http://www.diva-portal.org

This is the published version of a chapter published in Handbook on society and social policy.

Citation for the original published chapter: Righard, E. (2020)

Transnational social vulnerabilities and reconfigurations of 'social policy': Towards a denationalized research agenda

In: Nick Ellisson & Tina Haux (ed.), Handbook on society and social policy (pp. 473-485). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing

N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published chapter.

Permanent link to this version:

Transnational Social Vulnerabilities and Reconfigurations of ‘Social Policy’ –

Towards a Denationalized Research Agenda

Erica Righard and Mikael Spång

Abstract:

Public social policy was institutionalized at a time of intense nation-state building; it was shaped by, and contributed to the closure of the Westphalian system of social protection. Today’s globalization processes in general, and population mobility and cross-border dynamics of social problems in particular, challenge such framings of social problems and policy interventions. The ‘mobility turn’ within the social sciences has brought forward relevant theoretical tools and perspectives for the unbounding of the social from such national framings. This chapter contributes to this debate by reviewing two kinds of social policy developments in which this unbounding is evident, though varying in scope and dynamics. The first example draws on a single-case study of the public old-age pension in Sweden; it shows how this has included national and foreign citizens who have immigrated to and emigrated from Sweden in varying degrees over time. The second example points the growing importance of international organisations in field of public health, compared to inte era of international cooperation, and discusses implications of this for a rights-based health care. The chapter suggests a denationalized epistemology as a fruitful way forward for debates about social justice and social policy within and across countries in the globalised society.

Keywords:

Transnational migration; globalisation; social policy; public health; pension; denationalization

Introduction

Social policy is sometimes described as the social dimension of the nation-state in much the same was as social rights have been described as the social dimension of citizenship. These descriptions are underpinned by assumptions of social policy as a branch of public policy and, as such, they are closely bound up with the modern state and with conceptions of citizenship as a prerequisite for access to national social security and service systems. This national framing of social vulnerability and social protection is, of course, open to challenge in multiple ways. In this chapter we aim at exploring some theoretical perspectives and empirical examples that can contribute to a critical and informed debate about social policy from a denationalized epistemological standpoint.

While public and social policies are bound up with nation-states, and ‘national’ in reach and purpose, many social vulnerabilities as experienced in everyday life, being transnational in character, manifest themselves beyond national boundaries. It is against this backdrop that some proponents have initiated debates on transnational and global social policy (e.g. Lightman, 2012; Yeates and Holden 2009). On a general level this has to do with scaling – in effect, the scaling of social vulnerabilities as these are experienced individually and

collectively, and as they are responded to in policy terms. If we look to how vulnerabilities are experienced, significant proportions of putatively ‘national’ populations are ‘mobile’, with some elements migrating permanently, and others remaining in more temporary and/or circular patterns. Some people may even live their lives across state borders, anchored in places in two or more countries. This means that their livelihoods and the vulnerabilities associated with the lifecourse are, at least to an extent, transnational in nature, and cannot therefore be responded to adequately when limited to one national context. Importantly this transnational condition can involve migrants and non-migrants alike. At the same time, while most social protection is distributed through state-led public schemes, also for mobile populations moving between states, we also see policy responses that are manifested beyond the limit, as well as control, of national states. In this chapter we shall consider these issues and their consequences for social policy development in

To this end, we shall outline the changing relationship among social policy, the social sciences and the modern state as this developed from the first appearance of the ‘social question’ in the later years of the nineteenth century, through the period of welfare state expansion in the post-war era, and finally as globalization processes intensified from around the 1980s onwards. This involves a brief consideration of the emergence of the notion of the Social, how it initially became associated with the nation-state from the end of the

nineteenth century, and how this relationship was first strengthened during the postwar era and later increasingly questioned and even to some extent disembedded owing to the pressures of globalization. This historical outlining illustrates how scales of social

responsibility have varied over time, while also providing us with a conceptual vocabulary needed for the two subsequent sections of the chapter.

In the first of these, with the help of an empirical focus on public pension schemes, we describe how social rights for mobile populations have changed over time. As rights were bound up with national citizenship during the welfare state golden years, extensions of access to non-citizens were framed as denizenship. Instead of citizenship and particularistic solutions for non-citizens, today social rights are increasingly based on on previous income conceived and measured as state-taxed income and on territorial belonging measured as enduring domicile registration. While more empirical research into this field is definitely needed, not least in a comparative perspective, we will here highlight some limited evidence that suggests that social rights are increasingly being unbounded from citizenship. Naturally, this will have far reaching consequences for assumptions about social policy as the social dimension of the nation-state, as well as for social rights as the social dimension of citizenship.

