Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=gecd20

Early Child Development and Care

ISSN: 0300-4430 (Print) 1476-8275 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gecd20

Preschool children’s knowledge about the

environmental impact of various modes of

transport

Farhana Borg, T. Mikael Winberg & Monika Vinterek

To cite this article: Farhana Borg, T. Mikael Winberg & Monika Vinterek (2019) Preschool children’s knowledge about the environmental impact of various modes of transport, Early Child Development and Care, 189:3, 376-391, DOI: 10.1080/03004430.2017.1324433

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2017.1324433

© 2017 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group

Published online: 09 May 2017.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 2497

View Crossmark data

Preschool children

’s knowledge about the environmental impact

of various modes of transport

Farhana Borg a,b, T. Mikael Winberg cand Monika Vinterek d a

Department of Applied Educational Science, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden;bSchool of Education, Health and Social Studies, Dalarna University, Falun, Sweden;cDepartment of Science and Mathematics Education, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden;dResearch of Education and Learning, Dalarna University, Falun, Sweden

ABSTRACT

This study explored Swedish preschool children’s knowledge about the environmental impact of various transport modes, and investigated whether or not eco-certification has any role to play in relation to this knowledge. Additionally, this study examined children’s perceived sources of knowledge. Using illustrations and semi-structured questions, 53 children, aged five to six years, from six eco-certified and six non-eco-certified preschools were interviewed. Qualitative and quantitative data were analysed using content analysis and Orthogonal Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA), respectively. Findings revealed that most of the children had acquired some knowledge about the environmental impact of various transport modes, although some children were not familiar with the word ‘environment’. Although the complexity of children’s justifications for the environmental impact of different modes of transport tended to be higher at eco-certified preschools compared to non-eco-certified preschools, no statistically significant differences were found. Parents were reported to be a major source of knowledge.

ARTICLE HISTORY

Received 14 February 2017 Accepted 25 April 2017

KEYWORDS

Climate change; early childhood education; environmental sustainability; SOLO Taxonomy; sustainable development; transport modes

Introduction

Young children are affected, both physically and socially, by increased traffic, pollution and loss of green space (Davis,2015). The climate change report (IPCC,2014) claims that anthropogenic emis-sions of greenhouse gases are at the highest levels in history. Chapman (2007) pointed out that the world is obsessed with the combustion engine car, which is the second greatest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions in the transport section. Emissions from the transport sector have a nega-tive impact not only on the environment, but also on people’s health, safety and well-being (Basling-ton,2009; Kopnina & Keune,2010). Children as future global citizens are the potential victims of these consequences (Farrant, Armstrong, & Albrecht,2012). Furthermore, they will be the bearers of values and norms that shape future society. Societies have a remarkable capacity for conserving their dis-tinctive cultures (Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov,2010). Therefore, changing the values and norms of a culture, and ultimately the behaviour of the individuals within it, is a daunting task that requires adults not only to change their way of thinking, but also to convey this way of thinking to younger generations, as their attitudes are influenced by the norms and values of socializers (Eagly & Chaiken,

1993; Kopnina,2011).

© 2017 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way.

CONTACT Farhana Borg fbr@du.se School of Education, Health and Social Studies, Dalarna University, Falun 791 88, Sweden

2019, VOL. 189, NO. 3, 376–391

Wals and Corcoran (2012) argue that raising awareness about environmental hazards does not ensure a change in human behaviour or practice; rather, alternative forms of education and learning are needed to develop a capacity to act. Researchers stress that education for sustainability (EfS) can play an important role in early childhood education, because children develop their attitudes, con-ceptions and behaviour, as well as intellectual potential, during this time in their lives (Davis,2005; Pramling Samuelsson,2011). A central starting point in EfS is building on children’s participation, and viewing them as active agents and stakeholders for the future (Gothenburg Environmental Centre,2010). EfS allows people to acquire the knowledge, attitudes, values and capacity necessary to promote a sustainable future (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation [UNESCO],2016). Studies show that high-quality early childhood education is effective in developing young children’s attitudes and forming their behaviours as well as in having positive effects on chil-dren’s well-being, health and intellectual and social behavioural development – especially children from disadvantaged backgrounds (Muennig et al.,2011; Siraj-Blatchford, Taggart, Sylva, Sammons, & Melhuish,2008).

To promote sustainability within all areas of education and learning, the years from 2005 to 2014 were declared the Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (UNESCO,2005). This was followed by the 2030 agenda for sustainable development, which contains the outline of a plan of action for people, the planet and prosperity (United Nations, 2015). These issues are reflected in Swedish education policies. According to the Swedish National Curriculum for the Pre-school Lpfö98 (Rev. 2010), all Pre-schools should strive to ensure that each child develops respect for all forms of life and cares for the surrounding environment (Skolverket, 2011). In Sweden, pre-school refers to early childhood education and care for children until they start pre-school, which nor-mally is at the age of six or seven. The Swedish National Agency for Education can certify preschools with a ‘Diploma of Excellence in Sustainability’ if they apply for the recognition and meet a number of sustainability-related criteria. The criteria include the need for preschool personnel and children to work together to plan, implement, follow up and evaluate learning related to sustainable development. The Swedish National Agency for Education has certified 248 preschools for their work with EfS: these are called‘Preschool for Sustainable Development’ (Skolverket, 2014).

Preschools can also be certified with‘Green Flag’ certification by the Keep Sweden Tidy Foun-dation, which is part of the Eco-Schools programme of the Foundation for Environmental Education (FEE). The Keep Sweden Tidy Foundation supports preschools in their systematic work with EfS for active and long-term sustainable development. Participating preschools draw up action plans for their educational work, which are submitted to the foundation and evaluated periodically. About 1600 preschools in Sweden are certified with‘Green Flag’ (Keep Sweden Tidy,2016). In this paper, preschools that are certified ‘Green Flag’ or ‘Preschool for Sustainable Development’ are called ‘eco-certified’ preschools. As eco-certified preschools work explicitly with environmental and sustain-ability issues, people may expect some positive outcomes of those schools in relation to children’s learning of sustainability, compared to non-eco-certified preschools (Olsson, Gericke, & Chang Rundgren,2015).

