Background document for the Stockholm Hearing, 17-18 February

Background document for the Stockholm Hearing, 17-18 February

Background document for the Stockholm Hearing, 17-18 February

Background document for the Stockholm Hearing, 17-18 February

Background document for the Stockholm Hearing, 17-18 February

2000,

2000,

2000,

2000,

2000,

Green Purchasing of Foodstuffs

Green Purchasing of Foodstuffs

Green Purchasing of Foodstuffs

Green Purchasing of Foodstuffs

Green Purchasing of Foodstuffs

arranged by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency

arranged by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency

arranged by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency

arranged by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency

arranged by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency

and the European Green Purchasing Network

and the European Green Purchasing Network

and the European Green Purchasing Network

and the European Green Purchasing Network

and the European Green Purchasing Network

Final report

Final report

Final report

Final report

Final report

Green Purchasing of

Foodstuffs

Background document for the Stockholm Hearing, 17-18 February 2000,

Background document for the Stockholm Hearing, 17-18 February 2000,

Background document for the Stockholm Hearing, 17-18 February 2000,

Background document for the Stockholm Hearing, 17-18 February 2000,

Background document for the Stockholm Hearing, 17-18 February 2000,

Green Purchasing of Foodstuffs

Green Purchasing of Foodstuffs

Green Purchasing of Foodstuffs

Green Purchasing of Foodstuffs

Green Purchasing of Foodstuffs

arranged by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency

arranged by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency

arranged by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency

arranged by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency

arranged by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency

and the European Green Purchasing Network

and the European Green Purchasing Network

and the European Green Purchasing Network

and the European Green Purchasing Network

and the European Green Purchasing Network

Final report

Final report

Final report

Final report

Final report

Nav Brah Ferd Schelleman

Grontmij Water and Waste Management, Department for Environmental Management

De Bilt, Netherlands Tel: 0031 30 6943210

Green Purchasing of

Foodstuffs

FOREWORD

On February 17-18, 2000 an international hearing in Stockholm about “Green

purchasing of foodstuffs” was arranged by the Swedish Environmental Protection

Agency and the European Green Purchasing Network. A specific background

document was written as a basis for the discussions at the hearing. The document

presents the food supply chain, environmental problems in the food sector, some of the

key issues, which must be dealt with in order to progress the European agrifood chain

towards sustainability.

This report is based on this background document as well as the conclusions of the

hearing.

Nav Brah and Ferd Schelleman at Grontmij Water and Waste Management in the

Netherlands have written the report and Ingrid Jedvall at the Swedish Environmental

Protection Agency has been the project leader for this project.

The authors are responsible for the contents of the report. Consequently, it is not

necessarily the views of the Swedish Environmental Agency that are expressed.

STOCKHOLM IN AUGUST, 2000

Contents:

1.0 Introduction... 3

2.0 Sustainable Development Drivers in the EU ... 3

The 1992 Rio Declaration and Agenda 21... 3

EU Initiatives ... 4

Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) - Agenda 2000 ... 5

3.0 Key Stakeholders in Agri-food Chains... 6

Farmers... 7

Food Processors ... 7

Retailers ... 7

Consumers... 7

Governments and Institutions ... 10

Education and Research Organisations... 10

Non Government Organisations (NGO) ... 11

4.0 Environmental Aspects of Agri-food Chains... 11

Farmers... 11

Food Processors ... 13

Retailers and Distributers... 15

Consumers... 16

5.0 European Trends towards Sustainability ... 18

6.0 Sustainable Agri-Food Regulation and Eco-Labelling... 18

Emergence of National Standards and Regulation ... 19

EC Regulation ... 19

7.0 Green Procurement Challenges ... 19

Corporate Green Purchasing Policies ... 20

Use of Eco-Labels... 21

8.0 International Trade Issues... 22

9.0 Conclusions and recommendations from the Hearing... 24

Conclusions... 25

Environmental Issues: ... 25

Information dissemination:... 25

Co-operation between stakeholders: ... 25

Developments and initiatives: ... 25

Follow-up and further work ... 26

Summary of conclusions and recommendations... 27

1.0

Introduction

Agri-food chains represent a complex network of inputs and outputs that link farm production inputs to food consumers. They involve an extensive range of stakeholders. The agri-food sector comprises a wide range of industries, which provide agricultural inputs, process farm produce into a variety of food products and distribute food products to consumers. It is a major contributor to national gross domestic product, international trade, public health and welfare, and therefore, has great political and economic importance.

The European Union (EU) is the largest agri-food products market in the world. Agri-food trade was estimated at US $200 billion in 1993. There is also a great diversity of agricultural-producing regions in the EU - from Lapland in northern Finland to Andalusia in southern Spain. The European agri-food chain is very productive. High agricultural yields and a high diversity of agri-food products typify the agri-food chain in the EU. Technology, scientific progress, intensive production and European Commission policies have underpinned its performance. However, sustainability of the agri-food chain system is now questioned because of wide scale degradation of soil fertility, water resources, bio-diversity and energy resources. Furthermore, the European agri-food sector has substantial socio-economic and environmental impacts outside the European Union (EU) through its dependence on feedstocks and raw materials from developing nations. Many developing countries rely on exports to the EU as the main source of export revenues and foreign exchange. As the world’s population increases by more than 50 per cent over the next 20 years, to eight billion, there is a pressing need to significantly improve sustainability of the agri-food sector.

This paper briefly considers some of the key issues which must be dealt with in order to progress the European agri-food chain towards sustainability. It presents EU drivers for sustainability in the sector, the main agri-food chain stakeholders, general environmental aspects of the sector, trends towards sustainable food production, environmental labelling, green purchasing, institutional instruments to promote sustainable practices and international trade concerns.

2.0

Sustainable Development Drivers in the EU

The 1992 Rio Declaration and Agenda 21

Following the 1992 Rio Declaration, Agenda 21 was formulated to identify ways of applying

sustainable development policies in various areas, including conservation and resource management. Agenda 21 sets out two basic objectives regarding consumption and production;

• Promotion of sustainable consumption and production patterns; and

• Developing a better understanding of the role of consumption and how to bring about more sustainable consumption patterns.

In response to Agenda 21, the United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development, the OECD and National governments proposed action programmes for:

• Pricing reforms to internalise environmental costs including phasing out of subsidies that promote unsustainable consumption;

• Green public procurement policies;

• Extending producer responsibility for life-cycle environmental impacts of products and services; and

• Introducing Eco-labelling to promote environmentally preferable products.

The World Business Council for Sustainable Development, representing 120 international companies and 20 major industry sectors, has sustainable production and consumption as one of its key policy areas. It has highlighted the economic and environmental benefits of Eco-efficient product

management to companies, in terms of operations and public reputation.

