Discussion Paper

Governance Bottlenecks and Policy Options

for Sustainable Materials Management

August 2013

ENVIRONMENT AND ENERGY

United Nations Development Programme

Sustainable Materials Management

Transportation

Resource

Extraction ManufacturingProduction

Waste Use Final Disposal Landfill Tra nsp ort ation Recy cle R euse Reuse

Growing volumes and complexities of material flows pose serious risks to human health and ecosystems during different stages of the materials’ life-cycle. The gradual shift of base for manufacturing and chemical industries to developing countries has contributed to growth and employment but also lead to serious pollution of water, air and soil. Poor people tend to be most adversely affected by pollution and the health impacts from water and air pollution or dumping of hazardous waste is often dramatic. Managing mounting waste streams is cur-rently one of the biggest challenges for rapidly growing urban centers in develo-ping countries. Poor waste collection and dumdevelo-ping of waste in water bodies and uncontrolled dump sites is a major sanitation problem. Waste management is also an issue of global concern since the decay of organic material in post consu-mer solid waste contributes to about 5 percent of global greenhouse gas emis-sions. The growing flow of materials also includes a growing flow of chemicals in different products making waste streams more complex.

It is increasingly recognized that a technical focus on end-of-pipe solutions is not sufficient to address these problems. A shift towards more upstream approaches that can assure cleaner and more resource efficient materials flows is necessary. The traditional focus on technical solutions needs to be combined with strengthening institutions and governance systems since the way national and local authorities govern, regulate and control material flows have profound impacts on human health, environmental sustainability and economic growth.

Policy design for sustainable materials management is embedded in a po-litical context with multiple actors and interests. In many cases, measures that strengthen important human rights principles such as the rule of law, transpa-rency and public participation may be equally or more important than specific environmental policies or projects in order to improve materials management.

The purpose of this paper is to describe how and in what way governance matters to achieve a sustainable materials management that contributes positively to development. The paper introduces key concepts, and discusses key governan-ce mechanisms to achieve a more sustainable materials management in a develo-ping country context. It is intended as a source of information and inspiration to individuals and organisations working with environment and development.

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. Empowered lives. Resilient nations. swedish environmental protection agency

Governance Bottlenecks and Policy Options

for Sustainable Materials Management

Order

Phone: + 46 (0)8-505 933 40 Fax: + 46 (0)8-505 933 99

E-mail: natur@cm.se

Address: Arkitektkopia AB, Box 110 93, SE-161 11 Bromma, Sweden Internet: www.naturvardsverket.se/publikationer

The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency

Phone: + 46 (0)10-698 10 00, Fax: + 46 (0)10-698 10 99 E-mail: registrator@naturvardsverket.se

Address: Naturvårdsverket, SE-106 48 Stockholm, Sweden Internet: www.naturvardsverket.se

ISBN 978-91-620-8688-6 © Naturvårdsverket 2013

Acknowlegements

Acknowlegements

T

his report has been written by Gunilla Ölund Wingqvist and Daniel Slunge at the Centre for Environ-ment and Sustainability, EnvironEnviron-mental Economics and Policy Group, Chalmers University of Technology/ University of Gothenburg on behalf of UNDP Montreal Protocol Unit/Chemicals.We would like to thank many colleagues and individuals who commented on various drafts. Valuable comments were received by Maria Delvin (The Swedish Chemicals Agency); Getahun Fanta (Environmental Protection Agency in Ethiopia); David Newman (ISWA/ATIAISWA); Per Rosander (Chemsec), and Martin Medina (International Waste Management expert).

The report also benefitted substantially from comments received from Maria Nyholm, Klaus Tyrkko, Ajiniyaz Reimov and Anna Szczepanek at UNDP Montreal Protocol Unit/Chemicals; Anga Timilsina, Noëlla Richard, Asmara Lua Achcar, Christina Hajdu and Tsegaye Lemma at the Democratic Governance Group, all at UNDP Bureau for Development Policy; and from Maleye Diop, Public Private Partnership for Service Delivery, UNDP Regional Centre Eastern and Southern Africa.

We would also like to express our gratitude to the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) for funding and support.

This report should be cited as: Ölund Wingqvist, Gunilla and Slunge, Daniel, 2013. Governance Bottlenecks and Policy Options

for Sustainable Materials Management - A Discussion paper. United Nations Development Programme and the Swedish

Environmental Protection Agency.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations Development Programme or the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. The designation and terminology employed and the presentation of the material do not imply any expression or opinion whatsoever on the part of UNDP or the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city, or of its authorities, or of its frontiers or boundaries.

Executive Summary

Executive Summary

G

rowing volumes and complexities of material flows pose serious risks to human health and ecosystems during different stages of the materials’ life-cycle. The gradual shift of base for manufacturing and chemical industries to developing countries has contributed to growth and employment but also lead to serious pollution of water, air and soil. Poor people tend to be most adversely affected by pollution and the health impacts from water and air pollution or dumping of hazardous waste is often dramatic. Managing mounting waste streams is currently one of the biggest challenges for rapidly growing urban centers in devel-oping countries. Poor waste collection and dumping of waste in water bodies and uncontrolled dump sites is a major sanitation problem. Waste management is also an issue of global concern since the decay of organic material in post consumer solid waste contributes to about 5 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. The growing flow of materials also includes a growing flow of chemicals in different products making waste streams more complex. Electronic waste constitutes a fast growing and particular challenge.It is increasingly recognized that a technical focus on end-of-pipe solutions is not sufficient to address these problems. A shift towards more upstream approaches that can assure cleaner and more resource efficient mate-rials flows is necessary. The traditional focus on technical solutions needs to be combined with strengthening institutions and governance systems since the way national and local authorities govern, regulate and control material flows have profound impacts on human health, environmental sustainability and economic growth.

Sustainable Materials Management is an upstream approach to handle growing material flows

Sustainable materials management (SMM) is a relatively new approach representing a shift in the international agenda from waste management to management of materials in support of sustainable development. UNDP’s working definition of SMM is:

Management of the product lifecycle (extraction, production, use, and disposal) through use of environmentally benign materials and processes which create opportunities and livelihoods while safeguarding the environment, human health and social equity.

Sustainable materials management involves the whole life-cycle of materials including extraction, production, use and re-use, recycling and final disposal. The purpose is to improve material and resource efficiency, reduce cost, and prevent or reduce the amount of waste (including hazardous waste) that is generated.

Purpose and contents

The purpose of this paper is to describe how and in what way governance matters to achieve a sustainable materials management that contributes positively to development. The paper introduces key concepts, and discusses key governance mechanisms to achieve a more sustainable materials management in a developing country context. The whole life-cycle of materials is included in the paper, although specific attention is placed on chemicals and waste (including recycling). Since SMM is a broad concept covering several different policy areas and stakeholders, there is a wide range of potential governance mechanisms that can be used during the different parts of the materials life-cycle. The aim is hence to provide an overview of the many issues involved rather than to analyze particular governance mechanisms in detail. Since the governance capacity of developing countries is limited the paper also discusses the need to prioritize in order to address the most important govern-ance bottlenecks for sustainable materials management.

