master's thesis

Activities and circumstances in business

processes for frequent radical innovation

A comparative analysis of corporations in Sweden

Author: Ivana Lasovan

Examiner: Yvonne Eriksson Supervisor: Erik Lindhult

Mälardalen University Master's Thesis, 30 credits M.Sc. Program in Innovation and Design School of Innovation, Design, and Engineering

Activities and circumstances in business processes for frequent radical innovation

A comparative analysis of corporations in Sweden © Ivana Lasovan

School of Innovation, Design, and Engineering, Mälardalen University

Abstract

Radical innovation is a term with different definitions and divided experiences. From both a theoretical and practical manner, larger organizations seem to perform radical innovation less. This research is further looking into corporation strategies and the dimensions of internal factors of radical innovation. The aim is to find activities and circumstances that can enhance radical innovation and bring more frequent behavior in corporations. The research performs as a comparative study to reveal facilitations and patterns of radical innovation processes in different organizations. This study will compare perspectives of the organizations themselves to both earlier studies and shared insights of an included innovation consultancy firm that is giving their experience on the performance of radical innovation. Likewise, the research will investigate the limitations the organizations find in how and why radical innovations are not as frequent as incremental ones. The outcome of this research is to theoretically provide an alternative approach in the innovation field by researching comparatively. Practically, the research aims to extend knowledge of radical innovation and create a framework that can work as a supportive tool for future business projects and the implementation of more radical innovations.

Acknowledgments

This project has truly been a learning experience and has given me a fantastic opportunity to meet inspiring individuals in the field of innovation. I have learned that curiosity and an open mind can bring exciting discussions throughout the process. I wish to acknowledge that the research would never have been possible without the help of Jan Sandqvist from Googol. Thank you, Jan, for connecting with me and giving valuable suggestions and discussions. Likewise, thank you for trusting in me by sharing your connections. I would also like to give a big thank you to all innovation experts I could meet and speak with during my interviews. Thank you for giving me your time and the will to share your knowledge and experiences. It was truly inspiring for me!

Thanks go to my supervisor Erik Lindhult from Mälardalen University, together with the opponents and reviewers for guiding me with feedback and advice. The effort and time spent have been rewarding, and I am therefore very grateful for everyone around me that supported me in this.

Ivana Lasovan

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 10

1.1

Background ... 10

1.2

Research Context ... 11

1.3

Research Purpose and Question ... 12

1.4

Research Limitations ... 13

1.5

Thesis Outline ... 14

2. Theoretical background ... 16

2.1

Definition of radical innovation ... 16

2.1.1 Disruptive innovation ... 18

2.2

Influences on radical innovation ... 19

2.3

Challenges with radical innovation ... 22

2.4

Support for radical innovation ... 24

2.5

Intrapreneurship ... 26

3. Methodology ... 28

3.1

Research Strategy ... 28

3.2

Research Design ... 29

3.2.1 Sampling Cases ... 303.3

Data Collection ... 32

3.3.1 Primary data collection: Interview ... 32

3.3.2 Interactive data collection: Mind Mapping ... 34

3.4

Data Analysis ... 35

3.5

Research Quality ... 36

4. Empirical findings ... 38

4.1

Definition of radical innovation ... 38

4.1.1 Something totally new ... 38

4.1.2 Value creation ... 39

4.1.3 Change management ... 40

4.1.4 From incremental to radical ... 40

4.1.5 Process innovation ... 41

4.2

Influences on radical innovation ... 41

4.3

Challenges with radical innovation ... 44

4.4

Support for radical innovation ... 46

4.5

Identified themes ... 48

4.6

Perspective from the outside ... 51

5. Discussion ... 54

5.1

Discussion on empirical findings ... 54

5.4

Theoretical and practical implications ... 58

6. Conclusion ... 60

6.1

Proposal for partner ... 60

6.2

Answering the research question ... 62

6.3

Further research ... 63

7. List of Reference ... 64

8. Appendices ... 69

8.1

Appendix A: Interview Framework ... 69

8.2

Appendix B: Data from the workshop with mind mapping ... 69

Table of figures

List of figures

1.1

Figure 01. The research context of this study ... 11

1.2

Figure 02. Categorized definitions of radical innovation ... 19

1.3

Figure 03. Categorized influences on radical innovation ... 22

1.4

Figure 04. Categorized challenging activities and circumstances ... 24

1.5

Figure 05. Categorized supporting activities and circumstances ... 26

1.6

Figure 06. Problem-solution patterns ... 27

1.7

Figure 07. Adapted diamond model ... 28

1.8

Figure 08. Model of involved sampling cases in the research ... 31

1.9

Figure 09. The interview framework ... 33

1.10 Figure 10. The framework of the mind mapping workshop ... 35

1.11 Figure 11. The thematic network of identified themes ... 50

1.12 Figure 12. Framework for increased radical innovation ... 61

……….…………

List of tables

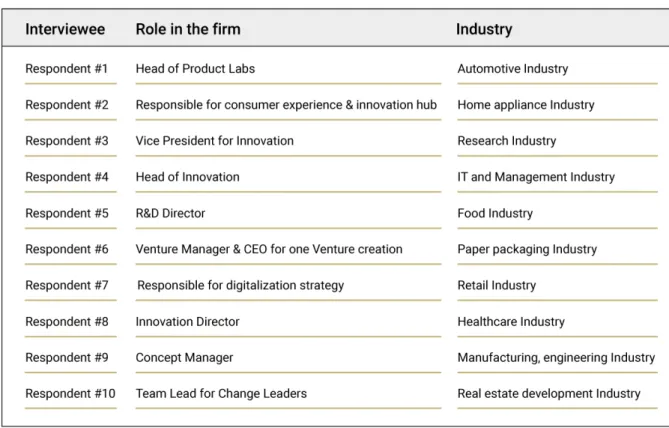

1.13 Table 01. The participating interviewees ... 33

1. Introduction

This research will start with an introductory chapter that will describe the outlines of the subject and the thesis. A description of background, research purpose and question, research limitations, and thesis outlines is taking place for the research idea.

1.1 Background

Initiating a thesis topic within radical innovation involves a discussion on how to define radical innovation and view the subject. Although innovation might be an acknowledged part of a corporation, studies are still researching how further to evolve leadership, creative talents, and unexampled parameters of innovation. Many businesses are today implementing an initiative within innovation or change while operating the daily business (Isaksen and Tidd, 2006). Studying innovation management guidance provided by SIS (Swedish Standards Institute), a recommendation takes a steady balance of different types of innovation into account, for instance, incremental innovation and radical innovation (Ics, 2019). Furthermore, a personal interest in how large organizations are performing radical innovations led me to statements that many large organizations are not good at performing radical innovations (Stringer, 2000). However, as this research from Stringer (2000) is dated, there are still insights to find on how large corporations are managing radical innovation today, and if there are still concerns about why it might not be typical. Why specifically radical innovation is initiated as a research subject is because of its essential role. Bessant (2003) is referring to earlier research on radical innovation as something that could rewrite and turnover a whole industry (Utterback, 1994 in Bessant, 2003). Moreover, in a society with high expectations on organizations in both ethical and environmental questions, originate radical innovation to adapt to societal evolution.

