Sustainable leadership

in Swedish fashion brands

Understanding sustainability and its challenges

Master’s Degree Project

Thesis within: Business Management Number of credits: 30 ECTS

Author: Olle Lilja

Jönköping: December 2020 Tutor: Elvira Ruiz Kaneberg

2

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my deepest thanks to all the special individuals who have helped me in conducting this research. Your support and guidance have been invaluable for the completion of this thesis. Special thanks to my tutor, Elvira Kaneberg, who provided guidance and critical feedback in the direst of times. Through trial and error, you never lost faith in me and for that I am very grateful. Additional thanks to my examiner Adele Berndt who provided additional feedback that helped me finalize this thesis.

Furthermore, I thank the two very competent, humble, and intelligent students in my seminar group who provided me with input and suggestions for improvement.

Additionally, I sincerely thank all the participants and organizations who agreed to be interviewed for this thesis. Even in times of a turbulent world you took the time and energy to share your insights and experiences. Without you this thesis would never have seen the light of day.

Lastly, I want to thank my friends, family, and loved ones for your support throughout this journey. It has been a long and painful process, and without you I would never have made it.

Thank you,

Olle Lilja

3

Master Thesis in Business Management

Title: Sustainable Leadership in Swedish fashion brands: Understanding sustainability and its challenges

Author: Olle Lilja

Tutor: Elvira Ruiz Kaneberg Date: December 2020

Abstract

Background: The clothing industry is a significant contributor to Earth’s pollution, depletion,

and exploitation. Businesses need to become sustainable, to find long-lasting solutions where economic, social, and environmental value is created. This has birthed a new form of leadership, sustainable leadership, that puts ethical behavior and the common good above the untrammeled pursuit of profit. Business leaders must transform the way they do business, which requires changes in leadership.

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to, from a leadership perspective, describe and create an

understanding of how Swedish fashion brands are changing their business to become sustainable and remain competitive, and of sustainable leadership. Specifically, by exploring how business leaders work with sustainability and the challenges they face.

Method: This study follows a qualitative research method and an abductive approach.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with CEOs and sustainability managers. Secondary data was gathered from sustainability reports.

Findings: The organizations have made changes to their business models. Business leaders

face several challenges, such as issues of maintaining quality, consumer behavior discrepancy, lack of control over suppliers, and insufficient technology. Leaders were found to show practices of sustainable leadership to remain competitive and sustainable.

Conclusion: This study concludes that organizations take different strategical approaches to

remain sustainable and competitive. Business models Leaders must create long-lasting stakeholder relationships, a supportive company culture, set clear goals, and develop employees to be successful in sustainability work. New developments in recycling technology and increased consumer awareness are called for to further drive an increased sustainable development in the industry.

4

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 9 1.1 Research Background ... 9 1.2 Research Problem ... 10 1.3 Research Purpose ... 11 1.4 Research Questions (RQ) ... 11 1.5 Delimitations ... 12 1.6 Key Concepts ... 13 2. Theoretical Framework ... 152.1 The clothing industry ... 15

2.1.1 Challenges with sustainability ... 16

2.2 Sustainability ... 18

2.2.1 The Triple Bottom Line (TBL) ... 18

2.2.2 Corporate social responsibility (CSR) ... 19

2.2.3 The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals ... 20

2.2.4 The profit issue ... 21

2.2.5 Sustainability-Oriented Innovation ... 21

2.2.6 Sustainable Business Models... 24

2.3 Leadership & Sustainable Leadership ... 26

2.3.1 Transformational Leadership ... 27

2.3.2 Transactional Leadership ... 28

2.3.3 Sustainable Leadership ... 28

2.4 Linking of theory model ... 35

3. Methodology ... 37 3.1 Research Philosophy ... 37 3.2 Research Design ... 38 3.3 Qualitative Research ... 40 3.4 Sampling Strategy ... 41 3.5 Data Collection ... 44 3.5.1 Primary data ... 44 3.5.2 Secondary data ... 46 3.5.3 Search process ... 48 3.5.4 Outline of interviews ... 49 3.6 Data analysis ... 50 3.6.1 Interviews ... 50 3.6.2 Documents ... 52

5 3.7 Trustworthiness ... 53 3.8 Ethical considerations ... 54 4. Findings... 56 4.1 Perceptions of Sustainability ... 56 4.2 Interview 1... 57 4.2.1 Actions ... 57 4.2.2 Challenges ... 60 4.2.3 Leadership/Management ... 61 4.3 Interview 2... 63 4.3.1 Actions ... 63 4.3.2 Challenges ... 67 4.3.3 Leadership/Management ... 69 4.4 Interview 3... 72 4.4.1 Actions ... 72 4.4.2 Challenges ... 75 4.4.3 Leadership/Management ... 75 4.5 Interview 4... 77 4.5.1 Actions ... 77 4.5.2 Challenges ... 80 4.5.3 Leadership/Management ... 81 4.6 Interview 5... 83 4.6.1 Actions ... 83 4.6.2 Challenges ... 87 4.6.3 Leadership/Management ... 89