The Swedish preschool curriculum Lpfö98 (Rev. 2010) emphasizes the importance of helping chil-dren at preschool to understand that daily living and activities can be organized in ways that can con-tribute to a better environment, both at present time and in the future (Skolverket, 2011). This is particularly relevant to Goal 13 of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development (United Nations,

2015, s. 20), which calls for taking ‘urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts’. Despite being seen as a pioneer country in the field of sustainable development, the amount of research in early childhood education for sustainability in Sweden is still limited (Ärlemalm-Hagsér & Engdahl,2015). Studies are needed to identify sustainability-related activities that are important to include in the preschool curriculum and to facilitate evidence-based policy-making. As children are the transport users of the future, there is a need to address this issue to help children ‘find new ways for sustainable transportation use’ (Kopnina,2011, p. 575).

Aim and research questions

The purpose of this study was to explore Swedish preschool children’s knowledge about the environ-mental impact of various modes of transport and to investigate whether or not eco-certification has any role to play in relation to children’s knowledge about transport modes. Additionally, this study examined children’s perceived (self-reported) sources of knowledge on this issue. The following research questions were addressed:

. How do children describe the word‘environment’?

. What do children know about the impact of cars, buses, bicycles and walking on the environment and living beings?

. What are children’s perceived sources of knowledge on the environmental impact of different transport modes?

. Is there any relationship between children’s knowledge about the environmental impact of various transport modes and the type of preschool they attend?

The term‘knowledge’ in this text does not refer to the theory of knowledge, which is often associated with the notion of truth (von Glasersfeld,1990); rather, it refers to the descriptions of children’s self-reported ideas about and thoughts and views on various modes of transport and their impact on the environment- and sustainability-related issues. The sources of children’s actual knowledge are diffi-cult to trace (Palmer, Grodzinska-Jurczak, & Suggate,2003). Therefore, the term‘perceived’ is used to indicate that the sources of knowledge are reported by the children themselves rather than there having been a search conducted for the actual sources of knowledge. This paper used the terms‘sustainable development’ and ‘sustainability’ synonymously as they both are widely recog-nized in this field.

Conceptual and theoretical framework

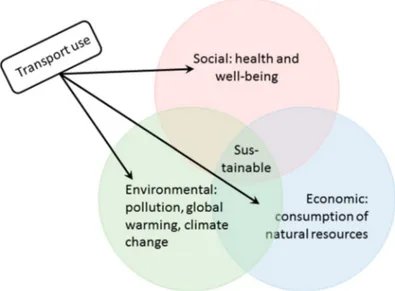

The transport use theme is directly related to environmental and sustainability issues, as it contributes to increased air pollution and carbon dioxide emissions, and furthermore has significant conse-quences for natural resources and human health and well-being (Chapman,2007). Defined as ‘devel-opment that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs’ (Brundtland,1987, p. 43), the sustainable development concept was introduced with three intertwined dimensions: environmental, social and economic. The environmental dimen-sion of sustainability includes natural resources, climate change, rural development and sustainable urbanization; the social dimension addresses human rights, gender equality, cultural diversity and health issues; and the economic dimension refers to equity, poverty reduction and market economy (UNESCO,2006). The transport use theme of this study ties with all three dimensions of sus-tainable development (seeFigure 1). Pramling Samuelsson (2011) argues that environmental issues have always been an integral part of children’s lives and that, therefore, these issues can be used as a starting point for children’s learning. Researchers have stressed the need for introducing issues related to sustainable development in early childhood education, acknowledging that children are capable of sophisticated thinking (Davis, 2005; Siraj-Blatchford, Smith, & Pramling Samuelsson,

2010). It is therefore of great importance to study how early childhood education– for example, pre-school– influences children’s perceptions of sustainability issues, including the choice of various modes of transport.

To operationalize the transport use theme for young children, it is assumed that young children, to some extent, have used different modes of transport. Preschool children often travel with their parents from home to preschool by car, bus or bicycle or by foot. Children learn about different trans-port modes by interacting with family members, friends and peers, as well as by seeing what others do (Baslington,2009). Bruner (1960) proposes that a child of any age is capable of understanding

complex information; even very young children are capable of doing so if instruction is organized appropriately. Bruner (1966) argues that young children (from the age of one to six) construct their knowledge by organizing and categorizing information through Iconic representation (image-based) in which information is stored visually in the form of images and diagrams. Bruner (1960) suggested that development is a continuous process and is not fixed in a series of stages. He also emphasizes how the social environment and social interactions are key elements in the learning process of children.

Wals (2007) argues that social learning is a powerful tool for the development of a sustainable world. Social learning is described as being ‘a transitional and transformative process that can help create the systemic changes needed to meet the challenge of sustainability’ (Wals & van der Leij,2007, p. 32). This study uses the constructivist theories, namely Bruner’s (1966)‘iconic represen-tation’ and Bandura’s (1977)‘social learning theory’, to design research questions, and to analyse and interpret children’s responses. Children are surrounded by many influential models in society, for example, parents, friends, teachers and TV characters. According to Bandura (1986), learning is a cog-nitive process which takes place in a social context. Evidence from empirical studies supports this claim (Musser & Diamond,1999; Palmer, Suggate, & Matthews,1996).

Method

This study was designed from a child-centred perspective, intended to ensure that children’s voices be heard and respected (Sommer, Pramling Samuelsson, & Hundeide,2009). Data were collected from children using closed- and open-ended questions.

