Combining mobility demand

and climate protection in

urban transport systems

Obstacles and constraints

in the case of Berlin

Inga Stumpp

Urban Studies: Master's (Two-Year) Thesis

30 credit points

Submitted in spring semester 2018

Supervisor: Peter Parker

IN URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEMS

OBSTACLES AND CONSTRAINTS IN THE CASE OF BERLIN

MALMÖ UNIVERSITY

FACULTY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY

Urban Studies: Master's (Two-Year) Thesis

Supervisor: Peter Parker

Submitted by Inga Stumpp

Spring Semester 2018

Transportation is an essential part of city life. However the extensive use of private cars in urban transport systems leads not only to a decrease in public health and quality of life but also drives global warming through the emission of GHG. The growth rate of CO2 emissions caused by transportation is among the highest across all energy sectors. In order to mitigate climate change, it is therefore crucial to reverse this trend and change urban transport systems towards more climate compatibility. Thus, this thesis investigates if and how mobility demand and climate protection can be combined in urban transport systems.

To answer these questions, the thesis discusses characteristics of climate-friendly transportation based on findings from academic literature. Moreover, policy instruments to transform urban transportation towards climate compatibility as well as possible obstacles and constraints in this regard are investigated. More precisely, socio-technical/infrastructural, technological, financial, legal, institutional/organisational, political, habitual, and cultural constraints are described and the significance of pragmatic, moral, and cognitive legitimacy is ascertained with regard to public and political acceptance of policies.

Drawing on these theoretical assumptions, the case of Berlin is analysed in more detail. Based on policy documents, statistical data, expert interviews, and a public hearing in the Senate of Berlin, it is investigated how the city plans to make its transport system more climate-friendly and what the actual state of climate compatibility within the transport sector is at the moment. As a result, it could be observed that policies for climate-friendly transport are in place and mostly implemented but that the amount of CO2 emissions caused by the transport system and especially by road traffic has more or less stagnated since the 1990s. Several reasons for this development could be ascertained: The transformation towards climate compatibility is, on the one hand, constrained by legal, infrastructural, institutional, political, habitual, and cultural factors as well as by the lack of personnel within the city administration, and, on the other hand, hampered by the perceived inacceptability of car-restrictive policies.

The conclusion from this thesis is therefore that it is thereotically possible to combine mobility demand and climate protection in urban transport systems and it is furthermore imperative in order to mitigate climate change and its dreaded impacts. In practical terms, however, cities face several intertwined and often very distinct obstacles and constraints that can only be overcome by long-term, dedicated, and citizen-oriented policy planning and implementation.

Key words: Berlin, climate compatibility, climate protection, climate-friendly transportation,

constraints, legitimacy, mobility demand, obstacles, political and public acceptance, public policies, urban transport systems