With my academic experience of the innovation field and the curiousness of the radicality within it, I am bringing up a research idea to further look into corporation strategies and the dimensions of internal factors of radical innovation. How to manage radical innovation is not generic, and different constellations are affecting the descriptions of it. However, my attempt to provide recognized activities and circumstances can bring learnings and guidance for directions within the field (Bessant, 2003). Further on, earlier studies are showing that radical innovation is a comprehensive subject with different descriptions of how to interpret it and for whom it might be radical. Referring to Bessant et al. (2014), this research will be from the standpoint of organizations themselves and their perspective on radical innovation. Inspired by the study of Stringer (2000), enhancing radical innovation should be shaped from the inside, the internal environment out to the market. The research is, therefore, searching for insights from the internal adjustments and strategies of an organization. Employing

innovative and creative people is one strategy brought up (Stringer, 2000); thus, operating a business in Sweden, this strategy might not work due to employment regulations.

Nevertheless, strategy recommendations do exist. However, searching through the field of radical innovation, I can conclude that there are divided experiences. Because of divided experiences, this research is aiming for a comparative study to provide a wide range of organizations and industries in Sweden. In the comparative study, each definition and experience can be shared and compared. Likewise, finding a literature gap in terms of comparative innovation processes around radical innovation created a motive to include a methodology with various actors to find possible patterns in different industries and sectors.

1.2 Research Context

A research idea is now defined, and to further understand different positions of radical innovation and how to manage it for corporative innovation, I am initiating a collaboration with an innovation consultancy firm. Googol, as the consultancy firm, has experience in innovation projects with external partners. The firm has exposed a pattern around radical innovation, and the non-frequent behavior corporative innovation has. As a result of these projects, an understanding from Googol is that firms are accomplishing incremental innovations more often than radical ones. Believing that there are reasons and factors for different firms' infrequent behavior has developed a problematization from my research idea that this paper is further investigating. Throughout this collaboration, Googol has shared its network to provide adequate connections with people working with corporative innovation. I created a selection of industries and gathered an assortment of both Googols network and own industry interests to further involvement in the research. Figure 01 is showing each stakeholder by illustrated parts of different positions and perspectives (see Figure 01).

Meanwhile, I raise awareness of this context arrangement as a researcher to this thesis because of the network I am having a part of. The network Googol is sharing might bring specific organizational cultures and structures, and other organizations could work in alternative ways with radical innovation. Likewise, allowing an outside perspective from Googol for data collection can provide gathered experiences from interactions with some involved organizations. However, since I am basing the selection on my interests and a diverse selection of industries, I believe that the critical points of a narrow spectrum can be avoided. Structuring the thesis around corporations creates a collaborative approach because of the vital contribution each stakeholder has. This research will, concerning this context, highlight the importance of co-production to determine the collaboration, different levels of involvement, and possible ethical issues. Taking into account that this research will not only determine the education around this thesis but also the innovation consultancy firm and its development for ongoing work (Öberg Ericson et al., 2018). More in-depth collaboration with Googol will help to create the common ground that is crucial for this research to aim in the expected and agreed direction. A discussion has been held about the knowledge needs and the practical benefits so that value can be shared and brought to the consultancy firm as well as the researcher (Öberg Ericson et al., 2018; Florin and Lindhult, 2015). The value this research will bring to Googol is the gained theoretical knowledge within radical innovation and a created framework to get support from for future business projects.

1.3 Research Purpose and Question

Establishing the introduced research idea is to inquire about new knowledge in radical corporative innovation and acquire an understanding of how large organizations are positioning radical innovation. Since the problem of radical innovation is infrequent and unbalanced in innovation activities, this research aims to reveal facilitations and patterns of radical innovation processes in different organizations and investigate the limitations they find in how and why radical innovations are not as frequent as incremental ones. This problem also turns to the theoretical field, where I argue that conclusions based on comparative analysis are missing. Even with a broad research field of radical innovation, there is a gap in radical corporative innovation and even fewer studies made comparative. As the author of this study, I see potential in studying radical corporative innovation for both theoretical and practical benefits. By guiding the research in providing findings to the problematization of infrequent radical innovation, this study is proposing a research question with two sub-questions. For the outcome to be valid, two sub-questions are needed to support the development of answering the research question.

RQ: Which activities and what circumstances can increase radical corporative innovation in ongoing businesses?

Sub-question 1: How is radical innovation defined in corporations and earlier research? Sub-question 2: Why is the performance of radical innovations not as frequent as incremental ones?

To further explain the research question, I suggest that any ongoing business applies in the ordinary context of a firm. Meanwhile, the increment explains the frequency measurements of radical innovation. Activities and circumstances include any business actions that individuals or organizations are engaging in to perform radical innovation. Circumstances in the organizations are conditions or attributes that can be relevant for radical innovation to take place.

In exploring the problematization, there are enhanced possibilities to reveal suitable activities and circumstances for radical innovation processes. This exploration comes by studying theory together with empirical data on why the radical processes in organizations are less distinctive. Likewise, by answering the research question, a created framework based on comparative analysis can discover and avow a contribution to the field. Theoretically, this study builds upon the field of radical corporative innovation and contributes to a comparative aspect from different industries to the innovation field in Sweden. Practically, it indicates what relevant elements to concentrate on when organizations and Googol are aiming for more radical innovation within their business. Initiating a thesis topic from a field perspective and combining it with the gap-spotting of a comparative methodology is needed to provide a pattern from different industries. Several organizations are involved in minimizing the risk of individual experiences from specific cases that could bring less relatedness. With the involvement of different actors, the research idea will include, as Alvesson and Sandberg (2011) put it, "diverse opinions and incoherent results" (Alvesson and Sandberg, 2011).

1.4 Research Limitations

Narrow down and defining radical innovation in this study is required in terms of the outcome of it and whom it will affect. Finding the subject wide creates a framework that provides different research limitations. This research will, as presented in the introduction, give a perspective on radical innovation from each organization and, therefore, view it from their standpoints (Bessant et al., 2014). Furthermore, focus on radical innovation is likewise from the perspective of internal structures of organizations. Thus, a research limitation will, therefore, be not to consider external effects outside the organization, such as the industry and market context, nor how collaborators, partners, users, or customers are perceiving the radical innovation.

