Logistic practises of

Swedish Omni-Channel

retailers

PAPER WITHIN: The Swedish Retail Environment AUTHOR: Estelle Roser & Beatrice Jonsson TUTOR: Hamid Jafari

Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this research is to explore logistic practises adopted by Swedish

omni-channel (OC) retailers, and to investigate whether there are any differences between the logistical practices implemented by larger OC retailers and small and medium sized retailers (SME).

Design/Methodology/Approach: Empirical data has been gathered through a questionnaire, that

was handed out to various Swedish OC retailers which stands for the studies primary data. Secondary data has been collected through a literature review which is the basis for the reference of theory. The combined findings have then been used to analyze the empirical data and come to the authors final conclusions.

Findings: It is found that the choice of logistic practises among Swedish OC retailers are greatly

influenced by customer expectation, resources in terms of capital, employees, facilities, technological advancements, expertise and level of online orders. The study has further shown that there is more similarities between large OC retailers and SME’s rather than differences, which indicates that the authors model can be applied to the majority of Swedish OC retailers irrespectively of their size.

Research Limitations: The study has been conducted on Swedish OC firms and is thus limited

to the retail market of Sweden. Qualitative data is collected in the construct of a questionnaire limited to the logistic areas delivery service, distribution setting, fulfilment strategy, returns management, specialization and visibility.

Theoretical Implications: The study broadly provides further contribution to the evolving body

of ongoing academic literature on OC retailing logistics and whether certain logistics practices are more prevalent in large firms as opposed to SME’s. The authors highlight the differences between larger OC retailers and SME’s when it comes to visibility of assortment, picking location, transportation service, integration and allocation of product

Managerial Implications: The empirical contributions of this study showcases the most

adopted logistics variables among Swedish OC retailers and can thereby be used to support managers when designing and configuring their logistical strategies

Keywords: Logistics, Retail, Omni-channel, SME’s,

This exam work has been carried out at the School of Engineering in Jönköping in the subject are omnichannel retail- The work is a part of three-year university Bachelor programme

Sustainable Supply chain Management. The authors Beatrice Elizabeth Iona Jonsson and Estelle Roser take full responsibility for opinions, conclusions and findings presented.

Examiner: Ewout Reitsma Supervisor: Hamid Jafari

Scope: 15 credits Date: May 17, 2020.

Introduction 5

1.1 Background & Problem Formulation 5

1.2 Purpose & Research Questions 7

1.3 Delimitations 8

1.4 Disposition 8

2. Theoretical Framework 10

2.1 Retail and Omnichannel 10

2.2 Delivery service 12 2.3 Distribution settings 15 2.4 Fulfillment strategy 17 2.5 Return management 18 2.6 Specialization 20 2.7 Visibility 21

3. Method and Implementation 24

3.1 Research Design 24

3.1.1 Connection of research questions and the method used 24

3.1.2 Choice of methodological instruments 25

3.2 Data collection & Analysis 25

3.3 Validity and Reliability 27

4. Results 29

4.2 RQ 2. Are there any differences in business logistics models used by large OC firms and

smaller SMEs? If so, what are the differences? 33

5. Analysis & Discussion 38

5.1 RQ 1. What are the most common logistics practices currently adopted by Swedish OC

retailers? 38 5.1.1 Delivery service 39 5.1.2 Distribution settings 40 5.1.3 Fulfillment Strategy 41 5.1.4 Return Management 43 5.1.5 Specialization 44 5.1.6 Visibility 45

5.1.2 RQ 2. Are there any differences in business logistics models used by large OC firms

and smaller SMEs? If so, what are the differences? 47

5.2.1 Delivery Service 48

5.2.2 Distribution setting 49

5.2.4 Return management 52

5.2.5 Visibility 52

6. Conclusion & Further Research Areas 54

6.1 Theoretical implications 54

6.2 Managerial implications 57

6.3 Future research 57

7.0 References 59

1. Introduction

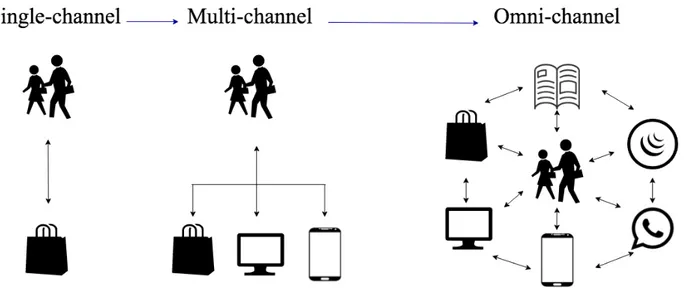

This chapter introduces the intention of the study as well as its concepts, investigating the transition from a multi-channel approach to retailing to an omni-channel approach. A brief introduction to the theoretical background of the subject is also provided followed by the practical implications that are discovered. The structure of the findings are also introduced in this chapter.

1.1 Background & Problem Formulation

More and more consumers shop online every year. According to a study made by PostNord (2019), 62 percent of Nordic residents shopped online every months in 2019, which is an increase of two percentage points compared to 2018. The growth of e-commerce has made significant changes in the retail environment where the recent phenomenon omni-channel (OC) retailing, referred to the combination of mobile, traditional physical stores and e-tailing, is becoming the future of e-commerce. The growth towards OC retailing has forced retailers to modernize their strategies and to redefine their business models (Marchet, Melacini, Perotti, Rasini, & Tappia., 2018). It is no longer sustainable for retailers to exclusively run a single channel, therefore traditional retailers are searching to establish an online presence, while e-tailers are searching for different options to establish a physical presence. The challenges associated with this transition is to create a seamless experience for the customer as well as the internal processes. Retailers who have developed an online presence have mainly seen this as a detached channel with little integration to the overall operation (Deloitte, 2015). This is referred to multi-channel (MC) retailing, where the aim is to manage and optimize performance of each individual channel in parallel to the other established channels (Rai, Verline, Macharis,

Schoutteet, & Vanhaverbeke, 2019). The retail landscape is however changing in a rapid pace where customers are demanding more information about delivery times, stock levels and various shipping options regardless to which channel they are using. No matter whether customers use a mobile device, a computer or visit the retailers physical store, they expect the same amount of information and level of service (Deloitte, 2015). The ongoing growth of the e-commerce market proposes many challenges as well as opportunities. The fast pace advances made in the online industry has resulted in traditional retailers adapting to the online market. Traditional retailers and e-tailers have to become accustomed to the development of OC strategies as the 21 century has become more demanding, where single channels are no longer a long-term solution (Deloitte, 2015).

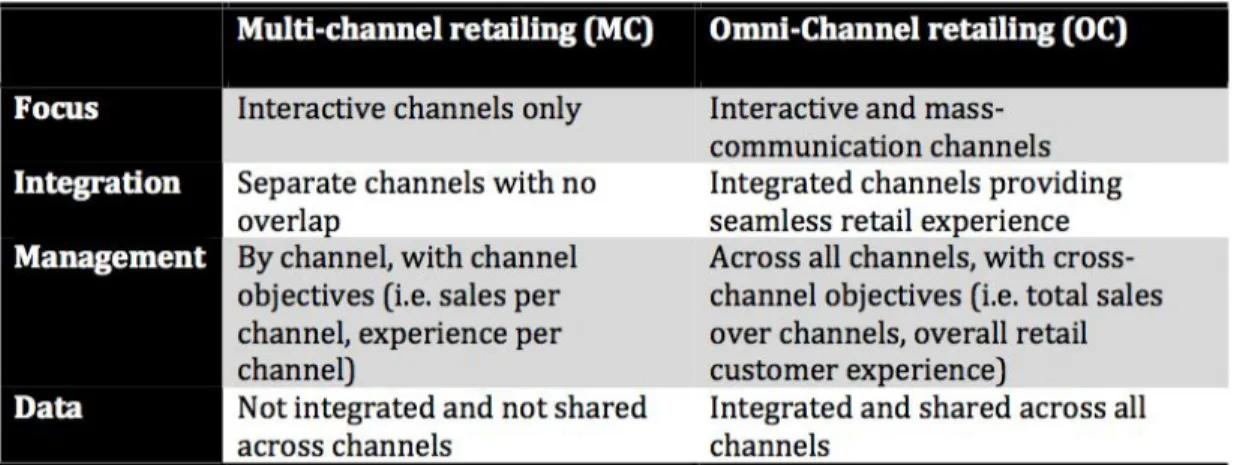

Figure 1.1.1: Differences between multi-channel retailing and omni-channel retailing. Source: (Verhoef, Kannan, P, & Inman, 2015)

