Craft production in the Kingdom

of Crystal (Glasriket) and its

visual representation

Constructing authenticity in

cultural/marketing production

Songming FengJönköping University

Jönköping International Business School JIBS Dissertation Series No. 140 • 2020

Craft production in the Kingdom

of Crystal (Glasriket) and its

visual representation

Constructing authenticity in

cultural/marketing production

Songming FengJönköping University

Jönköping International Business School JIBS Dissertation Series No. 140 • 2020

Craft production in the Kingdom of Crystal (Glasriket) and its visual representation: Constructing authenticity in cultural/marketing production JIBS Dissertation Series No. 140

© 2020 Songming Feng and Jönköping International Business School Published by

Jönköping International Business School, Jönköping University P.O. Box 1026

SE-551 11 Jönköping Tel. +46 36 10 10 00 www.ju.se

Printed by Stema Specialtryck AB 2020 ISSN 1403-0470 ISBN 978-91-7914-003-8 Trycksak 3041 0234 SVANENMÄRKET Trycksak 3041 0234 SVANENMÄRKET

Abstract

Authenticity is a core concept and phenomenon in contemporary marketing, as both marketers and consumers seek the authentic. Individuals, companies, and industries all work to establish and accomplish authenticity for themselves and related stakeholders. As a marketing point for creating differentiation and singularity, authenticity has the potential to augment the value of a product above and beyond its promising functional, esthetic, or experiential significance. However, authenticity is a concept with heavily debated characteristics, and it is not well understood in its market manifestations. Academic work on authenticity remains vague in terms of both its definition and its marketing relevance. There has been limited empirical understanding of and theorizing about what is meant by authenticity and how it is manifested in production and consumption in the marketplace. In practice, the nature and use of authenticity in the field of marketing is still full of ambiguity and confusion. For marketers, brand authenticity is easy to recognize but hard to manufacture. How producers and marketers manage the development, positioning, and communication of authentic offerings and how they engineer, fabricate, or construct authenticity remain unanswered questions.

This dissertation answers the call of Jones, Anand, and Alvarez (2005, p. 894) to determine which strategies are used for creating and defining authenticity and how these strategies shape our understanding of what is authentic and the call of Beverland (2005a) to find out how brands and marketers create and develop images of authenticity. The purpose of this dissertation is to investigate how authenticity of market offerings is constructed in two cultural/marketing production sites—the craft production of glass objects and commercial photographers’ image production as visual representation of the former—to understand the mechanisms behind the authentication of market offerings and the paradoxes within the construction work. This purpose was fulfilled by pairing the two theoretical domains of cultural/marketing production and authenticity for the investigation of an empirical site—the Kingdom of Crystal (“Glasriket” in Swedish)—located in southern Sweden. As a traditional craft-producing industrial region and a tourist destination, the site has been dedicated to making consumer glass products, maintaining its production mode and ethos as a handmade craft, for more than one hundred years. Being producer focused, the craft sector and craft production offer a strong empirical instantiation of authenticity and can serve as a fertile field to explore and problematize the issue of authenticity at the intersection with cultural/marketing production. The research was conducted over a three-year period with an interpretive and ethnographic approach tapping into multiple sources of data.

This dissertation finds that the glass producers in Glasriket substantively construct five categories of authenticity (technique, material, geographical, temporal, and original) of market offerings via craft production and that commercial photographers communicate and authenticate the craft production world via their image-making practices, which are dimensionalized into a typology consisting of five categories of

practice: reproducing, documenting, participating, estheticizing, and indexing. Illuminating the two-step micro process of cultural/marketing production—the concurrent practices of the product makers and the promoters, this dissertation theorizes about how authenticity operates vis-à-vis two types of production (substantive product making and communicative image making), yielding a number of contributions to authenticity scholarship and the literature on cultural/marketing production. It provides managerial implications for marketers/producers in Glasriket regarding how they can leverage cultural resources to conduct retro marketing as well as suggestions for marketers beyond this context about visual marketing and authenticity-based marketing.

Keywords: Glasriket, the Kingdom of Crystal, glass, craft, authenticity, cultural production, photography, image, semiotics, practice theory, materiality.

Table of Contents

1 Introduction ... 15

1.1 Craft: A subject with contemporary cultural relevance and an empirical instance of authenticity ... 16

1.2 The craft-producing region Glasriket as the research context... 18

1.3 Authenticity ... 19

1.3.1Using “authenticity” as a theoretical lens and heuristic device ... 19

1.3.2Contributing to authenticity scholarship ... 19

1.3.3Contributing to marketing practices ... 20

1.4 Cultural/marketing production ... 21

1.4.1Why focus on the production side? ... 22

1.4.2Paradoxes in the construction of authenticity ... 23

1.5 Purpose of the study and research questions ... 24

1.5.1Purpose of the study ... 24

1.5.2Research questions ... 24

1.5.3The loci of authenticity in this research context ... 26

1.6 Positioning of this dissertation ... 27

1.7 Key terms, terminologies, and glossary ... 29

1.7.1Key terms ... 29

1.7.2Terminologies in semiotics applied in the analysis of visual data ... 30

1.7.3Glossary related to the research context ... 31

1.8 Outline of the dissertation ... 31

2 The context: The Kingdom of Crystal (“Glasriket”) ... 33

2.1 Seeing this research context theoretically ... 33

2.2 Background information on this region... 34

2.2.1General profile ... 34

2.2.2Community and regionality ... 37

2.2.3Glass as a material and objects ... 38

2.2.4Glass products in consumption ... 38

2.3 Authenticity anchors ... 41

2.3.1The craft mode of manufacturing: A key authenticity attribute ... 41

2.3.2Craft-manufacturing-induced tourism: Authentic experience ... 42

2.4 Cultural/marketing production ... 43

2.4.1Marketing communications of three types of organizations ... 43

2.4.2Photographer John Selbing: Exemplary creative worker and marketer ... 44

2.4.3Photographic images as marketing texts and cultural products ... 46

2.4.4The art dimension in the region ... 47

3 Theoretical Inspirations ... 49

3.1 Cultural/marketing production ... 49

3.1.1How does this study treat the two types of production? ... 49

3.1.2Cultural production ... 51

3.1.3Cultural production at the intersection with marketing ... 54

3.1.4Marketing literature examining “production” ... 55

3.1.5Research on photographers’ work within the field of sociology ... 63

3.1.6A practice theory-based approach to studying photographers’ image making ... 66

3.1.7Summary ... 71

3.2 Authenticity ... 72

3.2.1What is authenticity? ... 72

3.2.2Site of production ... 79

3.2.3Site of mediation: Advertising and marketing communications ... 80

3.2.4Summary ... 82

3.3 Craft or craftsmanship ... 83

3.3.1Definitions ... 83

3.3.2Craft as production ... 84

3.3.3Craft as products ... 85

3.3.4Craft as a tourist experience... 86

3.3.5Craft as consumption ... 87

3.3.6Summary ... 88

3.4 Relationships among the three theoretical domains and a conceptual framework ... 88

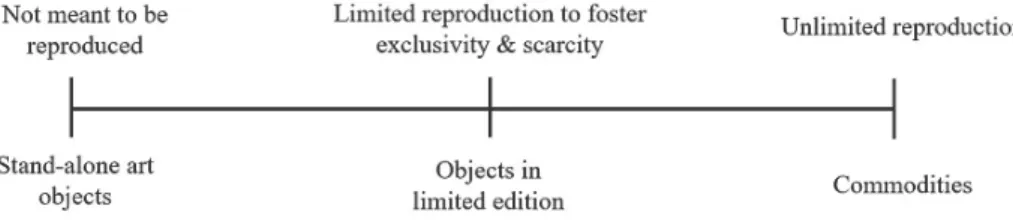

3.4.1Authenticity vs. cultural/marketing production: Dialectic between authenticity and reproduction ... 88

