Caries Prevention Strategies Practiced In

Scandinavia

A literature study

Laith Hassan Fathalla

Supervisor: Jayanthi StjernswärdBachelor Thesis In Oral Health 15 Credit Point Malmö University Post-Graduate Program For Dental Hygienist Faculty Of Odontology

Course 6 _ May 2011 205 06 Malmö

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this literature study is to study the dental caries status (DMFT) of 12-years-olds in Scandinavia and describe and compare the different preventive strategies and methods used by different dental care personal in each country and between these three countries. To achieve the objective information from

scientific literature and publications, and data from WHO database on these three countries were used.

DMFT for 12-year olds in Norway was 1.7 (2004), 0.7 for Denmark (2008) and in Sweden 0.9 (2008). During the past decade, changes have occurred in the

prevention system of population- based prevention to individual-based prevention. This is a result partly of the low caries prevalence and partly because of a

disproportional distribution of caries in this target group. It is regarded as a smart solution to be able to access the most affected or at risk patients who have the most dental care needs.

The results showed different dental personals used different preventive strategies. Choices related to the use of fluoride vehicles were also varied. There were also differences in prevention strategies between different countries. This shows that despite the similarities in the dental teams, free and subsidized dental care for children there are also differences in quality of the offering of policies and practices. All this data confirm the differences between all three countries in choice of preventive method for risk and none-risk patients. This seems to be influenced by different cultural patterns within the dental professional

communities of each country. Differences in caries incidence probably could be due to different combinations of preventive methods.

There is a need for more research in this area. There is a need for a consensus about which strategy and approach is most effective and which one should be used against dental caries in risk and non risk patients, a consensus in which all countries agree to implement.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT 2 CONTENTS 3 1. INTRODUCTION 4 2. AIM 4 2:1 Issues/Questions 43. METHOD AND MATERIAL 5

4. RESULT 5

4:1 Caries 5

4:2 Financing of Dental Care 6

4:3 Oral Health Manpower 6

4:4 Provision of dental care 7

4:5 Caries prevention strategies 8 4.5.1- Population directed strategy 8

4:5.2- Risk strategy 9

4:6. Prophylaxis Methods 10

4:6.1 -Oral hygiene education, dietary advice and information on use

of fluorides 10

4:6.2- Using different fluorides vehicles 11

5. DISCUSSION 11

5:1 Caries 11

5:2 Financing of Dental Care 12

5:3 Oral Health Manpower 12

5:4 Public Dental Health Service (PDHS) 12

5:5 Provision of dental care 13

5:6 Caries Prevention Strategies 13

5:7 Oral hygiene education, dietary advice and information on use of

fluorides 14

5:8 Using different fluorides vehicles 14

6. Conclusion 15

ACKNOWLEDGMENT 15

1. INTRODUCTION

As dental hygienists, we are one group of dental personnel who see caries, do early detection and diagnosis and refer patients to the dentist when more treatment is needed. We also instruct the patient on how he / she should take care of their dental hygiene, and take responsibility to do dental prophylaxis. [1,2]

Caries is one of the world’s common chronic diseases in children but preventable and the prevalence varies among different communities. It has been estimated that 90% of schoolchildren worldwide and most adults have had dental caries

[3,4,5,6]. Various factors contribute to the development of dental caries including diet, poor oral hygiene, access to dental care, availability of dental care service and number of dentists/dental hygienists [5,7,8,9,10]. The methods for the prevention of dental caries may seem simple, but disagreement on effect is found in the scientific literature, and among dental services [3]. If caries is not treated in the early stages, the process can continue until the tooth is destroyed. Early detection and diagnosis of caries, risk assessment, identification of individuals at risk and treatment of initial caries is an important part of dental profession [1,3]. Scandinavia has excellent oral health and health resources, economy, oral care organisations, and also relatively similar culture and background. It would be interesting to therefore study the caries experience in these three countries and compare the prevention strategies implemented by these countries.

2. Aim

The aim of this study is to compare dental caries status in Denmark, Norway and Sweden, and try to describe the reasons for these values in these countries. The study will also explain the different preventive oral healthcare strategies and answer the following questions:

2:1 Questions

What is the caries prevalence, including DMFT values, for each country? What are the oral health and health expenditure, oral health manpower

including the number of hygienists and oral diseases prophylaxis strategies in these three countries?

How are the different approaches for caries prevention among 12-year old in each country carried out by the dentists and auxiliaries (nurse and hygienist)?

3. METHODS AND MATERIALS

A literature review based on text analysis of articles and reports related to this age group and caries was done. Information was sought from textbooks, dental journal and scientific articles from PubMed (www.pubmed.com), the WHO database (www.whocollab.od.mah.se), (www.tandlakartidningen.se) and Google (www.google.se). The search used the following keywords and mesh terms: Dental caries in Sweden /Denmark/Norway, Caries epidemiology in Norway, Oral health surveys in Sweden, Caries preventive methods in Denmark/

Sweden/Norway, Caries preventive strategies in Denmark/ Sweden/Norway, Preventive dental care in Sweden /Denmark/Norway. It chosen articles published within last 20 years.