Another limitation is in the selection of sampling cases that one upcoming section is describing more carefully. Sweden will be the geographical choice and implies the restriction of possible business cultures and hierarchies. This research will also not look into start-up firms, smaller businesses, or firms not having roles or structures interpreted for innovation. The limitation also includes unicorn companies because of my perception of them coming from the start-up environment and very likely do not have a sufficient history background. Following the choice of sampling cases, most participants have been having a business relationship with the innovation consultancy firm, the partner of this study. While considering the internal processes of organizations, necessary restrictions could be the definitions and views each sampling case has on radical innovation where the researcher's interpretation should be understood for the data to be relevant. Although this research is interesting, it does not allow for extensive data collection due to the time frame and amount of work for a master thesis. Giving it a clear direction in the possibilities to conclude on general findings would require a lot more organizations involved than planned. Despite its shortcomings, the assemblage of participating organizations can still bring interesting insight in the required manner.

1.5 Thesis Outline

Starting this thesis with an identified research idea has built up an outline that will guide this research in the right direction. The research idea develops into a problematization with a related research question. An inductive research process of descriptive themes, concepts, and theories is framing the research question (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016). Firstly, the inductive study is starting with the development of a theoretical background for the aim of comparing it with the empirical study. The methodology chapter will describe the research strategy and design for the execution of the empirical study of data collection and analysis. Within the methodology chapter, the empirical study is compiling cases. Finally, conclusions and reflections of the thesis work are stated and discussed. The thesis work will reveal different activities and circumstances that will be highlighted and suggested in frameworks to provide an understanding of different contexts that organizations have around radical innovations. Practically, I am indicating what relevant activities or circumstances to concentrate on when organizations are aiming for more radical innovation within their business.

2. Theoretical background

This section will give an overview of the theoretical background of this research by dividing it into definitions, influences, challenges, and support for radical innovation. The chapter is finishing off with Intrapreneurship that is also a represented concept for radical corporative innovation.

The research question is guiding the literature review, where earlier studies might indicate different strategies of what circumstances or activities could increase radical innovation in businesses. Likewise, allowing this research to imply a focus on radical innovation demands a variety of what is understood by the concept. Throughout the written work, I have focused on research within business and management studies, social change, technovation (technology innovation), and design studies. All studied articles have had a topic around radical innovation to include diverse research and different perspectives to bring a pronounced and equal understanding of today's research in radical innovation. Kasmire et al. (2012) describe radical innovation as a subjective judgment, so because of the belief in subjective judgment, this theory building is trying to collect the focal points and diverse definitions and create a theoretical background out of them. Providing diverse definitions is criteria for the selection as well as being open to influences from the empirical investigation that might bring new insights on what theories and literature to search for. The structure is first to map the definitions of radical innovation and, after that, look at influences and challenges with radical innovation. The paper also brings up highlighted tools or methods as support for radical innovation. I am also including research from related areas, such as intrapreneurship, that are focusing on radical innovation.

2.1 Definition of radical innovation

A vital issue with much of earlier research regarding defining radical innovation is that the definitions are widely spread. Some aspects associate radical innovation to the creation of new offerings (O'Connor and McDermott, 2004), not yet established behaviors (Suri, 2008) and new knowledge (Sheng and Chien, 2016a). These novelties can touch both processes and products or services and influence the firm itself and the market (O'Connor and McDermott, 2004).

Yamamoto (2017) presents radical innovation in Japan as Kaikaku, which includes large-scale changes or initiatives that can involve a whole company. Kaikaku can change technical and social systems, management processes, strategies, and cultures of different groups, divisions, or departments in an organization, often with a drive from strong leadership (Yamamoto, 2017).

Kasmire et al. (2012) would describe radical innovation as a high degree of novelty. Because of the difficulties in categorizing novelty, Bessant et al. (2014) argue that the innovator is determining the level of novelty and how radical it is from the organizations' standpoint. Contrary, Story et al. (2014) research maintains that radical innovation is equal to processes, indicating that it is dependent on the size of firm and development processes rather than novelty.

Other studies would seem to suggest that managing radical innovation consists of explorative activities, that believe in bringing higher levels of uncertainty because of the risks that are built when new knowledge and behaviors are involved (Bessant et al., 2014). Because of this higher level of uncertainty, a possible description of radical innovation could be a discovery process without the inclusion of full understanding (Story et al., 2014). By reading Hopp et al. (2018) and Stringer (2000), radical innovation might extend and impact over a long time by different internal progressions, often technological ones, while Egfjord and Sund (2020) would describe that it is about business model innovation.

Similarly, considering that radical innovation creates new frameworks and structures have interpreted that the organizational workflow and routines could get affected (Bessant et al., 2014; Green and Cluley, 2014) because of discontinuity. However, different circumstances are defined liable to what size the organization has, as well as the type of it connected to established routines, structures, and methods (Bessant et al., 2014; Story et al., 2014). Meanwhile, a distinctive definition of radical innovation is in the creation of new meanings to existing solutions (Verganti and Öberg, 2013). Radical can be new meanings as well, context-dependent in why we do something in a certain way (Verganti and Öberg, 2013). Reframing seems to be a typical process for the consideration radical innovation requires. To be able to reframe, the organization needs to look at where they are placing themselves cognitively and apply activities in the innovation process that goes beyond the cognitive framework to aim for radical innovation (Bessant et al., 2014). To put it briefly, providing an internal position of radical innovation creates focal aspects of what is being affected in organizations. Radical innovation is from this research position affecting what Hopp et al. (2018) are referring as internal parameters of organizational capabilities, culture, structures, resources and project management (Hopp et al., 2018) and likewise driven by the employees and their knowledge, skills, and abilities (Doran and Ryan, 2014). A sequence to this in how to radical innovation can succeed is when a systematical process - that can initiate, support, and reward the activities - has been implemented (O'Connor and McDermott, 2004).

Sheng and Chien (2016) are in their research, exploring how organizational learning orientation can relate to radical innovation. They present potential and realized absorptive capacity that is affecting radical innovation to firms’ ability to recognize new knowledge, value,

and discoveries (Sheng and Chien, 2016b). Argumentation lies in how realized absorptive capacity, as a transformation capability, can combine existing and new knowledge and incorporate it in the business as well as how they assimilate and acquisitions new external knowledge (Sheng and Chien, 2016b). Knowledge management includes not only to integrate knowledge but also recognizing risks of both knowledge sharing and knowledge protection (Czakon et al., 2020).

2.1.1 Disruptive innovation

Disruptive innovation is a term that often associates with radical innovation. Addressing an innovation disruptive and radical can be a possible reason why the definition is hard to grasp. Disruptive innovation can synonymously change or disrupt an organization, with technology as an example (Nagy et al., 2016). Because of its uncertainty in what each researcher tends to name their innovation studies, I decided to also include disruptive innovation in the theoretical background. Moreover, studies show that disruptive innovation has influences from internal perspectives as well. The disruptive innovation is changing functionality, technical standards, or ownerships (Thomond and Lettice, 2002 in Nagy et al., 2016), and Nagy et al. (2016) are arguing with affected organizational structures and contexts because of the process of disruption. Studies of disruptive innovation are likewise subjective in terms of how disruptive innovation is for the recipient. By the mentioned functionality, technical standards, and ownerships, an identification of the disruptiveness can be made more easily (Nagy et al., 2016). Having a radical or disruptive innovation identified and by looking at the three factors of it, can help to understand what part of the organization that will be affected by it (Nagy et al., 2016).

