Embracing Transformative

Technology to End Worker

Exploitation

BACHELOR THESIS WITHIN Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 hp

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Sustainable Enterprise Development AUTHORS: Måns Nilsson, Alek Kahn, Yiping Jiang

JÖNKÖPING April 2021

How Individual Resistance to Change Management Can Explain the

Limited Adoption of Worker Monitoring Tools in Multinational

Organizations.

Summary

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Embracing Transformative Technology to End Worker Exploitation Authors: M. Nilsson, A. Kahn and Y. Jiang

Tutor: Michal Zawadzki Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: forced labor, technology, social sustainability, CSR, monitoring tools, digital monitoring, resistance to change, technology change.

Definitions

Workers: the factory workers in developing countries who are the victims of human rights

violations, and the end users of the technology.

Users/practitioners: the lower-level management, within the focal firm, that will operate and

work with the technology.

Upper management/managers: the decision-makers within the focal firm who ultimately have

the final say.

Focal firm: the large multinational enterprise that uses factories in the developed world to

produce their goods through vertical integration or third-party contracts.

Digital Reporting Tools (DRT): Through an app, SMS, or automated phone survey, the technology enables focal firms to directly engage workers in their upstream supply chain and hear areas of concern. It enables two-way education by circumventing local factory owners.

Abstract

Background: The unethical treatment of factory workers is widespread, especially in developing countries. There is no international legal body with the jurisdiction to uphold universal labor rights. Hence, the responsibility to ensure worker well-being falls upon the multinational organizations that operate the supply chain. These focal firms often use social auditing; however, recent research reveals that this approach does not incorporate workers' experiences on a consistent basis. To address these shortcomings, a new technology has enabled organizations to connect directly with factory workers, we term the technology digital reporting tools (DRT).

Problem: Even though DRT potential is supported, their adoption rate amongst multinational organizations remains minimal. The benefits of these tools cannot be leveraged without firm implementation. In fact, the estimated market size for socially sustainable tools in global supply chains significantly outweighs their investment rates. This discrepancy must be explained to advance the industry.

Purpose: This thesis intends to deepen the understanding of individual and group level resistance within the change management field by researching a phenomenon that combines technology and social sustainability: DRTs. By recognizing the internal subjective experiences of potential users of DRT technology, we ultimately hope to inform DRT-providers and focal firms of internal and unrealized bottlenecks that hinder the adoption of these tools.

Method: The thesis employs an inductive research approach with a qualitative research design based on 8 semi-structured interviews. All respondents are potential users of the technology within focal firms.

Result: Upon researching the experience of potential users, we find that their willingness to suggest DRT to upper management is the primary mechanism that impacts adoption. We partitioned willingness to suggest into two aggregate dimensions: perceived acceptance of upper management and organizational culture. We find potential users hold an internal need to pitch DRT to upper management in monetary terms. Furthermore, half of DRT utility was unknown by respondents. Lastly, we correlate the sub-theories of change management to the different factors we identified.

Acknowledgements

We express sincere gratitude to all those that contributed and supported our study. First, we thank our tutor Michal Zawadski for sharing his expertise and knowledge in the field of change management. This thesis would not be the same without him. Second, we greatly appreciate all the interviewees who devoted their time and effort to contribute to the study. Finally, we wish to thank our Chairman Jean-Charles Languilaire for his guidance and insightful feedback.

Table of Contents

Summary ... i

Definitions ... i

Abstract ... ii

Table of Contents ... iv

1.

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 11.2 Digital Reporting Tools (DRTs) ... 3

1.3 Problem Statement ... 5

1.4 Purpose and Research Question ... 6

2.

Frame of Reference ... 7

2.1 Paradigms of Change Management ... 7

2.2 Why do Organizations Change?... 8

2.3 Lenses to Explain Change ... 9

2.3.1 Application to Empirical Research ... 10

2.4 Individual and Group Resistance to Change ... 11

2.5 Emerging Fields of Change Management ... 12

2.5.1 Technology Change Theory ... 12

2.5.2 CSR and Change Management ... 14

2.6 Problematization and Research Gap ... 15

3.

Methodology and Method ... 17

3.1 Research philosophy ... 17 3.2 Research Approach ... 18 3.3 Research Design ... 18 3.3.1 Data Collection... 19 3.3.2 Choice of Interviewees ... 19 3.3.3 Data Analysis ... 20 3.4 Ethical Consideration ... 22

4.

Findings... 24

4.1 Perceived Acceptance of Upper Management ... 25

4.1.1 Difficulty Quantifying the Business Case ... 25

4.1.2 Upper Managements Age, Gender, and Experience as Moderating Factors .... 26

4.1.3 Performance Expectancy ... 27

4.2 Organizational Culture ... 28

4.2.1 Loss of Credibility ... 28

4.2.2 Ability to Voice Ideas ... 29

4.2.3 Sustainable integration ... 30

4.3 Summary: Potential Users Willingness to Suggest DRTs ... 30

5.

Analysis ... 31

5.1 Perceived Acceptance by Upper Management ... 31

5.2 Organizational Culture ... 34

5.3 Potential Users’ Willingness to Suggest DRTs ... 35

7.

Discussion ... 38

8.

References ... 41

Figures:

Figure 1. Burrell and Morgan’s (1985) Paradigms………..………..….…….8Figure 2. The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology………….………13

Figure 3. Data Structure……….……….….….24

Figure 4. Aggregate Dimensions and Research Question 1………….……… 31

Appendix 1: Supply Chain Tools Market Estimate ... 45

Appendix 2: Interview Guide ... 46

Appendix 3: Interview Participants... 48

1. Introduction

______________________________________________________________________

This section states the background, research problem, and introduces the phenomenon under study. Further, the aim, purpose, and research question are explained, and the relevance of the research are emphasized. Connections are also made to the guiding theory.

______________________________________________________________________

1.1 Background

The forced exploitation of people for economic gain has evolved to become more challenging to detect, adjudicate and resolve (Bales, 2000; LeBaron, 2014; Gold, Trautrims, & Trodd, 2015). The most recent estimates from the International Labor Organisation (ILO) indicate that there are roughly 40 million victims of modern slavery, 24.9 million of which are forced laborers (ILO, 2017). Furthermore, these figures do not account for the unethical treatment and general exploitative practices that frequently occur for laborers in developing countries. There is a consensus within academia that inadequate working conditions in developing countries are a symptom of developed nation’s ongoing demand for high-quality goods at lower prices—in other words, consumerism (e.g., Bales, 2000; Barrientos, Kothari & Phillips, 2013; LeBaron, 2014; Bales, 2016; Berg, Laurie & Farbenblum, 2020). As a result, corporations outsource their production to locations with lower minimum wage rates, established manufacturing facilities, and developed global transportation networks to remain price competitive (Harrison et al., 2014). For example, Walmart’s guarantee of ‘Everyday Low Prices’ forces their managers to fragment and outsource production; however, outsourcing to developing nations carries many challenges along with it (LeBaron, 2014). For example, how can Walmart ensure the fair treatment of their factory workers when they have over 10,000 separate suppliers spread all over the world? This would be nearly impossible and quite costly to attempt. Therefore, it is common practice for large corporations to form contracts with third-party manufacturers with resolute but ultimately meaningless terms to uphold. If the public or NGOs discover labor violations, liability is passed to the third-party contractor, while the focal firm claims to be unaware and therefore not responsible for the breach (LeBaron, 2014).

