Goodwill

impairment factors

in Sweden

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration MAJOR IN: Accounting

NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Civilekonomprogrammet AUTHOR: Kristoffer Engberg & Jörgen Schenberg JÖNKÖPING October 2020

i

Acknowledgements

First of all, thanks to Jönköping International Business School for four years of great education and experiences.

We would like to thank our supervisor Ulf Larsson Olaison for his contributions to this thesis, for his insightful comments and for always taking his time to help us.

Thanks to the participants in our seminar group for all their valuable feedback throughout the process of this thesis.

We would also like to thank ourselves and each other for hanging in there, even when the times have been tough.

Finally, we would like to express our gratitude towards our families and friends for believing in us, supporting us and respecting our intensive periods of self-isolation.

Jönköping International Business School October 2020

_________________________ _________________________

ii

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Goodwill Impairment Factors in Sweden

– A study of Large Cap and Mid Cap firms in 2006-2012 Authors: Kristoffer Engberg and Jörgen Schenberg

Tutor: Ulf Larsson Olaison Date: 2020-10-31

Key terms: Goodwill, Impairment, CEO Change, Earnings Management, Big Bath

Abstract

Background: The recent decades there has been a big shift in the focus of accounting standards, going from mostly being based on historical cost to being more based on fair value. How to account for goodwill has been widely discussed for many years. Assets, such as goodwill, that are never traded individually are difficult to assign a fair value to. This opens up for discretionary behavior and earnings management. One of the foundations of financial reporting is that it should contribute to informed decisions, thus the numbers need to be accurate. Goodwill has become an increasing part of firms’ balance sheets, making up 19,3% of the assets of firms listed on Nasdaq Stockholm.

Purpose: This study’s purpose is to examine how impairment factors affect discretionary goodwill impairment decisions in Swedish Large Cap and Mid Cap firms. The first part is to examine the occurrence of goodwill impairment, and the second part is to examine the size of goodwill impairment losses.

Method: The study examines Swedish Large Cap and Mid Cap firms during the years 2006-2012. After excluding some companies for various reasons, we are left with a sample size of 483 firm years. First a logistic regression is run, to investigate what indicators causes firms to make goodwill impairments. The concepts examined are CEO Change, Big Bath, Income Smoothing and Leverage, operationalized into variables and checked to see if they have a relationship with the dependent variable goodwill impairment. Firm size, change in return on assets, change in sales and finally industry are used as control variables. The second regression examines what influences the amount of goodwill impaired, looking at the same independent variables as in the first one, using a censored tobit regression.

Conclusion: The result shows that two variables, Leverage and Big Bath have a significant influence on the occurrence of goodwill impairment. Both variables show a negative influence on the dependent variable, meaning that when they increase, goodwill impairment are less likely to happen. Accepting a lower level of significance, CEO change showed a positive influence on goodwill impairment.

When looking at the 91 firm years when impairment occurs, we see that two variables have a significant influence on the size of the goodwill impairments, that is Leverage and Big Bath.

iii

Acronyms

CEO Chief Executive Officer

EU The European Union

IAS International Accounting Standards

IASB International Accounting Standards Board

ICB Industry Classification Benchmark

IFRS International Financial Reporting Standards

IMF International Monetary Fund

ROA Return on Assets

SEK Swedish Krona

iv

Table of Contents

1.

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Research Problem ... 3 1.3 Purpose ... 6 1.4 Delimitations ... 61.5 Structure of the Thesis ... 7

2.

Literature Review ... 8

2.1 Agency Theory ... 8

2.2 Positive Accounting Theory ... 9

2.3 IFRS ... 10

2.3.1 IASB’s Conceptual Framework ... 10

2.4 Fair Value Accounting ... 12

2.5 Goodwill ... 12

2.6 Goodwill Impairment ... 13

2.7 CEO Change... 15

2.8 Earnings Management ... 17

2.9 Impairment Factors and Hypothesis Development ... 17

2.9.1 Big Bath ... 17 2.9.2 Income Smoothing ... 18 2.9.3 Leverage ... 19 2.9.4 CEO Change... 20 2.9.5 Hypotheses Summary ... 21

3.

Method ... 22

3.1 Research Approach ... 22 3.2 Research Strategy ... 233.3 Sample and Data ... 24

3.4 Data collection ... 25

3.5 Model and Variables ... 25

3.5.1 Dependent variables ... 27 3.5.2 Impairment factors ... 27 3.5.3 Control variables ... 28 3.6 Reliability ... 30 3.7 Replication ... 30 3.8 Validity ... 31

4.

Result ... 32

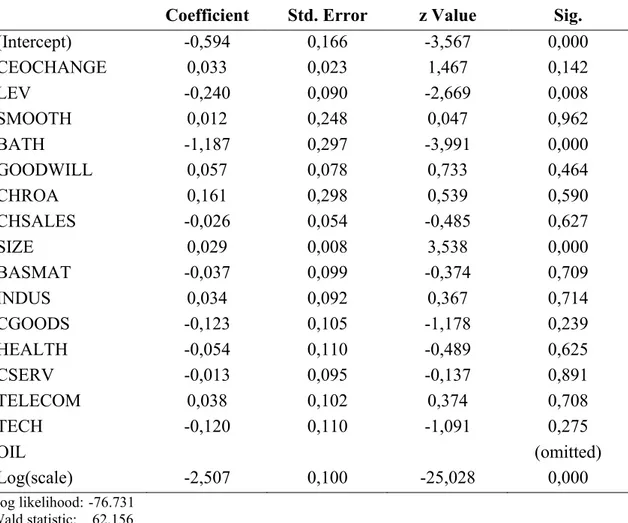

4.1 Descriptive Statistics ... 32 4.2 Correlation Analysis ... 364.3 Logistic Regression Analysis ... 36

4.4 Tobit Regression Analysis ... 38

5.

Analysis ... 39

6.

Conclusion ... 45

7.

Discussion ... 46

7.1 Limitations ... 47

7.2 Ethical Issues ... 48

v

Reference list ... 49

Appendix A - List of firms in final sample ... 52

vi

Figures

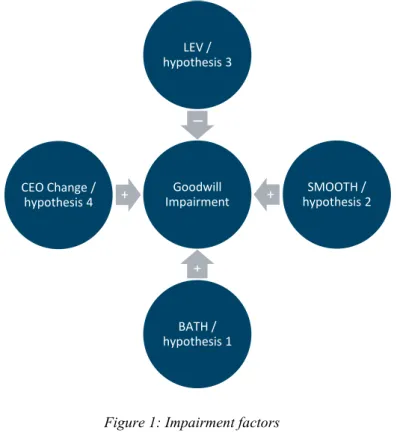

Figure 1: Impairment factors ... 21

Figure 2: The deductive process ... 23

Equations

Equation 1: Logistic regression ... 26Equation 2: Tobit regression ... 26

Tables

Table 1: Fundamental qualitative characteristics, according to IASB ... 11Table 2: Enhancing qualitative characteristics, according to IASB ... 11

