Sidetracks in remote digital

teaching

Facilitating a sense of presence, closeness and

immediacy in times of physical distancing

Alison Thomas

Interaktionsdesign Bachelor

22.5HP

Spring term 2020

Abstract

With the aim of designing tools, processes and means to support secondary school teachers in maintaining a sense of presence, closeness and immediacy when interacting with their pupils remotely in rapidly appropriated digital learning environments due to Covid-19, this thesis examined the meaning, importance and possibilities of creating a sense of presence, closeness and immediacy in remote digital teaching.

The process was based on research for design, encompassing literature study, field research and methods of interaction design to reach conclusions on meaningful tools, processes and means of supporting secondary-school teachers in remote digital teaching.

Main findings unveiled a sense of presence as a prerequisite for closeness and immediacy and real-time video lessons as the main approach to remote digital teaching, potentially creating an illusion of presence, closeness and immediacy due to pupils’ choice of black screens and muted microphones. Potentially meaningful approaches to achieving a sense of presence, closeness and immediacy identified in this thesis include the use of digital representations, representational correspondence and the concept of testimony in designing for a sense of presence, closeness and immediacy in remote digital environments.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I would like to thank all participants of interviews and the online survey for dedicating time and wisdom to this project. Caroline Ulvsand at Grundskoleförvaltningen in Malmö for believing in my research and sharing contacts. Jim for being a constant source of inspiration and critical discussions. My supervisor Elisabet Nilsson for lending her all-embracing support during the process, throughout all ups and downs and for putting up with my extensive word count. And most importantly, I want to thank my family for supporting me and helping me see this thesis through to the end during this strange year of 2020 that had all our lives turn upside down. Thank you Linus for being who you are.

Table of Contents

Abstract ... 2 Acknowledgements ... 3 Table of Contents ...4 1 Introduction ... 7 1.1 Aim ... 8 1.2 Research Questions ... 8 1.3 Contribution ... 8 1.4 Delimitations ...9 1.5 Ethical Conduct ...91.6 Structure of the thesis ...9

2 Background and related work... 10

2.1 The development towards the digitalisation of Swedish schools ... 10

2.2 The impact of Covid-19 on the digitalisation of schools ... 11

2.2.1 The impact of Covid-19 on teachers ... 11

2.3 Adapting teaching practice for digitalisation ... 12

2.3.1 Changing teaching practice through technology integration . 12 2.3.2 Pedagogical responsibility and digital teaching materials 10 years later... 15

2.4 The role of interaction design in a learning context ... 15

2.4.1 A framework for interactions in a learning context ... 16

2.5 Related work ... 16

2.5.1 The Virtual Auditorium... 17

2.5.2 Tangible interaction in the context of learning ... 17

2.6 Criteria for designing effective technology integration in remote digital teaching ... 18

3 Methods ... 19

3.1 Research for design ... 19

3.2 Double Diamond design process ... 19

3.3 Literature Study ... 20

3.4 Ethnographic research ... 20

3.4.2 Research in a Facebook group ... 21

3.4.3 Online survey ... 21

3.5 Visual data analysis through affinity diagrams ... 21

3.6 Prototyping ...22

3.7 Remote usability testing inspired by Contextual Inquiry and Remote Evaluation ...22

4 Design Process ...23

4.1 Ethnographic research ...23

4.1.1 Semi-structured interviews ...23

4.1.2 Insights from a Facebook group ... 27

4.1.3 An online survey ... 28

4.2 Design opportunities derived from insights ...34

4.2.1 Remote ensemble playing in music lessons ...34

4.2.2 Sidetracks ... 35

4.2.3 Displaying availability in remote digital teaching ...36

4.2.4 Deciding on the design opportunity ...36

4.2.5 Opportunity statement... 37

4.3 Ideation ... 37

4.3.1 Brainstorming ... 37

4.3.2 Sketching ... 38

4.3.3 A physical paper prototype ... 42

4.3.4 Iteration 1 ... 44

4.4 Digital Prototyping ... 46

4.4.1 Puzzle pieces as a display of participation ... 47

4.4.2 Monitoring a class discussion ... 48

4.5 Usability Testing of the digital prototype ... 49

4.5.1 Remote usability testing with Diane ... 49

4.5.2 Usability testing with Jim ... 50

4.6 Requirements for iteration ... 51

4.7 Final Design ... 51

5 Discussion ... 54

5.1.1 Adaptation of design methods due to the circumstances around

Covid-19 ... 55

5.2 Main findings on remote digital teaching in regard to technology integration, meaningful pupil outcomes and presence, closeness and immediacy ... 56

5.2.1 Findings from literary background research on technology integration during a pandemic ... 56

5.2.2 Towards meaningful pupil outcomes with support from representations ... 58

5.2.3 Insights regarding the relation between presence, closeness and immediacy in remote digital teaching ... 58

5.3 The final design and its approach towards the findings ... 60

5.4 Future work ... 61

6 Conclusion ... 61

Reference list ...63

Table of figures ... 64

Appendices ... 67

Appendix A: The survey ... 67

Digital platforms and tools prior to Covid-19 ... 67

New tools and applications due to Covid-19 mandated changes ... 69

Current approaches to teaching under Covid-19 mandated changes ....70

Reasons for approaches to teaching during Covid-19 mandated change ... 71

Advantages of digital teaching ... 74

Training for digital teaching ... 75

Self-confidence and assessment in digital teaching ... 76

Interactions, actions and reactions in the physical classroom ... 78

Characteristics of physical teaching and their implementation in digital teaching ... 78

1 Introduction

“The humanity of the relation of teacher and learner is a precious thing, not just because it is a source of inspiration, but because it is central to the idea of what it

is to love knowledge as one finds it expressed in the person of another.” (Bakhurst, 2020).

During the sudden transition to remote digital teaching due to limitations that the outbreak of Covid-19 has brought to societies around the world, a broad set of challenges have appeared. The trend of digitalisation that has been ongoing for several years in Europe, and thus also in Sweden (Heintz et al., 2017), suddenly became a hands-on must for teachers since secondary schools and higher education institutions closed their buildings for pupils and students and decided to transition rapidly into remote digital teaching. Teachers and pupils alike transitioned from a two-way physical and in-person communication, described by Bakhurst (2020) as immediate, dialogical transaction of knowledge, to an extreme one-way communication, which makes it difficult for teachers to follow their pupils’ progress (Olsson, 2020). The physical distance in remote digital teaching creates challenges for teachers and pupils, often resulting in a feeling of disconnectedness in spite of digital connection. The problems at hand include technical difficulties and limitations, a lack of training, difficulties in meeting the needs of pupils with learning disabilities and a rise in mental health issues in teachers and pupils. As described by a Swedish teacher (Olsson, 2020), their profession in general is extremely good at reading pupils’ expressions, catching reactions - judging their level of attention and their ability to understand. Currently however, the teachers’ profession, based on a high degree of physical interaction, is blind sighted.