Executive Summary

Conclusions:

Fragmented international governance frameworks are badly suited for addressing environmental and social problems associated with growing materials flows. While several international agreements as well

as non-legally binding instruments are in place, each agreement deals with specific parts of chemicals, waste management or other environmental issues. The national action plans developed in line with the different international agreements are often poorly implemented, project oriented and not well integrated in national or sectorial planning and decision-making processes. These problems are receiving increased attention. The need for a bottom-up approach, where governments are accountable to the citizens, improved coordination at the international level and strengthened country systems for effective implementation is increasingly recognized.

Need for improved policy and institutional frameworks at the national level with clear delineation of roles and responsibilities. The policy framework in many developing countries for managing environmental and

health issues related to material flows often mirror the fragmented international agreements. Different entities can be responsible for different international agreements and associated action plans. A crucial flaw in many developing countries is the lack of upstream governance mechanisms, such as an overall national strategy and legislation, with clear delineation of mandates and responsibilities of public bodies and other actors involved during different stages of the materials life-cycle. Such delineation of responsibilities is fundamental for effective use of available resources and facilitates coordination between the many stakeholders involved.

Implementation of policy instruments needed to align incentives of producers and consumers with a sustainable materials management. A fundamental cause of unsustainable materials management is that

environmental and social costs that products cause during the life-cycle are often not reflected in the price of the products. Through implementing policy instruments such as extended producer responsibility, taxes, and charges, the costs of for example product disposal or pollution from industrial production can be internalized in the product price. Other measures to internalize environmental and social costs include subsidy reforms, deposit-refund schemes and product levies. A variety of context specific factors are of course important for policy design and implementation and often a combination of several policy instruments is needed.

Governance for sustainable materials management needs to move beyond the confines of traditional environmental policy. Policy design for sustainable materials management is embedded in a political context

with multiple actors and interests. In many cases measures that strengthen important human rights principles such as the rule of law, transparency and public participation may be equally or more important than specific environmental policies or projects in order to improve materials management. Where, for instance, vested interests work against reforms for controlling industrial pollution or proper handling of hazardous wastes, there are often also weaker constituencies, such as affected communities, unions and environmental organizations, pushing for reform implementation. Accountability mechanisms, such as ensuring the rights to access informa-tion, public participation and access to justice are essential for enabling these constituencies to demand environ-mental improvements. Improved accountability, transparency and public participation can also reduce the risk for corruption and create trust and legitimacy, which facilitates implementation of different policy instruments.

Need for enhanced knowledge and awareness of risks associated with increasing material flows and opportunities with sustainable materials management. There is a lack of knowledge about risks to health,

ecosystems and the economy associated with increasing volumes and complexities of material flows. For instance, information on the “true” cost of a product is seldom available. There is furthermore often low aware-ness of the opportunities with sustainable materials management. Hence, there is a continued need for research, public education, and access to transparent information and awareness creation, in order to expand the under-standing of both risks and opportunities.

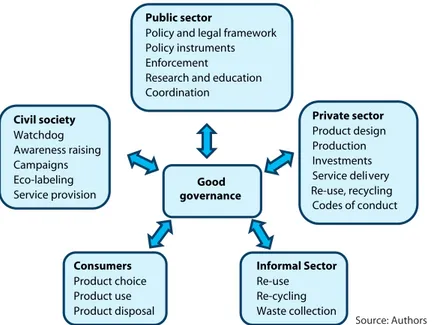

Executive Summary

Governance for sustainable materials management involves multiple actors. While the public sector has a key role in the formulation and implementation of governance mechanisms, such as policies and regulations, the active participation of many other actors are crucial for a more sustainable management of materials: The private sector plays a key role for designing re-usable and re-cyclable products, which increase

per-formance while using less materials and energy through the life-cycle. Moreover, many large companies have adopted their own codes of conduct in order to assure that environmental concerns are addressed throughout the supply chain. Many times these codes of conduct imply that investments and operations fulfill environmental standards that are more ambitious than what national environmental laws require. The financing, technical, and management expertise of the private sector is also critical for delivering environmental services such as waste collection and recycling; and there is a growing use of different types of public-private partnerships.

The informal sector is of tremendous importance for waste collection, re-use and recycling in many

devel-oping countries, and involves millions of people. By working together with organized waste pickers working in the informal sector and recycling enterprises many public authorities have managed to formalize the activities in a way that have reduced the environmental and health hazards associated with these activities, often at a lower cost. When invited to participate, the informal actors also have an important role to play in legal- and policy design.

Civil society organizations play important roles as watchdogs and campaigners for sustainable materials

management. Information technology brings new opportunities for civil society organizations to participate in and monitor international and national decision-making.

Context specific analysis needed to identify key governance bottlenecks and priority interventions for sustainable materials management. There are a wide range of potential governance mechanisms for SMM,

and the specific circumstances in each country will determine which governance mechanisms that need to be strengthened. Also the policy priorities for SMM will depend on the country context and the level of available resources. Most high level income countries have, for instance, well developed policy frameworks and institutions for waste or chemicals management and they increasingly focus on upstream policies for improving resource efficiency. Many low and middle income countries, however, lack appropriate systems for waste and chemicals management causing large health and environmental costs. In these countries improving waste and chemicals management may in some cases be a more important policy priority than improving resource efficiency. As policy priorities and possibilities to act on them may be different for each country, there is a need for a context specific analysis of the challenges, opportunities, needs and priorities in that specific place in order to be com-prehensive and to avoid new add-ons.

Contents

Contents

Acknowlegements . . . .1 Executive Summary . . . .2 List of Abbreviations . . . .7 1 Introduction . . . .8 1.1 Purpose . . . 101.2 Governing the increasing flow of materials . . . 10

2 Governance and Sustainable Materials Management – Key Concepts. . . 14

2.1 Sustainable Materials Management . . . 14

2.2 Governance. . . 15

3 Governance Mechanisms. . . 17

3.1 Policy Design and Instruments for Sustainable Materials Management. . . 17

3.2 The Political Economy of Sustainable Materials Management . . . 18

3.3 Accountability, Transparency, Participation and Integrity . . . 20

3.4 Governance in Different Contexts . . . 23

4 Governance at Different Stages of the Materials Life-Cycle . . . 26

4.1 Governance and production . . . 26

4.2 Governance and product use . . . 33

4.3 Governance and waste . . . 35

5 Conclusions . . . 45

References . . . 47

Appendix 1 Definitions related to sustainable materials management . . . 52

Contents

Figures

Figure 1. Illustration of the life-cycle of materials, including extraction, production, transportation,

use and re-use, recycling, and disposal. . . 8

Figure 2. Global material extraction in billion tons, 1900-2005 . . . 11

Figure 3. Good governance involves multiple actors. . . 15

Figure 4. Stages in the policy making process . . . 18

Figure 5. The political context of policy making . . . 19

Figure 6. Direct and indirect accountability relationships . . . 21

Figure 7. Estimated volume of industrial hazardous waste in Vietnam, 1999-2025 . . . 42