Table 3: Sample Selection ... 25

Table 4: Variables ... 26

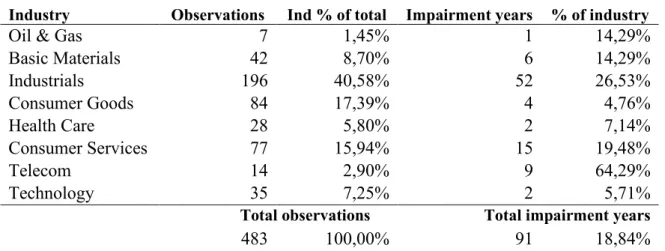

Table 5: Observations by industry ... 32

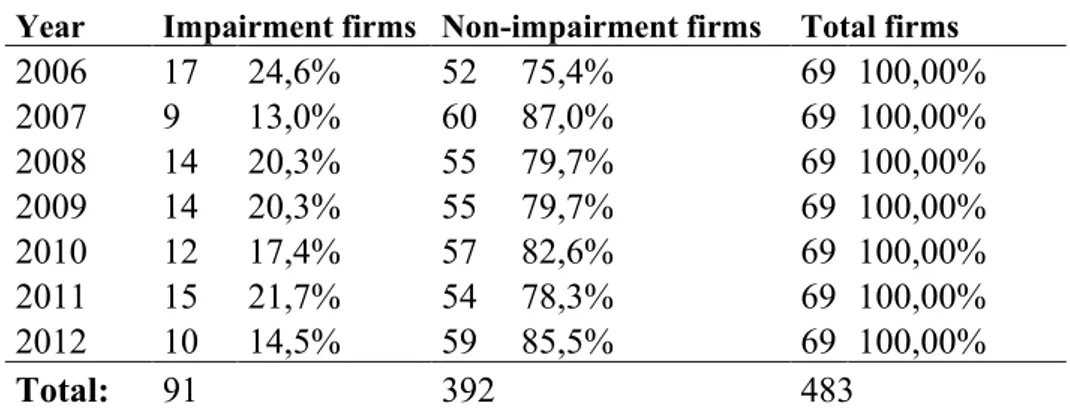

Table 6: Impairments by year ... 33

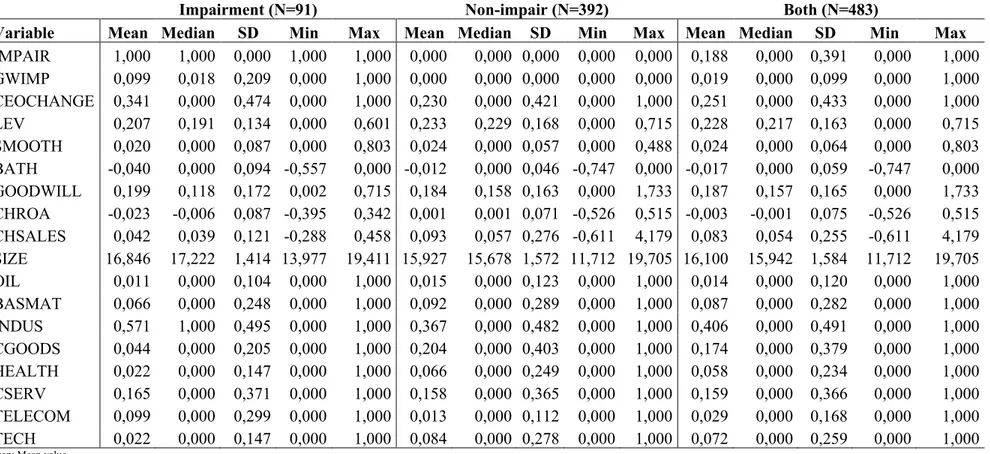

Table 7: Descriptive Statistics - Variables ... 34

Table 8: Pearson Correlations ... 35

Table 9: Logistic regression of goodwill impairment decision ... 36

Table 10: Model summary of the logistic regression ... 37 Table 11: Discretionary determinants of annual goodwill impairment losses 38

1

1. Introduction

_____________________________________________________________________________________ This chapter will provide the reader with a brief backstory and background to financial reporting, goodwill accounting and earnings management. The research problem is then presented, followed by the purpose of the thesis and the research question. Finally in this chapter, a short summary of the structure of this thesis is provided to the reader, to simplify digging into it.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background Backstory

In October 2018, H. Lawrence Culp, Jr. was appointed the new CEO of General Electric Company, GE (Crooks, 2018). Simultaneously with the appointment of a new CEO, they announced a $23 billion goodwill write-off, mostly related to the 2015 acquisition of the French company Alstom. The write-off raised some eyebrows, considering the Alstom acquisition was a $10.1 billion deal, and the write-off was more than twice as big (Crooks, 2018). After the purchase, GE booked $13.5 billion in goodwill, implying that the net assets they acquired had a negative net worth (Crooks, 2018). Later in 2016, GE appreciated the value of goodwill coherent to the deal to $17.3 billion and kept it on that level until 2018 (Rapoport, 2019). Rapoport (2019) states that increasing the value of their goodwill made it possible to avoid costs and not reduce its earnings. It also made it possible to conceal the true state of the deal for some more time. GE tests its goodwill for impairment every third quarter and Crooks (2018) finds it peculiar that they went from a small impairment in one quarter, to find almost all of their goodwill worthless only three months later when repeating the test. In hindsight, the Alstom deal turned out a bad one. For the new CEO, on the other hand, the write-off gave him a good start on his new position, with possibilities to better earnings in the future (Crooks, 2018).

Background

Public companies have various stakeholders such as investors, creditors and suppliers, who have limited access to the company and therefore rely heavily on companies’ financial information (Sundgren, 2013). According to the International Accounting Standards Board, the IASB’s, conceptual framework, the purpose of financial statements is to provide useful financial information to existing and potential stakeholders, which is vital for them to be able to make well-informed decisions regarding investments,

2

acquisitions, loans etc. (International Accounting Standards Board, 2018a). Existing, as well as potential, shareholders need information regarding companies’ current financial position, in order to decide whether to invest or not. Providers of credit need information to mitigate risks associated with lending money and suppliers need the same information to be able to examine a company’s liquidity to make sure that it is safe to provide them credit (Sundgren, 2013).

Despite the fact that many heavily rely on the accuracy of financial reports, IASB mention in their conceptual framework that they are to a large extent estimations and subjective values (International Accounting Standards Board, 2018a), which makes room for arbitrary decisions and opportunistic behavior (Giner & Pardo, 2015).

Assets that are traded on a market such as stocks, options or property are easy to assign a fair value to, but assets not traded like that require estimates to determine a value. One of the assets most subject to arbitrary judgements is goodwill (Lhaopadchan, 2010). According to IFRS 3, Appendix A, the definition of goodwill is “Future economic benefits arising from assets that are not capable of being individually identified and separately recognized” (International Accounting Standards Board, 2018b).

How to account for goodwill has been a widely discussed topic for many years (Abughazaleh, Al‐Hares, & Roberts, 2011; Baboukardos & Rimmel, 2014; Giner & Pardo, 2015; Stenheim & Madsen, 2016). Prior to 2005, goodwill had to be written-off annually, but since 2005 all publicly traded companies in the European Union need to comply with the International Financial Reporting Standards, IFRS, issued by the IASB (Horton, Serafeim, & Serafeim, 2013). The adoption of IFRS 3 meant dealing with goodwill in a new way. Instead of amortizing the historical cost of goodwill annually over a limited period of time, in Sweden often five years, it now had to be tested for impairment annually in line with IAS 36 (Hamberg, Paananen, & Novak, 2011). According to Abughazaleh et al. (2011), the motivation behind this was to achieve international convergence and global harmonization. In accounting, comparability is important and striving for harmonization by reducing differences between countries is one way to accomplish a higher level of this (Barlev & Haddad, 2007).

The testing and reporting of goodwill impairment losses risks being treated opportunistically (Stenheim & Madsen, 2016). Lhaopadchan (2010) claims that many

3

goodwill impairment decisions are associated with managerial self-interest and earnings management. According to Healy and Wahlen (1999), “Earnings management occurs when managers use judgment in financial reporting and in structuring transactions to alter financial reports to either mislead some stakeholders about the underlying economic performance of the company or to influence contractual outcomes that depend on reported accounting numbers” (p.368).

Schipper (1989), another highly cited researcher on the subject, claims that earnings management occurs when someone purposefully intervene in the external financial reporting process, to obtain private gain. She confirms her definition by mentioning the definition made by Davidson, Stickney, and Weil (1987, as cited in Schipper, 1989). They also claimed that earnings management is an intentional way of reaching desired levels of reported earnings and note that the behavior is conducted within the constraints of accounting principles.