4.7 Secondary data findings ... 91

4.7.1 Partnerships and initiatives ... 91

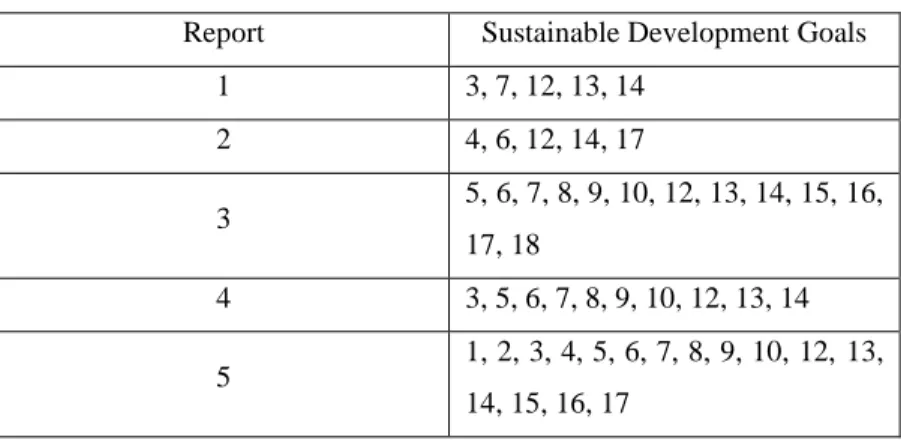

4.7.2 Sustainable Development Goals ... 92

4.7.3 Sustainability-Oriented Innovation ... 92

4.7.4 Sustainable business models ... 93

4.7.5 Challenges ... 93

4.7.6 Leadership ... 94

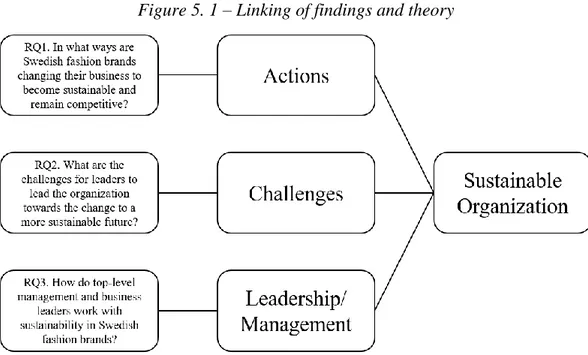

5. Analysis... 95

5.1 Empirical themes and theoretical framework... 95

5.2 Actions ... 96

5.2.1 Business responsibility ... 96

5.2.2 Partnerships and initiatives ... 98

6

5.2.4 Stakeholder relationships ... 102

5.2.5 Creating value ... 104

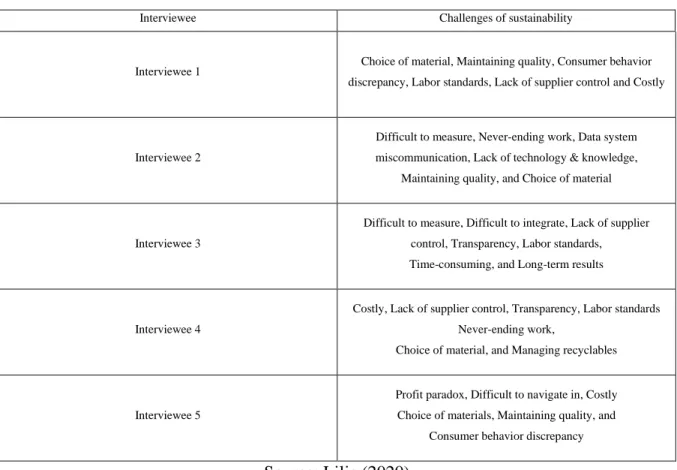

5.3 Challenges ... 106

5.3.1 Transparency and data system miscommunication ... 106

5.3.2 Materials, quality, and time ... 107

5.3.3 Consumer behavior discrepancy ... 110

5.3.4 Labor standards... 111

5.4 Leadership/Management ... 113

5.4.1 Behavior... 113

5.4.2 Strategies ... 118

6. Conclusions, Implications, and Future avenues ... 121

6.1 Conclusions ... 121

6.2 Implications ... 123

6.2.1 Implications for practice ... 123

6.2.2 Implications for research ... 123

6.2.3 Ethical implications ... 124

6.3 Limitations and Future research ... 124

Reference List ... 127

7

List of figures

Figure 2. 1 – The 17 Sustainable Development Goals... 20

Figure 2. 2 – Leadership elements SL and SFL. ... 31

Figure 2. 3 – 23 sustainable leadership practices ... 31

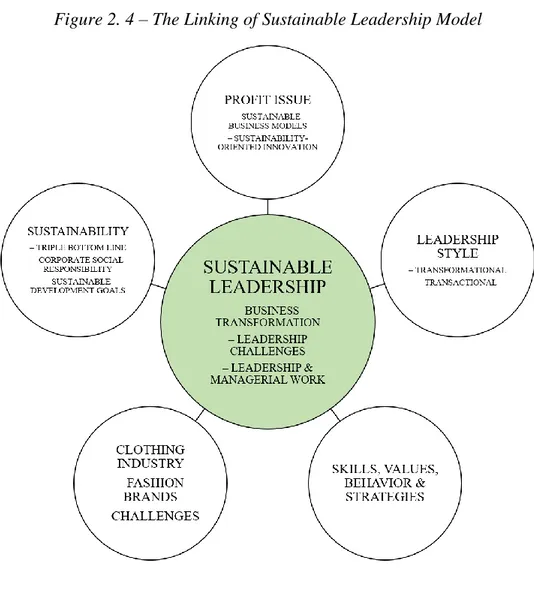

Figure 2. 4 – The Linking of Sustainable Leadership Model ... 35

Figure 5. 1 – Linking of findings and theory ... 95

List of tables

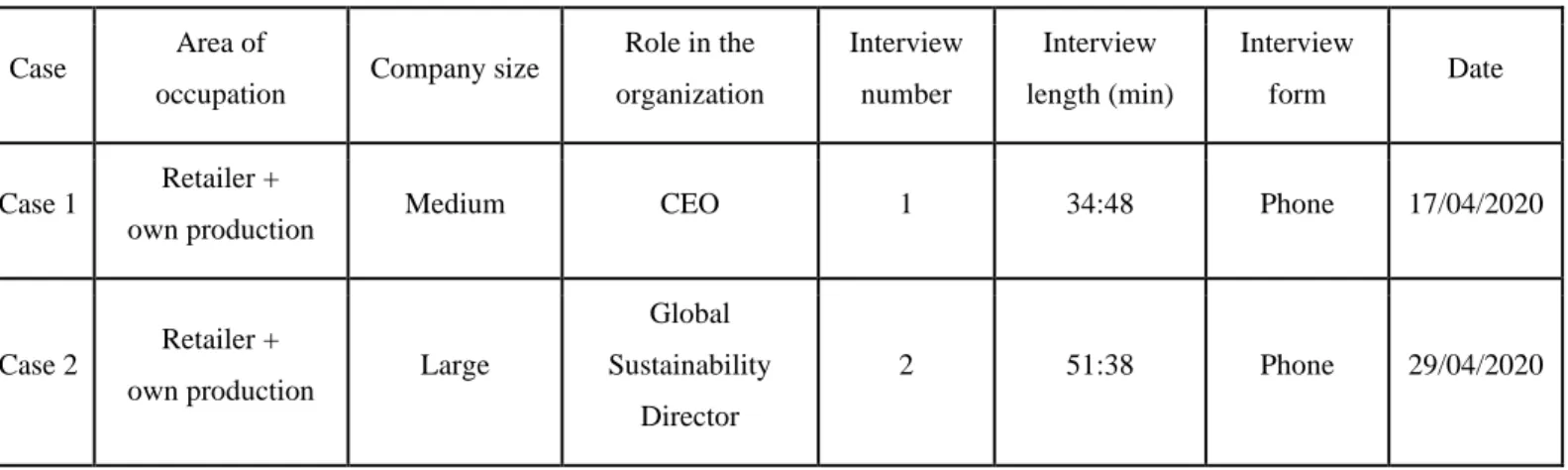

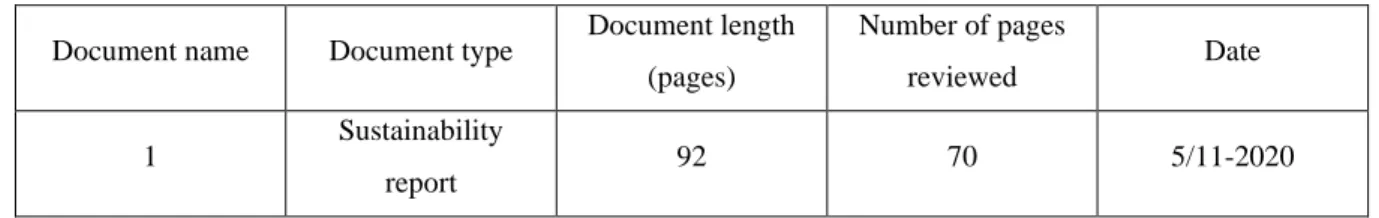

Table 3. 1 – Summary of interviews ... 43Table 3. 2 – Summary of documents ... 47