Figure 8. The waste management hierarchy. . . 43

Boxes

Box 1. Key principles of Good Governance . . . 16Box 2. Corruption risks in the waste sector . . . 22

Box 3. Expanding Equitable Delivery of Essential Services in Gabon. . . 23

Box 4. Government support to research and innovation for sustainable materials management . . . 26

Box 5. Has modern design of mobile phones led to dematerialization? . . . 27

Box 6. Detoxification and Private-Public Partnership in Chile . . . 28

Box 7. Civil society initiatives for more environmentally sound production processes . . . 28

Box 8. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) . . . 30

Box 9. The Program for Pollution Control Evaluation and Rating (PROPER) in Indonesia. . . 32

Box 10. Economic cost of poor waste management in Nigeria . . . 35

Box 11. Obstacles to effective implementation of hazardous waste management policies in Vietnam . . 36

Box 12. Need for stricter control of financial flows in Serbia. . . 37

Box 13. Good governance in Brazil, in support of informal waste pickers . . . 39

Box 14. Incentives for Waste Reduction – Volume based collection fees system in Korea . . . 39

Box 15. Challenges for effective management of e-waste. . . 42

Box 16. Participation, priority setting and affordability – experiences from the cleanest city in Tanzania. . . 44

Tables

Table 1. A menu of policy instruments . . . 17Table 2. Internal and external aspects to strengthen governance for sustainable materials management . . . 25

List of Abbreviations

List of Abbreviations

ASM Artisanal and Small Scale Mining

EIA Environmental Impact Assessment

EITI Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative

FDI Foreign Direct Investment

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GHG Greenhouse Gas

HWM Hazardous Waste Management

MEA Multilateral Environmental Agreements

NGO Non-Governmental Organization

ODA Official Development Assistance

OECD Organization for Economic Development

PROPER Program for Pollution Control Evaluation and Rating (Indonesia) RoHS Directive Restriction of Hazardous Substances Directive

SEA Strategic Environmental Assessment

SMM Sustainable Materials Management

SVHC Substances of Very High Concern

SWM Solid Waste Management

UN-CSD United Nations Commission for Sustainable Development UNDP United Nations Development Programme

UN-DESA United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs UN-ECA United Nations Economic Commission for Africa

UNEP United Nations Environment Programme UN-Habitat United Nations Human Settlements Programme WCP Waste and Citizenship Program (Brazil)

Introduction

1 Introduction

Most human activities require input of different types of materials, and leads to different kinds of waste. Eco-nomic development and demographic changes (such as population growth) tend to increase the demand for materials and the amounts of waste generated. While processed materials, including chemicals, contribute to economic development, the absence of good governance of materials can pose significant risks to human health and the environment, for instance by over-extraction of natural resources or (unintended) releases of pollutants and waste into the environment. If the functions of the ecosystems are seriously impaired, economic production can slow down, or even be negative1.

Lately, the international agenda has moved away from simply focusing on managing waste (as an end-of-pipe solution), towards setting up up-stream systems for managing materials in support of sustainable development. The importantce of applying a life-cycle approach is recognized by the Rio Outcome Document2. Integrating the whole lifecycle of materials includes extraction of raw material, processing, transportation, use and re-use, recycling and final disposal (see Figure 1). Focusing on the whole life-cycle of materials instead of only the waste aims, amongst others, to increase material and resource efficiency, reduce costs, and prevent or reduce waste (including hazardous waste) generation.

Figure 1. Illustration of the life-cycle of materials, including extraction, production, transportation, use and re-use,

recycling, and disposal.

Sustainable Materials Management

Transportation Resource

Extraction ManufacturingProduction

Waste Use Final Disposal Landfill Transportation Tra nsp ort ation Recy cle R euse Reuse

Illustration: Ann Sjögren, Typoform

1 Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005 2 UN General Assembly, 2012

Introduction

Hence, it is increasingly recognized that a technical focus on end-of-pipe solutions to environmental problems is not sufficient to obtain sustainable development. Instead there is growing attention to the importance of institutions and governance systems to manage a wide range of environmental challenges and impacts. The Environmental Sustainability Index Report (2005) highlights that governance measures, including the rigor of regulation and the degree of cooperation with international policy efforts, correlate highly with overall environ-mental success. This result suggests that emphasis on good governance is justified, since it shows the correlation between environmental sustainability and governance, and notes that the most important bivariate correla-tions all include elements related to governance, such as civil and political rights, government effectiveness, and participation. Consequently, this suggests that countries with democratic institutions are more likely to focus on environmental challenges, and countries that pay attention to environmental policy and effective regulation are more likely to produce successful environmental outcomes. Measures that strengthen important human rights principles such as the rule of law, transparency and public participation may be equally or more important than specific policies or projects aiming to improve waste management or address other specific environmental problems.3

3 Ölund Wingqvist et al 2012 Men fishing near industrial site. ©UNDP

Introduction

The sustainable management of materials is an integral part of development and cannot be considered in isolation from it. The way national authorities govern, regulate and control, materials flows will have important implications for food, water and energy security, human health, environmental sustainability, trade opportuni-ties, and long-term economic growth. On the other hand, the lack of such enabling environment and the poor performance of governments result in bad health as well as “wasted resources, undelivered services, and denial of social, legal, and economic protection for citizens – especially the poor.”4

1.1 Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to describe how and in what way governance matters to achieve a sustainable materials management (SMM) that contributes positively to development. The paper introduces key concepts, and identifies and describes key governance mechanisms to achieve a more sustainable materials management in a developing country context. The whole life-cycle of materials is included in the paper, with a special focus on waste as this is highlighted as the most critical life-cycle phase for low-income countries.

Since SMM is a broad concept covering several different policy areas and stakeholders, there is a wide range of potential governance mechanisms that can be used during the different parts of the materials life-cycle. The aim is hence to provide an overview of the many issues involved rather than to analyze particular governance mechanisms in detail. Since the governance capacity of developing countries is limited, the paper also discusses the need to prioritize in order to address the most important governance bottlenecks for sustainable materials management.

The paper has been commissioned by the UNDP/EEG Montreal Protocol Unit/Chemicals and builds on an exten-sive literature review and interviews with international experts.

The paper proceeds as follows: The first section introduces the subject and gives an overview of the problems that can arise if the increasing flows of materials are not governed with care. The second section introduces key concepts in relation to SMM and governance. The third section identifies policy instruments for SMM and discusses governance bottlenecks and political economy constraints for implementing policy instruments. This section also discusses the importance of accountability, transparency and public participation for SMM, and elaborates on the importance of context specific analysis. The fourth section analyses governance mechanisms of particular importance in different life-cycle phases. Conclusions are made in the fifth and last section.

