Malmö University

Culture and Society

Urban Studies

Master Programme Leadership for Sustainability (SALSU)

Attitudes towards External Knowledge Sourcing &

Knowledge-Oriented Leadership

Exploring patterns of attitude and leadership within tech companies in Sweden in an

economy characterized by globalization and the fast pace of technological innovation.

Aaron Orman

Marko Tukic

Main field of study – Leadership and Organization

Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organization

Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organization for Sustainability (OL646E),

15 credits

Spring 2019

Supervisor: Ju Liu

Title

Attitudes Towards External Knowledge Sourcing & Knowledge-Oriented Leadership – Exploring patterns of attitude and leadership within tech companies in Sweden in an economy characterized by globalization and the fast pace of technological innovation.

Authors

Aaron Orman Marko TukicAbstract

External knowledge sourcing is not only an integral practice within knowledge management, its successful facilitation through leadership has a pressing importance for companies in order to stay innovative and thus competitive in an economic environment, shaped by the dominant and continuous influence of globalization and the increasingly fast pace of technological innovation. Hereby, only limited research has been conducted in the relation between knowledge-oriented leadership, knowledge management, and innovation.

This thesis is contextualized in the scientific discourse which concerns itself with the role of individual attitudes towards external knowledge sourcing, as well as the facilitating role of leadership towards changing individual attitudes. This thesis is, furthermore, also contextualized within the concepts of open innovation and absorptive capacity, which, respectively, are consequences of the spatial effects of globalization and the temporal effects of the fast pace of technological innovation.

Research Question: Facing the challenges of globalization and the fast-changing pace of technology,

what patterns between employee’s attitudes towards external knowledge acquisition and employee’s perceived leadership behaviors can be observed within tech companies in Sweden?

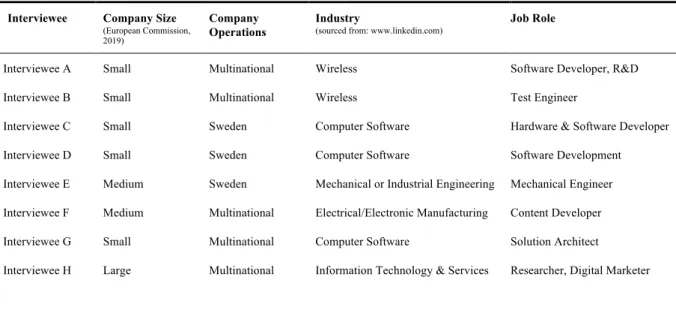

In order to answer the proposed research question, we conducted a qualitative research including nine semi-structured interviews with employees with a technical background in tech companies in Sweden, ranging from small to large companies and with local to multinational operations.

Our main findings represent a generally positive attitude towards external knowledge sourcing within our research scope, which relates with high levels of transformational leadership. Still, we were not able to explore the existence of knowledge-oriented leadership.

This thesis contributes to the body of knowledge management, innovation, and leadership research, as it provides a first look into previously identified research gaps, namely the impact of knowledge-oriented leadership and knowledge management on open innovation (Naqshbandi & Jasimuddin, 2018) and the missing connection of the three separate bodies: leadership, knowledge management, and innovation (Donate & de Pablo, 2015)

Key words: knowledge management, external knowledge sourcing, knowledge-oriented leadership,

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

1

1.1. Background 2

1.1.1. Importance of External Knowledge 2

1.1.2. Globalization & Fast Pace of Technological Change

and Innovation 2

1.1.3. Attitudes towards External Knowledge 4

1.2. Research Question 5

2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

5

2.1. Knowledge and Knowledge Management 6

2.2. Attitudes towards External Knowledge 7

2.2.1. Attitudes 8

2.2.2. Importance of Attitude Management in Relation to

External Knowledge 9

2.2.3. The “Not-Invented-Here Syndrome” as a consequence of

negative attitudes towards external knowledge 9

2.2.4. Measuring Attitudinal Expression 10

2.3. The Role of Leadership in Shaping Attitudes towards

External Knowledge 11

2.3.1. Transformational, Transactional and Passive-Avoidant Leadership 12

2.3.2. Knowledge-Oriented leadership 13

3. Methodology

14

3.1. Research Philosophy 14

3.2. Research Strategy and Approach 15

3.3. Methods 15

3.3.1. Semi-Structured Interview 16

3.3.2. Interview Guide 16

3.4. Content Analysis 17

3.5. Limitations 17

4. Presentation of the Objects of Study

18

5. Findings and Analysis

19

5.1. Attitudes towards External Knowledge 19

5.1.1. Preference for Internal Knowledge 19

5.1.2. Reluctance to External Collaboration 19

5.1.3. Competitive Importance of Internal Knowledge 20

5.1.4. Reluctance to Knowledge Sharing 21

5.1.5. Analysis of Findings on Attitudes towards External Knowledge 22

5.2. Perceptions of Leadership 23

5.2.1. Transformational Leadership 23

5.2.2. Transactional Leadership 25

5.2.4. Analysis of Findings on Perceptions of Leadership 25

6. Discussion

26

6.1. Attitudes towards External Knowledge in relation to

Open Innovation and Globalization 26

6.2. Perception of Leadership in relation to the Fast Pace of

Technological Innovation and Absorptive Capacity 28

6.3. Patterns between Attitudes towards External Knowledge and

Perceptions of Leadership 30

6.3.1. In relation to company size 30

6.3.2. In relation to breadth of company operations 31

7. Conclusion

31

7.1. Practical Implications 32 7.2. Further Research 328. References

33

9. Appendix

46

Table of Tables

Table 1

The transformational leadership continuum

13

Table 2

Presentation of interview subjects

18

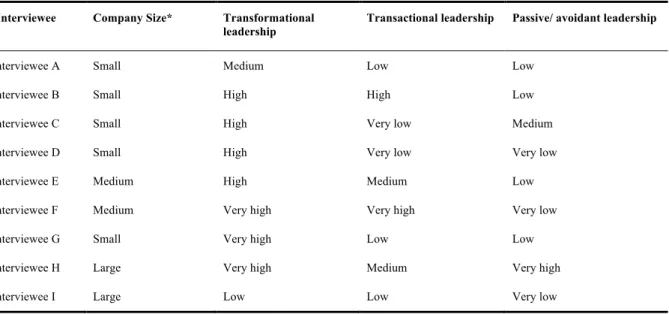

Table 3

Extent of employee perceptions of leadership

and company size

23

Table 4

Tendencies of leadership traits along the

transformational leadership continuum

1. Introduction

This thesis considers the topic of external knowledge sourcing as part of knowledge management practice and the importance of its facilitation through leadership in order for tech companies to stay competitive in an environment, shaped by the dominant and continuous influence of globalization and the increasingly fast pace of technological innovation.

Recent research points towards a research gap in this field, as only limited research has been done on the impact of knowledge-oriented leadership and knowledge management in relation to open innovation (Naqshbandi & Jasimuddin, 2018). Donate and de Pablo (2015) also point towards a gap in considering connections between three different bodies of literature, namely leadership, knowledge management, and innovation.