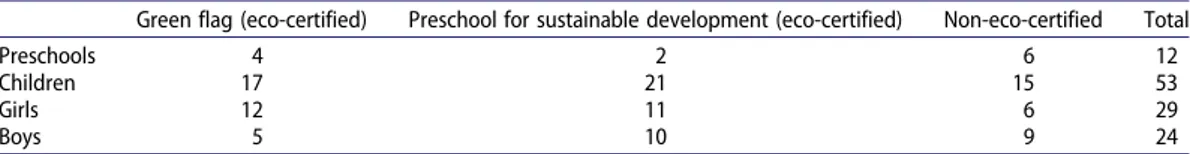

Participants and data collection

An overview of the participating children and the preschools is shown inTable 1. To be included in the study, each preschool had to have at least three final-year children. The preschools were situated in six municipalities in two counties: four non-eco-certified preschools were located in towns (≤12,000 inhabitants), four eco-certified and two non-eco-certified preschools were located in small cities (>12,000 inhabitants), and two eco-certified preschools were located in a large city (>500,000 inhabitants). The intention was to include an equal number of children from eco-certified

and non-eco-certified preschools from all areas to explore whether or not eco-certified preschool has any role to play in relation to children’s knowledge about the environmental impact of different trans-port modes. However, there are few eco-certified preschools in Sweden, and those that do exist are mainly located in cities. Therefore, an equal distribution of eco-certified preschools throughout the areas could not be achieved.

All participating children (n = 53) were between five and six years old and enrolled in the final year of preschool. Research has shown that young children are capable of being involved in research as informants and can provide valuable information (Clark & Moss,2011; Einarsdottir,2005; Sheridan & Pramling Samuelsson,2001). The reason for selecting final-year preschool children was to explore the level of their knowledge on the environmental impact of transport modes upon their completing pre-school. Giving children a voice will‘empower them to greater levels of participation and involve them as young citizens’ (Lloyd-Smith & Tarr,2000, p. 70).

A semi-structured interview instrument was utilized along with illustrations. Each child was inter-viewed individually and, if permitted by guardians and the children themselves, the interviews were audio-taped so that note-taking could be avoided during the conversation. The researcher spent time with the children ahead of the interviews, showing illustrations and playing with soft toys, the intent being that this might facilitate‘equal, confidential and open interaction’ (Kyronlampi-Kylmanen & Maatta, 2011, pp. 87–88). Guardians of 49 children granted permission for audio recording, whereas guardians of four children did not. Four children were interviewed in the presence of their teachers as per their own wishes. To facilitate understanding, the interview questions were sometimes repeated or asked in different ways. Each interview took about 5–10 minutes. All inter-views were conducted in Swedish, and most parts were transcribed and then translated into English. The interviews were carried out between February and June, 2015.

Interview instrument

With the age of the participants in mind, a set of coloured illustrations of the four modes of transport bus, car, bicycle and walking was developed (see Figure 2) and these were used as artefacts to facili-tate the interview process, because such artefacts have been found to be useful in previous studies (Clark, 2005). Given the importance of play as a natural component in children’s lives (Pramling Samuelsson & Asplund Carlsson, 2008; Pramling Samuelsson & Pramling, 2013), the interviewer (first author) used a cuddly puppet, some toys and a special sitting mat with a picture of two puppies to initiate a friendly and informal conversation with the child. The cuddly puppet (a teddy bear that was named Kim) was used for asking children questions in a way that made as though the children were Kim’s friend. For example, instead of asking a child a question, they were told that‘Kim is curious (wants) to know what the word environment means. She has heard the word but does not really understand what it means. Would you like to tell Kim what “environment” means?’ By using this question, it could be determined whether or not the child knew the word ‘environment (miljö)’. If the word ‘environment’ appeared to be unknown to the child, then the inter-viewer added the word‘nature (natur)’. If both words seemed to be unknown to the child, the sub-sequent questions were asked differently using examples of trees, flowers, birds, animals and people. The children were asked‘How good is it [for environment/nature/trees, flowers, birds, animals or people] if someone who lives close to the preschool goes to preschool by [transport mode]?’ with the four Likert-type response options ‘Very good = 3’, ‘Good = 2’, ‘Quite good = 1’ and ‘Bad = 0’.

Table 1.Overview of participating children and preschools.

Green flag (eco-certified) Preschool for sustainable development (eco-certified) Non-eco-certified Total

Preschools 4 2 6 12

Children 17 21 15 53

Girls 12 11 6 29

This was followed by an open-ended question:‘Why is going by [transport mode] [response option selected by child] for the [environment] if someone lives close to the preschool?’ Finally, the children were asked where they had learnt about this.

Pre-testing

The wording of the questions, appropriateness of illustrations, interview techniques and duration were pre-tested with eight children, aged five to six years, at a non-eco-certified preschool, which was not included in the main study. The pre-test results showed that the term ‘environment (miljö)’ was unknown to most of the children; rather, they used the word ‘nature (natur)’. The children were also better acquainted with the word‘day-care centre (dagis)’ than with ‘preschool (förskola)’. These findings were considered in the final version of the interview questions. The use of coloured illustrations, a cuddly puppet, some toys and a sitting mat with pictures of puppies was found to be helpful in creating a friendly atmosphere during the pre-testing. The face validity of the instrument was assessed by the authors and an external researcher.

Ethical considerations

This study adheres to the relevant ethical codes and guidelines that are applicable when research is being conducted on children’s perspectives (Lindsay,2000). An ethical vetting was sought from the Regional Ethical Board in Umeå, Sweden, and the study was conducted after the board granted ethical approval. Informed consent to participate voluntarily in the interviews was obtained from the guardians and the children. Confidentiality was taken into consideration while the study was being conducted. Children’s participation was voluntary and could be discontinued at any time without any reason being given. The integrity of participants was taken into consideration while con-ducting the study– for example, by anonymizing all data once the links between data from the differ-ent sources had been established.

Data analysis

A content analysis was performed with the children’s interview data to gain a deeper understanding of the phenomena. After this, the children’s responses were quantified and subjected to statistical

analysis to discern differences between eco-certified and non-eco-certified preschools with regard to children’s knowledge about the environmental impact of transport modes.

Qualitative data analysis

A content analysis of children’s responses was conducted to describe the patterns and trends in com-municative content (Weber,1990). Children’s interview data were read and re-read as a means of familiarization, and notes were kept of interesting patterns, inconsistencies and contradictions within and between individuals and groups (Hammersley & Atkinson,1983). The data were coded and categorized starting with small samples of text and then with the whole text. The categories were then examined to find relationships and links as well as to find the overarching categories or sub-categories.

