Jönkö

p

ing

Un

ivers

ity

,

Schoo

l

o

f

Hea

lth

and

We

l

fare

SHOULD

I

STAY

OR

SHOULD

I

GO

–

Factors

assoc

iated

w

ith

hosp

ita

l

izat

ion

r

isk

among

o

lder

persons

in

Sweden

Jenny

Ha

l

lgren

DISSERTATION SERIES NO. 70, 2016

©

Jenny Hallgren, 2016Publisher: School of Health and Welfare

Print: Ineko AB, Göteborg

ISSN 1654-3602

“Whatis ageing? HereI might betoo expansivein a biological and

philosophical way, asI say: What doeslife consist of besides ageing? Itis so

banal.If you cannot relatetothefactthat you are ageing, you cannot relate

tolife. Itis aform of ethics oflife,itisthe most essential, and you needto

talk aboutitin all ages”.

Abstract

Anincreasingly older population will mostlikelyleadto greater demands on

the health care system, as older age is associated with an increased risk of

having acute and chronic conditions. The number of diseases or disabilitiesis

notthe only marker ofthe amount of health care utilized, as persons may seek

hospitalization without a disease and/or illness that requires hospital health

care. Hospitalization may pose a severe risk to older persons, as exposureto

the hospital environment mayleadtoincreased risks ofiatrogenic disorders,

confusion, falls and nosocomial infections, i.e., disorders that may involve

unnecessary suffering andleadto serious consequences.

Aims: The overall aim of this thesis was to describe and explore individual

trajectories of cognitive development in relation to hospitalization and risk

factors for hospitalization among older persons living in different

accommodations in Sweden and to explore older persons´ reasons for being

transferredto a hospital.

Methods: The study designs were longitudinal, prospective and descriptive,

and both quantitative and qualitative methods were used. Specifically, latent

growth curve modelling was used to assess the association of cognitive

development with hospitalization. The Cox proportional hazards regression

model was used to analyse factors associated with hospitalization risk over

time. In addition, an explorative descriptive design was used to explore how

home health care patients experienced and perceived their decision to seek

hospital care.

Results: The most common reasons for hospitalization were cardiovascular

diseases, which caused morethan one-quarter of first hospitalizations among

the persons living in ordinary housing and nursing home residents (NHRs).

The persons who had been hospitalized had a lower mean level of cognitive

performance in general cognition, verbal, spatial/fluid, memory and

processing speed abilities comparedto those who had not been hospitalized.

Significantly steeper declines in general cognition, spatial/fluid and

processing speed abilities were observed among the persons who had been

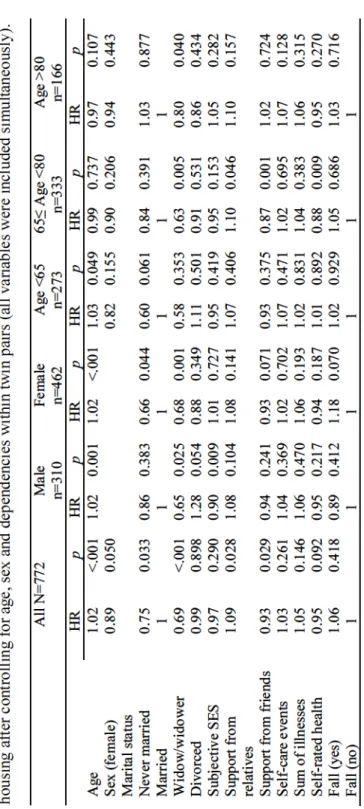

hospitalized. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis showed that the

assessed as malnourished accordingtothe Mini Nutritional Assessment scale

wererelatedto anincreased hospitalizationrisk amongthe NHRs. Amongthe

older persons living in ordinary housing, the risk factors for hospitalization

were relatedto marital status, i.e., unmarried persons and widows/widowers

had a decreased hospitalizationrisk.In addition, among socialfactors,receipt

of supportfromrelatives wasrelatedto anincreased hospitalizationrisk, while

receipt of supportfromfriends wasrelatedtoa decreasedrisk. The number of

illnesses was not associated withthe hospitalization risk for older personsin

any age group or forthose of either sex, when controlling for other variables.

The older persons who received home health care described different reasons

for their decisions to seek hospital care. The underlying theme of the home

health care patients’ perceptions oftheir transfer to a hospital involved trust

in hospitals. This trust was shared by the home health care patients, their

relatives andthe home health care staff, accordingtothe patients.

Conclusions: This thesis revealed that middle-aged and older persons who

had been hospitalized exhibited a steeper decline in cognition. Specifically,

spatial/fluid, processing speed, and general cognitive abilities were affected.

The steeper decline in cognition among those who had been hospitalized

remained even after controlling for comorbidities. The most common causes

of hospitalization amongthe older personslivingin ordinary housing andin

nursing homes were cardiovascular diseases, tumours and falls. Not only

health-related factors, such asthe number of diseases, number of drugs used,

and being assessed as malnourished, but also social factors and marital status

were related to the hospitalization risk among the older persons living in

ordinary housing and in nursing homes. Some risk factors associated with

hospitalization differed not only betweenthe men and women but also among

the different age groups. The information provided in this thesis could be

applied in care settings by professionals who interact with older persons

before they decide to seek hospital care. To meet the needs of an older

population, health care systems needto offerthe proper health care atthe most

appropriate level, and they need to increase integration and coordination

among health care delivered by different care services.

Keywords: Older persons, hospitalization,risk factors, cognitive decline,

qualitative content analyses,longitudinal, Cox regression,latent growth

Or

ig

ina

l

papers

Thethesisis based onthe following papers, which arereferredto bytheir

Roman numeralsinthetext:

Paper

I

Hallgren, J., Fransson, E.I., Reynolds, C.A., Finkel, D., Pedersen, N.L, &

Anna K. Dahl Aslan, A.K.(2016). Cognitivetrajectoriesinrelationto

hospitalisation among older Swedish adults. Submitted.

Paper

I

I

Hallgren, J., Ernsth Bravell, M., Mölstad, S., Östgren, C.J., Midlöv, P., &

Dahl Aslan, A.K. (2015). Factors associated withincreased hospitalization

risk among nursing home residentin Sweden: a prospective study with a

three-year follow-up. International Journal of OlderPeople Nursing.DOI:

10.1111/opn.12107.

Paper

I

I

I

Hallgren, J., Fransson, E.I., Kåreholt, I., Reynolds, C.A., Pedersen, N.L., &

Dahl Aslan, A.K. (2016). Factors associated with hospitalization risk among

communityliving older persons: resultsfromthe Swedish Adoption/Twin

Study of Aging (SATSA). Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics,

(accepted for publication). DOI:10.1016/j.archger.2016.05.005.

Paper

IV

Hallgren, J., Ernsth Bravell, M., Dahl Aslan, A.K., & Josephson, I. (2015).

