The European Union and Georgia

An Effective Approach to Conflict Resolution?

Pascal Jahn

European Studies: Politics, Societies, and Cultures Bachelor Thesis

15 ECTS Autumn, 2020

Abstract

Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the two de-facto regimes of Abkhazia and South Ossetia have fought actively for their independence from Georgia and international recognition, until the conflict in the Southern Caucasus has reached a frozen status quo in 2008. To maintain peace in the region and to ultimately achieve a resolution of the conflict, the European Union (EU) has become actively involved as an external mediator and has introduced several bilateral agreements and monitoring measures. In this thesis, the EU’s conflict resolution mechanisms towards the territorial and political conflict in Georgia are evaluated through an input-output analysis to answer to which extent these measures are effective or not. Obstacles like identarian differences between the conflicting parties have to be considered, and political, as well as economic motivations for bigger actors, that hinder this process. The result of the evaluation is that in the field of conflict prevention, the EU’s measures and implemented policies are contributing effectively, while the active promotion of conflict transformation or conflict settlement is only achieved to a small degree, and is not effective within the current approach.

Keywords: Georgia, Effectiveness, Conflict Resolution

Abbreviations

ABL Administrative Boundary Line

CIS Commonwealth of Independent States

EaP Eastern Partnership

ENP European Neighborhood Policy

EU European Union

EUMM European Union Monitoring Mission

EurAsEc Eurasian Economic Union

EUSR European Union Special Representative

GID Geneva International Discussions

IDP Internally Displaced Persons

NREP Non-Recognition and Engagement Policy

OSCE Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe

TEU Treaty on European Union

Table of Contents

1. Introduction 4

2. Research Question 5

2.1. Thesis Outline 6

2.2. Aim of the Thesis 7

3. Research Landscape 8

4. Theoretical Framework 12

4.1. Theoretical Approach 12

4.2. Methodological Approach 14

4.3. Significance of the Subject 15

4.4. Choice of Sources and Cases 16

5. Historical Background of the Southern Caucasus and the Conflict 17

5.1. Abkhazia and South Ossetia since 2008 20

6. Incentives for International Involvement 21

7. Policy Analysis 24

7.1. The EU approach to Conflict Resolution 25

7.2. Conflict Resolution in Georgia 29

7.2.1 The European Neighborhood Policy and Eastern Partnership 30

7.2.2. EU-Georgia Association Agreement 33

7.2.3. The Georgian State Strategy on Occupied Territories 35 7.2.4. EU Non-Recognition and Engagement Policy 36

7.2.5. EU Monitoring Mission in Georgia 37

8. Evaluation 39

9. Conclusion and Prospects 41

1.

Introduction

Georgia, located in the Southern Caucasus by the Black Sea, is surrounded by some of the biggest global actors, namely Russia, Turkey, and Iran. A small country that was, and still is subject to heavy external cultural, political, and economic influence. Despite having been part of the Persian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, as well as the Soviet Union, it managed to guard its own identity and ultimately become a sovereign nation in the 20th century. However, that does not mean that these 1

influences have not left their scars. Conflicts within the internationally recognized Georgian territory have resulted in wars and humanitarian crises, especially in the two separatist de-facto regimes of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which have declared their independence after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Together with political perspectives that are mainly shared with other international actors among Georgians, Abkhaz and South Ossetians, identarian differences are the reasons for a now frozen conflict. 2

There is, however, another important actor involved, with the primary objective of resolving this conflict: The European Union (EU). Due to the geographical proximity of Georgia to the EU’s 3

borders and the fact that the Southern Caucasus is by definition part of Europe, as well as the EU’s political and economic interest in maintaining peace in its immediate neighborhood, the EU has decided to make efforts in establishing closer relations with Georgia. The EU’s most important 4

and far-reaching program to stabilize and resolve conflicts in its neighborhood, is the European Neighborhood Policy (ENP), an approach aiming to create a “ring of friends, with whom the EU enjoys close, peaceful and co-operative relations”. As part of this policy, the Eastern Partnership 5

(EaP) was formed after the violent escalation of the conflict in 2008, aiming specifically towards European post-Soviet states, just like Georgia.

E. Suleimanov, Understanding Ethnopolitical Conflict: Karabakh, South Ossetia, and Abkhazia Wars Reconsidered, Palgrave

1

Macmillan, Hampshire, 2013, p. 71.

T. de Waal and N. von Twickel, Beyond Frozen Conflict: Scenarios for the Separatist Disputes of Eastern Europe, Rowman &

2

Littlefield International, 2020, p. 191.

F. Schimmelfenning and U. Sedelmeier, ‘The Study of EU Enlargement: Theoretical Approaches and Empirical Findings’, in M.

3

Cini and A. Bourne (ed.), Palgrave Advances in European Union Studies, Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire, 2006, p. 102. M. Frichova Grono, ‘Georgia’s Conflicts: What Role for the EU as Mediator?’, IFP Mediation Cluster, Initiative for

4

Peacebuilding, 2010, p. 7.

‘Wider Europe - Neighbourhood: A New Framework for Relations with our Eastern and Southern Neighbours’, 104 final, COM

5

The question that comes up is, whether the policies and mechanisms used by the EU in the ENP to resolve the frozen territorial conflicts in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, are indeed fulfilling their objectives; in other words, if, or to which extent they are effective means to do so. They range from fundamental, multilateral agreements to very specific policies or missions. The performance of these policies and mechanisms will be analyzed in my thesis through the concept of ‘Effectiveness’. Due to the fact that it is difficult to understand why and how the EU’s instruments impact the different conflicting parties, I will give background information about the origins of these conflicts and the complex history of the Southern Caucasus. Most importantly and as the main part of this thesis, I will evaluate and elaborate on the measures already taken to achieve the goal that is in the best interest of all involved actors, to ultimately answer the question of how effective the EU’s conflict resolution mechanisms are in Georgia. By doing so, it is essential to consider the actors’ incentives that range from economic benefits to security policies and identity.

The evaluated cases are: Conflict prevention, conflict transformation, international conflict management, and conflict settlement. They rate as the four main subcategories of the EU’s conflict resolution approaches, which are treated separately when analyzing the different policies and actions taken towards the situation in Georgia. This model is essential for my purpose. It was brought forward by Bruno Coppieters, using a comparative toolkit, including traditional concepts of negotiation, mediation, and diplomacy. However, the separate realization of these policy 6

objectives does not imply that they should be achieved in sequence but rather pursued in parallel and interlinked with one another, according to their respective applicability and implementation possibilities. “Steps taken within one of the policy objectives will have an immediate effect on the others, while the (sole) emphasis of one objective may happen at the expense of (the) others”. 7

2.

Research Question

The research question worked with in this thesis is: ‘To what extent are the European Union’s

conflict resolution mechanisms within the European Neighborhood Policy towards the territorial and political conflict in Georgia regarding Abkhazia and South Ossetia effective?’

B. Coppieters, ‘The EU and Georgia: Time Perspectives in Conflict Resolution’, Occasional Paper, European Union Institute for

6

Security Studies, 2007, pp.9-13.

