Malmö högskola

Lärarutbildningen

Kultur, språk, medier

Examensarbete

15 högskolepoäng

Gender Bias in EFL Textbook Dialogues

Könsfördelning i dialoger i engelska textböcker

Sara Johansson

Kim Bachelder Malmsjö

Lärarexamen 270hp

Engelska med inriktning mot undervisning och lärande 2009-05-19

Examinator: Bo Lundahl Handledare: Björn Sundmark

Abstract

This degree project is a quantitative study of dialogues and speaking exercises in twelve EFL textbooks used in secondary schools in Sweden. The chosen textbooks are from the four textbook series Happy, Time, Whats’s Up? and Wings Base Book. The aim is to investigate if there is any over-representation of female or male characters in the textbook dialogues. We will be looking at four different typologies, namely the number of initiated dialogues, turns taken, number of characters and words used. Previous research concerning classroom interaction, scholastic performance, textbooks and textbook dialogues is included to provide some background into this area. The findings show over-representation exists in all the textbook series in various degrees of both female and male characters. This degree project maps the over-representation of female and male characters both in the four textbook series and the twelve individual textbooks. Our results will show that while a textbook series might over-represent one gender it does not necessarily mean that the individual textbook within that series over-represents the same gender. The findings make it clear that educators need to be aware of gender-biased textbook dialogues in order to be better equipped to ensure equal opportunities for all learners.

Keywords: Gender bias, equal learning opportunities, EFL textbook dialogues, speaking

List of Contents

1. INTRODUCTION ... 7

1.1BACKGROUND………7

1.2PURPOSE ... 8

1.3RESEARCH QUESTION ... 8

2. PREVIOUS RESEARCH AND RELEVANT THEORIES ... 9

2.1BOYS’ AND GIRLS’PERFORMANCES IN SCHOOL ... 9

2.2FOREIGN LANGUAGE TEXTBOOKS ... 12

2.3FOREIGN LANGUAGE TEXTBOOK DIALOGUES ... 15

3. METHOD ... 19

3.1SELECTION OF TEXTBOOKS ... 19

3.2PROCEDURE ... 19

4. RESULTS ... 23

4.1TEXTBOOK SERIES TIME ... 23

4.2TEXTBOOK SERIES WINGS ... 25

4.3TEXTBOOK SERIES HAPPY ... 28

4.4TEXTBOOK SERIES WHAT’S UP? ... 30

5. ANALYSIS ... 33

6. CONCLUSION ... 36

REFERENCES ... 38

PRIMARY SOURCES ... 38

SECONDARY SOURCES ... 39

APPENDIX 1:FIRST TIME ... 41

APPENDIX 2:SECOND TIME ... 43

APPENDIX 3:THIRD TIME... 45

APPENDIX 4:FIRST TIME,SECOND TIME,THIRD TIME ... 46

APPENDIX 5:WINGS BASE BOOK 6 ... 47

APPENDIX 6:WINGS BASE BOOK 7 ... 49

APPENDIX 7:WINGS BASE BOOK 8 ... 53

APPENDIX 8:WINGS 6,WINGS 7,WINGS 8 ... 54

APPENDIX 9:HAPPY NO.1 ... 55

APPENDIX 10:HAPPY NO.2 ... 59

APPENDIX 11:HAPPY NO.3 ... 63

APPENDIX 12:HAPPY NO.1,HAPPY NO.2,HAPPY NO.3 ... 64

APPENDIX 13:WHAT’S UP?7 ... 65

APPENDIX 14:WHAT’S UP?8 ... 68

APPENDIX 15:WHAT’S UP?9 ... 70

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

According to the curriculum for Swedish compulsory schools, one important mission of the school system is to teach students the value of equality and for teachers to teach in a way that supports equality (Skolverket, 1996a). The curriculum states that “[t]he school should actively and consciously further equal rights and opportunities for men and women” and that “[t]he school has a responsibility to counteract traditional gender roles” (Skolverket, 2006a, pp. 4-5).

While the national curriculum stresses the importance of providing equal learning

opportunities for both boys and girls, research shows that this is not always the case in the classroom or in the teaching materials being used in the classroom (Mesthrie et al., 2000; Bayyurt & Litosseliti, 2006). In fact, research conducted during the past four decades found that texts and dialogues in English as a foreign language (EFL) textbooks showed an

imbalance in gender representation and traditional gender roles (Hartman & Judd, 1978; Jones et al., 1995; Bayyurt & Litosseliti, 2006). On a positive note, some research showed that a balanced representation of female and male characters in texts and textbook dialogues has improved over the years (Jones, Kitetu & Sunderland, 1995; Poulou, 1997). However, research done in 2002 showed that an unbalanced representation of gender still exists in textbooks (McGrath, 2004). It seems relevant to reinvestigate gender bias in EFL textbook dialogues currently being used in Swedish compulsory schools. It should be noted that while gender representation refers to how genders are depicted, gender bias or unbalanced

representation refers to when one gender is treated unfairly or is under-represented compared to another gender.

Why is this relevant? As future teachers, we need to know if the textbooks we are using are gender biased and we need to be prepared to adjust our application of these textbook dialogues to ensure we fulfil the national curriculum requirements of providing all our students an equal opportunity for learning. If we are unaware of gender bias in dialogues, we may inadvertently limit the speaking practice opportunities for the under-represented gender as well as fail in fulfilling curriculum requirements of providing equal rights for all students.

1.2 Purpose

The aim of this degree project is to investigate if gender bias exists in EFL textbook dialogues by taking a quantitative look at the number of times female and male characters speak in a dialogue and the number of words allocated female and male characters in these dialogues.

1.3 Research Question

We will look at twelve EFL textbooks currently being used in secondary schools in Sweden and investigate the following question:

2. Previous Research and Relevant Theories

2.1 Boys’ and Girls’ Performances in School

When discussing equal opportunities for boys and girls in schools, it is interesting to look at the wider picture and not only textbooks and dialogues. Looking at the whole society,

research from the 1990’s, conducted in several countries in the Western world, has suggested there has been a change in women’s and men’s conditions and attitudes since the 1970’s and 1980’s (Öhrn, 2002). Mats Björnsson (2005) pointed to the changes in women’s situations at home and in the labor market, girls’ views of education and new aspirations in life as some of the underlying reasons for the change in the gender patterns we see today. According to Elisabet Öhrn (2002), who did an overview of research conducted mainly in Sweden and the Nordic countries, girls seem to have become more visible in schools. Moreover, studies showed a more varied picture of boys’ and girls’ behavior and of their general situation in schools. Young women’s views of themselves have changed and girls have become more confident and active in the classroom. Öhrn (2002) mentioned Fagrell and Weis who wrote that girls have moved the boundaries and taken on new roles in traditionally male domains but boys have not done the same in traditionally female domains. In other words, the girl’s

position has been challenged in different ways but not the boy’s (Björnsson, 2005; Öhrn, 2002). However, Öhrn (2002) also wrote that we have to be careful not to exaggerate these trends because there are several studies from the Nordic countries suggesting that some gender stereotypes among children have been stable over time and have not changed since the 1970’s. Furthermore, there have only been a limited number of studies in this area and this new generation of girls is only referred to in a few of these studies.

A recurring topic in the gender debate during the 1990’s and the 2000’s has been how much space and attention boys and girls receive and take in different pedagogical situations (Einarsson, 2003). Several studies have suggested boys still dominate the classroom and interactions with their teachers as they did in the 1970’s. Younger, Warrington and Williams (1999) studied classroom interactions at four different schools in England and their research showed that the boys dominated the teacher-student interactions at three of the schools, that is, they received more questions from the teacher, they answered more questions directed to the whole class and they received more disciplinary comments from the teacher. At the fourth

school girls and boys received an equal number of questions and the girls answered more of the open questions directed to the whole class. Another interesting finding was that at three of the four schools the girls asked for more help and support than boys but, as mentioned above, the boys received more attention. Some teachers in the study commented that the fact that the girls asked for more help was a reason for paying more attention to the boys. Several teachers thought they treated boys and girls differently because they felt boys are not as prepared for the school environment as girls. Also interesting was that only a minority of the teachers thought they treated boys and girls equally (Younger, Warrington & Williams, 1999).