3.4.2Craft vs. authenticity: Overlapping conceptual dimensions ... 89

3.4.3Craft vs. cultural/marketing production: Domain shift ... 90

3.4.4A conceptual framework ... 90

4 Methodology ... 93

4.1 Research philosophy and approach ... 93

4.2 Data collection ... 95

4.2.1Photographic images ... 95

4.2.2Interviews ... 96

4.3 Data analysis ... 100

4.3.1Analysis of the craft production of glass (RQ1) ... 100

4.3.2Analysis of photographers’ image production practices (RQ2) ... 102

4.3.3Analysis of the relationship between the two types of production (RQ3) ... 103

4.4 Reflections on research quality ... 104

4.5 Consideration of ethics and copyright ... 106

5 Findings ... 109

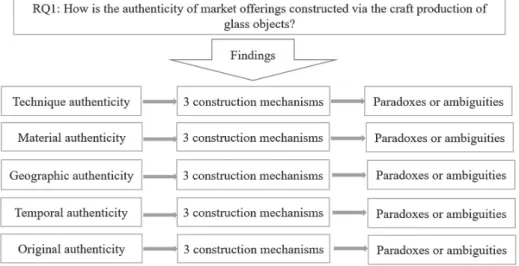

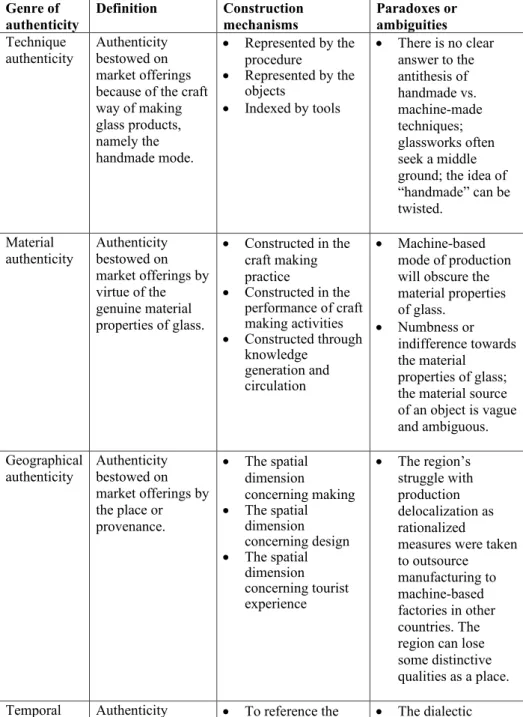

5.1 Substantive construction of the authenticity of market offerings via craft production of glass objects ... 109

5.1.1Construction of technique authenticity... 110

5.1.2Construction of material authenticity ... 119

5.1.3Construction of geographic authenticity ... 128

5.1.4Construction of temporal authenticity ... 137

5.1.5Construction of original authenticity ... 144

5.1.6Summary ... 159

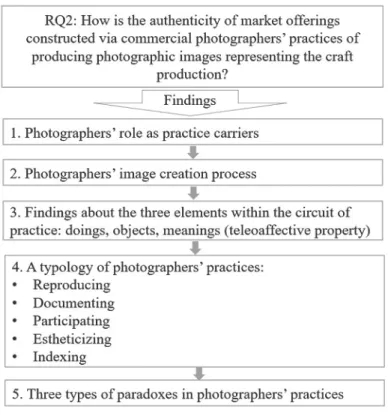

5.2 Communicative construction of the authenticity of market offerings via photographers’ image making practices ... 161

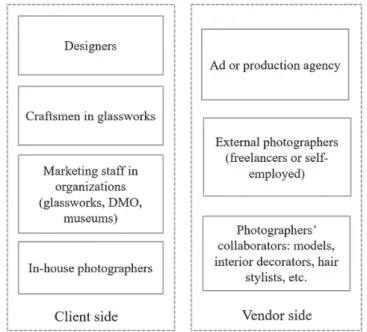

5.2.1Commercial photographers as practice carriers ... 162

5.2.2Commercial photographers’ image creation process ... 165

5.2.3The circuit of practice ... 168

5.2.4A typology of photographers’ image making practices for constructing authenticity ... 172

5.2.5Paradoxes in authenticity construction in photographers’ image-making practices ... 192

5.2.6Summary ... 200

5.3 Relationships between the two types of production ... 204

5.3.1Commonalities ... 204

5.3.2Differences ... 205

5.3.3The relationship between the two types of production ... 206

5.3.4Summary ... 209

6 Discussion ... 211

6.1 Recap of empirical findings addressing the research questions ... 211

6.2 Authenticity rendered in production... 215

6.2.1The attributes or meanings of authenticity ... 215

6.2.2Manifestations and dynamics of paradoxes in authenticity construction ... 219

6.2.3Photographic images: Authenticity in advertising and marketing

communications ... 222

6.2.4Experiential offerings at Glasriket: Authenticity in tourism ... 226

6.2.5Authenticity examined through a visual approach ... 230

6.3 Production that authenticates ... 234

6.3.1Production that renders market offerings authentic ... 234

6.3.2Authentic production? The ironic pairing of the words “authentic” and “reproduction” ... 238

6.3.3Cultural/marketing production examined through a practice-theory lens ... 243

6.3.4The salience of production for consumers and marketers ... 247

7 Conclusion ... 253

7.1 Theoretical contributions ... 253

7.1.1Contributions to the literature on authenticity ... 253

7.1.2Contributions to the literature on cultural/marketing production ... 255

7.1.3An additional note ... 257

7.2 Managerial implications ... 258

7.2.1Cultural resources and retro marketing in Glasriket ... 258

7.2.2Authenticity-based marketing ... 260 7.2.3Visual marketing ... 262 7.3 Limitations ... 264 7.4 Future research ... 266 8 References ... 269 9 Appendices ... 295

9.1 Appendix 1: List and profiles of interview informants ... 296

9.2 Appendix 2: Interview questions ... 298

9.2.1Interview questions for production manager ... 298

9.2.2Interview questions for designers ... 298

9.2.3Interview questions for photographers ... 300

9.2.4Interview questions for marketing managers ... 302

9.3 Appendix 3: Photographic images ... 305

List of figures

Figure 1. Positioning of this dissertation ... 28

Figure 2. A conceptual framework ... 91

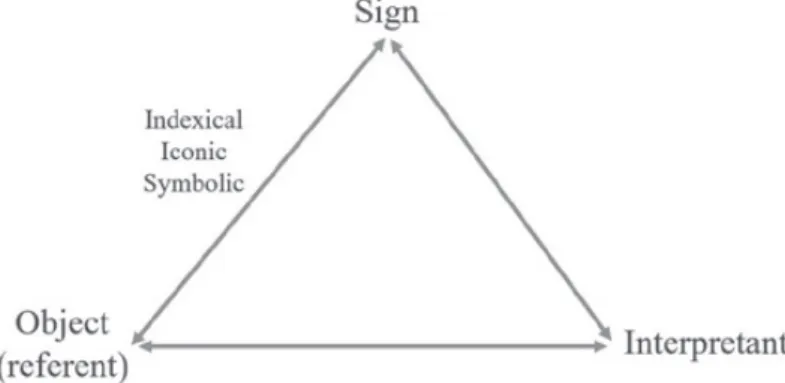

Figure 3. Peirce’s triadic semiosis (Mick, 1986, p. 198) ... 104

Figure 4. Overview of findings addressing RQ1 in Section 5.1... 110

Figure 5. The continuum of the degree of reproduction of objects ... 159

Figure 6. Roadmap of findings addressing RQ2 in Section 5.2 ... 162

Figure 7. Parties involved in photographic image creation ... 166

Figure 8. Commercial photographers’ image creation process ... 167

Figure 9. Photographers’ practices of producing images, framed as “Circuit of Practice” ... 169

Figure 10. Photographers’ practices of producing images, framed as “Circuit of Practice” (doing) ... 170

Figure 11. Photographers’ practices of producing images, framed as “Circuit of Practice” (objects) ... 171

Figure 12. Photographers’ practices of producing images, framed as “Circuit of Practice” (meaning) ... 172

Figure 13. Photographers’ practices of producing images, framed as “Circuit of Practice” (the typology) ... 173