EU Initiatives

The fifth EU Action Programme on the Environment and Sustainable Development stipulates practical measures to achieve sustainable production and consumption. It states:

"The flow of substances through the various stages of processing, consumption and use should be so managed as to facilitate or encourage optimum reuse and recycling, thereby avoiding wastage and preventing depletion of natural resource stock: production and consumption of energy should be rationalised; and consumption and behaviour patterns of society should be altered."

Within the EU sustainable development initiatives are being translated into national government policies. The Netherlands has one of the most comprehensive policy approaches within the EU. The National Environmental Policy Plan developed a policy on Product and the Environment where it states the goal to "create a situation in which market players producers, traders and consumers -continually strive to reduce the environmental burden of products".

The treaty, which established the European Economic Community explicitly, requires development and implementation of a Community policy on the environment. The Maastricht Treaty specifies promotion of sustainable growth that respects the environment as one of its key objectives. In 1990 the EU Declaration of Heads of State and Government called for a further action programme for sustainable development. It emphasised the need for policies and strategies for continued economic and social development without adverse impacts on the environment and natural resources needed for human activity.

Despite adoption of this legislation, the state of the environment published in 1992 highlighted further environmental degradation. It described particular environmental problems relevant to the agri-food sector, such as:

• increased aquatic pollution from non-point sources (especially agriculture) which threatened water quality, eutrophication of fresh waters and pollution of marine waters;

• increased soil degradation from increased spreading of nitrates and sewage sludge in agriculture, greater use of hyper-intensive farming techniques, overuse of chemical fertilisers, pesticides and herbicides, acidification and dessertification in particular areas; and

• threats to biota and their natural habitats and reduced bio-diversity.

The current fifth European Commission environment programme, which lasts until the year 2000, aims to transform patterns of growth to promote sustainable development and to form new

relationships between stakeholders in the environmental sector. It sets out a new approach to Community environmental policy based on:

• adoption of a global, proactive approach aimed at different actors and activities which affect natural resources or environmental pollution;

• the will to modify trends and practices which harm the environment for current and future generations;

• changing social behaviour by engaging relevant stakeholders (public authorities, citizens, consumers, enterprises, etc.);

• establishing shared responsibility; and • using new environmental instruments.

Priority action areas have been identified which must be tackled at Community level due to their impact on operation of the internal market, cross-border relations, sharing of resources and cohesion. Those particularly relevant to the agri-food sector are:

• long-term management of natural resources: soil, water, countryside;

• an integrated approach to combating pollution and acting to prevent waste; and

• improving mobility management and developing efficient and clean modes of transport. A new 6th Environmental Action Program is under development, which aims to become the environmental dimension within the strategy for sustainable development. This program will be legally binding and will be a basis for the environmental integration into all sectors according to the Amsterdam Treaty.

Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) - Agenda 2000

CAP has been one of the driving forces in the development of the present intensive agriculture that nowadays leads to environmental problems and the depletion of bio-diversity. However, the knowledge of this has resulted in a new approach in Agenda 2000. The purpose of the CAP reform agenda 2000 for beyond the year 2000 includes, inter alia, assurance of food safety and quality and integration of environmental considerations into agriculture policy.

CAP Agenda 2000 promotes environmental considerations and preservation of the countryside and bio-diversity. In general, it requires farmers to observe a minimum level of environmental practice and to be compensated by specially tailored agri-environmental programmes for additional initiatives beyond the basic level of good agricultural practice and respecting environmental law.

Proposed agri-environment measures include linked payments to farmers for use of agricultural land which is compatible with protection and improvement of the environment, landscape features, natural resources, soil and genetic resources. The CAP Agenda 2000 is one the largest regional funding initiatives within the EU.

3.0

Key Stakeholders in Agri-food Chains

The agri-food sector is a dynamic sector with a variety of stakeholders involved in the links between supply of farm inputs, farming, manufacturing and processing of diverse food products, packaging, transport, distribution and consumers.

At a macro-scale the chain’s principal links include agricultural activities, food processing, distribution and consumption. A micro-scale analyses reveals involvement of a number of other players namely, feedstock suppliers; agro-chemical manufacturers and suppliers; machinery and equipment manufacturers and suppliers; petroleum manufacturers and suppliers; farmers; produce marketers and sellers; food processors; suppliers of food additives; packaging suppliers; transport companies; food retailers; consumers; and waste processors. Government legal and regulatory requirements exert an influence in virtually every link of the agri-food chain.

Table 1 depicts principal stakeholders in the agri-food chain.

Table 1 PRINCIPAL AGRI-FOOD CHAIN STAKEHOLDERS IN VARIOUS SECTORS

Agri-food chain link

Dairy Products Cereal Products Fruit &Vegetables Meat Products Farm suppliers inputs livestock feed providers; fertiliser, pesticide, veterinary & agro-chemical manufacturers seed providers; fertiliser, pesticide & agro-chemical manufacturers seed providers; fertiliser, pesticide & agro-chemical manufacturers livestock feed providers; fertiliser, pesticides, veterinary & agro-chemical manufacturers

Farmers livestock breeding seed growers horticultural production animal husbandry Food Processors & packagers dairy product manufacture: milk, yoghurt, ice-cream, powder milk, etc.

grain millers, bakeries, pasta manufacturers, breakfast cereal manufacturers canned, de-hydrated and frozen vegetable based packaged convenience foods manufacturers abattoirs; butchers; canned, hydrated and frozen packaged meat based convenience foods manufacturers

Retailers milkmen, super markets, grocery shops bakeries, supermarkets, grocery shops supermarkets, fresh fruit & vegetable markets, green grocers, grocery shops

butcheries, supermarkets

Consumers single to family households with various age groups, lifestyles, cultures, preferences, incomes

Farmers

Typically farmers belong to small-scale independent family operations or are members of a co-operative. The farm sector structure is changing as some farmers co-operate to benefit from economies of scale through cheaper purchases of inputs and access to modern technologies while others combine farming with other income generating activities, such as tourism. Increasingly, EU farmers are beginning to feel pressure from large food processors and retailers who require better agricultural practices in relation to food hygiene and safety, animal welfare, use of agri-chemicals and better management of natural resources.

In most EU countries, over 95 per cent of the agricultural area is farmed using conventional farming methods. However, over the last decade the rate of sustainable farming has grown, especially in Northern European countries. This is evidenced by the rapid growth of organic farming and in-conversion land area in Western Europe from just over 100,000 hectares in 1985 to more than two million hectares in 1998, a 20 fold increase in land area used for sustainable agriculture. Although organic agriculture still only represents less than two per cent of farmland in Europe, its market share in some countries is becoming significant. Already, in Austria, Germany, Finland, Sweden and Switzerland about 10 per cent of farmland now employs organic methods.

Food Processors

A large diversity of small, medium, large as well as large multi-national companies process a great variety of foods products. There is an emerging tendency for consolidation amongst processors to deal with the market power of retailers and emerging global competition (Euromonitor, 1994 as cited in Schelleman, 1996). Industry concentration gives processors great market power to specify food requirements to producers.