Bakhurst (2020) illustrates in his philosophical reflections on the concept of teaching and the effect of online teaching on the relation between pupils and teachers that the essentially dialogical nature of teaching and learning can be undermined by online instruction and that the loss of the precious thing that is immediate, dialogical transaction of knowledge between teachers and learners is difficult to compensate for – essentially “because it is central to the idea of what it is to love knowledge as one finds it expressed in the person of another” (p. 316). Physical presence of pupils and teachers and interactions in a classroom situation have suddenly been replaced by taking attendance digitally and in many cases letting pupils work on their own, while providing the opportunity to ask questions. Teachers are redefining their work practice while trying to adapt to the new teaching situation.

Even if there is online collaboration, pupils perceive physical presence as more authentic (Kauppi et al., 2020). While this is the case, pupils also perceive appreciation for a higher level of flexibility in their studies according to Kauppi et al. (2020). According to the Swedish minister of education, the appropriate use of digital teaching materials has the potential of supporting pupils in their development of knowledge, providing new methods for feedback and improving teachers’ working conditions (af Sandberg, 2019). If the immediate transaction of knowledge mentioned by Bakhurst (2020) however is lost in remote digital teaching due to a lack of physical presence, the question arises how the gap between physical and digital presence prominent in Swedish secondary schools during Covid-19 may be bridged. In conjunction with a meaningful adaptation of teachers’ use of digital teaching materials, tools and applications which are appropriate to the sudden change in teaching practice so that a sense of presence, closeness and immediacy may be maintained, even in remote digital teaching.

In the realm of teaching digitally during a pandemic, interaction design is one approach that has the potential of providing relief for certain aspects of the problems that arise.

1.1 Aim

The aim of this project is to design tools, processes and means that support secondary school teachers (teaching years 10 -12) in maintaining a sense of presence, closeness and immediacy when interacting with their pupils remotely in digital learning environments.

1.2 Research Questions

In order to examine the meaning, importance and current possibilities of creating and maintaining a sense of presence, closeness and immediacy in remote digital teaching – and to identify relevant design criteria, the following research questions were pursued:

• In which ways can the qualities and feelings of presence, closeness and immediacy in physical classroom settings be translated to and implemented in digital remote teaching situations?

• How can remote digital interactions support secondary school teachers in improving the sense of presence, closeness and immediacy during their lessons?

1.3 Contribution

The contribution of this thesis is aimed at secondary school teachers, providing ways of interacting closely with pupils to maintain a sense of presence, closeness and immediacy in the more or less connected environment of remote digital teaching. Developing digital interactions adapted to teachers’ needs in this extraordinary situation may aid them in

their current work practice and provide them and their pupils with a sense of presence, closeness and immediacy. In extension, the work within this thesis project may contribute to manners of meaningful digitalisation of the education sector, demonstrating how methods and approaches of interaction design can be applied in an education context.

1.4 Delimitations

Research for this thesis project focused on teachers’ perspectives and experiences of the sudden shift to remote digital teaching as they are mandated to continue working. Prototyping and usability testing involved one pupil, verifying prototypes and providing insights on their user experience; however, the focus of this project is the teachers’ experience. The stakeholder group of teachers was not limited to specific subjects, in order to identify similarities in varied experiences of remote digital teaching. However, it was limited to teachers of years 10-12, as they were mandated to conduct remote digital teaching fully in Sweden.

1.5 Ethical Conduct

This project was conducted in line with the rules on ethics and norms of research as specified by The Swedish Research Council (2017). Participants in interviews and usability testing received and signed a letter of consent which specified the conditions of participation and usage and storage of personal data. The online survey that was conducted specified anonymity of participants as well as usage of retrieved data.

Ethical concerns this project involves may include health issues inherent to the nature of remote digital teaching. The use of computers with children of all school ages, long periods of sitting down and being bound to a workplace cannot be circumvented in this setting, posing risks for teachers’ and pupils’ physical health. Furthermore, the element of an actual or impending crisis involved in the current development regarding Covid-19 can possibly even lead to mental health issues. Therefore, this project aimed at adopting a matter-of-fact manner of communicating about the circumstances with participants, not laying emphasis on the cause but on a hands-on attitude towards mastering the difficulties that teachers are currently presented with. Seeing as this project may involve working with pupils who are minors, it is specifically important to anonymise all research and documentation of such in order to abide by the rules of privacy according to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, n.d).

1.6 Structure of the thesis

This thesis begins by describing the background of digitalisation and remote digital teaching in Sweden, giving a short overview of the current situation, the history of digitalisation and pedagogical implementations. The

introduction is followed by a short description of the methods applied to fulfil the aim of this project and to answer the research questions. The insights from field research are related to relevant literature, the design process is described and illustrated, followed by a critical discussion and conclusion.

2 Background and related work

For the past years, there has been an evidential development towards digitalisation in Swedish schools. Especially the topic of digital competence has not only been introduced as a mandatory part of primary school education in Sweden, but even in most European countries (Heintz et al., 2017).

While schools abide by the new regulations from the Swedish government agency for schools1 , researchers are sceptical to the unquestioned adoption

of digital learning tools, seeing as the unreflective use of digital learning material accessible on a computer is risky because of the highly distracting environment that is the internet (Wahlgren, 2019). The right use of digital learning material however may lead to an individualisation of material and adaption to the needs of every pupil (ibid).

In order to gain an overview of the progress of digitalisation in Swedish schools, the following sections examine:

• the digitalisation process before Covid-19

• the impact that Covid-19 had on schools and teachers alike • means of evoking change in the realm of teaching

• the distribution of responsibilities

• the role of interaction design in this context • examples of related work

• and conclusively, criteria for designing effective technology integration in remote digital teaching

2.1 The development towards the digitalisation of

Swedish schools

The Swedish pedagogical magazine “Pedagogiska Magasinet” [Pedagogical Journal] (Lärarförbundet, 2019) published an in-depth issue on digitalisation only months before the outbreak of Covid-19 in Sweden. This issue illustrates a lack of research on the effect of using digital learning

1 https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/inspiration-och-stod-i-arbetet/stod-i-arbetet/organisera-distansundervisning-for-larare-och-elever, Accessed on August 3, 2020

materials (Wahlgren, 2019). Investments made into the computerisation of schools are described in the article “Vägen mot en digital skola” [The road towards a digital school] (p. 32). These investments began before 1990 and digital learning materials were integrated in 1994. Subsequently, the internet was introduced to Swedish schools. Between 1999 and 2002, information technology (IT) was integrated and in 2015, a national strategy towards further digitalisation of schools was proposed to the Swedish government. In 2019, the so-called “School digiplan” was taken to government.

According to the Swedish Central Bureau of Statistics, in November 2019 around 20 % of the Swedish population were so-called “digital natives” who have no memory of the time before the internet (2019), potentially indicating a high level of digital competence in this percentile of the population. According to the Swedish government agency for schools, the next step towards digitalisation is to be in 2022, when all national exams are to be held digitally (2019). The effect of the introduction of digital competence to Swedish schools is currently being put to test by the impact of Covid-19 on teaching, and effective strategies for remote digital teaching are yet to be developed and assessed.