Despite the ILO's precise definition of universal labor rights, the UN agency does not hold authority without domestic consent. For example, China has not ratified the 1930 Forced Labour Convention, the Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise

Convention, Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, and the 1957 Abolition of Forced Labour Convention (ILO, 2021). Any country that has not ratified fundamental conventions of the ILO are not bound to uphold their content. Therefore, the responsibility to ensure basic human rights and fair working conditions, for the time being, falls onto the organizations that employ the suppliers and operate the supply chain.

Organizations currently attempt to address the previously mentioned issues through social auditing, which involves an in-person inspection of the factory by professionals not affiliated with the factory owners. This form of supply chain monitoring has evolved to become an industry in itself, characterized by increasingly complex and costly procedures (Lund-Thomsen and Lindgreen, 2014). At their best, social audits are a benchmark that firms use on their quest to be socially responsible (Locke & Romis, 2007; Rahim & Idowu, 2016). The procedure is typically part of a more encompassing CSR program aimed to (1) contribute to the society and community; (2) ensure product safety; (3) minimize environmental degradation; (4) ensure information security; and (5) eliminate forced labor and human rights abuses (Harrison et al., 2014).

However, recent research reveals that, by itself, social auditing does not adequately resolve human rights violations and monitor fair working conditions—it has plenty of shortcomings (Outhwaite & Martin-Ortega, 2019; Locke & Romis, 2007). For example, Outhwaite and Martin-Ortega (2019) note that factory auditors cannot accurately determine labor conditions solely at the moment of factory inspection; they describe the endeavor as a 'snapshot' that reveals a limited picture of everyday working conditions. Take the 2013 Rana Plaza tragedy for example: in 2013, a Bangladesh garment factory named Rana Plaza collapsed. The incident killed over one thousand workers and gained massive media attention because it occurred shortly after a successful social audit had been conducted (Labowitz & Baumann-Pauly, 2014). This event lost millions of dollars for the companies associated with the factory and, most importantly, highlighted the necessity for social sustainability in the supply chain: lives are at stake.

Beyond questioning the efficacy of short and infrequent factory inspections, researchers have extrapolated the specific problems stemming from this half-hearted system: workers' voices are neglected (Locke, Qin & Brause, 2007; Nishinaga & Natour, 2019). Auditors only interview a small percentage of the total workforce. Furthermore, those selected may fear management

repercussions once the auditors have left (Merk & Zeldenrust, 2005; de Haan & Van Dijk, 2006). For example, in the Kenyan cut-flower industry, Hale and Opondo (2005) illustrate that most workers were considered passive subjects within the social framework despite an ambitious code of conduct. Moreover, Claeson (2019) reveals how social auditing in the electronics industry may harm their chances for remediation, therefore silencing their voice. It is evident that organizations need a system in which workers' experiences are valued on a consistent basis.

1.2 Digital Reporting Tools

Outhwaite and Martin-Ortega (2019) describe the inclusion of factory workers’ experiences as two-way education. This idea denotes the mutual flow of information between focal firms and workers. Focal firms benefit from the information they receive from workers because it reduces future risk, reveals areas of improvement, attracts workers, and most importantly, enables the aid of their stakeholders (Outhwaite & Martin-Ortega, 2019). Workers benefit because they are able to voice grievances, access effective remedies, and be informed of local rights (Nishinaga & Natour, 2019).

The best way to facilitate consistent and affordable two-way education is through technology; thus, a recent industry of technology platforms that enable workers to voice their experiences in global supply chains has emerged. However, the technology has yet to develop a standardized name. The terms 'digital reporting tools,' 'worker engagement tools,' and 'digital monitoring instruments' are used interchangeably (Farbenblum, Berg & Kintominas, 2018; Nishinaga & Natour, 2019). We selected the term 'digital reporting tools' (DRTs) to ensure clarity and consistency; this is the thesis' central phenomenon.

DRTs are a relatively new approach to address human rights violations and monitor working conditions in global supply chains. The first DRT was developed around 15 years ago, and the vast majority of the existing research on the phenomenon comes from 2010 to present. What is a DRT and how does it support human rights? Through an app, SMS, or automated phone survey, the technology enables focal firms to directly engage workers in their upstream supply chain and hear areas of concern, such as lack of consistent paychecks or limited work breaks. Furthermore, unscrupulous factory managers are circumvented. Workers in developing countries are often not informed of their local rights or that their maltreatment may be illegal (Outhwaite & Martin-Ortega, 2019). DRTs enable two-way education so focal firms can (1)

inform workers of their local rights, and (2) describe the process of self-advocacy (Nishinaga & Natour, 2019). Additionally, these platforms enable workers to rate employers which incentives factories to uphold their codes of conduct (Melson & Anderson, 2017).

Overview of Phenomenon and Guiding Theory

Despite the unmatched opportunities that these technology solutions offer focal firms, the industry remains minimal. Nishinaga & Natour's (2019) paper created an extensive and detailed landscape review of the field. Of the 18 DRT's found in the study, the different tools' median market size equals $3.5 million (based on annual revenue). This section will provide examples of two real DRTs, describe the individuals of interest in this study, and reveal the guiding theory to explain the phenomenon.