Figure 14. Relationship between the two types of production ... 207

Figure 15. Discussion “Authenticity rendered in production” situated in the conceptual framework ... 215

Figure 16. Discussion “Production that authenticates” situated in the conceptual framework ... 234

List of tables

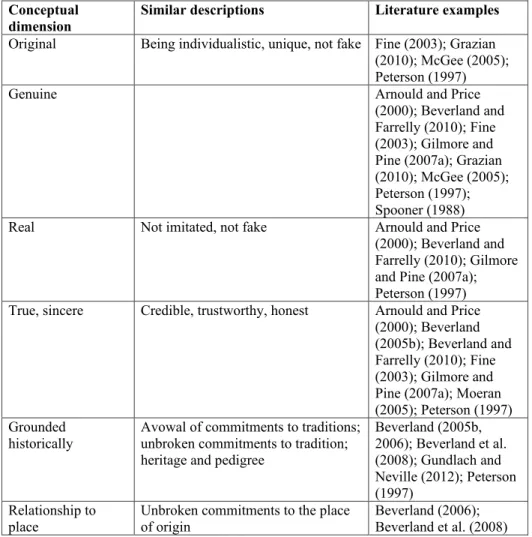

Table 1. Definitions of authenticity ... 73Table 2. The loci of authenticity ... 77

Table 3. Summary of substantive construction of authenticity of market offerings via craft production ... 160

Table 4. Summary of the typology of photographers’ image-making practices to construct authenticity ... 202

Table 5. Matrix indicating how empirical findings relate to the two theoretical domains ... 214

Table 6. Similarities in conceptual dimensions about authenticity between this current study and previous literature ... 217

1 Introduction

The first chapter of this dissertation explains the motivations, logics, boundaries, purpose, and directions for conducting this research project. Section 1.1 introduces the craft concept and related phenomena as having relevance to the contemporary marketplace and as an empirical instance of authenticity. Section 1.2 introduces the research context, the craft region of Glasriket in Sweden. Section 1.3 provides three reasons for the logics of applying the theoretical domain, “authenticity,” in this research. Section 1.4 explains the reason for applying the second theoretical domain, “cultural/marketing production,” in this dissertation. Section 1.5 presents the research purpose, the three research questions, and the issue of the loci of authenticity in this study. Section 1.6 elaborates on the positioning of this dissertation (its placement in a conceptual framework comprised of three theoretical domains). Section 1.7 provides explanations for the key concepts, the terminologies of semiotics, and a glossary related to the research context. Lastly, Section 1.8 outlines the overall structure of this dissertation.

Authenticity is a core concept and phenomenon in contemporary marketing, as both consumers and marketers seek the authentic—the “real,” “genuine,” and “true” (Arnould & Price, 2000; Beverland, 2006; Beverland & Farrelly, 2010; Brown, Kozinets, & Sherry, 2003; Cohen, 1988; Gilmore & Pine, 2007a; Peterson, 2005). However, academic work on authenticity remains vague in terms of both its definition and its marketing relevance. There has been limited empirical understanding of and theorizing about what is meant by authenticity and how it is manifested in production and consumption in the marketplace. This dissertation explores how authenticity is created in cultural/marketing production in the empirical instance of craft production. The craft sector and craft production offer a strong empirical instantiation of authenticity, and the current study aligns craft production with wider long-running debates about “authenticity” within the realm of marketing. In doing so, this study turns to a craft production site for insights into authenticity and cultural/marketing production.

Authenticity has sometimes been conflated with craft. “Authenticity” and “craft” have been marketing points for companies and brands to promote their products, services, and experiences as a means of creating competitive differentiation and uniqueness. Marketers’ presentation of the “artisanal,” the “handmade,” and the “authentic” appeal to consumers. Such terms reflect human ends, purposes, and desires as well as some instrumental characteristics of marketing. Entangled with shared conceptual elements, “authenticity” and “craft” are recurrent analytical constructs in culturally informed research about marketing phenomena. Nevertheless, conceptual blind spots exist when it comes to our understanding of how authenticity is constituted vis-a-vis craft in the marketplace. It is argued in the current study that authenticity can be a way of thinking about craft and vice versa; craft can be the

empirical instance, evidence, or reification of authenticity; and craft phenomena have a bearing on conceptualizations of and discussions about authenticity.

1.1 Craft: A subject with contemporary cultural relevance

and an empirical instance of authenticity

In our current era heralding artificial intelligence, robotized production and labor, and the digitalization of businesses and consumer life, the term “craft” maintains its currency given its cultural foci and humanity-rooted value orientation. This is evidenced by the popularity of such phenomena as Swiss-made watches, Cuban cigars, artisanal bread and coffee, and craft beer and wine (Chapman, Lellock, & Lippard, 2017; Smith Maguire, 2018), the farm-to-table movement (Zevnik, 2012), the rebirth of vinyl analogue records (Bartmansk & Woodward, 2015), and craft consumption (Campbell, 2005). Today, in the marketplace, artisans and craft offerings are again on the front line, pitted against industrial giants, in the form of small-batch, independent production set-ups such as a private beer brewery, a glass art studio run by a glass artist/blower, or an artisanal guitar luthier’s workshop and retail store. Ironically, even large multinationals are climbing onto the bandwagon. Some large global brands either acquire or create their own “craft” sub-brands or product lines. The US-headquartered natural and organic food supermarket chain Whole Foods has its own seal attributing the label “Authentic Food Artisan”1 to

goods offered by “small, family-run enterprises passionate about handcrafting the finest foods in small batches using traditional methods.” The e-commerce giant Amazon.com launched “Handmade at Amazon” in 2015 for artisans making hand-crafted items to compete with Etsy.com (Weise, 2015), the e-commerce website focused on handmade, vintage items, and craft supplies. Since 2013, Starbucks has rolled out coffee Reserve Roasteries in Seattle, New York,2 Shanghai, Milan, and

Tokyo to offer consumers an artisanal coffee experience. Each of these Starbucks retail places is a working coffee roastery, where master roasters, who have trained for years in the craft of coffee, roast small-batch single-origin coffees in front of customers (“Starbucks opens reserve roastery New York,” 2018).

The term “craft,” a shortened version of the word “craftsmanship,” is usually used interchangeably with other terms like “artisan,” “handmade,” “craftsmanship,” and “handicraft” by producers, marketers, consumers, and researchers. As a signaling term, such labels have often been used by brands as a claim, appearing on advertisements, product packages and labels, and other marketing discourses (Bhaduri & Stanforth, 2017; Fuchs, Schreier, & Osselaer, 2015; Waldron, 1978). Such marketing messages celebrate handcrafted market offerings with a romanticized, nostalgic imagery of the traditional, different, authentic, or genuine, produced with care or produced locally. In a study of craft chocolates in the US,

1 https://www.wholefoodsmarket.com/blog/whole-story/support-local-artisans

2 https://stories.starbucks.com/press/2018/starbucks-opens-23000-square-foot-immersive-coffee-destination-in-new-york/

Leissle (2017, p. 42) observed that the term “artisan” revives advertising’s earliest goal: “to comfort wary consumers by assuring them a real person made the products pouring forth from anonymous factory floors.”

Contemporary Western consumer societies are characterized by cultural homogeneity amidst the apparent diversity of commodity spectacle and consumer choice (Wernick, 1991). Swamped by a flood of mass-produced products that are viewed as being commoditized, banal, and inhuman, some consumers yearn for products that are handmade, artisanal, environmentally and ethically produced, or locally produced using natural materials. Artisanal or handmade products enrich the marketplace with variety and satisfy consumers’ desires for distinct products, authenticity, and provenance (Campbell, 2005; Chapman et al., 2017; Hartmann & Ostberg, 2013; Terrio, 1998; Thurnell-Read, 2019; Waehning, Karampela, & Pesonen, 2018; Yair & Schwarz, 2011). Crafts and artisans help to heal the alienation of people from the provenance of the goods that they consume (Hobsbawm, 1984). Consumers can feel the labor and heart of the maker in the finished object, which is not possible with commodities. Buying handmade products is a way of quietly protesting against mass-produced goods. Consumers’ choices in turn contribute to the actualization of their meaningful ways of life, as craft is a way of seeing the world, a way of being, and a way of thinking. Enriching our society in many ways, craft has triggered new forms of consumption and production. In contrast to the exploitative production terms of machine-based mass production, the craft mode of production offers goods that are materially desirable and ethically sound to consumers. Craft stands in opposition to the disenchanting rationalization aspects put forth by Ritzer (1993).