"Finally, understanding how the characteristics of the new technology, or the potentially disruptive technology, align relative to existing technologies used by the organization should provide some understanding about how potentially disruptive an innovation might be to the organization." (Nagy et al., 2016)

The above citation can give an indication and a better understanding of the radicalness provided in an organization. Technology might be one radical or disruptive innovation but could likewise be a new process or business strategy that is unfamiliar to the organization. Giving this study as a final example of how radical innovation can be defined, coincides with the earlier mentioned understanding of personal situations. However, with only one reference on disruptive innovation, there might be a distinct association that disruptive innovation is mainly towards the market and external effects.

A general critique of literature is in how each researcher explains their definitions. Gunday et al. (2011) bring up a different perspective on types of innovation and are not determining in what outcome it gives: product innovation, process innovation, marketing innovation, and organizational innovation. As the author of this thesis, I reflect that radical innovation would accommodate any of the definitions. The critique applies to the uncertainty in where to apply the context of the mentioned radical innovation. I believe that some of the researchers (O'Connor and McDermott, 2004; Verganti and Öberg, 2013) argue for product innovation. Some (Bessant et al., 2014; Green and Cluley, 2014; Nagy et al., 2016; O'Connor and McDermott, 2004; Story et al., 2014; Suri, 2008) argue for process innovation while others (Egfjord and Sund, 2020; Hopp et al., 2018; Bessant et al., 2014) relate radical innovation to organizational innovation. Marketing innovation, like product innovation, is, from my perspective, towards the market. When connecting the placement or application of radical innovation, it could give more clarity to target each radical innovation.

Meanwhile, applying my interpretations of categorized definitions in a visual figure might assist in understanding different contexts (see Figure 02).

Figure 02. Categorized definitions of radical innovation*. Illustration by Ivana Lasovan.

* This illustration shows categories of definitions for radical innovation. The parameters are not indicating any order or timeline.

2.2 Influences on radical innovation

According to Green and Cluley (2014, p.1346), aspects as organizational culture, management, and human resources have been mentioned as effects and consequences of radical innovation in an organization to "maintain some element of the original, open, organic culture within the new premises." By looking at an organic organization, radical innovation needs support and redesign of structures with no constraints (Green and Cluley, 2014). Depending

on the size of the organization, different forms of flexible and informal structures are necessary for radical innovation, for instance, new recruitment and various software's and systems (Green and Cluley, 2014) as well as an iterative and non-linear process with much learning and communication (Van Lancker et al., 2016). The opposite direction of structures is to look at it as supportive infrastructures that are integrated into organizations in terms of coaching and structuring when individuals are engaging in radical innovations (O'Connor and McDermott, 2004).

Meanwhile, decisions around how to foster radical innovation in the organization could bring more enthusiasm and confidence by bringing up how Suri (2008) would specify, "frameworks, principles, goals, criteria and priorities" in a collective manner of different teams. The argument consolidates with the theory of Green and Cluley (2014) that radical innovation might influence the organization in the way of those affected by it.

Managing the processes in a radical context is for Bessant et al. (2014) about establishing structures and routines while being able to experiment in analog conditions. A parallel internal field of radical innovation seems to depend on the organizational culture rather than the structures. Individuals feel that social change and personal independence are related to the dispositions of radical innovation (Green and Cluley, 2014) in the way that adopting their attitude goes into the setting of the activities. Understanding it as a process or activity creates a conditional frame of involved people, specified by Suri (2008) as both socially and emotionally. Story et al. (2014) agree on the emotional influence of radical innovation and clarify it as a commitment that needs to be in place.

Stringer (2000) brings up the opposite, believing that entrepreneurs are motivated to create radical innovations, placing their needs in a corporative environment might need additional factors for a successful implementation. Those are: 1. feedback that is tangible, concrete and measurable is required, acting for a contribution to the work, 2. competition internally around the standards and 3. act risky are just fundamental factors that an entrepreneurial behavior would perform at the organization, however with additional strategies to receive the radical innovation (Stringer, 2000).

Within the organizational culture, Baumard (2014) raises the context of facades that are used as cognitive tools when starting the process of radical innovation. These facades are used as illusions or frames for trust to explain the radical innovation with a purpose to prepare people for the effects and increase the commitments and perceptions while "reducing resistance" when implementation takes place (Baumard, 2014). Despite that the steering of the study of facades was towards the market, an internal focus could provide expectations by a

conversation platform among individuals and teams. Attitudes will predict behaviors (Czakon et al., 2020).

With a connection to the cognitive frame of behaviors, a study has been considering the possibilities of placing design research in the development of radical innovation by looking at patterns in motivations, impressions, intuitive interpretation and behaviors (Suri, 2008), reasonably because of the abilities to both experience and interpret how the future might be.

However, skills are required when implementing design research. Individual skills are significant impacts on how an organization will perform around radical innovation (Doran and Ryan, 2014; O'Connor and McDermott, 2004). Involving different roles and competencies are very dependent on how the role functions are connected. O'Connor and McDermott (2004) explain that if the idea generators and opportunity recognizer for radical innovation had been two different individuals, they would need an active role in understanding and learning from one another. An interesting aspect connected to this is in the cross-functionality demand of teams. However, in the same research, all team members had, instead, substantial knowledge and understanding of several fields as being cross-functional individuals (O'Connor and McDermott, 2004). Toner (2011) implicates that core competencies for radical innovations are internally within sourcing scientific and engineering with a mix of design competences in product or service. Suri (2008) agrees that design skills in especially research, are required to optimize the process of radical innovation. Doran and Ryan (2014) believe, however, that both internal and external skills will affect innovative actions and change depending on what type of development is supposed to take place.

Furthermore, different skills are of matter depending on the type of innovation, and both external and internal networks can bring complemental opportunities (O'Connor and McDermott, 2004). Regardless of the inhouse or outsourced competence, Story et al. (2011) believe that a significant component to radical innovation is the interaction and collaboration between divisions and different functions.

Sheng and Chien (2016, p.2303), however, believe that "the more new external knowledge is, the more likely the firm achieves radical innovation" because of the diversity the new knowledge can bring. Similarly, Kobarg et al. (2019) indicate that bigger collaborative breadth could bring more exceptional radical innovations on a project level and that external collaboration does not necessarily have to have deep interactions for radical innovation performance.

Jones et al. (2016), on the other hand, are pointing out that innovation management is taking a big role in how the organization will evolve and meet challenges that are synonymous with

skills on how to innovate radically. To further challenge radical innovation management with a why rather than a what or how, Verganti and Öberg (2013) are in their research suggesting a process away from problem-solving and ideation and instead create a process of interpretation and envision to expose different meanings of a process, product or service. By doing this, a focus can be put on interaction to experience a social dimension of radical innovation (Verganti and Öberg, 2013).

