AND STILL WE TINKER:

A STUDY OF INCREMENTAL POLICY CHANGE THROUGH STATE COMPULSORY ATTENDANCE LAW

by

GREGORY B. ECKS

B.A., University of Colorado Colorado Springs, 1996 M.A.Ed., University of Phoenix, 2003

A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Colorado Colorado Springs

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

Department of Leadership, Research, and Foundations 2016

ii

ã Copyright By Gregory B. Ecks 2016 All Rights Reserved

iii

This dissertation for the Doctor of Philosophy degree by Gregory B. Ecks

has been approved for the

Department of Leadership, Research, and Foundations by

Aldo Ramirez, Chair

Andrea Bingham

Grant Clayton

Sylvia Mendez

Dallas Strawn

iv

And Still We Tinker: A Study of Incremental Policy Change through State Compulsory Attendance Law

Dissertation directed by Professor Aldo Ramirez

This dissertation employs Event History Analysis and the methodological approach of adoption and innovation research to explore the influence of state-level determinants and diffusion processes on incremental policy change to compulsory school attendance age laws. Using Cox proportional hazards estimates, this study focuses on internal political characteristics of states, including the political and ideological makeup of state legislatures, as well as the demographic and socioeconomic context, which influence the likelihood for event occurrence. Results indicate significant effects for political party control of the state legislature, legislative policy ideology, minimum wage, and annual state poverty rate. These results mirror aspects of policy adoption and

innovation studies and evidence the applicability of these methods for the historical analysis of smaller policy events. Implications for future policy studies and continued research considerations conclude the study.

v

I dedicate this to my mom and dad who always believe in me and to my brother who inspires me.

Most importantly, I dedicate this to my wife, Donna, and daughter, Evelyn, who love and encourage me. Our family is my greatest opus.

vi

I would like to thank Dr. Grant Clayton for his continued support and

encouragement in my personal and professional growth. Further thanks to Dr. Sylvia Martinez and Dr. Al Ramirez for their continued guidance throughout my doctoral studies and Dr. Andrea Bingham and Dr. Dallas Strawn for always asking the right question at the right time.

A special thanks to Eric, Dave, Eric, Pat, and Greg, classmates whose support was limitless, and whose unbroken friendship is the sincerest takeaway of this endeavor.

vii CHAPTER

I. INTRODUCTION...1

Statement of the Problem...4

Purpose of the Study...5

Research Framework...7

Overview of Methods...9

Limitations and Threats...10

Key Definitions...11

Organization of the Study...11

II. REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE...13

Bounded Rationality...13

School Reform and Compulsory School Attendance...16

State Determinants and the Diffusion of Policy Ideas...27

Summary of Related Literature...35

III. METHODS...38

Purpose and Research Questions...38

Methods...39

viii

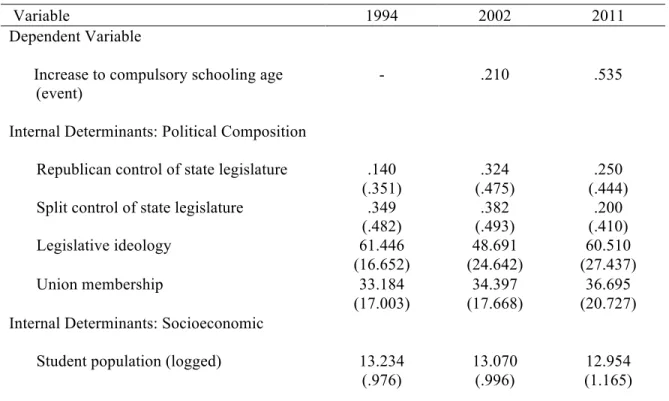

Descriptive Statistics...63

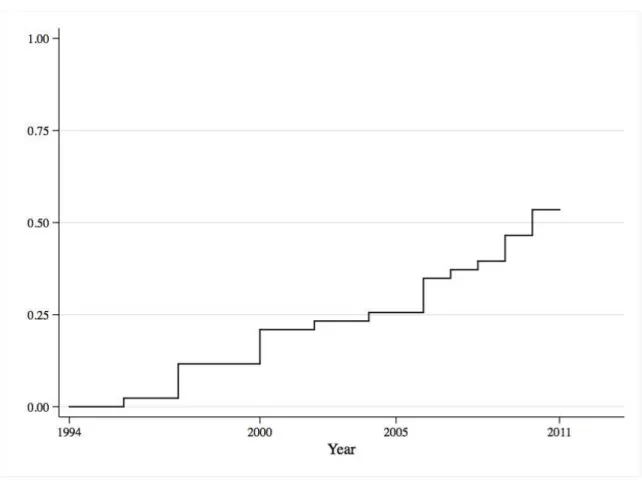

Pre-Estimation Statistics and Analysis...75

Model Results...79

Hypotheses...85

Summary...93

V. DISCUSSION...95

Review of the Study...95

Discussion...100

Contributions and Limitations...108

Conclusion...113

References...115

Appendix A. Coefficients and Confidence Intervals for Estimates of Incremental Change to Compulsory School Attendance Policy...130

ix Table

1. Increases to the Mandatory School Attendance Age, By State, 1994 – 2011...42

2. Summary of Variables...43

3. Summary of Research Hypotheses and Expected Coefficient Sign...52

4. Descriptive Statistics for Variables Influencing Incremental Policy Change...63

5. Cumulative Hazard Rates for Change to Compulsory School Attendance Policy...76

6. Cox Proportional Hazards Estimates for Change to Compulsory School Age...84

7. Summary of Research Hypotheses and Coefficient Sign...95

8. Research Hypotheses, Hypothesized Outcome, Estimate Sign, and Significance Level...97

x Figure

1. Theoretical Framework...37 2. Kaplan-Meier Cumulative Hazard Rates for Change to the Compulsory

Attendance Age...78 3. Cumulative Hazard Rate for Republican Control of State Legislature...86 4. Cumulative Hazard Rate for Political Legislative Ideology (Policy Mood) by

Quartile...88 5. Cumulative Hazard Rate for State Poverty Level, by Quintile...91 6. Cumulative Hazard Rate for Minimum Wage...92

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

Since their inception in the 17th century, compulsory education laws have confronted the economic and social issues facing America. In their formative years, compulsory schooling laws served to solidify a school's participation in establishing the moral fabric of a community at the behest of parents and families (Katz, 1976; Tyack, 1976). As they matured, these laws served a growing education system developing in times of dramatic economic and social change (Landes & Solmon, 1972; Moberly, 1980; Tyack, 1976). Compulsory education laws have also sparked debate about the

government’s role in the education of a democratic society. Promoters of compulsory schooling argue these laws demonstrate a commitment by our nation to prepare every young person for the economic and social realities of an ever-changing American society and globally competitive world (Belfanz, Bridgeland, Bruce, & Fox, 2013; Bridgeland, Dilulio, & Streeter, 2007; National Education Association [NEA], 2010). Opponents argue parents alone should make the decision regarding their child’s education and various forms of compulsory attendance at the state level are inconsistent with the tenets of America’s founding principles (Katz, 1976; Moberly, 1980; Nawaz & Tanveer, 1975). Compounding the debate is the influence of state and federal mandates on local decisions concerning education policy. Over the past few decades, a continued increase in federal and state government involvement has challenged policy makers across the political spectrum to find innovative ways to address the issues confronting America’s education system (McLendon & Cohen-Vogel, 2008). The result has been a continued “tinkering” of American public education through small incremental change to existing policy and a

series of external reform innovations challenging traditional approaches (Tyack & Cuban, 1995).