E. Jeppsson, ‘A Differentiated, Balanced and Patient Approach to Conflict Resolution? The EU’s Involvement with Georgia’s

7

2.1. Thesis Outline

After precisely explaining the problem of the topic and classifying its importance on the greater political scale, I will start by introducing the research field as a whole and locate my topic within it. This introduction includes understanding the previous research that has been done in ENP studies, evaluating conflict resolution mechanisms and instruments in general, and, most importantly, performance analysis of policies and the effectiveness of the implementation of these mechanisms to the case of Georgia. The theories, concepts, sources, and methods brought forward and used in previous research approaches will also influence the following parts of the thesis. As there are different means to analyze a problematic case, I will, in the next step, define the theoretical and methodological framework that suits my topic best.

The conflict in Georgia has many different causes and actors to it and is interdisciplinary. Conceptual combinations, including conflict theory, nationalism, enlargement theory, and Europeanization, all make legitimate sense and must not be disregarded. This thesis, however, focuses solely on the evaluation of the EU’s policies’ effectiveness. Thus, the former will only be used to understand the background and the motivation behind the implementation of said policies. The used concept of ‘Effectiveness’ requires specific criteria or a scale to be able to conduct an unbiased evaluation, which will be introduced as the methodological tools. By introducing the choice of sources and cases, most essentially understanding implemented policies and bilateral agreements, and critically reflecting on them, as well as explaining how the research will be conducted, I will form a guideline for the subsequent analysis. 8

The central part of this thesis will be the analysis of the EU’s policies used in context with the conflict in Georgia. It will consist of three interlinked sections: The first area covered is a background of Georgia’s history within the Southern Caucasus, including the origins of the territorial and political, multi-dimensional conflict. This is crucial for understanding the incentives and premises for the involvement of all actors and the reasoning for potential reluctance to implement more effective measures. Secondly, the mechanisms that the EU uses in conflict resolution matters as part of its foreign policy, including their questionable effectiveness and the premises for success. Thirdly, and comparatively based on the EU’s general approaches, the

A. Bryman, Social Research Methods, Oxford University Press, New York, 2012, pp. 627-652.

analysis of the most representative and influential policies and instruments used in this specific case, the reasons behind their establishment, and the impact they have on an international, as well as national level. Following these sections, a summary will evaluate and conclude the findings.

2.2. Aim of the Thesis

The aim of this thesis is to create a link between the EU’s conflict resolution policies and a specific case where they are being applied and outline whether these policies impact the development of the conflict enough, to meet their very objectives, in other words, whether their performance is effective or not. The academic field of conflict resolution studies ranges widely, and so do the cases that serve as subjects for these studies. The instruments, policies, and measurements taken by the EU to approach and mediate conflicts play a key role, not only on the internal level but affect the whole international community, especially the EU’s immediate neighbors. They demonstrate how the EU systematically uses strategies based on its values and 9

economic incentives to reach specific goals, that in the short or long run, benefit itself and the concerned subjects that, in this case, are Georgia, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia. While there are many examples of EU engagement in resolving unstable situations all around the world and even in the Southern Caucasus, the situation in Georgia allows for a profound analysis of the implications of the used strategies, as well as an observation of their effective or non-effective performance, because of the comparatively high level of conflict alternation since 2008. 10

Several additional questions will support the analysis. Those are firstly, defining what requirements have to be met to rate the implementation of a policy as effective, secondly, what specific approaches the EU has chosen in the case of the Southern Caucasus and why, thirdly, how they have influenced the situation in Georgia since its implementation, and fourthly, evaluating the effectiveness of the implied measures from a comparative input-output perspective. 11

M. Frichova Grono, ‘Georgia’s Conflicts: What Role for the EU as Mediator?’, p. 20.

9

Ibid.

10

T. Schumacher et al. (ed.), The Routledge Handbook on the European Neighborhood Policy, Routledge, New York, 2018, pp. 3ff,

11

3.

Research Landscape

Having started to locate the topic in the broader field of European- and conflict studies, the precise position from which to conduct further research has to be defined. Therefore, I will give an overview of previous research focused on the EU’s role as a mediator and the evaluation of ENP measures, introducing three seminal approaches and concepts; ‘Actorness’, ‘Performance’, and ‘Effectiveness’, including their implementation and controversies in a more detailed manner, ultimately narrowing down a vast problem area to a defined research gap. 12

When approaching conflict solving means, the question arises, how the EU is perceived as an international actor, and why the EU acts beyond its borders in the first place. The concept of ‘Actorness’ is described by Hoffmann and Niemann as the ability of a state or another global actor to “put forward (…) a set of material stimuli and normative demands to reward alignment (…) in third countries”. The EU is therefore an actor within the ENP itself, and so is Russia, for 13

example, through the involvement and assertiveness that extend beyond their globally recognized borders. Because the EU is a supranational construct consisting of multiple smaller actors, Jupille and Caporaso have brought forward four main indicators when analyzing EU Actorness: Autonomy (The distinctiveness and independence of the decision-making apparatus in the institution), authority (Legal competence delegated to the institutions by the member states), coherence (formulating an internally consistent position), and recognition (Acceptance by and interaction with other international actors). By fulfilling these premises, the EU is given the 14

ability to act on an international level and, most importantly, legitimizes its intervening role when analyzing developments in other regions. The taken measures like sanctions or policies, and the relation between external incentives and successful consolidation of the conflict are interlinked.

The problem with this approach, especially in the EaP is the complexity and ambiguity of the requirements. While recognition and autonomy are relatively clear and preconditioned in most bi- and multilateral relations, and authority is only discussed when assessing EU enlargement, coherence is a commonly examined factor when studying the EU’s role towards neighboring

A. Bryman, Social Research Methods, p. 8.

12

N. Hoffmann and A. Niemann, ‘EU Actorness and the European Neighbourhood Policy’ in T. Schumacher et al. (ed.), The

13

Routledge Handbook, p. 33.

J. Jupille and J. Caporaso, ‘States, Agencies and Rules: The European Union in Global Environmental Politics’, in C. Rhodes

14

states. Manners, as well as Bosse, have shared concerns about the coherence of shared values within the EU and the influence that these values have on third countries. Dobrescu and 15

Schumacher argue, that on an international level, the most important actors are the states, and not international unions like the EU, as they possess more political, economic, military, and ideational power. In contrast, Tulmets uses a more constructivist approach and argues that it is precisely this 16

internal inconsistency, which makes the ENP successful and increases expertise in neighboring countries. 17

‘Actorness’ means not only the ability to externally influence developments through presence, but also the capability of performing effectively and influentially as an actor. Another mean to 18

evaluate EU policies is through the analysis of ‘Performance’. This concept aims to more specifically answer the question of how the EU intervenes in its near neighborhood, in this case the EaP, rather than why. But why should the performance of the ENP be analyzed? What is the reason for an assessment, and how should the results then be used to attain the desired goal?