In order to contextualize our research topic, we join the scientific discourses which concern itself with the role of individual attitudes towards external knowledge sourcing, as well as the facilitating role of leadership towards changing individual attitudes. Furthermore, we will contextualize our analysis next to the concepts of open innovation and absorptive capacity, which, respectively, are perceived as a consequence of the spatial effects of globalization and the temporal effects of the fast pace of technological innovation.

The aim of our research is to identify patterns within a diverse set of Swedish tech companies – small to large firms, as well as firms with local to international operations –, in relation to their employees’ individual attitudes towards external knowledge sourcing and their employees’ individual perception of their respective leadership. Based on the scientific consensus on the essential importance of external knowledge sourcing for the survival of businesses, we will conclude with a set of practical insights, for example: the leadership behaviors perceived by employees who are most open to external knowledge. Furthermore, we will conclude with a set of suggestions for future research, in order to expose quantitative relevance for the patterns we encountered through our limited, qualitative research. The overall purpose of this research paper is, thus, to explore patterns between individuals’ attitudes towards external knowledge in relation to individuals’ perceptions towards leadership behaviours. This paper starts by providing the background for our research, thus, briefly explaining the importance of external knowledge sourcing for companies. Further, we explain the economic environmental forces, namely globalization and the fast pace of technological innovation, which urge companies to acknowledge external knowledge as a vital driver in order to stay competitive, and finally we briefly introduce which crucial role attitudes play with regards to knowledge management.

Within our theoretical framework and literature review, we first discuss the role of knowledge and knowledge management as the organizational mantle in which external knowledge sourcing is situated. In the following section, we will examine what attitudes in general are, the importance of managing attitudes, its implications on organizational performance, as well as the theoretical basis on how we measure attitudinal expressions. Next, we will discuss the role of leadership, specifically of the combination of both transformational and transactional leadership (knowledge-oriented leadership), as an enabling tool to foster knowledge management and to affect employee attitudes. After explaining our methodology and methods, we will present our findings in relation to our research question and subsequently discuss the common patterns we were able to identify. Those patterns will also be discussed in relation to the economic environmental challenges that companies face, such as globalization and the fast pace of technological innovation, as also with their respective antecedents; open innovation and absorptive capacity.

We conclude our paper with a final conclusion, including practical implications and suggestions for further research.

1.1. Background

For companies, knowledge serves as the most crucial resource as the effects of globalization and the fast pace of technological innovation drive the economy in to a “knowledge-based economy” (Thurow, 2000, p. 20). External knowledge sourcing in particular is a fairly new practice, which extends formerly internal R&D process by looking for knowledge outside the company borders (Chesbrough & Crowther, 2006). Sourcing for external knowledge comes with its challenges, as negative individual attitudes towards external knowledge can hijack its promised value with regards to innovating products and services more effectively and efficiently (Dolinska, 2018). Thus, individual attitudes and their management are crucial challenges companies face, when approaching external knowledge.

1.1.1. Importance of External Knowledge

The creation and distribution of knowledge is perceived as a central aspect for productivity and growth across companies. One cost-effective, time-efficient (Dolinska, 2018) and proven way (Antikainen, Mäkipää, & Ahonen, 2010; Ahonen & Antikainen, 2007) to anticipate the growing demands for innovative products and services, is by incorporating external knowledge, e. g. in collaborating with external professionals, customers, suppliers or other stakeholder throughout the whole innovation process (Antikainen, Mäkipää, & Ahonen, 2010; Chesbrough, Vanhaverbeke, & West, 2006; Dolinska, 2018).

Knowledge is a crucial driver for innovation and innovative products and services, moreover, are perceived to be of high strategic importance for companies (Pianta, 1988; Tyson, 1992; Scherer, 1992). Previously, internal research & development (R&D) departments were responsible for researching and initiating development of new and innovative products and services (Chesbrough & Crowther, 2006). The increasing mobility of the labour market and of knowledge has made it difficult for companies to generate satisfactory, innovative returns from internal R&D operations, as innovation, affected by globalization and the fast pace of technological innovation, has to be generated in complementary temporal and spatial dimensions. This change of spatial and temporal dimensions makes internal knowledge sourcing on its own less attractive and, as they urge companies to open up the innovation process to incorporate external knowledge (Mayer, 2010).

In conclusion, companies are increasingly urged to look beyond their own borders in order to source knowledge from the outside, in order to innovate more effectively and efficiently (Laursen & Salter, 2006). As mentioned, the newfound dependence on external knowledge sourcing is a direct consequence of economic environmental process such as globalization and the fast-changing pace of technological innovation.

1.1.2. Globalization & Fast Pace of Technological Change and Innovation

Today, companies find themselves amidst a “dynamic and globalized business environment” (Popa, Soto-Acosta, & Martinez-Conesa, 2017, p. 134). The constant emergence of new technologies is shaping our world and leading us to a state of globalization, whilst these technologies are turning the economy into a “knowledge-based economy” (Thurow, 2000, p. 20). Globalization implies drastic changes, especially for “economics, technology, and culture” (Stromquist & Monkman, 2014, p. 1) and pushes further “practices of free trade, private enterprise, foreign investment, and liberalized trade” (Stromquist & Monkman, 2014, p. 1).

Globalization

Globalization is a complex and multifaceted term with multiple angles of definition. Globalization was defined by Gibson-Graham (2006, p. 120) as “a set of processes by which the world is rapidly being integrated into one economic space […] promoted by an increasingly networked global telecommunications system”, thus having the effect to compress both time and space (Castells, 2010).

Furthermore, Giddens (1990, p. 64) defines globalization as “the intensification of world-wide social relations which link distant localities in such a way that local happenings are shaped by events occurring many miles away and vice versa”. Archibugi and Iammarino (2002, p. 99) regard to globalization as “a high (and increasing) degree of interdependency and interralatedness among different and geographically dispersed actors”.

As Stever and Muroyama (1988) state, technological change affects the structure of global industry as it introduced a severe transformation in the way that firms develop new products and services, and lead to the aforementioned interdependence among firms. The development of new products and services – Innovation – is happening at a rapid pace and urges firms to engage in common partnership to complement each other’s interest to stay competitive in this fast-changing economy.Thus, globalization can also be viewed as an opportunity, which enables firms to act globally in a global market through innovations in technology, communication, and transportation (Thurow, 2000).

Globalization of Innovation

The globalization of innovation urges companies to engage with external parties in order to stay competitive and innovate their products and services in line with the fast pace of technological change, as globalization enables the “international integration of economic activities” and raises the “importance of knowledge in economic processes” (Archibugi & Iammarino, 2002, p. 100).

The term globalization of innovation has been introduced by Archibugi and Iammarino (2002, p. 99) and refers to the “increasing international scope of the generation and diffusion of technologies” which is related to the generation of knowledge towards solving specific problems.