Example Solution:

Laborlink

Laborlink is a mobile and computer platform from Elevate that creates a two-way communication channel that enables workers to get their voices heard by sharing their views and experiences in real-time. Focal firms can gain an accurate insight into worker opinions and well-being in their supply chains. Laborlink's technology has reached about 2.5 million workers in 22 different countries; even though this can seem like a relatively large number, Laborlink is one of the largest and oldest DRT's. It was established around 2010. (Elevate, 2021)

Example Solution:

Ulula

Ulula is a smaller firm with a similar aim and purpose. Launched in 2013, Ulula is a three-step customizable supply chain management software focusing on monitoring and evaluating working conditions. Ulula provides supply chain workers with an effective and safe platform to voice their experiences, report abuse, and disseminate health and hygiene information to slow the spread of COVID-19. The firm emphasizes four principles: Multichannel (via WhatsApp, SMS, WeChat), Multilingual, Automated, and Anonymous. Ulula's annual revenue is $3.5 million, representing the median market size for DRTs. (Ulula, 2021)

Despite DRT's potential to empower and safeguard workers, investment in the private sector remains as low as $5 to $10 million annually, with a similar but growing figure in the philanthropic sector (Kintominas et al., 2018). These figures are marginal compared to Deloitte’s (2019) $807 million to 2.1-billion-dollar estimate of the ‘responsible supply chain tools’ market in 2018. ‘Responsible supply chain tools’ excludes social audits, which comprise a significant segment of the market, but includes risk assessment, product traceability, ethical recruitment, ethical sourcing, and worker engagement (see Appendix 1.) Within these

sub-categories, DRTs apply to worker engagement, ethical recruitment, and risk assessment markets; therefore, they hold potential within a 428 million to 1 billion dollar industry (Deloitte, 2019). What is impeding organizations to change their auditing and monitoring procedures to DRTs? At this point in the thesis, we have to take a stance. There are many possible reasons

why firms are not adopting DRTs. So far, we know that they are a promising, but relatively new

phenomenon. Even though a quantitative study of the market may be insightful, it is difficult for researchers to even know where to start. Current research needs a deeper understanding of DRT adoption in itself.

Contemporary models that describe and predict adoption behavior of technology, such as the technology acceptance model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use Technology (UTAUT), value users’ perception (Venkatesh & Davis, 2000; Venkatesh et al., 2003). Users are the individuals who will be working with the technology; in this case, they are within the focal firm. Therefore, our research will assume that lower-level managers within multinational focal firms, who work directly with sustainability and supply chain management, will be the most likely to be aware of DRTs (because of their novelty). Therefore, their perceptions may help explain the discrepancy between DRT’s high potential and low focal firm adoption. We term these individuals (who are the focus of our empirics) potential users or practitioners.

When trying to understand the complexities of change, organizational change management is relevant and, therefore, it is this management field we will use to explore this phenomenon. DRTs are a unique combination of social sustainability, global supply chain management, and technological innovation. Therefore, we will focus on the following sub-theories of organizational change management: individual and group resistance to change, technology change, and CSR change.

1.3 Problem Statement

By this point, we have illustrated the following: (1) the fundamental mechanisms behind human exploitation; (2) the necessity for corporate intervention; (3) the inadequacy of traditional social audits; (4) the need for two-way communication and consistent monitoring between focal firms and factory workers; (5) the emergence of DRTs and their purpose; and (6) the low investment/adoption rate of DRT. The overarching societal problems and the specific problem related to our research are demonstrated through the narrowing progression of these points.

The underlying problem is multifaceted and ubiquitous. It stems from the standard of living that the developed world has grown to expect. Furthermore, it stems from our flawed economic system where profits and short-term goals often supersede the interests of those without a voice—whether it be the environment or impoverished factory workers. Although this is not the specific problem our research aims to address, we felt it imperative to recognize our work's broader context.

Now onto the problem that is the topic of our empirical research. As supported in Section 1.2, we assert that DRT’s present unequalled potential when addressing human rights violations in the developing world. Therefore, we would assume that large multinational enterprises, what we label as 'focal firms', would quickly adopt these new tools. However, the discrepancy between Deloitte’s (2019) estimated market potential of responsible supply chain tools and the low investment figures of DRTs reveal that this is not the case.

Although there are some explanations for this discrepancy, which we will discuss in Section 2.6 of the frame of reference, there has been no explicit connection made between the field of organizational change management and DRT’s. Even though potential users are often researched when studying an organization's adoption of technology, their perspective of DRTs is non-existent.

1.4 Purpose and Research Question

This thesis intends to deepen the understanding of individual and group level resistance within the change management field by researching a phenomenon that combines technology and social sustainability: digital reporting tools. By recognizing the internal subjective experiences of potential users of DRT technology, we ultimately hope to inform DRT-providers and focal firms of internal and unrealized bottlenecks that hinder the adoption of these tools.

Research Question:

• What do potential users of DRT technology perceive to be the factors that impact their adoption?

This research question is relevant because it considers the subjective point-of-view of the potential users (the employees in the focal firms) in the context of a novel phenomenon. Organizational change management and the sub-theories selected therein, will help to deepen the understanding of DRT’s marginal adoption.

2. Frame of Reference

______________________________________________________________________

This section starts off by presenting the method of gathering literature. Further, previous research regarding the general Change Management field are reviewed, it then introduces different lenses that explain change. It then goes into the specific sub-fields of Change Management that are more relevant to this research, this includes: Individual and Group Resistance to change, Technology Change Theory, and CSR in Change Management. Finally, problematization and the identified research gap are stated and explained.

______________________________________________________________________ Searching and gathering literature and research on the phenomenon and organizational change management theory was done through a systematic approach. The literature and research was mainly accessed through Jönköping University’s library database, Primo, but the search engine Google Scholar was also used to broaden the available articles. In the searches we included the following keywords: forced labor, technology, social sustainability, CSR, monitoring tools, digital monitoring, resistance to change, technology change, and UTAUT. The literature types includes, but are not limited to, peer reviewed journals/articles, and websites. Protocols and summaries of conferences have also been used in order to obtain up-to-date knowledge of the phenomenon under study. To perform a thorough and extensive review of the available literature on the theories and phenomenon under study is one of the most crucial parts of a research study (Bryman, et al., 2018). Bryman et al. (2018) also emphasizes the importance of a well-performed literature review since it lays the foundation on which the authors will build their research on. The review of existing literature gave the authors insight into how previous studies have been conducted which helped to construct the frame of reference, bring greater knowledge of the phenomenon, and highlighted gaps in the research and theory.

2.1 Paradigms of Change Management

Our main theoretical field is organizational change management. Organizational change management "refers to planning, organizing, leading, and controlling a change process in an organization to improve its performance and achieve the predetermined set of strategic objectives" (Ha, 2013, pp.1). The field is abundant with research and continually evolving; however, our empirical study cannot be adequately understood until we outline the fundamental change management paradigms and theories. Within academia, a paradigm is "a term which is intended to emphasize the commonality of perspective which binds the work of a group of theorists together in such a way that can be usefully regarded as approaching social theory within the bounds of the same problematic” (Burrell & Morgan, 1985, pp.23).