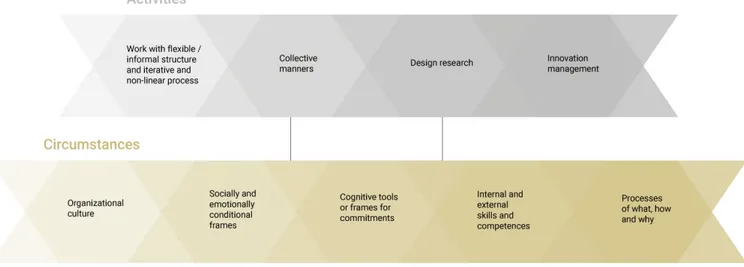

Figure 03. Categorized influences on radical innovation*. Illustration by Ivana Lasovan.

* This illustration shows parameters of different activities and circumstances that can appear in radical innovation. The parameters are not indicating any order, timeline, or particular process.

Many of the researchers have expressed different opinions on activities or circumstances that would influence radical innovation. Some of the mentioned studies have tested their frameworks or conceptual models to prove their hypothesis. Van Lancker et al. (2016) argue that much literature is focusing on specific phases of an innovation process but meanwhile suggesting that their study will include conclusions from earlier research, which seems to be a reliable approach. Providing different outcomes of earlier studies will contribute to a useful framework. Figure 03 is showing all parameters compared in this section of influences on radical innovation positively (see Figure 03).

2.3 Challenges with radical innovation

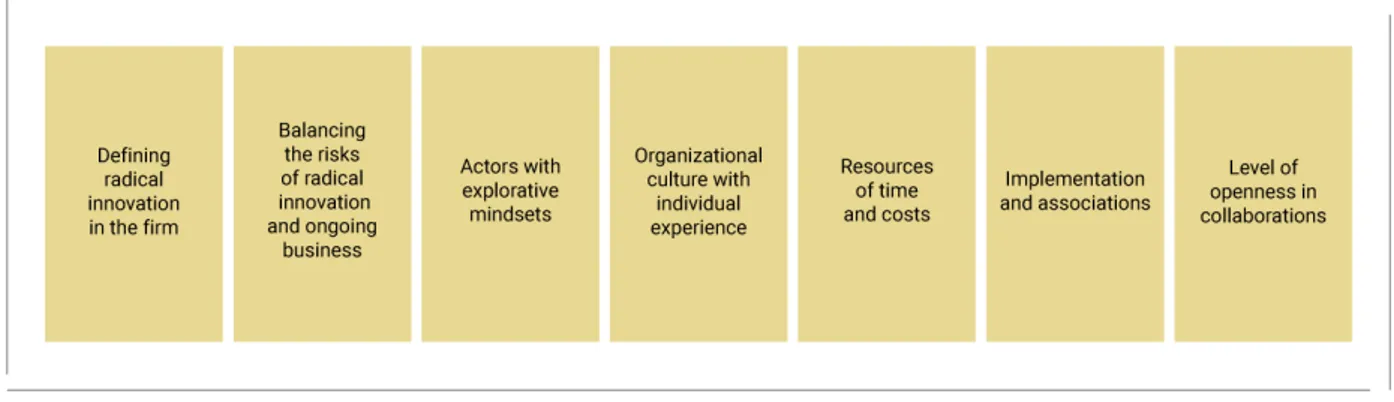

Provided that radical innovation can bring risks, some challenges might occur. Bessant (2003) included his research with a paper on challenges for innovation management and highlighted eight general challenges. This approach might have a limitation in the setup because the challenges argued to be for all types of innovation. I suggest that some challenges were specifically appropriate for radical innovation because of mentioned arguments: 1. balancing

the changes to possibly make, in an attempt to avoid ending up without any radical innovations, 2. defining radical innovation within the organization so that all understand it and can relate and determine a meaning to it, 3. create a shared external network for learning and development and the last challenge, 4. the ability to be discontinuous parallel with structured frameworks for incremental innovation, not to risk the failure of the radical innovation not taking place or an employee starting own business outside the organization (Bessant, 2003).

Story et al. (2014) point out the challenges radical innovation can bring in terms of barriers and consequences. There is, however, considerable uncertainty concerning the summarizing issues brought up by the authors for competitive research. Still, Story et al. (2014) point out collected papers with recognized key issues. Typically identified factors are the reactions of people and changes in practice for internal processes (Story et al., 2014). In other words, with new strategies and cognitive frameworks, it may involve a challenge to manage the discontinuities that emerge with the change (Story et al., 2014). This conclusion seems to be well-grounded because of the selection of being one out of twelve articles for a special issue. For the progression of understanding barriers, this study has included Green and Cluley (2014). The researchers have, in their paper, focused on organizational cultures. They claim that individual experiences of organizational changes are primarily driving interpretations of radical innovation, hence connected to "anxiety about organizational change and nostalgia for past time" (Green and Cluley, 2014, p.1347). Together with that, staff with long experience in the organization might give the consequence of disapproval (Green and Cluley, 2014). Their study is yet based on an organic organization with directions to develop systems and structures. It might have been more useful if the organization had the opposite direction in becoming more organic.

Radical innovation is advocating the explorative mindset, which can also create a barrier in the strategies and well-established knowledge each organization has (Sheng and Chien, 2016a). Sheng and Chien (2016) argue that the actors that can make the organization more radical require that the organization is capable of acknowledging the value of new frameworks, such as strategy and knowledge. Thus, connecting to the idea that affected stakeholders need to be convinced by the innovators (Story et al., 2014) or when managers are proposing a radical vision for a business model innovation to others in the organization (Egfjord and Sund, 2020).

Resources could be a challenge for firms likewise (Story et al., 2014), in the time and costs that most likely will occur. Even though a new value proposition can emerge by implementing new technology, larger corporations feel that the cost will be too much for changes that might not distribute the resources or effects fast enough (Stringer, 2000). Focus on incremental

innovation, and improvements to existing technologies are preferred (Stringer, 2000). Implementation as an ensuing part of earlier mentioned factors in radical innovation is another challenging part. Bessant et al. (2014) underline that there is a need for new associations and linkages for the team that it will impinge upon.

By looking at the collaborative aspect of radical innovation, the level of openness each organization feels confident with is a recognized challenge. Having different stages in the development of radical innovation allows having some phases open and some closed (Bahemia et al., 2018). Having in mind that the research only included one case study, a conclusion is hard to define. However, the findings can interpret that being open is of value but with a strategy on when and how to put it in place, because of sensitivity, misunderstandings, and patents (Bahemia et al., 2018).

Figure 04. Categorized challenging activities and circumstances*. Illustration by Ivana Lasovan.