There is criticism against discretionary values in accounting, but Healy and Wahlen (1999) claim that managers must be able to exercise some judgment when it comes to financial reporting, to be able to in some way display information they have about the business and its operations, providing investors additional value.

1.2 Research Problem

The adoption of IAS 36 and IFRS 3 has given managers more room for discretionary behavior regarding goodwill impairment, both the occurrence and the magnitude. When a goodwill impairment is recorded opportunistically, or not recorded even though it should be following the financial standards, the result of the company will turn out misleading (Giner & Pardo, 2015).

In the past decades, a shift in valuation technique has been made in accounting standards. Today, there is more emphasis put on the fair value of assets, instead of their historical cost (Hamberg et al., 2011; Lhaopadchan, 2010). One of the very foundations of financial reporting is that it should contribute to decision usefulness, stated by both the IASB and their American equivalent the Financial Accounting Standards Board, the FASB, in their respective conceptual frameworks (Gassen & Schwedler, 2010). Decision-useful financial information’s purpose is to be helpful for those providing capital to an entity, such as investors, creditors and lenders, when making decisions. To be useful when in the

4

process of making decisions it is important that the information is relevant, reliable, comparable and understandable (International Accounting Standards Board, 2018a). For assets that are actively traded in liquid markets, it is possible to get highly reliable and relevant fair values assigned to them, contributing to decision usefulness. Being an investor, a low level of information asymmetry between investors and managers is desirable (Frankel & Li, 2004). According to Beke (2012) “Accounting theory argues that financial reporting reduces information asymmetry by disclosing relevant and timely information” (p.116).

For assets that are rarely traded or cannot be separated and identified, it is more difficult to assign a fair value. This is the case with goodwill, it is easy to find the value during an acquisition, the purchase price less the fair value of the acquired firm’s assets. After an acquisition, it is much more difficult to determine the value of goodwill, and this opens up for opportunistic behavior (Lhaopadchan, 2010). Impairment testing leaves room for management’s judgment, interpretation and bias. It leaves managers with more flexibility regarding the value of goodwill, whether to impair it, and by how much (Malijebtou Hassine & Jilani, 2017).

The flexibility provided to managers when testing goodwill for impairment could be a problem, if managers’ motives are opportunistic. Managers’ opportunistic behavior is an assumption of the Agency Theory where the two parties, the principal and the agent, are both expected to be utility maximizers. The CEO (the agent) is hired by the shareholders (the principal) to act on their behalf, and some decision authorization is transferred from the principal to the agent. The principal wants the agent to act with the principal’s best interest in mind, but their interests will most likely not be aligned at all times. If the CEO is opportunistic, the discretion provided in financial standards can be used for the CEO’s personal gain (M. C. Jensen & Meckling, 1976).

Managerial opportunism is also an assumption of the Bonus Plan Hypothesis in Positive Accounting Theory which deals with motivations behind accounting choices. According to the Bonus Plan Hypothesis, managers are expected to make accounting choices that will benefit their own wealth (Watts & Zimmerman, 1990). According to the earnings management definition by Shipper (1989), a CEO who would purposefully intervene in the financial reporting and understate or overstate goodwill impairment losses to obtain personal gain, would be considered a case of earnings management.

5

There are several factors that offers incentives to earnings management. According to previous studies, CEO change, leverage, big bath and income smoothing are some of the factors that influence the decision to record goodwill impairments. When firms change CEO, there can be an opportunity to manipulate the earnings by recording goodwill impairments and steer bad result to the former CEO to benefit the new CEO. This can result in misleading and unreliable financial information (J. Godfrey, Mather, & Ramsay, 2003).

One way for the CEO to manipulate the earnings is called big bath. When the firm experience a bad year, the CEO might take the opportunity to record a goodwill impairment and increase that loss, in favor for a better result the upcoming years. Getting rid of some goodwill in a bad year will make it easier to reach earnings goals in upcoming years (Jordan & Clark, 2015).

Another similar way for the CEO to manipulate the earnings is income smoothing. While a big bath is done when the firm is experiencing a bad result, the income smoothing is done when the firm is experiencing higher earnings than usual. Firms usually do not want the earnings to fluctuate too much, instead they want it to increase regularly. By recording goodwill impairments in these good years, the CEO can avoid this irregularity and achieve a smoothing of earnings (Jahmani, Dowling, & Torres, 2010).

While big bath and income smoothing are two ways of earnings management by reducing the result, the manager can also use income-increasing methods. According to the Positive Accounting Theory, managers of firms with high leverage (debt/equity) are more likely to use income-increasing methods (Watts & Zimmerman, 1990). Higher leverage means closer to constraints in a debt covenant. Violation of the constraints in a debt covenant could be costly, and therefore a firm with high leverage are expected to be less likely to record a goodwill impairment since that would lower the result (Abughazaleh et al., 2011; Beatty & Weber, 2006).

Goodwill is becoming an increasingly larger, and because of that more important, part of many firms’ balance sheets (Lhaopadchan, 2010). Gauffin and Nilsson (2020) have, in the Swedish accountant association magazine “Balans”, been tracking goodwill and goodwill impairments since the adoption of IFRS in 2005. They have seen that the amount of goodwill related to total assets have been increasing since then, with goodwill

6

accounting for a portion of 19,3% of total assets in firms listed on the Stockholm stock exchange, sometimes even exceeding shareholder’s equity. Given the increasing portion of goodwill, voices have been raised claiming that amortization might be worth another try. Gauffin and Nilsson also analyzed acquisitions made by Swedish public companies in 2018 and found that 59% of the price paid in acquisitions was derived to goodwill (Gauffin & Nilsson, 2020).

The transition from annual goodwill amortization to the impairment testing in the new IFRS standards has given management more room for subjectiveness. The shift has opened up for more judgments and bias (Chalmers, Godfrey, & Webster, 2011). Standard-setters and policy makers are responsible for how much room for judgment are allowed in financial standards. Therefore they are interested in empirical data on how firms and managers act in relation to goodwill impairment, and what factors that influence goodwill impairments, especially after the introduction of new standards (Abughazaleh et al., 2011). This study could contribute with empirical evidence on how managers act in relation to goodwill impairments.

1.3 Purpose

This study’s purpose is to examine how impairment factors affect discretionary goodwill impairment decisions in Swedish Large Cap and Mid Cap firms. The four impairment factors examined are CEO change, Big Bath, Income Smoothing and Leverage. The first part is to examine the occurrence of goodwill impairment, and the second part is to examine the amount of goodwill impairment losses.

This leads to the following research question:

How do goodwill impairment factors affect discretionary impairment decisions in Swedish Large Cap and Mid Cap firms?

1.4 Delimitations

The scope of this thesis is limited to firms on Nasdaq Stockholm’s Large Cap and Mid Cap in the years 2006-2012. Firms with no goodwill balance in their balance sheets, and firms belonging to the financial industry have been excluded.

7

1.5 Structure of the Thesis

For this thesis, the following structure has been chosen. The introduction is followed by a literature review, summarizing earlier research in the field as well as theories linked to the problem. This chapter provides a theoretical background but also launches the hypotheses. After this, the methodology will be presented, both from a theoretical perspective but also empirically, explaining the model and the variables used in this thesis. This chapter is followed by a presentation of the descriptive statistics and the outcome of our regression analyses, which are later analyzed in chapter five. The findings and the analysis are then summarized in chapter six, the conclusion. In the seventh chapter we elaborate further on the findings and discuss the limitations of the study and the ethical issues. Some suggestions for further research are also included in this chapter. For those interested in reading even more, the references are attached in the very end of the thesis.