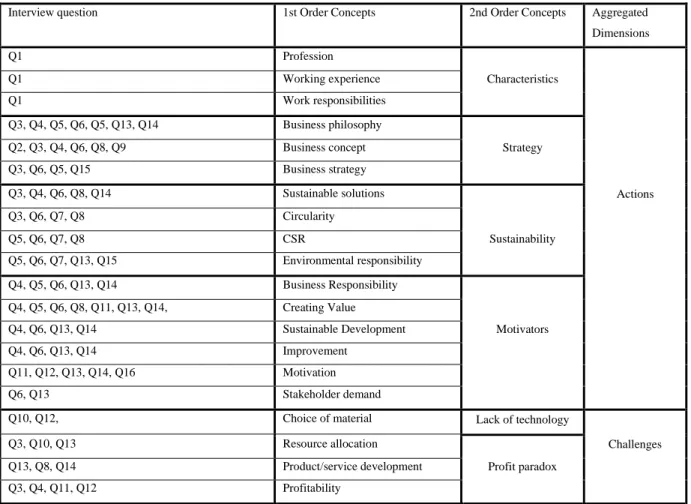

Table 3. 3 – Coding Scheme ... 51

Table 4. 1 – Overview of the SDGs ... 92

Table 5. 1 – Summary of perceived challenges ... 106

Table 5. 2 – Summary of perceived important values and skills ... 113

Appendices

Appendix A - Consent form ... 1358

Abbreviations

CSR Corporate Social Responsibility TBL Triple Bottom Line

CEO Chief Executive Officer HoS Head of Sustainability SM Sustainability Manager SL Sustainable Leadership SFL Shareholder-first Leadership KPI Key Performance Indicator UN United Nations

SDG Sustainable Development Goal SAC Sustainable Apparel Coalition

UNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change UNGC United Nations Global Compact

WWF World Wide Fund for Nature

9

1. Introduction

In this section, the reader is introduced to the research topic through the background, problem, and research questions. The research is also outlined in the delimitations section. In the last section, three key concepts that are central to the study are defined.

1.1 Research Background

One of the most significant contributors to pollution, depletion, and Earth’s exploitation is the clothing industry (European Commission, 2020). Today our society is faced with a seemingly apocalyptic problem, namely the abnormal acceleration of climate change. The unsustainable ways of living and conducting business that has been prominent in the last century have led to our civilization depleting the Earth from its natural resources faster than they are produced. Historically, companies have had a narrow focus just to accomplish profitability, and little concern has been given to the adverse outcomes this has had on our planet and people. Elkington (1994) proposed already 20 years ago, a triple-bottom-line (TBL) approach to sustainability. Sustainability has since then suggested that people, planet, and economic outcomes should all be of equal concern to businesses (Carbo et al., 2014). Many organizations could do better and become more sustainable. Ever since the first meeting of the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) in 1987, sustainable development has been a dominant industry trend (Barkemeyer et al., 2014).

Developing more sustainable practices is a major challenge for the clothing industry. As this is an industry involved in using large amounts of chemicals, water, and energy when producing new clothes, and as the world’s population is expected to increase by 35% in 2050, the demand for clothing will increase (Hasanbeigi & Price, 2015). The increased public interest in seeing changes in the clothing industry, to rethink their strategies, and think more in the long-term has put pressure on companies. Companies must change their ways to find new long-lasting solutions that can both increase their position in the market while also maintaining profits. However, in paving a way forward in uncertain times, there is a lack of understanding of this uneasy task’s complexity.

10

In research, it has been required to shift the focus to the right leadership to be successful (Jackson, 2016). In practice, business leaders have ranked sustainable development, among the top priorities facing the commercial enterprise. Thus, sustainable development is argued to be a crucial aspect in sustaining global economic growth. Indeed, leaders of 21st-century businesses must strategize and implement sustainable development approaches in the next 10 years by transforming the way they do business (Benn, et al., 2018). This is no minor task as it will require wide-ranging shifts in the levels of inspiration, leadership, energies, and skills of societies. If we are to create a sustainable world, we need many more effective leaders. Sustainability has created a new kind of leadership, sustainable leadership, that puts ethical behavior and the common good above the untrammeled pursuit of profit (Burnes, 2017; Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011a). It is necessary for today’s society to develop leaders with the needed capabilities and skills to prepare them to face the changes that comes with sustainability.

1.2 Research Problem

Previous research on sustainability in the clothing industry covers multiple areas. Such as: the environmental damages from the production processes (Madhav et al., 2018), extending the life of garments (Goworek et al., 2020), barriers and drivers of integrating sustainability into the corporate strategy (Peters & Simaens, 2020), different level actions to become more sustainable and responsibility placement (Boström & Micheletti, 2016), sustainable business models (Todeschini et al., 2017), the social management capabilities (SMCs) of sustainability (Huq et al., 2016), environmental management in organizational functions (Luzzini et al., 2018), consumers impact on organizations sustainability efforts (Yang & Dong, 2017), organization’s ethical climates influence on sustainability performance (Lee & Ha-Brookshire, 2017), and organizational values importance for business model innovation (Pedersen et al., 2016).

For Swedish fashion brands to move towards sustainability, previous literature argues for the need of a better overall understanding of how top-level management and business leaders manages sustainability in their organizations (Gerard et al., 2017; Hallinger & Suriyankietkaew, 2018; Karell & Niinimäki, 2020). Additionally, in the context of the Swedish fashion industry, literature is in scarce.

11

The overarching problem is regarding current practices in the Swedish fashion industry. Many business plans today are short-sighted and adopt unsustainable strategies, such as releasing new products with a short life cycle multiple times a year. The challenge for organizations lies in operating in a sustainable way while remaining competitive.

Additionally, the leaders steering organizations’ in the destructive clothing industry play a crucial role in mitigating the organizations’ social and environmental impact. Thus, one of the problems for clothing companies regards the necessary leadership changes for acting towards sustainability. As proposed by previous literature, sustainable leadership could be applied. However, it is necessary to increase the understanding of this type of leadership to enable Swedish fashion brands to become sustainable. A new business paradigm needs to be brought forward, where societal, environmental, and organizational goals need to be aligned if we are to save our health, economy, and environment (Howieson et al., 2019).

1.3 Research Purpose

The purpose of this study is to, from a leadership perspective, describe and create an understanding of how Swedish fashion brands are changing their business to become sustainable and remain competitive, and of sustainable leadership. Specifically, by exploring how business leaders work with sustainability and the challenges they face. This can provide further understanding of how organization’s and business leaders work with sustainability, and by that a deeper understanding of sustainable leadership as a phenomenon.

1.4 Research Questions (RQ)

The following research questions have been developed to meet the purpose of this report: RQ 1. In what ways are Swedish fashion brands changing their business to become sustainable and remain competitive?

RQ 2. What are the challenges for leaders to lead the organization towards the change to a more sustainable future?

RQ 3. How do top-level management and business leaders work with sustainability in Swedish fashion brands?

12

1.5 Delimitations

Research topic delimitations

The subject of leadership covers seemingly endless ways of how different leaders lead and behave the way they do. As explaining every one of them would be too time-consuming, this study narrows leadership down to only explaining its application to sustainable improvements in the clothing organizations. The theory of organizational leadership is, therefore, providing a general background to the framing of the area of leadership from theory relevant to the research problem and questions. The theories of transformational and transactional leadership are also included to provide the analysis with more comparing elements. As organizations are complex systems with many variables, a narrow view of leadership in relation to management has been chosen to prevent an overload of work and information.

Theory delimitations

Sustainable leadership is a broad concept with multiple definitions. Thus, only the elements of sustainable leadership applicable to the aim of this study will be analyzed. Sustainable leadership can refer to the practice of developing leaders and employees in a sustainable way, to reduce burnouts and employee turnover (Casserley & Critchley, 2010). This concept has been left out to remain relevant to the aim of this study. In this study, sustainable leadership applies to leaders’ practice to develop and lead an organization towards sustainability in the context of environmental, social, and economic aspects, as argued by Avery and Bergsteiner (2011a). In other words, how leaders can reduce the harm their organization has on the planet and its people while remaining profitable as a business.

