distribution (Kaasch & Sumarto, 2018). Cross-sector collaboration with society is important because it can foster the design of people-centered social innovation, that is, designing services fit for the Indonesian context. By exploring their perception of dealing with socially-driven organizations, it will be beneficial for the authors to identify the perception and experience of dealing with cross-sectoral collaboration in Indonesia.

3.5. Selection of collaboration factors

Different factors can affect cross-sector collaboration success or failure as collaborating partners bring in various resources, capabilities, knowledge, and skills. As previously mentioned, Bryson et al. (2015) identified five categories that include a set of 26 factors that affect the success of cross-sector collaboration, which include the following mediating factors; processes, structure and governance, constraints, outcomes, and accountabilities. However, due to time limitations, the researchers only focus on the three most fundamental factors for collaboration.

As mentioned in appendix 8 on fundamental factors on collaboration, the result showed that communication, power, and shared goal have more academic papers for the first 50 papers of each 26 factors. Besides, to know the papers' contribution towards cross-sector collaborations, the abstracts and the conclusion of the papers are investigated to know what contribution they offer towards cross-sector collaboration. Using this result, the researchers selected communication, power, and shared goal as a basis for framing the discussion of cross-sector collaboration in Indonesia. The explanation on each factor is explained in chapter 3.5.1-3.5.3 below.

3.5.1. Communication

The reason for choosing communication as the first factor in collaboration is explained in the following points. Firstly, some studies suggest that communication has been named as an interim variable that helps successful collaborations (Noorderhaven, Koen & Beugelsdijk, 2002). Secondly, communication is something that all researchers seem to agree on as one of the bases of collaboration (McCallum & Austin,