In the following section, with an empirical focus on public health, we describe shifting scales of policy responses to epidemics and health concerns, highlighting shifts also at international and global levels. Some of these matters nowadays take place in the context of WHO but they also involve networks of physicians, public health workers and other professionals as well as philanthropy associations and commercial companies. What is interesting in these responses is how they involve a potential reconfiguring of state responsibility. The

implications of this are of course difficult to know, but changes over past decades suggest that developments of this kind are likely to be significant.

In the last and concluding section, building on our theoretical outline and the two examples of public pension and public health, we discuss some consequences of the reframing of social policy from a social justice and critical standpoint.

Reconfigurations of the Social

Social policy as we know it today, is usually thought of as an arm of public policy dedicated to the provision of a range of social security schemes and services. This way of organizing social policy was shaped by the modern state as it emerged from the end of the nineteenth century. The production of scientific knowledge within the social field in the nineteenth century, and later the formation and expansion of the social sciences within academia, played an important role in this development (Wagner et al., 1991; Rueschemeyer and Skocpol, 1996). Karl Polanyi (1944) has, from a historical-economic perspective, famously described this societal development as the ‘great transformation’, showing how key spheres of society were reconfigured in relation to each other with implications for the organisation of social responsibility. In this chapter our aim is not to detail this historical development; rather we shall use it to contextualize contemporary societal transformations arising from globalization, and to stress that ongoing change carries an element of dynamic continuity, rather than constituting a radical break with a static past.

Towards the second half the nineteenth century, in the wake of industrialization and urbanization, social problems of new kinds emerged, particularly in the rapidly growing cities. Issues of housing, poverty, education and public health led to wide-ranging debates about the merits, or otherwise, of public intervention to remedy the worst effects of what during a phase of, in Polanyi’s wording, ‘disembeddedment’ was managed under the operation of the free market. In what was often referred to as the social question (also la

question sociale in French and die soziale Frage in German), national states in Western and

Northern Europe and in North America established a range of social policies that became increasingly comprehensive over time (Esping-Andersen, 1990). In this way, previous local

poor relief systems, based in family and community reciprocal relations and/or philanthropic organisations, was gradually supplemented or replaced by social rights through state-led public policy. In this way, social policy also contributed to nation-state building as well as its (territorial) closure (Soysal, 1994; Ferrera 2005). Welfare state development first involved access to social services such as public education and later to nationalized social insurance systems, including, for instance, work injury, old-age pension, and sickness. The role of public social policy for nation-building is well known, not least the development of state education (e.g. Meyer and Tyack 1979; Tilly 1975) but also the welfare state more broadly (e.g. Clarke, 2005; Ferrera, 2005). Central to our argument here is how this development contributed to the conflation of the Social with the nation, so that the Social in effect became the embodiment of the nation in the sense that, for instance, social integration would be assumed to mean integration into the national community of a particular country (e.g. Wimmer and Glick Schiller, 2003). This conflation was strengthened and ‘naturalized’ in feedback exchanges between social policy and the social sciences, as welfare state

expansion, policy developments and the nature of ‘policy’ itself became objects of enquiry and knowledge production.

With the intensification of globalization from around the 1980s and onwards, the nature of the relationship among the Social, the nation-state and the social sciences was increasingly questioned. This critique built on empirical observations to which existing concepts did not fit and it called for a reconceptualization of the social. It was noted, for example, that, while the social sciences, and perhaps social policy in particular, tend to assume that people are ‘sedentary’ – in the sense that to stay in one country to which one has strong feelings of belonging is natural, and to cross national boundaries and to travel far from ‘home’ is deviant – this is really more of a normative assumption than an empirical observation. As an empirical observation, many people are in fact increasingly mobile. Their social worlds do not necessarily correspond with the territoriality of nation-states but can be anchored in two or more places, in what has been conceptualized as transnational social fields or spaces (Basch et al., 1994; Faist, 2000). In this view, transnationalism is related to globalizing processes, but has a more limited purview in that ‘transnationality’ is more connected to how people organize and conduct their everyday lives. These insights, which today are the subject of a vast number of research publications, have prompted a number of critical

accounts of the social sciences and their tendency to adopt nationally grounded

epistemologies. For instance, in migration studies social science research has been critiqued for its methodological nationalism (Wimmer and Glick Schiller, 2003), and in sociology for its use of ‘container theories’, as if nation-states constituted naturalized containers in

economic, political and social terms (Beck, 2000). On a more general level, proponents have argued for a denationalisation of the social sciences (Sassen, 2010), urging that social science research should problematize sedentarism and account also for ‘mobility’ (Urry, 2000). This epistemological development does not imply that nation-states have no meaning or power – they do, immensely. Rather it argues that the national scale, explicitly and implicitly, is assumed to be the preeminent frame for understanding the social in all societal spheres. This development has been conceptualized as a ‘mobility turn’ in the social sciences (Shelly and Urry, 2006) and it can be viewed a paradigm shift in the Kuhnian sense (Kuhn, 1962). The ‘mobility turn’ in the social sciences has enabled the re-scaling of the social, and, in this way, foregrounded debates on the social question and social policy from a variety of