Retailers

There are a couple of hundred retail chains in Europe as well as many small independent retailers. Consolidation is also a trend occurring in this sector. Multiple retailers who build their own labels often dictate the food market. A few big retailers control some 30 per cent of the retail market in Northern Europe. Dominance of the agri-food sector by big retailers gives them greater leverage in specifying food requirements to food processors and producers.

In November 1999, leading European retailers who are members of EUREP, the Euro-Retailer Produce Working Group for fruit and vegetables, launched their Good Agriculture Practice (GAP) Verification 2000. The leading retailers include major European food retailing companies such as Albert Heijn, Safeway, Sainsbury, Tesco, etc. The guide has been designed to meet consumer concerns about food safety, environment and worker welfare issues. It defines current agricultural best practice and defines minimum standards acceptable to leading retail groups in Europe. Refer to box 1.

Many of the leading European retailers now offer their customers a range of organic food products and even actively promote organic foods on the Internet web-sites.

Consumers

The EU consumer market is stagnating due to slow population growth. This means that growth in food demand is low. Consumers increasingly comprise aged persons with special dietary needs and single person households which prefer processed and convenience foods. Trends also indicate a greater tendency to snack. Such changes to consumer preference results in more processed and packaged food products.

There is increasing awareness of health and nutritional aspects of food related to cholesterol, calories, food additives, pesticides, organic products, etc. These are causing in an increasing number of retailers to cater for health conscious consumers and putting pressure further up the agri-food chain to influence processors and farmers.

Box 1: EUREP Good Agricultural Practice Standards

The Euro Retailer Group (EUREP) represents leading European Food retailers who have agreed to promote Good Agricultural Practice (GAP) standards in response to growing consumer interest on the impact of agriculture on food safety and the environment. The GAP standards are the minimum acceptable requirements for leading European retail groups. They set out key elements of best practice global production of horticultural products. GAP standards require growers to demonstrate commitment to:

• Food quality and safety;

• Minimising environmental impacts;

• Reducing agri-chemical use by adopting integrated production systems; • Efficient use of natural resources; and

• Worker occupational health and safety.

Growers receive EUREP GAP approval through independent verification from an approved Certification body. The standard sets out framework requirements for:

• Choice of rootstock variety, seed quality and nursery stock and their treatment; • Management of Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs);

• Soil Management;

• Fertiliser use and management; • Irrigation management;

• Crop Protection using Integrated Pest and Crop Management systems; • Pesticide management;

• Harvesting and post-harvesting treatments;

• Waste and pollution management;

• Occupational health and safety management;

• Environmental impact assessment and conservation;

• Maintenance of verifiable records to demonstrate compliance to GAP; and • Site management of agronomic activities.

Governments and Institutions

Governments and institutions develop key policy instruments that impact on the agri-food chain. In the European context the key bodies are:

• The European Union Commission, which formulates directives and regulations that, must be transposed into national policies and legislation by member governments. Important policies, directives and regulations relating to the agri-food sector sustainability include inter alia: the fifth Environmental Action Programme; CAP; Amsterdam Treaty; regulation on organic agricultural production; directives on Habitats and Wild Birds; legislation on water protection; the directive on Nitrates; regulation on food labelling; directive on packaging and packaging waste; directive on integrated pollution prevention control (IPPC); regulation on the Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS); and regulations on food quality, health and safety;

• National Governments, who transpose, implement, regulate and enforce EU directives and regulations into their domestic institutional and administrative frameworks. Governments also play a vital role through use of economic instruments such as taxes and subsidies to facilitate industry policy in line with government, public and market expectations;

• The World Trade Organisation (WTO) which provides the legal and institutional basis for multilateral trade and trade liberalisation. It provides the key contractual obligations that

determine how governments frame and implement domestic trade legislation and regulations. EU policies, legislation and regulations related to the agri-food that have trade implications, such as environmental labelling, environmental taxes on food products, green procurement, etc., must comply with WTO multilateral agreements. EU and government initiatives, which may be construed as technical barriers to trade by countries seeking to export agri-food products to the EU, may be challenged and arbitrated in the WTO.

• Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) and World Health Organisation (WHO) impact on the international agri-food sector through the establishment of international standards for food safety and quality, in the Codex Alimentarius. The Codex general standards specify inter alia

requirements for food labelling, food additives, contaminants, methods of analysis and sampling, food hygiene, nutrition and foods for special dietary uses, food import and export inspection and certification systems, residues of veterinary drugs in foods and pesticide residues in foods. These standards provide a framework for harmonising international food standards

• International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) is an international umbrella organisation of the organic agriculture movement. Its membership comprises over 700 member organisations in over 100 countries. As well as organic farmer associations, its membership also includes food, processors, traders, consumer and environmental organisations. IFOAM has developed internationally applied standards, which reflect the current state of organic production and processing methods. The standards provide a framework for certification programs

worldwide. Producers and processors selling organic products to the market using an organic label are generally certified by national or regional organic certification schemes according to IFOAM basic standards. Many of the EU national organic certification schemes for farmers and

processors have been accredited by IFOAM. The EU regulation on organic production of agricultural products and foodstuffs is also largely based on IFOAM standards.

Education and Research Organisations

Education and research institutions play a critical role in providing knowledge for advancement of sustainable agri-food chain productivity, efficiency and identification of environmental impacts and their prevention and control. There is a wide range of multi-disciplinary research organisations who

Non Government Organisations (NGO)

Many NGO organisations are interested in consumer awareness, public health, animal welfare and environmental issues pertaining to the agri-food industry. A number of these organisations actively campaign on specific issues such as irradiated food products, genetically modified organisms (GMO), pesticides in food, bio-diversity, water pollution by agro-chemicals, etc. They are often very well organised and politically active lobby groups with significant scientific resources. NGOs are

increasingly assuming a de facto "watch dog" role in monitoring aspects of the agri-food industry and often bring relevant issues into the public domain.