The shift towards OC has required major significant changes in retail logistics (Kembro, Norrman, & Eriksson, 2018), which includes all decisions regarding products and needed services, as well as how to handle raw materials, product processes, storage, customer deliveries and after sales services (Chapman, Soosay, & Kandampully, 2003). However, this task is not straightforward as firms who implement an OC strategy must find new solutions of how they should consolidate and coordinate their traditional and online flows to be able to offer a seamless shopping experience (Marchet et al., 2018).In this study, the modernization of business models is referred to business logistical practises that results in greater efficiency, which will help firms to reach the goal of a seamless OC. According to Piotowicz and Cuthbertson, (2014), the

logistical practises that need to be addressed in a retail environment are delivery options, product availability, returns management and inventory management.

However, previous studies have mainly focused on the design of business logistic models in MC (Larke, Kilgour & O’connor, 2018; Hübner, Wollenburg & Holzapfel 2016; Cao, 2014), while there is still a lack of business logistic models from OC firm perspective. The literature also has a lack of conceptual and empirical evidence. Additionally, the literature contributions commonly have a single focus on specific logistical variables (e.g. inventory integration, delivery mode, picking location etc) and lack an integrated perspective (Saroukhanoff & Aryapadi 2016; Fisher, Gallino & Xu ,2019; Zhang, Xu, & He 2018). Furthermore, the small amounts of empirical contributions are still related to a minor number of countries with an insufficient amount of quantitative analysis (Marchet et al., 2018). The main quantitative studies found on this subject is conducted by Hübner et al, (2016) and Marchet et al, (2018) who have defined a framework where they classify and describe key logistic variables currently most adopted by OC firms. Furthermore it has been found that there is a lack of studies investigating if there exist any differences regarding the logistical practices adopted by small medium enterprises (SME) and larger OC firms (Amin, & Hussin, 2014). SME take a significant role in many economies of the world. This is a result of the added contribution they provide by creating employment and facilitating regional development along with innovation (Di Fatta et al., 2018). Thereby

positively impacting the economic stature of a country (Shemi & Procter, 2018). There are many studies conducted on the adoption of e-commerce on SMEs, covering both SMEs in developing (e.g. Shemi & Procter, 2018; Kabanda & Brown, 2017; Al-Bakri & Katsioloudes, 2015), along with developed countries (e.g .Di Fatta, Patton & Viglia, 2018; Grant, Edgar Sukumar & Meyer, 2014). However, there have been difficulties when adapting to the online market, as the SME sector has a limited amount of resources and expertise. In the past, there was concern regarding the relevance of e-commerce along with the cost and strategy that come along with it. Resulting in a limited engagement of e-commerce activities. But as online sales have steadily grown, such concerns are no longer accurate as internet and web-based technologies are extensively viewed as an important element of effective sales (Di Fatta et al., 2018). The Italian fashion market is a good example of such change. In 2016 the Italian fashion market had an approximate value of 90 billion euros where the SME sector stod for more than half of the market value. The key factors that carried the positive performance were the increase in export and e-commerce (Di Fatta et al., 2018). Therefore, this study has deemed it interesting to identify if there is differences in

logistics practices adopted by large OC retailers and SME’s.

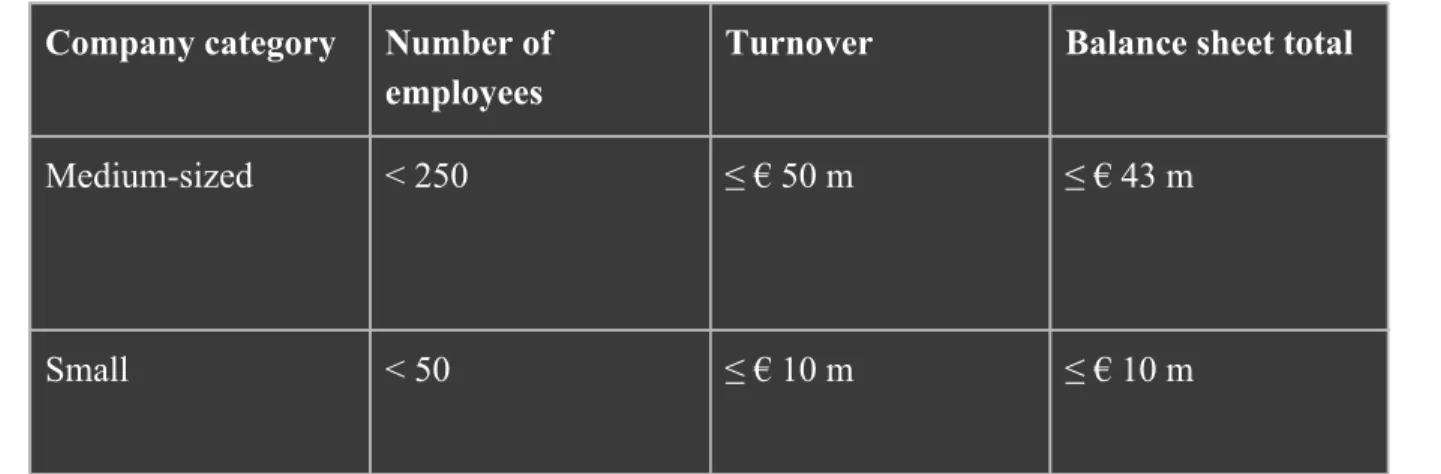

The study has chosen to define SMEs according to European Commission (n.d), who state that the two main factors that determine whether a firm can be classified as a small and

medium-sized enterprise (SMEs) are, (1) the number of employees and (2) the annual turnover or total balance sheet. The table below illustrates the requirements for firms to be categorized as SMEs:

Company category Number of employees

Turnover Balance sheet total

Medium-sized < 250 ≤ € 50 m ≤ € 43 m Small < 50 ≤ € 10 m ≤ € 10 m

Figure 1.1.2: Definition of SMEs. Source: European Commission (n.d).

1.2 Purpose & Research Questions

The purpose of this research is to explore logistic practices currently adopted by OC retailers, and to investigate whether there is a difference between the practices implemented by larger OC retailers and SME’s. As the literature found focus on logistics practices adopted OC retailers retailers in a minor number of countries this study will, therefore, delve into the logistics

most money on purchasing products online when compared to the Nordic countries, hence a strong argument for choosing to conduct a study on the Swedish OC market. To fulfil this aim, the following research questions have been established:

RQ 1. What are the most common logistics practices currently adopted by Swedish OC retailers? As literature covering OC strategies mostly focus on specific logistical variables (Saroukhanoff & Aryapadi 2016; Fisher, Gallino & Xu ,2019; Zhang, Xu, & He 2018), and how retailers transition from a multi-channel strategy to an OC strategy (Larke, Kilgour & O’connor, 2018; Hübner, Wollenburg & Holzapfel 2016; Cao, 2014), there is little research that explores the differences between large OC retailers and SME’s, thus room for further contributions within this area. It is therefore of interest to explore if there are any differences between how larger OC firms and SME’s manage their logistical practices. To fulfil our second purpose, the research question below is put forward.

RQ 2. How do large OC retailers and SME’s differ in regards to their implementation of business logistics models?