Research conducted in the Nordic countries indicated that the picture varied concerning how much space and attention one group of students received (Öhrn, 2002). There was a big variation between subjects, classes and schools whether girls or boys dominated the classroom. In one study conducted by Öhrn (2002), either girls dominated the class

interactions or there was no difference between the sexes in social sciences and languages. In another study Öhrn found there were differences between the two classes she followed. In one class there were no differences regarding speaking time and in the other class the boys often dominated (Öhrn, 2002). Looking at other studies we see that the picture is even more complex (Einarsson, 2003; Lundgren, 2000). When the boys dominated the classroom, it did not include all the boys and they did not dominate the interactions all the time. A large number of boys never answered questions voluntarily and there were also some girls who were active both verbally and physically. These findings suggest it is complicated to treat boys and girls as two homogenous groups.

When discussing classroom interactions, it is also important to consider what type of attention boys and girls receive. As we have seen, boys seemed to receive more disciplinary comments which could mean that more attention in the classroom is not necessarily a positive thing. Charlotta Einarsson (2003) also pointed out in her study of teacher-student classroom

interactions that teachers often used direct questions to boys in order to increase their on-task behavior. Looking at it from that perspective, receiving more questions could also be seen as a type of negative attention just as disciplinary comments. On the other hand, when learning English as a Foreign Language (EFL), answering questions could also be seen as an opportunity to use the target language and could therefore be considered as something positive. In other words, the situation is very complex and it is difficult to say if any group is at any advantage or disadvantage. The picture becomes even more complex when we look at

boys’ and girls’ performances, that is, their grades, test results and participation in higher education. If boys receive more attention than the girls and if the attention is positive, one could assume it would lead to differences in the results in the boys’ favor. However, reality shows something different.

A commonly discussed topic during the past two decades has not only been differences in classroom interactions but also the fact that girls outperform boys in school. Girls receive higher grades and better test results compared to boys and a larger number of girls also continue on to higher education (Björnsson, 2005; Öhrn, 2002). We can see the same pattern in many other countries in Europe, North America and Australasia (Younger, Warrington & Williams, 1999). Öhrn (2002) pointed out that girls achieving higher grades than boys is not a new phenomenon in Sweden. This could be seen already in the 1980’s and in some subjects as early as the 1960’s. In other countries the discussions have concerned whether it is time to focus more on boys and if the work procedures used in schools benefit a girl’s way of

expressing herself (Öhrn, 2002). These types of discussions about boys being the losers of the education system might imply that boys’ results have deteriorated. However, Younger, Warrington and Williams (1999) pointed out that “the phenomenon is actually one of relative rates of improvement for both sexes” (p. 326), which is also the case in Sweden (Öhrn, 2002).

Looking at the grades in year 9, girls usually perform better in languages while boys perform better in natural sciences (Öhrn, 2002). In most subjects there are more girls than boys receiving the higher grades Väl Godkänt (VG) and Mycket Väl Godkänt (MVG) and girls have significantly higher grade point averages (Skolverket, 2008). Furthermore, more girls (89,9 %) than boys (87,9 %) qualified for upper secondary school in 2008. In other words, they achieved at least Godkänt (G) in English, Swedish and mathematics. According to Öhrn (2002), girls perform somewhat better in verbal tests compared to boys while boys achieve better results in tests in mathematics and natural sciences. Especially interesting to look at considering the focus of this dissertation, are the results from the National test in English. When the results from the three different parts of the 2008 National test in English were compared, they showed that the students performed the best on the oral section (Skolverket, 2009). Only 3 % did not pass and an interesting fact is that there were about the same percentage of girls as boys who failed. However, girls performed better than boys, that is, more girls achieved the higher grades. According to Öhrn (2002), the gender patterns could vary depending on the method of measurement.

As seen in the above discussion, girls have higher grades and perform better in languages and more often better in verbal tests such as for example part A of the National test in English. Boys usually perform better on tests in natural sciences and mathematics, even though the differences between the sexes are decreasing in mathematics (Skolverket, 2009). Interesting to see is that in the past there has only been a focus on girls’ underachievement in natural

sciences and mathematics but not on boys’ underachievement in languages and other subjects (Öhrn, 2002). However, the interest in this area seems to be increasing considering the

volumes of published reports and articles focusing on this subject since the late 1990’s. It should be noted that studies conducted in Sweden are limited. Another point to emphasize is that it seems difficult to say if boys or girls are at any advantage or disadvantage when only the classroom interaction, or speaking time, is analyzed. It is therefore important to consider other factors that can explain the differences in the results on for example oral tests. Attitudes, school culture, dialogues and other types of speaking exercises could be such factors.

2.2 Foreign Language Textbooks

Research shows that the scholastic performance of boys differs from the scholastic

performance of girls. As mentioned earlier, girls performed better than boys on the National test in English (Skolverket, 2009). Factors that may contribute to performance differences have been under scrutiny in hopes of narrowing the performance gap. One such factor that has been under investigation is textbooks. This paper investigates gender bias in EFL textbook dialogues. Before looking at dialogues, however, let us first look at gender bias in textbooks in general. Studies conducted in the 1970’s, 1980’s, 1990’s and 2000’s have found that gender bias has often manifested itself with over-representation of male characters in textbook texts. Studies conducted in Sweden on this topic were limited.

In the late 1970’s, Pat Hartman and Elliot Judd (1978) investigated gender bias in Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) textbooks. Their study included fifteen TESOL textbooks which had been published in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s and were being used in the United States and Britain. The study showed that in these textbooks “women are often less visible than men, are often the butt of many jokes and are often placed in

stereotypical roles and assigned stereotypical emotional reactions” (Hartman & Judd, 1978, p. 383). It is interesting to note that in 1975 the American organization National Council of Teachers of English adopted a formal policy to encourage non-sexist language usage by publishers. However, despite these efforts, gender bias was undeniable.

In the 1980’s, six years after Hartman and Judd’s ground-breaking study, Karen Porreca (1984) conducted a similar study of English as a Second Language (ESL) textbooks. Porreca selected fifteen ESL textbooks purchased in the largest quantities by twenty-seven ESL locations in the USA. Porreca reinvestigated gender bias in EFL textbooks by looking at texts and illustrations in a quantitative manner. Her findings supported the findings of Hartman and Judd and she warned that there may be consequences with unrealistic depictions of females and males. She found a large presence of the masculine generic construction where the

textbook characters first appeared to be neutral characters but were invariably male characters rather than neutral or female characters. According to Sadker and Zittleman (2007), some publishers and authors of textbooks try to create “an illusion of equality” (p. 273) and thus might include pictures of women instead of revising the texts. While a neutral character might create a sense of un-biased gender representation, a masculine generic construction might perpetuate asymmetric gender representation.

One textbook in Porreca’s (1984) study, English Sentence Structure, used a repetitive pattern drill which most often featured a male character ‘John’. Porreca noted that “this type of all-male exercise (with five or more sentences) occurs 54 times throughout the book. The number of instances of similar all-female exercises is 6” (p. 714). Porreca’s study did not discuss if the drill excluded girls from being ‘John’ or the other males in the exercise but the message is clear that ‘John’ and the other males dominated this type of exercise and therefore may have given the impression that males rate higher than females. Freeman and McElhinny state that “[e]ducational settings also give students an understanding of their social identity in relation to each other and the institution” (as quoted in Bayyurt & Litosseliti, 2006, p. 73). A male-dominated text might suggest that boys have a right to be verbally dominant in the classroom and further that girls should say less in the classroom compared to boys. Porreca (1984) warned that textbooks represent authority and that a gender-biased text could have consequences for ESL learners, in particular “younger ESL learners, whose limited experience gives them little basis for questioning what they read” (p. 723).

Results from a study published by Skolverket (2006b, p. 70), showed a majority of English teachers in compulsory schools in Sweden use textbooks on a daily basis and make

assumptions about the authoritativeness of these textbooks. Eighty percent of the teachers who participated in the study thought that textbooks were the most important teaching material and a majority assumed that the use of textbooks guaranteed that they were working in accordance with the goals in the curriculum. However, in the same study Skolverket pointed out that the textbooks were not always in agreement with the fundamental values and the goals in the curriculum and therefore the content of the textbooks needed to be questioned by the teachers using them. Moira von Wright (1998) conducted a qualitative study of

textbooks used in Swedish secondary and upper secondary schools in physics and found that what were traditionally considered to be male qualities were valued higher than qualities traditionally considered female. Moreover, she found that the symbolism in the textbooks reinforced the traditional gender roles instead of following the goals of the steering documents concerning equality. Robin Richardson and Angela Wood (2000) felt that school curricula should always include ways to consider the personal identities of students and include “recognition of bias in literature and the media, and questioning of stereotypes” (p. 41). If educators are aware of gender-biased texts, it may be that they are better equipped to create an overall balance of gender representation in the material they use in their classroom.