Craft phenomena (i.e., craft production, craft object, craft experience, and craft consumption) resonate strongly with the notion of authenticity, given that the extant literature and conceptualizations about authenticity have recurrently touched on the dimensional elements that are central to craftsmanship—small scale, independent artisanal producers, handmade production techniques, the use of culture and history as referents, natural ingredients or materials, the concept of terroir, and quality commitments (Beverland, 2005b; Hartmann & Ostberg, 2013; Smith Maguire, 2018; Waehning et al., 2018; Wherry, 2006). Craft items are uniquely imbued with authenticity, and craft phenomena are approached by researchers via the language of authenticity. Wherry (2006, p. 29) considered how craft is related to authenticity: handicrafts are immune to the loss of authenticity and offer one of the more stable product forms for investigating the meanings of authenticity in the age of intensified global–local interactions. Handmade objects have been said to “offer a sense of the ‘authentic’ in an ‘inauthentic’ world” (Luckman, 2015, p. 68). In the world of craft food and drink, the language of authenticity is used to distinguish products made by hand rather than through industrial processes (DeSoucey, 2016; Ocejo, 2017). The increasing number of craft breweries is in alignment with consumers’ heightened need for authenticity (Kadirov, Varey, & Wooliscrof, 2014). For example, in their study of craft beer consumption in Mexico, Gómez-Corona, Escalona-Buendía, García, Chollet, and Valentin (2016) found that the main motivation for consumers to drink craft beer, in comparison with mainstream industrial beer consumption,

seems to be the quest for authenticity in building identity. In his conceptualization of craft consumption, Campbell (2005) connected the craft consumer to his or her search for authenticity by suggesting that craft consumption can be viewed as a means of self-expression and self-authentication in a world dominated by commodification and marketization. Studying craft souvenirs in the context of tourism, Littrell, Anderson, and Brown (1993) concluded that uniqueness, workmanship, esthetics, cultural and historical integrity, genuineness, and the characteristics of the craftsperson are the factors that contribute to the authenticity of a craft souvenir.

The above observations by scholars indicate that craft phenomena are an empirical instance of the abstract concept of authenticity. Given its contemporary relevance to the consumer society and the marketplace, as well as its entanglement with the concept of authenticity, craft production is selected as the context of the current study. This dissertation selects Glasriket, a traditional craft-producing region in Sweden, as the research context and adopts the two theoretical areas of authenticity and cultural/marketing production as tools to investigate the craft phenomena. In doing so, the study turns to a craft production site for insights into authenticity and cultural/marketing production.

1.2 The craft-producing region Glasriket as the research

context

This dissertation unpacks the concept of authenticity in a craft production site—the glass-making region called “Glasriket” (“Glasriket” is the Swedish name; the English name is “the Kingdom of Crystal”). Located in southern Sweden and with a history extending for more than one hundred years, the industrial region of Glasriket has been dedicated to producing consumer glass products, maintaining its production mode and ethos as a handmade craft. The region is world famous for such brands as Orrefors, Kosta Boda, and Målerås, which produce and sell utility and art glass products with a sleek Swedish and Scandinavian esthetic sensibility to global consumer markets. Most of the glassworks3 are unique, small-scale firms, their

craftsmanship being passed from one generation to another. This region has been transitioning into a living tourist destination since the 1980s, attracting tourists from Sweden and abroad every year. Tourists partake in various activities, such as a guided tour of a factory, shopping in factory stores, enjoying a “Hyttsill” banquet in a factory (a dinner event mimicking indigenous traditions), or attending a “blow your own glass” event, among others. Chapter 2 provides detailed accounts of this research context.

Craft phenomena often cluster in a specific geographic place or “provenance,” such as the chateau-made grand cru wines of the Bordeaux region in France (Peterson,

3 Glassworks is a Swedish word, referring to a company that runs the business of manufacturing and selling consumer glass products. It also refers to a factory where glass manufacturing is conducted.

2005), handmade guitars in Spain (Dawe & Dawe, 2001), oriental carpets woven in Turkmen (Spooner, 1988), and handicrafts sold as ethnic and tourist arts in the Hang Dong district in Thailand (Wherry, 2006). Despite their peculiarities, craft regions have a lot in common: small-scale, “authentic” forms of production, low technology, rich heritage, struggles and reinvention in the face of threats from machines and industrialization, and the contestations and paradoxes at play in sustaining the craft mode of production and ethos. As a traditional craft-producing region, the site of Glasriket is symptomatic of other craft sectors or regions, exemplifying similar contestations, changes, and challenges.

Glasriket is an appropriate site to examine the issues of authenticity and cultural/marketing production given its craftsmanship in making objects, rich cultural heritage, and comprehensive market offerings—products, brands, visual images, tourist experiences, design artists, marketing communications, and so on. All these properties of this context hold important insights for this research. Though the term authenticity is seldom explicitly claimed or verbalized by actors in this region, issues of authenticity are apparently evidenced by observations framed in the following questions. Why do the glassworks and the destination marketing organization (DMO) love to use the words “craftsmanship” and “handmade” in their marketing collateral? Why do these glassworks offer a “factory tour” as a tourism experience to visitors, during which they can see real craftsmen blowing glass in a real factory? Why do some of the photographic images in the marketing materials demonstrate the “handmade” procedure in making glass? Do these efforts aim to showcase or highlight the “true” or “real” aspects of the glass products, their making, or the brands that they bear? The observations mentioned in these questions indicate certain ways in which producers and marketers construct authenticity.

1.3 Authenticity

1.3.1 Using “authenticity” as a theoretical lens and heuristic device

This dissertation uses “authenticity” as a theoretical lens and heuristic device that provides a language and a methodology able to understand craft phenomena. Little research has been conducted about craft phenomena using an authenticity-inspired theoreticallens (examples include Hartmann & Ostberg, 2013; Kettley, 2016; Smith Maguire, 2018; Thurnell-Read, 2019). The concept of authenticity can help with the understanding of craft phenomena. Craft and craft production can be a natural mediator that can aptly channel meanings of authenticity. With its theoretical significance in the marketing literature, the theoretical concept of “authenticity” can function as a currency to link the current study (concerning the Glasriket context and its craft production) to broader conversations in the realm of marketing.

1.3.2 Contributing to authenticity scholarship

Authenticity has broad theoretical significance in the marketing literature.Brown et al. (2003, p. 21) argued that the search for authenticity is “one of the cornerstones of

contemporary marketing.” Individuals, companies, and industries all work to establish and accomplish authenticity for themselves and related stakeholders. According to the literature about the consumption aspect, consumers actively seek authentic products, brands, places, experiences, and persons as well as the fulfillment of a genuine self (Arnould & Price, 2000; Beverland & Farrelly, 2010; Gannon & Prothero, 2016; Goulding, 2000; Grayson & Martinec, 2004; Rose & Wood, 2005; Visconti, 2010). Postmodern consumers crave the authentic in a world that is becoming increasingly contrived and commercialized. Consumers’ desire for authenticity emerges from “malaises of modernity” whereby disenchantment, individualism, and instrumental rationality lead to the “narrowing and flattening of our lives” (Taylor, 1991, p. 6). Authenticity can be resorted to as an ameliorative remedy to the alienating influences of modernity (MacCannell, 1976). Critiques of mass culture and consumer society in the latter part of the twentieth century (Baudrillard, 1998; Benjamin, 1969; Horkheimer & Adorno, 2002) discussed the proliferation of inauthenticity in the modern world, which bestows authenticity with its meaning and value. In a postmodern market environment characterized by hyperreality (Firat & Venkatesh, 1995), globalization (Askegaard, 2006), and deterritorialization (Arnould & Price, 2000) as well as standardization and homogenization (Thompson, Rindfleisch, & Arsel, 2006), people are dissatisfied with modern work, consumption, and social life. According to the literature about the production aspect, authenticity can help to position a firm or brand as being different from industrial mass production (Beverland, 2009; Beverland, Lindgreen, & Vink, 2008; Beverland & Luxton, 2005; Guthey & Jackson, 2005; Hartmann & Ostberg, 2013; Visconti, 2010). Authenticity can create an aura around a brand or firm (cf. Brown et al., 2003) that differentiates it from its mass market counterparts. Producers and marketers respond to consumers’ quest for authenticity by supplying authentic market offerings, treating authenticity as the new business imperative (Beverland, 2005a, 2005b, 2006; Beverland & Luxton, 2005; Gilmore & Pine, 2007a; Hartmann & Ostberg, 2013; Visconti, 2010). The best brands have street cred—a kind of soul rooted in something real and authentic.