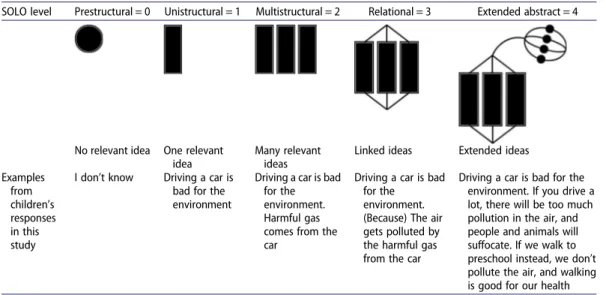

To systematically categorize, classify and analyse qualitative data, the five levels of Biggs and Collis (1982) Structure of the Observed Learning Outcomes (SOLO) Taxonomy were used. The levels include the prestructural level (a student misses the point), the unistructural level (a student has a simple idea or carries out a simple task), the multistructural level (a student has several ideas, but the relationship between them is missing), the relational level (a student links or connects the ideas) and the extended abstract level (a student has extended ideas and can generalize or create a new understanding). The SOLO Taxonomy has been used to measure cognitive learning outcomes and understanding in various subject areas among elementary and high school students (Biggs & Collis, 1982; Chan, Tsui, Chan, & Hong, 2002; Winberg & Berg, 2007). For preschool children, the five levels of the SOLO Taxonomy have been adapted with‘no relevant idea (prestructural)’, ‘one relevant idea (uni-structural)’, ‘many relevant ideas, but no link (multistructural)’, ‘linked ideas (relational)’ and ‘extended ideas (extended abstract)’ (Hook, Wall, & Manger,2015). Examples of how the SOLO Taxonomy is used in this study are provided inTable 2.

The SOLO Taxonomy classifies‘learning outcomes in terms of their complexity, enabling us to assess students’ work in terms of its quality not of how many bits of this and of that they got right’ (Biggs,2016). According to Pam Hook (personal communication, February 7–24, 2016), an indi-cator of a relational learning outcome for an early learner is when a child explains‘why’ by using ‘because’ or ‘so that’. Hook uses a ‘double because’ as an indicator of extended abstract

Table 2.Operationalization of the SOLO Taxonomy for analysing children’s justification for the environmental impact of various transport modes.

SOLO level Prestructural = 0 Unistructural = 1 Multistructural = 2 Relational = 3 Extended abstract = 4

No relevant idea One relevant idea

Many relevant ideas

Linked ideas Extended ideas Examples from children’s responses in this study

I don’t know Driving a car is bad for the environment

Driving a car is bad for the environment. Harmful gas comes from the car

Driving a car is bad for the

environment. (Because) The air gets polluted by the harmful gas from the car

Driving a car is bad for the environment. If you drive a lot, there will be too much pollution in the air, and people and animals will suffocate. If we walk to preschool instead, we don’t pollute the air, and walking is good for our health

understanding. The example inTable 2‘ … walking is good for our health’ shows that the

respon-dents’ ideas are extended into a new context.

Quantitative data analysis

The SOLO scores of children’s justifications for the environmental impact of various transport modes and their responses to the closed-ended questions were subjected to Orthogonal Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA, Eriksson et al.,2006). OPLS-DA is designed to identify differ-ences between two entities that are characterized by many variables. In this paper, the‘entities’ were eco-certified and non-eco-certified preschools, while the SOLO scores of children’s descriptions of environmental and sustainability issues and responses to close-ended questions were used as ‘characteristics’ of the preschools. Variable Importance for Projection (VIP) values were used for deter-mining the relative importance of each ‘characteristic’ with regard to describing the differences between the two types of preschools. Although there is no consensus on how to best compare the relative importance of the characteristics when multicollinearity is present, as is the case here, their relative loadings on latent factors, that is, linear combinations of original variables, in the pre-diction model have been argued to provide good estimates (Johnson,2000). VIP values build on this idea and have been shown to perform well for many types of data sets (Chong & Jun,2005; Galindo-Prieto, Eriksson, & Trygg,2015).

Wilcoxon 2-sample rank sum tests were conducted to investigate any differences between eco-certified and non-eco-eco-certified preschools with respect to the individual aspects of the children’s knowledge of the transport issue, and to give a sense of the level of their knowledge about these aspects.

Results and discussion

The results of the content analysis of children’s responses are presented and discussed in three sec-tions, each related to a specific research question, which is followed by the results and discussion of the comparison of the eco- and non-eco-certified preschools in relation to children’s knowledge about the environmental impact of various transport modes.

Children’s description of the word ‘environment’

About half (49.1%) of the children described the word‘environment’ as their world, their home or a place where all people can live. They considered forest, flowers and grass to be part of the environ-ment. Their descriptions were related to personal experiences, emotions and values associated with their liking and disliking, where expressions were frequently mixed with a sense of responsibility towards Earth and all living creatures on it. One child responded that the environment is a place outside‘ … where people should not throw any rubbish or pieces of glass. Animals can eat them and get problems or pain in their tummies. People should pick up rubbish and put it in the rubbish bin’ (Child #43). This finding is consistent with previous studies in which children’s emotions, values and understanding were integrated into their expressions of sustainability issues (Alerby,2000; Manni, Sporre, & Ottander,2013). Findings in Alerby’s (2000) study showed that children frequently described environmental issues as either good or bad for the world and then they shared their ideas about what to do to protect the environment.

A few (3.8%) children connected the cause and effect of human acts on the environment, such as ‘It [environment] is a place where we live. People should not make the environment dirty and should not throw rubbish into in the sea because then fish will die’ (Child #39). About one-third (34.0%) of the participating children did not recognize the word environment or nature. One might expect that a final-year preschool child would have come across and be familiar with the words environment and nature because the Swedish preschool curriculum Lpfö98, (Rev. 2010) emphasizes issues related to the environment and sustainability (Skolverket,2011).

Transport modes and their impact

Children’s responses about the environmental impact of different modes of transport were coded, categorized and grouped under two sub-headings: Car and Bus as Transport Modes, and Bicycle and Walking as Transport Modes, respectively.