2.2 The impact of Covid-19 on the digitalisation of

schools

When Covid-19 was classed as a pandemic and spread rapidly around the world in March 2020, one of the measures taken in Sweden was creating strategies for schools to adopt working and learning environments that balanced the need for distance and isolation with the need for society’s essential workers, such as health care personnel, to continue working. In Sweden, due to the recommendation to work from home if possible, universities, colleges and secondary schools closed their doors for students, pupils and often even teachers, moving their operative activities to the digital realm and appropriating learning platforms meant for physical teaching.

2.2.1 The impact of Covid-19 on teachers

Due to the outbreak of Covid-19, teachers are suddenly faced with wholly or partly exercising remote digital teaching (Evans et al., 2020). The development towards digitalisation in schools has been an ongoing process for the past years and the Swedish government agency for schools has offered hands-on crash-courses. However, previous interviews conducted in the context of this thesis revealed feelings of insufficient confidence and training in teachers towards adapting their teaching practice to government directives on digitalisation. Their digital competence does not match their content knowledge, as also seen in insights on how knowledge, confidence, beliefs and culture intersect for teachers in the context of digitalisation and a change in teaching practice (Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010).

Wiman (2020) states that teachers are “wandering in limbo in no-mans-land" as they are expected to polish their digital competence amidst this sudden development. In lack of a unified approach regarding learning platforms or digital tools, teachers experiment with different approaches, hastily providing all their pupils with lessons and appropriate digital content. Wiman describes teachers as reliable, flexible and striving to provide a feeling of togetherness. However, she states that the plans made for digital teaching cannot replace physical lessons. Teachers execute a very physical job, working with bodily expression, tone of voice, hands on shoulders, flexibility and personal adaptation of content and teaching methods to pupils’ needs (Ibid.). Physical interaction with pupils is described as a vital part of primary and secondary school education and it is questionable how it can be compensated for in remote digital teaching.

As Covid-19 progresses, teachers balance known practices with new ways of teaching – pure remote digital teaching, or blending classroom- and remote digital teaching, aiming to enable all pupils to participate. Olsson (2020) states that nearly every fifth teacher exercises blended teaching, resulting in a grey area between absence and presence in addition to a higher workload and stress level for teachers. While the Swedish government agency for schools (as cited in Olsson, 2020) does not mandate schools to provide blended teaching, teachers face the problem of integrating absent pupils remotely or getting them up to speed later. Both approaches require a higher workload at some point.

2.3 Adapting teaching practice for digitalisation

According to Evans et al. (2020), online learning facilitated mainly via internet “requires effective integration of e-learning platforms, technologies and pedagogies that should enable educators to offer new more effective and impactful learning opportunities” (p. 4). As a result, educators need to take into account methods of engaging students “in an online environment providing them with intuitive interaction” (p. 6), facilitating “social learning connections with educators and their peers” (p. 6), practicing “active facilitation and learning support” (p. 6) by the means of synchronous and asynchronous channels and “utilising appropriate smart technologies and digital learning assets that enhance the experience” (p. 6).

Derived from chapter 2.2, acquiring knowledge about appropriate technologies and methods of facilitation for remote digital teaching poses a challenge for most current in-service teachers in Sweden, adding to the administrative challenge of the sudden teaching practice change.

2.3.1 Changing teaching practice through technology integration

This section examines how a change in teaching practice may take place and which requirements need to be met in order to affect a meaningful use of technology in remote digital teaching.Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich (2010) examined technology integration in teachers’ practices and discussed literature available in 2010 according to four variables - knowledge, self-efficacy, pedagogical beliefs, subject and school culture. They propose a change in teachers’ mindsets towards the belief that teaching can only be effective when using information and communication technologies appropriately. Their comparison between teachers and other professions regarding the use of technology at work illustrates the outdated practices of teachers.

The authors propose varying degrees of change to affect meaningful technology use in modern classrooms (Ibid.). “Through the lens of the individual as an agent of change” (p. 258), they discuss necessary characteristics and qualities enabling teachers to utilise “information and communication technologies (ICT) resources as meaningful pedagogical tools” (p. 258) and manners for schools to support their staff in reaching this goal. While this literary review from 2010 is focused on changing teaching practice for the use of technology in physical classrooms, the strategies examined for evoking a change in teaching practice are highly relevant in light of the current transition to remote digital teaching in regard to a meaningful use of technology in this situation.

2.3.1.1 Knowledge change

Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich (2010) explain that teachers need to adapt their work wholly or partly to utilise technology to support learning. The adaptation of their work regards “(a) beliefs, attitudes, or pedagogical ideologies; (b) content knowledge; (c) pedagogical knowledge of instructional practices, strategies, methods or approaches; and (d) novel or altered instructional resources, technology, or materials” (Fullan and Stiegelbauer in Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010, p. 258). Fajet et al (in Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010) explain that the definition of good teaching is grounded in outdated practice and lacking the integration of technology use. Angeli and Valanides (in Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010) claim that “effective technology integration depends on a consideration of the interactions among technology, content, and pedagogy” (p. 259).

This requires teachers to gain an understanding of technology tools and their affordances in order to achieve meaningful pupil outcomes. While Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich (2010) draw upon the assumption that teacher graduates in 2010 probably are digital natives, they explain that most teachers are left to their own means regarding appropriate technological knowledge. While teachers effectively use technology in personal contexts, they often lack knowledge on integrating technology effectively in the classroom. To Coppola (in Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010), teachers need to become proficient in utilising hardware, software and strategies selecting appropriate applications to meet curricular requirements and their pupils’ learning needs.

For in-service teachers to develop their technology skills, Hew and Brush (in Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010) require the integration of technology to be content-focused with an emphasis on the following: (a) technology-related knowledge and skills, (b) pedagogical knowledge and skills regarding the meaningful use of technology and (c) technology-related classroom management knowledge and skills.

2.3.1.2 Self-efficacy change

Mueller et al. (in Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010) state that teachers proficient in meaningful classroom technology use might still lack confidence to use it. Self-efficacy - the possession of the strong, positive belief in one’s capacity and skills to achieve one’s goals (Mannila et al., 2018) - can according to Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich be obtained through positive experiences with technology – experienced in person or vicariously. The method of lesson study and sharing of success stories is described by Pang (in Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010) as effective for professional development regarding student learning outcomes and individual professional learning.

However, change towards teacher confidence ideally takes place in small doses under a long period of time seeing as sporadic experimentation is more likely to lead to success, which in turn is key to self-efficacy (Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010). Regarding the current transition to remote digital teaching however, it is questionable whether this approach to self-efficacy change is possible.

2.3.1.3 Pedagogical belief change

Teachers are described to have “strong pedagogical beliefs” (Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010, p. 275) built on classroom experiences. Hughes and Ertmer (in Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010) illustrate that teachers’ beliefs rest on personal experiences - their own experiences as pupils and as teachers, vicarious experiences - and social as well as cultural influences. Roehrig et al. describe these experiences as “very resistant to change” (in Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010, p. 275). Adopting new beliefs about teaching and learning requires teachers to understand how their beliefs convert into innovative classroom practices by observing and understanding novel practices.