Authenticity is a cultural concept (Grayson & Martinec, 2004) and a valued quality in modern culture. As noted by Peñaloza (2000), authenticity is a quality of which the characteristics are heavily debated, and it is not well understood in its market manifestations. This dissertation answers the call of Jones et al. (2005, p. 894) to investigate the strategies that are used for creating and defining authenticity and the way in which these strategies shape our understanding of what authentic is. Such an endeavor will make timely theoretical contributions to authenticity scholarship.

1.3.3 Contributing to marketing practices

Authenticity has managerial significance in the marketing industry. Being a cornerstone of contemporary marketing practices (Brown et al., 2003), authenticity has instrumental value for producers and marketers. It has the potential to augment the value of a product above and beyond its promising functional, esthetic, or experiential significance. Authenticity has been a marketing point as a form of

differentiation and a point of uniqueness. It is often used as a marketing narrative or product label by firms that draw on it to reinforce their status, command price premiums, and ward off the competition (Beverland, 2005b). However, the nature and use of authenticity in the field of marketing are still full of ambiguity and confusion. There are different situations: companies in traditional craft sectors promote their products as genuine and authentic offerings, and companies in mass production claim “authenticity” through the wording, packaging, and labels that serve as a value proposition in the marketing rhetoric. As pointed out by Busdieker (2017), for marketers, brand authenticity is “easy to recognize, hard to manufacture.” How producers and marketers manage the development, positioning, and communication of authentic offerings and how they engineer, fabricate, or construct authenticity remain unanswered questions. This dissertation addresses the production aspect of authenticity, contributing insights relevant to marketing practices.

1.4 Cultural/marketing production

Authenticity operates at the core of mass cultural production (Frosh, 2001; Peterson, 2005). Cultural industries manufacture authenticity to distinguish their products and services from the competition and to respond to the perceived needs of consumers. The tilt toward the production side in this current study draws on and is inspired by exemplary research on authenticity fabrication performed by producers in the cultural industries and/or marketing realm—photography in marketing (Frosh, 2001; Guthey & Jackson, 2005), country music (Peterson, 1997), an advertising agency (Moeran, 2005), film production (Jones & Smith, 2005), and luxury wine (Beverland, 2005b; Beverland & Luxton, 2005). These studies used different verbs to label production: marketers’ projecting of the authenticity of brands through advertising (Beverland et al., 2008), fabricating authenticity (Belk & Costa, 1998; Peterson, 1997), creation and recreation of the images of authenticity (Beverland, 2005b), or staging authenticity in tourism (Cohen, 1988; MacCannell, 1973). Such studies theorized about how cultural/marketing producers respond to users’ quest for authenticity in the marketplace by constructing authentic cultural products such as texts, images, music, or other objects with meanings. As an example, in his study of the country music industry in the US, Peterson (1997) proposed that, in cultural industries, the success of a given cultural product and its acceptance by its audience often depend on the appearance of authenticity. He elucidated the deliberate strategies used by powerful actors in the industry to legitimize various types of authenticity. By problematizing and researching the producers and their production work, this dissertation joins the conversations of these studies and contributes to the domain of cultural/marketing production. The expression “cultural/marketing production” refers to two types of intermingled production: cultural production and marketing production. Throughout this dissertation, I use the punctuation “/” between “cultural” and “marketing” in the expression “cultural/marketing production” because these two fields (cultural production and marketing production) are intermingled. Section 3.1 in Chapter 3 (“Cultural/marketing production”) provides more elaborations to explain the rationale for such a usage.

1.4.1 Why focus on the production side?

Production, due to its inherent nature, can serve as a fertile field to explore and problematize the issue of authenticity. Authenticity is a social construction, as it is not something that exists inherently in an object, a text, or an experience (Beverland, 2005b; Cohen, 1988; Gilmore & Pine, 2007a; Peterson, 1997, 2005; Reisinger & Steiner, 2006; Wang, 1999). Rather, these objects are made and rendered authentic, to be deemed so by certain beholders (Gilmore & Pine, 2007a). Previous studies have agreed that authenticity is a socially constructed and negotiated interpretation of the essence of what is observed by certain evaluators relative to their particular contexts and goals (Beverland, 2006; Beverland et al., 2008; Grayson & Martinec, 2004; Grazian, 2005; Peñaloza, 2000; Peterson, 2005; Reisinger & Steiner, 2006; Rose & Wood, 2005; Thompson et al., 2006; Wang, 1999; Zukin, 2010). The types of authenticity are inscribed in a socially constructed way, as they obtain their authenticity through processes of performativity or what Peterson (2005, p. 1086) called “authenticity work.” Therefore, authenticity is something that is done in addition to something that is. Authenticity can be examined as something that is “achieved,” “fabricated,” or “produced” (Peterson, 1997; Zukin, 2010). The current study takes a production-focused perspective on the issue of authenticity in relation to craft production.

Large amounts of extant studies in the marketing literature have privileged the consumer, problematizing such issues as identity construction, self-authentication, personal authenticity, re-enchantment, self-cultivation, and so on (Arnould & Price, 2000; Badot & Filser, 2006; Brown et al., 2003; Gannon & Prothero, 2016; Giesler & Luedicke, 2009; Grayson & Martinec, 2004; Hartmann & Ostberg, 2013; Rose & Wood, 2005). However, these studies have implied that such pursuits of consumers are decoupled from the production sources of brands and products. Though it is consumers who will ultimately valuate or experience products to determine their authenticity, the production of these items can shape consumers’ evaluations and experiences. As pointed out by Smith Maguire (2018), consumers’ judgment or evaluation of authenticity is subject not only to individual interpretations but also to strategic mobilization and marketization. Besides a large proportion of authenticity literature examining consumers’ evaluations of authenticity, some researchers have dealt with how evaluations are scripted or channeled through the texts and practices of market actors (Smith Maguire, 2018, p. 64). Producers’ authenticating work provides the fertile ground, creating reliable pathways and cues for consumers to perform the evaluation and mobilize their behaviors. In some situations, contrary to the norm that companies must cater to consumer needs, producers shape the landscape of authenticity. For example, in an empirical examination of Scottish goods sold to tourists at retail outlets and festivals, Chhabra (2005) found that vendors are the definers of authenticity, which is supply driven.

It is not enough to attribute authenticity only to the consumption sphere. It is necessary to add the authenticating acts of marketers or cultural producers to the authenticity equation, as few studies have attempted to elucidate the authenticating processes and mechanics through which authenticity is fabricated or constructed by

marketing/cultural producers. As a delimitation, this dissertation does not address the consumption side (e.g., consumers’ self-authentication practices for achieving the authentic self). The current study focuses on the authenticity construction practices performed by two types of producers in Glasriket—glass makers (i.e., craftsmen and designers) and commercial photographers—as part of the marketing system. Many actors may be involved in authentication, and the consumers (end users) have a strong voice in judging and actualizing the authenticity. However, the current study chose to focus on the work of these two types of producers, who are the pivotal and visible actors in substantively and communicatively fabricating, rendering, and shaping the authenticity of offerings in the marketplace.