Nevertheless, throughout the history of public schooling in America, compulsory education and compulsory attendance laws have remained core components of state education policy because they demonstrate a state’s commitment to provide a free and universal public education (Nawaz & Tanveer, 1975). However, the changing political and socioeconomic factors of historical eras often induce changes to these laws. The result has been slow, incremental shifts in policy, which have increased both the total number of mandated years a child must attend school as well as the number of years states provide a free, compulsory education (Richardson, 1980; Tyack, 1976).

In the late 20th century, the publication of A Nation at Risk once again provided impetus for reforming America’s public schools. New reform initiatives began to blur the lines between local, state, and federal governments, causing greater centralization of education policy decisions concentrated at the federal level. The Improving America’s Schools Act of 1994 (IASA) a reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Schools Act of 1965 (ESEA, 1965), placed education reform under the watchful eye of the federal government through the lure of financial incentive. Major tenets of the Act provided federal dollars for school reform and innovation, along with an introduction to state-level standardized testing and larger school-system accountability. Subsequently, the passage of the No Child Left Behind Act in 2002 (NCLB), a major bipartisan reauthorization of ESEA, created new measures heavily influenced by federal policy decisions (Groen, 2012). As a result of this landmark legislation, states implemented policies aimed at greater accountability for school systems, including measuring teacher effectiveness,

monitoring the yearly progress of schools, and increasing overall school-system outcomes. Consequently, education in America, once a product of more localized control, inched farther toward an issue of national interest shaped by the principles of accountability and reform (Groen, 2012; Haertel & Herman, 2005; Hartney & Flavin, 2011; Jaiani & Whitford, 2011; McLendon & Cohen-Vogel, 2008; Nelson, McGhee, Meno, & Slater, 2007; Wong & Shen, 2002).

Within this context, from 1994 to 2011, 23 states increased the mandatory school attendance age, sometimes referred to as the “minimum school leaving age,” from 16 to 17 or 18. Although by no means a new policy innovation, this simple incremental policy shift attempted to address issues challenging American schools. These problems

included a sluggishly declining school dropout rate and an increased desire to prepare students for the complexities of a 21st-century economy (Belfanz et al., 2013; Bridgeland, Dilulio, & Morison, 2006; Mackey & Duncan, 2013; NEA, 2010). As a result, American public school students must now attend school to the age of 18 in 18 states, 17 in 9 states, and a remaining 23 states continue to mandate 16 as the upper school attendance age. Consequently, by 2011, more than half of the union determined 16 was no longer old enough for compulsory education.

During the 2012 State of the Union Address, President Barack Obama argued that “all students stay in high school until they graduate or turn 18” (Obama, 2012). Thus, compulsory school attendance, which for more than 150 years had existed primarily as a state policy initiative, was becoming a new agenda for the highest office in the nation. Supporters believed that “as we continue working to improve our educational system, we need to have students staying to complete their coursework” and that it was time for a

“consistent message and consistent policies” across the country ("Heffernan Bill," 2015). Yet, not surprisingly, the question remained: If compulsory attendance is an effective method for addressing high school completion and is an instrumental tool in promoting a universal education system, why did some states adopt changes to their mandatory school attendance law while others remained in relative policy stasis? This overarching question guides this research.

Statement of the Problem

Substantial empirical research exists exploring the factors influencing state-level innovation and adoption of new public policy ideas. Since the seminal work of Walker (1969), the characteristics of policy innovation have become foundational in

understanding the variations in the adoption and innovation of new public policy at the state level. Walker’s work challenged traditional policy processes, those framed by political party conflict and voter participation, by providing greater theoretical

foundations and empirical analysis of the internal state characteristics influencing policy outputs. Walker’s early use of these determinants of policy change, which encompass the political characteristics of legislative bodies and the socioeconomic conditions within states, and the effects of the regional diffusion and migration of policy ideas, broadened the approach to studying state behavior in the adoption and innovation of new policy ideas.

Over the last two decades, research has been expanding the theoretical lenses and methodologies used to study these approaches to the public policy process, allowing for more robust analysis of the factors influencing public policy outputs (Berry, 1994; Berry & Berry, 1990; Boehmke & Skinner, 2012; Glick & Friedland, 2014; Mallinson, 2015;

Nicholson-Crotty, Woods, & Bowman, 2014). Unfortunately, most existing policy adoption studies focus on the innovation of new policy issues, bypassing the multitude of small incremental changes to existing policy. These incremental shifts in policy are an important component in understanding the current education environment, providing the researcher greater insight into the legislative attempts at improving America’s schools.

An abundance of information also exists related to the individual returns and societal externalities associated with additional years of education attainment and compulsory schooling. However, little empirical research exists exploring the factors influencing recent policy decisions mandating changes to these additional years of schooling. A 2013 report from the Regional Educational Laboratory and the National Center for Educational Evaluation and Regional Assistance summarized the existing research on recent changes to compulsory school attendance laws and found no

conclusive evidence to support the effectiveness of policy change (Mackey & Duncan, 2013). However, there is scant discussion in the report related to the policy decisions of those states where policy changed and those who remained in stasis.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to investigate the causes of incremental policy change to the compulsory school attendance age utilizing policy adoption and innovation

methodologies. Specifically, the research explores the influences of a) the political composition of state governments and the ways in which political differences affect incremental policy change, b) the role of demographic and socioeconomic contexts on the policy change process, and c) how regional diffusion and the interstate migration of

policy ideas influence incremental policy change to the compulsory school attendance age.

The study adds to the growing body of research concerning state education policy processes in a number of ways. First, the study moves outside the current trend in

education reform studies, which primarily have focused on the adoption of new policies addressing the more punctuated topics of student assessment, school choice, teacher evaluation, and higher education by focusing on a small incremental shift in existing policy. Although this study does not address the adoption of new policy, it explores how changes to existing statutes have occurred within a broader policy context. Second, the study adds to the methodological literature of state policy processes by employing Event History Analysis (EHA) to study the nature of the determinants and diffusion processes causing policy events. As states continue to explore the idea of increasing the

compulsory schooling age, an analysis of characteristics influencing successful policy enactment may provide greater support for less innovative states considering similar change. Furthermore, by providing analysis of the policy determinants associated with incremental change, this research may also be beneficial, for example, with experimental studies identifying the costs and benefits of compulsory schooling policy change.

