English (61-90), 30 credits

The language of non-commercial advertising:

A pragmatic approach

C-essay English Linguistics, 15 credits

Halmstad, 2020-06-04

Anna Rath Foley

The language of non-commercial advertising: A pragmatic approach

Anna Rath Foley

School of Education, Humanities and Social Science, Halmstad University

Bachelor Thesis in Linguistics (15 hp), English 61-90 2020-06-04

Supervisor: Monica Karlsson, Associate Professor Examiner: Stuart Foster, Ph.D.

ABSTRACT

The current study has explored the language of 30 non-commercial advertisements, both quantitatively and qualitatively, within the framework of pragmatics. The main incentive was to conduct an investigation into how the advertiser working with such a philanthropic genre employs attention-seeking, informing and persuading functions when she communicates with her audience. Orbiting around key notions of Relevance Theory (1986; 1995; 2012) and Tanaka’s pragmatic approach to advertising (2005), the study attempted to determine whether non-commercial advertising differs from its commercial counterpart in terms of informing and persuading intentions, and to examine the extent to which non-commercial advertising relies on internal and external contexts in its explicit and implicit language. The findings show that non-commercial advertising utilises attention-seeking, informing and persuading functions in a variable fashion since they can be incorporated into complex arrangements in which they sometimes overlap or collaborate. This fuse appears to enable the advertiser to achieve her intended meaning at the same time as she can make efficient use of space and time. The study also found that there are non-commercial advertisements that completely lack persuasion. By excluding explicit and implicit imperative speech acts, conjunctive adjuncts and pronouns that involve the audience, such advertisements appear to be solely objective and informative. In turn, these findings suggest that the informing function in non-commercial advertising is not always subordinated to the persuading function, which contrasts with the informing-persuading hierarchy in commercial advertising. Finally, since the creator of non-commercial advertising frequently exposes her audience to weak relevance, she requires them to locate and solve explicatures and implicatures with help from both internal and external contexts, which strengthens Tanaka’s (2005) claim that advertisers treat their audience as potentially creative and resourceful once attention has been attracted and sustained. Keywords: Advertising; Attention-seeking function; Informing function; Non-commercial advertising; Persuading function; Pragmatics; Relevance Theory

CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION 1

1.1 Aims and structure 1

2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND 2

2.1 Communication from a pragmatic perspective 2

2.1.1 Relevance Theory 3

2.1.1.1 Enrichment 5

2.1.1.2 Reference assignment and allusion 6

2.1.1.3 Disambiguation and puns 7

2.2. Advertising as communication 8

2.2.1 Internal and external contexts in advertising 8

2.2.2 Non-commercial advertising and the informing-persuading hierarchy 9

2.2.3 Attention-seeking, informing and persuading functions 10

2.2.3.1 The imperative speech act 12

2.2.3.2 Reason and tickle 12

2.2.3.3 Metaphors 13

2.2.3.4 Slogans and hashtags 14

2.2.3.4 Shocking content 15

3. THE PRESENT STUDY 16

3.1 Research questions 16

3.2 Data 16

3.3 Method 17

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 18

4.1 Quantitative analysis of collected advertisements 18

4.2 Qualitative analysis of collected advertisements 23

5. CONCLUSION 27

REFERENCES 31

APPENDICES 34

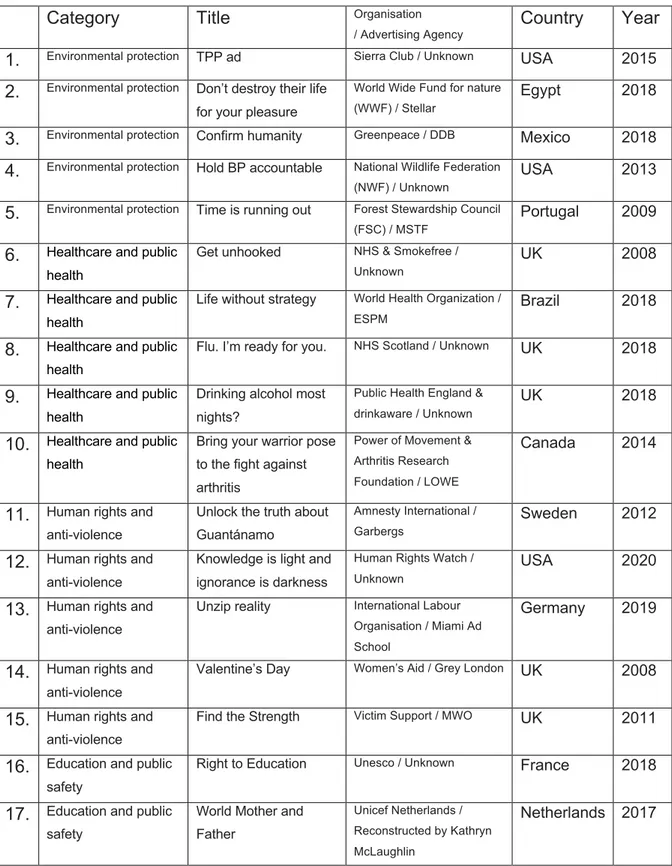

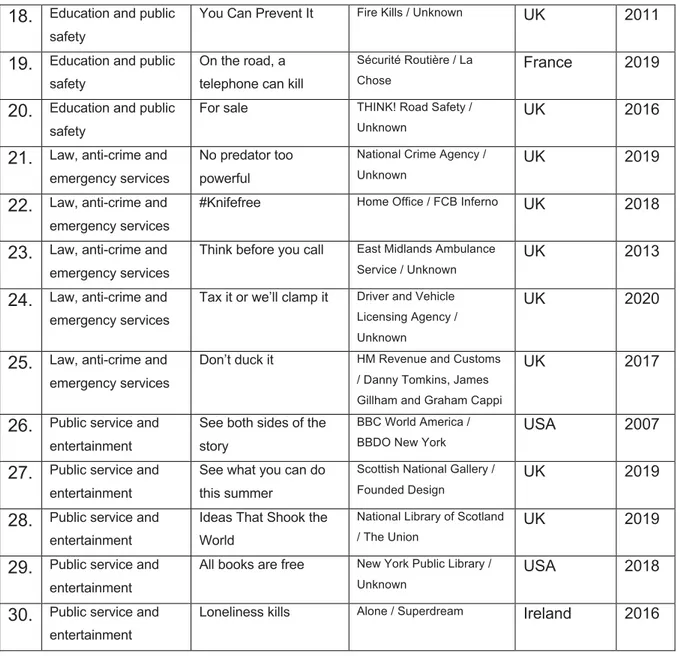

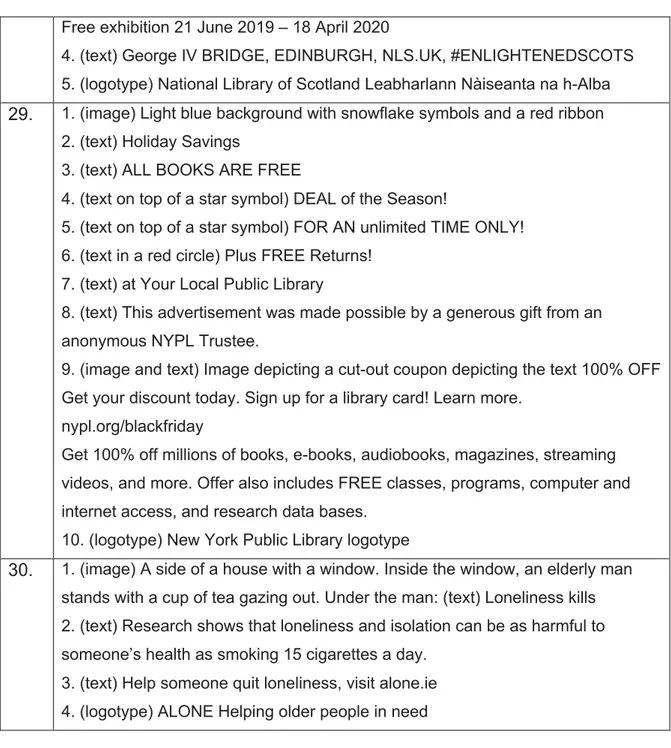

Appendix 1. Data background and content 34

Appendix 2. Textual analyses 41

1. INTRODUCTION

Having no tangible speaker to rely on for support, advertising as communication often finds itself in complex situations in the sense that modest advertisements risk being left unattended, whilst the bold and perplexing might be disliked or misunderstood altogether. Goddard (2002, p. 9) creates a simple but powerful description of advertisements when she calls them “attention-seeking devices”. Yet, considering that advertisers generally aim to persuade their audience into buying promoted products or services, they appear not only to seek attention, but co-operation as well. Some advertisements, however, are not designed to sell anything at all. Instead, they might serve to inform or educate their audience on, for instance, how to recycle, when to submit this year’s tax return or what measures to take during a health crisis. In order to discover whether such detachment to money-making purposes has any effect on advertising language, the current study conducts a pragmatic investigation into non-commercial advertising and its communication.

1.1 Aims and structure

The main incentive of this study is to examine how language is constructed in non-commercial advertising. The investigation aims to illustrate the extent to which 30 collected non-commercial advertisements employ attention-seeking, informing and persuading functions, and to examine whether this extent complies with the hierarchy present in commercial advertising in which information is consistently subordinated to persuasion. Further, the study pays attention to the advertisements’ use of internal and external contexts in their explicit and implicit language, specifically in relation to the contained functions.

Following the introduction, the theoretical background (Section 2) engages in describing communication, both from a pragmatic perspective and in relation to advertising. Subsection 2.1 provides a brief account of Grice’s pragmatic position to language philosophy (1967; 1989) but focuses mainly on Wilson and Sperber’s Relevance Theory (1986; 1995; 2012) in which three interpretation processes are considered: enrichment, reference assignment and disambiguation. Subsection 2.2 aims to intertwine the introduced pragmatic notions with advertising, so that support necessary for the study can be established. Subsection 2.2 introduces the roles of commercial and non-commercial advertising respectively, alongside Tanaka’s (2005)

claim that there is a hierarchy between informing and persuading functions in advertising. In addition to the distinction between the two advertising genres, the subsection also alludes to terms relevant to the nature of advertising as a whole, namely its internal and external contexts and its attention-seeking, informing and

persuading functions, in which imperative speech acts, ‘reason’ and ‘tickle’, metaphors, slogans, hashtags, and shocking content are considered. After the

theoretical background, the current study (Section 3) is introduced, in which research questions addressed are defined alongside the data and methods by which these data were selected and analysed. Further, Section 4 presents and discusses the findings of the study, and the conclusion (Section 5) works to sum up and evaluate the study and suggest future research.

2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

As stated in the introduction, the study seeks to examine the language of 30 non-commercial advertisements in order to explain (a) the extent to which their communication strategies are attention-seeking, informing and/or persuading, (b) to what extent they comply with the informing-persuading hierarchy and (c) how they make use of internal and external contexts in their explicit and implicit language. Since this study is formed by equal parts language and advertising, it relies on the following theoretical background which aims to give a sufficient account of communication, both in terms of pragmatics (Subsection 2.1) and in relation to advertising (Subsection 2.2). 2.1 Communication from a pragmatic perspective

Grice (1967; 1989) argues that non-pragmatic approaches to language philosophy are insufficient since they address language as a formal system and are therefore overlooking the importance of context and inference (Wilson & Sperber, 2012, p. 1). By creating a distinction between sentence meaning and speaker’s meaning, Grice is able to show how linguistic meanings can convey not only of what is said, but also what is implicated (ibid). For example, in ‘Ben is kind, but he pushed Claire’, the conjunction ‘but’ supplies an implicated meaning that Ben’s push is contrastive to his general behaviour. According to Grice (1967), there are two types of implicature, namely the conventional implicature and the conversational implicature. The above example is a conventional implicature since it takes place where “certain grammatical

forms, such as conjunctions, are used, for instance but, yet, still and therefore [italics added]” (Foster, 2017, p. 66). A conversational implicature, on the other hand, is based on the assumption that human beings communicate according to unspoken rules; an idea which Grice coined the Cooperative Principle:

Make your contribution such as is required, at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or direction of the talk exchange in which you are engaged. (Grice, 1967/1989, p. 26-27)

Grice also introduced four conversational maxims as a guide as to how interlocutors normally produce and comprehend implicatures, namely the maxim of quantity (be as

informative as required), quality (do not say what you believe to be false), relation (be relevant) and manner (avoid obscurity and ambiguity) (Levinson, 1983, pp. 101-102).

A conversational implicature, then, takes place when a participant flouts or violates the maxims attached to the Cooperative Principle. For example, Claire’s ironic utterance ‘It is always enjoyable to be pushed into a ditch’ is, in terms of Grice’s implicatures, flouting the maxim of quality since she, truthfully, did not enjoy it at all.

However, Grice made the mistake of creating a formal system himself, and Wilson and Sperber (1981, p. 155) argue that his pragmatic position “needs considerable modification if any further progress is to be made”. For instance, Sperber and Wilson (1986) question Grice’s vagueness in the sense that he says very little about the hearer’s recognition of the distinction between ‘what is said’ and ‘what is implicated’. They have also reworked his formal approach and point to the fact that most of his maxims are unnecessary (Clark, 2013, p. 67). Instead, Sperber and Wilson (1986) argue that formal systems are sensitive and prohibiting since language can be ambiguous at times, and that any theory approaching utterance interpretation should do so more freely in order to provide sustainable claims.

2.1.1 Relevance Theory

Relevance Theory is an expansive framework addressing the understanding of communication from a pragmatic perspective, in which human interpretation processes are explained in terms of two central principles:

(1) Cognitive principle of Relevance (Sperber & Wilson, 1995, p. 260-66) Human cognition tends to be geared to the maximation of relevance. (2) Communicative Principle of Relevance (ibid, p. 266-72)

Every act of overt communication conveys a presumption of its own optimal relevance.

That is to say, Relevance Theory relies on the idea that the audience hold a natural presumption that linguistic and non-linguistic communication will be optimally relevant when expressed overtly. As a result, the audience will instinctively adhere to the search for optimal relevance, which can be described by the following

relevance-guided comprehension heuristic (Sperber, Cara & Girotto, 1995, p. 51):

(3) a. Follow a path of least effort in constructing an interpretation of the utterance (and in particular in resolving ambiguities and referential indeterminacies, in going beyond linguistic meaning, in supplying contextual assumptions, computing implicatures, etc.)

b. Stop when your expectations of relevance are satisfied.