8

2. Literature Review

_____________________________________________________________________________________ This chapter will provide the reader with a deeper, theoretical background to the subject. It starts with an introduction of two grand theories related to the research problem, which is followed by a presentation of the foundations of financial reporting, the regulators and the regulations. From that broad perspective, the focus then shifts into a more narrow one, focusing on goodwill and goodwill impairment. After a brief section on earnings management, the impairment factors relevant in this thesis is presented, along with the hypotheses and a model summary of those.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

2.1 Agency Theory

Already in 1776, in his influential book, The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith elaborated on the subject of managing other people’s money versus managing your own. He implied that it cannot and should not be expected that someone in a company managing other people’s money would do it as eagerly and vigilant as someone in a partnership would, managing one’s own equity. This problem is highly relevant when looking at the Agency Theory (Smith, 1776).

Jensen and Meckling (1976) expanded further on this subject. When discussing the agency problem there are two parties involved, the principal and the agent. The agent is hired by the principal to act on the principal’s behalf, and some decision authorization is transferred from the principal to the agent, a “separation of ownership and control” occurs (M. C. Jensen & Meckling, 1976). In a publicly owned company, the shareholders can be seen as the principal, and the chief executive officer as the agent (M. Jensen & Murphy, 1990).

According to the Swedish Companies Act “Aktiebolagslagen”, the CEO is hired to run the day-to-day operations on behalf of the board of directors. The board of directors is elected by the annual general meeting, the shareholders, to govern the company (Aktiebolagslag, SFS 2005:551).

Jensen and Meckling (1976), assume that all parties involved are utility maximizers, which most likely will lead to situations where their interests are not aligned. This is a typical example of the principal-agent problem. One aspect of the principal-agent problem is the information asymmetry. Most of the time the shareholders do not have all information regarding the CEO activities and investment opportunities in the company

9

(M. Jensen & Murphy, 1990). There will be moments where the CEO will make decisions that benefit him or her instead of always having the shareholders’ best interest at heart. The principal need to take measures to make sure that the agent will act in a way that benefits the principal, this cost is part of what is called agency cost. In agency cost we also include residual loss, wealth reduced when the agent does not act in the best interest of the principal, and bonding cost, measures taken that will guarantee that the agent not act against the principal’s interest (M. C. Jensen & Meckling, 1976).

There is a need to incentivize the CEO to act in line with the principal’s interest, for example by making part of the remuneration linked to performance goals (M. C. Jensen & Meckling, 1976). According to Jensen and Meckling (1976) it is almost impossible to get the agent to always act with the principal’s best interest of heart without having to pay for it.

One way to strive against an alignment of goals and to reduce agency cost is for the CEO to also be invested in the company, thus share an interest with the shareholders, (M. C. Jensen & Meckling, 1976). But in reality, most CEOs hold a rather insignificant portion of shares in their firms (M. Jensen & Murphy, 1990).

2.2 Positive Accounting Theory

Positive Accounting Theory deals with accounting choices, and the incentives behind the choices. Managers are expected use the information asymmetry to their own benefit and to maximize their own wealth (Watts & Zimmerman, 1990).

The accounting choices are affected by different factors linked to three hypotheses, striving to explain the accounting choices made, The Bonus Plan Hypothesis, The Debt/Equity Hypothesis and The Political Cost Hypothesis (Watts & Zimmerman, 1990). The Bonus Plan Hypothesis is linked to managers’ incentive bonus plans. To maximize one’s bonus, a manager might act opportunistically to improve the result of the company. One way to do accomplish that is to avoid a goodwill impairment which would affect the result negatively (Watts & Zimmerman, 1978).

Another part of Positive Accounting Theory is the Debt/Equity hypothesis. The idea behind this hypothesis is that if a firm has a high debt to equity ratio, managers tend to choose accounting methods that will increase the income. With a high debt to equity ratio,

10

the firm will be firmly constrained by debt covenants, and closer to risk a violation leading to a costly technical default (Watts & Zimmerman, 1990). Watts and Zimmerman (1990) claim that “The evidence is generally consistent with the debt/equity hypothesis” (p. 139). The last hypothesis of Positive Accounting Theory is the political cost hypothesis. It “predicts that large firms rather than small firms are more likely to use accounting choices that reduce reported profits” (Watts & Zimmerman, 1990, p. 139). In this hypothesis, size is used as a proxy for unwanted political attention. Too high profits could lead to for example stricter rules or higher taxes (Watts & Zimmerman, 1990).

2.3 IFRS

To be able to communicate financial information to a firm’s external stakeholders in a credible way, there are rules and standards that need to be followed. Standard-setters are responsible for defining what needs to be communicated, and how it should be communicated to stakeholders, depending on relevant and reliable financial information to be able to make the right decisions (Healy & Wahlen, 1999).

In 2002, the European Union Parliament decided that in all fiscal years beginning after 1 January 2005, publicly listed companies in the European Union need to comply with the International Financial Reported Standards issued by the IASB (Soderstrom & Sun, 2007).

2.3.1 IASB’s Conceptual Framework

The IASB has issued standards treating all kind of financial reporting matters, but they have also issued a comprehensive “Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting”, meant to assist all parties concerned. It is supposed to help standard-setters design consistent standards, to guide preparers on how to deal with transactions that no standard applies to and finally to help all stakeholders understand and interpret the standards (International Accounting Standards Board, 2018a).

According to IASB’s conceptual framework, the objective of financial reporting “is to provide financial information about the reporting entity that is useful to existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors in making decisions relating to providing resources to the entity” (IASB 2018, 1.2). This could mean for example buying equity, providing credit or exercising voting rights.

11

For financial information to be useful, IASB has listed some qualitative characteristics that it should meet. There are two criteria that must be met, the information needs to be relevant, and faithfully represented.

Fundamental qualitative characteristics, according to IASB

Table 1: Fundamental qualitative characteristics, according to IASB

Relevance When financial information is relevant, it contributes to decision usefulness for its users. It can help stakeholders make decisions if it has predictive value, confirmatory value or both (IASB 2018, 2.6-2:7)

Faithful representation

Preparers of financial information should strive for it to be complete, neutral and free from error. One part of neutrality in this case is to exercise prudence. Assets and income should not be overstated and liabilities and expenses should not be understated. The same goes for the opposite situations. (IASB 2018, 2:12-2:16

Information that meet the two fundamental criteria, can be even more valuable to users if it possesses one or more of the following characteristics. Comparability, verifiability, timeliness and understandability can enhance the information, increasing usefulness even more.

Enhancing qualitative characteristics, according to IASB

Table 2: Enhancing qualitative characteristics, according to IASB

Comparability Financial reports have higher value to its users if it can be used to compare different companies, or to compare different time periods or dates for one company. It can help users decide whether to sell or hold an investment, or decide on which company to invest in (IASB 2018, 2.24).

Verifiability Verifiability can give assurance that information is faithfully represented. “Different knowledgeable and independent

12

observers could reach consensus, (…), that a particular depiction is a faithful representation” (IASB 2018, 2:30).

Timeliness If the information should be useful in decision-making it needs to be produced and distributed in time. If it is delayed too long, it won’t be as valuable. Up-to-date information is important, but old information can also be important to be able to identify trends (IASB 2018 2.33).

Understandability Information needs to be presented in a clear and concise way to

be understandable. It is reasonable to assume that user have an acceptable level of insight in business and economic activities (IASB 2018 2:34-2:36).

2.4 Fair Value Accounting

Traditionally, accounting has to a high degree been based on historical cost (Lhaopadchan, 2010). Several claims have been made that along with the implementation of International Financial Reporting Standards, accounting is taking a step toward full fair value accounting (Cairns, 2006). Cairns (2006) argues that this process began decades before the implementation of the IFRS:s, and many countries already had adopted it into their national standards.

Hitz (2007) claims that an important objective in the ongoing paradigm shift from historical value to fair value, is the decision usefulness. Gassen and Schwedler (2010), on the other hand, claim that researchers have failed to come up with a fair method to compare and rank different accounting concepts when it comes to decision usefulness. They found some empirical evidence by surveying professional investors and advisors, letting them rank different accounting concepts, ultimately showing them favoring fair value accounting, for decision usefulness (Gassen & Schwedler, 2010).