1.2 Governing the increasing flow of materials

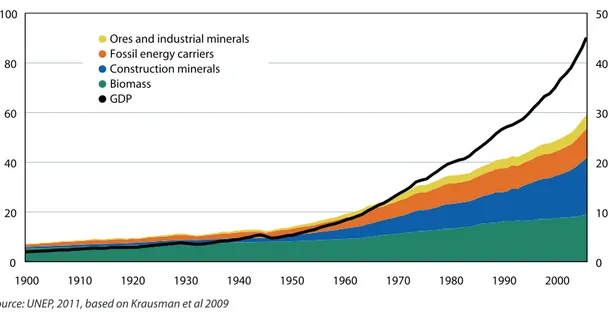

With industrialization, urbanization and modernization, the world has witnessed a rapid increase of material flows. This increased flow of materials leads, in turn, to increased demand for natural resources, such as timber, minerals and water, as well as other inputs, such as energy and chemicals. It also leads to increased generation of waste, and to mounting costs. Figure 2 illustrates the increase in global extraction of different natural resources between 1900 and 2005.

Processed materials, including chemicals, contribute to economic development. With a business-as-usual approach, the righteous demands of developing countries for poverty alleviation, industrialization, moderni-zation and economic growth, will increase the amount of material flows and waste generated. The idea behind SMM is to decouple economic growth from a corresponding increase in material and waste flows and associated environmental impacts, by reducing, re-using and recycling of materials and improving energy efficiency. OECD (2002) refers to decoupling as “breaking the link between environmental bads and economic goods”. As can be seen in Figure 2, there has been a relative decoupling between global GDP and the global material extraction since the mid twentieth century. However, there has not been an absolute decoupling since the total amount of extracted materials has increased due to increased consumption.

Introduction

Figure 2. Global material extraction in billion tons, 1900-2005

Source: Krausmann et al., 2009 Material extraction Billion tons 100 80 60 40 20 0 50 40 30 20 10 0 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 GDP trillion (1012) international dollars

● Ores and industrial minerals

● Fossil energy carriers

● Construction minerals

● Biomass

●GDP

Source: UNEP, 2011, based on Krausman et al 2009

Some materials are particularly difficult to manage because they contain hazardous chemicals. Chemicals are an ingredient in nearly all man-made materials, and new chemicals are increasingly being introduced to society. Chemical substances and processed materials are major contributors to national economies and can, when managed appropriately, contribute to economic and human development. However, without good governance, material flows can pose significant risks to human health and the environment.

Although most chemicals are produced in OECD countries, developing countries are increasingly both producers and users of chemicals, inter alia for industrial and agricultural purposes5. Industries, such as mining companies, use, release, and need to manage, different types of chemicals, heavy metals and other types of hazardous mate-rials. National authorities need to formulate and implement policies, regulate, issue permits, monitor compliance and enforce the regulation. Foreign and domestic investors are often invited to boost national economies and create job opportunities. However, if the legislation is piecemeal or changing, or if enforcement is inadequate, the rules of the game will be uncertain. The uncertainty will become a business risk for investors: there might be competitive disadvantages for those firms that obey to the rules, and it may be difficult to adhere to rules that are changing or difficult to predict. Investors try to avoid risks and are more likely to look for certainty elsewhere. On the other hand, the risks are reduced if good governance prevails.

Waste management is also an issue of global concern since the decay of organic material in post consumer solid waste contributes to about 5 percent of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, not counting for the emissions caused in material and product manufacture or during the use phase. Ideally, in a life-cycle perspective, the generation of waste, including hazardous waste, should be minimized through implementation of SMM activi-ties such as dematerialization and detoxification (see Appendix 1). The remaining waste need to be managed applying the life-cycle approach, including improved reuse, recycling and recovery of materials and energy. However, in the foreseeable future there will be a continued need to manage waste streams. Indeed, according to UN Habitat, managing solid waste is currently one of the biggest challenges for urban areas 6. In addition to the already unsustainable amounts of waste generated today, significantly increased amounts of municipal,

5 Alo, 2009 6 UN Habitat, 2010a

Introduction

industrial and hazardous waste will be generated due to the increase in population and the GDP/capita growth in developing countries, mounting to a 70% global increase in urban solid waste, with developing countries facing the greatest challenge 7.

Waste is accumulating in cities, towns and uncontrolled dumpsites. Almost half of the waste generated in Africa (40-50%) is not properly disposed of. The waste management services are often the worst in informal settle-ments or less well-off neighborhoods. Hazardous waste is often dumped together with non-hazardous waste, or released without proper management and treatment, presenting hazards to human health, ecosystems and sustained economic growth. There are a multitude of reasons for the low level of waste management coverage and poor services, including inadequate resource mobilization for operations and investments, inappropriate methods of finance, and an over-reliance on imported equipment, which can make servicing and spare parts acquisition a problem. Furthermore, there is often a lack of inclusivity, transparency, and weak institutions.8 This is further compounded by a lack of policy coherence, coordination among government agencies and integrated implementation across sectors.

The waste management problems are worse in African countries plagued by political instability and conflict, such as Côte d’Ivoire, Sudan, Somalia and Liberia. Conflict situations provide conducive environments for illegal transboundary traffic of hazardous wastes. 9 Large migration flows, for instance from internally displaced persons, put additional strains on already weak waste management capacities. At the same time, waste management and recycling activities can provide livelihood opportunities in post disaster or conflict situations, as well as contributing to the strengthening of the relationship between the state and the people when services are pro-vided and income-bringing waste management and recycling activites are supported by the state institutions. Of special interest are the fast-growing streams of e-waste. According to UN-DESA (2010) 20-50 million metric tonnes of e-waste are generated worldwide each year. Almost all discarded computers (more than 90%) are exported from the developed to developing countries, purportedly for recycling.10 The flow of e-waste to developing countries is faster than the development of policies, safeguards, legislation, and enforcement. This institutional vacuum leads to serious human and environmental problems in importing countries.11 Common features of the developing countries receiving e-waste are the lack of environmental regulation, and the lack of capacity and infrastructure to manage this type of waste. Strategic Approaches to International Chemicals Management (SAICM) confirms that e-waste is one of the emerging issues that should be given priority12. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (2011) highlights that on the one hand environmental degrada-tion, including hazardous waste, chemical contamination and pollution have increasingly adverse effects of the realization of human rights and human well being. On the other hand, human rights such as access to informa-tion, access to justice and participation in public affairs are also tools to address environmental concerns.13 Experiences from for example the environmental movements in China and India indicate that public discussion and organization around environmental issues can serve as useful entry points to improve democratic processes and strengthen awareness about rights.14

7 Hoornweg; Bhada-Tata, 2012 8 UN Habitat, 2010b

9 UN-ECA, 2009; and World Bank http://go.worldbank.org/LSQPNO06L0 10 UN-ECA, 2009

11 Osibanjo, 2009

12 SAICM website,: http://www.saicm.org/ 13 UN General Assembly, 2012

Introduction

To sum up, the increasing volume and complexity of material flows associated with economic growth create serious risks to human health and ecosystems. Sustainable materials management, which moves beyond the confines of traditional environmental policy and project oriented approaches to addressing environmental challenges, attempts to enable positive changes throughout the life-cycle of materials, in order to improve efficiency and reduce costs. Governance aspects are crucial for creating an enabling environment for sustain-able materials management.