In Hospital We Trust: Experiences of older peoples’ decisionto seek

hospital care. Geriatric Nursing: 36(2015)306-311.DOI:

10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.04.012

The articles have been reprinted withthe kind permission oftherespective

Contents

Abbreviations ...8

Preface ...9

Introduction...10

Background ...12

Ageing and health ...12

Biological ageing ...13

Cognitive ageing ...13

Illness and disease...14

Hospitalizations ...15

Riskfactorsfor hospitalization ...16

Hospitalization among older personsin Sweden ...18

Re-hospitalization...19

Negative outcomes associated with hospitalization ...19

Ambulatory care-sensitive conditions ...21

Swedish health and social care ...22

Andersen’s behavioural model of health care utilization ...27

The active ageing policy framework ...31

Rationale ...33

Aims ...35

Methods ...36

Design ...36

Studiesincludedinthe quantitative studies (I,II andIII) ...37

Measurements (studiesI,II, andIII)...42

Data analysis ...45

Ethical considerations ...48

Results ...50

Cognitive changein relationto hospitalization (studyI) ...50

Causes of hospitalization (studiesII andIII) ...54

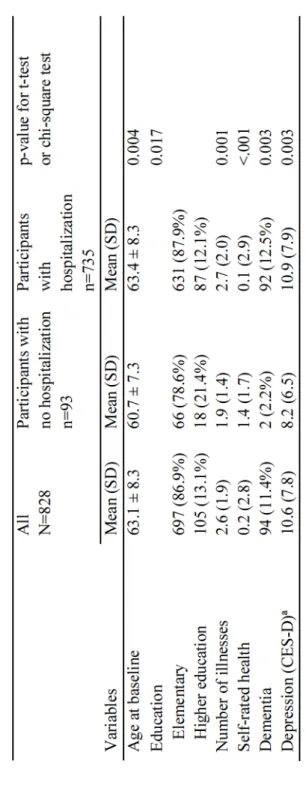

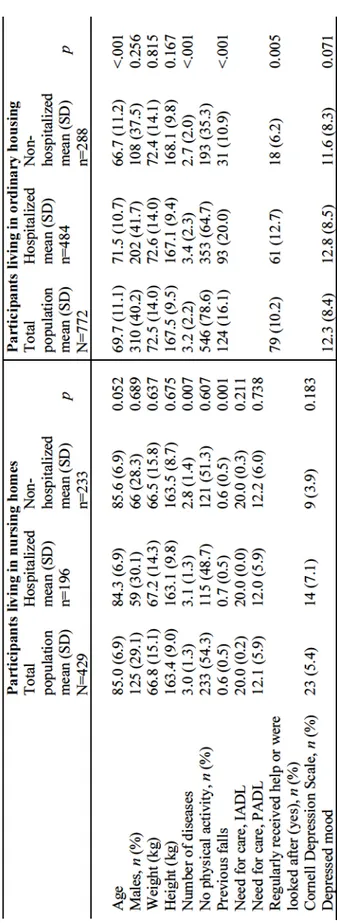

Baseline characteristics of hospitalized and non-hospitalized participants (studiesII andIII) ...56

Riskfactorsfor hospitalization (studiesII andIII) ...58

Reasonsfortransfer of older personsto a hospital (studyIV) ...63

Discussion ...66

General discussion ofthe results ...66

Methodological considerations ...78

Comprehensive understanding ...83

Conclusion ...86

Relevance andimplications ...87

Future research ...89

Svensk sammanfattning ...90

Acknowledgements ...93

Abbrev

iat

ions

ACSC Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions

ADL Activity of Daily Living

CES-D Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

CHF Congestive Heart Failure

COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

ED Emergency Department

EU European Union

ICD-10 International Classification of Diseases and related Health

Problems 10thRevision

IPT In Person Testing

MMSE Mini-Mental Status Examination Test

MNA Mini Nutritional Assessment

NHR Nursing Home Residents

OECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

RN Registered Nurse

SES Socio Economic Status

Preface

the physician asked mein one of hundreds

of medical consultationsthatI attended while working as a nursein a medical

wardin an acute hospitalin Sweden. I did not know, asit was not clearinthe

medicalrecord andthere were no obvious signs of any disease, whythe older

man had sought care atthe emergency department earlierthat morning. After

many hoursinthe emergency department waitingforthe physicianto examine

him,the old man was so exhaustedthat he hadlain down onthe bench beside

him. Routine bloodtests did reveal that his electrolyte status was not within

thereferencerange andthat some adjustmentsto his medications were needed,

as with many older persons. Duetothe generalstate ofthis manandthe

adjustmentsrequiredto his medications,the physicianthought thatit was best

to hospitalize him,justin case. Laterthat day, Itookthetimeto sit down and

talkto him properly. After a few minutes,it was clearto methatthe man was

not sure why he had sought care atthe emergency departmentthat day. He had

beencalling his primarycare, but the voice mail hadinformed him that he

wouldreceive a callfrom a nursethefollowing day. The old man did not want

to wait untilthe next day. He wantedto meet with health carestaff onthat day.

Duringthelast month, he had been feelingtired, hislegs had felt heavier, he

had experienced difficulty walking, and he had feltlonely.

The old man did not actually need hospital health care.If health care at alower

level had been available onthe same day,this man probably would not have

been hospitalized. Thisscenariois commonfor many people every day.

During mytime as a nurse at a hospitalin Sweden, I met many older persons

whoforsomereason had chosento seek hospital careinstead of care at alower

level or as a substitute for something else. These persons should have been

takencare ofata primarycare, municipalcare orsome othertype ofcare

facility,not inthe hospital setting. As a graduate student,I hadthe opportunity

to explore some areas within this research field. Do older persons who seek

hospital care have somethingin common?If we canidentify persons atrisk of

Introduct

ion

Rising life expectancy and an increasingly older population will most likely

leadto greater demands on health care systems, as older ageis associated with

anincreased risk of development of acute and chronic conditions. According

tothe Health and Medical Services Act 2§,

to provide good health and care on equal terms for the entire population,

giving priority to those most in need (SFS 1982:763). Coordinationand

continuity of health care can be difficultfor some older persons because many

ofthem meet with different care providers at differentlevels of care each year

(Modin & Furhoff, 2004). The most appropriate carelevelis not always clear

in each situation, and different carelevels have differentlevels of availability.

Today, a substantial number of older personslackthe knowledge, ability and

patienceto seek health care atthe appropriatelevel. Further, some carelevels

are not available during the evening, at night or on weekends. As a

consequence, older(and younger) personssometimesseekcareat andare

transferredto a hospital when alowerlevel of care would be preferable. Every

year, 1.4 million visits are madeto acute care providers or hospitalsin

Sweden,and one-third ofthese visitsare made by older persons (National

Board of Health and Welfare, 2015d). Many hospitalizations of older persons

are believedto be unnecessary, and/orthese persons could have beentreated

at alowerlevel of care (primary care and/or outpatient hospital care) (Berry

et al., 2011). Littleis known about why older persons aretransferredto

hospitals and whetherthere are certain older persons who are at a higher risk

of being hospitalized(Condelius, 2009). Hospitalization, which isthefocus of

thisthesis,is defined as staying at an acute hospitalfor one or more nights.

Hospitalization may pose a severe risk for older persons, as exposure to the

hospital environment mayleadtoincreasedrisks ofiatrogenic disorders,

confusion,falls and nosocomialinfections,i.e., eventsthat mayinvolve

unnecessary suffering andleadto serious consequences (Creditor, 1993;

Grabowski, Stewart, Broderick, & Coots, 2008; Intrator et al., 2007;

Ouslander et al., 2009). Alreadyin 1967, areport was publishedthat described

how physiological changes occurin healthy,ill orinjured persons who

undergo bedrest(Olson, 1990). However,the possible consequences affecting

different cognitive domains that occur several years after hospitalization are

hospitalizationiscostlyforsociety becausein-patientcareissignificantly

more expensivethan outpatient or primary care (Byrd, 2009). An investment

in increased care at a lower level would probably reduce overall

hospitalization costs(Intrator et al., 2007).Inthisthesis, persons 65 years and

above are referred to as older persons; well aware that it may differ

substantiallyin both physical and cognitive health, whetherthey are 65 or 85

years of age. Notably, this thesis should be interpreted on the basis of how

Background

Age

ing

and

hea

l

th

Worldwide population ageing, a high life expectancy, and declining fertility

areleadingto a significantincreaseinthe proportion ofthe populationthatis

overtheage of 65. Attheend of 2014in Sweden, one-fifth of thetotal

population wasabove 65 years ofage(SCB, 2016). Lifeexpectancy has

increased substantially duringthe second half ofthelast century, andin 2014,

the life expectancies of Swedish men and women were 80.1 and 84.0 years,

respectively (SCB, 2016). Although public health care in Sweden has

generally improved and disease onset often occurslater in life, many older

personslive for several years with disease. Thistrendis mainly explained by

reduced mortality from cardiovascular diseases (CVDs)

(Folkhälsomyndigheten, 2014).