Car and bus as transport modes

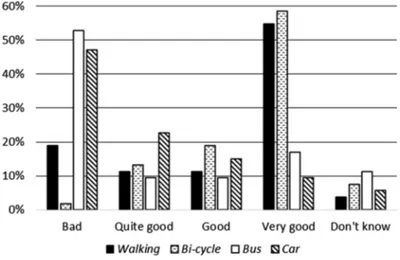

About half (47.2%) of the children reported that travelling by car was harmful for the environment: see Figure 3. In general, the children seemed to know that harmful gases from cars and buses cause air pollution, which they could relate to the extinction of life and damage to Earth. One child argued,

Driving a car is bad, because a car emits a lot of harmful gas. Walking is very good, then you don’t emit a lot of exhaust gas or you don’t fall on the ground [as one could fall from a bicycle]. That is why walking is very good for the environment. People may inhale harmful gas and can get sick. Trees can become sick. Cycling is good. But people can fall from the bicycle and get hurt. I ride a bicycle with training wheels. Travelling by bus is not that good either. I like cars, but people get exhaust gas from cars. (Child #2)

About half (52.8%) of the children viewed buses as being environmentally unfriendly modes of trans-port, whereas 16.9% of the children responded that travelling by bus was very good for the environ-ment, at least to some extent. One child explained,

Travelling by bus is good, because there are seats for many people. When you walk, then you just walk. Many people can travel together on a bus and the bus can take them to school. You can also ride a bicycle or sit on the back seat of a bicycle. When I grow up, I will learn how to ride a bicycle. There are only four seats in a car, but when you travel by bus, there are seats for many people. (Child #43)

Here, the child’s argument in favour of travelling by bus showed that the child had knowledge about public transport, where many people could travel together. Thisfinding is similar to the findings of Baslington’s (2009) study, where children responded in favour of public transport. Children’s justifica-tions were often based on their likes, dislikes, comforts, personal experiences, as well as fascination for cars and their speed. One child stated,

Travelling by bus is not fun either, because then you must wait for the bus. Then people get hungry and you don’t have anything to eat. You should get at least a glass of water while waiting for a bus. (Child # 39)

A few children were able to associate the impact of the excessive use of cars and buses with the econ-omic dimension of sustainability and the over-consumption of natural resources. One child stated that‘if you drive a lot, then the fuel will run out’ (Child # 5). Both bus and car were generally con-sidered to be harmful modes of transport: seeFigure 3. The findings indicate that Swedish preschool children seem to be, at least to some extent, environmentally aware at an earlier age than the chil-dren in the study by Kingham and Donohoe (2002). Their study on the perceptions of transport use in England found that children had no environmental awareness before 10 years of age. One possible explanation for this could be that general awareness about environmental issues has increased over the past decade. Another explanation could be that the Swedish National Curriculum for the Pre-school Lpfö98, (Rev. 2010) emphasizes environmental issues in early childhood education, which might have had an effect on children’s comprehension levels (Skolverket,2011).

To some extent, the children’s responses were related to environmental, social and economic dimensions of sustainability, such as air pollution, emission of exhaust gas and carbon dioxide, green-house effect and limited natural resources, and they connected the impact of using various transport modes with people’s health, well-being and safety issues, which are challenges for global sustainable development (UNESCO,2006).

Bicycle and walking as transport modes

Cycling and walking were frequently mentioned as being environmentally friendly and zero-emission transport modes. The children’s views are summarized inFigure 3. Cycling was reported as being very

good for the environment and for one’s health by just over half (58%) of the children, because ‘ … it is a way of doing exercise. Driving a car so much is not good for the environment. Harmful gas comes out from the car, the environment gets full of smoke and we can inhale harmful gas’ (Child #12). These findings are similar to those from a pilot study carried out with eight children from a non-eco-certified preschool where children reported that walking and riding bicycles are the most envir-onmentally friendly modes of transport (Borg,2015). These results are also consistent with the find-ings reported by Baslington (2009) regarding the perception and attitudes of children towards transport modes. Hardly any (1.9%) of the children viewed cycling as being bad for the environment; rather, the results indicate that many preschool children liked cycling and considered it exciting, although they were yet to learn how to ride a bicycle safely.

About half (54.7%) of the children opined that walking was very good for one’s health and the environment:

… because then you use your legs. If you walk, then you don’t emit any harmful gas. People can rest a bit when they travel by car or by bus. I don’t know so much about cycling, because I cannot ride a bicycle. (Child # 23)

Nevertheless, some (20.8%) children considered walking to be bad for the environment. Their justi-fications were related to personal comforts, sore legs, and the risk of accidents, as well as to what they had heard from adults. For example, a child stated that‘walking makes people tired and that’s why it is not good for the environment’ (Child #31), and ‘no one wants to walk long distances. My mother says that it is good to travel by car’ (Child #8).

The majority (66.0%) of the children under six years of age could justify their views and thoughts about the environmental impact of various modes of transport, but the level of justification varied. The content analysis showed that the complexity of the justifications among the children at eco-cer-tified preschools tended to be higher compared with those at non-eco-cereco-cer-tified preschools. These findings are consistent with the study by Davison, Davison, Reed, Halden, and Dillon (2003) on chil-dren’s attitudes towards sustainable transport in Scotland. Their findings indicated that children who participated in whole-school programmes, such as eco-schools or schools that promote a healthy life-style, had a deeper understanding of these issues.

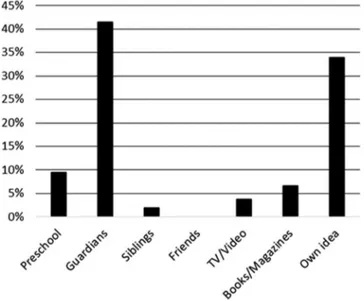

Sources of knowledge

Parents were reported as being the main sources of knowledge for the children about the environ-mental impact of different transport modes (41.5%) (seeFigure 4). About one-third (33.9%) of the children considered that they had acquired the knowledge by themselves. However, preschools

were also mentioned as being sources of knowledge by a few children (9.4%). Studies on environ-mental - and sustainability-related issues demonstrated that children, with support and guidance from their teachers, learned about different local and global issues through their participation in conversations and through being engaged in activities related to sustainability (Borg, Winberg, & Vinterek2017; Davis,2005; Lewis, Mansfield, & Baudains,2010; Mackey,2012).