4.0

Environmental Aspects of Agri-food Chains

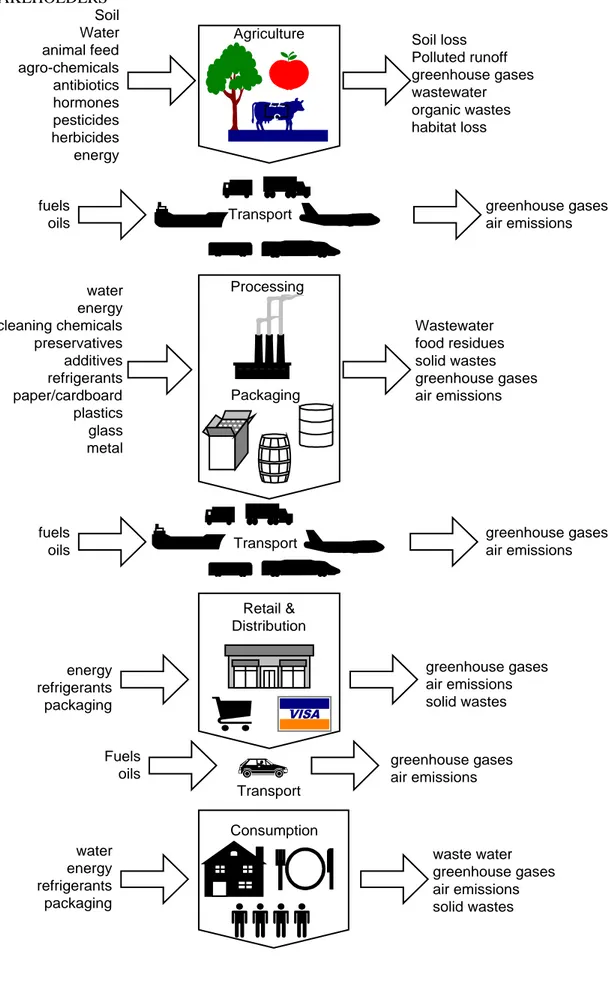

Environmental impacts associated with food production and consumption are a function of population, food availability per capita and efficiency of material use such as energy, pollution releases, etc (Hoor, 1993 cited in Schelleman, 1996). Food demand in the EU is reportedly stagnating. Growth in consumption was reportedly only two per cent between 1989 to 1995 (Euromonitor, 1994, cited in Schelleman, 1996). Hence, the sustainable development challenge for the EU agri-food sector is to de-couple high productivity and associated degradation of natural resources through adoption of cleaner processes and technologies, efficient use of input materials and preservation and enhancement of bio-diversity. Environmental aspects of agri-food chains for the principal stakeholders are discussed below. Figure 1 provides an overview of key environmental aspects of principal stakeholders in the agri-food chain. It clearly illustrates the wide spread

environmental impact of transport in the agri-food chain. Road transport by trucks is a major form of conveyance within the agri-food chain, from delivery of farm inputs, to processing and to retail and distribution. Interestingly, an assessment of greenhouse gas emissions within the German agri-food sector revealed that processing, trade and transport and crop production were relatively small contributors to emissions when compared to animal husbandry and household consumption (Meier-Ploeger, 1996)

Farmers

Arable land is one of our most valuable natural resources. It is needed in order to provide future generations with food, contribute to national energy supply, and provide habitat for a rich plant and animal life. The agriculture of today is efficient and produces food of a high quality. Agriculture affects the environment in many ways, for example through the release of nitrogen and changes in the range and composition of biological diversity. Agriculture is a key component of the cyclic process by which food, nutrients, energy, and raw materials flow between city and countryside. Vital and

resource-efficient agriculture is a precondition of a vital and resource-efficient society. Farmers play a central role in the management of arable land, and their choice of methods has a decisive impact on the land’s future fertility.

Farming is the primary source of groundwater nutrient pollution, especially pollution with nitrate infiltration from excessive manure and fertiliser applications. Ground water in over two thirds of EU member states exceed EC Drinking Water nitrate standard of 25 milligrams per Litre (RIVM/RIZA, 1991 cited in Schelleman, 1996).

Figure 1 ENVIRONMENTAL ASPECTS OF PRINCIPAL AGRI-FOOD CHAIN STAKEHOLDERS Agriculture Processing ££ £ Packaging Transport Transport Transport Retail & Distribution Consumption Soil Water animal feed agro-chemicals antibiotics hormones pesticides herbicides energy Soil loss Polluted runoff greenhouse gases wastewater organic wastes habitat loss water energy cleaning chemicals preservatives additives refrigerants paper/cardboard plastics glass metal Wastewater food residues solid wastes greenhouse gases air emissions fuels oils greenhouse gases air emissions fuels oils greenhouse gases air emissions energy refrigerants packaging greenhouse gases air emissions solid wastes water energy refrigerants packaging waste water greenhouse gases air emissions solid wastes Fuels oils greenhouse gases air emissions

Aquatic pollution of receiving waters is also occurring due to agricultural runoff containing pesticides and nutrients, mainly phosphorus and nitrogen. Nutrient enrichment of receiving waters downstream of agricultural land often makes a significant contribution to eutrophication and algae blooms which can severely limit beneficial use of waters for maintaining aquatic ecosystems, drinking,

stockwatering, or recreation. It is interesting to note that although fertiliser usage has tripled in the last few decades, only a small fraction of the nutrients are effectively taken up by plants with the remainder entering the environment.

High pesticide residues in agricultural soils and in receiving water bodies due to wide agricultural use is also a wide spread problem. It is has been estimated that about two thirds of EU Agricultural land exceeds limits for residual pesticide concentration. Use of broad-spectrum pesticides often impacts non-target plants and insects, which diminishes bio-diversity. Furthermore, emergence of weed and insect resistance to pesticides after continual use over time further exacerbates loss of bio-diversity. Agricultural soils have also been found to contain excessive heavy metal concentrations associated with use of phosphate fertilisers (Smith, 1995 cited in Schelleman, 1996).

Farming also contributes directly to air emissions. Atmospheric releases include methane from intensive animal husbandry and livestock in general; ammonia and nitrogen oxides from nitrogenous fertilisers and livestock wastes; and carbon, nitrogen and sulphur oxides from fossil fuel use.

Loss of bio-diversity and species habitats is another key adverse effect of agricultural activities. Threats to of bio-diversity result from physical fragmentation of natural landscapes and aquatic habitats by farmland which reduces habitat areas necessary for maintaining and sustaining natural plant and animal species. Species loss, especially of particular bird and insects, reduces natural on-farm pest control capacity. Mono-cultural on-farming systems also diminish bio-diversity by promoting dominance of specific plants and insects that can successfully co-exist with particular crops.

Emergence of genetically modified crop varieties with in-built pest resistance also pose potential threats to bio-diversity as natural selection processes result in gradual resistance development amongst target pests.

Indirectly, suppliers of agricultural inputs such as agri-chemicals, feedstock and electricity also cause environmental impacts through their production and processing activities. For example, Life cycle analyses (LCA) studies in the dairy product chain concluded that suppliers of feedstock and fertiliser were the main energy users (ATV, 1995 cited in Schelleman, 1996).

Furthermore, because EU agriculture is dependent on imported inputs. This also indirectly leads to environmental impacts in the exporting countries supplying the European agri-food sector. For example, European intensive animal production uses tapioca and soya animal feedstock from developing countries in south East Asia and Latin America. Between 1965 and 1985, Brazil expanded its soya farming land from less than half a million hectares to about 9.6 million hectares. This expansion consequently caused considerable pollution of receiving waters draining the soya farmlands with sediments and pesticide residues (Amstel, 1987 cited in Schelleman, 1996)

Food Processors

Key environmental aspects relevant to the food processing and manufacturing sector include energy use, discharge of high strength effluents, localised odour problems, fugitive air emissions; chemical use and chemical storage and handling. Energy use in various food preparation, cooking, heat treatment and refrigeration applications contributes to greenhouse gas emissions such as carbon, nitrogen and sulphur oxides.