Industry delimitations

The clothing industry is a large industry with a large variety of products. For this study, the focus is on companies specialized in a diverse range of products to end consumers. That is, from ready-to-wear, denim, accessories, eyewear, and footwear. Most, but not all, of the companies belong in the higher price range. This study leaves out companies that produce various textiles for Business-to-Business (B2B) and instead examine companies that focus on Business-to-Consumers (B2C). The motive behind this decision was to narrow down the field of study, ease accessibility for potential companies to interview (as there are more B2C organizations than B2B in Sweden), and because B2C organizations felt more interesting to study from a management perspective.

13

Geographical delimitations

Furthermore, a delimitation of this study is that only Swedish organizations are studied. However, the intent of this is to draw some conclusions specific to the Swedish context. Additionally, only one individual was interviewed at each company. By interviewing more individuals at different positions, the empirical findings could have given a broader perspective on leadership matters. As such, different perspectives were not taken into consideration.

1.6 Key Concepts

Sustainability

Sustainability in this study refers to the desired outcome of sustainable development. Sustainable development is defined as “Sustainable development is the development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability for future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED, 1987). Sustainability is closely connected to the concept of the triple bottom line (TBL), which not only measures an organizations financial aspect, but the social and environmental impact of the firm as well. These are referred to as the three P’s, profit, people, and planet (Elkington, 1994). Sustainability means planning for the long-term, to reject practices that threaten the lives and well-being for future generations of all life on Earth (Caradonna, 2014).

Sustainable Leadership

In this study, Sustainable leadership is defined as “leadership that requires long-term perspective in decision making, fostering systematic innovation to increase customer value, developing a skilled, loyal, and highly engaged workforce, and offering quality products, services, and solutions” (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011a). The concept of this leadership is to keep people, profits, and the planet in balance over the life of the firm. Furthermore, it includes all stakeholders, society, and culture in planning short- and long-term objectives.

Fashion brand

The organizations in this study are both retailers and producers operating in the clothing industry. As the industry concerns various forms of textiles, from yarn and fabrics to household textiles to ready-to-wear items, a clarification of the concept is necessary to avoid confusion. In this study, fashion brand entails multiple definitions. It is referred to as “the

14

clothing/apparel/fashion industry concerns the production and life cycle of garments, shoes, bags, and other accessories” (Jacometti, 2019). Not included in the definition is the textile industry, which “mainly concerns the production of yarn, textiles, fabrics, household textiles, and industrial textiles” (Jacometti, 2019).

Additionally, fashion brands are characterized by their practices of designing, sourcing, and marketing garments (Hvass & Pedersen, 2019). A fashion brand is hence defined as an organization that both retail and produce its own fashion products.

Company size

A large-sized company has more than 250 employees (Tillväxtverket, 2020). A medium-sized company has between 50-249 employees.

15

2. Theoretical Framework

The purpose of this chapter is to give the reader an understanding of the research topic and context. The studied literature provides a foundation on which the analysis in Chapter 5 is made. Sustainable Leadership is the most important topic for the discussion and analysis further in the study.

2.1 The clothing industry

Being the world’s third-largest manufacturing sector, the global clothing industry is valued to around USD 2,4 billion, offering jobs to over 75 million people (Worldbank, 2019).

The production of clothes accounts for 10% of global carbon emissions, which is more than all international flights and maritime shipping combined (UNEP, 2018). If this pace continues, carbon emissions are expected to rise by 50% in the year 2030 (Worldbank, 2019).

Many pesticides and insecticides are used in growing cotton and treating cotton require mass amounts of water (Claudio, 2007). While cotton farming uses 3% of the world’s farmable land, it is responsible for 24% of insecticides and 11% of pesticides used in the world (UNECE, 2018). It takes around 2700 liters of water to make a single cotton shirt and more than 7500 liters of water to produce a typical pair of jeans (UNECE, 2018; UNEP, 2018).

The manufacturing of synthetic materials such as polyester is an energy-demanding process that requires large amounts of unrefined oil, releasing various emissions such as volatile organic compounds, particulate matter, and acid gases such as hydrogen chloride (Claudio, 2007). All these can harm one’s health and can cause or worsen respiratory diseases. Further, waste such as volatile monomers, solvents, and other by-products from the manufacturing and washing of polyester items ends in wastewater.

Globally, textile dyeing is the second-largest polluter of water, and the fashion industry accounts for 20% of global wastewater (UNEP, 2018). The washing of clothes releases half a million tons of microfibers into the world’s oceans annually (UNEP, 2018). These microfibers are so small that they cannot be removed from the water and, thus, can spread upwards the food chain (Worldbank, 2019).

16

Compared to 2000, today’s average consumer purchases 60% more clothing items while each item is kept for half as long time. Further, an average of 40% of people’s wardrobes is never used (UNECE, 2018).

Additionally, 85% of the total fiber input used in clothing is either incinerated or ends up in a landfill (Worldbank, 2019). It is estimated to amount to 21 billion tons every year (UNECE, 2018).

Lastly, workers in textile producing factories are often massively underpaid and are forced to work long hours in dreadful conditions (UNEP, 2018). In some cases, modern slavery and child labor are tied to production facilities (UNECE, 2018).

Parts of the industry is moving towards more environmentally friendly alternatives, by using recycled materials and plant-based materials. Recycled materials include recycled cotton, which can save up to 20,000 liters of water per kg of cotton, and recycled plastics from plastic bottles (Claudio, 2007). Examples of plant-based materials are polymers produced from corn by-products and shoes created from algae (Claudio, 2007; UNEP, 2018). These materials are spun into fibers and then woven into fabrics used in garments.

New steps are taken towards more sustainable technology and production methods combined with initiatives to increase consumer awareness regarding clothes’ life cycles (Claudio, 2007). These are two areas the industry works with to have a bigger impact on sustainability.

2.1.1 Challenges with sustainability

There are several challenges connected to the readjustment to practicing suitability in the textile industry. Specifically, recent research focuses on the readjustment to a circular economy, which is in accordance with the Sustainable Development Goal 12, responsible consumption, and production (United Nations, 2020b).

Sandvik and Stubbs (2019) identifies four technical inhibitors of circular supply chains: separation of blends, separation of additives and trims, restoring quality and the need for all processes to be sustainable. Pal et al. (2019) refers to this as technological unreadiness. Blends are garments that contain different materials, such as cotton and polyester (Sandvik & Stubbs, 2019). Due to blends having more than one material, the recycling process is done with different methods. The separation of blends is a difficult challenge as blends can be good for

17

durability and quality of the products. For sorting practices to work, there must be transparency about product content.

The restoring quality regards to the fact that fibers are degraded during the disassembling process but also as fibers degrade with consumer usage (Sandvik & Stubbs, 2019). Additionally, most textile-to-textile recycling today only allows for downcycling, making recycling less lucrative.

The need for all processes to be sustainable includes environmental and economic aspects (Sandvik & Stubbs, 2019). Recycling practices must cost as much or less than current practices do and, resource usage and emissions must not exceed that of current practices. Current practices are conducted manually, which makes them highly expensive. Another economic inhibitor is the cost to develop new technology and the cost of sorting practices. To develop new technology, more research is also called for. Furthermore, another technical barrier concerning recycling and production is the water and energy consumption involved in such practices (Franco, 2017).

To counteract some of the mentioned challenges, it is important to consider sustainability already in the design stage, especially when choosing the materials (Sandvik & Stubbs, 2019; Franco, 2017; Pedersen et al, 2019).

Furthermore, to be sustainable a readjusting of the entire supply chain, is necessary, a complex matter which is also considered an inhibitor (Sandvik & Stubbs, 2019). This strategic misalignment (Pal et al., 2019) refers to different paces of firms along the supply chain (Sandvik & Stubbs, 2019), and different strategy and goals (Hvass & Pedersen, 2019).

