Preprint

This is the submitted version of a paper published in Scandinavian Journal of Caring

Sciences.

Citation for the original published paper (version of record):

Björk, K., Lindahl, B., Fridh, I. (2019)

Family members’ experiences of waiting in intensive care: aconcept analysis

Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, : 1-18

https://doi.org/0.1111/scs.12660

Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper.

Permanent link to this version:

Review Copy

Family members’ experiences of waiting in intensive care: A concept analysis

Journal: Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences Manuscript ID SCS-2018-0262.R1

Manuscript Type: Original Article

Keyword-Area of Expertise: Critical Care, Family Care

Keyword-Research Expertise: Qualitative Approaches, Textual Analysis

Review Copy

Family members’ experiences of waiting in intensive care:

A concept analysis

Abstract

Aim: The aim of this study was to explore the meaning of family members’ experience of waiting

in an intensive care context using Rodgers’ evolutionary method of concept analysis.

Method: Systematic searches in CINAHL and PubMed retrieved thirty-eight articles which

illustrated the waiting experienced by family members in an intensive care context. Rodgers’ evolutionary method of concept analysis was applied to the data.

Findings: In total, five elements of the concept were identified in the analysis. These were: living

in limbo; feeling helpless and powerless; hoping; enduring; and fearing the worst. Family members’ vigilance regarding their relative proved to be a surrogate term and a related concept. The consequences of waiting were often negative for the relatives, and caused them suffering. The references showed that the concept was manifested in different situations and in intensive care units (ICUs) with various types of specialties.

Conclusions: The application of concept analysis has brought a deeper understanding and

meaning to the experience of waiting among family members in an intensive care context. This may provide professionals with an awareness of how to take care of family members in this situation. The waiting is inevitable but improved communication between the ICU staff and family members is necessary to reduce stress and alleviate the suffering of family members. It is important to acknowledge that waiting cannot be eliminated but family-centered care, including a friendly and welcoming hospital environment, can ease the burden of family members with a loved one in an ICU.

Keywords: Family members, Waiting, Intensive care, Critical care, Rodgers’ evolutionary method of concept analysis.

Word count: 4918 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55

Review Copy

INTRODUCTION

Waiting is a subjective experience and brings with it uncertainty (1, 2), loss of control (1) and powerlessness (2). Family members of those receiving in-inpatient hospital care have described emotions such as anxiety, fear, isolation, and loss of a sense of time related to waiting for information about their relatives (3-5). Family members have also described the waiting for a relative to receive prehospital care (6) or a transplant (7) as intolerable. Earlier analyses of the concept of waiting have described patients’ waiting as a nonspecific measure of time while waiting for care (1, 2) or family members’ experience of waiting for a relative to gain access to care (1). When a person is in a life-threatening situation and receiving care in an intensive care unit (ICU), family members, are absorbed with worries and concerns about their loved one’s condition and the risk of loss. There is a strong desire to be near the loved one (8-10) and family members sometimes have to spend weeks travelling back and forth to the ICU uncertain about the outcome of the care (11, 12). This situation entails several aspects of waiting that are unique to the ICU context. Thus, it seems important to provide a concept analysis of family members’ experience of waiting when one of them is being cared for in an ICU. We therefore, used Rodgers’evolutionary method of concept analysis (13).

BACKGROUND

According to Rodgers’evolutionary method, the attributes and definition of a concept are not written in stone but evolve and change over time. A concept analysis is thus the basis for further research and development of the concept (14). Irvin’s (1) concept analysis of waiting concluded that the definition of waiting was a dynamic, stationary and unspecified timeframe which led to uncertainty based on the personal outcomes, but which lasted only for a limited time. Critical attributes of waiting found in Irvin’s study were uncertainty and loss of control, which both patients and their family members experienced but in different ways (1). Fogarty and Cronin’s (2) concept analysis of patients waiting for health care shows that the critical attributes of the concept are that it was felt to be an unspecified time period which was individually experienced. The patient anticipated the kind of healthcare needed and experienced feelings of powerlessness and uncertainty when waiting for it to materialize (2).

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56

Review Copy

The intensive care environment affects not only the critically ill patient, but also other family members. It is characterized by a variety of stimuli from the different medical devices placed near the patient’s bed space and functioning around the clock (15). Having a loved one with a life-threatening condition cared for in the intensive care environment can be stressful and strenuous for family members and symptoms of anxiety and depression are common. There is also a risk of their developing symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (16-18), particularly if they are not given sufficient information about the loved one’s condition and prognosis (19). In the seventies Molter’s (20) research resulted in a list of ICU family members’ 10 most prominent needs. Later, following Molter’s listed needs, Leske (21) developed the Critical Care Family Needs Inventory questionnaire. Based on this questionnaire, Leske generated five main family members’ needs: to remain near the patient, to be comfortable, to receive information, to have support available and to receive comprehensive assurances (22). Information, assurance and proximity are rated the greatest needs by family members (8, 23, 24). Being able to be close to their relative can help family members to feel secure and relieve anxiety when waiting while a loved one undergoes surgery (3). Not all intensive care units have waiting rooms for family members, which can affect whether or not family members are able to be close to their loved ones (25-27). Waiting room studies show that family members have a positive experience of the waiting room if it is comfortable, inviting and close to the ICU (27, 28). In the waiting room, family members can get support from other distressed families and express the feelings which they feel they had to hide in the patient’s room (28).

ICU staff often underestimate family members’ need for honest information about their relative's treatment and status (26, 29, 30). Nurses have explained that they want to give the patient the best possible care but sometimes feel that family members can be obstructive and therefore want them to wait outside, or in the waiting room (31-33). In the studies by Engström and Söderberg (34) and Fateel and O’Neill (32) nurses reported that they did not have the time or resources to meet the needs of family members.

Patients are admitted to the ICU due to life-threatening failure of vital functions caused by injury or disease. The care period in the ICU can range from single days up to several months and,

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55

Review Copy

according to the Swedish Intensive Care Registry (SIR), approximately 10% of patients die during the ICU treatment period (35). When a patient is admitted no one knows exactly how long he/she will need to be treated in the ICU as this is obviously dependent on how his/her condition develops. This is a very trying experience for family members, with waiting constituting a central phenomenon in their daily lives during the patient's care period. An exploration of family members’ experiences of waiting in an intensive care context could lead to a deeper understanding of the meaning of the concept, thereby increasing our knowledge about a phenomenon of interest for caring science and intensive care nursing.

AIM

The aim of this study was to explore the meaning of family members’ experience of waiting in an intensive care context using Rodgers’ evolutionary method of concept analysis.

METHOD

Rodgers’ evolutionary method of concept analysis represents inductive analysis. The activities in Rodgers’ method are described in Table 1. The steps are not static and the author can work parallel with previous steps or return to them (13). According to Rodgers (13) a concept can be a word or an idea that gets its meaning through its formal use. The concept of waiting has, for example, been used in language and interactions in the social context of the intensive care environment and has in this way been shaped, learnt and developed (13). A concept analysis can define, clarify and identify a concept by compiling existing knowledge about it (36).

Insert Table 1 here.

Identifying the concept of interest

In this study the concept ‘waiting’ was chosen based on the authors’ area of interest and experience. The aim was formulated after reviewing the literature (13). A pilot search was conducted in the databases CINAHL and PubMed using concept analyses of family members’ waiting in an intensive care context as the key. Previous concept analyses have been applied to waiting in other contexts but no studies were found focusing on intensive care (1, 2). It was,

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56

Review Copy

therefore, considered appropriate to analyse the meaning of family members’ waiting in an intensive care context.