perspectives. The issue is highly relevant for at least two reasons. First, an increasing proportion of the world population lives, or has lived, sometimes repeatedly, outside their country of origin. While many of these individuals and families migrate to overcome vulnerability, migration also escalates vulnerability. This raises questions about social protection across borders. Second, global interconnectedness has led to a growing

awareness of global social inequalities and, at least to some extent, an up-scaling of social policy to the global level, as we outline below. In this development legal and policy measures such as the General Convention of Human Rights (1948) and the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals are central. From an epistemological standpoint beyond methodological nationalism; a denationalized epistemology, these two dimensions of the social question has been conceptualized as the transnational social question (Faist, 2009).

The argument we make here is that the globalization processes that affect all levels of societies and the transnationalisation of people’s everyday life, provokes the need for a re-conceptualization of the social, not taking the national scale as preeminent and ‘given’. In the following we shall look into two cases of what this might entail. The first is about the transnational dimensions of public policy, which here refers to how state-led social policy

schemes include mobile populations, emigrants and immigrants, as well as citizens and foreigners alike. The empirical focus is on Swedish public old-age pension arrangements and it shows how transnational populations have been integrated in varying ways at different times. The second case regards the re-scaling of social policy from the local, via the national, and to the global level. The empirical focus is on public health and it demonstrates how the ‘social’ in social policy is tied into, and shifts with, varying scales of knowledge production and forms of. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss these matters in depth, but we still need to comment briefly on the fact that public health can be more easily up-scaled since it does not involve tax-financed redistributional social insurance, whereas, old age pensions do (see e.g. Ferreira 2005). Social rights in the latter case are typically more closely bound up with the state and the national community.

Segmented public social protection for mobile populations – the case of old-age pensions There is an inbuilt tension between, on the one hand national welfare states protection schemes tied up with national citizenship and/or other forms of territorial belonging, and on the other social protection needs among migrant workers and other mobile populations. This has prompted research on transnational social protection (TSP). The concept embraces both informal and formal cross-border systems of social protection, including the public, the market, civil society organisations and family networks (Brunori and O’Reilly, 2011; Paul, 2017). For our argument here, we limit the focus to state-led social policy and how this responds to mobile individuals and groups (Lightman 2011). It is also true, that when it comes to formal social protection systems, these are in mainly provided through national legislation, including for mobile populations (Sabates-Wheeler & Feldman 2011). This

approach is distinct from much of the earlier research on migrant social protection, that was more or less obsessed with the integration of migrants into national welfare systems – in effect caught up by a methodological nationalism that focused on the ‘integration’ of the (deviant) newcomer, disregarding the multidirectional nature of mobility.

Social protection for migrants through public social insurance schemes depends on access in the country of residence, and the portability of rights from previous countries of residence (Sabates-Wheeler, et al., 2011). This can involve several countries, and also several periods

of stay in a particular country – and these circumstances need to be taken into account when people are still on the move in a temporary host country and after return to their country of origin. Importantly, the whole family is typically dependent on social protection provision, though all members may not necessarily all be migrants, as even the relatively small nuclear family can have members dispersed across two or more countries, including their country of origin. This means that the questions we raise here about the nature and extent of social provision involve many more people than just those who are included as migrants in migration statistics as presented by the United Nations and other organisations, (see e.g. Holzmann and Wels, 2018).

Empirical research on the portability of social rights is still limited in scope (for a review see Holzmann and Wels 2018, pp.326–7), and in general it is not combined with questions about access to social rights. In addition to the usual questions of a social policy analysis, who is eligible for what, and in order to denationalize research design, we propose that the analysis of access to transnational social protection through public policy should ask the following questions: is it necessary to live in a country to be eligible to national social rights? If so, how long should an immigrant live in a particular country before being eligible? Should access expire after emigration – and if so, how long after emigration? And, finally, what is the role of national and foreign citizenship in these matters? To provide some answers to these questions, we shall here rely on a study of the basic protection of the Swedish old-age pension conducted from this epistemological standpoint (see Righard, 2017 for a more detailed account of what follows).

The transnational social responsibility of the Swedish old-age pension has changed both in reach and dynamic over time, since it was established in 1913 as the first universal social security scheme worldwide, covering the whole population, regardless of means and contribution. The system was gradually extended and from 1946 a flat-rate Basic Pension, named the People’s Pension, was put in place. In 1959 it was complemented with an income-based Supplementary Pension that required 30 years of work-based income in Sweden. It is this pension scheme that was part of the extended Swedish welfare state, as analyed in, for instance, Gøsta Esping-Andersen’s (1990) work on welfare state regimes. In 1998, this two-tier scheme was radically restructured and replaced by a three-tier scheme.