Health is a multifaceted concept that includes different meanings and

dimensions. Health care, which should promote health, may beinfluenced by

an individual dimension, a societal dimension, i.e., the way society is

structured,andanenvironmental dimension,i.e.,the physical environment

affectingthe person (Naidoo & Wills, 2009). The World Health Organization

(WHO) defines healthas a state of complete physical, mental and social

well-being and not merelythe absence of disease orinfirmity (World Health

Organization, 1948). According to international human rights laws, all

persons,including old persons, havethe rightstolife andto health, as well as

to participate and maketheir own decisions abouttheir health based on

relevantinformation (United Nations Human Rights. General Assembly,

1966). Equal health care access should be a human right for all people of all

ages. Research that contributes toenabling all persons to receive equal and

appropriate health careis vital. Surprisingly,thereis no common definition of

,althoughthistermiscommonly usedin policy

practice as well asin research. The Organization for Economic Co-operation

and Development(OECD) defines healthy ageing as

personsin good health and keepingthem autonomous andindependent over

(Oxley, 2009), while The Swedish

NationalInstitute of Public Health(Swedish NationalInstitute of Public

physical, social and mental health to enable older persons to take part in

society without discrimination andto enjoy anindependent and good quality

. Although several studies have assessed healthy ageingin analyses of

health-related aspectsin older persons(Ennis et al., 2014; Simons, McCallum,

Friedlander, & Simons, 2000), some studies have arguedthatthe concept of

healthyageing may not beapplicabletothe oldest old persons (McKee &

Schüz, 2015) becauseitignoresthe physical realities of persons of advanced

age associated with biological ageing(Stephens, Breheny, & Mansvelt, 2015).

B

io

log

ica

l

age

ing

Thechangesthatinfluenceandconstituteageingarecomplex(Kirkwood,

2008). Biological ageing refers to the degree of age-associated decline

experienced by anindividual (Kaeberlein & Martin, 2015). As ageincreases,

numerous underlying physiological changes occur. From a biological

perspective, ageing is associated with a wide variety of cellular damage that

affects differentsystemsandtheirabilitiestofunction(Steves, Spector, &

Jackson, 2012; Vasto et al., 2010). Overtime,this damageleadsto a decrease

in physiologicalreserves and a general declinein health,leadingtoincreased

risks of many diseases. Forinstance,age-relatedlossesin motorfunction,

hearing and vision occur morefrequently withincreasing age(Cruz-Jentoft et

al., 2010; Hickenbotham, Roorda, Steinmaus, & Glasser, 2012; Yamasoba et

al., 2013). Diseases such as heart disease, stroke,respiratory disorders, cancer

and dementia are commonin old age. Further,the number of chronic diseases

is associated withincreased physical functioning difficultiesin persons of all

ages, and decreased physicalfunctioning has beenshownto be an early

marker of declining health (Guralnik et al., 2000). The combination of

different diseases,i.e., multi-morbidity, alsoimpacts physicalfunctioning and

isassociated withanincreasedrisk offrailty(Ernsth Bravell & Mölstad,

2010).

Cogn

i

t

ive

age

ing

Withincreasing age, a higher proportion ofindividuals exhibit cognitive

decline. The risk of decline in cognitionincreases with each decade over 60

thatisreached. However, manyindividuals do notshowcognitive decline

untilthelast years oflife, and some even show cognitive gains from midlife

functioning and are thus diagnosed with dementia (Schaie & Willis, 2016).

The mostcommon pattern ofcognitiveageingischaracterized by modest

declinesin most cognitive abilities startinginthe early 60s and continuingto

theearly 80s, when more marked decline occurs (Bosworth, Schaie Willis,

1999). However,there arelarge differences in cognitive performance and in

the rate of decline among individuals, and these difference seem to increase

in old age(Lövdén, Lindenberger, Schaefer, Bäckman, & Florian, 2010;

Steves et al., 2012). This variation in cognitive decline has also been shown

to beinfluenced by factors such as socioeconomic status,lifestyle and

medication use (World Health Organization, 2015), partly because many of

the mechanisms ofageingare random. However,this variationalso occurs

becausethesechangesarestronglyinfluenced bytheenvironmentand by

individuals behaviours. Loss of cognitive functioning may negatively affect

the self-care component of health care andthereforeincreasethelikelihood of

development of medical conditions. Lack of health-related behaviours, such

as medication adherence (Insel, Morrow, Brewer, & Figueredo, 2006), oral

hygiene maintenance (Wu, Plassman, Crout, & Liang, 2008) and avoidance

ofaccidentalfalls(Welmerink, Longstreth, Lyles, & Fitzpatrick, 2010),is

associated with a lower level of cognitive functioning and may increase the

need forformal health care.

I

l

lness

and

d

isease

Remaining healthyandavoidingchronic diseasesin oldageare desirable.

However,the number of diseases orlevel of disabilityis nota completely

accurate marker of quality of life and/or the amount of health care utilized.

Individualsseeking care may not alwaysrecognize whatis causingtheir

uneasiness. The abilityto distinguish between symptoms and signs,i.e., what

the care-seeking person describes andthe measurable or ocular signs of

illness,is vital (Ekman, 2014). Disease can occur without affecting a person

and withoutrequiring anytreatment. Likewise, a person may seek health care

and/or be hospitalized without having any disease and/orillness. Earlier

definitions ofillness were focused primarily on diseases,i.e.,

if and onlyif he or she has a disease whichis serious enoughto be disabling

(Boorse, 1977). However, more recent definitions are focused more on signs

and symptoms. Eisenberg and Kleinman define disease as n abnormalityin

andillness as

(Eisenberg & Kleinman, 2012). Theillness process begins with awareness of

a changeinthe body, and sometimesthe person cannottell what is wrong. The

(Kleinman,

Eisenberg, & Good, 2006).Illness and disease areimportant aspects affecting

health care utilization.

Hosp

i

ta

l

iza

t

ions

Hospitalization is common among older persons in Sweden and

internationally. Among older personsin general,the most common causes of

unplanned, i.e., non-elective, hospitalization, are cardiac insufficiency,

pneumoniaandchest pain(Table 1). The mostcommonreasonthat older

persons aged 65 years and above receive treatment for injury is due to falls

(44% of all admissions duetoinjury)(National Board of Health and Welfare,

2015c).

Table 1. The 10 most common causes of unplanned hospitalization among

persons aged 65 years and abovein Swedenin 2012(National Board of Health

and Welfare, 2013a).