Large quantities of wastewater are generated mainly from cooking processes, cooling waters from heat exchangers and in process vat cleaning processes. Wastewater streams typically contain high

strength organic wastes and nutrients associated with product losses and rinse water streams. The polluting strength of untreated wastewater from large food processing facilities can often be equivalent to a small town or village due to concentrated organic wastes. Discharge of process wastewater can significantly pollute receiving waters unless prior secondary or tertiary treatment is provided.

Food processing companies in the vicinity of residential areas often cause odour problems due to atmospheric venting of cooking and preparation gases. Other air emission problems can arise from fugitive releases of refrigerant gases such as ammonia.

Many foods processing facilities, like other industry types, will also typically have bulk storage depots for fuels, oils, lubricants, acids, caustics and other process chemicals. Accidental spills, container leaks and poor housekeeping in such areas can pollute the environment through land contamination, vapour releases and releases to receiving water bodies via entry into stormwater drains.

Sustainability in the Food Industry

SAM (Sustainable Asset Management) a Swiss based asset management company analysed the aspects, which are crucial to the food industry and evaluated the strategy of the largest food

manufacturers in terms of a “sustainable food industry” scenario. The following sustainability aspects were used:

• Product portfolio

• Efficient use of Resources

• Product information and communication • Sustainability-related risks

• Sustainability management • Quality control

SAM gave 15 food manufacturers a Sustainability Rating with the following results for the leading, most sustainable companies:

Company Rating Explanation

Unilever A-1-1 Unilever encourages sustainable farming, water saving in production, processing and consumption. Unilever also cooperates with WWF to form the Marine Stewardship Council.

Raisio A-2-2 Raisio does not apply GMO materials in its products, uses largely locally produced products, develops environmentally sound transport systems and has successfully reduced energy consumption.

The study identified a number of pioneers (smaller companies) who are also dealing with sustainability strategy development and have showed important progress in this field.

Individual companies have made significant progress towards sustainable development. During the Agri-Food Hearing Unilever Sweden presented the main goals and initiatives of Unilever Sweden (see box below).

Retailers and Distributors

Direct environmental aspects associated with the retail and distribution business are considered to be relatively less relevant than agricultural production and food processing. However, retail businesses are the direct interface between agri-food products and consumers and are therefore in a key position to influence upstream food production and downstream consumption. This is a pivotal role since most environmental impacts result from production and consumption activities.

Key environmental aspects directly associated with retailers' services are energy use and packaging. Energy use is associated with fuel use by distribution fleets, warehousing and food refrigeration. The trend towards fewer and larger retail outlets with centralised warehousing is aimed at increasing economies of scale, improving logistical efficiency and optimising transport distances, which will improve energy efficiency.

Food and beverage packaging is also a major environmental aspect for EU retailers due to limitation of solid waste land filling. Retailers are often instrumental in specifying packaging requirements for various food and beverage products and therefore impact on the amount of packaging waste entering the consumer market and eventually the environment and landfills. However, polluter pays policies within the EU are resulting in use of recyclable packaging materials and gradual implementation of packaging recovery by retailers.

UNILEVER

Sustainable Agriculture Initiative

Objective: Ensure the continued availability of Unilever’s key crops by defining and adopting sustainable agriculture practices in the supply chain.

The Major phases:

1. Understand challenges and opportunities: stakeholder perceptions, sustainable agriculture and definition of standards.

2. Source key crops from sustainable agriculture: adopt sustainable agriculture standards in the supply chain and use these sources as much as possible.

3. Develop market mechanisms for sustainability customer and consumer support and influence their behaviour.

The guide the implementation a set of ecological, economic and social indicators was developed in close consultation with stakeholders from around the world.

A Sustainable Agriculture Steering Group was adopted in 1998 which uses an approach supporting the following principles:

• Maintaining high yields and nutritional quality with as low as possible inputs; • Minimise adverse effects on soil, water and air;

• Optimise use of renewable resources whilst minimising the use of non-renewable resources; • Enabling local communities to protect and improve their well-being and environments. Pilot projects cover five strategic crops: Peas, spinach, tea, palm oil and tomatoes.

Retailers influence farming and food processing as well as consumer awareness and practices. It is often claimed by the organic farmers that retail requirements for uniform size and quality and appearance of farm products promotes unsustainable agricultural practices through excessive use of agro-chemicals and loss of bio-diversity through genetically modified hybrids.

However, a number of big retailers now offer and actively promote a wide variety of sustainably produced agri-food products such as fresh organic fruits and vegetables, organic meats, organic dairy products, free-range eggs, baby foods, fruit juices, cereals, etc. The market strength and position of retailers places them in a position of considerable influence from which to improve sustainability of agricultural practices and food processing. As indicated earlier, the EUREP GAP verification

protocol is an important first step by retailers to promote more sustainable agriculture by encouraging farmers to adopt integrated crop and pest management, ensure animal welfare and control inputs such as agri-chemicals and irrigation water to avoid excessive applications.

ICA, one of Swedish largest food retailer companies, presented its environmental programme at the Hearing. A summary of their activities is presented in the box below.

Consumers

Consumers of agri-food products have wide ranging environmental aspects related to food purchasing, preparation, dishwashing and management of food and packaging wastes.

Significant amounts of energy are used by households using cars for shopping, refrigerators and freezers, cooking appliances and washing dishes with hot water or dishwashing appliances. The fuel and electricity used to cook or preserve food in turn contributes to greenhouse gas and other

emissions.

ICA Handlarna AB

ICA contributed to the development of the EUREP Good Agriculture Practice protocol as presented earlier in this document.

ICA envisages becoming one of Swedish best and leading, most inspirational and enduring retail companies with the focus on meals, enduring in the sense of not only being economically and ecologically sustainable, but socially attractive as well.

In ICA´s environmental programme the following topics can be distinguished:

• The Stores: ICA stores will improve environmental performance through a wide range of eco-labelled products, good environmental information and customer activities. ICA developed the concept of Environmental Stores and now has more than 100 such stores.

• Waste and Energy: Stores must reduce their impacts on the environment by using fewer resources, sorting waste products at source and reduce its energy consumption. 85% of the stores have now replaced their hard-CFCs in refrigeration and freezer units.

• The Product Range: The objective is to offer a product range which imposes the minimum possible burden on the environment, viewed over the entire life-cycle, from raw material to final usage and disposal.

• Transportation: ICA wants to increase the efficiency of transportation systems, using railway for long-distance transports and running trucks on alternative fuels.

• Farmers and Suppliers: ICA imposes environmental demands on its products and on its suppliers. In this respect ICA participates in the EUREP GAP initiative.