Governance and Sustainable Materials Management – Key Concepts

2 Governance and Sustainable Materials Management

– Key Concepts

This section elaborates on key concepts related to sustainable materials management and governance.

2.1 Sustainable Materials Management

Sustainable materials management (SMM) is a relatively new approach representing a shift in the international agenda from waste management to management of materials in support of sustainable development. The SMM approach applies focus on the entire system of material flows throughout the life cycle (see Figure 1). Being a new concept there are different definitions of SMM, however all point to the need of utilizing a life-cycle approach and integrating different policy areas.

In this document, the definition used for SMM is:

“Management of the product lifecycle (extraction, production, use, and disposal) through use of environmentally benign materials and processes which create opportunities and livelihoods while safeguarding the environment, human health and social equity.”15

OECD (2010) identifies four policy principles for SMM16. (i) Preservation of Natural Capital

(ii) Designing and Managing Materials, Products and Processes for Safety and Sustainability from a Life-cycle Perspective.

(iii) Use the full Diversity of Policy Instruments

(iv) Engage all parts of Society to take active responsibility to obtain sustainable materials management. The first two policy principles often include strategies related to detoxification and dematerialization, pollution prevention and control, and appropriate management of waste, including the “3R”: reduce, reuse, and recycle (for more information, see Appendix 1).

The strategies to obtain a sustainable materials management are interlinked, all aiming at understanding and mitigating the adverse effects of material flows on ecological and societal systems in a life-cycle perspective. Due to this interlinkage, it is critical to apply an integrated approach, taking into account different policy areas, sectors, and stakeholders. These aspects, highlighted in the third and fourth policy priorities, are important aspects of the good governance agenda, further explored in section 2.2.

15 UNDP Montreal Protocol Unit/Chemicals , 2011

16 OECD (2010) working definition of SMM is: “an approach to promote sustainable materials use, integrating actions targeted at reducing negative environmental impacts and preserving natural capital throughout the life-cycle of materials, taking into account economic efficiency and social equity”.

Governance and Sustainable Materials Management – Key Concepts

2.2 Governance

Governance refers to how power and authority are exercised and distributed, how decisions are made and implemented, and to what extent citizens are able to participate in decision-making processes and hold deci-sion makers accountable. Thus, governance is about making choices, decisions and tradeoffs, and it deals with economic, social, political and administrative aspects.

There is not yet a strong consensus on how to define ‘governance’17. For the purpose of this paper, the UNDP approach to governance is used:

“Governance can be seen asthe exercise of economic, political and administrative authority to manage a country’s affairs at all levels. It comprises the mechanisms, processes and institutions through which citizens and groups articulate their interests, exercise their legal rights, meet their obligations and mediate their differences.”18 Governance for SMM involves multiple actors. While the public sector has a key role in the formulation and implementation of governance measures, such as strategies and regulations, the private sector and civil society also have important roles and responsibilities in SMM governance. Examples of such governance mechanisms are eco-labeling schemes to encourage consumers to choose products with less environmental impacts, and corporate social responsibility initiatives. Yet another example of governance mechanisms is local governments partnering with the informal waste sector and the official recognition of waste federations and cooperatives. These actors within SMM also help strengthen the governance capacity. Furthermore, the informal sector and consumers are key actors for SMM (see Figure 3).

Good governance (sometimes referred to as ‘democratic governance’) aims at ensuring inclusive participation, making governing institutions more responsive and accountable, and respectful of international norms and principles. The key principles of good governance are consistent with the most important human rights princi-ples (see Box 1).

Sustainable materials management is a fundamentally multi-dimensional concept, involving several policy areas such as natural resource poli-cies, product life-cycle polipoli-cies, waste management policies, fiscal policies, and environmental protection and pollution prevention policies. It also involves different types of systems: ecological, industrial, and societal systems and a multitude of actors, from governments, private sector, and local authorities to non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and individuals. Due to the complexity, SMM calls for integration, coherency, and coordination as important aspects of effective and efficient governance (Box 1).

17 Kaufmann and Mastruzzi, 2010 18 UNDP, 1997 Civil society Watchdog Awareness raising Campaigns Eco-labeling

Service provision governanceGood Public sector

Policy and legal framework Policy instruments Enforcement

Research and education Coordination Private sector Product design Production Investments Service delivery Re-use, recycling Codes of conduct Informal Sector Re-use Re-cycling Waste collection Consumers Product choice Product use Product disposal Source: Authors

Governance and Sustainable Materials Management – Key Concepts

Box 1. Key principles of Good Governance Effectiveness and

efficiency Processes and institutions should produce results that meet needs while making the best use of resources. Accountability Decision-makers (policy makers and service providers) in government, the private sector and civil society organizations, should be accountable to the public for what they do and for how they do it.

Transparency Is built on the free flow of information in society. Processes, institutions and information should be directly accessible to those concerned.

Participation All men and women should have a voice, or through legitimate intermediate institutions representing their interests, in decision-making and the develop-ment and impledevelop-mentation of policies and programs that affect them. Such broad participation is built on freedom of association and speech, capacities to participate constructively, as well as national and local governments fol-lowing an inclusive approach.

Rule of law and

non-discrimination Legal frameworks should be fair and enforced impartially, with equity and in a non-discriminatory way. All citizens, irrespective of gender, religion, sexuality, ethnicity, and age, are of equal value and entitled to equal treatment under the law, as well as equitable access to opportunities, services and resources. All people in society should have opportunities to improve or maintain their well-being.

Integration Governance should enhance and promote integrated and holistic approaches, involving a multitude of sectors and policy areas.

Coordination and

Coherency Due to the multidimensional nature of SMM, coordination is needed to effec-tively integrate several policy and institutional areas and a multitude of stake-holders. Policies and actions must be coherent and consistent, strive towards the same goals, and be easily understood.

Responsiveness Institutions and processes should serve all stakeholders and respond properly to changes in demand and preferences, or other new circumstances.

Source: UNDP 2010; UNDP 1997; UN 2nd WWDR 2006

Given the many different perspectives of what good governance encompass, the good governance agenda can be seen as being unrealistically long and overwhelming for poor countries19. However, achieving good govern-ance is a process, and can be introduced step-wise according to needs, priorities and abilities. Furthermore, SMM can be utilized to strengthen overall governance aspects through providing entry points for participation, transparency, accountability, and the building of trust and legitimacy.