Diagnoses Number of hospitalizations

Cardiacinsufficiency 21 543

Pneumonia 16 510

Chest pain 15 388

Atrialfibrillation and flutter 11 382

Cerebralinfarction 11 287

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 10 959

Bacterial pneumonia 9911

Acute sub-endocardialinfarction 9452

Atrialfibrillation 9418

R

isk

fac

tors

for

hosp

i

ta

l

iza

t

ion

Differentfactors have beenfoundto be associated with anincreased or

decreased hospitalization risk. Previous studies have reported that increased

age andthe male gender are risk factorsfor hospitalization (Dorr et al., 2006;

Ehlenbach et al., 2010). Previous hospital admissions (Landi et al., 2004) and

an increased number of contacts in outpatient care are associated with even

more hospital admissions (Condelius, Edberg, Jakobsson, & Hallberg, 2008).

Cognitive function (Dorr et al., 2006; Wilson et al., 2013) and comorbidity

(Dorr et al., 2006)increasethe hospitalization risk. Specifically,the presence

of one or more geriatric conditions (depressive symptoms, cognitive

impairment, falls, and urinary incontinence)is associated with an increased

number of hospitaladmissionsanda longerlength of hospitalstay(Wang,

Sheu, Shyu, Chang, & Li, 2014). As aresult of diseases, alarge proportion of

older personstake many prescribed drugs,as wellas manyinappropriate

drugs, which alsoleadsto anincreased hospitalization risk (Albert, Colombi,

& Hanlon, 2010; Klarin, Wimo, & Fastbom, 2005). Many older persons need

help withtheir medications. Lack of medication assistance among older

personsin need of medication supportis relatedto hospitalization (Kuzuya et

al., 2008). Further, polypharmacyisitself ariskfactorfor hospitalization, and

50% of medication-related hospitalizationsare believedto be preventable

(Jensen, Friedmann, Coleman, & Smiciklas-Wright, 2001; Mazzaglia et al.,

2007; Rogers et al., 2009). Previous studies have shownthatreduced physical

function(Carter, 2003; Grabowskietal., 2008),low physical performance

(Dorr et al., 2006; Li, Chu, Sheu, & Huang, 2011), and limitations in daily

livingactivities(Li, Chang, Wang, & Bai, 2011)affect hospitalizationand

care needs,suchasthoserelatedto pressure ulcersandfeedingtubeand

catheter use(Albertetal., 2010; Flaherty, PerryIII, Lynchard, & Morley,

2000; Fried & Mor, 1997; Horn, Buerhaus, Bergstrom, & Smout, 2005).

Different aspects of nutrition seemto haveimportantinfluences onthe

hospitalizationrisk. The use ofspecial dietsand weightloss increasethe

hospitalization risk (Jensen et al., 2001), as well asthe nutritional risk (poor

appetite and oral health problems) (Buys et al., 2014). Further, the presence

of obesity at 25 years of ageis predictive of avoidable hospitalizationinlater

life(Schafer & Ferraro, 2007). A Canadianstudy hasrevealedthat older

rate andthatthose who consume atleast one drink per week havethelowest

rate (Wilkins & Park, 1996).

Personalityis also associated with anincreasedlikelihood of emergency

department (ED) visits (B. Friedman, Veazie, Chapman, Manning, &

Duberstein, 2013), but no association with hospitalization has beenidentified

thusfar. Further, socialrelationships have beenfoundto not only decreasethe

hospitalization risk (Laditka & Laditka, 2003) but also to have heal

th-promoting effects(House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988). However,few studies

have examined experiences (Huckstadt, 2002).

During hospitalization, some people feel that they are left out, not provided

with information and given mixed messages(Dilworth, Higgins, & Parker,

2012). Others experience a sense of securityinthe hospital setting, meaning

thatthey feel safe being cared forin a hospital (Andersson, Burman, & Skär,

2011; Dilworth et al., 2012).

The hospitalizationrisk may differamong older personsliving in different

accommodations. Studies conductedinthe U.S. have demonstrated that

increasedage,reduced physicalfunction(Carter, 2003; Grabowskietal.,

2008)andcare needsareassociated withanincreased hospitalizationrisk

among nursing home residents (NHRs) (Albert et al., 2010; Flahertyetal.,

2000; Fried & Mor, 1997; Horn et al., 2005). In contrast, older persons who

livein ordinary housingin Sweden have similarlengths of hospital stays,take

similar amounts of drugs and have similar numbers of comorbidities but are

hospitalized morefrequentlycompared withthoselivingin nursing homes

(Condelius, 2009). Older personslivingin nursing homes are commonlythe

most diseased elderly, and accordingly, they have the highest need for care

(Grabowski et al., 2008). Hence,the disease burdenis nottheonly factorthat

influences whois hospitalized.

Livingarrangements mightinfluencetheassociations ofsomefactors with

hospitalization. For example,in several studies, a dementia diagnosis has been

shownto havea protectiveeffectagainst hospitalizationfor older persons

livingin nursing homes (Fried & Mor, 1997; Grabowski et al., 2008) and for

thoselivingin sheltered housing(Becker, Boaz, Andel, & DeMuth, 2012) but

notforthoselivingin ordinary housing(Dorr et al., 2006). Further, an

increased hospitalization risk has been reported among older persons

receiving home healthcare wholack medicationassistance(Kuzuyaetal.,

care aslowintensive comparedto hospital care (Fried, van Doorn, Tinetti, &

Drickamer, 1998), which might explain why one-third ofthese patients decide

totransfertoa hospital without prior medicalconsultation(Crossen-Sills,

Toomey, & Doherty, 2006).

Hosp

i

ta

l

iza

t

ion

among

o

lder

persons

in

Sweden

In Sweden, accessto hospital careis based on need, i.e., those mostin need

are prioritized. In addition, patients are only charged a nominal fee, sothere

are no economic barriersto seeking hospital care. Few studies have examined

hospitalization and predictors of hospitalizationin Sweden (Condelius et al.,

2008; National Board of Health and Welfare, 2014a). Studies conducted in

Sweden have suggestedthat among frail older persons orthose with complex

health problems, almost 40% are hospitalized atleast once each year(National

Board of Health and Welfare, 2014a). Further, older personslivingin ordinary

housing have anincreased number of hospital admissions comparedto NHRs

althoughthey are younger and havelessfunctional decline, which may

indicatethat hospital careis more accessibleto younger elderly and healthier

persons (Condelius, 2009). A study conducted in southern Sweden has

revealedthat a small group (15%) of older persons aged 65 years and above

has been admittedtothe hospitalthree or moretimes during one year,

accountingfor one-third ofthetotalin-patientcare. Additionally,alarge

proportion of hospitalized persons do notreceiveany municipal health or

service care; instead, they have increased contacts in outpatient care

(Condelius, 2009; Nägga, Dong, Marcusson, Skoglund, & Wressle, 2012).

The numbers of both diagnoses and physician contactsin outpatient care are

predictors ofthe number of admissions(Condelius et al., 2008). Some studies

have suggestedthat NHRs are frequently hospitalized (Kirsebom, Hedström,

Wadensten, & Pöder, 2014)andthatsome ofthese hospitalizationscan be

prevented (Kirsebom, 2015). However, the referral of NHRs with cognitive

Re-hosp

i

ta

l

iza

t

ion

A number of hospitalizationsleadtore-hospitalization,i.e., hospitalization

within 30 days after hospital discharge. As many as 30% ofre-hospitalizations

are believedto be preventable (Byrd, 2009). Congestive heart failure (CHF),

pneumonia (Jencks, Williams, & Coleman, 2009), and renal conditions

(Gabayanetal., 2015; Ouslanderetal., 2010),inadditionto stroke, hip

fractureandchronic obstructive pulmonary disease(COPD)(Bravata, Ho,

Meehan, Brass, & Concato, 2007; French, Bass, Bradham, Campbell, &

Rubenstein, 2008), arethe most common diagnoses associated with

re-hospitalization. According to patients, the reasons for re-hospitalization

include alack ofinformation or receipt of mixed messagesinthe hospital, as

well as disappointmentinthe health care system (Dilworth et al., 2012).