Archibugi and Iammarino (2002, p. 100f.) state three main categories of globalization of innovation, namely the (1) “international exploitation of nationally produced innovations”, (2) “global generation of innovations”, and (3) “global techno-scientific collaborations”. Respectively they describe: (1) companies and individuals exporting, licensing and producing goods and patents, which have been developed within the actor’s operating site; (2) multinational firms engaged in local as well as global R&D and Innovation activities, as well as the acquisition of as well as investment in external R&D laboratories; (3) national and multinational firms engaging in joint-ventures for innovative activities, as well as engaging in the exchange of technical informational and equipment.

The globalization of industries is a result of a new perspective towards technological innovation as well as its application and distribution (Reid, 1991), which, on the other hand, is the result of a global rise of the aforementioned interdependence between companies (Reid, 1991).

Globalization of Knowledge

The newly established interdependence and interconnectivity between firms leads to a globalization of knowledge, with knowledge being a crucial driver for productivity, growth, and innovation (Mohnen & Hall, 2013). The globalization of knowledge will figure as “the most important [way] globalization is transforming the economy” (Storper, 2000, p. 6)

Globalized Knowledge has been enabled through globalized human interconnectedness through emerging technological structures and forms a critical factor of globalized processes (Renn & Hyman, 2012). Renn and Hyman (2012) perceive knowledge as an influencer to all aspects of globalization. Knowledge is, thus, neither a precondition or a result of globalization, but rather the driver for “co-development of knowledge, technology and social interaction” (Renn & Hyman, 2012, p. 30).

Storper (2000) exemplifies this by the case that e.g. Asian firms can meet global market needs through forms of coordination and relationships between local economic players. Storper (2000) exemplifies Sweden as being very globalized, in the sense that more than 25% of their sales and production volumes are being traded outside of Sweden (van Tulder & Junne, 1988).

Fast Pace of Technological Innovation

Technology is changing at a pace, at which no single firm can stay competitive in their market or their technological state on their own, which causes a grand rise in collaborative efforts (Ramo, 1988, p. 15; Colombo, 1988, p. 25).

In today’s fast-moving economy, companies are forced to find new and more efficient ways to develop innovative products and solutions, in order to keep up with rising market demands (Antikainen, Mäkipää, & Ahonen, 2010). Previously, innovations were developed within a “highly closed process” inside the firm – mostly linked to the internal R&D department(s). Both reacting to, and anticipating growing demands for innovative products, companies need to find more efficient ways to support their internal R&D. There is a “compression of the time scale by which new technology is introduced, with ever-shorter intervals between discovery and application” (Colombo, 1988, p. 25). In addition to globalization, it is therefore essential for survival for firms to think, act, and connect globally, in order to complement each other through e. g. technological capabilities to drive innovation (Colombo, 1988).

The increasing mobility of the labour market and of knowledge has made it difficult for firms to generate satisfactory, innovative returns from internal R&D departments, as innovation, bound to the fast pace of technology, has to be generated in a complementary pace. This makes internal knowledge sourcing for innovation – on its own and un-supplemented – less attractive and, thereby, opens up the innovation process to include knowledge from outside sources (Mayer, 2010), as a wider and deeper outlook for external sources of knowledge leads to a greater possibility to innovative effectively (Laursen & Salter, 2006), linking this knowledge-outreach to the sources like “suppliers, customers, competitors, universities, research organizations, trade associations, meetings and conferences” (Fatima, 2017). Technology enables knowledge to flow between people in faster and less resistant way, as the change of technology allows for faster digestion and transfer of knowledge, interrelating the constant transformation of technology directly to the fast speed and intensity of a globalized world (Archibugi & Iammarino, 2002). They further acknowledge to mutual enforcement of both, rather than one influencing the other.

Globalization requires and enables innovation to prosper not just in a within a global dimension, it also initiates a much more rapid pace in which innovations are being developed. Globalization, thereby, is strongly linked to innovation, as it provides the tools and environment in which innovation capabilities grow through partnerships and collaboration (Colombo, 1988). Innovative goods are perceived to be of high strategic importance to firms (Pianta, 1988; Tyson, 1992; Scherer, 1992). As the innovation model has shifted from internally sourced innovation within closed R&D departments in firms towards more an open exchange of innovative resources across firm boundaries – the open innovation (OI) model – this provides a theoretical justification to explore a range of factors, which play a central role in facilitating collaborative innovation, namely: attitudes towards external knowledge sourcing on an individual basis and leadership behaviours for innovation.

1.1.3. Attitudes towards External Knowledge

We already touched upon the importance of external knowledge for companies in order to stay competitive and to innovate products and services in a more efficient and effective way. The question at hand is, where the problem with external knowledge sourcing lies?

In order to adopt new knowledge into internal practices, it is crucial to manage a teams’ attitude towards external knowledge, as innovation cannot be fully embraced, if there is no “valuation of outside competence and know-how” (de Araújo Burcharth, Praest Knudsen, & Alsted Søndergaard, 2014, p. 150; Witzeman et al., 2006).

Leveraging innovation, through the lens of open innovation, requires the coupled process between internal knowledge and external knowledge management, as no company can – considering globalization and the fast pace of technological innovation – innovate solely by themselves.

While internal knowledge sourcing has been the traditional way for R&D departments to generate innovation, external knowledge sourcing is a relatively new approach – initiated by the open innovation mindset – to supplement internal processes. Hereby, the problem lies within an often implicit negative attitude towards external knowledge, which has been named not-invented-here syndrome – “a negatively biased, invalid, generalizing and rigid attitude of individuals or groups to externally developed technology” (Mehrwald, 1999, p. 5; translation taken from: Lichtenthaler & Ernst, 2006) It is, therefore, crucial for companies to understand how attitudes come to be and how attitudes can be shaped, in order to fully embrace the open innovation paradigm and, thus, innovate in the currently most efficient and effective way through a coupled process between utilizing internal and external knowledge.

1.2. Research Question

RQ: Facing the challenges of globalization and the fast-changing pace of technology, what patterns between employee’s attitudes towards external knowledge acquisition and employee’s perceived leadership behaviours can be observed within tech companies in Sweden?

2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

As mentioned in our introduction, it is crucial for companies to enable effective knowledge management in order to extract innovative capabilities from the coupled process of internal and external knowledge sourcing. Knowledge management, hereby, relies on understand individual attitudes towards knowledge, and in particular towards external knowledge, as an individual’s attitude has an effect on the individual’s thinking, decision-making, and behaviour (Ajzen, 2001; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977) and can, thus, lead to “biased decision-making” (Ajzen, 2001; as quoted by Antons & Piller, 2014, p. 18). A purely subjective bias towards an attitude object, in our case towards external knowledge, can lead to severe implications. One such is that external knowledge can be perceived not based on its objective relevance and value, but rather on the individual’s attitude towards the source of the knowledge. This results in a mismatch between the subjective valuation and the objective valuation, which can lead to financial or temporal disadvantages for the project team, or company.