The target audience for the study was 12-year-olds which is an indicator age group proposed by WHO. The reason that the WHO has chosen to follow and present the caries status for 12-year-olds is that this target group is available at school and they also have permanent teeth [5,11]. Information was further

supplemented by additional articles from the National Board of Sweden [1,12,13, 14,15], textbooks and four reports from SBU [7,16,17] .

4. RESULTS

4:1 Caries

DMFT is an index that measures the mean number of caries lesions in a person or a group and is used to calculate the caries experience (caries prevalence). It is a short term for mean number of Decayed, Missing, Filled, Teeth. If the mean number of caries tooth surfaces (S) is measured, then it is DMFS. Depending on the unit of measurement used it is called DMF-T or DMF-S [7,8,9].

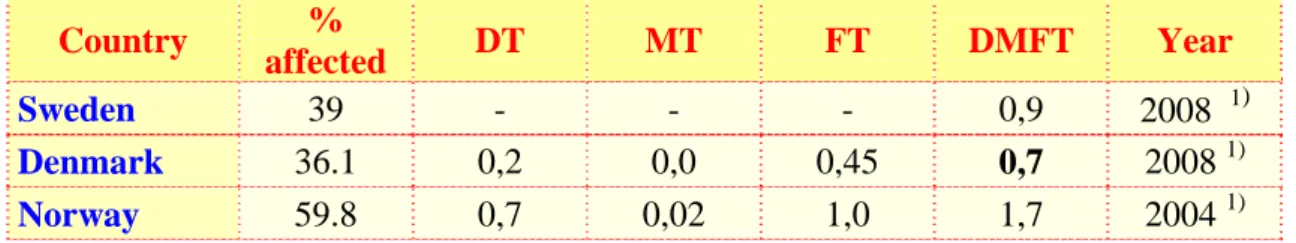

DMFT for the Swedish 12-year-olds is 0,9 in 2008, 0,7 in Denmark in 2008 and 1,7 for Norway in 2004 [5]. The distribution of D, M and F- values are reported for Denmark and Norway in 2008 and 2004 according to WHO, while these values were not available for Sweden. According the WHO, 39% of 12-year-olds have dental caries in Sweden and almost 60% of children in Norway have caries, while the figure is 36% for Denmark [5,13,16,17]. Twelve year olds in Denmark had the lowest DMFT in Scandinavia, while Norway has the highest value compared to its neighbours (Table 1).

Table 1. DMFT for 12-year-olds and the value of each component, and year the data taken from for Scandinavia.

Country % affected DT MT FT DMFT Year Sweden 39 - - - 0,9 2008 1) Denmark 36.1 0,2 0,0 0,45 0,7 2008 1) Norway 59.8 0,7 0,02 1,0 1,7 2004 1) 1. http://www.whocollab.od.mah.se/index.html [5]

4:2 Financing of Dental Care

The amount of government-funded health care varies significantly across

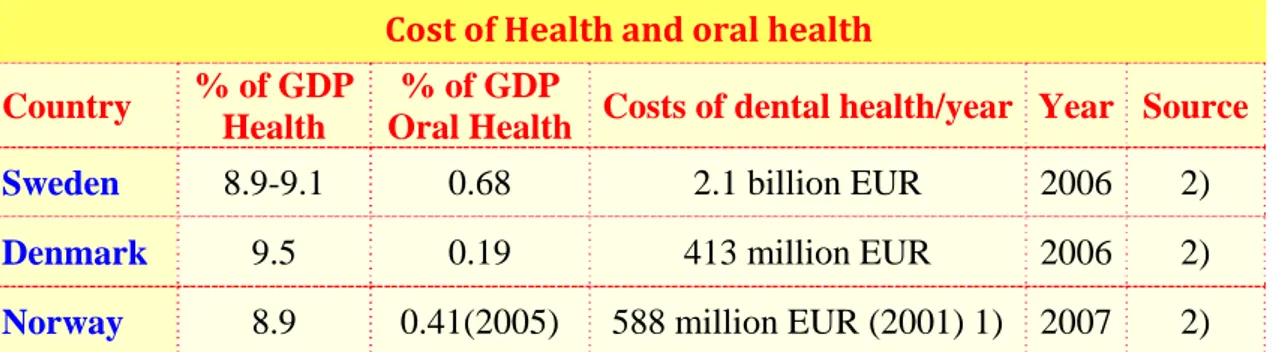

countries and funding for oral health as well. Each state allocates a certain portion of its state budget to public health each year and a small part is used for oral health care. The size of these proportions varies greatly between countries and even from year to year. According to data from the Council of European Dentists [18], Sweden invests more money on oral health care compared with Denmark and Norway, with 2.1 billion according the source for 2006. Values are given as percentage of total GDP (Gross Domestic Product) (Table 2).

Table 2. Funds allocated for Health care and Oral health care in Scandinavia, percentages of GDP

Cost of Health and oral health Country % of GDP

Health

% of GDP

Oral Health Costs of dental health/year Year Source

Sweden 8.9-9.1 0.68 2.1 billion EUR 2006 2)

Denmark 9.5 0.19 413 million EUR 2006 2)

Norway 8.9 0.41(2005) 588 million EUR (2001) 1) 2007 2)

1. Country/Area Profile Programme (http://www.whocollab.od.mah.se/index.html) [5] 2. Manual of Dental Practice. The Council of European Dentists, Nov 2008 [18].