Governance Mechanisms

3 Governance Mechanisms

This section identifies policy instruments for SMM and discusses governance bottlenecks and political economy constraints for implementing policy instruments. The section also discusses the importance of accountability, transparency and public participation for SMM, and elaborates on the importance of context specific analysis.

3.1 Policy Design and Instruments for Sustainable Materials Management

There is a strong rationale for governments to apply a variety of different policy instruments for moving towards a more sustainable materials management. The environmental and social costs that a product causes during its life-cycle are often not reflected in the price of the product. In the absence of strong penalties it may for example be cheaper and easier for producers to dump hazardous waste illegally than to properly dispose of it. Correcting for these externalities20 through for examples taxes or charges typically leads to higher welfare. The lack of knowledge and information on health and environmental risks from use of different products and chemicals provides another rationale for policy instruments. Through instruments that improve access to information, risks and uncertainty among producers and consumers can be decreased. Similarly waste collection is a public good and (local) governments’ efforts to improve waste collection can improve welfare. In essence, “SMM policy development is no different to policy development in other areas. The aim should be to address failings in the market, and as far as possible, the benefits of policy should outweigh the costs of its deployment.”21To “use the full diversity of policy instruments” is one important policy principle for SMM. As can be seen in Table 1 there is a broad menu of policy instruments that can be used for steering towards more sustainable materials management. Each column in Table 1 represents a category of policy instruments (but the rows do not have any particular meaning). Taxes, subsidies and charges are examples of instruments that directly act like a price and in this sense they are “economic” or “market-analogous”. Examples for chemicals and wastes include waste disposal fees; environmental product levies on items that are difficult to dispose of (e.g. bulky or hazardous items like tires, batteries, electronics, waste oils, etc.); and deposit refund schemes, involving a sum per unit paid by the producer or importer to the government, with a percentage of the deposit refunded when the product is disposed of correctly.

Table 1. A menu of policy instruments

Price-type Rights Regulation Info/Legal

Taxes Property rights Technological standard Public participation

Subsidy Tradable permits Performance standard Information disclosure

Charge, Fee/Tariff Tradable quotas Ban Voluntary agreement

Deposit-refund Certificate/Permit Zoning Liability

Refunded charge Common property

Source: Sterner and Coria 2012

20 Externalities are unintended effects, impacting not only on the owner or user but also on third parties that may be

public or private actors within or beyond national borders, caused by market failures

Governance Mechanisms

“Rights-based” instruments include property rights, which for example can facilitate for individuals or communi-ties to appeal against pollution from neighboring industries. Permits that grant a producer the right to emit to air or water is however also an instrument in this category. An example of a tradable permit is national emission rights or extended to international trade as in the case of the Kyoto Protocol. The column regulation should be fairly self-explanatory and contains in fact much of what is the bread and butter of ordinary environmental management by Environmental Protection Agencies around the world. Extended producer responsibility is an example of a policy instrument in this category, which is of particular importance for sustainable materials management as this is commonly used for material and product groups placed on the market in large quanti-ties. The final column is referred to as legal or informational policy instruments. It includes both labeling and voluntary agreements, liability rules, and so forth. In order to effectively address environmental problems it is common that a combination of several different environmental policy instruments need to be used22.

3.2 The Political Economy of Sustainable Materials Management

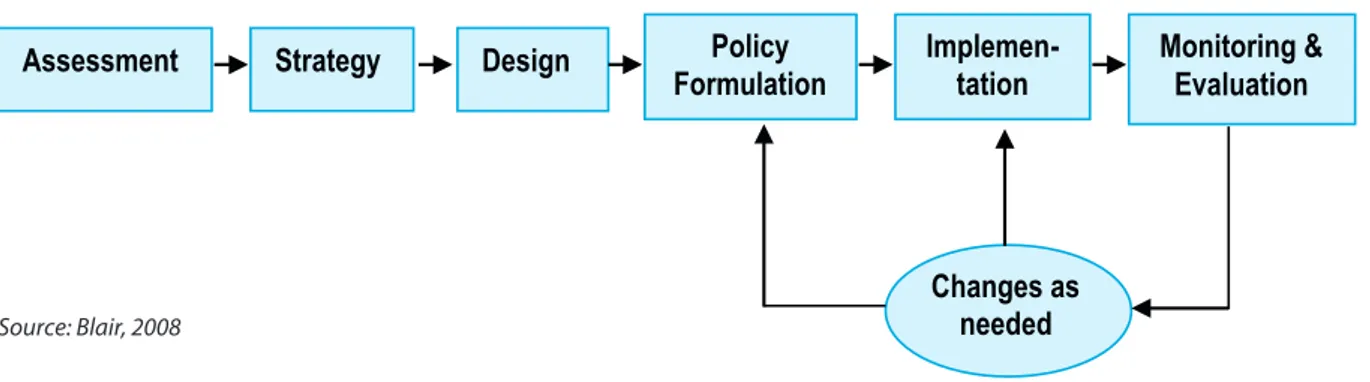

Policy making is often portrayed as taking place during different stages, moving logically from initial assessment through formulation and implementation, with a feedback system provided by monitoring and evaluation to effect improvements (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Stages in the policy making process

Assessment Strategy Design Policy

Formulation Implemen-tation Monitoring & Evaluation

Changes as needed Source: Blair, 2008

Real world decision-making is obviously a lot more complex than the linear model in Figure 4. The process of policy formulation and implementation is embedded in a political context with a multitude of actors, interests and relationships (Figure 5).

In such a crowded policy space the importance of addressing problems associated with for example industrial pollution or electronic waste compete with other important problems for attention and resources. Vested inter-ests may even forcefully work against that industrial pollution becomes a policy priority. Policy formulation and the choice of policy instruments for SMM are considerably more complex in reality than in theory. Instead of choosing the policy instrument that would be most efficient from an economic perspective (sometimes referred to as 1st best policy making), the political feasibility of implementing different instruments (in a 2nd best setting) becomes a key criteria.

The “stages model” of policy making (Figure 4), embedded in a political context can be used to discuss govern-ance mechanisms and bottlenecks related to sustainable materials management.

Governance Mechanisms

Figure 5. The political context of policy making

Int’l NGOs Media

Executive Bureaucracy Judiciary Military Legislature Old elites Business Civil society Political parties Foreign donors Policy process Source: Blair, 2008

Assessment: Many developing countries lack robust systems for collecting and processing data on

environ-mental and social impacts related to different material flows. As a consequence policy makers often need to rely on ad hoc assessments, which severely limit the possibilities for setting priorities and making difficult trade-offs. Developing strong academic research environments and finding ways to draw on this capacity in the policy formation process can be an important way to address this governance bottleneck. Governments can also develop procedures for a systematic use of strategic environmental assessments (SEA) or other types of assessment procedures in order to both enhance the evidence base for policy making and as a way of involving different stakeholders early in the decision-making process. Such assessments can also identify potential losers of suggested reforms and compensation mechanisms that may have to be considered in order to facilitate implementation23.