Jane Sunderland (1998) looked at gender bias in textbook texts and classroom interaction and supported the argument that gender bias existed in textbooks and in the classroom. This was based on both her own observations and previous research done in the 1970’s and 1980’s. While Sunderland recognized that gender bias existed, she questioned whether it was actually important or not. Sunderland felt it was important to those who were concerned with gender bias but felt it was not important to some teachers unless they saw that gender-biased texts affected learning. She pointed out the impossibility of proving a correlation between biased texts and learning stating we can never predict how a reader might respond to a text.

Sunderland (1998) further pointed out that gender-biased texts might affect readers in many ways:

Some students may accept the bias and even enjoy it, others may be indeed alienated by it, and still others may recognize it for what it is and become

‘resistant readers’, rejecting either the gender representation itself or the gendered assumptions within the text. (p. 4)

Sunderland (1998) also observed that teachers played an important role in the discussion of gender bias. She noted that a text which seemed un-biased could have been interpreted or handled in a biased way by a teacher just as a biased text could have been interpreted or handled in an un-biased way.

Research conducted in 2004 showed that gender bias was still present in EFL textbooks. Ian McGrath (2004) cited a 2002 survey conducted by the Centre for English Language Education and Communication Research in Hong Kong where 289 textbooks were reviewed for gender bias. The study found that of “some 32,000 gender-specific references in the textbooks, 71% were to males” (p. 354). The study also found that stereotypical attributes such as crying, strange behaviour, overeating and weakness were assigned to female characters whereas courageousness was assigned to male characters. McGrath pointed out that concern over gender balance in EFL textbooks was still very relevant in 2004. He did, however, also show reservation about the pedagogical importance of gender bias in textbooks and was not entirely convinced there was a correlation between gender-biased textbooks and affected learning. He warned that we could not assume there was a “link between identification with, say, images or ‘characters’ and learning” (pp. 352-353). In contrast to McGrath’s hesitation to link biased texts to affected learning, Allyson Julé (2004) stated if “ESL girls are not given or do not claim adequate access to classroom talk, this must impact on their learning of English” (p. 27). Yasemin Bayyurt and Lia Litosseliti (2006) felt there was a link between how learners felt about teaching materials and activities and language acquisition. They stated

“[m]otivation for learning a foreign language, including learners’ attitudes towards the foreign language, plays an important role in female and male students’ learning in L2 classrooms” (p. 85). Whether gender-biased texts affect learning seems nearly impossible to prove but

research during the past four decades continually finds evidence that gender bias still exists in EFL textbooks.

2.3 Foreign Language Textbook Dialogues

How important is it to investigate gender bias in EFL textbook dialogues? Martha Jones, Catherine Kitetu and Jane Sunderland (1995) stated “dialogues are of considerable potential

value in providing different types of language learning opportunities” (p. 4). Jones, Kitetu and Sunderland further stated that dialogues served several purposes. Dialogues provided a model of the target language in terms of language form and social context in which the target language should be used. While some might question whether practice makes perfect, it is the authors’ general belief that practice provides valuable opportunity to train pronunciation and other pragmatic aspects of speaking the target language as well as provides social context in how the language is to be used in conversations. Jones, Kitetu and Sunderland (1995) also addressed the issue of inclusiveness versus exclusiveness in the classroom and its effect on motivation and learning stating that “a negative cognitive influence . . . may be loss of interest on the part of those who are discoursally marginalised” (p. 7).

Jones, Kitetu and Sunderland (1995) have analyzed three ESL textbooks which were published between 1987 and 1994. They found that there was some gender bias in the textbook dialogues but on the whole, the bias was not extreme. In the textbook published in 1987, female characters rated higher in words used (302 versus 248) and initiated

conversations more often than male characters (five versus four). Male characters however had an average of 27.5 words spoken per male character whereas female characters averaged 23.2 words per female character. While the female characters were over-represented in two of these three typologies, the differences were not great. In the 1993 textbook, the findings were similar and did not show any significant gender bias. In the textbook published in 1994, female characters once more used more words (632 versus 501) and initiated more

conversations (6 versus 3). Male characters however averaged 50.1 words spoken per male character compared to an average of 31.6 words spoken by female characters and thus were more “verbally visible” (p. 16). Jones, Kitetu and Sunderland (1995) concluded “gender differences found are too small either way to be significant. This is encouraging – but it would be interesting to establish why the differences were small” (p. 17). They further concluded that a qualitative study might have revealed other researched areas of discourse roles such as occupation and social roles which may have given another picture of gender bias.

As Sunderland had suggested (1998), it is impossible to predict how a biased text will affect learning. She did however address the issue of how a biased textbook might provide an unequal amount of speaking exercises for female and male characters. Sunderland (2000) referred to a textbook from 1977, Functions of English, which featured a dialogue designed to practice initiating a conversation. While the purpose of the exercise was to initiate

conversation, it was only a male character who initiated the conversations. Even though this textbook is outdated, it is an example of how dialogues might exclude speaking practice opportunities for girls or boys depending on how the dialogues are designed and whether girls and boys are willing to “cross” gender and practice both dialogues for female and male characters. In this particular example, if students were unwilling to take on the other gender’s role in the speaking exercise, it would imply that boys would have the advantage of practicing initiating conversations.

Sofia Poulou (1997) conducted a quantitative study of sexism looking at two Greek as a foreign language textbooks for adults. She looked at the number of utterances and words used by female characters and male characters. In one of the textbooks, the male characters were allocated 914 utterances and words in the dialogues compared to 801 allocated to female characters. In other words, the male characters accounted for 53% of the utterances and words in the dialogues and female characters accounted for 47%. In the second textbook the male character was allocated 49% of the utterances and words in the dialogues whereas the female character was allocated 51%. The study also looked at the initiation and closing of dialogues by female and male characters and the type of words used. The first textbook showed that male characters initiated a dialogue 63% of the time compared to 37% of the time for the female characters. Male characters finished 65% of the dialogues compared to 35% for the female characters. There was little difference between female and male characters in the second textbook. The third investigation was qualitative and looked at the types of words being used and how they were used. Poulou (1997) noted that female characters often made requests or asked for information whereas male characters often provided directives or

information. In a classroom situation where a teacher might be likely to ask boys to read male parts and girls to read female parts, it may be that boys rarely practice the language function of making requests and girls rarely practice the function of initiating a conversation or providing information. Poulou (1997) warned that if both boys and girls “do not perform the same language functions in similar contexts […] students will possibly be familiar only with those functions and styles they come across while reading” (p. 72). Poulou (1997) concluded her study stating:

It is surely worth making an attempt to ensure a decent representation of the two sexes and not to allow language learners to be disadvantaged by discrepancies in the verbal behaviour between female and male textbook characters. (p. 72)

If textbook dialogues have more male characters or more words allocated to male characters, does this mean that boys will have more practice opportunities? While Poulou might support this notion and argue that the marginalization of one gender in dialogues might have cognitive consequences, a study conducted in a German classroom offers some interesting findings. Sunderland (2000) found that girls could take on male character speaking exercises but boys were unwilling to take on girl character speaking exercises. Sunderland observed that a teacher during a German lesson asked for two male volunteers to read a dialogue featuring two male characters. When no boys volunteered, two girls volunteered and read the male character parts. In an interview with the boys after the lesson, it became evident that the boys were not comfortable reading female character parts of a dialogue and said they would have been laughed at if they had read the female parts. Sunderland (2000) noted that “girls can ‘cross’ gender boundaries with impunity, whereas boys cannot . . . it is most definitely not OK for them to ‘become’ girls, even temporarily, strategically and jokily” (p. 168). This would imply that girls had an advantage over boys in terms of practicing speaking via prescribed speaking exercises as they appeared to be more willing to take on both gender roles during a speaking exercise.

The research on textbook dialogues suggests that if there is gender bias, this may exclude some learners. Research points to the importance of motivation and inclusiveness in terms of language acquisition but whether gender-biased dialogues actually exclude some learners has not been proven. Also, it is important to recognize that while a dialogue may over-represent one gender in a quantitative analysis another gender may be over-represented when analysing the results qualitatively.

3. Method

3.1 Selection of Textbooks

For this study the following four series of EFL textbooks for secondary school were chosen:

Happy, Time, What’s Up?, and Wings Base Book.

Time and Wings were chosen because they are currently being used at our partner schools.

Happy and What’s Up? were chosen because they are examples of textbooks published in the 2000’s and could be considered more progressive in terms of gender. Another important factor in the choice of textbooks was that they represent a total of three different publishers which we feel provides a broader sampling of textbook styles. Workbooks and teacher guides related to the textbooks were not included in the analysis.