The definition of waiting according to the Oxford English Dictionary is “The action of staying

where one is or delaying action until a particular time or event” (37). The synonyms for waiting

are excited, anticipatory, agog, breathless, eager, waiting with bated breath, hopeful (37). The stated aim of this concept analysis also includes the term family members. A family member is defined as “A person who belongs to a (particular) family; a (close) relative” (37). In this study ‘family members of patients being cared for in the ICU’ refers to one or more people with whom the patient has had close relations for a long time, shares a common understanding of what closeness means and who the patient cares for and trusts (38, 39). ‘Family members’ can thus be family, relatives, parents, spouses, brothers, sisters, partners, children or close friends (40).

Identifying and choosing the setting and sample

According to Rodgers (13) the author decides which areas should be included and that only the areas of interest should be researched. The setting refers to the sort of literature included, the discipline involved and the time period investigated. Once the setting has been determined, the author must identify the sample. The sample can be selected from the chosen discipline and the published literature within that field (13). In this study the area of interest is intensive care and the literature consists of scientific articles covering the chosen context.

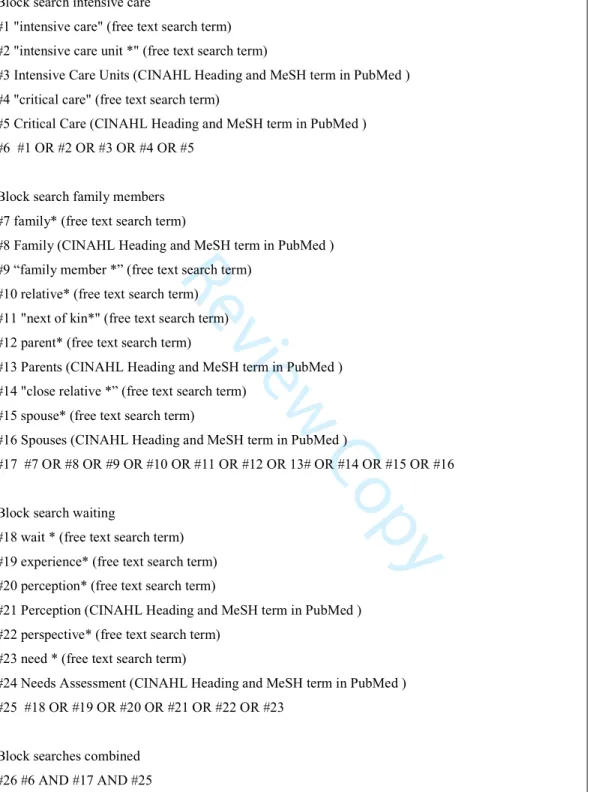

Data collection

To avoid confronting an overwhelming amount of literature, the author can select the databases they want to use for the literature search providing that the size of the sample is sufficient to reach convergence or consensus in the data (13). After consulting a librarian, the literature searches were performed systematically in the PubMed and CINAHL databases and no time limit was set. Search terms were chosen based on manual searches and the pilot search and were matched to CINAHL Headings and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms in PubMed. The various headings in the databases are for indexing articles, but the selected search terms were

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55

Review Copy

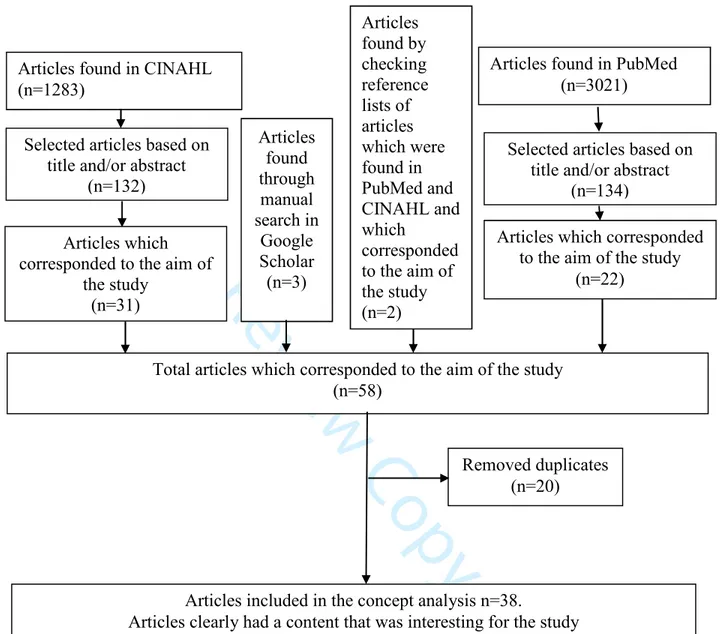

also written in free text based on the result from manual searches and the pilot search and in some cases truncation (*) was used. The search process is presented in Figure 1.

Insert Figure 1 here.

Finally manual searches were made, using various combinations of the search terms (given in Figure 1), in Google Scholar and by checking the reference lists of the studies searched in PubMed and CINAHL which corresponded to the aim of the study (Figure 1). This was done in order to obtain a material that was as representative as possible based on the aim. The inclusion criteria for the articles were that they should be written in English, be peer-reviewed and describe the family members’ experiences of waiting when a loved one was being cared for in an ICU. Based on these systematic searches 38 articles were chosen for the actual data analysis (Figure 2).

Insert Figure 2 here.

A thematic analysis was performed in order to organize the information in the literature and discover any similarities (13). The selected articles were read several times to identify meaning units (sentences, phrases and words) that described or were related to family members’ waiting in an intensive care context. The meaning units were transferred to a column, carefully examined and classified into relevant categories (13). In the reading and analysis we used Tofthagen and Fagerstrøm’s (41) questions as a tool, which are based on Rodgers’ evolutionary method (Table 2), to abstract the themes (surrogate terms and related concepts, attributes i.e. characteristics, antecedents, examples and consequences of the concept). In addition to these themes Rodgers also maintains that references must be extracted as a separate theme (13), this was also done.

Insert Table 2 here.

Ethical considerations

The Helsinki Declaration (42) and guidelines in the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity (43) were followed to ensure good practice in the research process by not distorting it,

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56

Review Copy

or stealing, plagiarizing or fabricating data. A total of 31 articles had been given ethical approval, three lacked information about approval but the reasoning presented was ethical and four articles had neither ethical reasoning in their studies nor ethical approval. Despite some articles lacking information about ethical approval the authors chose to include all articles as they presented aspects corresponding to the aim of the study.