2.5 Goodwill

Goodwill and how to account for it has been a controversial topic in accounting for many years (Abughazaleh et al., 2011; Baboukardos & Rimmel, 2014; Giner & Pardo, 2015; Stenheim & Madsen, 2016). Today, it has been subject to controversy for more than a

13

century, being widely discussed since the beginning of the 20th century (McCarthy & Schneider, 1995). There have been discussions whether it should be recognized as an asset, and also if recognized as an asset, should it be amortized, and if amortized, for how long (McCarthy & Schneider, 1995)?

Goodwill can either be acquired through a purchase or developed internally. Internally developed goodwill cannot be recognized in a company’s financial statements, since it does not meet the criteria required to be recognized as an asset according to IAS 38 (International Accounting Standards Board, 2014).

According to IFRS 3, goodwill is “an asset representing the future economic benefits arising from other assets acquired in a business combination that are not individually identified and separately recognised”(IFRS 3, Appendix A). Hamberg et al. (2011) define goodwill as the difference between the purchase price in an acquisition and the value of the assets of the acquired firm.

To pay an excess purchase price, or premium, is something that an acquirer might be willing to do, for example when expecting to gain synergy effects from the acquisition (Gore & Zimmerman, 2010). Also, sometimes, “The presumption is that the whole (the entire business) is greater than the sum of the parts (the assets)” (Gore & Zimmerman, 2010, p.46).

2.6 Goodwill Impairment

In 2001, the Statement of Financial Accounting Standard, SFAS 142 was implemented in the US by the FASB. The adoption of this standard changed the way to account for goodwill from amortization of historical cost to annual impairment tests, a fair value approach (Hamberg et al., 2011). The FASB claimed that this new approach would better reflect the underlying economic values of goodwill and other intangible assets derived from acquisitions (K. Li & Sloan, 2017). Chalmers et al. (2011) studied Australian firms and found empirical evidence that supported this statement, and by that also the change in accounting regulations.

According to the FASB’s and IASB’s conceptual frameworks, both standard-setters consider that one of the objectives of financial reporting is to contribute to decision usefulness. To benefit users of financial reports, the information provided in them need to be relevant, faithfully represented and understandable (Financial Accounting Standards

14

Board, 2010; International Accounting Standards Board, 2018a). Straight-line amortization provides no value to users of financial reports (Wines, Dagwell, & Windsor, 2007).

In March 2004, the IASB followed in the steps of their U.S. equivalent, the FASB, when they introduced IFRS 3 - Business Combinations and IAS 36 – Impairment of Assets (Abughazaleh et al., 2011).

The updated procedure of dealing with goodwill has attracted criticism. For the management, annual impairment tests come with a new and continuous responsibility, and for stakeholders such as investors and auditors, a new concern is added when they need to critically assess the management’s impairment decisions (Hayn & Hughes, 2006). The previous way of dealing with goodwill, amortizing the historical cost, also attracted criticism, since deciding on the length of useful life left room for opportunistic behavior (Giner & Pardo, 2015).

Riedl (2004) states that there are challenges when it comes to the evaluation of long-lived assets for impairment. When evaluating intangible long-lived assets such as goodwill, there is a need for forecasting, which involves judgements and estimates (Riedl, 2004). Also, when evaluating goodwill, there are no available fair values from a market, since it is not a separable economic unit (Holthausen & Watts, 2001). Holthausen and Watts (2001) further imply that when using estimated values not based on actively traded market prices, the probability for opportunistic behavior increases. Since there are no market prices available for goodwill, when testing for impairment, a fair value must be estimated using other kinds of market information (Cairns, 2006).

According to Hayn and Hughes (2006) one of the challenges linked to goodwill impairment is that it is difficult for stakeholders to evaluate the accuracy of the information regarding impairment. Acquired businesses are often integrated into the company group in various ways, and not operated separately from others, which makes it difficult to see their individual performance. Integrating the acquired business may make it unrecognizable, either as part of something bigger, or split between several business units (Hayn & Hughes, 2006). Hamberg et al. (2011) claim that researchers have found empirical evidence in the US that this new way of dealing with goodwill has increased the decision usefulness slightly, but do also mention that it might be difficult to apply this

15

information on a European setting, due to differences in former regulations. When amortizing goodwill, American firms usually did this over longer periods, up to 40 years, not affecting reported earnings as much as in the case with European firms, who often amortized goodwill over shorter periods of time. Looking at Sweden until the year of 2002, firms needed to amortize goodwill over a time period of five years, unless they could estimate a longer useful life with reasonable accuracy. From 2002 until the adoption of IFRS, the possible amortization period was prolonged from 5 years to 20 years (Hamberg et al., 2011).

Hamberg et al. (2011) investigated the effects the adoption of IFRS 3 had for Swedish companies. They found that the levels of goodwill increased a lot the years following the change to IFRS 3. The average goodwill impairments were much smaller than the amortizations and goodwill impairments under previous regulations (Hamberg et al., 2011).

Abughazaleh et al. (2011) studied how the adoption of IFRS affected firms in the U.K. They claim that the process of testing goodwill for impairment have incurred lot of criticism for the inherent managerial discretion permitted by standard-setters. When studying the matter, Abughazaleh et al. found that the discretionary behavior exercised, was more likely to imply the provision of private information regarding the state and expectations on the company, than as opportunism.

2.7 CEO Change

Chief executive officers are hired by a company’s board of directors to run its day-to-day operations (ABL 8:29) and their importance to a firm’s success is vital (Hambrick & Quigley, 2014). Studies have shown that CEO’s average time in office are decreasing, leading to more frequent CEO changes (Masters-Stout et al., 2008). Several scholars have examined the occurrence and magnitude of goodwill impairments surrounding CEO changes. Most of them found a positive relationship between CEO changes and goodwill impairment, suggesting that firms who change CEO tend to impair goodwill to a larger extent than those not changing their CEO (Abughazaleh et al., 2011; J. Godfrey et al., 2003; Jordan & Clark, 2015; Lapointe‐Antunes, Cormier, & Magnan, 2008; Malijebtou Hassine & Jilani, 2017; Masters-Stout, Costigan, & Lovata, 2008; Wells, 2002).

16

Looking at the relationship between CEO changes and goodwill impairment, earlier studies have shown that new CEO’s tend to lower earnings (big bath accounting) in the succession year (Abughazaleh et al., 2011). Their predecessor counterparts might be less willing to make goodwill impairments if they were the ones responsible for the acquisition decision, since acknowledging a goodwill impairment loss might affect their reputation. It would signal that they paid too much, that they overestimated the synergies expected from the deal or that they failed to realize the synergies (Lapointe‐Antunes et al., 2008). Admitting to shareholders that they made a mistake in an acquisition might be undesirable for many CEOs (Harbert, 2002).

Masters-Stout, Costigan and Lovata (2008) looked into Fortune 500 companies in the years 2003-2005, the years after the issuance of SFAS No. 142, and found that new CEOs impair more goodwill than their predecessors. They hypothesize that the predecessor CEOs might be less willing to impair goodwill since it may throw a shadow on former acquisition decisions made by them or decrease their compensation if linked to performance goals. New CEOs on the other hand, might be motivated to impair goodwill, for example to lower future expectations. The reason could also be that new CEOs, especially when recruited externally, look at the earlier acquired goodwill with fresh eyes (Masters-Stout et al., 2008). Beatty and Weber (2006) also found support for the claim that new CEOs impair more goodwill. They found CEOs who were not responsible for the original acquiring of the goodwill to be more likely to record a goodwill impairment, than those involved in the acquisition.

Wells (2002) looked into the occurrence of opportunistic earnings management behavior surrounding CEO changes in Australia. He hypothesized that when companies change CEO, they tend to use earnings management to decrease the result, to take an “earnings bath”. This behavior is hypothesized to be even more occurring after a non-routine CEO change. To examine this, he delved into companies’ accruals to find evidence for earnings management and ended up finding some evidence for his claims, especially that the occurrence of earnings management was more frequent after non-routine CEO changes. Wells (2002) claims that downward earnings management usually comes with criticism regarding previous decisions, criticism that does not affect the incoming CEO. If the CEO change was non-routine, for example a firing, the outgoing CEO is unable to prevent downwards earnings management, and cannot protect his or her legacy (Wells, 2002).