1. Introduction...1

2. Theoretical Assumptions on Climate-Friendly Transport...4

2.1. Climate-Neutrality and Sustainability...4

2.2. Transformation towards Climate-Friendly Transportation...5

2.3. Obstacles and Constraints...7

2.3.1. Path-dependency, Ineffectivity, and Lock-in...7

2.3.2. Acceptability and Legitimacy...10

3. Research Design...12

3.1. Case Selection: Particularities of Berlin...12

3.2. Methods Used: Document Analysis and Expert Interviews...13

3.3. Limitations of the Research Design...16

4. Analysis of Berlin’s Transport System and Policies...17

4.1. Allocation of Competences in the Transport Sector...17

4.2. Climate Goal and Transport Policies...18

4.3. Policy Implementation and Climate Compatibility...21

4.3.1. Investments and Infrastructure Development...22

4.3.2. Motorisation Quota, Modal Split, and CO2 Emissions...24

5. Interpretation of Interviews and Public Statements...28

5.1. Interviews with the City Administration...28

5.2. Interviews with the Transport Organisations...31

5.3. Public Hearing in the Senate of Berlin...34

6. Discussion and Conclusion...36

7. Bibliography...39

7.1. Policy Documents...39

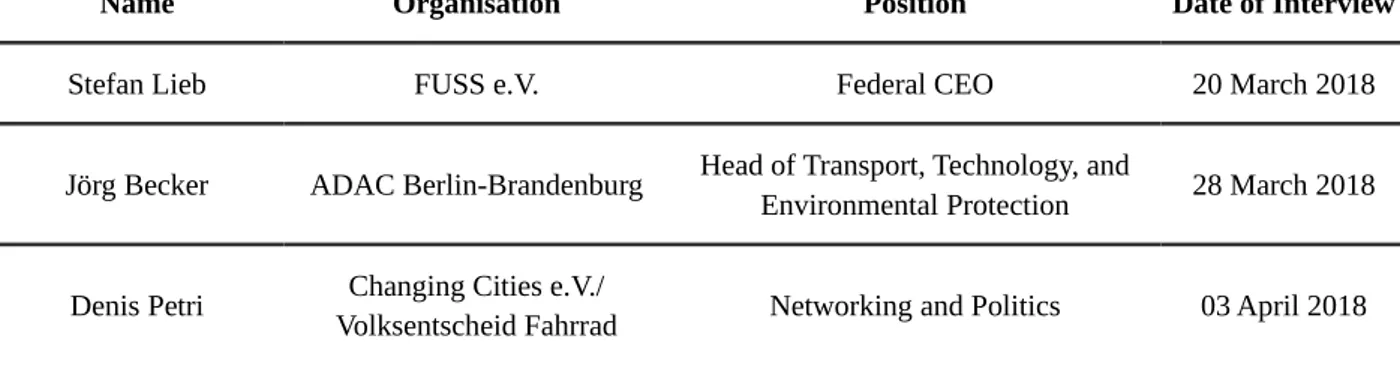

Table 1: Interviewees from the city administration...14

Table 2: Interviewees from transport organisations...15

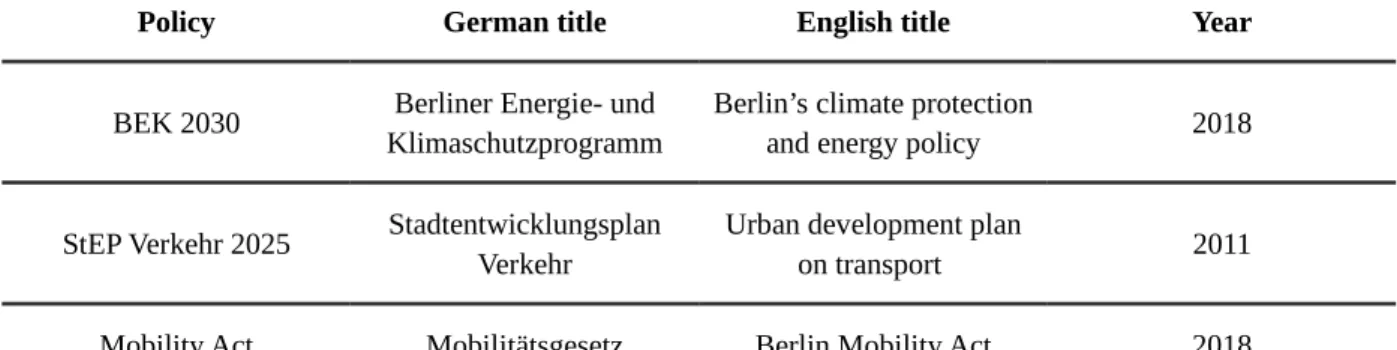

Table 3: Policies on climate-friendly transportation...18

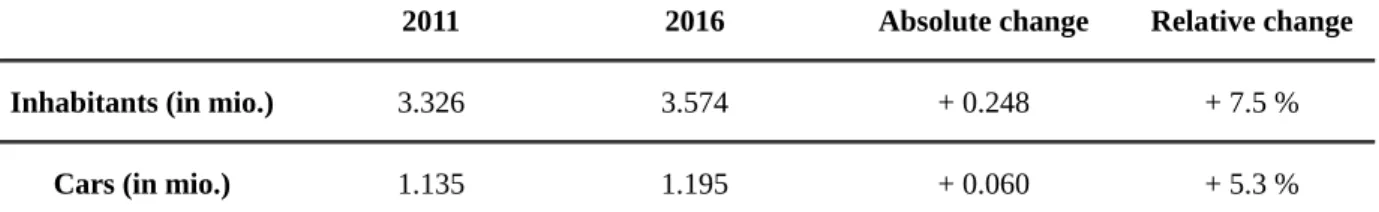

Table 4: Development of inhabitants and car ownership 2011-2016...24

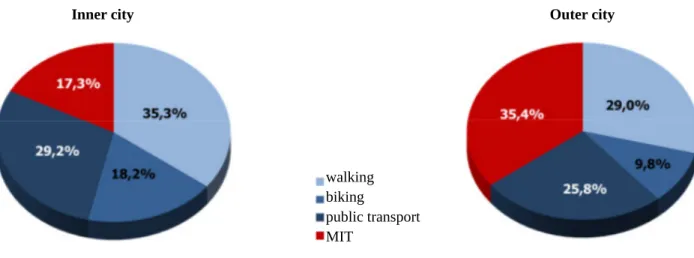

Table 5: Development of modal split 1998-2013...25

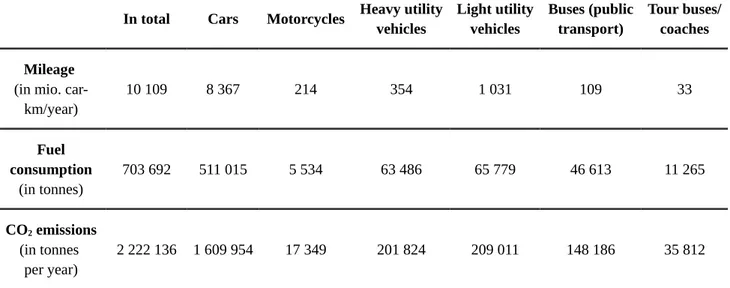

Table 6: Mileage, fuel consumption, and CO2 emissions on main roads in 2015...26

Table 7: Development of CO2 emissions 1990-2010...26

List of Figures

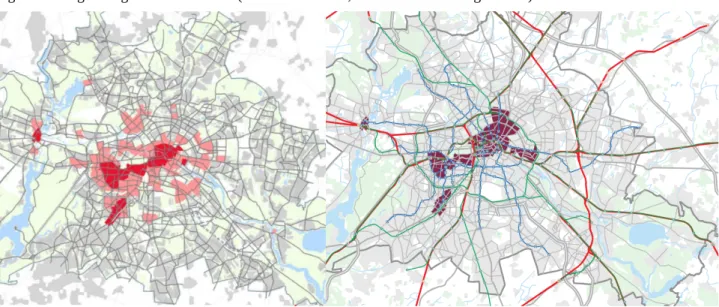

Fig. 1: Parking management 2004-2014...23ADAC Allgemeiner Deutscher Automobilclub organisation

ADFC Allgemeiner Deutscher Fahrrad-Club organisation

AZG Allgemeines Zuständigkeitsgesetz law/regulation

BEK Berliner Energie- und Klimaschutzprogramm policy

BkatV Bußgeldkatalog-Verordnung law/regulation

BVG Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe organisation

CDU Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands political party

CEO Chief Executive Officer title

CO2 carbon dioxide emission

Dr. Doktor (Ph.D.) title

FDP Freie Demokratische Partei political party

FUSS e.V. Fachverband Fußverkehr Deutschland organisation

GHG greenhouse gas(es) emission

km kilometre(s) measuring unit

km/h kilometres per hour measuring unit

mio. million measuring unit

MIT motorised individual transport(ation) transport

SenStadt Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung administration

SenUVK Senatsverwaltung für Umwelt, Verkehr und Klimaschutz administration

SPD Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands political party

StEP Stadtentwicklungsplan policy

StVG Straßenverkehrsgesetz law/regulation

StVO Straßenverkehrsordnung law/regulation

t tonnes measuring unit

VLB Verkehrslenkung Berlin administration

VwV-StVO Allgemeine Verwaltungsvorschrift zur Straßenverkehrs-Ordnung law/regulation

1. Introduction

Transport systems are at the core of city life. Urban infrastructures not only determine the physical layout of a city but also shape the social and economic possibilities of its citizens. The availability of means of transport and the degree of mobility offered by a city’s transport system influence all parts of life from grocery shopping to the way to work to free time activities. No matter which mode of transport is chosen – walking, biking, public transportation, or the private car – the urban infrastructure plays a huge role. Even though individual factors, such as moving home, changing job, or new family commitment, as well as car acquisition (Banister et al. 2007: 45), often figure into the selection of transport mode, the city’s characteristics act a part, too. Availability of public transportation, aesthetics of the route, and direct connections between points of interest are part of the decision-making on which form of transportation is chosen in the end. That is why, even though the choice of transportation stays a very individual and often highly emotional topic, design and ongoing development of transport systems are also important concerns for urban planners and policy-makers.

In the past, thoughts on the efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and also social equity of transport systems have been in focus when planning for new infrastructures or improving existent ones. During the last couple of decades, however, also environmental and climate concerns were recognised and tried to be included into transport policy and planning. Particularly the wide-spread usage of cars as most common form of motorised individual transport (MIT) has been identified as harmful due to the vast amount of land consumption needed for car infrastructure, the high risk for disastrous traffic accidents, and the environmentally damaging emission of noise, fine particulates, and greenhouse gases (GHG) (i.a. Rees 2003: 10). Although most of these drawbacks are usually just accepted as necessary evil in the exchange for ensuring mobility, more and more policies are discussed and issued that include these concerns and try to decrease the harmfulness and climate impact of transportation systems.

Consequently, many countries and also individual cities have set more or less ambitious climate goals by now in terms of private and public transportation. Nonetheless, the growth rate of GHG emissions in the transport sector are the highest among all the energy end-user sectors (IPCC 2007 as cited in Newman/Kenworthy 2015: 36). In this regard, cities’ responsibilities and opportunities have come into focus over the last two or three decades. Cities are by now home to over half the world’s population and are therefore the place where most traffic and transportation issues arise (Banister 2008: 73; Stopher/Stanley 2014: 2). Although most climate agreements are discussed on the international level, local governments and administrations are often the ones to implement the goals and are usually responsible for transport systems and the construction of (local) infrastructures. They can therefore influence the amount of GHG emissions caused by private and public transportation. Thus, cities play a major role in integrating climate protection into transport systems making the relation between urban transport and climate protection a highly relevant topic for the field of Urban Studies.

Indeed, the idea and concept of climate-friendly or even climate-neutral urban transport has become increasingly popular in research as well as politics. The amount of literature in academia and popular science on climate change and climate change mitigation is already quite

extensive and still growing fast although, in general, there is considerably more research on sustainability and sustainable transport than on explicitly climate-friendly or climate-neutral transportation. However, also the literature on the transformation of urban transport systems towards more climate-friendly modes and on barriers to these policies is increasing (cf. Banister 2008: 76). Nevertheless, a systematic and holistic perspective on why most cities fail in achieving this transformation is quite rare. Lots of articles analyse city-specific transportation projects instead focusing on how walking, biking, or public transport has been successfully promoted in certain areas (see e.g. Kronsell 2013; Rees 2003).

