1 CONTENTS

ABSTRACT………...2

INTRODUCTION……….3

Sexual selection………3

Sexual selection and parasites………3

Sexual selection, mate encounter rate and eutrophication...3

Olfactory cues and MHC (major histocompatibility complex)………...4

Olfactory cues and mate detection……….4

Pipefishes………..5

Hypothesis and Prediction………..6

MATERIAL AND METHODS………6

Location, capturing methods and fish care………...6

Experimental design………6 Statistical analyses………...7 RESULTS………..8 DISCUSSION………9 Future research………..10 AKNOWLEDGEMENTS………..10 REFERENCES………11 SUMMARY/SAMMANFATTNING……….………14 APPENDIX 1………...16

2 Abstract

The brood-nosed pipefish Syngnathus typhle is a pipefish with reversed sex roles. Males prefer to mate with large and ornamented females and females compete for partners. It has previously been shown that males mate more randomly when water becomes turbid.

In the Baltic Sea eutrophication has become a severe problem with turbid waters as one consequence. Turbidity makes visual cues less effective and thus weakens sexual selection in species using vision to discriminate between partners. It also affects mate encounter rates in species using vision to find each other. A lower mate encounter rate means a weakening of sexual selection and that individuals mate more randomly. One way to compensate for lower visibility would be to use olfactory cues instead. In this study I investigated whether S. typhle could use olfactory cues to discriminate between sexes. I found no support that they could use olfactory cues to find a partner.

3 Introduction

Sexual selection

Darwin (1871) introduced sexual selection to describe characters (e.g. antlers, colours, long tails) that were costly and could not be explained by natural selection. Those secondary sexual characteristics help one sex, usually males, in the fight for access to the other sex or to attract the opposite sex. Failure in the fight does not lead to the death of an individual – it just means that he/(she) will not get any offspring. This results in male-male competition (intrasexual selection) and female choice (intersexual selection) or, more seldom, female-female competition and male choice (Darwin 1859, Darwin 1871).

Sexual selection and parasites

Sexual selection is predicted to be more intense in species that through the evolution have been more exposed to parasites and disease (Hamilton and Zuk 1982). These species develop energetically costly colourings, variable or complex songs, or other traits to give the choosing sex an honest picture of the individual’s health and vigour (e.g. ability to resist parasites and disease). Healthy individuals are allowed to fertilize more mates. This will select for

individuals to recognize healthy partners (e.g. passerine birds, Hamilton and Zuk 1982). It has been shown that female sticklebacks, Gasterosteus aculeatus, prefer males with brighter red colourings. Those “bright” males have been shown to have better

immunocompetence – genes that are more resistant to parasites (Milinski and Bakker 1990). Also their offspring are shown to have an increased resistance to parasites (Barber et al. 2001) In the brood-nosed pipefish Syngnathus typhle (a pipefish with reversed sex roles) it has been shown that males prefer females with few parasites (Rosenqvist and Johansson 1995). They determine whether a female is parasitized or not by visual cues (e.g. black spots in the skin) (Rosenqvist and Johansson 1995), selecting for individuals more resistant to the parasite and also select for individuals able to select these (Hamilton and Zuk 1982).

Sexual selection, mate encounter rate and eutrophication

Sexual selection is frequency dependent. It does not depend on actual frequency, but rather on encounter rate of potential partners (Janetos 1980, Real 1990, reviewed in Kokko and Rankin 2006, Heuschele 2009). Low encounter rate means a slackening of sexual selection, because the choosing sex (most often the females) tend to be less choosy with decreasing mate encounter rates (Crowley et al. 1991, reviewed in Kokko and Rankin 2006).

Eutrophication – nutrient enrichment of ecosystems (e.g. nitrogen and phosphorus; Smith 2003) – can affect mate encounter rates by making detection of potential mates more difficult (Heuschele 2009). Nowadays eutrophication and increased algal growth, that makes water more turbid and thus reduces visibility, becomes more common (Smith 2003). In the Baltic Sea, a brackish-water sea in northern Europe, the problem of eutrophication and increased algal growth is especially severe (reviewed in Bernes 2005, Cederwall and Elmgren 1980, HELCOM 2009).

Eutrophication affects the strength of sexual selection in species in the affected areas. In an experiment Järvenpää and Lindström (2004) showed that the sexual selection in the sand goby, Pomatoschistus minutus, is reduced in turbid conditions.

4

Another experiment made by Sundin et al. (2010) showed that males of S. typhle couldn’t discriminate between a large and a smaller partner in reduced visibility. Neither could they discriminate between those two categories by using olfactory cues.

Olfactory cues and MHC (major histocompatibility complex)

Olfactory cues are important in many fish species. Many species have the ability to

discriminate between a good and a lesser fit partner by olfactory cues (Fisher and Rosenthal 2006, Reusch et al. 2001, Shohet and Watt 2004).