Thus, to effectively manage and influence the attitudes of employees’, the right set of leadership behaviours have been evaluated as widely influential. Although, in the context of organizational innovation and knowledge management, transformational leadership in particular has been directly related (Jung, Chow & Wu, 2003; Popper & Lipshitz, 2000, Politis, 2001; Sadler, 2001; Paul et al., 2002), more recent research points towards a combination of both transformational and transactional leadership to be more effective in combination in relation to knowledge-oriented leadership (Naqshbandi & Jasimuddin, 2018; Donate & de Pablo, 2015).

In the following sections we will define what attitudes are, to which deeper extend understanding attitudes is relevant to external knowledge sourcing, as well as its place within knowledge management. Concluding, we will explore the role of open attitudes as an enabler for open innovation practice. Subsequently, we will define leadership and specifically transformational leadership, and its application towards organizational innovation and knowledge management.

2.1. Knowledge and Knowledge Management

Before examining the role of attitudes in general and attitudes in relation to external knowledge in particular, we will define knowledge and its management in companies, as well as the importance of a coupled process between internal and external knowledge sourcing within knowledge management. Harris (2001) argues for an overall trend towards a knowledge-focused economy, as the competitive market has increasingly focused on knowledge (Lane & Lubatkin, 1998; Amesse & Cohendet, 2001).

Understanding knowledge management is, thus, crucial, as knowledge management explains to link between the utilization of internal and external knowledge as a coupled process. Knowledge management focuses on the individual, rather than the technology enabling it. It becomes evident that human factors are key enablers of effective knowledge management and thus the individual attitudes towards knowledge in general – external knowledge in particular – become a key aspect for companies to consider.

Knowledge

Knowledge in relation to globalization is defined as “the capacity of an individual, a group, or a society to solve problems and mentally anticipate the necessary action. […] in short, a problem-solving potential” (Renn & Hyman, 2012, p. 31). Knowledge can be divided in tacit and explicit knowledge, tacit knowledge being the knowledge residing in people’s heads, “hard to formalize and […] difficult to communicate to others” (Nonaka, 1991, p. 165), and explicit knowledge being “formal and systematic” (Nonaka, 1991, p. 165), suitable to be “shared, documented and communicated” (Allee, 2000, p. 4) While within psychology and philosophy, knowledge has been perceived as “mainly mental and private”, knowledge should be also perceived as something that “moves from one person the another”, therefore, as something sharable (Renn & Hyman, 2012, p. 31). The aspect of sharing knowledge among employees but also outside of the company, raises the matter of knowledge management to an essential aspect to a globalized economy (Renn & Hyamn, 2012), and thus essential for companies to consider.

Knowledge Management

Knowledge Management (KM) has been well-researched in the last decades, both in the academic and business field and defined as „the process of continually managing knowledge of all kinds to meet existing and emerging needs, to identify and exploit existing and acquired knowledge assets and to develop new opportunities” (Quintas, Lefrere, & Jones, 1997, p. 387). This results in the need for organizations to identify and manage all processes “by which knowledge is created or acquired, communicated, applied and utilized” (Quintas, Lefrere, & Jones, 1997, p. 387), thereby, introducing the need for companies to share, and create knowledge, which we will touch upon shortly.

Prior research (KPMG International, 2000; Ahmed, Lim, & Zairi, 1999; Lim, Ahmed, & Zairi, 1999) has emphasized on the organizational benefits by establishing knowledge management (KM) practices. These include: “minimizing potential losses on intellectual capital from employees leaving”, “improving job performance by enabling all employees to easily retrieve knowledge when required, “increasing employee satisfaction by obtaining knowledge from others and gaining from reward systems”, “providing better products and services”, and “making better decisions” (as reviewed by: Yang, 2008, p. 345).

These benefits include both the organization and usage of both internal and external knowledge. Especially, the amplified ability to provide better products and services relates to the environmental pressure firms have to deal with, namely: globalization and fast pace of technological advancement. Companies, therefore, focus on KM to improve their business processes, productivity, quality of products & services, as well as in finding new solutions products – (Nguyen & Mohamed, 2011). Effective KM is, as it enables innovation and the upgrade of services and products, therefore, vital for keeping up competitive advantages (Wenger, 1998).

It has to be acknowledged, that, within knowledge management, the focus is set towards people, rather than its underlying technology, as sharing – a critical aspect of KM success – is fundamentally human

(Puccinelli, 1998). In support, Guthrie (2001) and Bontis and Stovel (2002) make a case that employees – again, the human capital – are the major contributors to the effectiveness of KM. Yang (2008, p. 346) hypothesizes, based on this consideration, that individual attitudes towards ”learning, sharing and storing knowledge” are significant.

Internal and External Knowledge Sourcing as a Coupled Process

As mentioned, in today’s fast-moving economy, companies are forced to find new and more efficient ways to develop innovative products and solutions, in order to keep up with rising market demands (Antikainen, Mäkipää, & Ahonen, 2010). In this respect, knowledge has been defined as a key aspect in innovating products and services. Knowledge can be created – or sourced – both internally and externally. Hereby, the individual’s attitudes play a key role as to how efficient the process of knowledge creation is executed.

The overall trend considering innovating products and services has shifted towards a “concept of openness to the outside”, enhancing internal R&D processes by reaching out for external knowledge sources; e. g. competitors, suppliers, distributors, and customers (Chiesa, 2001, p. 14). In support, both Cassiman and Veugelers (2006) and Bock and Kim (2001) argue that combining both internal and external knowledge sourcing is crucial for companies to stay competitive in a fast-changing economy, as both paths can and should be used complementary within a company’s specific strategy.

This newfound value in sourcing knowledge externally in order to implement and combine with internal knowledge has been conceptualized through the term open innovation (OI), which Chesbrough (2006) defines as a free flow of innovative ideas and knowledge, both inwardly and outwardly through organizational borders.

Implementation of effective KM practices is not an easy task for leaders to approach, as its success depends on many organizational factors, such as “knowledge strategies, human resource practices, organizational knowledge bases, industry characteristics, and organizations performance” (Bierly & Daly, 2002, p. 292). Additionally, it has been stated that organisational culture is essential for successful KM (Davenport, De Long, & Beers, 1998; Demarest, 1997; Gold, Arvind, & Albert, 2001).

As a part of knowledge management, knowledge creation “deals with the acquisition and reformation of new knowledge” (Yang, 2008, p. 346), which according to Von Krogh, Ichijo, and Nonaka (2000) cannot be managed, as it can only be enabled. The effectiveness of knowledge creation and sourcing has been attributed not only to individual competencies (Yang, 2008) but also the individual’s attitudes towards external knowledge (Armistead & Meakins, 2002; Baum & Ingram, 1998; Dixon, 2002). Ruggles (1998) states, that the biggest challenge in knowledge management is to change people’s behaviours, as people are more inclined to perform a behaviour when they have a positive attitude towards this action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). In the following section we will, therefore, define attitudes more closely, its influence on external knowledge sourcing, as well as our model of measuring the expression of attitudes. The influence of leadership towards knowledge management, in particular towards changing individual’s attitudes towards external knowledge management will examined in subsequently.