Additionally, while consumers have positive attitudes towards pro-environmental behavior, they do not act in accordance with their attitudes (White, 2019). There is a discrepancy between what consumers say and do, which is referred to as the “attitude-behavior gap”. The current consumer unacceptance is an inhibitor to circularity, as well as the broader concept of sustainability (Pal et al., 2019).

18

2.2 Sustainability

Sustainability first emerged as a social, environmental, and economic ideal in the late 1970s and 1980s and its principles are to create a safe, stable, prosperous, and ecologically minded society. It is argued that since the industrialization of the modern world during the Industrial Era, the natural environment of our planet has been a subject of imbalanced exploitation (Caradonna, 2014). Greenhouse gas emissions (carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide) released from human activities and industries traps the heat emitted from the sun that would otherwise leave the atmosphere. This has caused an increase in global temperature, which in turn has led to a set of multiple negative consequences for Earth’s environment and natural systems. Unpredictable weather conditions, severe droughts, more massive and more frequent storms, rising sea levels, and extinction of species are examples of this (Caradonna, 2014). Additionally, according to Caradonna (2014), the Earth’s production of natural resources cannot keep up with the demand caused by the consumption habits of the over 7 billion people living on this planet. In other words, we extract Earth’s finite resources at a pace as if we had more than one planet to rely on.

The purpose of sustainability is to counterbalance the effects caused by our current economic system, which has drained the world of some of its limited resources, including freshwater and oil. It has also led to the crash of global financial markets, worsened social inequality in parts of the world, and lead society towards a potentially catastrophic future by choosing economic growth at the expense of essential ecosystems and resources (Caradonna, 2014).

Sustainability means planning for the long-term, to reject practices that threaten the lives and well-being for future generations of all life on Earth by instead creating a “green” economy that runs on renewable energy sources.

The statement “We might not live in a sustainable age, but we’re living in the age of sustainability.” (Caradonna, 2014, p. 176) is hard to argue against. Scholars today discuss sustainability in all fields of research. The movement has grown dramatically, and with the introduction of new tools and methods, it has helped define, measure, and assess the concept (Caradonna, 2014).

2.2.1 The Triple Bottom Line (TBL)

The triple bottom line (TBL) presented by Elkington in the ’90s, is a form of ethical business accounting introduced which not only measures an organizations financial aspect, but the social

19

and environmental impact of the firm as well. These are referred to as the three P’s, profit, people, and planet (Elkington, 1994) It is a useful tool when one wants to look if businesses are engaging in environmentally sustainable practices and if it aids in social equality, justice, and the community. The TBL is increasingly being used to promote corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices and a green economy (Caradonna, 2014).

In the business community, the TBL has been an essential tool for organizations that want to rethink and redefine what value they can create towards society. In their book, Sternard et al. (2016) seeks to remind society what the initial goals of business were and how somewhere along the way, these were forgotten. A business should play a key role in society, to provide goods or services that make life easier and better for an exchange of money. What once was an exchange has turned into a sole focus on profitability and shareholder value without much, if any, regard to the value provided to stakeholders (Sternard et al., 2016). All too many corporations disregard the effects that shareholder value maximization has on society and the environment. The intention of the TBL is to replace the view of business as having a single bottom line, namely profits (Sternard et al., 2016).

2.2.2 Corporate social responsibility (CSR)

Corporations have responded by implementing strategies such as CSR. Instead of conducting “business as usual”, CSR’s concept was developed based on the idea that managers and business owners have a moral responsibility towards the society that goes beyond corporate profits. Ethical, environmental, and social considerations for both internal and external stakeholders are the heart of CSR (Benn et al., 2018). Indeed, CSR affects all stakeholders or persons of special interest to the organization (Jackson, 2016). Creating long-lasting and co-operative relationships with all stakeholders is a vital part of a socially responsible organization (Sternard et al., 2016).

According to Benn et al. (2018), while some argue that a focus on CSR practices will decrease corporate profits, organizations can find CSR as beneficial. CSR initiatives such as offering eco-friendly products, reducing the environmental footprint, and launching social initiatives to help communities strengthens the image of doing good, which becomes a strategic advantage. The results can be an increased competitive advantage over industry rivals, which ultimately yields increased profits. CSR programs intend to combine profits and sustainability (Benn et al., 2018).

20

2.2.3 The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

To further drive sustainable development forward on our planet, in December 2015 the United Nations (UN) gathered in Paris to set sustainable development goals (SDGs) and targets to reach by 2030. Also known as Agenda 2030, the goals address the global challenges the world faces today, including poverty, inequality, climate change, environmental degradation, peace, and justice (United Nations, 2020a; United Nations, 2020c). The whole world is facing these challenges and thus, the whole world must cooperate in solving them. Each member country who signed the accord have a responsibility to make changes to their country’s industries and promote change for the goals to be reached. Businesses have responded by joining the initiative and setting their individual goals to meet the SDGs set for 2030, and their progress is seen in annual reports. The 17 SDGs are presented below.

Figure 2. 1 – The 17 Sustainable Development Goals

21

2.2.4 The profit issue

According to Carbo et al. (2014), the profit issue concerns the management of business practices that have been dominant in the last couple of decades (Carbo et al., 2014; Howieson et al., 2019). The focus for business has been solely on profits while giving little or no concern to the effects on the external environment.

This focus on profit has led to the exploitation of workers, consumers, communities, and the environment. Under the current business system, employees, consumers, the environment, and communities are susceptible to exploitation in the name of profit. Corporate power is expanding and has led to a vast array of negative outcomes for society (Carbo et al., 2014). The adverse outcomes of advanced capitalism have been seen around the globe for half of a century. In response to these concerns, the United Nations (UN) developed the Brundtland Commission in 1983 to explore more sustainable development practices.

The Brundtland report in 1983 showed new ways of conducting more sustainable business practices. However, there are clear indications that the original themes embedded in the definition of sustainable development provided by the Brundtland report are not fully reflected in the normative codes of conduct used by, and promoted for, the business community (Barkemeyer et al., 2014).

Creating real value for all stakeholders requires a business to redefine what purpose they can bring to the world and change their business plans accordingly. For if businesses seek to be considered as members of society, driven by purpose while creating real value and meaning, their principles must be incorporated and reflected in their strategy (Sternard et al., 2016). Since corporations have contributed to the problems caused by profit-maximization, they must also be part of the solution (Benn et al., 2018). They need to act as a regenerative force that contributes to our planet’s well-being and has a crucial role in developing a just and humane society while also providing self-fulfilling work.

2.2.5 Sustainability-Oriented Innovation

An emerging concept in sustainability is Sustainability-Oriented Innovation (SOI). It is defined as “Sustainability-oriented innovation involves making intentional changes to an organization’s philosophy and values, as well as to its products, processes or practices to serve the specific purpose of creating and realizing social and environmental value in addition to economic returns” (Adams et al., 2016, p. 180).

22

It is built on the idea that businesses can become or remain sustainable through innovation. This pursuit of achieving sustainable economic growth has received an increased attention from researchers, managers, and policymakers (Adams et al., 2016). Indeed, the response is caused by the realization that changes need to be made in the current economic paradigm to sustain the planet and its resources.

Adams et al., (2016) synthesize existing literature relating to SOI and contributes to the development of a theoretical model. By reviewing the existing literature, they present what SOI entails and identify foundational dimensions and activities of the theory. The purpose of the model is to provide guidance for organizations on becoming and remaining sustainable. Three dimensions of SOI are presented; Technical/people, stand-alone/integrated, and insular/systemic.