1.3 Delimitations

The study has been conducted on Swedish OC firms and is thus limited to the retail market of Sweden. Qualitative data is collected in the construct of a questionnaire limited to the logistic areas delivery service, distribution setting, fulfilment strategy, returns management,

specialization and visibility as the scope would be too wide otherwise. The study has mainly focused on retailers physical products, thus the results can not be generalized to the food industry.

Furthermore, the course project conducted by the class of 2018 who focused on SME’s has two more logistical areas added (visibility and specialization), the authors, therefore, had to contact the larger OC firms once again regarding these focus areas whereas only a few answered. As all the information needed is not possible to collect by a website, there will be an information gap. Lastly, some of the retail firms only answered a few of the questions in the questionnaire, which means that there will be a lack of complete information.

1.4 Disposition

In the first chapter, an introduction of the topic is presented motivating why the topic is of interest. This is executed through a project description including purpose, research questions and the delimitations that narrow the study down forming an achievable goal.

The second chapter presents the methodology used to execute the study and why the tools used are of importance. This is done to ensure that the study is robust and that the intended results are possible and convincing. The methodology, therefore, consists of research strategy, research methods and the research process.

Chapter three introduces the theoretical background of the study as well as puts forward the theoretical framework used to investigate the possible logistics models used by OC retail firms. The models are based on the logistic areas delivery service, distribution setting, fulfilment strategy, returns management, visibility and specialization.

The findings from the empirical data collected from the questionnaires are introduced in chapter four. Where the structure of the findings follows the structure of the theoretical framework. The findings are divided into groupings of bigger OC firms and SME’s.

Chapter six discusses and analyzes the findings in parallel to the theoretical framework to answer the aim of the study. The study thereafter ends with a conclusion and implications summarizing the chapter and research paper.

2. Theoretical Framework

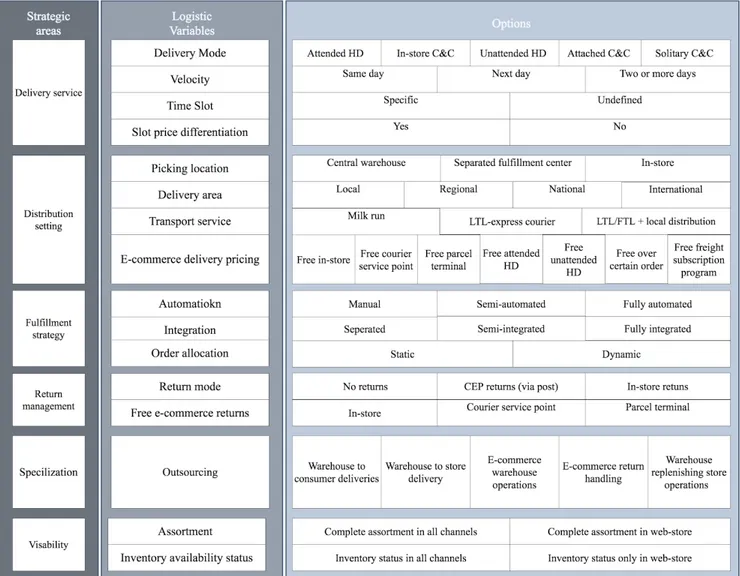

In this chapter the theoretical framework of the study is presented and illustrated in figure 2.1. The framework presents and describes the logistics variables that retailers engage in when operating in an omni-channel business environment. The framework is structured into six main strategic areas that are connected to retailers decision and strategy planning: delivery service, distribution setting, fulfillment strategy, returns management, specialization and visibility. Thereby each strategic area is described giving a better understanding of their relevance when evaluating a omni-channel strategy. The framework is based Marchet et al. (2018) rendition of Hübner et al. (2016)original framework.

The two logistic areas visibility and specialization have been added to the framework presented by (Marchet et al., 2018). Gallino and Moreno (2014) state that there is a growing trend in channel integration, hence adding relevance to inventory availability across channels. This topic has further been explored by Peinkofer and Howlette (2016) who discuss the importance of disclosing product availability in e-commerce as well as Cui, Zhang and Bassambo (2019) who explore the relationship between product availability and customer purchasing behaviour. Thereby supporting the relevance of adding inventory availability to the theoretical framework. Outsourcing is a broadly discussed topic in regards to logistics, where Kalinzi (2016) examines the overall impact outsourcing has on organizational performance where multiple sources explore the relevance and impact of outsourcing. For example, König and Spinler (2016) delve into the implications of risk management on supply chain vulnerability when outsourcing shipping services. It has thereby been deemed relevant for this study.

2.1 Retail and Omnichannel

Professor Malcolm P. McNair present a hypothesis for retail development where it is stated that retailers will move through a certain pattern as they grow and develop. The hypothesis expresses that new retailers will usually enter the market as low status, low margin, low price driver. The retailer will there on progress and form a more secure company with increased investments and higher operating costs. The retailer will then eventually evolve into high cost, high price

company with new challenges and will be susceptible and vulnerable to other competitors. Who have also moved through the same pattern. This pattern is what McNair named “The wheel of retailing”. An example of retailers moving through such pattern is big Departments stores, who first where in competition with smaller retailers. They have then moved on to compete with discount houses and supermarkets, thus vulnerable to new competitors (Hollander, 1960).

Hollanders (1960) work was one of the first to systematically draw attention to innovation with in retailing.

Due to the rapid growth of innovation and digitalization, the world of retailing has changed radically during the last two decades (Verhoef, Kannan, & Inman, 2015). In the past, customers had to visit either retail stores or a warehouse if wanting to make a purchase. According to the yearly report published by Svensk Handel in 2019, 32 percent of Swedish retailers operate physical boutiques in 2017 which had a turnover between one and five million SEK. However, in line with the commercialization of the Internet, retailers recognized the advantages of websites. They came to a realization that the use of websites made it possible to advertise

merchandise to a much larger audience instead of just reaching customers who physically visited the stores. These actions, in turn, lead to the creation of online product catalogues. This was the beginning of the online sales market. Retailers now begun to realize the possibilities of reducing costs. With an increased number of online sales, retailers could not only reach a much broader audience but also replace large stores at expensive locations to smaller storage units, which is how many of today's big retailers started their journey. However, the rapid growth of the Internet did not only affect retailers but consumer behaviour as well resulting in the consumers dictating the way forward(Weiland, 2016).

The next step of development in retailing business was the emergence of mobile devices offering Internet access. Customers now had a third purchase option. This development affected retailers existing business practices heavily, which laid the ground for multichannel strategies that utilize multiple sales channels. In the beginning, these strategies mainly involved the decision of whether a new channel should enhance the current channel mix. This decision concerned both traditional physical store retailers as well as new online retailers who had to decide whether they should add an offline channel as well (Verhoef et al., 2015). From an operational perspective, retailers favoured keeping their traditional offline and online channels separated (Gallino and Moreno, 2014), which meant that retailers operated individual channels in parallel and uncoordinated (Beck and Rygl,2015).

As time passed problems were detected within the multi-channel model where the most prevalent was the lacking information flow among channels. Thus, often resulting in company

cannibalization where channels within the same brand started to compete amongst each other for customers by presenting different prices, discounts, delivery options and return policies. Hence the solution to the problem resulting in an omni-channel strategy. The omni-channel strategy views the customer as the focal point. Customers are thereby able to seamlessly decide which channel is of preference. Receiving an unchanging amount of satisfaction from the shopping experience regardless of channel (Weiland, 2016).

Figure 2.1.1: History of the retail environment.