* This illustration shows challenging categories for radical innovation. The categories are not indicating any order, levels, or a particular process.

Figure 04 summarizes the categories that have been raised and defined in the discussed papers (see Figure 04). The main shortfalls of the papers are the methods with studied cases that might have challenges due to individual experiences in a current situation. Meanwhile, categorized challenges showed in the figure seem to be reliable aspects because of the extension they provide of being mentioned in many of the articles.

2.4 Support for radical innovation

Doing a limitation to exclude start-ups in this research has made remarkable differences in how large corporations are performing radical innovation. Associating the environment of large, established organizations can enforce frustrations in terms of possible hierarchical and bureaucratic processes, decision makings, and mindsets (O'Connor and McDermott, 2004). In an opposing direction, these large corporations have more abundant possibilities to enhance capabilities, rich networks, and resources that are most likely to be needed in radical

innovation (O'Connor and McDermott, 2004). Creating networks outside partners, customers, and the current industry into unfamiliar connections is a tool that can enhance the process of radical innovations (O'Connor and McDermott, 2004).

Open innovation is synonymous with a knowledge-based platform of activities and interactions going outside of a firm (Cheng et al., 2016). External input is support to include and facilitate new knowledge and information to the business to bring potential change (Cheng et al., 2016). Cheng et al. (2016) refers to this knowledge as either acquisitive or shared capabilities and are necessities for open innovation. The facilitation of new knowledge and capabilities can be both exploratory and exploitative learning (Cheng et al., 2016), where a factor for enhancing radical innovation is exploration.

Besides, taking possession of or maintain radical innovation can be accomplished with different labs. They are to be used for research and deliberately understand needs internally or in the market (Bessant et al., 2014). Realized absorptive capacity is another method that could measure radical innovation possibilities in a firm because of the capability it has on transforming knowledge and deepen the processes for new insights (Sheng and Chien, 2016a). Integrating design tools to existing strategy processes could be another way to discover new opportunities for innovation and help traditional organizations with design and imagination (Liedtka and Ogilvie, 2011).

By increasing radical innovation, there have been examples of methods, tools, or support in terms of documentation or focal meeting points. Significant documentation that utilizes and supports corporative innovation is an ISO standard from the Swedish Standards Institute (SIS). As a non-profit organization, SIS supports organizations by giving them documented knowledge in innovation management. However, this type of documentation does not prove the utilization of it but could, likewise, be the missing guiding point for organizations.

Figure 05 provides a visual overview of identified activities or circumstances that can work as support during processes of radical innovation.

Figure 05. Categorized supporting activities and circumstances*. Illustration by Ivana Lasovan.

* This illustration shows supporting parameters for radical innovation. The parameters are not indicating any order, levels, or a particular process.

2.5 Intrapreneurship

Both theoretical and practical aspects bring up entrepreneurial skills in corporations for the generation of new ideas. Providing venture creation, new brand management, or intrapreneurship is a way to facilitate new ideas and is, therefore, a part of the theoretical background. Van Rensburg (2014) believes that intrapreneurship can be a complement to traditional brand management structures, where disruptive innovation otherwise only happens during good financial premises. Large firms have to give, what Van Rensburg (2014, p.29) is describing, “internal efforts with strategic inter-organizational arrangements and/or intrapreneurial efforts” to accomplish growth. Van Rensburg's (2014) understanding of intrapreneurship is when corporations use entrepreneurial approaches to develop new brands internally. The same research brings up a vital contribution aspect of practical examples; commitment and willingness from leaders and the CEO to ensure time, strategy, process, and resources of people and capital (Van Rensburg, 2014).

Fostering exploratory activities and radical innovation within an organization is by Knote and Blohm (2016) presented in a structure of an Intrapreneur Accelerator to what they explain will unleash the innovative potential of intrapreneurs. Knote and Blohm (2016) explain that their Intrapreneur Accelerator function as a service system that can help organizations to foster explorative innovation. Reading some literature during this thesis gives the ability to estimate this study as well-constructed and performed. The study introduces four project

Intrapreneur services, 3. Service modularization, and 4. Service system implementation (Knote and Blohm, 2016). Within the iterations, the researchers could reveal activities, circumstances, and challenges that innovators experience in their organization. Flexibility is an effect that needs evaluation in terms of how management encourages mistakes and not perfect solutions (Knote and Blohm, 2016). The flexibility also shows how the organization manages budgets, support processes, and the phase of testing the ideas (Knote and Blohm, 2016). The next challenges are networking, customer integration, and speed. Knote and Blohm (2016) find in their research that networking within an organization lacks because of top-down approaches, while customer integration is missing in innovation activities because innovation was often technology-driven.

In Figure 06, Knote and Blohm (2016) gather six patterns from their data collection (see Figure 06). These six patterns show goal descriptions that can go from promoting an idea or intrapreneur to transferring it to a business model that suits an operating structure (Knote and Blohm, 2016). At last, intrapreneurship is heavily dependent on both the organization’s innovation capabilities but, most importantly, “employees’ individual attitude towards innovation and willingness to change” (Knote and Blohm, 2016, p.5)

Figure 06. Problem-solution patterns. Illustration by Ivana Lasovan with content from (Knote and Blohm, 2016).

Enhancing intrapreneurship in large organizations is because of the possibility to successfully implement an innovation project to the business (Cubero and Consolacion Segura, 2019). Even though intrapreneurship gives the impression of being an obvious choice to invest in, Cubero and Consolacion Segura (2019) point out that corporate venture can bring the risk of acting as a competitor or threat to the established business. The importance of this research is to make the innovation go from corporate venture to a business unit.

Intrapreneurship involves suitable theories for radical innovation, indeed. It brings an important dimension, but as this study has limited focus, I suggest further studies for in-depth research within the field of intrapreneurship.

3. Methodology

This section will give an overview of the framework around the methodology of this research regarding strategy, design, and data. A description presents the organizations that are relevant for this research and the researcher’s position towards the organizations.

3.1 Research Strategy

Viewing this thesis as collaborative work is inspired by the research model of engaged scholarship, meaning that others' interpretations are of importance to increase new knowledge (Van de Ven, 2007). Several steps are included and inspired by the engaged scholarship diamond model (see Figure 07) Van de Ven (2007) has created, to fulfill this research in the sense of social science and practice. A first step connected to the research strategy is the research problematization, which has been brought up in the introduction section to formulate the problem and get an understanding of the problem and experience, mainly by Googol as an innovation consultancy firm facing the challenge. Building theory around the problematization is as well part of the research strategy, in both studying literature and previous learnings, as well as the data collection of sampling cases. The research design of sampling cases is one of the four foundations to unify the thesis work and provide findings and a problem-solving outcome.