Finally, from a historical standpoint, a need exists to chronicle the events of significant periods. The changing role of federal and state governments concerning education policy also warrants closer analysis of systemic processes. The trend for greater accountability and the immense growth in the availability of education data provide an opportunity to study both across a wide spectrum of related topics, including initiatives aimed at school reform. As America enters the next era of education reform,

the need to add literature similar to the work of Katz (1976), Rury (2013), and Tyack (Tyack, 1976; Tyack & Cuban, 1995) is paramount to a larger understanding of historical education events and movements. Similarly, the work of Richardson (1980), which empirically explored the contextual and historical factors influencing policy variation across states during initial compulsory attendance age adoption, needs replication for a new era of America’s education history. This study mirrors Richardson’s existing research but adds EHA methodologies and current policy data to analyze policy events associated with recent compulsory education policy change.

Research Framework

This dissertation study borrows extensively from prior policy adoption literature, which has had as its foundation two encompassing conceptual approaches: the internal determinants of states and the regional diffusion and interaction of policy ideas. Prior studies using internal determinants methodology focused on the political, demographic, and socioeconomic characteristics of individual states as causal explanations for policy events. Research into regional diffusion and national interaction methodologies has explored the influence of contiguous state and regional interconnectedness as catalyst for policy change (Berry, 1994). The seminal work of Berry and Berry (1990) was the first to blend these two approaches, expanding the growing body of theoretical research on public policy processes by providing greater methodological scope and more advanced statistical modeling. Similar to Berry and Berry, this study employs Event History Analysis (EHA), a quantitative methodology which models the causal analysis of event timing and duration using longitudinal data (Allison, 2014; Box-Steffensmeier & Jones, 2004; Mills, 2011). However, unlike a large number of policy innovation studies

exploring new state-level policy creation, this research focuses on the adoption of a small incremental change in existing policy.

The theory of bounded rationality, which is a behavioral choice component of rational choice theory, frames the study. Popular in early policy and organizational choice literature, bounded rationality posits a process where rational decision-making is constrained by a lack of information, time, and the cognitive abilities of identified agents. From a public policy perspective, governments today face a myriad of societal issues bound by the limits and complexities of the political contexts in which they operate. The study of the interaction between the internal determinants and political diffusion of state-level policy adoption provides an approach for analysis of these contexts, helping to identify potential causality in the incremental tinkering of policy events. The existing literature and the following research question guide the study:

What characteristics influence the probability of state policy change increasing the mandatory school attendance age between 1994 and 2011?

This dissertation hypothesized several characteristics to have significant effects on policy change: a) the political interaction and diffusion between various state

governments which share policy ideas across state borders and within geographic regions, b) the changing pattern of education funding, school system demographics, and economic characteristics of states, and c) the influence of ideological political actors who maintain or resist traditional education policy mechanisms. Specifically, the study hypothesized the most significant effects would be evidenced in the relationship between strong state economic characteristics and policy change. These effects mirror prior policy research and illustrate the influence of state economic condition and fiscal decision-making on

policy outcomes. State governments with challenging economic conditions and stagnant wage rates would be more likely to pass legislation increasing the number of years students must attend public schools. Conversely, states with vibrant and healthy economic indicators would be less likely to increase compulsory attendance age. This dissertation study further hypothesized that the dominance of a liberal legislative ideology and single party control of state legislatures would have a significant effect on policy change. Finally, the study posits policy migration across states has little

significant effect on policy change; however, regional diffusion through state enactment of similar policy change would evidence small significant effects on the likelihood of event occurrence.

Overview of Methods

Similar to the extant literature on public policy innovation, this study utilizes Event History Analysis (EHA) to investigate the variables influencing the probability a state would increase compulsory schooling age policy (Berry & Berry, 1990; McLendon, Hearn, & Deaton, 2006). EHA is a quantitative methodology focusing on the timing of an event, the length of time to the occurrence of an event, and interpretations of factors causing events (Allison, 2014; Box-Steffensmeier & Jones, 2004; Mills, 2011).

Consequently, this research focuses on incremental changes to mandatory school

attendance laws as an event. Unlike standard regression models, which utilize only cross sectional data, the unique structure of longitudinal data in EHA methodologies permits the examination of influential explanatory variables on the occurrence or non-occurrence of events.

Limitations and Threats

Due to the complexities existing across state policy subsystems, capturing all of the characteristics and variables influencing the policy process presented issues with omitted variable bias. For this study, the influence of time variant characteristics illustrates how information signals policy actors and how limited signals affect incremental change. As a result, this study does not account for time invariant characteristics of states. Additionally, the growing interaction between states and the federal government as it pertains to education policy reform presents a need for greater macro analysis of diffusion processes. The addition of regional groupings of states in this study is predominantly subjective and may result in spurious estimates. The use of prior research and accepted regional groupings of states by reputable sources attempts to limit these threats.

This study utilized data from 1994 to 2012, data bracketed by the passage of the Improving America’s Schools Act (1994) and the State of the Union Address of 2012, the year in which the mandatory schooling age of 18 gained larger national attention.

Therefore, this study’s findings are only applicable to policy changes during this period and no larger generalizations about previous or future policy changes to compulsory school legislation is warranted. A larger study inclusive of more expansive datasets would provide a more complete picture of compulsory schooling in America.

Furthermore, during the period of the study, a number of states lowered the compulsory school attendance age, reflecting a need for further research into multiple types of policy events.

Key Definitions

Adoption: The enactment of a new policy (the use of adoption in this study mirrors Walker, 1969).

Compulsory education: A universal education program provided for all state citizens. Compulsory/mandatory school attendance: Laws and policies requiring mandatory school attendance across various age ranges.

Determinants: State-level characteristics influencing the adoption of public policy. Diffusion: The spread of policy ideas. In this study, diffusion represents the regional spread of policy ideas across multiple states and areas.

Event: The adoption of a policy change increasing the age for mandatory compulsory school attendance.

Incremental: To increase or add. For this study incremental describes changes to an existing state policy.

Innovation: The creation of new policy ideas or agendas.

Migration: The spread of policy ideas. In this study, migration mirrors the use of interstate to denote the spread of policy ideas across neighboring states.

Organization of the Study

The organization for the remainder of the study is as follows. Chapter 2 provides a review of the literature related to this study beginning with the theory of bounded rationality, which frames the research. The remainder of the chapter explores literature related to the larger conceptual framework and variable selection, including a brief history of school reform, a review of the empirical studies on additional years of schooling and compulsory attendance, and previous research on state policy adoption.

Chapter 3 opens with a description of Event History Analysis as the methodological approach to the study. A description of the variables, data sources, and the empirical approach to the analysis follows. Chapter 4 presents results from the empirical model, and Chapter 5 includes a general review of the study results, discussion, and

CHAPTER 2

REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE

The following review of relevant literature begins with an overview of bounded rationality, a component of rational choice theory as the lens framing the study and its applicability to public policy. The second section includes a selected history of education reform movements, compulsory schooling laws, and empirical research on individual and external returns to additional years of educational attainment. A third section reviews the extant literature on state policy adoption and innovation, focusing on the determinants and diffusion characteristics influencing public policy processes and outputs. The final section summarizes the research and provides a review of the conceptual framework for the study.