Various authors have written about the importance of the establishment of the ENP as an instrument to achieve political stability and economic amelioration in the EU’s immediate neighborhood, through institutional actions and with the help of crucial concepts like borders, identity, and values. The omnipresent pursuit of national enlargement has, to an extent, found its 19

alternative in the ENP. From a constructivist view, this approach achieves the same political and economic benefits as hard enlargement does, namely through a blur of internal relations with member states, and external relations with non-member states. Analyzing and evaluating the 20

performance of these policies is important, but also risks of being ambiguous, because it is linked to the individual judgment of what is the ideal performance. While the EU’s aim is to create a 21

ring of friends around its external borders, unfortunately, it is surrounded by hotspots of instability,

N. Hoffmann and A. Niemann, The Routledge Handbook, p. 33.

15

M. Dobrescu and T. Schumacher, The Politics of Flexibility: Exploring the Contested Statehood–EU Actorness Nexus in Georgia,

16

Geopolitics, 25:2, 2020, p. 412. N. Hoffmann and A. Niemann, p. 33.

17

M. Dobrescu and T. Schumacher, p. 412.

18

T. Schumacher, et al. (ed.), The Routledge Handbook, pp. 17ff, 70ff, 435ff.

19

F. Schimmelfenning, ‘Beyond Enlargement: Conceptualizing the Study of the European Neighbourhood Policy’ in T. Schumacher

20

et al. (ed.), The Routledge Handbook, p. 17.

D. Baltag and I. Romanyshyn, ‘Analysing the Performance of the ENP’ in T. Schumacher et al. (ed.), The Routledge Handbook,

21

in Northern Africa or the Middle East, and also in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus. As the focus of the ENP is shifting from promoting and developing to achieving and maintaining stability, democracy, law, and prosperity, the evaluation and review of these policies help to improve and control the chosen instruments and mechanisms. 22

‘Performance’ is an overarching and multi-dimensional concept. In order to measure this otherwise ambiguous notion, it needs to be narrowed down to one of its components (Coherence, relevance, effectiveness, and impact), to achieve a measurable result. Mnatsakanyan, for instance, assesses 23

the EU crisis management with a focus on South Ossetia through the concept of coherence and Actorness, analyzing not only the EU’s external, but also the inter- and intra-institutional relations, and the problems that arise by disregarding them. Frichova Grono, a crucial author questioning 24

the EU’s role as an external mediator in Georgia, argues that the involvement has had limited results so far, not least due to the conflict’s multilateral nature, issues of legitimacy and acceptance, and the EU’s pursuit of impartiality. 25

As another integrated part of ‘Performance’, ‘Effectiveness’ proves to be the most prominent and widely discussed concept concerning the measures and impact of the ENP, as well as the Southern Caucasus. By focusing on ‘Effectiveness’, and less on the variable of efficiency, namely whether 26

a result could have been attained with fewer resources or less effort, the main target is the outcome, which, when aiming to solve a conflict, should always be the most important, especially given the high number of resources the EU has. Simultaneously, many scholars choose to analyze ‘Effectiveness’ through the input-output method, to directly compare the objectives of a policy with the implementation of such and the developments in the chosen field. For example, Weber evaluates the effectiveness of the ENP in EaP countries, focusing on the sectors of energy and internal security, with the help of this method. Naturally, the former requires the observation of 27

costs and incentives, therefore, also including elements of efficiency analysis.

D. Baltag and I. Romanyshyn, The Routledge Handbook, p. 39.

22

D. Baltag and I. Romanyshyn, p. 41.

23

I. Mnatsakanyan, ‘The Quest for Coherence in EU Crisis Management in the South Caucasus: The Case of South Ossetia’,

24

Europolity, 12:2, 2018, p. 87ff.

M. Frichova Grono, ‘Georgia’s Conflicts: What Role for the EU as Mediator?’.

25

N. Hoffmann and A. Niemann, The Routledge Handbook, p. 34.

26

B. Weber, ‘The Effectiveness of the European Neighborhood Policy in the Eastern Dimension in the Policy Fields of Energy

27

When evaluating conflict resolution mechanisms in Georgia, ‘Effectiveness’ is the most promising concept to use, because it allows for the concrete observation of developments, which have shown to be changing quite rapidly in the Eastern European neighborhood, European post-Soviet countries, and the Southern Caucasus. In this case, evaluatory criteria are applied to the case of Abkhazia and South Ossetia by suggesting and making use of possible settlement options, as done comparatively by De Waal and Von Twickel. These options are certainly helpful to explore future prospects, although not crucial. So-called ‘frozen conflicts’ have, namely, emerged not only in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, but also in Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh), Transnistria, the Donbas (Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts), and the Crimean Peninsula. 28

As a political scientist, focusing on de-facto states, and even coordinating an EU financed teaching project for the Abkhazian State University in 2012, Coppieters has introduced the four different options for conflict settlement that the EU can pursue. The criteria that emerge from the 29

application to the case of Georgia, serve as the perfect input for a comparative analysis of ‘Effectiveness’. This has been previously done by Jeppsson, who calls the EU’s approach a differentiated, balanced, and patient one. In contrast, Tulmets argues, that the expectations and 30

incentives the EU brings forward, overshadow those that benefit the neighboring countries. 31

A major controversy when writing about the Abkhaz and South Ossetian crisis, is how one interprets the manner in which certain things have happened and why, rather than what has happened. As the main reason behind this problem area is the conflict between the breakaway republics and Georgia, but also between Georgia and Russia, it depends on perspective. For instance, the Georgian and EU position speaks of the occupation of Abkhazia and South Ossetia by Russia, while the Abkhaz and South Ossetian position declares the secession from Georgia as a completed process. It is extremely problematic to write about a conflict that is still ongoing and 32

cannot be studied as a completed subject, without being biased, especially regarding the ambiguity of the concept of effectiveness. This is why delimitations and criteria for the analysis are to be clearly defined in the theoretical framework.

T. de Waal and N. von Twickel, Beyond Frozen Conflict, pp. 15-51, 159-201.

28

‘Bruno Coppieters’, Vrije Universiteit Brussel,

https://cris.vub.be/en/persons/bruno-coppieters(cd86987e-7bbe-4171-29

a83b-5c5e698cc7b2).html, (15.08.2020).

E. Jeppsson, ‘A Differentiated, Balanced and Patient Approach to Conflict Resolution?’.

30

N. Hoffmann and A. Niemann, The Routledge Handbook, p. 35.

31

T. de Waal and N. von Twickel, p. 162.

4.

Theoretical Framework

To help analyze and understand the ENP as a whole, and evaluate the performance of its policies towards the case of Georgia, I will choose a theoretical framework. A theory is needed in social studies to explain why certain observed things happen or have happened, as well as choosing a point of view from which to analyze a problematic case. Given the structural complexity and the 33

multi-level-nature of the ENP, especially the blurring between internal and external objectives, finding one single appropriate set of concepts to analyze its performance is not possible and requires a specific narrowing-down of the theoretical framework in accordance to the two-layered analysis, as well as concerning the methodological approach for an unbiased evaluation of the chosen cases. This is mainly due to the multitude of countries and political and institutional 34

arrangements covered by the ENP, which all behave differently and only overlap in very specific circumstances and under the same premises, in this case, other post-Soviet territorial conflicts that the EU aims to resolve, and where the performance is evaluated.