2.2. Attitudes towards External Knowledge

De Araújo Burcharth, Praest Knudsen, and Alsted Søndergaard (2014, p. 150) and Witzeman et al. (2006) advocate for the aforementioned cruciality to manage a teams’ attitude towards external knowledge, as part of the knowledge management process, in order to actually adopt new knowledge into internal practice, as open innovation – which as a concept will be introduced later – cannot be fully embraced if a there is no “valuation of outside competence and know-how”.

2.2.1. Attitudes

Attitudes are generally conceptualized as a “psychological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favor or disfavor” (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993, p. 1). Attitudes can be defined and examined by multiple dimensions: attitudes contain elements such as evaluation, attitude object, and tendency; they can be enduring or convertible; they can be negative, neutral, or positive; explicit or implicit; stable or unstable; and they have antecedents and consequences in regard to cognition, affect, and behaviour.

Every definition of attitudes is supposed to contain the following elements: “evaluation, attitude object, and tendency” (Eagly & Chaiken, 2007, p. 582; as cited by: Maio & Haddock, 2010). Evaluation is, thereby, taken upon an object of attitude, or an individual or collective level, and can be concrete or abstract (Eagly & Chaiken, 2007). This process forms a tendency, according to which one individual responds to an object of attitude. Eagly and Chaiken (2007, p. 584) further add that attitudes are formed “inside the mind of the individual” and don’t exist until an individual perceives the attitude object to respond to it, consciously or unconsciously.

In order to understand how attitudes are formed and can change, it is important to view attitudes through its antecedents and consequences of cognition, affect, and behaviour (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). The cognitive aspect provides understanding on how people establish associations between the attitude object and attributes they tag to it (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975); the affective aspect refers to feelings, emotions, and physiological responses (Schimmack & Crites Jr., 2005); and the behavioural aspect lights up actions and intentions to act related to an attitude object (Eagly & Chaiken, 2007). All three, cognitions, affects, and behaviours can be evaluated on a scale, from positive, over neutral, to negative (Eagly & Chaiken, 2007). Nevertheless, Eagly and Chaiken (2007) conclude, that it’s not necessary for all three aspects to be evident, as attitudes can be formed based only on the presence of a number of presented aspects.

Once an attitude has been formed, this attitude can be enduring, but must not (Eagly & Chaiken, 2007). Wilson, Lindesy, and Schooler (2000) claim, that attitudes cannot be completely replaced, but overridden, as both the new and the old attitude constitute their own mental representation in the individual’s mind. A slightly different approach has been discovered by Petty, Briñol, & DeMarree (2007), stating that both negative and positive attitudes towards the same object can be accessed during the same mental process, based on the observation that individuals can code their own attitudes as true or face, and thus further evaluate a specific attitude with different levels of certainty (Maio & Haddock, 2010).

Pure attitudes cannot be observed, but the individual’s response to the attitude object can be observed, and thus researchers can provide evidence for the presence of an attitude (Eagly & Chaiken, 2007). This observable response is linked to the dimension of tendency, one of the three essential elements of attitude. Hereby, past experiences and encounters with an object forms a tendency to “respond with some degree of positivity or negativity towards an attitude object” (Eagly & Chaiken, 2007). Tendency, in this case, is described as a state, which doesn’t have to be of enduring nature (Eagly & Chaiken, 2007). Both the short-term as well as long-term endurance of attitudes depends on the individual and external circumstances.

Attitudes can be explicit or implicit, meaning that the individual might be either aware or unaware of an attitude towards a certain attitude object (Eagly & Chaiken, 2007; Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). An individual can have both an explicit and implicit attitude towards an attitude object, as new information can change an existing explicit attitude, while relocating the former to the level of an implicit attitude (Wilson, Lindsey, & Schooler, 2000). This further plays in favour of the unstableness of attitudinal expression (Eagly & Chaiken, 2007). Gawronski and Bodenhausen (2007) add, that explicit attitudes can further derive from internal evaluation based on assumptions that the person hold as being true, therefore, leading to a re-evaluation of an initial explicit attitude.

Even though research is indecisive to constitute an actual attitude–behaviour relation (as reviewed by Chaiklin, 2011), there are prominent researchers in the field who address a relation. As such Ajzen & Fishbein (1977) come to the conclusion, that a person’s attitude has a strong relation with his or her behaviour, when both are directed and researched towards the same attitude object. Ajzen (2001) – in a later research – states, that attitudes – on an individual level – have an effect on a person’s thinking, decision-making, and behavior. Attitudes can therefore lead to “biased decision-making” (Ajzen, 2001; as quoted by Antons & Piller, 2014, p. 18).

2.2.2. Importance of Attitude Management in Relation to External Knowledge

In relation the importance of knowledge sourcing within knowledge management, Hislop (2003) discovered that the crucial factor towards knowledge sourcing lies within the employee’s attitude towards it.

Knowledge externality, in specific, refers to knowledge sourced from different disciplinary, geographic, or inter-organizational contexts (Antons & Piller, 2014).

Quintas, Lefrere, and Jones (1997) further acknowledge the need to continuously seek external knowledge, in particular, to innovate and stay competitive, as they see that there is barely any company that can keep up with the overall technological progress all by themselves. Acquiring external knowledge is important to organisational innovation success for two main reasons. First, that the acquisition of external knowledge allows firms to develop internal competencies and create new knowledge of their own, thus enhancing their ability to create competitive advantage (Zack, 2005). Second, by using external knowledge, organisations avoid the risk of becoming over-reliant on internal knowledge and creating knowledge traps (Purcell & McGrath, 2013).

In relation to external knowledge sourcing, we can add the observation that suspicion and scepticism towards external knowledge is a natural tendency (Davenport, 1996). As Book and Kim (2001, p. 1114) hypothesize, according to “economic exchange theory”, knowledge sharing is supported when rewards exceed costs (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Constant, Kiesler, & Sproull, 1994). Therefore, when rewards can be expected, a positive attitude towards external knowledge should form. In addition, by the “social cognitive theory” (Book & Kim, 2001, p. 1115), “a person’s attitude and behaviour are influenced by […] self-produced factors as well as by […] external […] stimuli”, therefore, hypothesizing, that a positive contribution to the organization’s performance might develop positive attitudes towards knowledge sharing in the individual’s perception. Antons and Pillar (2014) argue that attitudes can definitely interact with each other and that multiple attitudes do trigger the rejection of external knowledge. Antons and Pillar (2014) acknowledge that a rejection of external knowledge can of course be based on “disciplinary, organizational, and spatial boundaries”, but in regard to a purely individual perspective, attitudes play a significant role.