2.3.1.4 Culture change

Zhao and Frank (in Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010) claim that in-service teachers’ beliefs and practices adapt to the culture of their school environment. They describe school leadership as key to teacher change. Support for teachers and a common vision for technology use is required to include technology use in the definition of good teaching. Important factors for change are (a) support in setting professional goals regarding technology use, (b) creating environments that support experimentation and innovation,

(c) including teachers in decision-making processes and (d) providing adequate ICT and expertise resources to facilitate meaningful technology integration.

2.3.2 Pedagogical responsibility and digital teaching materials 10

years later

Ten years on from Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich's literature review, the trend towards digitalisation has risen. While physical classroom interaction now involves digital teaching material, the choice of material is not unified across all schools. As defined by Pedagogiska Magasinet [Pedagogical Journal], a digital teaching material is a computer programme that is dedicated to a certain school subject and is interactive, providing feedback in order to reach a certain learning outcome. Ekström, the Swedish minister of education, stated that due to the increase in production of digital teaching materials, gaining an overview and selecting materials require a high degree of reflection and care in order to exercise pedagogical responsibility (in af Sandberg, 2019).

The responsibility for providing access to qualitative materials to pupils lies on the shoulders of the principles, while teachers are responsible for using their subject knowledge and didactic competence in order to judge whether a teaching material is appropriate (Ibid.). Used appropriately, digital teaching materials can support pupils in knowledge development, provide new methods for feedback and improve teachers’ working conditions. However, Ekström warns that the development towards digitalisation should happen in a thought-through and unified manner (in af Sandberg, 2019).

The most important thing according to Ekström is that digitalisation meets the needs of pupils, teachers and principals equally. In order to accomplish that, there is a need for a national strategy and support for schools (af Sandberg, 2019). However, when looking at the shift to remote digital teaching due to the outbreak of Covid-19, it remains questionable whether the needs of pupils, teachers and principals are met as described by Ekström.

2.4 The role of interaction design in a learning context

In the realm of teaching digitally during a pandemic, interaction design is one approach that has the potential of providing relief for certain aspects of the problems that arise. Specialising on the design of interaction between users and products, interaction design strives to “enable the user to achieve their objective(s) in the best way possible” (Teo, 2020).

Within the current development in schools, teachers are using technology that is novel to them in their teaching practice. Be it programmes for video calls, teaching materials or appropriating their schools’ learning platforms for novel uses. According to Teo (2020), interactions between users and products can involve aspects relating to “aesthetics, motion, sound,

space[...]” with a high level of similarity to user experience design which strives to “shape the experience of using a product”. While teachers adopted technology rapidly during the transition towards remote digital teaching, question remain regarding their experience of products designed for other purposes than remote digital teaching and these products’ sufficiency and satisfaction regarding teachers’ objectives.

2.4.1 A framework for interactions in a learning context

Price et al. (2013) developed a framework for empirical research of interactions in a learning context, comprising four primary parameters: (1) location, (2) dynamics, (3) correspondence and (4) modality.

Location encompasses spatial locations of digital representations such as discrete design, where input and output are separated, co-located design, where the artefact and the representation are adjacent, and embedded design, referring to a digital effect within a physical artefact. Dynamics regard the flow of information during interaction, such as effects and feedback that create causal contexts within the interaction.

Correspondence describes metaphors created in artefact representations and actions involved. It consists of four different concepts of correspondence: (a) physical correspondence - the degree of correspondence to the learning domain’s metaphor; (b) symbolic correspondence - artefacts as common signifiers and representations, removed from the original context of the artefact; (c) literal correspondence - the close mapping of physical properties to the metaphor of the object; and (d) representational correspondence - design considerations regarding the representation itself and correspondence between the representation and the artefact, including action assigned in the context. Designing meaning in representational correspondence may involve varying degrees of association, depending on the concept at hand and the interaction aimed for.

As Price’s fourth parameter, modality illustrates various aspects of the whole interaction in conjunction with the other parameters. While Price’s work is mainly targeted at invisible science concepts, parameters for interactions in a learning context are also applicable in the context of this thesis seeing as Price has a focus on digital representations. While remote digital interactions may differ from tangible interactions as described by Price, digital representations are involved and need to be considered in order to achieve a level of interaction that can facilitate a sense of presence, closeness and immediacy.

2.5 Related work

According to research on remote digital teaching preceding Covid-19, there are several approaches that may be viable in the context of remote digital teaching and creating a sense of presence, closeness and immediacy.

2.5.1 The Virtual Auditorium

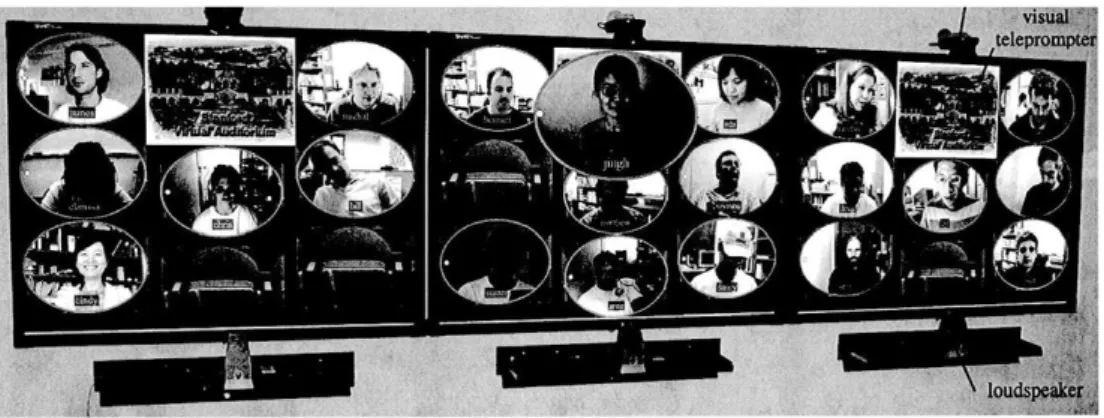

One example is the “Virtual Auditorium” (Chen, 2001), a video-conference system that supports dialog-based distance learning, displaying all participants on a tiled display and offering the possibility to establish eye-contact with pupils with the help of three cameras with pan, tilt and zoom functionality mounted on top of the display. The teacher can choose whom to look at in contrast to video-conferencing software that makes use of voice-based switching of video content. And the pupils can raise their hands by visual or keyboard interaction.

Figure 1 The Virtual Auditorium display wall (Chen, 2001).

However, Chen concludes that this software is best used by small groups of people due to technical limitations in audio and video quality. Apart from the group size, this approach seems promising as a reference in the context of this thesis, although the technology involved may be too expensive for schools. Optimally, the final design of this thesis project should involve technology that is readily at hand in both teachers’ and pupils’ homes.

2.5.2 Tangible interaction in the context of learning

Another example of potentially applicable approaches is the work of Price (2013) on tangible interaction in the context of learning. She describes the interaction with tangible artefacts as dependent on “the manipulation of physical artefacts and/or physical forms of action, offering the opportunity to build on our everyday interaction and experience with the world, exploiting senses of touch and physicality” (p. 307) and continues to illustrate that tangible technologies are highly flexible in regard to design and usability.