2.2 Delivery service

The delivery mode is one of the most important consideration for customers when choosing a webshop from which to make a purchase (PostNord, 2019) and is, therefore, one of the most critical logistic activity for the online channel (Lim, Jin and Srai, 2018). According to Hübner, Wollenburg and Holzapel (2016), omnichannel retailers can offer several delivery modes. However, both Lang and Bressolles (2013) and Hübner et al (2016) reveals that home delivery (HD) and click and collect (C&C) are the two most common delivery modes provided by retailers, as these options are customers initial demand when ordering online (Comeos, 2018; DPD Group, 2017). HD can either be unattended HD, which means that the customer does not need to be home when the retailers logistics provider deliver an order, or attended HD, which requires the customer to be present when receiving their goods. Even though the type of delivery mode provided by the retailer largely depends on the geographical area as well as the nature and size of the product (PostNord, 2019), the most dominant mode when it comes to home deliveries is attended home delivery (Buldeo Rai, H., Verlinde, S., Macharis, C., Schoutteet, P., &

Vanhaverbeke, L. 2019). C&C means that the customer receives their products at a given pick up point, which according to Lang and Bressolles (2013) usually is the retailers store (in-store C&C), a drive-through centre located close to the retailers store (attached C&C) or a locker point or parcel point such as post offices (solitary C&C). According to Postnord (2019), freedom of choice is important for e-commerce consumers who have made online shopping an increasingly part of their daily life. They state that for those who shop online often, convenient deliveries are that contribute to simplicity in daily life is significant. Furthermore, Rai et al., (2019) reveals that customers prefer to receive their products to an address of choice to minimize unwanted travel to and from retail stores. This statement contradicts a further study made by PostNord, (2019), which found that sustainability has become one of the most important issues for many Nordic customers. They state that customers nowadays are highly interested in making conscientious choices when they shop online, where three out of four online customers reveals that they

always, fairly often or sometimes reflect over what conditions the products they intended to buy are transported.

Figure 2.2.1: Consumers within the Nordic countries focused on sustainability. Source: PostNord (2019) However, Wollenburg, Holzapfel, Hübner, & Kuhn, (2018)state that it is a recent phenomenon for OC retailers to offer diverse delivery and pick-up options for their customers across channels. However, as retailers stand for last-mile transportation costs, it opposes many financial and sustainable challenges as it includes home delivery, parcel terminal and postal courier service point. When the customer chose HD, retailers transport their products by courier, while orders picked up in the store (in-store C&C) are transported with the products delivered to stores, thus retailers have the possibility to reduce additional transportation costs as well as their

environmental footprint (Gao and Su, 2016; Bernon et al, 2016). Therefore, many Omnichannel retailers are encouraging their customers to pick up their orders in-store as this is both more economically and environmentally beneficial from a retailers perspective, by offering deliveries to the stores for free and home deliveries at a certain cost (Gao and Su, 2016; Bernon et al, 2016). According to Hübner et al (2018) pick up in-store also increase store traffic and ultimately higher store sales. Although home deliveries are associated with higher CO2

emissions and logistic costs, many retailers have realised that offering home deliveries for free can become a competitive advantage over other (Wollenburg et al., 2018). According to

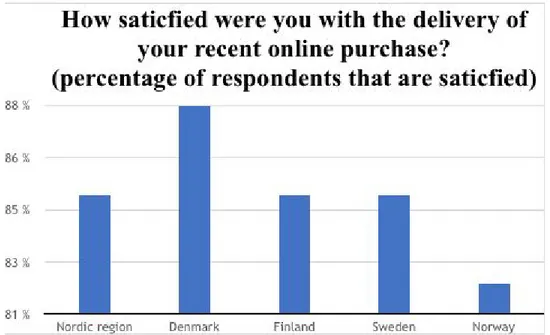

PostNord (2019) just eight out of ten Nordic e-commerce customers are in general satisfied with their deliveries, where Danes are the ones most satisfied. PostNord (2019) states that this result is probably due to advantageous logistic conditions. Denmark is the smallest country in terms of land area, which entails shorter transportation distance as well as higher logistics efficiency. They also reveals that Denmark has a high population density, meaning a further advantage for more efficient transports. These advantages gives in turn Danish retailers a possibility to provide customers a greater freedom of choice when it comes to delivery options. For example, PostNord (2019) states that a larger share of Danish customers had their most recent purchase delivered to their home. They continue by arguing that this contributes to a higher level of customer

satisfaction. Another advantage of home deliveries is that additional services can be provided. Example of such services is carrying in or install the products, which typically increases customer satisfaction even further (PostNord, 2019).

Figure 2.2.2: How satisfied customers within the Nordic countries were with their latest online purchase, in percent. Source: Postnord (2019).

The delivery time is one of the most visible service element and depends heavily on customer requirements and what type of product the retailer offers (i.e. what industry). This is commonly referred to velocity, where the options can either be, same day, next day or two or more days. Fast deliveries can contribute to high customers satisfaction but are however, still a challenge associated with high costs for the retailer (Marchet et al., 2018). However, in the study made by PostNord (2019), the time that consumers are willing to wait for their online deliveries varies between countries. For example, they state that the Dutch have very high expectations, where more than a third expect to receive their purchase within one-two days. This is twice as high as in Belgium, Germany and the United Kingdom, and three time as high as in France, Italy, Spain and the Nordics. It is therefore important for retailers to analyze both the conditions and

expectations for rapid deliveries in the relevant market, to ensure e-commerce success (PostNord 2019). Align with previous contributions (Hübner et al., 2016b), the time slot can either be specific or undefined. The prior means that the customer can choose a specific time slot when they make the purchase, while the last one includes both HD without a pre-selected time slot and HD with an appointed time frame. Having a specific time slot typically requires OC retailers to have more advanced transportation systems where the retailers face higher cost-effective challenges (Marchet et al., 2018). Different from the study made by Hübner et al., (2016), Marchet et al., (2018) had put slot price differentiation as a logistic variable. Klein, Neugebauer, Ratkovitch and Steinhardt (2017) argue that the delivery process can be more effective when pricing the time slot differently, as they then can balance their use of time slot capacity better. However, price differentiation are still under development for many OC firms as this, again, requires more advanced IT systems and higher logistical coordination (Marchet et al., 2018).

2.3 Distribution settings

According to Marchet et al, (2018) the distribution setting within an OC environment contains three fundamental logistic variables: picking location, delivery area and transportation service. The picking location is the place where customers online order is fulfilled, where Alptekinoglu and Tang, (2005) states that the options can either be central warehouse (CW), separate

fulfilment centre and in-store. In-store picking is typically the first option for retailers who want to enter the OC business (Hübner, Kuhn, & Wollenburg, 2016). In this case, online orders are picked directly from the shelves at the retailer’s store. It is common that retailers use this approach as their entry model because it provides them with the opportunity to offer a full product range within the existing structures. As such, retailers are able to expand their business without investing in new logistical facilities while the future demand is yet uncertain. Hübner et al. (2016) also states that it is a less costly option for retailers to modify their existing stores than to build a completely new DC. They continue by arguing that when the online orders increase, this option becomes inefficient as retailers store layout usually is designed to display the

products and not to achieve efficient picking. The design will then limit the e-fulfilment volume. When this happens they state that it is more appropriate to use separate fulfilment centres, which avoids interaction between traditional and online channels. In contrast to in-store picking,

separate fulfilment centres are designed for picking a high volume of online orders, which will thereby result in higher efficiency. According to Hübner et al., (2016) this option also makes it easier for retailers to offer better information regarding product availability to their web shoppers, as these centres only keep inventory for the online channel. Retailers who have operated in the online channel for a while most often use centralized warehousing. In these warehouses the pickers handle both store and online orders, thus, more complex picking systems are typically required. An example of such retailer is Jula, who has one huge central warehouse located in Skara, from where they distribute their products to all of their retail stores as well as their online orders (Jula, 2004). However, Hübner et al., (2016) point out many advantages of a centralized warehouse. With consolidated inventory, retailers face higher turnover rates as well as lower inventory and inbound transportation cost because retailers can take advantage of deliveries with higher volumes to a single location. It also requires less links within the supply chain.