In contrast, some scholars do not engage in the concepts of climate compatibility or sustainability but concentrate more on how most European cities have evolved through different stages of transportation, that is from walking cities to transit cities on to automobile cities and how this development has ended so far in a high degree of car dependency, especially in North America (see e.g. Buehler/Pucher 2011: 61; Schiller et al. 2010: 46). Related to this, some researchers engage in the notion of the so-called car culture and how cars are perceived as more than just a vehicle for transportation (see e.g. Diekstra/Kroon 2003). Some studies engage in research on freight and economic transport (see e.g. Priemus et al. 2007), however, the focus here will lie on individual, non-commercial transport issues. This distinction is necessary as commercial and individual transport have very different characteristics and policies issued to transform them towards being more climate-friendly differ therefore substantially.

Although all these studies are important and also relevant for the topic of combining mobility and climate protection in cities, there is still a considerable research gap regarding systematic research on the actual transformation of existing urban transport systems and the obstacles and constraints that may be encountered (cf. e.g. Tolley 2003: xvi). Thus, so far, the question remains unsolved if and how climate protection can be integrated into urban transport systems. Therefore this thesis aims at understanding if and how mobility demand and climate protection can be combined in urban transport systems and, specifically, how the city of Berlin deals with this challenge.

The case of Berlin is quite a unique one regarding administrative set-up, history, size, and demographics. Furthermore, the city set itself a quite ambitious goal of becoming climate neutral by 2050 but fights with increasing CO2 emissions in the transport sector (cf. BEK 2018). Therefore, the gap between the city’s desire to become climate neutral and the actual development in its transport system will be interesting to investigate. The following research questions will be used in order to analyse how the city of Berlin deals with the issue of climate mitigation within the transport sector:

• How does the city of Berlin plan to reduce the CO2 emissions caused by urban transportation?

• How has the state of climate compatibility within the transport system in Berlin developed over time?

• Which obstacles and constraints does the city face regarding the transformation towards a climate-friendly transport system?

To answer these questions, characteristics of climate-friendly urban transport as well as theoretical assumptions on the transformation of urban transport systems towards climate-friendly ones are discussed in the following. Afterwards, the research design of this study will be explained consisting of the reasons for selecting Berlin as a case and choosing expert interviews and the analysis of policy documents as methods. Moreover, the limitations of the research design will be discussed. In the fourth chapter, the case of Berlin will be introduced further and its transport and climate protection policies will be presented. After that, the interviews and policy documents will be analysed and then discussed in reference to the theoretical explanations for a lack in climate-friendly transport systems. The last chapter will briefly summarise the findings, discuss how this study can contribute to the wider research field of climate-friendly transport systems and propose further approaches that could be interesting for future research.

2. Theoretical Assumptions on Climate-Friendly Transport

Rietveld and Stough (2007: 1) identify three main objectives for transport systems: they have to be efficient, equal, and sustainable in order to be considered well-functioning. While the free market systems common in Western countries serve the first objective, it is stated that the other two are often neglected and, therefore, have to be enforced through public policies (Rietveld/Stough 2007: 1). In order to analyse policies in that regard, first of all, it has to be understood what sustainable transport entails, how climate change plays a part in the concept, and how sustainable or climate-friendly transportation can be achieved.

2.1. Climate-Neutrality and Sustainability

Although the concepts of sustainable and climate-friendly or climate-neutral transport overlap, it is important to distinguish between the terms before any further analysis. While climate-neutrality aims solely at reducing the GHG emissions of transport modes in order to mitigate climate change, sustainable transport also entails the reduction of other harmful emissions such as noise, nitrogen dioxide, or fine particles. While the output from transport, that is for example the number of passengers or the accessibility of transport, is supposed to stay the same or increase, the input, that is the use of especially non-renewable resources, has to decrease (Banister et al. 2007: 17). In its broadest meaning, sustainable transport also includes the social and economic aspects of sustainability, for instance equal accessibility for everyone. This understanding of sustainability includes, among other things, also congestion costs, costs relating to accidents, and the consumption of space (Banister et al. 2007: 17).

Climate-neutral or climate-friendly transport is thus often sustainable but does not have to be. While the aforementioned dimensions of sustainability often coincide with instruments to achieve a climate-neutral transport system, they will not be in focus in the following discussion. Concentrating solely on climate mitigation in transport systems instead of on sustainable transportation in general, provides a necessary delimitation of the research and facilitates to assess the goals, measures, and outcomes of policies.

As mentioned above, climate-friendly transport focuses on the amount of GHG emissions and particularly CO2 emissions caused by modes of transportation and asks how these can be reduced in order to mitigate climate change. Therefore, generally, all non-motorised forms of transport can be considered climate-neutral, that is walking, cycling, and less common types of transportation such as skating. While walking is completely climate-neutral, bicycling is still one of the most climate-friendly modes of transport. Especially in comparison to automobiles, bicycles require fewer resources for their manufacture and operation and are altogether less polluting (Rees 2003: 17). Although the production of bikes is responsible for some CO2 emissions, its usage is completely emission-free and is therefore considered climate-neutral. Biking is considerably faster and therefore has a better range than walking which makes it easier to take it as a substitute for motorised forms of transport (cf. Rees 2003: 17).

Other kinds of transport emit GHG but are still considered climate-friendly such as public transportation, i.e. usually buses and trains, and forms of electromobility. However, especially in

the last case, other indirect causes of GHG emissions should be kept in mind that arise due to the production of the vehicles and the kind of energy used for operation. Electronic vehicles do not emit CO2 but if electricity is used that was captured through coal plants the overall statistics on

GHG emissions will not be better than with conventional cars. Therefore, it is supposed that in a climate-friendly transport system, biking and walking along with the public transport system have to be the most used forms of transport and any form of MIT the least (cf. Rees 2003: 11).

2.2. Transformation towards Climate-Friendly Transportation

Unfortunately for climate protection, reality looks different and MIT is often the dominant form of moving around in cities. Therefore, the question is how that status quo can be changed and climate considerations integrated into already existing transport systems without hampering with the level of mobility offered to the citizens. Neither in academia nor practice, there is much controversy about what has to be done in order to make an urban transport system more climate-friendly (cf. Banister 2008: 76): Overall, the need to travel as well as the lengths of trips have to reduced (transport demand management) and a modal shift from MIT to climate-friendly modes of transport encouraged (transport system management) (Banister 2008: 75). Transport demand management entails measures that aim at making cities more polycentric and at encouraging a change in work life to enable citizens to work from home. Even though these instruments have major impacts on the transport system, they usually do not fall under the decisional power of a city’s transport department but rather under the authority of city planning and social departments and will, hence, not be discussed in length. In contrast, transport system management is at the core of transport policies and planning. To make urban transportation more climate-friendly, transport system management has basically two options that can (and should) also be combined: to make climate-friendly modes more attractive for citizens (pull factors) and to make MIT less attractive (push factors) (cf. Banister 2008: 75). To improve transport technology is certainly a necessary step towards climate-neutrality, but will probably not be sufficient due to the tendency for increasing vehicle use (Newman/Kenworthy 2015: 58).

Measures that have to be taken to “pull” citizens to climate-friendly transport modes are to introduce bicycle tracks and separate lanes on roads for cyclists, to improve the infrastructure for pedestrians, and to provide fast, comfortable, and convenient public transit for longer trips (Diekstra/Kroon 2003: 262; Rees 2003: 13). Other instruments are traffic calming to increase safety for pedestrians and cyclists or to create tax incentives for businesses to install facilities for bicycles (e.g. daytime storage) and cyclists (e.g. accessible showers) (Kenworthy and Laube 1997, extended by and cited in Rees 2003: 14). Making climate-friendly forms of transportation more attractive also entails to make it easier to switch between the modes. It is therefore of utmost important to improve inter-modality, that is the ability to make connections between modes, for example through public transport vehicles capable of carrying bicycles, as well as multi-modality, that is the ability to choose among several modes of transport for a trip (Kenworthy and Laube 1997, extended by and cited in Rees 2003: 14; Rees 2003: 13; Schiller et al. 2010: 88).