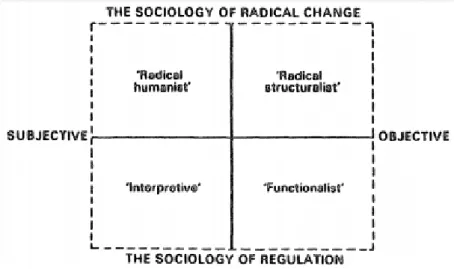

Figure 1. Burrell and Morgan’s (1985) Paradigms

Change management is not a rigid and unified field with defined boundaries because it borrows from, among other things, psychology, economics, innovation, and leadership research. Figure 1 illustrates Burrell and Morgan’s (1985) four paradigms, which can be used to differentiate organizational change theorists' philosophical positions: functionalism, interpretivism, radical humanism, and radical structuralism. These four paradigms contrast two sets of two variables: (1) subjectivity/objectivity and (2) regulation/radical change. These distinctions explain conflicting conclusions. For example, suppose a psychologist and an economist try to explain why an organization changed its overtime work policy. The psychologist will study the internal drivers within the organization and focus on the subjective experiences of managers. On the contrary, an economist may look at data relating overtime hours to productivity. The two researchers will come to different conclusions—understanding change management paradigms explains the distinction. However, it is essential to note that the content of most change management research is not confined to one paradigm nor explicitly stated by the researcher. The following sections will draw connections between change management paradigms, determinist/voluntarist explanations of why organizations change, and the varying perspectives of change (strategic, group, and individual).

2.2 Why do Organizations Change?

Scholars of change management can view change to be determined by external economic and technological occurrences or as a consequence of internal organizational choice and processes (McLoughlin, 1999). The two positions are labelled determinism and voluntarism, respectively. Determinism views a cause-effect relationship between the economic environment and the

actions of the firm (Hughes, 2010). In other words, organizational change is solely determined by the external environment. Voluntarism emphasizes managerial choices and actions affecting organizational change. The drawback of determinism is that it tends to underplay the manager's influence and outsources change to an external and intangible force (Collins, 2000).

Even though these two positions are quite polarized, the reality for researchers and managers is likely a hybrid of the two concepts (Hughes, 2010). For example, Dawson (2003) states that even though the initial trigger for change may be external, such as changes in competitors' strategies, government legislation, and changing social expectations, it would be incomplete to preclude an internal change context, after all, managers have the final say.

2.3 Lenses to Explain Change

Under a determinist position and functionalist (objective) paradigm in change management, a researcher would likely investigate macro-forces triggering change, typically with quantitative data (Hughes, 2010). This 'macro' perspective is associated with the strategic level of change management. This view perceives an organization as a single decision-making actor rather than an amalgam of different stakeholders with, inevitably, conflicting interests. Strategic change decisions can include reorganization, diversification, the shift in core technology, and business process redesign (Hughes, 2010).

Unlike the unitarist view of strategic change, internal subdivisions create a more complex and nuanced view of change. Researchers can divide organizations into groups and individuals. Groups are the 'building blocks' of organizations, and research from this view usually entails studying group behavior psychology (Hughes, 2010). Clegg et al. (2008) describe a group as, "two or more people working towards a common goal" (pp.92). Group research is quite developed because there are always norms that facilitate everyday interaction, even if they're unspoken. Some norms impede change, such as groupthink, which occurs when group members value unanimity and agreement over an objective evaluation of the costs/benefits of alternatives (Janis, 1972). The general norms of a company culture significantly impact the efficacy of change initiatives.

Organizations only act through the actions of individual employees. The societal factors that impact employee behavior include motivation, attitudes, perception, learning, values, and

personality (Thompson & McHugh, 2009). Individuals act differently to stimuli; therefore, every employee will have a distinct view of the change process. Rashford and Coghlan (1989) highlighted the individual perceptual responses to change and concluded that they are not always positive. Their four-step model starts with denying and moves on to dodging, doing, and finally, the sustaining stage. These initial negative responses include distortions such as stereotyping, the halo effect, the self-fulfilling prophecy, and projection (Clegg et al., 2008). Successful change is predicated on overcoming these initial individual barriers.

In sum, there are three different lenses to view organizational change: strategic, group, and individual. If a researcher believes that change originates from external factors (determinist) and operates within a functionalist (objective) paradigm, then their analysis should reflect a strategic lense. Group and individual levels focus on managers in the change process (voluntarist) and divide the unified organization to understand subjective experiences, which aligns with the interpretivist or radical humanist paradigm.

2.3.1 Application to Empirical Research

At this point in the frame of reference, it is essential to shed light on our perspective to contextualize the following technology and CSR sub-theories of change management. Our research assumes the initial impetus for change is triggered by the changing attitudes concerning social sustainability and human rights. If we were to prove this in our empirical study, it would be a determinist view of change—resulting from external forces. Dawson (2003) notes, however, that the external and internal change processes can occur simultaneously or sequentially. Our research will assume that organizational change is triggered by growing pressures for social sustainability in global supply chains and aims to focus on the internal organizational change processes that occur thereafter. An internal investigation must recognize varying factions within the organization; therefore, we will focus on group and individual levels of change. Furthermore, we will embrace individuals' subjective experiences and not distinguish between regulation or radical change. Therefore, our change management paradigm will fall somewhere between radical humanist/interpretive. The empirical research will hold a voluntarist position to explain organizational change.

All of the following sections describing sub-fields of change management, including individual and group resistance to change, technology acceptance, and CSR change, will be viewed from

the paradigms and perspectives presented above. Section 2.6 will clarify these delineations and describe the research gap in change management literature that our empirical research will address.

2.4 Individual and Group Resistance to Change

Resistance always accompanies change within an organization. Even though the phenomenon is accepted, there are different views of its nature (Dent & Goldberg, 1999). Kotter (1995) states that resistance to change could be found everywhere in the organization and, in describing solutions to overcome resistance, implies its inevitability. According to Lewin (1951, as cited in Burnes, 2004), resistance is the force against the driving forces for change to maintain the status quo. To put it in another perspective, Schein (1995, as cited in Ha, 2013) describes three management cultures in an organization: operational culture, engineering culture, and executive culture. When these three spheres do not align, resistance to change emerges. Furthering the dynamic between operational and executive spheres, Ford and Ford (2009) assert that resistance to change can be used as feedback from day-to-day employees to top managers. There are three views of resistance to change: (1) mechanistic, (2) social, and (3) conversational (Ford et al. 2008). Our research will adopt the social view by understanding that resistance is natural and neither good nor bad. It simply reflects the force for change against change (Ford et al., 2008). Not all theories assume this position, Van de Ven and Pool’s (1995) life-cycle theory regards resistance as irrational and unnatural. Hughes (2010) states resistance remains in the eye of the beholder: managers can see disloyal behavior while fellow employees see morally justified action. In sum, the abstract nature of resistance has created many contrasting views; there is not one correct answer.

Kotter and Schlesinger (1979) identified why individuals resist change: (1) people’s desire not to lose something of value, (2) misunderstanding the change and its implications, (3) believing the change does not make sense for the organization, and (4) their low tolerance for change. Palmer et al. (2008) expressed similar sources of resistance: dislike of change, discomfort with uncertainty, perceived breach of psychological contract, and excessive change. Kiesnere and Baumgartner (2019) find that employees will not want to change if they are satisfied with the status quo, or if they feel insecure about losing their job, control, or monetary benefits. As a result of these factors, manifestations such as absenteeism, withdrawal, and disruptive behavior

can occur (Hughes, 2010). Palmer et al (2008) find that identifying specific sources of resistance is the first step to overcome change obstacles.