Technical/people

Innovation can be technically focused, where adjustments and improvements on products act as a way for businesses to solve environmental issues (Adams et al., 2016). This product-oriented view is the more traditional view of innovation. An additional and more recent perspective is the focus on people-centered innovation, where environmental issues are realized as a socio-technical challenge affecting technology, infrastructure and supply networks, regulation, cultural meaning, and consumer practices and markets. Hence, it considers not only technological aspects, but also how innovations are used, who they involve, and how they promote changes in behavior. This is represented in how some businesses are embracing new business models or replace products with alternate services.

Stand-alone/Integrated

This dimension regards how incorporated sustainability and SOI thinking is in the organization (Adams et al., 2016). If it acts as a stand-alone department or function, or if it is more deeply integrated in the business culture through product lifecycle thinking, integrated environmental strategies, and environmental management systems. In other words, SOI turns from being an add-on activity to a behavior that is seen in the whole organization.

23

Insular/Systemic

The insular/systemic dimension describes how a business view itself in relation to society (Adams et al., 2016). It is reflected in if innovations are internally oriented, designed to address internal issues, or if they are designed to have a broader impact on the socio-economic system. Businesses who are systemic can be seen collaborating with NGOs, governments, and lobby groups or other coalitions to have a wider impact on indirect stakeholders in society. Meanwhile, for example insular businesses’ environmental product development processes are insulated from cooperation with processes outside the business.

Adams et al., (2016) identifies along with the three dimensions of SOI, five activities for SOI. These are presented below:

Strategy: Organizational and managerial processes are aligned to deliver sustainability. Innovation process: The innovation process of the organization to deliver sustainability, from

searching for new ideas to converting them into products and services to capturing value.

Learning: Recognizing the value of new knowledge. Understanding it and applying it to

support sustainability.

Linkages: Internal and external relationships created as opportunities for learning and

influencing around sustainability.

Innovative organization: Organizational work arrangements that create the condition within

which SOI can take place. Such as having enabling structures, communications, training and development, reward and recognition, and leadership.

According to the theoretical model developed by Adams et al., (2016), three levels of organizations can be identified based on the degree of SOI activity implemented. The authors argue that being sustainable should not be an either/or statement. Instead, they argue that it is a process of becoming. Advancing through the levels calls for a step-change in philosophy, values, and behavior, which is displayed in the organization’s innovation activity. Adams et al., (2016) identify three levels of innovation activity in organizations who are in this process of becoming: innovation activities for operational optimization, innovation activities of organizational transformation, and innovation activities of systems building.

Innovation activities of Operational Optimization

Operational Optimization means that a business has an internally oriented perspective on sustainability and have the “doing the same things but better” mentality (Adams et al., 2016).

24

Defined as having characteristics of being technical, stand-alone, and insular, these organizations reduce environmental harm by making conscious and continuous improvements. Drivers are either by compliance to laws and regulations, or the desire to always seek efficiency.

Innovation activities of Organizational Transformation

Organizational Transformation is symbolized by a shift in mindset and purpose, going from organizations “doing less harm” to “doing good by doing new things” (Adams et al., 2016). This is achieved through creating shared value and bringing wider benefits for society. Additionally, social, and environmental impacts are increasingly considered when dealing with internal and external relationships. Furthermore, characteristics of the activities are more people oriented, more deeply integrate sustainability throughout the organization, and are less insular. Lastly, the organization remains internally oriented at large, a sustainability mindset is present but not too widely spread, however it extends to the most direct stakeholders.

Innovation activities for Systems Building

Activities at this level require a radical shift in philosophy, organizations move to think beyond themselves and reassess their purpose as a business to society (Adams et al., 2016). “Doing good by doing new things with others” where relationships are the most crucial SOI activity. Instead of being isolated, value creation is achieved collaboratively, where competition can turn into collaboration in the pursuit of innovations that reshape systems. Indeed, it has the potential of shaping a city, a sector, or an economy onto a more sustainable path. Characteristics of these activities are heavily people-oriented, fully integrated, and systemic.

2.2.6 Sustainable Business Models

Improving sustainability often means that a change, adjustment or innovation of a product, service or process is necessary (Evans et al., 2017). Hence, a crucial skill to have for organizations in relation to sustainability is the ability to innovate. Business model innovation is an emerging tool for businesses desiring to have a sustainable business model (SBM) that has sustainability integrated into their strategy.

There is not a unified definition of a business model, however a commonly accepted explanation is that business models refer to the process of how a firm does business and

25

describes how value is created, captured, and delivered (Evans et al., 2017). The redesign of a business model can equip a business with the right capabilities to better meet the demands of a changing business environment (Teece, 2010). In the pursuit of more sustainable ways of doing business, new, creative, and positive innovation plays a crucial part (Evans et al., 2017). Sustainability innovations are associated with challenging the traditional thinking in how technology, processes, procedures and practices, business models, and systems are meant to be structured.

Business models are strongly interrelated to the concept of creating value. The prevailing concept of value in the business community is Adam Smith’s view of “exchange value” (Evans et al., 2017). Where the relative price of a good is expressed in terms of other goods (IESS, 2020). However, recently newer terms have been introduced such as “value-in-use”, as an increasing number of manufacturers adopt more service-oriented business models with a stronger focus on customers (Vargo et al., 2008). An additional term is “shared value”, introduced by Porter and Kramer in 2011, which suggests that economic value should also create value for society (Wieland, 2017). Additionally, environmental value is created when environmental problems are solved while creating economic value (Evans et al., 2017). Hence, through the lens of sustainability, economic value should create both social and environmental value.

Key aspects of SBMs are to align the interests of all stakeholder groups, as they are directly linked to the success of the business itself. Rather than prioritizing shareholders’ expectations - economic, environmental, and social aspects are included when looking at the needs of all stakeholders (Stubbs & Cocklin, 2008).

Value Networks

The term network is defined as “a group of three or more organizations, either self-initiated or contracted, connected in ways that facilitate the achievement not only of their own goals but also of a common goal” (Evans et al., 2017, p. 601). It is also commonly referred to as partnerships or coalitions. Value networks are “seen as a set of roles and interactions in which organizations engage both in tangible and intangible value exchanges to achieve economic or social good” (Evans et al., 2017, p. 601). Common goals are set and reaching the goals create value for all organizations involved in the network and external stakeholders. It can be used as a tool to accomplish objectives that might otherwise be difficult to solve as a single

26

organization. Sustainability in value networks means that economic, social, and environmental value is created and delivered to all stakeholders and members of the network.

Product-Service System

Product-Service Systems is a service-based business concepts that intends to replace products with services (Evans et al., 2017). New business models now look at combining tangible products with intangible services to fulfil customer needs. Conventionally, businesses have no responsibility of the product after it has been sold. However, with the use of a service, such as the ability to rent items, businesses have a responsibility during the use phase and the end-of-life phase. This end-of-life cycle thinking makes businesses accountable for social, economic, and environmental issues over a larger timespan.

Circular business model

A circular business model (CBM) is defined as “a business model in which the conceptual logic for value creation is based on utilizing economic value retained in products after use in the production of new offerings” (Linder & Williander, 2015, p. 183). It entails the process of reusing, remanufacturing, recycling, and repairing products and materials. It is a sustainable business model in the sense that it creates social, economic, and environmental benefits for all parties when adopted. This is an opportunity to cut costs, reduce environmental footprint, and offer the chance for consumers in all levels of society to increase the lifespan of purchased products.