The second difficulty lies within the inconsistency of the actor’s interests over time. The analysis needs to be set within a certain time frame. Because the main targets that the ENP is aimed at, continuously move throughout the years and from one hotspot to another, observing the implementation of the ENP requires a constant update of the EU’s interests, but also on the changing conditions at the receiving ends. 35

4.1. Theoretical Approach

The selection of the theory is adapted to fit both the diverse and broad international coverage of EU conflict resolution mechanisms, as well as the specific case of Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Georgia. As a subcategory of performance analysis, the concept of ‘Effectiveness’, is of a two-sided, comparative nature, just like the method that it will be approached with. In the following paragraphs, the theory will be justified and motivated in clear relation to the research topic.

A. Bryman, Social Research Methods, p. 21.

33

T. Exadaktylos, ‘Methodological and Theoretical Challenges to the Study of the European Neighbouhood Policy’, in T.

34

Schumacher et al. (ed.), The Routledge Handbook, p. 99. T. Exadaktylos, p. 100.

In its’ purest form, the term being ‘effective’ means the degree to which something is successful in producing a desired result. No matter what discipline or form this cross-cutting theory is used in; law, economics, or in this case, international politics, the core idea remains the same. This must, 36

however, not be confused with efficiency, where instead of having the goal of obtaining the highest quality result, the profitability, or cost-benefit-relation is decisive. In the case of international 37

politics, the most common definition of effectiveness is goal-attainment or problem-solving by actors. Even though the analysis of such can be problematic, for example when goals are 38

formulated vaguely or when they range in difficulty to achieve, in the case of the EU’s external actions, especially towards its’ immediate neighbors, the goals are specifically oriented towards them, including those of conflict resolution. 39

Applying this theory to the analysis of the EU’s external actions, where the goal is most commonly a change in behavior or interests of actors, allows one to look at the ENP’s role in the development of the conflict in the Southern Caucasus comparatively. Does it achieve its goals, and does it solve the problems effectively? This concept of ‘Effectiveness’ aims to record, assess, and evaluate the impact and target achievements of policies. Through its analysis, future approaches can be 40

precisely targeted and better coordinated, therefore, ameliorated. The instruments and mechanisms used in Georgia naturally follow general goals of peace-building, democracy-promotion and stability-creation, as listed in Article 21 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), but are mainly based on Sarkozy’s Six-Point Agreement, as elaborated on in Chapter 5.1.. The concept is 41

problematic in itself due to its interpretative nature, especially the fact that the objectives of the ENP are often ambiguous (What is stability? When is a situation secure?). 42

This thesis assesses the ENP’s goal-achievement capability and its impact on domestic transformations that occur in Georgia, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia, which can be associated directly with EU leverage and incentives. For the evaluation of the EU’s impact, a policy is rated 43

D. Baltag and I. Romanyshyn, The Routledge Handbook, p. 45.

36

B. Krems, ‘Effektivität, Effizienz’, Online-Verwaltungslexikon, 29.02.2014, https://olev.de/e/effekt.htm, (13.08.2020).

37

N. Hoffmann and A. Niemann, The Routledge Handbook, p. 31.

38

D. Baltag and I. Romanyshyn, p. 43.

39

B. Weber, ‘The effectiveness of the ENP (...)’, p. 40.

40

‘Consolidated version of the Treaty on European Union’, Official Journal of the European Union, 09.05.2008, p. 115/28,29.

41

D. Baltag and I. Romanyshyn, p. 44.

42

N. Hoffmann and A. Niemann, p. 34.

as effective when its objectives conform with the achieved developments in the conflict situation, in other words, achieve what it is meant to achieve.

4.2. Methodological Approach

The methods used in previous research were adapted to the interdisciplinary nature of the ENP and used more or less intensively in different fields and frameworks. Exadaktylos lists ‘(foreign) policy analysis’ and ‘comparative politics’ as the most widely analyzed ENP fields, followed by ‘international identity (incl. identity construction)’. As part of the performance analysis approach 44

towards its application to the field of the Southern Caucasus, policy analysis turns out to be the most efficient one.

In a narrower sense, the central method used to connect the pieces of the gathered information is a two-layered analysis of EU policies. Firstly, the EU’s conflict resolution approaches build a framework for the more specific dissection and interpretation of the case-related policies, documents, strategies, bilateral agreements, as well as contemporary progress reports. Secondly, the progress of actions is measured through an ‘Input-Output Analysis’ directly in the geographical, and therefore also the political sector that they are applied to. This model is 45

borrowed from economics and is used to measure resources like time, money, or expertise within process management. According to Easton, in political science, ‘input’ or policy-input refers to 46

the inputs into political decision-making processes and the subsequent policy implementation. This can consist, for instance, of articulating and communicating political interests, or forming objectives to achieve a specific goal. In contrast, the ‘output’ or policy-output stands for the results of the used policies in a particular case. In the case of this thesis, the progress of actions is 47

equated with the effectiveness of measures taken by the EU (input) towards resolving the conflict in Georgia and changing environments within (output). The precise policy-related criteria for the evaluation, and the premises for objectives to meet in order to be rated effective are elaborated in Chapter 7.1..

T. Exadaktylos, The Routledge Handbook, p. 99.

44

S. Dera, ‘Das politische System David Eastons - Eine generelle Theorie?’, Studienarbeit, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität, 1999,

45

p. 9.

D. Baltag and I. Romanyshyn, p. 40.

46

S. Dera, p. 4.

The evaluation of effectiveness is done on a virtual, non-mathematical scale, due to the qualitative nature of the science and the fact that the definition of optimal performance is based on the researchers’ view, and can therefore only be measured concretely to a certain degree. This is why 48

the research question includes the term “to which extent” instead of simply asking whether the EU’s measures are effective or not. While the chosen methodological tool aids in putting the results on a virtual scale, certain instruments affect various conflict resolution policies to different extents. That is why this evaluation cannot be done by asking a simple “yes or no”-question. 49

This thesis is designed to use the exemplariness of the frozen conflicts in Georgia, and apply to them the EU’s conflict resolution approaches, by analyzing the Georgian-Abkhaz-Ossetian and the Georgian-Russian relations as a multilateral conflict, and then superimposing and evaluating the EU’s mediation effectiveness. This includes the policies and instruments that have been used in 50

the past, and are currently used today, as well as suggestions for further application in the future. 51

4.3. Significance of the Subject

Exploring these incentives goes hand in hand with understanding why the EU implements foreign policies and why it is important to support the development of third-party nations outside of it. The conflicts in the Southern Caucasus represent an immense obstacle towards regional stability, even on an international scale. Alongside the four post-Soviet conflicts and Northern Cyprus, the de-facto regimes of Abkhazia and South Ossetia are the last remnants of territorial disintegrity in Europe. Achieving a resolution would mean that one more part of Europe is free of conflicts involving active violence. Although possibly criticized by pro-Russian actors, it would strengthen the overall international image of the EU. However, it would undoubtedly lead to economic development, and positive societal change in the Southern Caucasus. The exemplariness of this 52

case is undeniable and, to a large extent, applicable and transferable to similar conflicts all around the world, which is why the determination of possibly effective measures could be beneficial for all of them.