MHC (major histocompatibility complex) is a gene complex that plays a role in sexual selection (Reusch et al. 2001, Edwards and Hedrick 1998, Penn and Potts 1999). It also influences body odour (Reusch et al. 2001, Yamasaki et al. 1976, Singh et al. 1987, Penn and Potts 1998). Most of the immune system’s genetic variation is located at the major

histocompatibility complex (MHC) which contains several linked genes that encode cell surface MHC receptors. Each variant of the MHC receptor is able to bind only a limited number of different peptides (antigens), and different MHC alleles thus allow the presentation of a different set of antigens. Several studies have found an association between specific MHC haplotypes and resistance to infectious diseases and autoimmune disorders in mammals, birds and fish (reviewed in Bernatchez and Landry 2003). Therefore, it has been suggested that the high degree of within-population variability of MHC genes is the result of selection from pathogens. Furthermore it has been suggested that MHC heterozygous individuals may be able to detect a larger set of antigens and therefore be more resistant to diseases. It has been shown that female mice (Mus) prefer to mate with males with a MHC haplotype different from that of their own (Egid and Brown 1989). In sticklebacks, Gasterosteus

aculeatus, females prefer mates with many MHC alleles at different loci (Reusch et al. 2001). This is probably a strategy to increase the offspring’s ability to recognize parasites, and hence their ability to fight off disease (Reusch et al. 2001, Kasahara 1999).

Olfactory cues and mate detection

Before a mate choice can occur an individual must find another individual to mate with – mate detection. In some species mate detection is facilitated by the use of olfactory cues (Vogt and Riddiford 1981, Wcislo 1991). A male silk moth, Antheraea polyphemus, can detect a female on large distances (up to 4.5 km away) by using his sensitive, plumous antennae to detect female sex pheromones (Vogt and Riddiford 1981). William T. Wcislo (1991) showed in an experiment that males of the solitary sweat bee, Nomia triangulifera, uses olfactory cues in the search for females. The males contacted dead, untreated females more often than females that had been washed in hexane.

Investigation in G. aculeatus found that females in turbid condition switch from using visual cues, to using olfactory cues to assess their mates (Heuschele 2009, Heuschele et al. 2009). Experiments on the gulf pipefish Syngnathus scovelli has shown that males of this species could not distinguish between a good and a lesser fit female using olfactory cues, but they were able to discriminate between sexes by using olfactory cues (Ratterman et al. 2009).

5 Pipefishes

Pipefishes (Syngnathidae) are teleost fish with sex role reversal. Here female-female competition and male choice is the common pattern (Berglund et al. 1986b, Berglund and Rosenqvist 2003, Vincent 1992, Vincent et al. 1992, Scobell et al. 2009). They exhibit extensive paternal care (Vincent 1992). The male receives the eggs from the female via an ovipositor (Berglund 1993) and protect, aerate, nourish and osmoregulate them on his body (Vincent 1992). There are different degrees of specialisation in the different species (Vincent 1992); from ventral gluing on the body (e.g. Nerophis), to a slight wall which increases the protection (e.g. Corythoichthys), to flaps which are fully enclosing the eggs (e.g. Syngnathus), to the fully sealed brood pouch which is an extreme morphological specialisation

(Hippocampus - seahorse) (Masonjones and Lewis 2000). As fertilization occurs in the brood pouch, the male has 100% paternity confidence (Berglund and Rosenqvist 2003). Even in species where fertilization occurs externally (e.g. Nerophis ophidion) the male has a paternity confidence of 100 % or almost 100% (Mccoy et al. 2001).

The male is pregnant for several weeks (Berglund et al. 1986b, Berglund et al. 1989, Berglund and Rosenqvist 1990, Vincent 1992). The length of the pregnancy time differs between species (Ahnesjö 1992b; Berglund et al. 1989; Matsumoto and Yanagisawa 2001; Scobell et al. 2009). The pregnancy time is also dependent on the temperature of the water (Ahnesjö 1995, Ahnesjö 2008). Cold water gives a longer pregnancy. Warm water speeds up the reproductive rate in males and they actively places themselves in warmer parts of the water when given the choice (Ahnesjö 2008). Females are not as affected of differences in temperature (Ahnesjö 1995, Ahnesjö 2008).

The male gives birth to several small but fully developed young (Vincent 1992; Ahnesjö 1992b). After birth there is no more parental care (Ahnesjö 1992b, Berglund et al. 1986b). Most pipefishes, including brood-nosed pipefish Syngnathus typhle, live in eelgrass meadows (Berglund and Rosenqvist 2003, Berglund and Rosenqvist 2001a, Vincent 1995). Like all syngnathids (e.g. pipefishes, seahorses and seadragons) they are slow moving and highly cryptic, almost invisible in their habitat. Usually a pipefish keeps itself in a vertical position mimicking the eelgrasses movement (Berglund and Rosenqvist 2003; Berglund and Rosenqvist 2001a).

In courtship the usual crypsis of the pipefish is replaced by more conspicuous behaviour. A lengthy, ritualized, mutual dance is performed before the female is allowed to transfer her eggs into the male’s brood pouch. The dance includes courtship groups – a lek-like behaviour of groups of females performing and males swimming below in the eelgrass seeking out female courtship groups (Vincent et al. 1994). Females sometimes display an ornament – temporary or stationary – and males prefer ornamented females (Berglund et al. 1986b, Berglund and Rosenqvist 2001a, Berglund and Rosenqvist 2003, Rosenqvist 1990, Scobell et al. 2009, Silva et al. 2008, Vincent et al. 1992).

The sexes in S. typhle are quite alike. Females and males do not differ so much in size. The ornament in S. typhle is a temporary, striped pattern mostly expressed by females. (Berglund and Rosenqvist 2003).

Pipefish males use visual cues to assess mate quality. When testing the use of olfactory cues in pipefish mate choice, the mating pattern seemed to be random (Ratterman et al. 2009, Sundin et al. 2010) On the other hand in the gulf pipefish Syngnathus scovelli it has been shown that males were able to discriminate between the sexes by olfactory cues (Ratterman et al. 2009).