In Sweden, onereasonforre-hospitalization may bethat older patients seldom

participatein medical decision makingregarding discharge planning(Ekdahl,

Linderholm, Hellström, Andersson, & Friedrichsen, 2012). Thislack of

participation is particularly common when the health problems are not

pronounced and when no changesinthe medicationlist are needed. Because

the decisionto discharge a patientfromthe hospitalis made quickly and often

without patientinvolvement, a patients needs at home are not alwaysfulfilled

following discharge (Ekdahl et al., 2012). Many older persons admitted to a

hospital do not receive any health care or primary or municipal care services

(Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, 2013), whichlimits

the opportunity to decrease the risk of re-hospitalization through preventive

actionsin existing home health care or home help services.

Nega

t

ive

ou

tcomes

assoc

ia

ted

w

i

th

hosp

i

ta

l

iza

t

ion

Hospitalization has been suggestedto be a majorriskfactorfor older persons.

Normal ageingis associated with declinesinthe muscles andlungs and

reduced bone density, among other consequences(Dehlin & Rundgren, 2014).

Hospitalization and bed rest may increasethe occurrence ofthese age-related

changes andleadtoirreversiblefunctional decline and a substantial andrapid

loss of muscle strength and endurance in the legs(Creditor, 1993;

Paddon-Jonesetal., 2006). Specifically, hospitalizationscanleadto a declinein

Capezuti, Shabbat, & Hall, 2010; Gill, Gahbauer, Han, & Allore, 2009;

Lafont, Gérard, Voisin, Pahor, & Vellas, 2011; Ouslander, Weinberg, &

Phillips, 2000). Some patients spend 80 % oftheirtimein bed during

hospitalization (Brown, Redden, Flood, & Allman, 2009), which is a major

reason for functional decline. A study conducted in the U.S. on 12 healthy

volunteers(mean age, 67 years) hasrevealedthat muscle mass, knee extension

strengthand muscle proteinsynthesis decrease by 6 %, 15 %and 30 %,

respectively, after 10 days of bedrest(Kortebein, Ferrando, Lombeida, Wolfe,

& Evans, 2007). Theseresultsshould be comparedtoresultsfrom communi

ty-dwelling older adults, wholose approximately 3-4 % of knee extension

strength each year(Goodpaster et al., 2006). These negative consequences are

oftentheresult of complications not relatedtothe cause of admission ortothe

specifictreatment. A recent European study has revealedthatthe presenting

conditionisthe cause of a declinein ADL during hospitalizationinlessthan

half of cases (Sourdet et al., 2015).

Functional decline during hospitalization has been found to decrease

functionalrecovery andincreasetherisks of morbidity and mortality (Boyd et

al., 2008). NHRs and older persons using home help services are at

particularly highrisks offunctional decline during hospitalization because

they are more often frail and have multi-morbidity (S. M. Friedman,

Mendelson, Bingham, & McCann, 2008). The declinein function after

hospitalizationincreases withincreasing age, polypharmacy, andthe presence

of multiple comorbidities, impaired cognition, delirium, and depression

(McCusker, Kakuma, & Abrahamowicz, 2002; Volpato et al., 2007). In

addition, deliriumisacommoncomplication of hospitaladmissionamong

older persons(Inouye, Schlesinger et al, 1999). The pathophysiology of

delirium is not clear but probably involves the influences of stressor events,

such as exposuretothe hospital environment, on a vulnerable patient group.

The hospitalenvironmentand particularlythe ED, whichis oftenthefirst

department visited byindividuals seeking hospital care, are often designedfor

the effective care of acutely ill individuals. However, this environment

unintentionally promotes the development of delirium. In addition, delirium

contributesto morbidity and mortality andis associated with anincreasedrisk

of developing dementia. However,thereasonfortheassociation between

delirium and dementiais not clear (Inouye, Schlesinger, & Lydon, 1999).

A further risk factor of hospitalizationisthe danger of developing a hospita

pneumoniaarethe mostcommon hospital-acquiredinfectionsin Swedish

hospitals. Accordingto one study,thelength of hospital stay istwice aslong

for patients with a hospital-acquiredinfection (National Board of Health and

Welfare, 2015b). No intervention aimed at reducing unnecessary

hospitalizations has achieved success thus far. Instead, studies have focused

onidentifying patients who can betreated at alowerlevel of care by

identifying diagnosesthatshould be handledinan outpatientsetting,i.e.,

ambulatory care-sensitive conditions (ACSCs), also termed avoidable

hospitalizations.

Ambu

la

tory

care-sens

i

t

ive

cond

i

t

ions

Avoidable hospitalizationsincludethose relatedto diagnosesthat should not

require hospital care, for example, anaemia, asthma, diabetes, CHF,

hypertension, angina pectoris and COPD. In Sweden in 2014, ACSCs

accounted for over 100 000 care days in hospitals; the most common

diagnoses were CHF, COPDand pyelonephritis(National Board of Health

and Welfare, 2014c)(Table 2).

Table 2. Number of avoidable hospitalizationsfor persons aged 65 and above

in Swedenin 2012(National Board of Health and Welfare, 2013a).

Diagnoses Number of hospitalizations

Congestive heartfailure 30 608

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 19 522

Pyelonephritis 19 031

Angina pectoris 13 024

Epileptic seizures 4859

Hypertension 3561

Diabetes 3340

Diarrhoea 3081

Ear, nose andthroatinfection 2213

Anaemia 2208

Asthma 1117

Gastric ulcer 1090

The ACSCrateis knownto be higher among persons aged 65 years and above.

International studies have reported that common reasons for avoidable

hospitalization are deficiency of andlack of continuityin primary care

(Cheng, Chen, & Hou, 2010; Menec, Sirski, Attawar, & Katz, 2006; Mytton

et al., 2012).

Inrecent years, criticism has arisenregardingthe content, meaning and choice

of diagnoses classified as ACSCs (Anell & Glenngård, 2014; Ljung, 2012).

Researchersand physiciansclaimthatitis difficult orevenimpossibleto

avoid hospitalizations related to ACSCs, and therefore, this classification is

not useful.In Sweden, ACSC diagnoses have beenrevised, andthey have been

reducedin number (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2014c).

Swed

ish

hea

l

th

and

soc

ia

l

care

To understand the findings of this thesis, it is necessary to understand how

health care, home help and social services are organized and providedto older

personsin Sweden.

The Swedish healthcaresystem wasconstructed to ensurethatallcitizens

receive healthcareaccordingtothe principles of human dignity, needand

solidarity,thatis,the personin greatest needis prioritized. Thestateis

responsible for overall health policy, andthe county councils are responsible

for most ofthe hospital care. The municipalities are responsible forthe care

and housing needs of older persons and of persons with disabilities(Anell,

Glenngard, & Merkur, 2012). Medical health care and home help services are

financed primarilythroughtaxation and areregulated bythe Health and

Medical Services Act (SFS 1982:763) and Social Services Act (SFS

2001:453).