Bounded Rationality

Change in public policy is often sluggish, an incremental process constrained by the complexities of differing policy systems and bureaucratic composition. Policy actors face polarizing viewpoints and ideological preferences, the power of various external governing bodies who often provide incentive for action, and interest groups who

influence agenda attention. Research dedicated to the study of policy agenda setting and the public policy process center on the intricacies of these challenges. Researchers in this area have long sought to uncover how popular policy fades over time, how issues of little political importance gain traction and become key policy agenda, and how the political process of democratic societies balances the multitude of issues with meaningful solutions. This research has led to a number of theories across the political sciences.

These theories attempt to understand how public policy makers identify, navigate, and solve complex societal issues.

Stone (2012) has noted the rational decision-making process, which involves “choosing the best means to obtain any goal,” often frames the study of public policy processes (p. 249). Simply, when confronted with public issues and concerns, policy makers provide appropriate and rational choices to even the most complex of problems. Using a rational choice approach, public policy processes require policy actors to have a complete understanding of how action affects the public good, the costs and benefits of action, and the alternatives to action. Rooted in the utilitarianism of the mid-19th century, rational choice became the dominant theoretical lens for much of early public policy analysis and innovation, reflecting the process-outcomes thinking of the era (Stone, 2012). Unfortunately, the number of policy issues confronting politicians at any given time is both burgeoning and overwhelming, and choosing which policies warrant

immediate attention can be difficult when faced with limited information, time, and fiscal resources. The result is a policy process framework favoring small incremental change (Baumgartner & Jones, 2009).

In other work, economist and political scientist Simon (1972) posited a behavioral theory of choice, one which more accurately illustrated how rationality is constrained by the limits of time, information acquisition, and cognitive ability. Simon termed this decision-making process bounded rationality. According to Simon, individuals and organizations operate within the constraints of a bound rationality and often have “incomplete information about alternatives” (p. 163). Forester (1984) added: “Under conditions of bounded rationality, then, decision makers seemingly ‘do what they can.’

But, they may, however, simply ‘make-do’” (p. 24). Bounded rationality is applicable to the current public policy process, helping to define the context and constraints

influencing political decisions and agenda action. These contexts, and the political strategies associated with varying degrees of constraint, create a continuum of bounded rationality defined across agents, information, and time. In summary, agents facing unlimited information and time will act rationally, agents who have information of varying quality and limited time will search for solutions and produce satisfactory outcomes, and in situations where agents have varying ideological perspectives and information, competing agents will develop strategies to counteract and overcome opposition (Forester, 1984).

More recently, Jones (1999) built on Simon’s premise which found human decision-making is a product of external and internal environments, arguing most of politics “is adaptive and intendedly rational” (p. 298). External environments are how one responds to incentives and internal environments are those behavioral qualities that cause us to deviate from the external environment and rational decision. In political settings, these deviations occur as the result of attention, emotion, and over-cooperation. As a result, bounded rationality provides a unifying framework for public policy studies through the linkage of human choice behaviors and organizational outcomes (Jones, 2002; Jones, 2003). Consequently, bounded rationality has become fundamental to theories of policymaking, including the work of Baumgartner and Jones (2009) whose theory of punctuated equilibrium policy processes presents bounded rationality as the most common state for political systems. According to True, Baumgartner, and Jones (2006), politicians face an insurmountable number of public policy issues, and choosing

which of these problems to address, and the potential solutions to these problems, results in small incremental change as policy subsystems navigate the “changing circumstances” of the day (p. 7).

School Reform and Compulsory School Attendance School Reform

Throughout history, American education and its respective reforms have been a reflection of the changing circumstances of the period. These changes altered the societal conditions of the time, and efforts toward reforming schools to meet these changes

occurred within an expanding public policy landscape. Either through slow incremental change, or through outside initiatives aimed at fundamental transformation, these reforms have sought to develop America’s public school system under the auspices of progress. Unfortunately, progress has been stymied by the realities of reform initiatives, even as America’s schools continued to serve a foundational role in the building of a nation (Tyack & Cuban, 1995).

Early school reform movements, specifically those initiated by Horace Mann and the “common school” reformists of the mid-19th century, as well as the education

progressives of the early 20th century, are examples. Mann, whose efforts brought about a shift from the fractured, localized education systems established during America’s colonial period, established the framework for a universally designed “common school” to address the changing demographics of a new nation. Influenced heavily by the

national education systems of Europe and the political assimilation of the time, Mann and the common school reformists presented schools as a form to induce American social progress. Thus, as Tyack and Cuban (1995) noted, Mann “took his audience to the edge

of the precipice to see the social hell that lay before them if they did not achieve salvation through the common school” ( p. 1).

Similarly, driven by the dramatically changing industrial economy of the late 19th and early 20th century, the education progressives sought to create a more efficient American school institution. Influenced by the work of Frederick Taylor and the economic thinking of a vigorous industrial era, progressive policy makers promoted greater school efficiency through standardized schooling processes, greater institutional conformity, centralization, and the dramatic expansion of the bureaucratic apparatus (Callahan, 1962a; Rury, 2013; Tyack & Cuban, 1995). Thus, all across America schools were becoming identical institutions. Although by the middle of the 20th century there was a shift away from “Taylorism” and the efficiency movement, a number of reforms instituted during these fundamental times have remained part of America’s public school system today.

The growing disillusionment of the political and socioeconomic systems in the second half of the 20th century provided further impetus for school reforms, mirroring the changing societal conditions of postwar America. At the forefront of change were the sweeping civil rights and antipoverty initiatives passed at the federal level under the Johnson administration. These changes to the political and economic fabric of society had dramatic effect on America’s schools. For example, the landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which began the desegregation of America’s public schools in the 1950s, ushered in a new era of increased federal involvement in education policymaking and school reform. The subsequent passage of the Elementary and

to schools for students historically passed over by previous reforms. Importantly, sections of the ESEA further provided federal financial assistance to school systems educating students living in poverty, minority and immigrant student populations, and students with developmental disabilities. Thus, the enactment of ESEA opened the doors for more students by expanding the inclusiveness of schools and projected Washington, DC, as an important actor in the education policy network (Rury, 2013; Tyack & Cuban, 1995).