The delivery area for the online orders from each logistic facility is another key variable for OC retailers. According to Marchet et al, (2018) this can either be local, regional, national or

international. When it comes to the choice of picking location for online orders, Hübner et al, (2016) says that the delivery area for in-store usually has the shortest transportation distance to customers, while centralized warehouse typically faces longest transportation distance. However, cross-border e-commerce is steadily growing in all countries. PostNord (2019) state that in comparison to 2018, the number of europeans who had made a purchase online from abroad had increased by 11 million, which is equivalent to 8 percent. This shows that customers are

their original location. Another driving factor of cross-border purchasing is the fact that

customers have access to a much wider assortment, with better offers and lower prices. PostNord (2019) continue by arguing that as the high speed of internet connection is continuously

developing in all countries, e-commerce is expected to grow even more, meaning that the commerce from abroad in Europe will increase even more.

Furthermore, the next variable that the authors have chosen to include in this study is transportation service, as previous contributions made by Jothi Basu, Subramanian and

Cheikhrouhou (2015) have shown that this factor influences retailers overall cost of operating a business. The option that are included in this study are “milk run”, “express courier” and “Less than Truck Load (LTL) / Full Truck Load (FTL) + local distribution”. LTL and FTL has been chosen to be combined into the same option, as these seems to overlap for many retailers. The important aspect of this question is whether the products are transported to one point and from there locally distributed. When using milk run, retailers ensures that various online deliveries from different vendors can be managed with maximum capacity utilization and nominal costs (Brar. S. G., Saini. G., 2011). In LTL/FTL + local distribution, products are transported in either small packages delivered by couriers, or in a full semi truck from the fulfillment centre to the store or a local depot. This option is used to integrate the online and store orders on the same truck. Thus, the retailer can take advantage of reduced transportation cost for the C&C delivery mode (Marchet et al., 2016), while at the same time decrease their environmental footprint (PostNord, 2019). The choice of transportation service is influenced by product type and frequency of orders (PostNord, 2019).

Lastly, it has been showed that shipping prices greatly affects consumers decisions to buy, where as much as three out of four Nordic consumers have aboundate a purchase when they realised that they had to pay a shipping fee. It has also been found that Swedish customers expect to be able to pay invoices at no additional cost, and if this factor is not provided by the retailer, many swedes interrupts their purchase (PostNord, 2019). Therefore, retailers who incorporate a system that gives the customers an option of free shipping as well as invoices can receive increased product sales, customer retention as well as higher customer satisfaction. However, for OC retailers, free e-commerce shipping creates transportation costs that are not present in traditional retailing which can significantly impact profitability (Lewis, 2006). Furthermore, compared to the offline market, e-commerce opens new challenges for retailers, such as higher complexity of their logistical practises (Mangiaracina, Seghezzi, Perego, Tumino, 2019) and transaction systems (Postnord 2019). The authors therefore considers e-commerce delivery pricing as an additional logistic variable, where the different options are “free in store”, “free courier service point”, “free parcel terminal”, “free attended HD”, “free unattended HD”, “free over certain order”, and “free freight subscription program”.

2.4 Fulfillment strategy

The transition of retailer's supply chain processes in these changing environments are complex and require careful planning as well as execution. There are substantial differences when planning customer online orders in comparison to traditional store purchases. The online customer order goods in small quantities where the customer leaves all physical distribution activities for the retailer to handel. Whereas in the traditional physical retail setting the customer provides their own fulfillment service, as they pick products directly off the store shelf where they then physically locate themselves to the checkout lane. At last providing self home delivery or to other consumption points. Retailers also gain first hand connection with the customer by the physical distribution process (Ishfac, Defee, Gibson, & Raja, 2016). Online orders often require a pick-and-pack order fulfilment system that is labour intensive with high variable and merchandize costs with high capital investments. With a pick-and-pack strategy that is heavily influenced by manual labour. Retailers therefore run the risk of a high error rate due to human inaccuracy. As human performance is impacted by contextual factors, where personnel and environment are included. This often results in human errors that may lead to fulfillment

impairment, which is harmful and can lead to prolonged transportation times, damaged customer goods and decrease the service value provided by the retailer and decrease customer satisfaction (Giusti et al., 2019).

When dealing with e-fulfillment there are different strategies that retailers can undertake. Retailer can undertake the options of using manual procedures, introduce semi or fully

automated systems (Melacini et al., 2018). When using a manual procedure retailers will use a picker-to-parts system (Marchet et al. 2018). Although it is possible to automate fulfillment procedures, companies often chose to use manual material handling, especially SME’s, as to ensure high flexibility levels and reduce or avoid investments (Calzavara, Glock, Grosse, Persona, & Sgarbossa, 2017). Manual material handling is also most effective when receiving large orders (consists of many stock-keeping-units (SKU)) that retailers need to consolidate and has to be organized well (Merschformann, Lamballais, Koster, & Suhl, 2019). When utilizing a semi automated system conveyors will connect the various pick zones, but picking will still be carried out by manual pickers this is known as a pick-and-pass system. Parts-to-picker systems are however most often fully automated (Marchet et al., 2018) and often used to fulfil online orders as e-commerce warehouses often are large due to the fact that they need to contain a large assortment of product, that results in long traveling distances for pickers. Thus automated

parts-to-pick systems eradicates traveling time done by pickers. Thereby gaining higher pick rates (Merschformann et al., 2019).

Retailers are also able to choose if they want to fully separate their networks, where retailers will use dedicated resources, space and staff to fulfil online customer orders (Hübner et al., 2016b). A reason for conducting such a procedure is often a lack of necessities for integration, for example

know-how, requirements for picking, resources and infrastructure to mention a few. However this does not apply to every case as there is a possible threshold, as a percentage to where it might be more profitable to implement specific warehouses for online order distribution (Melacini et al., 2018). Retailers can also implement a semi-integrated system where existing resources are shared to be able to integrate online orders with the traditional physical channel picking process. It can also be more cost-effective to adapt already existing storage than invest in new warehouse facilities when first engaging in an online presence. Thus the logistics operations are centralized to the store location. Although a temporary solution to rapid growth or high seasonal demand can be to implement integrated OC warehousing, which is warehouses

dedicated to e-commerce as it is able to create a temporary capacity flow do handel the increase in demand. However with the increasing expectations arising from customers, OC retailers are heading towards a more decentralized approach. The path towards a more intricate and

decentralized distribution structure enhances the need to implement information systems that coordinate the information between and within channels. By implementing an integrated information system it could, for example aid the decision of where and how to fulfill customer orders in order to enhance service levels and decrease total cost. Information systems also create possibilities to increase visibility of available inventory across channels and makes it achievable to set aside inventory, prioritize, track customer orders and regulate return flows (Kembro, & Norman, 2019). Then there is fully integrated where optimal use of resources are used to lessen lead-times as well as stock-outs (Hübner et al., 2016).

Mahar and Wright (2009) propose a policy for dealing with the implications regarding the specifics of how many and which of an OC retailer location should be utilized for online fulfilment. The policy includes the classifications of an OC being either static or dynamic. Where a static allocation will pre-specify which location is responsible for handling the online sales for each region only showcasing the goods available in the specified region. Whereas the dynamic allocation will determine the online fulfilment obligations in real-time for every incoming online trade (Mahar, & Wright, 2009) where the customer is able to see the entire assortment of goods available and the responsibility (Marchet et al., 2018).

2.5 Return management

Swedish consumers return approximately 3,3 million products purchased online each year (Forssén, 2019). PostNord state that the reason for the increase in returns during the recent years is probably due to the increase in online purchasing (PostNord, 2019).

Customer returns is a procedure that is both a strain on the environment as well as something that creates irritation within the customer. Returns are often a result of the customers inability to inspect product quality before purchasing. As of lately there has been further focus put onto minimizing return rates not just due to environmental concern but also as a way to reduce costs. Swedish companies such as H&M are trying to reduce their returns by implementing artificial

intelligence (AI) to help customer select their correct size. As the retail sector have with the most returns are with in the fashion industry, as customers often purchase multiple sizes before

deciding on what items to keep. Even Zalando has started to use AI to ease customer navigation within size selection. Most Swedish customers are content with return process provided by retailers, it is however becoming more apparent that customer are putting greater importance on e-commerce return policies. Swedish consumers are willing to reject a purchase if not satisfied with the return policies offered, especially if the customer is female as one out of three women will refrain from a purchase. A good return policy is more than free returns, which has had a decrease in relevance since last year although still important (PostNord, 2019q2). As of customer satisfaction older customers are more often satisfied with return policies than younger customers. As the younger generation has more e-tail experience and therefore have higher expectations. When it comes to purchasing product from international e-tailers the Swedish customer is more likely to return goods to the United Kingdom and Germany whereas it is less likely that returns are made to the US and China. This is of relevance du to the fact as it shows where the Swedish customer have loyally and trusts in international return policies (PostNord, 2019q1).