It is, however, equally important to make the use of motorised vehicles less attractive and “push” people away from them. This can, for instance, be done by slowing down MIT through

speed reductions and speed ramps and an effective enforcement of existing speed limits (Banister 2008: 75; Diekstra/Kroon 2003: 262-263). To go one step further, specific streets or places such as the city centre can be converted to pedestrian and cycle use only (Diekstra/Kroon 2003: 262; Rees 2003: 13; Schiller et al. 2010: 237). Instead of building new highways or streets to reduce traffic congestions, research indicates that this actually leads to more instead of less traffic and is therefore “totally counterproductive to reducing transport energy use and their resulting carbon dioxide emissions” (Newman/Kenworthy 2015: 58; Schiller et al. 2010: 33). Conversely, the removal and reduction of streets and highways actually leads to less traffic and less congestion (Schiller et al. 2010: 33; 237).

Another possibility is to increase the costs associated with car usage through controlled road pricing and parking fees (Banister 2008: 75; Diekstra/Kroon 2003: 262; Rees 2003: 13). Schiller et al. (2010: 168) even state that parking “may be the single most important factor shaping the decision whether and when to drive to a destination or use an alternative mode for a trip – or whether to make the trip at all”. The availability and costs of parking are important in shaping urban transportation behaviour. In contrast, free, cheap, or plentiful parking will make trips by car more attractive and thus increase MIT (Schiller et al. 2010: 168). Moreover, having parking opportunities directly in front of houses or apartments facilitates car usage as “people just go from living room to ‘second living room’ taking the path of least resistance and greatest autonomy” (Diekstra/Kroon 2003: 263). Although any of these measures and instruments alone may have an effect on the desired outcome, research shows that positive policies towards public transport, pedestrians, and cycling work best in combination with economic constraints on the car (Rees 2003: 13). According to Rees (2003: 13), the overall objective should be to offer the citizens convenient and reliable alternatives to MIT while ensuring that the costs of car usage accurately reflect the true impact on the environment. This however requires both a thorough analysis of the status quo and also a vision of how a future city is supposed to look like and what role which modes of transport will play there (Banister 2008: 74).

Additionally, research shows that it is crucial to include citizens in the planning and implementation of transport policies: “Public acceptability drives political acceptability and perhaps the only way to progress the debate is to establish whether there is sufficient public support for change, as this is the main way to influence political thinking” (Banister et al. 2007: 33). Rees (2003: 13; Kenworthy and Laube 1997, extended by Rees 2003: 14) advises to engage concerned citizens’ organisations in favour of and against car usage and to develop an active campaign to publicise the personal, community and ecosystems health benefits of cycling and walking. Also Banister (2008: 75-76) and Monheim (2003: 85) recommend to involve the people in the processes of discussion, decision-making, and implementation to make them aware of the benefits to quality of life and transport efficiency and make them understand the rationale behind policies that may seem disadvantageous for them at first glance. Banister et al. (2007: 41-44) identify seven key principles how to increase the acceptability among citizens for a transformation in urban transport systems towards more climate-friendly modes:

Information: This includes conventional forms of information, education, awareness

campaigns, and prompting through media and social pressure. The need for a change to climate-friendly transport modes as well as the positive benefits of these modes are to be explained.

Involvement: All stakeholders are to be brought to the table and to be heard in order to gain

support and understanding for the transformation. Packaging: As mentioned above, push and pull policies are to be introduced jointly. Selling the benefits: Although many policies towards more climate-friendly transport systems will entail some forms of cost, inconvenience, and sacrifice to the users, they also provide benefits that should be emphasized and publicised.

Adopt controversial policies in stages: In order to build up acceptance and support for a policy

it has to be given time to experience positive outcomes and measurable improvements in the quality of life. Consistency and longer term perspectives: This involves for instance to follow the precautionary principle and to implement measures now even though their effects will only be seen in the long-term. Adaptability: In order to deal with the large degree of uncertainty when it comes to climate mitigation, the authors advise to rather make incremental changes and test several solutions in small-scale experiments if the impact of strong measures is hard to predict. Then, the adaptive behaviour of people and institutions can be assessed and policies adjusted.

However, although it is commonly accepted, at least in European countries, that transport and extensive car usage leads to climate change as well as a lower environmental quality in cities and the instruments for a change are explored, this knowledge has not led to more climate-friendly transport systems yet (Banister et al. 2007: 46).

2.3. Obstacles and Constraints

Transport systems and infrastructures are usually one of the oldest parts of a city whereas climate concerns came up relatively recent. Especially the rise of the car in the 1960s transformed European cities making them quite car-friendly and to some degree car-dependent leading to high emissions of CO2. Even though the instruments available are known, a change of transport systems towards climate-neutrality can be hence difficult to achieve. The following sub-chapters discuss this and further constraints found in the literature as well as the acceptability and legitimacy of transformation policies.

2.3.1. Path-dependency, Ineffectivity, and Lock-in

Although systematic research on constraints occurring in transforming an urban transport system towards climate compatibility is scarce, altogether eight categories could be derived from analysing academic literature, that is socio-technical/infrastructural, technological, financial, legal, institutional/organisational, political, habitual, and cultural constraints:

Socio-technical/infrastructural: From a practical point of view it seems plausible that there are

seldom great or sudden changes in a city’s transport policies as they are heavily dependent on large infrastructures (socio-technical systems) that can only be altered in long and costly processes (cf. van Vliet 2011 as cited in Corvellec et al. 2013: 32). Infrastructures have a long lifespan which means that any change made to them usually lasts for decades and is difficult to reverse (Birch 2016: 192). Infrastructures thus can create physical limits that also restrain social capacities to develop or choose more climate-friendly pathways (Birch 2016: 192).

Technological: Similarly, technologies can also lead to lock-ins. In the past, the concept of

technological lock-in has been used to explain, for example, the persistence of fossil-fuel-based technologies despite their well-known environmental externalities contributing to climate change (Klitkou et al. 2015: 22). Lock-ins can arise due to the fact that incumbent technologies have an advantage over innovations because of their wide-spread diffusion making them usually cheaper to produce (Sandén/Azar 2005 as cited in Klitkou et al. 2015: 22). Moreover, their advantages and disadvantages are already known to users while the introduction of a new technology is more uncertain (Sandén/Azar 2005 as cited in Klitkou et al. 2015: 22).

Financial: Financial or resource constraints are, on the one hand, self-explanatory and, on the

other hand, quite common. To execute a policy or measure monetary resources are needed in time and in the right amount otherwise the implementation may be delayed or even made impossible (Banister 2005: 55).

Legal: Another barrier towards a more climate-friendly transport system can arise due to

national or international treaties, directives, laws, or regulations (Banister 2005: 55; Rietveld/Stough 2007: 6). Many (innovative) transport policies or measures need adjustments of regulations which can be troublesome, particularly when these measures are outside the realm of transport or not supported by the responsible policy-makers (Banister 2005: 55-56). Local or regional governments may be unable to affect transport policies that are set by a higher level of government or vice versa (Rietveld/Stough 2007: 6).

Institutional/organisational: Institutional or organisational barriers can be responsible for the

gap between governmental intentions and actual outcome: slow procedures and responses, lack of incentives for innovation, and rent seeking are only some of the reasons for a lack in change towards climate-friendly transport (Rietveld/Stough 2007: 1). Other short-comings can be caused by a lack of cooperation or even conflicts between departments within the same governmental body (Banister 2005: 55; Rietveld/Stough 2007: 1): “A large number of public and private bodies are involved in transport provision and this means that it is often difficult to achieve coordinated action by the implementing agency” (Banister 2005: 55-56).