Dramatic shifts in the American landscape during the 1970s and 80s paved the way for new reform initiatives aimed at progressing “schools as a tool for economic development, and for individual advancement” (Rury, 2013, p. 213). The publication of A Nation at Risk (1983) challenged the systemic nature of public education and

questioned its overall relevance for the modern era. Conservative Americans called out for new reforms to alter school systems, reforms more appropriate for the challenges of a new world and global economy. Budding from these concerns, the Clinton

administration passed landmark reforms for the nation’s schools in the Improving America’s Schools Act (1994). This new federal policy provided a series of incentives for state education innovation and school reform and directed states to develop a system of increased standardization and accountability (Groen, 2012; Haertel & Herman, 2005; Jaiani & Whitford, 2011; Nelson et al., 2007). The subsequent passage by the Bush administration of No Child Left Behind (NCLB, 2002) further opened the door for accountability-based reforms for America’s public K-12 education system and placed added emphasis on a more consolidated monitoring of yearly student progress and growth. These new reforms further increased the centralization of America’s schools

under a larger macro political system, giving greater policy oversight to governments at both the state and federal level. Wong and Shen (2002) have identified the elements of these new reform initiatives:

States have now developed accountability frameworks for student achievement, emphasizing standardized tests and grade level benchmarks. In addition, a growing number of states are passing legislation that allows for more

controversial measures, such as public school vouchers, charter schools, and provisions for state takeover of under- performing schools and districts. Some states have made non-traditional alternatives, such as home schooling, more accessible to families. Alternative leadership (e.g., business leaders) has also been recruited into the public sector to help failing schools. (p. 161)

By the turn of the 21st century, education in America was expanding at a rapid pace. Education in America was no longer a local issue supporting the moral fabric of a community through the common school. Decades of reform influenced by the changing circumstances of societal progress introduced into education new policy systems and influential policy actors. These increasing levels of bureaucracy, influenced by a wide variety of external and internal determinants, have limited local influence and decisions on education policy.

Compulsory Schooling Laws

Similar to the arguments presented by proponents of policy change today, the first codification mandating public schooling sought to fulfill the obligation of creating

productive citizens who could contribute to society. Thus, the same forces challenging school reformers influenced compulsory attendance laws. The very first of these

initiatives in the United States was enacted in 1642 in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and reflected the social and religious norms of a small colonial community (for a brief history of early compulsory schooling refer to Zhang, 2004). However, during this early colonial period, the concept of compulsory schooling remained misleading, as many viewed education as something still obtained through societies other cultural institutions, church and family (Katz, 1976). While education remained largely a task conducted in the home, these early laws made it clear the state had “the right to lay down minimal standards for the education of children” (p.13).

The founding of a new nation and the growth of the industrial economy changed how society viewed the role of education. The development of the common school provided an opportunity for the proponents of compulsory schooling to address the changing norms of society. Education during the 19th century was making an incremental shift away from a fractured state to a uniform institution. Public education proponents saw a need to Americanize the new nation, which was growing more diverse because of new immigrant populations and burgeoning urban centers. A desire to protect children from the harsh realities of industrial production provided further justification for school compulsion (Katz, 1976; Landes & Solmon, 1972). Additionally, early efforts to mandate schooling were greatly affected by the influence of child labor laws which had effectively limited “the employment opportunities of school age children” (Landes & Solmon, 1972, p. 58).

In 1852, during the era of Mann and the common school reform movement, Massachusetts became the first state to pass a compulsory school attendance law mandating parents have their children attend school according to age. Other states

followed, and by 1890, most states had adopted similar compulsory attendance laws, signaling to the inhabitants of each state the importance of education as a public policy issue. Much like today, these laws varied by region and across states. Laws existed in all of the New England states but remained sporadic in the South, and the age requirements varied from a minimum age of seven to a maximum mandated attendance age of 16. The enforcement of these laws was just as sporadic, as no formal bureaucratic mechanism existed to implement a law’s provisions. As noted by Tyack (1976) and Landes and Solmon (1972), most of the late 19th century increases in school participation and education attainment existed prior to the era of state school attendance compulsion. Consequently, as the turn of the century approached, compulsory schooling policy had become largely a symbolic effort by states which were left with “dead letter” and “dead hand”—unenforceable policy meaning little on paper (Katz, 1976; Tyack, 1976).

As historical eras changed throughout the 20th century, so too did the focus of secondary education policy. During the first half of the 1900s, the rapid pace of American industrialization heavily influenced the milieu of the education system. The era of efficiency and “Taylorism” in school administration gave rise to a growing education bureaucracy which scrutinized the effectiveness of all aspects of the school system (Callahan, 1962). Under the larger umbrella of efficiency, school systems developed enforcement mechanisms making compulsory schooling more than “dead letter.” Depression era politics and a dire economic climate influenced another, even greater, incremental change as states began instituting policy increasing the age of school compulsion. By the end of the 1930s, 31 of the 48 states had reformed state compulsory

education laws, pushing the mandatory leaving age from 14 to 16 years old (Katz, 1976; Landes & Solmon, 1972; Tyack, 1976).

The development of the American high school at the dawn of the 20th century presented new challenges for education policy. Dramatic shifts in high school enrollment defined the first half of the era. In 1910, less than 20% of high school age youth were enrolled in school, a number which would increase to over 70% by 1940 (Goldin & Katz, 2003). During this time two different ideologies, framed by the Committee of Ten and the authors of the Cardinal Principles of Education, defined the trends in high school education policy (Tyack & Cuban, 1995). Similar to the development of the common school in the last half of the 19th century, the creation of America’s high schools followed the rapidly changing social and economic contexts of the time. For the Committee of Ten, high schools needed to be standardized institutions providing the necessary preparation for higher education; for the authors of the Cardinal Principles the task of high school was to prepare students for “social efficiency” (Tyack & Cuban, 1995). Regardless of the aim, Americans students were flocking to school, attending for more days, months, and years than ever before. As interest in the American high school grew, compulsory schooling policies remained as varied as they had been at the turn of the century, accounting for only a small percentage of school enrollment (Goldin & Katz, 2003).

The post-World War II era brought a long period of stasis in compulsory school policy, as age 16 remained the standard school-leaving age across the country. Once again, however, the challenges of social and economic forces of the age framed policy agenda. The first was America’s stance as a world superpower and the politics of the

Cold War. The push to challenge the Soviet Union placed emphasis on the importance of mathematics and science, stimulating the need for standardization and efficiency. The second was America’s challenging social conditions of the 50s and 60s, which dominated school reform initiatives and policy, placing a greater emphasis on schooling equity (Tyack & Cuban, 1995).

Renewed interest in compulsory schooling would return during the difficult economic and social climate of the 1970s. Anecdotal evidence about truancy rates in urban school systems and a lack of enforcement of existing attendance laws had opponents of compulsory schooling arguing once again that school compulsion had become “dead letter” and “dead hand.” Frank Brown, Chairman of the National

Commission on the Reform of Secondary Education claimed, “High school students are entitled to an education, but should not be forced to acquire one, and it is now clear that time is running out on compulsory education” (Moberly, 1980, p. 198). Legal challenges to compulsory schooling laws supported this notion. For example, in Wisconsin v. Yoder, the courts, citing constitutional considerations, established eighth grade as an education standard in a case pitting members of an Amish community against state compulsion enforcement. Similarly, supported by the ruling in Wisconsin v. Yoder, a Florida judge found a father could keep his five sons home from school without state or

school-imposed consequence (Nawaz & Tanveer, 1975). Although time had not completely run out on compulsory schooling, there remained little interest over the next few decades in policy change past the age of 16.