D. Baltag and I. Romanyshyn, The Routledge Handbook, p. 46.

48

E. Jeppsson, ‘A Differentiated, Balanced and Patient Approach to Conflict Resolution?’, p. 9.

49

M. Frichova Grono, ‘Georgia’s Conflicts: What Role for the EU as Mediator?’, pp. 9-20.

50

T. Schumacher, et al. (ed.), The Routledge Handbook, pp. 249ff, 312ff.

51

T. de Waal and N. von Twickel, Beyond Frozen Conflict, p. 53.

4.4. Choice of Sources and Cases

The sources worked with in this thesis are chosen in close relation with the previous research and on the base of the theoretical and methodological concepts. This means that apart from the background literature supporting the evaluation, official documents, policies, and legislations are compared with progress reports, news articles and miscellaneous information, representing the two levels of discourse analysis. These are mainly found on news agencies websites, especially Georgian ones, translated to English, to inform non-Georgian speakers about the developments in the country. To study the actor’s incentives and the policies’ impact, the time frame in which the used sources are analyzed will initiate primarily in 2008, a turning point in the development of the conflict and the first notable involvement of the EU as an external mediator.

The chosen policies in this thesis used to evaluate the effectiveness of the EU’s involvement in the conflict, first of all, have to be representative and exemplary. To achieve this, they are connected with the options that the EU has for approaching a conflict resolution in the first place. While it is indeed possible to select cases randomly and to lower the risk of being biased, the input-output analysis of ‘Effectiveness’ requires sampling those, who are either confirming the positive relation between input and output, meaning the achievement of objectives, or the opposite. However, as both approaches support the same theory, regardless if positively or negatively, they do not necessarily fall under the typical- or deviant-case-selection, which are also part of Seawright and Gerring’s options. A typical case would be one, that clearly conforms with a theory, a deviant case, the opposite. Because the different cases cannot one-hundred percent be assigned to one specific 53

policy, but rather overlap and influence each other, it is essential to look at the whole picture when choosing fitting cases. The instruments that are being analyzed in this thesis, all aim towards one specific objective, and while indeed taking different approaches, they can be categorized under the “most similar”-case selection. This qualitative, comparative method requires the same dependent variable, so that its application to the policies then brings out the differences, or in this case, the degree of effectiveness. The selected cases to compare with the EU’s conflict resolution policies 54

to answer the research question will be analyzed in Chapter 7.2..

J. Seawright and J. Gerring, ‘Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research - A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative

53

Options’, Political Research Quarterly 61:2, Utah, 2008, p. 299. J. Seawright and J. Gerring, p. 304.

5.

Historical Background of the Southern Caucasus and the Conflict

To understand the ongoing political, territorial, and also identarian conflicts in the Southern Caucasus and before talking about the policies and mechanisms that are currently used to resolve the conflict in Georgia, it’s crucial to look into the history of events that led to today’s situation. Without this historical, geo- and ethnopolitical background information, the implementation of policies would seem out of context or disproportionate. The cultural, linguistic, ideological, and national differences are the core reason for the existence of this conflict. They are decisive variables in the Georgian-Abkhaz and Georgian-Ossetian relations that have to be taken into account with every approach taken by any external and internal mediating actor. Only then can 55

their measures be effective.

National identity emerges or rather is created early in the origins of a nation, and develops throughout history. According to Anderson, nations are ‘imagined communities’ because their members, in this case, the citizens, don’t know each other personally because of the spatial separation, but create the idea of a community in their minds. The notions of the nation, just as 56

language, religion, or culture, act as connecting elements within the community and as points of reference for collective identification. Zielonka extends the term ‘identity’ from only shared values of a community to a territorial connection and coherence, that can even be shared across borders. This concept of border-making and identity-formation can be observed in the Southern Caucasus, where ethnicities coexist across contested borders and where different national identities share defined and internationally recognized territories. If, however, these notions are distorted by the 57

creation or shifting of borders, like it is the case with the South Ossetian border, it is almost certain that conflicts emerge and intensify, according to the severity of the change. The necessity and 58

effectiveness of the strategies taken by the EU, especially the EUMM, therefore, go hand in hand with the deeply rooted identarian disintegrity.

J. Zielonka, ‘The EU and the European Neighbourhood Policy: The Re-making of Europe’s Identity’, in T. Schumacher et al.

55

(ed.), The Routledge Handbook, p. 143.

B. Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Verso Books, London, 1983.

56

J. Zielonka, p. 144.

57

T. de Waal and N. von Twickel, Beyond Frozen Conflict, p. 198.

The history of today's conflict in the Caucasus goes back a long way. The peoples of the Caucasus differ from each other religiously, ethnically, socially, and culturally. Notable developments 59

regarding Abkhazia and South Ossetia, have started mainly after the first declaration of independence of Georgia in 1918 from the Russian Empire. The existence of an indivisible Abkhazia was at that time also recognized by Georgia. The same year, South Ossetians tried to 60

break ties with the government in Tbilisi, and a conflict arose, in which rebels tried to force a violent detachment from Georgia. After the annexation of Georgia by the Soviet Union, extensive and exclusive cultural rights were provided for the population in the autonomous region of what is now South Ossetia. However, this went hand in hand with a strong Georgian influence in the linguistic and educational sectors. In the western part of the Southern Caucasus, the Abkhazian 61

Soviet Socialist Republic was founded in 1921 as an independent Soviet republic, which was legally equivalent to all other Soviet republics. However, ten years later, by order of Josef Stalin, it was incorporated into the Georgian Soviet Republic.

Afterward, the Abkhazian cultural rights were curtailed, and efforts to preserve national identity were punished as counter-revolutionary. The situation in regions mostly populated by minorities, particularly in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, was tense. Shortly before Georgia renounced the Soviet Union, major inter-ethnical conflicts and mass demonstrations began. In Abkhazia, the situation escalated, and the demands for state independence became louder and louder. The occasion was the planned opening of a branch of the Tbilisi State University in the Abkhazian capital, representing cultural and linguistic oppression. In 1992, Abkhazia proclaimed independence from Georgia, which quickly lost control of most of the region, and the conflict escalated in violence. 62

The resulting war between the Georgian government and Abkhaz separatists led to ethnic Georgians being largely expelled from Abkhazia, and Abkhazia achieving de facto independence from Georgia. Ethnic violence had also flared up in South Ossetia a year earlier to seek Russian 63

recognition, where it was eventually suppressed. In response to South Ossetia’s declaration of

T. Kunze, ‘Krieg um Südossetien’, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., 12.08.2008.

59

E. Auch, ‘Der Konflikt in Abchasien in historischer Perspektive’, OSZE-Jahrbuch Baden-Baden, 2004, p. 238.

60

T. de Waal and N. von Twickel, Beyond Frozen Conflict, p. 191.

61

E. Suleimanov, Understanding Ethnopolitical Conflict, p. 115

62

E. Auch, p. 244.

independence, Georgia canceled all autonomy rights in the region. This cost the lives of several hundred people, and South Ossetians fled to Russia, while Georgians in South Ossetia fled to Georgia. This phenomenon, called ‘Ethnic Segregation’, is widespread in conflicts across contested borders. It could also be observed in neighboring Azerbaijan when in the course of the 64

Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, interexchange of migration between ethnic Azerbaijanis and ethnic Armenians took place. Up until 2004, the conflicts had reached a relatively ‘frozen’ status quo, 65

characterized by a situation where all conflicting parties have replaced the previous violent conflict by a ceasefire, while each party persists on the enforcement of their objectives and a compromise is impossible because that would mean giving way.