Political: Related to institutional or organisational constraints, there may arise conflict between

political parties, interest groups, and agencies about what the best policies in the transport sector will be (Rietveld/Stough 2007: 6). Certain interest groups may oppose the introduction of strict environmental standards in particular transport sectors and governments and administrations can find it therefore difficult to achieve a balance between different stakeholders affected by the policies (Rietveld/Stough 2007: 1; 6). As with many environmental problems, there are many small-scale winners that would profit from a change in the transport system, that is the society as a whole and future generations, and relatively few but well-organised large-scale losers such as the car industry (Rietveld/Stough 2007: 5): “The losers usually know how to organize themselves effectively and exercise more pressure on the government in its roles as legislator and regulator than the winners. This considerably hampers solutions, including innovations in technology, organizations and institutions” (Rietveld/Stough 2007: 5). Another difficulty in dealing with climate issues is that climate change is a long-term issue with nearly no short-term rewards. In contrast, time horizons of private companies, individual citizens and voters, or

governments are usually rather short (Rietveld/Stough 2007: 6). Therefore, policies may not be considered expedient or necessary yet.

Habitual: Habitual barriers towards a climate-friendly transport policy can arise when policies

or measures are implemented but citizens do not change their behaviour accordingly. Naturally, people feel nervous or reluctant about radical changes in their everyday life and do not always act in a rational way (Banister et al. 2007: 36; 39). Recent research suggests that even if citizens have complete knowledge of the alternatives, they still make choices in a historical context meaning that a transport choice once made and repeated over time is chosen once more instead of trying a new mode (Matthies/Klöckner 2015: 491-492). As Matthies and Klöckner (2015: 492) state, most people have long histories of using one form of transport leading to relatively stable use patterns of particular modes for particular trips. They state moreover that “[t]hese stable patterns are resistant to change to a degree that makes it difficult to influence travel behaviour by simply improving the quality of public transportation or changing peoples’ attitudes or norms about the use of alternative travel modes” (Matthies/Klöckner 2015: 492). As long as the situational cues do not change in a way that would make the preferred mode unattractive, travel behaviour will stay the same (Matthies/Klöckner 2015: 492).

Cultural: Another factor playing into climate-friendly transformations of urban transport

systems is the so-called car culture (cf. Schiller et al. 2010: 31). Cars are not only faster and often more convenient and more comfortable than alternative transport modes but they have also become a status symbol representing their owners’ personalities, wealth, and social status (Rees 2003: 13). Diekstra and Kroon (2003: 257) state that the individual freedom offered by the car is not only a by-product but the principal motive for car ownership and use. By using the car, the driver feels more powerful as he or she claims territory through the physical impacts of driving and/or parking (Diekstra/Kroon 2003: 257). The car, moreover, is often considered a second living room and can be a physical expression of one’s own personality (Diekstra/Kroon 2003: 257). Additionally, cars themselves are often assigned personalities that also spill over to the owner (Diekstra/Kroon 2003: 259). Many car owners treat their vehicle as it would actually be alive, talk to it, thank it, curse it, or caress it, and sometimes even feel guilty for not spending enough time with it (Diekstra/Kroon 2003: 260). Several reasons for this development are discussed in literature ranging from the history of car ownership – only the wealthy upper classes could afford a car – to the glorification of cars in modern pop culture and advertisement to a car-focused travel-mode socialisation from early childhood days onwards (Diekstra/Kroon 2003: 254; Matthies/Klöckner 2015: 494; Schiller et al. 2010: 31). Whatever its roots, it nevertheless leads to the fact that cars are chosen over other modes of transportation although the latter may be faster and/or more cost-efficient for certain trips.

Generally, these constraints are caused by past policy decisions and depend on economic, social, geographical, historical, and cultural preconditions (Parsons 1995: 207). These can lead to the path-dependency of policies, an only incremental policy-making process, or even a total lock-in of the status quo (Parsons 1995: 231; Corvellec et al. 2013: 37).

2.3.2. Acceptability and Legitimacy

Apart from the influence of past decisions and framework conditions, transformative policies can also be constrained by the justification and public understanding of why a change in urban transportation is needed. As mentioned above, it is crucial for a policy to be accepted by the public in order to truly lead to a transformation of the urban transport system. If not perceived as acceptable or legitimate, policies or even policy attempts may be demonstrated and protested against by the public or not even issued in the first place as the politicians fear the outrage of citizens (cf. Wallner 2008: 422). Although literature on legitimacy of policies is scarce, Suchman (1995) developed a concept of legitimacy of organisations that can be applied: legitimacy is a generalised perception or assumption that a policy is desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions (cf. Suchman 1995: 574).

Suchman (1995: 577) distinguishes between three types of legitimacy that is pragmatic, moral, and cognitive legitimacy. Pragmatic legitimacy occurs when an organisation’s audience or constituency deems the action of this organisation beneficial (Suchman 1995: 578). Transferred to legitimacy of policies this would mean that a policy is seen as legitimate when it is advantageous to the people affected by it. Therefore, Banister et al. (2007: 35) propose to demonstrate to the people that climate-friendly transport improves individual and collective public health and is hence beneficial to them. Moreover, they state that the policies have to be perceived as fair to individual travellers and to the society as a whole as people fear to be put at a disadvantage (Banister et al. 2007: 34). That is why pull measures are often easier accepted than push measures as they offer advantages to the people (Banister 2005: 55; Enoch 2005: 100). Contrarily, push measures are perceived as a decrease in personal freedom associated with owning and using a car and thus perceived unacceptable (Banister 2005: 55; Enoch 2005: 100). The second type of legitimacy developed by Suchman (1995: 579) is called moral legitimacy. In short, actions are considered legitimate because they are seen as the right thing to do at the moment. The public as well as the politicians have to perceive that there is a problem and that the policy seems a reasonable way of solving it (Enoch 2005: 100). Parsons states that policies are developed according to the identification and framing of certain issues (Parsons 1995: 87). What decision-makers recognise as problem that needs solving determines what kind of policy will be developed (ibid.). A state of affairs or condition is framed as a problem when it affects and threatens a group creating a sense of urgency to act in this respect (cf. Parsons 1995: 87). Also Banister et al. (2007: 34) underline the necessity that the public sees climate-friendly transport as being of sufficient importance for a change in transport systems. The need for changes in behaviour and the importance of climate-friendly transport has to be made clear to the citizens, interest groups, and generally the society (Banister et al. 2007: 39-40). If the policy implemented is in response to a crisis that is beyond the government’s control, people are usually even more willing to make personal sacrifices for it (Enoch 2005: 100). Conversely, if climate change is not considered a crisis or even an issue, policies towards climate-neutrality are neither perceived the right thing to do nor necessary. Rees (2003: 13) criticises that, so far, “scientists, urban planners and politicians have failed both to convey a sense of urgency about the problem and to create a compelling vision of the sustainable city”.

The third main type of legitimacy is coined cognitive legitimacy (Suchman 1995: 582). This type legitimacy rests either on a taken-for-grantedness or on comprehensibility (Suchman 1995: 582). To be comprehensible, the actions of an organisation or in this case a policy must be reasonable to the audience and fit into their belief systems as well as into their understanding of everyday life (Suchman 1995: 582). In the case of climate change and climate mitigation there is however a large degree of uncertainty among citizens and policy-makers. In order to be considered legitimate and acceptable, a policy must however be seen as effective and efficient in achieving the desired outcomes (Banister et al. 2007: 34; Enoch 2005: 100). It is helpful in this regard if the policy is not too different from existing policies or if citizens have had experience with a similar policy (Enoch 2005: 100). If citizens do not understand why or how a policy is supposed to work, it will be deemed unacceptable. In this respect, it is essential to clarify and illustrate the connection between car usage, transport policies, and climate change as well as its effects in an easily understandable manner.

Taken-for-grantedness goes one step further and assumes that an action or policy is considered legitimate as there seems to be no other options available (Suchman 1995: 583). Alternatives are impossible and therefore the one executed option has to be the right on (Enoch 2005: 100; Suchman 1995: 583). However, in regard to climate change, technological progress in MIT are often considered viable alternatives so that a switch towards public transport, walking, or cycling in urban transport systems is not necessary. In sum, to be considered acceptable and legitimate, a policy must be understandable and considered effective as well as be perceived either as beneficial or necessary. If the issue targeted by the policy is moreover perceived a crisis and therefore urgent, people are willing to also accept personally disadvantageous measures to solve it.