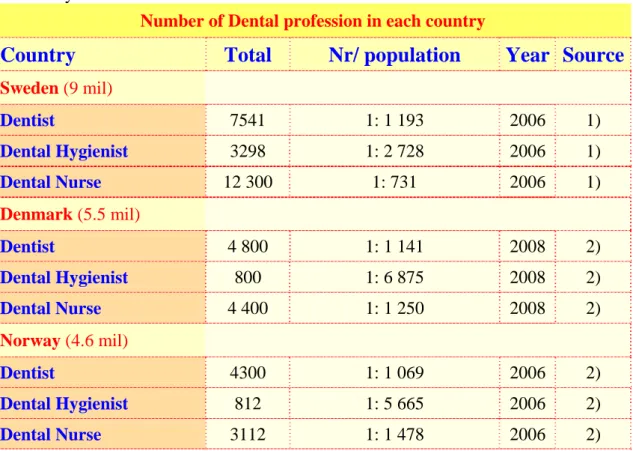

4:3 Oral Health Manpower

The number of dentist, dental hygienists and dental nurses differ between the various Scandinavian countries (Table 3), [5]. Sweden has a large number of dental personnel compared to the other two countries. The proportion of population per dentist is similar in all three countries however the ratios of population per dental hygienists ( 1: 2 728) and nurses (1: 731) is lowest in Sweden compared to the other two countries. Auxiliaries in these countries were almost in general female and younger than the dentist and with less work

Table 3. The number of oral health care personnel in Sweden, Denmark and Norway.

Number of Dental profession in each country

Country

Total

Nr/ population

Year Source

Sweden (9 mil) Dentist 7541 1: 1 193 2006 1) Dental Hygienist 3298 1: 2 728 2006 1) Dental Nurse 12 300 1: 731 2006 1) Denmark (5.5 mil) Dentist 4 800 1: 1 141 2008 2) Dental Hygienist 800 1: 6 875 2008 2) Dental Nurse 4 400 1: 1 250 2008 2) Norway (4.6 mil) Dentist 4300 1: 1 069 2006 2) Dental Hygienist 812 1: 5 665 2006 2) Dental Nurse 3112 1: 1 478 2006 2)

1) Swedish Dental Association [13].

2) Manual of Dental Practice. The Council of European Dentists, Nov 2008 [18].

4.4: Provision Of Dental Care:

Please note that the information in Table 4 to Table 9 show the dental care provision and caries preventive strategies for children in Scandinavia which is based on a questionnaire based study of 1570 dental personnel (969

dentists, 349 hygienists and 252 nurses), working in public dental services participating from Scandinavia [19, 20]. This study was published as two articles but based on one study.

Table 4 shows the distribution of dental personnel in dental clinics in Scandinavia. The mean number and proportion of dentist per clinic are almost double in

Sweden, while patients were examined longest (23 min) in Norway. The number of nurses in each clinic was more in Sweden than the other two countries. The recall intervals were a mean of nine months in Denmark while in Norway and Sweden it was just over a year. Auxiliaries perform routine examinations of children more commonly in Sweden (86%) and Norway (74%) but less common in Denmark (29%).

Table 4 Dentists and auxiliaries in dental clinics in Denmark, Norway and Sweden Denmark Mean Norway Mean Sweden Mean

Dentist per clinic 2.0 2.3 5.2

children under care per clinic 1653 1638 2803

Minutes for examination 17 23 14

Most usual recall interval in months 9.2 13.5 13.1

Nurses per dentist 1.6 1.1 2.1

% of clinics where auxiliaries performed

routine examinations 29 74 86

Dental auxiliaries- hygienists and nurses

4.5 Caries Prevention Strategies

The same studies also analysed the Population directed strategies and Risk strategies carried out by the dental personnel in Denmark, Norway and Sweden [19].