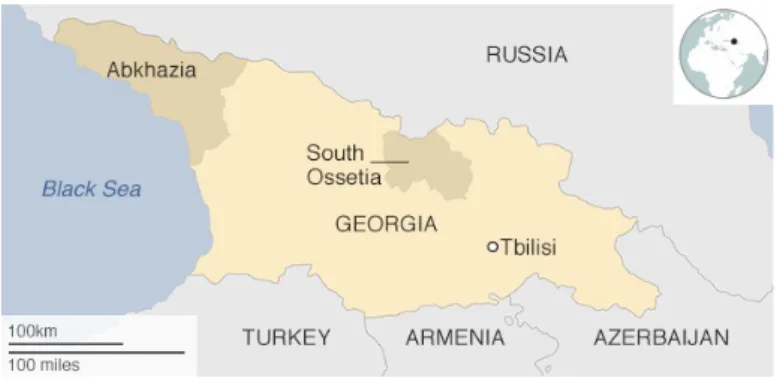

In September 2004, the new Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili presented a plan to the UN, which was intended to reintegrate South Ossetia and Abkhazia into Georgia, even though they technically are on Georgia’s internationally recognized territory, as Figure 1 shows. The two breakaway republics areas rejected the plan, while the relations between Georgia and Russia became more and more problematic. On the other hand, Georgia has also been working closely with the EU since that time, and in his first speech to the European Parliament, 2006, Saakashvili even campaigned for an accession perspective. 66

Figure 1. The two breakaway republics of Abkhazia and South Ossetia within the internationally recognized borders of Georgia. 67

J. Rex, ‘The Nature of Ethnicity in the Project of Migration’, in M. Guibernau and J. Rex (ed.), The Ethnicity Reader, Polity

64

Press, Cambridge, 1997, p. 275.

T. de Waal and N. von Twickel, Beyond Frozen Conflict, p. 206.

65

B. Riegert, ‘Präsident Georgiens wirbt in Straßburg für EU-Annäherung’, DW, 16.11.2006,

https://www.dw.com/de/präsident-66

georgiens-wirbt-in-straßburg-für-eu-annäherung/a-2240619, (11.05.2020).

S. Goyashko, ‘South Ossetia: Russia pushes roots deeper into Georgian land’, BBC News, 18.08.2018, https://www.bbc.com/

67

5.1. Abkhazia and South Ossetia after 2008

While the EU had been bringing forward conflict transformation and internal development initiatives to the affected regions, it is the events that took place in and after 2008 that mark the first significant involvement of the EU in the conflict, as well as the first measures actively taken to resolve it. After the EU had declared a referendum on independence from South Ossetia as 68

invalid, and a Georgian drone, which had entered the airspace above Abkhazia, was shot down by a Russian fighter plane, the armed conflicts intensified and resulted in the Caucasus War 2008 which included five days of active hostilities. Georgian troops entered the South Ossetian capital 69

of Tskhinvali, where fights between the Russian forces stationed there and the Georgian military broke out. The same happened at the Abkhaz-Georgian border in the Kodori Gorge, which was held by Georgia at the time. The Abkhazian authorities mobilized their army, and the Russian troops in the area were augmented, but later retreated in the course of the ceasefire.

The exact number of fatalities is disputed, but the consequences of the war were tragic. Hundreds of civilians were killed, war crimes were committed, and nearly 160.000 people fled from Abkhazia and South Ossetia to Georgia and Russia. Furthermore, the damage done to the Abkhaz 70

and South Ossetian economy and infrastructure is immense. Due to Russia’s heavy involvement, this conflict is also called the ‘Georgian-Russian War’. The reason for this involvement is the support for the two breakaway republics as well as the maintenance and strengthening of Russian influence in its near neighborhood. Georgia and Russia have, subsequently, cut off all bilateral relations. As a result of the outbreak of the war, the EU took the urgently needed role of a mediator. Nicolas Sarkozy, who was at that time president of the European Council, proposed a six-point ceasefire plan for the resolution of the 2008 Caucasus conflict itself, but also as a first step towards a long-term solution. 71

The plan was later signed by South Ossetia and Abkhazia, Georgia, and Russia. It consists of the following principles:

M. Frichova Grono, ‘Georgia’s Conflicts: What Role for the EU as Mediator?’, p. 12.

68

‘Georgia: UN says Russian air force shot down aircraft over Abkhazia’, UN News, 27.05.2008, https://news.un.org/en/story/

69

2008/05/260732-georgia-un-says-russian-air-force-shot-down-aircraft-over-abkhazia, (11.05.2020). M. Frichova Grono, p. 10.

70

L. Isakhanyan, ‘EUMM - Georgia : the European Union monitoring mission’, Diploweb.com: La Revue Géopolitique,

71

1. No recourse to use violence between the protagonists. 2. The final cessation of all hostilities.

3. Ensuring unhindered access to humanitarian aid.

4. A return of the Georgian military forces to their original position.

5. A withdrawal of the Russian armed forces to the lines behind which they were before the fighting began. Russian peacekeepers should take additional security measures until international mechanisms are agreed.

6. The start of international discussions on arrangements for security and stability in South Ossetia and Abkhazia. 72

The problems that Sarkozy’s ceasefire plan presented lay in its interpretation. As there was no time frame defined, the hostilities, especially at the South Ossetian border, continued even after the agreement was signed. Multiple reports question the actual willingness to comply with it in general. Another issue is that there is no passage on the sovereignty and territorial integrity of 73

Georgia. This would have hindered or led to a failure of the peace negotiations because the territory of Georgia is defined differently by the conflicting parties and its supporters. While Russia recognizes the sovereignty of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, the EU regards them as an integrated part of Georgia. The compliance by all parties with the plan is monitored by the 74

EUMM in Georgia, which was dispatched to the Southern Caucasus for this reason, and following the model of the European Community Monitor Mission in the former Yugoslavia, as well as through the work of a special representative. 75

6.

Incentives for International Involvement

The involvement and standpoints of various international actors in the conflict have different politically and economically motivated reasons. They represent a crucial aspect of understanding how and why they pursue a possible resolution. Furthermore, the involvement of external actors in Georgia can be explained by the pursuit of benefitting or even saturating their economic and

‘Press Release General Affairs and External Relations, Council of the European Union, Brussels, 13.08.2008, C08/236, available

72

at https://eumm.eu/data/file_db/factsheets/.PRES-08-236_EN%20(1).pdf, (15.05.2020).

L. Harding and J. Meikle, ‘Georgian villages burned and looted as Russian tanks advance’, The Guardian, 13.08.2008, https://

73

www.theguardian.com/world/2008/aug/13/georgia.russia6, (11.05.2020). M. Dobrescu and T. Schumacher, The Politics of Flexibility, p. 414.