1.4.2 Paradoxes in the construction of authenticity

Authenticity is barely as normative or prescriptive as producers wish or present. Researchers have continually investigated the interplay and intermingling of the authentic and the inauthentic in the marketplace (Askegaard, Kristensen, & Ulver, 2016; Boyle, 2003; Hietanen, Murray, Sihvonen, & Tikkanen, 2019; Stern, 1994). The authentic and the inauthentic are often expressed asbinary oppositions: true vs. contrived, real vs. fictional, originality vs. reproducibility, original vs. fake, real vs. imitative, and authentic commodities vs. counterfeit commodities. Authenticity is frequently characterized by dilemmas and paradoxes in its construction and emergence. The construction of authenticity by cultural/marketing producers in the current study inevitably involves a number of paradoxes. As a craft-producing region that is ambiguous and hotly contested in its own right, Glasriket has witnessed the contestations of competing forces. On one hand, glassworks have had to resort to rationalization, commercialization, and commoditization to sustain their businesses and adapt to environmental changes, leading to dis-authenticating effects. On the other hand, they have worked to authenticate their brands, products, and marketing messages via various mechanisms (e.g., singularizing, enchanting, and estheticizing) to authenticate their market offerings. Much of the effort of authentication in the two production practices examined in this dissertation (i.e., craft production and its visual representation) are characterized by situations in which authenticity and inauthenticity co-exist (Benjamin, 1969). The authenticating efforts are juxtaposed with the negative aspects of inauthentic commercial operations (machine-based production techniques, reproduction of objects for mass markets, reproduction of images for marketing, etc.).

Cultural producers and marketers, implicitly and explicitly, work to manage and resolve these paradoxes on a continuous basis. The authentication work carried out by cultural/marketing producers can also be viewed as presenting an opportunity to determine how they resolve these dilemmas and paradoxes. From a research perspective, the paradox premise provides a rich site for the investigation of the complexity and open-endedness of the notion of authenticity in the bigger context of brand meaning management in marketing (Brown et al., 2003). While analyzing the two types of production work involved in constructing authenticity, the current study also explores the complex interplay of dichotomies in paradoxes to chart the “dialectic of authenticity” as it plays out in the empirical instance of craft production.

1.5 Purpose of the study and research questions

1.5.1 Purpose of the study

To review the above, the purpose of this dissertation is to investigate how authenticity is constructed through two cultural/marketing production practices—the craft production of glass objects and commercial photographers’ image production as a visual representation of the former—to understand the mechanisms of the authentication of market offerings and paradoxes within the construction work. Such a purpose will lead to the discovery of the mechanisms of authentication occurring in two production sites, which generate two types of cultural products, respectively glassware and photographic images. These two practices of cultural/marketing production bestow authenticity on market offerings and will inform our understanding of the nature of authenticity and various mechanisms of its formation. The market offerings here refer to the objects, products, brands, places, persons, marketing messages, and so on provided by companies and brands. Broadly speaking, the current study examines the ways in which authenticity plays out in a craft production site and locates the findings within the theoretical debates on authenticity and research about cultural/marketing production.

In this effort, authenticity is treated as something that operates in the arena of craft production, which is constituted by two key types of production: 1) the material, physical craft making of consumer products in the glass industry region of Glasriket; and 2) commercial photographers’ production of photographic images representing the former in the sphere of marketing communications.

1.5.2 Research questions

To achieve the aforementioned purpose, the following research questions were composed:

• RQ1: How is the authenticity of market offerings constructed via the craft production of glass objects?

• RQ2: How is the authenticity of market offerings constructed via commercial photographers’ practices of producing images representing the craft production?

• RQ3: In what way are the two types of production related?

This dissertation examines two specific sites for the construction of authenticity: the craft production of glass objects and commercial photographers’ practices of producing images as a way of representing the former. The construction of authenticity is embedded in and mediated through these two types of production, which form a rich palette for researching the concept of authenticity and its manifestations in the marketplace. These two sites are analogous to the concepts of substantive staging and communicative staging in the study of tourism and

experiential consumption (Arnould, 2006, p. 189). Substantive staging refers to “the physical creation of contrived environments” (ibid., p. 189). As an example, the historical tourist site of Gettysburg in the US is substantively staged through tangible and physical artifacts: its landscape, monuments, museums, and buildings (Chronis & Hampton, 2008). Communicative staging refers to “ways in which the environment is presented and interpreted by commercial service providers or by consumer adepts and experts who become implicit or explicit confederates of marketers” (Arnould, 2006, p. 189). Taking the same example of the Gettysburg tourist site, tourist guides perform communicative staging by narrating stories about objects and events to transmit experiential meanings to visitors (Chronis & Hampton, 2008). In the current study, the two sites of production in Glasriket belong to the substantive and communicative acts, respectively. They are substantive construction and communicative construction of authenticity, respectively. By examining both arenas, this current study considers both the material/tangible and the symbolic dimensions in the authenticity of market offerings.

RQ1 concerns the physical production of glass objects that are manufactured, material products. The production involves various tactics employed by glass makers (craftsmen, designers, etc.) to project authenticity. The investigation of the production of physical objects is salient especially for the politics of craft, because, in our current societies with mass-produced commodities, there remains “human enchantment with the process of making” (Luckman, 2015, p. 70). Karl Marx (2000) raised the concepts of estrangement and alienation—originally, it was through making and possessing things that human beings came to feel their own humanity and efficacy. Marx (1970) pointed out the discomforting prospect that, even though consumers are surrounded by commodities that are produced by others, they are alienated from the production. The human experience of that production of the commodities is often forgotten or concealed. “The sense of joy, anger, or frustration that lies behind the production of commodities, the states of mind of the producers, are all hidden to us as we change one object (money) for another (commodity)” (ibid., p. 163). Production becomes what Marx referred to as a “hidden abode” (ibid., p. 279). An examination of the production of objects by glass producers can address this lack of knowledge in a consumer society by revealing how this type of production renders market offerings authentic. In addition, research on the concrete, physical production of products in the backend can correct the perception that authenticity can be constructed by marketers in a superficial way, such as by dressing up messages or putting claims on product packaging and labels (Lee, Sung, Phau, & Lim, 2019; Neff, 2010).

RQ2 concerns the way in which craft production and its attendant products are visually represented as authentic and the visual aspects of the communication of market offerings’ authenticity. The analysis focuses on how photographers create the authentic representation of different objects via the medium of photography in marketing materials or how the created images render market offerings authentic. This area belongs to marketing communications, peripheral to the actual production of products. As part of the marketing system, photographers project the authenticity

of market offerings onto photographic images, which are symbolic, immaterial artifacts. The photographers work as intermediaries, who frame selected anchors as legitimate points of attachment for others’ evaluations of authenticity and craft (Smith Maguire, 2018).

Why did I investigate the production of photographic images? The extant studies about authenticity and craft have paid scant attention to the visual aspect (for exceptions, see Frosh, 2001; Guthey & Jackson, 2005; A.-S. Lehmann, 2012; U. Lehmann, 2012), but favored the analysis of written text—narratives, discourses, and stories (Hamby, Brinberg, & Daniloski, 2019; Hartmann & Ostberg, 2013; Thurnell-Read, 2019; Visconti, 2010). Though some studies have explored how marketers employ a multitude of visual and verbal design cues to enable their products to be perceived as more authentic in the eyes of the consumer (Beverland, 2009; Gilmore & Pine, 2007a; Lee et al., 2019), little attention has been paid to photographic images, which are an important vehicle in advertising and marketing communications. A focus on the production of photographic images leads to the exploration of the visual dynamics within the construction of authenticity. In an image-saturated world, photographic images are juxtaposed with objects and verbal discourses for consumers as part of the totality of offerings in the marketplace. The images are a core component of the brand messages—true, relevant, and able to help retain a brand’s authentic attributes. Images function as informational cues for consumers to evaluate the authenticity of market offerings. The authenticity of the glassworks’ brands and their market offerings and the destination brand of Glasriket is constructed through such visual images in addition to textual narratives.