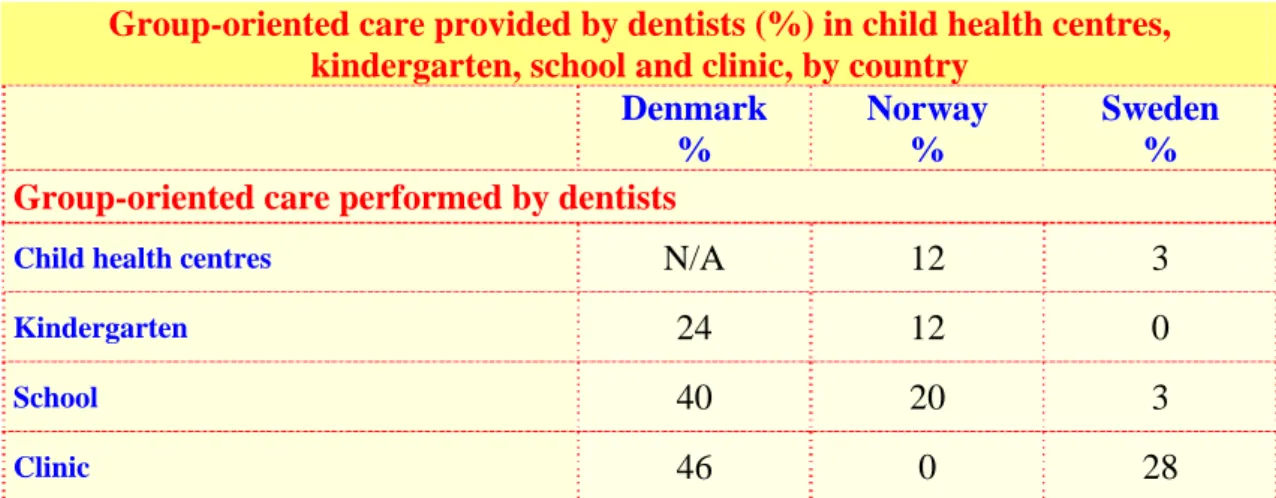

4.5.1- Population directed strategy: In population based strategy the whole group is targeted to receive the prevention methods. As we see, Table 5 shows percentages of dentists who provided group based preventive care in different settings. In Norway and Sweden there were only few dentists who participated in group-oriented preventive care. Unlike Norway and Sweden, group based

preventive care was more widespread in Denmark, 24% offered this service in kindergartens, 40% in school and 46% in clinics [19].

Table 5. Population based preventive care in different settings in Scandinavia. Group-oriented care provided by dentists (%) in child health centres,

kindergarten, school and clinic, by country

Denmark % Norway % Sweden %

Group-oriented care performed by dentists

Child health centres N/A 12 3

Kindergarten 24 12 0

School 40 20 3

4.5.2- Risk strategy:

In Risk strategy, children were identified as at risk for caries and caries prevention actions were carried out on these individuals. In other words Risk strategy targets individuals at risk when compared to population directed strategy where the whole group is targeted for prevention.

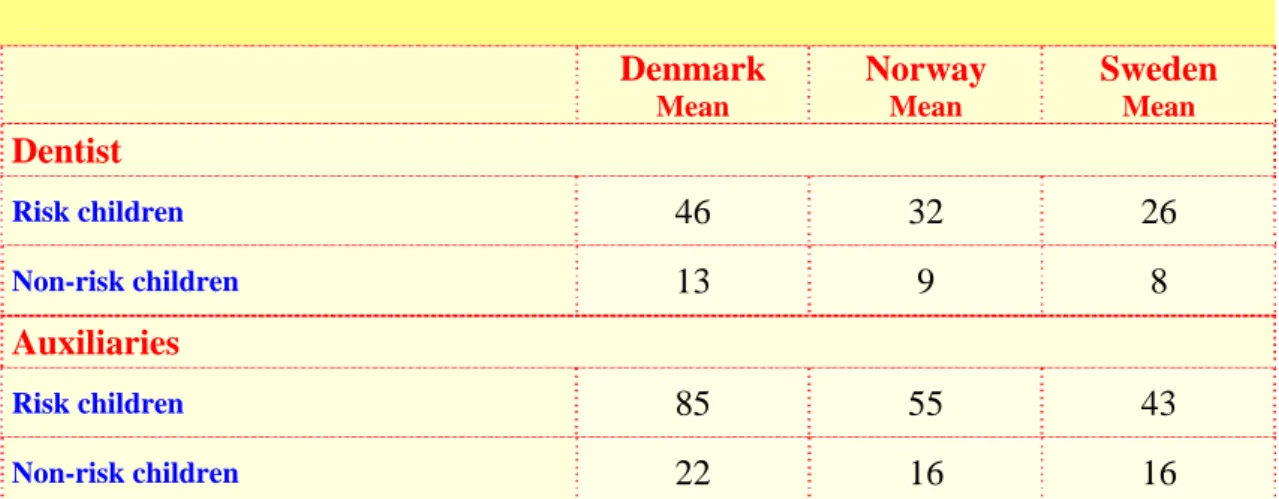

The approximate time in minutes spent on prevention for risk and non-risk child by profession per year is introduced in Table 6. In general, the time used for risk child was longer in all three countries. However, the differences in estimated time on risk and non-risk children by Danish profession were remarkably longer in particular for auxiliaries who gave longer time compared with other countries. Unlike Denmark, the time spent in prevention on risk children by Swedish dentists and auxiliaries was shortest when compared [19].

Table 6. Minutes per child per year spent for preventive care of risk and non-risk children, by profession and country

Denmark Mean Norway Mean Sweden Mean Dentist Risk children 46 32 26 Non-risk children 13 9 8 Auxiliaries Risk children 85 55 43 Non-risk children 22 16 16

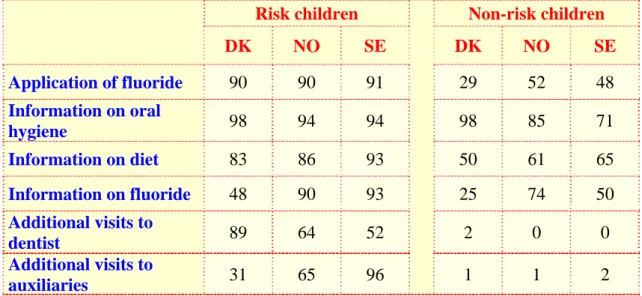

Table 7 shows dentists from the three different countries performing different preventive methods in clinics for risk and non risk children. In general, risk children were recalled more than non-risk children, by the dentist. Majority of dentists gave oral hygiene instructions to both at risk and non-risk groups from all three countries [19,20]. Unsurprisingly, most preventive efforts targeted the risk groups more than the non risk group. Oral hygiene instructions, application of fluoride and information on diet were the frequently chosen preventive methods by the dentists to the risk groups [19,20].