Children’s knowledge about transport modes and eco-certification

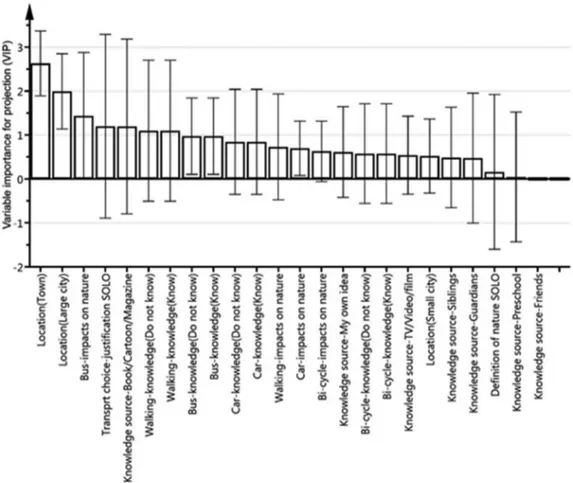

The OPLS-DA found one significant predictive component using 8% of the variation in the indepen-dent variables (i.e. the different aspects of children’s knowledge, source of knowledge and location of preschool) to predict 35% of class membership (i.e. eco-certified or non-eco-certified preschool) of the children. The relative importance (VIP) of the measured variables for predicting eco-certification of the preschools is shown inFigure 5.

The confidence intervals of the variable importance for projection values (VIP) in the OPLS-DA indi-cated that the location of the preschool was the only important variable for predicting eco-certifica-tion of the preschools (i.e. describing the differences between eco-certified and non-eco-certified preschools). Being knowledgeable (or not) about the environmental impact of bus transport, as well as the SOLO-levels of the children’s descriptions of the effect of cars on nature, was also signifi-cant– but of low importance for the prediction (Figure 5). The loading pattern of these variables, modelled together with all the other variables in the OPLS, mostly reflects the fact that the preschools located in towns were mainly non-eco-certified, while the eco-certified preschools were mainly found in large cities. Although the differences did not contribute strongly to the model, it did seem that children in eco-certified preschools were more knowledgeable about the environmental impact of buses and had higher SOLO scores on their narratives about the environmental impact of cars than children in non-eco-certified preschools. However, if the location of the preschool was removed from the model, no significant multivariate differences between eco-certified and non-eco-certified preschools were found. This indicates that the children’s knowledge about sustainability issues was not associated with the certification of the preschool.

Further evidence for this conclusion was provided by Wilcoxon 2-sample rank sum tests, which showed that there were no statistically significant differences between the eco-certified and the

non-eco-certified preschools with regard to any individual aspects of the children’s knowledge about various modes of transport, that is, the SOLO classification of the children’s descriptions of the environment (Mdn = 1 for both groups, W = 1037, p = .83) or the impact on the environment: of bicycles (Mdn = 3 for both groups, W = 881, p = .90), of walking (Mdneco= 3, Mdnnoneco= 2, W = 973, p = .40), of cars (Mdn = 0.5 for both groups, W = 927, p = .84) or of bus (Mdneco= 0, Mdnnoneco = 1, W = 805, p = .33) as a means of transport. Neither was there any significant difference in the quality of the children’s arguments for their choice of transport, assessed in terms of SOLO scores (Mdn = 2 for both groups, W = 1037, p = .83). All p values are adjusted for ties.

Large-scale studies, using nationally representative samples of sufficient statistical power, would be required to clarify whether eco-certification of preschools has a role to play in a country where the preschool curriculum already addresses sustainability issues. Such evidence is needed for prac-titioners and policy-makers to improve educational practices and facilitate policy-making (Broekkamp & van Hout-Wolters,2007).

Considering the limitations of this study, caution is called for when interpreting the findings and generalizing the results. Although the ratio of eco-certified to non-eco-certified preschools was equal, fewer children from non-eco-certified preschools participated. Thirty-five per cent of the guardians of children at eco-certified preschools consented to their children’s participation, while 20% of the guar-dians of children at non-eco-certified preschools consented. The reason for this is not known, although the reason could be assumed to relate to the guardians’ motivation and commitment to sustainable development issues; however, it could also be that the information about the study

Figure 5.Variable importance for projection values (VIP) of the independent variables used in the OPLS-DA model for characteriz-ing eco-certified and non-eco-certified preschools.

was not received by the guardians in time. During the data-collection process, it was found that infor-mation letters given to one of the non-eco preschools were not delivered to any guardians in time, which resulted in less participation on the part of the children from that preschool.

Conclusion and implications for research

This study adds to the knowledge in the fields of environmental and sustainability education and early childhood education by contributing insights into preschool children’s knowledge about the environmental impact of different transport modes from a Swedish perspective. First, by the time the children completed preschool, many had acquired some knowledge about the impact of different modes of transport on environmental and sustainability issues, despite there being children who were not familiar with the words environment or nature. Second, children perceived their parents and preschools as instrumental sources of knowledge. Third, although the complexity of the justifica-tions about the environmental impact of the modes of transport among the children at eco-certified preschools tended to be higher compared with those at non-eco-certified preschools, no statistically significant differences were found between eco- and non-eco-certified preschools.

To protect Earth for future generations, environmental and sustainability education is fundamen-tal. To effectively achieve global environmental and sustainability education targets, appropriate strategies need to be identified. To improve educational practices and to facilitate evidence-based policy-making, studies are needed to identify various factors that influence children’s knowledge, atti-tudes and behaviour regarding transport use, as well as to explore how children’s attitudes and behaviour in terms of transport and the environment are formed. This includes studies of the benefits of eco-certification systems for preschools. This is particularly relevant to Target 4.7 of Education 2030 Framework for Action (UNESCO,2015), which calls for ensuring‘that all learners acquire knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development.’