Home

he

lp

and

home

hea

l

th

care

serv

ices

Accordingtothe Social Services Act (SFS 2001:453),the municipalities are

responsible for providing publically funded services and help to individuals

regardless of age, health and need of care. Home help services include care

and social services relatedto dailyliving, e.g., personal hygiene and physical

and social needs. Ofthe approximatelytwo million persons aged 65 and older

in Sweden, morethan 250 000(14%)eitherreceive home helpservicesin

those above 80 years of age is 38% (National Board of Health and Welfare,

2013b). Ifthe municipality cannot ensure for a reasonable standard ofliving

and carethrough home care and home health care services, a personis granted

nursing home placement (SFS 2001:453). Among persons aged 65 years and

above, approximately 5%livein nursing homes;the corresponding percentage

ofthoseaged 80 yearsandaboveis 14 %(Swedish Association of Local

Authorities and Regions, 2013).

Home health careincludes medicaltreatment and/orrehabilitation providedin

ordinary housingand in nursing homes. The majority of home healthcare,

long-term care and home help services are provided by staff representingthe

municipalities,andthe minority oftheseservicesare provided by private

providers. Most home healthcareis provided byaregistered nurse(RN).

However, in several municipalities, home health care tasks are delegated to

nurse assistants withless formal competence (SFS 1982:763). Older persons

receiving home help and home health care who live in their own homes can

taketheinitiativetocontacta hospital withoutconsulting withtheir home

health care providers.

Nurs

ing

home

care

Accessto nursing homesis based on needs assessment, with prioritization of

personsin greater need of care. Nursing homes provide basic health care under

the specificinstruction of primary care physicians, who serveas consultants,

as nursing homes do not have physicians stationed attheir facilities (National

Board of Healthand Welfare, 2005). Commonly, physiciansfrom primary

carefacilities visit nursing homes oncea weekand when needs arise. The

decision to transfer an individual from a nursing home to a hospitalis made

by the same consulting physician in agreement with the RN stationed at the

nursing home. As NHRsrepresentthe oldest,frailest, and most diseased group

ofthe elderly population,they frequently use health care services.

Inrecent decades,the number of bedsin nursing homes has decreased,

resultingina higher number of older personslivingin ordinary housing,

indicatingthatthe needfor home healthcareand home helpservices has

increased. Thistrendisinline withthe Swedish policystatingthat older

persons should be supportedinliving at homefor aslong as possible(Ministry

Pr

imary

ca

re

Primarycareand hospitalin-and outpatientcareare provided bycounty

councils and are also based on need. In total, 14 million visits were made to

physiciansat primarycarecentresin 2013,correspondingto 2.7 visits per

inhabitant (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2015d). From an

international perspective, this number is very low; the average stated in the

OECDistwice as high. Sweden has an overall high number of physicians, but

the proportion of physicians working in primary care is very low compared

with other Nordic countries (Sveriges Läkarförbund, 2014). Compared with

other European Union (EU) countries, Sweden is considered to have strong

primary care, meaningthatitis structured,i.e.,thereis an equal distribution

of primary care providers and population coverage for primary care services.

However, accessibility, e.g., the use of an appointment system, provision of

after-hours care, and continuity(doctor-patientrelationship), isratedlowerin

Sweden compared with most countriesinthe EU (Kringos, Boerma, van der

Zee, & Groenewegen, 2013). Normally, primary care centres are accessible

during business hours on weekdays. Duringtheeveningand on weekends,

thereis oftenthe opportunityto seek primary care emergency centres, buttheir

availabilities and accessibilities vary widely among different regions

(Sveriges Läkarförbund, 2014).

Inrecent years,the Act on System of Choice(SFS 2008:962) has been

implemented in the Swedish health care system, giving individuals the

freedomto choosefrom available providers. Afterthereform wasintroduced,

200 new primary care centres opened (National Board of Health and Welfare,

2015d). The National Audit Office has reported that individuals with minor

ailments have made more visitsto physicians afterthe care choicereform was

introduced, while frailer persons have made less visits. In addition, primary

carecentresinsocio-economically disadvantaged urbanareas havefewer

physicians compared with those in resource-rich areas (Riksrevisionsverket,

2014). Despitethereform,the number ofindividualsin permanentcontact

with a physician has notincreased (Riksrevisionsverket, 2014), althoughthe

Health and Medical Services Act 5 § claims that all citizens are entitled to

Hosp

i

ta

l

care

At the end ofthe 1960s, there were 120 000 hospital beds (15.3 beds/1000

inhabitants)in Sweden. Sincethen,the number of hospital beds has decreased

acrossthe country. Atthe beginning ofthe 1990s,

in which the responsibility for elderly carein Sweden was transferredto the

municipalities, was passed. This reform led to a reduction in the number of

hospital bedsto 50 000 because many ofthe departmentsthat had focused on

long-terminpatient health care, primarily for older persons, had closed. From

1999-2008,the percentage of hospital beds decreased by 21 %(National

Board of Healthand Welfare, 2010).In 2013, 25 000 hospital beds were

available, with 2.6 beds/1000inhabitants(National Board of Health and

Welfare, 2015d). The number of acute hospital bedsin Sweden is belowthe

averageinthe EU.

Thecurrent healthcaresystemsin many high-incomecountriesare better

equippedto handleacuteconditionsthanto manageand prevent chronic

conditionsthat are commonin old age(Patterson, 2014).In addition, specialist

care and hospital care often focus on one treatment at a time (Barnett et al.,

2012). The priorities of Swedish politics areto reducethelong waittimes for

diagnosis andtreatment andto decrease differencesin quality of care among

regionsandsocioeconomic groups(Anelletal., 2012).Inline with other

OECD countries,thelength of hospital stay hasfallenfrom 7 days on average,

as it was 10 years ago, to 5.5 days at present (OECD, 2013). This decrease

may partly be explained by not only better and more efficienttreatment

optionsthat do notrequire aslong of a hospital stay as before but also primary

careand municipal healthcarefacilitiesthat provideincreasedamounts of

curativetreatments and after-hours care.

Wa

i

t

ing

t

ime

in

the

emergency

depar

tmen

t

The number of visitstothe EDin Sweden hasincreasedinrecent years andis

currently approximately 2.5 million visits per year. Considerable successful

efforts have been madeinrecent yearsto decreasethe median waittimeinthe

ED (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2014d); however, this decrease

does notapplytoallage groups. For peopleaged 80 yearsand above,the

median wait time is even longer than before. A longer wait time affects the

aged 70 years and above who visitthe ED, 52% are hospitalized, and among

those aged 80 and above, 58 % are hospitalized(National Boardof Health and

Welfare, 2015d). Health problems,especiallyin oldage,are often mult

i-causal and complex. When older persons seekthe ED, physicians haveto be

awarethatthis patient group may have different needsthan younger patients

Andersens

behav

ioura

l

mode

l

of

hea

lth

care

ut

i

l

izat

ion

One ofthe most widely usedtheoreticalframeworksregarding healthcare

utilizationisthe behavioural model of healthcare utilization developed by

R.M. Andersen(Andersen, 1968), which has been usedinseveral studies

(Bass & Pracht, 2006; Bazargan, Bazargan, & Baker, 1998; Condelius, 2009;

B. Friedmanetal., 2013; Lehnertetal., 2011; Näggaetal., 2012; Stein,

Andersen, & Gelberg, 2007; Strain, 1991). The behavioural model (Figure 1)

utilization of health careis a human behaviourthatis

influenced by predisposing factors (socio-demographic factors), enabling

factors (factorsthat support or impede use), the need for health care (illness

level), and health behaviours (factors performed bytheindividual).