Figure 2 Discrete and co-located arrangements (Price, 2013)

Furthermore, Price states that research in the field of tangible technologies for learning often utilises an exploratory, technology-driven approach which is “claimed to be effective where interactive experiences with unknown (or novel) technologies are largely unexplored” (p. 313). In the context of remote digital teaching, in which the use of technology is a natural part of the process, taking on an exploratory, technology-driven approach may prove fruitful.

2.6 Criteria for designing effective technology integration

in remote digital teaching

The following design criteria for remote digital teaching to facilitate a sense of presence, closeness and immediacy were derived from background research. The design should:

• Support knowledge development • provide new methods for feedback • Improve teachers’ working conditions

• Promote pedagogical responsibility and teacher confidence • Be content-focused

• Consider the interactions among technology, content and pedagogy • Enable teachers to offer new more effective and impactful learning

opportunities • Be intuitive

• Facilitate social learning connections with teachers and peers • Enable teachers to practice active facilitation and learning support • Enhance the teaching and learning experience

• Support experimentation and innovation • Abide by physical distancing regulations

• Circumvent the grey area of absence and presence in remote digital teaching

• Enable the teachers to reach their objectives

• Consider means of representation and correspondence according to criteria of presence, closeness and immediacy

3 Methods

This chapter describes the methods applied during this thesis project.

3.1 Research for design

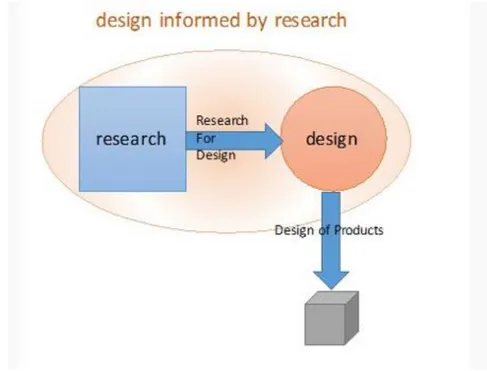

The overall approach of this thesis project was grounded in the concept of research for design (Stappers & Giaccardi, 2017) which encompasses an approach aimed at conducting research that uncovers information about the situation that the design is made for, utilising scientific and technological information as well as user studies.

Figure 3 Design informed by research (Stappers & Giaccardi, 2017).

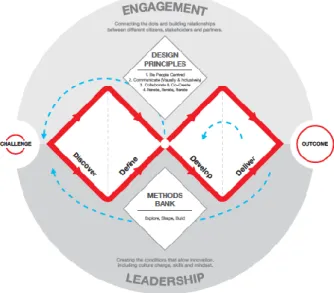

3.2 Double Diamond design process

Throughout the course of this project, the Double Diamond design process model (Design Council, 2019) was followed. This model describes a design process based on the concepts of divergence and convergence in four phases, namely “discover”, “define”, “develop” and “deliver”. In accordance with this

process model, insights were discovered, criteria for design defined, ideas and approaches to a new design developed and a final prototype delivered.

Figure 4 Double Diamond design process model (Design Council, 2019)

3.3 Literature Study

Aiming at gaining insights on the development towards digitalisation at Swedish schools, desk research was conducted (see chapter 2) with a focus on practices of remote digital teaching, recommendations from government institutions, tools and platforms, the implementation of digital remote teaching before and during the transition in Sweden and the different forms of implementation.

3.4 Ethnographic research

In order to gain insights on teachers’ working conditions from the teachers themselves, a variety of ethnographic approaches were pursued during this project. Ethnography, examining social interactions, behaviours, beliefs and perceptions to retrieve holistic insights on the subjects’ environment, offers rich insights into user experiences (Muratovski, 2016). The methods used in this work include semi-structured interviews, an online survey and collaborative brainstorming with a focus on qualitative questions.

3.4.1 Interviews

In order to gain deeper insights on teachers’ working conditions and the support available to them in this transition, semi-structured interviews were conducted with teachers from Sweden.

As a means of exploring the teachers’ experiences, needs and possibilities regarding the new development of remote digital teaching and investigating their attitude towards this development, semi-structured interviews were conducted with three teachers from different schools that are affected by the newly implemented changes and now faced with the requirement of implementing remote digital teaching.

3.4.1.1 Scenarios

During one part of the conducted interviews, the interviewees were presented with an orally described scenario in order to determine the viability of a design opportunity in relation to criteria of the Swedish national curriculum.

3.4.2 Research in a Facebook group

To gain representative insights considering the limited number of interviews, research was conducted in a Facebook group with 20000 members, founded to support teachers in Sweden in remote digital teaching.

3.4.3 Online survey

In order to gain insights on teachers’ practices, tasks and their experience of remote digital teaching despite the limitations regarding physical distancing and the teachers’ full work schedule, an online survey was conducted.

3.5 Visual data analysis through affinity diagrams

With the aim of analysing the interviews and the online survey in regard to insights from literature study, a data analysis (Muratovski, 2016) was performed through affinity diagrams. The goal of this analysis was to group the collected data into common themes, identify deficits and problems and filter the data into useful insights that lay the ground for the formulation of an opportunity statement.

Furthermore, the use of affinity diagrams was applied in order to visualise and group the insights from different teachers, analyse their situation and identify weaknesses, problems and opportunities in their process of integrating new requirements into their teaching practice. Graphs were created to visualise quantitative data from the survey and affinity diagrams were created that visualise qualitative aspects that were important to the teachers. This facilitated an overview of different tasks, processes, needs and pain points. However, originally, affinity diagrams often involve participant groups. Due to the circumstances around Covid-19, the affinity diagrams in this thesis were created without the participants of the interviews and the survey being present. Unfortunately, these participants were thus not able to “own” their data as described by the User Experience Professionals' Association (Bevan, Shor & Wilson, 2009).

3.6 Prototyping

In order to facilitate ideation and the generation and visualisation of ideas, rapid prototypes in the form of sketches were created and developed through the means of analogue and digital mock-ups that became the object of usability testing.

In combination with insights from the online survey and the interviews, experience prototypes were created in order to “emphasize the experiential aspect of whatever representations are needed to successfully (re)live or convey an experience with a product, space or system” (Buchenau & Suri, 2000, p. 425). In this case, the aim was to (re)live or convey the experience of presence, immediacy and closeness in contact with pupils while teaching in a classroom and transferring that experience to the remote digital realm.

3.7 Remote usability testing inspired by Contextual

Inquiry and Remote Evaluation

The circumstances around Covid-19 made it necessary to conduct remote usability testing. This took place in the prototyped virtual environment and the method was inspired by contextual inquiry which is a semi-structured interview method applied to obtain information about the context of use, where users are first asked a set of standard questions followed by an observation while working in their own environment.

Seeing as the original method of contextual inquiry (Herzon et al, 2010) is specifically used in the users’ own environment, the act of appropriating and modifying this method in a remote context for usability testing may be limited because the testing environment is not the subjects’ own. However, in light of the limitations due to Covid-19, this method was a valuable possibility of gaining contextual insights on digital prototypes, providing insights into experiences relating to requirements for a high-end prototype, improvements of processes, and the importance of different aspects for teachers. With this purpose, the method of contextual inquiry was appropriated in order to conduct remote usability testing and was combined with elements of the methodology of remote evaluation (Quesenbery, 2012).