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all children and preschools that participated to this study. The authors wish to acknowl-edge Prof. John Biggs for his valuable comments on the use of the SOLO Taxonomy framework, and Pam Hook, Edu-cational Consultant and Researcher, HookED, for her generous guidance in adopting the SOLO Taxonomy for young learners for this study. The authors are also grateful to Dr Johan Borg, Lund University, Dr Hanna Eklöf, Umeå University, as well as the editors and reviewers for their constructive comments on this paper. Illustrations were made by Pauline Borg.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This work was supported by Högskolan Dalarna.

Notes on contributors

Farhana Borgis a doctoral candidate at the Post-graduate School of Educational Science at Umeå University, and a lec-turer at the early childhood teacher education programme at Dalarna University, Sweden.

T. Mikael Winbergcurrently coordinates a longitudinal international research project on how students’ motivation and epistemic beliefs develop over grade 5–11, how the characteristics of teaching contributes to this development, and how students’ motivation and epistemic beliefs affect students’ chemistry knowledge development.

Monika Vinterekis Professor of Educational Work at Dalarna University and Head of research of Education and Learning which is a research environment in educational science of about 50 researchers and more than 20 Ph.D. students from different universities are also attached to the profile.

ORCID

Farhana Borg http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4937-8413

T. Mikael Winberg http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1535-873X

Monika Vinterek http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7561-7679

References

Alerby, E. (2000). A way of visualising children’s and young people’s thoughts about the environment: A study of draw-ings. Environmental Education Research, 6, 205–222.doi:10.1080/13504620050076713

Ärlemalm-Hagsér, E., & Engdahl, I. (2015). Caring for oneself, others and the environment: Education for sustainability in Swedish preschools. In J. M. Davis (Ed.), Young children and the environment, early education for sustainability (pp. 251– 262). Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. New Jersey, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Baslington, H. (2009). Children’s perceptions of and attitudes towards, transport modes: Why a vehicle for change is long

overdue. Children’s Geographies, 7, 305–322.doi:10.1080/14733280903024472

Biggs, J. B., & Collis, K. F. (1982). Evaluating the quality of learning: The SOLO Taxonomy (structure of the observed learning outcome). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Biggs, J. (2016). SOLO taxonomy. Retrieved fromhttp://www.johnbiggs.com.au/academic/solo-taxonomy/

Borg, F. (2015). Preschool children’s understanding of transport use and environmental issues in Sweden. The 8th World Environmental Education Congress, People and Planet– how can they develop together?, Gothenburg, Sweden, June 29– July 2.

Borg, F, Winberg, M, & Vinterek, M. (2017). Children’s learning for a sustainable society: Influences from home and pre-school. Education Inquiry, 1–22.http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2017.1290915

Broekkamp, H., & van Hout-Wolters, B. (2007). The gap between educational research and practice: A literature review, symposium, and questionnaire. Educational Research and Evaluation, 13, 203–220.

Brundtland, G. H. (1987). World commission on environment and development: Our common future. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1960). The process of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Bruner, J. S. (1966). Toward a theory of instruction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Chan, C. C., Tsui, M. S., Chan, M. Y. C., & Hong, J. H. (2002). Applying the structure of the observed learning outcomes (SOLO) taxonomy on student’s learning outcomes: An empirical study. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 27, 511–527.

Chapman, L. (2007). Transport and climate change: A review. Journal of Transport Geography, 15, 354–367.doi:10.1016/j. jtrangeo.2006.11.008

Chong, I.-G., & Jun, C.-H. (2005). Performance of some variable selection methods when multicollinearity is present. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 78, 103–112.

Clark, A. (2005). Listening to and involving young children: A review of research and practice. Early Child Development and Care, 175, 489–505.

Clark, A., & Moss, P. (2011). Listening to young children: The mosaic approach. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Davis, J. M. (2015). What is early childhood education for sustainability and why does it matter? In J. M. Davis (Ed.), Young children and the environment: Early education for sustainability (pp. 7–31). Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. Davis, J. (2005). Educating for sustainability in the early years: Creating cultural change in a child care setting. Australian

Journal of Environmental Education, 21, 47–55.

Davison, P., Davison, P., Reed, N., Halden, D., & Dillon, J. (2003). Children’s attitudes to sustainable transport. Social Research Findings No.174/2003. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive Central Research Unit.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace College.

Einarsdottir, J. (2005). We can decide what to play! Children’s perception of quality in an Icelandic playschool. Early Education and Development, 16, 469–488.doi:10.1207/s15566935eed1604_7

Eriksson, L., Johansson, E., Kettaneh-Wold, N., Trygg, J., Wikström, C., & Wold, S. (2006). Multi and megavariate data analy-sis: Part I: Basic principles and applications (2nd ed.). Umeå: Umetrics.

Farrant, B., Armstrong, F., & Albrecht, G. (2012). Future under threat: Climate change and children’s health. Retrieved from

https://theconversation.com/future-under-threat-climate-change-and-childrens-health-9750

Galindo-Prieto, B., Eriksson, L., & Trygg, J. (2015). Variable influence on projection (VIP) for OPLS models and its applica-bility in multivariate time series analysis. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 146, 297–304.

Gothenburg Environmental Centre. (2010). Taking children seriously. How EU can invest in early childhood education for a sustainable future? Report on ESPD - Education Panel for Sustainable Development (Report No. 4). Gothenburg, Sweden: Centre for Environmental and Sustainability, GMV.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind: Intercultural cooperation and its importance for survival (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Hook, P., Wall, S., & Manger, R. (2015). An action research project with SOLO Taxonomy Book 1: How to introduce and use SOLO as a model of learning across a school. New Zealand: Essential Resources Educational.

IPCC. (2014). Summary for policymakers. In C. B. Field, V. R. Barros, & D. J. Dokken, K. J. Mach, M. D. Mastrandrea, T. E. Bilir, … L. L. White (Eds.), Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: Global and sectoral aspects. Contribution of working group II to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (pp. 1–32). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson, J. W. (2000). A heuristic method for estimating the relative weight of predictor variables in multiple regression. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 35, 1–19.