Thus, successful communication depends on the fact that human beings are designed to look for “as many positive cognitive effects as possible for as little effort as possible” (Clark, 2013, p. 365), or the greatest benefit for the smallest cost. To simplify the explanation of the two principles and the relevance-guided comprehension heuristic, the following example is used:

(4) Claire: I have broken my wrist!

When ostensively addressed by Claire, Ben conducts a search for optimal relevance in which he arrives at an interpretation consistent with Claire’s intention depending on context. For example, Claire might have uttered (4) as a result of a fall, or as a reply to Ben’s question ‘Have you ever broken a bone in your body?’. In his search for optimal relevance, there are three types of cognitive effects which Ben might arrive at:

(5) a. Contextual implication

Where a new assumption […] interacts with existing assumptions to communicate new assumptions […].

b. Strengthening an existing assumption

When a new assumption […] provides stronger evidence for an existing assumption which is less strongly evidenced, then the new assumption strengthens the existing assumption.

c. Contradicting an existing assumption

When a new assumption provides stronger evidence against an existing assumption, it may lead to the elimination of the existing assumption. (ibid, p. 364)

With regard to (5a), stimulus (4) establishes the new assumption that Claire has broken her wrist, which interacts with Ben’s existing assumptions and leads him to conclude suitable contextual implications. In terms of (5b), Ben might have seen Claire’s fall, which leads him to possess an existing assumption (although he might not be sure) that she hurt herself. Claire’s utterance (4) then establishes a new assumption which strengthens Ben’s assumption. In terms of (5c), Ben might instead have believed that Claire’s fall was trivial. Claire’s utterance (4) then establishes a new assumption that contradicts and eliminates Ben’s existing assumption.

While searching for optimal relevance in communication, the audience will encounter both explicatures and implicatures. Explicatures are, according to Sperber and Wilson (1995), conclusions derivable from the actual stimulus, whilst implicatures are all other propositions that make up speaker’s meaning. In order to sufficiently describe explicatures and implicatures and their role, the three following subsections aim to illustrate how they operate, more specifically in the process of enrichment (e.g. adding stored information), reference assignment (e.g. locating pronouns and allusions) and disambiguation (e.g. when a word has more than one meaning).

2.1.1.1 Enrichment

Enrichment refers to the adding of stored information performed by the audience in

their effort to comply with the relevance-guided comprehension heuristic (Wilson & Sperber, 2012). That is to say, the audience may enrich a stimulus, such as an advertisement or an utterance, using their memory and encyclopaedic knowledge in order to make sense of what is explicitly and implicitly conveyed. For instance, Ben might enrich the explicatures in Claire’s communication (6) in the following manner:

(6) Claire (upset): I have broken my wrist!

(7) Explicatures: {It is Claire who says that} I have broken my wrist {from a fall that happened just now}

Ben’s enrichment (7) allows him to reveal hidden information relating to the actual stimulus (6), such as what, when and to whom something has happened. In addition, since (6) and (7) are, in fact, conveying the same information, whilst (7) is more explicit, points to communication as a varying phenomenon, i.e. that it contains a

Ben may also enrich the implicatures of (6), in which he again requires help from his memory and encyclopaedic knowledge. For example, Claire’s linguistic and non-linguistic communication, such as her utterance and tone of voice, provides Ben with a new contextual assumption (8), with which he interacts existing assumption (9), concludes (10), and arrives at intended implicature (11).

(8) Claire is upset and in pain since she has broken her wrist from a fall just now. (9) When you break a bone in your body, you need to go to hospital.

(10) I should take Claire to hospital.

(11) Claire’s implicature: I have broken my wrist [and I need help to go to a hospital]

Similar to that of varying explicitness, communication can involve a degree of

implicitness (Sperber & Wilson, 1995, p. 182). For instance, Ben might have derived

further implicatures from Claire’s communication, such as [Claire blames Ben for the fall]. Such implicatures might not be backed as firmly by the speaker, and thus points to the idea of weak implicatures.

2.1.1.2 Reference assignment and allusion

To fully interpret communication, the audience may have to enrich propositions such

who, what and when something is referring to. Sometimes, such propositions are

vague, which requires the audience to carry out reference assignment in order to arrive at a suitable interpretation. Consider Claire’s question ‘Are they getting married in Las

Vegas?’, for example. Here, ‘they’ may include an indefinite number of referents, and

Ben must locate the referent most accessible depending on context. Wilson (1992, p. 189) argues that “the choice between [referents] must […] depend on the accessibility of contexts capable of combining with one of them to yield adequate effects for no unjustifiable effort in a way the speaker could manifestly have foreseen”. If the context includes the fact that Claire and Ben’s two friends are emotionally involved with one another, for example, Claire has arguably foreseen that Ben would interpret ‘they’ as specifically referring to their friends, and she thus provides him with an accessibility that yields relevant cognitive effects for no unjustifiable effort despite her vagueness.

Further, ‘married’ and ‘Las Vegas’ function as absent secondary references which require enrichment if Ben wants to comprehend the true meaning of Claire’s question. Thus, Ben must go deeper in his interpretation since the utterance includes a range of indirect or implicated references, i.e. allusions. Allusion relies on the

imaginary efforts of the audience and is, therefore, a term often found in the sphere of literature and poetry (Ben-Porat, 1976). However, allusion has been argued to be a more widespread phenomenon that is not only used in literature but in general language as well (Coombs, 1984; Lennon, 2011). In terms of Relevance Theory, allusions are indirect referential terms that require extra processing efforts in return for a wider range of cognitive effects. For example, in his interpretation of Claire’s question ‘Are they getting married in Las Vegas?’, Ben must access his encyclopaedic knowledge and connect the idea of ‘marriage’ with the existing idea of ‘a legally

accepted relationship between two people’ alongside the idea of ‘Las Vegas’ as a ‘US city known for its entertainment, casinos and quick and cheap wedding services’. If

Ben possesses sufficient knowledge about the allusions, he will not only be provided with cognitive effects as to Claire’s intention that she wants to know whether their friends are getting married, but also to the implicature that she finds it tasteless that they will do so by having a quick and cheap wedding service.

Allusion can also possess an echoic nature, in which it functions similarly to the pun since it refers to an absent secondary reference that is lexically and/or phonologically ambiguous (Lennon, 2011, p. 80). However, all allusions must not be ambiguous in order to work sufficiently, as the above example between Claire and Ben demonstrates. Therefore, for the sake of simplification, all that follows will class non-echoic secondary references as allusions and non-echoic secondary references as puns. 2.1.1.3 Disambiguation and puns

When a word has more than one meaning, it is called a homonym. One such example is ‘robot’, which can refer to both ‘a machine controlled by a computer’ and ‘a person

who lacks emotions’. If a homonym is used to provide a possible double meaning,

often with a humorous purpose, it can be categorised as a pun. In addition, punning can be established by the use of homophones, i.e. where several words sound the same, for example, ‘allowed’ and ‘aloud’.