The textbook series Happy, Time and What’s Up? each consist of three books which cover grades 7, 8 and 9. Wings, however, consists of four textbooks which means that there is also a textbook for grade 6. Since there are no dialogues in Wings 9, it was excluded in favour of

Wings 6. In other words, a total of twelve textbooks were included in the study.

3.2 Procedure

In the choice of method, we looked at how earlier textbook studies have been conducted. As mentioned earlier, Wright (1998) conducted a qualitative study of textbooks in physics used in Sweden where she focused on language use, symbolism and several other aspects of gender portrayal. Jones, Kitetu and Sunderland (1995) have also focused on gender bias and have investigated textbooks using a different method. In their study of dialogues in ESL textbooks in England they used a quantitative method where they counted the number of male and female characters, the number of times they initiated dialogues, the number of turns taken, and the number of words spoken by female and male characters. Porreca (1984) also used a quantitative method in her study of gender in ESL textbooks. As Porreca (1984) and Jones, Kitetu and Sunderland (1995), we also chose to use a quantitative method. We recognize that

a qualitative method could give a different picture of gender bias in textbooks compared to a quantitative method. Several studies in fact have used both qualitative and quantitative

methods while looking at different aspects of gender bias in textbook dialogues. One example is Poulou’s study from 1997. As mentioned earlier, Poulou found that in some cases female characters were over-represented quantitatively at the same time as male characters dominated qualitatively. In other words, female and male characters had different roles in the dialogues. Another alternative could be to include assertiveness, that is, if there are any differences between female and male characters in how they express themselves. The focus in this type of study would then be about representation rather than over-representation. Representation in this sense refers to how female and male characters are depicted in a textbook.

Over-representation refers to when one gender is treated unfairly compared to another gender. Further investigations might include a qualitative method to gain further insight into gender bias.

Furthermore, even though the quantitative method is limited in its capacity for exploration and is not always preferable to use when the aim is to uncover the underlying reasons for an existing phenomenon (Dörnyei, 2007), the quantitative method suited our purpose to map gender bias in EFL textbooks. If the focus had been on the reasons for gender bias in EFL textbooks, qualitative interviews with the authors and/or publishers would have been

preferable. However, our focus was to investigate if there is any over-representation of female or male characters.

Creswell (2005) mentions that the focus of an investigation should not be too broad in order to be feasible. We chose therefore to restrict our study to quantitative and nominal data. Quantitative research is described by Creswell (2005) as a type of research in which specific questions are used and numeric data is collected whereas qualitative research is based on more broad and general questions. Moreover, the author writes that quantitative investigations are conducted “in an unbiased, objective manner” (p. 39) while qualitative research is

conducted in a “subjective, biased manner” (p. 39). However, Dörnyei (2007) points out that it is very problematic to separate the two approaches in that way since it is not possible to completely exclude the basic sources of variation to which the individual researcher and the respondents contribute. Irrespective of the chosen method, in all types of investigations the researcher needs to be aware of the influence their own views, values and experiences have on them.

The first step in the analysis was to identify the dialogues in the selected textbooks and to choose what typologies to investigate. Four different typologies were chosen to illuminate gender bias in the identified dialogues and they were based on Jones, Kitetu and Sunderland’s (1995) study of ESL textbooks in England. Quantitative data was compiled in terms of the verbal dominance by counting how many words were spoken by girls and how many words were spoken by boys and by looking at the number of conversational turns each female and male character had. The other two typologies were dialogue initiations and the number of male and female characters in the texts. The data for each dialogue, textbook and textbook series were thereafter summarized in tables in order to make the results clear for the reader. Those tables are to be found in the appendices where each textbook is presented in its own appendix. The analysis was not focused on in what way or to what extent the textbooks contributed to the learning of English. The analysis was instead focused on the above-mentioned aspects of gender bias.

For the purpose of counting the number of words used by female, male and neutral characters, we made a few specifications of what was counted as one word. If a word was expressed as a number such as 48, it was counted as one word. All contractions such as I’ve, don’t, we’ve were counted as one word. If a number was expressed as one fifty, it was counted as two words. Furthermore, if a word was hyphenated such as good-looking, it was counted as one word.

The textbooks consist of different types of dialogues. There are mixed-gender and same-gender dialogues as well as dialogues between a neutral character and a female or male character. Mixed-gender dialogues include characters of more than one gender while same-gender dialogues only include characters of one same-gender. The third type of dialogue which includes a neutral character was counted as mixed-gender dialogues. The neutral character will always represent something that is neither female nor male and could therefore be argued to be another gender. In addition, the textbook series Wings has two different types of

dialogues: dialogues in English and practice speaking exercises in Swedish. The practice speaking exercises are in Swedish with the intention that students will first translate the dialogues and then practice speaking using their translations. We have used the Swedish words in our data as it is not possible to anticipate how many words a student translation would include.

In the tables the results are presented in both absolute terms and in percentage. It is important to be aware of the fact that the numbers were small in certain cases so the percentages may have given a false impression of the over-representation. In the analysis, absolute terms were sometimes used instead of percentages when we felt this provided a truer picture of the over-representation. We chose to round off the percentage using one or two decimal points since there are a few times when there are small differences that would not be visible when using integers. In some cases we rounded the numbers up or down to make the percentage 100 when the sum was 99.9 or 100.1 percent.

4. Results

The findings for our research question “do EFL textbook dialogues over-represent female characters or male characters” is discussed below. Time, Wings, Happy and What’s Up? are discussed separately and findings include discussions about the following four typologies within the textbook series and the individual textbooks:

• Initiating a dialogue • Turns taken

• Number of characters • Number of words used

All raw data can be found in the Appendices 1-16.