Keep Sweden Tidy. (2016). Håll Sverige Rent. Vi är med i Grön Flagg. Retrieved fromhttp://www.hsr.se/gf

Kingham, S., & Donohoe, S. (2002). Children’s perceptions of transport. World Transport Policy and Practice, 8, 6–10. Kopnina, H. (2011). Kids and cars: Environmental attitudes in children. Transport Policy, 18, 573–578.

Kopnina, H., & Keune, H. (2010). Health and environment: Social science perspectives. New York, NY: Nova Science. Kyronlampi-Kylmanen, T., & Maatta, K. (2011). Using children as research subjects: How to interview a child aged 5 to 7

years. Educational Research and Reviews, 6, 87–93.

Lewis, E., Mansfield, C., & Baudains, C. (2010). Going on a turtle egg hunt and other adventures: Education for sustainabil-ity in early childhood. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 35, 95–100.

Lindsay, G. (2000). Researching children’s perspectives: Ethical issues. In A. Lewis & G. Lindsay (Eds.), Researching children’s perspectives (pp. 3–19). Buckingham: Open University Press.

Lloyd-Smith, M., & Tarr, J. (2000). Researching children’s perspectives: A sociological dimension. In A. Lewis & G. Lindsay (Eds.), Researching children’s perspectives (pp. 59–69). Buckingham: Open University Press.

Mackey, G. (2012). To know, to decide, to act: The young child’s right to participate in action for the environment. Environmental Education Research, 18, 473–484.

Manni, A., Sporre, K., & Ottander, C. (2013). Mapping what young students understand and value regarding the issue of sustainable development. International Electronic Journal of Environmental Education, 3, 17–35.

Muennig, P., Robertson, D., Johnson, G., Campbell, F., Pungello, E. P., & Neidell, M. (2011). The effect of an early education program on adult health: The Carolina Abecedarian Project randomized control trial. American Journal of Public Health, 101, 512–516.

Musser, L. M., & Diamond, K. E. (1999). The children’s attitudes toward the environment scale for preschool children. The Journal of Environmental Education, 30, 23–30.doi:10.1080/00958969909601867

Olsson, D., Gericke, N., & Chang Rundgren, S. N. (2015). The effect of implementation of education for sustainable devel-opment in Swedish compulsory schools– assessing pupils’ sustainability consciousness. Environmental Education Research, 1–27.doi:10.1080/13504622.2015.1005057

Palmer, J. A., Grodzinska-Jurczak, M., & Suggate, J. (2003). Thinking about waste: Development of English and Polish chil-dren’s understanding of concepts related to waste management. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 11, 117–139.doi:10.1080/13502930385209201

Palmer, J., Suggate, J., & Matthews, J. (1996). Environmental cognition: Early ideas and misconceptions at the ages of four and six. Environmental Education Research, 2, 301–329.doi:10.1080/1350462960020304

Pramling Samuelsson, I., & Asplund Carlsson, M. (2008). The playing learning child: Towards a pedagogy of early child-hood. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 52, 623–641.doi:10.1080/00313830802497265

Pramling Samuelsson, I. (2011). Why we should begin early with ESD: The role of early childhood education. International Journal of Early Childhood, 43, 103–118.doi:10.1007/s13158-011-0034-x

Pramling Samuelsson, I., & Pramling, N. (2013). Orchestrating and studying children’s and teachers’ learning: Reflections on developmental research approaches. Education Inquiry, 4, 519–536.

Sheridan, S., & Pramling Samuelsson, I. (2001). Children’s conceptions of participation and influence in pre-school: A per-spective on pedagogical quality. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 2, 169–194.

Siraj-Blatchford, J., Smith, K. C., & Pramling Samuelsson, I. (2010). Education for sustainable development in the early years. Göteborg: World Organization for Early Childhood Education.

Siraj-Blatchford, I., Taggart, B., Sylva, K., Sammons, P., & Melhuish, E. (2008). Towards the transformation of practice in early childhood education: The effective provision of pre-school education (EPPE) project. Cambridge Journal of Education, 38(1), 23–36.

Skolverket. (2011). Curriculum for the Preschool Lpfö98, Rev. 2010: The Swedish National Agency for Education. Stockholm: Author.

Skolverket. (2014). Utmärkelsen skola för hållbar utveckling. Retrieved from http://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/miljo-och-halsa/hallbar-utveckling/utmarkelsen

Sommer, D., Pramling Samuelsson, I., & Hundeide, K. (2009). Child perspectives and children’s perspectives in theory and practice: International perspectives on early childhood education and development. London: Springer Science & Business Media. Vol. 2.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). (2005). UN decade of education for sustainable development 2005–2014. Paris: Author.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). (2006). Framework for the UNDESD inter-national implementation scheme: United Nations decade of education for sustainable development (2005–2014). Paris: Author.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). (2015). Education 2030: Incheon declaration and framework for action: Towards inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning for all. Author. Retrieved fromhttp://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002432/243278e.pdf

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). (2016). Education: Education for sustainable development. Author. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/en/education/themes/leading-the-international-agenda/education-for-sustainable-development/

United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Author. Retrieved from

http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E

von Glasersfeld, E. (1990). Chapter 2: An exposition of constructivism: Why some like it radical. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education. Monograph, 4, 19–210.

Wals, A. E. J. (Ed.). (2007). Social learning towards a sustainable world: Principles, perspectives, and praxis. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic.

Wals, A. E. J., & Corcoran, P. B. (2012). Learning for sustainability in times of accelerating change. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic.

Wals, A. E. J., & van der Leij, T. (2007). Introduction. In A. E. J. Wals (Ed.), Social learning towards a sustainable world: Principles, perspectives, and praxis (pp. 17–32). Wageningen: Wageningen Academic.

Weber, R. P. (1990). Basic content analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Winberg, T. M., & Berg, C. A. R. (2007). Students’ cognitive focus during a chemistry laboratory exercise: Effects of a com-puter-simulated prelab. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 44, 1108–1133.doi:10.1002/tea.20217