6 Hypothesis and Prediction

In this study I hypothesize that the male S. typhle is able to discriminate between the sexes using olfactory cues only. I predict that the male pipefish will be spending more time close to the olfactory cues from the female compared to the olfactory cues from the male.

Material and methods

Location, capturing methods and fish care

All experiments were carried out at Ar research station in the north of Gotland, Sweden, in June in 2010. The fish, Syngnathus typhle, were caught during May 22 to June 19 2010 at two different locations on the Gotland east coast – Botvaldevik (N57˚34.942’ E18˚48.702’) and Kyllaj (N57˚44.739’ E18˚57.129’). They were caught in shallow eel-grass meadows, Zostera marina, (< 10 m depth) by using a small beam trawl (mesh size 4 mm) that was pulled by a small motorboat. All the fish used in the experiment had not started to reproduce.

At the research station the fish were kept in 650 liter barrels with continuously renewed seawater. The barrels were also equipped with airstones. The sexes were kept separate in order to prevent males from getting pregnant. The barrels were cleaned daily. Artificial eel-grass was used for shelter.

Temperature and salinity followed natural conditions (temperature 8-19˚C, Salinity 6,0-6,5‰). Artificial light also followed natural conditions (07.00-22.00) and there were windows in the laboratory.

The fish were fed three times a day with wild caught mysids and frozen and laboratory hatched artemia.

Experimental design

The experiment took place during June 20 to June 28 2010. Each replicate contained one focal male placed in an 140 liter aquaria (40x50x70cm), one stimuli female and one stimuli male placed in two 20 liter aquaria (17x20x60cm). The placement of the female in the left or right aquaria was decided by randomization (www.random.org, 2010-04-12). Tubes from the small aquaria containing the stimuli fish carried water to the focal aquaria. A pump (Watson

Marlow 205 U) made sure that the water flow was constant (45-50 ml/min).The focal aquaria was separated with a 20 cm long, transparent, plastic divider (40% of the aquaria = the choice zone), with one stimuli aquaria at each side of the divider (Figure 1.). In each compartment in the choice zone the two tubes carrying stimuli water was fastened in the aquaria wall – one close to the bottom and one 5-10 cm above. A third tube containing air was fastened at the bottom of the aquaria releasing approximately 1 bubble/second. This was done to ensure water movement so that stimuli water could circulate and not sink to the bottom. In the stimuli aquaria airstones were used to ensure water movement and oxygenation. This was tested by adding colored water into the tanks.

An artificial eel-grass was placed in each stimuli aquaria to reduce the stress-level for the fish. In the focal aquaria one plant of artificial eel-grasses were placed in front of each choice-zone and one on the opposite side (see Figure 1.)

7

Figure 1. The experimental setup. The larger aquaria contained the focal male, the two small aquaria contained one stimuli fish each (one male, one female). A divider separated the upper half of the focal aquaria, giving a choice zone representing 40 % of the aquaria. Dividers between the focal male and the “choice” individuals blocked the visual influence between the compartments.

The experiment contained two parts. In the first part, the focal male was allowed to choose the male or the female side of the aquaria (or to stay in the “no choice”-zone) by using olfactory cues only. In the second part, directly following the first, the barriers blocking the sight were removed and the male that was allowed to choose again, now using visual cues. The

olfactory-experiment always preceded the visual-experiment.

Each replicate started with an acclimatization period of 60 min. After that the pump

transferring stimuli-water to the focal male was started. The focal male was gently moved to a start-position in the “no choice”-zone in order to be exposed to both stimuli smells. After that the focal male’s position was noted every 15 min in 150 min (10 readings). The visual-experiment started directly after the olfactory-visual-experiment without another acclimatzatiion period. The pump was turned off and the barriers blocking the vision were removed. Again the focal male was moved to a start position in the “no choice”-zone. After that the focal male’s position was noted every 15 min in 150 min (10 readings).

Only the replicates where the focal male changed zone (e.g. female zone, male zone, “no choice”-zone) at least once were used, leaving 22 replicates (out of 32) in the olfactory experiment and 21 (out of 28) replicates in the visual experiment.

Statistical Analyses

I compared the number of observations in each zone for each focal male (Appendix 1). Proportion of time (%) spent in the choice zone (e.g. time spent in the male or in the female compartment) was analysed with Wilcoxon test for matched pairs in order to see whether the focal male placed himself randomly within the aquaria. I then analyzed whether the focal male spent proportionally more time (%) choosing the female than choosing the male side of the aquaria. In this analysis I ignored the “no choice”-time and counted the pure choice-time (100%). Proportion of time choosing the female side added to proportion of time choosing the male side, is thus always 1. These proportions were analysed with Wilcoxon test for matched

8

pairs in order to see whether the focal male spent significantly more time in one compartment or another.

I did the same analyses for both smell and sight trials.

Results

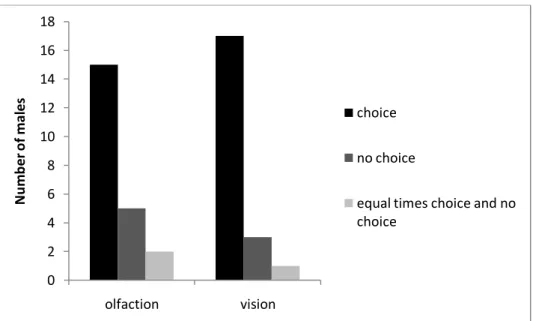

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the focal males’ preferences of the choice and no choice zones. Figure 3 shows the distribution of the focal males’ preference of the female and male zone. The raw data is shown in Appendix 1.