4 Design Process

Figure 5 The Double Diamond design process model of this thesis

This chapter describes the design process based on the Double Diamond Process Model engaged over the course of this thesis project, beginning with insights from ethnographic research, leading to design opportunities to conclude the first part of the Double Diamond Process. Diverging into the second diamond, ideation, prototyping and user testing as a basis for iteration are described.

4.1 Ethnographic research

Based on insights from literary research, interviews and an online survey were conducted to gain further insights from Swedish teachers on experiences of remote digital teaching. Current use and usefulness of teaching platforms and communication tools appropriated during Covid-19 were explored. Further, teachers’ experiences and needs in conducting meaningful remote digital teaching and maintaining a sense of presence, closeness and immediacy in remote interactions with pupils were examined. Focus lay on teachers’ experiences of digital tools prior to and during Covid-19, classroom interaction in contrast to remote digital interaction, definitions and experience of presence, immediacy and closeness and perceptions of changes implemented due to Covid-19.

4.1.1 Semi-structured interviews

Interviews were conducted with two teachers from Malmö and one teacher from Stockholm, Sweden. To maintain anonymity, they were named Bob, Jim

and Diane. Bob is a teacher of music and Swedish at a primary school, teaching years four to seven and Jim is a teacher of music, geography and social sciences currently working at a secondary school. Diane is a secondary school teacher of digital media in Stockholm conducting real-time video lessons via Zoom. The interview with Bob was conducted before his school transitioned to blended teaching while Jim was interviewed repeatedly during the thesis process. Diane was interviewed after the spring term. All three teachers have a broad teaching background and experience of various subjects.

The interviews were summarised for the purpose of this thesis – see Appendix B for more details.

4.1.1.1 An interview with Bob

Bob experienced a lot of new input shortly before transitioning to digital remote teaching. While his school was still determining a course of action due to Covid-19, preparations for transitioning to blended teaching were made. Bob experienced this as stressful, hasty, fast-paced and messy. Having undergone merely a brief introduction to Google Meet, the modalities of blended teaching were still novel to teachers at his school. The introduction encompassed technicalities of login processes and manners of use of Google Meet. Integrating remote digital teaching into classroom teaching felt difficult for Bob, as his classes were engaged in projects and his role was to actively support and facilitate their progress, making blended teaching more complicated for Bob. He viewed group projects as more difficult to conduct in remote or blended teaching.

In music, Bob’s classes were engaged in group projects involving song-writing. A lack of access to instruments in home environments made the maintainability of this project questionable. While pupils had their own computers, they lacked software and licences for online recording tools. Conclusively, Bob was forced to adapt his term plan, handing out more theoretical tasks instead of practical projects. In blended teaching, Bob saw difficulties assessing participation abilities in self-isolating pupils. Speaking as a parent, he expressed that pupils who were at home should be treated as unable to participate.

The curricular requirement of ensemble playing surfaced as non-conductible in blended or remote digital teaching. When given a speculative remote scenario illustrating a perfect remote digital, delay-free connection in real time between pupils, Bob stated that he would be able to interpret real-time video-based ensemble groups in accordance with the curriculum. However, perfect conditions were impossible to achieve with current technical means in general and especially in schools. Therefore, Bob deemed remote digital ensemble playing as impossible even if he interpreted the curriculum as open to that.

Concluding this interview, the main challenges for Bob in the transition to remote digital teaching were

• A hasty transition to remote digital teaching

• A lack of information and training regarding digital tools and how to combine pedagogical content knowledge with appropriate digital tools

• A lack of access to instruments at home

• A lack of access to appropriate online tools for music lessons

• A lack of means to teach, assess and grade ensemble groups digitally • Interpreting the national curriculum regarding remote digital

ensemble teaching 4.1.1.2 Recurring interviews with Jim

Jim described all current contact with pupils and documentation of their progress as digital via the school’s digital platform and the learning platform service VKlass. His school allowed teachers to choose freely between methods and means of conducting remote digital lessons. To circumvent limitations in server and Wi-Fi performance, Jim provided his pupils with tasks to submit digitally in writing instead of conducting video lessons, thus utilising scheduled lesson time to answer questions in a chat application integrated in his school’s digital learning platform. In a sense, contact with pupils had become more formal and thus more structured. While pupils were free to work in their own time, the availability for questions and immediate response was vital during scheduled times, as written instructions were easily misunderstood.

To complement written contact to pupils, Jim utilised online documentaries as material for assignments, analyses and reflections. He saw advantages with pre-recorded content illustrating the depth of a problem, giving pupils the possibility to pause and return to the content if needed while increasing levels of effectiveness in teachers. The depth of a problem according to Jim was often reached in a discussion climate in the classroom.

However, in his approach to remote digital teaching, a discussion with immediate interaction was impossible. There was a lack of spontaneous, impulsive and dynamic aspects of classroom teaching such as “sidetracks” which involved going off track and spontaneously examining indirectly topic-related aspects that illustrate certain viewpoints. Going off track, zooming in or out on aspects of a topic was described as a valuable asset to classroom teaching. Reflecting on his experience as a pupil, Jim speculated that most pupils found sidetracks, often involving teachers’ personal perspectives, entertaining. Personal perspectives – relating directly to Bakhurst’s (2020) concept of testimony in teaching – potentially created a sense of closeness by letting pupils relate to, identify with and discuss teachers’ sidetracks. Discussions evoked by sidetracks had the possibility of rounding off a topic with holistic, inclusive and all-embracing understanding.

However, Jim suspected that many students appreciated a more structured and somewhat “square” manner of teaching, as it simplified the delimitation of tasks. Especially pupils with cognitive difficulties could profit from this structured approach to teaching.

Regarding his experience of teaching music, Jim reached the same conclusion as Bob – remote ensemble groups were impossible to administer. However, in contrast to Bob, his interpretation of the curriculum did not allow for remote ensemble groups. Per definition, the act of playing in an ensemble happens in real time, in the same room. Pupils are assessed on their ability of playing music together; the collaborative process of immediate action and reaction live in the same room at the same point in time, sharing a key and tempo - thus demonstrating the ability to focus on others’ and one’s own playing were described as non-circumventable factors for assessment. However, Jim stated that given the situation of teaching ensemble playing, he would wish for a solution enabling pupils to share a digital “hub” or rehearsal room, allowing him to re-interpret assessment possibilities. Concluding this interview, the main challenges for Jim were:

• Limitations in wifi network and learning platform performance • A lack of pupils’ feedback

• A risk of needing more preparation time for remote digital lessons • Discussing the depth and width of a topic in class

• Providing clarity in written assignments

• A lack of spontaneity in discussions and going “off track”

• Providing a holistic, inclusive and all-embracing understanding based on discussions

• In the role of music teacher, administering ensemble tasks • A lack of delay-free remote music teaching applications

• Interpreting the national curriculum regarding remote digital ensemble teaching

4.1.1.3 An interview with Diane

Diane conducted real-time video lessons via the video conferencing application Zoom, due to her subject’s visual nature and school-mandated decisions. The experience of remote digital teaching during the spring term of 2020, mainly facing black screens and muted microphones during lessons, was appalling and challenging. The lack of pupils’ facial and bodily expressions – keys to understanding pupils’ engagement in assignments, wellbeing and overall progress - rendered her teachers’ ears and eyes deaf and blind. While real-time video lessons gave the impression of providing closeness, black screens inhibited it. Diane’s theory on black screens named social pressure concerning pupils’ home environment and potential disruption of social media identity by their visual appearance in a digital classroom setting.