Policy formulation: In many developing countries the policy and institutional framework for environmental

management has been strongly influenced by international processes related to the Multilateral Environmental Agreements (MEAs). Some of these MEAs have a bearing on SMM, for instance related to waste and chemicals management (in particular the Basel, Stockholm, and Rotterdam Conventions, see Appendix 2). However, since each agreement only deals with a specific part of chemicals and/or waste management this has many times resulted in a fragmented approach. Commonly identified weaknesses include a lack of coherency between different pieces of legislation and overly ambitious national action plans. This is an important concern for sus-tainable materials management since there is a need for coherency and coordination between the many policy areas involved.

Implementation: A major governance constraint for SMM is related to the difficulty in implementing policies,

strategies and action plans that countries develop as part of the process of implementing different multilat-eral environmental agreements. This lack of implementation can only to a certain degree be explained by a lack of capacity in terms of financial resources, staff and knowledge. Instead research indicate that these action plans often are developed for the purpose of seeking project financing and fail to connect to core national development planning and budget processes, thus failing to consider the existing governance reality24.

23 World Bank and others, 2011 24 Sharma, 2009

Governance Mechanisms

Since environment ministries are typically weak and have difficul-ties in getting resources from the treasury, international finance for environmental projects is often highly attractive in developing countries. However, a project ori-ented approach may paradoxically lead to a weakening of environ-mental authorities. An analysis of developing country environmental authority budgets reveals rela-tively large portfolios of externally financed projects25 and low inter-nally raised budgets for recurrent expenditures to cover core func-tions such as monitoring, control, enforcement and supervision.

The problems outlined above are receiving increasing attention from international organizations such as UNDP and UNEP who now increasingly focus on integration of chemicals management and other environmental issues into national development planning processes26.

Many developing countries also have weak mechanisms for facilitating cross-agency and cross-sectorial dialogue, which is key to effective implementation of chemicals and waste policies. Without effective policy coordination procedures, there may be uncertainties in the legislation, or unclear or overlapping responsibilities, which will affect implementation. Moreover, without an integrated approach to policy making, there is a risk that one problem is solved while another problem is created.

Monitoring and evaluation is especially important in policy areas such as chemicals management

character-ized by large uncertainties, risks and ambiguities. Information generated in this stage of the policy cycle can provide important feedback to policy makers and lead to improved governance. Making information on policy implementation publicly available can facilitate for different stakeholders in engaging in this phase of the policy cycle and contribute to improved accountability.

3.3 Accountability, Transparency, Participation and Integrity

Accountability, transparency and participation are important ends in themselves. They are also crucial govern-ance mechanisms for sustainable materials management. In cases, where for instgovern-ance vested interests work against reforms for controlling industrial pollution or proper handling of hazardous wastes, it is important that there are constituencies such as affected communities, unions, environmental organizations and con-cerned politicians that can push for reform implementation. Ensuring the rights to access to information, public

25 The study included case studies from Tanzania, Mozambique, Mali and Ghana. As an example: in 2005/06 the Ghanaian

Environmental Protection Agency was managing 28 separate projects financed by 10 different funding agencies (Bird and Lawson, 2008)

26 UNDP - UNEP, 2009

Dang Jiuru smiles as he collects an apple from his orchard in Luochuan County, Shaanxi Province, China. ©L. Yi

Governance Mechanisms

participation and access to justice in environmental matters in line with the Aarhus Convention27 are essential for enabling these constituencies to demand environmental improvements28. Access to information can include the right to examine public records, obtain data from environmental monitoring or reports from environmental agencies. Evidence indicates that more transparent countries are less corrupt29. Transparency enables detec-tions of wrongdoings, increases awareness of financial commitments and budget allocadetec-tions and help keeping decision makers accountable. On the other hand, lack of transparency fosters rumors and discontent, makes it difficult to understand the basis of public decisions and act on them and to enforce the law as proof is hard to generate.30

Transparency should be combined with meaningful participation of stakeholders that have the capacity to process information and act on it. Therefore, education and a free press are important components31. In some countries limitations in the freedom of press is a severe constraint to accountability since media play a central role in ensuring the rights to access information. More traditional forms of accountability, such as monitoring, enforcement and sanctions, are good complements to transparency and participation. If, for instance, a service is not delivered or holds inadequate quality, the consumer of that service should be able to file complaints towards the service provider and the complaints should lead to some kind of response.

At a more general level access rights are rooted in civil and political human rights and as such a part of interna-tional law. Using a human rights-based approach, accountability can be expressed as relations between the public as having rights to access to information and justice and the state being the bearer of duty to fulfill these rights. Strengthening accountability is also an essential governance mechanism for ensuring equal access to public services, such as waste collection. Currently the solid waste management problems in many cities are becoming large, going beyond the capacity of most municipalities and state governments to meet them. Public organiza-tions alone cannot deal adequately with the increasing diversity and volumes of urban waste. As a result it is increasingly common to promote public-private partnerships and let private actors, both formal and informal, provide waste collection or recycling services. However, for various reasons (see section 4.3) poor neighborhoods are often subject to much inferior waste collection services than richer neighborhoods.

When involving other service providers than public, the accountability relationship changes. The private ser-vice provider is now also accountable to the public. If the serser-vices are not delivered, the consumer should be able to file complaints towards the service provider, to hold the service provider directly accountable. Often, however, there is no direct accountability of the provider to the consumer. Instead, the accountability is

indi-rect, through citizens influencing policy-makers, and policymakers influencing providers. When private companies fail as providers of public services it is ulti-mately the public authority, in this case a municipality that is responsible and should be held accountable.32 Figure 6 illustrates how addressing this problem can involve the strengthening of several accountability relationships.

27 The Aarhus Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in

Environmental Matters

28 Ahmed and Sanchez Triana, 2008 29 Kolstadt et al., 2008

30 Ölund Wingqvist et al., 2012 31 Kolstad et al., 2007

32 World Bank, 2004

Figure 6. Direct and indirect accountability relationships

Source: World Bank 2004, p 6

Policymakers

Providers

Poor people

Governance Mechanisms

The fight against corruption and enhancement of integrity are other important aspects of governance. Integrity refers to adherence to a set of moral or ethical principles, such as impartiality, legality, public accountability, and transparency. When citizens cannot trust that public servant will serve the public interest with fairness and manage public resources properly, the legitimacy of the government will be suffering. On the other hand, fair and reliable public services inspire public trust. Waste management is prone to corrupt behavior in different ways (Box 2).

Box 2. Corruption risks in the waste sector

Is the waste management sector particularly susceptible to corruption?