Table 7. Percentages of dentist using specific preventive methods for risk children and non-risk children, by country

Risk children Non-risk children

DK NO SE DK NO SE Application of fluoride 90 90 91 29 52 48 Information on oral hygiene 98 94 94 98 85 71 Information on diet 83 86 93 50 61 65 Information on fluoride 48 90 93 25 74 50 Additional visits to dentist 89 64 52 2 0 0 Additional visits to auxiliaries 31 65 96 1 1 2

DK=Denmark, NO=Norway, SE=Sweden 4.6 : Prophylaxis Methods

4.6.1- Oral hygiene education, dietary advice and information on use of fluorides:

According to the same studies (but in a different publication [20]), dentist offered frequently oral hygiene education to 76 -98% of the children and auxiliaries offered frequently oral hygiene education to 67 – 91% of children in these three countries as it shown in Table 8. Methods directed towards better oral hygiene were used mostly in Denmark and were dominant on all three countries.

Information about using fluoride was received least by the Danish children from the dentists and auxiliaries, but methods towards both allocation of fluoride and control of oral hygiene were almost equally important in Norway. While methods directed towards diet were also highly important for Swedish professionals [20]. Table 8. Percentage (%) of children for whom dentists and auxiliaries used different prevention methods, by country

Denmark Norway Sweden Dentists

Dietary advice 56 65 69

Oral hygiene instruction 98 86 76

Information on use of fluoride 29 76 57

Auxiliaries

Dietary advice 65 72 66

Oral hygiene instruction 91 90 67

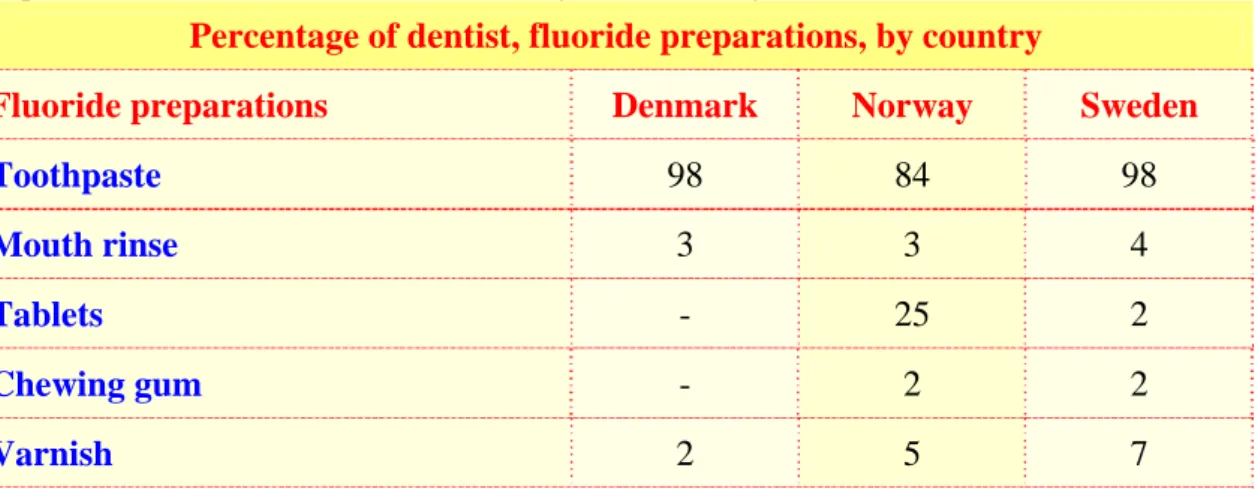

4.6.2- Using different fluorides vehicles

As shown in Table 9, fluoride toothpaste was recommended by majority of dentists in Scandinavia for all the children and almost half of them recommended fluoride toothpaste for young children [20]. Fluoride tablets were recommended by 25% of dentists from Norway to all the children, however no Danish dentist recommended that for any children. Only few Swedish dentists recommended fluoride tablets and proposed to some or few children [20].

Table 9. Percentage of dentist who recommended different fluorides as prevention methods for all children by each country

Percentage of dentist, fluoride preparations, by country

Fluoride preparations Denmark Norway Sweden

Toothpaste 98 84 98 Mouth rinse 3 3 4 Tablets - 25 2 Chewing gum - 2 2 Varnish 2 5 7

5.