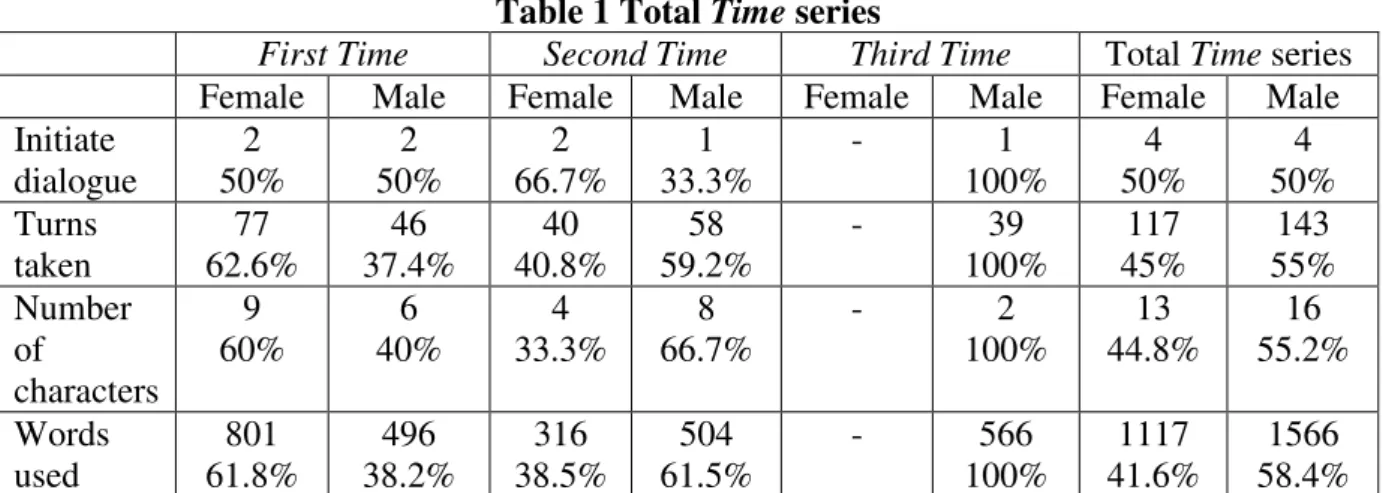

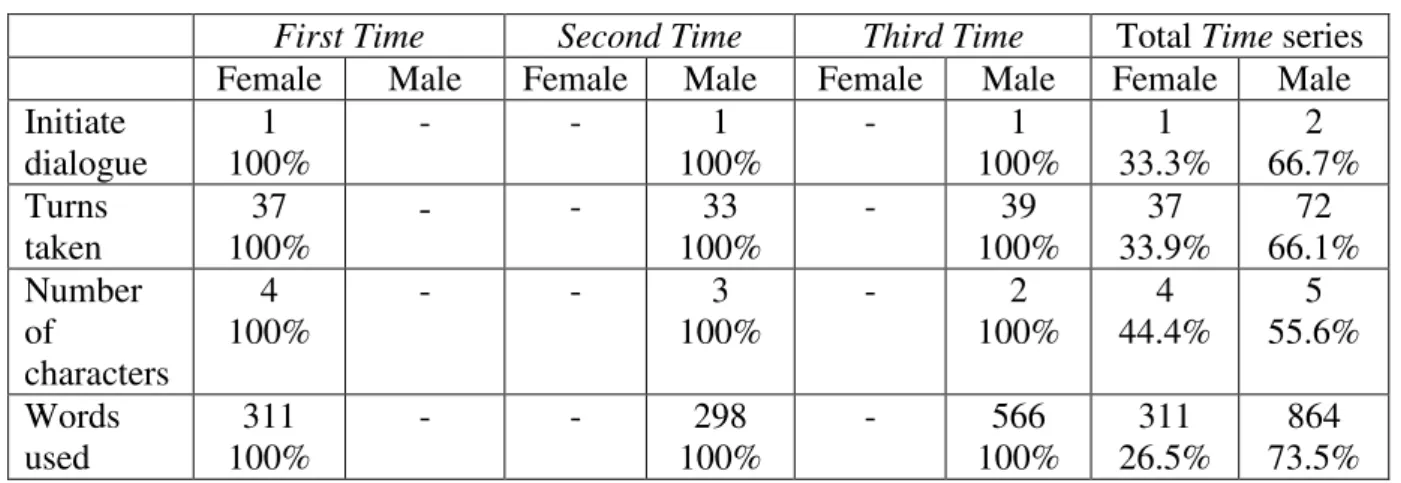

4.1 Textbook Series Time

The textbook series Time consists of a total of eight different dialogues of which five are mixed-gendered dialogues and three are same-gendered. The results from the study of the textbook series, which are summarized in Table 1 below, show that male characters are over-represented in three of the four typologies whereas female and male characters are equal in terms of the fourth typology. Since the male characters are over-represented in a majority of the typologies, we define this textbook series as being biased in favour of male characters. In addition to the summary of the results for the entire series, Table 1 also shows the results for each individual textbook and typology. The findings from the individual textbooks show that

First Time is female dominated in three of the four typologies while Second Time is male dominated in three of the four typologies. Third Time consists of only one dialogue which is male and therefore over-represents male characters.

Beginning with initiation, female and male characters begin an equal number of dialogues when all the dialogues from the series are summarized and there are no significant differences between the individual textbooks. Looking at the second typology, male characters are over-represented and have 26 (22.2%) more conversational turns than the female characters in the

entire series. In this typology however, there are differences between the three textbooks. In

First Time female characters are over-represented and have 62.6% of the turns taken compared to 37.4% for male characters. In Second Time on the other hand, male characters are over-represented accounting for 59.2% of the turns taken compared to 40.8% for female characters. Moreover, in Third Time there is only one male dialogue which means there are no conversational turns allocated to female characters.

As shown in Table 1, in the entire textbook series there are thirteen female characters

compared to sixteen male characters. Worth pointing out concerning this third typology is that of a total of fifteen characters in First Time, 60% are female and 40% male. Second Time on the other hand has the opposite numbers with almost 67% of the characters being male and 33% female. As mentioned before, in Third Time there is only one male same-gender

dialogue which includes two characters. Turning to the fourth and last typology, ‘words used’, male characters are allocated more words than female characters (1566 words compared to 1117 words). As with ‘turns taken’ and ‘number of characters’, First Time over-represents female characters whereas Second Time over-represents male characters.

Table 1 Total Time series

First Time Second Time Third Time Total Time series Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Initiate dialogue 2 50% 2 50% 2 66.7% 1 33.3% - 1 100% 4 50% 4 50% Turns taken 77 62.6% 46 37.4% 40 40.8% 58 59.2% - 39 100% 117 45% 143 55% Number of characters 9 60% 6 40% 4 33.3% 8 66.7% - 2 100% 13 44.8% 16 55.2% Words used 801 61.8% 496 38.2% 316 38.5% 504 61.5% - 566 100% 1117 41.6% 1566 58.4%

It is also interesting to look at the results from the mixed-gender dialogues which are summarized in Table 2. The mixed-gender dialogues include dialogues where female and male characters are interacting with each other. In the entire textbook series, the absolute terms show a rather balanced allocation of initiation, turns taken, characters and words used. However, in three of the four typologies female characters are somewhat over-represented. It is worth pointing out that the greatest differences were found in Second Time where the female characters had about 60% of the turns taken and words used.

Table 2 Summary of mixed-gender dialogues in the Time series

First Time Second Time Third Time Total Time series Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Initiate dialogue 1 33.3% 2 66.7% 2 100% - - - 3 60% 2 40% Turns taken 40 46.5%

53.5%

46

40 61.5% 25 38.5% - - 80 53% 71 47% Number of characters 5 45.5% 6 54.5% 4 44.4% 5 55.6% - - 9 45% 11 55% Words used 490 49.7% 496 50.3% 316 60.5% 206 39.5% - - 806 53.4% 702 46.6%In Table 3 the results from the three same-gender dialogues are shown. As presented, each individual textbook consists of one same-gender dialogue of which one is between female characters and two between male characters.

Table 3 Summary of same-gender dialogues in the Time series

First Time Second Time Third Time Total Time series Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Initiate dialogue 1 100% - - 1 100% - 1 100% 1 33.3% 2 66.7% Turns taken 37 100%

-

- 33 100% - 39 100% 37 33.9% 72 66.1% Number of characters 4 100% - - 3 100% - 2 100% 4 44.4% 5 55.6% Words used 311 100% - - 298 100% - 566 100% 311 26.5% 864 73.5%In summary, in the entire Time series and when all the dialogues are summarized, male characters are over-represented in the number of turns taken, number of characters and words used while female and male characters are equal in terms of initiation.

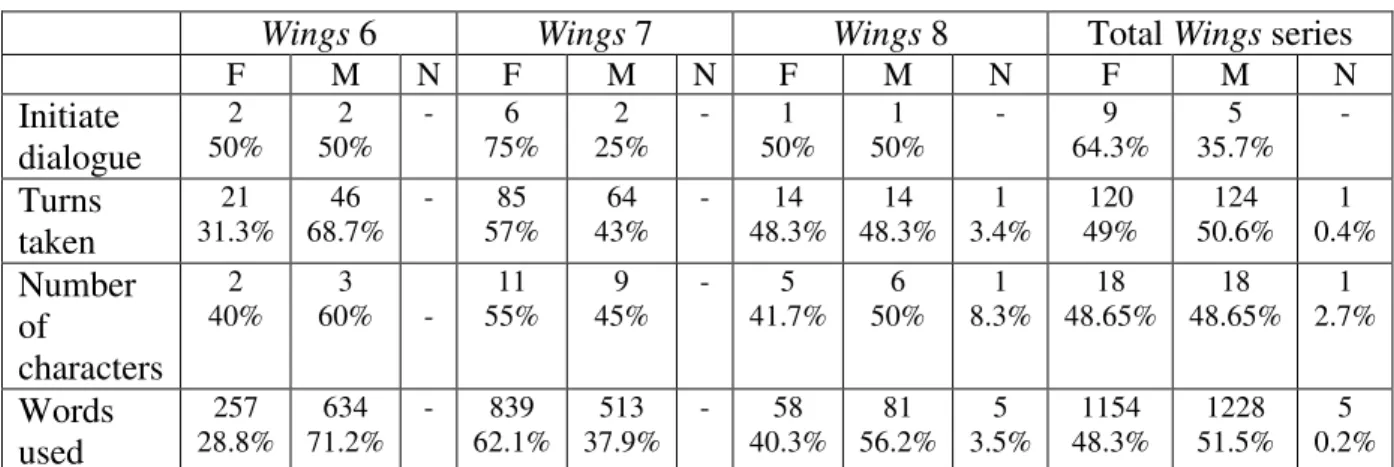

4.2 Textbook Series Wings

Wings consists of a total of fourteen dialogues and speaking exercises of which eleven are mixed-gendered dialogues and three are same-gendered. The results from the study of the

textbook series show that male characters are slightly over-represented in two of the four typologies whereas female characters are over-represented in one typology (see Table 4). The results from the study of the individual textbooks show that male characters are

over-represented in Wings 6 in three typologies and in Wings 8 in two typologies. Female characters are over-represented in Wings 7 in all four typologies.