17

2.8 Earnings Management

One purpose of financial standards is to add value to financial reporting, by increasing comparability and making it possible to separate functional from dysfunctional firms. One way to add value to financial reporting is by having standards with room for managers to convey their private information on how their firm is performing. This is done by permitting some managerial discretionary behavior, for example when choosing standards or making estimates. “Ideally, financial reporting therefore helps the best-performing firms in the economy to distinguish themselves from poor performers and facilitates efficient resource allocation and stewardship decisions by stakeholders” (Healy & Wahlen, 1999, p. 366). Performed properly, this is “potentially increasing the value of accounting as a form of communication” (Healy & Wahlen, 1999, p. 366), but it also opens the door to managerial opportunism in the form of earnings management. When managers act opportunistically they make decisions in their financial reporting that do not provide stakeholders with a fair picture of the economy of their firms (Healy & Wahlen, 1999).

Understating or overstating goodwill impairments do not only affect the current year, but also the following years, leaving room for either more or less flexibility in the upcoming years (Malijebtou Hassine & Jilani, 2017).

2.9 Impairment Factors and Hypothesis Development

Following earlier research, considering managerial incentives and theories regarding earnings management, the following concepts have been identified as influential, and therefore important to examine, Big Bath, Income Smoothing, Leverage and CEO Change.

2.9.1 Big Bath

One way to manipulate earnings is called big bath accounting, taking a “big bath”. When firms already know that they are going to have a bad year, with bad earnings, according to the big bath theory, some managers take the opportunity to charge big non-recurring costs. There is a big advantage to this behavior, increasing the loss in one year, taking a “big bath”, can boost the upcoming years since firms have gotten rid of the burden of some big non-recurring costs. Being rid of those, it will be easier to overcome earnings goals in the upcoming years (Jordan & Clark, 2015). Externally, those years will please

18

stakeholders and the market. Internally, it will be easier for managers to overcome threshold for gaining bonuses. Also, Jordan and Clark (2004) state “There seems to be little additional penalty for missing the earnings mark by a lot rather than by a little” (p.68).

Malijebtou Hassine and Jilani (2017) found support that French companies experiencing a loss bigger than expected tend to engage in big bath accounting via goodwill impairment. In the US, for example Masters-Stout et al. (2008) and Jordan, Clark and Vann (2011) found support for the same pattern, whilst Godfrey and Koh (2009) found the write-offs to not be opportunistically. Giner and Pardo (2015) found support for big bath accounting via goodwill impairment in Spain and Saastamoinen and Pajunen (2016) came to the same conclusion when studying Finnish firms. This all together builds up to our first hypothesis:

H1: Firms with a bigger loss than expected tend to impair more goodwill. 2.9.2 Income Smoothing

Management, as well as stockholders, prefer stable levels of earnings. They do not want net income to fluctuate, instead they want it to increase regularly. When abandoning systematic amortization of goodwill and replacing it with the more irregular impairment testing method, this could result in more irregular levels of earnings. This irregularity can be avoided, when management choose a convenient time to recognize goodwill impairments, and because of that achieve a smoothing of earnings (Jahmani et al., 2010). With this behavior, earnings will be closer to the expected level (Abughazaleh et al., 2011), and the firm will enter next year with better conditions, and lower expectations compared to those that would come from higher earnings than expected (Mohanram, 2003). Lhaopadchan (2010) claims that when looking at asset impairment decision made in an environment where both uncertainty and managerial discretion are present, income smoothing seems to a large extent to be a motivational factor behind those decisions. Acting like this would cover underlying volatility in businesses’ performance.

Abughazaleh et al. (2011) examined UK firms and found evidence supporting managers’ discretionary acting when reporting goodwill impairment losses. They saw a correlation between income smoothing and goodwill impairment. Several researchers have found similar patterns in different countries, Riedl (2004) and Guler (2007) in the US, Giner

19

and Pardo (2015) in Spain and Siggelkow and Zulch (2013) in Germany. All of this leads to our second hypothesis:

H2: Firms with higher earnings than expected tend to impair more goodwill. 2.9.3 Leverage

Managers of firms with a high leverage (debt/equity) are more likely, according to the positive accounting theory, to use income-increasing accounting methods (Watts & Zimmerman, 1990). The higher the leverage, the tighter the firm is to the constraints in an accounting-based debt covenant and a probability of a costly violation of the covenant. By increasing the income through exercising accounting discretion, the manager can relax the constraints and avoid incurring costs (Watts & Zimmerman, 1990). Abughazaleh et al. (2011) adds an another argument to the role of debt, namely that firms with high leverage are more eagerly watched by their debt holders, which would imply a need for discipline regarding goodwill impairments, and less scope for opportunistic behavior. According to Beatty and Weber (2006) it is expected that firms with high leverage are less likely to impair goodwill in order to avoid unnecessary costs. Abughazaleh et al. (2011), decided to examine the correlation, but did not want to predict the direction of it, given the contradictory ideas.

Abughazaleh et al. (2011) and Beatty and Weber (2006) found leverage to be negative and insignificant when examining goodwill impairments in the UK, the US and.

Lapointe-Antunes et al. (2008), Godfrey and Ko (2009), Riedl (2004), Sun (2016) and Zang (2008) found leverage to have a negative significant influence on goodwill impairment when researching firms from Canada and the US, respectively. Gros and Koch (2019) found that German firms with higher leverage tended to opportunistically understate goodwill impairments, according to the authors possibly to avoid breaching of debt covenants.

In contrast to these findings, Malijebtou Hassine and Jilani (2017) found leverage to be positive, but insignificant, in relationship to goodwill impairment.

This summed up, make our third hypothesis:

20

2.9.4 CEO Change

When a firm makes an acquisition, the CEO is seen as the person ultimately responsible for the decision (Malijebtou Hassine & Jilani, 2017). Hence, if it turns out to be a bad decision, if the firm paid too much making the acquisition, or if the expected synergies did not materialize, the CEO responsible risks being associated with this failure. This risk makes CEO hesitant to impair goodwill deriving from acquisitions they are considered responsible for (Lapointe‐Antunes et al., 2008).

When firms change CEO, some take the opportunity to write-off goodwill and record a goodwill impairment loss. Abughazaleh et al. (2011) claim that ”Specifically, goodwill impairments are more likely to be associated with recent CEO changes, income smoothing and ”big bath” reporting behaviors” (p. 165). New CEOs, especially when recruited externally, enter with fresh eyes, and without a baggage of contingent poor acquisition decisions. According to Lapointe-Antunes et al. (2008), there are three possibilities for new CEOs with goodwill impairments. They can use them to “(a) blame predecessors for poor acquisitions; (b) send a signal to investors that bad times are behind the firm and that better times will follow; and (c) protect current and future operating earnings” (Lapointe‐Antunes et al., 2008).

Lapointe-Antunes et al. (2008) found CEO change to have a positive impact on goodwill impairment, meaning that firms that change CEO record higher goodwill impairment losses. (Saastamoinen & Pajunen, 2016) found support for the same direction when looking at Finnish firms. Gros and Koch (2019) found that German firms that changed CEO tended to overstate their goodwill impairments. Similar results were found in France (Malijebtou Hassine & Jilani, 2017) and in the UK (Abughazaleh et al., 2011).

Jordan and Clark (2015) mentions that earlier research to a high extent found support for opportunistic goodwill impairments in the years of CEO change, but that some researchers lately have seen a decline in opportunistic behavior, a more altruistic financial reporting. They saw that goodwill impairments were not recorded opportunistically in the years of CEO change, but instead justified impairments after years of declining operating performance.