On a group level, King and Anderson (2002) find change-promoting factors to be group cohesiveness, social norms, and participation in decision making. The researchers describe potential managerial approaches to overcome group resistance, including education and communication, involvement, support, negotiation, manipulation, and implicit coercion. If members feel that their voice is heard and that they are a part of the change process, many defensive mechanisms can be overcome.

Resistance to change management is extensively researched and challenging to cover comprehensively. In sum, many models show individual and group resistance sources, followed by prescriptions on how managers can overcome the obstacles. We note, however, that these concrete models stand in contrast to the subjective nature that is intrinsic to individual and group resistance. One main takeaway from this section is that even though researchers can find common sources of individual and group resistance, the reality is always an amalgam of contrasting subjective experiences. To fully understand resistance and conducive factors to a new phenomenon, such as DRTs, open-minded qualitative research that focuses on the individual’s experiences is necessary.

2.5 Emerging Fields of Change Management

2.5.1Technology Change Theory

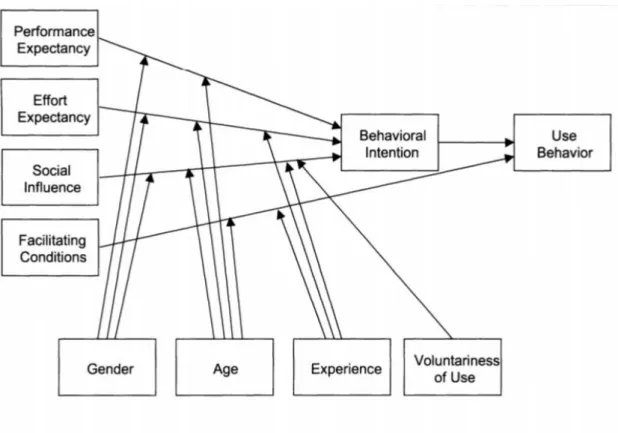

This sub-field of change management is relevant because DRTs are technological tools that require organizational change in order to be implemented. The connection between the increasing use of information technology (IT) and individual acceptance to change has become a developed research field. Davis (1989) created the technology acceptance model (TAM) to describe how users accept and use new technology by combining perceived usefulness with perceived ease of use to, ultimately, determine usage behavior. This model identified the need to study users. Venkatesh et al. (2003) also expanded on the work of Davis (1989) with the development of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT). It combines TAM with the theory of planned behavior (TPB) to predict user acceptance of IT. As illustrated in Figure 2, the model identifies four factors: performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social

influence, and facilitating conditions, which are moderated by age, gender, experience, and voluntariness (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

Figure 2: UTAUT (Venkatesh et al., 2003)

Researchers have applied this model to various settings, sectors, technologies, and use times (adoption, initial use, or post-adoptive use), often using questionnaires. When studying user's technology acceptance, various researchers added endogenous mechanisms such as trust, enriching social influences, and computer self-efficacy. Chiu and Wang (2008) later added task value and task cost to the model (Venkatesh et al., 2016). UTAUT is a flexible model that thrives because of its ability to be extended with different factors and moderators. This enables an accurate investigation of new technologies.

The purpose of briefly discussing technology acceptance models is to demonstrate the complexity and development of this relatively specific field and to illustrate key factors researchers consider, notably users’ perception. In Section 2.6., we will discuss how we intend to apply various elements of these models to our research without directly using the model and associated methodology.

From a psychological perspective, Kim and Kankanhalli (2009) assert that status quo bias can explain user resistance to information system implementation. Status quo bias is when people

prefer things in their current state—even if the change has a positive net benefit (Kim & Kankanhalli, 2009). Zachhauser (1988, in Kim & Kankanhalli, 2009) divides status quo bias into three main categories: rational decision making, cognitive misperceptions, and psychological commitment. Under rational decision-making, there are two costs: transition costs and uncertainty costs. A transition cost can include learning costs and even permanent costs—if there is a loss of work due to the new IT. The uncertainty costs under the rational decision-making bias are often irrational; it is the uncertainty itself that creates the cost (Kim & Kankanhalli, 2009). The second category of status quo bias is cognitive misperception. It is the psychological observation where losses appear proportionally larger than gains in value perception. Therefore, loss aversion can result in status quo bias because even small losses could be perceived to outweigh more significant benefits (Kahneman & Tverrsky, 1979). The third category is based on psychological commitment, which includes factors such as sunk cost, social norms, and efforts to feel in control (Kim & Kankanhalli, 2009).

2.5.2 CSR and Change Management

As humans continue to infringe upon environmental thresholds, there has become a growing need to change business practice. People do not understand that societal change can only happen as a result of conscious individual action. Therefore, a cognitive disconnect between what people know is 'right' and what they do emerges (Ha, 2013). Kiesner and Baumgartner (2019) state that resistance to sustainable change might result from a factor of denial about the business impact on society. Buchanan and Badham (2008) express a similar obstacle as 'ignorance’— the failure to understand the problem. If individuals only view the adoption of technology in monetary terms, they may understate its true potential.

Individuals must reconcile their individual goals, company goals, and ethical/societal expectations. Ha (2013) states that a competitive and hierarchical work environment leads workers to favor their personal goals, therefore ignoring ethical standards. Even though CSR is a field that expands to every other management field, its application to our research is especially relevant because of two reasons: (1) CSR is the process of changing organizational processes to account for exogenous consequences, the two fields are inseparably connected; (2) the ultimate goal of DRT’s is to monitor and safeguard the human rights of factory workers, not to cut costs.

2.6 Problematization and Research Gap

Change management is a dense field. Upon researching the connection between resistance to change and DRTs, Nishinaga and Natour's (2019) landscape review of DRTs provides the only discernible relationship between organizational change and the phenomena. The authors assert three sources of resistance for firms: (1) the business case is difficult to quantify for DRT; (2) it is challenging to ensure data quality, safety, and comparability; (3) focal firms may have insufficient capabilities of implementation and decision-making power. From a change management perspective, these barriers do not apply to our research for three reasons. First, they would likely fall under an objective paradigm, either functionalism or radical structuralism, because academics can research and overcome the aforementioned challenges with quantifiable data. Second, Nishinaga and Natour's (2019) first two points hold an implicit determinist position to explain why organizations change because it is the external environment that determines the focal firm's decisions. The third challenge may be considered voluntarist because it mentions focal firms’ internal technological capabilities; however, it is not detailed and precludes psychological and personal perspectives to user technology adoption. Finally, the author's points are from a strategic level of change because it is a unified firm's macro perspective—the focal firm is not divided into sub-groups.