2.3 Leadership & Sustainable Leadership

Current organizational leadership perspectives have been widely discussed among practitioners and are an extensively researched topic in business fields. The applicability of leadership theory in organizational settings has continued to be researched by scholars and practitioners. Today many leadership theories exist in how leaders run organizations effectively (Jackson, 2016). Scholarly research on leadership has witnessed a dramatic increase over the last decade, resulting in the development of diverse leadership theories that have revolutionized the way we understand leadership phenomena. (Dinh et al., 2014).

The leadership process entails many complexities, and researchers vary in their theoretical approaches to explain the phenomena. No universal definition of the concept of leadership exists, as it would undermine the complexity and hinder new ideas and creative thinking

27

(Harrison, 2018). Some researchers define and argue that the ability to lead stems from the leader’s certain traits or behavior, while others view leadership as a process of influence (Harrison, 2018; Jackson, 2016). Regardless, the interest in how leadership applies in different organizational settings has never been greater. Corporations seek to attract those with the right leadership skills since they believe they are special assets for their operations and improve the bottom line (Northouse, 2018). Managing an organization requires leaders who develop and display a diverse set of skills necessary to solve complex problems while meeting the demands of all stakeholders in an often changing and competitive environment (Jackson, 2016).

2.3.1 Transformational Leadership

According to Northouse (2018), transformational leadership has become a popular leadership theory for researchers in management, social psychology, nursing, education, and industrial engineering. It is a leadership practice that transforms and changes people. Values, emotions, ethics, standards, and long-term goals aspects that are associated with this style of leading. A transformational leader is a leader who treats followers as full human beings by being attentive to their needs and motives, instead of being treated as the means to an end. Through exercising a strong influence on followers, these leaders can motivate followers to accomplish what is greater than expected, helping them reach their fullest potential.

It is a process in which a leader and follower builds a connection that raises the degree of morality and motivation in both (Northouse, 2018). Transformational leaders act as role models for their followers, showing great motivation and being driven by personal values while stimulating followers to be creative and innovative. Building trust and recognizing accomplishments are also important factors. Additionally, individual consideration to followers’ personal goals, efforts, and development is taken through mentorship or coaching. Transformational leaders align the interests of the follower, the leader, the group, and the organization to facilitate growth for all parties (Bass & Riggio, 2006). A direct link between transformational leadership and organizational innovation has been found, as transformational leaders create a culture in which employees are empowered and encouraged to discuss and try new ideas (Jung et al., 2003).

According to Northouse (2018), a central behavior for these leaders is to create a shared vision of the organization and make employees motivated to work towards that vision. Transformational leaders create a vision based on the collective interests of both leaders and

28

followers, it provides a view of where the organization is, and where it is headed. This provides meaning and creates an identity of the organization. In turn, followers can find themselves more in line with an organization and its purpose, which also gives a sense of self-efficacy (Northouse, 2018).

2.3.2 Transactional Leadership

Transactional leadership refers to the exchange process that happens between leaders and their followers (Northouse, 2018). These leaders give their followers what they want, in exchange for what the leaders want (Kuhnert & Lewis, 1987). Indeed, transactional leaders offer financial rewards for good work and deny rewards for insufficient work (Bass & Riggio, 2006). While transformational leadership focuses on building strong relationships between the leader and the follower to improve productivity, transactional leadership focuses on the relationship between productivity and rewards (Northouse, 2018). As it is in the best interest of followers to satisfy the leader’s demands, transactional leaders are influential (Kuhnert & Lewis, 1987).

According to Kuhnert and Lewis (1987), transactional leadership is on a spectrum, ranging from lower-levels of transactional leadership to higher-levels of transactional leadership and lastly transformational leadership. On the lower level, transactions of value are the most important, but as leaders move upwards the spectrum, transactions of trust, respect, and support becomes more important along with rewards. Building relationships becomes a tool to motivate followers and have them perform well. The main difference between upper-level transactional leadership and transformational leadership is that transformational leaders have strong internal values which guides them in every decision and are translated to followers. These leaders transform the values of followers to that of the leader, creating united beliefs and goals throughout the organization (Kuhnert & Lewis, 1987).

2.3.3 Sustainable Leadership

Sustainable leadership (SL), or leadership for sustainability, is a relatively new concept within leadership theory, which has gained increasing attention, especially in the aftermath of economic crisis and corporate scandals. In their article, Gerard et al. (2017) attempts to conceptualize SL by reviewing current literature and theoretical frameworks. While no absolute definition of the concept exists, researchers seem to have some mutual views of what SL entails. One explanation is “leadership that requires long-term perspective in decision

29

making, fostering systematic innovation to increase customer value, developing a skilled, loyal, and highly engaged workforce, and offering quality products, services, and solutions” (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011a). While similarities exist, there are also apparent differences between the conceptual frameworks. Similarities include to take a long-term perspective overall and developing the workforce in a sustainable way.

SL differs from traditional leadership concepts as it does not advocate a certain style, list of behaviors, or unique traits of leaders (Avery and Bergsteiner, 2011a). It has opened the possibility of diverse development in the concept. Sustainability is a broad word with many meanings depending on the context. Therefore, it is no surprise that the idea of SL can be interpreted in many ways.

In their study, Casserley and Critchley (2010) interprets sustainable leadership as a people process, where they present a framework for creating sustainable organizations. They focus on practices that will create an effective leadership development, generate sustainable leaders, and likely create sustainable organizations.

Sustainability has become a widely used term with multiple meanings depending on the context. As the researchers mentioned above refer to sustainability as an internal process of developing employees in an organization in a sustainable way to reduce burnouts and employee turnover, other researchers give more attention to the external aspects of sustainability, such as society and the environment.

Avery and Bergsteiner (2011a) emphasize the importance of sustainable leaders to include all stakeholders, society, and culture in planning short- and long-term objectives. They argue that an organization should see its success as dependent on its relationship with society and the communities in which it operates. Therefore, it should be vital to establish long-term cooperative relations with all stakeholders and affected parties. The considered stakeholders should be all the organization’s employees, customers, investors, suppliers, the city, the state, the nation they are in, and the future generations of stakeholders. In this system, the pressure from stakeholders would lead organizations to behave ethically, environmentally, and socially responsible. This reliance on stakeholders helps the firm become sustainable and resilient (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011a).

30

The view mentioned above of leading business is not brand new. Previously, it has been referred to as “honeybee” or “Rhineland” leadership. This leadership style offers an alternative approach to run business, differing heavily from the traditional shareholder-first (also known as “locust”) approach. The terms honeybee- and locust organizations refer to two metaphors that have been described since biblical times. Honeybees represent the creation of something, as they build communities and ecosystems. In contrast, locusts represent destruction, as they swarm together and eat fields bare (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011b).

In contrast to profit maximization, SL offers organizations to deliver better and more sustainable returns, reduce undesired employee turnover, and accelerate innovation.

However, some disregard SL by arguing that it sounds too good to be true and is yet another form of humanistic management that works in theory but not so much in practice. Indeed, it is humanistic in how the leadership values people and considers the organization to be a contributor to social well-being. However, it is hard for any executive to argue against some of the goals this approach is sought to reach.

The goals include taking a long-term perspective in decision making, fostering systemic innovation aimed at increasing customer value, developing a skilled, loyal, and highly engaged workforce while offering quality products, goods, or services. Indeed, they are legitimate goals for the management of any organization that wants to thrive and last in the market (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011a).

The principles of sustainable leadership differ greatly from its counterpart, the shareholder-first leadership (SFL). In their paper, Avery and Bergsteiner (2011a) illustrate how 23 leadership elements are practiced differently in SL and SFL. By looking at the illustration on the next page it is easy to identify where the “mindset” of SL differs from SFL.