21

H4: Firms that experience a CEO change record higher annual goodwill impairment losses.

2.9.5 Hypotheses Summary

To summarize, and to make it easier for the reader to get their head around the core of this thesis, a model (see Figure 1) summarizing the hypotheses/impairment factors, and their supposed impact on the independent variable, is presented below.

H1: Firms with a bigger loss than expected tend to impair more goodwill. H2: Firms with higher earnings than expected tend to impair more goodwill. H3: Firms with higher leverage record lower annual goodwill impairment losses. H4: Firms that experience a CEO change record higher annual goodwill impairment losses.

Figure 1: Impairment factors

Goodwill Impairment I LEV / hypothesis 3 + SMOOTH / hypothesis 2 + BATH / hypothesis 1 CEO Change / hypothesis 4

22

3. Method

_____________________________________________________________________________________ This chapter digs deeper into the methodology of this thesis. It starts with a more theoretical perspective, discussing research approach and strategy. Then the focus shifts to an empirical one, focusing on all the choices made along the process, regarding sample and the data. After that the regression models are presented and explained along with the variables. Lastly, three important criteria used to assess business research is presented and discussed.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

3.1 Research Approach

When conducting business research, there are lots of things to consider and lots of decisions to make. For example, you need to decide on whether to take a qualitative or a quantitative approach. Some suggest that the difference between the two types of research is that quantitative research includes measurements, while the qualitative does not. Others suggest that the distinction is less superficial and has to do with the chosen epistemological approach. Another difference when comparing the two research strategies, is the role of theory in relation to the research conducted. Quantitative research is linked to a deductive approach, which means testing of theories. Qualitative research on the other hand, comes with an inductive approach, which means generating theories (Bryman, 2015)

The most common approach to have for the relationship between theory and research, is the deductive one. The process starts with what is already known in the field, the theory. The theory is later epitomized into one or more hypotheses, which need to be translated into something that can be tested empirically. The concepts of the theory need to be translated into operational terms. Then, the researcher collects data and present the findings. The findings are summed up and compared to the hypotheses in order to confirm or reject them. Lastly, an inductive step is incorporated in the deductive process, when the researcher takes the findings and compare them to the underlying theory to revise it (Bryman, 2015). A summary of the process is seen in figure 2.

23

Figure 2: The deductive process

(Bryman, 2015)

For this thesis, a quantitative research strategy with a deductive approach was deemed the most beneficial, since the purpose was to investigate/measure the relationship between variables and also to start with the theory and then form hypotheses that later were going to be tested and confirmed or rejected. According to Bryman (2015) this also implies a positivist approach, since “the purpose of theory is to generate hypotheses that can be tested and that will allow explanations of laws to be assessed” (p.28).

3.2 Research Strategy

Malijebtou Hassine and Jilani (2017) looked at goodwill impairment losses in relation to earnings management incentives in France during 2006-2012. The authors of this study will examine the same variables during the same time period but in a Swedish context. There are many studies out there focusing on the years right before the IFRS adoption vs the years after, or only the first years after the IFRS adoption. This study covers seven years, giving us a larger sample of firm-years, and maybe a clearer picture.

When searching for articles for this thesis, the main search engines have been PRIMO, the search engine of Jönköping University’s library, and also Google Scholar. As a means to ensure that the sources are of high quality, the authors have used almost exclusively

1. Theory 2. Hypothesis 3. Data collection 4. Findings 5. Hypotheses confirmed or rejected 6. Revision of theory

24

peer-reviewed articles, whereof a vast majority originated from journals listed in the Association of Business Schools Academic Journal Quality Guides, the ABS-list. This list is a ranking system aiming to present the journals of highest quality based on their presumed impact, derived from the number of times their articles are cited by researchers (Bryman, 2011). The authors had in mind that peer-reviews and ranking systems can be a good indicator to whether a journal and its articles are of high quality, but they are never a guarantee, meaning that a critical mindset has been applied when digesting them. In addition to scholarly articles, some newspaper articles have been used, to find some authentic examples and to put the subject in a familiar context.

Regarding the sources, most emphasis have been put on research conducted after the adoption of the new accounting standards, to keep the information up-to-date and relevant for this thesis. These newer sources have been mixed with older ones in some cases, to not miss out on the most influential researchers in the fields.

3.3 Sample and Data

The firms examined are those listed in Large Cap (market cap > 1 billion EUR) and Mid Cap (market cap 150 million to 1 billion EUR) on Nasdaq Stockholm between 2006-2012. For this thesis we chose not to include Small Cap (market cap <150 million EUR) thinking it might be too extensive and after a small test we noticed small cap companies might not have much goodwill to study, possibly because they do not grow as much through acquisitions as larger firms do.

To select the firms making up the sample, we started with those firms listed in Large Cap and Mid Cap at the end of year 2012. The initial number of firms in the sample were 134. Following earlier studies, we excluded the financial industry because of their different reporting processes and regulations which make them less comparable to firms in other industries (Abughazaleh et al., 2011; Malijebtou Hassine & Jilani, 2017; Riedl, 2004; Stenheim & Madsen, 2016). The classification of firms was done in compliance with the Industry Classification Benchmark, ICB. The ICB is divided into 10 industries: Oil & Gas, Basic Materials, Industrials, Consumer Goods, Health Care, Consumer Services, Telecommunications, Utilities, Financials and Technology. Excluding the financial industry meant the exclusion of the following sectors from our sample: banks, real estate, insurance and financial services (FTSE International Limited, 2012).

25

Excluding 30 firms in the financial industry, 8 firms without any goodwill balance, 12 firms for not being listed during the whole period and 14 firms for other reasons (reporting currency other than SEK or missing data), we ended up with 69 firms for our study with 7 years of data, giving us a sample of 483 firm-years.

Table 3: Sample Selection

3.4 Data collection

The financial data is collected from Thomson Reuters database, using Eikon Datastream and hand collected from annual reports. The information about CEO changes of the firm is hand collected from the annual reports and companies’ websites or press releases.

3.5 Model and Variables

Following Guler (2007) and Malijebtou Hassine & Jilani (2017) we will do two regressions; one logistic regression and one tobit regression. The regressions will be run in SPSS, a software used for statistical analysis. Access to the program was provided by Jönköping University.

First, we will examine what factors makes the firm take the decision to do a goodwill impairment. Since the choice to recognize an impairment loss is dichotomous, we will use a logit model (logistic regression).

After the logit model, we will examine the amount of goodwill written-off (in relation to the opening goodwill balance) and study what factors affect that amount. Since firms that experience an economic increase in the value of goodwill are not allowed to recognize the increase, the distribution will be censored at zero. Therefore, we will do a censored regression (Tobit) model (Greene, 2018).

Firms

Initial sample 134

Financial Industry

Without goodwill balance

Not listed during the whole period Other reasons - 30 - 8 - 12 - 14 Final sample 69

26

Logistic regression:

Equation 1: Logistic regression

𝐼𝑀𝑃𝐴𝐼𝑅 = 𝛼 + 𝛽1𝐶𝐸𝑂𝐶𝐻𝐴𝑁𝐺𝐸 + 𝛽2𝐿𝐸𝑉 + 𝛽3𝑆𝑀𝑂𝑂𝑇𝐻 + 𝛽4𝐵𝐴𝑇𝐻

+ 𝛽5𝐺𝑂𝑂𝐷𝑊𝐼𝐿𝐿 + 𝛽6Δ𝑅𝑂𝐴 + 𝛽7Δ𝑆𝐴𝐿𝐸𝑆 + 𝛽8𝑆𝐼𝑍𝐸 + 𝛽9𝑂𝐼𝐿 + 𝛽10𝐵𝐴𝑆𝑀𝐴𝑇 + 𝛽11𝐼𝑁𝐷𝑈𝑆 + 𝛽12𝐶𝐺𝑂𝑂𝐷𝑆 + 𝛽13𝐻𝐸𝐴𝐿𝑇𝐻 + 𝛽14𝐶𝑆𝐸𝑅𝑉 + 𝛽15𝑇𝐸𝐿𝐸𝐶𝑂𝑀 + 𝛽16𝑇𝐸𝐶𝐻 + 𝜀

where the dependent variable is a dichotomous variable and equals 1 if the firm has recognized an impairment loss during the year, 0 otherwise.