ICA works on implementing the ISO 14001 environmental management approach in all ICA Handlarnas companies. All companies should be certified or ready for certification by the end of the year 2000.

Significant quantities of potable water are used in food preparation, cooking and washing dishes and utensils. Consequently, kitchen wastewaters contain diluted food products, nutrients, organic material and detergents, including phosphates. Typically, kitchen wastewaters are discharged directly into the municipal sewerage system along with higher strength wastewaters from toilet flushing. They contribute to waste loads which need to be treated by municipal sewage treatment facilities and/or be discharged to receiving waters where they affect water quality.

Food wastes, from preparation and left over meals and food packaging, comprise a major component of municipal solid waste. Currently, the majority of organic and packaging household wastes are landfilled or incinerated in municipal solid waste treatment facilities. Landfilling in the EU is now considered unsustainable as it poses long term contingent environmental problems. Incineration, is often unpalatable to local communities because of potentially hazardous dioxin and volatile organics emissions which impact on local communities.

Catering companies have an increasing market share in food supply and thus the environmental impact of these activities is more and more important. Already there is an increasing number of catering companies implementing environmental management systems and applying biological food produce. An example of such a catering company is Sodexho.

SODEXHO

Sodexho is a France based company with activities in different European countries, North- and South America, Africa and Asia. In Belgium Sodexho has 3.500 employees, 550 operating units and a turnover of 7,5 billion BEF (Euro 375 million).

Sodexho has developed and implemented an environmental improvement programme focusing on waste prevention. Results are made visible through a set of environmental performance indicators. An example of the activities and indicators for some environmental topics is presented in the scheme below.

Areas

Actions

Indicators

Waste

1. Sort the waste if it is profitable 2. Make the personnel awareNumber of different containers and periodic costs for the collection of waste.

Water

1. Verify the defective taps 2. Make the personnel aware 3. Search for the leaksMonthly consumption statement to be compared every period.

Electricity

1. Switch of the lights if not necessary 2. Progressively turn on the cookers 3. Put a lid on the waterpan4. Close the door of the refrigerator, etc..

Monthly consumption statement to be compared every period.

Gas

1. Put a lid on the waterpan2. Make the personnel awareMonthly consumption statement to be compared every period.

5.0

European Trends towards Sustainability

Recognition of the need for sustainable food production in harmony with the environment was evident in Europe in the 1920s. The focus of sustainability was primarily on the agricultural chain as farmers noticed that current conventional farming methods resulted in declining soil fertility, poor seed viability and poor animal health. In the mid to late 1920s, the emergence of "bio-dynamic" organic agriculture according to the principles of Rudolph Steiner founded the basis of sustainable organic agriculture. His approach to sustainable agriculture relied on working with natural ecosystems and forces rather than opposing them. Bio-dynamic agriculture relies on an appropriate mix of crops and livestock to promote internal recycling and relies on benign pest and disease controls. It aims to develop a self reliant farming system.

Rudolph Steiner bio-dynamic certification standards were the first organic farming standards to be produced as early as 1928. Strict bio-dynamic certification standards carry the Demeter logo. The Demeter certification logo ensures that bio-dynamic produce is universally accepted as genuinely organic. Other proponents of sustainable organic-biological techniques emerged elsewhere in Europe in the 1940s, such as the BIO Gemüse AVG in Switzerland, Bioland in Germany and the Soil

Association in Britain.

The key principles of organic-biological farming include:

• Protection of long-term soil fertility by maintaining organic matter, promoting biological activity and careful mechanical intervention;

• Use of insoluble nutrients sources which are made available to crops through the action of micro-organisms;

• Use of legumes for biological nitrogen fixation to achieve nitrogen sufficiency; • Recycling organic matter using crop residues and livestock wastes;

• Use of crop rotations, natural predators, biological diversity, resistant crop varieties and limited thermal, biological and chemical methods to control weeds, disease and pests;

• Extensive livestock management and regard for animal welfare, natural evolutionary adoption and behaviour issues by paying attention to diet, health, shelter and breeding; and

• Control of environmental impacts and conservation of natural habitats.

(adapted from Lampkin and Padel, 1994)

6.0

Sustainable Agri-Food Regulation and Eco-Labelling

Between the 1970 and 1980, as green consciousness and later green consumerism grew, voluntary self-regulatory organic symbol schemes were set up for food products. The schemes were

underpinned by specific organic-biological standards. The schemes and standards included the emergence of Nature at Progrès in France in 1972, the Soil Association in Britain in 1973, Bioland in Germany in 1978. In addition, retail outlets for the product began emerging to satisfy growing consumer demand.

Emergence of National Standards and Regulation

After 1980, organic production gained increasing acceptance and national standards were established in a number of European countries. Proliferation of standards and voluntary certification schemes caused consumer confusion and uncertainty. To tackle this issue, national standards and certification emerged in a number of EU states.

In France, the AB (Agriculture Biologique) symbol for organic cereals, fruits and vegetables emerged. In 1988, the French government introduced national basic standards for organic produce and outlawed use of non-approved standards. Britain followed France with its national United Kingdom Register of Organic Food Standards (UKROFS). UKROFS has an official set of organic standards for arable and livestock production, horticulture and processing of organic products. Voluntary schemes need to be registered with UKROFS as organic sector bodies. The national standards ensure that self-regulating organic schemes are certified by a national body e.g. In Britain, the Soil Association is registered with UKROFS. The voluntary certification schemes have to match national standards as a minimum in order to be able to use the certification mark of the national scheme. Compliance of voluntary certification schemes is regularly verified against the national standards and registers of compliant voluntary schemes are maintained for consumer information.

EC Regulation

In 1991, the EU enacted regulation 2092/91/EEC on organic production of agricultural products and foodstuffs, which applies to all Member States. It regulates organic food labelling in the EU.

Member State authorities just like any other national statutory law enforce the regulation. Initially, it covered plant products or mixed products comprising a larger portion of plant constituents. Later, it was amended to include livestock products. Regulation 2092 orders not to use or apply any other substances in organic agricultural production other than those specified in "positive lists" that form part of the law. The lists promote traditional and mainly natural crop protection agents and fertilisers and prohibit use of organo-synthetic pesticides and synthetic nitrogen fertilisers. Production,

processing, monitoring, documentation and inspection methods are detailed in the regulation. The regulation prohibits use of genetically engineered organisms in organic food processing (Karlsruhe, 1996)

Since 1993, all organic-biological fresh and processed food has to comply with the organic standards specified in the regulation. Member countries have to appoint a Designated Inspection Authority (DIA) to implement and enforce the scheme either alone or in conjunction with approved organic certifying bodies. In Britain, the previously voluntary scheme of UKROFS is now compulsory, with UKROFS as the DIA (Lampkin and Padel, 1994). Other Member States have established bodies to be DIA specifically to comply with the regulation.