In recognition of the technology acceptance model (TAM), the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT), individual psychological biases related to technology/CSR, and individual and group resistance to organizational change in general, we find that research explaining focal firm's resistance to DRT adoption is not comprehensive. We have identified the following gaps in the change management theory with regards to previous research on the phenomenon: (1) the theories mentioned above have not been generally applied to the DRT phenomenon; (2) research connecting DRT adoption to change management is not comprehensive; specifically, no work has been done to study subjective individual experiences of potential users in focal firms. Our research will contribute to this gap by researching potential users of DRTs to explore and understand which factors influence organizational adoption. This will contribute to resistance to change theory by identifying, amongst a variety of different theories, the most relevant change management theories to understand DRT adoption.

Hughes (2010) explains that resistance to change varies amongst every individual in the organization. When explaining a new phenomenon, it is not easy to apply existing models in

markedly distinct contexts. For example, the perceived barriers to implementing a new business communication platform will be different from a DRT used to monitor workers' well-being in developing countries. We intend to set the groundwork for this emerging field by listening to the subjective experiences of potential individual users of the technology. The theories generally guiding our research will be status quo bias; UTAUT determinants (performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence); UTAUT moderators (age, experience, gender, voluntariness); general explanations of individual and group resistance; and individual resistance to CSR. However, these are simply the guiding theories we will draw connections from. As stated above, there is no one theory that perfectly applies to a new phenomenon, especially when the topic is subjective.

In sum, we do not find that previous research and existing theory are comprehensive and relevant enough to address the social phenomenon of DRT-implementation. We believe that potential users should be studied instead of the organization as a unified whole because we assume that they will be the most knowledgeable about new socially sustainable technology. Relevant technology models also focus on these individuals when studying adoption behavior. Compiling various change management theories enables our research to identify critical factors that influence DRT adoption. Furthermore, there is no change management research on technological CSR solutions in global supply chains.

3. Methodology and Method

______________________________________________________________________

This section starts off by explaining the rationale behind the chosen research philosophy, it then moves on to explaining the approach and design of the empirical research. Thereafter, the method of data collection, choice of interviewees, and data analysis are explained in detail. Finally, ethical consideration is discussed thoroughly.

______________________________________________________________________

3.1 Research philosophy

There are different approaches to management and business research. Unificationists advocate that all management and business research should unite under one strong philosophy, paradigm, and methodology of research (Saunders, et al., 2019). We believe that this approach is very limiting and could neglect important findings and research within the area; instead, this paper will take a pluralist approach. A pluralist point-of-view, unlike unificationists, suggests that each different research philosophy and paradigm makes a valuable contribution to management and business research, since they represent different distinct ways of viewing organisational realities (Saunders, et al., 2019). This is highly applicable to change management.

In business and management research, interpretivism aims at looking at organizations from the perspective of different individuals or groups of people. It emphasizes that there is a complexity regarding how different entities in the same organization can perceive different workplace realities (Saunders, et al., 2019). It focuses on multiple interpretations, complexity and meaning-making, and is therefore suitable where the phenomenon or topic under study is not easy to quantify. In this paper, interpretivism will be used as the research philosophy since the studied topic is not quantifiable. Interpretivism was chosen since it helps to answer the stated research questions by creating an understanding of reality through people’s perspective of it (Collis & Hussey, 2014). By using the interpretive paradigm, this paper observes and interprets the social world and people in order to understand it. Since the topic of study is not quantifiable, data and insights from professionals in the field must be interpreted in order to develop theory, it is also important to enact the social reality in a subjective matter when developing theory to be used in an organisational context (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Furthermore, interpretivism adopts a small sample size that focuses on valid theory building (Bryman, Bell & Harley, 2018; Collis & Hussey, 2014), and is therefore highly suitable for the intentions of this paper.

3.2 Research Approach

There are three main approaches to research: (1) deductive is when conclusions are derived from a set of theory-driven premises, in other words, testing existing theories; (2) inductive is when the reasoning suggests that there is a gap in the logic reasoning between the conclusion and the premises; (3) abduction is when reasoning moves back-and-forth between theory and empirics, and little by little a new theory emerges (Saunders, et al. 2019).

This thesis will operate an inductive research approach. When collecting data in order to explore a phenomenon and generate theory building, we believe that an inductive research approach is the most appropriate because the strength of induction is its ability to develop an understanding of how humans interpret the social world, by following empirical data to produce theory (Saunders, et al., 2019). When trying to understand and explore the phenomenon under study in this paper, we believe that it is more realistic to treat the respondents as persons whose behaviour is a consequence of the way their perceive the world and, in this context, how they perceive their organizational experiences, rather than simple research objects who has a mechanic way of responding to specific matters and events. Further, according to Saunders et al. (2019) induction also enables alternative explanations to the same phenomenon. This is valuable in our research since it allows for various explanations to a certain circumstance that the researchers might not have thought of before. Therefore, for this research, we find that the inductive approach benefits this particular study, and the deductive or abductive approach would be less beneficial, and even limiting. Furthermore, due to the connectivity to humans and their subjective interpretations, views, and thoughts, the inductive research approach matches the interpretivist philosophy well.

3.3 Research Design

The use of an inductive research approach allows for qualitative research design (Saunders, et al., 2019; Collis & Hussey, 2014). The qualitative research design will be used to collect empirics that contribute to fulfilling the purpose of this paper and help answer the research question. Semi-structured interviews will be conducted where the interviewees express their feelings, thoughts, and overall point-of-view which then will be interpreted and analysed by the researchers. This will result in the development of a theory that can further explain the studied phenomenon.

3.3.1 Data Collection

A variety of approaches for data collection were assessed in order to grasp the optimal approach for answering our research question and fulfilling the purpose of this paper. It is crucial to choose an optimal data collection strategy because the reliability and validity of the findings, and ultimately analysis of them, are highly dependent on the usage of a correct and sufficient data collection method (Collis & Hussey, 2014). According to Collis and Hussey (2014) qualitative data is essential in order to create depth and draw conclusions of the study.. Since this paper intends to understand a social phenomenon related to an organizational context, the empirical primary data collection will be done through individual semi-structured interviews with industry professionals in the private sector that possess both broad and in-depth knowledge about the phenomenon under study. The questions that were used in the interview were primarily open-ended, the reasoning behind this approach was to encourage the interviewee to elaborate on their own answers and allow the discussion to become more free flowing, with the intention of generating more in-depth and accurate data. To optimize the data collection through the interviews, interview questions were prepared thoroughly in advance and adequate research was done to ensure a good quality of the questions and a beneficial structure of the interview. In total, over 8,5 hours of interview material were collected from 8 interviews with 8 different interviewees, with a mean interview length of around 65 minutes per interview (see Appendix 3). The interviews were conducted via Microsoft Teams and Zoom because of the COVID-19 restrictions. These platforms were used to conduct the interviews because it was technology that all interviewees were comfortable using and having the video on made it, to a high degree, resemble an in-person interview.