In the olfactory trials the focal male spent significantly more time in the choice zone than in the “no choice”-zone (T=30, n=22, P<0,002, Wilcoxon test for matches pairs), but there was no significant difference between choosing the female or the male compartment (T=92, n=22, P>0,05, Wilcoxon test for matched pairs).

In the visual trials the focal male spent significantly more time in the choice zone than in the “no choice”-zone (T=28,5, n=21, P<0,002, Wilcoxon test for matched pairs). The focal male also showed a significant preference for the female side of the aquaria (T=49, n=21, P<0,02, Wilcoxon test for matched pairs).

Figure 2. Numbers of focal males preferring (being observed to be more in one zone) the choice-zone or the “no choice”-zone using olfactory cues only or vision. Additionally the number of males without any zone preference is shown. 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 olfaction vision N u m b e r o f m al e s choice no choice

equal times choice and no choice

9

Figure 3. Number of focal males preferring (being observed to be more in one zone) or spending equal time in the male or the female zone using olfactory cues only, then visual cues. Focal males spending most of the time in the no choice zone or spending equal time in choice zone and no choice zone are not shown in the figure.

Discussion

The brood-nosed pipefish Syngnathus typhle is a species that uses visual cues in assessing mate quality (Berglund et al. 1986b, Berglund and Rosenqvist 1993, Berglund et al. 1997, Berglund and Rosenqvist 2001a, Berglund and Rosenqvist 2003, Berglund et al. 2005, Berglund and Rosenqvist 2009, Bernet et al. 1998, Rosenqvist 1990, Rosenqvist and

Johansson 1995, Sandvik et al. 2000). When the water becomes turbid the male can no longer discriminate between the quality of the females (Sundin et al. 2010). I found that the male S. typhle do not use olfactory cues to discriminate between sexes. This means that when water becomes turbid it will have more difficulty to find a partner (Heuschele 2009). This will lead to spending more time and energy to find a partner and mate encounter rates will decrease. When the sexually dimorphic stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus is exposed to turbid conditions it switches from using visual cues in assessing mate quality to using olfaction (Heuchele 2009, Heuschele et al. 2009). S. typhle do not switch to use olfactory cues and thus on average makes worse mate choice in turbid condition than in clear conditions (Sundin et al. 2010). This could be a problem and potentially decrease the viability in the offspring if, like in passerine birds, sexual selection is a tool to single out those individuals that will pass on good genes and give the offspring a good immune system (Hamilton and Zuk 1982). The difference in result here compared to the one found by Ratterman et al. 2009 in gulf pipefish (which used olfactory cues to discriminate between sexes) can not be explained by this experimental setup. When investigating whether males could discriminate between sexes by using visual cues they chose the female. This result shows that the experimental setup was working. Also, the males preferred to be in the choice zone.

Here I show that olfactory cues do not seem to be able to compensate for the absence of visibility; in fact, in this experiment males seemed not to use smell at all to find a female. These results are also in agreement with a previous experiment (Sundin et al. 2010).

Even though chemical cues have been shown to allow male Syngnathus scovelli pipefish to discriminate between males and females, smell alone did not appear to influence male mate choice (Ratterman et al. 2009). In other species chemical rather than visual communication has been shown to be the most effective long-distance communication, especially in turbid

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 olfaction vision N u mb er o f ma les female male

equal times in male and female zone

10

environments (Dusenbury, 1992). Male S. typhle seems to be the searching sex while females often display in groups (Vincent et al. 1994). Maybe S. typhle males may use smell on a long distance to locate other pipefish, and then switch to visual cues on a closer range to

discriminate between sexes and to assess which female to choose.

One more reason, why S. typhle did not seem to use olfactory cues may be due to how long time the Baltic Sea has been turbid. The time (evolutionary) may not have been long enough to allow pipefish to evolve into using olfactory cues. Habitat dependent selection could eventually adjust the value of chemical cue in pipefish communication; however this would require a gene flow between breeding sites low enough to allow local adaptations.

In conclusion, I have shown that males can not discriminate between males and females by using olfactory cues alone. I have shown that in the absence of visibility e.g. by heavy water turbidity that hampers adaptive mate choice in brood-nosed pipefish can not be compensated by using olfactory cues. Thus, the present-day increase in turbidity due to human activities may pose a threat to these pipefish populations if adaptive mate choice is vital to population viability. Also, the effect of eutrophication and turbidity on eelgrass, Zostera marina, habitat-loss is a real threat not only for pipefishes but also for other species depending on the eelgrass for survival and reproduction (Baden et al. 2003, Pihl et al. 2006). An increased turbidity will reduce light-levels in the water and thus hamper the growth of eelgrass, Z. marina (HELCOM 2009).

Future research

Future research on the impact of phytoplankton bloom on S. typhle should investigate if the reproductive success will change. Will males get fewer eggs (e.g. fewer copulations takes place) in turbid conditions? Will the pipefish population decrease when turbidity increases? To examinate whether the weakening in sexual selection is a problem for S. typhle one should compare viability in the offspring that is either sired in turbid or clear water (e.g. in conditions where the parents have chosen their partner either randomly or non-randomly).