However, over the last two decades, a number of states have implemented incremental change in their school attendance age in an era framed by increased federal

and state accountability reforms. Many of these changes have addressed sluggishly declining school dropout rates and serve as a societal message that schools are preparing students for college and work force readiness. Proponents of compulsory attendance laws, including the National Education Association (NEA) and special interest groups like Civic Enterprises, often declare the benefits of such policies and the effects they have on addressing school dropout and graduation rates and student disengagement from school. These proponents also see such policies as a mechanism for ensuring positive future individual and societal benefit (Belfanz et al., 2013; Bridgeland et al., 2007; NEA, 2010). Empirical research within the field of economics supports these claims,

consistently finding significant individual effects from additional years of schooling and educational attainment (Acemoglu & Angrist, 2009; Angrist & Krueger, 1991; Messacar & Oreopoulos, 2013; Oreopoulos, 2006, 2007, 2009). These studies, advanced from the extensive literature on human capital (Becker, 1962; Schultz, 1961), explore the

individual returns and externalities associated with additional years of schooling across various periods. This research often includes compulsory schooling laws solely an instrumental measure for additional years of schooling, and scant empirical evidence exists on the fidelity of these policy reforms or the processes supporting implementation. Compulsory Schooling Research

As previously mentioned, studies exploring late 19th- and 20th- century education outcomes have identified strong evidence supporting the effect of increased years of schooling on wages and overall levels of education attainment. The first of these studies is the seminal work of Angrist and Krueger (1991), who identified the significance of mandatory schooling laws and their effect on education attainment and future individual

wage earnings. The authors’ findings indicated compulsory schooling laws had an effect on the number of students who remained in school for an additional year, keeping 25% of potential school dropouts in school, and increasing long-term wages. The findings of this study and others have explored additional years of schooling and private returns, and little additional evidence has suggested additional years of schooling have positive aggregate external returns or larger societal effect (Acemoglu & Angrist, 2009; Clay, Lingwall, & Stephens, 2012; Kara, 2010; Margo & Finegan, 1996; Park, 2011).

Consequently, researchers have found compulsory schooling to have additional long-term individual returns, including increases in income, doubled wages across an individual’s lifetime, decreases in unemployment and the probability of not working, and an overall increase in personal health and lifelong happiness (Oreopoulos, 2003, 2006, 2007, 2009). Supporters of policy change have cited these benefits as evidence concerning the

significance of increased years of schooling and the subsequent need for school attendance compulsion (see Belfanz et al., 2013; Bridgeland et al., 2006).

While some studies found no significant effects to larger aggregate wages and incomes from compulsory schooling laws, some evidence exists indicating these laws produce additional public externalities. This evidence has suggested compulsory schooling laws have significant effects on reducing crime rates for adults and adolescents, and the social savings of crime reduction is a significantly positive externality of attendance compulsion (Chan, 2012; Lochner & Moretti, 2001).

Conversely, opponents of increases to the compulsory schooling age often argue students forced to stay in school longer have negative effects on the school environment and school outcomes. A recent study from Anderson, Hansen, and Walker (2013) found

increases in the compulsory schooling age had negative reinforcement effects on schools. Their findings indicated that in states where the attendance age was increased and

students remained in school because of compulsion, female students and younger students experienced greater school absenteeism, feelings of inadequate school safety, and potential victimization. Still, others have found compulsory attendance also affects teachers through greater absenteeism and lost instructional time (Green & Navarro Paniagua, 2012; Wilson, Malcolm, Edward, & Davidson, 2008). Unfortunately, the nature of these effects becomes more serious when purposeful incapacitation—where communities attempt to deter crime by keeping students in school longer—displaces crime from communities into schools (Gilpin & Pennig, 2013).

Yet research into the effectiveness of recent state-level policy change concerning compulsory attendance is insufficient, and little effort has been made over the last decade to add to this dearth of information (Mackey & Duncan, 2013). However, the state of New York, addressing concerns regarding school dropout rates, commissioned a report in 2002 to explore the effectiveness of compulsory attendance policy laws in Texas and Kansas, two states that had recently passed incremental change in policy. The report recommended New York not increase the compulsory schooling age, citing results indicating slight decreases in school dropout, sizeable increases in truancy from school, and no change to school completion rates across both states (Burkhauser & Thomas, 2002). Similarly, Landis and Reschly (2011) explored data from five successive school years to determine the grade at which dropouts leave school and the ways in which increases to compulsory schooling ages might affect aggregate school dropout rates. The authors found compulsory school attendance age significant in affecting the timing of

dropout; however, the policy increases had no effect on the overall dropout rate. Despite this continued gap in the literature on the effectiveness of policy change, increasing the mandatory schooling age continues to fill the pages of interest group reports and policy briefs touting the benefits as a means to ending the dropout “epidemic” and “crisis” (see Belfanz et al., 2013; Bridgeland et al., 2007; Bridgeland et al., 2006).

State Determinants and the Diffusion of Policy Ideas

American education governance represents a complex relationship among local, state, and federal governments, a shifting continuum of localized autonomy, state and regional interaction, and an increasing federal centralization, which heavily influences state policy processes. Marsh and Wohlstetter (2013) have described the structures of this relationship: “The intergovernmental landscape for education, therefore, spans a multi-tiered set of interactions: federal–state–local, federal–state, state–local, and federal–local” (p. 2). These multiple landscapes of interaction have created a “tangled web of education governance . . . cluttered with organized interests, public-sector bureaucracies, and fragmented political authorities” (Hartney & Flavin, 2011, p. 252). These interests influence the probability of policy adoption and change through the political composition and ideology of state legislative houses, the role of organized special interests on the policy-making process, the interaction between states and the federal government through incentives and policy agenda, the diffusion of new and existing policy ideas, and the socioeconomic conditions underlying the overall welfare of society.

The growing state-level standards movement and school reform initiatives which began in the 1990s, a primary outcome of the publication of A Nation at Risk, have

demonstrated the influence of financial incentives and a national education agenda. For many, the passage of NCLB marked a seismic expansion of this agenda and the

unprecedented influence of the federal government into local and state education policy. Recently, the Obama administration’s Race to the Top initiative used sizeable financial incentives to influence alignment of state and local education policy with federal agenda priorities (Finch, 2012; Kolbe & Rice, 2012). Wong and Langevin (2005) have explored the influence of this type of vertical migration on adoption of public school takeover policies. The authors hypothesized since the publication of A Nation at Risk, a growing influence of the federal government on state education governance, channeled through grants and fiscal incentives, has flourished. Unfortunately, poor modeling of vertical migration and diffusion influenced the significance of the measure. While some evidence has suggested states and local governments are beginning to see a return to a more local power base, the federal government’s use of a “carrot-and-stick” approach to policy influence during the most recent era has become clear. Simply, in the current era, the federal government has been quick to reward states that mimic various policy agendas while maintaining high standards for accountability and performance (Marsh & Wohlstetter, 2013).