From this point on, the principle pension was the Income Pension, based on previous income during the whole life-course. For those who have had a sufficient taxed income, this entails both the basic and the supplementary part of their pension. On top of this a Premium Pension was introduced that is proportional to the bonus of pension premiums paid through income tax. For those who had too little income to be eligible for the Income Pension a third alternative, a Guaranteed Pension, was established. In order to be eligible for this pension individuals must have resided in Sweden for a minimum of three years; to be eligible for the full scheme it is necessary to have been a resident for forty years between the age of 25 and 65 years. Claimants with a shorter period of residence, are eligible for 1/40 of the full

pension for each year of residence.

The analysis, relying on unilateral policy documents and regulations over a hundred-year period, shows that the transnational social responsibility of the basic part of the old-age pension scheme can be divided into three time periods. In the first period it was a scheme for nationals with domicile registration in Sweden only; the transnational reach is non-existent. The second period, starting in the early 1960s, covers transnational situations. This extension emerged due to a concern that Swedes who had been working their entire life in Sweden, would not access their pension as a pensioner if they moved away from the country, and upon return to Sweden only after a delayed administrative process that could take up to 18 months. It was argued that citizens with ‘strong ties’ to Sweden should be able to access their pension outside of Sweden and immediately after return to the country. In 1962 the regulation was revised to include Swedish citizens living outside Sweden. The preparatory work preceding the bill, saw lengthy discussion about the meaning of ‘strong ties’ to Sweden. It was decided, in a rather ill-considered way, that if a person had been registered as domiciled in Sweden for five years close to her/his pension age (65 years), between the ages of 57 and 62 years, it was very probable that the person had ‘strong ties’. This rule was named the 57–62 rule and was later criticized for being too arbitrary. In 1967 the regulation was amended again, so that national citizens who moved back to Sweden did not have to wait to be registered as domiciled in order to access the basic old-age pension scheme. In practice, this only had relevance for citizens who were not eligible according to the 57–62 rule. It was only in 1979 that foreign citizens could access the basic part of the pension scheme, and then only after a period of 10 years of residence in Sweden. That same

year, the 57–62 rule was replaced by a regulation allowing citizens to access the basic pension in proportion to their number of working years in Sweden.

This period, starting in the early 1960s is characterized as one of radical transnational responsibility. The extension of social rights to nationals outside of Sweden, and to foreigners inside of Sweden constitutes extensions of social rights beyond previous territorial constraints. While extensions of rights to foreigners in the hosting country has often been discussed in terms of denizenship, extensions to nationals outside of the country of origin has typically been disregarded. Nevertheless, these dynamics are interconnected and relevant to understandings of transnational social protection.

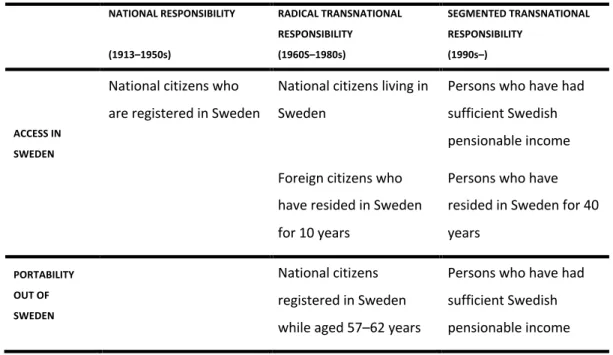

The third period, starts with the implementation of the new pension system in 1990s. Through a number of sequential decisions, from 1998 the pension scheme was profoundly restructured to be based on either residence or income, as briefly outlined above. From this point, citizenship status has had no impact on access to, or the portability of, the Swedish old-age pension scheme. As Figure 1 below makes clear, Sweden has instituted a form of ‘segmented transnational responsibility’ since the late 1990s. In practice this means, that persons with a sufficient pensionable income and/or with pensionable rights that, due to international agreements (which are largely forged with wealthy OECD countries), can be transferred to Sweden, will be eligible for the Income Pension, which has extensive transnational reach for pensioners. However, it also means that persons with little or no pensionable income and/or originating from a country with no international agreement, will be eligible for the Guaranteed Pension only if they have resided in Sweden for a sustained period of time. In addition, eligibility to the Guaranteed Pension only applies when

registered in Sweden and, hence, has no transnational reach. This means that access to mobility is unevenly distributed between poorer and more wealthy pensioners. In addition, and unsurprisingly, this pension scheme has also led to increased inequality gaps among pensioners in Sweden, with people from countries with no reciprocal agreements – so-called third-country nationals – being overrepresented among the elderly poor in Sweden (Swedish Government, 2010:105). In this way, the public pension scheme functions to reproduce patterns of global inequality within the national population.