Aknowledgement

I want to thank my supervisor Professor Gunilla Rosenqvist, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, for her great support, guidance, good critics and practical help. I want to thank Josefin Sundin, Uppsala University, for her help, support and good critics. I also want to thank Ronny Höglund for practical help and support. I want to thank Örjan Jacobsson, Christine Stocklassa Palmlöv and Professor Anders Berglund, Uppsala University, for help with fishing and caring for the fish. I want to thank Anders Nissling and Ar Research Station for letting me occupy the station for so long… I also want to thank Anders Nissling for good critics. I want to thank Almedalsbiblioteket in Visby, Gotland, for helping me find some of the literature.

Catching, handling and experimentation was done under licence Dnr 118-2008 from the Swedish Board of Agriculture. It was also done under licence Dnr 2006-0966 from the

Swedish Animal Welfare Agency and under licence Dnr S 155-09 from the Swedish Board of Agriculture.

11 References

Ahnesjö, I. 1992b. Fewer newborn results in superior juvenils in the paternally brooding pipefish Syngnathus typhle. J Fish Biol 41B: 53-63

Ahnesjö, I. 1995. Temperature affects male and female potential reproductive rates differently in the sex-role reversed pipefish Syngnathus typhle. Behav Ecol 6: 229–233 Ahnesjö, I. 2008. Behavioural temperature preference in a brooding male pipefish

Syngnathus typhle. Journal of Fish Biology. Vol. 73:4, 1039-1045

Baden, S., Gullström, M., Lundén, B., Pihl, L., Rosenberg, R. 2003. Vanishing seagrass (Zostera marina, L.) in swedish coastal waters. Ambio Vol. 32: 5, 374-377

Barber, I., Arnott, S., Braithwaite, V., Andrew, J., Huntingford, F. 2001. Indirect fitness consequences of mate choice in sticklebacks: offspring of brighter males grow slowly but resist parasitic infections. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences, 268:71-76.

Berglund, A., G. Rosenqvist, and I. Svensson. 1986b. Mate choice, fecundity and sexual dimorphism in two pipefish species (Syngnathidae). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 19, 301-307.

Berglund, A., G. Rosenqvist, and I. Svensson. 1989. Reproductive success of females limited by males in two pipefish species. The American Naturalist 133, 506-516. Berglund, A., Rosenqvist, G. 1990. Male limitation of female reproductive success in a

pipefish: effects of body size differences. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 27, 129-133.

Berglund, A. 1993. Risky sex: male pipefishes mate at random in the presence of a predator. Animal Behaviour 46, 169-175.

Berglund, A. and Rosenqvist, G. 1993. Selective males and ardent females in pipefishes. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 32, 331-336.

Berglund, A. Rosenqvist, G., Bernet, P. 1997. Ornamentation predicts reproductive success in female pipefish. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 40, 140-145

Berglund, A., Rosenqvist, G. 2001a. Male pipefish prefer ornamented females. Animal behaviour, 2001, 61, 345-350

Berglund, A., Rosenqvist, G. 2003. Sex role reversal in pipefish. Advances in the Study of Behavior 32, 131-167.

Berglund, A., Sandvik Widemo, M., Rosenqvist, G. 2005. Sex-role reversal revisited: choosy females and ornamented, competitive males in a pipefish. Behavioral Ecology 16, 649–655.

Berglund, A. and Rosenqvist, G. 2009. An intimidating ornament in a female pipefish. Behavioral Ecology 20, 54-59.

Bernatchez, L., Landry, C. 2003. MHC studies in nonmodel vertebrates: what have we learned about natural selection in 15 years? Journal of Evolutionary Biology Vol. 16:3, 363-377

Bernes, C., 2005. Monitor 19. Förändringar under ytan – Sveriges havsmiljö granskad på djupet. Publishers; Fälth & Hässler, Värnamo, 2005

Bernet, P., Rosenqvist, R., Berglund, A. 1998. Female-female competition affects female ornamentation in the sex-role reversed pipefish Syngnathus typhle. Behaviour 135, 535-550.

*Cederwall, H., Elmgren, R. 1980. Biomass increase of benthic macrofauna demonstrates eutrophication of the Baltic Sea. Ophelia, Suppl. 1, p. 287

Crowley, P. H., Travers, S. E., Linton, M. C., Cohn, S. L., Sih, A., Sargent, R. C. 1991. Mate density, predation risk, and the seasonal sequence of mate choices: a dynamic game. Am. Nat. 137, 567–596.

12

Darwin, C. 1859. On the Origin of species. Murray, London.

Darwin, C. 1871. The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. Murray, London. Dusenbury, D. B. 1992. Sensory Ecology: How Organisms Acquire and Respond to

Information. W.H. Freeman & Company, New York, NY.

Edwards, S. V., Hedrick, P. W. 1998. Evolution and ecology of MHC molecules: from genomics to sexual selection. Trends Ecol. Evol. 13, 305-311

Egid, K., Brown, J. L. 1989. The major histocompatibility complex and female mating preferences in mice. Anim Behav, 38, 548–550.

Fisher, H. S., Rosenthal, G. G. 2006. Female swordtail fish use chemical cues to select well-fed mates. Anim. Behav. 72,721-725.

Hamilton, W. D., Zuk, M. 1982. Heritable true fitness and bright birds: a role for parasites? Science 218, 384-387

HELCOM (2009) Eutrophication in the Baltic Sea: An Integrated Thematic Assessment of the Effects of Nutrient Enrichment in the Baltic Sea Region. Baltic Sea Environmental Proceedings No. 115B Available Online: www.helcom.fi [Accessed 2010-07-13] Heuschele, J. 2009. The influence of eutrophication on sexual selection in sticklebacks.

PhDThesis,University of Helsinki, Helsinki.