Puns are, in other words, playing on the ambiguity of language and are, in terms of Relevance Theory, invented by the speaker who intentionally triggers two or more interpretations (Tanaka, 2005, p. 62). When encountering such ambiguity in their search for optimal relevance, the audience locate and disambiguate puns in which they generally reject the first (most accessible) interpretation whilst continuing to search for a more acceptable interpretation (ibid). The extra processing effort required

to solve ambiguous elements such as puns actually appears to award the audience with extra contextual effects “based on the pleasure and satisfaction of having solved the pun” (ibid, p. 82) and the pun might, therefore, be a successful device in terms of both sustaining the attention of the audience and improving their lacking co-operation. 2.2 Advertising as communication

Despite being a subject considered by a wide array of disciplines, the majority of studies into both commercial and non-commercial advertising lack essential linguistic groundwork. In addition, many of the studies into advertising that actually consider a purely linguistic approach appear to favour semiotics, such as Barthes (1984), Williamson (1983) and Bignell (2002). However, Foster (2017) and Tanaka (2005) argue that some contextual features in advertising are, in fact, unexplainable by semiotic principles. Considering the fact that the advertiser’s awareness of context is “heavily and intuitively applied in the construction of advertising texts” (Foster, 2017, pp. 239-40) and that “the understanding of advertisements is not merely a matter of decoding” (Tanaka, 2005, p. 12), it may be argued that a semiotic approach to advertising language is insufficient. Relying on a construction built by signs and their signifiers, semiotics may describe advertising language and how it functions, but it does not suffice in resolving dilemmas in which some signs are vague, ambiguous or overlapping. In addition, semiotics does not amply define the meanings sometimes weakly implied by the advertiser. Instead, pragmatics in general – and Relevance Theory in particular – can be seen as the most suitable framework in relation to the understanding of advertising language since it does not only pay attention to what is explicitly stated, but what is implied. In considering the impact of context, a Relevance-based approach is further freed from the restrictions of the sets of rules attached to semiotic approaches.

2.2.1 Internal and external contexts in advertising

In advertising, there is a distinction between internal and external contexts (Dybko, 2012), where internal context refers to the environment of the advertisement and its elements, such as images, text, slogans etc. External context, on the other hand, refers to all elements in the world outside the advertisement. These elements are generally dependent on general and cultural knowledge relating to norm-based expectations amongst the public, such as the expectations that, say, a minute is the

equivalent of 60 seconds and that cars cannot run on air. Needless to say, the internal context plays a crucial part in advertising in the sense that the advertisement’s existence depends on it. External contexts, on the other hand, have a more complex role since they can make significant impacts on the audience’s interpretation of the internal context. One such example is how Tesco’s slogan ‘Every little helps’ shifted linguistic meaning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, the slogan embodied the meaning ‘every small price reduction will help our customers

economically’. During the pandemic, however, the slogan made use of the audience’s

knowledge of the country’s situation in order to convey the meaning ‘every small

measure you as a customer take to maintain social distancing will help stop the virus from spreading’ (Tesco, 2020). This shift demonstrates how ambiguous propositions

can benefit from new, or multiple, internal and external contexts whilst maintaining the same lexical structure. In other words, Tesco created a new stimulus in which they succeeded in reaching their intended meaning without altering their original slogan. Thus, when interpreting an advertisement, the audience derive knowledge from both internal and external contexts, with which they solve explicatures and implicatures in order to arrive at conclusions suitable for the overall context.

To consider how the audience interpret explicatures and implicatures using internal and external contexts is particularly important in the sense that it helps to demonstrate advertising’s ability to communicate with an audience despite not having a physical speaker at hand to rely upon. In fact, Tanaka (2005, p. 106) argues that the audience manage to solve complicated problems inside the advertisement, such as puns and metaphors, with the assistance from their “encyclopaedic knowledge, extension of context, and considerable imaginative effort”, which points to the relationship between internal and external contexts as vital for the understanding of advertising language.

2.2.2 Non-commercial advertising and the informing-persuading hierarchy Unlike commercial advertising, non-commercial advertising does not orbit around the idea of financial gain. Instead, the genre, which sometimes goes under the names

social advertising (Dybko, 2012) and non-product advertising (Cook, 1992), might be

best known for its attempts to inform its audience and persuade them into establishing and maintaining healthy behaviours (Rice & Atkin, 2001, p. 56-7).

From a sociological perspective, commercial and non-commercial advertising differ in the sense that non-commercial advertising is more likely to address, for example, the ethics of its audience. What follows is, however, not a sociological study but a linguistic one, and it would therefore be problematic to divide the two genres based on their opposing use of, say, emotions, ethics or empathy. In fact, it appears that commercial and non-commercial advertisements can work on similar grounds since a commercial advertisement can be fully capable of addressing the ethics of the audience by selling, for instance, vegan and cruelty free products.

In terms of linguistics, however, there is still one idea that appears relevant in the separation of the two genres. With support from Packard (1981) and Pearson and Turner (1966), Tanaka (2005, p. 36) argues that there is a hierarchy amongst informing and persuading functions in advertising. In her brief but important claim, Tanaka illustrates that these two functions are of unequal importance since information is subordinated to persuasion. That is to say, commercial advertisements appear to rely on the informing function exclusively in relation to the persuading function since their main goal, i.e. to sell products, would go unfulfilled without the persuading function. This is obviously not the case for non-commercial advertising, which Tanaka acknowledges, since the improvement of an addressee’s knowledge of the world can, indeed, be the only incentive for such an advertisement. Thus, to fully understand the relationship between commercial and non-commercial advertising, and to fully understand the linguistics of non-commercial advertising, it is relevant to explore whether detachment to money-making purposes can have any effect on the extent to which it employs these two language functions.

2.2.3 Attention-seeking, informing and persuading functions

The central goal of any type of advertising is to attract and sustain the attention of the audience in order to provide them with information and/or persuade them into acting according to the intention of the advertisement. In other words, once attention has been attracted and maintained, advertising language appears to consist of two main functions, namely the informing function and the persuading function (Crystal & Davy, 1983, p. 222). In contrast to the informing function, which appears to work in stillness in the sense that it improves the audience’s knowledge of the world without any incentives, the persuading function aims to actively cause the audience to comply with the embedded intention. Whilst non-commercial advertising does not strive to sell

anything, it nevertheless embodies a social situation very different to everyday conversations since its communication exchange takes a less direct form, and it may therefore still act persuasively. Similar to its commercial counterpart, which forms a complex relationship between the advertiser and the audience in which there is a lack of attention, social co-operation and trust from the audience’s side (Tanaka, 2005, p. 59), non-commercial advertising notably requires help in communicating with its audience. In aiding this dilemma, the advertiser uses methods in which she employs attention-seeking, informing and persuading functions so that she can gain the attention, co-operation and trust of her audience. The distinctions between these three functions are not always clear cut, and some functions may overlap in the sense that a device may, or may not, fulfil the role of being attention-seeking, informing and/or persuading simultaneously. For example, a pun might not only attract and sustain the attention of the audience but may also build trust through humour.

Attention-seeking functions work to ostensively attract, secure and maintain the attention of an audience. Common elements are, inter alia, puns and metaphors, which appear to “frustrate initial expectations of relevance and create a sense of surprise” (ibid, p. 68). In addition, they help in sustaining the audience’s attention for a longer period of time since they require extra processing efforts in order to be solved, something which also results in the advertisement becoming more memorable (ibid, p. 82). Informing functions, on the other hand, work to introduce information relating to, inter alia, the orientation, products, services and values of the advertised organisation. In terms of Relevance Theory and based on the assumption that the advertiser’s request for attention has been successful, the audience will search for optimal relevance in the advertisement’s language, images and graphological features. Informing elements work to assist in this search since they provide the audience with essential facts relating to the intended message. For example, the advertisement text ‘97% of climate papers stating a position on human-caused global

warming agree global warming is happening – and we are the cause’ (The Consensus

Project, 2013) states information without urging the audience to take action. Thus, the informing function in itself leaves the audience with an improved knowledge of the world but without incentives to take any form of action (Tanaka, 2005, p. 36). Many commercial and non-commercial advertisers will, however, not attempt to attract attention in order to merely inform. Instead, they might also aim to persuade their audience into complying with the intentions of the advertisement. This is the case with,

for example, Legambiente’s advertising text ‘Is your worrying global enough? Face the

problem before it’s too late’ (Legambiente, 2008), in which the verb ‘face’ functions as

an imperative speech act that urges the audience to act according to the advertisement’s intention.