Figure 1. Trans-/national responsibility in the Swedish old-age pension scheme NATIONAL RESPONSIBILITY (1913–1950s) RADICAL TRANSNATIONAL RESPONSIBILITY (1960S–1980s) SEGMENTED TRANSNATIONAL RESPONSIBILITY (1990s–) ACCESS IN SWEDEN

National citizens who are registered in Sweden

National citizens living in Sweden

Persons who have had sufficient Swedish pensionable income Foreign citizens who

have resided in Sweden for 10 years

Persons who have resided in Sweden for 40 years PORTABILITY OUT OF SWEDEN National citizens registered in Sweden while aged 57–62 years

Persons who have had sufficient Swedish pensionable income

Social policy goes google – the case of public health

Another important example to address when looking at the transition from local to national and transnational levels of service provision is public health. While most of the debates from mid-nineteenth century to early twentieth century focused on what measures to adopt within nation states, they also had international dimensions, which were particularly evident in the context of epidemics (Bashford, 2006). Later these measures based on international cooperation between nation states, have changed in dynamics and the question is to what extent we can see an emerging denationalization of social policy.

Many of the initial discussions focused on the regulation of quarantine, used from early modern times as a way to handle epidemics but they broadened over time to involve questions about information on the spreading of diseases, vaccination and hygienic measures. Efforts were made to establish permanent international offices, leading to the setting up of the Office International d’Hygiène Publique (OIHP) in 1907. This office was involved in organizing international conferences and the exchange of epidemiological information. After the First World War, in 1920 the League of Nations established an

epidemic commission, which evolved into the League of Nations Health Organization (LNHO) in 1923. The LNHO worked within several areas, particularly epidemiology, technical studies and the exchange of knowledge. Its Far Eastern Bureau, established in Singapore, played a key role in this context, collecting and disseminating epidemiological information.

Knowledge about the outbreak of epidemics and their spread were major areas of work in the LNHO, which also engaged in work on hygiene and developing public health capacities in states throughout the interwar period. In addition to the LNHO’s activities, several initiatives by philanthropy associations such as the Rockefeller Foundation’s International Health Board, engaged in hygiene work and the spreading of medical and public health knowledge across the world. Indeed, the Rockefeller Foundation funded much of the League of Nation’s epidemiology intelligence work (Bashford, 2006).

After the Second World War, much of the work carried out by the League of Nations’ organisation continued within the framework of the newly constituted United Nations. The World Health Organisation (WHO), established in 1948, came to play a similar role as the LNHO in the dissemination of information on epidemics and fostering health care capacities. An example is the global influenza surveillance programme, involving a worldwide network of laboratories connected through radio and telegraph, established in the late 1940s. However, the International Health Regulations (IHR), which regulate the work of WHO, stipulated that the latter could only act on the basis of information provided by national governments. This led to several problems, notably that many outbreaks were not reported or only reported after much delay. In addition, the IHR only specified a small number of diseases (such as cholera, plague and yellow fever), basically those that had already been the subject of discussion in the mid- and late nineteenth century. This constrained the kind of information WHO could gather and report (Fidler, 2003; Thomas, 2014).

Several developments in 1990s led to changes in the approach of WHO, which are often perceived as a shift from international to global public health (Reubi 2017; Weir and Mykhalovskiy 2010). One important element of these changes was the easier spreading of information through the use of personal computers, enabling physicians and public health experts worldwide to collect and disseminate data from several sources as well as engaging in discussions about the analysis of these data (Roberts and Elbe, 2017; Thomas, 2014).

Increasing discussions about new transnational health threats – such as the more rapid spread of diseases through increasing air travel and the spread of unhealthy lifestyles (such as tobacco use) by multinational corporations – were also central to a shift of concern about health issues from international to global levels. In addition, neoliberal policies played a role in linking public health issues to the structure of economies in different ways than had been the case during the post-war era of the ‘Keynesian National Welfare State’. Scholars point to the fact that the World Bank, not the WHO, took the lead in revising public health concerns in its Investing in Health report from 1993 (Kenny, 2015). These and other developments led to discussions about revising the IHR and in 1995, the World Health Assembly decided to undertake changes to the regulations. A new regulation was adopted in 2005, which stipulates that the WHO may use several kinds of sources of information. In addition, the new regulation encompasses a mandate to work with all public health risks (Fidler and Gostin, 2006).