Looking closer at the different typologies, we see that the textbook series tends to use female characters to initiate the textbook dialogues. As shown in Table 4 nine (64.3%) of the

conversations are initiated by female characters. Regarding the second typology ‘turn taking’ the textbook series shows no significant over-representation but Wings 6 shows that male characters have more than twice as many conversational turns. Wings 7 shows the opposite where female characters have twenty-one more turns than male characters. The third

typology, ‘number of characters’, shows no significant over-representation in the entire series or in any of the individual textbooks. The last typology ‘words used’ shows a slight over-representation in words allocated to male characters in the textbook series as a whole but in the individual textbooks there is significant over-representation. In Wings 6 male characters are allocated 634 words compared to 257 words allocated to female characters. In Wings 8 there are also more words allocated to male characters (81 words compared to 58 words). In

Wings 7, however, female characters are allocated 839 words whereas male characters are only allocated 513.

Table 4 Total Wings series

Wings 6 Wings 7 Wings 8 Total Wings series

F M N F M N F M N F M N Initiate dialogue 2 50% 2 50% - 6 75% 2 25% - 1 50% 1 50% - 9 64.3% 5 35.7% - Turns taken 21 31.3% 46 68.7% - 85 57% 64 43% - 14 48.3% 14 48.3% 1 3.4% 120 49% 124 50.6% 1 0.4% Number of characters 2 40% 3 60% - 11 55% 9 45% - 5 41.7% 6 50% 1 8.3% 18 48.65% 18 48.65% 1 2.7% Words used 257 28.8% 634 71.2% - 839 62.1% 513 37.9% - 58 40.3% 81 56.2% 5 3.5% 1154 48.3% 1228 51.5% 5 0.2% F = Female, M = Male, N = Neutral

The results from the mixed-gender dialogues are shown in Table 5. In both Wings 6 and

characters are over-represented in two typologies. The most significant over-representation occurs in the typology ‘initiate dialogue’ whereby female characters begin eight of eleven dialogues.

Table 5 Summary of mixed-gender dialogues in the Wings series

Wings 6 Wings 7 Wings 8 Total Wings series

F M N F M N F M N F M N Initiate dialogue 2 100% - - 5 71.4% 2 28.6% - 1 50% 1 50% - 8 72.7% 3 27.3% - Turns taken 21 51.2% 20 48.8% - 70 52.2% 64 47.8% - 14 48.3% 14 48.3% 1 3.4% 105 51.5% 98 48% 1 0.5% Number of characters 2 66.7% 1 33.3% - 10 52.6% 9 47.4% - 5 41.7% 6 50% 1 8.3% 17 50% 16 47.1% 1 2.9% Words used 257 50.5% 252 49.5% - 547 51.6% 513 48.4% - 58 40.3% 81 56.2% 5 3.5% 862 50.3% 846 49.4% 5 0.3% F = Female, M = Male, N = Neutral

The summary of the three same-gender dialogues is shown in Table 6 below. The Wings series features two male same-gender dialogues in Wings 6 and one female same-gender dialogue in Wings 7.

Table 6 Summary of same-gender dialogues in the Wings series

Wings 6 Wings 7 Wings 8 Total Wings

series Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Initiate dialogue - 2 100% 1 100% - - - 1 33.3% 2 66.7% Turns taken - 26 100% 15 100% - - - 15 36.6% 26 63.4% Number of characters - 3 100% 2 100% - - - 2 40% 3 60% Words used - 382 100% 292 100% - - - 292 43.3% 382 56.7%

In summary, the textbook series does not show any largely significant over-representation but the individual textbooks do. Wings 6 and Wings 8 over-represent male characters whereas

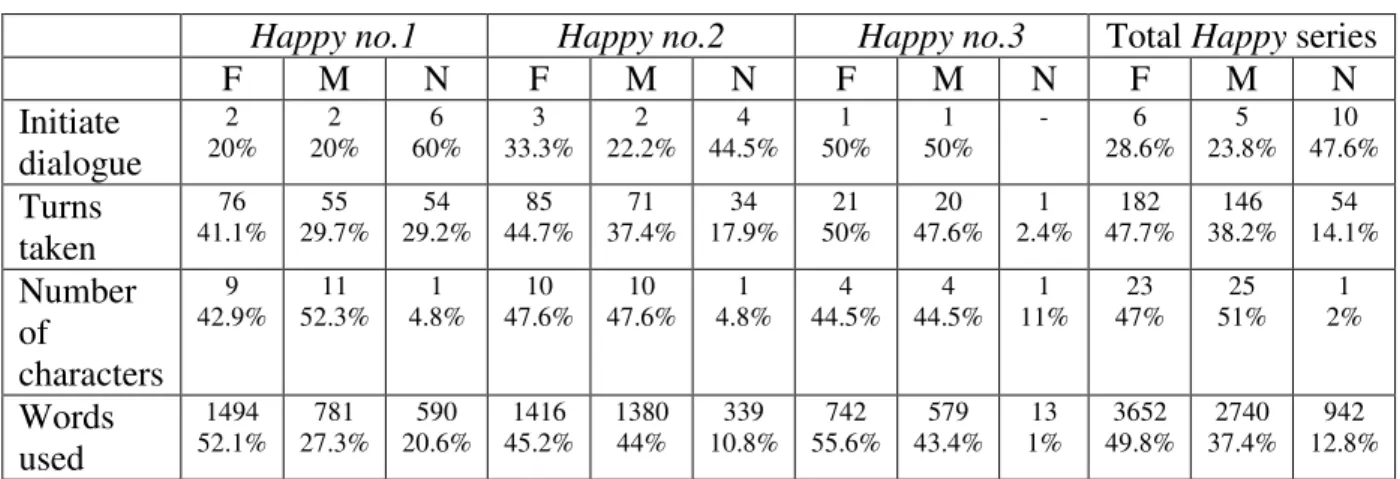

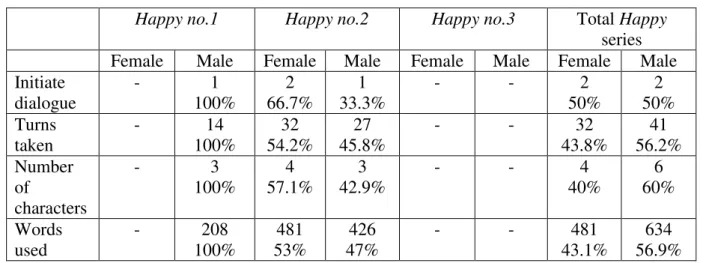

4.3 Textbook Series Happy

The textbook series Happy consists of a total of twenty-one dialogues of which seventeen are mixed-gendered dialogues and four are same-gendered. In this textbook series there are not only female and male characters but also a neutral character called ‘Happy’ who takes part in eleven of the dialogues. The results from the study of the textbook series Happy are

summarized in Table 7. The table shows that in the entire Happy series female characters are over-represented in all of the investigated typologies except for the number of characters. The findings from the individual textbooks show that Happy no.1 over-represents female

characters in two typologies and male characters in one typology. The second textbook represents female characters in three of the four typologies. The last textbook somewhat over-represents female characters in two typologies.

Concerning the first typology, initiation, the neutral character ‘Happy’ begins almost half of the dialogues (47.6%). There is no significant difference between female and male characters in the textbook series as a whole or in any individual textbook. In the findings from the second typology there are on the other hand significant differences in one of the books. In

Happy no.1, female characters are allocated 76 (41.1%) of the conversational turns whereas male characters are only allocated 55 (29.7%). In the next textbook, Happy no.2, there is only a slight difference but still in favor of the female characters (85 turns taken compared to 71 turns taken). In the third textbook the difference is insignificant. As illustrated in Table 7, in the entire textbook series female characters are over-represented and account for 47.7% of the conversational turns whereas male characters account for 38.2% of the conversational turns.

Turning to the number of characters, there is only a slight difference in favor of the boys (25 characters compared to 23) in the entire Happy series. Moreover, there are no significant differences in any individual textbook. The fourth and last typology shows that female characters are over-represented and account for almost half of the allocated words whereas male characters account for 37.4% of the words used. The neutral character ‘Happy’

accounted for almost 13% of the words used. Looking at the individual textbooks, Happy no.1 shows the greatest difference where female characters are allocated almost double the amount of words compared to male characters (1494 words compared to 781 words).