D

iscussion:

5:1 Caries:In Scandinavia the percentage of caries free 12-year-olds increased in last 20 years which is mainly due to fluoride use and better dental care service. There is extensive research showing a significant association between the use of fluorides, particularly toothpaste and fluoride rinsing, and reduction in caries prevalence [14,17, 19,20, 21,22,23]. Analysis of Swedish national dental health data for children and adolescents suggest that fluorides are the main reason for

improvements in the last 40 years, the effect of school based programs have been documented by a decline in caries even before fluoride toothpaste came on the market 1970s [21,22,24,25]. The improvement in both primary and permanent teeth, are the result of systematic application of preventive measures and changing treatment practices over time from radical treatment forms such as tooth

extraction toward curative and preventive services which in recent years has being part of the regular examination in every oral health care clinics [6,14,17, 19, 20, 21,23,26]. It depends also on improved participation in oral health, changes in oral hygiene habits and sugar intake habits in these three counties.

WHO’s objective for Europe is that the mean DMFT in 12-years-old should not exceed 1.5 by 2020 [12]. Denmark and Sweden reached the target in 1991 and 1994respectively but Norway reached it in 1998 when it was 1.5 [5]. However, in 2004, the DMFT for 12-year-olds in Norway, showed a slight increase to 1.7 [5].

5:2 Financing of Dental Care

These three countries have quite similar economic conditions, ethos and priorities of good dental health. Sweden is investing huge sums of state budget for dental care compared with Denmark and Norway. Sweden has also significant higher GDP. In 1998 Sweden’s total oral health cost was approximately 1.29 billion EUR and the total cost of caries prevention for children was 21.6 million EUR [5,7]. In 2007, the total cost increased to 2.27 billion EUR, which is higher than in the neighbouring countries [5,14].

5:3 Oral Health Manpower

There are differences on oral health provision for children between these three counties [19,20]. In Norway oral health care for children was allocated normally by dentist and dental hygienist within Public Dental Health service, while in Sweden, the examination can be performed even by dental nurses, however the preventive care is provided by specially trained dental nurses in public Dental Health Service [20]. In Denmark both services provided mainly by dentist and in lower proportion by auxiliaries in Public Dental Health Service [19,20].

The overall ratio of population per profession were higher in Denmark (1:550) and Norway (1:560) compared to Sweden (1:390) [5,13]. This could mean that the dental personnel in these two countries have a higher work load than in Sweden which may lead to less time for proper preventive information and motivation of children and parents to a better oral health.

5:4 Public Dental Health Service (PDHS)

The dental act and legislation of preventive care are almost similar in these three countries. All children up to 19 year olds in Sweden, up to 17-year-olds in Norway, up to 18-year-olds in Denmark have right to oral health care free of charge or subsidized, providing health promotion, systematic prevention and curative care [13,17,19,20,27]. Oral care is governed by the Dental Act instead of the health care law and it has a different organizational structure.

Oral care in Norway is administrated by municipal School Dental Service SDS (7-15 years of age) and Public Dental Service PDS (6-17 year old) [21]. In 1973 the school dental activities transferred gradually to PDS [21].

The Swedish Dental Act specifies that the goal of dentistry is good dental health and dental care on equal terms for the entire population, and that particular attention should be given to preventive measures [15,25]. Dental care is also divided into public and private activities on a larger scale and could be performed by public or private dental clinics. The county councils are responsible that all children and adolescents are regularly being called to dentistry. The county council also funds dental care for this target groups up to 19 years-old. However, it is free choice for the patient to choose between public dental service or private dental care available in all counties [14, 15]. Today about 95 % of children and adolescents get dental care by public dental service, while private dental care cover on average for about 60 % of adult dental care [14,15]. Every county has

it’s own model of Health Promotion Strategies which differ marginally from other counties. Children’s Dental Service is characterized by a strong element of

preventive dentistry. Good dental habits are formed earlier in the preschool years [15].

In Denmark, preventive oral care is traditionally a community oriented program, which includes clinical oral care, oral care health education both for children and parents and prevention [19,20,26,27]. The Public Dental Health Service (PDHS) offers systematic dental care to children and adolescents. According to the Danish Act on Dental Care, all children provide health promotion, systematic prevention and curative care. [19,20, 26,27,28]. Preventive work in Danish clinics was and still is served mostly by dentists [27]. PDHS system which provides care is organized at the municipal level in two deferent ways. Since several decades the system in many municipalities offer dental care services to children as school based service by dentist employed in public dental clinics while the rest of municipalities have contracts with dentist in private practice who delivers care services for children and adolescents based on fee per treatment. The school based activities includes comprehensive school oral health education in classroom, supervised oral hygiene instructions, diet control, effective use of fluorides and fissure sealing of permanent molars [26,28]. Today almost 100% of target group (children) get service by PDHS and about 10% are covered by private practice [26,28].

5:5 Provision Of Dental Care

The questionnaire based study of dental health personnel in Scandinavia [19, 20] showed that the main deference between qualities in allocating care between these countries was the administration of dental care, strategies and the used resources. It should be noted that during the mid 1990s, the DMFT for 12-year olds in Denmark was 1.2 (1995), Norway 2.1 (1993) and Sweden 1.4 (1995), showing a similar pattern of the DMFTs as in the mid 2000 [5]. The oral public health practices among the dental professions in these countries seemed to be continuing in the same style in the past decade.