An important element in the development of these changes has been the elaboration of new disease surveillance systems. One example is the programme for monitoring emerging diseases, ProMed-mail, established in 1994. Set up with the support of Federation of American Scientists, it has been run since 1999 by the International Society for Infectious Disease and covers some 70 000 subscribers in about 185 countries. ProMed-mail enables scientists, physicians and public health professionals to exchange reports and information about infectious diseases, using several sources (not only official health data). Incoming reports are analysed by expert moderators who assign an urgency rating to them. Today, in line with the changes of the regulation of the WHO, the organization uses this and other systems for detecting outbreaks of diseases. Another example, operated by the WHO, is FluNet, set up in 1997. This is a web-based platform for disseminating information on influenza viruses and their spread in populations. It builds on the already existing WHO influenza surveillance system, consisting of a set of worldwide laboratories that analyse virus samples in order to determine whether they differ from viruses for which vaccine already exists. FluNet is part of global efforts to track influenza outbreaks (Roberts and Elbe, 2017; Thomas, 2014).

Both of these surveillance systems are based on human beings analyzing data. Other systems use algorithms to process large quantities of data. One early example is the Global Public Health Intelligence Network, developed by WHO and Health Canada, which is based on continuously analysing news reports about diseases. This system was the first to integrate information-retrieval algorithms in its operation, allowing it to scan and pull out relevant news reports from news aggregator systems every 15 minutes 24/7. This surveillance system uses proxy data, which is also the case in other systems. For example, a system aiming not only to track outbreaks but to anticipate them is the Google-based Flu Trends. This builds on Google searches and other data, for instance on the sales of medication and groceries like orange juice, calls and visits to primary health care clinics, and so on. In developing the system, Google used aggregated logs of web searches from 2003 to 2008 and ran them against actual data of influenza outbreaks and spread in United States, producing 45

different search queries that strongly correlate with influenza. The aim of Flu Trends was to be able to anticipate what is going to happen, although the platform encountered setbacks after a couple of years because of its tendency to overestimate the risks of outbreaks and their spread (Roberts and Elbe, 2017; Thomas 2014).

These concerns about international and global health issues also gave rise to several scholarly debates. Several scholars have stressed that the period from the mid and late nineteenth century through to the late twentieth century has been one defined by international cooperation. David Fidler (2003) calls this a period of Westphalian public health, in which states cooperated on acquiring knowledge about epidemics and their

spread as well as regulating trade and travel between states in light of this knowledge. There were obvious limitations to this approach, as already noted with respect to the regulation of the WHO. Fidler (2003, p.487) also stresses that ‘infectious disease control crafted in the last half of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century never required states to improve national sanitation and water systems despite knowledge that such improvements would decrease cholera outbreaks and their spread’. Other scholars, by contrast, argue that a global more than an international concern with health was already visible during the interwar period. Alison Bashford (2006), for example, points to how the collection and dissemination of information at this time already involved the use of several

different channels of communication. National governments did not rely solely on the official communications of international agencies.

Irrespective of the precise point in time when we may speak of a global and not only international concern with health, there are reasons to foreground anxiety about public health, the tracing of epidemics and the like when discussing social policy and

transnationality. In a similar manner to how public health proved to be key to the

development of broader social responsibilities of national governments in the nineteenth century, a line can be traced from the internationalization of health issues in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to questions about the nature of global

responsibilities for public health in the contemporary world. These are often discussed in terms of global health security. Lindsay Thomas (2014, p.291) contrasts the international and global framing in this way:

In contrast to surveillance under international public health, which involved the monitoring of diseases at the level of the population and the timely

communication of this information to the appropriate officials, surveillance under global health security involves the monitoring of ever-larger ‘global’ populations and the instantaneous dissemination of this information. Yet, when noting these changes from the national to the global scale, we need to keep in mind that earlier ways of discussing demographic phenomena were by no means restricted to dealing with national populations. One example is the use of life tables in private life insurance companies, from the early nineteenth century being based on the insured population. British companies played a pivotal role in this regard and their life tables were used when setting up branches in other countries as well as by life insurance corporations established in other European countries and the United States. In addition, while ‘the population’ was often the mark used for discussing demographic issues, most observations of such phenomena and their integration in technologies of governing involved more specific sub-groups of populations, such as factory workers in the case of work injuries insurances, for example. The way that the population makes up one element of the legal definition of

the state has often led to the assumption that observations of demographic phenomena relate only to national populations.

Partly connected to these questions about territorialized populations is the question of whether the internationalization and globalization of health concerns involves shifts in the underlying rationality of how particular characteristics of populations and policies deemed necessary to protect them are integrated. Several scholars suggest that there have been such shifts. Lorna Weir and Eric Mykhalovskiy (2010, p.8) talk of global public health vigilance in this context, which directs attention ‘to apparatuses that continuously monitor phenomena that may give rise to catastrophic events.’ This reference to catastrophic events is central because it indicates a change in rationale that Andrew Lakoff (2007) usefully contrasts with the insurance paradigm that developed in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Insurance aims to compensate for contingencies that are likely and therefore possible to map on the basis of observed demographic regularities, whereas the present global health security approach is guided by preparing for unlikely events that, however, would have catastrophic consequences if they actually occurred. He argues that the global health security approach of early warning and the rapid tracking of disease outbreaks and spread combined with WHO-coordinated recommendations constitutes a new form of rationality presently under construction. In this new space, preparedness plays a key role. However, one needs to understand this kind of rationality in relation to another – what Lakoff calls humanitarian biomedicine – which is increasingly involving philanthropic associations and non-governmental associations that often bypass national health

authorities. Thus, Lakoff (2010) suggests that we are witnessing two global health models emerging, one ‘offering a philanthropic palliative to nation-states lacking public health infrastructure’ and another focused on the early warnings of outbreaks of potentially catastrophic pandemics, often in developing countries.