*Heuschele, J., Mannerla, M., Gienapp, P., Candolin, U. 2009. Environment-dependent use of mate choice cues in sticklebacks. Behavioral ecology, 20(6):1223-1227

Janetos, A. 1980. Strategies of female mate choice - a theoretical analysis. Behavioral Ecology And Sociobiology, 7:107-112.

Järvenpää, M., Lindström, K. 2004. Water turbidity by algal blooms causes mating system breakdown in a shallow-water fish, the sand goby Pomatoschistus minutus.Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 271, 2361-2365

Kasahara, M. 1999. The chromosomal duplication model of the major histocompatibility complex. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 167, 17-32

Kokko, H., & Rankin, D. 2006. Lonely hearts or sex in the city? Density-dependent effects in mating systems. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences, 361:319-334.

Masonjones, H. D., Lewis, S. M. 2000. Differences in potential reproductive rates of male and female seahorses related to courtship roles. Animal Behaviour, Volume 59, Issue 1, January 2000, Pages 11-20

Matsumoto, K., Yanagisawa, Y. 2001. Monogamy and sex role reversal in the pipefish Corythoichthys haematopterus. Animal Behaviour, Volume 61, Issue 1, January 2001, Pages 163-170

Mccoy, E. E., Jones, A. G., Avise, J. C. 2001. The genetic mating system and tests for cuckoldry in a pipefish species in which males fertilize eggs and brood offspring externally. Molecular ecology. 10(7): 1793-1800

Milinski, M., Bakker, T. C. M. 1990. Female sticklebacks use male coloration in mate choice and hence avoid parasitized males. Nature. 344, 330-333

Penn, D. & Potts,W. K. 1998. How do major histocompatibility complex genes influence odor and mating preferences? Adv. Immunol. 69, 411-435

Penn, D. & Potts, W. K. 1999. The evolution of mating preferences and major histocompatibility complex genes. Am. Nat. 153, 145-164

Pihl, L., Baden, S., Kautsky, N., Rönnbäck, P., Söderqvist, T., Troell, M., Wennhage, H. 2006. Shift in fish assemblage structure due to loss of seagrass Zostera marina habitats in Sweden. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 67: 1-2, 123-132

Ratterman, N. L., Rosenthal, G. G., Jones, A. G. 2009. Sex recognition via chemical cues in the sex-role-reversed gulf pipefish (Syngnathus scovelli). Ethology, 115, 339-346

13

Real, L. 1990. Search Theory and Mate Choice .1. Models of Single-Sex Discrimination. The American Naturalist, 136:376-405.

Reusch, T. B. H., Haberli, M. A., Aeschlimann, P. B., Milinski, M. 2001. Female

sticklebacks count alleles in a strategy of sexual selection explaining MHC polymorphism. Nature, 414, issue 6861: 300-302

Rosenqvist, G. 1990. Male mate choice and female-female competition for mates in the pipefish Nerophis ophidion. Animal Behaviour, Volume 39, Issue 6, June 1990, Pages 1110-1115

Rosenqvist, G., Johansson, K. 1995. Male avoidance of parasitized females explained by direct benefits in a pipefish. Animal Behaviour, Volume 49, Issue 4, April 1995, Pages 1039-1045

Sandvik, M., Rosenqvist, G., Berglund, A. 2000. Male and female mate choice affects offspring quality in a sex role reversed pipefish. Proceedings of the Royal Society series B 267, 2151-2155.

Scobell, S. K., Fudichar, A. M., Knapp, R. 2009. Potential reproductive rate of a sex-role reversed pipefish over several bouts of mating. Animal behaviour 78 (2009) 747-753 Silva, K., Vieira, M. N., Almada, V. C., Monteiro, N. M. 2008. Can the limited marsupium

space be a limiting factor for Syngnathus abaseter females. Insights from a population with size-assortative mating. Journal of Animal Ecology, 77, 390-394

Singh, P. B., Brown, R. E., Roser, B. 1987. MHC antigens in urine as olfactory recognition cues. Nature 327,161-164

Smith, V. H. 2003. Eutrophication of freshwater and coastal marine ecosystems – A global problem. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 10, 126-139

Shohet, A. J., Watt, P. J. 2004. Female association preferences based on olfactory cues in the guppy, Poecilia reticulate. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 55, 363-369

Sundin, J., Berglund, A., Rosenqvist, G. 2010. Turbidity hampers mate choice in a pipefish. Ethology, 116:8, 713-721(9)

Vincent, A. C. J. 1992. Prospects for sex role reversal in teleost fishes. Neth. J. Zool. 42, 392-399

Vincent, A., Ahnesjö, I., Berglund, A., Rosenqvist, G. 1992. Pipefishes and Seahorses: Are they all Sex Role Reversed? Trends in Ecology and Evolution. Vol. 7, No. 7

Vincent, A., Ahnesjö, I., and Berglund, A. 1994. Operational sex ratios and behavioural sex differences in a pipefish population. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 34, 435-442. Vincent, A. C. J. 1995. A role for daily greetings in maintaining seahorse pair bonds. Animal

Behaviour, Volume 49, Issue 1, January 1995, Pages 258-260

Vogt, R. G., Riddiford, L. M. 1981. Pheromone binding and inactivation by moth antennae. Nature, 293, 161 – 163

Wcislo, W. T. 1992. Attraction and learning in mate-finding by solitary bees, Lasioglossum (DiMictus) Hgueresi Wcislo and Nomia triangulifera Vachal (Hymenoptera: Halictidae). Behav Ecol Sociobiol, 31: 139-148

www.random.org, 2010-04-12

Yamazaki, K, Boyse, E A, Miké, V, Thaler, H T, Mathieson, B J, Abbott, J. 1976. Control of mating preference in mice by genes in the major histocompatibility complex. J Exp Med, 144, 1324–1335.