In many developing economies, the waste sector is dominated by poor and vulnerable segments of the population that often are politically and socio-economically marginalized. Such marginalization limits their ability to have their voice heard and influence decision-making processes and governing institutions. Hence, the poor may be exposed to exploitation, including corruption, by those controlling power. The sector remains predominantly informal, with environmental regulations and safeguards missing or (if they exist) poorly enforced. In the absence of any formal authority, informal/organized crime groups, such as gangs and drug cartels, often set and enforce the rules. On the other hand, the people involved often operate as individual entrepreneurs, lacking the capacity and resources to get organized. With no organization and political capital, it’s hard for these people to shield themselves from corruption. Where there are weaker governance and legal/institutional regulations and enforcement, big companies (e.g., chemical industries) may find it alluring to pay bribes and bypass environmental safety standards, for instance dumping hazardous materials, which would have otherwise cost the companies more money. Competition among companies to reduce their costs tends to encourage them to transfer external costs to the poor in developing countries where these companies operate.

At the international level, the emerging trends around activities such as exportation of e-waste or chemical wastes, etc., are creating new challenges for domestic entities, which may not have the required knowledge and mechanisms to deal with potential negative consequences. The interests of communities might not be adequately represented in decisions involving cross border deals and, furthermore, these deals could be exploited for money laundering and extortion.

What are the type and nature of corruption risks?

Bribery and kickbacks

Grand corruption in issuing licenses to big companies or protecting them from adhering to the required environmental standards

Bureaucratic corruption

Extortion by local powerful interest groups

Money laundering

How can these risks best be mitigated?

Empowering the stakeholders including watchdog organizations, media and others

Social mobilization and improving organizational capacities of the poor and vulnerable

Raising awareness among the general public as well as non-state actors

Doing corruption risk assessment and identify and fix legislative loopholes that promote and encourage corrupt practices

Governance Mechanisms

As mentioned above, participation is an important governance mechanism. When citizens, companies and aca-demia are invited to participate in policy and decision making, and when views and complaints are responded constructively to, the decision making is understood to be fairer33. Participation may also contribute to strength-ening the legitimacy of the government as well as the quality of formulation and implementation of reforms. To achieve sustainable outcomes, SMM calls for involvement of different actors at different levels. However, in order to be able to participate, citizens must both have the possibility (i.e. be invited), and the capacity, to do so. Box 3 illustrates how Libreville, Gabon, in a partnership with UNDP, utilized i.a. capacity development to improve public participation and, ultimately, the waste management system in a poor area of the city.

Box 3. Expanding Equitable Delivery of Essential Services in Gabon

Gabon is one of the most urbanized countries in Africa. Libreville, its capital, is home to 39% of the country’s population. Rapid urbanization has generated social challenges as it has led to social exclusion of marginal-ized groups. For example, the development of residential areas in inappropriate locations marginalmarginal-ized from the rest of the capital has made it difficult for the people in these areas to access basic social services such as clean water, improved sanitation, basic health care, electricity, transport, and garbage collection. As a result there are high rates of infectious diseases and parasitic infections in these poorer quarters of Libreville.

In partnership with the municipality of Libreville, in 2004 UNDP launched a pilot project to put in place urban waste management system. The “Gestion Urbaine Partagee” project was operationalized in the least integrated areas of Libreville. The aim was to fight poverty, reinforce local capacities and improve environ-mental management.

UNDP focused on capacity building within the Libreville municipality, provided technical equipment and materials, reinforced the financial capacities and sensitized the local communities through an information, education and communication programme. In 2006, the pilot project which initially covered four residential areas was extended to cover 37 residential areas out of 102 in Libreville.

Eventually, the Government took the decision to integrate the programme components into its national waste management agenda and work continues throughout the country to this day to integrate the poorer urban communities into this waste management system. By facilitating access to basic services that were their due, UNDP’s efforts helped transform the quality of life of residents in the poorest parts of the capital. Source: Maleye Diop, UNDP-PPP for Service Delivery, Personal communication May 2011.

3.4 Governance in Different Contexts

Since sustainable materials management covers several policy areas there is a wide range of potential govern-ance mechanisms and policy instruments available that may be relevant. In order not to end up with long action plans or wish lists it is necessary to prioritize and focus on addressing key “governance bottlenecks”34 . However, assessing which are the most important governance bottlenecks for sustainable materials management is a complex endeavor and the results are highly dependent on the country or local context.

In most low income countries with poor waste management it is probably more relevant to focus on improving waste management than on product design. But improving waste management is in itself a complex policy area where tough priorities are needed. Is it, for example, more important to focus on regulating the use of chemicals in order to detoxify waste streams, than improving collection and recycling rates of solid waste in urban areas? 33 Helen Clark, 2011

Governance Mechanisms

Given that resources are limited it is not only important to prioritize between what to do but also to think hard about the sequencing of different activities. In some cases there may for example be an urgent need to invest in expensive waste disposal facilities. However, without a governance framework that assures the sustainability of the investment, there is a risk that resources will be wasted. A crucial flaw in many developing countries is the lack of upstream governance mechanisms, such as an overall national strategy and legislation, with clear delineation of the mandate and responsibilities of public bodies and other actors involved during different stages of the materials life-cycle. Such delineation of responsibilities is fundamental for effective use of available resources (finance, technical/ technological means, information, expertise) and facilitates coordination between the many stakeholders involved.

Governance Mechanisms

In order to identify priorities it is also useful to distinguish between governance mechanisms that are primarily within the confines of authorities responsible for different sustainable materials management aspects and mechanisms which are external to these authorities, the “enabling environment” (Table 2).

Table 2. Internal and external aspects to strengthen governance for sustainable materials management

Authorities with SMM mandate

(internal aspects) Enabling environment (external aspects)

Policy development (policies, laws, regulations, policy instrument) Policy implementation (inspection, compliance and enforcement)

Policy coordination and responsiveness Research and assessment (research, evaluation, environmental information systems)

Sector integration (sector responsibility, producer responsibility)

Knowledge and information about the importance of environment and climate change

Constituencies demanding improved management of materials including chemicals

SMM is a prioritized policy issue

SMM regulations with clearly defined mandates and responsibilities

Horizontal and vertical communication and coordination Rule of Law, low corruption

Transparency, public participation, accountability Source: Authors based on OECD 2009

Authorities with a mandate for SMM are responsible for policy formulation and implementation, for coordina-tion with other public authorities and other stakeholders and be responsive to their needs. Authorities can furthermore promote research, education and assessments to improve knowledge and awareness, and applying a holistic and integrated approach through sector integration.

Outside the direct influence of the authorities mandated with SMM is the important enabling environment. These external aspects include the general knowledge and awareness of risks with increasing material flows and opportunities with SMM: regula-tions; strength and leverage of dif-ferent institutions and constituencies; structures that enable communication and coordination; corruption and rule of law; and transparency, participation and accountability in society. These external aspects are outside the direct influence of the authorities with an SMM mandate, but can be influenced indirectly, through promoting good governance principles.