Overall, this discussion of theoretical concepts and state of research shows that the transformation of urban transport relies on a combination of push and pull factors and public participation. It moreover displays that despite this knowledge, there are many constraints that prevent or limit the transformation of an urban transport system towards climate-neutrality. There are, on the one hand, factors such as technology, infrastructure, habits, and culture, that can lead to a path-dependency of policies or even a lock-in of the status quo, and, on the other hand, there are constraints in respect of the framing and perception of issues that can lead to the inacceptability of policies. Thus, even if a city knows how to transform its transport system to be climate-friendly, it may consciously or unconsciously refrain from doing so.

3. Research Design

Before the case of Berlin will be described and analysed in reference to these theoretical assumptions on urban transport systems, this chapter elaborates on the selection of Berlin as case study, the methods used, and the limitations of this research.

3.1. Case Selection: Particularities of Berlin

Berlin was selected as case due to its uniqueness that make an in-depth and qualitative empirical study expedient. For a start, Berlin is not only the capital city of Germany but also one of its 16 federal states bestowing regional competences on the city administration making it an interesting case from a public policy point of view. Moreover, the city is of particular interest as the possibilities to achieve a climate-friendly transport policy seem to be very favourable compared to other cities, making it an extreme case in these premises. For a start, transport, climate mitigation, and environment are dealt with by the same ministry, that is the

Senatsverwaltung für Umwelt, Verkehr und Klimaschutz (SenUVK). The current local

government which has been elected in 2016 consists of the socialist (SPD), the leftist (die

Linke), and the green (die Grünen) parties. These parties are generally more aware of

environmental issues than the conservative party (CDU) or the Liberals (FDP) and especially the green party advocates climate protection measures. The senator responsible for the environment, transport, and climate protection is Regine Günther who does not belong to any political party but who worked with climate and energy issues before within the environmental foundation

World Wide Fund For Nature (WWF). Thus, ambitious climate goals and measures can be

expected from the political and administrative side. Besides, the existence of climate change and the need to decrease GHG emissions are generally accepted in Germany and regional or local climate mitigation efforts are backed up by the national government and its rather ambitious climate goals (cf. BMU 2016; UBA 2018). Berlin itself set the goal of becoming climate neutral by 2050. Furthermore, the city has an already quite well established public transport system (BVG) and the flatness of the surroundings facilitate walking and biking. Its car ownership rate is one of the lowest in Germany and the city has already introduced a low-emission zone in the inner city in 2008. Moreover, the city is constructed in a polycentric manner making long-distance travels to the city centre often unnecessary. Thus, the city has rather good preconditions to become climate neutral by 2050 making it even more surprising that its transport-induced CO2 emissions are on the rise.

Due to Berlin’s particular features, a single case study was chosen instead of a comparative study in order to answer the research questions. Additionally to being quite unique regarding the political status as city and federal state, the city has also a very singular history. Having been divided into two parts that have been ruled by quite different political and economic systems for decades, comparisons with other cities inside or outside of Germany are generally difficult. Urban development and particularly the transport sector were preoccupied with unifying the city and the city’s infrastructures for years after the reunification in 1990 neglecting other, seemingly less urgent topics such as climate protection. Additionally, Berlin is with 3.57 million inhabitants the largest city in Germany with a current growth in population. Administrative set-up, history, size, and demographics add up to a quite unique city development where a single case study is

thought to be more rewarding than a comparison with cities that face very different challenges and opportunities. Nonetheless, an in-depth analysis of Berlin’s climate and transport policies is likely to reveal impediments to climate-friendly transport policies in general. Examining Berlin as a single case allows for an extensive and detailed evaluation of the case possibly leading to findings that could later on be applied and considered in other cases as well. As one manifestation of the wider issue of climate mitigation in transport policies, this case study can thus contribute to the research on public policies dealing with climate mitigation in the transport. sector

3.2. Methods Used: Document Analysis and Expert Interviews

In order to get a good grasp of the current and past development of climate mitigation in the transport sector in Berlin, expert interviews were conducted in addition to the analysis of academic literature and policy documents. As a type of semi-structured interviews, expert interviews are conducted with a person who is expected to have extensive and particular knowledge on a specific field of activity, in this case on the climate and transport policies in Berlin (Flick 2009: 165). Expert interviews can help to reveal considerations and processes leading to certain policies as well as shed light on who the actual stakeholders and decision-makers are. Thus, they are particularly useful in dealing with single case studies where the objective is to get as much in-depth insider knowledge as possible (cf. Kaiser 2014: 4). Expert interviews furthermore offer the possibility of looking at the issue under study from different angles and can therefore be used to complement other methods, for instance, the analysis of policy documents (Flick 2009: 168).

Usually, expert interviews are conducted in a semi-structured way using an interview guideline that steers the interview towards the expertise of interest and exclude unproductive topics (Flick 2009: 167; Kaiser 2014: 5). Using a guideline instead of a standardised set of questions offers the advantage of allowing for unexpected answers and new insights into the topic (Kaiser 2014: 8). Therefore, it is important that the questions posed are open but it should be observed that they are also neutral, i.e. that they are asked in a way that does not give away the answer anticipated by the interviewer (Kaiser 2014: 8).

Since the city administration is responsible for the implementation of policies and the research aim is to investigate what hindrances exist in the transformation to a climate-friendly transport system, it was decided to conduct interviews with employees of SenUVK. Several civil servants within the departments of transport and climate protection were approached via email whereof four accepted to being questioned about their work and the state of climate and transport policies in Berlin. If requested, the interview guideline was provided beforehand. The interviewees agreed to being treated non-anonymously in this thesis and hold the following positions:

Name Department* Position InterviewDate of

Hermann Blümel** IV A Environment and Transport, E-Mobility 26 March 2018 Michael Färber III A BEK 2030: Energy, Economy, Transport 27 March 2018 Horst Wohlfarth von Alm** IV B Head of Division 19 April 2018

Dr. Julius Menge** IV A Commercial Transport, Deputy Head of Division 20 April 2018

Table 1: Interviewees from the city administration.

*The departments have the following responsibilities:

• III A Climate Mitigation and Adaptation

• IV A Policy Matters and General Development of Traffic and Transport

• IV B Planning and Design of Public Space, Walking, Biking

** were part of the project group developing the urban development plan StEP Verkehr 2025 in 2011.

Additionally, organisations that promote a specific kind of transport were approached in order to better understand the challenges they face. As there is only one larger organisation in Berlin promoting walking it was decided to approach the nation-wide organisation Fachverband Fußverkehr Deutschland (FUSS e.V.). Federal CEO Stefan Lieb agreed to being interviewed and subsequently elaborated on the organisation’s history, mission, and vision, the short-comings of Berlin’s walking infrastructure, and the challenges they face in promoting walking in Berlin and Germany. Regarding cycling, the regional section of the national organisation Allgemeiner Deutscher Fahrradclub (ADFC e.V.) was approached but the request has remained unanswered to this date. Additionally, a local initiative was approached that has been fairly active in the last couple of years promoting biking and the expansion of biking infrastructure in Berlin, that is Volksentscheid Fahrrad. Not least due to their activities, biking and biking infrastructure have recently become widely discussed topics in politics, media, and the public. Volksentscheid Fahrrad is officially affiliated to the non-profit organisation Changing Cities e.V. that not only promotes biking but pursues a more holistic approach towards an environmental-friendly and livable city. Denis Petri who, among other things, organised and coordinated the needed signatures for the initiative was approached directly via email and agreed to talk about the challenges in establishing biking as mode of transport in Berlin.