FINDINGS

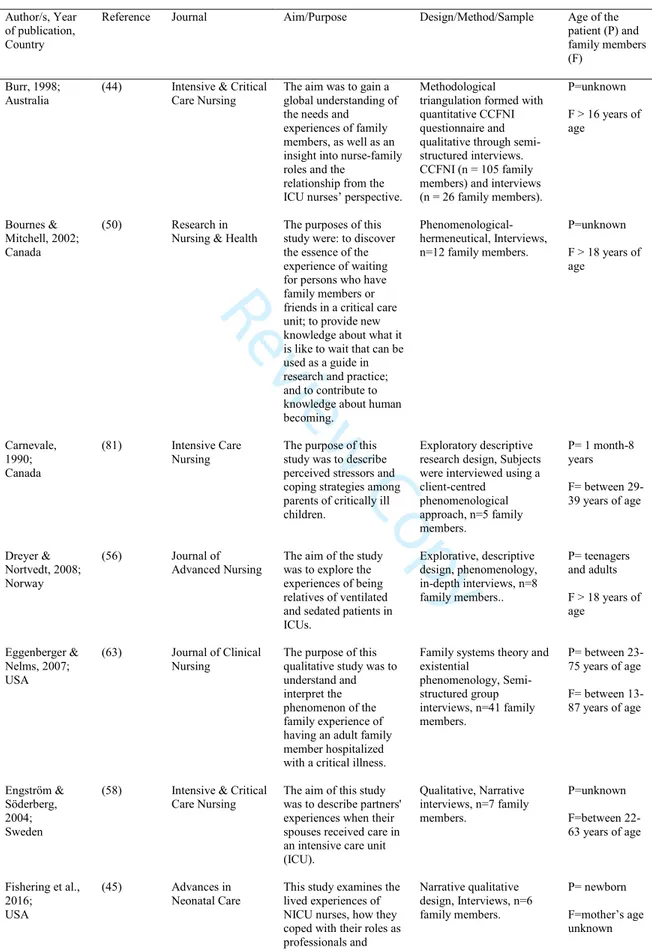

A total of 38 articles were included in the study and of these 34 were qualitative studies, three were both qualitative and quantitative and one study was quantitative but with open-ended questions. The articles were published between 1990 and 2016. In the total data set 11 studies emanated from Sweden, 10 from the USA, four from Canada, three from Denmark, two from Australia and England, and one each from Belgium, Germany, Ireland, Lebanon, Norway, and South Africa. All articles described family members’ experience of waiting when a loved one was being cared for in an ICU. In eight articles the patient was a newborn or a child (<18 years of age), in eight articles the patients were adults, six articles included both child and adult patients and in 16 articles the patient age was not given. In two studies only children were interviewed; in 25 articles the interviewees were adults, in six articles the ages of those interviewed were unknown and in five both adults and children were interviewed. The articles are presented in Table 3.

Insert Table 3 here.

Surrogate terms and related concepts

Related concepts and surrogate terms are concepts that are related in some way to the concept under examination, but do not share the same attributes (13). An example of a surrogate term and related concept in this study is “vigilance”. However, “vigilance” has a somewhat different meaning from waiting. In some of the articles included vigilance was described as family members’ watchfulness over their relative in the intensive care unit (44-50) but this concept has attributes that differ to some extent from waiting (51).

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55

Review Copy

References

Describing the concept’s references means that its applicability to different situations and events can be made clear. By identifying the references, Rodgers means identifying the situation or phenomenon when and where the concept occurs (14). The references found in this analysis are presented in Box 1.

Insert Box 1 here.

Antecedents

Antecedents are described as phenomena or events that generally occur before the concept in focus appears (14). In this study, in order for the concept to exist within the intensive care context, a person must have a life-threatening condition leading to admission to an intensive care unit and have a related person waiting or experience waiting (49, 52, 53).

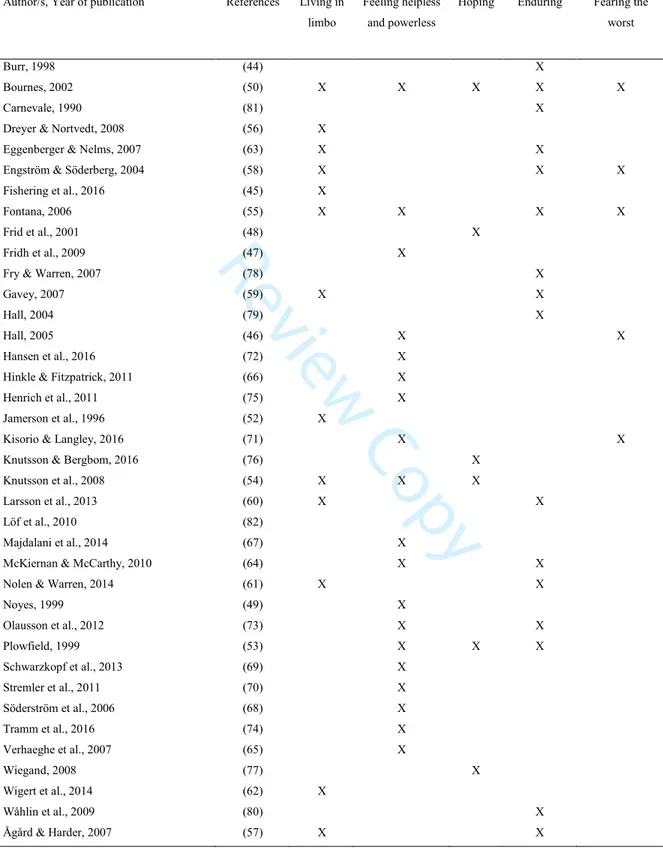

Attributes

The attributes constitute the real definition of the concept and differ from the dictionary definition that only replaces one synonym for another. The attributes create the whole of the concept based on the analysis (13). In this study the characteristic attributes for family members waiting in an intensive care context are: living in limbo, feeling helpless and powerless, hoping, enduring and fearing the worst. The characteristic attributes and their representation in the studies are presented in Table 4.

Insert Table 4 here.

Living in limbo

Having a loved one in the ICU is similar to living in limbo. Family members describe this limbo as an uncertain period, like existing in a parallel universe, shielded from reality, where time feels as if it is standing still (50, 54). In this limbo family members live in uncertainty, worrying about what will happen to their relative – whether they will live or die - and this constantly gnaws at them (50, 54-57). To relieve the suffering from being in limbo they want answers and

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56

Review Copy

information about their relative’s condition but they usually just have to wait and this waiting is stressful, difficult and remorseless. Often there are no answers to their questions, which prolongs their waiting, uncertainty and worry about their relative (45, 52, 54, 55, 58-63).

Feeling helpless and powerless

Family members feel helpless and powerless in the face of the loved one’s situation in the ICU. This is terrible for them as they cannot do anything to influence the situation, only wait for their relative to recover (50, 53, 55, 64, 65). Family members often feel neglected and forgotten when waiting for a chance to meet a physician because it takes so long (66-69). Sometimes, they are not given updates spontaneously but have to ask, which makes them feel helpless (70, 71). Instead of being near to their relative, family members are asked to wait outside the patient’s room or in the waiting room. This waiting leads to frustration and anger since they never know how long it will last. They feel powerless as the ICU staff decide when they can see their relatives (46, 47, 53, 54, 72-75). It is frustrating not to be able to occupy themselves with anything meaningful while waiting and the waiting itself serves no purpose (50, 54). Not being close to their loved one increases the feeling of powerlessness. (49, 54, 73).

Hoping

Family members wait for improvement in their loved one’s condition, even when the outlook for this happening is sometimes bleak, as family members realize. They veer between hope and despair and expect a miracle to occur, despite the poor outlook and even though it is pointless (48, 50, 53, 54, 76, 77).

Enduring

To endure waiting while living in uncertainty and not knowing what the future has in store is a form of torture for family members (50, 55, 57-61, 63, 78, 79). They have to endure being on tenterhooks because something may happen at any time to their loved one. This situation is mentally and physically exhausting and entails suffering (50, 63, 80). Families also find it difficult to endure the wait because they have handed over control to the ICU staff and doubt if

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55

Review Copy

those people have full control over the sick relative’s situation. (73, 81) However, it is easier to endure waiting in the hospital than at home. Being outside the loved one’s room or in the waiting room means being close if anything should happen (44, 50, 63, 64). Getting information about the relative’s condition and prognosis can make it easier to endure the waiting because it gives them some control over the situation (50, 53, 78). It is also easier to endure the wait if the family members feel it has a meaning, for example if they are involved in nursing care (50, 53) or watching over the relative’s progress or recovery (50, 57). Family members may support each other in their waiting, which makes it easier to endure (50, 53).

Fearing the worst

Family members fear that the worst may happen to their loved one and they are in a constant state of tension and can never relax. They are worried when they are with their relative in the ICU but even more so when they are not present at the relative’s side. When they are away from the loved one’s bed, they expect that the worst to happen at any time and these thoughts are terrifying (46, 50, 55, 58, 71).