The impact of remote digital teaching on pupil motivation was not to be underestimated and in turn, their ability to show themselves visually was inhibited. Diane often utilised an application generating a random order for presentation as pupils more readily accepted computer-made decisions. Especially pupils tired of school before the transition experienced a drastic drop in motivation. Some pupils with variations of neurocognitive disorders however showed signs of coping better while others had more difficulties. The most challenging aspect of remote digital teaching for Diane was maintaining contact with pupils. Relationship-building in classroom-based teaching occurred between lessons or during natural breaks. To judge whether pupils were present behind black screens, Diane developed strategies for evoking reactions in pupils. Utilising emoji reactions in Zoom often built a bridge to other forms of interaction, e.g. switching on microphones and interacting in speech and writing. However, written interaction could occur in the middle of lectures, making it difficult to weave posed questions into the lecture flow, as opposed to oral questions that created a natural space in lectures. For reasons of self-preservation, Diane progressed from teaching via Zoom to answering questions during lessons, providing pre-recorded video tutorials for pupils to work with independently. Concluding this interview, the main challenges for Diane were

• Motivating her pupils

• Reaching out to her pupils and maintaining a relationship to them • Circumventing the problem of black screens in real-time video lessons • Being available for pupils when they needed her

• Maintaining small talk

• The lack of reading her pupils’ mood, motivation and expression by engaging her teacher’s ears and eyes

4.1.2 Insights from a Facebook group

During the first weeks of the Covid-19 pandemic, a group created on Facebook for digital remote teaching received nearly 20 000 members directly. The group aims to provide a forum for discussion, sharing of approaches and collegial support. The majority of posts in the group regard the use of various video conferencing applications, indicating a wide-spread use. One post engaged teachers in collaboratively collecting requirements from teachers regarding Google Meet (Distansundervisning i Sverige, 2020). A meaningful use required Google Meet to provide a variety of new features, indicating the appropriation of this tool to remote digital teaching. Named new features indicate that the teachers need:

• the sole right to own the meeting, being the administrator instead of the first person logging in to the lesson

• to be able to invite and exclude pupils permanently • to be able to activate and deactivate pupils’ microphones

• the sole right to record the lesson

• to be able to choose who is shown on a main screen, e.g. during pupil presentations

• easily create groups of pupils, e.g. via a drag and drop functionality, and move between the groups

• to be in charge of presentations and be able to accept when a pupil wants to start instead of pupils taking over the teachers’ presentation and shared screen

• to be able to talk to or chat with a pupil without talking to the whole class during the lesson

• an overview of all pupils’ cameras in order to see everyone and take attendance

• a permanent log of the lesson including details of the time pupils enter the lesson, all chat messages, when pupils raise their hand, hand in an assignment, or leave the lesson.

Pupils’ behaviour in video lessons was mentioned extensively. Many teachers were talking to a wall of black screens, resembling Diane’s experience. Apparently, pupils stay unseen in order to maintain privacy towards their peers, creating distance and complicating teachers’ insight into pupils’ progress and wellbeing. This suggests a need for means of maintaining the relationship with pupils even in remote digital teaching.

4.1.3 An online survey

The survey (see Appendix A) engaged 20 anonymous participants, representing a broad variety of subjects - languages, natural sciences, social sciences, aesthetic subjects and business subjects. The participants ranged from primary school teachers to secondary school teachers including one pre-service teacher student.

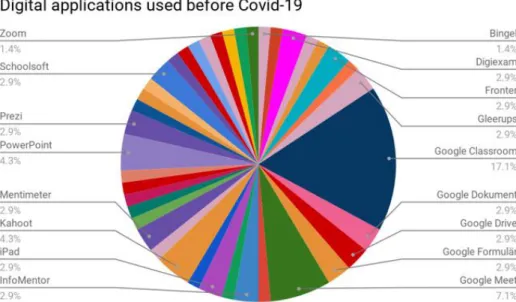

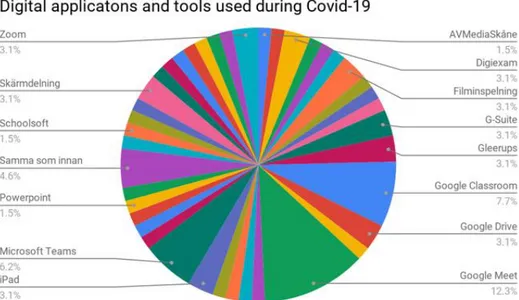

The survey showed participants using a magnitude of digital platforms, applications and tools even prior to the transition - teaching platforms, digital tools for creating content and recordings, quiz applications, communication applications, documentation applications, presentation applications, teaching material applications as well as material found online, collaboration applications, development review applications and examination applications.

Applications and tools were grouped in an affinity diagram (Fig. 6) to clarify their role in teachers’ routines. The diversity of individual participant approaches to digital tools and platforms is striking, depending partly on managerial school choices and partly on teachers’ own choices. School administrators or municipalities choose a learning platform and teachers often make their own choices regarding additional open-source programmes.

Figure 6 Affinity diagram of digital tools before Covid-19

Answers gathered in this part of the survey revealed a great variety of digital applications used regularly even before Covid-19.

Examining digital applications and tools used before (Fig. 5) and after (Fig.7) the transition to digital remote teaching, the magnitude in variety of platforms has barely changed. The focus merely shifted from learning platforms before Covid-19 to video conferencing applications after the transition. While most teachers were already using digital learning platforms before the outbreak of Covid-19, there was no unified approach regarding tools. Firstly, this points to individual school-based contracts with suppliers of software and a high degree of freedom for every teacher to employ their own choice of additional tools and applications to facilitate lessons.

Secondly, potential problems when requiring support or sharing experiences are indicated as the choice of applications varies immensely. One teacher sharing a success story with a certain combination of applications may inspire others, however the approach may not be replicable. Thirdly, it can be derived that teachers are highly flexible in adapting to pupils’ needs utilising specialised tools.

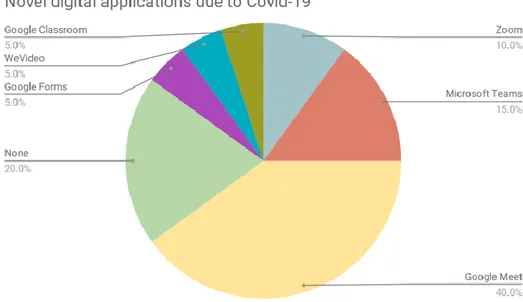

Examining applications novel to participants (Fig. 8), there are insights to be gained on previous use of digital communication applications such as Google Meet and Zoom. 10 of 20 participants however reported these kinds of applications to be novel to them which suggests a confirmation of the fact that these tools were hastily appropriated for use in remote digital teaching and may not have been used for teaching purposes by the other half of participants previously.