The behavioural model focuses on individual of health services

and on outcomesrelatedto health, satisfaction with health care, and quality of

life. The behavioural

utilization of health services during the late 1960s. The original theory was

thatindividual health care useis afunction of demographic, social and

economic characteristics of the family as a unit, and this model could both

predict and explain health care use (Andersen, 1995). Over time, the

behavioural model has been developed and nowalsoincludes contextual

determinants, such as health organization and community characteristics

Figure 1. Theconcepts ofthe behavioural model of healthcare utilization

(Andersen, 1995) (figure modified and drawn bythe author).

Env

ironmen

t

Hea

l

th

care

sys

tem

Andersen hasthoroughly reformulated and revisedthe original model (Aday,

1993; Andersen, 1995; Andersen et al., 2014; Andersen & Newman, 1973),

addingthe environment as a conceptthat affectsthe population characteristics

and outcomes of health care utilization. The environmentincludesthe health

care system, e.g., national health policy, as well as organization ofthe health

care system.

Popu

la

t

ion

charac

ter

is

t

ics

Pred

ispos

ing

charac

te

r

is

t

ics

Predisposing characteristicsrefertoindividualfactorsthat exist priortoillness

and affect hospitalization directly orindirectly. These characteristicsinclude

demographicfactors, such as age and sex, andsocialfactors, such as education

and occupation. Health beliefs,including knowledge, attitude and valuesthat

ofthe need for health care and health service use, are also considered

predisposing factors(Andersen, 1995).

Enab

l

ing

resources

Enabling resources make health services accessible to individuals. Enabling

factorsincludefinancingand organization. Financinginvolves incomeand

insurance, which affect individuals abilities to pay for health care services.

Healthcareservice organization describes whetheranindividualreceives

health care or home help. Socialrelationships also serve as an enablingfactor

that facilitates orimpedes health service use(Andersen 1995).

Need

charac

ter

is

t

ics

Needcharacteristicsareconsideredthe major determinants of healthcare

utilization. Need factors involve both perceived and evaluated health status.

Perceived needis a social phenomenonthatinvolves howindividualsrespond

totheir health problems and health conditions and howtheirresponsesleadto

decisionsregarding whethertoseek medicalcare. Evaluated need involves

healthcare professional judgements

needfor medical care (Andersen, 1968; Andersen & Newman, 1973).

Hea

l

th

behav

iours

Persona

l

hea

l

th

prac

t

ices

Personal health practices refer to activities performed by individuals

themselvesthatinfluences healthstatusandincludetobacco use, dietand

nutrition, exercise and care compliance.

Use

o

f

hea

l

th

serv

ices

According to the behavioural model, the use of health services includes the

numbers of hospitalizations and visits to primary care facilities or the

Ou

tcomes

Consumer

sa

t

is

fac

t

ion

In this model, outcome is defined as consumer satisfaction, and it are

concerned with how persons perceivetheirreceived healthcare. Customer

satisfactioninvolvestraveltime, waittime, communication with providers and

technical care received. Centraltothe behavioural model are feedbackloops,

which showthat outcomes affect predisposing factors,the perceived needfor

services, and health behaviours (Andersen, 1995).

Inthisthesis,the behavioural modelis usedto describe and understand how

predisposing, enabling and need characteristics, as well as health behaviours

andthe environment, arerelatedto hospitalization among older personsliving

The

act

ive

age

ing

po

l

icy

framework

Accordingtothe WHO, health and social care systems shouldfocus on health

promotion and disease prevention and promote accessto high-quality primary

andlong-term health carethatis accessible and agefriendly and addressesthe

needs of people as they age (World Health Organization, 2015). The active

ageing policy framework developed by the WHO in 2002 was meant to be

implementedin health policy documents worldwide. Active ageingis defined

as

securityin orderto enhance quality oflife and aimsto promote

healthyliving and quality oflife for all persons,including frail and disabled

persons and thosein need of help (World Health Organization, 2002).

Accordingtotheactiveageing policyframework, health policies needto

achieve a balance between support for self-care,informal support and formal

careincludedin healthandsocialservices. The WHO hassuggestedthat

health care professionals may need more knowledge and practice regarding

how to recognize older persons individual strengths and how to encourage

themto usetheirstrengthsto maintain independence, whichis particularly

important whentheir caretakers areill,frail or notfeeling well (World Health

Organization, 2015).Intheactiveageing policyframework,a number of

determinants, i.e., economic, behavioural, personal, social, health and social

services and the physical environment, have been suggested to be related to

andto promote active ageing(Figure 2). Moreresearchis warrantedto clarify

Figure 2. The concepts ofthe active ageing policy framework (WHO, 2002)

(figure constructed and drawn bythe author).

Active ageingis based onrecognition ofthe humanrights of older persons and

onthe United Nations Principles ofindependence, participation, dignity, care

and self-fulfilment (World Health Organization, 2015). Theterm active

ageing wasadopted bythe WHO duringthelate 1990sand was meantto

communicate a broader message compared with

recognizing factorsthat affect howindividuals and populations age (Kalache

& Kickbusch, 1997). Further, older ownthoughts,argumentsand

abilitiesto seek health care,including hospital care, areimportant knowledge

for promotingactiveageing. Theresults ofthisthesisattempt to provide

further understanding ofthefactorsassociated with hospitalizationandto

Rat

iona

le

As people age, physiological changes occurthat have physical and cognitive

effects. These physiological changes eventually lead to a general decline in

health and anincreasedrisk of development of disease. Alogical consequence

ofthese changes should bethatthose personsin greatest need of health care

receive the most appropriate care, sometimes including hospitalization.

However,the number of diseases or disabilitiesis notthe only marker ofthe

amount of healthcare utilized. Persons mayseek hospitalization withouta

disease and/orillnessthat requires hospital care.

Itis knownthat hospitalization mayresultin anincreasein age-related

changes and lead to irreversible functional decline. Few studies have

examined whether the decline in cognitive function is associated with

hospitalization and,if so, which cognitive domains are particularly affected.

In Sweden, there has been a decrease in the number of hospital beds, along

with a decreaseinthelength of hospital stay. In addition, Swedenisregarded

as havinglow accessibilityto and continuity of primary care compared with

other European countries, which may affect older persons health care

behaviours. Previousresearch hasrevealedfactorsthat arerelatedto and may

increasethe hospitalization risk among older personslivingin different

accommodations. Unfortunately,thisresearch was not conducted on Swedish

older persons, which limits the generalizability, recommendations and

subsequent implementation of the suggested interventions. The reason

underlyingthe needfor hospitalization may varyamong persons, andthe

reason for admissionis not always clear. Few studies have examinedthe risk

factors for hospitalization and how hospitalization affects older persons.

In this thesis, different aspects of hospitalization among Swedish older

persons are explored. Specifically, how development of cognition is

associated with hospitalization and what risk factors are related to

hospitalization among older persons living in differentaccommodations are

analysed,andthereasons why older personsaretransferredto a hospital

The knowledge generatedinthisthesis could be applicable for professionals

interacting with older persons whoare onthe verge ofseeking or needing

hospital care. Further,this knowledge could be usedto guidethe decisions of

A

ims

The overall aim of this thesis was to describe and explore individual

trajectories ofcognitive developmentinrelationto hospitalizationandrisk

factors for hospitalization among older persons living in different

accommodations in Sweden and to explore older persons´ reasons for being

transferredto a hospital.

The specific aims ofthe different studies were asfollows:

To examinethe developmentin cognitioninrelationto hospitalisation

among middle aged and older adults in a population-based

longitudinal study with upto 25 years offollow-up.

To evaluate physical and psychological factors associated with

hospitalizationrisk overtime among nursing home residents.

To describeandcompareindividualcharacteristics of hospitalized,

and non-hospitalized community-living older persons, and to

determine factorsthat affect hospitalization risk overtime.