Conclusion: the denationalization of the Social as a way forward

Public social policy was institutionalized at a time of intense nation-state building; it was shaped by, and contributed to the closure of the Westphalian system of social protection. Today’s globalization processes in general, and population mobility and cross-border

dynamics of social problems in particular, challenge such framings of social problems and policy interventions. The ‘mobility turn’ within the social sciences has brought forward relevant theoretical tools and perspectives for the unbounding of the social from such national framings. The role of this chapter has been to contribute to this debate by reviewing two kinds of social policy developments in which this unbounding is evident, though varying in scope and dynamics. The first relates to social policy as state-led public policy and how territorially bounded policies respond to transnational situations. The second concerns manifestations of social policy beyond the state-led sphere.

Drawing on a single case study of the historical development of the basic protection of the Swedish national old-age pension scheme, we make a case to show how the dynamics of public social policy, at least in some instances, contribute to segmentations between poor and wealthy, and with particular implications for mobile populations. Against the

perspective of the unilateral regulation, national citizenship has become insignificant. Instead, what is at stake is earning capacity and domicile. This means that while individuals with sufficient income can emigrate and maintain access to their pensions, persons who have insufficient income for eligibility for the Income Pension cannot. They must remain in Sweden to maintain access to their Guaranteed Pension. In the same vein, for persons who have pension rights from other countries, in most cases these are only transferable among more wealthy countries, which is also the case of Sweden. In this way public social policy functions not only to reproduce global inequality within its population, but it also offers a denationalized protection scheme for the wealthy while the poor remain within

territorialized frames. On the one side, this development signifies a move towards a more insurance-like set-up for the wealthy; on the other, it resembles older methods used to regulate, which continue to exist in many countries today where the poor are tied more strictly to a particular (territorial) local authority, while the wealthy are allowed to move freely.

As our second case we took the example of public health. We noted the broader mandate given to the WHO and the fact that professional networks, philanthropic associations and commercial corporations are increasingly involved in processes of capacity-building for disease-tracking. These processes carry implications for the provision of health care and

measures of a denationalized public health, making international organisations and other actors more important than they were in the era of international cooperation. Of particular relevance here is how denationalization of social policy is based on philanthropic grounds, with implications for transparency and governance. This in particular rises questions about the who and the what dimensions of the transnational social question, questions so central to policy analysis.

In their different ways, both examples illustrate how social policies that hitherto have been deemed as quintessentially ‘national’ are responding to transnational situations. To what extent this shift can yet be described in terms of a ‘denationalization of the social’ is not entirely clear. However, if we think in terms of a ‘way forward’, then the prospect of a denationalized epistemology for understandings of transnational dimensions of social policy and social protection at varying scales appears to be an attractive way forward. Certainly when thinking of access to social rights and social justice, it may well be the case that greater attention to the interaction of social policy at local, national and global scales could help to offset the inherent social inequalities that exist both within and among national states.

References

Basch, Linda, Nina Glick Schiller and Cristina Szanton Blanc (1994), Nations Unbound:

Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments and Deterritorialized Nation-states, Basel:

Gordon and Breach.

Bashford, Alison (2006), ‘Global biopolitics and the history of world health’, History of the

Human Sciences, 19 (1), 67–88.

Beck, Ulrich (2000), ‘The cosmopolitan perspective: sociology of the second age of modernity’, British Journal of Sociology, 51 (1), 79–105.

Brunori, Paolo and Marie O’Reilly (2010), Social Protection for Development: A Review of

Definitions, Munich: Munich Personal RePEc Archive, MPRA Paper No. 29495, accessed 29

June 2019 at http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/29495/.

Clarke, John (2005), ‘Welfare states as nation-states: Some conceptual reflections’, Social

Policy and Society, 4 (4), 407–415.

Esping-Andersen, Gøsta (1990), The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Faist, Thomas (2000), The Volume and Dynamics of International Migration and

Transnational Social Spaces, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Faist, Thomas (2009), ‘The transnational social question: Social rights and citizenship in a global context’, International Sociology, 24 (1), 07–35.