2.2.3.1 The imperative speech act

Austin (1962) argues that speech acts are utterances equivalent to actions, i.e. where the speaker is achieving, or trying to achieve, something by her utterance. Advertisements urging us to action can be said to employ the imperative speech act (Myers, 1994, p. 47), which, in this case, operates as a persuasive function. In commercial advertising, the imperative speech act is designed to make the audience believe that they will benefit from complying, and such advertising often excludes what Myers (ibid, p. 48) calls politeness devices, such as imperatives in the interrogative form or the word please. For example, Nike’s slogan ‘Just Do it’ implies that co-operation would involve some type of personal gain for the audience, whilst ‘Could

You Please Just Do it?’ would imply that the advertiser would gain from the

compliance. However, the effect of politeness devices might differ slightly depending on the purpose of the message. For example, WWF’s imperative speech act ‘Don’t

destroy their life for your pleasure’ (Appendix 3, Number 2) could arguably take the

form ‘Please don’t destroy their life for your pleasure’ without losing its intention of being persuasive since the action would benefit ‘them’, i.e., the animals, and not the audience. However, to use politeness devices would, arguably, soften the tone of the urge and make it come across less serious than intended.

2.2.3.2 Reason and tickle

Simpson (2001) takes on a pragmatic approach to persuasion in advertising, in which he develops Bernstein’s (1974) claim that there is a binary distinction between reason

advertisements and tickle advertisements. Simpson (ibid, p. 594; 600) demonstrates

that reason advertisements offer logical and/or factual reasons as to why the audience should act according to the presented intention whilst tickle advertisements offer more ambiguous reasons often relating to mood, emotion, humour and desire. In reason advertising, Simpson (ibid, p. 599) argues that the advertiser makes use of “semantic connectivity which relies heavily on a specific and restricted set of conjunctive adjuncts” when attempting to persuade her audience. One example is how Pampers

employs the positive conditional adjunct ‘if’ in “If he’s wearing Pampers, he’s staying

dry [italics added]” (ibid, p. 596). In terms of Relevance Theory, Simpson (ibid) argues

that such reason advertising leaves nothing to the imagination and that it, as a result, offers the audience a satisfactory range of contextual [cognitive] effects for no unjustifiable processing effort.

Tickle advertising, on the other hand, displays what Simpson (ibid, p. 592) calls

oblique communication, which, in terms of Relevance Theory, refers to weak

relevance. Simpson (ibid, p. 600) argues that the audience, confronted by a propositional non-informativeness such as a tickle element, will attempt to access implicatures for the presented communication, and that such advertisements therefore open a number of possible speculative inferencing pathways. One example on a tickle element is how Legambiente’s advertising text ‘Is your worrying global enough? Face

the problem before it’s too late’ (Legambiente, 2008) addresses a sense of fear and

urge to hurry by utilising vague degrees, in which the audience might feel unsure about what is classed as ‘global enough’ and what is ‘too late’. Here, the audience are required to use extra processing efforts in order to solve the ambiguous elements and understand the purpose of the advertisement.

Simpson (ibid, p. 591) also argues that all advertising involves the reason-tickle continuum to some degree, in which “no advertisement can be all one or other”. Cook (1992, p. 10) offers a simple but effective example, in which he demonstrates that cigarette advertisements are predominantly tickle advertisements since there are few logical reasons for buying and smoking cigarettes.

2.2.3.3 Metaphors

A linguistic device often occurring in advertisements, which may fulfil several functions at once, is the metaphor. The essence of the metaphor lies within the search for an imaginary resemblance between otherwise unrelated objects, which is why it, similarly to that of allusion, is frequently misunderstood as an exclusively poetic device. However, Lakoff and Johnson (1980, p. 3) argue that metaphors are “pervasive in everyday life”, which is supported by Graesser, Long and Mio (1989), who have found that English speakers produce one metaphor for almost every 25 words they produce. For example, in the above example of Legambiente’s text ‘Is your worrying global

enough? Face the problem before it’s too late’ (Legambiente, 2008), both ‘global’ and

extra processing efforts. In addition, to expose the audience to such imaginary resemblances allows the advertiser to intertwine her search for attention with informing and persuading functions in the sense that ‘global’ also makes the audience derive further assumptions relating to the information conveyed, and ‘face’ works as a metaphor and imperative speech act simultaneously.

Important to underline is the fact that metaphors are organic since they may have unlimited possible implications. For example, if Claire says to Ben ‘This book is a

bible!’ when referring to a book that is not a bible, Ben might possess a number of

existing assumptions in relation to bibles, such as (12) and (13): (12) A bible is a large, heavy and difficult book.

(13) A bible is an important book involving guidance on how to live one’s life.

Thus, Claire’s metaphorical utterance may include several implications and the final conclusion depends on both context and Ben’s personal encyclopaedic knowledge. Theories based on strict systems and signs, such as Barthes (1984) and Williamson (1983), are therefore insufficient in providing a comprehensive description of metaphors (Tanaka, 2005, p. 5). Relevance Theory, on the other hand, offers a sufficient approach to the metaphor and its unlimited implications in which Wilson and Sperber (1988, p. 139) argue that there is no “discontinuity between metaphorical and non-metaphorical utterances”. Instead, the metaphor is approached with the more flexible perspective that every utterance is a “faithful representation of a thought” (ibid) and that the representation need not necessarily be identical to the thought but similar enough to allow the audience to arrive at a relevant conclusion.

2.2.3.4 Slogans and hashtags

Advertisements often appear to seek ways to convey their messages efficiently since they are under economical, spatial and temporal pressure. Ke and Wang (2013, p. 277) argue that slogans are commonly used to catch the audience’s attention and affect consumers’ thoughts. Further, Dass, Kumar, Kohli, and Sunil (2014) argue that slogans work as effective portrayals of the organisation they represent since they are comprised by a single word or a short phrase. In terms of Relevance Theory, slogans are inputs yielding numerous cognitive effects simultaneously with involving small processing efforts since they are “created in such a way to seem most relevant and worth processing among other inputs available” (Dybko, 2012, p. 40).

Hashtags are similar to slogans in the sense that they carry a concise message relevant to the communication (Scott, 2015). Their primary role is to function as vessels carrying metadata tags on networking websites such as Twitter, Instagram and Facebook, but Scott (ibid, p. 2) argues that hashtags have developed beyond this role since they now also “guide readers’ interpretations”. The information of a hashtag may “guide the hearer in the derivation of both explicitly and implicitly communicated meaning, and may also have stylistic consequences” (ibid, p. 1) and can, therefore, work sufficiently outside its original environment. In advertising, both hashtags and slogans can therefore, similar to puns and metaphors, work to both attract attention, inform and persuade, in which the advertiser signals that she considers the tagged word or phrase to be relevant and related to the content of the advertisement.