74

L. Isakhanyan, ‘EUMM - Georgia’, p. 8.

political deficits. For Russia, the Southern Caucasus region is considered a ‘near abroad region’, 76

in which it claims interests of security policy. It supported the secessionists in South Ossetia and Abkhazia financially and militarily, as well as provided free medical care and education for South Ossetians from an early stage. However, formal recognition as independent states was initially 77

avoided, as this would have been a reason for the ethnic minorities in the autonomous republics in Russia, especially the Northern Caucasus, such as Dagestan or Chechnya, to strengthen their secessionist movements. Pro-Russian minorities in other countries are backed by Russia, mainly 78

through the moral and political support of the local elites, direct financial aid, and economic investments. This gives Moscow the possibility to act outside of its borders from within that country, without using hard power, like military interventions. 79

During the Caucasus War in 2008, Russia became one of the conflicting actors. The approaches taken by Moscow highly tend towards an outcome that is in the best interest of Russia. As Abkhazia’s goal is to achieve the recognized independence that it formerly had, and South Ossetia is not opposed to an integration with Russia, this means that both oppose Georgia, and their aspirations overlap. Apart from the Russian incentive of having influence from within another 80

state, the Southern Caucasus’ strategic position is important to all big international actors around it. It represents the land-gateway between Russia to the north, Iran to the south, and the EU via Turkey to the east. In Russia’s case, it is mostly the transit of natural resources from and to its trading partners in Iran and the Middle East, which makes the north-south connection via Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan so vital. The EU, on the other hand, seeks to reduce its dependency on Russia, to be at eye level in global power. 81

Countries like the Baltic states, Finland, Poland, and the Czech Republic, still consider Russia as a threat to European security and, therefore, back measures aimed to reduce its power in countries like Georgia or Ukraine. While inner state security is indeed important, the policy field of energy 82

F. Schimmelfenning and U. Sedelmeier, Palgrave Advances, p. 99.

76

I. Mnatsakanyan, ‘The Quest for Coherence in EU Crisis Management in the South Caucasus’, p. 100.

77

D. Sokolov, ‘Will the war in Russia’s North Caucasus ever end?’, Open Democracy, 28.08.2018, https://

78

www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/will-the-war-in-russias-north-caucasus-ever-end/, (12.05.2020). E. Suleimanov, Understanding Ethnopolitical Conflict, p. 116.

79

M. Dobrescu and T. Schumacher, The Politics of Flexibility, p. 414.

80

I. Mnatsakanyan, p. 88.

81

M. Frichova Grono, ‘Georgia’s Conflicts: What Role for the EU as Mediator?’, p. 16.

security is arguably the most potent instrument to maintain economic power and political stability within any international actor. As Russia supplied almost a quarter of the European gas demand 83

in 2010, the strategic and geographic position of the Southern Caucasus presents alternative routes for gas delivery from Azerbaijan or Turkmenistan. The ‘Trans-Anatolian Pipeline’ through 84

Turkey has received financial support from the European Bank for Reconstruction (EBRD) and Development. The planned ‘Nabucco Pipeline’, which was intended to connect the EU with the Caspian gas reserves and thus open up new sources for Europe, also received extensive support from the EBRD and European Investment Bank, but has since been abandoned among other things due to the resulting leverage instrument of EU-accession of Turkey, and the proximity to the conflict areas in the Southern Caucasus. 85

However, the strategic importance of the Southern Caucasus for Russia in the economic sector is not considered vital anymore, as the natural resources within the country itself and befriended countries like Kazakhstan or Turkmenistan are more than abundant. Adomeit argues, that the main incentive for Russian involvement in the Abkhaz and South Ossetian conflicts are “more subjective considerations such as nostalgia for lost imperial greatness, (…) unwillingness to accept small countries as equals, and, above all, prevention of other international actors, notably the United States and NATO but also the EU, from filling a power vacuum”. On the other hand, the 86

EU’s incentives are impacted by values, like the adaption of political systems in the neighborhood to democracy, a neoliberal market economy, and stability, or the respect for human rights and the rule of law, reflect in parts of the ENP itself. In the case of the EaP, the EU uses “sanctions and 87

rewards”, to Europeanize and achieve its goals. 88

South Ossetia and Abkhazia have been de facto independent since their declaration in the early 1990s, even though no sovereign state in the world recognized this until 2008. After the Caucasus

B. Weber, ‘The effectiveness of the ENP (...)’, p. 16.

83

O. Geden, ‘Versorgungssicherheit - auch ohne neue Gasleitungen’, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 03.08.2010, https://

84

www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/fremde-federn-oliver-geden-versorgungssicherheit-auch-ohne-neue-gasleitungen-11026317.html, (12.05.2020).

‘Nabucco gas pipeline’, Bankwatch Network, 23.04.2012, https://bankwatch.org/project/nabucco-gas-pipeline, (12.05.2020).

85

H. Adomeit, ‘Russia and its Near Neighbourhood: Competition and Conflict with the EU’, Natolin Research Papers, College of

86

Europe Natolin Campus, Warsaw, 2011, p. 56.

E. Johansson-Nogués, ‘Perception of the European Neighbourhood Policy and of its Values and Norms Promotion’, in T.

87

Schumacher et al. (ed.), The Routledge Handbook, p. 435.

F. Schimmelfenning and U. Sedelmeier, Palgrave Advances, p. 99.

War that year, Russia proclaimed that it recognized the independence of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, as the first member state of the United Nations to establish diplomatic relations with the two areas officially. Moscow also called on other countries to follow the example. While copious support of the international community acknowledged Georgia’s non-recognition policy, various actors did, in fact, recognize the republics as independent. 89

On the one side, they consist of other non-recognized republics in the ‘Commonwealth of Unrecognized States’, such as Transnistria, Nagorno-Karabakh in a mutual approach, but also Western Sahara, and the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. On the other side, the UN member 90

states that followed Russia’s call have done so to get political and economic support. Nauru, a nation with practically no natural resources, had received a large credit by Russia in return for the recognition of Abkhazia. Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Syria, all have strengthened their relations with Russia, and have received financial support, as well. In the end, the involved international 91

actors use the disputes about Abkhazia and South Ossetia as a proxy to pursue their interests, both within the region and on a global level.

7.

Policy Analysis

The approach to the conflict taken by the EU is, arguably, an exception. As the EU is in itself, relying on cooperation and good multilateral relations between its member states, it uses rather constructivist methods to replace or influence the predominance of realism in the general international context. In the case of the bilateral relations with Georgia, the EU has introduced extensive and wide-ranging instruments, adapting to the nature and requirements of this relation. On the one hand, they aim to resolve the conflict with Abkhazia and South Ossetia, on the other hand, towards closer multi-sectoral collaboration, a transition to market economy, and finding political common ground. To achieve the latter, the first objective is, in return, a premise. The Georgian-EU relations are based on the ENP and its eastern dimension, the EaP. While the ENP 92

P. Gaprindashvili, ‘One step closer - Georgia, EU-integration, and the settlement of the frozen conflicts?’, Grass Reformanda,

89

Tbilisi, 2019, p. 6.