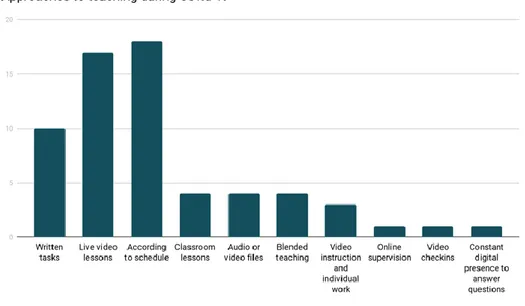

Participants practiced a multitude of approaches to remote digital teaching (Fig.9). The majority conducted video-based teaching (17 participants) for reasons of effectivity, structure, focus and support as well as maintaining the relationship to pupils - checking on their wellbeing and progress and providing them with a social context.

While 18 of 20 participants worked according to scheduled times to provide clarity, structure and routine, 10 participants provided their pupils with written assignments instead of real time video lessons to clarify the purpose of the lessons and to offer active communication and support during lessons. Participants engaging in combinations of approaches did so for reasons of flexibility and adaptability to technical issues and pupil needs.

Overall, reasons for approaches to remote digital teaching were centred around pupil needs and teacher effectiveness. Most teachers followed approaches supporting active and immediate communication with pupils, in written or live video form.

Qualitative insights on approaches to remote digital teaching (see Appendix A) indicate important factors participants strived for and related to aspects of presence, closeness and immediacy, such as:

• Closely knit contact • Clarity • Flexibility • Availability • Accessibility • Structure • Closure of lessons • Social context

• Effectivity

Participants even described that they were “sitting down with” their pupils in live video lessons, indicating an experience of presence, closeness and immediacy despite the screens dividing them.

However, circumstances of remote digital teaching evoked feelings of powerlessness and choicelessness in participants, such as school-mandated uniformity, Covid-19 and government-mandated regulations and recommendations. The participants’ choice of complementary tools may indicate a manner of self-empowerment in the situation.

4.1.3.1 Advantages of digital teaching

The main advantages of remote digital teaching identified by participants included more active contact from pupils and a rise in focused questions in the online setting – more pupils dared to ask questions. The lack of a social classroom context and inherent group pressure resulted in fewer distractions, a higher number of present pupils and a feeling of comfort and safety in pupils. Participants were able to provide more individual supervision and recorded lessons or online media provided pupils with means of gaining flexibility, focus and a thorough understanding of the content.

Antagonistically, a shift in the role of assignments was identified. In remote digital teaching, assignments had become more central and pupils’ own work became the focus of lessons, resulting in outcome-oriented teaching that was not always wanted.

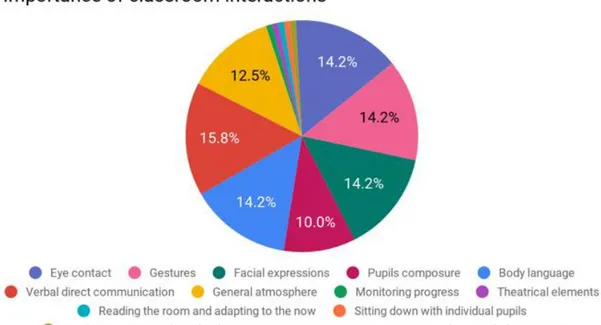

Participants described interactions, actions and reactions in the classroom that were important to them in order to read their pupils (Fig.10). In remote digital teaching, they experienced a lack of personal contact, building relationships, rapid responses, on-the-spot and one-to-one supervision, immediate reactions, physical closeness, spontaneity and the overview over actions, reactions and pupils’ level of understanding.

4.1.3.2 Participants’ definitions of the terms closeness and immediacy and conclusions on presence

Immediacy was defined as direct contact in a setting where questions appear naturally and spontaneously in conjunction with the ability to give and receive direct responses in real time – “within 5 seconds” - and thus conveying trust, priority, focus and availability.

Teachers’ definitions of the term closeness are based on availability, trust and physical presence as well as an understanding of and for pupils, pupil feedback, pursuit of common goals, focus, delay-free connection, support, motivation, praise and an unspoken agreement on responsibility and expectations in the now.

The experience of presence was mostly related to attendance of lessons during the survey and interviews. Receiving insights on the experience of presence proved difficult in direct answers. Presence seemed to be based on pupils being in the classroom or not - pragmatically a matter of taking attendance. However, the term presence was mentioned several times regarding the concept of closeness.

Figure 11 The participants' definitions of presence, closeness and immediacy in remote digital teaching

4.2 Design opportunities derived from insights

Concluding the research phase and the first diamond in the Double Diamond process, design opportunities were derived from the most prominent insights regarding a sense of presence, closeness and immediacy.

4.2.1 Remote ensemble playing in music lessons

Design opportunity 1.1: How might we design curriculum-conform means of conducting browser-based ensemble playing in remote digital teaching? Conducting remote ensemble playing in line with curricular requirements posed a problem, as identified by Bob and Jim. The curriculum for music specifies requirements for ensemble playing - here and now, in the same room, involving action and reaction while playing simultaneously and sharing key and tempo (see chapter 4.1.1). Technical limitations in schools made remote ensemble playing in remote digital teaching impossible under current circumstances. However, the need for pupils to reach the intended learning outcomes in time persisted, leading to the question how curriculum-conform means of conducting ensemble playing in remote digital teaching may be designed.

The examples (Fig. 12-14) below display research conducted to explore browser-based and virtual means of designing in this context.

Figure 13 Example of browser interaction with music

Figure 12 2D video in 3D environment

4.2.2 Sidetracks

Design opportunity 2: How might we design means that create a sense of presence, closeness and immediacy between physically disconnected pupils and teachers in a remote teaching situation?

Design opportunity 2 was based on the lack of spontaneity in discussions and “going off track” in order to provide a holistic, inclusive and all-embracing understanding of topics. Sidetracks were described as an aspect and a manner of teaching, often creating a feeling of closeness by utilising personal perspectives as grounds for discussion. In the context of remote digital teaching, this personal touch to a physically disconnected situation may have the potential of creating a feeling of closeness even in the digital realm and leads to the question how means that create a sense of presence, closeness and immediacy between physically disconnected pupils and teachers may be designed in a remote teaching situation.

Pursuing this opportunity required teacher and pupil involvement to verify the effect of sidetracks on relations between teachers and pupils. A ninth-grade pupil, questioned informally, described teacher traits regarding closeness. This pupil named structure, clarity and transparency. Closeness was created by presence during lessons and communication during breaks between and within lessons. Getting sidetracked was perceived positively by the pupil, presuming the completion of planned elements.

4.2.2.1 Sidetracks as a metaphor

Sidetracks derive meaning from diverse contexts – train and oil industries. They are defined as short tracks where trains are kept when not in use and as