2.2.3.5 Shocking content

According to Dahl, Frankenberger and Manchanda (2003, p. 268), shocking content “deliberately, rather than inadvertently, startles and offends its audience by violating norms for social values and personal ideals". In terms of advertising, the use of shocking content can have a number of effects on the audience, in which it may significantly increase their attention-level alongside benefit the memory of the advertisement and have positive influences on the behaviour of the audience (ibid, p. 265). Since shocking content violates the norms of communication, it is likely that advertisements employing such strategies may offend, confuse or scare the audience. One example is how Conac’s anti-smoking advertisement depicts an image of a crying child being suffocated by a plastic bag juxtaposed with the caption ‘Smoking isn’t just

suicide. It’s murder’ (Conac, 2008). However, not all types of shocking content enforce

distressing, blameful or frightening meanings. Instead, some may work to challenge normative advertising strategies by being pleasantly surprising. One such example is how Android’s advertisement Friends Furever (Android, 2015) appears to awe its audience by conveying a sense of togetherness amongst animals rather than promoting the software company’s services or products. Regardless of the advertisement’s ambience, the audience will, in terms of Relevance Theory, search for optimal relevance when ostensively addressed. Thus, it is likely that they will attempt to interpret the conveyed meaning despite their emotional state and the extra processing efforts required to comprehend the norm-breaking stimulus.

3. THE PRESENT STUDY

3.1 Research questions addressed

The current study addresses three main research questions:

1. To what extent does non-commercial advertising use attention-seeking, informing and persuading functions?

2. To what extent does non-commercial advertising comply with the informing-persuading hierarchy present in commercial advertising?

3. How do non-commercial advertisements make use of explicit and implicit language along with internal and external contexts in relation to the attention-seeking, informing and persuading functions?

3.2 Data

A total number of 30 non-commercial advertisements were collected for the purpose of this study. Prior to the gathering of primary data, a list of six categories classifying common non-commercial sectors was created:

1. Environmental protection 2. Healthcare and public health 3. Human rights and anti-violence 4. Education and public safety

5. Law enforcement, anti-crime and emergency services 6. Public services and entertainment

These categories are, however, problematic in two aspects. Firstly, they may overlap at times. Secondly, an advertisement with, for instance, an educational message may not have been published by a purely educational organisation. These problems are nevertheless orbiting in the sphere of social science, and the exact role of the organisation matters less since this is a linguistic study. Thus, the selection process has relied on these categories in order to demonstrate a variety of sectors and to maintain a structure that is as reliable as possible. These categories have also simplified the selection process, in which a random approach was employed to obtain un-biased research. Five organisations were selected from each category based on the first results appearing on the search engine Google after applying e.g. ‘environmental organisation’. Where a list or article appeared, the organisations were

selected from top to bottom unless they were presented in alphabetical order. In the latter case, the selection was purely random.

The final selection of advertisements was based on the first image result that appeared on Google after applying the name of the organisation and ‘advertisement’ (as in ‘WWF advertisement’). Apart from relying on the six categories, the present study is based on the choice of exclusively selecting advertisements communicating a non-commercial purpose. If the first result was a commercial organisation or company, the next result was chosen. For a detailed list of the 30 advertisements and their background information and content, see Appendices 1 and 3.

3.3 Method

Addressing the first and second research question, the study takes on a quantitative approach in which the advertisements’ attention-seeking, informing and/or persuading functions are gathered in numbers (Appendix 2, Figure 2.1). Quantitative methods require a defined purpose to function sufficiently since numbers mean nothing without contextual ‘backing’ (Dörnyei, 2007, p. 32). In this study, numbers are crucial because they work to demonstrate (a) the extent to which non-commercial advertising use the considered functions and (b) where non-commercial advertising is located in comparison to commercial advertising in terms of the informing-persuading hierarchy. Whilst there is an array of elements used by advertisers to attract and maintain attention, this study considers how the attention-seeking function can be fulfilled by the use of metaphors, puns, slogans, hashtags and shocking content. In terms of informing functions, attention is paid to communication in a wider sense where explicit or implicit elements relating to the advertised organisation and its orientation, values, purposes and services are considered. In addressing the persuading function, the study considers whether the collected advertisements involve explicit or implicit imperative speech acts, ‘reason’-elements, and ‘tickle’-elements. These numbers are, then, assembled and compared in order to determine how the functions are used in relation to each other and to functions in commercial advertising. The study does, however, not include an analysis of commercial advertisements, and Tanaka’s (2005) pragmatic approach to advertising is therefore used to aid the comparison.

Secondly, a qualitative textual analysis of six advertisements is implemented in order to address the third research question (Appendix 2, Figure 2.2). The analysis considers the first advertisement from each category and aims to examine the overall

language of the advertisements in relation to their attention-seeking, informing and persuading functions. The qualitative analysis is divided into two parts, where Part 1 outlines explicit and implicit language alongside possible cognitive effects triggered by the stimulus. Three interpretation techniques are addressed: reference assignment, disambiguation and enrichment. In terms of cognitive effects, Part 1 considers possible contextual implications triggered by contextual assumptions retrieved from the internal context in interaction with possible existing assumptions derived from external contexts. In order to demonstrate how the audience may arrive at the intended meaning, the analysis presents the existing assumptions that appear necessary in order to interpret the meaning most likely intended by the advertiser. Further, Part 2 of the qualitative analysis examines how the collected advertisements make use of attention-seeking, informing and persuading functions in relation to internal and external contexts. This part discusses how each advertisement employs puns, metaphors, slogans, hashtags, shocking content, informing facts, imperative speech acts and Simpson’s reason-tickle continuum.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This section aims to present and discuss the results found by the study. Firstly, Subsection 4.1 discusses the findings from the quantitative analysis (Appendix 2, Figure 2.1) and, secondly, Subsection 4.2 deals with the results derived from the qualitative analysis (Appendix 2, Figure 2.2).

4.1 Quantitative analysis of collected advertisements

The study shows that 100% of the 30 collected advertisements employ both attention-seeking functions and informing functions to some extent, whilst 28 of them make use of the persuading function. However, the analysis makes it evident that the advertiser does not always incorporate language devices so that they only adhere to one single function. Instead, she frequently applies them in a complex fashion where they fulfil several functions at once. For example, advertisement number 11 (Appendix 3) makes use of the visual metaphor ‘the US flag resembling prison bars’ not only to attract and maintain attention, but to also embody an essential piece of information, i.e. that prisoners at Guantánamo are restricted specifically by the US. This way, the advertiser

is able to express her propositions economically whilst achieving the full range of intended contextual effects.

Amongst the 30 advertisements involving attention-seeking functions, 27 contain some kind of metaphoric language, 16 present some type of punning and 5 use hashtags. Further, 9 advertisements make use of a slogan and 4 involve some kind of shocking content (Chart 1). Further, the study shows that 22 advertisements make use of two or more attention-seeking functions simultaneously (Appendix 2, Figure 2.1). Since aforesaid devices require their audience to use extra processing efforts by supplying knowledge about the world, extension of context and/or imaginative efforts, these results point to non-commercial advertising as being challenging simultaneously with being signalled as relevant by the advertiser.