2.2.3. The “Not-Invented-Here Syndrome” as a consequence of negative attitudes towards external knowledge

A multitude of organizational implications can arise when seeking for external knowledge. One such problematic implication is an employees’ negative attitude towards external knowledge (Herzog & Leker, 2010). A negative attitude towards external knowledge “worsens the performance of knowledge integration and impedes knowledge transfer in general” (Grosse Kathoefer & Leker, 2010, p. 660). This phenomenon has been named as the “not-invented-here syndrome” (NIHS). First introduced in 1982, by Katz and Allen (1982), the concept has been researched within the context of open innovation in the decades since. The existence of NIHS is widely acknowledged (Antons & Piller, 2014) and as Chesbrough (2006) and Antons and Piller (2014) point out, NIHS is one of the most significant attitudes towards external knowledge in the context of external knowledge sourcing.

Mehrwald (1999), one of the most prominent researchers on this topic, originally described NIHS as a negative stance against external technology (see also: Chesbrough, 2006). Hereby, Mehrwald (1999, p. 5, translation taken from: Lichtenthaler & Ernst (2006)) describes NIHS as a representation of “a negatively biased, invalid, generalizing and rigid attitude of individuals or groups to externally developed technology, which may lead to an economically detrimental neglect or suboptimal use of external technology.” Mehrwald (1999), hereby, focuses mostly on technology and doesn’t include the term knowledge within his definition. Still, the reader can follow that Mehrwald doesn’t exclude knowledge from his initial definition, as technology is just another form of knowledge. Lichtenthaler and Ernst (2006, p. 368), subsequently, update the definition of NIHS as “a negative attitude to knowledge that originates from a source outside the own institution”. De Araújo Burcharth, Praest Knudsen, and Alsted Søndergaard (2014, p. 151) define NIHS as “the rejection of external knowledge due to its source and not based on its content per se”, highlighting the practice of premature assessment of external knowledge, disregarding contents and quality while focalizing purely on its origin. Lichtenthaler and Ernst (2006) and de Araújo Burcharth, Praest Knudsen, and Alsted Søndergaard (2014) both furthered the definition of NIHS more towards knowledge sourcing.

The rejection of external knowledge based on devaluation is always excluding conscious and especially rational thinking, and, therefore, highly dependent on the individual’s personal attitudes. This leads to comparisons between the knowledge receiver and the source, which can threaten the self-concept of an organizational entity (Bartel, 2006), implying severe consequences for knowledge acquisition and utilization which can be crucial for a project’s success (Lichtenthaler & Ernst, 2006).

Antons and Piller (2014, p. 15f.) also collected further possible consequences: “incorrect evaluations of ideas and technologies (Agrawal, Cockburn, & Rosell, 2010; de Araújo Burcharth, Praest Knudsen, & Alsted Søndergaard, 2014; Grosse Kathoefer & Leker, 2012; Mehrwald, 1999), impeded implementation and increased development costs (Clagett, 1967; de Pay, 1998), project failure (Clagett, 1967; Herzog & Leker, 2010; Grosse Kathoefer & Leker, 2012), and a decline in firm performance (Allen et al., 1988; Katz & Allen, 1982). Grosse Kathoefer and Leker (2012) also mention general economic damages due to the rejection of knowledge that could have potentially been valuable (see also: Lichtenthaler & Ernst, 2006).

Considering the classification of NIHS as an issue on an individual level (Mehrwald, 1999), as it is a matter of attitude, leadership behaviours may play a critical role in reducing its initial development within individual employees, and may also be a valid, contraceptive instrument against its emergence. Antons and Pillar (2014, p. 36) acknowledge that a change of attitudes is a way to deal with NIHS. This can be done through informing employees about the issue und recognize it. More so, organizational leadership has to be proactive in the interaction with “a wider community of external actors” and therefore fight their employees’ negative attitudes towards external knowledge by leading by example.

2.2.4. Measuring Attitudinal Expression

Attitudes can be formed towards people, organization, or – in this case – external knowledge. How attitude theory can be explicitly linked to external knowledge sourcing can be best explained through its five major functions: an ego-defensive function, a value-expressive function, a social-adjustive function, a knowledge function, and an utilitarian function (Ajzen, 2001; Eagly & Chaiken, 1993), as reviewed by Antons and Piller (2014).

The ego-defence function says that attitudes help individuals to keep up and defend their self-concept through “denial, projection, repression or rejection” (Antons & Pillar, 2014, p. 18; derived from: Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). As Menon, Thompson, and Choi (2006) point out, especially managers and developers often define their professional self through their professional expertise in a certain field. This leads to a feeling of responsibility to solve a problem within this field by themselves (Pierce, Kostova,

& Dirks, 2001). As Antons and Piller (2014) point out, many professionals within R&D have been specifically hired for their individual expertise. Subsequently, a negative attitude towards external knowledge, in the case of the ego-defence function, can come through the individuals’ goal to defend their status (Antons & Piller, 2014).

The value-expressive function states, that individuals “are more willing to accept, adopt, and implement innovations when they are consistent with both individual and organizational values” (Antons & Piller, 2014, p. 19; according to: Klein & Sorra, 1996).

The social-adjustive function argues that attitudes also serve the purpose of keeping social relationships intact, but can also disrupt them (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). Attitudes can, therefore, be a means to establish a social identity (Bohner & Wänke, 2002). Therefore, an individual might devalue another person’s contribution to make him- or herself maintain a social position (Bohner & Wänke, 2002). Analogously, also a company – with a strong corporate identity – can reject external knowledge, following the same principle (Husted & Michailova, 2002).

The knowledge function states, that attitudes help an individual to organize his or her processing of knowledge in a simpler way, which can ultimately lead to a confirmation bias (Nickerson, 1998). Therefore, people in organizations might be biased to their own opinion, on e.g. a product, but the external reception might be different (Antons & Piller, 2014).

The utilitarian function argues that people’s attitudes help them to seek for positive outcomes and to prevent negative outcomes, whenever possible; attitudes, in other words, amplify an individual’s self-interest (Antons & Piller, 2014). Therefore, to come up with an idea or solution by oneself is considered to be more prestigious than to use an external idea (Husted & Michailova, 2002), leading individuals to promote their own ideas more actively.

In order to find out about employee’s attitude towards external knowledge, we adapted a set of questions from Grosse Kathoefer and Leker (2012), which they themselves extracted from Mehrwald (1999), which in this respect is deemed as a widely accepted in the academic field. The questions proposed can be grouped in 4 constructs: reluctance to knowledge sharing (Questions 5 and 6), preference for internal knowledge (Questions 1 and 2), reluctance to external collaborations {Question 3), and competitive importance of internal knowledge (Question 4) (Grosse Kathoefer & Leker, 2012, p. 670f.).