14 Summary/Sammanfattning

År 1871 introducerade Darwin begreppet ”sexuell selektion” för att beskriva kostsamma karaktärer som inte kan förklaras med naturlig selektion. Dessa sekundära könskaraktärer hjälper individer i kampen för att få reproducera sig. En undersökning på tättingar har visat att sexuell selektion är mer intensiv hos arter som genom evolutionen har varit mer utsatta för parasiter. Hos dessa arter har det varit extra viktigt att hitta en partner som är frisk och kan föra vidare gener till avkomman som kodar för ett bra immunsystem. En individ kan visa sin livskraftighet med bland annat kostsamma färger eller variationsrika och komplexa sånger.

Hos storspigg, Gasterosteus aculeatus, har man kunnat visa att honorna föredrar de hannar som har mest klarröda färger. Dessa färgstarka hannar har bättre immunförsvar än hannar med mindre röda färger. Man har också kunnat visa att de färggranna hannarnas ungar har bättre immunförsvar.

Hos tångsnällan, Syngnathus typhle, (en kantnål med omvända könsroller) har man kunnat visa att hannarna föredrar honor med få parasiter. Parasiterna syns som svarta prickar i skinnet. Detta borde driva på en evolution av gener som är mer resistenta mot parasiter.

Styrkan och betydelsen av sexuell selektion är beroende av hur ofta individer träffar på sina artfränder. Träffas de sällan är det bättre att ”ta första bästa” än att vänta och riskera att inte få reproducera sig alls. Träffas de ofta kan man kosta på sig att vara mer kräsen. Oftast är det honorna som är mest kräsna eftersom de för det mesta är begränsade av kostsamma ägg medan hannarna kan producera mängder av spermier.

Den eutrofiering av Östersjön som pågår nu får bland annat som följd att vattnet blir

grumligt och sikten kan försämras radikalt. Detta kan påverka hur ofta individer träffar på sina artfränder genom att försvåra upptäckandet av potentiella partners. Hos sandstubb,

Pomatoschistus minutus, har man kunnat visa att individer parar sig mer slumpmässigt i grumligt vatten. Även tångsnällan har svårt att bedöma kvaliteten på en partner när sikten är reducerad.

Lukt är en viktig faktor hos många arter i många olika djurgrupper – däggdjur, fiskar, insekter m. fl. Många arter kan skilja mellan en bra och en dålig partner med hjälp av lukt.

MHC (major histocompatibility complex) är ett genkomplex som påverkar kroppslukt och spelar stor roll i sexuell selektion för många arter. Hos en del arter väljs den partner som är så olik en själv som möjligt. Hos andra väljs den partner som själv har det bästa immunförsvaret.

En undersökning på storspigg har visat att de i klart vatten väljer partner med hjälp av syn. När vattnet blir grumligt växlar de till att välja med lukt.

Innan man kan välja en partner måste man hitta en. Många arter använder lukt för att underlätta sökandet efter en partner. En silkesfjärilshanne, Antheraea polyphemus, kan upptäcka en hona på upp till 4,5 km avstånd med hjälp av sina känsliga, fjäderlika antenner.

Tångsnällan är en benfisk som hör till familjen Syngnathidae – kantnålar, sjöhästar och sjödrakar ingår i denna familj. Den har omvända könsroller med hon-hon konkurrens och hanligt val. Dessutom är det hannen som blir gravid och bär på äggen. Hos tångsnällan förvaras äggen i en specialiserad ficka på magen. De förs över av honan via ett

äggläggningsrör och befruktas av hannen först när de ligger i hans ficka.

Tångsnällan lever i ålgräsängar, Zostera marina, på grunt vatten (2-10 m) där den för det mesta står stilla och härmar ålgräsets rörelser. I parningstider ändras fiskarnas kryptiska beteende och rör sig mer. De har långa parningsdanser där de simmar tillsammans och displayar för varandra. Dominanta individer – framför allt honor – visar ibland en

ornamentering: en svart randning längs kroppen. Tångsnällan använder syn för att bedöma partnerkvalitet. Experiment har gjorts för att undersöka om de kan bedöma partnerkvalitet med hjälp av lukt, men partnervalen blev slumpmässiga utan tillgång till syn.

15

Experiment har gjorts på en annan kantnålsart, Syngnathus scovelli, som lever i Mexikanska golfen. Liksom tångsnällan kan den inte använda lukt för att bedöma

partnerkvalitet. Däremot har man visat att den kan använda lukt för att skilja mellan hanne och hona – något som kan underlätta när man ska hitta en partner.

I mitt experiment har jag undersökt om tångsnällan med lukt kan skilja mellan hanne och hona. Min hypotes var att den skulle föredra honans sida av akvariet (se Figure 1.).

Experimenten utfördes på forskningsstationen i Ar på norra Gotland. Fiskarna fångades med hjälp av en minitrål på två lokaler på Gotlands östra sida: Botvaldevik och Kyllaj. På forskningsstationen förvarades fiskarna i stora akvarier sorterade efter kön. Akvarierna städades dagligen och fiskarna matades tre gånger om dagen med mysider och artemior.