3.3.2 Choice of Interviewees

Judgemental sampling was the sampling method that was used in this study. According to Collis and Hussey (2014), judgemental sampling is a sampling approach which means that persons participating in the study are chosen based on their knowledge and expertise on the phenomena or in the field under study. This paper used this sampling method since it avoids a random sample. This method is highly beneficial for the purpose of this study, since it makes the empirical findings more accurate and credible because it excludes people that lack sufficient knowledge on the phenomena under study and which information would be of little use to the research itself.

For this study, using judgemental sampling meant that the interviewees all possessed knowledge of the phenomenon under study and that finds themselves in an organizational setting, and could therefore give reliable and useful information. The interviewees all worked, or had experience and knowledge of working, in organizations that have international suppliers and supply chains and where DRTs therefore could be implemented in a beneficial way. Since the study is concerned with the individual barriers, the individuals interviewed were employees who were not at the upper management of the organizations but were in positions where they could initiate change, and specifically DRT implementation. Due to the nature of an inductive approach, it can be argued that data saturation is unrealistic since themes that will be derived from the empirical data can be argued to be close to unlimited (Bryman, et al., 2018). Hence, the number of interviews were determined beforehand, the researchers determined that preferably eight in-depth interviews should be conducted.

Since this thesis aims to further explore and understand individual and group resistance to DRTs, which is a relatively new phenomenon, the choice of organizations was not specified to any considerable extent. The organizations were chosen that had international suppliers and a global supply chain where the implementation of DRTs could be a realistic option.

3.3.3 Data Analysis

Thorough and sufficient analysis of the collected data is fundamental in qualitative research (Collis & Hussey, 2014). In this paper, thematic analysis will be operated to analyse the empirics. According to Braun and Clarke (2012), “[thematic analysis] is a method for systematically identifying, organizing, and offering insight into patterns of meaning (themes) across a data set.” (p. 57). Thematic analysis focuses on meanings across a whole data set and enables the derivation of patterns of relevance to the research (Braun & Clarke, 2012), this method is therefore useful to use in order to make sense of relationships and commonalities when studying qualitative data derived from interviews. This makes thematic analysis optimal for the purpose of our research. Since this research used an inductive approach, the themes and patterns will emerge and be identified from the data set, rather than having predetermined themes within which the data can be categorized (Braun & Clarke, 2012). This bottom-up approach is appropriate since it can identify unexpected themes and relationships that might otherwise have been overlooked by the researchers.

Braun and Clarke (2012) suggests a six-phase approach to conducting thematic analysis. The researchers will conduct the analysis in the way suggested by Braun and Clarke since it offers

a systematic and thorough step-by-step approach to analysis that makes the analysing-process simple to follow. The different phases are presented below.

Phase 1: Get familiar with the data. Phase 2: Generate initial codes. Phase 3: Search for themes. Phase 4: Review potential themes. Phase 5: Define and name the themes.

Phase 6: Produce and write down the analysis-findings.

Phase 1: One of the best ways of getting familiar with the data is to first re-listen to the recorded

interview material and then to transcribe all the recorded interview data to read and re-read it while at the same time taking notes (Collis & Hussey, 2014; Clarke & Braun, 2012). In this paper the researchers embraced this approach and familiarized themselves with the material by listening to the interviews, transcribing them, and re-reading the transcriptions while taking notes. Collis and Hussey (2014) also emphasizes that it is important that the researchers get familiar with the data before starting the discarding process since this is the best way of ensuring that no data gets discarded that could have important implications on the research results. Therefore, the researchers conducted the process in this manner.

Phase 2: The data was then coded by looking for keywords. This was done by reading the

transcripts and simultaneously identifying the keywords and marking them.

Phase 3: A theme is something that “captures something important about the data in relation to

the research question, and represents some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set.” (Braun & Clarke, 2012, p. 63). From the codes derived from the previous phase the researchers started to construct themes/categories within the code. This was done by reviewing the coded data and identifying relationships and similarities within the codes. This reconstruction of data by coding and categorization is done to reduce the amount of data to capture the data that is the most viable for the research, this continuous data reduction focused on discarding irrelevant data and focusing on data that can portray relationships of interest (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Phase 4: In this phase the constructed themes and categories should be reviewed in relation to

the codes and the data to conclude which themes make sense in the larger picture of the data set and which should be restructured or eliminated (Braun & Clarke, 2012). The researchers therefore gathered all the found themes and went through them together to depict which ones

actually address the research question and purpose of this paper. Already here, the researchers started to draw links and relationships between different themes.

Phase 5: Here we started to map-out, define, and name different themes. We took inspiration

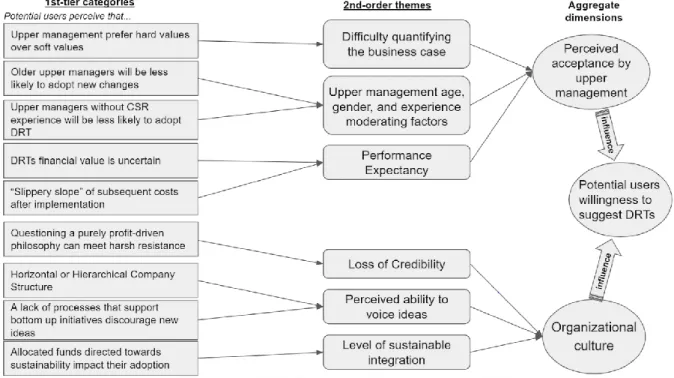

from a recommendation from Collis and Hussey (2014), to use a network to visualize and make the process easier for the researchers. According to Collis and Hussey (2014), a network is a series of labelled nodes with links between different nodes. This is done in order to present and realize relationships between the different nodes/themes. At various points, the findings were summarized, and we also started to add quotations from the data set that explains the relationships between different themes and that speaks for the themes themselves. The network and these summaries simplified the next step of the analysis process. From this network we created a data structure (see 4), to present the reader with a logical and easy-to-follow figure of how to make sense of the empirical findings where every theme is described in detail in the Findings Section.

Phase 6: According to Braun and Clarke (2012), analysis and writing is thoroughly interwoven

in qualitative research and is essential in order to create a strong and thorough analysis. Even though the writing of the analysis takes place in this phase, the analysis has been going on all throughout the previous phases as well. Here, our previous actions, such as the short summaries of analysis-thoughts, the network, and data structure were of great help.