Figure 07. Adapted diamond model. Illustration by Ivana Lasovan with inspiration from (Van de Ven, 2007)

The researcher is interacting and iterating with all parts to maintain a comparison in how theory and the firms will describe the performance of radical innovation. Moreover, what conclusions to draw from the findings. With the evident phases of research strategy, an iterative process is needed as well, for the ability to maintain the purpose of this thesis

throughout interactions with the participating sampling cases. New knowledge will come when interacting, and the strategy of allowing iteration will support the process to be dynamic.

A philosophical perspective of the research strategy is to include pragmatism. In this study, pragmatism will follow the theory of meaning. Van de Ven (2007, p.54) explains that a theory of meaning is “where ideas can be clarified by revealing their relationship with action.” My attempt to include the philosophical perspective of pragmatism will mostly influence the research design and the findings, in how the meanings are conclusions of actions. Both in how repeatable the actions are also in the situations and contexts they appear (Van de Ven, 2007). Viewing this research with influences from pragmatism helps in the process of collaboration, where all actors contribute to this research by revealing their ideas of radical innovation and their relationship with actions. A pragmatic strategy will, by these interactions, observations and conversations emerge meanings (Saunders et al., 2009). An additional proposal of pragmatism is to use it when the aim is to make a difference in organizational practice (Saunders et al., 2009). Saunders et al. (2009) point out that pragmatism is oriented towards practical outcomes because there is no one way of interpreting situations. By collecting theories, concepts, and ideas in what roles and consequences they have in the research context and practical context, practical effects on action take place (Saunders et al., 2009). However, in this strategy, there should be an interpretative mindset to be able to distinct all sampling cases and understand all revealed meanings. By complementing an approach of interpretivism, the research will easier provide conclusions from the researcher’s interpretations. As with pragmatism, interpretivism believes in multiple meanings and realities (Saunders et al., 2009). The discovered meanings from the pragmatic strategy will, with interpretivism, study the meanings. By studying different organizations and interacting with different people, I, as a researcher, need to understand the complexity of their meanings and experiences. Bryman (2012) believes that an interpretative mindset can provide surprising findings by positioning oneself outside of the studied contexts. The pragmatic perspective will help to include all actors and their understandings of radical innovation; meanwhile, the interpretative mindset will help in the process of comparison, analysis, reflection, and conclusion.

3.2 Research Design

Designing this study has been considered to support the research question by identifying the collected findings. A research design will help to conceptualize data that can answer the research question and operationalize the data collection that can provide the data (Lune and Berg, 2017). Likewise, the research design will help in participant collaboration of the research

context. Considerations of each stage of the research design are required to decide upon the execution of data-collection strategies and data analysis and the importance of reflecting on possible ethical issues (Lune and Berg, 2017).

A comparative approach will give the ability to get an unbiased understanding of radical corporative innovation. By having a comparative design of different contrasting situations, there will be a better understanding of social phenomena (Bryman, 2012). In this research design, ten comparative organizations will take part in the same data collection strategy. Bryman (2012) explains the comparison from cross-cultural or cross-national research where issues or phenomena are analyzed by the same research strategies and provide comparative data to explain similarities and differences for deep understanding. However, in this comparative approach, the research design is built upon the context of cross-cultural research but with business-related factors of industry, the form of ownership, strategies, processes, culture, and patterns.

Hence, doing research focusing on a comparative approach, and the interactions for new knowledge is creating an association with design studies. Cross (2006) has, in his studies, raised design research of being based on people and how they design as a natural human ability. This study will evolve the standing point of looking at people and, in this case, on how they innovate. Cross (2006) interprets design research based on three areas: human ability and how people design, the processes, and products. Guided by the research question of understanding activities and circumstances for enhanced radical innovation, the research design will focus on the first two areas, the people and the processes in bearing with radical innovation. Allowing myself to be critical to the arguments of Cross, the people have likewise designed the processes; however, with an understanding that a different constellation could construct the practices. Cross (2006) suggests following the study of designerly ways of knowing and the study of the practices and processes of design. This research is modifying the recommendation in the way that it will do a study of innovational ways of knowing and study of the practices and processes of radical innovation. Allowing this orientation in social science will elaborate in terms of how to orient the research design around it. Moreover, Cross’s (2006) idea of design research can help to focus on what elements to search for to answer the research question (s).

3.2.1 Sampling Cases

Sampling organizations in different cases have been a part of the research design to understand different processes of radical innovation. Managing radical innovation and finding factors for change calls for an understanding of organizations and their functions (Isaksen and Tidd, 2006), which is why this thesis is involving a methodology of different organizations.

Due to the comparative aim this research has, different industries will have one representative organization from each sector. The selection initiates on providing a wide range of industries and organizations for the possibilities to get different views and routines around radical innovation. Providing the possibility of receiving different experiences from firms, each one of them would also be able to supply their view in experiences of their field and industry. Understanding the process and steps for radical innovation to occur at enterprises, creates an opportunity to inquire about which factors it takes for frequent radical innovations in businesses. A total amount of 10 firms has been included in this research and given their aspects and experiences on radical innovation (see Figure 08). All organizations are either product-oriented or service-oriented, with an ability to enhance their innovation journeys mainly internally. The selected companies are all primarily having internal departments where innovation, product development, or business development are active. The involved function and role in each company have to be someone with innovation encourage in their role description. The next section will describe the positions in detail.

Figure 08. Model of involved sampling cases in the research. Illustration by Ivana Lasovan. Collaborating with external organizations in this research induces a discussion about the position of the researcher and the practiced norms and ethics during interactions. Bringing in all parties with different knowledge and contribution requires an agreement on how the beneficial and confidential arrangement will take place (Florin and Lindhult, 2015). All organizations involved in this study are privileged to remain anonymous to share the internal and strategic processes of their corporation. However, with different openness to the actual names, this study will only mention the industry and position of the respondent. Further consideration will take place for the importance of how much information the participants want to share.

Throughout the process, the researcher will lead the study and arrange different activities. However, when it comes to the interactions, an understanding and open discussion with a democratic dialogue is of matter (Florin and Lindhult, 2015). One of the prerequisites (Florin and Lindhult, 2015) for ethics and norms is self-reflection that this study is highlighting. Encouraging the participants to be critical and self-reflected around their experiences can be conducive to transparency (Florin and Lindhult, 2015).

3.3 Data Collection

Given that this research is not executed within an organization to manage internal change, applying methods for data collection need to help to extend the knowledge of the phenomenon from others' perspectives (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016). Likewise, with a research strategy in the diamond model and pragmatism followed by comparative research design with influences from design research, the data collection requires methods that can support a deeper understanding of contexts and understanding. Moreover, the methods will give an understanding of how firms "make sense of their experiences" (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016, p.42) and give the possibility to apply the theoretical background of the subject practically from the knowledge and experiences of the involved organizations (Öberg Ericson et al., 2018). Conducting data in a qualitative approach (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016, p.42) can help to understand the context of radical innovation. Guided by the research question of which activities and circumstances that can enhance radical innovation, qualitative methods will support the framework of practice-based challenges on strategic and operational levels. With the risk of being very subjective in a qualitative study, the data collection is including all sampling cases, which is suiting a study that can be open-minded in terms of collecting the needs and concepts from the findings (Bryman, 2012).