Consequently, the extant literature on state policy adoption provides foundation for studying incremental changes to compulsory school attendance policy during this era. The current wealth of policy adoption and innovation studies can be traced to the works of Walker (1969) and Gray (1973), who both made sizeable contributions to the internal determinants and diffusion forces affecting public policy processes and outputs.

diffusion processes associated with state policy innovation. Walker expanded public policy studies by focusing on a set of new characteristics influencing the policy process, which up to the time of publication had concentrated on the economic interpretation and rational choice theory of public policy. Walker’s analysis included measures of state-level political characteristics, including political party competition and political turnover, as well as the interstate and regional influences promoting the diffusion of policy ideas. Walker concluded that regional decisions to innovate, strong state economic conditions, and political professionalism all influence state policy outcomes (Walker, 1969).

Gray (1973) expanded Walker’s work and the general concept of regional diffusion. The author concluded adoption of state-level policy has been directly

proportional to the number of interactions state policy makers have with each other; the more diffusion occurring across a shorter period the faster a state adopts policy. These can include the regional adoption of larger policy groups or the influence of single-policy adoptions in single or multiple bordering states. As noted by Berry (1994), policy

innovation studies prior to 1990 developed within one of the two frameworks proposed by Walker and Gray: however, the statistical techniques available in these early studies often limited the research to a single conceptual approach.

Berry and Berry (1990) have provided the foundational work for the wealth of current policy adoption and innovation studies, positing policy outputs are relative to the amount of resources within a state set against the changing circumstances preventing successful implementation. These changing circumstances include the fiscal incentives and overall economic health of states, as well as the internal determinants and regional diffusion processes influencing political systems. Although Berry and Berry’s

conclusions markedly resemble Walker and Gray’s, the authors’ use of Event History Analysis (EHA), which provides robust methodologies for the analysis of the timing and causes of events, has become the standard for policy adoption studies.

Internal Determinants: Political composition

The internal political characteristics of states often influence policy outputs. These characteristics include the unified political party control of both the legislative and executive branches of state government, as well as the partisan control of the various houses of state legislatures. In addition, the ideological composition and political polarization of state policy-making bodies have shown significant effects, reflecting the direction of policy outcomes during specific legislative sessions (Lewis, Schneider, & Jacoby, 2015; Roch & Howard, 2008). Recent literature on school reform policy

adoption finds states with liberal governments are more apt to innovate and reform public schools through internal, existing systemic processes, while states with more conservative governments seek to reform public schools through support of non-traditional, external education means (Mintrom & Vergari, 1997; Renzulli & Roscigno, 2005; Wong & Langevin, 2005). Within the current reform era, this assumption is forefront as the political responsibility for education spreads across various political systems and as states soften their position on various reform initiatives.

Research studies on education policy find mixed results regarding the influence of unified political party control and the political ideology of state legislatures. For

example, in a study of state-level adoption of secondary and tertiary dual-enrollment policies, Mokher and McLendon (2009) found significant effects on policy outcomes in states with unified Republican legislative control, regardless of the political party

affiliation of the state governorship. The findings also evidenced significant effects for prior school reform initiatives commonly embraced by more conservative ideologies, which the authors conclude is evidence of both a “softening” and a “tinkering” of education policy outputs at the state level (p. 272). Studies of recent school choice and state takeover reform initiatives (Mintrom, 1997, 2000; Wong & Langevin, 2005, 2007), charter school policy adoption (Renzulli & Roscigno, 2005), and state education finance reform (Roch & Howard, 2008) have found similar results for the influence of

conservative political determinants on reform policy adoption. Conversely, policy research exploring changes to current educational governance structures has found strong effects for the influence of more liberal ideology. Curran (2015) found states with greater Democrat control of state legislatures have a greater likelihood for adopting policies affecting early childhood education, specifically the addition of statewide universal preschool programs into public school systems, reflecting a dichotomy in the legislative approach to school progress.

Policy agendas start with public concern about a societal issue. These issues often grow through increased attention in various arenas and within policy subsystems and include numerous actors who influence the agenda-setting process. The influence of special interest groups, most notably public sector teacher unions, has a significant effect on state policy adoption as the era of reform in education continues to expand. While state governments are the most dominant figures in education policy implementation, the influence of public sector teacher associations demonstrate the complexities of policy contexts (Cowen & Strunk, 2014; Hartney & Flavin, 2011; Poole, 1999). Consequently, teachers unions have played a significant role in structuring the political system and

selecting the actors responsible for policy action (Moe, 2009). Cowen and Strunk (2014) determined teacher unions are instrumental in state and federal elections and in

controlling local school board membership, and Hartney and Flavin (2011) concluded teacher unions are one of the most important actors across all levels of education policy making.

Several researchers have explored the influence of teacher unions on education policy outcomes, exploring the influence of unions on performance pay and incentive reforms (Belfield & Heywood, 2008), school finance policy (Roch & Howard, 2008), and education expenditures and outcomes (Lovenheim, 2009). Most evident across the literature is a strong opposition by teachers’ unions to modern education reform initiatives, specifically the implementation of school choice, merit pay, and teacher accountability. In a study of state charter school policy adoption, however, Giersch (2012) found more anti-union legislative adoption in states with the strongest union membership. The author hypothesized this significant finding represents a backlash against once traditional policy actors seen as challenging new reform initiatives. While many of these studies have found mixed results as to the significant level of teacher union influence on policy outcomes, the inclusion of union membership and political activity demonstrates the importance these actors play in the education policy process.

Internal Determinants: Socioeconomic

Similar to the internal political challenges associated with policy process, state socioeconomic conditions also present a series of challenges for state policy makers. The influence of rational choice models on early policy studies provides the impetus for the inclusion of economic characteristics on policy outcomes. Long before Walker’s seminal

work on state innovativeness, researchers had correlated measures of state economic condition with public policy outcome. Inclusive in this literature were different

indicators concerning the vibrancy of state economies, including individual income, state-level gross domestic product, state unemployment rates, revenues, and legislative

expenditures designed to support specific policy agendas (Berry & Berry, 1990; Easterly, 2014; McLendon & Cohen-Vogel, 2008; McLendon et al., 2006; Mokher & McLendon, 2009; Wong & Langevin, 2005, 2007). Common across the literature is the relationship between economic strength and general policy outputs.

Current research on education policy adoption and innovation has described how states react to challenges in economic condition, often becoming more innovative by employing nontraditional methods during hardship and continuing policy stasis during periods of healthiness. For example, in their recent studies of charter school and school takeover policy, Wong and Langevin (2005, 2007) incorporated the fiscal health of states as a determinant in policy outcomes, noting fiscal constraints within the economy have had a significant effect on current education reform policy outputs. There has also been evidence of substantial education policy outputs resulting from the recent economic recession. Generally, as states recovered from hardships and constraints on their ability to fund public education, policy actors developed a series of innovations to garner money from the Race to the Top program. As Marsh and Wohlstetter (2013) noted:

RTTT provided ‘political cover’ for states to assert more power and to initiate reforms in the areas of teacher compensation, accountability, and closing low-performing schools—areas states were unable to touch in the past because of strong opposition from interest groups. (p. 2)

Most important to this analysis, however, is the relationship between economic laws and compulsory schooling policy. From both historical and empirical perspectives, the influence of economic laws on compulsory schooling legislation is well documented, from early attempts at compulsory education policy, which coincided with child labor laws during the late 19th-century industrial boom (Katz, 1976) to the more recent effects of minimum wage laws on high school enrollments (Chaplin, Turner, & Pape, 2003).