3.4 Ethical Consideration

Throughout the entire process of this thesis, the authors have paid a high amount of consideration to trustworthiness and ethics. All participants in the study were required to sign an GDPR-form that specified the purpose of the data collection and the handling and storage of the data. Furthermore, four aspects should be considered in order to establish high trustworthiness of a research paper: Credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Shenton, 2004).

In addition to these four aspects, the researchers also considered Anonymity and Confidentiality. All participants were kept anonymous in order to safeguard the interviewees as well as to not limit the potential answers given by the interviewees which allowed the collection of more insightful empirics. Regarding confidentiality, much effort was put into making sure that the responses and data cannot be tracked back to a specific individual or

organization while at the same time displaying information of interest about the study participants.

Credibility refers to the amount of confidence the researchers can have that the data is true (Shenton, 2004). It is therefore of utmost importance when engaging in qualitative research, and especially when the data collection method is in-depth interviews. Because of the importance of credibility, and that credibility can only really be measured by the acceptance of others, the researchers made sure to be transparent with the data analysis and findings and clarified exactly what had been done and the different stages of structuring the data and empirics (see Figure 3: Data structure in Section 4).

Transferability refers to if the findings from the research can be applied to similar contexts (Collis & Hussey, 2014). In qualitative research it can be argued that transferability is never available since the findings are specific to a certain context or a small number of individuals. However, the researchers adopt the view of Shenton (2004) that transferability can be ensured to a certain extent in qualitative research. To ensure this transferability, the researchers used judgemental sampling and argued for why it was used and what criterions was considered. This allows for transferability of the findings within the particular characteristics and organizational contexts of the study.

Dependability is concerned with how stable the data is over time, this can be ensured by being highly transparent with the processes regarding the data in the study (Shenton, 2004). As described earlier in this section, the researchers adopted a high amount of transparency when presenting the findings and analysis, as well as the data collection method. It is therefore easy for other researchers to perform a stepwise replication, that is to follow the steps in detail and they can thereby repeat the work and get similar results.

Confirmability is concerned with how different independent individuals confirm the data’s accuracy. Because of this it is of high importance that the findings reflect the interviewee’s characteristics and voice, and not that of the researchers (Shenton, 2004). The researchers, therefore, spent much effort in interpreting the empirical data in the way that it is believed that the interviewee meant this was done by recording the interviews and taking notes, and interviewees were sometimes asked to clarify their statement in order to ensure that no grave misinterpretation would occur. The transcription tried to stay as close to the recording as

possible and notes were revised. The data was then coded, interpreted, and analysed according to the detailed process in Section 3.3.3.

4. Findings

______________________________________________________________________

In this section, the findings from the empirical research are presented. Firstly, we present the data structure which visualizes to the reader how the findings have been interpreted and structured. Quotes from the interview participants are stated, and the various 2nd-order themes and the aggregate dimensions are explained.

______________________________________________________________________ Data structure figure explaining the empirical findings discussed below.

Figure 3: Data structure

Before describing the aggregate dimensions, and their corresponding themes, it is necessary to briefly explain potential users' willingness to suggest DRTs. Even though our research is predicated on the perspectives of potential users, the empirical research revealed that the relationship between the potential users, who are the respondents, and upper management is of critical importance. The act of changing, through the adoption of digital reporting tools, functions through potential users’ willingness to suggest DRT to upper management. Therefore, we extrapolate on the relationship between these two actors. We find willingness to suggest is influenced by two aggregate dimensions, which in turn, are influenced by six 2nd-order themes. All findings will be related to change management in the analysis section.

4.1 Perceived Acceptance of Upper Management

This central dimension focuses on the perceived acceptance of DRTs from upper management. Across the dataset, respondents indicated the dynamic relationship between potential users and upper management, thereby signifying three 2nd-order themes: (1) difficulty

quantifying the business case, (2) upper management's age, gender, and experience as moderating factors, and (3) performance expectancy. These themes influence the relationship

between upper management and potential users, which impacts potential users' willingness to suggest DRTs.

4.1.1 Difficulty Quantifying the Business Case

Upon codifying and reviewing the interview transcripts, potential users state that it is challenging to initiate the change process when the monetary value of DRTs is uncertain. In other words, it is difficult to quantify the business case. All respondents expressed the primacy of upper management--they needed to sign off on the project because it requires significant investment:

I think this comes down to the maturity and understanding of the upper management of that specific organization because it is they who sit on the money. Every project of this scale needs funding. [Participant 8]

Several other respondents echoed the same idea:

So, the barrier I perceive is that it has to fit into the budget, but there is no budget for these kinds of initiatives that requires some form of organizational change. [Participant

1]

These two quotes are emblematic of all 8 respondents' perceptions of upper management: do digital reporting tools fit in the budget? On a similar note, the need to suggest DRT must be supported by hard values, that is, in monetary terms. Even though potential users perceive upper management to be only concerned with accounting figures, they believe soft values are tantamount, if not more significant, to profit margins:

In my sector, we have seen a decrease in the margin profit the last couple of years, and when it is like that then upper management will only prioritize changes to the organization that will yield profits, to bring the margin up again, other changes, such as CSR initiatives get down prioritized. Because these initiatives are just viewed as pure

costs on the paper since they only represent positive soft values. The most significant barrier, I believe, is just this. How do we make upper management invest in these initiatives, how do we show them that this is important? [Participant 8]

The respondent suggests that sustainability receives less priority when the profit margin decreases. Potential users perceive that DRT's value lies in soft values, and upper management prefers hard values. This discrepancy discourages them from suggesting the tool.

4.1.2 Upper Managements Age, Gender, and Experience as Moderating Factors The second theme in this dimension reveals upper management's age, experience, and gender to be influential moderating factors for potential users' willingness to suggest DRTs. As one respondent states:

If there is an older man in charge of these decisions, he is more likely to be concerned with wanting to make profits, so he can get his bonus, rather than looking at CSR initiatives. I mean, he hasn't been visiting the factories; they don't know how it really looks and doesn't realize the problem to a certain extent, and maybe don't feel that some solutions are worth spending money on or even necessary. [Participant 1]

Beyond age and gender, respondents emphasize experience; in this case, upper management's experiences visiting factories and learning about working conditions. Another interviewee underlined the impact of upper management's age and gender:

For those who are my age [40+] and older, it is always my age and older men who think sustainability is just ridiculous. Of course, not all of them, but if there is someone who has these beliefs, it's almost always them. [Participant 7]

Potential users are more hesitant to suggest the implementation of DRT's if the upper management is perceived to be old, male, and inexperienced with social sustainability issues. On the other hand, willingness to suggest is bolstered by young and experienced individuals.

I believe that younger people that graduate from University are concerned with working with an organization that they can be proud of working for therefore, they have higher demands on their employer and organization, especially when it comes to these kinds of sustainability initiatives. [Participant 8]