To explore how older people with a variety of health problems

experience and perceive decisionto seek hospital care whilereceiving

Methods

Des

ign

Inthisthesis, different designs were usedinthefourincludedstudies. An

overview ofeach designis presentedin Table 3. Thestudy designs were

longitudinal, prospective and descriptive, and both quantitative (studies I, II,

and III) and qualitative (study IV) methods were used.

Long

i

tud

ina

l

and

prospec

t

ive

des

igns

(s

tud

ies

I

,

I

I

,

I

I

I)

A longitudinal design can be applied when studying changes over time, and

this approach uses data collected at morethantwotime points(Kazdin, 2002;

Polit & Beck, 2014).In studyI, alongitudinal design was used, with collection

of data on cognitive abilities at upto 8 differenttime points. In studies II and

III, a prospective design was used. A prospective design measures the

presumed future effects of a certain cause. The advantage of using a

prospective design ratherthan a cross-sectional designisthat itis possibleto

establish atime relation between exposure and outcome. In studies II and III,

factors associated with hospitalization risk over time were analysed by

comparing participants who did and did not experience hospitalization.

Exp

lora

t

ive

descr

ip

t

ive

des

ign

(s

tudy

IV

)

In study IV, an explorative descriptive design was usedto examine how older

personsreceiving home health care experience and perceivetheir decisionsto

seek hospital care. An explorative designis used when a phenomenon is not

well understood and whenthe design can shedlight on underlying processes

Table 3. Overview ofthe four different studies.

Study Design Sample Data collection Data analyses

I Longitudinal

Quantitative 828olde mr peiddrsonsle-agedin and

varied housing

In-persontesting,

Registers Lacurvetent ana growlysesth

II Prospective

Quantitative 429residen nursts ing home JournaIn-personls testing, Coxhazards propo modertionall

III Prospective

Quantitative 772olde mr peiddrsonsle-agedin and

ordinary housing

Self-reported

questionnaires,

Registers

Cox proportional

hazards model

IV Descriptive

Qualitative 22pat homeients health care Indintervividuaiewsl Quaconltenitattive analyses

S

tud

ies

inc

luded

in

the

quan

t

i

ta

t

ive

s

tud

ies

(

I

,

I

I

and

I

I

I)

Thisthesisincludestwolongitudinalstudies, The Swedish Adoption/Twin

Study of Ageing(SATSA)and The Study of Healthand Drugsin Elderly

Livingin Institutions (SHADES).

The

Swed

ish

Adop

t

ion

/Tw

in

S

tudy

o

f

Age

ing

(SATSA)

SATSAis a population-basedlongitudinal study. The participantsin SATSA

were drawnfromthe Swedish Twin Registries(STR)(Lichtenstein, Floderus,

Svartengren, Svedberg, & Pedersen, 2002) andincluded same-sex twin pairs

reared both together and apart. In brief, SATSA was initiated in 1984 when

thefirst questionnaire (Q1) was sent outto a sub-sample ofthe STR, withthe

aim of studying the aetiology of individual differences in ageing (Finkel &

Pedersen, 2004). The responserate for Q1 was 70.7%.In 1986,twin pairs

aged 50 years and above who bothresponded and participatedin Q1(N=2072)

were invited to participate in in-person testing (IPT), which included

the first IPT. Sincethen,twins who participatedin Q1turning 50 have been

askedto participatein IPTs upto IPT5. Intotal, 859individuals have

participatedin atleast one IPT, and 2211 have completed atleast one

questionnaire(Figure 3). TheIPTs were conducted bytrainedresearch nurses

at primarycarefacilitieslocatedclosetothe participants homes orinthe

own homes.

Figure 3. Overview of SATSA.

The S

tudy o

f Hea

l

th and Drugs

in E

lder

ly L

iv

ing

in

Ins

t

i

tu

t

ions

(SHADES)

SHADESis alongitudinal study conducted from 2008-2010. Eleven nursing

homes in three different municipalities in Sweden participated in this study.

The original aim of SHADES was to study mortality, morbidity, nutritional

status,and pharmaceutical treatment among older NHRs(Ernsth Bravellet

al., 2011). The participating nursing homesincluded 30 general departments

andten departmentsfocused on dementiacare. Allresidentslivinginthe

participating nursing homes wereinvitedto participatein SHADES. Among

theinvited persons (N=443), 89 residents ortheir relatives did choose notto

participate, and 49 were excluded dueto severeillness or palliative care. An

additional 11 persons were excluded due to language problems and hearing

difficulties,and 5 wereexcludedforan unknownreason. During thetime

betweenthe provision of consent bytheresidents andthe start ofthe study, 18

persons died. Atotal of 268 NHRs participatedinthe first assessment

(participation rate, 61%). The participants were examined every six months

s of drugs used, biomarkers, and social visits

andstafflevelsatthe various nursing homes. Participants who endedtheir

participation duringthe study either dueto death(n=193), migration(n=7), or

refusal (n=4) were replaced by new residents enteringthe nursing home who

provided consent (Figure 4). Intotal, 429 persons participated in atleast one

assessment wave.

Figure 4. Overview of SHADES.

Par

t

ic

ipan

ts

and

da

ta

co

l

lec

t

ion

An overview ofthe participantsincludedin studies I-IVis shownin Table 4.

Table 4. Participantsin studies I-IV.

Study Total N Mean age at

baseline (range) Gender(female) Housing

I 828 63.1 (50-86) 59.3 % Ordinary housing

and nursing home

II 429 85.0 (65-101) 70.9 % Nursing home

III 772 69.7 (46-103) 59.8% Ordinary housing

IV 22 83.1 (66-93) 68.2 % Ordinary housing

with home health

S

tudy

I

In study I,twins who had participatedin atleast one IPT wave from IPT1-8

in SATSA wereincluded. Participants who did not have completedata on all

four cognitive domains assessed (i.e., memory, verbal, spatial/fluid and

processing speed abilities) were excluded (n = 31), and atotal of 828

participants were ultimately included in the study. The exclusion of

participants was performedto ensurethatthe same sample size (N) was used

and the same individuals were assessed in all analyses. Data on

hospitalizations werecollectedfromthe NationalIn-patient Register. The

participants first hospitalizations after their inclusionin SATSA, regardless

ofthecause, wereincluded. Twins with hospitaladmissions beforetheir

inclusionin SATSA, but not after or duringtheir participation, wereregarded

as having no hospital admission. Of 828twins, 735 had atleast one hospital

admission duringtheir participationin SATSA.

S

tudy

I

I

Study IIincluded atotal of 429 participants (70.9 % women; mean age, 85.0

years) from SHADES. Data were collected by trained research nurses inthe

stated nursing homes. The participants psychological and physical statuses

were assessed using standardized procedures and well-established tests and

scalesand were based oninformation obtained usingcaregivers as proxy

drugs was collected fromthe hospital medical records. In addition,the

research nurses measured s and heights and collected

bloodsamples(Ernsth Bravelletal., 2011). Theresearch nursesextracted

hospitalization dates and reasons for hospitalization during the study period

from the nurses documentation at the nursing homes and from the hospital

medical records.

S

tudy

I

I

I

Thefifth questionnaire(Q5)in SATSAthat was sent outin 2003 (N=794) was

usedasthe baselineforstudyIII. All participants werelivingin ordinary

housing (N=772). Participantslivingininstitutions were excludedto obtain a

more homogeneoussample. Q5 containeditems about health,social and

psychological factors. The study sample was created bylinking the datafrom