Returns are a necessary aspect of retailing where the acceptance of online returns have become a crucial endeavour for retailers. Although the activity of return management is not a new aspect in retailing it has had an increase in importance due to the intersect of stores and online retailing. This has lead to further development of OC retail where customers are offered a smooth shopping experience across multiple channels consequently presenting new challenges within product returns management, as processes such as information systems, inventories and performance need to be integrated (Bernon, Cullen, & Gorst, 2016).

With the increasing self-assurance among customers and the utilization of electronic devices including laptops, tablets and cellular devices for research as well as purchasing goods online the environment of OC is grown in importance. As a result of the changing environment, there has been a shift in consumer purchasing decisions. Retail return policies now have a significant impact on where customers chose to spend their hard-earned money. This has resulted in a bigger variety of return options available including in retail stores, courier service points, parcel terminal or from the comfort of the customer's home (Marchet et al., 2018). It is important for retailers to not only focus on the customers repurchasing intention when viewing the loyalty of a customer. Return management is just as an important factor that needs to be taken into

consideration when viewing customer loyalty.

The framework visualizes the logistics options store returns, courier, express and parcel (CEP), and no returns. It also looks at the different options retailers offer when customers purchase goods from their online channel, which are in-store, parcel terminal, courier service point and from the customers home.Companies are also able to handle their returned goods through CEP (Marchet et al. 2018). CEP is often a prevalent solution and offers an arrangement of

value-adding, door-to-door transportation, next-day-delivery and time-definite delivery that can take a couple of days (Cheng, Liao, & Hua, 2017). The final classification is store-returns where

the customers will have the option of purchasing goods online and then return the goods to the retailers physical store. By utilizing this option retailers gain the advantage of synergy between an online platform and physical locations which creates an advantage over retailers who only offer goods virtually. Physical retailers thereby save resources by letting the customer handle the returns thus saving shipping costs. A UPS study from 2015 revealed that 61 percent of customers prefer the option of in-store returns in comparison to shipping the product back to the online channel. As customers are just as willing to share bad retail encounters as good ones. Retailers have the opportunity to improve their brand image if customers are handled with respect to their needs and expectations. Is although important that retailers keep in mind the high risk that comes with face - to -face encounters if customer received a bad experience (Ertekein, 2018).

However, it is important that retailers consider the tradeoffs between customer convenience and the added costs of inventory complications. By offering in-store returns retailers can gain customer relationship and build loyalty as well as increase in-store traffic and sales. Moreover, there also needs to be thought put into the tradeoff when prioritizing customer perception and offering wider flexibility, minimized inconvenience and expenses, that ensure the customer is directly credited for the return. In contrast to the costs associated with implementing such an option ( Mahar, & Wright, 2017).

2.6 Specialization

Although there is much importance put onto the appropriate logistics strategies, the next challenge is deciding on whether the responsibility of the logistics operations should lie within the firm or partially/fully be outsourced. It is generally a decision between contract fulfilment where a firm is dependent on a third party (outsourcing) or establishing and creating its own logistics system (insourcing). There is also the option of choosing a hybrid of the two where the firm will combine their own logistics organization with help of logistics service providers (LSP) (Rai, Verlinde, Macharis, Schoutteet & Vanhaverbeke, 2019). LSP’s are a part of operations however, they also allow e-commerce retailers to enhance networks and relations to be able to fulfil their customer orders in a more effective matter (Rabinovich & Knemeyer, 2006). Since OC has become a driver for delivering product to stores and to customer home, LSP’s have become an important tie between the retailer and customer (Rai, Verlinde & Macharis, 2018), especially if home deliveries are located in remote areas away from the retailers main area. But also when markets are considered to be outside the scope of key importance (Rai et al,. 2019). Selviaridis and Spring (2007) categorized the main driving forces for outsourcing as strategic, financial and operational. Where from a strategic point of view a big motivation for outsourcing lies in the ability LSP are able to provide information and expertise that is also in connection with a firms capacity (Rai et al,. 2019). Yu, Wang, Zhong and Huang (2016) reviled that outsourcing has various effects on different firms. The firms that possess low logistics capacity

benefit from outsourcing resulting in positive sales and growth performance. However, firms with high logistics capacities are at risk of encountering negative consequences (Yu et al,. 2016). In more modern outsourcing process more focus is put into systematic and continuous support, but also into reorganizations various department with in a company regardless to field of

operation. Therefore there are executives and other employees who are sceptic or disapproval of such practices. The fear stemming from the potential lack of control and dependency towards the LSP’s. There have been occasions where companies have had to be put down due to over

dependence, not because of poor service but due to employees becoming accustomed to such service and are not able to work otherwise. Further risks with the outsourcing process is that the offered service or product sacrifices quality in able to maximize profit. Therefore it is important companies looking to outsource align their values with the vendor so such implications are avoided (Vaxevanou, & Konstantopoulos, 2015).

There is importance in over weighing the consequences connected to outsourcing. If the logistics service is a core competency it raises substantial risk. To reduce risk and maintain control firms most often will keep such practices in house (Bowersox, Closs, Cooper, & Bowersox, 2013).

Looking from the financial perspective the use of outsourcing has the ability to reduce a firm's costs for asset investments, equipment maintenance and labour (Selviaridis and Spring, 2007), but also making it possible to designate further resources to their core business. Volume

therefore shows importance in this aspect, as firms grow and reach a scale where they no longer are able to manage, outsourcing should be considered. However as business keeps on growing firms can take their operations back to obtain economies of scale (Rai et al,. 2019). Although large product volumes create better terms for negotiation in regards to outsourcing contracts (Bowersox et al,. 2013).

As the final driving force is concerned with the operation and focuses a lot on the relations that firms have to LSP’s. The impact LSP’s have on logistics operations while judging inventory levels, order cycle times, information technology, asset use and quality of service (Rai et al,. 2019) is not something this study will be able to touch upon and is therefore not discussed.

2.7 Visibility

Another important factor to consider for OC retailers is to which extent their assortment should be offered in each channel as well as the level of transparency they should provide to their customers. In this study, these factors has been chosen to be referred to visibility. Previous contributions, e.g. Melacini, Perotti, Rasini and Tappia (2018), mentions that assortment

planning is a key issue for retailers who want to operate in the OC environment. The size of the physical store often limit retailers ability to have a wide assortment, while the assortment offered for online sales can be offered in a much broader extent. It is therefore common that OC retailers carry the most popular merchandises the physical store, whereas the online channel is used to sell products purchased less often as well as highly specialised products that are not profitable enough to have in the physical stores (Melacini et al., 2018). From an inventory cost perspective, Bhatnagar & Syam (2014) state that merchandise with high inventory carrying cost is more beneficial to have in warehouse located in a subarea and exclusively offered online. Furthermore, according to Li, Lu and Talebian (2015) products that can be delivered quickly at comparatively low cost is preferred to be sold at the online channel, while products that have higher delivery cost is preferred to be sold in the physical store. However, as one can realise that this is a highly discussed topic in literature, the authors have chosen to add “assortment” as a logistic variable to identify how Swedish OC retailers manage this area, where the options are “complete assortment in all channels” and “complete assortment in web-store”.