Chart 1. Types of attention-seeking functions in the collected advertisements

All 30 advertisements also make use of informing functions. However, whilst 20 of them communicate their information strongly explicitly, 10 use informing functions in a less direct manner (Chart 2). Instead of expressing their information directly, these 10 advertisements appear to rely on the audience recovering the intended information using additional interpretation techniques. For example, Greenpeace’s advertisement text ‘Confirm humanity – I’m not a robot’, which is juxtaposed with an image of a malnourished polar bear (Appendix 3, Number 3), would be hard to describe without enrichment from external contexts. The audience are thus expected to derive further information with help from their encyclopaedic knowledge about involved allusions, such as ‘robot’ and ‘malnourished animal’, in order to comprehend the intended informing function ‘Greenpeace says that you are inhumane if you do not care about

Chart 2. Number of advertisements displaying informing functions

The quantitative analysis also shows that 28 out of the 30 advertisements use persuading functions to some extent, where 24 explicitly state that their audience should comply with the intentions whilst four require extra processing efforts (Chart 3; Appendix 2, Figure 2.1). In addition, the study illustrates that there are, in fact, two advertisements that completely lack persuading elements. Instead, these cases orbit around merely attention-seeking and informing functions, which indicates that non-commercial advertising makes use of the informing-persuading hierarchy differently to commercial advertising; an argument which is discussed further in Subsection 4.2.

Amongst the 28 advertisements involving persuading functions, all exclude to openly describe the reason as to why the audience should comply with the presented intention. Instead, the advertiser attempts to convince her audience whilst trusting that they will unrestrictedly locate the incentive from the internal and external contexts of the advertisement’s explicatures and implicatures. Thus, the study establishes the suggestion that the audience may have to use extra efforts in their interpretation of all three types of functions. Exposure to stimuli that require imaginative efforts is, according to Tanaka (2005, p. 106), rewarding the audience in the sense that extra processing efforts result in extra cognitive effects. That is to say, the audience may feel satisfied from solving the advertiser’s puzzle and they may also experience a sense of teamwork for sharing a mutual understanding of something complicated. These results underline that the advertiser treats her audience as intelligent in the search for optimal relevance.

Chart 3. Number of advertisements displaying persuading functions

In terms of how the three functions operate in relation to one another, the attention-seeking function appears to work universally with all types of informing and persuading functions since every advertisement involves some kind of attention-seeking device. Further, no advertisement lacks information, but a small number of advertisements lack persuasion (Chart 4, Column 5 & 8). Whilst all the collected advertisements involve informing functions, the study shows that they may differ in nature in the sense that advertisements are more likely to communicate the informing functions strongly than weakly (Chart 4, Column 1 & 2). Similarly, the nature of the persuading functions’ communication emerges as strong in most cases (Chart 4, Column 3) since only four out of the 28 advertisements containing persuading functions convey these using weak language (Chart 4, Column 4). However, there is a distinction in terms of how frequently informing and persuading functions are communicated strongly versus weakly since the advertiser involves weak, or complex, language less frequently in her persuasion than in her information (Chart 4, Column 2 & 4). These results may signify that the advertiser is less willing to risk possible misinterpretations when attempting to persuade her audience than when trying to inform them.

Amongst the advertisements containing all three functions, it is uncommon, yet it happens, that they communicate strong information and weak persuasion at the same time (Chart 4, Column 6) or a simultaneous use of weak information and weak persuasion (Chart 4, Column 9). Instead, it is more common for an advertisement containing all three functions to carry a simultaneous use of strong information and strong persuasion (Chart 4, Column 7) or weak information and strong persuasion (Chart 4, Column 10). These results may further develop the above claim that the

advertiser is less willing to risk the audience misinterpreting her persuasion, since she does not only convey persuasion more clearly and straightforward, but she does so regardless of the nature of the informing functions.

Chart 4. Functions in relation to one another

Comparing the functions found in non-commercial advertising to commercial advertising, it appears that both genres employ them similarly in most cases. The exclusive number of advertisements containing some type of attention-seeking function indicate that the non-commercial advertiser, similar to the commercial advertiser (ibid, p. 82; 106), does not take it for granted that her audience possess a high level of attention and that she, thus, actively tries to attract their attention and sustain it for a longer time. Further, all the collected advertisements in this study show signs of informing functions, even when vaguely expressed. As a result, it appears that the non-commercial advertiser, similar to the commercial advertiser (ibid, p. 36), cannot fulfil her goal of communicating her meaning to the audience without informing them to some extent. Tanaka (ibid, p. 106) argues that the commercial advertiser treats her audience as potentially creative and resourceful once attention has been attracted and maintained. Since all 30 collected advertisements require some type of further interpretation with assistance from external contexts, might it be in order to solve an attention-seeking metaphor or a weakly relevant informing fact, the study shows another similarity between the two genres in the sense that the non-commercial advertiser, too, treats her audience as potentially creative and resourceful. However, in contrast to commercial advertising, whose primary goal is to persuade the audience

(ibid, p. 36), the current study shows that non-commercial can, in fact, lack persuading functions and there appears therefore to be a difference between the two genres, which will be discussed further in Subchapter 4.2.

4.2 Qualitative analysis of collected advertisements

When approaching non-commercial advertising qualitatively, it becomes evident that it frequently utilises weak relevance in which ambiguous content, allusions, explicatures and implicatures are employed. Part 1 of the qualitative analysis shows that such indirect communication appears for several reasons in the sense that the audience are required to use their encyclopaedic knowledge to both comprehend the overall language of the advertisement and to solve e.g. puns and metaphors. A particularly noticeable discovery is that advertisements involving allusion frequently use metaphoric language and punning simultaneously, sometimes co-operatively. For example, advertisement number 6 (Appendix 2, Figure 2.2, Analysis 2) presents an image depicting a man having a fishing hook pierced through his lip, alongside the text ‘get unhooked’. To fully understand the whole stimulus, which is an anti-smoking advertisement, the audience are required to not only accept ‘unhooked’ as a pun and reject its most accessible interpretation (14) for a more relevant interpretation (15), but to also reject the literalness of the image (16) and, instead, accept it as the base of a metaphor (17):

(14) ‘Unhook’ as antonym to ‘hook’, i.e. literal detachment from a hook.

(15) ‘Unhook’ as antonym to ‘hooked on drugs/cigarettes/etc’, i.e. metaphoric reference to detachment from addiction.

(16) Image: A man expressing pain/discomfort since he has a fishing hook through his lip.

(17) Image: A man expressing pain/discomfort since he is illustrating a resemblance between ‘cigarette addiction’ and ‘being attached to a fishing hook’

In other words, the metaphor is accepted with help from disambiguation and vice versa, in which the key tool is the allusion cigarettes. In this complex arrangement, the advertiser involves attention-seeking functions simultaneously with getting the intended information and persuasion across to her audience. This discovery works to strengthen Wilson and Sperber’s (2012, p. 98) argument that the language comprehension process is far too context-sensitive to rely on code-like terms. That is to say, all language devices, such as allusion, puns, and metaphors, are positioned in

a concoction that is more likely to be explainable by the central notions of Relevance Theory rather than by distinct theories of their own.

Part 1 also shows that knowledge retrieved from external contexts is required to solve reasons as to why the audience should comply with the advertisement. For example, advertisement number 1 (Appendix 3) excludes why the audience should ‘join the Sierra Club’. Instead, the audience are required to first explicitly enrich the text (18) with contextual assumptions derived from the lexical nature of the stimulus, such as (19), and their encyclopaedic knowledge, such as (20), to arrive at relevant explicatures (21):

(18) JOIN US AT SIERRACLUB.ORG/TPP

(19) It is likely that they are talking to me rather than to somebody else. It is also likely that they want me to join them now or sometime soon rather than later.