2.3. The Role of Leadership in Shaping Attitudes towards External Knowledge

Research into leadership in the innovation area has found transformational leadership to be directly related to organisational innovation (Jung, Chow, & Wu, 2003). However, a more recent study by Naqshbandi and Jasimuddin (2018) states that knowledge-oriented leadership combines elements of both transformational and transactional leadership. Bryant (2003) and Vaccaro et al. (2012) argue for the same combination of leadership styles to be effective for innovation outcomes. They base their argumentation in part by the work of Donate and de Pablo (2015) who add, that as for effective knowledge management, leaders are urged to adopt a combination of leadership styles.There are multitude of definitions of leadership in the organizational context. However, most accept that leadership has to do with the ability of an individual to exert influence over another individual in order to motivate them to contribute towards organisational goals. The practice of effective leadership involves performing an appropriate mix of task-oriented and relationship-oriented behaviours (Yukl, 2013). In an organisational setting, different tasks will require leadership competencies to be exhibited in unequal ways depending on the nature of a given project in order to be successful. However, critical thinking, influence, motivation and conscientiousness is seen in all managers of successful teams (Müller & Turner, 2010). The study of leadership in an innovation context is important as in an arena where creation and openness is paramount, an integrative style is required to direct expertise, people and relationships in such a way as to bring about new developments (Mumford et. al., 2002).

Consequently, the following sections will seek to first describe transformational leadership, before moving on to examine the role it plays in knowledge sourcing for innovation.

2.3.1. Transformational, Transactional, and Passive-Avoidant Leadership

Burns (1978) first introduced the concept of transformational leadership and contrasted it with transactional leadership behaviours, this was further developed by Bass (1985) and Bass and Avolio (1990) to formulate a theory of organisational transformational leadership. The general understanding is that the transformational leadership paradigm is an elaboration of charismatic leadership (Smith, Montagno, & Kuzmenko, 2004). Transformational leaders exhibit behaviours and attributes which influence individual followers to pursue wider organisational goals (Hill et al. 2012).

Transformational leadership is comprised of five elements: (1) Idealized influence (behaviour), (2) idealized influence (attributed), (3) inspirational motivation, (4) intellectual stimulation, and (5) individual consideration. Idealised influence in one sense describes the behaviours by which leaders act as role models for their followers. Leaders exhibiting these behaviours show sincerity and respect and infuse passion amongst their followers (Bass, 1985). Idealized influence in another sense describes traits attributed to the leader by followers; these are a sense of loyalty, admiration, trust and respect (Puffer and McCarthy, 2008). Inspirational motivation describes the behaviours of transformational leaders in setting high expectations of followers and the communication of the role of a followers’ work in achieving wider organizational goals (Hoffman et al. 2011). Intellectual stimulation regards the capacity for leaders to facilitate an environment suited to creativity and innovation and to foster a spirit of creativity and innovation to solve complex challenges. The final element, individualized consideration implies that leaders pay close attention to the needs of any given individual follower and provides support and assistance in their self-actualization and growth.

Transactional leadership, in contrast, motivates followers through the use of management by exception, that is to say the use of contingent reward and rule enforcement. Followers are influenced by transactional leaders because the reward mechanism makes it in their best interest to do so (Kuhnert & Lewis, 1987).

The passive/avoidant factor further diverges from transformational leadership in that it is a hands-off approach to leadership and in effect describes non-leadership (Northouse, 2010).

Table 1. below, summarize the factors of the transformational-transactional-passive avoidant

2.3.2. Knowledge-Oriented Leadership

Knowledge-oriented Leadership is defined leadership style that encourages the “creation, sharing, and utilization of new knowledge” (Naqshbandi & Jasimuddin, 2018, as retrieved from: Mabey, Kulich, & Lorenzi-Cioldi, 2012). Donate and de Pablo (2015) defined the combination of transformational and transactional leadership as the most effective way for knowledge management, thus, related the combination of both to knowledge-oriented leadership. Donate and de Pablo build this suggestion on Rowe’s (2011) statement, that, in an innovation context, company needs both managerial (transaction leadership) and visionary (transformational leadership) leadership styles. Knowledge-oriented leadership promotes knowledge management to prominent role within a company.

Research into transformational leadership is motivated by the conceptualization of the leadership behaviours associated with it to be the most fitting of a leadership style to transform organisations. As such, transformational leadership has been the most actively researched style in relation to innovation and knowledge management within organisations. Theoretical and empirical research findings of several authors point to transformational leadership as the most appropriate style for effective knowledge management within organisations (see Popper & Lipshitz, 2000; Politis, 2001; Sadler, 2001; Paul et al., 2002).

Polits (2001) found results which indicated that the leadership styles that involve human interaction and encourage participative decision‐making processes, namely transformational leadership are positively related to the skills and traits that are essential for effective knowledge management. Furthermore, Polits

(2001) proposed that the leadership behaviours characterised by participative behaviour, mutual trust and consideration for followers’ feelings and ideas were correlated strongly with positive attitudes to knowledge acquisition compared with task oriented and autocratic leadership behaviours.

In Elkins and Keller’s (2003) literature review on leadership in an R&D setting, the authors suggest that project leaders, who communicate an “inspirational vision” and provide “intellectual stimulation” – key facets of transformational leadership, are most associated with project success. Furthermore, in a long-term study of R&D leaders, Keller (2006) demonstrated capacity for transformational leadership defined as “the impression that he or she has high competence and a vision to achieve success,” (p. 202) positively predicts team performance for research project teams.

In a series of articles, Crawford (1998), Crawford and Strohkirch (1998, 2002), and Crawford, Gould, and Scott (2003) found that transformational leadership was connected with personal innovation. They argued that transformational leaders were significantly more innovative than their transactional and passive/avoidant counterparts. It is often assumed that innovative thinking is an important trait of effective knowledge managers. In practice, this trait manifests itself in the ability to create and effectively manage information and knowledge (Crawford, 2005).

Furthermore, and building upon this, in a 2016 study, Han et al. (2016) provided an empirical link to specify and describe the mechanisms by which “transformational leaders promote knowledge sharing by engendering employee’s psychological empowerment, organizational commitment” (p. 142). That is to say that when transformational leaders guide their followers by employing a strategy of individualised influence and recognising the need of each follower for developing personal potential, leaders instil a sense of responsibility in their followers towards their job roles and collective goals, as stated by their leaders (Avolio et al., 2004; Seibert, Wang, & Courtright, 2011). Additionally, empowering followers with increased autonomy for decision making, leads to higher levels of commitment and engagement in pro-social behaviours. That is to say an increased propensity to exhibit respective attitudes towards knowledge sharing (Guzman, 2008).

3. Methodology

The following chapter describes the practical approach taken towards the data collected for the purposes of further analysis in this paper. The selection of research design and process for data collection is discussed to reveal the motivations for the methodological choices made in relation to the stated research questions. Justification for design of the interview guide as our instrument for collecting data is given as well as reasoning behind the rejection of other methods. Furthermore, we will reflect on questions of reliability and validity in relation to the data collection methods.