Table 7 Total Happy series

Happy no.1 Happy no.2 Happy no.3 Total Happy series

F M N F M N F M N F M N Initiate dialogue 2 20% 2 20% 6 60% 3 33.3% 2 22.2% 4 44.5% 1 50% 1 50% - 6 28.6% 5 23.8% 10 47.6% Turns taken 76 41.1% 55 29.7% 54 29.2% 85 44.7% 71 37.4% 34 17.9% 21 50% 20 47.6% 1 2.4% 182 47.7% 146 38.2% 54 14.1% Number of characters 9 42.9% 11 52.3% 1 4.8% 10 47.6% 10 47.6% 1 4.8% 4 44.5% 4 44.5% 1 11% 23 47% 25 51% 1 2% Words used 1494 52.1% 781 27.3% 590 20.6% 1416 45.2% 1380 44% 339 10.8% 742 55.6% 579 43.4% 13 1% 3652 49.8% 2740 37.4% 942 12.8%

F = Female, M = Male, N = Neutral

In Table 8 the results from the mixed-gender dialogues are presented. In three of the four typologies, female characters are represented whereas male characters are

over-represented in the fourth. Noticeable is that the most significant differences are to be found in

Happy no.1 and in the typologies ‘turns taken’ and ‘words used’ where the female characters are over-represented.

Table 8 Summary of mixed-gender dialogues in the Happy series

Happy no.1 Happy no.2 Happy no.3 Total Happy series

F M N F M N F M N F M N Initiate dialogue 2 22.2% 1 11.1% 6 66.7% 1 16.7% 1 16.7% 4 66.6% 1 50% 1 50% - 6 28.6% 5 23.8% 10 47.6% Turns taken 76 44.4% 41 24% 54 31.6% 53 40.5% 44 33.6% 34 25.9% 21 50% 20 47.6% 1 2.4% 182 47.7% 146 38.2% 54 14.1% Number of characters 9 50% 8 44.4% 1 5.6% 6 46.2% 6 46.2% 1 7.6% 4 44.5% 4 44.5% 1 11% 23 47% 25 51% 1 2% Words used 1494 56.2% 573 21.6% 590 22.2% 935 42% 954 42.8% 339 15.2% 742 55.6% 579 43.4% 13 1% 3652 49.8% 2740 37.4% 942 12.8%

F = Female, M = Male, N = Neutral

In Table 9 the results from the gender dialogues are illustrated. There are four same-gender dialogues in total of which two are female and two male. Three of these dialogues are found in Happy no.2. When the results from the same-gender dialogues are summarized, they show an over-representation of male characters in terms of turns taken, number of characters and words used.

Table 9 Summary of same-gender dialogues in the Happy series

Happy no.1 Happy no.2 Happy no.3 Total Happy series Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Initiate dialogue - 1 100% 2 66.7% 1 33.3% - - 2 50% 2 50% Turns taken - 14 100% 32 54.2% 27 45.8% - - 32 43.8% 41 56.2% Number of characters - 3 100% 4 57.1% 3 42.9% - - 4 40% 6 60% Words used - 208 100% 481 53% 426 47% - - 481 43.1% 634 56.9%

To summarize, in the entire Happy series female characters are over-represented in the number of dialogue initiations, turns taken and words used while male characters are over-represented in the number of characters.

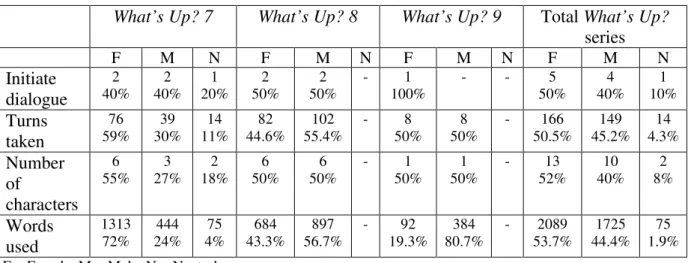

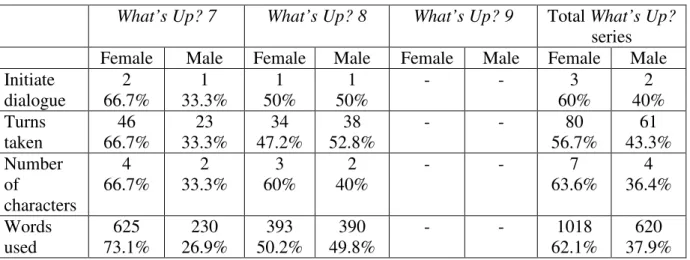

4.4 Textbook Series What’s Up?

What’s Up? consists of ten dialogues of which five are mixed-gendered dialogues and five are same-gendered. The findings for the textbook series show that female characters are over-represented in all four typologies (see Table 10). Findings from the individual textbooks show that female characters are over-represented in What’s Up? 7 in three typologies and male characters are over-represented in What’s Up? 8 in two typologies. In What’s Up 9, female characters are over-represented in one typology as are male characters.

For the typology ‘initiate dialogue’, the textbook series shows no significant

over-representation. While What’s Up? 9 does show that female characters initiate 100 % of the dialogues, there is only one dialogue in this textbook. Regarding how many turns female and male characters take in the dialogues, there is some over-representation for both female and male characters. In the entire textbook series, female characters account for 166 turns taken whereas male characters account for 149 and neutral characters account for 14. In What’s Up?

7 female characters account for 59% of the turns taken as opposed to 30% for male characters. In What’s Up? 8 however, female characters only account for 44.6% of the turns and male characters for 55.4%.

Regarding the number of characters assigned to each gender, there are thirteen female

characters in the textbook series and ten male characters. In What’s Up? 7 there is the greatest difference with female characters totaling six and male characters totaling three. When

looking at the word count, the entire series favors female characters and allots 2089 words to female speaking roles compared to 1725 to male speaking roles. Looking closer at the individual textbooks, the representation looks a bit different. What’s Up? 7 shows females dominate by 72 % compared to 24% but What’s Up? 8 shows the opposite with male characters accounting for 56.7% of the words compared to 43.3%. The difference is even greater in What’s Up? 9 with male characters accounting for 80.7% of the words spoken in dialogues compared to 19.3% for female characters.

Table 10 Total What’s Up? series

What’s Up? 7 What’s Up? 8 What’s Up? 9 Total What’s Up? series F M N F M N F M N F M N Initiate dialogue 2 40% 2 40% 1 20% 2 50% 2 50% - 1 100% - - 5 50% 4 40% 1 10% Turns taken 76 59% 39 30% 14 11% 82 44.6% 102 55.4% - 8 50% 8 50% - 166 50.5% 149 45.2% 14 4.3% Number of characters 6 55% 3 27% 2 18% 6 50% 6 50% - 1 50% 1 50% - 13 52% 10 40% 2 8% Words used 1313 72% 444 24% 75 4% 684 43.3% 897 56.7% - 92 19.3% 384 80.7% - 2089 53.7% 1725 44.4% 75 1.9% F = Female, M = Male, N = Neutral

Table 11 shows that the presence of a neutral character does not affect the overall balance between female and male characters in the textbook series. However, in What’s Up? 7 the neutral character accounts for 23.3% of turns taken compared to 26.7% for male characters. This contributes to the over-representation of female characters over male characters.

Table 11 Summary of mixed-gender dialogues in the What’s Up? series

What’s Up? 7 What’s Up? 8 What’s Up? 9 Total What’s Up? series F M N F M N F M N F M N Initiate dialogue - 1 50% 1 50% 1 50% 1 50% - 1 100% - - 2 40% 2 40% 1 20% Turns taken 30 50% 16 26.7% 14 23.3% 48 42.9% 64 57.1% - 8 50% 8 50% - 86 45.7% 88 46.8% 14 7.5% Number of characters 2 40% 1 20% 2 40% 3 42.9% 4 57.1% - 1 50% 1 50% - 6 42.85% 6 42.85% 2 14.3% Words used 688 70.4% 214 21.9% 75 7.7% 291 36.5% 507 63.5% - 92 19.3% 384 80.7% - 1071 47.6% 1105 49.1% 75 3.3% F = Female, M = Male, N = Neutral

Same-gendered dialogues are summarized in Table 12. There is over-representation of female characters in all four typologies. This may not be surprising as there are three same-gendered dialogues featuring females compared to two same-gendered dialogues featuring males.

Table 12 Summary of same-gender dialogues in the What’s Up? series

What’s Up? 7 What’s Up? 8 What’s Up? 9 Total What’s Up? series Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Initiate dialogue 2 66.7% 1 33.3% 1 50% 1 50% - - 3 60% 2 40% Turns taken 46 66.7% 23 33.3% 34 47.2% 38 52.8% - - 80 56.7% 61 43.3% Number of characters 4 66.7% 2 33.3% 3 60% 2 40% - - 7 63.6% 4 36.4% Words used 625 73.1% 230 26.9% 393 50.2% 390 49.8% - - 1018 62.1% 620 37.9%

To summarize, the entire textbook series over-represents female characters. What’s Up? 7 represents female characters in three of the four typologies, What’s Up? 8

represents male characters in two typologies and What’s Up? 9 shows very significant over-representation of male characters in one typology.