3.3.1 Primary data collection: Interview

Interviews have been considered to be a primary alternative for data collection (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016) in a qualitative study and will thus be an included method. The interviews are including a total amount of 10 sampling cases. Moreover, doing the interviews semi-structured can help to keep the approach and interaction undetermined and to allow the participant to bring their experiences and perspectives (Bryman, 2012), whichever direction in radical innovation it might be. The structure is due to the individual point of departure, where any preconceptions will not make an impact. However, experiencing that radical innovation is a broad term assumes that the conversation should have a clear framework to make the interviews topical.

Figure 09. The interview framework. Illustration by Ivana Lasovan.

Hence, the process of 3 different phases; define, execute and implement are inspiring the questions and will lead them around the firms’ definition, execution, and implementation of radical innovation (see Figure 09, more details of the interview framework in Appendix A). Each contact with the interviewee started with an introduction to the thesis work and the purpose of the interview. Likewise, each interviewee had an introduction about their role in the specific firm to understand their point of view. The roles of each respondent have been a part of the knowledge sharing from their experiences of driving corporative innovation and the connection to radical innovation. Below is a table that lists the interviewees and their role in the firm. Because of some anonymity, industries are stated instead of organization names (see Table 01).

All participants had the possibility to remain pseudonyms, partly because of the ability to talk more openly about strategic and operational information that could be sensitive. A decision was made to keep all interviewees anonymous and name them Respondent, followed by a number to more naturally keep track of what role and industry that associates with the mentioned experience. The organizations' names were, in some cases, approved identifiable and are therefore mentioned (see Figure 08). Some interviewees also shared a request regarding receiving approval before the determination of the thesis. Each interview was made in person or by a video conference due to practical circumstances and lasted between 40-60 minutes. Prepared questions and subjects were supporting the interview, but a focal point was on having an open dialogue where the interviewee was leading the conversation. If needed, subjects in the interview framework were supporting if the direction got modified. 3.3.2 Interactive data collection: Mind Mapping

This research has provided a second source of knowledge and data by a consultancy firm. A workshop was of help to get the experience of the partnered firm Googol and collect their experiences from external projects as an innovation consultancy firm. The workshop helps to provide what factors they think are needed to increase radical innovation in organizations and how their visualization would match with the interviewed firms. Doing a mind map with idea generation and concept development was the starting point of the workshop (Martin and Hanington, 2012). Martin and Hanington (2012) believe that mind mapping can help to reflect on complex problems and connect alternatives through a non-linear process. The initiated process has been to gather the consultants of the innovation firm Googol in an interactive session with a discussion on what internal circumstances that are needed for radical innovation to occur. Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, there have been limitations in having a physical meeting. An adaption was taking place because of the situation, and a conclusion took place for an optional digital contribution. A digital platform was selected from what was familiar and approved in the firm to maintain a straightforward method for all involved.

Further on, a canvas, Post-it Notes, and symbols helped to frame the platform and were used to pinpoint different components. Figure 10 illustrates the disposition of the framework (see Figure 10). One praxis of how to conduct the mind map was suggesting to shape data in visual themes and patterns (Martin and Hanington, 2012). However, with the circumstances of using a digital platform to simplify the process for the participators, various optional approaches within the framework were allowed.

Figure 10. The framework of the mind mapping workshop. Design by Ivana Lasovan.

As the board fills in, it provides brief statements of connections and alternatives to the comparing sampling cases. Allowing secondary data collection gives an opportunity for a perspective outside of the organizations. Likewise, a secondary method supplementary extenuates the possibilities for subjectivity in the answers from the samplings. Meanwhile, including individuals that have innovation expertise from different situations could impact the outcome with a broad and general view.

3.4 Data Analysis

Data analysis aims to make sense of the data while reducing and interpreting what the interviewees have said and how the researcher makes meaning of it (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016). Furthermore, making meaning of the data includes finding answers to the research questions (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016).

The data analysis is following the research strategy of interaction and iteration in different stages. Analyzing the data is taking place throughout the process and during all methods of data collection. Transcripts and recorded audio were helping to start the data analysis, and every interview included comparisons with previous ones (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016). Suggestions were helping in the process of analysis (Bogdan and Biklen, 2011 in Merriam and Tisdell, 2016): to force oneself to narrow the data by making decisions, to write comments as the observer, to write down learnings during the process and explore the literature throughout the process. The process is dynamic, and once all data is collected, a final analysis can take place

(Merriam and Tisdell, 2016). A process of building theory is helping to extract the collected data and analyze it (Carlile and Christensen, 2005). By the application of inductive research that is firstly observing a theoretical background followed by empirical data, a descriptive model will support the process of data analysis in three different stages: observation, categorization, and association (Carlile and Christensen, 2005). A selected method will help conduct the process and ensure the inclusion of the stages.

Thematic Network is a method to help in the analysis of the collected data and organizes the data in themes for meaningful insights and exploration of relationships and patterns (Martin and Hanington, 2012; Attride-Stirling, 2001). The information provided during the interviews will be placed in three stages, as described by Martin and Hanington (2012): 1. Basic Themes: meaning that selected text segments or keywords that have been the most common and apparent concepts during the interviews are visible in a circle. Each selected component will, in combination with other components, organize themes that come from the combinations.

2. Organizing Themes: The second stage of the thematic network is conducting the basic themes into clusters of similar components. Clustering the themes can reveal connections for the analysis of certain arguments and situations. 3. Global Themes: The last stage exposes the data into statements as abstractive representations. The statements can also shape a summary that explains the complex and meaningful insights. With these stages, one can break down collected data in steps by applying patterns and themes to the discussions that took place during the interviews. The analysis will not only breakdown the text but also help to explore the data and integrate it (Attride-Stirling, 2001) to conclusions and answers to the research question. Finally, a comparison takes place between the findings, the collected data from the mind map workshop, and the theoretical background.

3.5 Research Quality

Involving qualitative methods for the data collection has been processed to maintain a deeper understanding of the cited firm. However, the research strategy is not equal to qualitative because of the critique and consequences it can bring. Bryman (2012) has brought up four different criticisms that qualitative research can impeach the quality of the study: the research being too subjective, difficult to replicate, giving problems in generalizing, having a lack of transparency. Being too subjective can be generated by the studied phenomena, while the replication can be difficult to maintain due to the unstructured process of the researcher (Bryman, 2012). Having challenges in generalizing the research, Bryman (2012) argues that ways of acknowledging generalization are by comparing previous studies and theories with the findings. My reflection of these criteria is to not only look at how to conduct the study but also how to form the outcome. Replicability and generalization are essential features in how the results can be used in further constellations, both scientifically and practically. Being too