The regulation also affects imports of organic foods to the EU. Organic imports must be from a country on the EU approved organic source list. Countries on the list must conform to the EU organic production rules and need equivalent inspection measures. Local inspection bodies must issue

inspection certificates to accompany produce entering the EU

7.0

Green Procurement Challenges

Agri-food chain purchasing managers and officers are key personnel for advancing environmentally conscious patterns of business conduct within their organisations. They occupy a strategic position regarding environmental concerns within their organisation and towards other organisations. Purchasing departments are facilitators between an organisation's needs and suppliers. Their responsibilities cover:

• Managing stock and assessing cost; • Managing flow of incoming products; • Specifying products and potential suppliers; • Selection of appropriate suppliers;

• Communicating with other organisational areas in determining and specifying product needs; • Undertaking actual purchasing transactions; and

• Working with suppliers to form reliable business relationships.

Implementing green purchasing requires bridging two disparate worlds: purchasing and environment. Product functionality, reliability and quality primarily drive purchasing within the agri-food sector, as in any business, at the most competitive market price. This holds for procurement of agro-chemicals by farmers, bulk buying of produce by processors, purchase of processed foodstuffs and farm produce by retailers or supermarket shoppers. However, environmentally conscious purchasers within the agri-food chain can make a significant contribution to minimising environmental aspects by carefully evaluating their functionality and quality requirements, opting for environmentally preferable

alternatives and using them consciously. Purchasers and consumers can send strong market signals through environmentally conscious buying and consumption. Prerequisites for purchasers to influence greener procurement are to:

• Develop an understanding of environmental issues associated with products needed by the organisation;

• Collect environmentally-relevant product data from suppliers, scientific research and other sources; and

• Monitor and anticipate emerging environmental issues and policies that could affect the organisation.

Corporate Green Purchasing Policies

Agri-food chain industries and companies should consider developing green-purchasing policies for procurement of goods and services, preferably as a component of an overall environmental corporate driven policy. Such policies would be particularly relevant to food processors and retailers who have significant market strength as purchasers. Industry green purchasing policy would benefit from adoption of OECD green purchasing policy tools for government procurement that incorporate direct control, economic instruments and "suasive" instruments.

Direct control aspects would directly influence purchasing through use of external market leverage by:

• Admission, prohibition and registration procedures for certain agri-food related products, such as GMOs, products packaged in non-recyclable packaging, etc;

• Adoption of specific product standards and regulations supervised by official or semi-official bodies, such as giving preference to specific suppliers in specific high risk product categories only if they operate under certified environmental and quality management systems;

• Imposing take-back obligations and minimum quotas of returnable quantities for environmentally harmful products, such as packaging;

• Adopting product advertising rules which promote environmentally preferable goods; and

• User obligations, such as requiring end disposal through authorised channels or operating deposit-refund schemes for consumers.

Use of economic instruments in green purchasing policy involve financial incentives for consumers, such as deposit-refund systems, reward points for purchasing environmentally preferable products. So named "suasive" instruments support direct control methods by relying on incorporation of environmental awareness and responsibility into purchasing decision-making through:

• Compulsory information instruments such as declaration of environmentally hazardous materials, labelling obligations of Eco-friendly attributes, directions for proper use and end disposal, etc.; • Voluntary information instruments such as Eco-labelling, test reports, etc.;

• Industry self commitments to exceed environmental regulatory requirements for particular product groups;

• Consumer advisory services for providing information on environmental aspects of products; and • Use of preferred supplier lists, which identify and give preference to suppliers of environmentally

friendly goods and services.

Use of Eco-Labels

Use of official Eco-labelling schemes in purchasing decisions has considerable influence on consumer awareness and buying of environmentally preferable products. Although Eco-labels are mainly aimed at domestic consumers, they can serve professional purchasers as well. In the EU there is evidence that in some product groups labels are commonly preferred. Common products European Eco-labels include Blue Angel and TÜV Eco-Circle in Germany, Milieu Keur in the Netherlands and White Swan in Nordic countries.

Important agri-food Eco-labels are mainly available for organic-biologic foodstuffs or guarantee that no artificial fertilisers or chemical pesticides have been used in cultivation. Examples of such labels include AB in France, EKO in The Netherlands, LUOMU in Finland, KRAV in Sweden and Maerket-Dansk in Denmark. In addition, there are a number of labels for recyclable material content and recyclable packaging.

The Green dot scheme begun in Germany for recyclable packaging and is now increasingly being adopted by a number of other EU countries such as Portugal and Ireland.

Purchasing officers should develop and maintain Eco-label registers of suppliers whose products have been awarded Eco-labels for defined product categories to assist in purchasing decisions.

Box 2 provides general information on the types of environmental labelling applicable to products.

Type I: Third party eco-labelling programmes

• publicly available criteria developed by independent body • use multiple criteria and simplified life-cycle analysis

• specific standards developed for various product groups and markets • accessible to domestic and foreign products

• labels awarded when products meet defined environmental and performance criteria e.g. Demeter bio-dynamic organic produce logo

Type II: Industry self-commitments

• specifically developed by industry sectors

• applicable to specific products and markets e.g. phosphate free detergents, Green dot recyclable packaging, etc.

Type III: Independent third party Certification to ISO 14000 series of standards

• based on lifecycle analysis

• quantifies environmental performance across a range of environmental indicators

• environmental indicators established using life-cycle approach e.g. energy use, water discharges, air emissions, etc.

• product performance verified by credible independent third party which collects life-cycle inventory data and rates product in terms of environmental indicators

(Brah, 1997)

8.0

International Trade Issues

International trade rules are likely to have a significant influence on some of the measures to promote sustainable agri-food chains. Trends towards globalisation and freer trade can pose a potential threat to any unilateral European policy initiatives and instruments to promote and encourage agri-food chain sustainability. Promotion of sustainable development initiatives within the agri-food sector will need to ensure that WTO rules are not contravened.

The WTO is a policeman of global trade. It comprises 135 members. Members of the WTO abide by its four key principles:

• expanding trade concessions equally to all members;

• establishing freer global trade with lower tariffs in all sectors; • ensuring fairer trade by establishing rules; and

• improving competitiveness by removing subsidies.

The WTO negotiates the extent of tariff cuts and removal of trade barriers in its Trade Rounds, which take place every six or so years. The scope of trade rounds in recent sessions has expanded to include trade in agriculture and manufactured goods, which directly impacts on the agri-food sector.

In recent years, the WTO rules have been criticised by environmental groups and other NGOs for not giving due consideration to environmental aspects of trade in its pursuit of a “level playing field” in international trade. During the recent December 1999 WTO conference in Seattle, mass protests were organised by environmentalists. According to many environmentalists, WTO fair trade rules often clash with environmental objectives and sustainability.