Exemplar

According to Rodgers an exemplar of the text in the data should be identified prior to the author generating an example (13). In our study the exemplar was not generated by the authors but found in the analysis material. The example below illustrates family members’ waiting in the ICU and contains all the attributes:

“Waiting is such an unknown quantity. It is horrendous you are almost suspended. It's like you're

frightened and hopeful at the same time. It's all those mixed up emotions fear and uncertainty and worry and tension. You almost feel numb, and you get terribly tired because all this energy is being spent in worry and concern.” (50, p. 62)

Consequences

The events after that the concept occur describe its consequences (14). Family members do not stop waiting until the loved one is discharged from the intensive care unit or dies (79, 81). When

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56

Review Copy

family members are waiting in vain for answers and do not receive any, or uncertain, responses they are affected negatively and they experience suffering (62, 65). The consequences of waiting are also affected by whether or not the relative recovers. If they do, family members feel relief, but if the loved one dies they feel even more exhausted and everyone felt that waiting in the ICU seemed meaningless and without purpose (54, 58, 82).

DISCUSSION

Family members' waiting has been shown to be present throughout the care period in various types of intensive care departments and does not end until the patient is discharged or dies. All family members in the ICU are waiting in one way or another, but they can perceive the waiting in different ways. As Fogarty and Cronin (2) and Irvin (1) point out, the perception of waiting is a subjective experience. All characteristic attributes in our study showed that waiting is identified primarily as a negative thing for family members. ICU staff need to become more aware of family members’ waiting, and the burden it is to them. Being psychologically burdened is common among family members who have or have had a loved one in an ICU (16, 83, 84). This burden can comprise anxiety, stress and/or depression and there should, therefore, be routine assessments to identify any affected family members (84). Martinsen (85) claims that understanding other people’s situations is a key concept in caring and ICU staff need knowledge and training in how to assess and care for family members who could suffer or are suffering from the waiting.

An ICU department must offer a supportive environment for family members. This means giving the ICU staff practical and theoretical education in the assessment and care of the waiting family members. In doing this the ICU staff are able to achieve more sustainable care in the intensive care environment (86, 87). In addition, the department can provide the best possible family-friendly conditions through adequate education and action directed to the environment, for example single rooms for patients, free visiting hours, adequate staffing and customized waiting rooms based on family members' needs (88). But it is the individual who has the ultimate responsibility for performing the care that is needed. It is important that the ICU staff have a holistic caring approach if the care is to be sustainable (86, 87). There is a need to care not only

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55

Review Copy

for the patient but also for the family. It has been shown that involving family members in the care of their loved ones can reduce anxiety (89). Our study shows that it is easier for family members to endure waiting if they feel that they are a part of the care, giving the waiting a meaning for them. Involving them in the care can lead to a more sustainable care, which will prevent psychological illness and alleviate unnecessary suffering.

In Fogarty and Cronin’s (2) concept analysis concerning patients’ waiting for healthcare they describe how the patients felt powerlessness and Irving shows that (1) family members could feel loss of control while waiting for information. Our study shows that family members feel it is easier to endure waiting at the hospital that at home. But they could also feel powerless and helpless when the ICU staff tell them to go to a waiting room when they want to be close to their relatives. Previous studies (31-33) have reported that ICU staff can experience family members as obstacles preventing them from performing their work which is why they direct family members to wait outside. Family members should always be asked if they want to stay beside their relative in an emergency and/or in a calmer stage in daily care. Guidelines for resuscitation (90) stress that family members should be asked if they want to be present and, if they do, there should be someone who can support them (90). Being present can reduce the family burden (90) and their being there does not have a negative effect on the resuscitation or its outcome (91). In earlier studies ICU staff have said they feel great ambivalence about family members attending resuscitation or invasive procedures. Some could not see the advantage of having family members present and others felt that they could not work properly with family members watching (92-94). According to Martinsen (85) staff possess power through their knowledge and experience which they can use for good or bad. The staff's moral attitude determines how the power expresses itself, towards family members, for example. In order to avoid abusing their power the staff must become aware of their actions, create a good caring relationship and be sensitive to the needs of the family members. The staff cannot assume that they know what is best for the family or the patient. The family members are in an unfamiliar and vulnerable situation including physical, mental and existential worries. If the staff mismanages power family members can feel increased vulnerability and insecurity instead of security and trust in a good, caring relationship (85).

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56

Review Copy

In the study of Adams et al. (95) family members said that, for them to inspire trust, ICU staff must behave calmly and sensibly, as this makes it easier for them to cope with the situation. They wanted honest, true information and they did not want the ICU staff to give them false hope (95). The staff must inspire trust to allow family members to feel safe in the vulnerable situation they find themselves in (96). However, the ICU staff can find giving honest information difficult and that it can deprive family members of their hopes (33). Our study shows that the suffering the family members experience during waiting can be relieved by providing them with continuous information, by answering their questions and by letting them be as close to their loved one as possible. It is, therefore, important for ICU staff to inform and adequately support family members thereby avoiding unnecessary suffering.

Methodological considerations

This analysis is not a complete or definitive answer to what the concept of family members’ waiting in the ICU means. The purpose of a concept analysis is to clarify the concept and create a foundation for further development and research directions regarding the concept. The clinical implications are identified in a caring context based on the knowledge gaps discovered. (13)

All the authors have practical experience and theoretical knowledge as both ICU nurses and researchers, and have reflected on their professional, theoretical and personal preunderstanding throughout the study in order to avoid bias (97). To enhance the rigour and credibility of the study the authors used verification strategies, in accordance with Morse et al. (98). By creating congruence between the study’s aim and the method used and by clearly explaining the steps taken in the analysis process. Moreover, in discussing our preunderstanding throughout those steps, the assessments and choices made throughout the study were as objective/neutral as possible. The interpretation of the analysis was also checked and rechecked to make sure that it was the most reliable one.

The lexical description of waiting was limited to the Oxford Dictionary as neither the Merriam-Webster nor the Cambridge Dictionaries described waiting as a concept. Restricting the search to the PubMed and CINAHL databases, selecting search terms and context avoided the gathering of

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55

Review Copy

an overwhelming amount of data. Searching only for articles written in English may have led to some being missed, but the articles chosen for the study originate from different parts of the world and were considered representative with reference to the aim.

CONCLUSIONS

This study reveals five critical attributes that family members experience when waiting in an intensive care context. The attributes are: living in limbo, feeling helpless and powerless, hoping, enduring and fearing the worst. The concept analysis has provided a deeper understanding of the concept of family members’ waiting in an intensive care context and its meaning. This may help professionals in intensive care to be more aware of how to take care of family members who are waiting. The waiting is inevitable but improved communication between the ICU staff and family members can significantly reduce stress and alleviate suffering. It is important to acknowledge that waiting cannot be eliminated but family-centered care, including a friendly and welcoming hospital environment, can ease the burden of family members when their loved one is being cared for in an ICU.

REFERENCES

1 Irvin SK. Waiting: concept analysis. Nursing Diagnosis 2001; 12: 128-36.

2 Fogarty C, Cronin P. Waiting for healthcare: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2008; 61: 463-71.

3 Sadeghi T, Nayeri ND, Abbaszadeh A. The waiting process: a grounded theory study of families’ experiences of waiting for patients during surgery. J Res Nurs 2015; 20: 372-82. 4 Trimm DR, Sanford JT. The process of family waiting during surgery. J Fam Nurs 2010; 16: 435-61.

5 Jeonghyun K, Chiyoung C. Experience of fathers of neonates with congenital heart disease in South Korea. Heart Lung 2017; 46: 439-43.

6 Bremer A, Dahlberg K, Sandman L. Experiencing out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: significant others’ lifeworld perspective. Qual Health Res 2009; 19: 1407-20.