Another key area regarding visibility is inventory availability status. In an OC environment, where customers should be able to move seamlessly between the different channels, being able to view inventory availability becomes a fundamental obligation. This requires, however, retailers to implement robust information technology systems where they can integrate their inventories to make all of their physical and information flows consistent (Melacini et al., 2018). While integration is used to coordinate the members decisions and operations within the supply chain, visibility is connected to the customers expectation of the service provided by the OC retailers. However, integration and visibility together can guarantee a single view of

merchandises in terms of location, stock, delivery and dispatch information across the whole supply chains (Saghiri Wilding, Mena, & Bourlakis, 2017). According to Sagiri et al. (2017) integration and visibility make the flow of the products within and between channels possible without any conflicts, improve resource utilization, and thereby improve the customer experience of an OC system. To investigate the level of transparency that Swedish OC retailers provide to their customers in regards to the inventory, the authors have chosen to add “inventory

availability status” as a final logistic variable, where the options are “inventory status in all channels” and “inventory status only in web-stores”.

3. Method and Implementation

This chapter will focus on the methodology of the study, including the research design, the methodological instruments applied, the research process and data collection.

3.1 Research Design

3.1.1 Connection of research questions and the method used

The studies main focus is to map out the logistical practises adopted by Swedish OC retailers. Therefore the study has conducted a literature review to identify the gaps within the field of Swedish OC retail and to further develop the framework presented by Marchet et al. (2018), which is an extension of Hübner et al. (2016) findings. The framework portrays numerous strategic areas regarding logistical practices dominantly utilized by retailers working within an OC environment. To succeed with the aim of this study, a quantitative approach is undertaken. A quantitative approach according to Bell & Waters (2014) address research with the aim to collect facts and studies the relationship of a set of facts to another. This is most often done by

collecting numerical data often with structured and predetermined research questions, conceptual framework and design. Therefore techniques are used that are prone to produce quantified and, if possible generalizable conclusions (Bell & Waters, 2014). This research design makes it

applicable when conducting a study in pursuit of identifying and map out the currently most adopted logistics practices among a large amount of Swedish retailers, as well as if there are any differences between larger OC retailers and SMEs. Especially since the findings need to be able to represent the Swedish retail industry the findings have to be generalizable for the population in question. Therefore the qualitative approach is not of interest as it according to Flick (2007) consists of set interpretative material practices depicting the world thru notes, interviews and conversations etc. Making it applicable when studying something in a natural setting trying to make sense of a phenomenon or interpret it (Flick, 2007). As the study will make broad

generalizations by analyzing data collected with an questionnaire, it will be inductive in nature (Hays, Heit & Swendsen, 2010)

1. What are the most common logistics practices currently adopted by Swedish OC retailers?

2. RQ 2. How do large OC retailers and SME’s differ in regards to their implementation of business logistics models?

As the research questions strive to obtain descriptive information, they tackle questions

formulated in a what format. The quantitative research method has been deemed appropriate, as the objective is not to answer the question why certain practices have been adopted, but is instead interested to identify and map out the most popular ones among Swedish OC retailers (Heidenberger & Stummer., 1999).

3.1.2 Choice of methodological instruments

The study selected the method to conduct a survey by sending out a questionnaire to 134

Swedish companies. A qualitative survey is interested in investigating a population but does not aim to do so by analysing a frequency. It rather means to determine the diversity within a set topic of a predetermined population. Therefore it determines the important variation within a population which is what this study aims to do (Jansen, 2010).

The methodological instrument was chosen due to the fact that a questionnaire is able to collect a vast amount of data in a short period of time. As a questionnaire makes it possible to collect data from the respondents as well as it acts as a tool providing a standard mean for writing and collecting answers but also support the processing of data (Sreejesh, Mohapatra & Anusree, 2014).

3.2 Data collection & Analysis

The study's data collection consists of primary and secondary data. The primary data of the study consists of information obtained through literature review and data collected through a

questionnaire that was sent out to 134 Swedish retailers. The literature review was limited to books, journals and PhD theses based on their relevance and year of publication. A great amount of publications have been rejected in the selection process based on the reading of titles,

abstracts and keywords. The keywords used in the search process has been limited to

“Omnichannel”, “SME’s”, “Retail” and “logistics”. The databases that have been used in the search process are Scopus, Primo (Jönköping Library) and google scholar. The questions in the questionnaire were based on the recent article written by Marchet et al (2018), which provides a classification framework for business logistics models in OC retail. This framework includes different strategic areas and options for a set of logistics variables that OC firms decide upon. As this study is built upon a group project done by the classes of industrial organization and

economy at Jönköping university in 2019 and 2020, the authors have not collected all the data by themselves. This data is therefore classified as secondary data. However, the authors were part of the class of 2019 where they sent out the questionnaire to several companies where seven

responded. This portion of the data is therefore viewed as primary data. The class of 2019 mainly focused on larger OC retailers where the authors analyzed data from 70 retailers, while the class of 2020 mostly targeted SME’s were the authors analyzed data from 64 retailers. In line with literature research it was realized that the framework missed two important strategic areas, namely “specialization” and “visibility” as well as the logistic variable “e-commerce delivery pricing”. These three aspects were therefore added after the data was collected in year 2019, where the information has been complemented by the authors themselves, and is therefore classified as primary data. The answers of the questions were either collected by email, phone calls or through the retailers websites. Furthermore, to include ethical considerations, the class of 2019 and 2020 had the respondents agree that the material will be used in a research project.

Descriptive statistics in form of percentages have been used to analyze the quantitative data. According to Kaushik & Mathur, (2014), descriptive statistics is a straightforward process that can easily collect and summarize large amount of data and information in a manageable and organized manner, which can then be easily translated into results in a distribution of frequency, percents and overall averages. As the aim of this study is to map out the most popular logistical practises among Swedish OC retailers, as well as analyze differences among large OC retailers and SME’s, this approach has been deemed suitable, since it allows the authors to draw

conclusions based on numerically summarized data. The most popular logistic practises have been presented in tables that displays the percentages for each option in chapter four. Thereby reflecting and analyzing the quantitative data with the help of the theoretical framework that is based on the literature review in chapter two.

Figure 3.2.1: The study's research process.

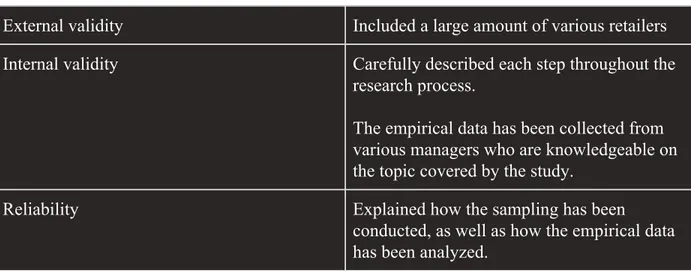

3.3 Validity and Reliability

Validity can be divided into two different categories, namely internal validity and external validity. The prior means that the study measures what it intends to measure, while the latter means the extent to which the study can be generalized to the world at large (Bell & Waters., 2014). To increase the internal validity of this study, all steps throughout the research process are carefully described in chapter two and three, which makes it clear for the reader that the study achieve its aim. Furthermore, to increase the external validity, the authors have included a great amount of various retailers irrespective of their size, thus, it is possible to generalise the results from this study to the Swedish OC market.

Reliability means that the study should be able to provide the same repeated results under the same conditions (Bell & Waters., 2014). To provide high reliability, the authors have clearly

described how the sampling has been done and how the data has been analyzed, making it possible for other researchers to conduct the same study, under similar conditions.

External validity Included a large amount of various retailers Internal validity Carefully described each step throughout the

research process.

The empirical data has been collected from various managers who are knowledgeable on the topic covered by the study.

Reliability Explained how the sampling has been conducted, as well as how the empirical data has been analyzed.

Figure 3.3.1: Actions that has been done to increase the study's external and internal validity, as well as reliability.

4. Results

This chapter presents the findings from the questionnaire sent out to a large number of various Swedish OC retailers. The results are presented as following; structured into tables representing the logistical variables for each strategic area (delivery service, distribution setting, fulfillment strategy, returns management, and visibility) and their corresponding options. The chapter is structured after the study research questions to clearly visualize the correlating answers.