(20) The advertisement contains a sentence followed by ‘.org’ and a forward slash, which refers to an organisational website.

(21) {You should} JOIN US {now or sometime soon} AT {our website} SIERRACLUB.ORG/TPP

In turn, the audience may comprehend intended implicatures by enriching the stimulus further. For example, in (22), the Sierra Club does not describe what ‘fracking’ is or how/where/why it would leave a mess. Instead, the advertiser makes use of a pun with two communicated meanings (‘fracking’, i.e. information, and ‘fucking’, i.e. emphasis). Here, she expects her audience to be knowledgeable enough to understand the pun and the allusion ‘fracking’ as being (23) and (24), with which they will conclude contextual implication (25) and make sense of implicature (26):

(22) THE TPP WOULD LEAVE A BIG. FRACKING. MESS

(23) Fracking threatens the climate since it can cause environmental damage. (An assumption strengthened by the emphasis of the pun)

(24) Environmental damage is unwelcomed in the sense that it has negative effects on the lives of people and animals.

(25) THE TPP WOULD LEAVE A BIG. FRACKING. MESS [and the Sierra Club implies that it needs to be stopped now to avoid the threat of unwelcomed environmental damage]

(26) JOIN US AT SIERRACLUB.ORG/TPP [in order to help stopping the TPP from causing environmental damage]

All six advertisements are shown to express some type of explicatures and implicatures. Commonly occurring explicatures appear to relate to space and time, as in ‘join us {now or sometime soon}’, and personal pronouns, as in ‘{You should} join us’. These findings may indicate that the advertiser considers that elements relating to spatial, temporal and personal references are easily accessible for the audience and that she, thus, can afford to communicate them weakly.

Implicatures, on the other hand, appear to be used in a broader sense. That is to say, they are embedded in anything from the information and persuasion of the advertisement to its involved metaphors, puns, hashtags, slogans and shocking content. In addition, commonly used implicatures appear to relate to the organisation itself since it seldomly is introduced with more than a logotype or a name. These results suggest that the creator of non-commercial advertising assumes her audience to have open access to their memory bank and general knowledge with which they will make sufficient and creative connections. In other words, the advertiser exposes her audience to complex elements regardless of not knowing whether they will have knowledge ample enough to fully comprehend them. She, thus, expects that her audience will make sense of intended meanings even if they have to guess. In turn, this expectation enables her to achieve her intended contextual effects whilst utilising language economically.

Part 2 of the qualitative analysis demonstrates that all six advertisements use devices in order to attract and sustain attention and, possibly more important, it also shows that non-commercial advertising can attract and maintain attention in order to merely inform its audience about a matter at hand. Advertisement number 16 (Appendix 2, Figure 2.2, Analysis 4) emerges as particularly prominent in the sense that it provides a large number of informing facts but no persuasion. Whilst it does provide a hashtag, which in some circumstances can urge the audience to search the internet, this advertisement arguably makes use of it as a guide of interpretation rather than an urge into action. This argument is established by the fact that there are no kinds of imperative speech acts, persuasive conjunctive adjuncts or tickle elements provided, neither explicitly nor implicitly. In fact, the advertisement appears to completely exclude the audience since it lacks personal pronouns that would normally anchor them to the text, such as ‘you’ or ‘us’. Instead, the only (weakly) occurring personal pronoun refers to the organisation, as in (27):

(27) {We (as in Unesco) say that the depicted child and all human beings have the} #RightToEducation

To lack persuasion as a result of not expressing personal pronouns may underline that persuading functions, in contrast to informing functions, depend on the personal involvement of an audience in order to operate sufficiently. By using attention-seeking devices, however, the advertiser still signals her informing stimulus to be relevant. Thus, to leave her audience without incentives to take any form of action seems to be a deliberate intention, which points to advertisement number 16 as clearly distinct in which the audience are not advised to do anything except acknowledging the facts presented. When comparing this result to even the vaguest of intentions in commercial advertisements, such as Benetton’s ‘Priest and nun’ (Benetton, 1991), it is evident that commercial advertising still involves tickle elements that operate persuasively, such as the exciting feeling of being in the know or to be a consumer that goes against

mainstream fashion by wearing clothes by controversial companies. It may, thus, be

suggested that one key to the distinction between the genres lies within the advertiser’s intention which notably affects her communication strategies. In other words, commercial and non-commercial advertising may differ linguistically since their creator intends them to fulfil different purposes. Non-commercial advertising is therefore, in contrast to commercial advertising, capable of violating the hierarchy in which information is subordinated to persuasion (Tanaka, 2005, p. 36).

Still, since the quantitative analysis (Subsection 4.1) has shown that the extent to which advertisements are exclusively informing is relatively small, it appears that non-commercial advertising still complies with the informing-persuading hierarchy in the majority of cases. In addition, since the advertiser is less willing to risk possible misinterpretations of the persuading function (Subsection 4.1), she most often appears to value persuasion higher than information.

Finally, the qualitative analysis indicates that all advertisements that involve persuading functions use imperative speech acts, even if they are stated weakly explicitly. For example, advertisement number 21 (Appendix 2, Figure 2.2, Analysis 5) provides a weak imperative speech act (28) which, in relation to parts of the advertisement text (29) and (30), and allusions such as ‘careers’ and ‘criminals’, results in the possible contextual implication (31):

(29) Catch the criminals that pose the biggest threat to the UK

(30) No predator too powerful {for us at the National Crime Agency}

(31) {Visit our website} nationalcrimeagency.gov.uk/careers [so you can be a more powerful person than the most powerful criminals in the UK]

In terms of Simpson’s reason-tickle continuum (2001), these persuading functions express reason elements in parallel to a propositional non-informativeness. That is to say, every persuasive advertisement in the qualitative analysis relies on the audience to unrestrictedly add conjunctive adjuncts and, thus, to enrich the reasons as to why they should comply with its intention. This suggests that the advertiser provides a non-informativeness upon which the advertisement’s persuasive intention relies. In terms of tickle advertising, pronouns such as ‘our’, ‘us’ and ‘you’ are found frequently, which appear to include the audience and address a sense of belonging in order to tickle them into complying with the intention. There are further emotional aspects attached to some advertisements, such as the sense of fear in advertisement 6 and the sense of power in advertisement 21 (Appendix 3).

5. CONCLUSION

In the present study, 30 non-commercial advertisements were examined with the intention to determine the extent to which they use attention-seeking, informing and/or persuading functions. Furthermore, the study has considered to what extent non-commercial advertising complies with the informing-persuading hierarchy that is consistently occurring in commercial advertising, and it has also paid attention to how non-commercial advertising makes use of explicit and implicit language, both in terms of internal and external contexts. A pragmatic approach was employed throughout the study since such a framework provides sufficient accounts on comprehension processes relevant to the understanding of advertising language.

The study concludes that the extent to which non-commercial advertising utilises attention-seeking, informing and/or persuading functions is variable since the three functions can be incorporated into complex arrangements in which they overlap at times. That is to say, the advertiser does not always use a language device for the purpose of adhering to one single function. Instead, she can make it serve as, say, attention-seeking and informing simultaneously, or even as a concurrent mixture of all three. These arrangements occur to benefit the advertiser in the sense that she