Lastly, RQ3 explores the linkage between the two types of production in their authenticity construction work. The production of glass products in the glassworks creates authentic referents (i.e., the objects) in the first place. Then, the photographic image production is a type of reproduction of the referents in its effort to enhance the sales of commodities or promote the place as a tourist destination. The photographic images establish an authentic connection with their referents—the objects to be captured by them. The authenticity rendered by the craft production is mediated by the photographic images. Convergence exists between these two arenas due to the concerted efforts of glass makers and photographers. The second arena exemplifies the authenticity paradox in different ways from the first one.

1.5.3 The loci of authenticity in this research context

In this dissertation, where does authenticity reside? In other words, what are the loci of authenticity? I ask this question because authenticity can reside in or be associated with different entities: products, brands, places, human individuals (e.g., consumers or creative workers), experiences, or marketing texts (e.g., ads). Section 3.2.1 (“Where does it reside? The loci of authenticity”) in Chapter 3 contains more information about this issue based on a literature review. In the current study, the loci of authenticity are the market offerings in Glasriket: the products, brands, discourses, experiences, places, and images created and diffused by marketers and producers, which constitute the entirety of a good’s or service’s context of production. This

region churns out authentic objects: products, tourist experiences, brands, discourses and images in marketing communications, and so on. Cultural producers and marketers continually craft together these sources of authenticity to create rich brand meanings. These objects also constitute the contexts from which consumers develop meanings about authenticity for themselves (Beverland & Farrelly, 2010).

In Glasriket, authenticity is an implicit ideal referred to by actors such as craftsmen, designers, marketers, and community champions. The implicit message is that the craft products are authentic, deserving a premium price, higher than that of mass-produced, machine-made products. Unlike the situation in previous studies that have analyzed actors’ discourses or accounts of authenticity (e.g., Jones & Smith, 2005; Visconti, 2010), marketers and producers in this research context seldom overtly claim that they want to create authentic market offerings, nor do they use such a term or similar terms (real, genuine) in their discourses. It is a situation in which I, as the researcher, use authenticity as a theoretical lens or heuristic device to view their production practices, which demonstrate intentions and efforts to authenticate their offerings. Such intentions and efforts are often subtle and implicit. The glassworks in Glasriket and their offerings come off as authentic rather than claiming to be authentic. As noted by Peterson (2005), the constructedness of authenticity is not always overtly claimed by the actor who seeks to be identified as authentic. Blunt claims of authenticity by producers or marketers may do a disservice to their goal, as consumers may resist such messages as commercial propaganda that is inauthentic (Gilmore & Pine, 2007a). A company’s offerings can be perceived as authentic by its customers even though it does not claim them to be so. It may be easier for a brand to be authentic if it does not produce rhetoric about it.

1.6 Positioning of this dissertation

This dissertation is positioned within a theoretical framework pairing the two domains of authenticity and cultural/marketing production (see the two boxes at the top of Figure 1). As mentioned earlier in Section 1.3 in this chapter, the theoretical domain of authenticity serves three purposes: 1) to be used as a theoretical lens or heuristic device to understand craft phenomena; 2) to be leveraged and to be the domain to receive theoretical contributions generated by the current study; and 3) to be researched to yield contributions to marketing practices. As for the domain of cultural/marketing production, this dissertation draws on it and at the same time makes theoretical contributions to it with insights about the work of producers and marketers in carrying out cultural and marketing production as ways of authenticating market offerings (the research purpose, see the text within the circle connecting the three boxes in Figure 1).

This dissertation focuses on the craft region of Glasriket as the research context, and craft production is an apt site to examine the existence of authenticity and its paradoxes. The empirical context of craft production is compatible with the conceptualization of authenticity given the overlapping conceptual dimensions between these two (see the literature review in Section 3.4 in Chapter 3). Just as

authenticity represents the hallmark of country music (Peterson, 1997), it also represents the hallmark of craftsmanship. The craft production of glass in Glasriket is an instance of the abstract phenomenon of authenticity construction. The craft sector provides a context for understanding the issues of authenticity as well as its construction delivered through cultural/marketing production. The research context sets the scene for the work of glass producers and photographers (as marketers) in authenticating market offerings. I turn to craft production for insights into authenticity to explore the ways in which authenticity plays out in a craft production site.

Figure 1. Positioning of this dissertation

In addition to being an empirical instance, craft is a conceptual domain that has been researched by scholars from various disciplines, such as philosophy, anthropology, sociology, design, art history, archeology, and material culture.4 Craft exists as a

practice, a skill, an object, an experience, a person (i.e., artisan), a business (trade or sector), a place (e.g., craft village), and a concept (Baudrillard, 2011; Campbell, 2005; Creighton, 1995; Peach, 2013; Risatti, 2007; Schaefer, 2013; Sennett, 2008). Therefore, craft is not only an empirical existence (see the text in the higher bracket in the box in the bottom in Figure 1) but also a theoretical domain (see the text in the lower bracket in the box in the bottom in Figure 1), given the sizable amount of academic work that has been conducted in multiple disciplines. Section 3.3 in Chapter 3 provides a literature review about craft research pertinent to marketing. Craft has theoretical dimensions, which help with the explanation of the research context. Eyes trained in the craft literature helped me notice something interesting in this research context, as theories of craft enabled my analytical capacity.

4 See two academic journals as dedicated forums and communities focusing on craft research: Craft Research and The Journal of Modern Craft.

To sum up, this dissertation embeds (see the circle connecting the three boxes in Figure 1) a craft research context within the two conceptual realms of authenticity and cultural/marketing production. In another sense, it uses these two theoretical areas as tools to answer questions about craft phenomena. Craft is the contextual issue, while authenticity and cultural/marketing production are the conceptual issues.

1.7 Key terms, terminologies, and glossary

1.7.1 Key terms

Craftsmanship: The Oxford Dictionary defined “craftsmanship” as “skill in a particular craft” (en.oxforddictionaries.com). Sennett (2008) defined craftsmanship as “an enduring, basic human impulse, the desire to do a job well for its own sake” (p. 9) and “the skill of making things well” (p. 8). For Sennett, craftsmanship includes not only traditional, skilled manual labor, such as pottery making, weaving, and carpentry, but also modernized, technology-assisted undertakings, like Linux programming or the medical practices of a doctor. There are some similar terms: craft, handicraft, artisanal, and so on. The concept will be further explained in Chapter 3 (Section 3.3).

Represent: The verb “represent” means “to symbolize” or “to stand for something that is not present” (Williams, 2014, p. 206). In art and literature, a representation is a symbol or a visual embodiment of something or the process of presenting to the eye or the mind (Williams, 2014, p. 208). The noun “representation” is tied to a sense of “accurate reproduction” (ibid., p. 208). A representation can be a symbol or an image. According to Hall (1997), “representation” is “the production of the meaning of the concepts in our minds through language. It is the link between concepts and language which enables us to refer to either the ‘real’ world of objects, people or events, or indeed to imaginary worlds of fictional objects, people and events” (p. 17; emphasis in the original).

Authenticity: This term has been addressed in multiple disciplines and is notoriously difficult to define due to its polysemous, fluid, and contested nature. A unifying concern is the desire to locate the true or “real” expression of something in the face of the trends toward homogenization, rationalization, and standardization that have characterized modern life (Weber, 1978). Beverland and Farrelly (2010, p. 839) offered an explanation hinting about the connotations of the term: “… despite the multiplicity of terms and interpretations applied to authenticity, ultimately what is consistent across the literature is that authenticity encapsulates what is genuine, real, and/or true.” The concept will be further explained, reified, and discussed in the dissertation (in the literature review in Chapter 3, empirical findings in Chapter 5, and discussions in Chapter 6).

1.7.2 Terminologies in semiotics applied in the analysis of visual data

In this dissertation, photographic images are analyzed as visual data, in addition to other types of data. Semiotics is applied as the methodological tool in the analysis. Below are the key terminologies concerning semiotics to enable the reading of the relevant parts.