7 Cater R, Taylor J. The experiences of heart transplant recipients’ spouses during the pretransplant waiting period: integrative review. J Clin Nurs 2017; 26: 2865-77.

8 Al-Mutair AS, Plummer V, O’Brien A, Clerehan R. Family needs and involvement in the intensive care unit: a literature review. J Clin Nurs 2013; 22: 1805-17.

9 Obeidat H, Bond E, Callister L. The parental experience of having an infant in the newborn intensive care unit. J Perinat Educ 2009; 18: 23-9.

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56

Review Copy

10 Vasconcelos E, Freitas K, Da Silva S, Baia R, Tavares R, Araújo J. The daily life of relatives of patients admitted in icu: a study with social representations. Journal of Research

Fundamental Care Online 2016; 8: 4313-27.

11 Van Horn E, Tesh A. The effect of critical care hospitalization on family members: stress and responses. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2000; 19: 40-9.

12 De Beer J, Brysiewicz P. The needs of family members of intensive care unit patients: a grounded theory study. S Afr Med J 2017; 32: 44-9.

13 Rodgers BL. Concept analysis: an evolutionary view. In: Concept Development in

Nursing: Foundations, Techniques and Applications (Rodgers BL, Knafl KA eds.), 2000

Saunders, Philadelphia, 77-102.

14 Rodgers BL. Concepts, analysis and the development of nursing knowledge: the evolutionary cycle. J Adv Nurs 1989; 14: 330-5.

15 Bizek SB, Fontaine KD. The patient’s experience with critical care illness. In: Critical

Care Nursing - A Holistic Approach (Morton GP, Fontaine KD eds.), 2013 Lippincott Williams

& Wilkins, Philadelphia, 15-28.

16 McAdam JL, Fontaine DK, White DB, Dracup KA, Puntillo KA. Psychological

symptoms of family members of high-risk intensive care unit patients. Am J Crit Care 2012; 21: 386-94.

17 Davidson EJ, Jones JC, Bienvenu JO. Family response to critical illness: postintensive care syndrome–family. Crit Care Med 2012; 40: 618-24.

18 Carlson EB, Spain DA, Muhtadie L, McDade-Montez L, Macia KS. Care and caring in the ICU: family members’ distress and perceptions about staff skills, communication, and emotional support. J Crit Care 2015; 30: 557-61.

19 Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir

Crit Care Med 2005; 171: 987-94.

20 Molter NC. Needs of relatives of critically ill patients: a descriptive study. Heart Lung 1979; 8: 332-9.

21 Leske JS. Needs of relatives of critically ill patients: a follow-up. Heart Lung 1986; 15: 189-93.

22 Leske JS. Interventions to decrease family anxiety. Crit Care Nurse 2002; 22: 61-5. 23 Omari FH. Perceived and unmet needs of adult Jordanian family members of patients in ICUs. J Nurs Scholarsh 2009; 41: 28-34.

24 Zainah M, Sasikala M, Nurfarieza MA, Ho SE. Needs of family members of critically ill patients in a critical care unit at universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia medical centre. Medicine &

Health 2016; 11: 11-21.

25 Fridh I, Forsberg A, Bergbom I. End-of-life care in intensive care units - family routines and environmental factors. Scand. J Caring Sci 2007; 21: 25-31.

26 Kohi TW, Obogo MW, Mselle LT. Perceived needs and level of satisfaction with care by family members of critically ill patients at Muhimbili National hospital intensive care units, Tanzania. BMC Nurs 2016; 15: 18.

27 Plakas S, Taket A, Cant B, Fouka G, Vardaki Z. The meaning and importance of vigilant attendance for the relatives of intensive care unit patients. Nurs Crit Care 2014; 19: 243-54. 28 Kutash M, Northrop L. Family members’ experiences of the intensive care unit waiting room. J Adv Nurs 2007; 60: 384-8.

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55

Review Copy

29 Bijttebier P, Vanoost S, Delva D, Ferdinande P, Frans E. Needs of relatives of critical care patients: perceptions of relatives, physicians and nurses. Intensive Care Med 2001; 27: 160-5.

30 Hunziker S, McHugh W, Sarnoff-Lee B, Cannistraro S, Ngo L, Marcantonio E et al. Predictors and correlates of dissatisfaction with intensive care. Crit Care Med 2012; 40: 1554-61.

31 Hardicre J. Nurses’ experiences of caring for the relatives of patients in ICU. Nurs Times 2003; 99: 34-7.

32 Fateel EE, O’Neill CS. Family members’ involvement in the care of critically ill patients in two intensive care units in an acute hospital in Bahrain: the experiences and perspectives of family members’ and nurses’ - a qualitative study. Clin Nurs Stud 2016; 4: 57-69.

33 Stayt LC. Nurses’ experiences of caring for families with relatives in intensive care units.

J Adv Nurs 2007; 57: 623-30.

34 Engström Å, Söderberg S. Close relatives in intensive care from the perspective of critical care nurses. J Clin Nurs 2007; 16: 1651-9.

35 Svenska Intensivvårdsregistret (SIR) [Swedish Intensive Care Registry]. Svenska

Intensivvårdsregistret (SIR) Årsrapport 2016: Sammanfattning, analys och reflektioner [Swedish Intensive Care Registry Annual Report 2016: Summary, analysis and reflections]. [last accessed

30 October 2017] Available from:

http://www.icuregswe.org/Documents/Annual%20reports/2016/Analyserande_arsrapport_2016.p df

36 Rodgers BL, Knafl KA. Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques and

Applications. 2000, Saunders, Philadelphia.

37 Oxford English Dictionary Online. 2017, Oxford University Press, Oxford, [last accessed 06 September 2017] Available from: https://www.oxforddictionaries.com/

38 Norton CK. The family’s experience with critical illness. In: Critical Care Nursing - A

Holistic Approach (Morton GP, Fontaine KD eds.), 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins,

Philadelphia, 29-38.

39 Harvey JH, Omarzu J. Minding the Close Relationship : A Theory of Relationship

Enhancement. 2006, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

40 Eriksson T, Bergbom I. Visits to intensive care unit patients – frequency, duration and impact on outcome. Nurs Crit Care 2007; 12: 20-6.

41 Tofthagen R, Fagerstrøm LM. Rodgers’ evolutionary concept analysis - a valid method for developing knowledge in nursing science. Scand. J Caring Sci 2010; 24: 21-31.

42 World Medical Association [WMA]. WMA Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles

for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. [last accessed 29 October 2017] Available

from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/

43 European Science Foundation [ESF]. The European Code of Conduct for Research

Integrity. [last accessed 29 October 2017] Available from:

https://www.nsf.gov/od/oise/Code_Conduct_ResearchIntegrity.pdf

44 Burr G. Contextualizing critical care family needs through triangulation: an Australian study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 1998; 14: 161-9.

45 Fishering R, Broeder JL, Donze A. A qualitative study: NICU nurses as NICU parents.

Adv Neonatal Care 2016; 16: 74-86. 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56

Review Copy

46 Hall EOC. Being in an alien world: Danish parents’ lived experiences when a newborn or small child is critically ill. Scand. J Caring Sci 2005; 19: 179-85.

47 Fridh I, Forsberg A, Bergbom I. Close relatives’ experiences of caring and of the physical environment when a loved one dies in an ICU. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2009; 25: 111-9.

48 Frid I, Bergbom I, Haljamäe H. No going back: narratives by close relatives of the braindead patient. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2001; 17: 263-78.

49 Noyes J. The impact of knowing your child is critically ill: a qualitative study of mothers’ experiences. J Adv Nurs 1999; 29: 427-35.

50 Bournes DA, Mitchell GJ. Waiting: the experience of persons in a critical care waiting room. Res Nurs Health 2002; 25: 58-67.