Under WTO rules, it is illegal to distinguish between similar products based on the way they have been produced. Environmentalists fear that according to WTO rules, sustainably produced and processed agri-food sector products, which are labelled as such, must be treated the same as unsustainably produced and processed products. EU restrictions to further imports of agri-food products, such as products containing genetically modified organisms (GMO), on the basis of

environmental or health grounds may well be contrary to WTO rules. Negotiations over a Bio-Safety Protocol to the UN convention on Bio-diversity to regulate trade in GMOs and GMO commodity labelling broke down in 1999 because some countries claimed that it contravened WTO rules which forbid technical barriers to trade. The EU insists on precise labelling of GMO products and has not approved GMO commodity imports since April 1998. The EU seeks an agreement to cover GMO products in food, animal feed, and processing which, ensures adequate procedures for authorisations of transboundary shipments, including a duty to notify importing countries of planned shipments to allow tracebility.

There are potential conflicts between hard won multilateral environmental agreements, such as the Kyoto Protocol, and WTO rules. Proponents of sustainable development would like to see

international environmental agreements take precedence over trade rules and adoption of the precautionary principle when there are uncertainties about environmental or health impacts of agri-food products. Failure to do so has already resulted in the US challenging EU bans on hormone injected beef because of health concerns, which resulted in the WTO fining the EU. Similar challenges may also be faced by any EU eco-labelling schemes.

Dominant farm-exporting economies, such as the US, are pressing hard for elimination of agricultural subsidies. Such moves pose a great threat to the EU’s CAP, its largest single spending programme, which is aimed at encouraging more sustainable and extensive agriculture.

Concerns have also been raised by EU members with progressive environmental laws, such as regulations to increase the level of producer packaging recycling, due to claims from exporters to the EU that such laws contravene trade rules as they pose unnecessary barriers to trade.

Realisation and progress towards sustainable agri-food chains requires use of specific instruments, such as policies, regulations, targeted subsidies and taxes and eco-labelling protocols, to stimulate and accelerate environmentally sustainable production and processing. However, use of such instruments

is likely to be challenged as they may contravene WTO initiatives to eliminate technical barriers to trade.

9.0

Conclusions and recommendations from the Hearing

The main objectives of the Hearing Green Purchasing of Foodstuffs were:• Establish consensus about the environmental problems and inform about this to other stakeholders (governments, company, industry and consumer organisations etc.);

• Identify the important actors as presented in the background document; • Key role of purchasing /procurement officers

• Inform about current work in Europe through the background document and presentations at the hearing;

• How will we proceed - follow up: development on new initiatives based on ongoing work by key stakeholders.

The Hearing attracted approximately 40 participants with representatives from almost all stakeholders in the Agri-Food supply chain. The scheme below shows some of the organisations and companies present in their relation to the food supply chain. Beside the companies and organisations mentioned, representatives from environmental organisations (EEB, Norway), research organisations and local authorities attended the hearing.

Companies and organisations in the above figure are:

KRAV: Swedish Certification Body for Organic products according to IFOAM standards. ICA: ICA Handlarna, a major Swedish retail company.

Unilever: Unilever Sweden, food manufacturer

Sodexho: A major France based, international catering company. BEUC: European Association of Consumer Organisations.

Farmers: Farmers were represented through the French Young Farmers Union.

This wide range of representatives allowed the Hearing to discuss all relevant issues related to sustainable development in the food supply chain. The findings and conclusions resulting from the presentations and discussions are summarised in the next sections.

Final Consumer Agriculture Food manufacturer Retailers Governments: • Denmark • Sweden • EU KRAV Chemical suppliers Farmers Unilever

Conclusions

The main findings of the Hearing can be summarised as follows:

Environmental Issues:

• General consensus was reached about the environmental importance of the food chain

• Environmental improvement will require a life cycle approach, in which every stakeholder acts in accordance with his “ responsibilities”

• Environmental criteria, sufficiently clear or sufficiently widely accepted, are not readily available. Green products cannot be defined: knowledge and experience development, public opinion and technology will allow new developments and opportunities and thus shift the definition of Green Food

• There is a need for consensus on a widely accepted “definition” of green foodstuff. This will not focus on a final and definite formulation of specific requirements of “green foodstuff” but will address the main principles and requirements for “green foodstuff” creating an international common understanding of “green foodstuff” e.g. sustainable food supply.

Information dissemination:

• Consumers are insufficiently aware of and informed about environmental/sustainability issues in the food sector

• Eco-labels could be developed to support the consumers. Eco-labels reflect societal consensus and should be based on life-cycle considerations. No additional food eco-labels are required. At European level an eco-label should be selected from the available examples used in different countries.

• Lack of knowledge and understanding on Green Purchasing in developing countries, which need to be addressed. This will also relate to information dissemination and training e.g. technical assistance, in quality and safety principles and requirements as applied in the industrialised countries to allow Third World countries easier entrance to the food market in Europe, the US and Japan.

• An information exchange between EU countries and the third world countries ought to be developed focusing on the above quality and safety issues, and ecological and social principles and requirements.

• Need for more concrete guidelines for procurement officers in public organisations and in companies

• Need of information exchange between the different elements of the food production and consumption chain including dissemination of information on risk management.

Co-operation between stakeholders:

• Co-operation between all stakeholders is necessary

• Co-operation between companies and public authorities is required. The importance of

participation by the authorities was underlined in order to get confidence to actions, which might be needed, and to ensure the development of an appropriate regulatory framework.

• Co-operation with third world countries is important and can be organised through the UNEP working group on “Sustainable Food and Agriculture”.

• Green produce offers a potential win-win situation in co-operation between industrial and developing countries

Developments and initiatives:

• Companies in all sectors of the food supply chain have developed initiatives to realise environmental improvement all along the production and consumption chain;

• Interesting set of best practices available (Unilever, Goteborg, Sodexho, ICA/Ahold etc.) • Industry develops own guidelines – Good Agricultural Practice (GAP), at European level which

represent a starting point but which should be developed further;

• KRAV – initiatives from the Swedish Certification Body for Organic Products based on IFOAM organic agriculture practice standards form the most stringent example of sustainable agricultural production. Certification bodies in other countries apply the same standards.

Follow-up and further work

The main goal of further work in this field is to realise a more sustainable food supply chain by reaching agreement and commitment from the most important stakeholders in the food

production and consumption chain.

This might be achieved by:

• Starting up a process aiming at a clearer understanding of what constitutes a Sustainable Supply of Foodstuffs by for example organising “Product Panels” on selected Foodstuffs. The setting up of Product Panels as Pilot Projects is a process that has been suggested by the EU Commission as a means of developing the IPP Concept within the European Union, and a close co-operation between the different Directorates concerned e.g. DG Health and Consumer Protection, DG Environment, DG Agriculture, DG Enterprise and DG Internal Market.

• Initiation of a process to reach agreement on the main principles and requirements for a

Sustainable Food product e.g. “Green Foodstuff”. The industries present at the hearing presented their interest in participating in and contributing to such a process. The process could be launched by EPE and should bring together a number of authorities, companies and expert organisations. • A project aimed at establishing co-operation and involvement of Third World countries