• Semiotics: The term semiotics has been used by researchers in two ways. First, it can refer to the social science discipline specializing in the study of signs from a cultural perspective; it is a social science discipline that extends the laws of structural linguistics to the analysis of verbal, visual, and spatial sign systems (Oswald, 2012). Second, it can refer to the ensemble of signifying operations at work in a sign system, which can be an advertising text, a retail setting, or a brand (ibid.).

• Semiology: Similar to semiotics, the word semiology has been used

interchangeably with semiotics to refer to the science of signs (Mick, 1986). • Semiosis: This refers to the process of communication by a sign, which

stands for something (its object), to somebody (its interpreter), in some respect (its context), according to Peirce’s theory (Mick, 1986, p. 198). In a broader sense, semiosis refers to the dynamics of meaning production (Oswald, 2012) or the act of signifying (Fiske, 1990). The overall process of semiosis is the basic subject of semiotics.

• Sign, object, and interpretant: C. S. Peirce’s (1985) semiotic approach identifies a triangular relationship among the three basic elements: sign, object, and interpretant (Nöth, 1990; Peirce, 1998). The sign stands for something other than itself (the object). The object is something tangible and real in the world (Rose, 2016). The interpretant does not mean the interpreter or an interpretation but a mental image held by the interpreter as a reaction to the sign (Christensen & Askegaard, 2001).

• Referent: This is something that a sign represents. It is also called “the object,” which is something tangible and real in the world (Rose, 2016). • Signifier and signified: According to Saussure’s structural linguistics, the

basic linguistic unit, the sign, consists of two components: the signifier and the signified (Saussure, 1915). The signifier is the material form and can be the image, sound, object, or word. The signified is the meaning or mental concept to which the signifier refers (Fiske, 1990). For example, a rose, as a signifier, symbolizes the meanings of “romance and love,” which are the signified.

• Indexical, iconic, and symbolic signs: As for the logical relationship between the sign and its object, Peirce (1955) created a taxonomy of three types of sign: iconic (based on resemblance), indexical (based on causal correspondence), and symbolic (based on convention). In iconic signs, the signifier represents the signified by having a likeness or resemblance to it. A photograph of a piece of glassware is an iconic sign of that object. For an indexical sign, the signifier relates to its signified by some correspondence of fact, and the relationship is frequently causal. As an example of an indexical sign, an image showing smoke infers the existence of fire. In symbolic signs,

the relationship between the signifier and the signified is based on cultural conventions and the relationship is arbitrary. The concept that diamonds represent “love forever” is a classic example of a symbolic sign, as there is no intrinsic relationship between the stone of a diamond and a long-term love relationship.

1.7.3 Glossary related to the research context

• Bruk: This a Swedish word, stemming from the Swedish word “att bruka” (“to use”); it also means “glass factory,” which is a building in which glass making takes place. In Swedish, “bruk” refers only to glass factories rather than factories in other sectors.

• DMO: Destination marketing organization.

• Glasbruk: This a Swedish word, meaning glass factory.

• Glasriket: Swedish people use this word to refer to the region called “the Kingdom of Crystal,” which is an industrial region making glass products and a tourist destination, located in Småland in southern Sweden. The name “the Kingdom of Crystal” is used more by international audiences.

• Glassworks: This a Swedish word, referring to a company that runs the business of manufacturing and selling consumer glass products. It also refers to a factory where glass manufacturing is conducted.

• Hot shop: This refers to the central part of a glass factory, where the furnace is located.

1.8 Outline of the dissertation

This dissertation is organized as follows.Chapter 2 “The context: Glasriket or the Kingdom of Crystal” introduces the research context, the region of Glasriket, to contextualize the study by touching on various pertinent dimensions of the region, which will be dovetailed implicitly with the two theoretical domains—authenticity and cultural/marketing production. It has four major sub-sections: a reflection on the choice of this research context in a theoretical sense, the general background, two anchors of authenticity (the craft mode of manufacturing and craft-manufacturing-induced tourism), and cultural/marketing production in this region. The last sub-section consists of four areas: marketing communications of three types of organizations, the photographer John Selbing as an exemplary creative worker and marketer, photographic images as cultural products, and the art dimension.

Chapter 3 “Theoretical inspirations” contains reviews of the literature in three theoretical domains: authenticity, cultural/marketing production, and craft. Finally, the relationships among the three domains are analyzed and a conceptual framework is presented.

Chapter 4 “Methodology” discusses various aspects of the methodology used in this dissertation: the research philosophy and approach, the gathering of empirical data, the analyses of data yielding findings in three areas corresponding to the three research questions, a reflection on the research quality, and considerations about ethics and copyright.

Chapter 5 “Findings” comprises three sub-sections. Section 5.1 “Substantive construction of the authenticity of market offerings via craft production” addresses RQ1. Section 5.2 “Communicative construction of authenticity via photographers’ practices of image making” addresses RQ2. Section 5.3 “Relationships between the two types of production” addresses RQ3.

Chapter 6 “Discussion” first reiterates the empirical findings addressing the three research questions and cross-views them to see how they fit into the two theoretical domains to which this dissertation aims to make contributions (Section 6.1). Then, Section 6.2 and Section 6.3 abstract from the research context and empirical findings and branch out to broader issues. This is achieved by linking the empirical findings to strands of conversations in the two domains of “authenticity” and “cultural/marketing production” to make contrasts and comparisons, produce theoretically informed implications, and argue theoretical contributions. Section 6.2 “Authenticity rendered in production” contains discussions in five strands of conversations under the rubrics of “authenticity,” and Section 6.3 “Production that authenticates” includes discussions in four strands of conversations under the rubrics of “cultural/marketing production.”

Chapter 7 “Conclusion” ends this dissertation with four sub-sections: theoretical contributions, managerial implications, limitations, and future research.

2 The context: The Kingdom of Crystal

(“Glasriket”)

This chapter introduces the research context of Glasriket, trying to contextualize the study by touching on various pertinent dimensions of the region, which will be dovetailed implicitly with the two theoretical domains—authenticity and cultural/marketing production. This chapter starts with a reflection on the choice of this research context in a theoretical sense (2.1), followed by the introduction of the general background of this region (2.2), consisting of four areas: general profile, community and regionality, glass as a material and objects, and glass products in consumption. Section 2.3 introduces two anchors of authenticity: the craft mode of manufacturing and craft-manufacturing-induced tourism. Section 2.4 concludes this chapter by introducing four areas of cultural/marketing production in this region: marketing communications of three types of organizations, the photographer John Selbing as an exemplary creative worker and marketer, photographic images as marketing texts and cultural products, and the art dimension.

2.1 Seeing this research context theoretically

Authenticity needs to be evaluated in certain contexts. Researchers have made the claim that authenticity should be analyzed in each contextual setting (Bruner, 1994; Gundlach & Neville, 2012). Bruner (1994, p. 401) pointed out, “The problem with the term authenticity, in the literature and in fieldwork, is that one never knows except by analysis of the context which meaning is salient in any given instance.” The meaning given to authenticity is context and goal dependent (Arnould & Price, 2000; Rose & Wood, 2005; Wang, 1999). Given this nature of authenticity, the current study selected “the Kingdom of Crystal” (“Glasriket” in Swedish) as the research context that sets the scene in which the two types of production (glass making and image making) operate.

As demonstrated by the following sub-sections in this chapter, the properties of this research context are uniquely identified as significant and relevant to the research on the construction of authenticity through cultural/marketing production. First, consumer glass products are quasi-cultural products that have a strong tilt toward the esthetic, visual, and material dimensions. Glass products and the attendant visual images are “highly symbolic and richly connotative product classes” (Mick & Buhl, 1992, p. 320), and authenticity entails issues of meaning and symbolism (Beverland, 2005b). Second, craft is entangled with authenticity (Hartmann & Ostberg, 2013; Smith Maguire, 2018; Thurnell-Read, 2019), and the craft sector is subject to debates and contestations over authenticity. Third, with some of the oldest glass brands still in existence, this context potentially holds important insights into historicity, a key attribute of authenticity (Beverland, 2005b; Gundlach & Neville, 2012). Fourth, this region has comprehensive marketing communication elements consisting of