51 Fridh I, Bergbom I. To watch -- a study of the concept. Nordic Journal of Nursing

Research & Clinical Studies / Vård i Norden 2006; 26: 4-8.

52 Jamerson PA, Scheibmeir M, Bott MJ, Crighton F, Hinton RH, Cobb AK. The

experiences of families with a relative in the intensive care unit. Heart Lung 1996; 25: 467-74. 53 Plowfield LA. Living a nightmare: family experiences of waiting following neurological crisis. J Neurosci Nurs 1999; 31: 231-8.

54 Knutsson S, Samuelsson IP, Hellström A-L, Bergbom I. Children’s experiences of visiting a seriously ill/injured relative on an adult intensive care unit. J Adv Nurs 2008; 61: 154-62.

55 Fontana JS. A sudden, life-threatening medical crisis: the family’s perspective. ANS Adv

Nurs Sci 2006; 29: 222-31.

56 Dreyer A, Nortvedt P. Sedation of ventilated patients in intensive care units: relatives’ experiences. J Adv Nurs 2008; 61: 549-56.

57 Ågård AS, Harder I. Relatives’ experiences in intensive care—finding a place in a world of uncertainty. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2007; 23: 170-7.

58 Engström Å, Söderberg S. The experiences of partners of critically ill persons in an intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2004; 20: 299-308.

59 Gavey J. Parental perceptions of neonatal care. J Neonatal Nurs 2007; 13: 199-206. 60 Larsson I-M, Wallin E, Rubertsson S, Kristoferzon M-L. Relatives’ experiences during the next of kin’s hospital stay after surviving cardiac arrest and therapeutic hypothermia. Eur J

Cardiovasc Nurs 2013; 12: 353-9.

61 Nolen KB, Warren NA. Meeting the needs of family members of ICU patients. Crit Care

Nurs Q 2014; 37: 393-406.

62 Wigert H, Dellenmark Blom M, Bry K. Parents’ experiences of communication with neonatal intensive-care unit staff: an interview study. BMC Pediatr 2014; 14: 304.

63 Eggenberger SK, Nelms TP. Being family: the family experience when an adult member is hospitalized with a critical illness. J Clin Nurs 2007; 16: 1618-28.

64 McKiernan M, McCarthy G. Family members’ lived experience in the intensive care unit: a phemenological study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2010; 26: 254-61.

65 Verhaeghe STL, van Zuuren FJ, Defloor T, Duijnstee MSH, Grypdonck MHF. How does information influence hope in family members of traumatic coma patients in intensive care unit?.

J Clin Nurs 2007; 16: 1488-97.

66 Hinkle JL, Fitzpatrick E. Needs of American relatives of intensive care patients: perceptions of relatives, physicians and nurses. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2011; 27: 218-25. 67 Majdalani MN, Doumit MAA, Rahi AC. The lived experience of parents of children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit in Lebanon. Int J Nurs Stud 2014; 51: 217-25.

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55

Review Copy

68 Söderström I-M, Saveman B-I, Benzein E. Interactions between family members and staff in intensive care units—an observation and interview study. Int J Nurs Stud 2006; 43: 707-16.

69 Schwarzkopf D, Behrend S, Skupin H, Westermann I, Riedemann N, Pfeifer R et al. Family satisfaction in the intensive care unit: a quantitative and qualitative analysis. Intensive

Care Med 2013; 39: 1071-9.

70 Stremler R, Dhukai Z, Wong L, Parshuram C. Factors influencing sleep for parents of critically ill hospitalised children: a qualitative analysis. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2011; 27: 37-45.

71 Kisorio LC, Langley GC. End-of-life care in intensive care unit: family experiences.

Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2016; 35: 57-65.

72 Hansen L, Rosenkranz SJ, Mularski RA, Leo MC. Family perspectives on overall care in the intensive care unit. Nurs Res 2016; 65: 446-54.

73 Olausson S, Ekebergh M, Lindahl B. The ICU patient room: Views and meanings as experienced by the next of kin: a phenomenological hermeneutical study. Intensive Crit Care

Nurs 2012; 28: 176-84.

74 Tramm R, Ilic D, Murphy K, Sheldrake J, Pellegrino V, Hodgson C. Experience and needs of family members of patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Clin

Nurs 2016; 26: 1657-68.

75 Henrich NJ, Dodek P, Heyland D, Cook D, Rocker G, Kutsogiannis D et al. Qualitative analysis of an intensive care unit family satisfaction survey. Crit Care Med 2011; 39: 1000-5. 76 Knutsson S, Bergbom I. Children’s thoughts and feelings related to visiting critically ill relatives in an adult ICU: a qualitative study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2016; 32: 33-41.

77 Wiegand D. In their own time: the family experience during the process of withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy. J Palliat Med 2008; 11: 1115-21.

78 Fry S, Warren NA. Perceived needs of critical care family members: a phenomenological discourse. Crit Care Nurs Q 2007; 30: 181-8.

79 Hall EOC. A double concern: Danish grandfathers’ experiences when a small grandchild is critically ill. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2004; 20: 14-21.

80 Wåhlin I, Ek A, Idvall E. Empowerment from the perspective of next of kin in intensive care. J Clin Nurs 2009; 18: 2580-7.

81 Carnevale FA. A description of stressors and coping strategies among parents of critically ill children—a preliminary study. Intensive Care Nurs 1990; 6: 4-11.

82 Löf S, Sandström A, Engström Å. Patients treated with therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest: relatives’ experiences. J Adv Nurs 2010; 66: 1760-8.

83 Schmidt M, Azoulay E. Having a loved one in the ICU: the forgotten family. Curr Opin

Crit Care 2012; 18: 540-7.

84 Kentish-Barnes N, Lemiale V, Chaize M, Pochard F, Azoulay E. Assessing burden in families of critical care patients. Crit Care Med 2009; 37: 448-56.

85 Martinsen K. Omsorg, Sykepleie og Medisin : Historisk-Filosofiske Essays [Caring,

Nursing and Medicine: Historical-Philosophical Essays]. 1989, Tano: Oslo.

86 Anåker A, Elf M. Sustainability in nursing: a concept analysis. Scand. J Caring Sci 2014; 28: 381-9.

87 Goodman B. Developing the concept of sustainability in nursing. Nurs Philos 2016; 17: 298-306. 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56

Review Copy

88 Khalaila R. Meeting the needs of patients’ families in intensive care units. Nurs Stand 2014; 28: 37-44.

89 Hoseini Azizi T, Hasanzadeh F, Esmaily H, Ehsaee MR. The effect of family members’ supportive presence in neurological intensive care unit on their anxiety. Modern Care Journal 2015; 12: 23-30.

90 Bossaert LL, Perkins GD, Askitopoulou H, Raffay VI, Greif R, Haywood KL et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015: Section 11. The ethics of resuscitation and end-of-life decisions. Resuscitation 2015; 95: 302-11.

91 Goldberger ZD, Nallamothu BK, Nichol G, Chan PS, Curtis JR, Cooke CR. Policies allowing family presence during resuscitation and patterns of care during in-hospital cardiac arrest. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2015; 8: 226-34.

92 McClenathan CBM, Torrington CKG, Uyehara CFT. Family member presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a survey of US and international critical care professionals. Chest 2002; 122: 2204-11.

93 Miller JH, Stiles A. Family presence during resuscitation and invasive procedures: the nurse experience. Qual Health Res 2009; 19: 1431-42.

94 Duran CR, Oman KS, Abel JJ, Koziel VM, Szymanski D. Attitudes toward and beliefs about family presence: a survey of healthcare providers, patients’ families, and patients. Am J

Crit Care 2007; 16: 270-9.