In this study we can see some clear differences between these three countries. Sweden has larger clinics with more auxiliaries, more dental assistants (nurses) per dentist, and more centralized treatment of children [19,21]. On one hand we have Sweden and Norway with long recall intervals and remarkable use of auxiliaries as regular routine examiners; In Denmark we have on the other hand, shorter recall intervals and less delegation of routine examinations to auxiliaries. In addition, dentists and auxiliaries in Sweden and Norway gave group-based preventive care to a limited amount while majority of Danish profession, both dentists and auxiliaries provided group-based prevention to their communities.

5:6 Caries Prevention Strategies

As to risk strategy, dentists in all three countries carried out individual clinical preventive care for both risk and non-risk children. Although many dental professionals gave same preventive approaches to all children, they gave

Earlier findings of Källestål and Holm (1994) showed Swedish teenagers with high caries activity did not receive more preventive care than others [29]. Unfortunately it seems so there are many dentists performing same preventive care to children irrespectively of risk or non risk status, which probably can be a consequence of difficulty in identifying risk group/ risk children with enough accuracy.

There are other Swedish studies from 1996 where they described how 49% of dental personnel performed individualized preventive care while 50% of clinics perform a combination of individual and population oriented preventive care [19,20]. That means the present strategy today in dental clinics is to combine the classic population based strategy but more focus on risk children. This is a clear evidence that population oriented strategy is not abandoned [19, 20].

However, in the middle of 1980s in Sweden and even in other two countries high-risk strategy was favoured in the oral health clinics [25,30]. The reason was that caries statistics showed that dental health in general has improved greatly, and the emergence of a skewed distribution of caries disease in the population. Further factors affected the perception of population based strategies like the economic situation during 1980-1990 which became tougher and many caries researchers questioned the additional effect of school programs for the daily use of fluoride toothpaste [25,30].

5:7 Oral Hygiene Education, Dietary Advice and Information On Use Of Fluorides

Data from these studies explain that the priority of preventive methods for Danish dental care providers was giving oral hygiene instruction while fluoride was marginally recommended for children and adolescents except for fluoride

toothpaste [19,20]. In Sweden, dietary advice and education on oral hygiene were both important. For Norwegian professionals both fluoride and oral hygiene instructions were equally important, but later studies showed that Norwegian dental professional still prefer to give oral hygiene instruction [19,20]. Danish dentist’s choice of preventive method did not change since early 1990s, advice focused on oral hygiene [20]. All this data confirm the differences between all three countries in preventive method of choice for risk and none-risk patients, which is influenced by different cultural patterns within the dental professional communities of each country. Differences in caries experience probably could be due to different combinations of preventive methods [20].

5:8 Using Different Fluorides Vehicles

Generally, fluoride toothpaste was available and recommended by dentists in all three counties. Topical applications of fluoride in different forms were used in clinics in different countries. There are no fluoride tablets on the market in Denmark and are not recommended by Danish dentists. In Sweden and Norway fluoride tablets were available and sold normally in pharmacy without

prescription. According to national recommendations, fluoride lozenges were recommended to use only for risk patients but not for young children [19]. The

fluoride varnish, Duraphat is common type used in Sweden and Norway while Danish dentists use even Fluorprotector [20].

Norwegian dentists even recommended fluoride tablets for most of children at (risk or not) and administrated fluoride varnish in clinics for most children. Fluoride lozenges were recommended also for caries risk patients in Norway. Swedish dentist recommended extra fluoride for some children and even fluoride varnish for some children. Swedish national recommendations on fluoride recommended daily tooth brushing two times per day to all children [20]. Children with high active caries or risk for caries get intensive treatment with fluoride varnish and recommended use of fluoride lozenges. Based on these studies it seems so that Danish dentist are moderate on fluoride use and recommendations for children and adolescents [20].

6. Conclusion

In Scandinavia, different dental personals used different preventive strategies. Choices related to the use of fluoride vehicles were also varied. The difference in prevention strategies were also between different countries. This shows that despite the similarities in the dental teams, free and subsidized dental care for children which is offered in public dental health care to children, there is still contrary in directives behind the prioritization of prevention strategies and there are also differences in quality of the offering of policies and practices. All three countries invest generous resources on prevention but the quantity of resources which used in prevention strategies and the quality of strategies varied among these countries.

Based on today’s evidence- based dentistry, there is still no evidence about which method alone or in combination is most effective on preventing caries. Therefore data providing evidence at population level are much needed. We need therefore further research in this area and analysis of the contributory benefits of various preventive methods towards caries disease in different populations of hopefully contribute to increased knowledge of dental health professionals about which method of prevention alone or combined is the most efficient.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I feel the greatest gratitude to my supervisor, Jayanthi Stjernswärd, WHO Collaborating Centre, Faculty of Odontological at Malmö University, whose expertise, support, patience and commitment contributed significantly to this thesis and even developed my knowledge. I appreciate her vast knowledge and understanding of the subject area. Thanks to her constructive criticism, guidance and encouragement I have been able to complete this work. Therefore I offer my regards, sincere appreciation and owe my deepest gratitude to her.