3.1. Research Philosophy

Within ontological literature, there are predominantly two types recognised: objectivism and constructivism (Bryman and Bell 2011, Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2012). Objectivist ontology supposes that social phenomena and their meaning exist independently from and externally to social actors, viewing reality as a definite structure which can be observed objectively. Meanwhile, constructivist ontology draws meaning in social phenomena from the view that reality is “cognitively constructed” by the human imagination. Constructivist theory, states that social interactions are in a state of constant revision and it is this which produces observable social phenomena (Bryman & Bell 2011). In the environment of an organisation a constructivist ontology would state that, leaders themselves play a significant role in forming relations with their followers and followers attribute meaning to these relations subjectively. Moreover, attitudes towards external knowledge are shaped by an individual as aa consequence of the world around them. Since this paper seeks to examine the beliefs about experiences in these respects, a constructivist approach to ontology is adopted.

Epistemology is concerned with what is be considered acceptable when seeking to make truth claims about knowledge (6 & Bellamy, 2012). Bryman and Bell (2011) and Saunders, Lewis, and Thornhill (2012) describe two dominant discourses on epistemological stance: positivism and interpretivism. The two approaches differ in their stance towards the application of scientific techniques to make truth statements about social research (Long et al. 2000). Subscribers of interpretivism point towards the complexity in human nature and that social reality loses its meaning when data collected is viewed as un-prejudiced by subjective reality on the part of the researcher (Saunders, et. al., 2012). This is because researchers themselves hold values and therefore treat research subjects in a subjective way. Positivists on the other hand, argue that regularities in social phenomena which can be held true, independently of the values of the researcher. This paper adopts an interpretivist approach as through interpretivism, the nature of attitudes can be more appropriately explored in relation to leadership and external knowledge. This approach allows us to examine the experience of individual subjects and analyse the attitudes they describe towards leadership and external knowledge.

3.2. Research Strategy and Approach

Research strategy is a general plan for how the researcher approaches the collection of data to answer the stated research question (Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2012). In social research, it can be taken to mean to be the orientation between qualitative and quantitative data collection methods. Qualitative research seeks to understand the world via the interpretation of the individuals’ perspective. Furthermore, it provides researchers with access to the meanings people attribute to their experiences and social world (Silverman, 2011, p.133). Our research aims to extract insights into the meanings that individuals attribute to their experiences of leadership and external knowledge sourcing. Therefore, the primary concern is to extract data which provides insight into people's experience. As such, a qualitative approach is employed in the design of the empirical research conducted. Since this study seeks to examine the nature of attitudes towards external knowledge and perceptions of leadership, a qualitative approach is deemed suitable.

Exploratory research intends develop a description or an understanding of a social phenomenon (Blaikie, 2000). It does not offer final and conclusive answers to existing questions. Exploratory research is conducted to study a phenomenon that has not been clearly defined yet (Blaikie, 2000). The phenomena of attitudes towards external knowledge and perceptions of leadership can be considered in such a way. Therefore, the research approach is exploratory in nature.

Inductive research is used to develop inferences from a position of no prior knowledge of what exactly might be plausible, relevant or helpful to the researcher (6 & Bellamy, 2012). The stated research questions do not seek to rule conclusively on the truth of a hypothesis, rather they seek to uncover patterns which results of further empirical exploration would later lead to generalisable conclusions or theories (Creswell, 2005). It is for this reason, that we conduct the research inductively.

3.3. Methods

In the following section, the research method selected for purposes of data collection in response to the stated research question will be discussed. The use of a single qualitative method was selected as the primary data collection activity. This method was selected on the basis that it would best fits the ontological position of constructivism and epistemological position of interpretivism most suitably (Mason, 2002), as the research is interested in attitudes of individuals within an organisation and their perceptions of leadership.

3.3.1. Semi-Structured Interview

Conducting qualitative interviews, which can be defined as a managed verbal exchange (Gillham, 2000) producing in-depth data relating to subjects’ experiences and viewpoints pertaining to a particular topic (Turner, 2010). There are a number of forms of interview design that can be employed to obtain rich data using a qualitative investigational perspective (Creswell, 2007). Gall, Gall, and Borg (2003) identify three formats to interview design: (1) informal conversational interview, (2) general interview guide approach, and (3) standardized open-ended interview, also known as semi-structured interviews (Saunders et al. 2012). For this study, the informal conversational interview method was rejected as interviews of this type can be unreliable owing to inconsistency in questioning. This would make coding the data to seek emerging patterns difficult (Creswell, 2007). The general interview guide approach does offer a greater degree of structure however, its limitations exist in that, because questions can be phrased differently depending on the interactions with the interview subject, the reliability of the data collected is compromised and coding the data becomes less valid. The semi structured interview allows the subjects to fully express their viewpoints and experiences in their own words allowing for rich data whilst maintaining the reliability in that the interview questions are the same (Turner, 2010). The exploratory nature of this research therefore warrants semi-structured interviews as a suitable method.

The semi-structured interviews were conducted in an informal style using open ended questions for the gathering of data in relation to attitudes towards external knowledge, this allowed the interviewer to adjust the questions somewhat if the subjects were unfamiliar with ambiguous terms or required clarification on the meaning of a give question. Furthermore, where subjects’ responses were ambiguous or closed, follow-up questions could be asked to seek richer answers. This effort to interact with the subject aligns with the ontological and epistemological position.

The use of interview methods for primary data collection in qualitative researched can be critiqued as being biased by the subjectivity of the researcher and less reliable than quantitative approaches. Denscombe (2007), discusses how people respond differently in semi-structured interviews depending on how they perceive the interviewer, “In particular, the sex, the age, and the ethnic origins of the interviewer have a bearing on the amount of information people are willing to divulge and their honesty about what they reveal” (p.184). In order to mitigate these effects, an interview guide was used and will be discussed in the following chapter.

3.3.2. Interview Guide

For the purposes of upholding both reliability and validity of this study a research guide was created to inform the interview process. McNamara (2009), describes eight principles connected with effective interview preparation: (1) choose a setting with little distraction; (2) explain the purpose of the interview; (3) address terms of confidentiality; (4) explain the format of the interview; (5) indicate how long the interview usually takes; (6) tell them how to get in touch with you later if they want to; (7) ask them if they have any questions before you both get started with the interview; and (8) don't count on your memory to recall their answers. These principles were applied through the opening section of the interview guide used by interviewees.

Interviews were initiated with an introduction of the researchers, a general overview of the purpose and aims of the research and consent for the interview to proceed was agreed. It was also stated prior to any questions being asked that the researchers would gladly provide clarifications as to any misunderstandings or ambiguities. Then, subjects were asked a series of demographic questions to begin the interview, including their job role, time in that role and type of organisation they worked for. Second, questions were asked regarding the subjects’ attitudes towards external knowledge. Questions for this section have been adapted from previous research identified in the literature review, namely Grosse Kathoefer and Leker’s 2012 study. The research was interested in collecting data about subjects’ attitudes towards external knowledge and as such questions sought to uncover preferences, confidence and attractiveness of sourcing knowledge externally. Thirdly, the segment on transformational