95 Adams JA, Anderson RA, Docherty SL, Tulsky JA, Steinhauser KE, Bailey DE. Nursing strategies to support family members of ICU patients at high risk of dying. Heart Lung 2014; 43: 406-15.

96 Martinsen K. Care and Vulnerability. 2006, Akribe, Oslo.

97 Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet 2001; 358: 483-8.

98 Morse JM, Barrett M, Mayan M, Olson K, Spiers J. Verification strategies for

establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods 2002; 1: 13-22. 99 Åstedt-Kurki P, Kaunonen M. Author Guidelines. [last accessed 26 October 2017] Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/%28ISSN%291471-6712/homepage/ForAuthors.html 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55

Review Copy

Table 1 Primary activities in Rodgers’ evolutionary method of concept analysis (13, p. 85).

1. Identify the concept of interest and associated expressions (including surrogate terms). 2. Identify and select an appropriate realm (setting and sample) for data collection. 3. Collect data relevant to identify:

a) the attributes of the concept and

b) the contextual basis of the concept, including interdisciplinary, sociocultural and temporal (antecedent and consequential occurrences) variations.

4. Analyze data regarding the above characteristics of the concept. 5. Identify an exemplar of the concept, if appropriate.

6. Identify implications, hypotheses and implications for further development.

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56

Review Copy

Table 2 Questions based on Rodgers’ evolutionary method used during the analysis, according

to Tofthagen and Fagerstrøm (41, p. 24).

Surrogate/related terms: Do other words say the same thing as the chosen concept? Do other words have

something in common with the concept?

Antecedents: Which events or phenomena have been associated with the concept in the past?

Attributes: What are the concept’s characteristics?

Examples: Are concrete examples of the concept described in the data material?

Consequences: What happens after or as a result of the concept?

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55

Review Copy

Table 3 Articles included in the concept analysis.

Author/s, Year of publication, Country

Reference Journal Aim/Purpose Design/Method/Sample Age of the patient (P) and family members (F)

Burr, 1998; Australia

(44) Intensive & Critical Care Nursing

The aim was to gain a global understanding of the needs and experiences of family members, as well as an insight into nurse-family roles and the

relationship from the ICU nurses’ perspective.

Methodological triangulation formed with quantitative CCFNI questionnaire and qualitative through semi-structured interviews. CCFNI (n = 105 family members) and interviews (n = 26 family members). P=unknown F > 16 years of age Bournes & Mitchell, 2002; Canada (50) Research in Nursing & Health

The purposes of this study were: to discover the essence of the experience of waiting for persons who have family members or friends in a critical care unit; to provide new knowledge about what it is like to wait that can be used as a guide in research and practice; and to contribute to knowledge about human becoming. Phenomenological-hermeneutical, Interviews, n=12 family members. P=unknown F > 18 years of age Carnevale, 1990; Canada (81) Intensive Care Nursing

The purpose of this study was to describe perceived stressors and coping strategies among parents of critically ill children.

Exploratory descriptive research design, Subjects were interviewed using a client-centred phenomenological approach, n=5 family members. P= 1 month-8 years F= between 29-39 years of age Dreyer & Nortvedt, 2008; Norway (56) Journal of Advanced Nursing

The aim of the study was to explore the experiences of being relatives of ventilated and sedated patients in ICUs. Explorative, descriptive design, phenomenology, in-depth interviews, n=8 family members.. P= teenagers and adults F > 18 years of age Eggenberger & Nelms, 2007; USA (63) Journal of Clinical Nursing

The purpose of this qualitative study was to understand and interpret the phenomenon of the family experience of having an adult family member hospitalized with a critical illness.

Family systems theory and existential phenomenology, Semi-structured group interviews, n=41 family members. P= between 23-75 years of age F= between 13-87 years of age Engström & Söderberg, 2004; Sweden

(58) Intensive & Critical Care Nursing

The aim of this study was to describe partners' experiences when their spouses received care in an intensive care unit (ICU). Qualitative, Narrative interviews, n=7 family members. P=unknown F=between 22-63 years of age Fishering et al., 2016; USA (45) Advances in Neonatal Care

This study examines the lived experiences of NICU nurses, how they coped with their roles as professionals and Narrative qualitative design, Interviews, n=6 family members. P= newborn F=mother’s age unknown 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56

Review Copy

parents, and how their responses differed from those of NICU mothers without professional NICU experience. Fontana, 2006; USA (55) Advances in Nursing Science

The aim is to describe the experience of a sudden life-threatening medical crisis from the perspective of the family. Descriptive phenomenology, Interviews, n =6 family members. P= newborn, children, and adults P=adult Frid et al., 2001; Sweden

(48) Intensive & Critical Care Nursing

The aim of this study was to illuminate the meaning of being a relative of a patient diagnosed as brain dead.

Phenomenological– hermeneutic, Narrative interviews, n=17 family members. P= between 38-69 years of age F= between 16-68 years of age Fridh et al., 2009; Sweden

(47) Intensive & Critical Care Nursing

The aim of the study was to explore close relatives’ experiences of caring and of the physical environment when a next of kin dies in an intensive care unit.

The interviews were analyzed using a phenomenological-hermeneutic method, Interviews, n=17 family members. P= between 55-87 years of age F= between 32-75 years of age Fry & Warren,

2007; USA

(78) Critical Care Nursing Quarterly

The purpose was to examine the perceived needs of the critical care family members in the waiting room viewed through their own words and to stimulate discussion about the language used by the participants. Phenomenological study with Heidegerian hermeneutic contextual analysis, Interviews, n=15 family members. P= unknown F= unknown Gavey, 2007; England (59) Journal of Neonatal Nursing

The aim was to investigate retrospective experiences of parents whose infants required admission to a Neonatal Unit..

Qualitative, semi-structured interviews, The analysis was an adaptation of Burnard (1991) created by Denscombe (1998). n=16 mothers. P= between 22-37 weeks of age F= between 22-37 years of age Hall, 2004; Denmark

(79) Intensive & Critical Care Nursing

The aim is to describe grandfathers’ lived experience when a new-born or small child is critically ill.

Qualitative. Exploratory inductive design. Methodology was inspired by Spiegelberg's (1982) and Van Manen's (1990) phenomenological approach, interviews, n=7 grandfathers. P= newborn F= between 56-66 years of age Hall, 2005; Denmark (46) Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences

The aim was to identify Danish parents’ lived experiences during a newborn’s or small child’s critical illness.

Qualitative phenomenological study, Interviews, n=13 family members. P= between 0-18 months of age F= between 25-36 years of age Hansen et al., 2016; USA

(72) Nursing Research The purpose was to qualitatively analyze comments provided by family members of patients in ICUs in the United States to better understand their perspectives on how to As part of a larger multimethod study. Qualitative content analysis of open-ended questions in Family Satisfaction in the ICU (FS-ICU) questionnaire, n=106 family members. P=unknown F= between 22-88 years of age 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55

Review Copy

Hinkle & Fitzpatrick, 2011; USA

(66) Intensive & Critical Care Nursing

The main research question was: 1. What

were the perceptions of needs for American critically ill patients as identified by relatives, physicians and nurses?

2. To compare the

differences in the perceptions of needs on the total CCFNI and CCFNI subscales (Information, Proximity, Assurance, Comfort and Support) in a cohort of critically ill American patients as perceived by relatives, physicians and nurses. 3. To identify if

there were needs perceived by relatives, physicians or nurses that were not captured by the CCFNI.

Quantitative using the questionnaire Critical Care Family Needs Inventory (CCFNI) and with open-ended questions. A prospective descriptive study, n=101 family members. Quantitatively analyzed by SPSS, version 17. P= between 76-40 years of age F= between 37-62 years of age Henrich et al., 2011; Canada (75) Critical Care Medicine To describe the qualitative findings from a family satisfaction survey to identify and describe the themes that characterize family members' intensive care unit experiences.