Last but not least, the regional department of one of the largest and oldest organisations on transport was contacted, the Allgemeiner Deutscher Automobil-Club (ADAC e.V.). To get a full picture of the pros and cons of the different modes of transport present in Berlin, the ADAC Berlin-Brandenburg was approached in order to take the perspective of motorised transport into account. Head of Transport, Technology, and Environmental Protection of ADAC Berlin-Brandenburg Jörg Becker agreed to answer questions on their point of view on Berlin transport policies, current and coming developments in Berlin and Brandenburg as well as opportunities and challenges of motorised transport. Especially the ADAC and Volksentscheid Fahrrad are

considered key stakeholders in Berlin’s transport policies as they shape and influence the public opinion on transport issues and, moreover, are or have been included in policy developments.

Name Organisation Position Date of Interview

Stefan Lieb FUSS e.V. Federal CEO 20 March 2018

Jörg Becker ADAC Berlin-Brandenburg Head of Transport, Technology, and

Environmental Protection 28 March 2018

Denis Petri Changing Cities e.V./

Volksentscheid Fahrrad Networking and Politics 03 April 2018

Table 2: Interviewees from transport organisations.

The interviews were conducted in person and were recorded. All the interviews lasted about one hour and were transcribed, translated, and summarised after the meetings. Since the positions and focus of work differed quite much between interviewees, the interview guidelines were individualised. However, they followed the same overall structure, that is in the case of the civil servants firstly general questions about their position in SenUVK and their department’s range of duty, secondly questions on fundamentals, design, and development of Berlin’s transport and climate policies respectively, and lastly more specific questions about their particular field of work as well as about normative, speculative, and forward-looking statements on the relation between climate protection and transport. The interview guidelines for the organisations also started with some general questions on their work and the state of transport in Berlin in order to make the beginning of the interview easier for the interviewee. They were then asked about the pros and cons of their mode of transport and the challenges they face in promoting it in Berlin. In the end, they were also asked normative, speculative, and forward-looking questions on the overall state of transport and climate protection in Berlin as well as about their future plans. In addition, one public hearing in the Senate of Berlin on the new Mobility Act was visited on 20 April 2018 which allowed for a better understanding of the controversies among the actors and the actors’ line of reasoning. Besides the politicians concerned and the audience, six stakeholders were heard and questioned by the Senate, that is Jörg Becker from the ADAC Berlin-Brandenburg, Denis Petri from Volksentscheid Fahrrad, Leszek Nadolski for Berlin cab companies, Sören Benn in the capacity of borough mayor of the district of Pankow, Dr. Lutz Kaden from the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Berlin, and Ulrike Pohl from a social welfare organisation speaking for the handicapped in Berlin. Additionally to the author’s own notes, the official records of this hearing (cf. Abgeordnetenhaus 2018) are available to the public and were used for the analysis.

3.3. Limitations of the Research Design

Although the research design was chosen carefully in order to arrive at the most viable results regarding the research aim, it is also limited by some drawbacks inherent to qualitative methods. Even though semi-structured interviews allow for a deeper insight into the reasoning behind policies, the findings are dependent on interpretation and thus prone to misinterpretation. Regarding the interviews, experts may – consciously or unconsciously – give false or misleading answers or only repeat official positions, especially since the interviews were recorded and transcribed (Kaiser 2014: 33). Additionally, they may reply in a way that they think are socially acceptable instead of revealing the actual considerations behind a policiy (Kaiser 2014: 33). However, these fallacies are countered by the careful development of the interview guidelines, the number and selection of interviewees and the inclusion of stakeholders from different backgrounds as well as by the triangulation of methods, that is the combination of academic literature, policy documents, and the interviews.

Due to a limited time frame of the author as well as of the civil servants and other stakeholders, only seven interviews could be conducted for this research. This again limits the generalisability of the data. However, despite of the small number, the length and depth of the interviews provided valuable insights into the inner workings of the city administration and transport-related organisations. Another drawback is that even though the individual interview guidelines allowed for more detailed and specific answers, they also limited the comparability of the interviews. Moreover, due to the limited time and resources, it was not possible to include the perspective of the districts or the citizens although they are considered important stakeholders in the matter. Furthermore, as this study focuses exclusively on the case of Berlin and uses qualitative methods only, the findings are not necessarily transferrable to other cities inside or outside of Germany. However, valuable insights into transport and climate policies in Berlin can be drawn from it and may apply in other cases, too. Understanding the mechanisms behind the climate compatibility of Berlin’s transport system through policy analysis and expert interviews allows for the identification of key aspects of transforming urban transport systems towards climate neutrality in general.

4. Analysis of Berlin’s Transport System and Policies

Berlin is located along the river Spree in the Northeast of Germany. In 2016, the 891km2 area was populated by 3.57 million inhabitants leading to a population density of 4000 people per km2 and thus making it the second most densely populated city in Germany (DeStatis 2018; StatBB 2018a). After the end of the second world war, Berlin has been reinstated as the capital of Germany and is today one if its three City-States. This means that it is a city as well as one of the 16 federal states of Germany. As it is therefore a rather special case, the following sub-chapter will first of all explain the federal setup of Germany and the resulting competences for Berlin in terms of urban transport.

4.1. Allocation of Competences in the Transport Sector

Germany is a federal state meaning that the power of the state is divided between its 16 federal states and the national state. Generally, it can be said that the national state is mainly responsible for the legislation while the execution and implementation of laws and regulations is executed by the federal states except in certain fields of action where the federal states have complete legislative powers such as culture and education (Rudzio 2011: 318; 332). The fields of transport and environment, however, are part of the competing legislation according to the constitution (Art. 72 I and Art. 74 I Nr. 22 GG) meaning that the federal states are allowed to legislate as long as the national state is not exercising its right to do so. Regarding the field of transport, the national state used its right to legislate, though, and issued national regulations for road traffic, the so-called Straßenverkehrsgesetz (StVG), Straßenverkehrsordnung (StVO), Allgemeine

Verwaltungsvorschrift zur Straßenverkehrs-Ordnung (VwV-StVO), and Bußgeldkatalog-Verordnung (BkatV).

While the StVG forms the basis for road traffic behaviour and, for example, grants the national minister for transport the right to issue regulations (§6 StVG), the StVO as one of these regulations defines more precisely what is allowed and what is prohibited on the road. It states, among other things, that the maximal speed in built-up areas is 50 km/h (§3 StVO), and gives information where parking is not allowed, e.g in front of dropped kerbs (§12 III StVO). The VwV-StVO explains and specifies the StVO even further for example on the implementation of traffic lights or road signs. The BKatV entails the schedule of penalties, for instance, that parking on sidewalks or bike lanes costs 20 to 35 € and that speeding can lead to penalties between 10 and 600 € and can contain a driving ban. These are regulations that the city of Berlin has to observe and cannot change itself.

On top of that, the 12 districts of Berlin also have some regulatory power. According to the constitution (Art. 28 II GG) the German municipalities have the right of self-government. Similarly, in Berlin, this autonomy is performed by the districts and their governing bodies, that is the district assembly, several district offices, and the district mayor. The allocation of responsibilities and competences is stated in Bezirksverwaltungsgesetz and Allgemeines

Zuständigkeitsgesetz (AZG). Regarding the field of transport, the districts are responsible for

stationary traffic, that is mainly parking, and traffic on side roads (SenUVK 2018a; AZG Appendix Nr. 10). This entails all kinds of parking regulations and management and

exemptions from them, bike lanes on side roads and the obligation to use them, exception permits for environmental zones, taxi ranks, construction sites, temporary stopping restrictions, and pedestrian zones (SenUVK 2018a). Also the public order office observing the compliance with these regulations falls under the responsibility of the districts.