Varje replikat bestod av en fokal hanne som placerades i ett 140 l akvarium, en stimuli-hona och en stimuli-hanne som placerades i två 20 l akvarier. Stimulivatten pumpades från de mindre akvarierna till de större (45-50 ml/min). Barriärer placerades mellan akvarierna för att hindra fiskarna från att se varandra.

Ett replikat gick till så att fiskarna först fick acklimatisera sig en timme i respektive

akvarium, varefter pumpen som pumpade stimulivatten sattes igång. Fokalhannen petades till en startposition i ickevals-zonen (se Figure 1.). Därefter gjordes avläsningar en gång var 15:e minut i 150 minuter. Direkt efter varje luktreplikat togs barriärerna som hindrade syn bort och ett replikat gjordes där fiskarna tilläts använda syn. Detta gjordes som en kontroll för att kunna utesluta att några allvarliga misstag begåtts i själva akvarieuppställningen.

Synreplikatet gjordes på samma sätt som luktreplikatet förutom att ingen ny

acklimatiseringsperiod inleddes. 32 luktreplikat gjordes varav 22 kunde användas. 28 synreplikat gjordes varav 21 kunde användas. De replikat ströks där fokalhannen inte bytte position minst en gång.

Jag testade mina data med Wilcoxon test for matched pairs och fann att det med enbart lukt inte var någon signifikant skillnad mellan hur ofta fokalhannen valde honans sida och hannens sida av akvariet. När fokalhannen hade tillgång till syn valde han däremot honans sida

signifikant mer än hannens sida.

Jag testade också om fokalhannen generellt sett placerade sig slumpmässigt i akvariet. Jag använde även här Wilcoxon test for matched pairs och fann att fokalhannen signifikant föredrog att befinna sig i val-zonen. Detta berodde dock troligen inte på stimulifiskarna utan mer på akvarieuppställningen. Miljön i ickevals-zonen upplevdes troligen som mer oskyddad av fisken eftersom glaset i den änden (av praktiska skäl för avläsningen) var genomskinligt.

Lukt kan alltså inte kompensera för syn om siktförhållandena förändras. Grumligt vatten gör både att tångsnällan får svårare att hitta en partner och får svårare att bedöma partnerns kvalitet när den väl hittar den. På sikt skulle eutrofiering och mer grumliga miljöer kunna hota artens livskraftighet genom att individer förbrukar mer energi i sökandet efter en partner och att ungarna överlever sämre då föräldrarna inte längre kan skilja mellan en högkvalitativ och en lågkvalitativ partner. Framtida undersökningar bör inrikta sig på att ta reda på hur viktig sexuell selektion är för ungarnas överlevnad. Man borde också undersöka om det blir färre parningar i grumligt vatten än i klart vatten. Får fiskarna så mycket färre avkommor att det kan hota artens livskraftighet? Framtida forskning borde också inrikta sig på att ta reda på hur eutrofiering påverkar tångsnällan generellt sett. Inte bara i partnerval utan också i

sammanhang som habitatförstörelse (man vet att grumligt vatten försämrar

ljusgenomsläppligheten i vattnet och därigenom försvårar för bland annat ålgräset),

upptäckande av predatorer och upptäckande av byte. I de båda sistnämnda fallen borde man undersöka om tångsnällan kan använda lukt för att upptäcka sina predatorer och bytesdjur.

16 Appendix 1. ID OLFACT_CHOICE: F OLFACT_CHOICE: M OLFACT_NO CHOICE 1* 0 10 0 2* 10 0 0 3 4 6 0 4* 0 10 0 5 0 5 5 6 0 6 4 7 6 0 4 8 4 3 3 9 0 2 8 10 2 1 7 11 8 0 2 12** x x x 13* 0 10 0 14 9 0 1 15* 10 0 0 16 5 3 2 17 3 1 6 18 6 4 0 19* 0 10 0 20* 10 0 0 21 3 7 0 22 4 0 6 23* 0 10 0 24 2 2 6 25 1 7 2 26 8 2 0 27* 0 10 0 28 2 4 4 29 0 9 1 30 5 2 3 31 9 0 1 32 5 0 5

ID = identification number of the focal male

Olfact_choice: F = number of observations of focal male in the female choice zone during the trials with olfaction

Olfact _choice:M = number of observations of focal male in the male choice zone during the trials with olfaction.

Olfact_no choice =number of observations of focal male in the no choice zone during the trials with olfaction.

*replicates where focal male did not change zone at least once were excluded from the analysis.

17 ID VISION_CHOICE: F VISION_CHOICE: M VISION_NO CHOICE 1*** x x x 2*** x x x 3*** x x x 4*** x x x 5 8 0 2 6 1 9 0 7 8 0 2 8* 0 10 0 9 6 3 1 10 6 3 1 11 4 4 2 12** x x x 13 0 1 9 14 7 0 3 15* 10 0 0 16 6 3 1 17 8 1 1 18 6 4 0 19 5 4 1 20 5 5 0 21 6 4 0 22 5 4 1 23* 10 0 0 24 2 0 8 25 5 0 5 26* 10 0 0 27 1 7 2 28 1 7 2 29* 0 10 0 30 1 0 9 31* 10 0 0 32 4 5 1

ID = identification number of the focal male

Vision_choice: F = number of observations of focal male in the female choice zone during the trials with vision.

Vision _choice:M = number of observations of focal male in the male choice zone during the trials with vision.

Vision_no choice =number of observations of focal male in the no choice zone during the trials with vision.

*replicates where focal male did not change zone at least once were excluded from the analysis.

** focal male sick – died during trials.