Ferreira, Maurizio (2005), The Boundaries of Welfare: European Integration and the New

Spatial Politics of Social Protection, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fidler, David (2003), ‘SARS: political pathology of the first post-Westphalian pathogen’, The

Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics, 31 (4), 485–505.

Fidler, David and Lawrence Gostin (2006), ‘The new international health regulations: An historic development for international law and public health’, The Journal of Law, Medicine

and Ethics, 34 (1), 85–94.

Holzmann, Robert and Jacques Wels (2018), ‘The portability of social rights of the United Kingdom with the European Union: Facts, issues, and prospects’, European Journal of Social

Security, 20 (4), 325–340.

Kuhn, Thomas (1962), The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Chicago, USA: University of Chicago.

Lakoff, Andrew (2007), ‘Preparing for the next emergency’, Public Culture, 19 (2), 247–271. Lakoff, Andrew (2010), ‘Two Regimes of Global Health’. Humanity: A Journal of Human

Rights, Humanitarianism and Development, 1 (1), 59–79.

Lightman, Ernie (2012), ‘Transnational social policy and migration’, in Adrienne Chambon, Wolfgang Schröer and Cornelia Schweppe (eds.), Transnational Social Support, New York, USA and Milton Park, UK: Routledge, pp. 13–29.

Meyer, John W. and David Tyck (1979), ‘Public education as nation-building in America’,

American Journal of Sociology, 85 (3), 591–613.

Paul, Ruxandra (2017), ‘Welfare without borders: unpacking the bases of transnational social protection for international migrants’, Oxford Development Studies, 45 (1), 33–46.

Polanyi, Karl (1944), The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our

Time, Boston, USA: Beacon Press.

Reubi, David (2017), ‘A genealogy of epidemiological reason: saving lives, social surveys and global population’, BioSocieties, 13 (1), 81–102.

Righard, Erica (2017), ‘Transnational social responsibility: the case of the Swedish retirement pension, 1913–2013’, in Luann Good Gingrich and Stefan Köngeter (eds.), Transnational

Social Policy: Social Welfare in a World on the Move, London: Routledge, 243–261.

Roberts, Stephen and Stefan Elbe (2017), ‘Catching the flu: syndromic surveillance, algorithmic governmentality and global health security’, Security Dialogue, 48 (1), 46–62. Rueschemeyer, Dietrich and Theda Skocpol (1996), States, Social Knowledge and the Origins

of Modern Social Policies, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sabates-Wheeler, Rachel and Rayah Feldman (eds.) (2011), Migration and Social Protection:

Claiming Social Rights Beyond Borders, Basingstoke: Palgrave/Macmillan.

Sabates-Wheeler, Rachel, Johannes Koettl and Johanna Avato (2011), ‘Social security for migrants: a global overview of portability arrangements’, in Rachel Sabates-Wheeler and Rayah Feldman (eds.), Migration and Social Protection: Claiming Social Rights Beyond

Borders, Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 91-117.

Sassen, Saskia (2010), ‘The global inside the national: a research agenda for sociology’,

sociopedia.isa, accessed 29 June 2019 at http://saskiasassen.com/PDFs/publications/the-global-inside-the-national.pdf.

Sheller, Mimi & John Urry (2006), ‘The new mobilities paradigm’, Environment and Planning

A, 38, 207–226.

Swedish Government (2010), Ålderspension för invandrare från länder utanför

OECD-området, SOU 2010: 105 [ Old-age Pension for Immigrants from Countries Outside of the OECD Area, Swedish Government Report 2010:105 ], Stockholm: Regeringen.

Soysal, Yasemin Nuhoğlu (1994), Limits of Citizenship: Migrants and Postnational

Membership in Europe, Chicago, USA: The University of Chicago Press.

Thomas, Lindsay (2014), ‘Pandemics of the future: disease surveillance in real time’.

Surveillance and Society, 12 (2), 287–300.

Tilly, Charles (1975), ‘Reflections on the history of European state-making’, in Charles Tilly (ed.), The Formation of National States in Western Europe, Princeton, USA: Princeton University Press.

Urry, John (2000), Sociology Beyond Societies: Mobilities for the Twenty-first Century, London: Routledge.

Wagner, Peter, Carol Hirschon Weiss, Björn Wittrock & Hellmut Wollmann (eds.) (1991),

Social Sciences and Modern States. National Experiences and Theoretical Crossroads,

Weir, Lorna and Eric Mykhalovskiy (2010), Global Public Health Vigilance: Creating a World

on Alert, New York: Routledge.

Wimmer, Andreas and Nina Glick Schiller (2003), ‘Methodological nationalism, the social sciences, and the study of migration’, International Migration Review, 37 (3), 576–610. Yeates, Nicola and Chris Holden (eds.) (2009), The Global Social Policy Reader, Bristol: Policy Press.