Tobit regression:

Equation 2: Tobit regression

𝐺𝑊𝐼𝑀𝑃 = 𝛼 + 𝛽1𝐶𝐸𝑂𝐶𝐻𝐴𝑁𝐺𝐸 + 𝛽2𝐿𝐸𝑉 + 𝛽3𝑆𝑀𝑂𝑂𝑇𝐻 + 𝛽4𝐵𝐴𝑇𝐻

+ 𝛽5𝐺𝑂𝑂𝐷𝑊𝐼𝐿𝐿 + 𝛽6Δ𝑅𝑂𝐴 + 𝛽7Δ𝑆𝐴𝐿𝐸𝑆 + 𝛽8𝑆𝐼𝑍𝐸 + 𝛽9𝑂𝐼𝐿 + 𝛽10𝐵𝐴𝑆𝑀𝐴𝑇 + 𝛽11𝐼𝑁𝐷𝑈𝑆 + 𝛽12𝐶𝐺𝑂𝑂𝐷𝑆 + 𝛽13𝐻𝐸𝐴𝐿𝑇𝐻

+ 𝛽14𝐶𝑆𝐸𝑅𝑉 + 𝛽15𝑇𝐸𝐿𝐸𝐶𝑂𝑀 + 𝛽16𝑇𝐸𝐶𝐻 + 𝜀

where the dependent variable is the amount of goodwill impaired during the year divided by the opening goodwill.

Table 4: Variables

IMPAIR Dichotomous variable. 1 if the firm has recognized an impairment loss during the year, 0 otherwise.

GWIMP The amount of goodwill impaired during the year divided by the opening goodwill.

CEOCHANGE 1 if the firm has changed their CEO in t or t-1. 0 otherwise.

LEV Debt / assets for the firm at t-1

SMOOTH The change in pre write-off earnings from t-1 to t divided by lagged total assets, when it is above the median of non-zero positive values of this variable. 0 otherwise.

27

BATH The change in pre write-off earnings from t-1 to t divided by lagged total assets, when it is below the median of non-zero negative values of this variable. 0 otherwise.

GOODWILL The firm’s opening balance of goodwill divided by lagged total assets.

𝛥ROA The percent change in ROA from t-1 to t.

𝛥SALES The percent change in SALES from t-1 to t.

SIZE The natural logarithm of the firm’s total assets at the end of t-1.

OIL, BASMAT, INDUS, CGOODS, HEALTH, CSERV, TELECOM, TECH,*

Industrial dummies in order to control for industry effects.

*Financial industry is omitted because of their reporting processes and Utility is omitted because of 0 observations.

3.5.1 Dependent variables

When doing two regressions, following Guler (2007) and Malijebtou Hassine & Jilani (2017), we are using two different dependent variables. In the logistic regression model, we are using the dependent variable IMPAIR, which is a dichotomous variable, taking the value of 1 if the firm has recognized an annual goodwill impairment loss during the year of t, otherwise the value 0. In the tobit regression model we are using the dependent variable GWIMP, which is the amount of goodwill impaired (expressed as a positive number) during the year, divided by the opening goodwill balance.

3.5.2 Impairment factors

Several variables from earlier studies (Abughazaleh et al., 2011; Guler, 2007; Malijebtou Hassine & Jilani, 2017; Riedl, 2004) are included as proxies for managers incentives to record goodwill impairments. The first variable, CEOCHANGE, is a dichotomous variable, which takes the value of 1 if the firm has changed their CEO in year t or the year before. Otherwise zero. The information about CEO changes is hand collected from press releases and annual reports. The second variable, LEV, is the firm’s leverage, measured

28

as the firm’s debts divided by total assets for the year of t-1. This is used to proxy for the tightness to the constraints in their debt covenants. The third and fourth variables is the

SMOOTH and BATH variables. These variables are used to test the managers incentives

to recognize a goodwill impairment when the firm’s earnings are unexpected high or low. These values are measured according to Abughazaleh et al. (2011) and Riedl (2004) as the change in pre write-off earnings from t-1 to t divided by lagged total assets. When the value, for SMOOTH, is above the median of non-zero positive values of this variable, that value is recorded. 0 otherwise. When the value, for BATH, is below the median of non-zero negative values of this variable, that value is recorded. 0 otherwise.

3.5.3 Control variables

Similar to previous studies (Abughazaleh et al., 2011; Guler, 2007; Malijebtou Hassine & Jilani, 2017; Riedl, 2004), we are implementing variables to control for the economic environment. The first control variable, GOODWILL, measures the amount of existing goodwill of the total assets, dividing the opening balance of goodwill by the lagged total assets. Firms may record higher goodwill impairment with greater amount of goodwill amongst their assets. The second and third variables, 𝛥ROA and 𝛥SALES, are used as proxy to control for the economic performance change of the firm. 𝛥ROA and 𝛥SALES are measured by the percentage change from t-1 to t. The fourth variable, SIZE, controls for the size of the firm by taking the natural logarithm of the firm’s total assets at the end of t-1. Finally, parallel to Malijebtou Hassine & Jilani (2017), the firms are classified by their INDUSTRY, obtained from the Industry Classification Benchmark (ICB), to control for industry effects.

GOODWILL

We are using the variable GOODWILL as a proxy for the opening balance of goodwill divided by the lagged total assets. Firms with greater amount of goodwill amongst their assets may record higher goodwill impairment because of the relative amount of goodwill is greater (Zang, 2008).

ROA

Return on assets, ROA, is a measure used to measure a firm’s economic performance, comparing its profit for an accounting period as a percentage of the company’s assets (Law, 2016). Riedl (2004) states that “Asset impairments directly affect net income,

29

suggesting explicit and/or implicit incentives may exist for managers to manipulate write-off amounts” (p. 824). For example, they could have bonuses linked to performance goals, as part of their remuneration plan, incentivizing them to reach certain numbers.

According to Lapointe-Antunes et al. (2008) ”Prior research shows firms' financial ratios within the same industry have a tendency to converge at the industry's mean value” (p. 41), meaning managers would tend to make accounting choices steering them close to the industry’s mean value.

Abughazaleh et al. (2011) examined the relationship between a firm’s ROA and its tendency to make goodwill impairments, and found a negative relationship. Firms that have performed poorly in the past recorded greater goodwill impairment losses. This is consistent with the findings of for example Stenheim and Madsen (2016) and Sun (2016). Stenheim and Madsen found that British firms operating in industries with a decreasing return on assets, more often recorded goodwill impairment losses, and also larger ones, compared to firms in other industries. Sun (2016) researched American firms, focusing on managerial ability in relationship to goodwill impairment, and found a negative relationship between return on assets and goodwill impairment.

In contrast to these findings, Verriest and Gaeremynck (2009), when looking at FTSE 300 firms, found that firms which impaired goodwill tended to have higher return on assets, thus a positive relationship.

SALES

Sales growth can be used as a proxy for a firm’s economic performance. Li, Shroff, Venkataraman and Zhang (2011) found that sales growth and goodwill impairment were negatively correlated, when researching US firms.

SIZE

Firm size can be a proxy for various aspects of a firm. For example, large firms generally are involved in more acquisitions and mergers and may have a more complicated structure, affected by frequent acquisitions. Large firms are also generally followed by more analysts, and attract larger public attention, which might decrease incentives to manipulate numbers, or to act opportunistically (Zang, 2008).

Godfrey and Koh (2009) examined the relationship between goodwill impairment and firm size, and found a positive relationship. This is in line with the political cost