5. Analysis

The analysis will address in what quantitative ways EFL textbook dialogues over-represent female and male characters by looking at the four investigated typologies: initiating a dialogue, turns taken, number of characters and words allocated to male and female characters. It should be noted that we do not rank the four typologies in any order of importance or significance and due to the quantitative nature of this study, treat them as equally important. This analysis will also address a possible shift in gender-biased

representation in EFL textbook dialogues in textbooks published in the 1990’s compared to EFL textbooks published in the 2000’s.

When looking at the first typology ‘initiating a dialogue’, over-representation of female characters is significant in Wings but not significant in Time, Happy or What’s Up?. As mentioned earlier, Sunderland (2000) noted that a 1977 textbook featured only one male character in a speaking exercise for students to practice starting up a conversation. The implications were that girls did not have the opportunity to practice this language function. Today, it appears that the opposite is occurring with Wings 7 where 75% of the dialogues are initiated by females and 25% of the dialogues are initiated by males. In Happy, the neutral character ‘Happy’ accounts for ten out of twenty-one dialogue initiations. Depending on how a teacher handles these dialogues in the EFL classroom determines if the Happy series could be considered biased. In other words, in ten dialogues, the characters other than ‘Happy’ are female in five of the dialogues, male in one dialogue and mixed in four. If ‘Happy’ takes on the persona of the “other” gender, boys would gain five additional opportunities to practice initiation and girls would gain only one additional chance. While the neutral character ‘Happy’ might appear to promote equal opportunities for all learners to practice, ‘Happy’ does not necessarily achieve this. As Sunderland (1998) noted, teachers can use un-biased texts in biased ways and conversely use biased texts in un-biased ways.

Regarding the typology ‘turns taken’, Happy and What’s Up? allocate more conversational turns to female characters. This is true for both the series and the individual textbooks. While girls are given more opportunities to speak in the Happy series based on the number of female character turns, boys are not necessarily excluded as they may be assigned a neutral role. As

mentioned before, it is up to the teacher to ensure that the steering documents are followed and that equal opportunities to practice speaking are provided for all learners. In Time there is an over-representation of male characters in terms of turns taken. In the entire textbook series male characters have 26 more turns (22.2%) than female characters. However, it is worth noting that in First Time, female characters account for 62.6% of turns taken. If First Time is the only textbook within the series to be used, it could be important for educators to know that this individual textbook represents female characters even though the entire series over-represents male characters. As a textbook series, Wings shows little over-representation in terms of conversational turns but educators should know that in Wings 6 male characters take more than twice as many conversational turns as female characters. The reverse is true for

Wings 7 where female characters take 85 conversational turns compared to 64 for male characters. This imbalance may imply that one gender is less important than the other (Sadker & Zettleman, 2007).

Wings and Happy have succeeded in creating an equal balance in the number of female and male characters. What’s Up? and Time show over-representation but it is not extreme. If we look at the individual textbook What’s Up? 7 there are twice as many female characters as male characters (6 versus 3). It is worth mentioning that in Third Time there is only one dialogue which is between two men. The speaking opportunities for boys are limited to one dialogue. The speaking opportunities for girls are only available if girls are willing to take on a male role. One could wonder why the dialogue does not include a female role or a neutral role particularly when this could have prevented an overall over-representation of male characters in the textbook series.

When looking at words used, Wings allocates roughly the same amount of words to both female and male characters. Time on the other hand allocates more words to male characters than female characters (1566 words versus 1117 words). Happy and What’s Up? allocate more words to female characters. If we look closer at Time, male characters are over-represented by 449 words but again there was one male-only dialogue in Third Time which accounted for 566 words. The over-representation could have been avoided with the introduction of a mixed-gendered dialogue rather than a same-gendered dialogue in Third

Time. Whether a same-gendered dialogue excludes some learners in the classroom is not known. However, as Sunderland (2000) pointed out in her study of a German class, girls were

more than willing to take on male character roles and boys were unwilling to take on female character roles.

Even though the Wings series shows an equal allocation of words used, we see that Wings 6 allocates 71.2% of the words to male characters. If Sunderland’s findings hold true, this may not be as detrimental to girl learners in terms of speaking practice as first appears. In other words, if girls are willing to take on male character roles, the teacher can still assure equal opportunities in the classroom. However, the curriculum for compulsory schools strives to teach students the value of equality. This may be hard to achieve when teaching materials show over-representation of one gender. Female over-representation is present in First Time,

Wings 7, Happy no.1, Happy no.3, and What’s Up? 7. If boys are unwilling to take on female roles it may be hard to ensure equal speaking opportunities for boys. It could be worth

considering if this might also affect the scholastic performance of boys on tests such as the oral part of the National test in English.

Research conducted during the past forty years showed male over-representation was

prevalent in foreign language textbooks. Looking at the results from this study, it appears that male-dominated dialogues have been replaced by female-dominated dialogues. The oldest textbook series in our study, Time (1996 – 1998) over-represents male characters in three of the four typologies. The average over-representation in these three typologies is 28.5%. Wings (2001-2003) represents male characters in two of the four typologies. The average over-representation in these two typologies is 4.9%. Happy (2004 – 2006) over-represents female characters in three of the four typologies. The average over-representation is 26%. What’s

Up? (2004 – 2007) over-represents female characters in all four typologies with an average over-representation of 21.9%. In this limited study of four textbook series, we see that the shift from male-dominated dialogues to more female-dominated dialogues is correlated to the publication date. It is important to remember however that this study includes only four textbook series and is quantitative. We do not take into account qualitative data which may provide a different picture. In Poulou’s (1997) study where she investigated dialogues both quantitatively and qualitatively, she found that male dominated dialogues still prevailed. In other words, while females may have dominated quantitatively, males appeared to dominate qualitatively. She found that the function of language showed that men were providers of information and portrayed as knowledgeable whereas women were in need of information.

6. Conclusion

This study set out to investigate if EFL textbook dialogues over-represent female characters or male characters. This is a complex question. Our findings showed that two of the textbook series over-represented male characters and two of the textbook series over-represented female characters. Furthermore, within a specific textbook series, we found variations in the individual textbooks. One example is Wings, where the series over-represented male

characters but Wings 7 over-represented female characters. When we looked at one individual textbook we also found variations. For example, in Happy no.1, male characters were over-represented in the typology ‘number of characters’ but not in the other three typologies which over-represented female characters or were balanced. The overall rating for this textbook was that it favored female characters.

Interesting to highlight is that the series which over-represented male characters were published earlier than the two series which over-represented female characters. One reason may be overcompensation. Since the 1970’s research has shown that textbooks over-represent males. Also, as Öhrn (2002) and Björnsson (2005) pointed out, much focus has been placed on girls’ scholastic performance, level of participation in classroom interactions and

underachievement in mathematics and natural sciences. Perhaps this has contributed to an environment where the female gender is promoted more in textbooks today.

One pedagogical implication of our findings is that educators need to recognize the

complexity of textbook dialogues in terms of gender in order to ensure equal opportunities for both boys and girls to practice and learn English. Another implication is that educators need to be more critical of EFL textbooks. Again, 80% of EFL teachers in a study (Skolverket, 2006b) found textbooks to be the most important teaching material and assumed the textbooks upheld the goals in the curriculum. Our study, however, has shown that EFL textbooks do not always fulfill the requirements of the steering documents.

As future teachers we need to be cognizant of gender-biased teaching materials. It is our responsibility to ensure that all the teaching materials we use in the classroom provide an equal opportunity for learning for all students. We decide if a biased text will be used in a biased way or un-biased way. Another dimension of this is that we can determine which texts

are used and can, therefore, avoid texts which are not in accordance with the steering documents. Even though we as teachers have an enormous responsibility for upholding

equality, authors and publishers also have a responsibility to ensure that textbooks also uphold equality.

Further research in this area might include a qualitative study. One option is to expand the research of textbook dialogues to include conversational styles, character occupation and social status and language functions such as requesting information or providing information. This might reveal gender biases and stereotypical gender representation which may not necessarily show up in a quantitative study. Another area for future research might be

qualitative interviews with authors and publishers to investigate what guidelines, if any, they follow in order to ensure that their EFL textbooks are not biased.