G. Lomsadze, ‘Semi-Recognized Western Sahara to Recognize South Ossetia’, Eurasianet, 29.10.2010, https://eurasianet.org/

90

semi-recognized-western-sahara-to-recognize-south-ossetia, (12.05.2020).

M. Robinson, ‘Pacific island recognises Georgian rebel region’, Reuters, 15.12.2009, https://in.reuters.com/article/

91

idINIndia-44730620091215, (12.05.2020).

‘Georgia’, European Neighbourhood Policy And Enlargement Negotiations, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/

92

was initially conceptualized for the newly accessed eastern neighbors that would border the EU after its fifth enlargement in 2004, the involvement in the Southern Caucasus increased over the years, to promote stability and support democracy. As a result, the ENP was regarded as the best mechanism to achieve this. 93

After the 2008 war and the importance of the EU’s newly gained access to the region, an instrument specifically designed to no longer look at post-Soviet countries in geographical Europe as Russia’s range of duty, but to create the necessary conditions for accelerating political association and further integration between the EU and these countries, was shaped: The EaP. It relies on shared values, like democracy, the rule of law, respect for human rights, as well as the collective work towards preventing and resolving conflict scenarios. Even though it is crucial to 94

stress that the ENP and the EaP are part of the EU’s overall foreign policy and separate from its enlargement policy, the relations with Georgia have continuously improved. In the following chapters, the EU approach to conflict resolution will serve as a comparative base for the analysis of the earlier mentioned cases, meaning the most representative conflict-altering instruments used by the EU in the case of Georgia, and that are covered by the former. While it is, in some cases, possible to link a case clearly to an EU policy, others are more cross-cutting and impact more than one policy.

7.1. The EU approach to Conflict Resolution

The policies used by the EU in Georgia have to be connected with the options that the EU has for approaching a conflict resolution. Coppieters presents four different possible policies: Conflict prevention, conflict transformation, international conflict management, and conflict settlement. 95

After each explained policy, the premises for achieving ‘Effectiveness’ are listed.

The most efficient way to deal with conflicts is not to allow them to arise. Even though the conflict in Georgia has been long ongoing, the aspect of preventing further conflicts remains an essential objective in mediating between the opposing parties and building peace. Conflict prevention

L. Simão, ‘The European Neighbourhood Policy and the South Caucasus’, in T. Schumacher et al. (ed.), The Routledge

93

Handbook, p. 312.

A. Maglakelidze, ‘Territorial Conflicts in EaP Countries and EU Security and Defense Policy’, United Europe, 2011, p. 28.

94

B. Coppieters, ‘The EU and Georgia: Time Perspectives in Conflict Resolution’, p. 3.

means that even though they have different standpoints, they should not allow for active violence to occur. This includes leading dialogs, the usage of reason and proportionality, and, most importantly, the waiver of active aggression. In case the conflicting parties are unable or unwilling to conduct such dialogs, or even provoke a conflict, it is in the responsibility of a third-party mediator, to restrain such actions that are considered to trigger aggression. This falls into the 96

assignment of the EU’s measures, among others, the EUMM.

An example of this type of provocation is the blockage of infrastructural elements as leverage, like the water supply to and from South Ossetia, which has constantly been subject to manipulation. In 2009, South Ossetians cut off the water supply to villages in the Tskhinvali region, primarily populated by ethnic Georgians. The secessionists also closed the Vanatsky water pipeline and the reservoir that supplies 17 villages in the Gori district and then started demanding that Georgia should pay for the water, supplied through the pipeline. Actions like this have to be prevented. 97

Therefore, the EU’s conflict prevention policies are rated effective when the used instruments have prevented the escalation of open violence and active aggression, and contributed to establishing stability in the region.

Conflict transformation is the approach that is being taken when a conflict is already ongoing. As the conflict in Georgia is centrally based on differences of identity and interests, the most crucial step is to get the conflicting parties and their interests to come closer together, assuming that they cannot find compromises on their own. The interventions taken by the EU have to have a 98

positive transformative effect, in the sense that the communication with Georgia, as well as with Abkhazia and South Ossetia, has to take place on an equal level, and that the assimilation or at least the acceptance of each other can grow. It is one step before conflict resolution, where the 99

parties need to address prospects and requirements for taking this step. Therefore, the EU’s conflict transformation policies are rated effective when the conflicting parties and their interests have been brought closer together by the EU’s intervening efforts.

B. Coppieters, ‘The EU and Georgia: Time Perspectives in Conflict Resolution’, p. 13.

96

‘South Ossetia Blocked Water Supply to Two Georgian Provinces’, World Water News, 15.07.2009, https://www.ooskanews.com/

97 story/2009/07/south-ossetia-blocked-water-supply-two-georgian-provinces_132615, (12.05.2020). B. Coppieters, p. 17. 98 B. Coppieters, p. 18. 99

However, the mediation between them on an equal level would imply the equal treatment, ergo equal recognition of the de-facto governments. This is not doable for the EU, as first and foremost, their support as an external actor holds with the Georgian government. While the EU has taken humanitarian and economic measures to support the reconstruction and rehabilitation of the minorities’ population after the war, Georgia has continuously encouraged the EU not to do so. As a result, the EU has adopted the ‘Non-Recognition and Engagement Policy towards Abkhazia and South Ossetia’ (NREP) in 2009, which actively focuses on de-isolation and transformation, in a sense, that the inter-state relations, as well as the relations between the international actors, are to be ameliorated. The EU is indeed trying to convince Georgia to take measures to present itself 100

more attractive to the breakaway communities and to encourage them to remain within Georgia, but, as mentioned above, a conflict that originates from identarian differences is challenging to transform through economic incentives. 101

If, in any case, the taken efforts backfire, and the conflicting parties drift further apart, the external international actors have to step in and contain a possible escalation by “exercising leverage on the parties or by changing the balance of power between them”. These actions of international 102

conflict management are strongly related to the incentives for involvement and taken under the assumption that they will benefit both parties. The contradictory problem is that even though the EU equally recognizes the rights, concerns, and legitimate interests of all relevant parties and communities, it also unconditionally supports the “sovereignty, territorial integrity and inviolability of the internationally recognized borders of Georgia”. This implies that, while the 103

EU can create incentives for Georgia to de-escalate tensions with Abkhazia and South Ossetia, for example through visa liberation of Georgian citizens or closer international cooperation, the attitude in the Abkhazian capital Sukhumi, and Tskhinvali towards the EU, thus the willingness to cooperate, has suffered and declined due to the firm support for the territorial integrity of Georgia. 104

S. Fischer, ‘The EU’s Non-Recognition and Engagement Policy towards Abkhazia and South Ossetia’, European Union Institute

100

for Security Studies, Brussels, 01.12.2010, p. 1.

B. Coppieters, ‘The EU and Georgia: Time Perspectives in Conflict Resolution’, p. 19.

101

B. Coppieters, p. 4.

102

‘European Parliament resolution of 20 May 2010 on the need for an EU strategy for the South Caucasus (2009/2216(INI))’,

103

Official Journal of the European Union, 31.05.2011, C 161/140. M. Dobrescu and T. Schumacher, The Politics of Flexibility, p. 414.