Paying regard to these framework conditions, the city of Berlin still has the responsibility for all policy matters that affect the whole city such as the public transport system and the city’s main roads consisting currently of 1530 km compared to the overall amount of 5470 km of roads in Berlin (§3 I AZG; SenUVK 2017c; StatBB 2018b). It moreover has the possibility to make use of non-binding instruments such as guidelines and (financial) incentives to steer the districts into the desired direction. These competences are shared between the city administration, SenUVK, and the subordinated central traffic authority Verkehrslenkung Berlin (VLB). While SenUVK is in charge of overall planning and policy-making, the VLB is primarily responsible for managing moving traffic on Berlin’s main roads. In concrete terms, the VLB decides city-wide on the implementation of traffic lights, measures to increase traffic safety, the installation of dedicated bus lanes together with the BVG, the identification and labelling of main bike lanes, and, limited to the city’s main roads, also on speed limits, the establishment of one way streets, the erection of pedestrian crossings, and measures against harmful noise and other emissions (SenUVK 2018b; 2018c). To put it in a nutshell, while the national state set important framework regulations on transport that have to be followed on the regional and local level, the federal state of Berlin, that is SenUVK and VLB, is still responsible for overall and city-wide planning, moving traffic, and the city’s main roads, whereas the districts are in charge of stationary traffic as well as the city’s side roads.

4.2. Climate Goal and Transport Policies

In the past, the city of Berlin has issued several documents and policies that entail rules for climate-related transport development, mainly, however, after the reunification process. Thus only policies issued during the last 18 years (2000-2018) will be investigated and, furthermore, in all cases the latest version of a policy will be considered. This period gives enough time to see the implementation of at least short-term measures and some development in GHG emissions and transport behaviour as well as possible changes in objectives and priorities. With regard to climate-friendly transportation, the most important policies are the following:

Policy German title English title Year

BEK 2030 Berliner Energie- und Klimaschutzprogramm

Berlin’s climate protection

and energy policy 2018

StEP Verkehr 2025 Stadtentwicklungsplan Verkehr

Urban development plan

on transport 2011 Mobility Act Mobilitätsgesetz Berlin Mobility Act 2018

The BEK 2030 is the principal policy on climate protection in Berlin. It has been issued by the department for climate protection of SenUVK and is currently revisioned in order to evaluate on and further specify the implementation of its proposed measures. It entails the city’s goal of becoming climate neutral by 2050 and suggests measures and instruments in order to achieve it. According to it (BEK 2018: 6), the overall CO2 emissions of Berlin have to be reduced by 40 % until 2020, by 60 % until 2030, and at least by 85 % until 2050 compared to 1990 levels in order to achieve climate neutrality.

Transport is one out of five field of actions of the BEK 2030, the others being energy, buildings and urban development, economy, and private households and consumption. Within the field of transport, the BEK 2030 (2018: 90ff.) identifies three important key factors: modal split, fleet distribution, and fuel and energy consumption. The first factor, modal split, aims at achieving a shift from using MIT towards using the modes of the environmental cluster (Umweltverbund), specifically to reduce the share of MIT in overall use of transport to 22.5 % by 2030 and to 17 % by 2050 (BEK 2018: 90). The second factor is to change the type of fuel used by vehicles in Berlin, that is to achieve a shift from fossil fuels towards climate-friendly fuel (BEK 2018: 91). The third and last factor aims at decreasing the energy and fuel consumption through better engines, speed reductions, reduction of stop-and-go traffic, and an improved traffic flow (BEK 2018: 92). These factors are specified in the following 15 measures: making walking more attractive, developing the biking infrastructure and promoting e-bikes, developing and increasing the attractiveness of the public transport system, linking different forms of transport and sharing systems, researching possibilities for increased financing of infrastructural measures, parking management and regulations, shifting economic transport from road traffic to ships and trains, mobility management (information, public transport tickets for employees, etc.), increasing the significance of climate protection in contracts with transport companies, developing the infrastructure for alternative fuels, automatic driving for a better traffic flow, traffic management (e.g. traffic lights), speed reductions on Berlin highways (although there is no legal possibility to do so right now), making public vehicles climate-friendly and free of emissions, and reducing emissions from air transportation (BEK 2018: 91ff.).

Several difficulties in implementing these measures are mentioned in the BEK 2030, for instance, the reliance on national support, esp. regarding long-distance traffic, an unexpected growth in population during the last years and the resulting increase in traffic volume, as well as a high number of commuters from and to Brandenburg (BEK 2018: 11; 16; 89-90). Moreover, the allocation of competences is seen as problematic. As mentioned above, the city’s decision-making power is limited, on the one hand, by national regulations such as the StVO that does not allow for a speed limitation justified only by reducing CO2 emissions, and, on the other hand, by the competences of the districts regarding the planning and implementation of building projects and parking (BEK 2018: 91-92; 104). The BEK 2030 (2018: 90-92) furthermore states a conflict potential with car owners regarding the introduction of regulatory measures restricting car usage and/or favouring public transport on the roads as well as with regard to the introduction of fees and charges in that respect. Moreover, the high investments needed for improving the environmental cluster are mentioned as well as the high costs of building and maintaining the infrastructures for public transport and innovative technologies (BEK 2018: 90-91). Additionally, the document notes the constraints of having only limited and non-expandable

road space as well as the need for better information and consultation of traffic participants on how they can make their mobility behaviour more climate-friendly (BEK 2018: 88; 91).

In contrast, the StEP Verkehr 2025 mainly focuses on the general development of transport in Berlin. Its overall objective is to develop and ensure a sustainable transport system that is fit for the future (StEP Verkehr 2011: 7). It was developed in a consultative process called “Round Table Transport” where representatives of the city administration, political parties, the districts, the public transport system, and civil society actors worked together (StEP Verkehr 2011: 9). Its progress is evaluated every two years (cf. StEP V1F 2014; StEP V2F 2016) and a new StEP is currently under way. The Mobility programme 2016 was issued in the same year as part of the StEP Verkehr 2025 in order to specify its goals and to establish short-term measures until 2016. Additionally, within the StEP Verkehr 2025, a Masterplan Parken was decided upon but has not been issued yet.

In short, the StEP Verkehr 2025, on the one hand, aims at ensuring mobility for all the citizens as well as for economic actors and, on the other hand, takes the necessity to develop transport in an environmentally sound way into account, especially in regard to the decrease in natural resources and the challenges posed by climate change (Mobility programme 2011: 1). Among other things, the share of biking, walking, and public transport within the city is to be increased to 75 % until 2025 (StEP Verkehr 2011: 49). The StEP Verkehr 2025 (2011: 46-49) compartmentalises these two main objectives into 12 objectives that are categorised into economic, social, ecological, and institutional dimensions. The objectives impose, among other things, to improve the quality of life within the city through e.g. the removal of oversized streets, to strengthen the polycentric structure of Berlin, and to decrease the usage of resources, the damage to the local and global environment through noise and GHG emissions, as well as to have less newly constructed streets with barrier effects.

The 12 objectives are again specified into 44 goals of action and translated into specific measures (StEP Verkehr 2011: 46-49 and Annex I). In order to achieve and connect the objectives, goals of action, and measures, the StEP Verkehr 2025 (2011: 50ff.) moreover establishes seven partial strategies, for instance, to strengthen the environmental cluster; to improve the quality of the city, life, and the environment; and mobility and transport management. For the shorter time frame until 2016, the Mobility programme 2016 establishes eight different but linked items: securing and developing current infrastructure; making Berlin pedestrian- and bike-friendly; developing and improving the public transport system in an affordable manner; re-organising road traffic and improving the quality of the city; promoting and using technical and social innovations; increasing acceptance and supporting safe traffic behaviour; strengthening the interlinkage of Berlin with international transport networks; and making an effective economic transport compatible. This short summary already shows the complexity of the matter and the entanglement of policies, measures, strategies, aims, goals, objectives, and strategies. It should be noted that there are furthermore additional strategy papers on public transport, walking, and biking that will not be discussed here due to the limited scope of this thesis.