4.1 What are the most common logistics practices currently adopted by

Swedish OC firms?

This subsection contains the results collected from the questionnaire answering the first research question.

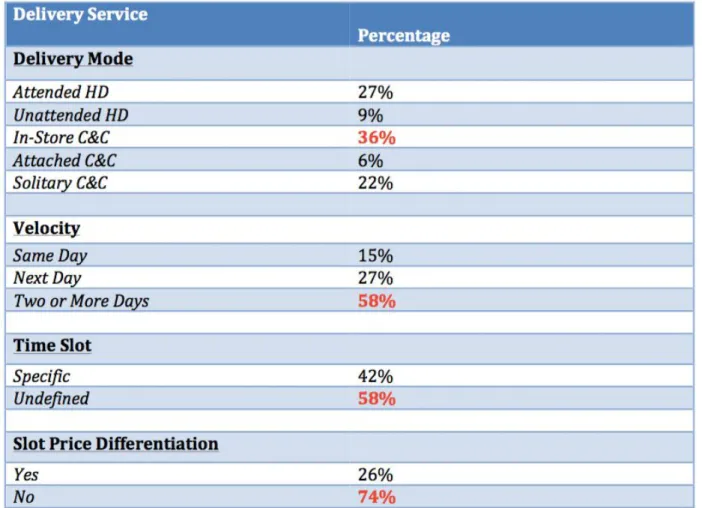

Tabel 4.1.1: A summary of the total collected answers received on the strategic area “Delivery Service” from Swedish OC retailers.

The results from the respondents regarding the strategic area “Delivery Service” shows that Swedish OC retailers most utilize in-store C&C whom received 36 percent, attended HD whom received 27 percent and solitary HD whom received 22 percent as their preferred delivery mode. In regards to velocity the option “two or more days” received the highest percentage of 58 percent. When it comes to “time slot” and “slot price differentiation”, undefined time slot received 58 percent closely followed by specific time slot with 42 percent. Where the option “no” in regards to slot price differentiation received a staggering 74 percent.

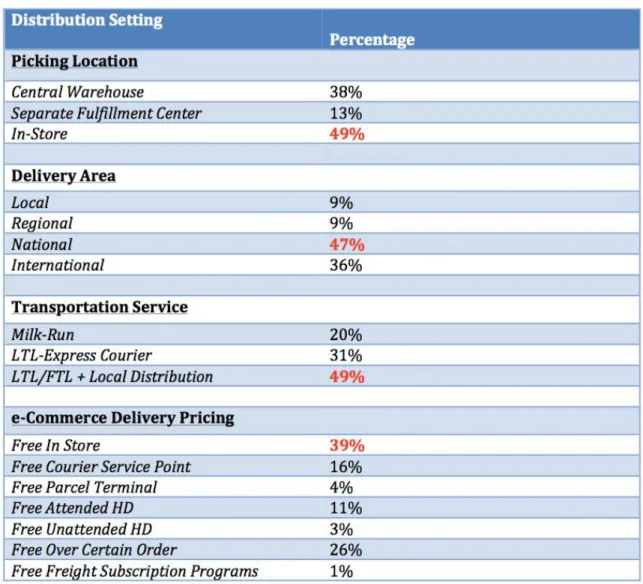

Tabel 4.1.2: A summary of the total collected answers received on the strategic area “Distribution Setting” from Swedish OC retailers.

Table 4.1.2

The strategic area “Distribution setting” illustrates the logistics variable options mostly used by Swedish OC retailers. The logistics variable “Picking location” shows that in-store picking is widely exploited closely followed by central warehouse picking with 38 percent. when it comes to “delivery area” national delivery received 47 percent, however international delivery was not far behind with 36 percent. The most common transportation service option chosen by Swedish OC retailers is LTL/FTL + local distribution who got 49 percent. The e-commerce delivery

pricing shows that free in store delivery pricing obtained 39 percent from the total respondents where the second highest options acquired 26 percent.

Tabel 4.1.3: A summary of the total collected answers received on the strategic area “Fulfillment Strategy” from Swedish OC retailers.

Table 4.1.3

The main strategic area “ fulfillment strategy” clarifies that the logistics variable “automation” received the highest percentage on manual automation with 58 percent and the second highest semi-automated collected 36 percent. In regards to “integration” semi-integrated obtained 41 percent while fully integrated received 36 percent of the total collected answers. “Order

allocation” has its highest percentage on dynamic whom received 57 percent closely followed by static whom collected 43 percent.

Tabel 4.1.4: A summary of the total collected answers received on the strategic area “Returns Management” from Swedish OC retailers.

Table 4.1.4 shows that the most dominant returns mode used by Swedish OC retailers is

“in-store returns” which received 50% of the total respondents. Where as, CEP returns received a close percentage of 47 percent. Regarding free e-commerce returns, table 4.1.4 illustrates that retailers most often offers free returns to their store.

Tabel 4.1.5: A summary of the total collected answers received on the strategic area “Visibility” from Swedish OC retailers.

Table 4.1.5

The results in Table 4.1.5 shows that it is common that Swedish OC firms offers complete assortment only i webstore whom received 55 percent, although it is also common for Swedish OC retailers to offer their complete assortment in all channels as it received 45 percent. When looking at “inventory availability status” retailers most often will offer inventory status in all channels whom received 59 percent, although inventory status only in webstores is not far behind with 41 percent.

Tabel 4.1.6: A summary of the total collected answers received on the strategic area “Specialization” from Swedish OC retailers.

Table 4.1.6

Table 4.1.6 illustrates that 51 percent of Swedish OC retailers outsource from their warehouse directly to the consumer, 33 percent outsource from the warehouse to their store(s), while 5 percent use e-Commerce warehouse operations, 2 percent use warehouse replenishing stores

operations, and 9 percent have e-Commerce returns handling.

4.2 RQ 2. How do larger OC retailers and SME’s differs in regards to their

implementation of business logistic models?

The research paper does not cover the differences between SME’s and larger OC retailers in regards to specialization due to the fact that data was only collected on SME’s, as it was

collected prior to the covid-19 outbreak. The larger OC firms were therefore not able to answer on the logistics variable concerning outsourcing as they were occupied with other business. The result between large OC retailers and SME’s is deemed to be similar when the result is within the range of 5 percent.

Table 4.2.1: Illustrates the differences in percentage between large OC retailers and SME’s from the collected answers regarding the strategic area “Delivery Service”.

Table 4.2.1

Table 4.2.1 illustrates no significant differences between large OC retailers and SME’s regarding their delivery service. Looking at the delivery mode, in-store C&C is the most dominant mode for both large OC retailers and SME’s where this option received 35 percentages of the larger OC retailers respondents and 36 percentage of the collected answers from SME’s. Attended HD is the second most used delivery mode, which got 27 percentages of the larger OC retailers answers and 28 percentages of the answers from SME’s. In regards to velocity, the majority of

Swedish OC retailers deliver a customer order within two or more day. This option received 58 percentages of the collected answers from the larger OC firms, and 57 percentages from SME’s. Furthermore, 58 percentages of the larger OC retailers and 59 percentages of SME’s prefer to have open time deliveries. The greatest part of Swedish OC retailers have not adopted slot price differentiation, as 73 percentages of larger OC firms answered “no” on this question as well as 75 percentages of the SME’s

Table 4.2.2: Illustrates the differences in percentage between large OC retailers and SME’s from the collected answers regarding the strategic area “Distribution Setting”.

Table 4.2.2

Table 4.2.2 illustrates differences between large OC retailers and SME’s when looking at the first logistic variable “picking location”. The most used picking location for large OC retailers is “central warehouse” which received 43 percentages of the collected answers, while the most used picking location for SME’s is “in-store”, which received 61 percentages of the collected answers. Continue with the second logistic variable “delivery area”, the option “national” got the