REFERENCES

1. Socialstyrelsen. Kompetensbeskrivning för legitimerad tandhygienist. Socialstyrelsen, 2005. www.socialstyrelsen.se (Retrieved April 2011)

2. KW,IMRE HT 96, rev VAP VT-10. Fluorbehandling. Klinisk PM. Malmö Högskolan-odontologiska fakultet, Kariologi avd.

http://www.mah.se/upload/OD/Avdelningar/Cariologi/PM/Fluorbehandling%20V t-10%20VAP.pdf (Retrieved April 2011)

3. Lingström P. Karies och erosioner. Teknologiskt institut;

http://www.teknologiskinstitut.se/_root/media/34326_Paradontit%20o%20karies_ pdf.pdf (Retrieved April 2011)

4. Petersen P.E. Tandhälsa ur ett folkhälso-perspektiv. Perspektiv: Nr 3. (2000). http://perspektiv.nu/files/Filer/PDF/perspektiv0003_svensk.pdf (Retrieved April 2011)

5. Caries for 12-Year-Olds by Country/Area. WHO Collaboration Centre. http://www.whocollab.od.mah.se/countriesalphab.html (Retrieved April 2011). 6. Alm A. On dental caries and caries-related factors in children and teenagers.

Swed Dent J Suppl, 2008; 195:7-63.

7. SBU- Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering. Att förebygga karies, en

systematisk litteraturöversikt. SBU-rapport (2002)

http://www.sbu.se/upload/Publikationer/Content0/1/karies_2002/kariesfull.html (Retrieved April 2011)

8. Hansson B, Ericsson D. Karies Sjukdom och Hål. 2:a upplagan. Stockholm: Gothia, (2008): 12-13,43-65

9. Widenheim J, Birkhed D, Renvert S. Förebyggande Tandvård. 2:a upplagan. Stockholm: Gothia, (2003): 28-47

10. 1177. Kost och tänder/Vad händer i kroppen.

http://www.1177.se/allakapitel.asp?CategoryID=37112&AllChap=True&PreView (Retrieved April 2011)

11. WHO. Oral Health Surveys - Basic Method. 4th Ed (1997), Geneva.

12. Socialstyrelsen. Karies hos barn och ungdomar. En lägesrapport för år 2008. Socialstyrelsen, 2010. www.socialstyrelsen.se, (Retrieved april 2011)

13. Socialstyrelsen. Tandhälsa. Folkhälsorapport, Socialstyrelsen, 2009. www.socialstyrelsen.se, (Retrieved april 2011)

14. Socialstyrelsen. Tandvård och Tandhälsa-sammanfattning. Hälso-och

sjukvårdsrapport. Socialstyrelsen, 2009. www.socialstyrelsen.se, (Retrieved april 2011)

15. Socialstyrelsen. Övergripande nationella indikationer för God tandvård. Socialstyrelsen, 2009. www.socialstyrelsen.se, (Retrieved april 2011) 16. SBU- Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering. Karies - diagnostik,

riskbedömning och icke-invasiv behandling: En systematisk litteraturöversikt.

SBU-rapport 2007

17. SBU- Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering. Karies hos barn och

ungdomar. En lägesrapport för år. SBU-rapport 2008: ( 2010).

18. Manual of Dental Practice. The Council of European Dentists, Nov 2008. http://www.eudental.eu/index.php?ID=35918 (Retrieved April 2011)

19. Wang NJ, Källestål C, Petersen PE, Arnadottir IB. Caries preventive services for children and adolescents in Denmark, Island, Norway and Sweden: strategies and resource allocation. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 1998; 26:263-271. 20. Källestål C, Wang NJ, Petersen PE, Arnadottir IB. Caries preventive methods used for children and adolescents in Denmark, Island, Norway and Sweden.

Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 1999; 27:144-151.

21. Von Der Fehr, Haugejorden O. The start of caries decline and related fluoride use in Norway. Eur J Oral Sci, 1997;105: 21-26.

22. Bratthall D, Hänsel-Peterson G, Sundberg H. Reasons for the caries decline: What do the experts believe?. Eur J Oral Sci, 1996; 104: 416-422.

23. Haugejorden & Birkeland. Karies I Norge for och I framtiden, analys av förändringar och orsaker. Tandläkartidningen årg 100 nr 2, 2008: 42-49

24. Birkeland JM, Haugejorden O. Caries decline before fluoride toothpaste was available: earlier and greater decline in the rural north than in southwestern Norway. Acta odontol Scand, 2001; 59: 7-13

25. Gabre P. Populationsstrategins återkomst. Tandläkartidningen årg 100 nr 2, 2008: 62-69

26. Petersen PE. Changing dentate Status of Adults, Use of Dental Health Services, and Achievement of National Dental Health Goals in Denmark by the Year 2000. J Public Health Dent. 2004; 64.No.3

27. Petersen PE, Torres A.M. Preventive oral health care and health promotion provided for children and adolescents by the municipal dental health service in Denmark. Int J Paediatr Dent, 1999; 9:81-91.

28. Christensen LB, Petersen P.E, Hede B. Oral health in children in Denmark under different public dental health care schemes. Community Dent Health, 2010; 27:94-101.

29. Källestål C, Holm A-K. Allocation of dental caries prevention in Swedish teenagers. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1994; 22: 100-105

30. Landstinget I Östergötland. Barn-och ungdomstandvård- åtagande och rutiner, 2011.

http://www.lio.se/pages/42607/1Uppdragsbeskrivning%202011.pdf (Retrieved April 2011)