31

Figure 2. 2 – Leadership elements SL and SFL.

Source: Avery & Bergsteiner (2011a)

Avery and Bergsteiner (2011a) then also provides a framework for the 23 sustainable leadership practices in a sustainable organization.

Figure 2. 3 – 23 sustainable leadership practices

32

The pyramid of 23 sustainable leadership practices works as a guide for explaining management in adopting these practices. Management practices are grouped in three ways, (1) foundation practices, (2) higher-level practices, and (3) key performance drivers. The last group corresponds to the management practices with performance outcomes associated with the achievement of sustainability.

The pyramid is created to be dynamic in all directions, which means that not all first-level elements must be practiced ascending to the second level. In this way, it stays flexible. Managers can implement go from making changes in higher-level practices, key performance drivers to foundation practices at any time.

1. Foundation practices

These 14 practices can be introduced by management at any given time and include programs such as staff retention, training, and development, succession planning, promoting environmental and social responsibility, and ensuring a shared vision for the organization (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011a).

2. Higher-level practices

The higher-level practices consist of six practices: consensual decision making, creating self-managing employees, and realizing the power of teams. These practices can only emerge when the appropriate foundation practices exist. For example, employees will not be self-managing unless they have received the right training to self-manage (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011a).

3. Key performance drivers

Innovation, staff engagement, and quality create the third level of the pyramid. They are all related to the end-customer experience and, thus, drive performance. By combining foundation practices with higher-level practices an organization creates the key performance drivers. For example, highly having team-oriented, skilled, and empowered employees in a supportive knowledge-sharing and trust-building culture improves the quality of work (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011a).

4. Performance outcomes

The top of the pyramid concerns the five performance outcomes that create sustainable leadership. Practicing the 23 principles of the pyramid will lead to outcomes such as integrity

33

of brand and reputation, enhanced customer satisfaction, stable operational finances, long-term shareholder value, and long-term value for stakeholders (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011a).

Both internal and external factors have an influencing factor in an organization’s sustainable culture and leadership.

Externalities include the system in which organizations act in. Organizations are complex adaptive systems operating within further complex systems (Benn & Metcalf, 2013; Thompson & Caveleri, 2010). According to Benn and Metcalf (2013), organizations are only a piece in the complex and more extensive interconnected social, environmental, and economical systems in which it interacts. To achieve sustainability, leaders must recognize that their organization is a part of such systems. Leaders have the role of interpreting what strategies to implement in this adaptive environment to succeed. However, understanding such complexity requires leaders of extraordinary capabilities.

One of the most recent trends is interpreting sustainability implementation in the context of organizational change (Bateh et al., 2014). Put differently, sustainability initiatives are recognized as complex and challenging as any other organizational change initiatives that are prompted by a change in external factors. Implementing a sustainability program also has organizational culture implications that produce accompanying resistance to change. Thus, organizations that consider meeting their sustainability potential must be prepared to overcome significant barriers such as employee resistance and eccentricities associated with organization-wide culture change. Thus, to mitigate the tensions and facilitate effective performance, managers must exhibit appropriate leadership behaviors (Carter et al., 2013).

Another area of change is the business paradigm. Break-through developments in technology have caused industries, products, and markets to change, leading to a shift in management paradigms. According to Clarke and Clegg (2000), in these changing environments, the learning capacity is a critical attribute for managers as it enables managers to quickly adapt to the unknown while anticipating changes in the business environment. A change in the management of organizations is seen as natural. As paradigms shift, new opportunities arise for managers to catch and capitalize. The focus on sustainability is one paradigm shift that has occurred; it is, therefore, important for managers to understand this change and manage it effectively for the organization to survive (Clarke & Clegg, 2000).

34

Nevertheless, research indications are showing that leadership is a vital part of achieving sustainable organizations (Benn & Metcalf, 2013; Gerard et al., 2017). Sustainable leadership can allow a quick and resilient response that is competitive and appealing to all stakeholders (Gerard et al., 2017). It relates to a certain style of leading, emphasizing the importance of creating corporate cultures of ethics, sustainability, and long-term thinking (Avery & Bergsteiner, 2011a). Indeed, the concept advocates that organizations should shift emphasis from a traditional singular focus on finances to a view that organizations are contributors to broader environmental and social influences (Gerard et al., 2017).

35

2.4 Linking of theory model

The following model is designed to represent the connection between the areas presented in this chapter. It gives the reader a visual representation of how the topics discussed in this chapter are related to the research purpose and research questions of this study. The model is used as a basis to create the interview guide found in Chapter 3 and acts as a foundation on which the analysis in Chapter 5 is done.

In the section underneath the model, a written explanation is given to allow the reader to better understand its purpose and how it works.

Figure 2. 4 – The Linking of Sustainable Leadership Model

Source: Lilja, 2020

The model consists of one central ring which is sustainable leadership, the central topic being studied. In this study, sustainable leadership is studied in three ways, which are connected to the Research Questions formulated in Chapter 1.

36

RQ 1 explains business transformation, RQ 2 explains leadership challenges, and RQ 3 explains the leader/manager work.

Surrounding the central concept are 5 rings which represent concepts that are used to describe and build an understanding of sustainable leadership.

The outer rings are concepts and theories which have been explained in this chapter. The profit issue is a problem businesses face, which affects how leaders can change their business models and how they can promote innovation to become sustainable. The ring of leadership style refers to if transformational and transactional leadership has similarities to how sustainable leaders act. Skills, values, behavior, and strategies regards the characteristics of sustainable leaders and is meant to build an understanding of how sustainable leadership is shown in the leader. Clothing industry and fashion brands is the context in which these leaders operate, and an understanding of the context is meant to build an understanding of the leadership in the studied organizations. Sustainability, TBL, CSR, and the SDGs are the rules and guidelines for any sustainable organization, understanding them becomes an important aspect in understanding sustainable leadership.

37

3. Methodology

In this chapter, the reader is guided through the research methodology and research methods chosen for this study. Furthermore, the sampling strategy is explained, as well as a discussion concerning the trustworthiness and ethical considerations of this study.

3.1 Research Philosophy

To clarify the nature of reality and to build an understanding of the purpose of the study, researchers must ask themselves an abstract but critical question; what is reality? (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). It is a question that perhaps few ever ask themselves and something that is taken for granted and not reflected upon. However, it is a vital building block in research, as it acts as the foundation on which assumptions are made (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

To determine what research design to use and to be able to defend and argue for the choices I make, I must understand how different approaches to reality and knowledge differ and what implications they have for the focus of this study. The nature of reality and existence is referred to as ‘ontology’ in the context of research philosophy. Since this research aims to explore the reality of organizations and people instead of objects, I looked at the research philosophies associated with social sciences, and not natural sciences. As natural sciences are concerned with the study of scientific nature, such as the laws of physics, I ruled it out as the science area of this study. In social sciences, the different ontologies deal with how truths and facts are perceived. Here, realism refers to that there is only one truth, independent of the observer, and that truths exist that can be revealed. Opposite to realism is nominalism, which is referred to the thinking that there are no truths and that facts are all human creations and thus dependent on people’s perception (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

The goal of this study is to explore how leaders behave in organizations and to understand the motivation and thinking behind the leadership. I have decided that to explore these non-numeric aspects, I must interview humans. As such, I have chosen to view reality in that of relativism, which means that humans have many “truths” and facts depend on the viewpoint of the observer. Relativists deal with issues by acknowledging the fact that an understanding of a situation depends on the perspective of the viewer (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). That perspective is formed by the cultural-historical context of that person, such as their background,