As part of a larger mixed-method study. Qualitative with three open-ended questions with written responses, n=421 family members. Analyzed using NVivo 8 (QSR

International, Melbourne, Australia), qualitative research software for thematic coding and analysis.

P= unknown F= unknown

Jamerson et al., 1996; USA

(52) Heart & Lung To describe the experiences of families with a relative in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Retrospective, descriptive, qualitative, focus group interview and unstructured, interactive individual interviews, n=20 family members. Data analyzed based on Miles and Huberman (1994). P= adult F= > 18 years of age Kisorio & Langley, 2016; South Africa

(71) Intensive & Critical Care Nursing

To elicit family members’ experiences of end-of-life care in adult intensive care units.

Descriptive, exploratory, qualitative design, Semi-structured interviews, n=17 family members. Data analyzed based on Tesch’s (1990) steps of analysis. P= adult F= between 20-51 years of age Knutsson & Bergbom, 2016; Sweden

(76) Intensive & Critical Care Nursing

The aim was to describe and understand children’s thoughts and feelings related to visiting critically ill relatives or family members in an adult ICU.

Qualitative descriptive study, Interviews, n=28 children. Analysis inspired by Gadamer’s (2000) hermeneutic philosophy and Doverborg and Pramling Samuelsson's (2000) method. P= unknown F= between 4-17 years of age Knutsson et al., 2008; Sweden (54) Journal of Advanced Nursing

The aim of the study was to describe children’s experiences of visiting a seriously ill/injured relative in an ICU. Qualitative, Interviews, n=29 children. Analysis inspired by Gadamer’s (2000) hermeneutic philosophy and Doverborg and Pramling Samuelsson's (2000) method. P= unknown F= between 4-17 years of age 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56

Review Copy

Larsson et al., 2013; Sweden (60) European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing To describe relatives’ experiences during the next of kin’s hospital stay after surviving a cardiac arrest treated with hypothermia at an intensive care unit (ICU).Qualitative description, Semi-structured interviews, n=20 family members. Data analyzed using qualitative content analysis P= unknown F= between 20-70 years of age Löf et al., 2010; Sweden (82) Journal of Advanced Nursing

The aim of this study was to describe the experiences of relatives when someone they care for survived a cardiac arrest and was treated with therapeutic hypothermia in an intensive care unit.

Inductive qualitative study, Interviews, n=8 family members. Data analyzed using qualitative content analysis, as described by Downe-Wamboldt (1992) P= unknown F= between 30-72 years of age Majdalani et al., 2014; Lebanon (67) International Journal of Nursing Studies

To understand the lived experience of Lebanese parents of children admitted to the PICU in a tertiary hospital in Beirut.

Heideggerian interpretive phenomenological approach. Interviews, n=10 family members. Data were analyzed using a hermeneutical process. P= between 3 months and 15 years of age F= mean age of mothers and faders 30,8 years McKiernan & McCarthy, 2010; Ireland

(64) Intensive & Critical Care Nursing

The aim was to describe the lived experience of family members of patients in the intensive care unit. Assumptions of Heideggerian. hermeneutic phenomenology, Interviews, n=6 family members. P= unknown F= > 18 years of age Nolen & Warren, 2014; USA (61) Critical Care Nursing Quarterly

The aim was to explore and identify the perceptions of family members’ needs and to ascertain if those needs were perceived as met or unmet by the family members of patients housed in the ICU:s.

Triangulation, mixed method design. Quantitative in the use of the Needs Met Inventory (NMI) questionnaire, n=31 family members. Quantitative data analyzed by SPSS. Qualitative through interviews, n=4 family members. Qualitative data analyzed using thematic contextual analysis. P= unknown Qualitative F= between 51-61 years of age Quantitative F= >18 years of age Noyes, 1999; England (49) Journal of Advanced Nursing

The aim of the study emerged from a critique of the literature and reflection on practice, and was refined `to elicit mothers' lived

experiences of crisis and coping, and their experiences of nursing following the unexpected emergency admission of their child to a PICU.

Qualitative, Focused interviews, n=10 mothers. Data analyzed based on Silverman (1994) and Glaser and Strauss (1967).

P= infants-children F= mother’s age unknown Olausson et al., 2012; Sweden

(73) Intensive & Critical Care Nursing

The aim of this study was to describe and interpret the meanings of the intensive care patient room as experienced by the patients’ next of kin.

Phenomenological hermeneutical method, Interviews, n=14 family members. P= unknown F= between 28-70 years of age 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55

Review Copy

Plowfield, 1999; USA (53) The Journal of Neuroscience NursingThe aim was to examine the lived experience of families who wait following neurological crisis. Phenomenological. In-depth interviews, n=34 family members. P= between 16-68 years of age F= between 22-68 years of age Schwarzkopf et al., 2013; Germany (69) Intensive Care Medicine To assess family satisfaction in the ICU and areas for improvement, using quantitative and qualitative analyses.

Prospective cohort study using Family Satisfaction in the ICU (FSICU) questionnaire. Quantitative with questions answerable on a rating scale and Qualitative through questionnaire with open-ended questions. n=215 family members. P= unknown F= > 18 years of age Stremler et al., 2011; Canada

(70) Intensive & Critical Care Nursing

The aim of this study was to describe factors affecting the sleep of parents of critically ill children and to determine strategies to improve their sleep.

Part of a larger study this paper reports qualitative data. Questionnaire with open-ended questions. Prospective, observational study of parents’ sleep quality and quantity using objective and subjective measures of sleep, n=118 family members. Data analyzed using qualitative content analysis, as described by Sandelowski (2000) P= children F= > 18 years of age Söderström et al., 2006; Sweden (68) International Journal of Nursing Studies

The aim was to describe and interpret interactions between family members and staff in intensive care units with the focus on family members.

Qualitative. Descriptive and interpretive design. Interviews and observations, n=24 family members. P= between 15-84 years of age F= between 14-73 years of age Tramm et al., 2016; Australia (74) Journal of Clinical Nursing To explore the experiences of family members of patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Qualitative descriptive research design. Semi-structured interviews, n=10 family members. Data analyzed based on Braun and Clarke (2006) steps of analysis. P= unknown F= between 31-65 years of age Verhaeghe et al., 2007; Belgium (65) Journal of Clinical Nursing

To assess the interplay between hope and the information provided by healthcare professionals.

Grounded theory. In-depth interviews, n=22 family members. P= unknown F= between 17-85 years of age Wiegand, 2008; USA (77) Journal of Palliative Medicine

The purpose of this study was to understand the lived experience of families participating in the process of withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy from a family member with an unexpected, life-threatening illness or injury.

Hermeneutic-phenomenological approach. Interviews and observations, n=56 family members. P= between 20-82 years of age F= unknown Wigert et al., 2014; Sweden

(62) BMC Pediatrics The aim was to describe parents’ experiences of communication with NICU staff. Hermeneutic lifeworld interview study, n= 27 parents. P= infants F= between 26-44 years of age 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56

Review Copy

Wåhlin et al., 2009; Sweden

(80) Journal of Clinical Nursing

The aim of this study was to describe next of kin empowerment in an intensive care situation.

Phenomenological method. Interviews, n=10 family members. P= between 16-81 years of age F= between 35-75 years of age Ågård & Harder, 2007; Denmark

(57) Intensive & Critical Care Nursing

The aim of the study was to explore and describe the experiences of relatives of critically ill patients in adult intensive care.

Explorative and qualitative design. In-depth interviews using a Grounded Theory approach, n=7 family members. P= between 10-75 years of age F= between 39-72 years of age 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55