Changing state demographic conditions also have an effect on policy processes. Changes in student enrollments at various levels, graduation rates, dropout trends, changes in student and school ethnicities, differences between urban, suburban, and rural school systems, and education attainment of various populations have all become

common areas of interest in education research. For example, the recent increase in 2-year college enrollments has had significant effect on dual-enrollment policy adoption at the state level (Mokher & McLendon, 2009), the level of education attainment within a state and how years of education influence performance accountability measures for higher education (McLendon et al., 2006), and the effects of increasing minority student populations on the likelihood of school choice policy reform (Wong & Langevin, 2007). Interstate Migration and Regional Diffusion

In addition to the internal, socioeconomic factors, early literature on state policy innovation includes the external influences of policy migration and the diffusion of ideas (Gray, 1973; Walker, 1969). Policy migration and diffusion processes explain the transfer of policy ideas through an interstate and regional exchange of policy agendas. Shipan and Volden (2008) have identified four areas of policy migration recognized in the extant policy literature—learning from other state policy decisions, the influence of

economic competition between states, imitating the policy action of another state, and coercion using incentives to drive policy action. While the methodological approaches to policy innovation and adoption have changed, the influence of interstate policy diffusion has remained constant in the empirical literature (Berry & Berry, 1990; Easterly, 2014; McLendon & Cohen-Vogel, 2008; McLendon et al., 2006; Mokher & McLendon, 2009; Wong & Langevin, 2005, 2007).

It is important to note state policy activity can sometimes influence federal policy agendas as well. As Mossberger (1999) noted, the success of state-federal diffusion occurs within the context of “laboratories of democracy” where state-level policy information provides lessons for federal agenda setting. A number of recent state level policy initiatives, including minimum wage legislation and same sex marriage, have defined this relationship and illustrated how state-level policy decisions can influence federal agendas (Ferraiolo, 2007). For example, since 2001, a number of states have responded to the federal government’s inability to act on minimum wage legislation by increasing the hourly minimum wage within their state. To date, the recent adoption of incremental shifts in state level compulsory school attendance age has had little effect on the larger macro education agenda. One thing is certain, however: A continued campaign exists to make students stay in school longer as a means to increase educational

outcomes.

Summary of Related Literature

Over the last two decades, there has been an unprecedented growth in federal and state government involvement in education policy. From the state level, this growing influence has pushed a series of mandated reforms aimed at greater accountability.

Interestingly, it has also offered an umbrella for “tinkering,” providing cover for small incremental shifts in public policy. Compulsory schooling laws continue to be one such area, where small incremental changes have followed the development and growth of larger education initiatives. As previously mentioned, these incremental shifts in policy are often the product of a bound political process. With limited information and within limited legislative periods, policy actors respond to the changes in determinants and regional influences from a constrained perspective, leading to small incremental action in the policy venue.

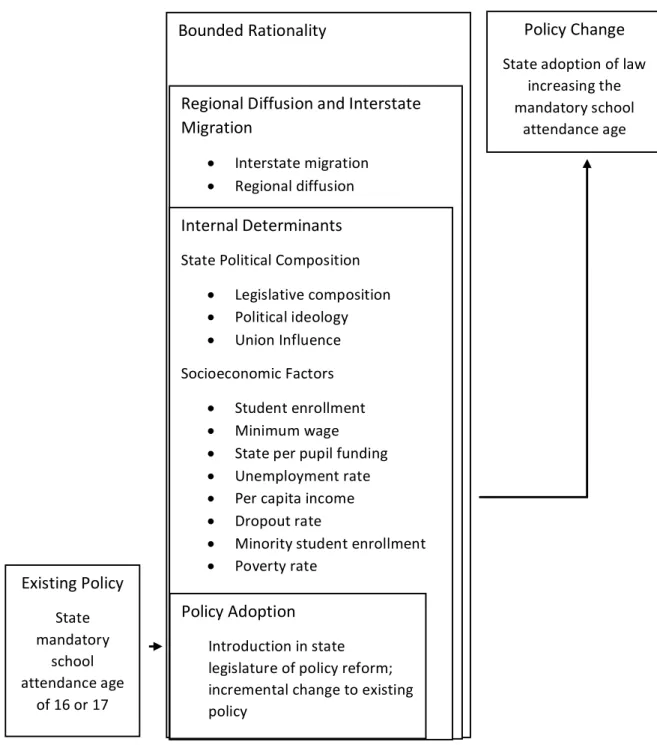

This chapter has presented a conceptual approach to the study of incremental policy change to compulsory schooling laws framed through the lens of bounded rationality. As existing policy becomes part of a new agenda, rational political actors’ access limited information within constrained times in an effort to address public policy issues. Within this context, economic conditions and political climates, as well as the actions of other actors (states), influence final policy outcomes. This dissertation explores these contexts by employing the internal determinants and diffusion processes evidenced in the extensive literature on state policy adoption and innovation. The political composition of states, including the legislative makeup and ideology of state legislative branches, economic indicators of state fiscal health, and the policy actions of neighboring and regional states represent the specific areas of focus guiding this research. Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework of the study and illustrates the influence of constrained information on incremental policy processes.

Research question: What characteristics influence the probability of policy change increasing the mandatory school attendance age from 1994 to 2011?

Figure 1. Bounded rationality, policy determinants, and the diffusion processes for incremental policy change increasing the mandatory schooling age

Policy Change State adoption of law increasing the mandatory school attendance age Existing Policy State mandatory school attendance age of 16 or 17 Bounded Rationality Regional Diffusion and Interstate Migration • Interstate migration • Regional diffusion Internal Determinants State Political Composition • Legislative composition • Political ideology • Union Influence Socioeconomic Factors • Student enrollment • Minimum wage • State per pupil funding • Unemployment rate • Per capita income • Dropout rate • Minority student enrollment • Poverty rate Policy Adoption Introduction in state legislature of policy reform; incremental change to existing policy

CHAPTER 3 METHODS

The following chapter provides an overview of the methodological approach for the study. The first section provides a brief review of the conceptual framework for the research and outlines the specific research questions. A second section mirrors similar policy adoption studies and presents a description of the research methodology, including variables, data coding and sources, the overall hypotheses used to develop the empirical specification, and details of the Cox proportional hazard model. The third section

presents the empirical specification for analysis followed by a final section examining the limitations of the study.

Purpose and Research Questions

This study explores the factors influencing incremental policy change increasing the compulsory school attendance age from 1994 to 2011. The following general research question guides the study:

What characteristics influence the probability of state policy change increasing the mandatory school attendance age between 1994 and 2011?

The changing complexities of state education policy making are vast and include multiple determinants and diffusion factors. A review of prior research on state education reform and policy adoption narrows the study into three focused research questions:

Research Question 1: What characteristics of state political composition influence the probability of policy change increasing the mandatory school attendance age?